Summary

Statins are among the most commonly prescribed drugs, and around every fourth person above the age of 40 is on statin medication. Therefore, it is of utmost clinical importance to understand the effect of statins on cancer cell plasticity and its consequences to not only patients with cancer but also patients who are on statins. Here, we find that statins induce a partial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype in cancer cells of solid tumors. Using a comprehensive STRING network analysis of transcriptome, proteome, and phosphoproteome data combined with multiple mechanistic in vitro and functional in vivo analyses, we demonstrate that statins reduce cellular plasticity by enforcing a mesenchymal-like cell state that increases metastatic seeding ability on one side but reduces the formation of (secondary) tumors on the other due to heterogeneous treatment responses. Taken together, we provide a thorough mechanistic overview of the consequences of statin use for each step of cancer development, progression, and metastasis.

Keywords: statins, cellular plasticity, cholesterol pathway, mesenchymal cell state shift, barcode screening

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Statins induce a partial EMT phenotype in PDAC, lung cancer, and colon cancer

-

•

Partial EMT and reduced cellular plasticity can drive apoptosis or block MET

-

•

Cancer cells overcome statin-induced apoptosis by activating ERK

-

•

Statins increase metastatic seeding but reduce tumor formation and metastatic growth

Dorsch et al. identify statins as potent modulators of cancer cell plasticity and demonstrate that cholesterol pathway inhibition induces a mesenchymal cell shift in cancer cells. They show that statin-induced EMT promotes metastatic seeding on one hand but unexpectedly counteracts tumor and metastasis formation on the other hand.

Introduction

Molecular and phenotypic changes in tumor cells are collectively referred to as cellular plasticity. Cellular plasticity is a common requirement for cancer cells to progress, adapt into different subtypes, respond to treatment, and gain metastatic ability. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is one of the best-described programs of cellular plasticity and considered a crucial step to enhance tumor progression and to initiate the metastatic process (Yuan et al., 2019). Post-initiation, metastatic cells require a dynamic and critical reversal in cellular phenotype (mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition [MET]), enabling the colonization of distant organs. These dynamic processes are termed epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP), an ability that is essential for metastases but that also affects cancer initiation, progression, and therapy responses (Gupta et al., 2019). EMP is not a single-cell state with binary readout, defined by either epithelial or mesenchymal cell markers (Williams et al., 2019; Karacosta et al., 2019), but rather comprises a combination of cell states that display partial EMT phenotypes with both epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics (Gupta et al., 2019; Karacosta et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2019). This plastic cellular state of cancer cells contributes to the challenge of not only identifying effective therapies and fully comprehending the underlying mechanisms of cancer progression and metastasis but also understanding the full impact of (targeted) anti-cancer therapies and other medications on cancer patients.

Metastasis is a complex multistep process that requires high cellular plasticity (Steeg, 2006; Massagué and Obenauf, 2016; Fares et al., 2020). It is highly likely that commonly used medications might impact the behavior of (metastatic) cancer cells due to the cancer cells’ high non-genetic cellular plasticity (Yuan et al., 2019). To identify drugs that could impact cellular plasticity, we adapted a previously established multiplexed small-molecule screening platform to enable high-throughput, unbiased, and quantitative identification of regulators of metastatic seeding of cancer cells in vivo (Grüner et al., 2016). From a library of 624 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved inhibitors, we identified statins as a drug class that significantly inhibits the metastatic ability of pancreatic cancer (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [PDAC]) cells in vitro and in vivo. We find that although statin treatment initially enhances the ability of cancer cells to migrate and resist anoikis resulting in increased metastatic seeding, these cells are then unable to revert to a more epithelial-like cell state that leads to decreased secondary tumor or metastasis formation. Thus, the enforced induction of EMT by statins has distinct effects on cancer cells at different stages of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis, a finding that clinicians need to consider when prescribing statins to their (cancer) patients.

Results

Multiplexed in vivo screening identifies statins as potential regulators of metastasis

To analyze the impact of drugs already in clinical use on cancer cell plasticity, we used an in vivo multiplexed small-molecule screening platform to quantify the impact of FDA-approved drugs on metastatic seeding (Grüner et al., 2016). In this approach, uniquely barcoded variants of a murine metastatic pancreatic cancer cell line are treated individually with drugs for ∼40 h followed by pooling and intravenous transplantation into syngeneic recipient mice (Figure S1A; Grüner et al., 2016). Barcode sequencing of the pre-injection pool and cancer cells in the lungs 2 days after injection can uncover drugs that impact metastatic seeding ability. In total, we screened 624 compounds and uncovered 39 hits (6.25% hit rate) that significantly lowered the incidence of metastatic seeding in the lungs of syngeneic recipient mice (Figure 1A; Table S1). To differentiate specific effects on metastatic seeding from general toxicity, we performed in vitro viability assays and calculated the relative “metastatic selectivity” for each compound defined as the ratio of reduced metastatic ability in vivo to the overall loss of viability in vitro (Figure 1B; Table S1; STAR Methods; Grüner et al., 2016). Based on metastatic selectivity, compound class diversity, and compounds with known molecular targets, we chose 14 top candidates for a secondary dose-response validation screen (Figures S1B and S1C). Fluvastatin emerged as one of the top validated hits, demonstrating an inhibition of metastatic seeding ability in a dose-dependent manner in vivo without general toxicity (Figures 1C and S1D).

Figure 1.

Multiplexed in vivo screening reveals fluvastatin as an inhibitor of PDAC metastasis in vivo

(A) Screening of 624 FDA-approved drugs distributed across 8 96-well plates. Each black dot represents one compound. The red line indicates a 20% loss of metastatic ability.

(B) Metastatic selectivity of the FDA-approved drugs within the initial screen.

(C) Dose-dependent effect of fluvastatin on metastatic ability of 0688M cells after 72 h of pretreatment.

(D) Schematic of the in vivo metastasis model.

(E) Tumor volume of subcutaneous tumors in mice treated as depicted in (D); n = 7 mice per group, symbols indicate the mean, error bars indicate ± SEM.

(F) Representative fluorescent image of the five lung lobes of mice treated as depicted in (D); scale bars: 1,000 μm.

(G) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for GFP in the lungs of recipient mice; scale bars: 100 μm.

(H) Quantification of GFP+ cancer cells in metastases by flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]); data are from two independent experiments normalized to control group; each dot represents a mouse, the black line is the mean; n = 10–11 mice per group.

Our screening method identifies drugs that impact the earlier stages of metastasis, including survival in circulation as well as adhesion and extravasation at a secondary site (Grüner et al., 2016). To validate the effects of fluvastatin in a model that recapitulates the entire metastatic cascade, mice with established tumors from human ASPC1 cells were treated with fluvastatin or vehicle once the volume of primary tumors exceeded 100 mm3, which is at the onset of metastases in this model (Figure 1D; Grüner et al., 2016). Subcutaneous tumor growth was not significantly different between the fluvastatin-treated and control mice. Even though previous studies suggested otherwise (Gbelcová et al., 2008), proliferation in primary subcutaneous tumors was similar in treated and control animals (Figures 1E, S1E, and S1F). Fluvastatin treatment reduced metastases to the lungs >2-fold, as shown by fluorescence microscopy, GFP immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry analysis of dissociated lung lobes (Figures 1F–1H). Thus, fluvastatin reduced pancreatic cancer metastases in vivo without influencing primary tumor growth.

Statin treatment induces a mesenchymal cell morphology in pancreas, lung, and colon cancer cells

To uncover the impact of statins on cells growing in vitro in 2D and 3D, three human PDAC cell lines with different morphologies were subjected to fluvastatin treatment. Fluvastatin induced cellular morphology changes reminiscent of EMT, albeit with partially distinct effects across cell lines (Figures 2A, S2A, and S2B). In addition, fluvastatin treatment of PDAC cells grown in 3D resulted in the loss of sphere-forming ability and loosened cell contacts, accompanied by a substantial increase in sphere area due to increased distance between individual cells (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

Cholesterol pathway inhibition induces a shift in cellular morphology

(A) YAPC cells in two-dimensional (2D) cell culture after 48 h of treatment as indicated.

(B–E) Sphere formation (B and D) and sphere area quantification (C and E) of YAPC cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated.

(F and G) Sphere formation (F) and sphere area quantification (G) of H1975 cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated.

(H) Sphere formation for 7 days of YAPC cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated.

(I) Sphere formation of YAPC cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated; then the medium was changed and indicated drugs were added for the indicated times.

Scale bars: 75 μm (top panel), 20 μm (bottom panel); yellow boxes: area chosen for magnification below; one representative out of three independent experiments is depicted; bar graphs indicate the mean; error bars indicate ± SEM. Significance test: one-way ANOVA. See also Figure S2.

Statins inhibit the rate limiting step of the intracellular cholesterol synthesis by blocking the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (CoA)reductase (HMGCR) and thus the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonic acid (MVA) (Brown and Goldstein, 1980). Importantly, the phenotypic changes observed in 2D and 3D were reverted upon addition of MVA (Figures 2A–2C, S2A, and S2B), confirming that HMGCR is the target of statins in metastatic PDAC. In addition, lovastatin and cerivastatin treatment recapitulate these effects, which is consistent with a common mode of action for statins (Figures 2D, 2E, and S2C–S2H). Interestingly, statin treatment led to comparable effects on lung cancer and colon cancer cells both in 2D and 3D culture (Figures 2F, 2G, and S2I–S2L). Inhibition of sphere formation and phenotypic changes were strictly dependent on the presence of fluvastatin, as spheres started to rebuild within 7 days upon depletion of fluvastatin (Figure 2H). Similarly, phenotypic changes were reversible upon addition of MVA (Figure 2I, middle and bottom panel; Figure S2M). Of note, addition of fluvastatin to pre-existing spheres had no effect on 3D sphere architecture (Figure 2I, top panel). Importantly, fluvastatin treatment did not affect cell growth, indicating that the phenotypic effects were not due to differences in cell viability or proliferation (Figures S2N–S2P).

Cholesterol pathway inhibition induces profound changes in signaling networks

To uncover the underlying molecular mechanisms that drive the dramatic statin-mediated switch in cell morphology, we performed independent microarray, total proteome, and phosphoproteome analyses of ASPC1 cells treated with fluvastatin or vehicle. Genes and proteins that were upregulated 1.5-fold between treatment and control groups were subjected to STRING (search tool for recurring instances of neighbouring genes) analysis for network visualization. To expand the STRING networks and improve significant clustering, we added the significantly (p < 0.05) upregulated phosphorylated proteins after both 48 h and 15 min of fluvastatin treatment. A strict confidence interval of 0.9 was set to display only strong protein interactions. Overall, results of microarray, proteome, and phosphorylated proteome analyses were highly consistent, with many proteins being significantly upregulated in at least two independent datasets (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Statin treatment inhibits de novo cholesterol synthesis and affects essential signaling pathways and cellular programs

(A) STRING analysis of ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h. Cells were subjected to microarray analysis, total proteome analysis, and phosphoproteome analysis after 48 h of treatment as well as phosphoproteome analysis after 15 min of treatment each in independently performed experiments.

(B) GSEA for cholesterol homeostasis of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(C) qRT-PCR of HMGCR expression in ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin, 0.5 mM MVA, or control, alone or in combination for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of one representative out of three independent experiments. Significance test: one-way ANOVA.

(D) Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis for total cholesterol levels in ASPC1 cells treated as indicated in (C) for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(E) MS analysis for de novo cholesterol synthesis with 13C-labeled glucose of ASPC1 cells treated as indicated for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(F) GSEA for apoptosis gene set of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin or control.

(G–I) Annexin V analysis of indicated cells after indicated treatment for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significance test: unpaired t test.

(J) GSEA for Kras signaling on microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(K) Western blot for pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK after indicated treatment for 48 h.

(L and N) Annexin V analysis after indicated treatment for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significance test: one-way ANOVA.

(M, O) Western blot for pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK after indicated treatment for 48 h.

One of the main functional protein clusters that were upregulated by fluvastatin treatment included members of the cholesterol metabolism protein family (Figure 3A). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the microarray data confirmed an upregulation of the cholesterol homeostasis signaling pathway in statin-treated cells (Figure 3B; Table S2). Additionally, qPCR analysis of cancer cells treated with fluvastatin or cerivastatin confirmed that statins increase the expression of HMGCR, consistent with published observations (Gbelcová et al., 2017b). HMGCR induction could be reverted upon addition of MVA (Figures 3C, S3A, and S3B). Furthermore, Acyl-CoA Synthetase Short Chain Family Member 2 (ACSS2) that catalyzes the activation of acetate for use in lipid synthesis and energy generation (Schug et al., 2015) was highly upregulated at both the mRNA and protein level and was phosphorylated upon statin treatment (Figure 3A). We hypothesized that HMGCR and ACSS2 upregulation might counteract statin-mediated inhibition of intracellular de novo cholesterol synthesis, which was also supported by data in a breast cancer trial that discovered an upregulation of HMGCR upon statin treatment (Bjarnadottir et al., 2013).

To analyze the cholesterol levels in pancreatic cancer cells, we performed mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of ASPC1 cells treated with fluvastatin or vehicle. Interestingly, total cholesterol levels were unchanged in statin-treated cancer cells (Figure 3D). However, 13C-labeling of cells treated with fluvastatin, MVA, fluvastatin plus MVA, or control demonstrated that fluvastatin indeed inhibited de novo cholesterol synthesis. As expected, supplementing MVA reduced 13C-glucose incorporation into cholesterol, as it provided a second unlabeled carbon source. Simultaneous addition of MVA and fluvastatin also inhibited de novo cholesterol synthesis, demonstrating that the concentration of fluvastatin was still able to inhibit HMGCR, despite increased expression levels (Figure 3E). Thus, the statin-mediated phenotypic changes in cancer cells are not due to inhibition of HMGCR itself or low cellular cholesterol levels but rather due to the general MVA depletion downstream of HMGCR in the cancer cells and therefore inhibition of de novo cholesterol biosynthesis. It is possible that the distribution of membrane cellular cholesterol could be altered upon statin treatment, thereby influencing cellular signaling (Zhang et al., 2019a; Luu et al., 2013). This idea is corroborated by the fact that statin treatment also upregulated the expression of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor, as well as of many proteins involved in vesicular transport, which allows cells to increase the transport of extracellular cholesterol into the cells (Figure 3A; Greenwood et al., 2006).

ERK activation counteracts statin-induced apoptosis

In addition to cholesterol biosynthesis, GSEA of fluvastatin-treated cells identified a significant upregulation of genes involved in apoptosis, as described previously (Hoque et al., 2008; Alizadeh et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2001; Figure 3F). Functional analyses revealed cell-line-specific anti-apoptotic responses upon fluvastatin treatment (Figures 3G–3I and S3C–S3H), rendering it unlikely that decreased metastasis formation in vivo could be solely attributed to apoptotic programs induced by fluvastatin. Instead, as also suggested by STRING and GSEA analyses and confirmed by western blotting, genes involved in KRAS signaling and ERK activation were increased upon fluvastatin treatment in ASPC1 and Panc89 cells (Figures 3J and 3K). Interestingly, a lack of ERK activation corresponded with high levels of apoptosis induction in YAPC cells. Correspondingly, a combination treatment with both the MEK inhibitor trametinib and statin further increased the apoptosis-inducing effect of trametinib treatment alone in ASPC1 cells (Figures 3L and 3M). In YAPC cells, where ERK was not activated upon statin treatment, trametinib treatment had no additional effect on apoptosis levels compared to statin treatment alone (Figures 3N and 3O). Thus, activation of ERK signaling could also counteract the induction of apoptosis upon statin treatment and seems to be cell line dependent.

Cholesterol pathway inhibition induces an EMT-like cell state

Changes in cellular morphology are typically accompanied by cytoskeletal alterations (Wickstead and Gull, 2011). Indeed, the STRING analysis identified multiple components of the cytoskeleton and Rho protein signaling that were upregulated upon cholesterol pathway inhibition (Figure 3A). Also, the scaffolding protein Intersectin 1 (ITSN1) was upregulated at both the mRNA and protein level and was phosphorylated upon statin treatment (Figure 3A). ITSN1 is known to regulate vesicular transport (O’Bryan, 2010). In addition, ITSN1 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the Rho GTPase family protein Cdc42 and is therefore directly involved in signaling pathways that control the actin cytoskeleton (O’Bryan, 2010). The STRING analysis pointed to ITSN1 as a major transmitter of the signaling between cholesterol homeostasis and cytoskeletal morphology affected by statin treatment (Figure 3A). GSEA analysis revealed an upregulation of genes involved in actin cytoskeleton reorganization (Figure 4A). In agreement with this, F-Actin staining of ASPC1, YAPC, and Panc89 cells revealed marked cytoskeletal rearrangements upon statin treatment. In particular, a substantial subset of statin-treated ASPC1 cells formed flat actin protrusions and lost their peripheral actin ring (Figures 4B and S4A). Furthermore, statin treatment of Panc89 cells led to a loss of actin filaments, and they were reminiscent of contractile stress fibers. YAPC cells generated pronounced peripheral actin bundles upon statin exposure, adopting the mesenchymal phenotype of untreated ASPC1 cells (Figure S4A).

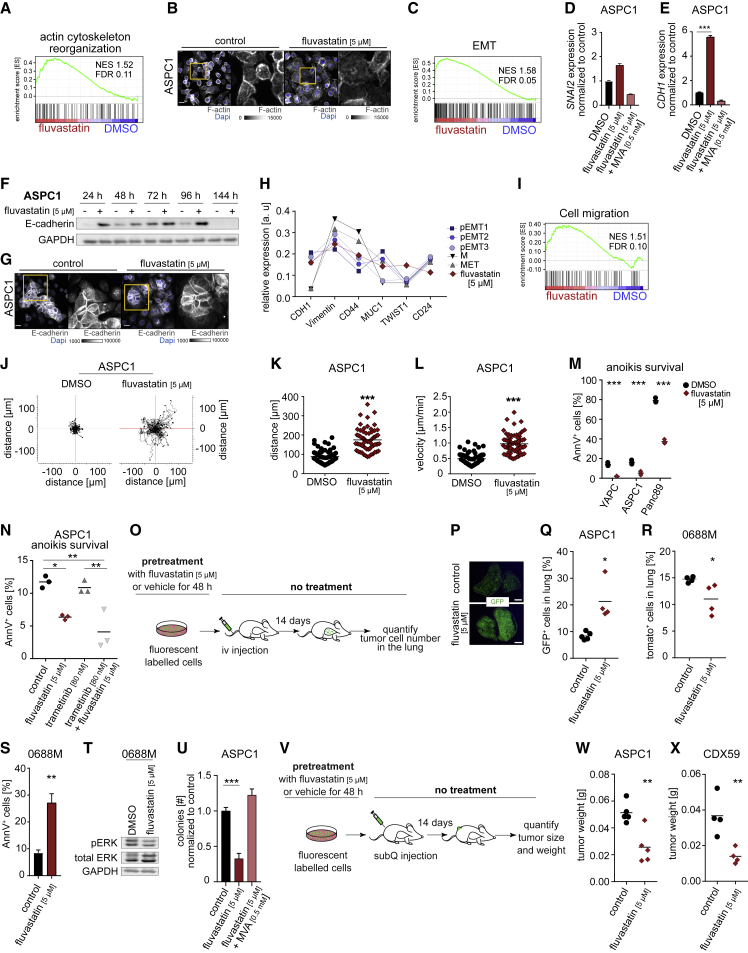

Figure 4.

Cholesterol pathway inhibition induces a partial EMT-like cell state and thereby inhibits tumor formation in vivo

(A) GSEA for actin cytoskeleton organization of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(B) Representative confocal maximum projection and magnification (yellow boxes) of ASPC1 cells treated as indicated for 48 h; staining for rhodamine-phalloidin and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole); scale bar: 20 μm.

(C) GSEA for EMT of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(D and E) qRT-PCR of SNAI2 (D) and CDH1 (E) expression in ASPC1 cells treated as indicated for 48 h; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of one representative out of three independent experiments. Significance test: one-way ANOVA.

(F) Western bot for E-cadherin in ASPC1 cells treated as indicated.

(G) Representative confocal sum projection and magnification (yellow boxes) of ASPC1 cells treated as indicated for 48 h. Cells were immunostained for E-cadherin and DAPI; scale bars: 20 μm.

(H) Projected cell states of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated as indicated for 48 h compared to bioinformatic analysis of Karacosta et al. (2019).

(I) GSEA for cell migration of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(J–L) Live-cell phase contrast imaging of ASPC1 cells. Quantification of migration velocity (μm/min) (L) and accumulated distance (μm) (K) from manual tracking shown in (J); n = 59–61 cells. Significance test: unpaired t test.

(M) Anoikis survival assay after 24 h with 48 h pretreatment as indicated from one representative out of three independent experiments; significance test: two-way ANOVA.

(N) Anoikis survival assay after 24 h with 48 h pretreatment as indicated from one representative out of three independent experiments; significance test:one-way ANOVA.

(O) Schematic of the in vivo experimental setup for intravenous injection to ascertain survival in the blood stream.

(P) Representative fluorescent image of lung lobes of mice intravenously injected with ASPC1-GFP cells pretreated as depicted in (O); scale bars: 1,000 μm.

(Q and R) Number of cells in the lungs of mice intravenously injected and pretreated as depicted in (O); quantified by FACS as [%] of total lung cells; each dot represents a mouse, and the black line is the mean; n = 4–5 mice per group. Significance test: Mann-Whitney test.

(S) Annexin V analysis of 0688M cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significance test: unpaired t test.

(T) Western blot for pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK in 0688M cells treated as indicated for 48 h.

(U) Colony formation assay of ASPC1 cells pretreated for 48 h and with constant treatment during colony formation; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significance test: Mann-Whitney test.

(V) Schematic of the in vivo experimental setup for subcutaneous injection to ascertain tumor formation.

(W and X) Tumor weight of subcutaneous tumors in mice injected with cells pretreated as depicted in (V); each dot represents a mouse, and the black line is the mean; n = 4–5 mice per group. Significance test: Mann-Whitney test.

See also Figures S4–S6.

GSEA analysis suggested a statin-induced upregulation of EMT genes (Figure 4C), exemplified by the MVA-reversible induction of the mesenchymal transcription factor SLUG, as confirmed by qPCR (Figures 4D and S4B). Surprisingly, fluvastatin and cerivastatin induced the expression of E-cadherin at the mRNA and protein level, which again could be reverted upon addition of MVA (Figures 4E, S4C, and S4D). E-cadherin expression increased 48 to 96 h after treatment with fluvastatin (Figures 4F and S4E). Also, E-cadherin upregulation required continuous exposure to drug (Figure S4F). Interestingly, immunostaining for E-cadherin in statin-treated cells did not indicate a change in the membrane localization of E-cadherin per se, albeit the number of cells with functional cell-cell contacts was significantly reduced (Figures 4G and S4G). These data indicate that although E-cadherin expression is upregulated upon statin treatment, it does not result in a more epithelial-like phenotype with increased cellular contacts but rather has the opposite effect.

Recent studies have suggested a more dynamic definition of epithelial and mesenchymal cell states and a corresponding expression of markers (Williams et al., 2019; Padmanaban et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2019; Karacosta et al., 2019). We investigated whether our datasets could be used to identify the statin-induced cell state within this context. We compared the relative expression of EMT markers within our microarray data and generated relative expression curves representing the defined EMT states. Indeed, when comparing the expression of the 6 analyzed EMT markers (CDH1, Vimentin, CD44, MUC1, TWIST1, and CD24) between ASPC1 cells treated with fluvastatin and control, we confirmed an increased expression of the mesenchymal markers Vimentin, CD44, and TWIST1 but also of the epithelial marker CDH1 in fluvastatin-treated cells (Figure S4H). Indeed, statin-treated ASPC1 cells are in a state most comparable to a partial EMT state (Figures 4H and S4I). Furthermore, even though E-cadherin expression is upregulated in statin-treated cells, its relative expression in comparison to the other EMT markers fits these trajectories very well, further indicating that the increase in E-cadherin expression is not controversial to the observed EMT-like cell shift. It has previously been shown that the loss of E-cadherin expression as a marker of metastatic cells is an oversimplification, and many metastases still contain high levels of E-cadherin. Also, epithelial cells expressing E-cadherin can become invasive and metastasize without undergoing a full EMT in cancers (Bukholm et al., 2000; Hollestelle et al., 2013). It is unknown to which extent the statin-mediated upregulation of E-cadherin observed in our study serves to further promote or counteract the functional EMT-like switch in cell state.

Statins have a dual effect on metastatic ability and apoptosis

To determine whether there are additional functional consequences of the statin-mediated mesenchymal shift in cell state, we performed kinetic live-cell imaging to observe cellular migratory capacity in statin- or vehicle-treated cells. Statin-treated cells exhibited an enhanced migratory capacity, with a significantly higher velocity and accumulated distance, accompanied by an upregulation of genes involved in migration (Figures 4I–4L and S5A–S5C). In addition, statin treatment actually increased resistance to anoikis (Figure 4M), a feature of mesenchymal cells enabling them to overcome the loss of cellular contacts (Simpson et al., 2008). Interestingly, the magnitude of anoikis resistance was again directly correlated with the magnitude of ERK activation and lack of apoptosis induction in the different cell lines (Figures 3G–3K). Additional ERK inhibition with the MEK inhibitor trametinib could not counteract the statin-induced resistance to anoikis (Figure 4N), indicating an exclusive effect of ERK-activation on escaping the induction of apoptosis. Survival in the bloodstream, which is a requirement for hematogenic spread (Piskounova et al., 2015; Elia et al., 2018), is characterized by resistance to anoikis and oxidative stress and is typically associated with a mesenchymal-like phenotype (Massagué and Obenauf, 2016; Steeg, 2006; Fares et al., 2020). To link our in vitro results on fluvastatin-induced cell motility to metastatic ability, GFP-labeled ASPC1 cells or YAPC cells were pretreated with fluvastatin or vehicle for 48 h and injected intravenously into recipient mice to evaluate the effects of statin treatment on survival in the bloodstream and ability to seed metastases in the lung (Figure 4O). In this model, cells have to stay alive in the bloodstream and resist oxidative stress and anoikis induction for several days before they enter the lung parenchyma and start to form secondary tumors, as was determined previously (Grüner et al., 2016). Pretreatment with fluvastatin increased the number of ASPC1 cells in the lungs after 14 days, and a similar effect was observed in YAPC cells (Figures 4P, 4Q, and S5D). To examine whether metastatic seeding ability correlates with apoptosis levels, we used mouse 0688M cells used in the initial screen and H1975 lung cancer cells, of which both present a high apoptotic rate and no increase in ERK activation upon fluvastatin treatment. Indeed, 0688M and H1975 cells showed reduced efficiency in metastatic seeding to the lung when pretreated with fluvastatin (Figures 4R–4T and S5E–S5G).

Cholesterol-pathway inhibition reduces cellular plasticity and inhibits tumor and metastasis formation in vivo

The concept that cancer cells need to undergo EMT in order to metastasize and that mesenchymal cancer cells are more metastatic is broadly known (Massagué and Obenauf, 2016; Steeg, 2006; Fares et al., 2020). However, several studies have shown reduced metastatic ability in cancer cells subjected to statin treatment (Beckwitt et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2017). We confirmed these findings in mice, showing that established tumors develop fewer metastases when the mice are treated with statins (Figures 1F–1H). A closer look at our data points to a resolution of these initially counterintuitive findings. We hypothesized that the statin-induced cellular state leads to a reduction in cellular plasticity that plays a significant role in the metastatic transition of a cancer cell, as the cancer cells need to revert back to an epithelial phenotype once they have reached the secondary site in order to form metastases. Indeed, cancer cells that were treated with statins showed a significant reduction in colony formation, and this effect was even more pronounced when the cells were additionally pretreated with statins before seeding (Figures 4U and S5H–S5M). This result suggests that the reversion back to an epithelial state (including growth in a cellular cluster) (Massagué and Obenauf, 2016; Steeg, 2006; Fares et al., 2020) is suppressed under statin treatment.

To validate that MET is an important step for the successful generation of metastases affected by statin treatment in vivo, we pretreated GFP-labeled cancer cells with fluvastatin to induce a mesenchymal shift and analyzed the tumor-forming ability of cells by measuring the tumor weight and size of subcutaneous tumors after injection (Figure 4V). In this model, cells can directly start tumor formation upon injection, as in contrast to the intravenous injection model, no further barriers for establishing epithelial cell clusters and growth have to be overcome. Subcutaneous tumor size and weight were significantly reduced when ASPC1-GFP, YAPC-GFP, Panc89-GFP, or a PDAC-patient-derived cell line (CDX59-GFP) were pretreated with fluvastatin (Figures 4W, 4X, and S5N–S5S). Neither proliferation nor expression of E-Cadherin or Vimentin were different in the tumors that eventually formed, further emphasizing that only initial tumor formation is inhibited as long as statin-treatment is in effect (Figures S6A–S6D). Tumor growth, once the effect of statin treatment ceases, is not further affected, as also observed on molecular levels in vitro. Here, statin pretreatment and continuous ongoing treatment for 14 days were needed to uphold the effects on cellular signaling (Figures S6E and S6F). The effect on tumor formation could also not be rescued by the addition of Matrigel (Figures S6G and S6H). Thus, statin-mediated inhibition of tumor formation is independent of an apoptotic or proliferative response and Matrigel-mediated extracellular signaling.

Integrin and Rho-GTPase signaling induce statin-mediated reduction in phenotypic plasticity

Next, we investigated which cellular pathways mediate the statin-induced shift in cell state. Previous studies suggested statin-induced effects on metastatic cancer cells are due to an inhibition of prenylation downstream of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway (Alizadeh et al., 2017; Gbelcová et al., 2017a). Yet, even though they induced alteration of cellular morphology comparable to that caused by statins (Figures 5A, S7A, and S7B), neither zoledronic acid, an inhibitor of farnesylpyrophosphate synthase, nor the farnesyl transferase inhibitor tipifarnib, caused increased levels of phosphorylated ERK (Figures 5B and 5C). Furthermore, zoledronic acid or tipifarnib pretreatment did not increase in vivo metastatic seeding ability in ASPC1 or Panc89 cells when tested in our metastatic seeding platform; rather, seeding ability decreased as expected, indicating a distinct mechanism of action and effect on cellular signaling from the statin drug class (Figures S7C and S7D).

Figure 5.

Statin-induced morphodynamic changes are mediated by Rho-GTPases and Integrin signaling

(A) Sphere formation of YAPC cells with 48 h pretreatment as indicated; yellow boxes: area chosen for magnification below. Scale bar: 75 μm (top panel), 20 μm (bottom panel).

(B and C) Western blot for pERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK after treatment as indicated for 48 h.

(D) GSEA for TGF-β signaling of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated with 5 μM fluvastatin or control for 48 h.

(E) Western blot for pSMAD2 (Ser465/467) and total SMAD2 treated as indicated for 48 h.

(F) Top panel: YAPC cells in 2D cell culture after 48 h of treatment as indicated. Middle panel: Sphere formation of YAPC cells with pretreatment for 48 h as indicated; yellow boxes: area chosen for magnification below (bottom panel). Scale bar: 50 μm (top and middle panel) and 20 μm (bottom panel).

(G) GSEA for Integrin-mediated signaling of microarray data from ASPC1 cells treated for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin or control.

(H) Western blot for pSRC (Tyr416), total SRC, and Integrin alpha 2 after treatment as indicated for 48 h.

(I) Number of cells in the lungs of mice intravenously injected with ASPC1-GFP cells pretreated as depicted in (Figure 4O); quantified by FACS as [%] of total lung cells; each dot represents a mouse, and the black line is the mean; n = 5 mice per group. Significance test: Mann-Whitney test.

(J) Tumor weight of subcutaneous tumors in mice injected with ASPC1-GFP cells pretreated as depicted in (Figure 4V); each dot represents a mouse, and the black line is the mean; n = 5 mice per group. Significance test: Mann-Whitney test.

(K–M) Western blot for pSRC (Tyr416), total SRC, Integrin alpha 2, phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), total ERK, E-cadherin, and RhoB in Panc89 cells treated for 48 h as indicated.

(N) Western blot for NSDHL in Panc89 shcontrol, shNSDHL#1, and shNSDHL#2 cells.

(O) qRT-PCR of NSDHL in Panc89 shcontrol, shNSDHL#1, and shNSDHL#2 cells; bar graphs indicate the mean, and error bars indicate ± SEM of one representative out of three independent experiments. Significance test: one-way ANOVA.

(P) Anoikis survival assay of Panc89 shcontrol, shNSDHL#1, and shNSDHL#2 cells after 24 h from one representative out of three independent experiments; significance test: ANOVA.

(Q) Western blot for Integrin alpha 2, pERK (Thr202/Tyr204), total ERK, E-cadherin, and RhoB in Panc89 cells treated for 48 h as indicated and Panc89 shcontrol, shNSDHL#1, and shNSDHL#2 cells.

(R) Western blot for Integrin alpha 2, pERK (Thr202/Tyr204), total ERK, E-cadherin, and RhoB in ASPC1 cells treated for 48 h as indicated.

(S) Schematic of morphological and signaling effects of statin treatment on PDAC cells. Dashed arrows indicate hypothesized; continuous arrows indicate data-based interactions.

See also Figures S7 and S8.

Similarly, GSEA analysis revealed that transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling was upregulated in statin-treated cancer cells, which was accompanied by increased SMAD2 phosphorylation (Figures 5D and 5E). However, treatment with recombinant TGF-β could not recapitulate the statin-induced cellular phenotype in sphere culture or the statin-induced molecular changes in signaling, indicating that TGF-β signaling is a consequence rather than cause of the observed cell state shift (Figures 5F and S7E–S7G).

Of note, GSEA also suggested upregulation of integrin signaling upon statin treatment, which involved Rho proteins, laminins, Integrin alpha 2, and SRC (Figures 3A, 5G, and 5H). SRC activation has already been described to induce various morphodynamic changes by integrin signaling, which reportedly also induces EMT (Huveneers and Danen, 2009; Zhang et al., 2017; Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). Therefore, we determined whether SRC inhibition by dasatinib treatment could revert the fluvastatin-induced phenotypes. Dasatinib treatment only partially rescued the statin-induced changes in 3D sphere culture (Figures S7H and S7I) and upon intravenous or subcutaneous injection in vivo (Figures 5I, 5J, and S7J). Yet, dasatinib treatment was unable to revert statin-induced increases in E-cadherin and Integrin alpha 2, demonstrating that SRC activation might be a consequence of integrin signaling (Figures 5K, 5L, and S7K–S7P). Interestingly, statin-induced ERK and RhoB activation upon combinatorial treatment with dasatinib was cell line dependent (Figures 5L, 5M, and S7M–S7P). These data indicate that the fluvastatin-mediated effect on phenotypic cell state (and consequently tumor formation) is only partially dependent on SRC activation. As dasatinib can have other targets besides SRC (Olivieri and Manzione, 2007), it is possible that they—rather than SRC—might be the mediators of the statin effect. Similarly, as dasatinib only partially affects the in vivo phenotype of statin treatment, it is highly likely that a multilevel response maintains total cholesterol levels after statin-mediated inhibition of de novo cholesterol biosynthesis that in turn results in the mesenchymal phenotype. Indeed, genetic knockdown of NAD (P)-dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like (NSDHL), which is involved in the sterol biosynthesis pathway downstream of HMGCR (Wilcox et al., 2007, Gabitova-Cornell et al., 2020), also partially phenocopies the statin-mediated effect. Morphological changes in NSDHL knockdown cells in 2D and in 3D sphere culture and enhanced anoikis survival capacity display the beginning of a mesenchymal phenotype, which is less prominent than that in statin-treated cells (Figure 5N–5P and S8A–S8E). On a molecular level, NSDHL knockdown results in a slight induction of Integrin alpha 2, E-Cadherin, and RhoB (Figures 5Q and S8F) that was partly cell line dependent. The lesser effect of NSDHL knockdown than statin treatment might be due to a compensatory effect that takes place during the selection process in the knockdown cells that acute pharmacological inhibition does not cause, or it may display the more prominent role of HMGCR as a rate-limiting enzyme during cholesterol biosynthesis.

It was shown previously that ectopic expression of HRAS induced EMT and sensitized cells to statin treatment (Yu et al., 2018). In our study, cells with no change or low levels of pERK after fluvastatin treatment (YAPC, 0688M, and H1975) still upregulated RhoB, E-cadherin, and Integrin alpha 2 (Figures S7K, S7M, S7O, S8G, and S8H). In contrast, in cells that activate ERK upon statin treatment, trametinib treatment could not counteract the activation of RhoB, Integrin alpha 2, and E-cadherin (Figure 5R). This finding is independent of the cell state subtype of the pancreatic cancer cells, as statin treatment induced a mesenchymal morphology shift in the classical PDAC cells (PA-TU-8988S) and demonstrated similar effects on both classical (PA-TU-8988S) and QM (quasi-mesenchymal)/basal cells (PA-TU-8988T) on functional and molecular levels, suggesting a general effect on cellular signaling but inducing morphology changes only in cells that do not yet present with a mesenchymal phenotype (Figures S8I–S8L). This result further endorses the conclusion that the activation of ERK is independent of the induction of the EMT-like phenotype and is a consequence of the cell state change to counteract the induction of apoptosis. The cells’ intrinsic capability to activate ERK determines the treatment outcome. Cells that are unable to undergo statin-induced EMT become apoptotic, a well-known concept in tissue homeostasis, turnover, and EMT-mediated disruption of lineage-specific transcriptional networks (Flusberg and Sorger, 2015; David et al., 2016).

In addition, it is known that unligated integrins on adherent cells can induce apoptosis by recruiting and activating caspase 8 (Zhao et al., 2005; Frisch and Screaton, 2001). Therefore, we speculate that the mesenchymal-like cell state shift, during which cancer cells lose their contacts to each other, is accompanied by the upregulation of several integrins, promoting an apoptotic phenotype. Cells that then have the capacity for ERK activation can counteract this induction of apoptosis but are still trapped in their mesenchymal phenotype.

Taken together, our study demonstrates that the inhibition of the intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis and the multilevel counter mechanisms of the cells to maintain cholesterol levels induce an EMT-like cell state through upregulation of multiple integrins and laminins, likely through activation of ITSN1. Integrins then likely activate Rho-family proteins that in turn can activate SRC and TGF-β signaling to induce and maintain this mesenchymal state, potentially involving positive feedback loops (Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010). As a consequence of this shift in cell state, statin treatment traps cancer cells in a mesenchymal-like state, effectively reducing their cellular plasticity. Once cells enter this mesenchymal-like state, upregulation of ERK activity counteracts apoptotic programs. Although the reduced metastatic ability of statin-treated cells that are unable to activate ERK (i.e., 0688M or H1975) seems readily explainable, cancer cells capable of ERK activation (i.e., ASPC1 or Panc89) have increased metastatic seeding ability driven by enhanced migration, extravasation, and survival in the bloodstream. However, the statin-induced mesenchymal cell state shift renders the cancer cells unable to undergo MET, ultimately inhibiting their cellular plasticity and therefore inhibiting their ability to form metastatic colonies (summarized in Figure 5S).

Discussion

During 2003–2012, the overall use of statins increased from 18% to 26% in adult patients over the age of 40, with upward tendency. Furthermore, the US guidelines regarding cholesterol levels and statin use were updated in 2013, causing an additional increase in statin use (Stone et al., 2014). Cholesterol-lowering medication use increases with age, from 17% of adults aged 40–59 to every 2nd adult above 75, of which more than 90% use statins (Gu et al., 2014). Even though the effect of drugs on other drugs (drug-drug interactions) and also on other diseases besides the one for which they are prescribed (drug-disease interactions) is well acknowledged, the number of studies addressing these interactions is limited (Hanlon et al., 2017; Campen et al., 2017). Therefore, it is of utmost importance to understand the impact of statin medication on cancer patients, not only tumor formation and progression but also on cancer metastasis and treatment response.

The effect of statins as a potential treatment for cancer development, progression, and metastasis has been the subject of many preclinical and clinical studies (Iannelli et al., 2018; Farooqi et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2016). Yet, even for patients who are on statins to treat their hypercholesterolemia, it is important for clinicians to know what this treatment may do to their cancer disease. Here, we show that statin treatment directly induces EMT and thereby reduces cell plasticity. In other studies, statin treatment was suggested to inhibit rather than induce EMT of several different cancer types, which was indicated in part by the upregulation of epithelial markers like E-cadherin (Xie et al., 2016; Kato et al., 2018; Koohestanimobarhan et al., 2018). Importantly, we also observed an upregulation of E-cadherin upon statin treatment. Yet, in our study, this result was accompanied by phenotypic and molecular changes toward a mesenchymal phenotype in which the cancer cells are trapped as long as statins are present, preventing them from undergoing MET transition and metastasis formation. In addition, relative E-cadherin expression levels were still in accordance with a partial EMT state that was previously defined for lung cancer (Karacosta et al., 2019). Whether E-cadherin upregulation is functional or a mechanism to counteract the induced mesenchymal cell shift remains unclear. Similarly, Porter et al. (2019) demonstrated that FOLFIRINOX combination chemotherapy induces a shift of PDAC subtypes toward a more QM/basal state, whereas vitamin D induces distinct transcriptional responses in each subtype that lead to differential responses on tumor progression and metastasis.

Recently, cholesterol pathway inhibition was suggested to induce EMT in primary PDAC tumors, resulting in dedifferentiation to the basal subtype (Gabitova-Cornell et al., 2020). Although a statin-induced mesenchymal phenotype is less favorable for primary PDAC, our study shows that it also prevents PDAC metastasis so long as it can be sustained and the required cellular plasticity to perform MET is inhibited. Thus, the time point of EMT induction during cancer development, progression, and metastasis determines its outcome. Indeed, in the background of the autochthonous KPC model for pancreatic cancer, mice with additional NSDHL deficiency, which causes disrupted cholesterol biosynthesis, live longer and develop less frequent PDAC (Gabitova-Cornell et al., 2020). In line with this finding, knockdown of NSDHL partially phenocopied the effects of statin treatment in our study, indicating similar effects on tumor and metastasis formation. In the study by Gabitova-Cornell et al. (2020), this result was attributed to the induction of apoptosis upon EMT-mediated disruption of lineage-specific transcriptional networks, as was described previously (David et al., 2016). In those mice, PDAC developed only when there was enough oncogenic pressure to increase plasticity. This finding is conceptually similar to the results of our study, in which cancer cells could overcome apoptosis by upregulating ERK signaling. Thus, our findings emphasize that targeted therapies can have opposing effects on primary tumor and metastases formation in comparison to tumor progression, underscoring the importance of proper timing of anti-cancer therapies and the distinct effects that inhibition of plasticity can have on different stages of tumor development and progression. Indeed, our data suggest that the development of resistance or discontinuation of statin treatment in cancer patients could promote PDAC metastasis and emphasize the complexity of cholesterol biology in terms of tumor progression.

Consistent with our findings, several retrospective studies support a positive outcome for cancer patients who take statins to treat their hypercholesterolemia. Several large clinical trials revealed that statin treatment reduces the risk to develop PDAC by up to 30% (Archibugi et al., 2019). Furthermore, statin treatment correlates with a reduced risk of death in resected PDAC patients but not in those with advanced disease (Zhang et al., 2019b; Archibugi et al., 2019; Tamburrino et al., 2020; Abdel-Rahman, 2019; Archibugi et al., 2017; Farooqi et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2015). Interestingly, a recent retrospective analysis of data from over 2,000 PDAC patients revealed that the positive effects of statin treatment on mortality are independent from their effect on cholesterol levels (Huang et al., 2016). In our study, we observed that overall cholesterol levels remain unchanged upon statin treatment. Thus, these clinical data are entirely consistent with our molecular and cellular findings. Although the concentrations used here do not completely correspond with the concentrations generally used for patient treatment—treatment doses of 0.1–1 mg/kg and serum levels of approximately 10 nM (Björkhem-Bergman et al., 2011)—they are in general in concordance with concentrations used in preclinical studies and did not induce any adverse effects (Baek et al., 2017; Beckwitt et al., 2018; Hoque et al., 2008). Noteworthy, statins also affect other cells in the human body, such as immune cells. Baek et al. (2017) could show that cholesterol promotes breast cancer metastasis by its metabolite 27-hydroxycholesterol (27HC) that acts on immune myeloid cells residing at the distal metastatic sites, thus promoting an immune suppressive environment. Another study demonstrated that perturbed cholesterol homeostasis leads to an EMT-like state in breast cancer cells, promoting metastasis by affecting both cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages (Nelson et al., 2013).

Our results suggest that the clinical benefit of statin treatment in early diagnosed or resected cancer patients could be driven by a reduction in the formation of new metastases due to inhibition of MET. In addition, the statin-induced mesenchymal cell state is reversible and persists only as long as statins are present. From a therapeutic standpoint, it is important that chronic statin treatment is generally well-tolerated in patients even at high doses (De Angelis, 2004), even though they can cause myopathy as most common off-target effect due to inhibition of mitochondria complex III by the lactone form of statins (Schirris et al., 2015). In addition, beneficial off-target effects of statins have been described, although the causes are still unclear, including improved endothelial function, increased plaque stability, antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effects, reduced risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease, and reduced ischemic stroke (Murphy et al., 2020). Therefore, this class of drugs is well-suited for continuous therapy, which would be required to block the development of metastases in patients with resected tumors or early metastasis.

Limitations of the study

One limitation of our study is certainly that the exact timing of statin-mediated effects in patients is still not completely clear. Whether or not the exact effects on tumors and metastases are the same at the onset of the disease or with established tumors would need to be determined in controlled prospective clinical studies. In addition, the exact molecular links that connect cholesterol levels and distribution with cellular signaling are yet to be determined.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4370; RRID:AB_2315112 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (137F5) Rabbit mAb antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4695; RRID:AB_390779 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti E-Cadherin (24E10) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3195; RRID:AB_2291471 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2118; RRID:AB_561053 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti phospho-smad2 (Ser465/467) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3108; RRID:AB_490941 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti phospho-Smad2 (Ser465/467)/Smad3 (Ser423/425) (D27F4) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8828; RRID:AB_2631089 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti Smad2 (D43B4) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5339; RRID:AB_10626777 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti Smad2/3 (D7G7) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8685; RRID:AB_10889933 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti phospho-Src Family (Tyr416) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2101; RRID:AB_331697 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti phospho-Src Family (Tyr416) (D49G4) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 6943; RRID:AB_10013641 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti Src (36D10) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2109; RRID:AB_2106059 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti NSDHL | Proteintech | Cat# 15111-1-AP; RRID:AB_2155681 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti Integrin alpha 2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-74466; RRID:AB_1124939 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti Vimentin (D21H3) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5741; RRID:AB_10695459 |

| Monoclonal mouse anti BrdU (bromodeoxyuridine) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555627; RRID:AB_10015222 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Fluvastatin | Abcam | ab120651 |

| Dasatinib | Sigma-Aldrich | SML2589 |

| Tipifarnib | Sigma-Aldrich | SML1668 |

| DMSO | AlliChem | A3672 |

| Mevalonic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 50838 |

| Trametinib | Biomol | GSK-1120212 |

| Cerivastatin | Abcam | ab142853 |

| Lovastatin | Abcam | ab120614 |

| Human TGF-beta 1 Recombinant Protein | Thermo Fisher Scientific | PHG9211 |

| Zoledronic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | SML0223 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Mass spectrometry proteomics data | This paper | PRIDE: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/ Identifier: PXD022345 |

| Microarray data | This paper | NCBI GEO Accession number: GSE161536 |

| Western Blot images | This paper | Mendeley Data: https://doi.org/10.17632/nn38268p22.1 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human ASPC1 cells | ATCC | CRL-1682 |

| Human Panc89 cells | RCB | RCB1021 |

| Human PA-TU-8988T cells | DSMZ | ACC-162 |

| Human PA-TU-8988S cells | DSMZ | ACC-204 |

| Human YAPC cells | DSMZ | ACC-382 |

| Human NCL-H1975 cells | ATCC | CRL-5908 |

| Human HCT116 cells | ATCC | CCL-247 |

| Human HEK293T cells | DSMZ | ACC-305 |

| Mouse 0688M cells | liver metastasis of the autochthonous KrasLSL-G12D/+;Trp53LSL-R172H/+; Rosa26LSL-tdTomato/+;Pdx1-Cre |

Grüner et al., 2016 |

| Human patient-derived CDX59 cells | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Immunocompetent 129/Bl6 F1 mice | The Jackson Laboratory via Charles River | Cross of #002448 and #000664 |

| Immunodeficient NOD/Scid/ᵧC (NSG) mice | The Jackson Laboratory via Charles River | #005557 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| qPCR Primers, see STAR Methods section | Eurofins | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| shRNA against NSDHL, shNSDHL#1 | MISSION® shRNA plasmids, Merck | TRCN0000335871 |

| shRNA against NSDHL, shNSDHL#2 | MISSION® shRNA plasmids, Merck | TRCN0000335951 |

| shRNA against NSDHL, shNSDHL#3 | MISSION® shRNA plasmids, Merck | TRCN0000335870 |

| MSCV-GFP; PGK Puro | Addgene | #68486 |

| MSCV-6NBC-GFP; PGK Puro | Addgene | #83678 - #83764 |

| VSV-G retro | Addgene | #8454 |

| gag/pol retro | Addgene | #14887 |

| pSPAX2 | Addgene | #12260 |

| pMD2.G | Addgene | #12259 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Orbit | Stritt et al., 2020 | https://www.orbit.bio/ |

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 2012 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| GraphpadPrism | N/A | https://www.graphpad.com/company/ Version 7 |

| STRING | Szklarczyk et al., 2019 | https://string-db.org/ Version 11.0 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Barbara M. Grüner (barbara.gruener@uk-essen.de).

Materials availability

There are restrictions to the availability of the newly generated human patient-derived cell line CDX59 due to required ethical approval for use in other studies besides the here approved by the ethics committee of the University Duisburg-Essen Medical Faculty.

Experimental model and subject details

In vivo animal studies

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with and approved by the Stanford University Animal Care and Use Committee (for experiments performed at Stanford University) or the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz Nordrhein-Westfalen (LANUV) (for experiments performed at University Hospital Essen).

Immunocompetent 129/Bl6 F1 mice are the offspring of a cross between C57BL/6J (B6, Stock Number #000664 from The Jackson Laboratory via Charles River) and 129S1/SvImJ (129S, Stock Number #002448 from The Jackson Laboratory via Charles River) mice. Immunodeficient NOD/Scid/ᵧC (NSG) mice were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory via Charles River (Stock Number #005557). Animals were kept in stable groups of 2-5 animals in individually ventilated cages with standard bedding. Water and standard laboratory mouse diet were provided ad libitum. Water was filtered into autoclaved bottles. Bedding was regularly changed under a hood to preserve sterile conditions. Light/dark-rhythm was set at 12:12 hours, and room temperature and humidity were kept stable.

For all animal experiments, both male and female adult mice from the age of 8 weeks or older were equally divided and randomly assigned between all experimental groups. All animal experiments and data analyses were performed without blinding and no power analysis was conducted to pre-determine group size. All animals were tagged with ear marks for identification prior to the experiments. No further procedures were performed besides the described experiments in this manuscript.

Cell lines and primary cultures

All cells were cultured under humified atmosphere at 37°C and 5% CO2. All cell culture experiments were performed in three independent experiments if not mentioned elsewise. Human ASPC1 cells (ATCC Cat# CRL-1682, RRID:CVCL_0152, gender: female), Panc89 cells ((RCB Cat# RCB1021, RRID:CVCL_4056, gender: male), also referenced as T3M-4 (Sipos et al., 2003)), PA-TU-8988T cells (DSMZ Cat# ACC-162, RRID:CVCL_1847, female), PA-TU-8988S cells (DSMZ Cat# ACC-204, RRID:CVCL_1846, gender: female) and YAPC cells (DSMZ Cat# ACC-382, RRID:CVCL_1794, male) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Human NCL-H1975 (ATCC Cat# CRL-5908, RRID:CVCL_1511, female) and PDX (patient derived xenograft) cell line 59 (CDX59, gender: female) were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Human HCT116 (ATCC Cat# CCL-247, RRID:CVCL_0291, gender: male), HEK293T cells (DSMZ Cat# ACC-305, RRID:CVCL_0045, gender: female) and mouse cell line 0688M (gender: male, isolated from a liver metastasis of the autochthonous KrasLSL-G12D/+;Trp53LSL-R172H/+;RosaLSL-tdTomato/+;Pdx1-Cre, described in Grüner et al., 2016) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. All human cell lines have been authenticated by STR analysis. All cell lines were regularly tested to be mycoplasma negative. For compound treatment experiments, cells were seeded for 24 hours and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 to reach a density of 80% at the endpoint of the experiment if not mentioned elsewise. Cells were then treated with the respective compound or control for the desired time period and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Method details

Generation of PDX derived cell line (CDX 59)

After explantation, tumor tissue was stored in RPMI (Life Technologies) without any supplements on ice. The tumor tissue was then minced on ice into 1-2 mm3 cubes. The minced tissue was then transferred into digestion media (RPMI containing 5 mg/mL Collagenase II (Life Technologies) and 1.25 mg/mL dispase (Life Technologies)) and incubated at 37°C with agitation to dissociate the tumor tissue. Cell suspension was subsequently filtered through a 100 μm mesh and cells were collected by centrifugation (300 xg, 5 min) at room temperature. The cell pellet was resuspended in growth media consisting of 50% Keratinocyte-SFM (Life Technologies) supplemented with Epidermal Growth Factor and Bovine Pituitary Extract (Life Technologies), 2% FBS (Life Technologies), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies) and 50% advanced DMEM F12 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS (Life Technologies), 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies). Cells were cultured on collagen-coated dishes (Corning) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. To obtain pure PDAC cell lines, cells were treated with differential trypsinization until no contaminating cells were detected by visual inspection under the microscope.

Chemicals

Compounds used for in vitro experiments were commercially available and listed below. Fluvastatin (abcam, ab120651), cerivastatin (abcam, ab142853), trametinib (biomol, GSK-1120212), mevalonic acid (sigma-aldrich, 50838), lovastatin (abcam, ab120614), dasatinib (Sigma-Aldrich, SML2589), tipifarnib (Sigma-Aldrich, SML1668) were solved in DMSO (AppliChem, A3672). The final concentration of DMSO in medium was maximal 1% and DMSO only was used as vehicle control at the same final concentration. Zoledronic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0223) was solved in water (Braun).

Viral transduction of cells

To generate ASPC1, YAPC, CDX59 and Panc89 cells labeled with GFP we used MSCV retroviral vectors generated using gag/pol-retro and VSV-G-retro packaging plasmids. For shRNA knockdown of NSDHL (shNSDHL#1: TRCN0000335871, shNSDHL#2: TRCN0000335951, shNSDHL#3: TRCN0000335870) and control in ASPC1, YAPC and Panc89 we used MISSION® shRNA plasmids (Merck) plus pSPAX2 and pMD2.G packaging plasmids. For virus production, HEK293T cells were seeded into 6-well plates and individual wells were transfected at 80% confluency with plasmid vector and packaging plasmids using TransIT®-TKO or TransIT®-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Mirus). Media was changed 24 hours later. Supernatants were collected at 48 and 72 hours, pooled, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,200 rpm and the undiluted supernatants were each applied to a 70% confluent well cells. Two days after infection the cells were selected with puromycin (1-3 μg/mL), which effectively kills all uninfected cells. After puromycin selection, GFP expression was tested using flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence (Actin and E-cadherin staining)

For imaging of fixed cells, cells were plated onto collagen type-I-coated glass-bottom dishes (1 h, c = 0.01 mg/ml). The cells were treated in triplicate with fluvastatin or vehicle control for 48 h.

To stain for actin cytoskeleton, cells were fixed by adding formaldehyde-PBS directly to the media to a final concentration 4%, and incubated for 20 min at 37°C. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature. Coverslips were incubated with Phalloidin-Tetramethylrhodamine B (1:500; 35545A, Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at room temperature followed by three times washing with PBS.

To stain for E-cadherin, cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol. To remove methanol coverslips were washed three times with PBS. Unspecific binding of antibody was blocked by incubating coverslips with 2%-BSA-PBS for 1 h. E-cadherin primary antibody (BD Biosciences Cat# 610181, RRID:AB_397580, 1:500) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS before incubating with secondary antibody (goat-anti-mouse-Alexa488; Molecular Probes Cat# A-11029, RRID:AB_138404, 1:500 in 2% BSA-PBS) at room temperature. Coverslips were incubated for 10 min at RT with 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, 1:1000, AppliChem) to stain nuclei. To quench unbound aldehydes coverslips were post-fixed with 2% formaldehyde-PBS. Samples were washed with distilled water and mounted on glass slides using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy of fixed cells was performed on a TCS SP8 AOBS system (Leica Microsystems) equipped with an HC PL APO 20 × /0.75 NA CS objective. Excitation of rhodamine-phalloidin was performed using a 561-nm line laser. Fluorescence was measured using HyD detector (570-630 nm). Excitation of E-cadherin was performed using a 488-nm line of an argon laser. Fluorescence was measured using the HyD detector (495–540 nm). Excitation for DAPI was performed using a 405-nm line with the diode laser and fluorescence was measured using PMT detector (415-440 nm). Acquisition was controlled using LASAF software with HCS-A Matrix Screener module for automated imaging (Leica Microsystems). Confocal z stacks were acquired with 210-nm spacing. Stack building and maximum and sum projections were generated with ImageJ software (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070).

Live cell imaging and live cell tracking

For live cell imaging, cells were plated on μ-Slide VI 0.4 (Ibidi). Microscope used for live-cell imaging is equipped with temperature-controlled incubation chamber and time-lapse live-cell microscopy experiments were performed at 37°C in CO2-independent medium (HBSS buffer, 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 2 mM l-Glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM CaCl2) with indicated frame rates. Phase contrast microscopy was performed using an inverted Ti eclipse system (Nikon). Images were acquired using a Roper Scientific CoolSNAP HQ2 interline-transfer CCD camera. Phase-contrast images were acquired using a CFI S Plan Fluor ELWD 20x/0.45 DIC objective (Nikon). NIS Elements software (Nikon) controlled image acquisition.

Cell migration of ASPC1 and Panc89 cells treated for 48 h with vehicle or fluvastatin (5 μM) was analyzed. Phase contrast imaging was performed for 180 min (framerate 1/min). Image Stabilizer PlugIN (ImageJ (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070)) was used for stage moving correction. Quantification of cells was performed by using manual tracking PlugIN (ImageJ). Tracking of cell nuclei was performed only if cells showed more than 50% free leading edge, no multi-nuclei, no overlapping, and were not dividing during imaging. The chemotaxis and migration tool (Ibidi) was used to show cell migration (accumulated distance and velocity). ASPC1 cells: n = 59-65 cells and Panc89 cells: n = 57-61 cells from three individual experiments. ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; unpaired t test.

13C-labeling experiments

In vitro treatment

ASPC1 cells were seeded in triplicate in 6 well plates. The next day cells were treated for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin (Abcam) or the respective control in medium supplemented with 4.5g/L 13C-Glucose (Sigma-Aldrich). After treatment medium was removed, cells were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl buffer, snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Metabolites extraction and derivatization method

Metabolite extraction were performed in a mixture ice - dry ice as described before (van Gorsel et al., 2019; Elia et al., 2017).

Briefly, cells were extracted with 800 μL of methanol/water (5:3) (v/v) and a volume of 500 μL of precooled chloroform containing 10 μg/ml of C17 internal standard was added to each sample. Therefore, samples were vortexed for 10 min at 4°C and centrifuged for other 10 min (max. speed, 4°C). After centrifugation, metabolites were separated in two phases divided by a protein layer: polar metabolites in the methanol/water (upper) phase and the lipid fraction in the chloroform (lower) phase. The lipid fraction was further separated in two reactions with equal volumes for the analysis of cholesterol and fatty acids. Afterward, every phase was dried at 4°C overnight using a vacuum concentration.

The samples were derivatized and measured as described before (Lorendeau et al., 2017). Fatty acid samples were esterified with 500 μL 2% sulfuric acid in methanol overnight at 50°C. Fatty acids were then extracted by addition of 600 μL of hexane and 100 μL of saturated NaCl. Samples were centrifuged for 5 min, the hexane phase was separated and dried with a vacuum concentrator. Fatty acid samples were then resuspended in 50 μL of hexane. Cholesterol samples was saponified with 500 μL 20% w/v of sodium hydroxide in 50% ethanol at 97°C for 5 min, and the unsaponifiable fraction containing cholesterol was extracted with 600 μL hexane and dried in a vacuum concentrator. The samples were then resuspended in 20 μL of pyridine and 7.5 μL of samples were transferred into a vial and derivatized with 15 μL of trimethylsilyl (TMS) for 1 hour at 40°C.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometric analysis

The metabolites were analyzed by gas chromatography (8860 GC system) coupled to mass spectrometry (5977B Inert MS system) from Agilent Technologies. The inlet temperature was set at 270°C and 1 μL of samples were injected in splitless mode. Metabolites were separated with a DB-FASTFAME column (30 m x 0.250 mm). Helium was used as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. For the separation of fatty acids, the initial gradient temperature was set at 50°C for 1 min and increased at the ramping rate of 12°C/min to 180°C, following by a ramping rate of 1°C/min to rich 200°C. Finally, the final gradient temperature was set at 230°C with a ramping rate of 5°C/min for 2 min. For the measurement of cholesterol, the oven was set at 100°C for 1 min, ramped to 220°C at 20°C/min, following by a ramping of 5°C/min to rich 250°C. The temperatures of the quadrupole and the source were set at 150°C and 230°C, respectively. An electron impact ionization fixed at 70 eV was applied and a full scan mode was used for the measurement of cholesterol and fatty acid, ranging from 200 to 500 a.m.u (mass) and from 100 to 400 a.m.u (mass), respectively.

Data analysis – MATLAB

After the acquisition by GC-MS, an inhouse MATLAB (MATLAB, RRID:SCR_001622) M-file was used to extract mass distribution vectors and integrated raw ion chromatograms. The natural isotopes distribution were also corrected using the method developed by Fernandez et al. (1996). The peak area was subsequently normalized to the protein content and to the internal standard: C17. Palmitate synthesis were calculated based on isotopologue distributions of the according fatty acid, using Isotopomer Spectral Analysis (ISA) (Kharroubi et al., 1992) and an in-house MATLAB script (available on request). Overall levels of labeled palmitate were equal in all treatment groups, indicating that the labeling itself had no effect on cholesterol synthesis (Figure S3C).

Spheroid formation assay

Unless otherwise stated cells were treated in triplicate for 48 h with compound of interest or the respective control. To initiate formation of spheroids cells were seeded in triplicate (8x103-20x103 cells/well) into commercially available cell culture plates with cell-repellent surface (CELLSTAR®, 650970) in medium with drug or vehicle control treatment. Spheroids were grown for 24 h or up to 7 days and pictures taken using Primovert microscope (Zeiss). Spheroids were quantified using ImageJ (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070) as previously described in Oeck et al. (2017).

Assessment of in vitro viability

Cells were seeded in triplicate per condition into 96-well plates (8x103-20x103 cells/well). Compounds were added in different concentrations in triplicate wells. After 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours, cell viability was assessed using the PrestoBlue cell viability assay (A13262, Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s instructions and absorbance at 570 and 600 nm was assessed using a Tecan Spark 10M plate reader (Tecan Trading AG).

Annexin V staining

To assess apoptosis, cells were treated in triplicate for 48 h with compound of interest or the respective control in triplicate and stained for Annexin V according to the manufacturer’s instructions using FITC Annexin V (BD Biosciences Cat# 556419, RRID:AB_2665412). Analysis was done on a BD FACSCelesta Analyzer (Becton, Dickinson and Company).

Anoikis survival assay

To assess anoikis of the cells and to prevent cells from adhering, 6 well plates were coated using a PolyHEMA (Sigma-Aldrich) stock solution (20 mg/ml in 95% EtOH). Cells were pretreated for 48 h with the compound of interest or the respective control, counted and seeded in triplicate with the respective treatment in coated wells and in uncoated wells as apoptosis control. After 24 h of incubation cells were stained for Annexin V (BD Biosciences Cat# 556419, RRID:AB_2665412) to monitor apoptosis using a BD FACSCelesta Analyzer (Becton, Dickinson and Company) as described above. For analysis, the percentage of apoptotic cells of the coated control wells was normalized to the uncoated wells.

Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, cells were treated in triplicate for 48 h with the compound of interest or the respective control in triplicate. Cells were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min. To visualize DNA content cells were stained with DAPI (AppliChem) and analyzed using a FACS Fortessa Analyzer (BD Biosciences).

Colony formation assay

For colony formation assay, cells were treated for 48 h with the compound of interest or the respective control. Cells were seeded in triplicate under drug treatment in triplicate at 2000 cells per well in a 6 well plate. Cells were cultivated at 37°C up to three weeks until colonies were visible. Colonies were washed with PBS and stained for 10-30 minutes with Cyrstal violet. Colonies were automatically counted using ImageJ software (ImageJ, RRID:SCR_003070).

Microarray analysis

For microarray analysis, ASPC1-GFP cells were treated in triplicate for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin or the respective control. After treatment cells were harvested and cell pellets were stored at −80°C. RNA isolation was performed using the QIAGEN kit according to the manufacturer’s manual and stored at −80°C. Affymetrix chip Clariom S Human analysis and normalization of the samples was performed according to standard protocols (DKFZ Heidelberg Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility). A fold change of ± 1.2, p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Gene set enrichment analysis

For gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, RRID:SCR_003199)) the software version GSEA_4.0.3 was used (Mootha et al., 2003; Subramanian et al., 2005). All analyzed gene sets and the software were downloaded from the official GSEA website (the Broad). To perform the analyses, normalized microarray data of ASPC1-GFP cells treated with 5 μM fluvastation (Abcam) or the respective control was used. An FDR of 0.25 and a p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Proteome and phosphorylated proteome analysis

In vitro treatment

For total proteome analysis, ASPC1-GFP cells were treated in quadruplicate for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin (Abcam) or the respective control. To analyze the phosphorylated proteome ASPC1-GFP cells were treated in quintuplicate for 48 h with 5 μM fluvastatin (Abcam) or the respective control and for 15 min with 5 μM fluvastatin (Abcam) or the respective control. After treatment, cells were harvested and cell pellets were stored at −80°C.

Sample preparation for LC/MS/MS

Frozen cell pellets treated with fluvastatin or DMSO (control) were ground in 1 × PBS and then sonicated using a Bioruptor (Diagenode, 4°C, 10 cycles each 1 min maximum energy followed by 30 s pause). The samples were then cleared by centrifugation (20800 × g, 60 min, 4°C) and the supernatant transferred to a fresh Eppendorf tube. Protein concentration was determined using a modified Bradford assay (Roti-Nanoquant®). A volume corresponding to 30 μg of protein was removed for each sample and Methanol/Chloroform precipitated (Wessel and Flügge, 1984). The protein pellet was rehydrated in 6 M Urea and the proteins were subjected to in-solution digestion (ISD). Briefly, proteins were reduced with DTT (5 mM) in 6 M urea and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) for 30 min at room temperature. Protein reduction was followed by alkylation with iodoacetamide (IAM, 10 mM in 50 mM ABC, 30 min, room temperature) and quenching of excess IAM with DTT (final concentration DTT 10 mM). Samples were digested with LysC for 3 h at 37°C. After adjusting the urea concentration to 0.8 M urea with 50 mM ABC the samples were digested for 16 h with trypsin at 37°C. The digestion was stopped by adding formic acid (FA) to a final concentration of 0.5%. The supernatant, containing the digestion products, was passed through home-made glass microfiber StageTips (GE Healthcare, RRID:SCR_000004; poresize: 1.2 μM; thickness: 0.26 mm). Cleared tryptic digests were then desalted on home-made C18 StageTips as described (Rappsilber et al., 2007). Briefly, peptides were immobilized and washed on a two disc StageTip. After elution from the StageTips, samples were dried using a vacuum concentrator (Eppendorf) and the peptides were taken up in 0.1% formic acid solution (10 μL) and directly used for LC-MS/MS experiments (see below for details).

Phosphopeptide enrichment