Abstract

Much evidence suggests a role for human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) in establishing the infant microbiota in the large intestine, but the response of particular bacteria to individual HMOs is not well known. Here twelve bacterial strains belonging to the genera Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Limosilactobacillus, Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were isolated from infant faeces and their growth was analyzed in the presence of the major HMOs, 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL), 3-fucosyllactose (3FL), 2′,3-difucosyllactose (DFL), lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neo-tetraose (LNnT), present in human milk. Only the isolated Bifidobacterium strains demonstrated the capability to utilize these HMOs as carbon sources. Bifidobacterium infantis Y538 efficiently consumed all tested HMOs. Contrarily, Bifidobacterium dentium strains Y510 and Y521 just metabolized LNT and LNnT. Both tetra-saccharides are hydrolyzed into galactose and lacto-N-triose (LNTII) by B. dentium. Interestingly, this species consumed only the galactose moiety during growth on LNT or LNnT, and excreted the LNTII moiety. Two β-galactosidases were characterized from B. dentium Y510, Bdg42A showed the highest activity towards LNT, hydrolyzing it into galactose and LNTII, and Bdg2A towards lactose, degrading efficiently also 6′-galactopyranosyl-N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetyl-lactosamine and LNnT. The work presented here supports the hypothesis that HMOs are mainly metabolized by Bifidobacterium species in the infant gut.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are non-conjugated and structurally diverse carbohydrates present in human milk, with more than 100 structures already elucidated1. They constitute the third solid component most abundant in human milk after lactose and lipids. Concentration ranges from 10 to 20 g/l in mature milk and over 20 g/l in colostrum2, although relative proportions and total amounts of HMOs vary depending on the genetic background (Secretor and Lewis-based blood group) of the mother and the lactating stage3,4. HMOs consist of combinations of five monosaccharides: d-glucose (Glc), d-galactose (Gal), N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), l-fucose (Fuc) and sialic acid. Within the group of neutral HMOs, 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL; Fucα1-2Galβ1-4Glc), 3-fucosyllactose (3FL; Galβ1–4(Fucα1–3)Glc), 2′,3-difucosyllactose (DFL or LDFT; Fucα1-2Galβ1–4(Fucα1–3)Glc), lacto-N-tetraose (LNT; Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) and lacto-N-neo-tetraose (LNnT; Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) are the major HMOs detected in milk. LNT and LNnT constitute the core type-1 and type-2 structures, respectively, which can be further elongated by the addition of Gal, GlcNAc, Fuc or sialic acid.

HMOs are not metabolized in the gut5 and therefore they do not provide any nutritive value for the infant. Much evidence suggests that they have beneficial functions in infants, including an effect as immuno-modulators6, a decrease in the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants7 and protection against infectious diseases through anti-adhesive antimicrobial properties8. Some evidences also support an important function for HMOs in building the composition of the infant gut microbiota9,10. Bacteria have adapted to the infant gastrointestinal tract by developing specific glycosyl hydrolases to break down HMOs11. Among bifidobacterial species, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis, Bifidobacterium bifidum and Bifidobacterium breve readily utilize HMOs10,12–15. They have been shown to possess a great battery of glycosyl hydrolases involved in the catabolism of specific HMOs10,15–18. Other Bifidobacterium species such as Bifidobacterium dentium have also been found in infant faeces19–21, and it has been described that members of this species are unable to grow on HMOs21,22. Our group and others have demonstrated that the species of Lacticaseibacillus casei (previously known as Lactobacillus casei) and Lactobacillus acidophillus are also consumers of HMOs and HMO-derived glycans23–25, and the catabolic enzymes involved in their metabolism have been characterized26–29. For Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus thermophillus species, a slight growth was shown in fucosylated HMOs30.

Besides HMOs, human milk provides microorganisms that readily colonize the infant gastrointestinal tract31. In the present study, bacteria were isolated from breastfed infant faeces and their capability to utilize major individual HMOs (2′FL, 3FL, DFL, LNT and LNnT), HMO-derived glycans and monosaccharides for growth was determined. Among the isolated species, the Bifidobacterium infantis strain Y538 was found to be the most efficient at consuming all tested HMOs, and the Bifidobacterium dentium strains Y510 and Y521 were able to ferment the galactose moiety of LNT and LNnT. Furthermore, two β-galactosidases with activity in these tetra-saccharides were characterized from B. dentium.

Results

Isolation and identification of bacteria from breast-fed infant feces

A fecal sample mix of four exclusively breastfed infants was plated in different agar media as described in “Methods” in order to isolate bacteria. Isolates were randomly selected, subjected to RAPD-PCR analysis and at least one representative of each band pattern was kept for subsequently species identification. Based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the isolates were identified as Bifidobacterium dentium (Y510, Y521, Y522, Y525, Y546), Bifidobacterium longum (Y538), Enterococcus faecalis (Y513, Y515-516, Y530-534, Y536, Y547-548, Y550), Limosilactobacillus fermentum (ex-Lactobacillus fermentum) (Y500, Y502, Y504, Y506-509, Y512, Y523-524, Y527-528, Y535, Y537), Lactobacillus gasseri (Y511), Lacticaseibacillus paracasei (ex-Lactobacillus paracasei) (Y526), Limosilactobacillus reuteri (ex-Lactobacillus reuteri) (Y501, Y503, Y505), Staphylococcus epidermidis (Y520), Staphylococcus hominis (Y549) and Streptococcus pasteurianus (Y529). Previous studies have shown that RAPD-PCR analysis is an appropriate molecular tool to differentiate lactic acid bacteria at the strain level32,33. The RAPD-PCR profiles using the MVC primer (Supplementary Figure S1) allowed differentiating between B. dentium Y510 and the rest of B. dentium isolates. Among the E. faecalis isolates, all except one (Y533), showed similar band patterns. All L. fermentum and L. reuteri isolates showed a unique band pattern, respectively. One isolate representative of each band pattern was utilized for further analysis. These isolates were confirmed at the species level by sequencing the almost entire region of 16S rRNA gene. In addition, B. dentium isolates Y510 and Y521 were differentiated at the strain level with two more RAPD primers, PER1 and CORR1 (Supplementary Figure S2).

The two subspecies of B. longum that often colonize the infant intestine are B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. longum. Based on the restriction patterns of the partial 16S rRNA gene amplicon digested with Sau3AI34, the B. longum Y538 strain was consistent with B. longum subsp. infantis (data not shown).

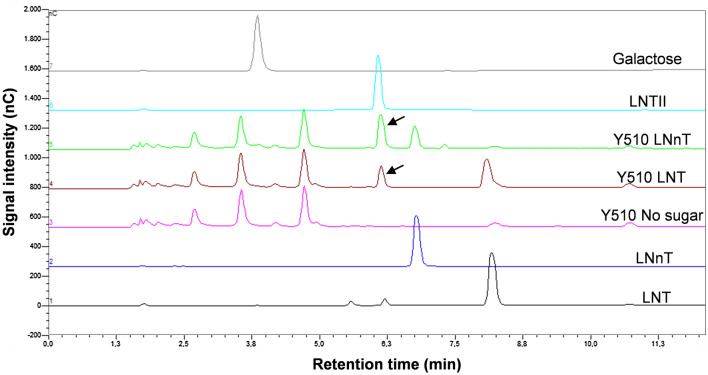

Growth of bacteria isolated strains on individual HMOs

In order to determine the ability of the newly obtained bacterial strains to utilize HMOs as a carbon source, their ability to grow on MRS basal medium supplement with 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL), 3-fucosyllactose (3FL), 2′,3-difucosyllactose (DFL), lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) or lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT) was analyzed. From the twelve bacteria strains assayed, only B. dentium and B. infantis strains were able to grow in the presence of HMOs (Table 1). B. dentium Y510 and Y521 strains utilized LNT and LNnT, although with a low efficiency as seen by the modest reduction in pH in the culture medium (Fig. 1). B. infantis Y538 grew in the presence of all five oligosaccharides (Fig. 1). The strains E. faecalis (Y513, Y533), L. fermentum (Y500), L. gasseri (Y511), L. paracasei (Y526), L. reuteri (Y501), S. epidermidis (Y520), S. hominis (Y549) and S. pasteurianus (Y529) did not exhibit any significant growth in the presence of the tested HMOs compared to the culture controls without carbohydrate source (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S3). The growth of the isolates in the presence of lactose or GlcNAc as positive controls is also shown. All bacterial strains, except E. faecalis Y533 and S. hominis Y549, were able to grow in the presence of lactose, and these two strains utilized GlcNAc. The fermentation of l-fucose was also assayed and the B. infantis and S. pasteurianus tested strains were able to catabolize this monosaccharide (Table 1).

Table 1.

Utilization of monosaccharides and human milk oligosaccharides by infant-gut associated bacterial strainsa.

| Strains | Lac | Fuc | Gal | GlcNAc | 2′FL | 3FL | DFL | LNT | LNnT | LNTII | LNB | LacNAc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. dentium Y510 | ++ | − | ++ | + | − | − | − | ± | + | − | − | + |

| B. dentium Y521 | ++ | − | ++ | ± | − | − | − | ± | ± | − | − | + |

| B. infantis Y538 | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | +++ |

| E. faecalis Y513 | +++ | − | nd | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| E. faecalis Y533 | − | − | nd | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| L. fermentum Y500 | +++ | − | nd | − | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| L. gasseri Y511 | ++ | − | nd | + | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| L. paracasei Y526 | +++ | − | nd | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| L. reuteri Y501 | +++ | − | nd | − | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| S. epidermidis Y520 | +++ | − | nd | − | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| S. hominis Y549 | − | − | nd | +++ | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

| S. pasteurianus Y529 | ++ | + | nd | ++ | − | − | − | − | − | nd | nd | nd |

aLevel of bacterial growth was classified as follows: Bifidobacterium strains, OD595 < 0.12 (−), OD595 0.12–0.2 (±), OD595 0.2–0.3 (+), OD595 0.3–0.5 (++) and OD595 > 0.5 (+++); E. faecalis Y513, OD595 < 1.0 (−), OD595 1.0–1.2 (++) and OD595 > 1.2 (+++); E. faecalis Y533, OD595 < 0.5 (−) and OD595 > 0.5 (+++); L. fermentum, OD595 < 0.6 (−) and OD595 > 0.6 (+++); L. gasseri and S. pasteurianus, OD595 < 0.2 (−), OD595 0.2–0.3 (+) and OD595 > 0.3 (++); L. paracasei and L. reuteri, OD595 < 0.35 (−), OD595 0.35–0.45 (++) and OD595 > 0.45 (+++); S. epidermidis, OD595 < 5.0 (−) and OD595 > 5.0 (+++); S. hominis, OD595 < 3.0 (−) and OD595 > 3.0 (+++). OD595 values correspond to 48 h cultures (Bifidobacterium strains) and maximum OD values for the rest of the strains.

nd not determined.

Lac lactose, Fuc L-fucose, Gal galactose, GlcNAc N-acetylglucosamine, 2′FL 2′-fucosyllactose, 3FL 3-fucosyllactose, DFL difucosyllactose, LNT lacto-N-tetraose, LNnT lacto-N-neotetraose, LNTII lacto-N-triose, LNB lacto-N-biose, LacNAc N-acetyllactosamine.

Figure 1.

Carbohydrate utilization profiles of Bifidobacterium dentium Y510 (a), B. dentium Y521 (b) and Bifidobacterium infantis Y538 (c). MRS basal medium supplemented with 2 mM of carbohydrates was used. pH decrease values of culture supernatants are shown. Data presented are mean values based on at least two replicates. Errors bars indicated standard deviations. Lac lactose, Fuc l-fucose, Gal galactose, GlcNAc N-acetylglucosamine, 2′FL 2′-fucosyllactose, 3FL 3-fucosyllactose, DFL difucosyllactose, LNT lacto-N-tetraose, LNnT lacto-N-neotetraose, LNTII lacto-N-triose, LNB lacto-N-biose, LacNAc N-acetyllactosamine.

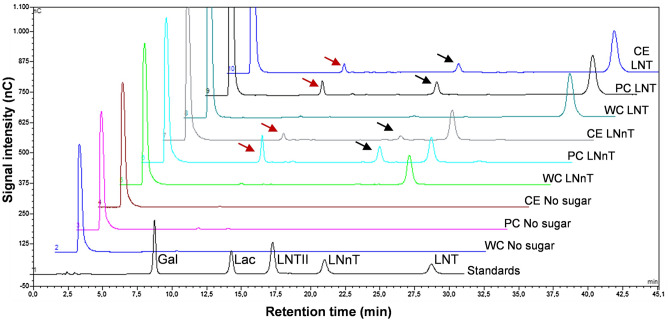

To confirm that the HMOs were or not fermented by the isolated strains, the supernatants of the cultures were analyzed for sugar content. No measurable decrease in HMOs concentration was observed for the isolates, with the exception of the Bifidobacterium species. B. dentium strains partially degraded LNT and LNnT (Table 2). Unexpectedly, lacto-N-triose (LNTII) was detected in the culture supernatant of both strains when grown in either tetra-saccharide. In Fig. 2 are presented the carbohydrate analysis of the culture supernatants from Y510 strain. The amount of LNTII present in the supernatants corresponded to the amount of LNT or LNnT consumed, respectively, indicating that that intermediate degradation compound is not metabolized. To further confirm that the LNTII was not fermented, the growth of Y510 and Y521 strains was analyzed in MRS medium supplement with LNTII. The results showed that both strains failed to growth on LNTII and this tri-saccharide remained in the spent supernatants (Fig. 1; Table 2). Galactose was not accumulated in the supernatants of B. dentium when grown in LNT or LNnT (Fig. 2) and that monosaccharide is substrate for this species (Table 1, Fig. 1). These results indicate that the growth supported by LNT or LNnT is only due to the metabolism of the galactose moiety. The B. infantis Y538 strain completely depletes all tested HMOs from the culture medium (Table 2) and no intermediate degradation components were observed. The Bifidobacterium strains were also tested for the ability to utilize the disaccharides lacto-N-biose (LNB) and N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc), which form part of the LNT and LNnT molecules, respectively, as carbon sources. The results showed that both B. dentium strains metabolize LacNAc but not LNB, and B. infantis Y538 consumed both carbohydrates (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage of oligosaccharide utilized by the Bifidobacterium strains in the fermentation conditions described in “Methods”.

| Strains | 2′FL | 3FL | DFL | LNT | LNnT | LNTII | LNB | LacNAc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. dentium Y510 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 ± 6.0 | 80.5 ± 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 88.5 ± 0.5 |

| B. dentium Y521 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.0 ± 0.0 | 12.5 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 33.0 ± 1.0 |

| B. infantis Y538 | 98.0 ± 2.0 | 100 | 99.0 ± 1.0 | 100 | 100 | 24.0 ± 2.0 | 100 | 100 |

2′FL 2′-Fucosyllactose, 3FL 3-fucosyllactose, DFL difucosyllactose, LNT lacto-N-tetraose, LNnT lacto-N-neotetraose, LNTII lacto-N-triose, LNB lacto-N-biose, LacNAc N-acetyllactosamine.

Figure 2.

HPLC chromatograms (Dionex system) of the standard compounds LNT (chromatogram 1), LNnT (chromatogram 2), LNTII (chromatogram 6) and galactose (chromatogram 7), and culture supernatants from Bifidobacterium dentium Y510 grown on MRS basal medium without sugar (chromatogram 3), with LNT (chromatogram 4) or LNnT (chromatogram 5). The arrows showed the LNTII present in the culture supernatants. LNT lacto-N-tetraose, LNnT lacto-N-neotetraose, LNTII lacto-N-triose, nC nanoCoulomb.

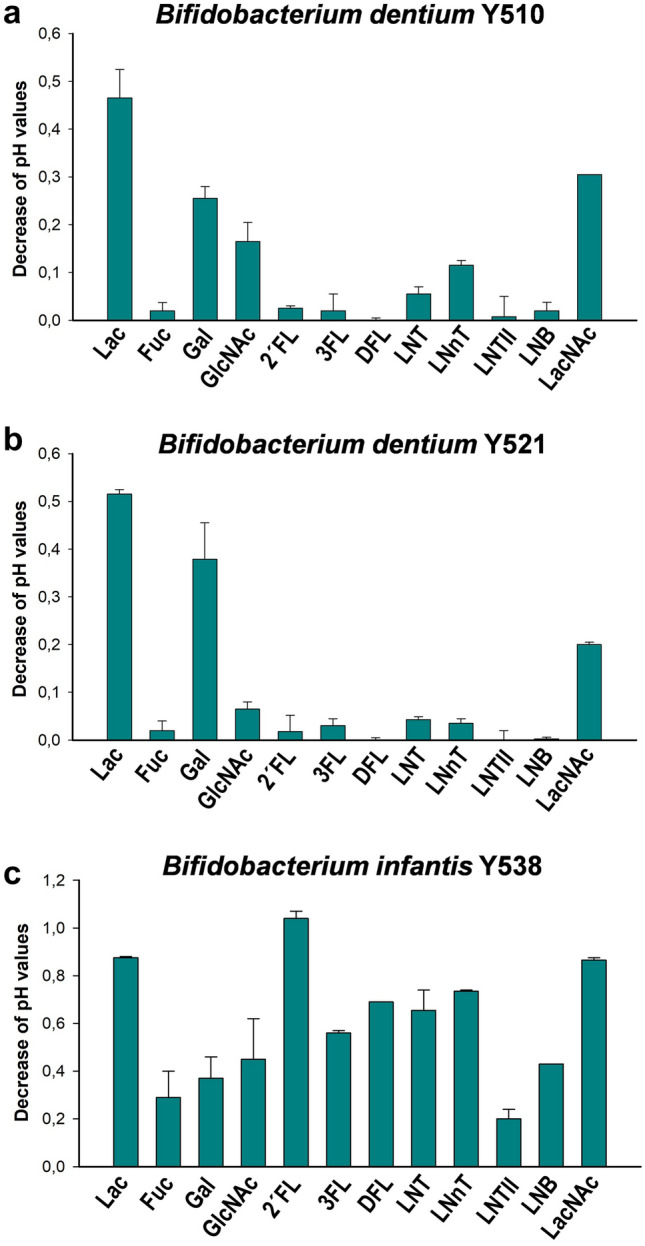

Cellular location of the β-galactosidase activity involved in LNT and LNnT hydrolysis in B. dentium

As shown above, during the growth of B. dentium in LNT or LNnT, peaks of LNTII were detected in the culture medium. However, no β-galactosidase activity was detected in the cell-free supernatant, indicating that the enzymes responsible of the hydrolysis of these HMOs are physically associated with cells (Supplementary Table S1). In order to determine their localization in the cells, the hydrolysis of LNT and LNnT, respectively, was analyzed using whole cells, permeabilized cells and cell-free crude extracts of B. dentium strain Y510 (Fig. 3). LNT and LNnT are broken down to LNTII and galactose by the permeabilized cells and cell-free crude extracts but not by the whole cells. These results indicate that the β-galactosidases responsible of the LNT and LNnT hydrolysis in B. dentium are intracellular.

Figure 3.

HPLC chromatograms (Dionex system) of standard compounds mixture (chromatogram 1) and reaction mixtures containing Bifidobacterium dentium Y510: whole cells (WC) without sugar (chromatogram 2), with LNnT (chromatogram 5) or LNT (chromatogram 8); permeabilized cells (PC) without sugar (chromatogram 3), with LNnT (chromatogram 6) or LNT (chromatogram 9) and cell-free crude extracts (CE) without sugar (chromatogram 4), with LNnT (chromatogram 7) or LNT (chromatogram 10). The red and black arrows showed the Gal and LNTII, respectively present in the reaction mixtures. LNT lacto-N-tetraose, LNnT lacto-N-neotetraose, LNTII lacto-N-triose, Lac lactose, Gal galactose, nC nanoCoulomb.

Galactosidases from B. dentium hydrolyze LNT and LNnT

The β-galactosidases Bga42A and Bga2A release β-1,3 and β-1,4 linked galactose from LNT and LNnT, respectively, in B. infantis18. A BLAST search using the deduced amino acid sequence of Bga42A or Bga2A against the genome of B. dentium JCM 1195 type strain shows the highest homology against locus BBDE_RS03200 (75% identities; 85% positives) and BBDE_RS07935 (57% identities; 72% positives), respectively. These genes encode putative β-galactosidases of the GH42 and GH2 glycoside hydrolase families (http://www.cazy.org), and sequence analysis using the SignalP (version 5.0) program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk) showed that they do not have N-terminal signal peptides, suggesting that they are intracellular enzymes. Based on this, specific primers were used to search for genes homologues to BBDE_RS03200 and BBDE_RS07935 in the B. dentium Y510 isolate. The results showed that this strain contains genes homologues to those. In order to investigate the predicted enzymatic activities encoded by BBDE_RS03200 homolog (designated as bdg42A) and BBDE_RS07935 homolog (designated as bdg2A) on LNT and LNnT, those genes were cloned in Escherichia coli and the corresponding proteins Bdg42A and Bdg2A were purified as His-tagged fusions. They showed a molecular mass of 79 and 118 kDa, respectively, in agreement with the estimated mass of the 6xHis-tagged Bdg42A (79,112 Da) and 6xHis-tagged Bdg2A (118,010 Da) (Supplementary Figure S4). To determine their substrate specificities, both enzymes were first tested for hydrolysis of different 2/4-nitrophenyl (NP) sugars and they only showed activity on 2/4-NP-β-d-galactopyranosides, thus confirming their β-galactosidase specificity (Tables 3, 4). The general properties of Bdg42A and Bdg2A were determined using the substrate 4-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside as follows, respectively: Vmax (μmol/min/mg protein), 25.0 and 14.3; Km (mM), 2.5 and 10.0; optimum pH, pH 7.0 and pH 7.5; optimum temperature, 40 °C and 42 °C.

Table 3.

Activity of enzyme Bdg42A.

| Substratea (structure) | Hydrolysisb | Km (mM) | kcat (s-1) | kcat/Km (mM-1 s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside | + | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside | + | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-glucopyranoside | − | |||

| 2-NP-1-thio- β-d-galactopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-glucuronide | − | |||

| 4-NP-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-d-glucopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-l-fucopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-d-galactopyranoside | − | |||

| Galacto-N-biose (Galβ1-3GalNAc) | + | 8.72 | 0.06 | 0.006 |

| Lacto-N-biose (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) | + | 10.05 | 1.85 | 0.184 |

| Lacto-N-triose (GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | − | |||

| Lacto-N-tetraose (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | + | 5.60 | 22.20 | 3.964 |

| Lacto-N-neotetraose (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | + | 10.85 | 1.00 | 0.092 |

| 6′-Galactopyranosyl-GlcNAc (Galβ1-6GlcNAc) | + | 7.72 | 0.29 | 0.037 |

| 3′-N-Acetylgalactosaminyl-Gal (GalNAcβ1-3Gal) | − | |||

| 3′-N-Acetylglucosaminyl-Man (GlcNAcβ1-3Man) | − | |||

| Lactose (Galβ1-4Glc) | + | 8.46 | 7.14 | 0.843 |

| N-Acetyl-lactosamine (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) | + | 10.45 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Lactulose (Galβ1-4Fru) | + | 11.25 | 3.63 | 0.322 |

| Maltose (Glcα1-4Glc) | − | |||

| N-Acetyl-chitobiose (GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc) | − |

aCarbohydrates used as substrates. NP nitrophenyl, Glc glucose, Gal Galactose, GlcNAc N-acetylglucosamine, GalNAc N-acetylgalactosamine, Man, mannose, Fru fructose.

b+, substrate is totally hydrolyzed after 16 h reaction in the conditions described in “Methods”; − , no activity detected.

Table 4.

Activity of enzyme Bdg2A.

| Substratea (structure) | Hydrolysisb | Km (mM) | kcat (s-1) | kcat/Km (mM-1 s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside | + | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside | + | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-glucopyranoside | − | |||

| 2-NP-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-β-d-glucuronide | − | |||

| 4-NP-N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-d-glucopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-l-fucopyranoside | − | |||

| 4-NP-α-d-galactopyranoside | − | |||

| Galacto-N-biose (Galβ1-3GalNAc) | +/− | nd | nd | |

| Lacto-N-biose (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) | +/− | nd | nd | |

| Lacto-N-triose (GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | − | |||

| Lacto-N-tetraose (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | +/− | nd | nd | |

| Lacto-N-neotetraose (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) | + | 6.75 | 0.67 | 0.099 |

| 6′-Galactopyranosyl-GlcNAc (Galβ1-6GlcNAc) | + | 6.99 | 0.083 | 0.012 |

| 3′-N-Acetylgalactosaminyl-Gal (GalNAcβ1-3Gal) | − | |||

| 3′-N-Acetylglucosaminyl-Man (GlcNAcβ1-3Man) | − | |||

| Lactose (Galβ1-4Glc) | + | 5.59 | 1.21 | 0.216 |

| N-Acetyl-lactosamine (Galβ1-4GlcNAc) | + | 6.69 | 0.154 | 0.023 |

| Lactulose (Galβ1-4Fru) | +/− | nd | nd | |

| Maltose (Glcα1-4Glc) | − | |||

| N-Acetyl-chitobiose (GlcNAcβ1-4GlcNAc) | − |

nd not determined.

aCarbohydrates used as substrates. NP nitrophenyl, Glc glucose, Gal Galactose, GlcNAc N-acetylglucosamine, GalNAc N-acetylgalactosamine, Man mannose, Fru fructose.

b+, substrate is totally hydrolyzed after 16 h reaction in the conditions described in “Methods”; +/−, substrate is partially hydrolyzed after 16 h reaction in the conditions described in “Methods”; − , no activity detected.

Among the HMOs and other natural oligosaccharides tested, Bdg42A hydrolyzed the disaccharides galacto-N-biose (GNB), LNB, 6′-galactopyranosyl-GlcNAc, lactose, LacNAc and lactulose (Table 3). As well, Bdg42A removed the galactose moiety at the non-reducing end of LNT and LNnT. This enzyme did not act on LNTII, 3′-N-acetylgalactosaminyl-Gal, 3′-N-acetylglucosaminyl-Man, maltose and N-acetyl-chitobiose. These results showed therefore that Bdg42A is an exo-β-galactosidase. The enzyme releases galactose from LNT with a high catalytic efficiency compared to that observed for the other substrates evaluated, suggesting a key role in the metabolism of this HMO (Table 3).

Regarding the substrate specificity of Bdg2A on the oligosaccharides assayed, this enzyme hydrolyzed the disaccharides GNB, LNB, 6′-galactopyranosyl-GlcNAc, lactose, LacNAc and lactulose into its monosaccharides constituents, and the tetra-saccharides LNT and LnNT into galactose and LNTII (Table 4). As described for Bdg42A, these results demonstrated that this enzyme is also an exo-β-galactosidase. Bdg2A showed the highest catalytic activity for lactose and it also hydrolyzed 6′-galactopyranosyl-GlcNAc, LacNAc and LNnT (Table 4).

Discussion

HMOs have been proposed as the main metabolites from human milk that directly influence the microbiota composition of the infant gastrointestinal tract9,10. Several studies have shown that specific bifidobacterial species including B. longum subsp. infantis, B. bifidum and B. breve can grow efficiently on HMOs, and their genomes are equipped with genes coding for glycosidases linked to HMOs metabolism10,12,14,15. However, the consumption of individual HMOs by other bacterial species commonly present in the infant gut is not as well established. In this work, bacteria were isolated from breastfed infant faeces and their capability to consume the oligosaccharides 2′FL, 3FL, DFL, LNT and LNnT, that are present in human breast milk, was analyzed. The isolated strains belonging to the species E. faecalis, L. fermentum, L. gasseri, L. paracasei, L. reuteri, S. epidermidis, S. hominis and S. pasteurianus did not utilize any of the HMOs tested. However, B. infantis and B. dentium isolated strains metabolized those HMOs, contributing to the hypothesis that these carbohydrates mainly promote the growth of Bifidobacterium species in the infant gut. Importantly, the extent to which both species utilized HMOs was very different. While B. infantis totally consumed all tested HMOs and resulting intermediary degradation carbohydrates, B. dentium only degraded LNT and LNnT. The two subspecies of B. longum that often colonize the infant intestine are B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. longum, and they differ in their ability to metabolize HMOs. While in the latest subspecies the capacity to metabolize HMOs is limited to specific strains and to certain types of HMOs35, in B. infantis the ability to consume a wide range of HMOs is characteristic of the entire subspecies13,14,36. The ability of the B. infantis Y538 strain to ferment all the HMOs assayed here is in agreement with the high capacity to consume HMOs widely described for B. infantis13,14,36. This species contains genes encoding α-l-fucosidases involved in the metabolism of 2′FL, 3FL and DFL14. Recently, two FL transporters with distinct but overlapping functions involved in the assimilation of these HMOs have also been characterized37. As well, β-galactosidases for LNT and LNnT have already been characterized in this species18.

Contrarily to B. infantis, the isolated strains Y510 and Y521 of B. dentium grow inefficiently in the presence of LNT or LNnT as carbon sources, utilizing only the galactose moiety and releasing LNTII into the environment. The accumulation of this tri-saccharide in the culture media as a result of LNnT degradation has also been demonstrated for L. acidophillus strain NCFM, which has an extracellular β-galactosidase active on LNnT25. Unlike this strain, the hydrolysis of LNT and LNnT by permeabilized cells, but not by whole cells of B. dentium strain Y510, indicated that the β-galactosidases act intracellularly on those carbohydrates. Previous results have shown in L. casei that fucosyl-oligosaccharides and fucosylated N-glycopeptides are hydrolyzed inside the cells by the α-l-fucosidases AlfB and AlfC, and that the released l-fucose is excreted into the environment26,38. The β-galactosidase Bdg42A characterized here is homologous to the β-galactosidases Bga42A (75% identities; 85% positives) and LntA (76% identities; 86% positives) previously described from B. infantis and B. breve, respectively16,18. The three enzymes exhibit the highest activity on LNT and hydrolyze it into galactose and LNTII. For B. breve species, it has been shown that LNT is intracellularly hydrolyzed by LntA16, but whether Bdg42A has the same role in B. dentium, further analyses are needed. The other β-galactosidase, Bdg2A, analyzed here showed homology to Bga2A (57% identities; 73% positives) from B. infantis, and to LacZ2 (62% identities; 73% positives) and LacZ6 (60% identities; 71% positives) from B. breve16,18. These four enzymes showed hydrolytic activity on type-2 oligosaccharides, including lactose and LNnT, and they are essentially inactive on type-1 oligosaccharides. These results suggest a similar function of those β-galactosidases in HMOs metabolism.

The LNTII resulting from the metabolism of LNT and LNnT in B. infantis and B. breve is further catabolized by β-N-acetylglucosaminidases of the GH20 glycoside hydrolase family that release GlcNAc and lactose16,39. Curiously, the LNTII moiety resulting from the degradation of LNT or LNnT by B. dentium was accumulated quantitatively in the culture supernatants. In agreement with this, only two out of 38 B. dentium strains analyzed contain genes predicted to encode glycosidases belonging to the GH20 family40. Previous studies have demonstrated that degradation of HMOs by some Bifidobacterium species support growth of other species by cross-feeding on liberated carbohydrates41. The LNTII excreted into the environment from LNT and LNnT metabolism by B. dentium could allow growth of other species within the gut ecosystem. Indeed, bacterial species associated with the infant gastrointestinal tract have been described to utilize LNTII as carbon source28.

The results obtained in the present work showed differential utilization of HMOs, HMO-derived glycans and monosaccharides among specific bacteria isolated from infant faeces. In particular B. dentium, while previously shown as an opportunistic pathogen in the oral cavity rich in simple sugars42, remained uncharacterized how this bacterium is able to adapt to the infant gut, where complex carbohydrates such as HMOs are abundant. Our findings have provided insights into the utilization of type 1 and type 2 HMOs by B. dentium, and the possible involvement of specific β-galactosidase enzymes in its metabolism. Future work, including whole genome sequencing of the B. dentium strains characterized here, would be needed to provide additional understanding of oligosaccharide metabolism by these bacteria.

Methods

Bacteria isolation from infant fecal samples

Stool samples from four breastfed infants between one and three months old were collected, stored and cryopreserved as previously described43. Serial dilutions (10–3–10–8) of a fecal sample mix were plated on Rogosa agar medium (Pronadisa), MRS basal27 agar medium supplemented with lactulose 0.5% or inulin 0.5%, MRS (Difco) agar medium with mupirocin 50 mg/L or nalidixic acid 25 mg/L. All MRS agar media contain also cysteine 0.1%. The culture plates were incubated in anaerobic jars at 37 °C during 48 h. One hundred and fifty colonies (50 colonies from the Rogosa agar medium and 25 colonies from each of the four different MRS agar media) were randomly selected at the lowest dilutions giving single colonies, and subjected to randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis. RAPD-PCR reactions were performed as previously described44 and using the primers MCV (AGTCAGCCAC)45, PER1 (AAGAGCCCGT)33 and CORR1 (TGCTCTGCCC)33. The reaction products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. 16S rRNA gene of representative isolates was amplified by PCR using cells from the colonies as the template and the primers 27F (AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG)46, 924R (CTTGTGCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC)47 and 1492R (GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT)48. The PCR products were sequenced by Eurofins Genomics (http://www.eurofinsgenomics.com). The sequences were used in BLAST searches to identify each isolated.

Culture of bacterial strains with individual HMOs, HMOs-derived carbohydrates and monosaccharides

The isolated strains belonging to the genera Enterococcus, Limosilactobacillus, Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus were grown overnight at 37 °C under static conditions as previously described27 on MRS basal medium containing: bactopeptone (Difco), 10 g l−1; yeast extract (Pronadisa), 4 g l−1; sodium acetate, 5 g l−1; tri-ammonium citrate, 2 g l−1; magnesium sulphate 7-hydrate, 0.2 g l−1; manganese sulphate monohydrate, 0.05 g l−1; Tween 80, 1 ml l−1 and l-cysteine 0.1%. Overnight cultures were diluted to an optical density at 595 nm of 0.1 in 100 µl of MRS basal medium containing 2 mM lactose, l-fucose, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL), 3-fucosyllactose (3FL), 2′,3-difucosyllactose (DFL), lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) or lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT). All the oligosaccharides were obtained from Biosynth Carbosynth (Compton, Berkshire, United Kingdom). Bacterial growth was tracked by measuring at 595 nm during 24 h at 37 °C in 96-well plates in a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). The growth of the isolated Bifidobacterium strains in the presence of lactose, l-fucose, galactose, GlcNAc, 2′FL, 3FL, DFL, LNT, LNnT, lacto-N-triose (LNTII), lacto-N-biose (LNB) or N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc) at 2 mM was tested in MRS basal medium as previously described23 with some modifications. Briefly, the Bifidobacterium strains were cultured overnight on MRS basal medium and diluted to an OD595 of 0.1 in 200 μl of MRS basal medium supplemented with each carbohydrate in 96-well plates. Cultures were grown at 37 ºC under anaerobic conditions using an anaerobic atmosphere generation system (Anaerogen, Oxoid). Bacterial growth was determined by measuring the pH of the culture and OD (595 nm) at 48 h. At least two independent biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for each growth assay. Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

HMOs, HMOs-derived carbohydrates and monosaccharides analysis in culture supernatants

To determine the carbohydrates present in the supernatants from the isolated strains cultures, cells were removed by centrifugation and the supernatants were filtrated and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography using an ICS3000 chromatographic system (Dionex) and a CarboPac PA100 column with pulsed amperometric detection. A gradient of NaOH was used at 27 °C and at a flow rate of 1 ml/min for the analysis of fucosyl-oligosaccharides (10–100 mM NaOH for 15 min), and a combined gradient of NaOH and acetic acid was used at the same temperature and flow rate for the rest of the oligosaccharides analyzed (100 mM NaOH for 2 min, 100–300 mM NaOH for 3 min, 300 mM NaOH and 0–300 mM acetic acid for 15 min). Monosaccharides and oligosaccharides were confirmed by comparison of their retention times with those of standards.

β-Galactosidase activity in supernatants, whole cells, permeabilized cells and cell-free crude extracts of B. dentium Y510 cultures

The B. dentium Y510 strain was grown overnight at 37 °C on 50 ml of MRS basal medium27 supplemented with 0.1% l-cysteine and 0.5% glucose, and under anaerobic conditions using an anaerobic atmosphere generation system (Anaerogen, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with Tris–HCl buffer 50 mM, pH 7.5 and suspended in this buffer to an OD595 of 2. Cells were permeabilized using deoxycholic acid as previously described with some modifications49. Four hundred microliters of cell suspension were incubated with 400 μl of deoxycholic acid 20 mM under agitation for 5 min. Cell-free crude extract was prepared as previously described50. Protein concentration in the crude extracts was determined with the Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (BioRad). The β-galactosidase enzyme activity was determined by measuring the 2-nitrophenol released (absorbance at 404 nm) from 2-nitrophenyl (NP)-β-d-galactopyranoside (oNPGal) at 37 °C in 96-well plates (POLARstar Omega microplate reader, BMG Labtech). The reaction mixtures (50 μl) containing 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH7.0, 5 mM oNPGal were started by adding 40 μl of culture supernatant, 10 μl of whole cells, 10 μl of permeabilized cells or 10 μl of cell-free crude extract.

The β-galactosidase activity on LNT and LNnT was determined using reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH7.0, 5 mM LNT or LNnT, and 8.5 μl of whole cells, permeabilized cells or cell-free crude extract. The reactions were incubated at 37 °C overnight, and after been diluted 10 times they were analyzed by chromatography using the Dionex system and column described above. A gradient of 10 mM to 150 mM NaOH was used at 27 °C for 30 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min.

Expression and purification of His-tagged Bdg42A and Bdg2A

Total DNA was isolated from B. dentium Y510 using the MasterPure DNA extraction Kit (Epicentre) following the manufacturer’s protocols with some modifications44. The coding regions of bdg42A and bdg2A were amplified by PCR with the Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermoscientific) using genomic DNA from B. dentium Y510 and the primers pairs: BDG3SacIF (5′-TTTTGAGCTCATGACGCAGCGCAGAGCAC)/ BDG3HindIIIR (5′-TTTTAAGCTTTTACTTCCTGAGCACGATTACG) and BDG4SacIF (5′-TTTTGAGCTCATGTCGCATATCTTTTCCTCAAC)/ BDG4HindIIIR (5′-TTTTAAGCTTTCAGAACAGCTCCAGCATCAC), respectively, to which restriction sites (underlined) were added to the 5′ and 3′ ends. The digested PCR products were cloned into pQE80 (Qiagen) and the resulting plasmids, pQEbdg42A and pQEbdg2A, respectively, were transformed by electroporation into Escherichia coli DH10B. E. coli transformants were selected with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and DNA sequencing allowed to verified the correct sequence of the inserts. One clone of each, PE177 (pQEbdg42A) and PE178 (pQEbdg2A), was grown in Luria–Bertani medium (Oxoid), induced with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 1 mM) and the recombinant proteins purified from the cleared extracts as described previously27. SDS-PAGE was used to determine the fractions containing the proteins of interest, which were kept frozen at − 80 °C with 20% glycerol. Protein concentrations were determined with the Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (BioRad).

Bdg42A and Bdg2A enzyme activities

The activity of the purified Bdg42A and Bdg2A enzymes were assayed with 2/4-NP-sugars (Tables 3, 4) at 5 mM in 96-well plates incubated at 37 °C. Reaction mixtures (100 µl) containing the substrate in 100 mMTris-HCl buffer, pH 7.0, were initiated by adding 0.44 µg and 0.30 µg of enzyme Bdg42A and Bdg2A, respectively. Using these assay conditions, the optimal pH was determined with 5 mM 4-NP-β-d-galactopyranoside (pNPGal) using 100 mM phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 4.0–7.5), 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5.0–8.5) and 100 mM glycine–NaOH buffer (pH 8.5.0–9.5). The optimal temperature and kinetic studies with pNPGal were performed as previously described28. The capability of Bdg42A and Bdg2A to hydrolyze natural oligosaccharides was assayed using several substrates listed in Tables 3 and 4. The reactions (10 µl) were performed at 37 °C for 16 h using 2 mM substrate in 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.0. For kinetic studies with natural oligosaccharides, varying concentrations from 1 to 15 mM substrate were used in the same buffer and the reactions were incubated at 37 °C for different periods of time ranging from 30 s to 8 min. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by chromatography using the Dionex system and column described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The partial nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene amplicons have been deposited at the GenBank database under the accession numbers MZ323909 to MZ323948, and the sequences of the genes encoding the β-galactosidases Bdg42A and Bdg2A from B. dentium strain Y510 under the accession numbers MZ313538 and MZ313539.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the use of human samples were followed. The study protocol with the registration number H1544010468380 was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

EMM-G was supported by a pre-doctoral Contract PRE2018-085768 by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICIN)/Spanish State Research Agency (AEI)/10.13039/501100011033 and by "ESF Investing in your future".

Author contributions

J.R.D. and M.J.Y. conceived and designed research. E.M.M.-G. and A.R.C. conducted experiments. M.J.Y. drafted the manuscript. E.M.M.-G., A.R.C. and J.R.D. helped improving the draft. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work is part of the Grants AGL2017-84165-C2 (1-R and 2-R) and PID2020-115403RB (C21 and C22) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICIN)/Spanish State Research Agency (AEI)/10.13039/501100011033, and by "ERDF A way of making Europe".

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-02741-x.

References

- 1.Kobata A. Structures and application of oligosaccharides in human milk. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. Phys. Biol. Sci. 2010;86:731–747. doi: 10.2183/pjab.86.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurl S, Munzert M, Boehm G, Matthews C, Stahl B. Systematic review of the concentrations of oligosaccharides in human milk. Nutr. Rev. 2017;75:920–933. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X. Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOS): Structure, function, and enzyme-catalyzed synthesis. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2015;72:113–190. doi: 10.1016/bs.accb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunz C, et al. Influence of gestational age, secretor, and lewis blood group status on the oligosaccharide content of human milk. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017;64:789–798. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engfer MB, Stahl B, Finke B, Sawatzki G, Daniel H. Human milk oligosaccharides are resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1589–1596. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plaza-Diaz J, Fontana L, Gil A. Human milk oligosaccharides and immune system development. Nutrients. 2018 doi: 10.3390/nu10081038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides in the prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis: A journey from in vitro and in vivo models to mother-infant cohort studies. Front. Pediatr. 2018;6:385. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray C, et al. Human milk oligosaccharides: The journey ahead. Int. J. Pediatr. 2019;2019:2390240. doi: 10.1155/2019/2390240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang M, et al. Fecal microbiota composition of breast-fed infants is correlated with human milk oligosaccharides consumed. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015;60:825–833. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakanaka M, et al. Varied pathways of infant gut-associated Bifidobacterium to assimilate human milk oligosaccharides: Prevalence of the gene set and its correlation with bifidobacteria-rich microbiota formation. Nutrients. 2019 doi: 10.3390/nu12010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuñiga M, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. Utilization of host-derived glycans by intestinal Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:1917. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiz-Moyano S, et al. Variation in consumption of human milk oligosaccharides by infant gut-associated strains of Bifidobacterium breve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:6040–6049. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01843-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duar RM, et al. Comparative genome analysis of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis strains reveals variation in human milk oligosaccharide utilization genes among commercial probiotics. Nutrients. 2020 doi: 10.3390/nu12113247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zabel BE, et al. Strain-specific strategies of 2'-fucosyllactose, 3-fucosyllactose, and difucosyllactose assimilation by Bifidobacterium longum subsp infantis Bi-26 and ATCC 15697. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:15919. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72792-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katoh T, et al. Enzymatic adaptation of Bifidobacterium bifidum to host glycans, viewed from glycoside hydrolyases and carbohydrate-binding modules. Microorganisms. 2020 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James K, Motherway MO, Bottacini F, van Sinderen D. Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 metabolises the human milk oligosaccharides lacto-N-tetraose and lacto-N-neo-tetraose through overlapping, yet distinct pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38560. doi: 10.1038/srep38560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sela DA, et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp infantis ATCC 15697 alpha-fucosidases are active on fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:795–803. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06762-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida E, et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp infantis uses two different beta-galactosidases for selectively degrading type-1 and type-2 human milk oligosaccharides. Glycobiology. 2012;22:361–368. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menard O, Butel MJ, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Waligora-Dupriet AJ. Gnotobiotic mouse immune response induced by Bifidobacterium sp. strains isolated from infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:660–666. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01261-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turroni F, et al. Exploring the diversity of the bifidobacterial population in the human intestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:1534–1545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02216-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duranti S, et al. Maternal inheritance of bifidobacterial communities and bifidophages in infants through vertical transmission. Microbiome. 2017;5:66. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0282-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lugli GA, et al. Investigating bifidobacteria and human milk oligosaccharide composition of lactating mothers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becerra JE, Coll-Marques JM, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. Preparative scale purification of fucosyl-N-acetylglucosamine disaccharides and their evaluation as potential prebiotics and antiadhesins. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:7165–7176. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bidart GN, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Palomino-Schatzlein M, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. Human milk and mucosal lacto- and galacto-N-biose synthesis by transgalactosylation and their prebiotic potential in Lactobacillus species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;101:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thongaram T, Hoeflinger JL, Chow J, Miller MJ. Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by probiotic and human-associated bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. Int. J. Dairy Sci. 2017;100:7825–7833. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Diaz J, Rubio-del-Campo A, Yebra MJ. Lactobacillus casei ferments the N-acetylglucosamine moiety of fucosyl-alpha-1,3-N-acetylglucosamine and excretes L-fucose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:4613–4619. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00474-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bidart GN, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Monedero V, Yebra MJ. A unique gene cluster for the utilization of the mucosal and human milk-associated glycans galacto-N-biose and lacto-N-biose in Lactobacillus casei. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;93:521–538. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bidart GN, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Yebra MJ. The extracellular wall-bound beta-N-Acetylglucosaminidase from Lactobacillus casei Is Involved in the metabolism of the human milk oligosaccharide lacto-N-triose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:570–577. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02888-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bidart GN, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Perez-Martinez G, Yebra MJ. The lactose operon from Lactobacillus casei is involved in the transport and metabolism of the human milk oligosaccharide core-2 N-acetyllactosamine. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:7152. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25660-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu ZT, Chen C, Newburg DS. Utilization of major fucosylated and sialylated human milk oligosaccharides by isolated human gut microbes. Glycobiology. 2013;23:1281–1292. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Daele E, Knol J, Belzer C. Microbial transmission from mother to child: Improving infant intestinal microbiota development by identifying the obstacles. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;45:613–648. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2019.1680601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albesharat R, Ehrmann MA, Korakli M, Yazaji S, Vogel RF. Phenotypic and genotypic analyses of lactic acid bacteria in local fermented food, breast milk and faeces of mothers and their babies. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;34:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarocki P, et al. Comparison of various molecular methods for rapid differentiation of intestinal bifidobacteria at the species, subspecies and strain level. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0779-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy D, Sirois S. Molecular differentiation of Bifidobacterium species with amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis and alignment of short regions of the ldh gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000;191:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrido D, et al. A novel gene cluster allows preferential utilization of fucosylated milk oligosaccharides in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum SC596. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35045. doi: 10.1038/srep35045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunesova V, Lacroix C, Schwab C. Fucosyllactose and L-fucose utilization of infant Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:248. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0867-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakanaka M, et al. Evolutionary adaptation in fucosyllactose uptake systems supports bifidobacteria-infant symbiosis. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw7696. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Becerra JE, et al. Unique microbial catabolic pathway for the human core N-glycan constituent fucosyl-alpha-1,6-N-Acetylglucosamine-Asparagine. MBio. 2020 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02804-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrido D, Ruiz-Moyano S, Mills DA. Release and utilization of n-acetyl-d-glucosamine from human milk oligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis. Anaerobe. 2012;18:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lugli GA, et al. Decoding the genomic variability among members of the Bifidobacterium dentium species. Microorganisms. 2020 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8111720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gotoh A, et al. Sharing of human milk oligosaccharides degradants within bifidobacterial communities in faecal cultures supplemented with Bifidobacterium bifidum. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ventura M, et al. The Bifidobacterium dentium Bd1 genome sequence reflects its genetic adaptation to the human oral cavity. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubio-Del-Campo A, et al. Infant gut microbiota modulation by human milk disaccharides in humanized microbiome mice. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:1–20. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1914377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubio-Del-Campo A, Alcantara C, Collado MC, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Yebra MJ. Human milk and mucosa-associated disaccharides impact on cultured infant fecal microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:11845. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68718-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tynkkynen S, Satokari R, Saarela M, Mattila-Sandholm T, Saxelin M. Comparison of ribotyping, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in typing of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and L. casei strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:3908–3914. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.9.3908-3914.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rudi K, Skulberg OM, Larsen F, Jakobsen KS. Strain characterization and classification of oxyphotobacteria in clone cultures on the basis of 16S rRNA sequences from the variable regions V6, V7, and V8. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:2593–2599. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2593-2599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller CS, et al. Short-read assembly of full-length 16S amplicons reveals bacterial diversity in subsurface sediments. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taranto MP, Perez-Martinez G, Font de Valdez G. Effect of bile acid on the cell membrane functionality of lactic acid bacteria for oral administration. Res. Microbiol. 2006;157:720–725. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia-Mantrana I, Yebra MJ, Haros M, Monedero V. Expression of bifidobacterial phytases in Lactobacillus casei and their application in a food model of whole-grain sourdough bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016;216:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.