Abstract

The parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands represent a trio of oral secretory glands whose primary function is to produce saliva, facilitate digestion of food, provide protection against microbes, and maintain oral health. While recent studies have begun to shed light on the global gene expression patterns and profiles of salivary glands, particularly those of mice, relatively little is known about the location and identity of transcriptional control elements. Here we have established the epigenomic landscape of the mouse submandibular salivary gland (SMG) by performing chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing experiments for 4 key histone marks. Our analysis of the comprehensive SMG data sets and comparisons with those from other adult organs have identified critical enhancers and super-enhancers of the mouse SMG. By further integrating these findings with complementary RNA-sequencing based gene expression data, we have unearthed a number of molecular regulators such as members of the Fox family of transcription factors that are enriched and likely to be functionally relevant for SMG biology. Overall, our studies provide a powerful atlas of cis-regulatory elements that can be leveraged for better understanding the transcriptional control mechanisms of the mouse SMG, discovery of novel genetic switches, and modulating tissue-specific gene expression in a targeted fashion.

Keywords: salivary glands, ChIP-sequencing, histone modification, gene expression, epigenomics, regulatory regions

Introduction

Among the various tissues and organs of an organism, salivary glands (SGs) occupy a unique niche due to their functional specialization to generate and secrete saliva into the oral cavity. Indeed, the source of saliva in mammals comes from 3 major pairs of salivary glands—the parotid gland (PG), submandibular gland (SMG), and sublingual gland (SLG)—as well as numerous minor salivary glands. Collectively, these glands function to generate, process, and secrete saliva, which is a vital lubricant necessary to aid in food digestion, provide defense against microbes, and maintain oral health (Maruyama et al. 2019). The 3 SGs share similar as well as unique cellular features and functional attributes that arise from carefully crafted and dynamic developmental and maturation programs (Porcheri and Mitsiadis 2019). Recent studies fueled by the power of next-generation sequencing technologies have offered a global view of the transcriptional landscape that underlies these programs and, in turn, have identified important regulators of SG biology in mice (Gluck et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2018; Mukaibo et al. 2019; Oyelakin et al. 2019). This is very well exemplified by single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies of both embryonic and adult SGs that have begun to uncover the diverse nature of the various cellular populations that inhabit the SGs and their molecular identities as defined by gene expression profiles (Song et al. 2018; Oyelakin et al. 2019; Hauser et al. 2020; Min et al. 2020; Sekiguchi et al. 2020).

Understanding how this tissue-specific gene expression pattern is established and maintained in the SG is critical for uncovering the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation, organ development, cell identity, and function (Michael et al. 2019). Toward this end, genome-wide identification and characterization of regulatory elements such as promoters and enhancers, especially active enhancers that display tissue specificity, can serve as a crucial first step (Heinz et al. 2015). This can be achieved by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), to profile tell-tale histone modifications such as those that occur on lysine residues. It is now well established that specific histone modifications serve as an epigenomic beacon that can inform on states of transcriptional activation or repression (Zhu et al. 2013). For instance, histones flanking active enhancer regions are found to be marked by H3K4me1 and H3K27ac modifications (Heinz et al. 2015). Similarly, some enhancers with high levels of H3K27ac are often found to be clustered together as super-enhancers, which are thought to bestow high transcriptional activity and control the expression of master genes that drive cell lineages (Hnisz et al. 2013; Whyte et al. 2013).

The location and identity of cis-regulatory elements such as enhancers and the principles by which broad gene expression patterns are established in the SGs remain understudied. To address this knowledge gap, here we have focused on the genome-wide identification and characterization of cis-regulatory elements of the murine SMG by performing ChIP-seq experiments for histone modifications that are associated with diverse gene regulatory elements. Our primary objectives of this study were to identify 1) different subtypes of enhancers that are likely to drive SMG-specific expression of genes and 2) to predict the corresponding transcription factors (TFs) that can be expected to bind to such regulatory regions by virtue of their high expression levels and preference for cognate DNA binding sites. These studies have allowed us to catalog the location and identity of gene regulatory elements, particularly those marking typical enhancers and super-enhancers, at an unprecedented genomic scale. Follow-up clustering of the epigenomic data of the SMGs and other mouse tissues and integration with RNA-seq data have unearthed interesting molecular players such as TFs that are enriched and relevant for SMG biology. Specifically, our analysis revealed an unappreciated role for the Fox family of TFs, specifically Foxc1, in potentially governing gene expression in the SMG. The epigenomic atlas reported here complements recently generated gene expression data sets for discovery and examination of transcriptionally relevant cis-regulator and trans-regulatory elements that dictate SMG cell fate and function.

Materials and Methods

For details on materials and methods, see Appendix.

Results

Global Histone Marks in the Adult Mouse Submandibular Salivary Glands

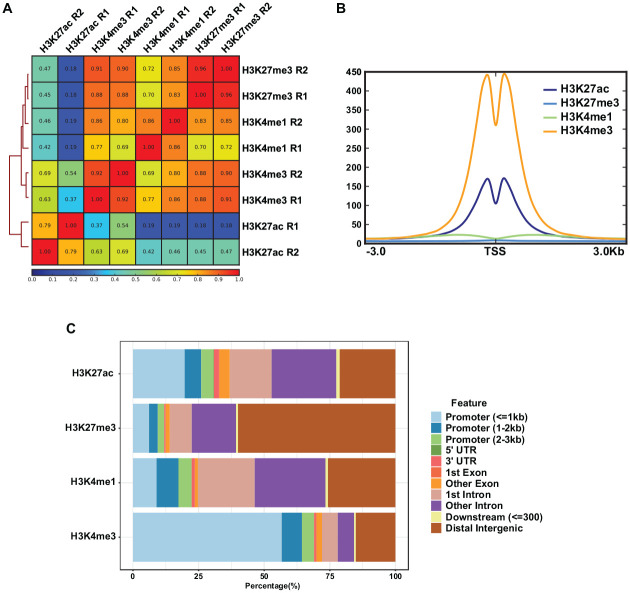

In order to establish the global epigenomic state, we generated ChIP-seq data for 4 crucial histone markers using chromatin isolated from purified salivary epithelial cells of 12-wk adult male mouse SMGs. To broadly capture the diverse nature of regulatory regions, we chose to focus on H3K27ac and H3K4me1, marks that are found on nucleosomes flanking enhancers; H3K4me3, which is primarily associated with the promoter regions; and H3K27me3, a repressive histone modification thought to be important for long-term transcriptional repression (Ernst et al. 2011). Importantly, the histone ChIP-seq experiments were performed in replicates to ensure better coverage and account for batch effects and biological variability. Pairwise Pearson correlation analysis of the 4 histone modification data sets showed good concordance between replicates, as evident by the correlation coefficients indicated in each square (Fig. 1A). As expected, the distribution of the H3K4me3 and H3K27ac marks showed robust enrichment at the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of genes (Fig. 1B), unlike H3K4me1 and H3K27me3, which are known to mark distal enhancers and repressed genomic segments, respectively. Examination of the global occupancy of the histone marks across the genomic landmarks confirmed that H3K27ac and H3K4me1 peaks were mainly located at the introns, intragenic regions, and distal intergenic regions. This was distinct from the H3K4me3 pattern showing the highest enrichment at promoters (~70%) and promoter-proximal regions (Fig. 1C). An interesting finding was the relatively high percentage of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 peaks embedded in the first intron of genes, regions that have been demonstrated to harbor a higher density of regulatory elements or functional motifs (Jo and Choi 2019).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the epigenomic marks in the submandibular gland. (A) Clustered heatmap of Pearson correlation for the H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27me3 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–seq data based on the normalized read coverages across the genome-wide regions. (B) Metaplots of average ChIP-seq density of 4 histone marks at the transcription start sites (TSSs) of genes. (C) Barplots showing the percentage distribution patterns and locations of peaks of H3K27ac, H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27me3 relative to genes.

Diverse Enhancer Landscape of Mouse Submandibular Salivary Glands

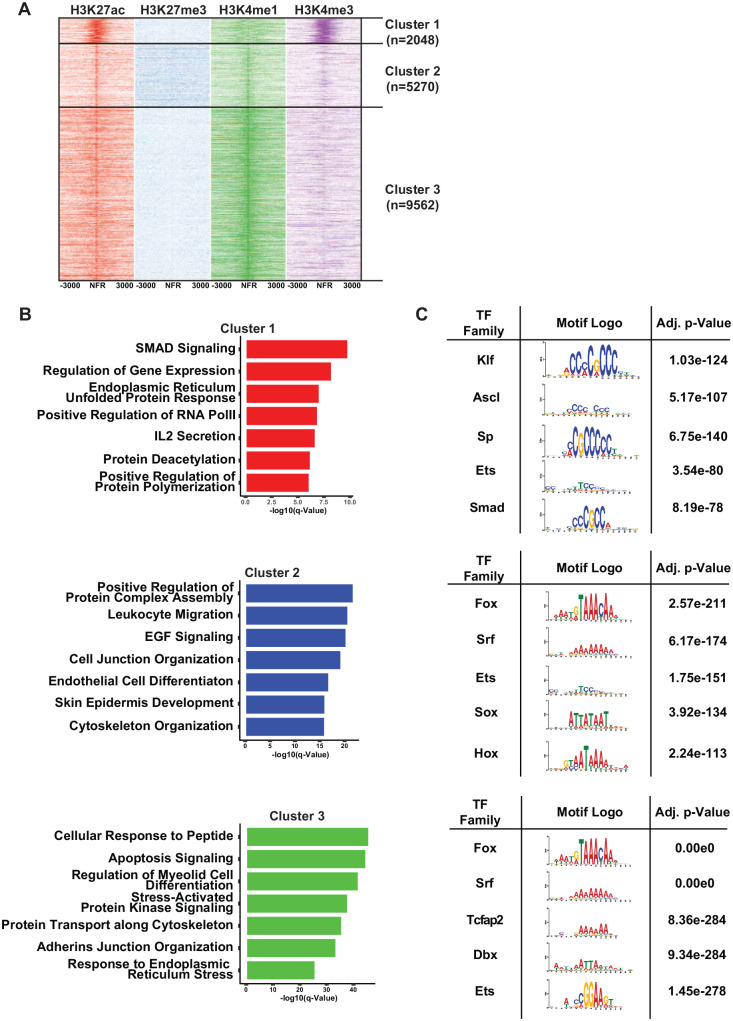

To better understand the genome-wide distribution of regulatory regions, we first focused on H3K27ac binding profiles that have been previously used to assemble a compendium of enhancers (Heinz et al. 2015). Toward this end, we identified 16,880 peaks corresponding to putative regulatory elements marked by H3K27ac enriched chromatin in the SMG. We next analyzed the chromatin state maps by examining the specific enrichment status of other histone marks centered on each of those H3K27ac peaks. Such analyses can be used to distinguish subtypes of gene regulatory states such as active regions marked by H3K27acHigh from inactive/poised genomic segments that are associated with H3K27acLow marks (Creyghton et al. 2010). This K-means clustering-driven approach led to the identification of 3 distinct clusters: cluster 1 (n = 2,048) marked by H3K4me3HighH3K27acHigh, cluster 2 (n = 5,270) marked by H3K4me1HighH3K27me3HighH3K27acLow, and cluster 3 (n = 9,562) marked by H3K4me1HighH3K27acHigh H3K27me3Low H3K4me3Low (Fig. 2A). Notably, these 3 clusters were associated with distinct subsets of potential target genes representing enrichment of different biological processes (Fig. 2B). For instance, the top enriched pathways for genes represented in cluster 1 (promoter enriched) included SMAD signaling, whereas genes associated with cluster 2 (inactive/poised states) were associated with housekeeping functions such as transcriptional initiation as well as epidermal growth factor signaling (Fig. 2B). In contrast, genes associated with cluster 3, typifying putative enhancer regions, represented myriad cellular responses and signaling pathways, including apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as well as protein transport and cell adhesion (Fig. 2B). As expected, examination of these defined cluster-specific regulatory regions by analysis of motif enrichment (AME) and central motif enrichment analysis (CentriMo) identified DNA binding motifs for specific TFs. Of note, the highly enriched motifs, many of which showed significant overlap between the AME and CentriMo analyses, belonged to members of the Forkhead-box (Fox) and E26 transformation-specific (Ets) families of TFs, among others (Fig. 2C and Appendix Fig. 1). In addition, enriched TF motifs varied between each cluster, suggesting that the distal regulatory elements and the basal promoter machinery may use distinct and unique sets of TFs to regulate gene expression in the SGs.

Figure 2.

The diverse nature of cis-regulatory elements in the submandibular salivary gland (SMG) and their potential transcriptional mediators. (A) Heatmap displaying 3 clusters of regulatory elements as defined by disparate combinatorial nature of the histone modification marks. (B) Bar plots displaying select top enriched GO Biological Processes associated with genes identified in each regulatory element cluster shown in panel A above. Genes were defined using GREAT (standard parameters) and subsequently used to find enriched gene sets using mSIGDB and marked for significance using the hypergeometric test and controlled for multiple hypothesis testing using false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05. (C) The top de novo motifs, derived from each regulatory element cluster shown in panel A above, as generated by MEME. Enriched motifs were determined by analysis of motif enrichment (AME) and using the Mouse UniProbe database.

Fox Family of Transcription Factors in the SMG

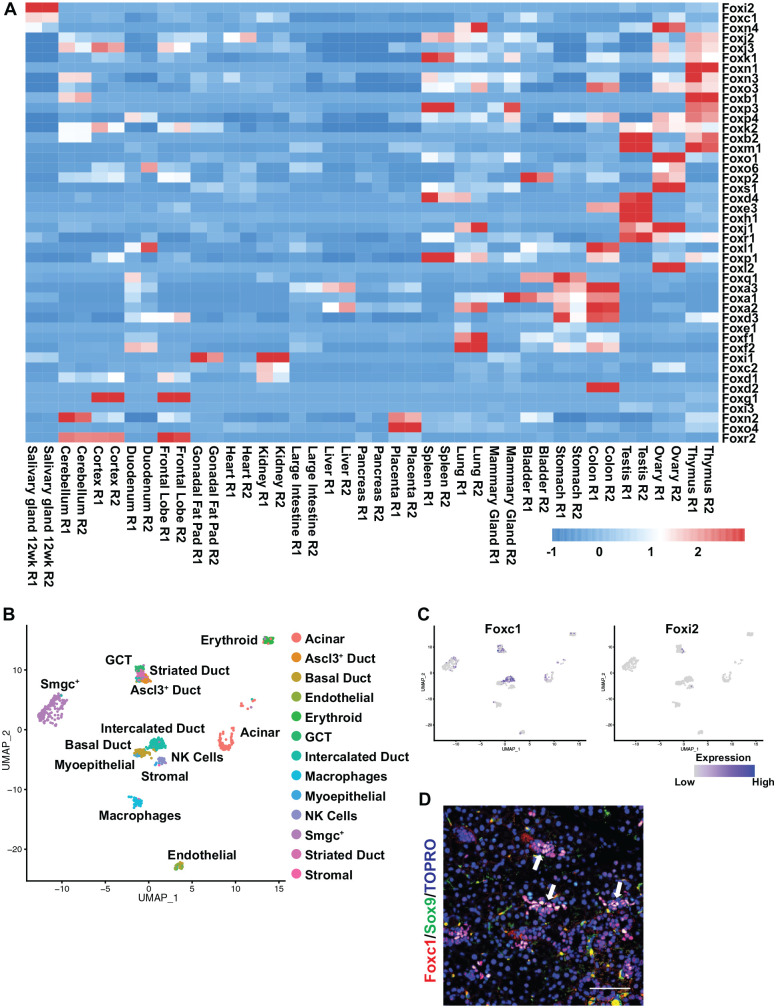

While the enrichment of DNA-binding motifs in regulatory regions is clearly suggestive, it does not a priori identify the specific TF likely to bind to these genomic regions. This is particularly true when the DNA-binding motif is shared among a large number of TFs belonging to the same family (Sandelin and Wasserman 2004). To address this question and to identify TFs likely to be relevant and functionally interacting with enhancers across the genome, we chose to focus on the Fox family due to its enriched motif in SMG enhancers (Fig. 2C). We first examined the expression levels of 44 forkhead (fkh) genes across 21 adult mouse tissues and organs, including the SG, by leveraging published RNA-seq data (Gluck et al. 2016). Hierarchical cluster analysis revealed not only the dynamic expression of various Fox family members across different organs but importantly also identified 2 members: Foxc1 and Foxi2 as selectively and most prominently expressed in the SMG compared to most tissues (Fig. 3A). To examine the cell-type specific expression pattern of these 2 TFs, we next probed the scRNA-seq data set from the wild-type 12-wk female adult mouse SMG that was recently reported by our group (Min et al. 2020). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of the data set revealed Foxc1 expression to be widespread among the various cellular populations, specifically of the ductal cells (Fig. 3B, C). Interestingly, based on feature plot analysis, we observed enriched expression of Foxc1 in the intercalated ductal cell clusters with modest expression in other ductal cell populations, including the striated, Ascl3+, Smgc+, and basal ductal cells (Fig. 3C, left panel). In contrast, Foxi2 expression was sporadic in nature and primarily restricted to the Ascl3+ ductal cell populations (Fig. 3C, right panel). To confirm these results, we next examined independent scRNA-seq data sets that were recently reported in the mouse SMG (Hauser et al. 2020). As expected, we observed distinctive profiles for both Foxc1 and Foxi2 in the SMG of various adult stages of development, including postnatal (P) day P1, P30, and adult using assigned cell cluster annotations to those previously described (Appendix Fig. 2) (Hauser et al. 2020). To confirm these findings, we performed immunofluorescence staining of adult female mouse SMG using anti-Foxc1 antibodies. We found that in agreement with scRNA-seq data, Foxc1 expression was predominantly localized to the intercalated ductal cells, as evident by costaining with the intercalated ductal cell marker Sox9 (Chatzeli et al. 2017) (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Foxc1 and Foxi2, members of the Fox family of transcriptions factors, are highly enriched in the submandibular salivary gland (SMG). (A) Heatmap showing the expression of Fox family members in mouse SMG and across a panel of mouse tissues and organs. Foxc1 and Foxi2 are selectively enriched in the salivary glands compared to other tissues. The samples were clustered by hierarchical clustering using Euclidean method as the distance measure with complete linkage. (B) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of the different cell populations in the 12-wk female adult mouse SMG based on single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis (Min et al. 2020). (C) Cell clusters were interrogated for the expression of Foxc1 and Foxi2. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of female adult mouse SMG. Foxc1 is predominantly expressed in the intercalated ductal cells as demonstrated by costaining with Sox9. Arrows highlight double positive cells. Scale bar: 37 µm.

Comparative Analysis of H3K27ac-Marked SMG Enhancers with Other Mouse Tissues and Organs

Our SG ChIP-seq data sets offered a wealth of in-depth information regarding the gene regulatory repertoire of this organ. We rationalized that although it is likely that many of these regulatory elements are present in SMG as well as numerous other tissues and organs, there may exist some genomic segments that are enriched for specific histone marks selectively in the SMG. To identify such tissue-restricted elements, we examined publicly available H3K27ac ChIP-seq data sets from the Mouse ENCODE Consortium for the 7 mouse adult organs and tissues and compared them with those from the adult SMG described in this study. For this purpose, a consensus enhancer regulatory element map (n = 31,036) was calculated using DiffBind and the top 1,500 regulatory elements were selected for use in the hierarchical reorganization of samples within the cross-correlation matrix. Our analysis revealed a clear separation of organs (Appendix Fig. 3). This same pattern was further evident when the H3K27ac signal was examined at the top 100 tissue-specific enhancers as determined by DiffBind analysis and demonstrated by the heatmap visualization in Appendix Figure 4. Collectively, these findings reaffirm the notion that the sprawling epigenomic landscape of each tissue and organ is distinct as would be predicted from the dynamic transcriptome that defines them.

Super-Enhancers of the SMG

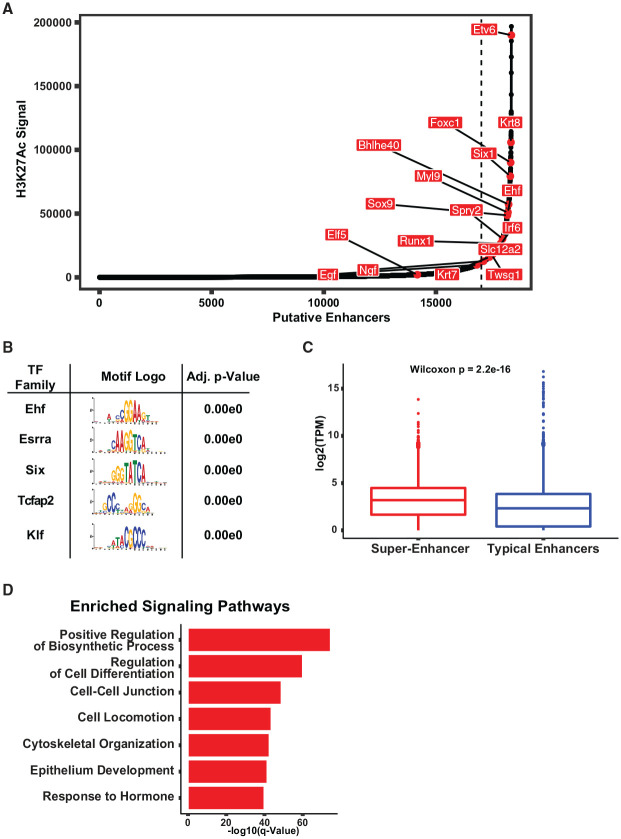

We next focused on a subset of enhancers that were subtyped as super-enhancers based on their higher levels of H3K27ac and larger genomic window as ascertained by the ranking order of super-enhancers (ROSE) algorithm (Whyte et al. 2013). As expected, several super-enhancers were associated with key regulators and critical components of SG development and differentiation, such as Six1, Twsg1, Runx1, and Slc12a2 (Nkcc1) (Fig. 4A and Appendix Table 1) (Evans et al. 2000; Melnick et al. 2006; McCoy et al. 2009; Ono Minagi et al. 2017). Additional super-enhancer marked genes included those related to stem cell biology such as Sox9; intermediate filament proteins Krt7 and Krt8; TFs such as Tfcp2l1, Bhlhe40, and Irf6; and 3 notable members of the Ets family, Etv6, Ehf, and Elf5 (Fig. 4A and Appendix Fig. 5) (Hollenhorst et al. 2011; Aure et al. 2015; Boecker et al. 2015; Chatzeli et al. 2017; Metwalli et al. 2018; Aure et al. 2019).

Figure 4.

Super-enhancer landscape of the submandibular salivary gland (SMG). (A) Hockey stick plot displaying the ranked order of typical enhancers and super-enhancers as determined by the ranking order of super-enhancers (ROSE) algorithm. Names of selected genes are shown. (B) Table displaying the top enriched transcription factor (TF) motifs found within NFRs located in SMG super-enhancers. The analysis of motif enrichment (AME) program was used to perform the enrichment analysis of the Uniprobe motif database. (C) Boxplot displaying the distribution of expression of genes marked by either a super-enhancer or a typical enhancer. GREAT analysis was used to perform gene annotation of the 2 classes of regulatory elements. Trancscipts per million values, based on our previous RNA-sequencing studies performed in the SMG, were used to determine gene expression levels (Gluck et al. 2016). (D) Bar plots displaying selected top enriched pathways and biological processes from genes annotated to the SMG super-enhancers. The mSIGDB was used to examine gene set enrichment using the hypergeometric test, with a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of <0.05.

To identify potential TFs that might preferentially bind to these super-enhancers, we next performed motif enrichment analysis of nucleosome free regions (NFRs) within these chosen genomic segments. By using the AME tool and querying the JASPAR motif database, we found that the Ehf motif was one of the most-enriched motifs based on multiple hypothesis testing, followed by the Esrra, Six, Tcfap2, and Klf families of TFs (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, in keeping with the functional importance of super-enhancers, genes that were in the vicinity of super-enhancers exhibited higher median expression levels compared to those associated with typical enhancers (Fig. 4C). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that super-enhancer associated transcripts were preferentially enriched for biological processes that involved regulation of cell differentiation, cell–cell junction, cell locomotion, and cytoskeletal organization (Fig. 4D). Surprisingly, a subset of super-enhancer associated genes was also involved in response to hormone signaling—this coupled with the observed enrichment of the DNA-binding motif of the estrogen-related receptor alpha (Esrra), a nuclear receptor known to act as a key regulator of hormones involved in metabolism and differentiation, is suggestive of a possible transcriptional link between SMG gene expression and hormonal effects (Tripathi et al. 2020).

Enhancer Regulatory Network for SMG-Specific Gene Expression

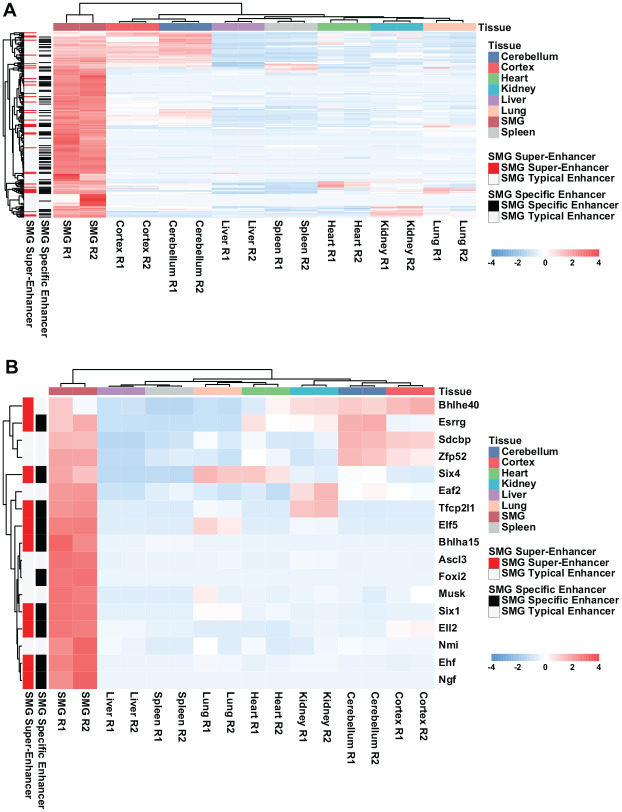

We have previously compared gene expression levels across several adult mouse organs and tissues and identified 174 genes that were specifically enriched in the SG and thus represented a potential SMG gene signature (Gluck et al. 2016). We next examined the presence of H3K27ac marked enhancer and super-enhancer regulatory regions for these SMG signature genes across a subset of tissues and organs. This analysis revealed that many of the SMG signature genes were robustly marked by enhancers and super-enhancers that were only present in the SMG and not in the 7 other tissues and organs (Fig. 5A). More specifically, genomic regions in and around 2 TF genes, Pax9 and Foxc1, clearly showed H3K27ac enrichment exclusively in the SMG and not in any other organs (Appendix Fig. 6). This finding suggests that the tissue-specific/enriched expression of TFs in the SG is governed by an array of enhancers, some of which are exclusively located and active, in this specific organ. This notion is further strengthened upon examination of the enhancer and super-enhancer landscape of the 15 TFs that we had previously identified as part of the SMG-enriched gene signature (Gluck et al. 2016). These SMG-enriched TFs were clearly marked by a combination of super-enhancer and typical enhancers (Fig. 5B). More important, several of these cis-regulatory regions were exclusive to the SMG and not marked in lung, spleen, cortex, cerebellum, kidney, heart, or liver (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these studies reveal a complex network of transcriptional regulatory elements that act in concert to achieve the distinctive gene expression patterns of the SMG.

Figure 5.

Component signature genes of the submandibular salivary gland (SMG) are enriched for tissue-specific enhancers and super-enhancers. (A) Heatmap displaying the expression levels of all the genes that comprise the adult salivary gland gene signature across the select tissues used for epigenetic analysis and comparison. Far-left panel highlights genes that are associated by a SMG super-enhancer (red), typical enhancer (white), or a SMG-specific enhancer (black). (B) Heatmap showing the expression of transcription factors (TFs) that make up the SMG gene signature using the same analysis as described in panel A.

Discussion

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to obtain whole-genome maps of active enhancers across many tissues and organs. These studies, often performed under the auspices of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium, have underscored the importance of focusing on noncoding regions of the genome to better understand the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation and tissue-specific gene expression patterns (Bernstein et al. 2010; Heinz et al. 2015). With that goal in mind, here we have focused our studies on the genome-wide identification and characterization of functional active enhancers of the murine SMG, a key organ for which such data sets are currently lacking. The epigenomic data reported here complement the vast catalog of genetic, molecular, and more recent, genomic studies that have been instrumental in offering molecular clues into the anatomical states and physiological functions of the SG (Gluck et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2018; Song et al. 2018; Mukaibo et al. 2019; Oyelakin et al. 2019; Hauser et al. 2020; Min et al. 2020; Sekiguchi et al. 2020).

We show that, as expected, the SMG has an extensive array of typical enhancers and super-enhancers, a subset of which are highly restricted to the SMG as compared to other mouse organs and tissues. We also found that many such enhancers were correlated with expression of adjacent target genes—a finding that was epitomized by the higher gene expression levels of super-enhancer marked genes. In addition to defining the broader enhancer landscape, we were also able to leverage our prior RNA-seq–based SMG-enriched gene signature to examine how these enhancers and super-enhancers were likely to act in concerted and tissue-specific fashions. Our analysis revealed that TFs such as Bhlhe40 and Tfcp2l1, both of which are part of the SMG-enriched gene signature, were found to be associated with tissue-specific regulatory modules that were absent from other tissues and organs. It is worth stressing that H3K4me1/3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3 marks do not represent the full repertoire of histone modifications that define regulatory regions—hence, studies with additional enhancer marks are likely to offer more insights. Another limitation of our studies is the heterogeneous nature of the SMG cell population that was surveyed by histone ChIP-seq. This shortcoming could be overcome by single-cell epigenomics analysis, which is becoming feasible due to rapid technical innovations.

One interesting revelation of our bioinformatics-driven approach was the identification of DNA-binding TFs that are likely to be relevant trans factors in controlling gene expression programs in the SMG. Although we found enrichment of several known binding motifs in the regulatory regions, the presence of the Fox motif in the active enhancers was particularly revelatory. The Fox gene family encodes TFs that play pleiotropic roles in developmental and adult biological/cellular processes, such as cell cycle control, proliferation and differentiation, and tissue homeostasis (Hannenhalli and Kaestner 2009). Our analysis revealed that of the 44 mouse Fox factors, Foxc1 and Foxi2 are specifically and highly enriched in the SMG. The functional importance of Foxc1 and Foxi2 in SMG biology is supported by the fact that these 2 genes are marked by SMG-specific enhancers and show a dynamic expression pattern in distinct cell populations. Recent studies showing that Foxc1, in concert with Sox9, can induce the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cell–derived oral ectoderm into a SG rudiment in an organoid culture system attests to the lineage-driving capacity of Foxc1 and a possible role as a pioneer TF that promotes chromatin accessibility (Mayran and Drouin 2018; Tanaka et al. 2018). It is also worth noting that Foxc1 is highly expressed in the human SGs based on RNA-seq studies and thus might have an evolutionarily conserved role as suggested from computational modeling of cis-regulatory networks of the SG (Michael et al. 2019; Saitou et al. 2020).

The availability of the global enhancer and regulatory map of the murine adult SMG offers a valuable resource for both hypothesis testing and generation. For example, it will be interesting to examine the acquisition and evolutionary nature of the gene regulatory cis-elements in the SMG and the possible role of retrotransposons in this process as recently described for mammary glands (Nishihara 2019). We also posit that the available knowledge of these regulatory networks has major consequences not only for normal SMG development and differentiation but also for a better understanding of the various diseases that affect this organ. A case in point is a recent study demonstrating how enhancer hijacking activates the oncogenic TF nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 3 (Nr4a3) in acini cell carcinomas of the SG (Haller et al. 2019). Similarly, it is becoming clear that mutations that fall within noncoding regions contribute immensely to the pathogenesis of complex diseases (Albert and Kruglyak 2015; van Arensbergen et al. 2019). Indeed, most SNPs disrupt gene regulation rather than alter the protein-coding sequence or protein structure—therefore, identifying regulatory regions is critical to gaining insights into underlying biological mechanisms of diseases. Finally, the enhancer map of the SMG offers an epigenomic blueprint that can be intelligently mined for better design and generation of transgenic mouse models to direct tissue-specific gene expression to the SMG.

Author Contributions

C. Gluck, contributed to data analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; S. Min, A. Oyelakin, M. Che, E. Horeth, E.A.C. Song, J. Bard, N. Lamb, contributed to data analysis, critically revised the manuscript; S. Sinha, R.A. Romano, contributed to conception, design, and data analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jdr-10.1177_00220345211012000 for A Global Vista of the Epigenomic State of the Mouse Submandibular Gland by C. Gluck, S. Min, A. Oyelakin, M. Che, E. Horeth, E.A.C. Song, J. Bard, N. Lamb, S. Sinha and R.A. Romano in Journal of Dental Research

Footnotes

A supplemental appendix to this article is available online.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIH/NIDCR) grant DE027660 to R.A. Romano. S. Min, A. Oyelakin, E. Horeth, and E.A.C. Song were supported by the State University of New York at Buffalo, School of Dental Medicine, Department of Oral Biology training grant (NIH/NIDCR) DE023526.

ORCID iDs: A. Oyelakin  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0607-6631

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0607-6631

N. Lamb  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2774-9586

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2774-9586

R.A. Romano  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9652-9555

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9652-9555

References

- Albert FW, Kruglyak L. 2015. The role of regulatory variation in complex traits and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 16(4):197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aure MH, Konieczny SF, Ovitt CE. 2015. Salivary gland homeostasis is maintained through acinar cell self-duplication. Dev Cell. 33(2):231–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aure MH, Symonds JM, Mays JW, Hoffman MP. 2019. Epithelial cell lineage and signaling in murine salivary glands. J Dent Res. 98(11):1186–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Costello JF, Ren B, Milosavljevic A, Meissner A, Kellis M, Marra MA, Beaudet AL, Ecker JR, et al. 2010. The NIH roadmap epigenomics mapping consortium. Nat Biotechnol. 28(10):1045–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boecker W, Stenman G, Loening T, Andersson MK, Berg T, Lange A, Bankfalvi A, Samoilova V, Tiemann K, Buchwalow I. 2015. Squamous/epidermoid differentiation in normal breast and salivary gland tissues and their corresponding tumors originate from p63/K5/14-positive progenitor cells. Virchows Arch. 466(1):21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzeli L, Gaete M, Tucker AS. 2017. Fgf10 and sox9 are essential for the establishment of distal progenitor cells during mouse salivary gland development. Development. 144(12):2294–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, et al. 2010. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107(50):21931–21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, et al. 2011. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 473(7345):43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RL, Park K, Turner RJ, Watson GE, Nguyen HV, Dennett MR, Hand AR, Flagella M, Shull GE, Melvin JE. 2000. Severe impairment of salivation in Na+/K+/2Cl- cotransporter (NKCC1)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 275(35):26720–26726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Oei MS, Ovitt CE, Sincan M, Melvin JE. 2018. Transcriptional profiling reveals gland-specific differential expression in the three major salivary glands of the adult mouse. Physiol Genomics. 50(4):263–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluck C, Min S, Oyelakin A, Smalley K, Sinha S, Romano RA. 2016. RNA-seq based transcriptomic map reveals new insights into mouse salivary gland development and maturation. BMC Genomics. 17(1):923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller F, Skalova A, Ihrler S, Markl B, Bieg M, Moskalev EA, Erber R, Blank S, Winkelmann C, Hebele S, et al. 2019. Nuclear NR4A3 immunostaining is a specific and sensitive novel marker for acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary glands. Am J Surg Pathol. 43(9):1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannenhalli S, Kaestner KH. 2009. The evolution of fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 10(4):233–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser BR, Aure MH, Kelly MC, Genomics and Computational Biology Core, Hoffman MP, Chibly AM. 2020. Generation of a single-cell RNAseq atlas of murine salivary gland development. iScience. 23(12):101838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Romanoski CE, Benner C, Glass CK. 2015. The selection and function of cell type-specific enhancers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 16(3):144–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Lau A, Saint-Andre V, Sigova AA, Hoke HA, Young RA. 2013. Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell. 155(4):934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenhorst PC, McIntosh LP, Graves BJ. 2011. Genomic and biochemical insights into the specificity of ETS transcription factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 80:437–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo SS, Choi SS. 2019. Analysis of the functional relevance of epigenetic chromatin marks in the first intron associated with specific gene expression patterns. Genome Biol Evol. 11(3):786–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama CL, Monroe MM, Hunt JP, Buchmann L, Baker OJ. 2019. Comparing human and mouse salivary glands: a practice guide for salivary researchers. Oral Dis. 25(2):403–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayran A, Drouin J. 2018. Pioneer transcription factors shape the epigenetic landscape. J Biol Chem. 293(36):13795–13804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy EL, Kawakami K, Ford HL, Coletta RD. 2009. Expression of six1 homeobox gene during development of the mouse submandibular salivary gland. Oral Dis. 15(6):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick M, Petryk A, Abichaker G, Witcher D, Person AD, Jaskoll T. 2006. Embryonic salivary gland dysmorphogenesis in twisted gastrulation deficient mice. Arch Oral Biol. 51(5):433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metwalli KA, Do MA, Nguyen K, Mallick S, Kin K, Farokhnia N, Jun G, Fakhouri WD. 2018. Interferon regulatory factor 6 is necessary for salivary glands and pancreas development. J Dent Res. 97(2):226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael DG, Pranzatelli TJF, Warner BM, Yin H, Chiorini JA. 2019. Integrated epigenetic mapping of human and mouse salivary gene regulation. J Dent Res. 98(2):209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min S, Oyelakin A, Gluck C, Bard JE, Song EC, Smalley K, Che M, Flores E, Sinha S, Romano RA. 2020. P63 and its target follistatin maintain salivary gland stem/progenitor cell function through TGF-β/activin signaling. iScience. 23(9):101524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukaibo T, Gao X, Yang NY, Oei MS, Nakamoto T, Melvin JE. 2019. Sexual dimorphisms in the transcriptomes of murine salivary glands. FEBS Open Bio. 9(5):947–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara H. 2019. Retrotransposons spread potential cis-regulatory elements during mammary gland evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(22):11551–11562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Minagi H, Sarper SE, Kurosaka H, Kuremoto KI, Taniuchi I, Sakai T, Yamashiro T. 2017. Runx1 mediates the development of the granular convoluted tubules in the submandibular glands. PLoS One. 12(9):e0184395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyelakin A, Song EAC, Min S, Bard JE, Kann JV, Horeth E, Smalley K, Kramer JM, Sinha S, Romano RA. 2019. Transcriptomic and single-cell analysis of the murine parotid gland. J Dent Res. 98(13):1539–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. 2019. Physiology, pathology and regeneration of salivary glands. Cells. 8(9):976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M, Gaylord EA, Xu E, May AJ, Neznanova L, Nathan S, Grawe A, Chang J, Ryan W, Ruhl S, et al. 2020. Functional specialization of human salivary glands and origins of proteins intrinsic to human saliva. Cell Rep. 33(7):108402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Wasserman WW. 2004. Constrained binding site diversity within families of transcription factors enhances pattern discovery bioinformatics. J Mol Biol. 338(2):207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi R, Martin D, Genomics and Computational Biology Core, Yamada KM. 2020. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies cell diversity in embryonic salivary glands. J Dent Res. 99(1):69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song EC, Min S, Oyelakin A, Smalley K, Bard JE, Liao L, Xu J, Romano RA. 2018. Genetic and scRNA-seq analysis reveals distinct cell populations that contribute to salivary gland development and maintenance. Sci Rep. 8(1):14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Ogawa M, Hojo H, Kawashima Y, Mabuchi Y, Hata K, Nakamura S, Yasuhara R, Takamatsu K, Irie T, et al. 2018. Generation of orthotopically functional salivary gland from embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun. 9(1):4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi M, Yen PM, Singh BK. 2020. Estrogen-related receptor alpha: an under-appreciated potential target for the treatment of metabolic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 21(5):1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Arensbergen J, Pagie L, FitzPatrick VD, de Haas M, Baltissen MP, Comoglio F, van der Weide RH, Teunissen H, Vosa U, Franke L, et al. 2019. High-throughput identification of human SNPs affecting regulatory element activity. Nat Genet. 51(7):1160–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, Young RA. 2013. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell. 153(2):307–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Adli M, Zou JY, Verstappen G, Coyne M, Zhang X, Durham T, Miri M, Deshpande V, De Jager PL, et al. 2013. Genome-wide chromatin state transitions associated with developmental and environmental cues. Cell. 152(3):642–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jdr-10.1177_00220345211012000 for A Global Vista of the Epigenomic State of the Mouse Submandibular Gland by C. Gluck, S. Min, A. Oyelakin, M. Che, E. Horeth, E.A.C. Song, J. Bard, N. Lamb, S. Sinha and R.A. Romano in Journal of Dental Research