Abstract

Fungi have great prospects for synthesis, applications and developing new products in nanotechnology. In recent times, fungi use in nanotechnology is gaining more attention because of the ecological friendly state of their metabolite-mediated nanoparticles, their safety, amenability and applications in diverse fields. The diversity of the metabolites such as enzymes, polysaccharide, polypeptide, protein and other macro-molecules has made fungi a veritable tool for nanoparticles synthesis. Mechanism of fungal nano-biosynthesis from the molecular perspective has been extensively studied through various investigations on its green synthesized metal nanoparticles. Fungal nanobiotechnology has been applied in agricultural, medical and industrial sectors for goods and services improvement and delivery to mankind. Agriculturally, it has found applications in plant disease management and production of environmentally friendly, non-toxic insecticides, fungicides to enhance agricultural production in general. Medically, diagnosis and treatment of diseases, especially of microbial origin have been improved with fungal nanoparticles through more efficient drug delivery systems with great benefits to pharmaceutical industries. This review therefore explored fungal nanobiotechnology; mechanism of synthesis, characterization and potential applications in various fields of human endeavours for goods and services delivery.

Keywords: Fungi, Nanobiotechnology, Medicinal, Agricultural, Industrial

Fungi; Nanobiotechnology; Medicinal; Agricultural; Industrial.

1. Introduction

Generally, fungi are eukaryotic organisms which are predominately decomposers. Today, over 1.5 million species of fungi are believed to thrive and survive in various habitats on Earth; however, only 70,000 species have been well taxonomically identified. In addition, approximately 5.1 million fungal species were found when high-through put sequencing method was carried out. Regardless of the differences in the fungal population in the world as reported by different studies, it is worth stating that fungi are actually ubiquitous and in fact, their population might actually be more than ever reported in any study. The major cosmopolitan characteristics of the fungal kingdom reside in extracellular breakdown of substrate, secretion of important enzymes to breakdown compounds of great complexity into simpler forms and use of diverse energy sources (Blackwell, 2011). Thus, the exploration of fungi, its implication and potential in nanobiotechnology is important.

Myconanotechnology, as it is commonly called, is thus defined as the interface between nanotechnology and mycology (Hanafy, 2018; Sousa et al., 2020). The field of myconanotechnology is of great potentials, partly due to the wide range and diversity of fungi (Khande and Shahi, 2018). Mycology is the study of fungi while nanotechnology is the study involving the design, synthesis and application of technologically important particles of nano size (Sousa et al., 2020). In this light, the design and synthesis of metal nanoparticles using fungi is termed mycofabrication. In recent times, the fungal system has emerged as important bionanofactory for the synthesis of nanoparticles of gold, silver, CdS, platinum etc. Fungal bionanofactories has produced important nanoparticles of good dimensions and monodispersity (Guilger-Casagrande and Lima, 2019).

Furthermore, fungi are reported to produce proteins in large quantities, they are important in the significant large-scale production of nanoparticles. Most fungal proteins are known for hydrolyzing metal ions. More so, fungi are easily isolated and cultured. More so, fungal nanoparticles of enzymes, polysaccharides, protein and other macromolecules are diverse in size and mostly secreted extracellularly. Therefore, fungal enzymes’ extraction and purification is less complicated than synthetic processes as fungi play a critical role in preventing environmental pollution. The use of microorganisms in the synthesis of nanoparticles is an appealing green nanotechnology choice and the use of biological systems, like fungi, has recently emerged as a novel approach for nanoparticle synthesis (Castro et al., 2014; Dorcheh and Vahabi, 2016; Elegbede and Lateef, 2018; Elegbede et al., 2019). This review however discusses the various principles in vogue for fungal nanoparticles production and applications in different fields of human endeavours.

1.1. Outstanding properties of fungi in nanobiotechnology

It is believed that, any microorganism that would be considered for nanobiotechnological purposes must be of generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status in all fronts without any sort of controversy. Similarly, the main property of fungi in nanobiotechnology is the GRAS status and regardless of the enzyme, habitat and biology of the fungi, they must be generally safe. Interestingly, fungi producing important nanoparticles are of GRAS status. In addition, because of their tolerance and metal biological accumulation potential, fungi are of great interest in the biological development of metallic nanoparticles (Sastry et al., 2003). Metal ions can be accumulated by fungi through physical, chemical and biological mechanisms such as extracellular binding of polymers and metabolites, binding to particular polypeptides, and metabolism-dependent accumulation.

Furthermore, fungi can easily be scaled up even in thin solid substrate fermentation technique and this is an important attribute of using them in nanoparticle synthesis. Also, fungi are excellent secretors of extracellular enzymes, so large-scale processing of enzymes is possible (Castro-Longoria et al., 2012). Another benefit of using a green approach mediated by fungi to synthesize metallic nanoparticles is the ease with which biomass can be used. Since a variety of fungal species grow rapidly, culturing and maintaining them in the laboratory is very easy (Castro-Longoria et al., 2011). Since fungi are culturable in large amounts, their potential use has gotten a lot of attention. Furthermore, extracellular secretion of enzymes has a benefit in downstream biomass processing and handling. Another property of fungi that made it favoured for nanobiotechnological functions is the high wall-binding and intracellular metal uptake (Bourzama et al., 2021). Fungi can generate metal nanoparticles/meso and nanostructures by using a reducing enzyme, either intracellular or extracellular, and a biomimetic mineralization technique (Mughal et al., 2021; Siddiqi and Husen, 2016; Duran et al., 2005). In comparison to bacteria and other microorganisms, fungi are excellent protein secretors, resulting in a higher yield of nanoparticles (Mughal et al., 2021; Guilger-Casagrande and Lima, 2019). As a result of fungi's dissimilatory properties, fast and environmentally friendly solutions are possible.

1.2. Common fungi in nanobiotechnology

In the world today, fungi are the prime organism in secreting nanoparticles in a far less environmentally damaging way. Fungi diversity have been reported as valuable biological substance for the synthesis of nanoparticles. Penicillium aurantiogriseum, Penicillium citrinum and Penicillium waksmanii mediated synthesis of copper nanoparticles were reported by Honary et al. (2012). The synthesized nanoparticles displayed a fairly uniform with spherical shape. Proteins produced from fungi culture are capable of hydrolyzing metal precursors to form metal oxides extracellularly were supported by UV-vis and fluorescence Spectrum. In vitro approach for gold nanoparticles biosynthesis from the fungus Penicillium aurantiogriseum, Penicillium citrinum and Penicillium waksmanii have also been established. The synthesized gold nanoparticles formed showed a fairly uniform with spherical shape with the Z-average diameter of 153.3 nm, 172 nm and 160.1 nm for Penicillium aurantiogriseum, Penicillium citrinum, and Penicillium waksmanii, respectively.

The synthesized nanoparticles formed showed a fairly well-defined dimension and good monodispersity. The nanoparticles formed were relatively uniform with spherical shape and superiorly monodispersed with the average diameter of 60 nm. The result showed the scolicidal effects of the synthesized nanoparticles extremely significant for all the four concentrations evaluated and at various exposure times in comparison to the control group (P < 0.0001).

This development is a great news as nanobiotechnology is already proving to be of great use in diverse fields especially in medical field where high level of purity is required of any compound (Khan et al., 2019). Fungi are now important medically in disease diagnosis and treatment; most importantly allowing for efficient drug delivery in places that have always been difficult to reach. In addition, gold nanoparticle production has been reported in Aspergillus, Neurospora, Fusarium, Pleurotus and Verticillium species (Wang et al., 2021; Rai et al., 2021; Kitching et al., 2015; Priyadarshini et al., 2014). At room temperature, 5–40 nmpolydispersed silver nanoparticles are produced by Trichoderma viride. Fungi in general have secreted diverse nanoparticle sizes.

In addition to fungi mediated nanoparticles from the normal environment, important nanoparticles have been reported from extreme environments. As reported by Tiquia-Arashiro (2014), the classification of extremophiles and their ecology is the first step in creating processes and goods that will benefit mankind as extremophiles are biotechnologically interesting because they generate extremozymes, which are enzymes that work in extreme environments. Extremozymes are important in industrial manufacturing processes with great applications in research as they possess the capability to stay active in adverse conditions such as high temperature, pH, and pressure. Identifying extremophiles from natural environments has just touched the surface of research with just around 1% of the species have been described, and far fewer have had their beneficial properties sequenced. However, as many researchers have pointed out, the detection of extremophiles has opened up possibilities for commercial, biotechnological, and medical applications (Gabani and Singh, 2013; Pomaranski and Tiquia-Arashiro, 2016).

Extremozymes have a lot of potential in industrial biotechnology because they can be utilized in unusually extreme environments, which can lead to substrate transitions that aren't possible with regular enzymes. Enzyme-mediated reactions permit for more complex chemo-, regio-, and stereo-selectivity in organic synthesis than chemical catalysis (Koeller and Wong, 2001). However, enzymes' long-term viability and reusability have been cited as significant obstacles to their widespread use by Schmid et al. (2011). Diverse nanoparticles have recently been used to boost conventional enzyme immobilization methods in industrial biotechnology to improve enzyme loading, function, and stability while lowering biocatalyst costs.

2. Current advances in the principles of synthesizing fungal mediated nanoparticles

The synthesis of fungi mediated nanoparticles offers great advantages compares to other microorganisms like bacteria and actinomycetes. Some of these great advantages offer by fungi includes their easy to handle and downstream the process, economically feasible and ecologically friendly to cover a large surface (Syed and Ahmad, 2012). Enzymes in the cytoplasm and cell wall of fungi transform metal ions into nanoparticles (Chatterjee et al., 2020). In term of nanoparticles production, fungi have higher productivity and higher tolerances to metals especially in context of high cell wall binding capacity of metal ions with biomass (Singh et al., 2016). Fungi is attracted by the positive charge possessed by the metal ions and this triggers the biosynthesis. However, specific proteins are also induced by metal ions, and these hydrolyze the ions. Some of the recent studies conducted on nanoparticles synthesis using fungi are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of recent studies on nanoparticle synthesis using fungi.

| Nanoparticle | Fungus | Application | Intra/Extra | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum | Fusarium oxysporum | Nano medicine | Extra | (Chatterjee et al., 2020) |

| Iron oxide | Aspergillus niger BSC-1 | Wastewater treatment | Extra | (Mohmed et al., 2017) |

| Silver | Aspergillus terreus | Antibacterial, anticancer | Extra | (Hulikere and Joshi, 2019) |

| Silver Silver |

Cladosporium cladosporioides Ganoderma lucidium G. applanatum |

Antioxidant, antimicrobial Antimicrobial |

Extra Both |

(Zhang et al., 2019) (Aygün et al., 2020) |

| Copper | Aspergillus niger | Antidiabetic and Antibacterial | Extra | (Zhang et al., 2019) |

| Gold | Cladosporium oxysporum | Catalysis | Extra | (Srivastava et al., 2019) |

| Selenium | Mariannaea sp. HJ | Medicinal and electronics | Both | (Vijayanandan, and Balakrishnan, 2018) |

| Cobalt oxide | Aspergillus nidulans | Energy storage | Extra | (Joshi et al., 2017) |

| Gold Silver, Gold, Selenium |

Cladosporium cladosporioides Mushrooms |

Antioxidant, antimicrobial Biomedicals |

Extra Both |

(Bhargava et al., 2016) (Adebayo et al., 2021) |

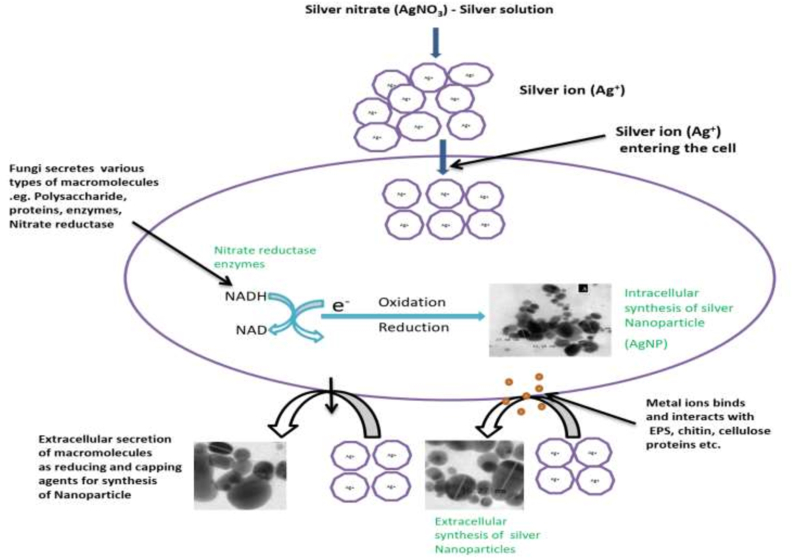

As stated above, the presence of proteins on fungal cell surfaces, fungi are suitable for the synthesis of nanoparticles as opposed to other species of microorganisms. The synthesis of metal nanoparticles via the reduction of reductase enzymes present in the cell wall of fungal cells is the most common process of intracellular biological synthesis. As a cellular protective process against the chemical toxins present in their environments, fungi develop nanoparticles and various chemical reactions reduce toxic ions to their metal nanoparticles, with some of these reactions including complexation, immobilisation, precipitation and co-precipitation, biosorption, ion-form alteration and bio-coupling (Dorcheh and Vahabi, 2016). At the reductive state, fungi use their cellular enzymes, proteinaceous molecules, or cell membrane-bound molecules like electron donors, and the poisonous ions are quickly precipitated as metal nanoparticles, either intracellularly or extracellularly, depending on the biological synthesis process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mechanism of Fungi mediated silver nanoparticles (AgNPs).

The formation of structures atom by atom, molecule by molecule, or by self-organization is a type of bottom-up technique in which the main reaction is dependent on reduction or oxidation of the substrate, resulting in a rise in colloidal structures and it has been established that fungal enzymes or metabolites are often responsible for a decrease in metallic composition of nanoparticles. The bottom-up approach is demonstrated by the way myco-reduced metal atoms transfer nucleation with subsequent development, resulting in the forming of nanostructures and the benefit of a bottom-up approach is the greater likelihood of creating nanostructures without significant defects, as reported in nanorods or nanosheets, with the secretion of more homogeneous chemical compositions. Furthermore, owing to the reduction of Gibb's free energy, which this technique is driven by, the bottom-up strategy means a better chance of receiving less faulty nanoparticles and a much more homogeneous chemical composition.

2.1. Extracellular fungal biosynthesis of nanoparticles

The extracellular biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles relies heavily on fungal cell membranes as they contain a significant number of differently bound compounds, such as peptides, proteins, polysaccharides, oxidoreductases, and quinones, which are involved in the reduction and precipitation of metal ions (Keat et al., 2015; Moghaddam et al., 2015). Extracellular reductase is the enzyme in control of metal nanoparticle biological synthesis and development (Vahabi and Dorcheh, 2014) with Fusarium oxysporum been shown to manufacture NADPH-dependent nitrate and sulfite reductases, which are used in the biological synthesis of Ag- and Au-nanoparticles, respectively.

Additionally, hydrogenases, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent glutathione reductase, and nitrate reductases have also been discovered to play a role in the biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles through fungi; however, studies have indicated that metal reduction involves an electron shuttle in the reductase enzyme system. Quinones (anthraquinones and naphthopquinones), as well as their quinine counterparts, have been discovered to aid in the reduction process and furthermore, when fungal cells were exposed to heavy metal ion exposure, metalloproteins such as phytochelatin and metallothionein were found to be overexpressed, and these metalloproteins assisted in the reduction process by complexing the metal ions via their binding and reductive abilities (Park et al., 2016).

Protein molecules found in mycelial membranes can be used to facilitate extracellular fungal nanoparticle biological synthesis and it has been suggested that surface-bound proteins in R. oryzae and Coriolus versicolor mycelia associate with gold and silver ions, resulting in the reduction and stabilization of Au-nanoparticles and Ag-nanoparticles respectively (Das et al., 2012). The electrostatic reactions between protein-free amine or cysteine residues and enzyme carboxylate groups in fungal cells are believed to be responsible for the formation of protein-metal bonds and as a result, a redox state is formed, allowing metal nanoparticles to precipitate and form (Park et al., 2016).

A number of extracellular fungal products have been discovered to contribute to the biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles, under which these nanoparticles were synthesized to mitigate the toxic actions of metal ions, which were then precipitated as nanoparticles and in response to the toxicity of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II), Curvularia lunata was found to contain extracellular mucilage materials. Furthermore, toxicity of Ni(II) and Cd(II) were reported to allow Aureobasidium pullulans to develop pullulans, and glomalin glycoprotein was found to sequester Cu(II) in Glomus cultures (Cornejo et al., 2008).

2.2. Intracellular fungal biosynthesis of nanoparticles

Metal nanoparticle intracellular biological synthesis in fungal cells is primarily due to cellular ATPases and hydrogenases while Fusarium oxysporum was discovered to generate Au-nanoparticles intracellularly in cytoplasmic vacuoles, with plasma membrane-ATPase, 3-glucan binding enzyme, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase playing a vital role in the reaction (Vahabi and Dorcheh, 2014). Hydrogenases generate cytoplasmic hydrogen, which is needed for metal nanoparticle precipitation (Riddin et al., 2009) and in detoxification, yeast cells utilize intracellular glutathione as well as two metal-binding proteins (phytochelatin and metallothionein). This was due to the fact that these compounds have significant redox and nucleophilic properties, allowing them to participate in metal ion biological reduction and furthermore, it has been documented that fungal cell use their antioxidative systems to detoxify metal ions in order to shield themselves from the oxidative power of these metal ions (Jha and Prasad, 2016).

As cells are exposed to heavy metals, oxygen is depleted intracellularly, resulting in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide, which can then generate highly active and harmful free hydrogen radicals; however, to avoid these reactions, the fungal cellular machinery employs a variety of enzymatic systems, including antioxidative systems (Morano et al., 2012). Catalases and superoxide dismutase, methionine sulfoxide reductase, thioredoxins, peroxiredoxins, glutathione and glutathione peroxidases and transferases are all antioxidative systems contained in fungi and to transport required substrates (C- and N-sources), micronutrients, and ions inside fungal cells, different membrane channels and transporter proteins are employed (Ujam et al., 2021; Ibrahim et al., 2021; Vitale et al., 2020). Toxic metals, on the other hand, may use these channel structures to access the cytoplasmic space and to prevent poisonous metal ions from entering the cytoplasm, cells may obstruct or even remove certain transport systems. However, this has the potential to disrupt cellular machinery, and certain metal ions can reach cells through several routes while cellular enzymes can react with metal ions and precipitate nanomaterials in such situations (Gahlawat and Choudhury, 2019).

The same enzymes and proteins that are involved in the extracellular biosynthesis of nanoparticles are often involved in the intracellular biological synthesis of metal nanoparticles as growth conditions change. As Trichothecium sp. cells grow in static cultures, extracellular nanoparticles were synthesized while biological synthesis was transferred to intracellular pathways during development in submerged culture and different intracellular pathways were used to biosynthesize metal nanoparticles to accomplish this turn. This shift in biological synthesis was due to the observation that static cultures enable fungal cells to excrete their enzymes and proteins extracellularly, while in a submerged culture environment, these enzymes were not released.

2.3. Synthesis of some fungal mediated nanoparticles of different sizes

One of the well-established researches on the biological synthesis of metal nanoparticle via fungi is the production of silver nanoparticles extracellularly by the filamentous fungal cells of Verticillium sp. documented by Mukherjee et al. (2001a, b). In the biosynthesis of nanoparticles, the filamentous cells of Fusarium oxysporum has also been extensively used among the thousands of fungi documented for this purpose. Mostly, the production of extracellular nanoparticles is reported in exposing biomass to metallic ion solutions in a study by Ahmad et al. (2002). Many fungi are reported to secrete CdS, MoS2, ZnS and PbS nanoparticles with a feasible sulfate diminishing enzyme-based process for nanoparticles production linked to the presence of proteins in the aqueous solution and by using fungi; leading to separate and easy recovery of silver nanoparticles. Fungal nanoparticles produced have diverse morphologies with sizes ranging from 5 to 50 nm as reported by Ahmad et al. (2003).

In a study by Duran et al. (2005), spherical silver nanoparticles have sizes ranging from 20 to 50 nm using F. oxysporum. The differences in sizes of fungal silver nanoparticles have been heavily linked to different culturing temperature (Riddin et al., 2006). The most often created nanoparticles are quasi-spherical as reported by several authors, different morphologies of nanoparticles are recovered in the metallic ion solution of fungi. With F. oxysporum, the production of nanoparticles of diverse metals has been reported (Duran et al., 2005). Technique of nanoparticle synthesis is mainly extracellularly, producing different forms and sizes of the particle. The metallic ion reduction in F. oxysporum, has been linked to a NADH-based reductases and a shuttle Quinone extracellular procedure by Mukherjee et al. (2001a, b).

Furthermore, it was documented that various concentrations of NADH had an effect on the production of Au–Ag alloy nanoparticles with a number of compounds (MubarakAli et al., 2012). Furthermore, phytochelatin and purified -NADPH-dependent nitrate reductase produced by R. stolonifer were used to successfully manufacture silver nanoparticles in the 10–25 nm size range (Binupriya et al., 2010). Govender et al. (2009) proposed a method using a purified hydrogenase enzyme from F. oxysporum to biologically reduce H2PtCl6 and PtCl2 into platinum nanoparticles while metal nanoparticles of varying shapes and sizes were synthesised using fungal biomass and/or cell-free extract (Shankar et al., 2013).

Generally, diverse fungal species can be utilized to produce diverse nanoparticles under similar experimental condition and for example, while Verticillium sp. nanoparticles had a cubo-octahedral shape with a size range of 100–400 nm magnetite, F. oxysporum nanoparticles had an irregular structure with a complete quasi-spherical morphology with a size range of 20–50 nm as reported by Bharde et al. (2006). The differences in the nanoparticles produced can be due to the condensation of biomolecules, incubation conditions, precursor etc. Also, the use of Rhizopus oryzae in synthesizing metal nanoparticles is well established for controlling the form of gold nanoparticles at room temperature by regulating growth factors like gold ion concentration, solution pH, and response time (Das et al., 2010).

3. Current advances in fungal nanobiotechnology applications

Fungal nanobiotechnology has found applications in diverse areas of human lives. Nanoparticles from fungi have been employed for several purposes; ranging from human health management, through agriculture, food production to several other industrial processes.

3.1. Medical application of fungal nanobiotechnology

In recent times, there is an increase in acceptability level of nanotechnology in biomedicine and this has triggered the huge development observed in fungal nanobiotechnology in biomedical sciences. From diagnosis to treatment and drug delivery, studies in the field of nanomedicine have progressed steadily and significantly. Fungal nanobiotechnology has found applications in biologically labeling fluorescent, gene and drug delivery factors and in biological detection of pathogens, tissue engineering, tumor demolition through heating (hyperthermia), MRI contrast enhancement, phagokinetic investigations etc (Table 2). Magnetic nanoparticles are good for targeted drug delivery and hyperthermia use with discrete nanoparticles often applied in nanobiomedicine. The availability of several journals and articles on the applications of fungal nanoparticles in biomedicine has greatly contributed to the advancement over the years.

Table 2.

Fungi and properties of fungi-mediated nanoparticles used for medical application.

| Fungus species | Nanoparticles | Localization | Size (nm) | Shape | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ZnO | Extracellular | 1.2–6.8 | Spherical and hexagonal | Bio medical | Raliya and Tarafdar (2013) |

| Aspergillus oryzae | FeCl3 | - | 10–24.6 | Spherical | Biomedical | Raliya (2013) |

| Aspergillus tubingensis | Ca3P2O8 | Extracellular | 28.2 | Spherical | Biomedical | Tarafdar et al. (2012) |

| Helminthosporum solani | Au | Extracellular | 2–70 | Polydispersed | Anti-cancer drug | Kumar et al. (2008) |

| Penicillium brevicompactum | Au | - | 10–50 | Spherical | To target cancer cells | Mishra et al. (2011) |

| Volvariella volvacea | Au | - | 20–150 | Spherical | Therapeutic | Philip (2009) |

| Candida albicans | Au | - | 20–40, 60–80 | Spherical & nonspherical | Detection of liver cancer | Chuhan et al. (2011) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Ag | Extracellular | 20–50 | Spherical | Antibacterial | Duran et al. (2005) |

| Aspergillus niger | Ag | Extracellular | 3–30 | Spherical | Antibacterial and antifungal activity | Jaidev and Narasimha (2010) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Ag | - | 15–45 | Mostly spherical | Antiviral against HIV-1 | Alani et al. (2012) |

| Pleurotus sajor caju | Ag | Extracellular | 30.5 | Spherical | Antibacterial activity | Vigneshwaran and Kathe (2007) |

| Aspergillus niger | Ag | - | 5–35 | Spherical | Antimicrobial | Kathiresan et al. (2010) |

| Volvariella volvaceae | Ag | - | 15 | Spherical | Medical applications | Thakkar et al. (2010) |

| Phoma glomerata | Ag | - | 60–80 | Spherical | Antibiotic | Birla et al. (2009) |

| Trichoderma viride | Ag | - | 5–40 | Spherical, rod-like | Antibacterial activity | Fayaz et al. (2009a) |

| Trichoderma viride | Ag | Extracellular | 5–40 | Spherical, rod-like | synergistic effect with antibiotics | Fayaz et al. (2010b) |

| Amylomyces rouxii KSU-09 | Ag | - | 5–27 | Spherical | Antimicrobial | Musarrat et al. (2010) |

| Aspergillus clavitus | Ag | Extracellular | 550–650 | - | Antimicrobial | Saravanan and Nanda (2010) |

| Aspergillus terreus CZR-1 | Ag | Extracellular | 2.5 | Spherical | Biomedical | Raliya and Tarafdar (2012) |

| Volvariella volvaceae | Au–Ag | Extracellular | 20–150 | Triangular | Medical application | Thakkar et al. (2010) |

| Aspergillus flavus | TiO2 | - | 62–74 | Spherical | Antimicrobial | Rajakumar et al. (2012) |

Due to the fact that biosynthesized nanoparticles are a relatively recent field, researchers have already begun to examine their possible applications in fields such as drug delivery, cancer therapy, gene treatment and DNA analysis, antibacterial, biological sensors, separation science, and MRI. Mishra et al. (2011) studied the biosynthesis of AuNP in the fungus Penicillium brevicompactum using the supernatant, live cell filtrate, and biomass while Jeyaraj et al. (2013) looked at the effects of Ag-NP on cancer cell lines in another study. More specifically, using the fungus Trichoderma viride, silver nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 5 to 40 nm were biologically synthesized (Fayaz et al., 2010b).

Nanoparticles have also been studied for their ability to enhance the antimicrobial activity of a number of antibiotics against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Ampicillin, kanamycin, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol's antibacterial properties were improved with Ag-NP against pathogenic species with the highest effect recorded in ampicillin in combination with the nanoparticles. This finding indicated that combining antibiotics with Ag-NP improved antimicrobial activity. Duhan et al. (2007) reported antagonistic effect of extracellularly formed silver nanoparticles of Fusarium oxysporum against Staphylococcus aureus and thus, suggested this application into textile industry in addition to the biomedical application.

Gajbhiye et al. (2009) reported the antifungal property of biosynthesized nanoparticles in combination with fluconazol (a triazole antifungal drug) against Phoma glomerata, P. herbarum, Fusarium semitectum, Trichoderma sp. and Candida albicans. Fluconazole's antifungal efficacy was improved by AgNPs generated by Alternaria alternata, against all tested strains except P. herbarum and F. semitectum. In a separate research, mycelia-free water extracts of the fungal strain Amylomyces rouxii were found to be high in AgNPs and effective against Shigella dysenteriae type I, Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter sp., E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Candida albicans and Fusarium oxysporum (Musarrat et al., 2010). Das et al. (2009) produced AuNPs on Rhizopus oryzae surface and inhibited the growth of G− and G+ bacterial species.

Trichoderma viride filtrate mediated AgNPs demonstrated significant importance in labeling and imaging with laser excitation and photoluminescence measurements emission at the range of 320–520 nm (Sarkar et al., 2010). A major problem in contemporary laser medicine has been the intensive interaction of sensitive tissues outside of the operating realm. On the contrary, this problem can be solved by locating dyes which allows the redirection of the radiation blurs to the surface of irradiated tissues in limiting optical radiation (Podgaetsky et al., 2004). In addition, there are other studies that reported the cadmium telluride quantum dots (CdTe QDs) fabrication by extracellular synthesis of nanoparticles by Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Bao et al., 2010) and Escherichia coli. The nanoparticles were of great optical features of tiny size, protein cover and great ability in water as analyzed using UV-visible spectroscopy and spectrofluorimetry with photoluminescence emission at 488–551 nm. The CdTe QDs associated with folic acid has been reported in the imaging of cancer cells, and they were shown to have biological compatibility in a cytotoxicity assay (Bao et al., 2010).

Furthermore, nanotechnology and its impact on pharmaceutical improvement alongside with metallic nanoparticles and their wide range of potentials in pharmaceutical applications such as anti-cancer, anti-parasite, bactericidal, fungicidal, etc. had been reported by several researchers. A systematically review of the efficacy of these nanoparticles (NPs) against lung cancer through in vitro models was reported by Barabadi et al. (2019). The ability of the biosynthesized nanoparticles (NPs) from Penicillium species has been considered as a potential approach for combating vectors of malaria and also as a treatment for malaria (Barabadi et al., 2019). Khatua et al. (2020), reported the fungicidal potential of emerging gold nanoparticles using Pongamia pinnata leave extract as a novel approach in nanoparticle synthesis. The results showed a strong inhibition potential against plant pathogen and can be suggested as potential antifungal agent for plant pathogens. Mushroom fruiting bodies mediated metallic nanoparticles with different biomedical applications have been reported (Adebayo et al., 2021).

3.2. Agricultural application of fungal nanobiotechnology

Fungal nanobiotechnology has greater potential application for growth of diverse agricultural sectors and allied part, which will likely produce a myriad of nanostructured materials (Goel, 2015; Rai and Ingle, 2012, Rai et al., 2015; Prasad, 2014). Diverse agricultural applications of the myconanofabrications are nanofungicides, nanopesticides, nanoinsecticides and nanofertilizers and so on in conjunction with the ability to serve as the antimicrobial agents has been reported by several authors (Prasad et al., 2014, 2017; Bhattacharyya et al., 2016). Fungal nanobiotechnology can be used for the development of nanobiosensors which is referred to as a new class of biosensors. Nanobiosensor is a means of detecting biological agents such as antibodies, nucleic acids, pathogens, and metabolites. Nanobiosensors can be successfully used for sensing a vast variety of fertilizers, herbicide, pesticide, pathogens, moisture, and soil pH (Prasad et al., 2014, 2017). These systems allow farmers to know the best time for planting and harvesting. Some of the prominent applications of fungal nanobiotechnology in several agriculture sectors are previously reported. The effect of the synthesized silver nanoparticles mediated by fungus Aspergillus versicolor against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea in strawberry plants was observed by Elgorban et al. (2016). The obtained result showed a dose dependent activity towards pest with highest observation effect against of B. cinerea. The effect of the biological synthesized nanoparticles from the fungus Epicoccum nigrum was observed against isolates of the pathogenic fungi C. albicans, Fusarium solani, Sporothrix schenckii, Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus fumigatus Qian et al. (2013). Nanoparticles synthesized form the fungus Guignardia mangiferae showed a potential ability to control the phytopathogenic fungi Colletotrichum sp., Rhizoctonia solani, and Curvularia lunata Balakumaran et al. (2015). In other work, the mycofabrication of the nanoparticles using the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium solani (isolated from wheat) have a potential for the treatment of wheat, barley, and maize seeds contaminated by different species of phytopathogenic fungi (Abd El-Aziz et al., 2015).

Many authors have documented the combination of biogenic nanoparticles and conventional biocides. The potential evaluation of the nanoparticle's synthesis mediated by the fungus Alternaria alternata, in combination with the antifungal compound fluconazole against the fungi Phoma glomerata, Phoma herbarum, Fusarium semitectum, alongside with biological control agent Trichoderma sp. and the human pathogenic fungus Candida albicans were established by Gajbhiye et al. (2009). The efficacy of the combined nanoparticles and fluconazole, with C. albicans displayed highest sensitivity after exposure, followed by Trichoderma sp. and P. glomerata. Other authors have documented the agricultural importance of the biogenic synthesis of the nanoparticles from Trichoderma harzianum with mortality when they were tested against the larvae and pupae of the dengue vector mosquito Aedes aegypti (Sundaravadivelan and Padmanabhan, 2014).

Nanobiotechnology has been applied in agricultural practices to boost production of food in terms of nutrients, security, quantity and quality. The most effective approaches to increase production of food are to apply fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and plant growth factors/regulators efficiently, via nanocarriers for regulated release. Poly (epsilon-caprolactone) nanocapsules, for example, have recently been developed as herbicide carrier for atrazine (Oliveira et al., 2015). When mustard plants (Brassica juncea) were treated with atrazine-loaded poly (epsilon-caprolactone) nanocapsules, the herbicidal effect was significantly increased relative to commercial atrazine, with a substantial decline in net photosynthetic rates and stomatal conductance, a significant increase in oxidative stress, and consequently weight loss and growth restriction of the tested plants (Cao et al., 2018). Polymeric nanoparticles (Kumar et al., 2017), silica nanoparticles (Cao et al., 2018) and other nanocarriers have also been developed as adapted release systems to transport pesticides in a regulated approach.

Nanoscale carriers are used to efficiently transport and unleash these organisms over time. Precision farming is a method of farming that increases crop yields while minimizing soil and water damage (Duhan et al., 2017). Most interestingly, nanoencapsulation will reduce herbicide dosage without sacrificing efficacy, which is good for the environment. Insect-resistant varieties are produced using nanoparticle-mediated gene or DNA transfer in plants, in addition to nanocarriers (Sekhon, 2014).

Furthermore, nanomaterials function as pesticides with increased sensitivity and toxicity, and metal oxide nanomaterials such as ZnO, TiO2, and CuO are being investigated for their intrinsic toxicity to protect plants from pathogenic infections. ZnO nanoparticles, for example, have been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of microorganisms including Fusarium graminearum (Dimkpa et al., 2013), Aspergillus flavus (Rajiv et al., 2013), A. niger, A. fumigatus, F. culmorum and F. oxysporium (Rajiv et al., 2013).

Poor nutrient absorption efficiencies and high losses plague traditional mineral fertilisers, but the production of nanofertilizers has provided an innovative alternative to such economic loss. Nanofertilizers can help crops and soil microorganisms consume more nutrients by reducing nutrient depletion and increasing nutrient incorporation (Dimkpa and Bindraban, 2018). At the nanoscale, commercialised nanofertilizers are mostly micronutrients like Mn, Cu, Fe, Zn, Mo, N, B). Other nanomaterials, like carbon nano-onions (Tripathi et al., 2017) and chitosan nanoparticles (Khalifa and Hasaneen, 2018), may be used instead of traditional crop fertilizers to improve crop quality and growth, and in the next decade, novel nanofertilizers are predicted to inspire and turn existing fertiliser processing industries.

Nanosensors, especially wireless nanosensors, have been developed to track crop diseases and development, nutrient production, and environmental conditions in the field due to the many beneficial aspects of nanomaterials. Engineered nanosensors, for example, can detect chemicals like pesticides and herbicides, in addition to pathogens in food and agricultural environments at a trace level and along with the proper use of nanofertilizer, nanopesticide, and nanoherbicides, an in situ and real-time monitoring device will help to mitigate possible crop losses and increase crop yield. According to a recent review, copper doped montmorillonite can be used for on-line testing of propineb fungicide in aquatic habitats (both fresh and salt water) with a detection limit of about 1 μm (Abbacia et al., 2014).

Food protection has increased as a result of the recognition of fungal nanobiotechnology in food production and storage. Many traditional chemicals used as food additives or wrapping materials have been discovered to occur in part at the nanometer scale and food-grade TiO2 nanoparticles, for example, have been discovered in the nanometer scale up to 40% (Dudefoi et al., 2017). Nanomaterials, like animal feed ingredients, are well engineered as colour or flavour additives, preservatives, or carriers for food supplements via nanoencapsulation and nanoemulsion. The specific properties of engineered nanomaterials have significant benefits for food production as additives or supplements, and nanoclay is one of the most commonly used and researched novel nanomaterials for food packaging due to its mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties, as well as its low cost.

Edible nanomaterial-encoded coatings have also shown their ability for food preservation and storage, with coated fresh food items like vegetables and fruits staying active during storage and transportation. As transportation and storage time increases, active respiration processes can cause major postharvest losses and low cosmetic and nutritional quality in products, but controlling such nutrition and weight loss is critical to extending the shelf life of fresh food products. The effects of relative humidity and temperature on fresh food respiration and microbial activity in goods are of the great importance. A thin coating of hybrid nano-edible films usually less than 100 nm thick, can be used as a gas and moisture barrier to enhance mechanical properties and sensory senses, avoid microbial spoilage, and prolong the shelf life of fresh foods (Flores-López et al., 2016).

Pesticides detection (Sahoo et al., 2018), pathogens detection (Sun et al., 2018a, b; Kearns et al., 2017; Percin et al., 2017), and toxins detection (Sun et al., 2018a, b; Zhang et al., 2017) are among the other applications in food packaging that are currently under active research and development due to the ultra-sensitive properties of nanomaterials as reported in Table 3 and according to a recent study by Sahoo et al. (2018), ZnO quantum dots (QD) can be used to identify a variety of pesticides, such as aldrin, tetradifon, glyphosate, and atrazine, since pesticides with heavy halogen groups (e.g. -Cl) react with QD easily and with a large binding affinity of 107 M−1. Moreover, during the interaction, ZnO QD can photocatalyze pesticides and other nanomaterials such as copper nanoparticles (Geszke-Mortiz et al., 2012), carbon nanotubes, gold nanoparticles (Lin et al., 2011), and silver nanoparticles (Jokar et al., 2016) have also been developed as nanosensors for real-time monitoring of food safety.

Table 3.

Fungi and properties of fungi-mediated nanoparticles used for application in agriculture, industries and others areas.

| Fungus species | Nanoparticles | Localization | Size (nm) | Shape | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botrytis cinerea | Au | Extracellular | 1–100 | Spherical, triangular, hexagonal, decahedral, pyramidal | - | Castro et al. (2014) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | ZnO | Extracellular | 1.2–6.8 | Spherical and hexagonal | Industrial and agricultural sectors | Raliya et al. (2013) |

| Hormoconis resinae | Ag | Extracellular | 20–80 | Cubic | - | Varshney et al. (2009) |

| Aspergillus oryzae | FeCl3 | - | 10–24.6 | Spherical | Agricultural and engineering sectors | Raliya (2013) |

| Aspergillus tubingensis | Ca3P2O8 | Extracellular | 28.2 | Spherical | Agricultural and engineering sectors | Tarafdar et al. (2012) |

| Rhizopus oryzae | Au | Cell surface | 10 | Nanocrystalline | Pesticides | Das et al. (2009) |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | Au | - | 1–5 | Irregularly (uniform) | - | Sarkar et al. (2012) |

| Aspergillus niger | Au | Extracellular | 10–20 | Polydispersed | - | Xie et al. (2007) |

| Aspergillus niger | Au | Extracellular | 12.79 ± 5.61 | Spherical | - | Bhambure et al. (2009) |

| Aureobasidium pullulans | Au | Intracellular | 29 ± 6 | Spherical | - | Zhang et al. (2011) |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Au | - | 20–40 | Decahedral and icosahedral | - | Shankar et al. (2013) |

| Fusarium semitectum | Au | - | 25 | Spherical | Optoelectronics | Sawle et al. (2008) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Au | - | 2–50 | Spherical, monodispersity | - | Zhang et al. (2011) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Au | Intracellular | 128 ± 70 a | Aggregates | - | Mandal et al. (2006) |

| Neurospora crassa | Au | - | 32 | Spherical | - | Castro-Longoria et al. (2011) |

| Verticillium sp. | Au | Cell wall | 20 ± 8 | Spherical | - | Mukherjee et al. (2001a, b) |

| Verticillium sp. | Au | Cytoplsmicmembran | 20 ± 8 | Quasihexagonl | - | Mukherjee et al. (2001a, b) |

| Verticillium luteoalbum | Au | Intracellular | <10 | Spheres and rods | - | Gericke and Pinches (2006) |

| Cylindrocladium floridanu | Au | Extracellular | 19.5 | Spherical | - | Narayanan and Sakthivel (2013) |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Au | Extracellular | 10–100 | Spherical | - | Sanghi et al. (2011) |

| Sclerotium rolfsii | Au | Extracellular | 25 | Triangles, decahedral, hexagonal and rods | - | Narayanan and Sakthivel (2011) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Au | Extracellular | 8–40 | Spherical and triangular | - | Mukherjee et al. (2002) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Au | Extracellular | 46.21 | Spherical, triangular | - | Shankar et al. (2004) |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Au | Extracellular | 8–40 | Spherical | - | Shankar et al. (2013) |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | Au | - | 1–5 | Irregularly | - | Binupriya et al. (2010) |

| Verticillium luteoalbum | Au | Intracellular | Various | Various | - | Gericke and Pinches (2006) |

| Coriolis versicolor | Au | Extra- and intracellular | 20–100, 100–300 | Spherical and ellipsoidal | - | Sanghi and Verma (2010) |

| Rhizopus oryzae | Au | - | Various | Triangular, hexagonal, pentagonal, spheroidal, sea urchin like, 2D nanowires, nanorods | - | Das et al. (2010) |

| Aspergillus niger | Au | - | Various | Plates, aggregates, spherical | - | Xie et al. (2007) |

| Aspergillus niger | Au | - | Various | Nanowalls, spiral plates, spherical | - | Xie et al. (2007) |

| Aspergillus niger | Au | - | 50–500 | Nanoplates | - | Xie et al. (2007) |

| Verticillum sp. | Ag | Intracellular | 25 | Spherical | - | Mukherjee et al. (2001a, b) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Ag | Extracellular | 5–15 | Highly variable | - | Ahmad et al. (2003) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Ag | - | 10–25 | Aggregates | - | Kumar et al. (2007a, b) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | Ag | - | 5–25 | Mostly spherical, some triangular | - | Bhainsa and D'Souza (2006) |

| Aspergillus flavus | Ag | On cell wall surface | 8.92 | Spherical | - | Vigneshwaran et al. (2007) |

| Trichoderma asperellum | Ag | - | 13–18 | Nanocrystalline | Agriculture | Mukherjee et al. (2002) |

| Penicillium fellutanum | Ag | Extracellular | 5–25 | Mostly spherical | - | Kathiresan et al. (2009) |

| Penicillium strain J3 | Ag | - | 10–100 | Mostly spherical | - | Maliszewska et al. (2009) |

| Cladosporium cladosporioides | Ag | - | 10–100 | Mostly spherical | - | Balaji et al. (2009) |

| Coriolis versicolor | Ag | Extra- and intracellular | 25–75, 444–491 | Spherical | - | Sanghi and Verma (2009) |

| Trichoderma viride | Ag | - | 2–4, 10–40, 80–100 | Spherical | - | Fayaz et al. (2009b) |

| Trichoderma viride | Ag | - | 2–4 | Mostly spherical | Biosensor and bio imaging | Fayaz et al. (2010a) |

| Trichoderma reesei | Ag | Extracellular | 5–50 | Spherical | - | Vahabi et al. (2011) |

| Aspergillus flavus NJP08 | Ag | - | 17 | Spherical | - | Jain et al. (2011) |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | Ag | - | 25–30 | Quasi-spherical | - | Binupriya et al. (2010) |

| Aspergillus terreus CZR-1 | Ag | Extracellular | 2.5 | Spherical | Agriculture and engineering sector | (Raliya and Tarafdar, 2012) and Tarafdar et al., 2012 |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Au–Ag | Extracellular | 8–14 | Quasi-spherical | - | Senapati et al. (2005) |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Fe3O4 | Extracellular | 20–50 | Irregular, quasi-spherical | - | Bharde et al. (2006) |

| Verticillium sp. | Fe3O4 | Extracellular | 100–400, 20–50 | Cubo-octahedral, quasi-spherical | - | Bharde et al. (2006) |

| Aspergillus flavus TFR7 | TiO2 | 12–15 | Extracellular | Plant nutrient | Raliya et al. (2015) | |

| Fusarium oxyporum | BT | Extracellular | 4–5 | Quasi-spherical | - | Bansal et al. (2006) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Cd | Extracellular | 9–15 | Spherical | - | Kumar et al. (2007a, b) |

| Fusarium oxyporum | Pt | - | 70–180 | Rectangular, triangular, spherical and aggregates | - | Govender et al. (2009) |

| Fusarium oxysporum, F. sp. lycopersici | Pt | Extra-and intracellular | 10–100 | Hexagonal, pentagonal, circular, squares, rectangles | - | Riddin et al. (2006) |

| Fusarium sp. | Zn | Intracellular | 100–200 | Irregular, some spherical | - | Velmurugan et al. (2010) |

| Aspergillus versicolor mycelia | Hg | Surface of mycelia | 20.5 ± 1.82 | Alteration | - | Das et al. (2008) |

| Fungi isolated from the soil | Zn, Mg and Ti | extracellular | Various | - | - | Raliya et al. (2013) |

3.3. Industrial application of fungal nanobiotechnology

Several fungi mediated nanoparticles are found useful in several industrial processes. In addition to the importance of fungi mediated nanoparticles to industries, such nanoparticles are secreted extracellularly in abundant amount in fungi. In addition to the suitability and attractiveness of fungal nanoparticles for industrial applications, fungi may live in harsh environments because they contain special enzymes capable of conducting chemically challenging reactions as reported by Viswanath et al. (2008). The leading fungi mediated nanoparticle applied in several industrial processes is the laccase. Although, laccase can be found in plants (Shraddha et al., 2011), insects (Kramer et al., 2001) and bacteria (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2013), laccase main source remain the fungi and several biological functions have been suggested for laccases in fungi, including spore tolerance and pigmentation (Williamson et al., 1998), lignification of plant cell walls (Malley et al., 1993), humus turnover, lignin biodegradation and detoxification processes (Baldrian, 2006), virulence factors, and copper and iron homeostasis (Stoj and Kosman, 2003).

Surprisingly, the majority of biotechnologically beneficial laccases (those with high redox potentials) are fungal, with laccase activity found in over 60 fungal strains of the Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, and Deuteromycetes families. Laccase production is strongest in lignin-degrading white-rot fungi (Shraddha et al., 2011), but litter-decomposing and ectomycorrhizal fungi also secrete laccases, and laccase provides a wide variety of oxidations, including non-phenolic substrates, in the presence of small redox mediators. As a result, fungal laccases are seen as ideal green catalysts with significant biotechnological effects since they need little resources to produce bioelectrocatalysis and only produce water as a byproduct (Kunamneni et al., 2008).

Laccase's biotechnological utility, on the other hand, can be enhanced by the use of a laccase-mediator device (LMS). Laccase and LMS have potential applications in delignification (Virk et al., 2012) and biobleaching of pulp (Weirick et al., 2014); enzymatic dye-bleaching and fibre modification in the textile and dye industries (Kunamneni et al., 2008); enzymatic removal of phenolic compounds in beverages—wine and beer stabilization, fruit juice processing (Minussi et al., 2002); and enzymatic cross linking of lignin-based materials in producing medium density fiberboards (Widsten et al., 2004); bioremediating and detoxifying of aromatic pollutants (Khambhaty et al., 2015); detoxifying of lignocellulose hydrolysates in producing ethanol via yeast (Larsson et al., 1999); treating of industrial wastewater (Viswanath et al., 2014); and constructing of biofuel cells and biosensors (Viswanath et al., 2014; Shraddha et al., 2011). Laccase has drawn a lot of attention because of its catalytic ability and possible biotechnological applications (Abdel-Hamid et al., 2013).

Laccase can also oxidize a diverse organic and inorganic compound, including mono, di, polyphenols, aminophenols, methoxyphenols, and metal complexes, which is why it is so useful in a variety of biotechnological processes. Laccases have recently sparked renewed interest due to their possible applications in pollutant detoxifying and phenolic compound bioremediating (Singh et al., 2011). With constant application in pulp and paper processing and the synthesis of fine chemicals, fungal enzymes can turn jet fuel (Viswanath et al., 2014), paint, plastic, and wood, among other materials, into nutrients (Viswanath et al., 2008).

Another fungal enzyme of great biotechnological importance is the xylanase and extracellular xylanases generated by microorganisms are extremely significant in industry, with cellulase, pectinase, and xylanase responsible for roughly 20% of world enzyme market (Polizeli et al., 2005). The world demand for industrial enzymes is said to have risen rapidly in recent years, from a projected $1 million in 1970 to a reported 4.5 billion dollars in 2012, with projections of about 7.1 billion dollars in 2018 (Kalim et al., 2015). Microbial enzymes, such as xylanases, are important in a variety of industries, ranging from food manufacturing to the paper and pulp industries (Azin et al., 2007). It plays an important role in a variety of biotechnological processes, including the clarity of fruit juice, the bleaching of beer and wine, the improvement of poultry feed digestibility, and the pulp, paper, leather, and baking industries (Uday et al., 2016). They're used to harvest extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and plant oils, as well as to improve the nutritional value of silage, coffee, green feed, and starch (Lakshmi et al., 2009). Furthermore, xylanase has been shown to be effective in the production of biofuel from lignocelluloses (Uday et al., 2016). The latest interest in green nanoparticle synthesis for important biomedical applications (Elegbede et al., 2018; 2019) has pushed the boundaries of enzyme technology in nanobiotechnology even further (Lateef and Adeeyo, 2015; Lateef et al., 2015; Adelere and Lateef, 2016) and different forms of fungi and bacteria are known to synthesize xylanases under various production processes, but filamentous fungi are the most successful producers of xylanase, as previously mentioned, since they secrete higher levels of enzymes than other microorganisms (Rani et al., 2014). Aspergillus and Trichoderma spp. are the main sources of xylanases on a commercial scale (Shahi et al., 2011).

In general, Aspergillus species have the ability to synthesize a wide variety of enzymes responsible for weakening plant cell walls, while Trichoderma spp., which are the primary agents responsible for the degradation and decomposition of agricultural wastes, have a wide range of enzymes and are thus regarded as outstanding lignocellulolytic enzyme producers (Azin et al., 2007). Xylanase activities of Aspergillus niger, A. flavus, Trichoderma longibrachiatum, A. fumigatus, F. solani, and Botryodiplodia sp. isolates were recently identified and used in dough raising and juice confirmation activities (Elegbede and Lateef, 2018). Other industrial uses of fungi mediated nanoparticles are reported in Table 3.

4. Challenges and way forward in fungal nanobiotechnology

Like every other aspect of nanobiotechnology, some challenges are facing the use of fungi and its metabolites to render goods and services to humankind. Some of these challenges are discussed below with some recommendations to improve the technology.

4.1. Existing challenges and recommended solutions in fungal nanobiotechnology

The major problem facing fungal nanobiotechnology is under exploration of fungi. As stated earlier in this chapter, only few fungi are well documented for their nanoparticles production potential and biology at large. This has somehow limited the full exploration of this great kingdom. Some fungi are not even culturable in the laboratory as the incubation conditions and media requirements are not fully understood or just cannot be met. Furthermore, optimization of fungal growth and nanoparticle production has remained a major challenge in this option of microbial nanobiotechnology.

Generally, nanobiotechnology faces the challenges of public acceptance; limited clinical research on long term exposure to nanoparticles and little or no legislation guiding nanoparticles application in most countries. Microbial nanobiotechnology tends to solve some of these problems but sadly the problems still abound in a way even with fungal nanobiotechnology. Beside titanium dioxide and iron oxide that are applied in food pigments and coloration, respectively, no other nanomaterials are included in human food (McClements and Xiao, 2017) and the main factor for this is that there are few constitutions or laws guiding nanofood and nanotechnology as a whole, for nanotechnology is complex and there is no in-depth legislation (Kavitha et al., 2018; Xiaojia et al., 2018). A stronger reason for the lack of regulation is a lack of understanding of the toxicity and danger that novel nanomaterials may pose (Deng et al., 2018; Dasari et al., 2014). Several researches on nanomaterial toxicity are in vitro, but there are very little data on in vivo toxicity, let alone chronic effects of nanomaterials (Duncan, 2011). At least a few holes must be filled: effects of nanomaterial exposure to mammalian cells, tissues/organs, and chronic effects on the human body; nanomaterial migration to food; nanomaterial depletion or environmental fate; nanomaterial bioaccumulation and ecological influence. Definitely, more investigations and adequate funding are going to be needed in this all-encompassing field.

Another critical factor is public acceptability which is mostly overlooked by scientists, producers, and government agencies (Arnaldi and Muratorio, 2013). It decides whether nanotechnology can be implemented and/or approved by customers in the long run and regardless of who accepts these novel nanomaterials, the waste will eventually be disposed into the atmosphere, causing unique effects on plants, animals and habitats. In making matters worse, neither researchers, nanoindustries nor governmental agencies have extensively discussed the proper disposal technique, resulting in a lack of in vivo toxicity data for nanomaterials, including the possible chronic impact on man organs.

More clinical research on the safety of fungi nanoparticles is important in making fungal nanobiotechnology widely acceptable to humans. Researches on fungal nanobiotechnology needs to be moved to the advanced stages of evaluating nanoparticles safety in vivo, possibly in volunteered human population. Furthermore, education of humans on the safety and benefits of nanoparticles is essential. Nanobiotechnology in general, should be embraced as the field may lead to prospects in some areas of human endeavor that looked like a dead-end in past years. More so, every country should provide strong legislation to guide and support nanoparticles usage in her economy.

5. Concluding remarks

Biological synthesis of nanoparticles is safe and relatively inexpensive. The synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using microbes had been shown to possess a strong potential with various applications. The utilization of fungi to fabricate nanoparticles has been greatly considered sequel to several advantages including easy handling and downstream processing. However, the interest of several researchers had been captivated of a recent towards the myconanofabrications of nanoparticles. Myconanofabrications of nanoparticles has been considered to be a structured and satisfactory method for the synthesis of various types of nanoparticles with a vast potential and remarkable applications in diverse fields such as agriculture, food, textile, medicine, cosmetics, optical and electronics. In the world today, several species of fungi are of great importance in nanobiotechnology due to the safe, ecofriendly, amenable and important nanoparticles they produced. Furthermore, the extracellular abundant production of the nanoparticles favours fungal nanobiotechnology among all microbial nanobiotechnology as it saves the cost of downstream process. Several researches in the field have further helped in the development of more novel principles and broader application of this nanobiotechnology in various human lives.

In this light, fungal nanobiotechnology has been applied in agriculture, medicine and in various industrial processes. Presently, fungal nanobiotechnology is integral in the management and control of fungal diseases in man, animals and plants. More so, food product formulation, shelf-life improvement and packaging have employed fungal nanobiotechnology greatly. Medically, fungi nanoparticles are important in drug delivery systems, diagnosis and treatment of resistant infections and cancer. Fungi-produced metal nanoparticles possess a lot of promise for use as sensors and electronic devices in biomedical imaging. Laccase and xylanase from fungi have found applications in diverse industries as important enzymes suggesting the usefulness of this technology in the improvement of quality of goods and services to humanity.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abbacia A., Azzouz N., Bouznit Y. A new copper doped montmorillonite modified carbon paste electrode for propineb detection. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014;90:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Aziz A.R.M., Al-Othman M.R., Mahmoud M.A., Metwaly H.A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Fusarium solani and its impact on grain borne fungi. Dig. J. Nanomater. Bios. 2015;10:655–662. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Hamid A.M., Solbiati J.O., Cann I.K. Insights into lignin degradation and its potential industrial applications. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;82:1–28. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407679-2.00001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo E.A., Azeez M.A., Alao M.B., Oke M.A., Aina D.A. In: Microbial Nanobiotechnology- Principles and Application. Lateef A., Gueguim-Kana E.B., Dasgupta N., Ranjan S., editors. Springer Nature Singapore Pte. Ltd; 2021. Mushroom nanobiotechnology: concepts, developments and potentials. [Google Scholar]

- Adelere I.A., Lateef A. A novel approach to the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles: the use of agro-wastes, enzymes and pigments. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016;5:567–587. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A., Mukherjee P., Mandal D., Senapati S., Khan M.I., Kumar R., Sastry M. Enzyme mediated extracellular synthesis of CdS nanoparticles by the fungus, Fusarium oxysporum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12108–12109. doi: 10.1021/ja027296o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A., Mukherjee P., Senapati S., Mandal D., Khan M.I., Kumar R., Sastry M. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2003;28:313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Alani F., Moo-Young M., Anderson W. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by a new strain of Streptomyces sp. compared with Aspergillus fumigatus. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28:1081–1086. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0906-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldi S., Muratorio A. Nanotechnology, uncertainty and regulation. A guest editorial. NanoEthics. 2013;7:173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Aygün A., Özdemir S., Gülcan M., Cellat K., Sen F. Synthesis and characterization of Reishi mushroom-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for the biochemical applications. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 2020;178:112970. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.112970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azin M., Moravej R., Zareh D. Production of xylanase by Trichoderma longibrachiatum on a mixture of wheat bran and wheat straw: optimization of culture condition by Taguchi method. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2007;40:801–805. [Google Scholar]

- Baldrian P. Fungal laccases—occurrence and properties. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:215–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-4976.2005.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji D.S., Basavaraja S., Deshpande R., Mahesh D.B., Prabhakar B.K., Venkataraman A. Extracellular biosynthesis of functionalized silver nanoparticles by strains of Cladosporium cladosporioides fungus. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2009;68(1):88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumaran M.D., Ramachandran R., Kalaicheilvan P.T. Exploitation of endophytic fungus, Guignardia mangiferae for extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their in vitro biological activities. Microbiol. Res. 2015;178:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal V., Poddar P., Ahmad A., Sastry M. Room-temperature biosynthesis of ferroelectric barium titanate nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11958–11963. doi: 10.1021/ja063011m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H., Lu Z., Cui X., Qiao Y., Guo J., Anderson J.M., Li C.M. Extracellular microbial synthesis of biocompatible CdTe quantum dots. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3534–3541. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabadi H., Tajani B., Moradi M., Kamali K.D., Meena R., Honary S., Saravanan M. Penicillium family as emerging nanofactory for biosynthesis of green nanomaterials: a journey into the world of microorganisms. J. Cluster Sci. 2019;30(4):843–856. [Google Scholar]

- Bhainsa K.C., D’Souza S.F. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2006;47:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhambure R., Bule M., Shaligram N., Kamat M., Singhal R. Extracellular biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using Aspergillus niger—its characterization and stability. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2009;32:1036–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Bharde A., Rautaray D., Bansal V., Ahmad A., Sarkar I., Yusuf S.M., Sanyal M., Sastry M. Extracellular biosynthesis of magnetite using fungi. Small. 2006;2:135–141. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava A., Jain N., Khan M.A., Pareek V., Dilip R.V., Panwar J. Utilizing metal tolerance potential of soil fungus for efficient synthesis of gold nanoparticles with superior catalytic activity for degradation of rhodamine B. J. Environ. Manag. 2016;183:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binupriya A.R., Sathishkumar M., Yun S.I. Biocrystallization of silver and gold ions by inactive cell filtrate of Rhizopus stolonifer. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2010;79:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birla S.S., Tiwari V.V., Gade A.K., Ingle A.P., Yadav A.P., Rai M.K. Fabrication of silver nanoparticles by Phoma glomerata and its combined effect against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009;48:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M. The fungi: 1, 2, 3 ….. 5.1 million species? Am. J. Bot. 2011;98:426–438. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourzama G., Ouled-Haddar H., Marrouche M., Aliouat A. Iron uptake by fungi isolated from arcelor mittal-annaba-in the northeast of Algeria. Brazil. J. Poult. Sci. 2021;23 [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Zhou Z., Niu S., Cao C., Li X., Shan Y. Positive-charge functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as nanocarriers for controlled 2, 4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid sodium salt release. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:6594–6603. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.E., Cottet L., Castillo A. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by extracellular molecules produced by the phytopathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mater. Lett. 2014;115:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Longoria E., Moreno-Velásquez S.D., Vilchis-Nestor A.R., Arenas-Berumen E., Avalos-Borja M. Production of platinum nanoparticles and nanoaggregates using Neurospora crassa. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;22:1000–1004. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1110.10085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Longoria E., Vilchis-Nestor A.R., Avalos-Borja M. Biosynthesis of silver, gold and bimetallic nanoparticles using the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2011;83:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S., Mahanty S., Das P., Chaudhuri P., Das S. Biofabrication of iron oxide nanoparticles using manglicolous fungus Aspergillus Niger BSC-1 and removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;385:123790. [Google Scholar]

- Chuhan A., Zubair S., Tufail S., Sherwani A., Sajid M., Raman S.C., Azam A., Owais M. Fungus-mediated biological synthesis of gold nanoparticles: potential in detection of liver cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:2305–2319. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S23195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo P., Meier S., Borie G., Rillig M.C., Borie F. Glomalin-related soil protein in a Mediterranean ecosystem affected by a copper smelter and its contribution to Cu and Zn sequestration. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;406:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Das A., Guha A. Adsorption behavior of mercury on functionalized Aspergillus versicolor mycelia: Atomic force microscopic study. Langmuir. 2008;25:360–366. doi: 10.1021/la802749t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.K., Das A.R., Guha A.K. Gold nanoparticles: microbial synthesis and application in water hygiene management. Langmuir. 2009;25:8192–8199. doi: 10.1021/la900585p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.K., Das A.R., Guha A.K. Microbial synthesis of multishaped gold nanostructure. Small. 2010;6:1012–1021. doi: 10.1002/smll.200902011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.K., Dickinson C., Laffir F., Brougham D.F., Marsili E. Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles biosynthesized with Rhizopus oryzae protein extract. Green Chem. 2012;14:1322–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Dasari T., Deng H., McShan D., Yu H. In: Nanosilver-based Antibacterial Agents for Food Safety. RP C., editor. NOVA Science Publishers; 2014. pp. 35–62. (Food Poisoning: Outbreaks, Bacterial Sources and Adverse Health Effects). [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Zhang Y., Yu H. Nanoparticles considered as mixtures for toxicological research. J. Environ. Sci. Health C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 2018;36:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10590501.2018.1418792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa C.O., Bindraban P.S. Nanofertilizers: new products for the industry? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:6462–6473. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa C.O., McLean J.E., Britt D.W., Anderson A.J. Antifungal activity of ZnO nanoparticles and their interactive effect with a biocontrol bacterium on growth antagonism of the plant pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Biometals. 2013;26:913–924. doi: 10.1007/s10534-013-9667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorcheh S.K., Vahabi K.V. In: Fungal Metabolites. Merillon J.-M., Ramawat, editors. Springer; Cham: 2016. Biosynthesis of nanoparticles by fungi: large-scale production; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dudefoi W., Terrisse H., Richard-Plouet M., Gautron E., Popa F., Humbert B. Criteria to define a more relevant reference sample of titanium dioxide in the context of food: a multiscale approach. Food Addit. Contam. 2017;34:653–665. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2017.1284346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhan J.S., Kumar R., Kumar N., Kaur P., Nehra P., Duhan S. Nanotechnology: the new perspective in precision agriculture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017;15:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan T.V. Applications of nanotechnology in food packaging and food safety: barrier materials, antimicrobials and sensors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;363:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran N., Marcato P.D., Alves O.L., de Souza G.I.H., Esposito E. Mechanistic aspects of biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by several Fusarium oxysporum strains. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2005;3 doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elegbede J.A., Lateef A. Valorization of corn-cob by fungal isolates for production of xylanase in submerged and solid-state fermentation media and potential biotechnological applications. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018;9:1273–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Elegbede J.A., Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Oladipo I.C., Adebayo E.A., Beukes L.S., Gueguim-Kana E.B., et al. Fungal Xylanase-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles forcatalytic and biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018;12(6):857–863. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2017.0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elegbede J.A., Lateef A., Azeez M.A., Asafa T.B., Yekeen T.A., Oladipo I.C., Abbas S.H., Beukes L.S., Gueguim-Kana E.B. Silver-gold alloy nanoparticles biofabricated by fungal xylanases exhibited potent biomedical and catalytic activities. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019;3 doi: 10.1002/btpr.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgorban A.M., Aref S.M., Seham S.M., Elhindi K.M., Bahkali A.H., Sayed S.R., et al. Extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus versicolor and evaluation of their activity on plant pathogenic fungi. Mycosphere. 2016;7:844–852. [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz A.M., Balaji K., Girilal M., Kalaichelvan P.T., Venkatesan R. Mycobased synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their incorporation into sodium alginate films for vegetable and fruit preservation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:6246–6252. doi: 10.1021/jf900337h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz A.M., Balaji K., Girilal M., Yadav R., Kalaichelvan P.T., Venketesan R. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their synergistic effect with antibiotics: a study against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2010;6:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz A.M., Balaji K., Kalaichelvan P.T., Venkatesan R. Fungal based synthesis of silver nanoparticles—an effect of temperature on the size of particles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2009;74:123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz M., Tiwary C.S., Kalaichelvan P.T., Venkatesan R. Blue orange light emission from biogenic synthesized silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma viride. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2010;75:175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-López M.L., Cerqueira M.A., de Rodríguez D.J., Vicente A.A. Perspectives on utilization of edible coatings and nano-laminate coatings for extension of postharvest storage of fruits and vegetables. Food. Eng. Rev. 2016;8:292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gabani P., Singh O.V. Radiation-resistant extremophiles and their potential in biotechnology and therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:993–1004. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahlawat G., Choudhury A.R. A review on the biosynthesis of metal and metal salt nanoparticles by microbes. RSC Adv. 2019;9(23):12944–12967. doi: 10.1039/c8ra10483b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajbhiye M., Kesharwani J., Ingle A., Gade A., Rai M. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against pathogenic fungi in combination with fluconazole. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2009;5:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gericke M., Pinches A. Microbial production of gold nanoparticles. Gold Bull. 2006;39:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Geszke-Moritz M., Clavier G., Lulek J., Schneider R. Copper-or manganese-doped ZnS quantum dots as fluorescent probes for detecting folic acid in aqueous media. J. Lumin. 2012;132:987–991. [Google Scholar]

- Goel A. Agricultural applications of nanotechnology. J. Biol. Chem. Res. 2015;32:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Govender Y., Riddin T., Gericke M., Whiteley C.G. Bioreduction of platinum salts into nanoparticles: a mechanistic perspective. Biotechnol. Lett. 2009;31:95–100. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9825-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilger-Casagrande M., Lima R.D. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by fungi: a review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019;7:287. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafy M.H. Myconanotechnology in veterinary sector: status quo and future perspectives. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2018;6(2):270–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ijvsm.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honary S., Barabadi H., Gharaei-Fathabad E., Naghibi F. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using Penicillium aurantiogriseum, Penicillium citrinum and Penicillium waksmanii. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biosci. 2012;7(3):999–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Hulikere M.M., Joshi C.G. Characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using marine endophytic fungus-Cladosporium cladosporioides. Process Biochem. 2019;82:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M., Oyebanji E., Fowora M., Aiyeolemi A., Orabuchi C., Akinnawo B., Adekunle A.A. Extracts of endophytic fungi from leaves of selected Nigerian ethnomedicinal plants exhibited antioxidant activity. BMC Compl. Med. Ther. 2021;21(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03269-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]