Abstract

Objectives:

In 2010, WHO published guidelines emphasizing parasitological confirmation of malaria prior to treatment. We present data on changes in fever case management in a low malaria transmission setting of northern Tanzania after 2010.

Methods:

We compared diagnoses, treatments, and outcomes from two hospital-based prospective cohort studies, Cohort 1 (2011–2014) and Cohort 2 (2016–2019), that enrolled febrile children and adults. All participants underwent quality-assured malaria blood smear-microscopy. Participants who were malaria smear-microscopy negative but received a diagnosis of malaria or received an antimalarial were categorized as malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment, respectively.

Results:

We analyzed data from 2,098 participants. The median (IQR) age was 27 (3–43) years and 1,047 (50.0%) were female. Malaria was detected in 23 (2.3%) participants in Cohort 1 and 42 (3.8%) in Cohort 2, (P = 0.059). Malaria over-diagnosis occurred in 334 (35.0%) participants in Cohort 1 and 190 (17.7%) in Cohort 2, (P <0.001). Malaria over-treatment occurred in 528 (55.1%) participants in Cohort 1 and 196 (18.3%) in Cohort 2, (P <0.001). There were 30 (3.1%) deaths in Cohort 1 and 60 (5.4%) in Cohort 2, (P = 0.007). All deaths occurred among smear-negative participants.

Conclusion:

We observed a substantial decline in malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment among febrile inpatients in northern Tanzania between two time periods after 2010. Despite changes, some smear-negative participants were still diagnosed and treated for malaria. Our results highlight the need for continued monitoring of fever case management across different malaria epidemiologic settings in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: Africa, Tanzania, Fever, Malaria, Antimalarials

Sustainable Development Goal: Good health and wellbeing

INTRODUCTION

Malaria remains a major global health problem with an estimated 228 million illnesses and 405,000 deaths reported in 2018 (1). Early diagnosis and treatment of malaria are critical for reducing disease and transmission and for preventing deaths. However, rational use of antimalarials has been a long-standing challenge in many resource-poor settings. In large part this stems from clinical management guidelines that emphasized presumptive treatment of malaria for persons, especially children, in malaria-endemic settings presenting with fever (2). While presumptive treatment of malaria may be appropriate in certain contexts, widespread adoption of this strategy contributed to an overuse of antimalarials, leading to unnecessary adverse events, wasted health resources, and inadequate treatment of infections other than malaria (3–7).

In recognition of the negative public health consequences of antimalarial overuse, in 2010 WHO recommended a policy of parasitological confirmation for all patients with suspected malaria prior to treatment initiation (8). This ‘test and treat’ strategy for malaria has been emphasized in all subsequent WHO guidelines and has been largely incorporated into fever case management guidelines of malaria-endemic countries (8–10). According to the latest WHO data, the proportion of persons suspected to have malaria who received a parasitological diagnosis in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA), the region with highest malaria burden, increased from approximately 40% in 2010 to more than 80% in 2018 (1).

Parasite-based diagnosis, either by blood smear-microscopy or malaria rapid diagnostic test (mRDT), is now considered a central pillar of fever case management and is promoted as a strategy to reduce antimalarial use and prompt clinicians to look for alternative causes of fever (11). In the years since the WHO policy shift, studies have found that incorporating malaria diagnostic testing into fever case management generally results in desired impacts on rational antimalarial use (11,12). Yet, the true public health impact of the shift to a ‘test and treat’ strategy remains uncertain for a number of reasons. First, many studies evaluating the impact of malaria diagnostic testing on antimalarial use were intervention trials. Results generated under trial conditions may not be observed in routine clinical practice, and the short-term positive impacts on clinician diagnostic and treatment decisions may not portend long-term trends. Second, fever case management across many settings in sSA often culminates in the prescription of an antimicrobial (12–15). Not surprisingly, studies have found that desired reductions in antimalarial use are often associated with a shift towards increased prescribing of antibacterials (12,16–18). Third, it remains unclear to what extent the integration of malaria diagnostic testing into fever case management has improved the health outcomes of patients with non-malaria fever. Studies prior to the WHO policy shift suggested that overattributing fever as malaria was associated with poor health outcomes due to a failure to promptly recognize and treat alternative causes of fever, particularly invasive bacterial infections (3,19). Since the WHO policy shift, few studies have evaluated the impact of malaria diagnostic and treatment practices on patient outcomes (11).

Continued evaluation of the impact of the WHO 2010 policy shift on fever case management are needed across different malaria endemicity settings. We previously described trends in fever case management among febrile inpatients in a low-malaria transmission setting in northern Tanzania between the periods of 2007–2008 and 2011–2012 (20). We observed persistent malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment in both study periods despite the WHO policy shift. In the years since that publication, Tanzania’s national guidelines have emphasized testing by microscopy or mRDT for all patients with suspected malaria prior to the initiation of antimalarials (21). In addition, national campaigns have encouraged community members with fever to seek malaria testing while also encouraging providers to withhold malaria treatment for those with negative test results (20). To this end, our current study presents an analysis of trends in fever case management among hospitalized patients enrolled in northern Tanzania between the periods 2011–2014 and 2016–2019. Specifically, the objective of the present study is to understand if consistent emphasis on the ‘test and treat’ strategy in WHO and Tanzanian guidelines has substantially changed the practice of malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment, and to examine the extent to which clinician malaria diagnostic and treatment behaviors are associated with patient outcomes in the context of inpatient fever case management.

METHODS

Study Setting

We conducted prospective hospital-based fever surveillance studies at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) and Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital (MRRH) in Moshi, Tanzania during the periods of 26 September 2011 through 31 May 2014, henceforth referred to as Cohort 1, and 7 September 2016 through 31 May 2019, henceforth referred to as Cohort 2. In our previous study evaluating trends in fever case management, Cohort 1 (referred to as Cohort 2 in our previous study) was evaluated for the years 2011–2012 only, and the analysis was restricted to adolescent and adult participants (20). KCMC is a 630-bed zonal referral hospital that serves the northern zone of Tanzania. KCMC is operated by the Good Samaritan Foundation, a not-for-profit organization of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Tanzania, but receives substantial support from the Ministry of Health towards staffing and supplies. MRRH is a 300-bed public regional hospital serving the Kilimanjaro Region. Malaria transmission intensity is low in the Kilimanjaro Region (22,23). HIV seroprevalence among adults age 15–49 years was 3.8% in 2011 and 2.2% in 2016 (22,24).

Study Procedures

Febrile pediatric and adult patients at KCMC and MRRH were prospectively enrolled during both study periods. From Monday through Friday, we screened all patients in the adult and pediatric medical wards of KCMC and MRRH within 24 hours of admission. Patients were eligible for enrollment if they had a tympanic temperature ≥38.0°C or a subjective report of fever within the previous 72 hours. After obtaining informed consent, a trained study team member conducted a standardized clinical history and physical examination. Prior antibacterial and antimalarial use were defined as self-reported use of these medications for the presenting illness prior to admission. At the time of hospital discharge, a study team member completed a case report form that included admission and discharge diagnoses, medications administered during hospitalization, and vital status at the time of discharge. For Cohort 2, we collected self-reported malaria diagnostic testing history prior to hospitalization. However, we did not collect data regarding the type of malaria diagnostic testing performed.

We calculated severity of illness at admission using the Universal Vital Assessment (UVA) score which is based on temperature, heart and respiratory rates, systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, Glasgow Coma Scale, and HIV infection status. The UVA score is validated for predicting mortality in hospitalized adults in sSA and scores can be categorized as low risk (score < 2), medium risk (score 2–4), and high risk (score > 4) (25). We were able to determine UVA scores only for participants in Cohort 2 because the data needed to calculate this score were not collected in Cohort 1.

Laboratory methods

All research samples were processed in the Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute (KCRI) Biotechnology Laboratory. During both study periods, the laboratory was externally audited on an annual basis and participated in international external quality assurance (EQA) programs. EQA programs included those of the College of American Pathologists that conducts regular blood parasite surveys assessing the quality of parasitologic diagnosis of malaria. All laboratory investigations were conducted according to Good Clinical Laboratory Practice standards.

Samples for research laboratory testing were collected in addition to those ordered by the hospital clinicians prior to study enrollment. Our results were not available to clinicians at the time of admission, but all enrollments were within 24 hours of admission and research laboratory results were available to clinicians within 24 hours of sample collection. Malaria parasites detected by smear microscopy were treated as a critical result and thus reported immediately to treating clinicians. While our study results were made available to clinicians, initial malaria diagnostic and treatment decisions were largely informed by a combination of local practice patterns, treatment guidelines, and provider-initiated testing performed as part of usual care. Malaria blood smear microscopy and mRDT were available at both hospitals during our two study periods. However, we did not document orders or results of malaria diagnostic testing done outside of our research laboratory.

Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears were examined for malaria parasites by oil immersion microscopy following a standard operating procedure that required two competent microscopists to review each slide. For Cohort 2, malaria infection was also assessed in whole blood by SD-Bioline Malaria Ag P.f/Pan (Standard Diagnostics Inc., Kyonggi-do, South Korea) mRDT for the detection of the histidine-rich protein II (HRP2) antigen of Plasmodium falciparum and the common Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH).

In Cohort 1, HIV infection status was self-reported. In Cohort 2, HIV testing was performed on whole blood using SD Bioline HIV-1/HIV-2 3.0 test (Standard Diagnostics Inc, Kyonggi-do, South Korea) for screening followed by the Unigold Rapid HIV test (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) for confirmation. All HIV testing was accompanied by pre- and post-test counseling.

Definitions

Positive-smear microscopy was defined as the presence of malaria parasites on blood films and a negative smear-microscopy was defined as the absence of malaria parasites on blood films. Malaria over-diagnosis was defined as a diagnosis of malaria at the time of hospital admission in a participant for whom no parasites were detected on malaria smear-microscopy by research laboratory staff. Similarly, malaria over-treatment was defined as administration of an antimalarial during hospital admission in a participant for whom no parasites were detected on malaria smear-microscopy by research laboratory staff. All diagnoses and treatment decisions were made by treating clinicians at KCMC or MRRH. At KCMC, all treating clinicians were medical doctors while at MRRH treating clinicians included clinical officers, medical officers, and medical doctors. We performed mRDTs in Cohort 2 along with smear-microscopy. Participants with a positive mRDT in the setting of a negative smear-microscopy were categorized as recent malaria since persistent post-treatment antigenemia is the most commonly reported cause for a positive mRDT in the setting of a negative smear-microscopy (26,27).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Only patients with a malaria blood smear-microscopy result were included in the analysis. Continuous variables were expressed using medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies. Differences between the two study periods were assessed using Pearson’s Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Log-binomial regression models were used to determine the risk of mortality for participants categorized as malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment. We first constructed bivariable models for all independent variables and then created separate multivariable models for malaria over-diagnosis (model 1) and malaria over-treatment (model 2) adjusted for age, sex, and UVA score. Separate models were constructed for malaria over-diagnosis and malaria over-treatment because the two variables are highly related. Regression models were not constructed for Cohort 1 because UVA scores were not calculated for this cohort. Furthermore, we restricted the regression analyses to age ≥ 13 years since the UVA score is not validated in children. All P-values are two sided and a P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

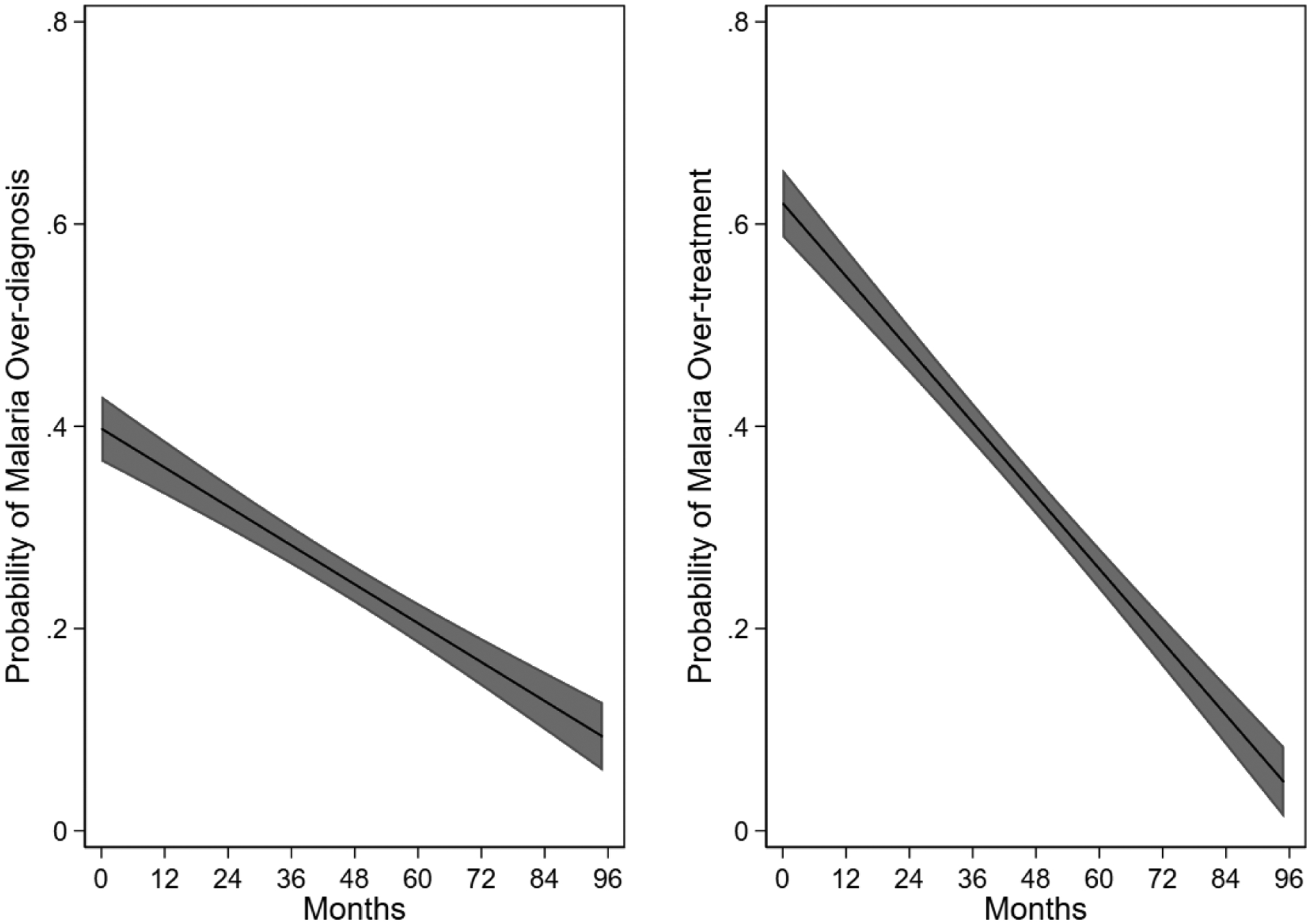

To understand temporal trends in malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment, predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals were computed. First, we constructed log-binomial regression models with the dependent variables as malaria over-diagnosis and malaria over-treatment and the explanatory variable as time in months, age in years, and sex. Time zero was assigned to the first participant enrolled in cohort 1. We then plotted the predicted probabilities of malaria over-diagnosis or over-treatment in one month increments while holding age in years and sex at their means.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics and malaria testing

We analyzed data from 2,098 participants with 984 (46.9%) enrolled in Cohort 1 and 1,114 (53.1%) enrolled in Cohort 2 (Figure 1). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants in Cohort 1 had a median (IQR) age of 30 (9–42) years compared with 23 (2–45) years in Cohort 2 (P <0.001). In Cohort 1, 540 (55.0%) participants were female vs. 507 (45.5%) in Cohort 2 (P <0.001). There were 23 (2.3%) participants with a positive smear-microscopy in Cohort 1 and 42 (3.8%) in Cohort 2 (P=0.059). In Cohort 2, 80 (7.2%) participants had a positive RDT with 42 (52.5%) categorized as recent malaria based on simulatenously negative smear-microscopy.

Figure 1.

Screening and enrollment flow diagram for hospitalized patients enrolled in two febrile surveillance studies, Cohort 1 (2011–2014) and Cohort 2 (2016–2019), northern Tanzania

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of hospitalized patients enrolled in two febrile surveillance studies, Cohort 1 (2011–2014) and Cohort 2 (2016–2019), northern Tanzania

| Variables | Cohort 1 (n=984) |

Cohort 2 (n=1,114) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 30 (9–42) | 23 (2–45) | <0.001 |

| Age, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| < 5 years | 202 (20.5) | 391 (35.1) | |

| 5–14 years | 70 (7.1) | 97 (8.7) | |

| ≥15 year | 712 (72.4) | 626 (56.2) | |

| Female, n (%) | 540 (55.0) | 507 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization history and findings | |||

| Prior antibacterial, n (%) | 404 (41.9) | 676 (65.1) | <0.001 |

| Prior antimalarial, n (%) | 340 (35.0) | 149 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Prior malaria diagnostic test, n (%) | a | 1,036 (93.0) | |

| Positive malaria diagnostic test prior to hospitalization, n (%) | a | 138 (13.3) | |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| HIV infection, n (%) | 181 (34.5)b | 231 (20.7) | |

| Positive mRDT, n (%) | a | 80 (7.2) | |

| Positive malaria smear-microscopy, n (%) | 23 (2.3) | 42 (3.8) | 0.059 |

| Smear-negative diagnostic and treatment decision | |||

| Malaria over-diagnosisc, n (%) | 335 (35.0) | 190 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Malaria over-treatmentc, n (%) | 528 (55.1) | 196 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| Malaria smear-negative and administered an antibacterial during hospitalizationc, n (%) | 851 (88.6) | 1,049 (98.1) | <0.001 |

| Vital outcome | |||

| Mortality (entire cohort), n (%) | 30 (3.1) | 60 (5.4) | 0.007 |

| Mortality (malaria over-diagnosis)d, n (%) | 6 (1.8) | 2 (1.1) | 0.504 |

| Mortality (malaria over-treatment)e, n (%) | 7 (1.3) | 17 (8.7) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; mRDT, malaria rapid diagnostic test

Data not collected

Missing data from 460 participants as HIV-serostatus was based on self-report

Denominator includes only participants who were negative by smear-microscopy

Denominator includes only participants who met criteria for malaria over-diagnosis

Denominator includes only participants who met criteria for malaria over-treatment

Clinical history prior to hospitalization

Of participants, 340 (35.0%) in Cohort 1 reported antimalarial use prior to hospitalization vs. 149 (14.4%) in Cohort 2 (P < 0.001). Antibacterial use prior to hospitalization was reported by 404 (41.9%) participants in Cohort 1 and 676 (65.1%) in Cohort 2 (P <0.001). For Cohort 2, 1,036 (93.0%) reported receipt of a malaria diagnostic test prior to hospitalization. Of these participants, 1,029 (99.3%) recalled their test result with 138 (13.4%) reporting a positive test result and 891 (86.6%) reporting a negative test result. Of the 138 participants who reported a positive malaria diagnostic test, 105 (76.1%) received an antimalarial prior to hospitalization, and 37 (26.8%) and 70 (51.1%) were positive by smear-microscopy and mRDT at the time of study enrollment, respectively. Of the 891 participants who reported a negative malaria diagnostic test, 44 (5.0%) received an antimalarial prior to hospitalization, and 4 (0.5%) and 7 (0.8%) were positive by smear-microscopy and mRDT, at the time of study enrollment respectively.

Diagnoses and treatments during hospital admission

We observed a decline over time in malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment (Figure 2). In cohort 1, 335 (34.2%) participants met study criteria for malaria over-diagnosis compared to 190 (17.1%) in Cohort 2 (P <0.001). Malaria over-treatment occurred in 528 (55.1%) participants in Cohort 1 and 196 (18.3%) in Cohort 2 (P < 0.001). In Cohort 1, 851 (88.6%) smear-negative participants were administered an antibacterial during hospital admission and 1,049 (98.1%) in Cohort 2 (P < 0.001). Of the 65 participants in both cohorts with a positive smear-microscopy, 6 (9.2%) did not receive an antimalarial during hospital admission; two of these had reported receiving an antimalarial prior to hospitalization. Among 42 participants with recent malaria in Cohort 2, 39 (92.9%) received an antimalarial and 35 (83.3%) received an antibacterial. In Cohort 2, the distribution of UVA scores at admission were 572 (54.3%) low risk (score 0–1), 357 (33.9%) medium risk (score 2–4), and 124 (11.8%) high risk (score > 4). Antibacterial use during admission for low, medium, and high risk groups as stratified by the UVA score was 550 (96.5%), 354 (99.4%), and 124 (100%), respectively.

Figure 2.

Adjusted prediction of malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment among hospitalized patients in two febrile surveillance studies from September 2011 through May 2019. The central line displays the mean; gray areas represent 95% confidence interval.

Mortality

There were 30 (3.1%) deaths in Cohort 1 and 60 (5.4%) in Cohort 2 (P = 0.007). There were no deaths among participants who had a positive smear-microscopy. Furthermore, there were no deaths among participants with a positive mRDT in Cohort 2, including those categorized as recent malaria. Of participants who met study criteria for malaria over-diagnosis, there were 6 (1.8%) deaths in Cohort 1 and 2 (1.1%) in Cohort 2 (P = 0.504). Of participants who met study criteria for malaria over-treatment, there were 7 (1.3%) deaths in Cohort 1 compared to 17 (8.7%) in Cohort 2 (P < 0.001). Of these 24 deaths that met study criteria for malaria over-treatment, all received an antibacterial during hospitalization.

Predictors of mortality

Regression models were constructed to evaluate the predictors of mortality among adolescent and adults in Cohort 2. These results are shown in Table 2. In the unadjusted analysis, variables significantly associated (relative risk [RR], 95% Confidence Interval) with mortality were UVA score 2–4 (6.39, 3.13–13.01), UVA score > 4 (12.56, 6.44–24.47), and malaria over-diagnosis (0.14, 0.03–0.55). In model 1 (malaria over-diagnosis), significant predictors of mortality were UVA score 2–4 (5.78, 2.83–11.83) and UVA score > 4 (10.93, 5.57–21.42). In model 2 (malaria over-treatment), significant predictors of mortality were UVA score 2–4 (6.27, 3.06–12.83) and UVA score > 4 (12.57, 6.44–24.57).

Table 2.

Predictors of mortality among hospitalized adolescent and adult patients enrolled in a febrile surveillance study, Cohort 2 (2016–2019), northern Tanzania

| Variables | Unadjusted RR | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | |

| Age in years | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| Female | 1.10 (0.67–1.79) | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | 1.35 (0.84–2.17) |

| UVA score | |||

| Low | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Medium | 6.39 (3.13–13.01) | 5.78 (2.83–11.83) | 6.27 (3.06–12.83) |

| High | 12.56 (6.44–24.47) | 10.93 (5.57–21.42) | 12.57 (6.43–24.57) |

| Malaria over-diagnosis | 0.14 (0.03–0.55) | 0.27 (0.07–1.08) | - |

| Malaria over-treatment | 1.26 (0.74–2.14) | - | 1.35 (0.82–2.23) |

Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio; CI, confidence interval; aRR, adjusted risk ratio; UVA, Universal Vital Assessment

Model 1: Malaria over-diagnosis model; Model 2: Malaria over-treatment model

DISCUSSION

We described trends in fever case management in northern Tanzania, demonstrating a significant decrease in malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment in the 2016–2019 cohort compared to an earlier cohort from 2011–2014 at the same enrollment sites. Our data demonstrates substantial progress in fever case management in our setting that may be the result of a concerted shift from a presumptive to test-directed treatment strategy for malaria. While test availability and turnaround times and illness severity may warrant empiric malaria treatment in some circumstances, we found that clinician diagnostic and treatment decisions in our setting still remain incongruent with the proportion of febrile patients with malaria parasitemia.

Our study was conducted in a low malaria transmission intensity setting in northern Tanzania (22,23). Consistent with the known transmission intensity of malaria in our setting, the prevalence of malaria parasitemia across both cohorts was <5%. Encouragingly, we observed substantial improvements in malaria diagnostic and treatment behaviors in the context of fever case management between our two cohorts. Yet, our data suggest that deviations from best practices persist. Notably, the proportions of participants in Cohort 2 who met criteria for malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment were nearly five-fold higher than the proportion of participants with smear-proven malaria as determined by study laboratory results. Two important considerations warrant discussion in interpreting these findings. First, treatment guidelines recommend antibacterials together with antimalarials for severely ill patients such as those presenting with shock, respiratory distress, or altered consciousness while awaiting the results of diagnostic studies (2). Thus, empiric antimalarial use may be appropriate in the initial clinical management of some severely ill patients. Second, our data did not allow us to assess factors that contribute to ongoing malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment in our setting. Prior studies suggest that possible explanations may include clinician non-adherence to a negative malaria diagnostic test result or facility-level deficiencies in the availability of malaria diagnostic testing that may result in empiric treatment of malaria (28).

The primary aim of our study was to understand trends in fever case management during hospitalization. However, we collected self-reported data from participants regarding management of their illness prior to hospitalization and these data, while possibly limited by self-reporting bias, provide insights into fever case management in the community. Similar to our data collected during hospitalization, we observed a substantial decline in self-reported pre-hospital antimalarial use between our two cohorts. Furthermore, the majority of participants in Cohort 2 reported a malaria diagnostic test prior to hospitalization and self-reported use of an antimalarial was low in the context of a negative malaria diagnostic test. Overall, these findings are encouraging but are balanced by the reality that antimalarial use, while improved, remains discordant with the proportion of participants found to have Plasmodium parasitemia. Our data did not permit examination of the factors that influence antimalarial prescribing practices in the community. However, one finding that warrants further discussion is the proportion of participants in Cohort 2 who reported a positive malaria diagnostic test prior to hospitalization. We found that 13.3% of participants reported a positive malaria diagnostic test; yet, a large proportion of these participants were negative by smear-microscopy and mRDT at the time of study enrollment. While this finding could be the result of inaccurate participant recall or social desirability bias, further investigation into the quality of malaria diagnostic testing in the community may be warranted.

We observed an increase in antibacterial use between our two cohorts in both the community and hospital setting. Our results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated higher antibacterial prescribing alongside desired reductions in antimalarial use (12,16–18,29). We did not evaluate the extent to which antibacterials were warranted in either cohort. Certainly, treatment guidelines recommend empiric antibacterials for patients with severe febrile illness (2,30). Thus, the high antibacterial use observed during hospitalization among participants classified as medium and high risk by UVA score in Cohort 2 may be appropriate. However, emerging evidence suggests that present trends towards increased antibacterial use are partially driven by untargeted use such as antibacterial prescribing for clinical syndromes caused by viral infections (16,18). Without intervention, such trends will contribute to increasing antimicriobial resistance and thus warrant further attention.

All deaths in both cohorts occurred among participants who were smear-negative. This finding highlights the success of modern malaria control but also illustrates the challenges clinicians face when fever is not caused by malaria (31–33). Our data from Cohort 2 enabled us to explore the extent to which malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment contributes to the higher mortality observed among smear-negative participants in our cohort. In our adjusted regression models, we found no association between malaria over-diagnosis or over-treatment with mortality. One possible explanation for these findings is the widespread use of antibacterials among smear-negative participants in Cohort 2. In contrast, nearly two-thirds of smear-negative participants in one prospective study of severly ill hospitalized patients in Tanzania did not receive an antibacterial in the setting of abundant malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment.(3) Further studies examining the associations of malaria over-diagnosis and over-treatment with outcomes of febrile patients with a negative malaria diagnostic test are needed.

We anticipated that non-prescription of an antimalarial to study participants with positive smear-microscopy would be minimal because our results were made available to treating clinicians within 24 hours of sample collection. Furthermore, a positive smear-microscopy result was deemed a critical result and thus immediately reported to the treating clinicians. Unexpectedly, we observed that nearly 10% of smear positive participants did not receive an antimalarial during hospitalization. Because medication history during hospitalization was based on chart abstraction, we cannot exclude the possibility that some participants were administered antimalarials that were not documented in the medical chart. However, several studies now suggest that non-prescription of antimalarials to patients with a positive malaria test is not uncommon (12,34). Future research on fever management in our setting should investigate both malaria under-treatment as well as malaria over-treatment.

Our present analysis was subject to several limitations. First, our study was conducted in a low malaria transmission area in northern Tanzania. While it is now realized that many settings in sSA are characterized by low malaria transmission intensity, our results may not be generalizable to other regions in Tanzania or other countries where malaria transmission is higher (35). Second, our hospitals may not be typical of other hospitals locally or nationally. Both are referral hospitals with resources that may not be available elsewhere. Third, data collected prior to admission relied on self-report. Self-report is subject to biases of recall and social-desirability (36). In particular, providing socially desirable answers regarding malaria testing and antimalarial use prior to admission could be influenced by national campaigns that encouraged patients with fevers to seek testing before treatment (23). Fourth, our study was observational in nature and we did not attempt to alter the diagnostic and treatment decisions of clinicians. However, study laboratory and microbiologic results were made available to clinicians. While these results likely did not impact our outcomes of interest, clinician diagnostic and treatment decision in the context of our fever surveillance studies may differ from routine operational conditions.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates a major shift in the diagnosis and management of febrile illnesses in a low malaria transmission setting in northern Tanzania. Despite encouraging progress, malaria remains over-attributed as an etiology of fever and reductions in antimalarial use may be offset by an increase in antibacterial prescribing. In addition, our data suggest a need to define the scale of undertreatment of patients who test positive for malaria. Taken together, our results highlight the need for continued monitoring of fever case management across different malaria epidemiologic settings in sSA and reveal areas to focus attention. Finally, it is important to recognize that clinicians across many settings in sSA are faced with fever case management in the setting of a negative malaria diagnostic test. To better manage fever cases, there is a need for improved epidemiologic surveillance and point-of-care diagnostics to inform non-malaria fever management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those involved in recruitment, laboratory work, data management and study administration, including: Godfrey S. Mushi, Flora W. Mboya, Lilian E. Ngowi, Winfrida H. Shirima, Michael E. Butoyi, Anna H. Mwalla, Miriam L. Barabara, Ephrasia Mariki, Edna Ngowi, Olterere Salimu, Rither Mhela, Jamal Bashiri, Christopher Swai, Jerome Mlangi, Tumsifu G. Tarimo, Yusuf S. Msuya, Leila J. Sawe, Aaron E. Tesha, Luig J. Mbuya, Edward M. Singo, Stephen Sikumbili, Erica Chuwa, Daniel Mauya, Isaac A. Afwamba, Thomas M. Walongo, Remigi P. Swai, Augustine M. Musyoka, Rose Oisso, Gershom Mmbwambo, Philoteus A. Sakasaka, O. Michael Omondi, Enoch J. Kessy, Alphonse S. Mushi, Robert S. Chuwa, Charles Muiruri, Cynthia A. Asiyo, Frank M. Kimaro, and Francis P. Karia. In addition, we would like to thank the study participants as well as the clinical staff and administration at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre and Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital for their support during this study.

This research was supported by the joint US National Institutes of Health (NIH:www.nih.gov)-an Science Foundation (NSF:www.nsf.gov) Ecology of Infectious Disease program (R01TW009237) and the Research Councils UK, Department for International Development (UK) and UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC:www.bbsrc.ac.uk) (grant numbers BB/J010367/1, BB/L018926, BB/L017679, BB/L018845), in part by an US NIH awards (U01 AI062563 and R01 AI121378), and in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded Typhoid Fever Surveillance in sub-Saharan Africa Program (TSAP) grant (OPPGH5231). DBM received support from the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) 5T32AI007392 and US NIH Fogarty International Center grant D43TW009337. MJM received support from University of Otago scholarships: the Frances G. Cotter Scholarship and the McGibbon Travel Fellowship. MPR received support from National Institutes of Health Research Training Grants (R25 TW009337) funded by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute of Mental Health and from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23 AI116869 and AI121378). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. IMAI district clinician manual: hospital care for adolescents and adults – guidelines for the management of illnesses with limited resources. 2011.

- 3.Reyburn H, Mbatia R, Drakeley C, Carneiro I, Mwakasungula E, Mwerinde O, et al. Overdiagnosis of malaria in patients with severe febrile illness in Tanzania: a prospective study. BMJ. 2004. November 20;329(7476):1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amexo M, Tolhurst R, Barnish G, Bates I. Malaria misdiagnosis: effects on the poor and vulnerable. Lancet. 2004. November 20;364(9448):1896–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makani J, Matuja W, Liyombo E, Snow RW, Marsh K, Warrell DA. Admission diagnosis of cerebral malaria in adults in an endemic area of Tanzania: implications and clinical description. QJM. 2003. May;96(5):355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks F, von Kalckreuth V, Kobbe R, Adjei S, Adjei O, Horstmann RD, et al. Parasitological rebound effect and emergence of pyrimethamine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum after single-dose sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. J Infect Dis. 2005. December 1;192(11):1962–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nsanzabana C, Hastings IM, Marfurt J, Müller I, Baea K, Rare L, et al. Quantifying the evolution and impact of antimalarial drug resistance: drug use, spread of resistance, and drug failure over a 12-year period in Papua New Guinea. J Infect Dis. 2010. February 1;201(3):435–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organisation (2012) T3: Test. Treat. Track. Scaling up diagnostic testing, treatment and surveillance for malaria. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odaga J, Sinclair D, Lokong JA, Donegan S, Hopkins H, Garner P. Rapid diagnostic tests versus clinical diagnosis for managing people with fever in malaria endemic settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. April 17;2014(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruxvoort KJ, Leurent B, Chandler CIR, Ansah EK, Baiden F, Björkman A, et al. The Impact of Introducing Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests on Fever Case Management: A Synthesis of Ten Studies from the ACT Consortium. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017. October 11;97(4):1170–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandler CIR, Mangham L, Njei AN, Achonduh O, Mbacham WF, Wiseman V. ‘As a clinician, you are not managing lab results, you are managing the patient’: How the enactment of malaria at health facilities in Cameroon compares with new WHO guidelines for the use of malaria tests. Social Science & Medicine. 2012. May 1;74(10):1528–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansah EK, Reynolds J, Akanpigbiam S, Whitty CJ, Chandler CI. “Even if the test result is negative, they should be able to tell us what is wrong with us”: a qualitative study of patient expectations of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria. Malar J. 2013. July 22;12:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manderson L. Prescribing, care and resistance: antibiotic use in urban South Africa. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2020. September 1;7(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndhlovu M, Nkhama E, Miller JM, Hamer DH. Antibiotic prescribing practices for patients with fever in the transition from presumptive treatment of malaria to “confirm and treat” in Zambia: a cross-sectional study. Trop Med Int Health. 2015. December;20(12):1696–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mubi M, Kakoko D, Ngasala B, Premji Z, Peterson S, Björkman A, et al. Malaria diagnosis and treatment practices following introduction of rapid diagnostic tests in Kibaha District, Coast Region, Tanzania. Malar J. 2013. August 26;12(1):293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins H, Bruxvoort KJ, Cairns ME, Chandler CIR, Leurent B, Ansah EK, et al. Impact of introduction of rapid diagnostic tests for malaria on antibiotic prescribing: analysis of observational and randomised studies in public and private healthcare settings. BMJ. 2017. March 29;356:j1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Opoka RO, Xia Z, Bangirana P, John CC. Inpatient mortality in children with clinically diagnosed malaria as compared with microscopically confirmed malaria. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008. April;27(4):319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moon AM, Biggs HM, Rubach MP, Crump JA, Maro VP, Saganda W, et al. Evaluation of In-Hospital Management for Febrile Illness in Northern Tanzania before and after 2010 World Health Organization Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. PLOS ONE. 2014. February 24;9(2):e89814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USAID. President’s Malaria Initiative Tanzania. Malaria Operational Plan FY; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS), Zanzibar AIDS Commission (ZAC), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF International 2013. Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011–12. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: TACAIDS, ZAC, NBS, OCGS, and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), and ICF. 2017. Tanzania Malaria Indicator Survey 2017. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, OCGS, and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, Tanzania and Ministry of Health, Zanzibar. Tanzania. Tanzania HIV Impact Survey (THIS) 2016–2017: Final Report. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore CC, Hazard R, Saulters KJ, Ainsworth J, Adakun SA, Amir A, et al. Derivation and validation of a universal vital assessment (UVA) score: a tool for predicting mortality in adult hospitalised patients in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mbabazi P, Hopkins H, Osilo E, Kalungu M, Byakika-Kibwika P, Kamya MR. Accuracy of Two Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTS) for Initial Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring in a High Transmission Setting in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015. March 4;92(3):530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalrymple U, Arambepola R, Gething PW, Cameron E. How long do rapid diagnostic tests remain positive after anti-malarial treatment? Malaria Journal. 2018. June 8;17(1):228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandler CIR, Jones C, Boniface G, Juma K, Reyburn H, Whitty CJM. Guidelines and mindlines: why do clinical staff over-diagnose malaria in Tanzania? A qualitative study. Malar J. 2008. April 2;7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Acremont V, Kahama-Maro J, Swai N, Mtasiwa D, Genton B, Lengeler C. Reduction of anti-malarial consumption after rapid diagnostic tests implementation in Dar es Salaam: a before-after and cluster randomized controlled study. Malar J. 2011. April 29;10(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crump JA, Gove S, Parry CM. Management of adolescents and adults with febrile illness in resource limited areas. BMJ [Internet]. 2011. August 8 [cited 2021 Apr 1];343. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3164889/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D. When fever is not malaria. The Lancet Global Health. 2013. July 1;1(1):e11–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoler J, Awandare GA. Febrile illness diagnostics and the malaria-industrial complex: a socio-environmental perspective. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016. November 17;16(1):683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roddy P, Dalrymple U, Jensen TO, Dittrich S, Rao VB, Pfeffer DA, et al. Quantifying the incidence of severe-febrile-illness hospital admissions in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2019. July 25;14(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Boyle S, Bruxvoort KJ, Ansah EK, Burchett HED, Chandler CIR, Clarke SE, et al. Patients with positive malaria tests not given artemisinin-based combination therapies: a research synthesis describing under-prescription of antimalarial medicines in Africa. BMC Med. 2020. January 30;18(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015. October;526(7572):207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Althubaiti A Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016. May 4;9:211–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]