Abstract

This study investigates why some employees intend to leave their jobs when facing conflict between family responsibilities and job routines. The present study also reveals the moderating role of on-the-job embeddedness between role conflict and intention to leave the job. Drawing on conservation of resources theory, the paper investigates the buffering effect of the three on-the-job embeddedness components (fit, links, and sacrifice). Data were collected from banking officers because most of the employees have to face role conflict between family and job responsibilities, as banking is considered among the most stressful jobs. Collected data were analyzed by applying structural equation modeling. Results indicate that the role conflict significantly influences intention to leave the job. Furthermore, the study shows that on-the-job embeddedness moderates the relationship between role conflict and intention to leave. The results suggest that organizations can reduce turnover intention during times of work and life conflict by developing employee on-the-job embeddedness. This study provides some insights to managers on why many employees leave their jobs and how to overcome this problem. Management should also offer extra and available resources in periods of greater tension to minimize early thinking regarding quitting.

Keywords: role conflict, intention to leave, job embeddedness, Pakistan, bank employees

Introduction

Employee turnover is not a new trend. Millions of people around the world leave their jobs annually. Despite all the public benefits that are attached to being employed, employees decide to quit. The researchers found several variables that affect the choice to leave during periods of work-life imbalance (Aboobaker et al., 2017). Existing literature draws our attention to multiple factors which lead to the Intention of an employee to leave and employee turnover. Those factors include internal factors related to the job itself and external factors associated with a person’s personal and social life (Mansour and Tremblay, 2018). Numerous investigators have found that certain organizational factors, including organizational commitment, organizational support, and supervisors’ support, along with some social and personal stress factors, might trigger Intention to leave a job among employees (Zhang et al., 2019). Role conflict is one of those factors which might lead employees toward job quitting. Role conflict refers to one’s unpleasant experience, which one faces due to the confronting and clashing demands of different social roles and statuses (Anand and Vohra, 2020). Two types of role conflicts include intra-role conflicts and inter-role conflicts. Intra-role conflict refers to the conflict a person faces due to increased mental pressure and stress due to conflicting expectations and demands from one domain of life. For example, the tension in the job due to multiple responsibilities can be considered a result of the intra-role conflict. Another type of role conflict is an inter-role conflict that a person faces due to conflicting demands from different life domains (Mansour and Tremblay, 2016). For example, an employee’s inability to be a good parent or partner due to a demanding professional life can be considered the inter-role conflict that might lead them to quit their job (Dai et al., 2019).

When an employee leaves a job, they have to face two possible consequences. The person who leaves a job either joins another organization or is left unemployed (Lee et al., 2020). In the case of unemployment, a person faces several consequences. The financial situation of the quitter is an immediate and distressing outcome of sudden unemployment (Bayarcelik and Findikli, 2016). It is well documented that not every person gets a new job right after leaving an employer. Even for a few months, a break in the regular inflow of income can put the person into further distress (Samadi et al., 2020). Financial instability then leads to different issues related to a person’s health, mainly psychological conditions. Unemployed people commonly report depression and anxiety for a long time (Minamizono et al., 2019). Social outcomes emerge in the shape of worry about dependents’ financial security and the form of social gatherings being restricted (Jyoti and Rani, 2019).

Every organization aims to have high productivity and consistently increasing profitability. High profits are indicators of the success of companies. Employees are significant contributors to a company’s success (Gyensare et al., 2016). The consequences of employee turnover for the employer are frequently documented. An employee’s sudden departure can hinder the operations of an office for some time (Sun and Wang, 2017). It also affects team dynamics within an organization. Organizations invest a lot in their employees’ training (Cho et al., 2017). All the company’s investment in an employee is lost when a trained employee no longer continues to work in the organization (Lee, 2018). Highly motivated individuals serve as the driving forces of profit and competitiveness (Zimmerman et al., 2019). Along with the increase in productivity and profits, organizations try to have lower turnover as the managers are familiar with the importance of employee retention (Stamolampros et al., 2019). Numerous researchers have stressed the importance of employee retention and recommended incorporating retention strategies as fundamental principles in organizational policies (Degbey et al., 2021). Adoption of retention strategies is also recommended to small and medium sized business enterprises for the achievement of consistent productivity and rising profits (Alhmoud and Rjoub, 2019).

This research investigates if on-the-job embeddedness affects the connection between work-life conflict and an employee’s intention to leave. Job embeddedness theory describes an employee’s retention due to an employee’s unique set of ties to the organization. In addition, it has been shown that an employee’s embeddedness may serve as a buffer against bad events and ill circumstances. This study contributes to the work-life balance and job embeddedness literature by investigating whether on-the-job embeddedness moderates the effect of work-family conflict on employee leaving intention.

On the other hand, numerous attempts have been made to understand the association between role conflict and Intention to leave. Still, no investigations have been made so far which are specifically directed toward the banking sector. When it comes to the context of Pakistan, the literature seems even more limited on the subject. Therefore, this investigation’s purpose is the empirical explanation of the association between role conflict and Intention to leave and the role of job embeddedness as a mediator in their relationship in the banking sector of Pakistan. This study will contribute to the existing literature by producing information about the causal relationship among role conflict, Intention to leave, and job embeddedness. This study is also aimed to provide an empirical understanding of all these concepts in the context of Pakistan’s Banking sector for the development of effective retention policies by the banks.

The following paragraphs are a brief review of relevant literature and are followed up by the hypothesized relationships between focal constructs. Then the research methods, analyses, and findings are recorded and discussed. Finally, both the theoretical and managerial implications and the limitations and avenues for future research have been discussed.

Review of Literature

A review of the literature about the relevant concepts and sectors is narrated below.

Intention to Leave

Sasso et al. (2019) revealed that Intention to leave or intention to quit refers to the potential plans to leave the job with an employer. It is a global phenomenon. Multiple factors include personal factors and employers’ behavior, performance appraisal and feedback, absenteeism, burnout, lack of recognition, personal and professional advancement, miscommunication, and job satisfaction (Holland et al., 2019). A literature review of some of the critical factors that have been reported to be associated with leaving is presented in the following paragraphs.

Employers’ attitude has been reported frequently in the literature as an indicator that triggers the intention to leave in an employee (Meriläinen et al., 2019). The majority of the people who leave their job have mentioned the employers’ unprofessional attitude as the main factor that led them to quit. Numerous researchers have reported that employees are less likely to quit their jobs if they think their employers are professional (Chin et al., 2019). The second important factor that has been frequently used in the literature is appreciation and performance appraisal. Several researchers have narrated that workers feel motivated when their managers and colleagues appreciate their work (Lo et al., 2018). Positive feedback on one’s work is associated with improved performance. Employees have reported in numerous studies that appreciation inspires them to work better and harder with increased interest. However, investigators have noted that many organizations lack effective performance appraisal mechanisms (Yamaguchi et al., 2016).

de Oliveira et al. (2017) discussed that an ineffective appraisal system gives rise to a lack of recognition. Employees have reported that they work very hard to get credit for their contribution to an enterprise. As a result, they are left with a sense of worthlessness. This directly demotivates the workers and causes lessening interest in their work (Mihail, 2017). This affects the productivity of a firm negatively. Workers who left their jobs have informed us in the surveys that they were not concerned with the firm’s overall productivity due to lack of recognition of their efforts at the workplace. People do not give their best at work when their work is not credited (Bohle et al., 2017).

Mahomed and Rothmann (2020) expressed that leaving is damaging for both employees and employers. An employer’s investment in a managerial level employee’s training is wasted if they quits the job (Asakura et al., 2020). A new employee takes a lot of time to understand the organizational environment and working mechanism. An organization has to invest in a new employee’s training when an experienced manager leaves the organization (Domínguez Aguirre, 2019). If the intention to leave leads to job quitting, it can create personal, social, and psychological problems for the quitter (Loi et al., 2006).

Not every firm understands the importance of employee retention, as it has been reported that not all firms adopt retention strategies (MacIntosh and Doherty, 2010). However, many firms adopt different approaches and techniques to retain their workers. Retention strategies vary from firm to firm (Frye et al., 2020). Incentives, increments, competitive remuneration packages, promotions, appraisal systems, training, and recognition of work along an attractive working environment are among the tools commonly used by employers for employee retention (Silva et al., 2019).

Role Conflict

The concept of “role conflict” defines a kind of internal conflict in which job and family role obligations are at odds with one another to some degree, making it difficult to fulfill requirements in one area while having to meet them in the other (Zainal Badri and Wan Mohd Yunus, 2021). Both work and family roles may be defined by the obligations placed on the individual by their work colleagues and family members and the values the person has about their work and family role behavior. When work and family needs clash, it is easy to believe that the workplace is interfering with family happiness and pleasure (Díaz-Fúnez et al., 2021).

Role conflict may also arise when family issues interfere with job happiness and job performance. Dividing time between job and family (multiple roles) may lead to inter-role conflict since these responsibilities may deplete one-another’s resources (Del Pino et al., 2021). To fulfill the needs of one job, the expectations of the other roles are ignored. If family responsibilities come after the job, the family strain may detract from the ability to fulfill the job function (Gul et al., 2021).

Inter-role conflict and intra-role conflict are two commonly used concepts in the literature of role conflict. An inter-role conflict is a form of role conflict that refers to stressful conditions resulting from conflicting demands from different life spheres (Iannucci and MacPhail, 2018). Workers have frequently reported the inter-role conflict due to continuous pressure from the employer and the increasing demands of family members (Karim, 2017; Sarfraz et al., 2021). Intra-role conflict, another form of role conflict, is associated with a single role’s expectations and needs. It can occur due to either expectations in the workplace or family members’ demands (Grzywacz, 2020). The employees frequently report Intra-role conflict. Both inter-role conflict and intra-role conflict cause employees to experience role strain. Role strain is another often-used concept in the literature regarding role conflict (Wendling et al., 2018). Role strain can be explained as tension that a person experiences when he/she faces competing demands within one particular role and find it challenging to perform according to the expected roles (Jamil et al., 2021).

Inter-role conflict can occur due to multiple reasons, but role ambiguity is reported as a common reason people experience role conflict at the workplace (Wehner, 2016). Role ambiguity is when an employee lacks awareness about their job-related duties (Oviatt et al., 2017). Numerous researches demonstrate that employees who do not perform as per employers’ expectations are usually unclear about their responsibilities in the workplace (Purohit and Vasava, 2017). That role ambiguity is reported mainly as a result of miscommunication. Role ambiguity can be overcome through clear communication of job responsibilities and duties (Furtado et al., 2016).

Role conflict may also result from workers’ failure to manage their work and family (non-work) obligations on an equal footing (Yousaf et al., 2020). This kind of conflict may suggest that employees’ job duties interfere with their happiness and success in their personal lives or that employees’ personal lives interfere with their satisfaction and success at work (Naseem et al., 2020). Therefore, it is probable that role conflict will have adverse effects, such as stress and dissatisfaction, and interfere with the ability to fulfill work or family obligations (Baranik and Eby, 2016; Mohsin et al., 2021). Furthermore, this tension may result in voluntary turnover, according to studies conducted by Eby et al. (2014), which supports this assertion. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Role Conflict has a significant impact on intention to leave a job.

The Moderating Role of Job Embeddedness

The term “on-the-job embeddedness” refers to a worker’s connection to social ties formed at work, making them reluctant to quit the company (Jiang et al., 2012). A detailed explanation is given by Lee et al. (2004) about the effect of on- and off-the-job embeddedness on job performance, attitude related to firm citizenship, and also decrease and lower the impact of truancy on global turnover (Amjad et al., 2018). Sekiguchi et al. (2008) demonstrated that there is a strong bond between leadership-membership exchange (LMX) and task action, LMX and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), organization-based self-appreciation, and is reinforced by job embeddedness factor (which is the composition of on-the-job and off-the-job embeddedness). Karatepe (2012) has depicted that embeddedness reinforces the negative effect of well-known firm and co-worker support (Karatepe, 2012; Naseem et al., 2021) and also increments the impacts of appreciation of organizational and firm equity (Karatepe and Shahriari, 2014) on representative leaving out proposals (Dunnan et al., 2020a). A demonstration was given by Özçelik and Cenkci (2014) about employee embeddedness that a worker with a fundamental level of work embeddedness detailed a weaker interconnection between finding work and turnover than those workers who have lower levels of embeddedness. Burton et al. (2010) demonstrated some interconnection between paternalistic administration and work in-role execution. Peachey et al. (2014) have detailed research regarding embeddedness and have shown that the impact of unfurling theory-type stuns on worker progress can be weakened by embeddedness. It fortifies the effect on OCB. Peachey et al. (2014) demonstrated that employee embeddedness strengthened the connection between workers’ past encounters of work environment bullying and consequent work environment hostility. Al-Ghazali (2020) explained that worker embeddedness could fortify the effect of worker recognitions of procedural decency and transmission on danger evaluation and organizational rebuilding.

The Moderating Effect of On-the-Job Fit Embeddedness

This study claims that on-the-job fit embeddedness is a valuable resource for helping employees deal with work-life balance issues (Kiazad et al., 2014a). Work-life conflict is less likely to impact workers with greater fit embeddedness. Consequently, there is a minor link between work-family conflict and intention to leave and companies with lower fitness levels. Two mechanisms have been suggested:

First, those employees with a better person-job fit are more likely to have more essential work skills, making it easier for them to fulfill the ordinary demands of their position compared to employees with a worse fit (Dunnan et al., 2020b). Second, employees with low levels of person-job fit will deplete resources more quickly to fulfill the day-to-day work needs than those with high levels of person-job fit. Third, the extra depletion of resources that results from role conflict between the job and home domains adds to the stress and exhaustion felt in both fields (Al-Ghazali, 2020). As a result, workers who aren’t a good match for the company will be hurt more. As a result, workers who fit in well on the job are less likely to be impacted and less likely to be motivated to leave.

Second, workers who better match the work-family conflict needs of the workplace may potentially adapt. Fasbender et al. (2019) suggest that conflict between a person’s ideas and expectations and the reality they encounter prompts an employee to change their stance and attitudes. People that are more in sync are better able to find and create new workplace arrangements (Chan et al., 2019; Naseem et al., 2020b). Employees with better degrees of fit embeddedness will feel less of a negative impact as a result. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H2: On-the-job fit positively moderates the relationship of role conflict and intent leave job.

The Moderating Effect of On-the-Job Link Embeddedness

Employees who have a greater level of on-the-job link embeddedness are more likely to know more individuals at the organization and be more engaged in the organization’s matters than their counterparts (Lyu and Zhu, 2019). Because of this connectivity, workers have greater access to possibilities inside the organization and services like career sponsorship from higher-ranking colleagues (Coetzer et al., 2018). Thus, link embeddedness may be seen as a valuable resource that allows employees to more easily access ameliorating support services offered by the organization in which they work. This has the potential to operate in two ways. First, increasing levels of social connection throughout an organization may, in the first instance, offer personal support for those who are experiencing problems as a result of work-family conflict (Sender et al., 2018). Second, employees who have built up social capital can better identify and negotiate administrative support services, such as organizational work-life balance programs, feel more comfortable accessing these services, and obtaining supervisor support. In a recent study, researchers found that some employees are hesitant to use organizational support services and that employee use of family friendly corporate resources can be influenced by the quality of employee-manager relations (Jamil et al., 2021b). Workers with a greater degree of link embeddedness had an easier time implementing current ameliorative measures, resulting in a reduction in the experience of stress resulting from work and family conflict compared to employees with a lower level of link embeddedness. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: On-the-job link positively moderates the relationship of role conflict and intent leave job.

The Moderating Effect of On-the-Job Sacrifice Embeddedness

While fit and connection embeddedness has been suggested to mitigate the impact of work-life conflict on leaving intention, sacrifice embeddedness has been proposed to enhance that relationship, following Zhang et al., (2019). According to COR theory, workers with a higher level of sacrifice embeddedness are more likely to accumulate intrinsic resources than employees with a lower level of sacrifice embeddedness. When intrinsic resources are collected in larger quantities, there is a greater likelihood of eventual loss. At the same time, unlike instrumental resources, increases in intrinsic resource levels do not always result in an improvement in an entity’s ability either to withstand threats or obtain additional resources (Hobfoll, 2011).

According to COR theory, a threat to current resources will elicit a more significant response than an opportunity to acquire new resources or invest existing resources in the short term (Hobfoll, 2011). Employees with more to lose, such as high levels of intrinsic resources, will be more sensitive to risks, such as the depletion potential of work and life conflict since they have more to lose. Kiazad et al. (2014b) discovered that when confronted with a threat such as a psychological contract breach, employees with higher sacrifice embeddedness reacted more strongly in defense of their existing resources when compared to employees with lower sacrifice embeddedness (Kiazad et al., 2014). Those workers who had a high level of sacrifice embeddedness used a resource defense strategy to reduce their exposure to the resource-depleting danger, which was shown to be effective in that research.

According to the findings of this research, workers who have a higher level of sacrifice embeddedness are more likely to undertake resource-saving measures, which may include considering quitting the organization (Stewart and Wiener, 2021). As a result of being unable to ward off threats to resources or obtain replacement resources, workers who have made significant sacrifices are more inclined than employees who have less to lose than they are to contemplate quitting the organization to protect their existing resources (Amoah et al., 2021). Therefore, workers with greater degrees of sacrifice embeddedness are more likely to experience conflict at work and home, and they are also more likely to consider quitting their current position. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

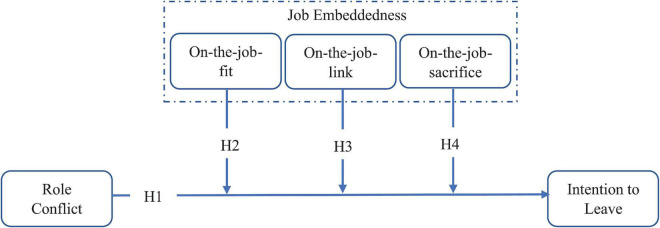

H4: On-the-job sacrifice positively moderates the relationship of role conflict and intent leave job (see Figure 1 for all relationships).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sample Size

The study samples include branch managers, operations managers, credit officers, and all officers, including grade one, two, and three major private banks situated in three big cities of Pakistan: Faisalabad, Lahore, and Islamabad. Also, we only included respondents who had been working in the banking sector for more than 5 years. The average experience of respondents in the banking sector was 8.5 years, and their time at their current location was 2.5 years. A pilot study with 30 participants was carried out. Since providing recommendations, revisions were made to the final questionnaire to make it more understandable for respondents. To ensure the content validity of the measures, three academic experts of human resource management analyzed and made improvements in the items of constructs. The experts searched for spelling errors, grammatical errors, and ensured that things were correct. The experts have proposed minor text revisions to role conflict and job sacrifice items and advised that the original number of items be maintained. The sample size was determined by using Kline (2015) proposed criterion. He suggested at least ten responses per item. Therefore, a minimum of 180 samples was needed, given the 18 items in this study. To increase reliability and validity, 250 questionnaires were distributed to research participants. At the time of scrutiny, 30 questionnaires were found incomplete, and these questionnaires were excluded, and the final sample is 220 respondents.

Questionnaire and Measurements

The study used items established from prior research to confirm the reliability and validity of the measures. All items are evaluated through five-point Likert-type scales where “1” (strongly disagree), “3” (neutral), and “5” (strongly agree).

Role Conflict was measured with five items adapted from the study of Netemeyer et al. (1996); the sample item is, “The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.”

Job Embeddedness, with its three dimensions: on-the-job fit, on-the-job link, and on-the-job sacrifice, was assessed with items adapted from the study (Felps et al., 2009). Job Embeddedness was measured with nine items; on-the-job fit consisted of three items, and the sample item is, “I feel like I am a good match for my organization.” The on-the-job link consisted of three items, and the sample item is, “I work closely with my coworkers.” Finally, on-the-job sacrifice consisted of three items, and the sample item is, “I would sacrifice a lot if I left this job.”

To assess the intention to leave, the four items were adopted from the work of Abrams et al. (1998) with the sample item, “In the next few years, I intend to leave this company.”

Demographic Characteristics

This study analyzed the data through Smart partial least squares (PLS), primary data was collected from 220 respondents, demographic characteristics of respondents such as age, gender, education, income, and experience are illustrated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

| Categories | Subcategories | Size | Percentage |

| Gender | Male | 150 | 68 |

| Female | 70 | 32 | |

| Total | 220 | 100 | |

| Age | 20–30 | 40 | 18 |

| 31–40 | 70 | 32 | |

| 41–50 | 80 | 36 | |

| 51 and above | 30 | 14 | |

| Total | 220 | 100 | |

| Family Status | Nuclear | 100 | 45 |

| Joint | 70 | 32 | |

| Extended | 50 | 23 | |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

Data Analysis

The study used PLS modeling using Smart-PLS 3.2.8 version (Ringle et al., 2015) as the numerical tool to analyze the structural and measurement model, as it can accommodate a smaller number of observations without normality assumptions and survey research is generally not normally distributed (Chin et al., 2003). Also, since data were collected using a single source, we followed Kock (2015) to test the common method bias using the full collinearity method. The test showed that all the VIFs were lower than five; thus, we can conclude common method bias is not a severe problem in our study (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2020).

Reliability and Validity of the Constructs

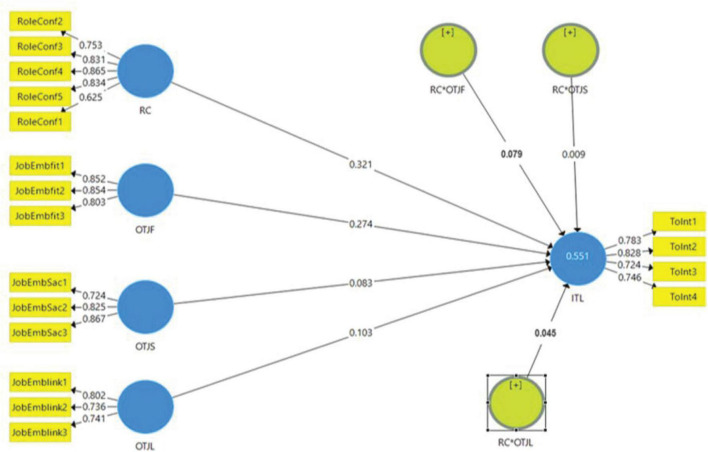

The Measurement model explains the relationships among the constructs and the indicator variables. As part of the measurement model assessment, all the indicators held factor loading greater than 0.60 and were retained in the model (Gefen and Straub, 2005). The reliability analysis is the first element of the measurement model, which contains composite reliability. According to Ramayah et al. (2018), the composite reliability’s required threshold value is 0.70. Subsequently, the indicators’ findings are greater than 0.7, confirming the measurement model’s composite reliability (see Table 2). The composite reliability values of all the constructs are also greater than 0.7, which further strengthens the reliability of all the variables (see Figure 2). Convergent Validity evaluates whether or not constructs measure what they are supposed to measure. In this study, convergent Validity was assessed by calculating the average-variance-extracted (AVE) that shows whether the construct variance can be described from the selected items (Fornell and Larcker, 1981a). According to Bagozzi and Yi (1988), the cut-off value for the average variance extracted is 0.5, and the Values of AVE of all constructs are greater than the recommended threshold, as shown in Table 2. This reflects the convergent Validity of the measurement model. Table 3 displays the discriminant validity assessment whereby the HTMT ratios were all below the 0.90 cut-off value. The confidence intervals do not include a zero or one, as suggested by Henseler et al. (2016). Thus, we can conclude that the measures used in this are reliable, valid, and distinct.

TABLE 2.

Reliability, validity, and descriptive of the measures.

| Constructs | Items | Items Loading | Skewness | Kurtosis | Alpha | CR | AVE | SE_skew | SE_Kurt |

| Intention to Leave | ITL1 | 0.783 | −1.3766 | 2.4867 | 0.7749 | 0.8541 | 0.5946 | 0.164 | 0.3266 |

| ITL2 | 0.828 | ||||||||

| ITL3 | 0.724 | ||||||||

| ITL4 | 0.746 | ||||||||

| On-the-job-fit | OTJF1 | 0.852 | −1.0434 | 1.2538 | 0.7909 | 0.8746 | 0.6993 | 0.164 | 0.3266 |

| OTJF2 | 0.854 | ||||||||

| OTJF3 | 0.803 | ||||||||

| On-the-job-link | OTJL1 | 0.802 | −0.8708 | 1.3622 | 0.7784 | 0.8042 | 0.5783 | 0.164 | 0.3266 |

| OTJL2 | 0.736 | ||||||||

| OTJL3 | 0.741 | ||||||||

| On-the-job-sacrifice | OTJS1 | 0.724 | −1.0955 | 1.4048 | 0.7566 | 0.8483 | 0.6522 | 0.164 | 0.3266 |

| OTJS2 | 0.825 | ||||||||

| OTJS3 | 0.867 | ||||||||

| Role Conflict | RC1 | 0.625 | −1.6315 | 2.4645 | 0.8784 | 0.8889 | 0.6184 | 0.164 | 0.3266 |

| RC2 | 0.753 | ||||||||

| RC3 | 0.831 | ||||||||

| RC4 | 0.865 | ||||||||

| RC5 | 0.834 |

FIGURE 2.

Measurement model.

TABLE 3.

Discriminant validity (HTMT Ratios).

| ITL | OTJF | OTJL | OTJS_ | RC | |

| ITL | |||||

| OTJF | 0.804 | ||||

| OTJL | 0.656 | 0.787 | |||

| OTJS_ | 0.632 | 0.711 | 0.877 | ||

| RC | 0.696 | 0.582 | 0.369 | 0.449 |

Discriminant Validity

In short, the Fornell and Larcker technique demonstrates discriminant validity when the square root of the AVE enhances the relationships between the measure and every other measure. To stimulate the measurement of the model’s discriminant validity, the AVE estimation of every construct is produced using the Smart-PLS algorithm, as shown in Table 3.

The values that lie in the off-diagonal are smaller than the average variance’s square root (highlighted on the diagonal), supporting the scales’ satisfactory discriminant validity. Consequently, the outcome affirmed that the Fornell and Larcker (1981b) model is met.

Structural Model

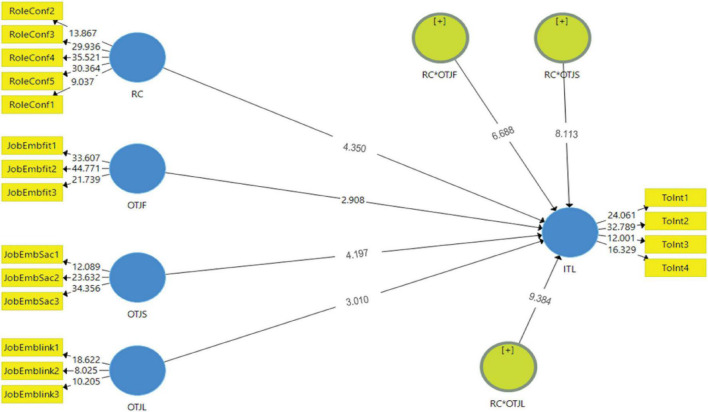

The structural model reflects the paths hypothesized in the research model and is assessed based on multicollinearity, coefficient of determination R2, predictive relevance Q2, and the paths’ significance (see Figure 3). The goodness of the model is determined by the structural path’s strength, determined by the R2 value for the dependent variable (Hair et al., 2014). All the VIFs were below five; thus, this confirms that the structural model results are not negatively affected by collinearity. Furthermore, following the thumb rules, the R2 values of intention to leave (0.551) exceed the minimum value of 0.1 suggested by Falk and Miller (1992), confirming a satisfactory predictability level. Furthermore, the Q2 value of the endogenous construct is considerably above zero, thus providing support for the model’s predictive relevance regarding the endogenous latent variables.

FIGURE 3.

Structural model.

Next, to assess the four hypotheses developed we ran a bootstrapping of 5,000 subsamples. First, we assessed the direct relationships before looking at the moderation effects. The results revealed a significant relationship between role conflict and intention to leave (β = 0.32, p < 0.01, BCI LL = 0.169 and BCI UL = 0.463) which gives positive support for H1 of our study. The moderation hypotheses of the job embeddedness in the path between role conflict and intention to leave (H2, H3, and H4) are tested using the two-stage continuous moderation analysis (Hair et al., 2017). The moderating effect of RC × OTJF → ITL (β = 0.047, p < 0.01, BCI LL = −0.193 and BCI UL = 0.298), RC × OTJL → ITL (β = 0.089, p < 0.01, BCI LL = −0.417 and BCI UL = 0.061), and RC × OTJS → ITL (β = 0.023, p < 0.01, BCI LL = −0.115 and BCI UL = 00.22) indicating the moderating effect are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. This gives support for H2, H3, and H4 of this study (see Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Hypotheses results.

| Hypothesis | Relationships | Std. Beta | Std. Error | t-value | p-value | BCI LL | BCI UL |

| H1 | RC → ITL | 0.32 | 0.075 | 4.292 | 0.000 | 0.169 | 0.463 |

| H2 | RC × OTJF → ITL | 0.047 | 0.096 | 6.688 | 0.000 | −0.193 | 0.298 |

| H3 | RC × OTJL → ITL | 0.089 | 0.077 | 11.385 | 0.000 | −0.417 | 0.061 |

| H4 | RC × OTJS → ITL | 0.023 | 0.083 | 8.113 | 0.010 | −0.115 | 0.22 |

| Endogenous construct | R 2 | Q 2 | |||||

| ITL | 0.551 | 0.295 | |||||

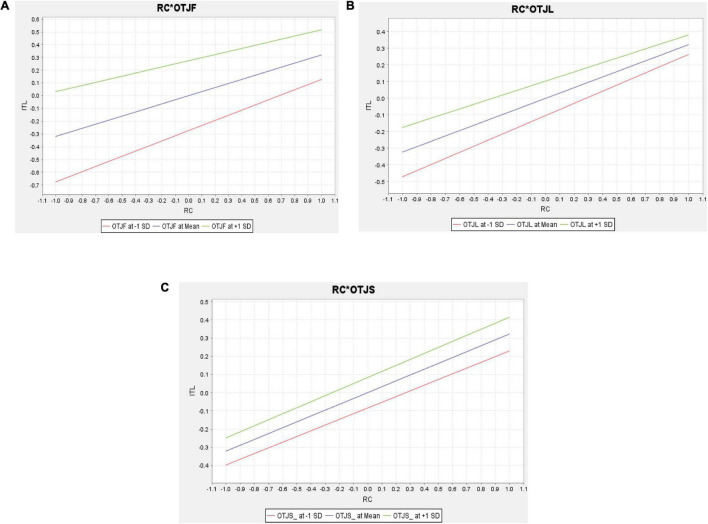

Also, for H2 the moderation graph indicates at the low level of On-the-Job Fit, there is a low impact of RC on ITL. However, increasing OTJF enhances the significant positive effect of RC on ITL (see Figure 4A). Moreover, the H3 moderation graph describes at the low level of the On-the-Job link there is a low impact of RC on ITL. Again, though, increasing OTJL augments the significant positive effect of RC on ITL (see Figure 4B). Finally, the final relationship graph shows at the low level of On the Job sacrifice, and there is a low impact of RC on ITL. Nevertheless, increasing OTJS improves the significant positive effect of RC on ITL (see Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Moderating effects.

Discussion and Conclusion

This present research aims to determine whether job abandonment moderates the relation between role conflict and intention to leave in the banking sector. For highly embedded employees in the banking sector, role conflict is a common occurrence. This study analyses job embeddedness in terms of employee retention. In particular, the results suggest that job embeddedness moderates the relationship between the WFC and job turnover intention. The results indicate that role conflict and job embeddedness are opposing factors that lead people to quit or remain within their banks. The results suggest that job embeddedness connects workers within the organizations (Lee et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2012) is supported by the theory of embeddedness (Mitchell and Lee, 2001). This means that job embedding has a beneficial influence when companies minimize “dysfunctional” revenue.

In terms of the suggested hypothesis, all three moderating effects are straightforward to comprehend. Employees who have a high level of linkage embeddedness have a bank of instrumental resources at their disposal that may help them cope more effectively with the difficulties of work and family conflict. The stronger the employee’s connection to the organization and the higher the linkage embeddedness, the better the employee can access and utilize a variety of existing organizational resources (Jung and Kim, 2021). Employees who are more integrated into their work will be more able to obtain inter-personal assistance from their colleagues and will be less reluctant and more effective in using existing organizational support systems due to their integration. So, employees reporting a lower connection between work and family conflict and leaving intention are more likely to be those who had more significant degrees of linkage embeddedness in their job.

Burton et al. (2010) showed that the embeddedness of workers reinforced the link between the history of bullying in a workplace and resulting violence in the workplace. Theory and studies on embedding work typically indicate that job embeddedness in the workplace has beneficial effects where the needs of workers and institutions are matched. In other terms, workers are trained to use working connections, health, and compromises to delegate services in the job domain and institutions to embedded employees. Because of the limitations generated by role conflict, our results indicate that an engaged employee with a high degree of embeddedness is more likely than a low embedded working employee to feel mental fatigue, remorse, and aggression. Thus, the high degree of job-embedded employees is more likely to be adversely impacted by role conflict. By concentrating on previously untested competing factors, this research leads to sparse work on the “dark side” of work integration (Sekiguchi et al., 2008; Burton et al., 2010; Allen et al., 2016).

This research provides deep insights into the moderating role of job embeddedness between role conflict and employees’ intention to leave and exposes significant shortcomings on the theory of work-building. This study also leads to limiting role conflict implementing and job embeddedness measures (Oviatt et al., 2017). In addition, the results indicate that those who are more deeply embedded in the job may improve their resource investment in the role conflict, as this relationship with turnover has been negatively impacted by a higher degree of job embeddedness. However, around the same period, these working parents became more vulnerable to mental fatigue, remorse, and hostilities because of resource drain. With these negative findings in mind and a high degree of embeddedness, this research goes beyond recent studies on the moderating impact of convergence between role conflict and turnover (Ringle et al., 2015).

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The studies provide several implications. First of all, this paper shows that Job embeddedness has a moderating impact on the relationship between role conflict and turnover intention. This contributes to the role conflict literature by extending the literature of job embeddedness. Essentially, the three elements of job embeddedness do not function as a unifying entity in this paper. Instead, there were differing impacts to the three components on the job. The fitness of embedding had no effect; embedding the link had an improving outcome, and embedding sacrifices had a multiplier effect. This shows no established linkage between embedded components on the job (Kiazad et al., 2014; Bohle et al., 2017). JET researchers should therefore use the three on-the-job parts instead of combined measures such as job integration or work-based embedding. Second, this article shows the efficient justification of how job embedders moderates the impact of role conflict on the employee’s intention of turnover by COR theory. This research adds to an earlier study’s findings into role conflict, strain, and burnout that explains the impact of work and family conflict on the depletion and acquisition of employee resources (Ghosh et al., 2017).

In addition to that, this paper would discuss plans to establish processes to understand how work incorporation impacts perceptions and attitudes (Kiazad et al., 2014). Finally, in connection with this study, the increasing COR research describes the influence of employee embeddedness as a form of resource abundance (Kiazad et al., 2014; Wehner, 2016).

This study has three Practical Implications. Firstly, by improving the usage by workers of current changes in the company to minimize the impact of role conflict, the detrimental effects of role conflict will be minimized. This research indicates that workers with stronger linkage embeddedness are more capable of using interpersonal and organizational resources. The administration would enhance the efficiency of existing ameliorating arrangements to increase employee interaction, subordinates, and organization (Holtom, 2016). Finally, the design of corporate training programs, the growth relating to teamwork judgment, organizational training and professional development programs, social networks within the company, and employee recruiting schemes are used to improve employee engagement embedding (Treuren, 2019).

Secondly, introduce measures to make employees’ connections to coworkers, bosses, and the company more effective. To create a relationship between employees and the company, mentorship programs may be set up. In addition, teams can have work and decision-making responsibilities expanded, in-house training and career development programs implemented, and referral systems used to hire employees. The various programs may be tailored to the preferences and requirements of different groups of employees.

Thirdly, even though workers with greater sacrifice embeddedness had fewer intentions to leave their jobs, these individuals are more sensitive to work and family conflict than employees with lower levels of sacrifice embeddedness. Therefore, at times of more conflict, management may offer extra and readily available ameliorative services to reduce the likelihood of early departure thoughts.

Limitations and Further Research

There are also limitations to this study. First, it employs cross-sectional measures and studies in social sciences to deduce the complexities of workers’ behavior. Longitudinal research is required to explain the effect and the purpose of job embedding on role conflict and turnover intention. Second, the research is focused on workers’ expectations and is thus susceptible to social desirability and the usual empirical biases. While the typical process bias in this study is minimal, more analysis could minimize the error of parameter estimation by having actual data on turnover or from various sources, for example, a supervisor or colleague, as the periods, have differed. Thirdly, the sample size is small (n = 220), which may have an issue of generalizability, leading to Type 2 errors and is also limited to the study. Finally, the limited size of the feminine cohort excluded substantial gender disparities from being investigated.

Further experiments should strive to obtain more significant balanced populations so that that gender effects can be compared. Furthermore, to determine the paper’s results, a single set of data from one sector of Pakistan was used; the findings are not necessarily generalizable. Uncertain jobs inside and outside the company may be calculated to be a biased estimation. The generalizability of these results would be explained further analysis into other geographic, social, and economic contexts. This paper outlines a structure for the influence of job embeddedness and role conflict and has defined new problems to address.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was partly supported by “National Social Science Foundation of China” (No. 19ZDA081).

References

- Aboobaker N., Edward M., Pramatha K. (2017). Work–family conflict, family–work conflict and intention to leave the organization: evidences across five industry sectors in India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 18 524–536. 10.1177/0972150916668696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams D., Ando K., Hinkle S. (1998). Psychological attachment to the group: cross-cultural differences in organizational identification and subjective norms as predictors of workers’ turnover intentions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 24 1027–1039. 10.1177/01461672982410001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazali B. M. (2020). Transformational leadership, career adaptability, job embeddedness and perceived career success: a serial mediation model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 41 993–1013. 10.1108/LODJ-10-2019-0455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alhmoud A., Rjoub H. (2019). Total rewards and employee retention in a Middle Eastern context. SAGE Open 9:2158244019840118. [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. G., Peltokorpi V., Rubenstein A. L. (2016). When “embedded” means “stuck”: moderating effects of job embeddedness in adverse work environments. J. Appl. Psychol. 101:1670. 10.1037/apl0000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amjad A., Amjad F., Jamil K., Yousaf S. (2018). Moderating role of self-congruence: impact of brand personality on brand attachment through the mediating role of trust. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 10 13–22. 10.22610/imbr.v10i1.2144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amoah V. S., Annor F., Asumeng M. (2021). Psychological contract breach and teachers’ organizational commitment: mediating roles of job embeddedness and leader-member exchange. J. Educ. Adm. 59 634–649. 10.1108/JEA-09-2020-0201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A., Vohra V. (2020). The impact of organisation work environment on job satisfaction, affective commitment, work-family conflict and intention to leave: a study of SMEs in India. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 41 173–196. 10.1504/IJESB.2020.109931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura K., Asakura T., Satoh M., Watanabe I., Hara Y. (2020). Health indicators as moderators of occupational commitment and nurses’ intention to leave. Jpn J. Nurs. Sci. 17:e12277. 10.1111/jjns.12277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R. P., Yi Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16 74–94. 10.1007/BF02723327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baranik L. E., Eby L. (2016). Organizational citizenship behaviors and employee depressed mood, burnout, and satisfaction with health and life. Pers. Rev. 45 626–642. 10.1108/PR-03-2014-0066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayarcelik E. B., Findikli M. A. (2016). The mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relation between organizational justice perception and intention to leave. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 235 403–411. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.11.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohle P., Knox A., Noone J., Mc Namara M., Rafalski J., Quinlan M. (2017). Work organisation, bullying and intention to leave in the hospitality industry. Employee Relat. 39 446–458. 10.1108/ER-07-2016-0149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton J. P., Holtom B. C., Sablynski C. J., Mitchell T. R., Lee T. W. (2010). The buffering effects of job embeddedness on negative shocks. J. Vocat. Behav. 76 42–51. 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W. L., Ho J. A., Sambasivan M., Ng S. I. (2019). Antecedents and outcome of job embeddedness: evidence from four and five-star hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 83 37–45. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chin W., Guo Y.-L. L., Hung Y.-J., Hsieh Y.-T., Wang L.-J., Shiao J. S.-C. (2019). Workplace justice and intention to leave the nursing profession. Nurs. Ethics 26 307–319. 10.1177/0969733016687160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin W. W., Marcolin B. L., Newsted P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 14 189–217. 10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018 19642375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.-N., Rutherford B. N., Friend S. B., Hamwi G. A., Park J. (2017). The role of emotions on frontline employee turnover intentions. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 25 57–68. 10.1080/10696679.2016.1235960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer A., Inma C., Poisat P., Redmond J., Standing C. (2018). Job embeddedness and employee enactment of innovation-related work behaviours. Int. J. Manpow. 39 222–239. 10.1108/IJM-04-2016-0095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.-D., Zhuang W.-L., Huan T.-C. (2019). Engage or quit? The moderating role of abusive supervision between resilience, intention to leave and work engagement. Tour. Manag. 70 69–77. 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.07.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira D. R., Griep R. H., Portela L. F., Rotenberg L. (2017). Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17:21. 10.1186/s12913-016-1949-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degbey W. Y., Rodgers P., Kromah M. D., Weber Y. (2021). The impact of psychological ownership on employee retention in mergers and acquisitions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 31:100745. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2020.100745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino H. E., Steers W. N., Lee M., McCuller J., Hays R. D., Harawa N. T. (2021). Measuring gender role conflict, internalized stigma, and racial and sexual identity in behaviorally bisexual Black men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 10.1007/s10508-021-01925-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Fúnez P. A., Salvador-Ferrer C. M., García-Tortosa N., Mañas-Rodríguez M. A. (2021). Are job demands necessary in the influence of a transformational leader? The moderating effect of role conflict. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:3630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Aguirre L. R. (2019). The mediating effects of external factors on intention to leave and organizational factors of hotel industry. Contaduría Adm. 64 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dunnan L., Jamil K., Abrar U., Ali S., Awan F. H., Ali S. (2020a). “Digital generators and consumers buying behavior,” in Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur. 10.1109/iCoMET48670.2020.9073931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnan L., Jamil K., Abrar U., Arain B., Guangyu Q., Awan F. H. (2020b). “Analyzing the green technology market focus on environmental performance in Pakistan,” in Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur. 10.1109/iCoMET48670.2020.9074084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eby S. L., Anderson T. M., Mayemba E. P., Ritchie M. E. (2014). The effect of fire on habitat selection of mammalian herbivores: the role of body size and vegetation characteristics. J. Anim. Ecol. 83 1196–1205. 10.1111/1365-2656.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk R. F., Miller N. B. (1992). A Primer for Soft Modeling. Akron, OH: University of Akron Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fasbender U., Van der Heijden B. I., Grimshaw S. (2019). Job satisfaction, job stress and nurses’ turnover intentions: the moderating roles of on-the-job and off-the-job embeddedness. J. Adv. Nurs. 75 327–337. 10.1111/jan.13842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felps W., Mitchell T. R., Hekman D. R., Lee T. W., Holtom B. C., Harman W. S. (2009). Turnover contagion: how coworkers’ job embeddedness and job search behaviors influence quitting. Acad. Manag. J. 52 545–561. 10.5465/amj.2009.41331075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D. F. (1981a). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 39–50. 10.1177/002224378101800104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D. F. (1981b). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18 382–388. 10.1177/002224378101800313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frye W. D., Kang S., Huh C., Lee M. J. M. (2020). What factors influence Generation Y’s employee retention in the hospitality industry?: An internal marketing approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 85 102352. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furtado L., Sobral F., Peci A. (2016). Linking demands to work-family conflict through boundary strength. J. Manage. Psychol. 31 1327–1342. 10.1108/JMP-11-2015-0408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gefen D., Straub D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 16:5. 10.17705/1CAIS.01605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D., Sekiguchi T., Gurunathan L. (2017). Organizational embeddedness as a mediator between justice and in-role performance. J. Bus. Res. 75 130–137. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz A. (2020). Indonesia’s (inter) national role as a Muslim democracy model: effectiveness and conflict between the conception and prescription roles. Pac. Rev. 33 728–756. 10.1080/09512748.2019.1585387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gul R. F., Liu D., Jamil K., Baig S. A., Awan F. H., Liu M. (2021). Linkages between market orientation and brand performance with positioning strategies of significant fashion apparels in Pakistan. Fashion Textiles 8 1–19. 10.1186/s40691-021-00254-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gyensare M. A., Anku-Tsede O., Sanda M.-A., Okpoti C. A. (2016). Transformational leadership and employee turnover intention. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 12 243–266. 10.1108/WJEMSD-02-2016-0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J. F., Jr., Sarstedt M., Hopkins L., Kuppelwieser V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 26 106–121. 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J. F., Hult G. T. M., Ringle C. M., Sarstedt M., Thiele K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45 616–632. 10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Hubona G., Ray P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 116 2–20. 10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Holland P., Tham T. L., Sheehan C., Cooper B. (2019). The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Appl. Nurs. Res. 49 70–76. 10.1016/j.apnr.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtom B. C. (2016). Job Embeddedness, Employee Commitment, and Related Constructs Handbook of Employee Commitment. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Iannucci C., MacPhail A. (2018). One Teacher’s experience of teaching physical education and another school subject: an inter-role conflict? Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 89 235–245. 10.1080/02701367.2018.1446069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil K., Hussain Z., Gul R. F., Shahzad M. A., Zubair A. (2021a). The effect of consumer self-confidence on information search and share intention. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 10.1108/IDD-12-2020-0155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil K., Liu D., Gul R. F., Hussain Z., Mohsin M., Qin G., et al. (2021b). Do remittance and renewable energy affect CO2 emissions? An empirical evidence from selected G-20 countries. Energy Environ. 10.1177/0958305X211029636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Liu D., McKay P. F., Lee T. W., Mitchell T. R. (2012). When and how is job embeddedness predictive of turnover? A meta-analytic investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 97:1077. 10.1037/a0028610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung N., Kim M. (2021). Assessing work-family conflict experienced by chinese parents of young children: validation of the Chinese version of the work and family conflict scale. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 10.1007/s10578-021-01236-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyoti J., Rani A. (2019). Role of burnout and mentoring between high performance work system and intention to leave: moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Res. 98 166–176. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O. M. (2012). The effects of coworker and perceived organizational support on hotel employee outcomes: the moderating role of job embeddedness. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 36 495–516. 10.1177/1096348011413592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O. M., Shahriari S. (2014). Job embeddedness as a moderator of the impact of organisational justice on turnover intentions: a study in Iran. Int. J. Tour. Res. 16 22–32. 10.1002/jtr.1894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karim M. F. (2017). Role conflict and the limits of state identity: the case of Indonesia in democracy promotion. Pac. Rev. 30 385–404. 10.1080/09512748.2016.1249908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiazad K., Kraimer M., Seibert S. (2014a). A job embeddedness perspective on responses to psychological contract fulfillment. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2014 12362–12362. 10.5465/ambpp.2014.12362abstract [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiazad K., Seibert S. E., Kraimer M. L. (2014b). Psychological contract breach and employee innovation: a conservation of resources perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 87 535–556. 10.1111/joop.12062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2015). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kock N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E Collab. 11 1–10. 10.4018/ijec.2015100101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. (2018). Employee turnover and organizational performance in US federal agencies. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 48 522–534. 10.1177/0275074017715322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. E., MacPhee M., Dahinten V. S. (2020). Factors related to perioperative nurses’ job satisfaction and intention to leave. Jpn J. Nurs. Sci. 17:e12263. 10.1111/jjns.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. W., Mitchell T. R., Sablynski C. J., Burton J. P., Holtom B. C. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 47 711–722. 10.5465/20159613 20159613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. Y., Chien L. Y., Hwang F. M., Huang N., Chiou S. T. (2018). From job stress to intention to leave among hospital nurses: a structural equation modelling approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 74 677–688. 10.1111/jan.13481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi R., Hang-Yue N., Foley S. (2006). Linking employees’ justice perceptions to organizational commitment and intention to leave: the mediating role of perceived organizational support. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 79 101–120. 10.1348/096317905X39657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Y., Zhu H. (2019). The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: a job embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 158 1083–1095. 10.1007/s10551-017-3741-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh E. W., Doherty A. (2010). The influence of organizational culture on job satisfaction and intention to leave. Sport Manag. Rev. 13 106–117. 10.1016/j.smr.2009.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahomed F. E., Rothmann S. (2020). Strength use, training and development, thriving, and intention to leave: the mediating effects of psychological need satisfaction. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 50 24–38. 10.1177/0081246319849030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour S., Tremblay D.-G. (2016). How the need for “leisure benefit systems” as a “resource passageways” moderates the effect of work-leisure conflict on job burnout and intention to leave: a study in the hotel industry in Quebec. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 27 4–11. 10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour S., Tremblay D.-G. (2018). Work–family conflict/family–work conflict, job stress, burnout and intention to leave in the hotel industry in Quebec (Canada): moderating role of need for family friendly practices as “resource passageways”. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 29 2399–2430. 10.1080/09585192.2016.1239216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meriläinen M., Nissinen P., Kõiv K. (2019). Intention to leave among bullied university personnel. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 33 1686–1704. 10.1108/IJEM-01-2018-0038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mihail P. V. K. D. M. (2017). Linking innovative human resource practices, employee attitudes and intention to leave in healthcare services. Employee Relat. 39 34–53. 10.1108/ER-11-2015-0205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minamizono S., Nomura K., Inoue Y., Hiraike H., Tsuchiya A., Okinaga H., et al. (2019). Gender division of labor, burnout, and intention to leave work among young female nurses in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:2201. 10.3390/ijerph16122201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T. R., Lee T. W. (2001). The unfolding model of voluntary turnover and job embeddedness: foundations for a comprehensive theory of attachment. Res. Organ. Behav. 23 189–246. 10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23006-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin M., Zhu Q., Naseem S., Sarfraz M., Ivascu L. (2021). Mining industry impact on environmental sustainability, economic growth, social interaction, and public health: an application of semi-quantitative mathematical approach. Processes 9:972. 10.3390/pr9060972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naseem S., Fu G. L., Mohsin M., Aunjam M. S., Rafiq M. Z., Jamil K., et al. (2020a). Development of an inexpensive functional textile product by applying accounting cost benefit analysis. Ind. Textila 71 17–22. 10.35530/IT.071.01.1692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naseem S., Fu G. L., Mohsin M., Rehman M. Z.-U., Baig S. A. (2020b). Semi-quantitative environmental impact assessment of khewra salt mine of Pakistan: an application of mathematical approach of environmental sustainability. Min. Metall. Explor. 37 1185–1196. 10.1007/s42461-020-00214-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naseem S., Mohsin M., Hui W., Liyan G., Penglai K. (2021). The investor psychology and stock market behavior during the initial era of COVID-19: a study of China, Japan, and the United States. Front. Psychol. 12 16. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer R. G., Boles J. S., McMurrian R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 81:400. 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oviatt D. P., Baumann M. R., Bennett J. M., Garza R. T. (2017). Undesirable effects of working while in college: work-school conflict, substance use, and health. J. Psychol. 151 433–452. 10.1080/00223980.2017.1314927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçelik G., Cenkci T. (2014). Moderating effects of job embeddedness on the relationship between paternalistic leadership and in-role job performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 150 872–880. [Google Scholar]

- Peachey J. W., Burton L. J., Wells J. E. (2014). Examining the influence of transformational leadership, organizational commitment, job embeddedness, and job search behaviors on turnover intentions in intercollegiate athletics. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 35 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit B., Vasava P. (2017). Role stress among auxiliary nurses midwives in Gujarat, India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17:69. 10.1186/s12913-017-2033-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah T., Cheah J., Chuah F., Ting H., Memon M. (2018). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using smartPLS 3.0 An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle C., Wende S., Becker J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi L., Bagheri M. S., Sadighi F., Yarmohammadi L. (2020). An investigation into EFL instructors’ intention to leave and burnout: exploring the mediating role of job satisfaction. Cogent Educ. 7:1781430. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández M. I., Gismera-Tierno E., Labrador-Fernández J., Fernández-Fernández J. L. (2020). Encountering suffering at work in health religious organizations: a partial least squares path modeling case-study. Front. Psychol. 11:1424. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfraz M., Mohsin M., Naseem S., Kumar A. (2021). Modeling the relationship between carbon emissions and environmental sustainability during COVID-19: a new evidence from asymmetric ARDL cointegration approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso L., Bagnasco A., Catania G., Zanini M., Aleo G., Watson R., et al. (2019). Push and pull factors of nurses’ intention to leave. J. Nurs. Manag. 27 946–954. 10.1111/jonm.12745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi T., Burton J. P., Sablynski C. J. (2008). The role of job embeddedness on employee performance: the interactive effects with leader–member exchange and organization-based self-esteem. Pers. Psychol. 61 761–792. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00130.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sender A., Rutishauser L., Staffelbach B. (2018). Embeddedness across contexts: a two-country study on the additive and buffering effects of job embeddedness on employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 28 340–356. [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. R. A., de Amorim Carvalho J. C., Dias A. L. (2019). Determinants of Employee Retention: A Study of Reality in Brazil Strategy and Superior Performance of Micro and Small Businesses in Volatile Economies. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stamolampros P., Korfiatis N., Chalvatzis K., Buhalis D. (2019). Job satisfaction and employee turnover determinants in high contact services: insights from Employees’ Online reviews. Tour. Manag. 75 130–147. 10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. L., Wiener K. K. K. (2021). Does supervisor gender moderate the mediation of job embeddedness between LMX and job satisfaction? Gend. Manag. Int. J. 36 536–552. 10.1108/GM-07-2019-0137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R., Wang W. (2017). Transformational leadership, employee turnover intention, and actual voluntary turnover in public organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 19 1124–1141. 10.1080/14719037.2016.1257063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treuren G. J. (2019). Employee embeddedness as a moderator of the relationship between work and family conflict and leaving intention. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 30 2504–2524. 10.1080/09585192.2017.1326394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner L. E. (2016). Inter-role conflict, role strain and role play in Chile’s relationship with Brazil. Bull. Lat. Am. Res. 35 64–77. 10.1111/blar.12413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wendling E., Kellison T. B., Sagas M. (2018). A conceptual examination of college athletes’ role conflict through the lens of conservation of resources theory. Quest 70 28–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Inoue T., Harada H., Oike M. (2016). Job control, work-family balance and nurses’ intention to leave their profession and organization: a comparative cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 64 52–62. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf M. R., Jamil K., Roman M., Shabbir Ch M., Shahid A. (2020). Impact of training, job rotation and managerial coaching on employee commitment in context of BankingSector. Sukkur IBA J. Manag. Bus. 7 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zainal Badri S. K., Wan Mohd Yunus W. M. A. (2021). The relationship between academic vs. family/personal role conflict and Malaysian students’ psychological wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021 1–13. 10.1080/0309877X.2021.1884210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Fan C., Deng Y., Lam C. F., Hu E., Wang L. (2019). Exploring the interpersonal determinants of job embeddedness and voluntary turnover: a conservation of resources perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 29 413–432. 10.1111/1748-8583.12235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wu X., Wan X., Hayter M., Wu J., Li S., et al. (2019). Relationship between burnout and intention to leave amongst clinical nurses: the role of spiritual climate. J. Nurs. Manag. 27 1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman R. D., Swider B. W., Boswell W. R. (2019). Synthesizing content models of employee turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 58 99–114. 10.1002/hrm.21938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.