Abstract

Background

Our recent studies demonstrate that the focal adhesion protein Kindlin-2 exerts crucial functions in the mesenchymal stem cells, mature osteoblasts and osteocytes in control of early skeletal development and bone homeostasis in mice. However, whether Kindlin-2 plays a role in osteoprogenitors remains unclear.

Materials and methods

Mice lacking Kindlin-2 expression in osterix (Osx)-expressing cells (i.e., osteoprogenitors) were generated. Micro-computerized tomography (μCT) analyses, histology, bone histomorphometry and immunohistochemistry were performed to determine the effects of Kindlin-2 deletion on skeletal development and bone mass accrual and homeostasis. Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) from mutant mice (Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre) and control littermates were isolated and determined for their osteoblastic differentiation capacity.

Results

Kindlin-2 was highly expressed in osteoprogenitors during endochondral ossification. Deleting Kindlin-2 expression in osteoprogenitors impaired both intramembranous and endochondral ossifications. Mutant mice displayed multiple severe skeletal abnormalities, including unmineralized fontanel, limb shortening and growth retardation. Deletion of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors impaired the growth plate development and largely delayed formation of the secondary ossification center in the long bones. Furthermore, adult mutant mice displayed a severe low-turnover osteopenia with a dramatic decrease in bone formation which exceeded that in bone resorption. Primary BMSCs isolated from mutant mice exhibited decreased osteoblastic differentiation capacity.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates an essential role of Kinlind-2 expression in osteoprogenitors in regulating skeletogenesis and bone mass accrual and homeostasis in mice.

The translational potential of this article

This study reveals that Kindlin-2 through its expression in osteoprogenitor cells controls chondrogenesis and bone mass. We may define a novel therapeutic target for treatment of skeletal diseases, such as chondrodysplasia and osteoporosis.

Keywords: Kindlin-2, Osteoprogenitor, Skeletogenesis, Chondrodysplasia, Low-turnover osteopenia

1. Introduction

In vertebrates, bone formation begins in embryonic mesenchyme and occurs through two distinct processes, i.e., intramembranous and endochondral ossification [1,2]. Flat bones, such as the skull vault and occipital bones, are formed through intramembranous ossification, in which mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) directly condense and differentiate into osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts, and, terminally, osteocytes [3,4]. The endochondral ossification forms the majority of skeletal elements, including all long bones of the axial skeleton (vertebrae and ribs) and the appendicular skeleton (limbs) [3,4]. During this process, MSCs firstly condense and differentiate into chondrocytes to form a cartilaginous framework. The cartilaginous framework is then digested by osteoclasts and replaced by bone-forming osteoblasts to create an ossification center for the growth of skeleton [5]. In the mature skeleton, bone constantly undergoes a process called “bone remodeling”, in which old bone is removed by osteoclastic bone resorption and then replaced by new bone through osteoblastic bone formation [6,7]. Abnormal bone remodeling causes multiple bone diseases, such as osteoporosis, inflammatory arthritis and Paget's disease of bone [[8], [9], [10], [11]].

Kindlins are focal adhesion proteins that bind to and activate integrins and, thereby, regulate cell adhesion, migration, and signaling [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. In mammalian cells, Kindlin family proteins have three members, i.e., Kindlin- 1, -2 and -3, encoded by genes Fermt1, Fermt2 and Fermt3, respectively [[18], [19], [20]]. Kindlin-2 has been reported to be involved in regulation of the development and homeostasis of multiple organs and tissues, including skeleton, kidney, heart, pancreas, adipose tissue, small intestine testicle, and neural system, through both integrin-dependent and integrin-independent mechanisms [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]]. For example, Kindlin-2 expression in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal progenitors is essential for mesenchymal cell differentiation and early skeletal development [21,37]. Furthermore, Kindlin-2 modulates bone remodelling by control of expression of sclerostin and receptor activator of nuclear factor-κ B ligand (Rankl) in osteocytes [22,23,25]. However, whether and how Kindlin-2 plays a role in osteoprogenitors remains unclear.

In this study, we utilize the Cre-Lox technology to conditionally delete Kindlin-2 expression in osteoprogenitors using the OsxCre transgenic mice. We find that Kindlin-2 ablation in osteoprogenitors results in multiple defects during skeletal development and causes a severe low-turnover osteopenia in adult mice. Loss of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors severely impairs the osteoblastic differentiation capacity of BMSCs and thereby bone mass accrual and homeostasis.

2. Results

2.1. Kindlin-2 is highly expressed in osteoblast progenitors during endochondral ossification

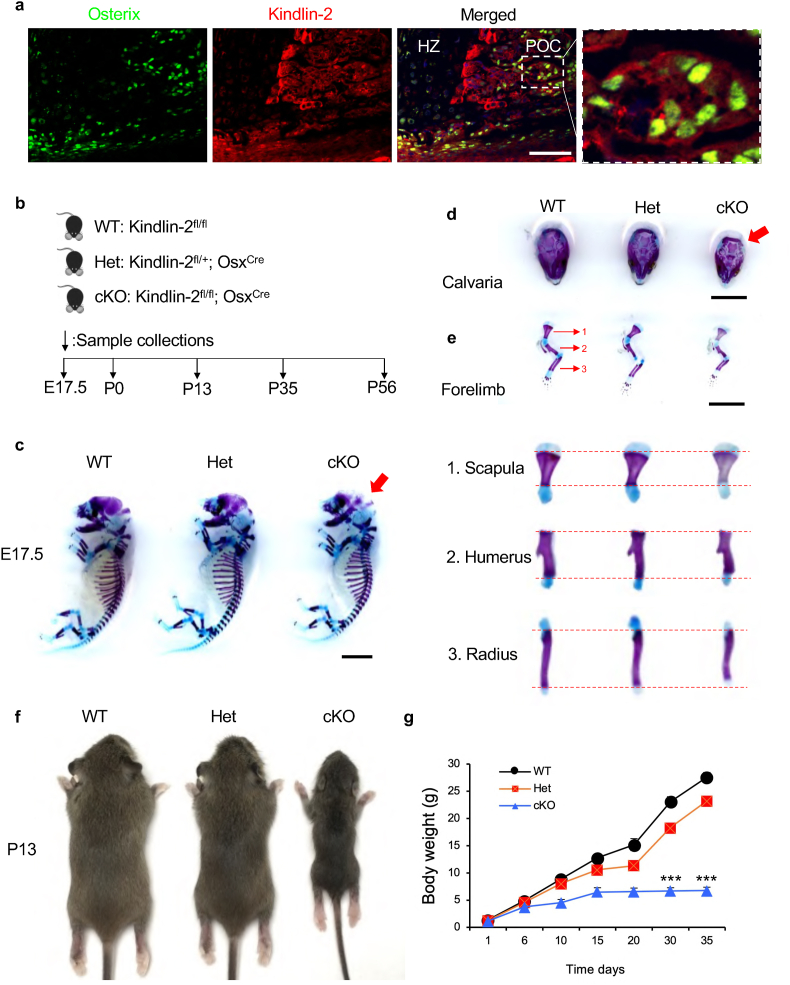

To investigate the potential role of Kindlin-2 in osterix (Osx)-expressing osteoprogenitors, we firstly performed immunofluorescence (IF) staining on humeral sections from newborn C57BL/6 mice using antibodies against Osx and Kindlin-2. Results revealed that Kindlin-2 protein was highly expressed in the Osx-expressing cells during endochondral ossification (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCremice display multiple striking skeletal abnormalities. (a) Immunofluorescent (20) staining of humeral sections from newborn C57/BL6 mice using antibodies against Osx and Kindlin-2. Scale bar: 50 μm. Higher magnification images (right panels) showing the expression of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing cells in primary ossification center (POC). HZ: hypertrophic zone. (b) A schematic diagram illustrating the experimental design. (c) Alizarin red & alcian blue double stain of E17.5 skeletons. Red arrow indicates the unmineralized fontanel in cKO embryos. Scale bar, 0.25 cm (d-e) Calvariae (d) and forelimbs (e) from E17.5 embryos. Higher magnification images (lower panels) showing the scapula (1), humerus (2) and radius (3). Scale bar, 0.25 cm. (f) Representative images of male WT, Het and cKO mice at P13. (g) The growth curve of WT, Het and cKO mice (N = 6 mice per group). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). ∗∗∗P < 0.001. E: embryonic; P: postnatal.

2.2. Deletion of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors causes multiple striking skeletal abnormalities in mice

The high expression of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors observed above prompted us to determine whether Kindlin-2 has a role in these cells during skeletal development. To do this, we deleted its expression in Osx-expressing cells. Kindlin-2 fl/fl mice, in which exons 5 and 6 of Kindlin-2 gene are flanked by loxP sites, were crossed with the OsxCre transgenic mice to obtain Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice. Further crossbreeding of the Kindlin-2fl/fl mice with Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice successfully generated the Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice. Note: a high Cre-recombination efficiency was observed in primary ossification center in neonatal bone of OsxCre mice (Supplementary Fig. 1).

We compared the skeletal development of Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice with that of Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and Kindlin-2fl/fl (used as control in this study) littermates at different time points as indicated in Fig. 1b. Kindlin-2 fl/fl; OsxCre mice survived into adulthood, but the homozygote mice displayed severe skeletal abnormalities (Fig. 1c–g). At E17.5, Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice displayed a larger unmineralized fontanel (Fig. 2c and d) and limb shortening (Fig. 2c,e) when compared with control mice, suggesting that both intramembranous and endochondral ossifications are affected by Kindlin-2 loss. Starting at P13, Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice displayed severe growth retardation, characterized by significantly shorter stature (Fig. 2f) and lower body weight (Fig. 2g) when compared with Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and control littermates.

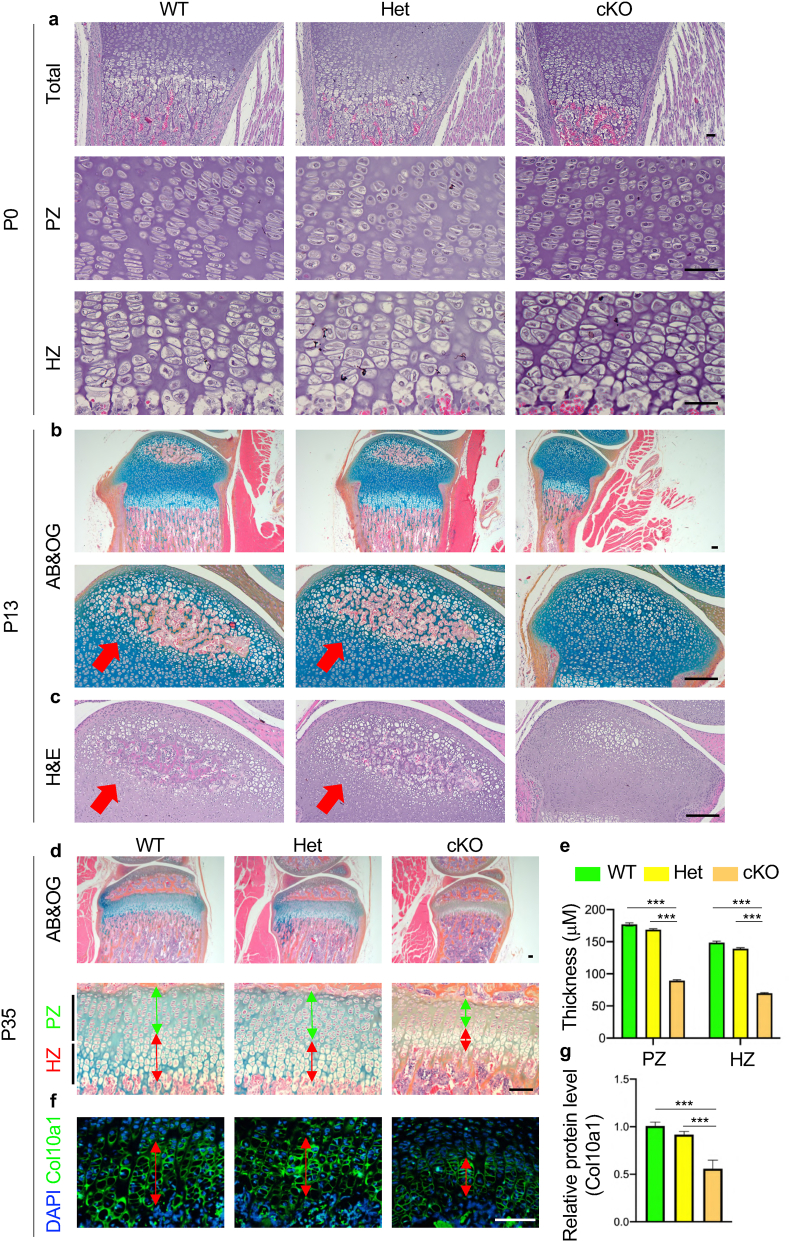

Figure 2.

Delayed endochondral ossification in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCremice. (a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of tibia sections from WT, Het and cKO mice at P0. Higher magnification images of the proliferative zone (PZ) and the hypertrophic zone (HZ) are shown in lower panels. Scale bar, 40 μm (b-c) Representative images of alcian blue & orange G (AB&OG)-stained (b) and H&E-stained (c) tibial sections at P13 showing severe delay in secondary ossification center (SOC) formation in cKO mice. Red arrow indicates the SOC formation. Scale bar, 80 μm. (d) Representative images of AB&OG-stained tibia sections at P35. Higher magnification images showing the growth plate (lower panels). Green double headed arrow indicates the thickness of PZ. Red double headed arrow indicates the thickness of HZ. Scale bar, 80 μm. (e) Quantitative analyses of the thicknesses of PZ and HZ. (f) Immunofluorescent (IF) staining of Col10a1 expression in HZ of P35 growth plate. Red double headed arrow indicates the thickness of HZ. Scale bar, 80 μm. (g) Relative protein level of Col10a1. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

2.3. Deletion of Kindlin-2 impairs the growth plate development and largely delays formation of the secondary ossification center in the long bones

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of tibial sections from P0 mice showed that primary ossification center (POC) was formed in both the control and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice (Fig. 2a, upper panels). At this time point, no marked alteration was observed in the proliferative zone (PZ) (Fig. 2a, middle panels) and the hypertrophic zone (HZ) (Fig. 2a, lower panels) in the tibial growth plate in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice. Interestingly, at P13, while secondary ossification center (SOC) was observed in both control and Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice, the formation of SOC was significantly delayed in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice (Fig. 2b and c). At P35, a significant reduction in the thickness of growth plate was observed in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice (Fig. 2d, upper panels). The thicknesses of both PZ and HZ were thinner in the growth plate of Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice than those of Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice and control littermates (Fig. 2d and e). In addition, we performed immunofluorescent staining to detect the expression of Col10a1, a well-established marker for hypertrophic chondrocytes, in growth plate of P35 mice (20). Consistent with results from histological staining, the thickness of Col10a1-positive HZ was significantly decreased in the growth plate of Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice compared to that in Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice and control littermates (Fig. 2f and g). Results from H&E-stained calvarial sections of P35 mice showed that Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice exhibited markedly decreased bone mass and intramembranous ossification in the calvariae when compared with control mice (Supplementary Fig. 2).

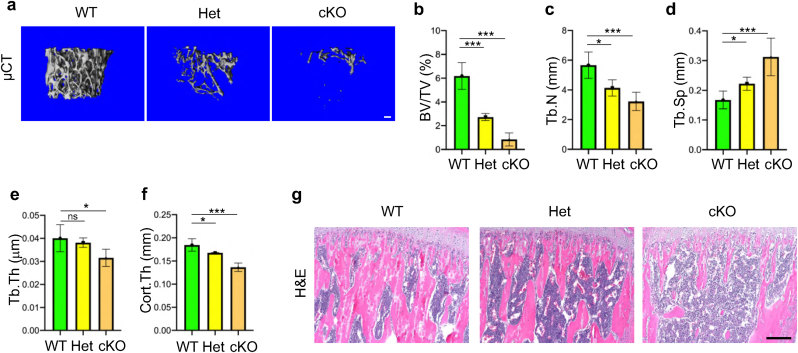

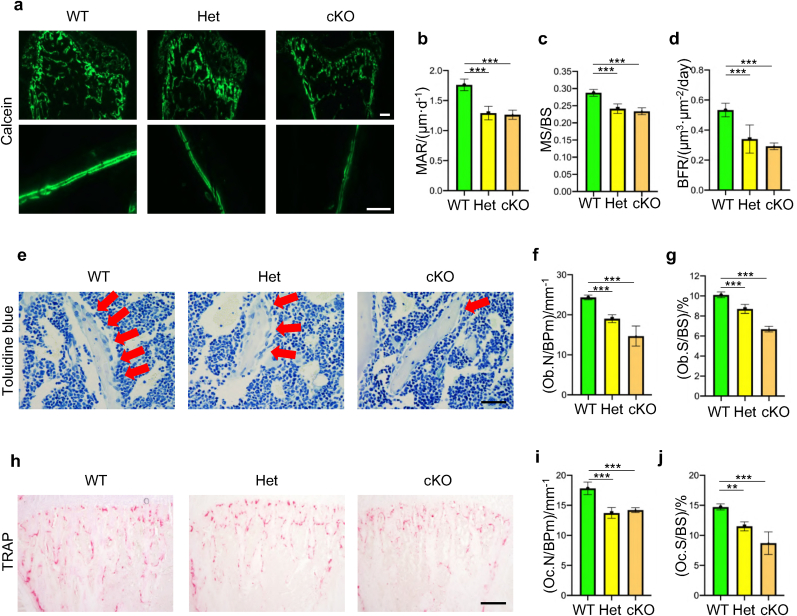

2.4. Mice lacking Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors develop severe low-turnover osteopenia in adult stage

We further determined whether deletion of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors impacts bone mass accrual and homeostasis in adult mice. To this end, we performed micro-computerized tomography (μCT) analysis of the distal femurs and found dramatically decreased bone mass in both Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice when compared with control littermates at 8 weeks of age (Fig. 3a). At this time point, the BV/TV of distal femurs was reduced by 56% in Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice, and by 86% in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice, when compared with that in control mice (Fig. 3b) (6.18 ± 1.12 in control group versus 2.72 ± 0.29 in Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre group and 0.84 ± 0.54 in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre group, P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc test). Loss of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing cells markedly decreased the Tb.N, Tb.Th and Cort.Th and increased the Tb.Sp in distal femurs (Fig. 3b–f). H&E staining showed that the trabecular bone volume was markedly reduced in proximal tibiae of Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre than that in control littermates (Fig. 3g). We performed calcein double labeling experiments to measure the in vivo bone-forming activity by osteoblasts and found significant decreases in mineral apposition rate (MAR), mineralizing surface per bone surface (MS/BS), and bone formation rate (BFR) in the tibial metaphyseal cancellous bones in 8-week-old Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice when compared with those in control controls (Fig. 4a–d). The results from toluidine blue staining showed that the osteoblast number/bone perimeter (Ob.N/BPm) and osteoblast surface/bone surface (Ob.S/BS) were dramatically decreased in Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice compared with those in their control littermates (Fig. 4e–g). We further performed the tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining of tibial sections and found that the osteoclast number/bone perimeter (Oc.N/BPm) and osteoclast surface/bone surface (Oc.S/BS) were significantly decreased in the tibial trabecular bones in Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre and Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre compared with those in control mice (Fig. 4h–j). Collectively, these data show that mice lacking Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors develop severe low-turnover osteopenia.

Figure 3.

Deletion of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors decreases bone mass in mice. (a) Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction from microcomputed tomography (μCT) scans of distal femur trabecular bone from WT, Het and cKO mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bar: 100 μm (b-f) Quantitative mCT analyses of bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and cortical thickness (Cort.Th). N = 5 for each group. (g) H&E-stained tibia sections from WT, Het and cKO mice at 8 weeks of age. Scale bar: 160 μm.

Figure 4.

Kindlin-2 loss decreases both osteoblast and to a less extent osteoclast formation in bone (a-d) In vivo double calcein labeling for bone formation detection in proximal tibias. Scale bar: 400 μm. Statistical analysis for MAR (b), MS/BS (c) and BFR (d) of metaphyseal trabecular bones. N = 5 for each group. (e) Toluidine blue staining of tibial sections of 8-week-old male mice. Red arrowheads indicate osteoblasts located on the cancellous bone surfaces. Scale bar, 40 μm (f-g) Quantitative data of osteoblast numbers (Ob.N/BPm) and osteoblast surfaces (Ob.S/BS). N = 5 for each group. (h) Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining. Scale bar, 160 μm (i-j) Quantitative data of osteoclast number/bone perimeter (Oc.N/BPm) and osteoclast surface/bone surface (Oc.S/BS). Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

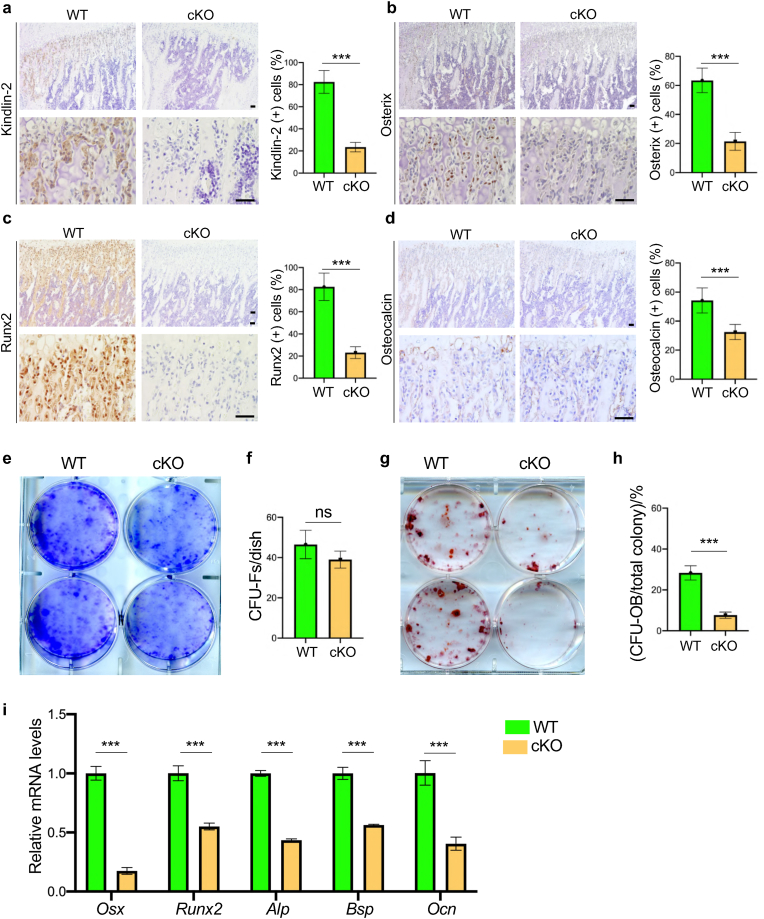

2.5. Deletion of Kindlin-2 inhibits osteoblastic differentiation in vitro and in bone

We performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses of P35 proximal tibiae and found that Kindlin-2 loss significantly down-regulated the protein expression levels of osteoblastic differentiation markers (Osx, Runx2 and Ocn) in tibial trabecular bone of Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre compared with those in control mice (Fig. 5a–d). We next performed a colony forming unit-fibroblast (CFU–F) assay using primary bone marrow cells from P35 Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre and control mice and found that the number of CFU-F colonies was slightly reduced in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre group relative to that in control group (Fig. 5e and f) (39.0 ± 4.2 in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre versus 46.5 ± 7.97 in control, P = 0.1903, Student's t test). We performed a colony forming unit-osteoblast (CFU-OB) assay and observed a markedly reduced number of CFU-OB (osteoprogenitors) in the Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre group compared with that in control group (Fig. 5g and h) (7.67 ± 1.53 in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre versus 28.3 ± 3.51 in control, P = 0.0007, Student's t test). We determined whether Kindlin-2 ablation in Osx-expressing cells impacts the in vitro differentiation capacity of primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) and found that the expressions of osteoblastic differentiation marker genes, including those encoding osterix (Osx), Runx2, alkaline phosphatase (Alp), bone sialoprotein (Bsp) and osteocalcin (Ocn), were all dramatically decreased in the Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre group compared to that in control group (Fig. 5i).

Figure 5.

Kindlin-2 deletion impairs osteoblastic differentiation in vitro and in bone (a-d) Quantitative IHC analyses on expression of Kindlin-2 (a), Osx (b), Runx2 (c) and Ocn (d) in the proximal tibial metaphysis of WT and cKO mice at P35. Higher magnification images are shown in lower panels. Scale bar: 40 μm. N = 6 for each group. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (e-f) Colony forming unit-fibroblast (CFU–F) assays, followed by Giemsa staining (e). The number of CFU-F was counted under a microscope (f). N = 3 mice per group (g-h) Colony forming unit-osteoblast (CFU-OB) assays. The number of CFU-OB was counted under a microscope (h). N = 3 mice per group. (i) In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), followed by real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) analyses of mRNA levels of osteoblastic marker genes, including Osx, Runx2, Alp, Bsp and Ocn. N = 6 for each group. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ns: not significant.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate an essential role of Kindlin-2 in osteoprogenitors in regulation of skeletal development and postnatal bone mass accrual and homeostasis in mice. The findings of our study can be summarized as follows: first, Kindlin-2 is highly expressed in Osx-expressing osteoprogenitors during endochondral ossification; second, conditional deletion of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing osteoprogenitors results in multiple striking skeletal abnormalities during development and leads to severe low-turnover osteopenia in adult mice; third, loss of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing osteoprogenitors impairs both intramembranous and endochondral ossifications in mice; and fourth, Kindlin-2 deficiency markedly damages osteoblastic differentiation capacity of the bone mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) and thereby bone formation. These findings, along with those from our previously established role of Kindlin-2 in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal progenitors and Dmp1-expressing mature osteoblasts and osteocytes, will improve our understanding of the importance of Kinlind-2 expression in osteoblastic lineage cells in control of the differentiation of mesenchymal lineage cells and bone homeostasis.

Our in vitro studies demonstrate that Kindlin-2 loss impairs the osteoblastic differentiation capacity of the bone marrow stromal cells, which may contribute to the osteopenic phenotype in the mutant mice. In addition, our previous study demonstrates that Kindlin-2 regulates Sox9 expression and TGF-β signaling to control chondrocyte differentiation during skeletal development [21]. Because OsxCre is known to be active in pre-hypertrophic chondrocytes [38,39], it is possible that deletion of Kindlin-2 in these cells partially contributes to the observed chondrodysplasia and osteopenia in the mutant mice in this study. The molecular mechanisms through which Kindlin-2 expression in osteoprogenitors regulates skeletal development and bone mass is complex, which require further investigation in great detail in the future.

We previously demonstrate that deletion of Kindlin-2 in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal stem cells cause multiple severe skeletal defects in mice during development (21). It is interesting to compare the phenotypes of mice lacking. Kindlin-2 in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal progenitor cells (Kindlin-2fl/fl; Prx1Cre mice) in our previous study with those in mice with deletion of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing osteoprogenitor cells (Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice) in this study. The overall skeletal defects in the limbs and calvariae displayed by the Kindlin-2fl/fl; Prx1Cre mice were much more severe than those in Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice. In fact, the Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice showed severe forelimb and hindlimb shortening and a complete loss of the skull vault. Furthermore, the Kindlin-2fl/fl; Prx1Cre mice died immediately after birth, while the Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice survived at birth and beyond. These results suggest that Kindlin-2 expression in Prx1-expressing mesenchymal progenitor cells is more critical for skeletal development than its expression in Osx-expressing osteoprogenitor cells.

It is known that low-turnover osteopenia links to multiple disease conditions, such as aging and renal failure [40,41]. It can increase the risk of fracture and lead to a higher mortality in aged population [42]. In this study, we find that loss of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing cells causes severe low-turnover osteopenia in adult mice. Specifically, loss of Kindlin-2 in Osx-expressing cells drastically decreased the bone mass and remodeling activity in mice. Results from bone histomorphometry analyses reveal that the osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption were both decreased by Kindlin-2 loss in Osx-expressing cells. It should be noted that, although haploinsufficiency of Kindlin-2 did not induce obvious skeletal abnormalities during early development, adult Kindlin-2fl/+; OsxCre mice did display remarkable reductions in bone mass and remodeling activity when compared to control mice, suggesting that Kindlin-2 exerts more critical functions in controlling bone mass and remodeling activity through its expression in Osx-expressing cells in adult mice. Interestingly, our previous study has shown that deletion of Kindlin-2 in Dmp1-expressing mature osteoblasts and osteocytes causes decreased bone mass and abnormal bone remodeling by reducing osteoblast but increasing osteoclast formation and function [22]. We further demonstrate that Kindlin-2 in osteocytes can modulate PTH1R signaling and mediate mechanotransduction to regulate bone mass and homeostasis [23,25]. Thus, results from this study and our previous studies provide an integrated view on the roles of Kindlin-2 expression in osteoblastic lineage cells in regulation of bone mass accrual and homeostasis in mice.

We acknowledge that there are limitations in this study. While Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice display significantly decreased thickness in the growth plate at P35, whether this phenotype is due to a direct effect of Kindlin-2 loss in cells of the growth plate or through an indirect effect caused by altered bone microenvironment induced by Kindlin-2 loss remains to be determined. Furthermore, while our results indicate that Kindlin-2 loss significantly inhibits osteoblastic differentiation capacity of BMSCs, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unknown and require further investigation.

In summary, our study demonstrates a critical role of Kinlind-2 expression in osteoprogenitor cells in regulation of skeletal development and postnatal bone mass accrual and homeostasis in mice. We may define a novel therapeutic target for metabolic bone diseases, such as osteoporosis.

Author contributions

Study design: GX and XW. Study conduct and data collection: XW, YL, MQ, WG and GX. Data analysis: XW, YL and GX. Data interpretation: GX and XW. Drafting the manuscript: GX and XW. XW, YL and GX take the responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Core Research Facilities of Southern University of Science and Technology. This work was supported, in part, by the National Key Research and Development Program of China Grants (2019YFA0906004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants (81991513, 81630066, 81870532), and the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Innovation Council Grant (2017B030301018).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2021.08.005.

Animal studies

The generation of Kindlin-2fl/fl mice was previously described [22,23,25]. OsxCre transgenic mice, in which an Osx gene promoter drives Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast progenitors, were previously described [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47]]. Kindlin-2 fl/fl mice were crossed with OsxCre mice and their progeny were crossed with Kindlin-2fl/fl mice to obtain Kindlin-2fl/fl; OsxCre mice. Kindlin-2 fl/fl littermates had no detectable bone phenotypes and served as controls in this study. The animal protocols of this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Southern University of Science and Technology.

Histology, histomorphometry, and immunohistochemistry

Histology, histomorphometry, and immunohistochemistry were performed according to our previously established protocols [48,49]. Briefly, at the time of euthanasia, bone tissues were dissected, fixed, decalcified, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micron sections were used for H&E staining, alcian blue & orange G staining, toluidine blue staining, and TRAP staining as previously described [48). For histomorphometry, parameters such as the Oc.S/BS, Oc.Nb/BPm, Ob.S/BS and Ob.Nb/BPm were measured using Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc.) as we described [48). For immunohistochemistry, 5-mm sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a descending series of ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer (10 mmol L−1, pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with peroxidase-blocking solution (Dako), and protein was blocked with normal horse serum (Vector). The sections were incubated with primary antibodies against Runx2 (ab102711; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), osterix (Osx) (ab22552; Abcam), osteocalcin (Ocn) (sc-30044; Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), Kindlin-2 (MAB2617; Millipore) or control IgG in a slide staining tray at 4 °C overnight and then incubated with horse biotinylated anti-mouse/rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Vector) followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Vector). Immunoreactivity was visualized by the DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence and confocal analyses

Five-mm sections were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies against Osx (ab22552; Abcam) and Kindlin-2 (MAB2617; Millipore) overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the sections were incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies (1:400) for 1 h at room temperature. The fluorescent signals in regions of interest were determined using a confocal microscope (Leica SP8 Confocal Microsystems).

Calcein double labeling

The Calcein double labeling and quantitative measurements of the mineral apposition rate (MAR), mineralizing surface per bone surface (MS/BS), and bone formation rate (BFR) were performed as previously described [25].

Micro-computerized tomography

Micro-computerized tomography (μCT) analyses were performed according to our previously established protocol [22,23,30]. After sacrifice, mouse femurs were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Non-demineralized femurs from each group were scanned and measured by μCT (μCT35, SCANCO Medical AG, Wayne, PA) with an isotropic resolution of 7.0 mm following the standards of techniques and terminology recommended by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. For trabecular bone parameters, transverse slices were obtained in the region of interest in the axial direction from the trabecular bone 0.1 mm below the growth plate (bottom of the primary spongiosa). Contours were defined and drawn close to the cortical bone. The trabecular bone was then removed and analyzed separately. A three-dimensional analysis was performed on 250 trabecular bone slices. A 1.75-mm section was used to obtain mid-femoral cortical bone thickness. The analysis of the specimens involved the following bone measurements: bone volume fraction/total tissue volume (BV/TV, %), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), and cortical thickness (Ct.Th).

Primary BMSC culture and CFU-F and CFU-OB assays

Primary BMSCs were isolated from tibiae and femurs as previously described [22,48]. The CFU-F assay and CFU-OB assay were performed as previously described (22, 48).

In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of BMSCs

For osteoblastic differentiation, BMSCs were cultured in osteoblastic medium (α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 50 μg mL−1 ascorbic acid) followed by qPCR analyses of osteoblastic marker genes (48).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) analyses

RNA isolation, reverse transcription (RT), and qPCR analyses were performed as we previously described (22). The DNA sequences of the mouse primers used for qPCR are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Salhotra A., Shah H.N., Levi B., Longaker M.T. Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:696–711. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00279-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long F. Building strong bones: molecular regulation of the osteoblast lineage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrm3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berendsen A.D., Olsen B.R. Bone development. Bone. 2015;80:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackie E.J., Ahmed Y.A., Tatarczuch L., Chen K.S., Mirams M. Endochondral ossification: how cartilage is converted into bone in the developing skeleton. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:46–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolian C. Vol. 9. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol; 2020. Endochondral ossification and the evolution of limb proportions; p. e373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadjidakis D.J. Androulakis, II, bone remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1092:385–396. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crane J.L., Cao X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and TGF-beta signaling in bone remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:466–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI70050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eastell R., Szulc P. Use of bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2017;5:908–923. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L., Heckmann B.L., Yang X., Long H. Osteoblast autophagy in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:3207–3215. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adami G., Saag K.G. Osteoporosis pathophysiology, epidemiology, and screening in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21:34. doi: 10.1007/s11926-019-0836-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appelman-Dijkstra N.M., Papapoulos S.E. Paget's disease of bone. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2018;32:657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rognoni E., Ruppert R., Fassler R. The kindlin family: functions, signaling properties and implications for human disease. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:17–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.161190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderwood D.A., Campbell I.D., Critchley D.R. Talins and kindlins: partners in integrin-mediated adhesion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:503–517. doi: 10.1038/nrm3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottcher R.T., Veelders M., Rombaut P., Faix J., Theodosiou M., Stradal T.E., et al. Kindlin-2 recruits paxillin and Arp2/3 to promote membrane protrusions during initial cell spreading. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:3785–3798. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201701176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei X., Wang X., Zhan J., Chen Y., Fang W., Zhang L., et al. Smurf1 inhibits integrin activation by controlling Kindlin-2 ubiquitination and degradation. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:1455–1471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201609073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H., Deng Y., Sun K., Yang H., Liu J., Wang M., et al. Structural basis of kindlin-mediated integrin recognition and activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:9349–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703064114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirbawi J., Bialkowska K., Bledzka K.M., Liu J., Fukuda K., Qin J., et al. The extreme C-terminal region of kindlin-2 is critical to its regulation of integrin activation. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:14258–14269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.776195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jobard F., Bouadjar B., Caux F., Hadj-Rabia S., Has C., Matsuda F., et al. Identification of mutations in a new gene encoding a FERM family protein with a pleckstrin homology domain in Kindler syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:925–935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svensson L., Howarth K., McDowall A., Patzak I., Evans R., Ussar S., et al. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency-III is caused by mutations in KINDLIN3 affecting integrin activation. Nat Med. 2009;15:306–312. doi: 10.1038/nm.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montanez E., Ussar S., Schifferer M., Bösl M., Zent R., Moser M., et al. Kindlin-2 controls bidirectional signaling of integrins. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1325–1330. doi: 10.1101/gad.469408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C., Jiao H., Lai Y., Zheng W., Chen K., Qu H., et al. Kindlin-2 controls TGF-beta signalling and Sox9 expression to regulate chondrogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7531. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cao H., Yan Y., Wang D., Lai Y., Zhou B., Zhang Q., et al. Focal adhesion protein Kindlin-2 regulates bone homeostasis in mice. Bone Res. 2020;8:2. doi: 10.1038/s41413-019-0073-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu X., Zhou B., Yan Q., Tao C., Qin L., Wu X., et al. Kindlin-2 regulates skeletal homeostasis by modulating PTH1R in mice. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:297. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin L., Liu W., Cao H., Xiao G. Molecular mechanosensors in osteocytes. Bone Res. 2020;8:23. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin L., Fu X., Ma J., Lin M., Zhang P., Wang Y., et al. Kindlin-2 mediates mechanotransduction in bone by regulating expression of Sclerostin in osteocytes. Commun Biol. 2021;4:402. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01950-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei X., Xia Y., Li F., Tang Y., Nie J., Liu Y., et al. J Am Soc Nephrol; 2013. Kindlin-2 mediates activation of TGF-beta/smad signaling and renal fibrosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun Y., Guo C., Ma P., Lai Y., Yang F., Cai J., et al. Kindlin-2 association with rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor alpha suppresses Rac1 activation and podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3545–3562. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z., Mu Y., Veevers J., Peter A.K., Manso A.M., Bradford W.H., et al. Vol. 9. Circ Heart Fail; 2016. Postnatal loss of kindlin-2 leads to progressive heart failure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu K., Lai Y., Cao H., Bai X., Liu C., Yan Q., et al. Kindlin-2 modulates MafA and beta-catenin expression to regulate beta-cell function and mass in mice. Nat Commun. 2020;11:484. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao H., Gao Y., Yan Q., Yang W., Li R., Lin S., et al. Lipoatrophy and metabolic disturbance in mice with adipose-specific deletion of kindlin-2. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.128405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruiz-Ojeda F.J., Wang J., Bäcker T., Krueger M., Zamani S., Rosowski S., et al. Active integrins regulate white adipose tissue insulin sensitivity and brown fat thermogenesis. Mol Metab. 2021;45:101147. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi L., Chi X., Zhang X., Feng X., Chu W., Zhang S., et al. Kindlin-2 suppresses transcription factor GATA4 through interaction with SUV39H1 to attenuate hypertrophy. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:890. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2121-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z., Mu Y., Zhang J., Zhou Y., Cattaneo P., Veevers J., et al. Kindlin-2 is essential for preserving integrity of the developing heart and preventing ventricular rupture. Circulation. 2019;139:1554–1556. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He X., Song J., Cai Z., Chi X., Wang Z., Yang D., et al. Kindlin-2 deficiency induces fatal intestinal obstruction in mice. Theranostics. 2020;10:6182–6200. doi: 10.7150/thno.46553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi X., Luo W., Song J., Li B., Su T., Yu M., et al. Kindlin-2 in Sertoli cells is essential for testis development and male fertility in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:604. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03885-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang H., Wang C., Long Q., Zhang Y., Wang M., Liu J., et al. Kindlin2 regulates neural crest specification via integrin-independent regulation of the FGF signaling pathway. Development. 2021;148 doi: 10.1242/dev.199441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo L., Cai T., Chen K., Wang R., Wang J., Cui C., et al. Kindlin-2 regulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation through control of YAP1/TAZ. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:1431–1451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing W., Godwin C., Pourteymoor S., Mohan S. Conditional disruption of the osterix gene in chondrocytes during early postnatal growth impairs secondary ossification in the mouse tibial epiphysis. Bone Res. 2019;7:24. doi: 10.1038/s41413-019-0064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jing J., Hinton R.J., Jing Y., Liu Y., Zhou X., Feng J.Q., et al. Osterix couples chondrogenesis and osteogenesis in post-natal condylar growth. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1014–1021. doi: 10.1177/0022034514549379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oda Y., Sasaki T., Miura H., Takanashi T., Furuya Y., Yoshinari M., et al. Bone marrow stromal cells from low-turnover osteoporotic mouse model are less sensitive to the osteogenic effects of fluvastatin. PloS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marie Madeleine C., D'haese Patrick C., Verschoren Wim J., Behets Geert J., Schrooten Iris, Marc E., et al. Low bone turnover in patients with renal failure. Renal bone disease. 1999;56:70–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.07308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demontiero O., Vidal C., Duque G. Aging and bone loss: new insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012;4:61–76. doi: 10.1177/1759720X11430858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu W.X., Ma X., Lin X., Zhao F., Li D., Chen Z., et al. Deficiency of Macf1 in osterix expressing cells decreases bone formation by Bmp2/Smad/Runx2 pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:317–327. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang J., Xie J., Chen W., Tang C., Wu J., Wang Y., et al. Runt-related transcription factor 1 is required for murine osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:11669–11681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duan X., Murata Y., Liu Y., Nicolae C., Olsen B.R., Berendsen A.D., et al. Vegfa regulates perichondrial vascularity and osteoblast differentiation in bone development. Development. 2015;142:1984–1991. doi: 10.1242/dev.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abou-Ezzi G., Supakorndej T., Zhang J., Anthony B., Krambs J., Celik H., et al. TGF-beta signaling plays an essential role in the lineage specification of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in fetal bone marrow. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan S.H., Senarath-Yapa K., Chung M.T., Longaker M.T., Wu J.Y., Nusse R., et al. Wnts produced by Osterix-expressing osteolineage cells regulate their proliferation and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E5262–E5271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420463111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lei Y., Fu X., Li P., Lin S., Yan Q., Lai Y., et al. LIM domain proteins Pinch1/2 regulate chondrogenesis and bone mass in mice. Bone Res. 2020;8:37. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-00108-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu K., Yi J., Xiao Y., Lai Y, Song P., Zheng W., et al. Impaired bone homeostasis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice with muscle atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:8081–8094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.