Abstract

The lipid-dependent species Malassezia sympodialis was isolated from two cats with otitis externa. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the isolation of lipid-dependent species of the genus Malassezia associated with skin disease in domestic animals.

Malassezia species are lipophilic yeasts that form an integral part of animal and human cutaneous microbiota (19). They are also considered important medical yeasts because they are etiological agents of chronic skin disorders and have been reported with increasing frequency as causative agents of life-threatening, iatrogenic, catheter-related sepsis both in immunocompromised individuals (1) and low-birth-weight neonates receiving parenteral lipid alimentation (23).

The genus has recently been revised on the basis of molecular data and lipid requirements and enlarged to include seven species. They include the three former species Malassezia furfur (Robin) Baillon 1889, Malassezia pachydermatis (Weidman) Dodge 1935, and Malassezia sympodialis Simmons & Guého 1990 and four new taxa, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia obtusa, Malassezia restricta, and Malassezia slooffiae (9, 12). M. pachydermatis is the only species not dependent on lipid supplementation for in vitro growth; the other six species are lipid dependent.

All lipid-dependent species can be isolated from healthy and diseased human skin. They may be involved in skin disorders such as pityriasis versicolor, folliculitis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis and even in systemic infection (8). M. pachydermatis is often isolated from domestic and wild animals (11), and it has occasionally been implicated in cases of systemic infection in humans (18, 24). This species can play an important role in chronic dermatitis and otitis externa, especially in carnivores. It is the most common yeast that contributes to otitis externa as a perpetuating factor in dogs and cats (20). However, otitis externa associated with lipid-dependent species in cats or other animals has not been mentioned to date.

In this paper, otitis externa associated with the lipid-dependent species M. sympodialis in two cats is reported. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the isolation of M. sympodialis involved in a skin disorder in domestic animals.

Case 1.

A 10-year-old female Persian cat presented with acute otitis externa in the right ear. The animal had pruritus and an excessive aural discharge. On otoscopic examination, a generalized erythema was seen, and the external meatus was full of flaky black wax. On examination, the cat did not have any other dermatological disorders or pathologies. The animal had no history of skin diseases.

Case 2.

A 14-year-old female Angora cat presented with a prolonged period of heat with weight loss and chronic otitis externa in the left ear with pruritus. The external ear canal was full of brownish wax, and erythema was seen on otoscopic examination. No other dermatological disorders or pathologies were detected. The cat did not have a history of skin diseases.

Microbiology.

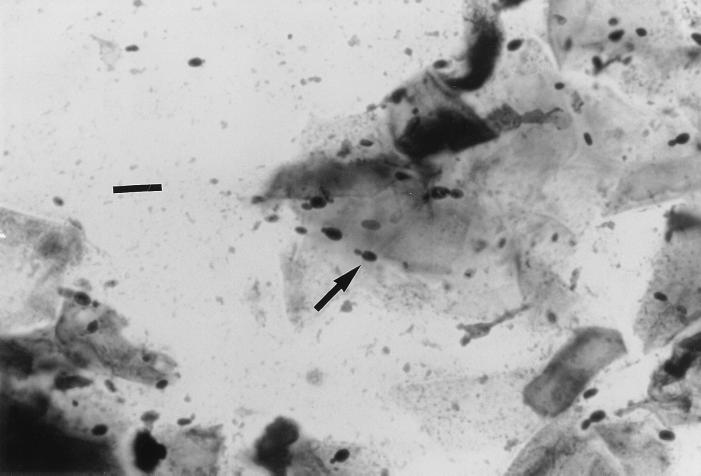

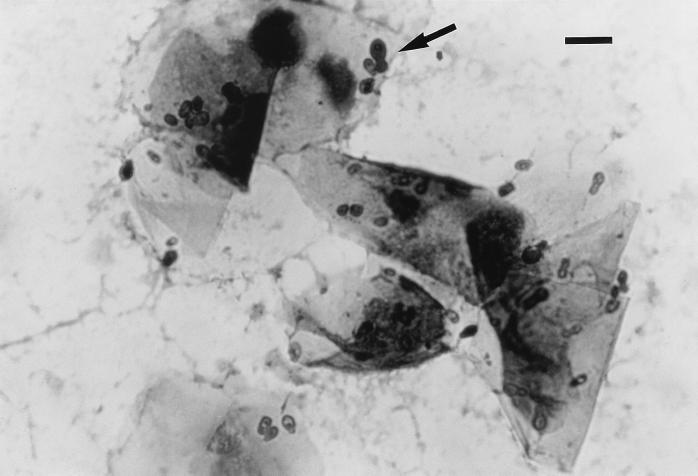

Swabs from the external ear canals of the two cats were obtained for microbiologic examination. The smears were stained with Gram and Diff-Quick stains. In both cases, Gram and Diff-Quick stains revealed the presence of numerous Malassezia cells, more than 10 organisms per high-power field. Hyphae were not seen. Buds were formed on a narrow base (Fig. 1), which differed from the monopolar budding on a broad base typical of M. pachydermatis (Fig. 2). No bacteria were detected in any case. Cultures on Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA), SGA supplemented with olive oil (10 ml/liter), and Leeming's medium (10 g of peptone, 5 g of glucose, 0.1 g of yeast extract, 4 g of desiccated ox bile, 1 ml of glycerol, 0.5 g of glycerol monostearate, 0.5 ml of Tween 60, 10 ml of whole-fat cow's milk, 12 g of agar per liter [pH 6.2]) (14) were made for mycological examination. All media contained 0.05% chloramphenicol and 0.05% cycloheximide. In the first case, the sample was inoculated only on these media because a presumed otitis due to M. pachydermatis had been clinically diagnosed. In the second case, the sample was also inoculated on blood agar and MacConkey agar for bacteriological examination. Plates of SGA, SGA supplemented with olive oil, and Leeming's medium were incubated at 35°C and examined after 3, 5, 7, and 14 days. Plates of blood agar and MacConkey agar were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 days.

FIG. 1.

Gram stain of a smear from an otic swab showing the presence of numerous M. sympodialis cells. Note that buds are formed on a narrow base. Bar, 10 μm.

FIG. 2.

Diff-Quick stain of a smear from an otic swab showing the typical monopolar budding on a broad base of M. pachydermatis. Bar, 10 μm.

Cultures on SGA supplemented with olive oil and Leeming's medium yielded numerous yeast colonies at 5 days of incubation. Two different types of colonies were isolated on SGA supplemented with olive oil: one type was yellow with a creamy texture, and the other was white with an oily texture. On Leeming's medium, all colonies were white with a soft texture. Cultures on SGA were negative at 14 days of incubation. Bacteriological culture was negative at 3 days of incubation (case 2).

Five different colonies were selected from SGA supplemented with olive oil (including the two different types of colonies) and Leeming's medium and subcultured onto SGA to determine their lipid dependence. All selected yeasts were considered lipid dependent species because they failed to grow on SGA. The identification of these lipid-dependent yeasts was based on the ability to use certain polyoxyethylene sorbitan esters (Tweens 20, 40, 60, and 80), following the key for identification of species described by Guého et al. (9) and the Tween diffusion test proposed by Guillot et al. (13). The Cremophor EL assimilation test and the splitting of esculin described by Mayser et al. (16) were used as additional key characters for the differentiation of the species M. furfur, M. slooffiae and M. sympodialis. All isolates formed cream-colored, smooth, and glistening colonies with average diameters of 1.2 to 2.6 mm on modified Dixon's agar (36 g of malt extract, 6 g of peptone, 20 g of desiccated ox bile, 10 ml of Tween 40, 2 ml of glycerol, 2 ml of oleic acid, 12 g of agar per liter [pH 6.0]) (9) after 7 days of incubation at 32°C. These data differed from the 5-mm average diameter described by Guého et al. for this species under the same conditions (9). The cells were ovoid to globose (1.4 to 1.9 μm by 2.0 to 2.7 μm), and buds were formed on a narrow base. Sympodial budding was seen in some cells. They exhibited a positive catalase reaction. In the Tween diffusion test, all isolated yeasts utilized the four Tweens (20, 40, 60, and 80) showing inhibition areas around the Tween 80 and Tween 20 wells, as did the type strain M. sympodialis CBS 7222T under the same conditions. The isolates grew on glucose-peptone agar with 0.5% Tween 60 and 0.1% Tween 80, and they did not grow on 10% Tween 20. They did not assimilate Cremophor EL, and the splitting of esculin was strongly positive in 2 to 3 days. According to these findings, all lipid-dependent yeasts were identified as M. sympodialis (9, 13, 16).

Susceptibility tests on one isolate of each case were performed with antifungal tablets (Neo-Sensitabs; Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark) (5), using modified Dixon's agar. Inocula containing about 109 cells ml−1 were prepared from a fresh culture on modified Dixon's agar with 5 days of incubation at 32°C. The strains were sensitive to amphotericin B, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, miconazole, and clotrimazole. All isolates were resistant to 5-fluorocytosine.

Treatment.

The cats were treated topically with Conofite Forte (Esteve Veterinaria, Laboratorios Dr. Esteve S. A., Barcelona, Spain) (20 mg of miconazole, 5,000 IU of polymyxin B, 5 mg of prednisolone [each per ml]), 3 to 5 drops/ear twice a day for 10 days. The otitis successfully resolved after treatment of both cats.

Discussion.

Among the different Malassezia species, the non-lipid-dependent species M. pachydermatis can be isolated from the external ear canal and mucosae of healthy cats and cats with otitis externa and dermatitis (11). This species is considered a nonpathogenic, normal commensal organism which can become an opportunistic pathogen when the microclimatic factors are appropriate or the host's defense mechanism fails or is overwhelmed (15, 17). However, it is more frequently isolated from dogs than cats. In cats, the relative importance of M. pachydermatis in disease is less certain because it is found with equal frequency in clinically healthy cats and in those with otitis externa. M. pachydermatis has been identified in 50 to 83% of dogs with otitis externa and in 19% of cats with otitis externa (7).

In addition to this non-lipid-dependent species, the lipid-dependent species M. sympodialis (3), M. globosa (4), and M. furfur (6) may also colonize the skin and mucosae of healthy cats. In fact, cats and cheetah are the only carnivores in which the isolation of lipid-dependent species had been demonstrated (10). Recently, lipid-dependent species have been also reported in mixed cultures from canine and feline specimens, using identification techniques such as the Tween 80 diffusion test, the Cremophor EL assimilation test, and the splitting of esculin (22). In our opinion, pure cultures must be used to obtain a microbiological identification following this kind of technique. On the other hand, the role of lipid-dependent species in animal skin is still unclear. It has been mentioned that they can colonize the skin of different animals, but no skin disorder associated with lipid-dependent species in domestic animals has been mentioned to date, with the exception of a skin disorder in goats with the same typical lesions as tinea versicolor in humans (2). However, in that case, the isolation in vitro of the causal agent was unsuccessful. To our knowledge, our description herein is the first report of the isolation of lipid-dependent species of the genus Malassezia associated with skin disease in domestic animals. To date, this is the first isolation of M. sympodialis involved in otitis externa in cats.

The two cases of otitis were resolved successfully by topically treating the cats with Conofite Forte, which includes miconazole among other drugs. As previously mentioned, the isolates were sensitive to miconazole. Although in general, the in vitro antifungal susceptibilities of the different pathogenic fungi can be a valuable guide for the practitioner, reliable antifungal susceptibility testing is still poorly developed, especially for lipophilic yeasts. Recently, some testing conditions have been proposed as guidelines for a reference broth microdilution method (21), but the yeasts of the genus Malassezia are not included.

M. sympodialis seems to be the most lipid-dependent species isolated from healthy cats (3). Although M. pachydermatis can be involved in otitis externa in cats, it does not occur with the frequency it does in cases of otitis externa in dogs. Usually, practitioners diagnose this kind of otitis in the laboratory by microscopic examination of stained smears from otic swabs. For this reason, the presence of lipid-dependent Malassezia species in the smears may be ignored and/or the organism may be misidentified as M. pachydermatis. Nevertheless, as has been pointed out, this species has a different micromorphology. On the other hand, since culture media with lipid sources, such as SGA supplemented with olive oil, Leeming's medium, and modified Dixon's agar, are often recommended for the isolation of M. pachydermatis (7), the isolated yeasts could be misidentified as M. pachydermatis because their lipid dependence is not tested in a routine way. All of the arguments described above allow us to think that M. sympodialis could be more common in this microenvironment and could play a similar role as M. pachydermatis in otitis externa in cats.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ana Avellaneda (Ars Veterinaria) and Javier Mora (Consultori Veterinari Horta) for the samples kindly provided for this investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barber G R, Brown A E, Kiehn T E, Edwards F F, Armstrong D. Catheter-related Malassezia furfur fungemia in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 1993;95:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bliss E L. Tinea versicolor dermatomycosis in the goat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984;184:1512–1513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond R, Anthony R M, Dodd M, Lloyd D H. Isolation of Malassezia sympodialis from feline skin. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bond R, Howell S A, Haywood P J, Lloyd D H. Isolation of Malassezia sympodialis and Malassezia globosa from healthy pet cats. Vet Rec. 1997;141:200–201. doi: 10.1136/vr.141.8.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casals J B. Tablet sensivity testing of pathogenic fungi. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:719–722. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.7.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo M J, Abarca M L, Cabañes F J. Isolation of Malassezia furfur from a cat. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1573–1574. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1573-1574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene C E. Integumentary infections. Otitis externa. In: Greene C E, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1998. pp. 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guého E, Boekhout T, Ashbee H R, Guillot J, van Belkum A, Faergemann J. The role of Malassezia species in the ecology of human skin and as pathogens. Med Mycol. 1998;36:220–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guého E, Midgley G, Guillot J. The genus Malassezia with description of four new species. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:337–355. doi: 10.1007/BF00399623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillot J, Breugnot C, de Barros M, Chermette R. Usefulness of modified Dixon's medium for quantitative culture of Malassezia species from canine skin. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1998;10:384–386. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillot J, Chermette R, Guého E. Prévalence du genre Malassezia chez les mammifères. J Mycol Méd. 1994;4:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillot J, Guého E. The diversity of Malassezia yeasts confirmed by rRNA sequence and nuclear DNA comparisons. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1995;67:297–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00873693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guillot J, Guého E, Lesourd M, Midgley G, Chévrier G, Dupont B. Identification of Malassezia species. A practical approach. J Mycol Méd. 1996;6:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeming J P, Notman F H. Improved methods for isolation and enumeration of Malassezia furfur from human skin. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2017–2019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.2017-2019.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macy D W. Diseases of the ear. In: Ettinger S J, Feldman E C, editors. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1989. pp. 538–550. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayser P, Haze P, Papavassilis C, Pickel M, Gruender K, Guého E. Differentiation of Malassezia species: selectivity of Cremophor EL, castor oil and ricinoleic acid for M. furfur. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:208–213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18071890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeever P J, Globus H. Canine otitis externa. In: Bonagura J D, Kirk R W, editors. Kirk's current veterinary therapy: small animal practice XII. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1995. pp. 647–655. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mickelsen P A, Viano-Paulson M C, Stevens D A, Díaz P S. Clinical and microbiological features of infection with Malassezia pachydermatis in high-risk infants. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:1163–1168. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.6.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Midgley G. The diversity of Pityrosporum (Malassezia) yeasts in vivo and in vitro. Mycopathologia. 1989;106:143–153. doi: 10.1007/BF00443055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller G H, Kirk R W. Diseases of eyelids, claws, anal sacs, and ear canals. In: Scott D W, Miller W H, Griffin C E, editors. Small animal dermatology. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1995. pp. 956–989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard. Document M27-A. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raabe P, Mayser P, Weiß R. Demonstration of Malassezia furfur and M. sympodialis together with M. pachydermatis in veterinary specimens. Mycoses. 1998;41:493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Belkum A, Boekhout T, Bosboom R. Monitoring spread of Malassezia infections in a neonatal intensive care unit by PCR-mediated genetic typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2528–2532. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2528-2532.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welbel S F, McNeil M M, Pramanik A, Silberman R, Orbele A D, Midgley G, Crow S, Jarvis W R. Nosocomial Malassezia pachydermatis bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:104–108. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]