Abstract

The fission yeast Hsk1p kinase is an essential activator of DNA replication. Here we report the isolation and characterization of a novel mutant allele of the gene. Consistent with its role in the initiation of DNA synthesis, hsk1ts genetically interacts with several S-phase mutants. At the restrictive temperature, hsk1ts cells suffer abnormal S phase and loss of nuclear integrity and are sensitive to both DNA-damaging agents and replication arrest. Interestingly, hsk1ts mutants released to the restrictive temperature after early S-phase arrest in hydroxyurea (HU) are able to complete bulk DNA synthesis but they nevertheless undergo an abnormal mitosis. These findings indicate a second role for hsk1 subsequent to HU arrest. Consistent with a later S-phase role, hsk1ts is synthetically lethal with Δrqh1 (RecQ helicase) or rad21ts (cohesin) mutants and suppressed by Δcds1 (RAD53 kinase) mutants. We demonstrate that Hsk1p undergoes Cds1p-dependent phosphorylation in response to HU and that it is a direct substrate of purified Cds1p kinase in vitro. These results indicate that the Hsk1p kinase is a potential target of Cds1p regulation and that its activity is required after replication initiation for normal mitosis.

Eukaryotic cells have developed elaborate regulatory mechanisms to ensure that DNA replication is restricted to S phase and occurs just once per cell cycle. An important component of this regulation is the coordination of multiple origins of replication. Data from many systems have provided a model of the initiation of DNA synthesis in which several multiprotein complexes interact with discrete replication origins in a specific temporal pattern to regulate entry into S phase (24, 26, 32). Two protein kinase complexes are required to activate the replication origins: cyclin–cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), which acts both positively and negatively to control origin function (21, 22), and the product of the hsk1+ (also called CDC7) gene complex.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe hsk1+ is a member of the conserved family of CDC7 protein kinases (23, 37). The hsk1+ gene was originally cloned by its sequence homology to budding yeast CDC7 and is essential for viability (36). Spores with hsk1+ deleted are able to germinate but fail to undergo DNA replication, demonstrating that Hsk1p is required for cell cycle progression. Hsk1p is dependent on the transient expression of a regulatory subunit, Dfp1p (also called Him1p), for activity towards its substrates (6, 56). Similar to Hsk1p, Dfp1p is also part of a multimember family, founded by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DBF4 gene, and homologues have now been identified in many other species, including Drosophila melanogaster and humans (23, 31). Dfp1p (homologous to Dbf4) is expressed only during late G1 phase until mitosis, thereby restricting Hsk1p activity to S phase and subsequent stages of the cell cycle. Genetic and biochemical evidence indicates that the conserved MCM proteins are important Hsk1p substrates. S. pombe, S. cerevisiae, Xenopus laevis, and human CDC7 kinases phosphorylate Mcm2 in vitro (23, 48). Also, a recessive mutation in S. cerevisiae mcm5 (also called cdc46) bypasses the requirement for CDC7 entirely (20) and there are synthetic interactions between a strain with a mutation in the Cdc7 regulatory subunit, encoded by DBF4, or mcm2 mutants (33).

In addition to having a role in replication initiation, the fission yeast Δhsk1 mutant also has phenotypes suggesting a role in checkpoint responses. While most Δhsk1 spores arrest with a predominantly 1C DNA content and fail to progress into the cell cycle, approximately 25% of these germinated cells go on to attempt an aberrant mitosis, generating “cut” cells (36). This phenotype is typical of mutants that fail to initiate any DNA replication; once replication is initiated, the checkpoint is activated to prevent inappropriate mitosis (28).

The DNA replication and damage checkpoint responses in fission yeast require two kinases acting downstream of the Rad3p kinase: Cds1p (the S. pombe homologue of S. cerevisiae Rad53) and Chk1p (8, 44). rad3+ encodes the homologue of the metazoan ATM and ATR genes and is activated by a range of cellular insults, including UV irradiation and nucleotide depletion (8). The Cds1p and Chk1p kinases then act to inhibit cyclin-CDK activity, thereby preventing mitotic progression.

The replication checkpoint has been extensively investigated using hydroxyurea (HU), an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, which halts replication due to lack of nucleotides (3). Cds1p appears to respond to early replication defects such as those induced by HU and is required for cells to recover from S-phase arrest (35, 39). Cells lacking cds1 arrest in early S phase upon HU treatment but do not enter mitosis. However, they are defective in return to growth, indicating that Cds1p has a role specifically in recovery from S-phase arrest, rather than in prevention of mitosis. Studies suggest that Dfp1p is directly involved in the Cds1p-mediated response to replication arrest. Dfp1p is phosphorylated in vivo upon incubation of the cells with HU, and this phosphorylation depends on active Cds1p (6, 56). In addition, dfp1 mutants that lack a conserved motif in the amino terminus have a mild HU sensitivity and display a cut phenotype after prolonged incubation in HU (56). In budding yeast, Rad53 is required for the phosphorylation of Dbf4 in response to HU (11, 62) and may influence Cdc7 activity at late origins (46, 51). Interestingly, cds1+ is not an essential gene in fission yeast, in contrast to RAD53, which is required for viability in budding yeast (29, 39, 59), suggesting that there may be differences between the two yeasts in the response to replication arrest.

To further examine the role of hsk1+ in fission yeast S phase, we isolated a novel temperature-sensitive allele of the gene. We show that the mutant strain exhibits defects in both DNA replication and checkpoint responses. Consistent with a role in the initiation of DNA synthesis, hsk1ts cells exhibit delayed entry into S phase at the restrictive temperature. However, the cells also have an unusual phenotype for a initiation mutant: rather than showing evidence of premature mitosis, many cells are elongated with fragmented nuclei. Upon release from HU arrest, hsk1ts cells complete bulk DNA synthesis but undergo an abnormal mitosis. This suggests a role for Hsk1p kinase after replication origin firing. In addition, hsk1ts cells show pronounced sensitivity to agents which trigger both the DNA replication and damage checkpoints. Upon HU treatment, Hsk1p is phosphorylated in vivo in a Cds1p-dependent manner and Cds1p directly phosphorylates Hsk1p in vitro. Our data indicate that Hsk1p itself is a target of the checkpoint response and plays a role in S phase after origin firing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General yeast manipulation and molecular biology.

All S. pombe strains (Table 1) were maintained on yeast extract plus supplement (YES) agar plates or under selection on Edinburgh minimal media (EMM) with appropriate supplements using standard techniques (38). Double mutant strains were constructed by standard tetrad analysis. Yeast cells were transformed by electroporation as described previously (54). Standard molecular biology techniques were used (45). A Δhsk1::ura4+/hsk1+ diploid and hsk1+ genomic and cDNA clones were gifts of H. Masai. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was performed as described previously (54). pSLF272-cds1KD contains a kinase-inactive version of cds1 with a D312E mutation (35).

TABLE 1.

Strain list

| Strain | Genotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| FY254 | h−urad4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 can1-1 | Our stock |

| FY440 | h+rad4-116 ura4-D18 leu1-32 | 15 |

| FY818 | h+/h− Δhsk::ura4+/hsk1+ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 | 36 |

| FY945 | h−hsk1-1312 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY961 | h+mis5-268 (mcm6) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 can1-1 | M. Yanagida |

| FY980 | h−hsk1-1312 mcm5HA::leu1+leu1-32 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M216 | This study |

| FY981 | h−hsk1-1312 Δmcm2::(mcm2HA-leu1+) leu1-32 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY982 | h−hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 can1-1 | This study |

| FY983 | h+hsk1-1312 mis5-268 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY984 | h+hsk1-1312 cdc19-P1 ura4-D18 leu1-21 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY998 | h−hsk1-1312 cdc21-M68 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY999 | h+hsk1-1312 Δcds1::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 | This study |

| FY1000 | h−cdc10-V50 hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1002 | h−cdc21-M68 hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1011 | h−cdc22-M45 hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1035 | h−hsk1::p(hsk1-1312HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 can1-1 | This study |

| FY1072 | h+hsk1-1312 cdc25-22 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M216 | This study |

| FY1082 | h+ Δcds1::ura4+hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1085 | h+ Δchk1::ura4+hsk1::p(hsk1HA-ura4+) ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-704 | This study |

| FY1089 | h+cdc23-M36 ura4-D1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1105 | h− Δrad3::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-704 | P. Russell |

| FY1124 | h+hsk1-1312 rad4-116 ura4-D18 leu1-32 | This study |

| FY1125 | h+hsk1-1312 cdc23-M36 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1127 | mat2-102 hsk1-1312 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M216 | This study |

| FY1132 | h+hsk1-1312 orp1-1 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1135 | h−hsk1-1312 cdc24-G1 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1137 | h+hsk1-1312 pol1-1 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1159 | h−rad21-K1::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M216 his7-366 | 57 |

| FY1163 | h−rad12::ura4+ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | 10 |

| FY1176 | h+chk1:ep leu1-32 ade6-M216 | 59 |

| FY1181 | h−hsk1-1312 chk1::ep ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| FY1282 | h−cdc10-V50 hsk1-1312 ura4 leu1 ade6-M210 | This study |

| HSY1 | h−/mat2-102 ura4-D18/+leu1-32/+ade6-M210/ade6-M216 | This study |

| HSY2 | h−/mat2-102 hsk1-1312/hsk1-1312 ura4-D18/ura4-D18 leu1-32/leu1-32 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 | This study |

Isolation of an hsk1-1312 temperature-sensitive strain.

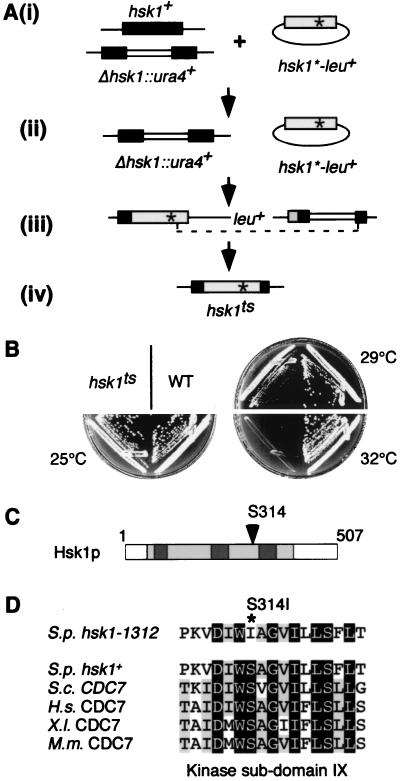

pREP1-hsk1* plasmids were mutagenized in 1 M hydroxylamine solution, pH 6.7, for 20 h at 37°C (43). The mutant library was transformed into a Δhsk1::ura4+/hsk1+ diploid (FY818), and leu+ transformants were recovered (Fig. 1Ai). Each diploid transformant (3,000 in total) was picked and sporulated, and Δhsk1/p(nmt-hsk1) haploids were isolated on selective minimal media (Fig. 1Aii). Each haploid was replica plated onto YES agar containing phloxin B, and temperature-sensitive strains were identified. Plasmids from temperature-sensitive strains were recovered (16 in total), and the entire mutagenized hsk1 sequence was integrated into FY818 at the Δhsk1 locus (Fig. 1Aiii). leu1+ diploids were sporulated, and temperature-sensitive Δhsk1::p(hsk1ts-leu1+)::ura4+ haploids were identified. Counterselection on 5-fluoro-orotic acid was used to isolate strains containing the restored genomic locus, now with a mutant copy of hsk1 (Fig. 1Aiv). hsk1-1312 is mutated at codon 314 from TCT to ATT, resulting in a serine-to-isoleucine substitution.

FIG. 1.

Isolation of a temperature-sensitive allele of hsk1. (A) hsk1-1312 was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Wild-type (WT) (FY254) and hsk1-1312 (FY945) cells were streaked onto YES agar and incubated at 25, 29, and 32°C for 4 days. (C) Hsk1p structure showing the location of the temperature-sensitive lesion. The kinase domains are shown in light-gray boxes, and the kinase insert domains are shown in dark-gray boxes. (D) Alignment of the amino acid sequences in kinase subdomain IX in the CDC7 family of hsk1-1312, showing the temperature-sensitive S314I lesion, and wild-type S. pombe (S.p., GenBank accession no. D50493), S. cerevisiae (S.c., accession no. M12624), Homo sapiens (H.s., accession no. AF015592), X. laevis (X.l., accession no. AB003699), and M. musculus (M.m., accession no. AB018574) hsk1+/CDC7 homologues. Residues conserved among all the kinases are shown in black boxes, and residues conserved between most of the proteins are shown in gray boxes.

Construction of hemagglutinin (HA) and myc-tagged Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp.

The 1,707-bp hsk1+ sequence was amplified by PCR from FY254 wild-type or FY945 hsk1ts genomic DNA and cloned into pSLF172 (15), generating pHS60 (wild type) and pHS69 (temperature sensitive). A version of this plasmid with a LEU2 marker was constructed, generating pHS139. The 3′ hsk13HA sequence was cloned into pJK210 (25) and used to integrate Hsk1pHA or Hsk1tspHA into the genome as a partial tandem duplication (FY982 or FY1035, respectively). C-terminally tagged hsk1-myc (pHS136) was generated by subcloning hsk1 alone from pHS60 into pDS672, which contains two myc tags (D. A. Sherman, S. G. Pasion, and S. L. Forsburg, unpublished data).

HU, bleomycin, and UV treatment.

Cells were treated with 20 mM HU for 4 h at either 25 or 32°C in minimal media or grown on EMM agar plus 5 mM HU. For block and release experiments, 10 to 15 mM HU was added for 4 h, the cells were washed extensively in HU-free EMM, and the cells were reinoculated into EMM. Cells were treated with 5 mU of bleomycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml in minimal media as described previously (16). Cultures of strains to be tested for UV sensitivity were grown to mid-exponential phase in minimal media. One thousand cells of each strain were plated onto two YES agar plates and exposed to a range of UV doses in a Stratalinker (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Viability was calculated as a percentage of cells surviving to form colonies. Viability was determined by serial dilutions, plating on YES agar at 25°C, and comparing the efficiencies of colony formation of treated and untreated cells.

Cell biology.

Immunofluorescence and DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining were performed as described previously (10, 54). For all immunofluorescence experiments, Hsk1pHA and Hsk1tsp were integrated into the chromosome under the native promoter (see tagging of Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp above). Cells were examined using a Leitz Laborlux S microscope, and images were acquired directly by Adobe Photoshop for Macintosh using a Spot II change-coupled-device digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, Mich.). Samples for flow cytometry were prepared as described previously (54). Chromosome loss rates were determined as described previously (34).

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation.

Protein lysates were prepared by glass bead lysis, and immunoprecipitation was carried out essentially as described previously (50, 54). The phosphatase inhibitors 50 mM sodium fluoride, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 20 μM sodium vanadate were included as necessary. Enhanced resolution of the phosphorylated forms of Hsk1p and Chk1p was obtained using a 50:1 ratio of acrylamide-piperazine diacrylamide. Western blotting was performed as described previously (54), and the blots were digitally scanned using a Hewlett-Packard ScanJet IIcx scanner and analyzed using Canvas 6 software for Macintosh (Deneba, Miami, Fla.). Hsk1pHA and Dfp1p-myc were specifically immunoprecipitated using anti-HA 12CA5 (gift of Tony Hunter) and anti-myc 9E10 (BABCO) antibodies as described previously (54).

λ phosphatase assays.

Immunoprecipitates of Hsk1pHA from lysates treated in the presence or absence of HU were washed into λ phosphatase buffer (New England Biolabs, Beverley, Mass.) plus 2 mM manganese chloride. The pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of assay buffer, 400 U of λ phosphatase (New England Biolabs) was added to each sample, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was halted by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and boiling for 3 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting as described above.

Kinase assays.

For Hsk1p autokinase assays, Hsk1pHA or Hsk1tspHA was immunoprecipitated from protein lysates as described above. The immunoprecipitates were resuspended in 40 μl of assay buffer (25 mM MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid, pH 7.2], 15 mM MgCl2, 15 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiotreitol, 60 mM β-glycerophosphate, 15 mM ρ-nitrophenol phosphate, 0.1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μg of leupeptin per ml, 40 μg of aprotinin per ml). Twenty microliters of this slurry was incubated with 200 μM [γ-32P]ATP (NEN, Boston, Mass.) for 30 min at 32°C. The reaction was halted by boiling the slurry in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS–10% PAGE gels, the gels were exposed to a PhosphorImager screen, and the images were analyzed using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Cds1p was purified from extracts of 2 g of GBY438 following growth for 20 h in the absence of thiamine, with 15 mM HU being added during the last 4 h of growth. Purification to apparent homogeneity was achieved in two steps, using Talon-Sepharose and anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5–protein A-Sepharose, as described previously (7). Cds1p kinase assays were performed as previously described (6) except that 100 μM ATP was used and bovine serum albumin was omitted. Assay mixtures contained the Hsk1pHA immunoprecipitate from approximately 4 mg of extract and 50 ng of Cds1p.

RESULTS

Isolation of a novel temperature-sensitive allele of hsk1.

To allow genetic analysis of the fission yeast hsk1+, we isolated the first conditional allele of this gene, using a plasmid shuffle screen (Fig. 1A) (52). From a total of 3,000 plasmids initially screened, we isolated a single integrated allele, hsk1-1312. hsk1-1312 supports growth at 25°C, is semipermissive for growth at 29°C, but is insufficient for growth at 32°C and above (Fig. 1B). This phenotype can be completely complemented by expression of hsk1+ from a plasmid (data not shown). The temperature-sensitive lesion in hsk1-1312 is a 2-bp mutation that changes serine 314 in kinase subdomain IX to isoleucine (Fig. 1C). This serine residue, which is completely conserved in S. cerevisiae Cdc7 and other metazoan CDC7 homologues, is located 3 residues from a similarly conserved aspartate residue that stabilizes the catalytic loop in kinase subdomain VIB (Fig. 1D) (19).

We constructed a panel of double mutant strains with hsk1-1312, hereinafter denoted hsk1ts, and other components involved in the early stages of DNA replication (Table 2). hsk1ts interacts genetically with two of the mcm mutants, the mcm2 and mcm6 mutants, but not with the third, the mcm4 mutant. The double mutant hsk1ts strains with the rad4 initiator protein or the MCM10 homologue cdc23 also have a lower maximum permissive temperature than that of either of the single mutants alone. These genetic interactions with putative initiators are consistent with the expected role of hsk1+ in replication initiation.

TABLE 2.

Summary of genetic interactions of hsk1ts mutants

| Mutation | Function | Genetic interactiona |

|---|---|---|

| orp1 | ORC subunitb | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| rad4 | Initiator protein | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| cdc19 | MCM2 | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| cdc21 | MCM4 | No interaction |

| mis5 | MCM6 | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| cdc23 | MCM10/DNA43 | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| cdc24 | S phase? | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| pol1 | DNA polymerase α | No interaction |

| Δrqh1 | DNA helicase | Synthetically lethal |

| cdc25 | Cdc2p phosphatase | ↓ max. perm. temp. |

| rad21 | Mitotic cohesin | Synthetically lethal |

| Δcds1 | Checkpoint kinase | Suppression |

| Δchk1 | Checkpoint kinase | Synthetically lethal |

| Δrad3 | Checkpoint kinase | Synthetically lethal |

Downward-pointing arrows indicate reduced growth temperature. max. perm. temp., maximum permissive temperature.

ORC, origin recognition complex.

Effects of hsk1ts on protein function.

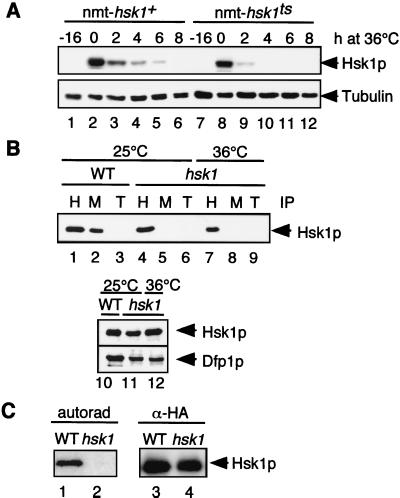

We investigated the effect of the hsk1ts mutation on the stability and protein interactions of the Hsk1ts protein. The temperature-sensitive Hsk1 protein (Hsk1tsp) is slightly less abundant than the wild-type version in asynchronously growing cells (data not shown). To determine if this reduction in protein level is due to increased protein turnover, we compared the stabilities of Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp at the restrictive temperature. Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp were expressed from the thiamine-repressible nmt1 promoter. Following repression of expression, Hsk1p was degraded within 8 h, whereas temperature-sensitive Hsk1tsp was undetectable after only 4 h at 36°C (Fig. 2A), demonstrating that Hsk1tsp is indeed less stable than the wild-type protein. It has recently been reported that Cdc7 in S. cerevisiae is able to homo-oligomerize (49). We found that this interaction is conserved with Hsk1p in S. pombe and that Hsk1tsp is still capable of multimerizing with the wild-type Hsk1 protein (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Hsk1p protein analysis. (A) Hsk1tsp has lower stability at 36°C than Hsk1p. Wild-type cells (FY254) were transformed with plasmids bearing genes expressing either Hsk1pHA (nmt-hsk1+, pHS60) or Hsk1tspHA (nmt-hsk1ts, pHS69). Hsk1pHA expression was induced for 16 h at 25°C, 15 μM thiamine was added back to the media, and the cultures were shifted to 36°C for 8 h. Aliquots were removed at −16 h (before induction, lanes 1 and 7), at 0 h (after induction, lanes 2 and 8), and at 2 h (lanes 3 and 9), 4 h (lanes 4 and 10), 6 h (lanes 5 and 11), and 8 h (lanes 6 and 12) after the addition of thiamine. Each lysate (10 μg) was immunoblotted for Hsk1pHA (lanes 1 to 6), Hsk1tspHA (lanes 7 to 12), and tubulin (lanes 1 to 12). (B) Hsk1tsp fails to interact with Dfp1p. Expression of Dfp1p-myc (pSLF272-dfp1+myc [6, 15]) was induced in wild-type (WT) (FY982) or hsk1ts (FY1035) cells. The culture of hsk1ts was split, with half being kept at 25°C and the other half being incubated at 36°C for 6 h. Proteins were immunoprecipitated from each lysate with either anti-HA (H), anti-myc (M), or anti-tubulin (T) antibodies, and the immunoprecipitates (IP) were immunoblotted with anti-HA antibodies. Lanes 1 to 3, wild type; lanes 4 to 6, hsk1ts cells at 25°C; lanes 7 to 9, hsk1ts cells at 36°C. The lower gel indicates the loading control. Crude extracts used for immunoprecipitation were blotted for Hsk1-HA and Dfp1-myc. Lane 10, wild type; lane 11, hsk1ts cells at 25°C; lane 12, hsk1ts cells at 36°C. (C) Kinase activity is abrogated in hsk1ts cells. Kinase assays were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. HA-tagged Hsk1p (lanes 1 and 3) or Hsk1tsp (lanes 2 and 4) was immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA antibody (α-HA). Half the immunoprecipitate was subjected to kinase assay (lanes 1 and 2), and the other half was subjected to immunoblotting (lanes 3 and 4). autorad, autoradiograph.

However, other aspects of Hsk1tsp activity are aberrant. Hsk1p requires its regulatory subunit Dfp1p for activity against the Mcm2p substrate (6). We found that even at the permissive temperature, Hsk1tsp displays a much lower affinity for Dfp1p than that observed with wild-type Hsk1p (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, Hsk1tsp has severely reduced autophosphorylation activity at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 2C). It has been observed that certain cdc7 mutants of S. cerevisiae can be complemented by overexpression of the Dfp1p homologue Dbf4 (30). However, we did not observe a similar rescue of hsk1ts by high levels of Dpf1p (data not shown). Thus, the temperature-sensitive lesion in Hsk1tsp clearly disrupts several features which are necessary for the proper activity of the protein.

Hsk1tsp disrupts nuclear localization.

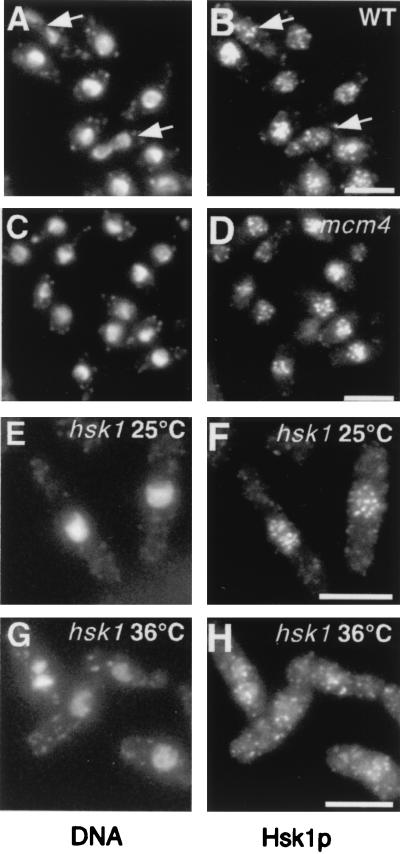

We next examined the localization of Hsk1p in wild-type cells and in mutants blocked at different stages of the cell cycle by indirect immunofluorescence. In wild-type cells, Hsk1p exhibits punctate nuclear staining throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 3A and B). In mitotic cells just undergoing nuclear division, the localization of Hsk1p is less well defined (Fig. 3A and B), although the protein clearly remains in the nucleus even in cells arrested in mitosis by various cell cycle mutants (data not shown). Since Dfp1p is quite unstable and present only during S and G2 phases (6, 56), this indicates that Hsk1p nuclear localization is independent of Dfp1p.

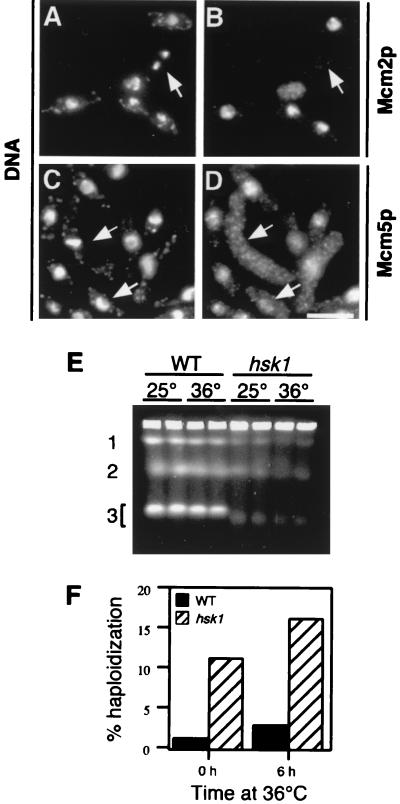

FIG. 3.

Localization of Hsk1p. Hsk1pHA or Hsk1tspHA was expressed from the endogenous promoter in the genome. Cells were prepared for indirect immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods and stained with DAPI to detect the DNA (A, C, E, and G) or with the anti-HA antibody 16B12 to visualize Hsk1p (B, D, F, and H). Wild-type cells were grown at 32°C in minimal media prior to being stained. Temperature-sensitive strains were grown to mid-log phase at 25°C and then shifted to 36°C for 4 h prior to being stained. In all cases, HA-tagged hsk1+ was integrated into the genome. (A to D) Hsk1pHA localizes to discrete spots in the nucleus independently of MCM proteins. Shown are the localizations of Hsk1p in wild-type cells (FY982) (A and B) and in cdc21-M38 cells (FY1002) (C and D). The arrows in panels A and B indicate mitotic cells. (E to H) Hsk1tsp is redistributed from the nucleus at 36°C. hsk1ts cells (FY1035) were grown in minimal media to mid-log phase at 25°C (E and F) or shifted to 36°C for 6 h (G and H). In all cases, the scale bar represents 10 μm.

Although the Hsk1p substrate Mcm2 (also called Cdc19p) is located in the nucleus throughout the cell cycle (41), in mcm mutant strains MCM proteins are redistributed to the cytoplasm (42). However, these same mutations have no effect on the localization of Hsk1p, which remains nuclear (Fig. 3C to D and data not shown), demonstrating that proper localization of Hsk1p is independent of its substrate. Hsk1p localization was also unaffected by mutation in a subunit of the origin recognition complex, orp1, or treatment with HU (data not shown).

In contrast, Hsk1tsp is redistributed to the cytoplasm at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 3E to H). Even at 25°C, there is an increase in cytoplasmic background staining in comparison with that of wild-type cells (Fig. 3A and B). At the restrictive temperature, specific nuclear localization of Hsk1tsp is all but lost and staining is seen throughout the cell body (Fig. 3H), suggesting that the protein is either being specifically exported from the nucleus or failing to localize correctly.

hsk1ts causes G1 phase delay and defects in nuclear integrity.

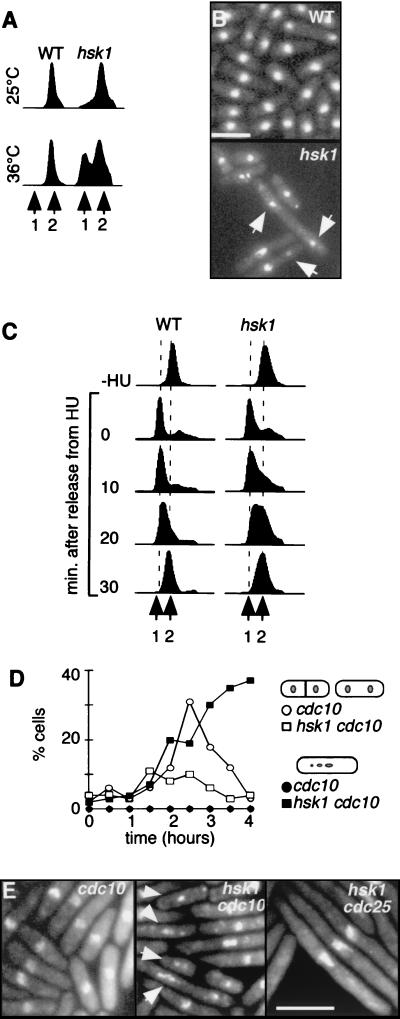

We examined the phenotype of the hsk1ts mutant. Upon a shift to the restrictive temperature for 4 h, hsk1ts cells displayed a transient G1 delay (Fig. 4A). Most cells finally arrested with an approximately 2C DNA content, but there were increasing numbers of cut cells containing less than 1C DNA (data not shown). Furthermore, cells with fragmented nuclei were also apparent when the culture was examined microscopically (Fig. 4B). This fragmentation suggests a defective checkpoint and is similar to the phenotype reported for the Δhsk1 allele (36). Several initiation mutants undergo premature mitosis in the absence of replication. However, in contrast to those mutants with typical initiation checkpoint defects, hsk1ts cells were noticeably elongated, indicating a cell cycle delay, and cells with <1C DNA content appeared only 4 h following the shift to the nonpermissive temperature. This timing and morphology strongly argue against premature entry into mitosis.

FIG. 4.

hsk1ts exhibits a G1 delay and loss of nuclear integrity at the restrictive temperature. (A) hsk1ts exhibits G1 delay. The DNA profiles of wild-type (FY254) (WT) and hsk1ts (FY945) cells were examined by flow cytometry. Cells were grown at 25°C in minimal media to mid-log phase before being shifted to 36°C for 4 h. Aliquots were removed at 0 and 4 h and prepared for flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of 1C and 2C DNA contents are indicated. (B) hsk1ts has abnormal chromosomes. Shown is DAPI staining to visualize nuclei of wild-type (FY254) (top) and hsk1ts (FY945) (bottom) cells after 6 h at 36°C. Arrows indicate chromosome fragments. (C) Both wild-type and hsk1ts cells complete DNA synthesis after HU arrest and release to 36°C. Wild-type (FY254) and hsk1ts (FY945) cells were arrested in HU at 25°C and released to 36°C. Aliquots were removed for analysis by flow cytometry prior to the addition of HU and at 0, 10, 20, and 30 min after release from HU. Fewer than 5% of the cells showed a cut phenotype (data not shown). (D) Timing of mitosis and fragmentation in hsk1ts cdc10 and cdc10 cells. Cells were arrested in HU for 4 h and released to 36°C without HU. Cell morphology was determined by DAPI staining and examination by fluorescence microscopy. The percentages of cells displaying the indicated phenotypes were plotted against time. Open symbols, normal mitotic cells in cdc10 (○) or cdc10 hsk1 (□) cells; closed symbols, fragmented nuclei in cdc10 (●) or cdc10 hsk1 (■) cells. (E) Fragmentation in hsk1 strains requires entry into mitosis. Samples from the experiment whose results are shown in panel D were photographed after 4 h at the restrictive temperature. Left, cdc10 cells; middle, hsk1ts cdc10 cells (arrows indicate fragmented nuclei); right, hsk1ts cdc25 cells. hsk1ts cdc10 and hsk1ts cells have identical phenotypes (data not shown).

We determined the hsk1ts execution point for both the replication and DNA fragmentation phenotypes by using an HU block and release experiment (Fig. 4C). hsk1ts and wild-type cells were arrested in early S phase by treatment with HU at the permissive temperature of 25°C and then shifted to 36°C to inactivate Hsk1tsp. hsk1ts cells in HU became elongated with single nuclei, as did wild-type cells (data not shown). After HU was removed, both wild-type and hsk1ts cells completed DNA synthesis in about 30 min, indicating that hsk1ts was not required for DNA replication after the HU arrest point. However, the flow cytometry profile of hsk1ts revealed kinetics of DNA accumulation different from those of the wild type. This finding is consistent with the failure of late origins to fire in hsk1ts cells at the restrictive temperature, as seen in analogous experiments with S. cerevisiae cdc7 mutants (12).

Strikingly, the nuclear structure of hsk1ts cells released from HU to the restrictive temperature became highly disordered after the completion of DNA replication (Fig. 4E and data not shown). A large fraction of the hsk1ts cells were elongated, and the DNA fragmented into several visible pieces of DAPI-stained material. This suggests that the Hsk1p kinase has a second execution point, after replication initiation, which is required to maintain chromosome integrity. Significantly, this phenotype resembled that observed in many of the cells following the shift of the hsk1ts strain to the restrictive temperature (Fig. 4A). Therefore, the nuclear fragmentation phenotype is not simply a consequence of HU arrest but indicates a role for Hsk1p after the initiation of bulk DNA synthesis in order to maintain chromosome integrity during mitosis. This function is apparently separable from its role in replication initiation, which has an execution point prior to the HU arrest.

Establishment of chromosome cohesion depends upon successful passage through S phase (53, 58). In fission yeast, a temperature-sensitive mutant in the rad21 cohesin exhibits abnormal mitosis at the restrictive temperature, with aberrantly condensed chromosomes and unequally divided nuclei (57). These phenotypes are similar to those we observed in hsk1ts cells (Fig. 4B). We found that the rad21ts cohesin mutant is synthetically lethal with hsk1ts (Table 2), which may indicate a role for Hsk1p in ensuring correct chromosome cohesion as S phase progresses.

Despite the fragmentation phenotypes we observed, hsk1 mutant cells maintained high viability following 4 h at the restrictive temperature or after 4 h in HU, although colony size was heterogeneous (data not shown). This result suggests that the cells can recover from the damage if exposure to restrictive conditions is not prolonged.

To determine whether DNA fragmentation in the hsk1ts cells depends upon passage through mitosis, we repeated the HU block and release experiment with cdc10, hsk1ts cdc10, and hsk1ts cdc25 mutant strains. First, we monitored the appearance of normal mitotic cells and cells with fragmented nuclei in the two cdc10 strains. Following HU release, the cdc10 mutant arrested in the G1 phase of the following cell cycle, ensuring that we were observing events in a single mitosis. As seen in Fig. 4D, the cdc10 mutant underwent mitosis, with a peak at 2.5 h. The hsk1ts cdc10 strain accumulated cells with fragmented nuclei with similar timing, which suggests that fragmentation occurs as a consequence of mitotic entry. This result also demonstrates that entry into mitosis in the double mutant strain occurs with normal timing; this phenotype was identical to that observed in the hsk1ts mutant alone. When the hsk1ts cdc25 cells were released to 36°C, they completed S phase and arrested at the G2/M phase transition due to the lack of active Cdc25p (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4E, no chromosome fragmentation was detected in the hsk1ts cdc25 strain. Thus, the abnormal morphology in the hsk1ts strain reflects passage through mitosis of cells with apparently replicated DNA but does not reflect premature mitosis, since timing of entry appeared normal.

Since the hsk1ts mutant showed abnormal, fragmented nuclei and Hsk1tsp was lost from the nucleus, we next asked whether other nuclear proteins were also redistributed. As shown in Fig. 5A to D, the typical nuclear localization of Mcm2p or Mcm5p was unaffected by the relocalization of Hsk1tsp, suggesting that MCM protein localization is independent of Hsk1p function and showing that overall nuclear integrity is maintained in hsk1ts cells. In cells where chromosomal fragmentation was observed, there was little association of the MCM proteins with the smaller DAPI staining material.

FIG. 5.

hsk1ts has increased genome instability. (A to D) MCM proteins remain nuclear in hsk1ts cells. The hsk1ts allele was combined with a strain carrying an integrated HA-tagged copy of either Mcm2p (FY981) (A and B) or Mcm5p (FY980) (C and D). The strains were grown in minimal media for 6 h at 36°C. The arrows in panels A and B indicate cells with highly abnormal chromosomes which have reduced MCM protein localization. The scale bar represents 10 μm. (E) hsk1ts cells have structurally abnormal chromosomes as determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Wild-type (FY254) (WT) and hsk1ts (FY945) cells were grown at either 25 or 36°C for 6 h. Whole chromosomes were prepared in agarose plugs and run in a 0.6% agarose gel as described in the text. The positions of chromosomes 1 to 3 are indicated. (F) hsk1ts homozygous diploids display elevated rates of chromosome loss. Wild-type (HSY1) or hsk1ts (HSY2) diploids were scored for chromosome loss as described in the text. Results of an experiment representative of three separate experiments which gave similar results are shown.

We examined the chromosome structure in the hsk1ts mutant strain using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, which allows resolution of the three individual chromosomes of S. pombe. Chromosomes that are undergoing DNA replication or have aberrant structures fail to enter the gel (27, 34). As seen in Fig. 5E, the three chromosomes from hsk1ts cells did not enter the gel very efficiently compared to the wild type, even at the permissive temperature, and this effect was exacerbated in chromosomes isolated from hsk1ts cells at the restrictive temperature. We also observed that the mobility of chromosome 3 in the mutant was higher than in the wild type, suggesting that this chromosome may be smaller than normal. A similar effect has been reported for mcm2 mutants (34). There is no obvious smear of chromosomal fragments, such as that observed in cdc24 mutants (17); thus, if hsk1ts chromosomes are fragmented, they must have sufficient structural abnormalities to prevent migration into the gel.

Finally, we investigated the genome stability of hsk1ts cells by comparing rates of chromosome loss as assessed by haploidization. Diploid fission yeast cells that lose one chromosome rapidly are reduced to the haploid state. Hence, the rate of chromosome loss can be inferred by haploidization of nonsporulating diploids (4). As shown in Fig. 5F, hsk1ts/hsk1ts diploids display a much higher rate of chromosome loss than that of the wild type, even at the permissive temperature, and this is further elevated by shifting the culture to the restrictive temperature. These results clearly demonstrate that hsk1ts causes a significant decrease in genome stability at all temperatures.

Hsk1p is a target of the replication checkpoint kinase Cds1p.

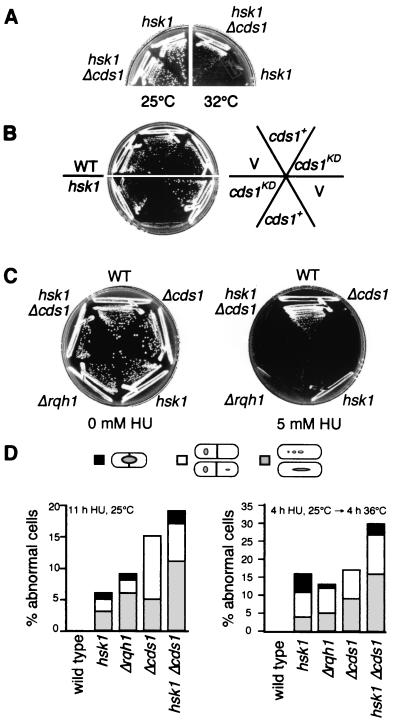

Strains with defects in genome stability are often sensitive to agents that challenge chromosomal integrity. We examined the HU response of the hsk1ts mutant more closely. Arrest in HU triggers the so-called replication checkpoint, and recovery from HU arrest requires the activities of the Cds1 and Rqh1 proteins (3). cds1+ encodes a nonessential checkpoint kinase (39), and rqh1+, also known as rad12+ or hus2+, encodes a RecQ-type helicase (9, 40, 55). Mutation of these proteins does not cause premature mitosis but rather affects the ability of arrested cells to recover and reenter the cell cycle after HU is removed. We analyzed the genetic interactions between hsk1ts, Δcds1, and Δrqh1 mutants. Strikingly hsk1ts and Δrqh1 mutants were synthetically lethal, since it was not possible to recover an hsk1ts Δrqh1 double mutant (Table 2; data not shown). In contrast, deletion of cds1+ appeared to partially suppress hsk1ts, since the double mutant formed small colonies at 32°C, a temperature restrictive for hsk1ts growth (Table 2; Fig. 6A). Moreover hsk1ts was hypersensitive to overexpression of active, but not kinase-inactive, Cds1p (Fig. 6B). However, the fluorescence-activated cell sorter profiles were not significantly different (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

hsk1ts is required for recovery from replication arrest. (A) hsk1ts can be partially suppressed by deletion of cds1. hsk1ts (FY945) or hsk1ts Δcds1 (FY999) double mutant cells were streaked onto YES agar at 25 or 32°C. (B) Moderate overexpression of Cds1p is toxic in hsk1ts cells. Wild-type (WT) and hsk1ts cells were transformed with either pREP4X (V), pSLF272-cds1+ (cds1+), or pSLF272-cds1KD (cds1KD), and expression was induced at 25°C. (C) hsk1ts is sensitive to HU. Wild-type (FY254), Δcds1 (FY866), hsk1ts (FY945), Δrqh1 (FY1163), and hsk1ts Δcds1 (FY999) cells were grown on minimal media or minimal media plus 5 mM HU at 25°C. (D) Abnormal cell morphologies were scored after treatment with HU. Wild-type, hsk1ts, Δrqh1, Δcds1, and hsk1ts Δcds1 cells were treated with 10 mM HU for 11 h at 25°C (left), or 4 h at 25°C followed by release to HU-free media at 36°C for 4 h (right). Cells were stained with DAPI and examined microscopically. Abnormal cells were classified as those displaying a cut morphology (black), unequal segregation (white), or fragmented or irregular nuclei (gray). Two hundred cells were counted for each strain.

If Hsk1p activity is required for cells to recover from replication arrest, we would expect hsk1ts strains to display phenotypes similar to those of Δcds1 and Δrqh1 mutants following prolonged exposure to sublethal doses of HU. We compared the responses of wild-type, hsk1ts, Δcds1, Δrqh1, and hsk1ts Δcds1 cells to low levels of HU at the permissive temperature (Fig. 6C). Although the wild-type strain formed colonies efficiently in the presence of 5 mM HU, hsk1ts, Δcds1, Δrqh1, and hsk1ts Δcds1 cells were unable to grow. Since hsk1ts cells arrested normally in response to HU treatment, as did Δcds1 and Δrqh1 cells (Fig. 4C and data not shown), we conclude from this assay that hsk1ts cells are similarly defective in the recovery from S-phase arrest. Microscopic examination of hsk1ts, Δcds1, Δrqh1, and hsk1ts Δcds1 cells following prolonged incubation in HU at the permissive temperature revealed that all strains developed increasing numbers of cut cells and other aberrant nuclear morphologies (Fig. 6D) (55). In particular, both hsk1ts and Δrqh1 cells exhibited fragmentation similar to that seen in the hsk1ts mutant at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 4A and data not shown) (55). Interestingly, in the hsk1ts Δcds1 mutant, the fraction of abnormal cells was higher than that observed in either single mutant (Fig. 6D, left graph). Upon examination of hsk1ts and Δrqh1 cells after release from HU arrest to the restrictive temperature for hsk1ts, we found that both strains accumulated large numbers of cells with aberrant chromosome structures and that both were more severely affected than the Δcds1 mutant alone (Fig. 6D, right graph). Thus, the chromosome integrity of all these mutants appeared to be affected upon prolonged arrest in HU. However, the double mutant phenotypes and complex genetic interactions suggest that these effects are mediated through separable pathways, indicating that recovery from HU requires multiple components of the replication and repair machinery.

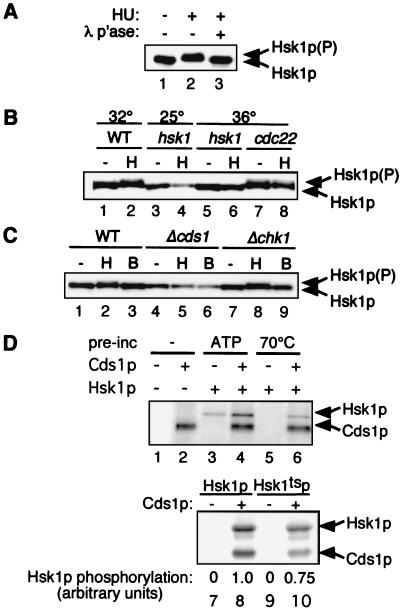

The genetic suppression of hsk1ts by deletion of cds1+ and its sensitivity to Cds1p overproduction suggest that Cds1p antagonizes some aspect of Hsk1p activity. To determine whether Hsk1p is itself a target of Cds1p, we examined Hsk1p from cell extracts grown in the presence or absence of HU by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 7A). Hsk1p from HU-treated cells migrated with a reduced mobility compared to that from untreated cells. This modest mobility shift could be reversed by treatment with λ phosphatase, indicating that the modification reflects phosphorylation. The same modification of Hsk1p is seen in a strain with a mutation in the catalytic subunit of the ribonucleotide reductase cdc22 (Fig. 7B), which phenocopies HU treatment (47). Since the hsk1ts strain is sensitive to HU, we speculated that the mutant protein might not respond to HU treatment. Indeed, we found that temperature-sensitive Hsk1tsp does not display a detectable phosphorylated form following treatment with HU at either the permissive or restrictive temperature (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Hsk1p is phosphorylated by Cds1p in response to HU. (A) Hsk1p is phosphorylated in the presence of HU. Wild-type cells were or were not treated with HU. Lysates were prepared from wild-type cells (FY982) in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors, and HA-tagged Hsk1p was immunoprecipitated from the lysates using an anti-HA antibody. Samples were run on 6% acrylamide–piperazine diacrylamide gels, as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, Hsk1p minus HU; 2, Hsk1p plus HU; 3, Hsk1p plus HU treated with λ phosphatase (λ p'ase) as described in Materials and Methods. (P), phosphorylated. (B) Hsk1p is modified in cdc22 cells, but Hsk1tsp is not phosphorylated in the presence of HU at any temperature. Lysates were prepared from wild-type (FY982) (WT), hsk1ts (FY1035), and cdc22 (FY1011) strains carrying HA-tagged integrated Hsk1p, grown in the presence (H) or absence (−) of 20 mM HU. Protein lysate (10 μg) was analyzed by immunoblotting following electrophoresis as described for panel A above. Lanes: 1, wild type, 32°C; 2, wild type plus HU for 4 h at 32°C; 3, hsk1ts cells at 25°C; 4, hsk1ts cells plus HU at 25°C; 5, hsk1ts cells for 4 h at 36°C; 6, hsk1ts cells plus HU for 4 h at 36°C; 7, cdc22 cells for 4 h at 36°C; 8, cdc22 cells plus HU for 4 h at 36°C. (C) Hsk1p phosphorylation requires Cds1p. Whole-cell lysates were prepared from wild-type (FY982), Δcds1 (FY1082), and Δchk1 (FY1085) cells, and cells expressing Hsk1pHA were grown in the absence (−) or presence of HU (H) or bleomycin (B). Protein lysate (10 μg) was analyzed by immunoblotting following electrophoresis as described for panel A above. Lanes: 1, wild-type untreated cells; 2, wild type cells plus HU; 3, wild-type cells plus bleomycin; 4, Δcds1 untreated cells; 5, Δcds1 cells plus HU; 6, Δcds1 cells plus bleomycin; 7, Δchk1 untreated cells; 8, Δchk1 cells plus HU; 9, Δchk1 cells plus bleomycin. (D) Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp are Cds1p kinase substrates in vitro. (Upper gel) Hsk1p was immunoprecipitated from extracts of fission yeast strains containing pHS60 (Materials and Methods). The Hsk1p immunoprecipitates were preincubated (pre-inc) with cold ATP (lanes 3 and 4) or heat inactivated at 70°C (lanes 5 and 6) (6) and incubated with Cds1p kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. Reaction products were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen. Lanes: 1, no protein; 2, Cds1p only; 3, Hsk1p preincubated with cold ATP; 4, Hsk1p preincubated with cold ATP plus Cds1p; 5, Hsk1p preincubated at 70°C; 6, Hsk1p preincubated at 70°C plus Cds1p. (Lower gel) Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp were immunoprecipitated from extracts of fission yeast strains containing pHS60 and pHS69, respectively. The immunoprecipitates were heat inactivated at 70°C and incubated in the absence or presence of Cds1p. The relative levels of incorporation of 32P into Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp were determined using ImageQuant software and are given in arbitrary units. Lanes: 7, Hsk1p only; 8, Hsk1p plus Cds1p; 9, Hsk1tsp only; 10, Hsk1tsp plus Cds1p.

We investigated which checkpoint kinases were required for the observed Hsk1p phosphorylation. We treated wild-type, Δcds1, and Δchk1 cells with HU and examined Hsk1p modification. HU-induced phosphorylation of Hsk1p was not detected in Δcds1 cells (Fig. 7C) but did occur in Δchk1 mutants. We also treated cells with the radiation mimetic drug bleomycin, which activates the damage response pathway (16), but we observed no alteration in the mobility of Hsk1p (Fig. 7C). Thus, these data suggest that Hsk1p is a specific target of the DNA replication checkpoint rather than the DNA damage response pathway.

To determine whether Hsk1p is a direct target of Cds1p, we examined the ability of the purified Cds1p kinase to phosphorylate immunoprecipitated Hsk1p (Fig. 7D). In order to eliminate any background due to autophosphorylation, we used heat-inactivated Hsk1p immunoprecipitated from appropriate strains as a substrate (Fig. 7D) (6). Both Hsk1p and Hsk1tsp were phosphorylated by Cds1p in vitro (Fig. 7D). This result provides the first evidence that the catalytic subunit of the Hsk1p kinase itself can be phosphorylated by Cds1p kinase.

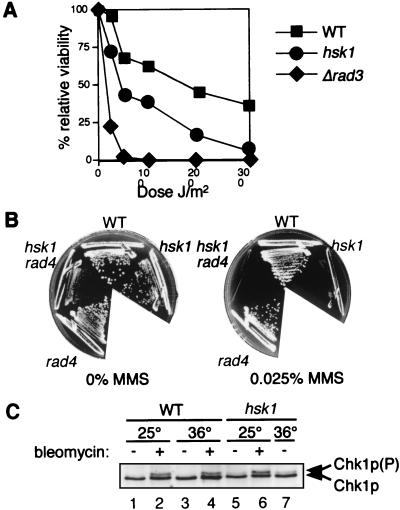

hsk1ts requires the damage checkpoint for viability.

hsk1ts is sensitive to several agents that induce DNA damage. As can be seen in Fig. 8A, hsk1ts cells were considerably more sensitive to UV light than wild-type cells but were not as severely affected as Δrad3 cells. We also tested the sensitivity of hsk1ts to the drug methyl methane sulfonate (MMS) and found that hsk1ts cells are much more sensitive to MMS than wild-type and rad4 cells (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, we were unable to construct double mutants with hsk1ts and the Δchk1 or Δrad3 checkpoint kinases (Table 2). This inability of cells to grow in the absence of chk1 or rad3 when there were mutations in hsk1 suggests that hsk1ts may cause chromosomal lesions even at the permissive temperature which require the presence of a fully functional DNA damage checkpoint pathway to delay mitosis for adequate repair. This requirement would be consistent with either defects in initiation or defects in overall chromosome stability. We tested this theory by examining the phosphorylation state of the Chk1 protein, since it has previously been shown that the phosphorylation of Chk1p correlates with activation of the DNA damage checkpoint (60). In wild-type cells, Chk1p was activated only upon treatment with bleomycin. In contrast, Chk1p phosphorylation was observed in hsk1ts cells even in the absence of bleomycin, at both 25 and 36°C, indicating partial activation of the DNA damage checkpoint in these mutant cells (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

hsk1ts is sensitive to DNA-damaging agents. (A) hsk1ts cells are sensitive to UV irradiation. Wild-type (FY254) (WT), hsk1ts (FY945), and Δrad3 (FY1105) cells were treated with UV irradiation as described in Materials and Methods. The graph represents relative levels of viability following treatment with the indicated doses. The results of one representative experiment are presented. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (B) hsk1ts cells are sensitive to MMS. Wild-type (FY254), hsk1ts (FY945), rad4 (FY440), and hsk1ts rad4 (FY1124) cells were streaked onto YES agar plates with or without 0.025% MMS at 25°C. (C) The DNA damage checkpoint is activated in hsk1ts cells. Wild-type (FY1176) or hsk1ts (FY1181) cells were grown at 25 or 36°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of 5 mU of bleomycin per ml. Lysates were prepared, and 20 μg of total protein was separated on 8% acrylamide–piperazine diacrylamide gels, as described in Materials and Methods. The mobility of Chk1p was determined by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies. Lanes: 1, wild type at 25°C; 2, wild type at 25°C plus bleomycin; 3, wild type at 36°C; 4, wild type at 36°C plus bleomycin; 5, hsk1ts cells at 25°C; 6, hsk1ts cells at 25°C plus bleomycin; 7, hsk1ts cells at 36°C. (P), phosphorylated.

DISCUSSION

In this report we have described the isolation and characterization of the first temperature-sensitive allele of S. pombe hsk1+. The mutant allele, hsk1-1312, changes serine 314 in kinase subdomain IX, which is conserved in all CDC7 family members, into an isoleucine. This mutation causes a decrease in the stability of Hsk1tsp, as well as reduced autophosphorylation activity and decreased association with the Dfp1p subunit. The wild-type protein is found constitutively in the nucleus, and its localization is unaffected by treatment with HU or the absence of its substrate Mcm2p. In contrast, the mutant protein fails to localize appropriately, with reduced nuclear localization even under permissive conditions. This redistribution of Hsk1tsp may reflect abnormal protein structure or the inability of the protein to interact with a factor required for nuclear retention. However, it is unlikely that the redistribution of Hsk1tsp reflects its failure to interact correctly with Dfp1p, since wild-type Hsk1p remains nuclear throughout the cell cycle even though Dfp1p is present only transiently (this work and references 6 and 56).

A postinitiation role for Hsk1p.

Under restrictive conditions, hsk1ts mutant cells are severely delayed in S-phase progression and some cells show abnormal entry into mitosis, suggesting that they suffer a defect in the checkpoint that monitors DNA replication. At first glance, this possibility is consistent with observations of other mutants that block the cells prior to initiation of DNA synthesis, including rad4 (also called cut5) (14), orp1 (18), cdc18 (27), and pol1 (13) mutants. The failure of these mutants to restrain M phase is thought to indicate defects in assembly of replication structures that signal to the checkpoint apparatus, causing the cells to enter mitosis prematurely, without entering S phase (28). However, in contrast to these other mutants, some hsk1ts cells at the restrictive temperature show a single elongated cell body, with multiple DAPI-stained dots. This phenotype is distinct from the small, aneuploid cells of a typical cut mutant. Importantly, cellular elongation suggests that a cell cycle delay occurs prior to abnormal mitosis.

To probe the role of Hsk1p in later stages of DNA replication, we blocked hsk1ts cells in HU and then released them to the restrictive temperature. The cells completed DNA synthesis and underwent mitosis with apparently normal timing. This was expected; data from budding yeast show that replication forks originating from early-firing replication origins are sufficient to complete genome duplication in cdc7 mutants, even if late origins do not fire (5, 12). This result indicates that the initiation function of Hsk1p at early origins occurs prior to the HU block. However, although hsk1ts cells released from HU to the restrictive temperature completed DNA synthesis and entered mitosis with normal timing, that mitosis was severely disrupted, with a high fraction of cells exhibiting fragmented nuclei. Thus, when Hsk1p activity is lost during replication elongation, it affects mitotic progression, a phenotype not observed in budding yeast (5, 12). The execution point for this effect is subsequent to the HU block, which suggests two possibilities: either there is a second role for Hsk1p during normal S phase or there is a role for Hsk1p in recovery from the DNA replication block caused by HU treatment. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive.

Importantly, the phenotype upon HU treatment is similar to that observed in a fraction of cells when they were shifted to the restrictive temperature without a prior HU block. This result implies that the mitotic defect observed following HU treatment is not solely an effect of S-phase arrest but rather that it is enhanced due to the synchrony imposed by the HU block.

We posit that the nuclear fragmentation may reflect a defect in chromosome cohesion, which is established during S phase (53, 58). In support of this, we observed synthetic lethality between hsk1ts and the mitotic rad21ts cohesin. If the hsk1ts cells are unable to establish correct cohesion during S phase, this might prevent proper chromosome segregation at mitosis, resulting in the observed loss in nuclear integrity. Intriguingly, the cohesin is phosphorylated during S phase (2). Very recently, a novel DNA polymerase was shown to be required for both replication and cohesion in budding yeast, indicating a further connection between DNA replication and sister chromatid cohesion (61). Hsk1p may contribute directly to the establishment of cohesion, or it may carry out a more general function during DNA synthesis that affects chromosome segregation.

This evidence indicates a role for Hsk1p in maintaining genome integrity that may be separate from its role in replication initiation. Interestingly, we found that Chk1p checkpoint kinase is phosphorylated in hsk1ts cells even at the permissive temperature, indicating that the damage checkpoint is chronically activated in this strain. This chronic activation further suggests that defects in hsk1 cause genome damage even when the cells are able to divide and explains why the hsk1ts mutant requires the checkpoint kinases Rad3p and Chk1p for viability.

Hsk1p is a potential target of Cds1p.

The phenotypes that we observed in hsk1ts cells following prolonged exposure to HU are similar to the recovery defects observed for Δcds1 and Δrqh1 cells upon treatment with HU, which reflect the inability of the cells to restart S phase and complete a normal cell cycle after replication arrest. Moreover, the synthetic lethality between hsk1ts and Δrqh1 mutants indicates that Hsk1p is required for recovery from replication arrest in a pathway that is at least partially separate from that requiring Rqh1p.

Our experiments reveal interactions between Hsk1p and Cds1p both during a normal cell cycle and during replication arrest. We found that the temperature sensitivity of hsk1ts is partially suppressed by Δcds1 cells and, conversely, that hsk1ts cells are hypersensitive to overexpression of active, but not kinase-dead, Cds1p. Several replication mutants, such as DNA polymerase α, require cds1+ for viability (1), which makes the suppression of hsk1ts particularly unusual. This observation might indicate that Cds1p is modestly activated in the hsk1ts mutant because of its replication initiation defect, resulting in negative feedback which then further down-regulates Hsk1p activity. Alternatively, there may be a nonessential role for Cds1p in normal S phase in which it negatively regulates Hsk1p. Relief of Hsk1pts inhibition by the deletion of Cds1p would be permissive for growth at higher temperatures.

The Δcds1 hsk1 double mutant has noticeably more abnormal cells following HU treatment than those of either single mutant, indicating that while both genes operate in the response to HU, they are likely to affect at least partially separate pathways. We suggest that the defect in HU in the double mutant is due to two overlapping effects: the absence of a proper Cds1p response and the inability of the hsk1 mutant cells to carry out their late-S-phase function. These possibilities suggest that release from HU elicits multiple responses required to restart replication and maintain genome integrity.

The Hsk1p subunit in HU-treated wild-type cells undergoes phosphorylation that requires Cds1p. Using purified proteins, we determined that both wild-type and mutant Hsk1 proteins are direct substrates of Cds1p in vitro, even if the Hsk1p proteins are heat inactivated. However, the mutant Hsk1tsp is not detectably phosphorylated in vivo. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear, although a number of mechanisms, such as defects in mutant Hsk1p localization or defective interactions with other proteins, may account for the inability of Cds1p to mediate phosphorylation of Hsk1tsp in vivo. It is also formally possible that both Cds1p phosphorylation and Hsk1p autophosphorylation are required in order to detect a shift in Hsk1p mobility. Previous studies have shown that the Hsk1p regulatory subunit Dfp1p is also phosphorylated in a Cds1p-dependent manner in response to HU treatment (6, 56). Mutations in dfp1 confer sensitivity to HU and cause aberrant mitoses upon prolonged exposure to HU (56). Therefore, both subunits of the Hsk1 kinase may be direct substrates of Cds1 kinase and are elements of the response to S-phase arrest. These observations are consistent with models of budding yeast suggesting that RAD53 kinases prevent activation of late origins by regulating CDC7 and DBF4 kinases (29, 46, 51, 62).

Our investigation provides the first evidence that Hsk1p kinase is itself a potential Cds1p substrate, indicating that there are levels of regulation of Hsk1p not necessarily mediated by its association with Dfp1p. The requirement for Hsk1p activity after HU arrest and genetic interactions with Δrqh1 and rad21ts mutants in the absence of HU suggest that Hsk1p may function during S phase subsequent to origin firing. This second function may occur normally during replication and is required for successful recovery from replication arrest. Our data also provide evidence for the functional separation of the checkpoint kinases Chk1p and Cds1p, since deletion of each gene has opposite effects in hsk1ts cells. Additional genetic analysis under way should allow us to forge further ties between hsk1 and other components of the replication and repair pathways in fission yeast and to determine the role of hsk1 in the maintenance of genome integrity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Hisao Masai for strains and plasmids and discussion of unpublished work. We thank Tamar Enoch, Greg Freyer, Hisao Ikeda, Paul Russell, Shelley Sazer, Nancy Walworth, and Mitsuhiro Yanagida for strains and plasmids; Sally Pasion and Dan Sherman for plasmids; Tony Hunter for antibodies; and Jeff Hodson, John Marlett, and Andrew Waight for excellent technical assistance. We are also much indebted to Magdalena Bezanilla, Mike Catlett, Eliana Gomez, Joel Leverson, Debbie Liang, and Sally Pasion for their critical readings of the manuscript.

This work was supported by American Cancer Society grant RPG-00-132-01-CCG (S.L.F.) and Medical Research Council of Canada grant MOP-36360 (G.W.B.). H.A.S. was partly supported by The Salk Institute President's Club and the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation. We acknowledge the Dreyfus Foundation for their support. S.L.F. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. G.W.B. is a special fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhaumik D, Wang T S F. Mutational effect of fission yeast polymerase α on cell cycle events. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2107–2123. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkenbihl R P, Subramani S. The rad21 gene product of Schizosaccharomyces pombe is a nuclear, cell cycle-regulated phosphoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7703–7711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boddy M N, Russell P. DNA replication checkpoint control. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D841–D848. doi: 10.2741/boddy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodi Z, Gysler-Junker A, Kohli J. A quantitative assay to measure chromosome stability in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:77–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00264215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousset K, Diffley J F. The Cdc7 protein kinase is required for origin firing during S phase. Genes Dev. 1998;12:480–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown G W, Kelly T J. Cell cycle regulation of Dfp1, an activator of the Hsk1 protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8443–8448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown G W, Kelly T J. Purification of Hsk1, a minichromosome maintenance protein kinase from fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22083–22090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr A M. Control of cell cycle arrest by the Mec1(sc)/Rad3(sp) DNA structure checkpoint pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davey S, Han C S, Ramer S A, Klassen J C, Jacobson A, Eisenberger A, Hopkins K M, Lieberman H B, Freyer G A. Fission yeast rad12+ regulates cell cycle checkpoint control and is homologous to the Bloom's syndrome disease gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2721–2728. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demeter J, Morphew M, Sazer S. A mutation in the RCC1-related protein pim1 results in nuclear envelope fragmentation in fission yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1436–1440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dohrmann P R, Oshiro G, Tecklenburg M, Sclafani R A. RAD53 regulates DBF4 independently of checkpoint function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:965–977. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson A D, Fangman W L, Brewer B J. Cdc7 is required throughout the yeast S phase to activate replication origins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Urso G, Grallert B, Nurse P. DNA polymerase α, a component of the replication initiation complex, is essential for the checkpoint coupling S phase to mitosis in fission yeast. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:3109–3118. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.9.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenech M, Carr A M, Murray J, Watts F Z, Lehmann A R. Cloning and characterization of the rad4 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe; a gene showing short regions of sequence similarity to the human XRCC1 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6737–6741. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsburg S L, Sherman D A. General purpose tagging vectors for fission yeast. Gene. 1997;191:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furnari B, Blasina A, Boddy M N, McGowan C H, Russell P. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:833–845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould K L, Burns C G, Feoktistova A, Hu C P, Pasion S G, Forsburg S L. Fission yeast cdc24+ encodes a novel replication factor required for chromosome integrity. Genetics. 1998;149:1221–1233. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grallert B, Nurse P. The ORC1 homolog orp1 in fission yeast plays a key role in regulating onset of S phase. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2644–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanks S K, Hunter T. Protein kinases. 6. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification. FASEB J. 1995;9:576–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy C F, Dryga O, Seematter S, Pahl P M, Sclafani R A. mcm5/cdc46-bob1 bypasses the requirement for the S phase activator Cdc7p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3151–3155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hua X H, Newport J. Identification of a preinitiation step in DNA replication that is independent of origin recognition complex and cdc6, but dependent on cdk2. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:271–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jallepalli P V, Brown G W, Muzi-Falconi M, Tien D, Kelly T J. Regulation of the replication initiator protein p65cdc18 by CDK phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2767–2779. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston L H, Masai H, Sugino A. First the CDKs, now the DDKs. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kearsey S E, Labib K. MCM proteins: evolution, properties, and role in DNA replication. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1398:113–136. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keeney J B, Boeke J D. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1994;136:849–856. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly, T. J., and G. W. Brown. Replication in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem., in press.

- 27.Kelly T J, Martin G S, Forsburg S L, Stephen R J, Russo A, Nurse P. The fission yeast cdc18+ gene product couples S phase to START and mitosis. Cell. 1993;74:371–382. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90427-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly T J, Nurse P, Forsburg S L. Coupling DNA replication to the cell cycle. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:637–644. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Weinert T A. Characterization of the checkpoint gene RAD53/MEC2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:735–745. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970630)13:8<735::AID-YEA136>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitada K, Johnston L H, Sugino T, Sugino A. Temperature sensitive cdc7 mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae are suppressed by the DBF4 gene, which is required for the G1/S cell cycle transition. Genetics. 1992;131:21–29. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landis G, Tower J. The Drosophila chiffon gene is required for chorion gene amplification, and is related to the yeast Dbf4 regulator of DNA replication and cell cycle. Development. 1999;126:4281–4293. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leatherwood J. Emerging mechanisms of eukaryotic DNA replication initiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:742–748. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lei M, Kawasaki Y, Young M R, Kihara M, Sugino A, Tye B K. Mcm2 is a target of regulation by Cdc7-Dbf4 during the initiation of DNA synthesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3365–3374. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang D T, Hodson J A, Forsburg S L. Reduced dosage of a single fission yeast MCM protein causes genetic instability and S phase delay. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:559–567. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsay H D, Griffiths D J, Edwards R J, Christensen P U, Murray J M, Osman F, Walworth N, Carr A M. S-phase-specific activation of Cds1 kinase defines a subpathway of the checkpoint response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 1998;12:382–395. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masai H, Miyake T, Arai K-I. hsk1+, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC7, is required for chromosomal replication. EMBO J. 1995;14:3094–3104. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masai H, Sato N, Takeda T, Arai K. CDC7 kinase complex as a molecular switch for DNA replication. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D834–D840. doi: 10.2741/masai. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murakami H, Okayama H. A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature. 1995;374:817–819. doi: 10.1038/374817a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray J M, Lindsay H D, Munday C A, Carr A M. Role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ homolog, recombination, and checkpoint genes in UV damage tolerance. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6868–6875. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okishio N, Adachi Y, Yanagida M. Fission yeast nda1 and nda4, MCM homologs required for DNA replication, are constitutive nuclear proteins. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:319–326. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasion S G, Forsburg S L. Nuclear localization of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mcm2/Cdc19p requires MCM complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4043–4057. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose M D, Fink G R. KAR1, a gene required for function of both intranuclear and extranuclear microtubules in yeast. Cell. 1987;48:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russell P. Checkpoints on the road to mitosis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:399–402. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santocanale C, Diffley J F. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature. 1998;395:615–618. doi: 10.1038/27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarabia M-J F, McInerny C, Harris P, Gordon C, Fantes P. The cell cycle genes cdc22+ and suc22+ of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe encode the large and small subunits of ribonucleotide reductase. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;238:241–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00279553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sclafani R A. Cdc-7p-Dbf4p becomes famous in the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2111–2117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shellman Y G, Schauer I E, Oshiro G, Dohrmann P, Sclafani R A. Oligomers of the Cdc7/Dbf4 protein kinase exist in the yeast cell. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;259:429–436. doi: 10.1007/s004380050833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman D A, Pasion S G, Forsburg S L. Multiple domains of fission yeast Cdc19p (MCM2) are required for its association with the core MCM complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1833–1845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shirahige K, Hori Y, Shiraishi K, Yamashita M, Takahashi K, Obuse C, Tsurimoto T, Yoshikawa H. Regulation of DNA-replication origins during cell-cycle progression. Nature. 1998;395:618–621. doi: 10.1038/27007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski R S, Boeke J D. In vitro mutagenesis and plasmid shuffling: from cloned gene to mutant yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:302–318. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skibbens R V, Corson L B, Koshland D, Hieter P. Ctf7p is essential for sister chromatid cohesion and links mitotic chromosome structure to the DNA replication machinery. Genes Dev. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snaith H A, Forsburg S L. Re-replication phenomenon in fission yeast requires MCM proteins and other S phase genes. Genetics. 1999;152:839–851. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart E, Chapman C R, Al-Khodairy F, Carr A M, Enoch T. rqh1+, a fission yeast gene related to the Bloom's and Werner's syndrome genes, is required for reversible S phase arrest. EMBO J. 1997;16:2682–2692. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeda T, Ogino K, Matsui E, Cho M K, Kumagai H, Miyake T, Arai K, Masai H. A fission yeast gene, him1+/dfp1+, encoding a regulatory subunit for hsk1 kinase, plays essential roles in S-phase initiation as well as in S-phase checkpoint control and recovery from DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5535–5547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tatebayashi K, Kato J, Ikeda H. Isolation of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad21ts mutant that is aberrant in chromosome segregation, microtubule function, DNA repair and sensitive to hydroxyurea: possible involvement of Rad21 in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Genetics. 1998;148:49–57. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toth A, Ciosk R, Uhlmann F, Galova M, Schleiffer A, Nasmyth K. Yeast cohesin complex requires a conserved protein, Eco1p(Ctf7), to establish cohesion between sister chromatids during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 1999;13:320–333. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walworth N, Davey S, Beach D. Fission yeast chk1 protein kinase links the rad checkpoint pathway to cdc2. Nature. 1993;363:368–371. doi: 10.1038/363368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Walworth N C, Bernards R. rad-dependent response of the chk1-encoded protein kinase at the DNA damage checkpoint. Science. 1996;271:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Z, Castaño I B, De Las Peñas A, Adams C, Christman M F. Pol κ: a DNA polymerase required for sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2000;289:774–779. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinreich M, Stillman B. Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase binds to chromatin during S phase and is regulated by both the APC and the RAD53 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:5334–5346. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]