Abstract

Time spent in the antenatal clinic (ANC) is a major disincentive for pregnant women and constitutes a barrier to the utilization of ANC. Long waiting time and poor patient satisfaction may contribute to poor utilization. This study assessed waiting time, patients’ satisfaction, and preference for staggered ANC appointments. A cross-sectional study was conducted; information obtained includes sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics, and time spent at ANC service points. Data were analyzed using International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Products and Service Solutions (SPSS) software version 23. Descriptive statistics and chi-square test were conducted. Level of significance: P < .05. One hundred and twenty-two participants were interviewed. Mean age was 30.52 (±4.65) years, they were mostly multi-gravid, married, and with tertiary education. Mean time spent in ANC and waiting time were 191 min and 143 min, respectively. Waiting time was longest at doctor's consultation (59 min), laboratory services (38 min), and the cash pay-point (18 min). About 68.9% were satisfied with services and highest at doctors’ consultation. Satisfaction was associated with waiting time of <45 min. Dissatisfaction was high at the cash pay-point (28.7%), followed by the laboratory (16.4%). About 56.5% preferred staggered appointments. Time spent in ANC should be reduced and staggered appointments may be a useful strategy to reduce waiting time and patient load.

Keywords: antenatal waiting time, patient satisfaction, staggered antenatal appointment

Introduction

Antenatal care is an important part of healthcare delivery for improving pregnancy outcomes to prevent maternal morbidity and mortality (1). According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM),there are six identified fundamental aims for health care service delivery which include safe, efficient, patient-centered, equitable, timely, and effective. However, timeliness is the least well studied and understood among these aims (2).

“Waiting time refers to the time a patient waits in the clinic before being seen by one of the clinic medical staff”(3) and it is recommended that at least 90% of patients should receive medical care within 30 min of their scheduled appointment time (4). Wait times to see physicians are a source of potential frustration and dissatisfaction with care quality as well as lost productivity for individual patients (5). Currently, time-specific appointments are not the usual practice in outpatient clinics including general and ANC in Nigeria. As such, patients seeking care arrive early at the health facility. Consequently, patients are likely to wait for the commencement of the antenatal care service and doctor's consultation. The causal consequence of delayed commencement of consultations is that the physicians become overwhelmed with the pool of patients while the patients are made to wait longer before being attended to by the physician (6).

Patients’ satisfaction is related to the extent to which general health care needs and condition-specific needs are met (7,8). The assessment of antenatal care is commonly based on the assessment of the components and quality of services received (7,9–14). In recent times, in the assessment of the quality of healthcare, it has become increasingly important to include client's satisfaction as a parameter; hence, healthcare facility performance can be best assessed by measuring the level of patient's satisfaction in addition to other components of quality care (15). However, it is a wholly subjective assessment of the quality of health care and as such, is not a measure of the final outcome (16). Available studies have shown that the outcome of patients’ response to their care is not solely dependent on waiting time but also on policies put in place to maximize patients’ satisfaction (8,9).

Evidence has suggested that patients who are not satisfied with the care received are less likely to comply with treatment instructions; more likely to delay seeking further care and have a poor understanding and retention of medical information (16). There is an inverse relationship between waiting time and patients’ satisfaction (17). Long waiting time in clinics is associated with dissatisfaction and may lead to non- or poor use of antenatal care. Previous studies by Oladapo et al. and Ahmad et al., demonstrated that patients expected to see the doctor within 30 min and were less dissatisfied if waiting time was less than 30 min, respectively (18,19). Short waiting time in ANC is more acceptable to pregnant women, and it will make maternal health services more efficient and prevent overcrowding. In the face of contagious diseases, short waiting times and prompt services will reduce patients’ contact, crowding, and disease spread. Identifying the points of delay in service delivery is the first step in addressing the challenge of long waiting times in the clinics. It will also provide appropriate data for decision-making and policy change. Therefore, there is a need to understand the antenatal care users’ experiences, including their perceptions, preferences, and satisfaction levels as this can substantially influence the degree to which women accept interventions, comply, and continue to use the services provided (20). In the Nigerian demographic health survey 2018, concerning antenatal care coverage, about 67% of women that gave birth in the preceding 5 years received antenatal care from a skilled birth attendant and only 42% of women received postnatal care (21). These statistics are worrisome when compared to other countries. The quality of care, time spent, and women's satisfaction may impact maternal healthcare utilization. It is important to identify and minimize the effects of the modifiable factors.

This study is aimed at assessing the waiting time, factors affecting waiting in the ANC and assessing pregnant women's satisfaction with services rendered in the ANC.

Methodology

This study was a prospective cross-sectional study among pregnant women receiving antenatal care. It was conducted at the Antenatal Clinic of the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria among pregnant women presenting for routine antenatal care during the study period.

All pregnant women consecutively presenting for their routine antenatal visit were counseled and invited to participate in the study. Eligible consenting pregnant women were enrolled in the study. The exclusion criteria included pregnant women presenting for emergency care, pregnant women attending ANC for the first time—booking clinic visit (as this takes longer than subsequent clinics),and pregnant women who are members of staff/spouses of male staff at the hospital.

A purposive sampling technique was employed to enroll a total of 122 pregnant women in the study.

Eligible pregnant women were identified on arrival at the clinic and counseled about the purpose of the study and the extent of their involvement in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment into the study. After enrolment, the participants were followed to the different service points by trained observers who are not known to the service providers as observers. The observers were medical trainees who were attending the clinics as part of their clerkship. The trainees are expected to rotate around the different clinicians and sign-up antenatal care services into the logbooks, so it was not unusual for them to move around the clinicians and service points. The service providers were not aware that they were collecting data in the period. The trainees ensured that they were not identified as “observers” by the staff at the various service points, and observers did not stand close to the pregnant women; the activities at the service points were observed and relevant details documented. The observers were trained on the steps of data collection and instructed not to interfere with the ANC activities as they followed the participants.

The antenatal care clinic activities routinely start with patient check-in and presentation of the medical record appointment tracer card at the medical records section of the clinic for retrieval of medical case records of the patient. Patients’ medical records are documented as hard copy files. Thereafter, the patient proceeds to complete other activities which include health education session, blood work—packed cell volume (PCV), urine analysis, blood pressure assessment, weight check, and tetanus toxoid immunization. Malaria parasite test and obstetric ultrasound evaluation are done if it is indicated. The patients then return to the waiting area to await consultation with the obstetricians. All of these activities take place within the ANC complex. The patients are also required to make payment at the cashpoint or present at the health insurance office for clearance, if they are on health insurance.

Definition of terms:

Check-in time—time the patient arrives at the ANC.

Arrival time—the time at which a patient reaches a service point.

Time of onset—this is the time a service or procedure begins at the service point.

Completion time—the time at which a service or procedure ends.

Procedure time—time taken to perform the procedure at the service point.

Waiting time—time spent at a service point before the procedure or service begins.

Departure time was the time at which a patient leaves one service point for another.

Queue size—number of patients waiting at the service point.

Checkout time—time the patient leaves the ANC.

Data were collected using a pretested, semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire—data collection form. The information collected included the sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics, the time of arrival at the clinic, the time of arrival at each service point, time of commencement, and completion of procedures at different service points, waiting time, transit time, and the queue size on arrival at each of the service points and departure time. The service points assessed include cashier or the health insurance unit (as applicable), health education hall, laboratory, urine analysis, blood pressure, and weight checking sections. The study also assessed patient satisfaction with the waiting time and preference for staggered appointments.

The data were entered into the computer and analyzed using statistical software—International Business Machines (IBM) Statistical Products and Service Solutions (SPSS) software version 23. Descriptive statistics were done using univariate analysis of mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and bivariate analysis using chi-square test. The level of significance was set at P < .05.

The outcome measures included total waiting time in the clinic and each service point, patient satisfaction, and preference for staggered clinic appointments. The explanatory variables were factors affecting ANC waiting time.

Results

This study assessed waiting time, satisfaction with antenatal care services, and preference for staggered appointments among pregnant women; and 122 participants were interviewed during the study period. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents. The mean age of the respondents is 30.52 (±4.65) years and they were predominantly of tertiary (postsecondary) level of education (92.6%). A majority (54.9%) of the participants had registered in the second trimester and only 30.3% of the women had received antenatal care in UCH in a previous pregnancy.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characteristics of the Respondents.

| Variables | Frequency (n) n = 122 | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | ||

| 20–24 | 9 | 7.4 |

| 25–29 | 40 | 32.8 |

| 30–34 | 51 | 41.8 |

| 35–39 | 18 | 14.8 |

| 40–43 | 4 | 3.3 |

| Educational status | ||

| None/primary | 1 | 0.8 |

| Secondary | 8 | 6.6 |

| Postsecondary | 113 | 92.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Engaged | 1 | 0.8 |

| Married | 121 | 99.2 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 86 | 70.5 |

| Islam | 36 | 29.5 |

| Tribe | ||

| Yoruba | 106 | 86.9 |

| Hausa | 2 | 1.6 |

| Igbo | 9 | 7.4 |

| Others | 5 | 4.1 |

| Parity | ||

| 0–1 | 97 | 79.5 |

| 2–4 | 24 | 19.7 |

| >4 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Trimester of pregnancy at booking | ||

| First | 47 | 38.5 |

| Second | 67 | 54.9 |

| Third | 8 | 6.6 |

| Number of antenatal visits | ||

| 1–4 | 67 | 54.9 |

| >4 | 55 | 45.1 |

| Previous antenatal care in UCH | ||

| Yes | 37 | 30.3 |

| No | 85 | 69.7 |

The time spent and procedure time at various service points are shown in Table 2. The longer waiting times and queue size were observed at the doctors’ consultation, laboratory unit, and cash pay-points.

Table 2.

Time Spent and Queue Size at Service Points in Antenatal Clinic (ANC).

| Variables | Antenatal care service points | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Records | Cashier | Health Education | Blood Pressure | Weight | Laboratory—PCV | Urinalysis | Nurses’ Record | Doctor's Consultation | NHIS | |

| Mean waiting time for procedure (minutes) (SD) | < 1 min | 18 min 4 s | 5 min 20 s | 8 min 9 s | 4 min 5 s | 38 min 14 s | 4 min 12 s | 3 min 31 s | 59 min 22 s | 1 min 23 s |

| 4 min 26 s | 26 min 29 s | 10 min 42 s | 6 min 51 s | 3 min 74 s | 28 min 41 s | 8 min 59 s | 7 min 3 s | 41 min 20 s | 2 min 59 s | |

| Procedure time (minutes) Mean SD | 3 min 33 s | 4 min 29 s | 31 min 35 | 1 min 12 s | 25 s | 1 min 23 s | 45 s | 1 min 14 s | 13 min 46 s | <1 |

| 14 min 17 | 11 min 19 s | 18 min 15 s | 39 s | 46 s | 1 min 30 s | 52 s | 4 min 46 s | 12 min 16 s | 2 min 21 s | |

| Mean queue size (SD) | 1 (2) | 8 (12) | 0 (1) | 7 (5) | 7 (6) | 23 (21) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 4(4) | 1 (1) |

min: minutes; NHIS: National Health Insurance Scheme; PCV: packed cell volume; s: seconds.

The mean time spent in the clinic was 191 min 26 s (±45 m 27 s) while the mean waiting time in the ANC was 143 min 6 s (±63 m 17 s). Among the respondents, 68.9% were satisfied with antenatal care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total Time Spent, Total Time Waiting Time, and Patient Satisfaction at the Antenatal Clinic (ANC).

| Variables | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Mean total time spent in antenatal clinic | 191 min 26 s | ± 45 min 27 s |

| Mean total waiting time in antenatal clinic | 143 min 6 s | ± 63 min 17 s |

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Satisfaction with antenatal services | ||

| Yes | 84 | 68.9 |

| No | 43 | 27.9 |

| Indifferent | 4 | 3.3 |

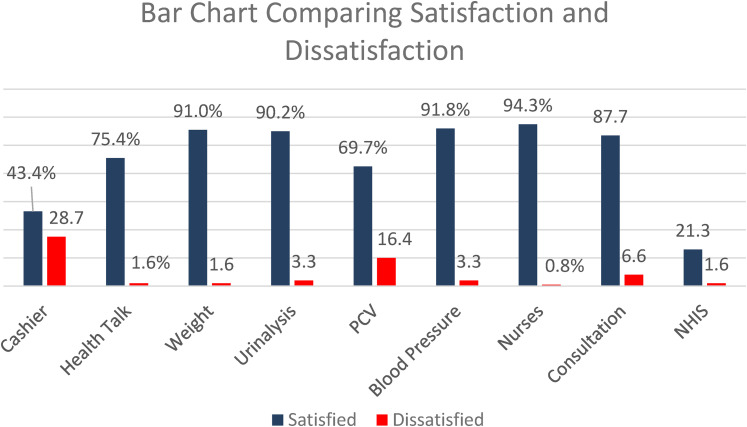

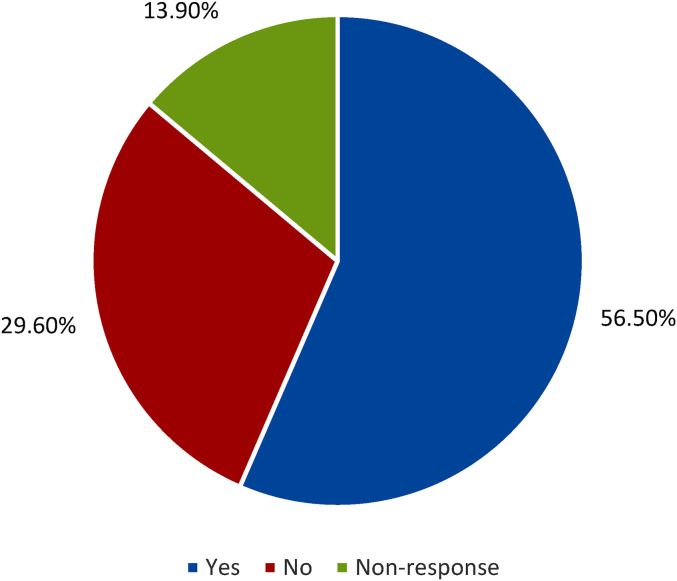

Patients’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with antenatal care services and waiting time are shown in Figure 1. Dissatisfaction with service was experienced at the cashpoint and the laboratory—PCV service. Among the pregnant women, 65 (56.5%) preferred staggered appointments (Figure 2). Promptness of services, convenience, the anticipation of unhurried consultation with the doctor, the ability to plan for an estimated duration to be spent in the hospital, time conservation, minimal time-wasting, improved quality of care, benefit to pregnant women coming from far locations, reduced stress, reduce time lost from their businesses and other schedules for the day, and reduction in queue size at service points were the reasons given by the pregnant women for preference of staggered appointments.

Figure 1.

Bar chart comparing levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

Figure 2.

Pie chart showing preference for staggered antenatal clinic (ANC) appointments.

Patients’ satisfaction was not significantly associated with wait time; P = .078 (Table 4). It was observed that the waiting time at the service points in the ANC was influenced by inadequate staff and long queue size at service points, queue shunting by other patients; delay at the pay-point, assistance being rendered to patients who knew the staff at service points. To overcome the delays encountered in the ANC, some pregnant women leave the ANC to use other pay-points within the hospital; and some of the pregnant women did the required antenatal investigations before the clinic appointment.

Table 4.

Factors Associated with Patients' Satisfaction.

| Variables | Patients’ Satisfaction | P-value (Fishers’ exact test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Indifferent | ||

| Waiting time (minutes) | ||||

| < 45 | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | .078 |

| ≥ 45 | 81 (96.4) | 34 (100) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Total time spent in clinic | ||||

| <120 | 5 (6.0) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | >.999 |

| ≥120 | 79 (94.0) | 32 (94.1) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| Employee | 42 (50.0) | 16 (47.1) | 2 (50.0) | .939 |

| Self-employed | 42 (50.0) | 18 (52.9) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Number of antenatal care visits | ||||

| 1– | 43 (51.2) | 22 (64.7) | 2 (50.0) | .383 |

| >4 | 41 (48.8) | 12 (35.3) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Previous ANC in UCH | ||||

| Yes | 28 (33.3) | 9 (26.5) | 0 (0) | .351 |

| No | 56 (66.7) | 25 (73.5) | 4 (100.0) | |

*Fisher's exact test.

ANC: antenatal care.

Discussion

This study highlights the delay experienced during ANC visits and healthcare service points contributing to the delay.

The main finding of this study was that the mean time spent during ANC visits was over 3 h and the mean wait time in ANC was more than 2 h. Majority of the women preferred staggered ANC appointments; expressed the desire and perceived benefits of the strategy in the care of the pregnant women.

The total time spent, long wait times, and delays in the ANC are major disincentives for pregnant women. About half of the women spent more than the average total time in ANC. The service points where delays were mostly encountered include cash payment point, PCV laboratory, and consultation, with larger queue size at the first two places. These were similar to findings in the study by BA Ahmad et al. and Nwaeze et al. (19,22) The time spent on the ANC procedures is quite negligible; whereas, the procedures were preceded by huge delays created by the waiting time for the procedures. The mean total time spent in ANC in this study is longer than the findings of Esimai et al., where the total time spent in the clinic was 162 min. (1) Wait time (143 min) is higher than wait time of 90 min in public clinics reported by Jallow et al. from a study conducted in Gambia (23). Inadequate staffing at the various service units, possibly poor planning, long waiting time at doctor's consultation, and poor staff deployment to busy service points in the ANC may explain the delay and difference observed in this study.

More than two-thirds of the pregnant women were satisfied with the antenatal care services. This is higher than 56.7% reported in Malaysian by Pitaloka et al. (8) and lower than 81.4% reported in Nigeria by Oladapo et al. (18) Satisfaction was not associated with shorter wait time (<45 min) at ANC. However, in a previous study, Oladapo et al. reported that about 43.3% in that study expected to be seen within 30 min of arrival at the clinic (18). Also, in this study, the respondents’ level of education and occupation were not associated with satisfaction with antenatal care. This differs from the findings of Nwaeze et al. where more professionals were satisfied with the totality of ANC services (22). Although there was longer waiting time for consultation, respondents expressed a high level of satisfaction compared to the cashpoint which equally had a long wait time but respondents had the highest level of dissatisfaction with the services. The shunting of the queue by clients who were known to staff members may have contributed to the level of dissatisfaction at this point. Furthermore, dissatisfaction with antenatal care services and time spent during the clinic visit may be lead pregnant women to default from the clinic thus missing out on quality prenatal and delivery care.

The preference of staggered appointments as a strategy to reduce long wait time at the clinic was evaluated. More than half of the respondents also preferred a staggered appointment and perceived it as a means to reduce the time spent in the clinic in addition to other benefits stated. It is interesting to note that women will like to have staggered appointments to reduce time spent and waiting time in clinics, yet many ANC in our environment are yet to adopt the schedule and change the current practice. It is possible that this might be due to the longer hours that staff might have to spend at the work point, and that some services

Prolonged waiting time and time spent in clinics is neither peculiar to ANC nor developing countries only. It is unacceptable and there must be concerted efforts to address this challenge. Similar findings of prolonged wait time have been reported from studies done in outpatient clinics. Two studies conducted in the general outpatient clinics in Nigeria by Oche et al. and Umar et al. showed similar findings (24,25). Delays in clinic and long waiting time were also demonstrated by studies done in other countries such as Malaysia and Australia by Pitaloka et al. and Lucas et al. respectively (8,26).

It is imperative to increase the doctor-patient ratio to reduce consultation waiting time. The adequate deployment of health care providers for antenatal care has been demonstrated to improve the quality of antenatal and delivery care and reduce maternal mortality ratio (27). There is a need to train staff or give orientation to health workers on the need to reduce patient waiting time in addition to the importance of courtesy and politeness to patients in antenatal care service delivery. The pregnant women should also be given orientation at ANC booking visits to ease patients’ flow at subsequent ANC visits. Color-coded flow tags may also be used to guide patients through the clinic routines. The use of recorded and regularly updated health talks at the waiting lounge of the clinic can minimize time spent on health talk and be of benefit to women who may have missed the health talk. This will also engage the pregnant women while waiting for consultation and other services.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size, which may be too small to determine the factors associated with patient satisfaction. There could also have been overlapping waiting time due to the fact that respondents had to access other services while waiting in line at certain service points.

Conclusion

The findings of this study have provided the information about the current status of antenatal care services in terms of service delivery, time spent, factors contributing to delays, and possible solutions. It is important to address the prolonged waiting time and time spent in ANC to improve the quality of care, level of patients’ satisfaction, and encourage the use of antenatal care by future clients. The cash payment points, laboratory, and doctors’ consultation need to be restructured to make these services more efficient. The introduction of staggered antenatal appointments will address some of the factors responsible for prolonged wait time such as patient load and large queue size at service points by reducing waiting time. This should be complemented by reminders to make it efficient and reduce patients canceling without notice or arriving late for appointments, which will defeat the purpose. Adequate deployment of health workers and support staff to each service point is important for efficient service delivery. Setting up parallel service points will also accelerate the rate of service delivery in the ANC and ultimately reduce queues and time spent.

Acknowledgments

Medical students Group A 2016.

Author Biographies

RA Abdus-salam is a lecturer/consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist at the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo State Nigeria. Obstetrician and Gynaecologist with interests in General obstetrics and gynaecology, Urogynaecology and clinical epidemiology.

AA Adeniyi is a senior registrar in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University College Hospital, Ibadan with interests in General Obstetrics and Gynaecology and assisted conception.

FA Bello is an associate professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo State Nigeria. Obstetrician and Gynaecologist with interests in General Obstetrics and Gynaecology, assisted conception and infertility research.

Footnotes

Author's Contribution: Abdus-salam RA (RA)—design, planning, conduct, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Adeniyi AA (AA)—planning and manuscript writing.

Bello FA (FAB)—design, planning, conduct, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the institutional ethics Review Committee of University College Hospital and the College of Medicine, University of Ibadan (UI/UCH Ethics committee—UI/EC/20/0372). Voluntary and informed consent of the participants was obtained.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the UI/UCH Ethics committee—UI/EC/20/0372 approved protocol.

Statement of Informed Consent: All participants in this study gave voluntary informed consent.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: RA Abdus-salam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2226-0597

References

- 1.Esimai OA, Omoniyi-Esan GO. Wait time and service satisfaction at Antenatal Clinic, Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife. East Afr J Public Health. 2009 Dec;6(3):309-11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20803925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington DC: National Academies Press (US); 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossiter C, Raynolds F. Automatic monitoring of the time waited in an outpatient department. J Storage Med Care. 1963;1(4):218-25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’malley MS, Fletcher SW, Fletcher RH, Earp JA. Measuring patient waiting time in a practice setting: a comparison of methods. J Ambul Care Manage. 1983;6(3):20-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oostrom T, Einav L, Finkelstein A. Outpatient office wait times And quality Of care For medicaid patients. Health Aff. 2017 May;36(5):826-32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28461348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogunfowokan O, Muhammad M. Time, expectation and satisfaction: patients’ experience at National Hospital Abuja, Nigeria. Afr J Prm Heal Care Fam Med. 2012;4(1):398. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakew S, Ankala A, Jemal F. Determinants of client satisfaction to skilled antenatal care services at southwest of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional facility based survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018 Dec;18(1):479. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-2121-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitaloka SD, Rizal AM. Patient's satisfaction in Antenatal Clinic Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. J Community Health. 2006;12(1):1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onyeajam DJ, Xirasagar S, Khan MM, Hardin JW, Odutolu O. Antenatal care satisfaction in a developing country: a cross-sectional study from Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim SM, Bakari M, Abdullahi HU, Bukar M. Clients’ perception of antenatal care services in a tertiary hospital in North Eastern Nigeria. Int J Reprod Contraception, Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(10):4217. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ismail N, Ismail AA, Essa RM. Pregnant Women's Satisfaction with the quality of antenatal care at maternal and child health centers in El-Beheira governorate. IOSR J Nurs Heal Sci. 2017; 6(2):36-46. Available from: www.iosrjournals.org [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetui M, Kiracho Ekirapa E, Bua J, Mutebi A, Tweheyo R, Waiswa P. Quality of antenatal care services in eastern Uganda: implications for interventions. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:27. Available from: www.panafrican-med-journal.com [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES. Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015 Apr;15(1):95. Available from: http://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-015-0527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do M, Wang W, Hembling J, Ametepi P. Quality of antenatal care and client satisfaction in Kenya and Namibia. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2017 Apr;29(2):183-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28453821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Net NY, Sermsri, S., & Chompikul, J. Patient satisfaction with health services at the out-patient department clinic of Wangnumyen community hospital, Sakaeo Province, Thailand. 2007. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268062280_Patient_Satisfaction_with_Health_Services_at_the_Out-Patient_Department_Clinic_of_Wangmamyen_Community_Hospital_ Sakeao_Province_Thailand

- 16.Wilkin D, Hallam L, Doggett M-A. Measures of need and outcome for primary health care. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassali MA, Alrasheedy AA, Razak BAA, Al-Tamimi SK, Saleem F, Haq NU, et al. Assessment of general public satisfaction with public healthcare services in Kedah, Malaysia. Australas Med J. 2014;7(1):35-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oladapo OT, Iyaniwura CA, Sule-Odu AO. Quality of antenatal services at the primary care level in southwest Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12(3):71-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad BA, Khairatul K, Farnaza A. An assessment of patient waiting and consultation time in a primary healthcare clinic. Malaysian Fam Physician. 2017;12(1):14-21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawole AO, Okunlola MA, Adekunle AO. Clients’ perceptions of the quality of antenatal care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008 Sep;100(9):1052-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18807434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF; 2019. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwaeze IL, Enabor OO, Oluwasola TAO, Aimakhu CO. Perception and satisfaction with quality of antenatal care services among pregnant women at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Ibd Pg Med. 2013;11(1):22-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4111061/pdf/AIPM-11-22.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jallow IK, Chou Y-J, Liu T-L, Huang N. Women's perception of antenatal care services in public and private clinics in the Gambia. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2012 Dec;24(6):595-600. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/intqhc/mzs033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adamu H, Oche M. Determinants of patient waiting time in the general outpatient department of a tertiary health institution in North Western Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(4):588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O OM, S UA. Patient waiting time in a tertiary health institution in Northern Nigeria. J Public Heal Epidemiol. 2011;3(2):78-82. Available from: http://www.academicjournals.org/jphe [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucas C, Charlton K, Brown L, Brock E, Cummins L. Review of patient satisfaction with services provided by general practitioners in an antenatal shared care program. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(5):317-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okonofua F, Ntoimo L, Ogu R, Galadanci H, Abdus-Salam R, Gana M, et al. Association of the client-provider ratio with the risk of maternal mortality in referral hospitals: a multi-site study in Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]