Abstract

Background

The Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) ‘Improving Safety and Reducing Error in Endoscopy’ (ISREE) strategy was developed in 2018. In line with the strategy, a survey was conducted within the JAG census in 2019 to gain further insights and understanding of key safety-related areas within UK endoscopy.

Methods

Questions were developed using the ISREE strategy as a guide and adapted by key JAG stakeholders. They were incorporated into the 2019 JAG census of UK endoscopy services. Quantitative and qualitative statistical methods were employed to analyse the results.

Results

There was a 68% response rate. There was regional variability in the provision of out-of-hours GIB services (p<0.001). Across 1 month, 1535 incidents were reported across all services. There was a significantly higher proportion of reported incidents in acute services compared with others (p<0.001). Technical and training incidents were likely to be reported significantly differently to all other incident types. 74% of services have an endoscopy-specific sedation policy and 42% have a named sedation or anaesthetic lead for endoscopy. Services highlighted a desire for more anaesthetic-supported lists. Only 66% of services stated they have an effective strategy for supporting upskilling of endoscopists. Across acute services, 56% have access to human factors and endoscopic non-technical skills (ENTS) training. Patient feedback is used in several ways to improve services, develop training and promote shared learning among endoscopy users.

Conclusions

The census provides a benchmark for key safety-related characteristics of endoscopy services. These results have highlighted key areas to develop, guided by the ISREE strategy.

Keywords: endoscopy

Summary box.

What is already known on this topic

Safety is a key domain within the quality standards for endoscopy services. Demand is increasing and there is greater procedural complexity which may impact on the safety of endoscopy.

What this study adds

The national census identified a variety of factors related to safety across UK endoscopy services. There is regional variability of provision of services including gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, preassessment and sedation policies. There is variability between services in incident reporting behaviours, with training and technical incidents less likely to be reported. Services stated a desire to have more anaesthetic-supported lists. Training in human factors is available to just over half of services and two thirds have strategies to support underperformance.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Understanding safety and current practices helps to identify areas for improvement. Future work should focus on improving access to out of hours GI bleeding, anaesthetic-supported lists, human factors training and awareness of incident reporting.

Background

Safety in endoscopy is a core aspect of the Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) quality standards. Safety-related standards reflect adverse event (AE) monitoring, mortality and readmission reviews, meeting national gastrointestinal bleeding standards and implementation of local safety protocols. These are defined within the Global Rating Scale,1 a quality improvement tool for services and the accreditation standards.2 Accreditation is awarded to those services that meet specific criteria across all standards, following an assessment by JAG.

While the standards provide an insight into the safety practices of services, it was recognised that more could be done to understand and improve safety within UK endoscopy, particularly in the era of increasing procedural demand and complexity.3 Acknowledging this, JAG developed the ‘Improving Safety and Reducing Error in Endoscopy’ (ISREE) strategy in 2018.4 The core domains of the strategy are:

Preventing patient safety incidents (PSIs).

Promoting incident reporting.

Promoting learning from incident.

Improving training in ENTS.

Supporting underperforming endoscopists and services.

The ISREE strategy has direct relevance to endoscopy at a level that national standards may not necessarily be able to reach, complementing the recently published National Health Service (NHS) patient safety strategy.5 This articles describes the 2019 JAG safety census. The purpose was to better understand a variety of aspects of safety in endoscopy that had not been investigated before, highlighting good practice and identifying areas for improvement.

Methods

Study design

The safety section of the 2017 census was expanded and questions aligned to the ISREE strategy.4 Questions were developed by the primary investigating team (SR, ST-G) and then underwent multiple iterations of review and adaptation by key JAG stakeholders (TS, MD, RB, HG, DK, EW and JG) under the remit of the JAG Endoscopy Services Quality Assurance Group. A final version of the survey was agreed between members before wider dissemination (see online supplementary file). The updated content included questions related to the following areas of interest:

flgastro-2020-101561supp001.pdf (155KB, pdf)

PSI reporting behaviours.

Promoting learning from incidents.

GI bleed (GIB).

Anaesthetic support.

Pre-assessment and sedation.

Supporting underperforming endoscopists and/or services.

Simulation and ENTS training.

Utilising patient feedback.

Data collection

Safety questions were sent as part of the biennial census to all UK JAG-registered services in April 2019. The main census results have been described separately.6 A lead respondent from each service was asked to complete and return questions within 4 weeks. Response rates were reinforced by weekly reminder emails. Responses were collated for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as frequencies of categorical data and mean, SD, median and IQR of numerical data, depending on normality (assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk method). Outcome measures were identified for each subsection of the survey and analysed in turn (dependent variables), looking for associations with core demographic data (independent variables). Associations between categorical variables were analysed using the X2 or Fisher’s exact test (where appropriate). The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to measure differences between services when dependent variables were either continuous or ordinal in nature. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to assess differences in continuous variables across individual services. Statistical significance is indicated by p<0.05 unless otherwise stated.

Free-text responses were collated and analysed by a combination of thematic and content analysis. All statistical calculations were performed using IBM SPSS V.25. Qualitative analysis was performed using QSR International NVivo V.12 (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia).

Results

The response rate was 68.4% (322/471). Out of the services that replied, 52.5% of services were acute (NHS services with emergency care), 40.4% independent (independent or private sector services) and 7.1% non-acute (NHS services without emergency care).

PSI reporting

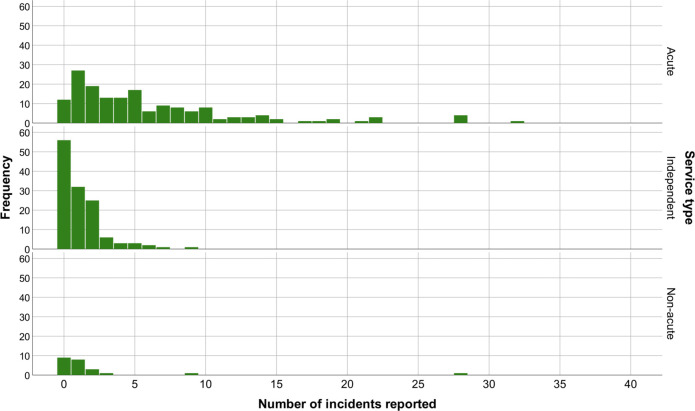

In March 2019, there were a total of 1535 reported incidents (median 2 per service, IQR 1–5). The number of reported incidents appear to be related to service type (p<0.001) with significant differences observed between acute and independent (p<0.001) and acute and non-acute services (p<0.001; see figure 1). Region (p=0.10) and accreditation status (p=0.29) had no association with the number of incidents.

Figure 1.

Histogram of incidents reported by endoscopy service type in 1 month (March 2019).

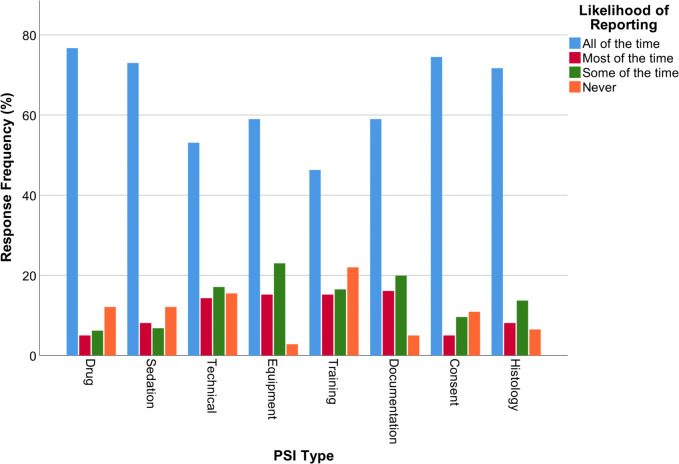

In order to understand reporting behaviours further, services were asked how likely they would be to report specific PSI types (a full summary of PSI categories can be found in online supplementary file). Overall, services reported training-related safety incidents the least (22% never reported), and drug-related incidents the most (87.9% reported; see figure 2).

Figure 2.

The likelihood of incident reporting by PSI type. Frequency of reporting is provided as a percentage of responses per category. PSI, patient safety incident.

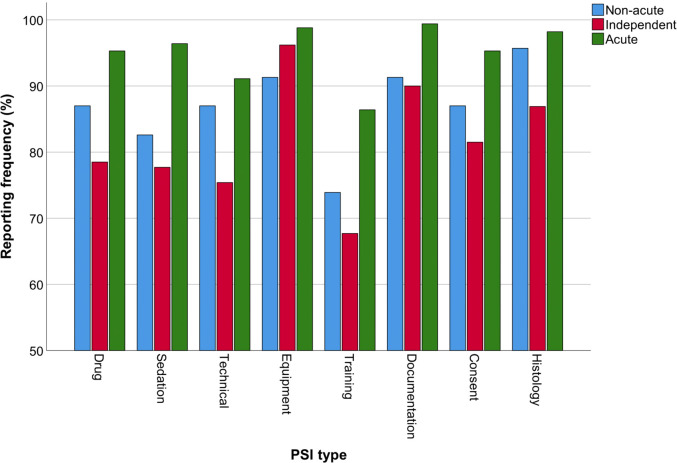

There was a significant difference in the reporting likelihood between PSI types (χ2 (7)=308.1, p<0.001). Reported incident types were classified into those that were likely to be ‘reported’ or ‘never reported’ and associations with region, service type and accreditation status were analysed. Accredited services were more likely to report drug, sedation, technical and consent incidents than unaccredited services (p<0.001). There was a significant difference in reporting of PSI types between service types (p≤0.003) except for ‘equipment incidents’ (p=0.057, see figure 3). Differences were largely due to independent services who were least likely to report these incidents compared with acute or non-acute services. There was no association between region and reporting of incident types.

Figure 3.

Reporting behaviours by service type. Percentage represents where services would report each incident (all, most or some of the time). PSI, patient safety incident.

Nearly three-quarters (74.8%) of services use the DATIX system to report incidents. Of the remaining services, reporting systems used are RiskMan (66.0%), Ulysses (11.3%), Sentinel (9.4%) and bespoke systems (13.2%). 97.2% of services were confident that their reporting system was a robust method to report incidents in their departments. Additionally, 92.2% (297/322) services were confident that their reporting system was a robust method to learn from incidents in their departments. Meetings are often used to discuss and learn from incidents and 94.1% (303/322) of services reported having a meeting where all AEs are discussed and learning shared.

Gi bleeding

Across acute services, 82.2% (139/169) have access to a 24/7 GIB service. There is a statistically significant association between region and GIB provision (Fisher’s exact test, p<0.001). Accreditation status was significantly associated with GIB provision (χ2(1)=12.04, p<0.001). The majority of out-of-hours GIB service is delivered in theatre (57.6%) and staffed by consultants only (81.3%). Endoscopy nurses staff GIB rotas in 66.9% of services.

Anaesthetic support

Out of surveyed services, 73.0% (235/322) had access to anaesthetic-supported lists—44.4% (143/322) had access to adhoc lists only and 28.6% (92/322) had access to regular lists. There was a statistically significant association between access to anaesthetic lists and service type (χ2(4)=67.86, p<0.001) with non-acute services lacking provision. There was no association with region (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.13).

Where regular anaesthetic-supported lists were run, 50.5% of services run 1–3 lists per month, 30.8% run 4–10 lists and 18.7% run more than 10 per month. There was a significant difference between the current and desired number of anaesthetic lists for services who run regular (p=0.007) and adhoc lists (p<0.001) with a shift towards a desire for more anaesthetic-supported lists.

Preassessment and sedation

Overall, 76.1% of services (245/322) have some form of preassessment service, 73.6% (237/322) have an endoscopy-specific sedation policy and 42.2% (136/322) have a named sedation or anaesthetic lead for endoscopy. Likelihood of reporting sedation-related incidents was associated with presence of a sedation lead (p=0.03) but not with a sedation policy (p=0.87). There was no significant association between service type or accreditation status with presence of preassessment service, sedation policy or sedation lead.

Supporting underperformance

Overall, 66.1% (213/322) of services stated they have an effective strategy for supporting underperformance and upskilling of endoscopists. There appears to be regional variation in the provision for such a strategy (χ2(9)=23.70, p=0.005). London and the Midlands had the highest relative provision for such strategies. Services were asked how many independent, non-trainee endoscopists have needed support for improvement in the preceding 12 months (see table 1). A significantly higher number of endoscopists require support for technical skills compared with non-technical skills or combination of both (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Summary of endoscopists requiring support for technical and non-technical skills in the preceding 12 months

| Skill type | No of endoscopists requiring support | |

| Mean±SD | Range | |

| Technical | 0.48±1.09 | 0–8 |

| Non-technical | 0.21±0.81 | 0–11 |

| Combination (technical and non-technical) | 0.13±0.47 | 0–4 |

Simulation and ENTS training

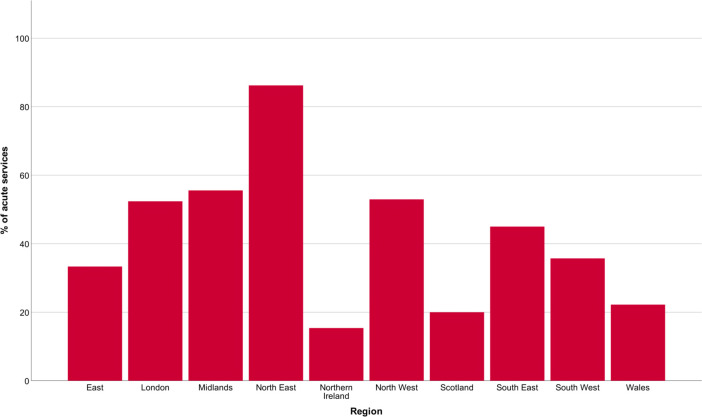

Across acute services, 49.1% (83/169) had provision for endoscopy simulation in their departments. There was a statistically significant difference in provision between regions (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.001; see figure 4). Out-of-acute services, 55.6% (94/169) have access to human factors training (including ENTS training). 63.9% of services that have simulation provision also have access to human factors training.

Figure 4.

Provision of simulation across acute services by region.

Using patient feedback

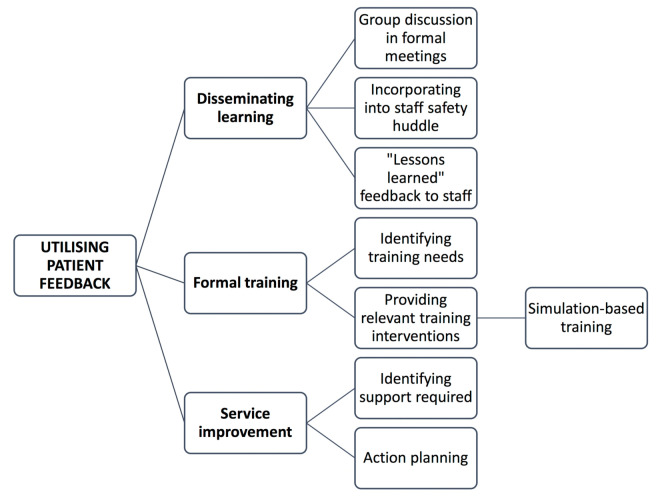

Overall, 50.9% (164/322) of services reported use of a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) tool. Further analysis revealed the only explicitly specified PROM tool was the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Satisfaction Questionnaire, used in 18% of services. 46.3% (149/322) of services use patient feedback, mortality or readmission data to develop endoscopy training initiatives. Services were asked to describe how they utilised patient feedback specifically for learning. Three major themes emerged: disseminating learning, developing formal training and service improvement (see figure 5).

Figure 5.

Thematic map of methods used by services to develop learning from patient feedback.

Discussion

This was the first survey of safety-related practice across national endoscopy services, exploring areas beyond the current JAG standards, in the pre-COVID-19 era.

There appears to be regional variability in the provision out-of-hours access to GIB services. The previous British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and NHS national survey of acute upper GIB (2014–15) identified 80% of English trusts (n=142) had provision for 24/7 GIB services.7 In this census, this had increased to 92.7% of English services (127/137). However, there are ongoing challenges to developing sustainable GIB services across regions with poor access. It is important to understand the challenges these services face, which may relate to service pressure, workforce and conflicting clinical commitments.7 Our results demonstrate a significantly higher proportion of services with GIB provision had been JAG accredited, perhaps highlighting the impact of accreditation in improving quality.

Just under three-quarters of services have an endoscopy-specific sedation policy and less than a half have a named sedation or anaesthetic lead for endoscopy. Guidance from the Royal College of Anaesthetists and Academy of Medical Royal Colleges highlights the need to have policies and protocols for delivering safe sedation in procedures outside of the theatre environment.8 9 These appear to be mirrored in American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy sedation guidelines.10 Additionally, the presence of nominated sedation or anaesthetic lead may improve the quality and safety of sedation practice in non-theatre areas.8 With the increasing complexity and comorbidity of patients undergoing endoscopy, it is unsurprising that our results suggest there is an aspiration for more anaesthetic-supported lists. This is an area of focus where additional leadership and support from a nominated anaesthetic lead may help, as defined within the ISREE strategy.

There appears to be a wide variability in the number and type of PSIs reported across endoscopy services. Acute services tend to report more incidents per month than others. This could simply be related to a higher volume of patients undergoing more complex and therapeutic procedures than in other sectors. With that said, greater reporting does not necessarily equate to greater numbers of incidents. Reporting behaviours may play a part in this. Classically, lack of engagement in incident reporting results from staff disengagement due to lack of feedback following incidents.11 12 In contrast, targeted patient safety education has been associated with an increase in reporting likelihood.13 Both these factors may explain differences in reporting behaviours across service types, however, there may be a lack of consistency in reporting too. The PSI categories chosen to be explored in the census were extracted from an observational study of incidents in endoscopy.14 While some PSIs may be clearly ‘reportable’, for example, a drug error, some may not necessarily be reported at all, for example, a training error such as unsafe supervision. The culture of reporting and knowledge of what a safety incident constitutes are two key factors in reporting behaviour. Education around patient safety and incident recognition is important in improving our detection of PSIs.13 In the coming years, incident reporting will become more transparent and accessible, including patient interfaces to maximise the breadth of incidents captured.15

A half of services used a dedicated PROM tool to collect patient-related data following endoscopy. PROM tools are important in measuring clinical quality and safety from the patient perspective.16 There is now a greater drive to measure the experiences of patients rather than just satisfaction, reflected in the recent BSG position statement on patient experience.17 Novel ‘Patient-Reported Experience Measures’ tools are in development, which may provide another metric of quality and safety in endoscopy.18 Patient-reported information is classically underutilised in driving change within healthcare.19 Our results provide an overview of how services are proactively using current feedback mechanisms to develop dedicated training interventions, group learning and service improvement work.

Just over a quarter of services do not have an effective strategy to manage underperformance. Identifying and managing underperformance is crucial to maintaining quality and safety. JAG has recently published guidance towards supporting services in managing underperformance,20 supported by wider-reaching multinational guidance.21 There appear to be a higher proportion of endoscopists requiring support for technical skills compared with non-technical skills. This may reflect the relative ease and transparency in detecting technical underperformance through measuring key performance indicators. However, detecting and supporting deficiencies in non-technical skills may be challenging and may require other forms of appraisal and assessment. The multiassistant rating scale for ENTS may be one measure that could be incorporated into rolling appraisals of independent endoscopists.22

A key arm of the ISREE strategy is the development and expansion of human factors and ENTS training. NTS has been inherently linked to team functioning and can be a factor contributing to PSIs.14 Human factors training is largely delivered through simulation.23 Across the acute endoscopy services surveyed, there is a distinct regional variation in simulation provision, with approximately a half of services having access. Work is underway to develop programmes that enable delivery of simulation-based training to the workforce.23 The aim is to develop accessibility to training, particularly where local facilities may be lacking. It is likely that as JAG updates training pathways, a greater emphasis is placed on human factors and ENTS training.

Limitations

This census had a lower response rate than the previous census, which may affect generalisability of results. Additionally, regional comparative results are based on proportionate data and therefore may be affected by a lower response across regions. Due to the self-reported nature of surveys, data may be prone to recall bias and have not been validated against other information sources. The data described should be interpreted as an exploration and description of the current status quo.

Conclusions

The census provides a benchmark for key safety-related characteristics of endoscopy services. Areas to develop and explore include safety incident reporting, utilisation of patient feedback, supporting underperformance and ENTS training. The ISREE strategy provides a framework to develop these areas further, which may inform future standards and have a direct impact on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the JAG office team for their administrative support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Doc_Wot, @SiwanTG

Contributors: SR conducted statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript with editorial oversight from ST-G, CJH and JG. PB verified statistical analyses. All authors contributed to question design for the census. All authors reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SR, CJH, JG, MC and ST-G hold or have held clinical positions at the Joint Advisory Group on GI endoscopy.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information. All relevant data have been included within the article.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Formal ethics approval for this study was not required.

References

- 1. Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy . GRS standards - acute services, 2016. Available: https://www.thejag.org.uk/Downloads/JAG/Accreditation-GlobalRatingScale(GRS)/Guidance-acuteGRSstandardsUK.pdf

- 2. Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy . Joint Advisory group on gastrointestinal endoscopy (JAG) accreditation standards for endoscopy services, 2018. Available: https://www.thejag.org.uk/downloads/Accreditation/JAGaccreditationstandardsforendoscopyservices.pdf

- 3. Matharoo M, Thomas-Gibson S. Safe endoscopy. Frontline Gastroenterol 2017;8:86–9. 10.1136/flgastro-2016-100766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy . Improving safety and reducing error in endoscopy (ISREE) implementation strategy, 2018. Available: https://www.thejag.org.uk/Downloads/General/180801-ImprovingSafetyandReducingErrorinEndoscopy(ISREE)Implementationstrategyv1.0.pdf

- 5. NHS Improvement . The NHS patient safety strategy, 2019. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/patient-safety-strategy/

- 6. Ravindran S, Bassett P, Shaw T, et al. National census of UK endoscopy services in 2019. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;44:flgastro-2020-101538. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nedjat-Shokouhi B, Glynn M, Denton ERE, et al. Provision of out-of-hours services for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in England: results of the 2014-2015 BSG/NHS England national survey. Frontline Gastroenterol 2017;8:8–12. 10.1136/flgastro-2016-100706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges . Safe sedation practice for healthcare procedures: standards and guidance, 2013. Available: https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Safe_Sedation_Practice_1213.pdf

- 9. Royal College of Anaesthetists . Chapter 7: guidelines for the provision of anaesthesia services in the Non-theatre environment 2020, 2020. Available: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/gpas/chapter-7-section-3.10

- 10. Early DS, Lightdale JR, ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, et al. Guidelines for sedation and anesthesia in Gi endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:327–37. 10.1016/j.gie.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kingston MJ, Evans SM, Smith BJ, et al. Attitudes of doctors and nurses towards incident reporting: a qualitative analysis. Med J Aust 2004;181:36–9. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Archer G, Colhoun A. Incident reporting behaviours following the Francis report: a cross-sectional survey. J Eval Clin Pract 2018;24:362–8. 10.1111/jep.12849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jansma JD, Wagner C, ten Kate RW, et al. Effects on incident reporting after educating residents in patient safety: a controlled study. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:335. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matharoo M, Haycock A, Sevdalis N, et al. A prospective study of patient safety incidents in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endosc Int Open 2017;5:E83–9. 10.1055/s-0042-117219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NHS Improvement . The future of the patient safety incident reporting: upgrading the NRLS, 2017. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/news-alerts/development-patient-safety-incident-management-system-dpsims/

- 16. Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient-Reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ 2017;17:137–44. 10.1093/bjaed/mkw060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rees CJ, Trebble TM, Von Wagner C, et al. British Society of gastroenterology position statement on patient experience of Gi endoscopy. Gut 2019:gutjnl-2019-319207. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neilson LJ, Patterson J, von Wagner C, et al. Patient experience of gastrointestinal endoscopy: Informing the development of the Newcastle ENDOPREM™. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;11:209–17. 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flott KM, Graham C, Darzi A, et al. Can we use patient-reported feedback to drive change? the challenges of using patient-reported feedback and how they might be addressed. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:502–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy . A framework for managing underperformance and supporting endoscopists – a JAG perspective, 2019. Available: https://www.thejag.org.uk/CMS/UploadedDocuments/Scheme/Scheme1/STG190917-guidance-UKunderperformanceforJAGv2.0.pdf

- 21. Rees CJ, Thomas-Gibson S, Bourke MJ, et al. Managing underperformance in endoscopy: a pragmatic approach. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88:737–44. 10.1016/j.gie.2018.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kokwara F. PTU-014 development of the multi-assistant rating scale (MARs) for endoscopic non-technical skills performance in independently practising endoscopists. Gut 2017;66:A57. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ravindran S, Thomas-Gibson S, Murray S, et al. Improving safety and reducing error in endoscopy: simulation training in human factors. Frontline Gastroenterol 2019;10:160–6. 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2020-101561supp001.pdf (155KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information. All relevant data have been included within the article.