Abstract

Biological systems are heterogeneous and crowded environments. Such packed milieus are expected to modulate reactions both inside and outside the cell, including protein oxidation. In this work, we explored the effect of macromolecular crowding on the rate and extent of oxidation of Trp and Tyr, in free amino acids, peptides and proteins. These species were chosen as they are readily oxidized and contribute to damage propagation. Dextran was employed as an inert crowding agent, as this polymer decreases the fraction of volume available to other (macro)molecules. Kinetic analysis demonstrated that dextran enhanced the rate of oxidation of free Trp, and peptide Trp, elicited by AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals. For free Trp, the rates of oxidation were 15.0 ± 2.1 and 30.5 ± 3.4 μM min−1 without and with dextran (60 mg mL−1) respectively. Significant increases were also detected for peptide-incorporated Trp. Dextran increased the extent of Trp consumption (up to 2-fold) and induced short chain reactions. In contrast, Tyr oxidation was not affected by the presence of dextran. Studies on proteins, using SDS-PAGE and LC-MS, indicated that oxidation was also affected by crowding, with enhanced amino acid loss (45% for casein), chain reactions and altered extents of oligomer formation. The overall effects of dextran-mediated crowding were however dependent on the protein structure. Overall, these data indicate that molecular crowding, as commonly encountered in biological systems affect the rates, and extents of oxidation, and particularly of Trp residues, illustrating the importance of appropriate choice of in vitro systems to study biological oxidations.

Keywords: Macromolecular crowding, Protein oxidation, Chain reactions, Tryptophan, Tyrosine, Peroxyl radicals

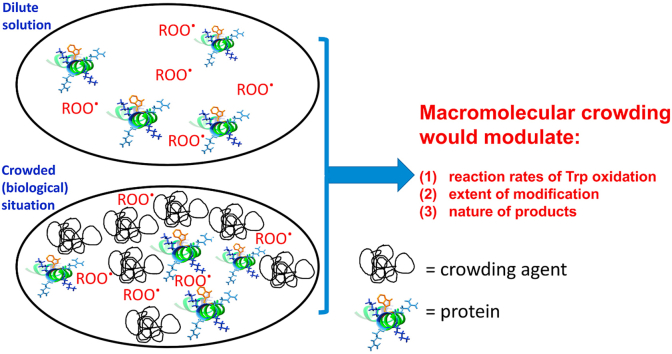

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Biological systems are crowded, complex and heterogeneous milieus dominated by interfacial chemistry.

-

•

Macromolecular crowding may modulate biochemical reactions including protein oxidation.

-

•

Increased rates and extents of tryptophan oxidation are detected in the presence of crowding agents.

-

•

Chain-carrying species generated from tryptophan can oxidize other targets.

-

•

Molecular crowding enhances oxidation by modulating chain termination reactions.

1. Introduction

Protein oxidation and peroxidation are common processes in biological environments, as a consequence of protein exposure to endogenous or exogenous oxidants. Under normal conditions, biological systems limit these biochemical reactions through diverse mechanisms (e.g. low-molecular-mass scavengers, and enzymes that remove oxidants, repair damage, or catabolize damaged proteins). Nevertheless, there exist abundant evidence for the accumulation of oxidatively-modified proteins in pathological conditions [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. Biologically relevant oxidants include radicals (e.g. peroxyl (ROO•), O2−•, NO•, •OH) or two-electron-oxidants (e.g. H2O2, ONOOH, HOCl, 1O2). The high concentration of proteins in cells (2–4 million protein molecules per cubic micron in both bacteria and mammalian cells [5]), and the high reactivity of some amino acid residues - particularly those containing sulfur atoms or aromatic motifs - make these a common and important target for most oxidants [6]. Radical-mediated oxidation of proteins (P-H) results in the formation of secondary protein-alkyl radicals (P•) as a result of hydrogen atom abstraction, or electron transfer process. Thereafter, P• typically react with O2 generating protein-peroxyl radicals (P-OO•) and subsequently hydroperoxides, P-OOH, via further hydrogen atom abstraction reactions with P-H. Thus, both P• and P-OO• can contribute to the propagation of (modest) radical-chains and damage (protein peroxidation) [[6], [7], [8]].

Propagation of damage involving secondary radicals formed on the side chains of Trp, and Cys has been demonstrated in model systems (free amino acids [9,10], peptides [9], and diluted [11,12] or concentrated solutions of commercial proteins [13,14]). Nevertheless, there is little evidence, to our knowledge, of the occurrence and significance of these reactions in other multicomponent environments. In general, biological systems have higher protein concentrations (in the mM range, and therefore very crowded) than those commonly employed in biochemical and biophysical experiments in vitro (often low μM) [15], and multiple different macromolecules contribute to this crowding [16]. This would be expected to modulate interactions and reactions of proteins in a significant manner. Recently, Aicardo and coworkers reported that the exposure of highly concentrated solutions of bovine serum albumin (≤4.5 mM protein, and in the absence or presence of PEG) to peroxynitrite and metmyoglobin/H2O2 in aerobic milieus favors propagation of damage within protein molecules by formation of secondary P-OO• [13]. This work was one of the first to illustrate the importance of studying the effect of macromolecular crowding on protein oxidation. Similarly, exposure of intrinsically disordered casein proteins at relatively high concentrations (up to 1.2 mM) to AAPH-derived peroxyl radicals (ROO•) and RF/light showed analogous results with enhanced ratios of amino acid loss per radical generated, and evidence of short chain reactions [14].

These reports highlight the increasing interest in understanding the dynamic heterogeneity of crowded milieus and how these influence protein biophysics and biochemical reactions [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. It has been demonstrated that the local viscosity at biological interfaces is increased when compared to homogeneous aqueous solutions [23], with this having consequences for both solvent diffusion near to biological surfaces (e.g. proteins or membranes [23,24]), and for the diffusion of larger molecules, with this expected to be much slower than in bulk water [23]. Small oxidants of moderate reactivity, and no net charge (e.g. 1O2 in cells [25]), appear to diffuse relatively freely in biological systems until they react with a target, though it is unclear whether this occurs at the same rate as in dilute aqueous solutions. For larger (and potentially charged) oxidants, such as ROO• generated during lipid or protein peroxidation, slower motion is expected, and this would be expected to affect inter-molecular propagation of damage. Such motional constraints may have minimal effects on local damage (e.g. within, or between, proteins in close proximity/in complexes).

In this study we hypothesized that macromolecular crowding might affect the rates, mechanisms and products of oxidative damage to amino acids, peptides and proteins. This was examined by examining the rate and extent of Trp and Tyr oxidation in free amino acids, peptides and proteins, and the yield and the nature of the products formed. These amino acids were chosen for study because they possess readily oxidized indole (Trp) and phenol (Tyr) moieties in their side chains, making these major targets for many oxidants. These residues are therefore major intermediates in oxidation processes, and can act as oxidant ‘sinks’ [6,26]. Oxidation of both species generates intermediate radicals (R• or ROO•) that can contribute to the propagation of damage via hydrogen atom abstraction, or by undergoing electron transfer processes, with these reactions resulting in either additional damage, or alterations in the site of damage [[6], [7], [8],27]. The effects of steric interactions, and charge were examined by comparison of data for free amino acids with peptides (e.g. Gly-Trp-Gly, Lys-Trp-Lys, Gly-Tyr-Gly and Lys-Tyr-Lys), and model proteins containing a single Trp residue (melittin), a single Tyr residue (ubiquitin) or multiple targets (β-casein, one Trp and four Tyr). The effects of molecular crowding were examined using dextran (0, 30, 60 or 120 mg mL−1, average molecular mass 35,000–45,000 or 150,000) as this polysaccharide has well-defined chemical and physical properties and is poorly reactive with the oxidants under study [20,[28], [29], [30]]. High dextran concentrations have been shown to generate two phenomena in solution: (1) exclusion-volume and (2) depletion forces, that affect reactions at biological interfaces [31]. Oxidation was initiated by the thermo-labile azocompound 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine), AAPH, which generates defined R• and ROO• at a constant and known rate [32].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

L-Tryptophan (Trp), l-tyrosine (Tyr), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), β-casein from bovine milk (>98% purity), 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH), dextran from Leuconostoc. mesenteroides (average molecular masses, Mw, of 35,000–45,000, and 150,000) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Denmark). Gly-Trp-Gly, Lys-Trp-Lys, Gly-Tyr-Gly and Lys-Tyr-Lys were obtained from Bachem (Switzerland). Melittin (>98% purity) was purchased from Abcam (UK). Recombinant human ubiquitin (>95% purity) was purchased from R&D Systems (Denmark).

2.2. Preparation of solutions containing the crowding agent

Solutions containing the crowding agent dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000, or Mw 150,000) at concentrations of up to 120 mg mL−1 were prepared in 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Stock solutions of Trp, Tyr, Gly-Trp-Gly, Lys-Trp-Lys, Gly-Tyr-Gly, Lys-Tyr-Lys, melittin, ubiquitin, β-casein and AAPH were prepared in, and diluted with, these buffers. Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Sigma Aldrich) was utilized as chelating agent in order to minimize reactions of trace transition metal ions.

2.3. Characterization of the crowded solutions

The possible formation of microdomains, a characteristic of biological systems, was investigated in dextran-containing solutions using the fluorescent probe pyrene (λex: 337 nm) as this dye is sensitive to local environments [33]. The ratio between the fluorescence intensities of bands I1 (372 nm) and I3 (382 nm) of the emission spectrum of pyrene (1 μM) was used to evaluate the polarity of the local environment of the solutions containing dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) over the concentration range 0.001–120 mg mL−1 [34]. These analyses were carried out using a PerkinElmer LS-55 spectrofluorimeter (Beaconsfield, UK).

2.4. Determination of the rate of formation of peroxyl radicals in diluted and crowded systems

Solutions of Trolox (0.05–1.5 mM), prepared in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.0) or phosphate buffer with 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) were incubated with 10 and 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C. Every 15 min, air was bubbled for 20 s. At defined times (0, 30, and 60 min) aliquots (200 μL) were taken and analyzed by HPLC with a diode array detector (DAD) at 220 and 290 nm. Trolox consumption was determined from the decrease in the area under the curve (AUC) of the chromatographic peaks (retention time 8.1 min) against a calibration curve generated under the same experimental conditions, but in the absence of the oxidant. Samples were analyzed using an Agilent 1200 system equipped with an Agilent 1260 series auto sampler (with samples kept at 4 °C) and an Agilent 1260 series DAD. Samples (20 μL) were separated on a reversed phase column (Hibar® 250 × 4.3 mm RP-18 endcapped, particle size 5 μm; Phurospher®STAR, Millipore), at 35 °C, and eluted using buffer A: 10 mM KH2PO4 (pH 2.6, adjusted with orthophosphoric acid), and buffer B: acetonitrile, in a 60:40 (A:B) ratio, at a flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1.

Tyr consumption was also analyzed by HPLC with aliquots (4 μL) injected on to a reversed phase column (Phenomenex Kinetex 2.6 μm EVO 150 × 3 mm) maintained at 30 °C, and separated using buffer A: 100 mM sodium perchlorate (in 10 mM H2PO4) and buffer B (pH 2.6, adjusted with orthophosphoric acid), and buffer B: 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol in a 40:60 (A:B) ratio, at a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1. All experiments were carried out under an atmosphere of air with an O2 concentration of 237 μM [35].

2.5. Kinetic analysis of Trp and Tyr consumption by fluorescence spectroscopy

The kinetic profiles of Trp and Tyr consumption (both free amino acids and in peptides) induced by AAPH-derived radicals were examined by fluorescence spectroscopy. Reaction mixtures containing Trp or Tyr (50 μM–500 μM) with AAPH (10–100 mM) were incubated in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.0) in the absence or presence of crowding agent at 37 °C. Trp consumption was evaluated by the decrease in fluorescence emission intensity at 365 nm (with λex 295 nm) whilst Tyr consumption was evaluated in a similar manner via fluorescence emission at 304 nm (λex 274 nm). Data were obtained every 60 s on a SpectraMax® i3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA) kept at 37 °C, and programmed to shake samples (5 s) between readings. No changes in the fluorescence of Trp or Tyr were observed in the absence of AAPH (data not shown).

The initial rates (μM min−1) of Tyr and Trp oxidation in diluted and crowded systems were determined from the initial tangent of the time-course curves, whilst the total consumption of the amino acids was determined by the loss in the fluorescence after 30 min of incubation [9].

2.6. Oxygen consumption analysis

Solutions of AAPH (100 mM) in phosphate buffer 200 mM, pH 7.0 were incubated in a thermostated cell at 37 °C. O2 consumption was assessed employing an Oxygraph Plus System, Hansatech-Instruments® (Norfolk, UK). The rate of consumption was determined by measuring the decrease in O2 concentration as a function of time. The response of the electrode to O2 was equal in samples containing 0, 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran, implying that the initial concentration of O2 was not affected by the presence of the crowding agent.

2.7. SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis

Protein modifications were examined by SDS–PAGE electrophoresis. Control and oxidized samples (in absence and presence of 60 or 120 mg mL−1 dextran Mw 35,000–45,000) were heated for 5 min at 70 °C with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer. 4–12% Bis-Tris acrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and NuPAGE MES SDS running buffer were used, with electrophoresis performed at 160 V for 45 min. Gels were subsequently stained with colloidal Coomassie blue overnight, and images recorded using an Azure Biosystems (USA) imager. For immunoblotting analyses, gels were blotted to a PVDF membrane after electrophoresis using an iBlot 2 system (Thermo Fisher, 25 V, 6 min). The membranes were then incubated with a primary monoclonal anti-di-tyrosine antibody (1:1000 diluted in 1% BSA/TBST, overnight, 4 °C) and secondary anti-mouse-HRP conjugates (1:4000 in 1% BSA/TBST, 2 h, 25 °C). Chemiluminescence generated using an ECL plus solution was recorded using an Azure Biosystems (USA) imager.

2.8. Quantification of amino acid loss and formation of oxidation products

The loss of parent amino acids, and formation of oxidation products of Trp and Tyr were quantified by LC-MS using two different approaches. Control and oxidized samples were either subjected to trypsin digestion, with subsequent peptide analysis as described previously [36] and below, or subjected to acid hydrolysis to release free amino acids and products as described by Gamon et al. [37].

Prior to hydrolysis, protein samples (30 μg) were precipitated with TCA (10% w/v) in glass tubes. Aliquots of a mixture of 17 stable isotope-labelled amino acid standards (2500 pmoles), and [13C18, 15N2] diTyr, l–DOPA–d3, and l–kynurenine–d4 (final concentration 100 pmoles) were added to each tube. These solutions were dried down using a centrifugal vacuum concentrator at 30 °C for 60 min and re-suspended in 50 μL of 4 M methanesulfonic acid containing 0.2% w/v tryptamine. The glass tubes were placed into pico tag hydrolysis vials and submitted to three N2 – vacuum cycles of 1 min N2, and 10 min vacuum to remove O2 and prevent artefactual oxidation. Hydrolysis was carried out overnight at 110 °C. Thereafter, amino acids were partially purified by solid–phase extraction using 30 mg mL−1 mixed–mode strong cation exchange Strata X–C cartridges (Phenomenex) as described previously [37]. Columns were activated with methanol (1 mL) and equilibrated with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in ultrapure water (1 mL) before adding the samples (10 μL sample hydrolysate in 1 mL 0.1% formic acid). Samples were washed with 0.6 mL of 0.1% formic acid in water, and 0.6 mL 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile. Finally, elution was performed adding 0.6 mL of a solution containing 1% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide, and 20% (v/v) acetonitrile in water. The eluted fractions were dried down at 30 °C under vacuum, and then resuspended in 50 μL of 0.1% formic acid in water. Quantification of the analytes was achieved by ESI LC–MS in positive mode using a Bruker Impact HD II mass spectrometer. Samples were separated by gradient elution using an Imtakt Intrada amino acid column (100 × 3.0 mm) with 0.3% formic acid in acetonitrile (Solvent A) and 100 mM ammonium formate in 20% acetonitrile (Solvent B). The gradient was initiated with 20% B for 4 min before increasing to 100% B over 10 min, 100% B for 2 min, then returning to 20% Solvent B over 2 min, and re-equilibration for 2 min. The electrospray needle was held at 4500 V, with end plate set at 500 V, and a temperature of 350 °C. N2 gas was used was used for both the nebulizer (2.0 bar) and the dry gas (11.0 L min−1). MS analyses and quantification were carried out at the MS1 level using QuantAnalysis software (Bruker). To minimize concentration variations arising from protein hydrolysis, the data were normalized to the number of moles of Val (or Ala), quantified in each sample, as these residues are not significant targets for ROO•. Data are expressed as moles of residue per mole of protein [6].

2.9. Analysis of intact protein samples and tryptic peptides by LC-MS

Loss of parent Trp and Tyr residues, and formation of oxygenated products was examined by analysis of the intact protein (for melittin) and tryptic peptides (for ubiquitin and β-casein) as described previously, with minor modifications [36]. Control and oxidized protein samples (15 μg) were dried down at 30 °C under vacuum, and then re-suspended in 20 μL of 8 M urea in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0. These solutions were incubated for 30 min at 21 °C before adding 74 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 3 μL of 0.1 μg μL−1 trypsin. Samples were subsequently incubated overnight at 37 °C. The resulting peptides from control and oxidized samples were subjected to StageTip solid-phase extraction on activated Empore C18 reversed–phase discs (3 M, St. Paul, MN). Elution from the discs was achieved using 0.5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid in 80% (v/v) acetonitrile. The eluent was then dried down (Speedvac™ concentrator, 30 min) and samples re-suspended in 40 μL 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water. Samples were analyzed on an Impact II ESI-QTOF (Bruker Daltonics) mass spectrometer in the positive ion mode connected online to a Dionex Ultimate 3000 chromatography systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Analytes were separated using a MabPac column (150 mm × 150 μm column; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 60 °C using a flow rate of 10 μL min−1 and gradient elution using 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (Solvent A) and 80% (v/v) acetonitrile/0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (Solvent B). The electrospray needle was held at 4500 V, with end plate offset of 500V and temperature of 200 °C. Nitrogen gas was used for both the nebulizer (0.7 Bar) and as the dry gas (6.0 L min−1). MS1 precursor scans (150–2200 m/z) were followed by data dependent MS/MS fragmentation of the three most intense precursors with sampling rates of 2 Hz.

Data analysis was performed using DataAnalysis software (Bruker) for melittin, and MaxQuant (version 1.6.1.0) for ubiquitin and β-casein. Semi-specific tryptic constraints were selected at a 1% peptide level false discovery rate for MaxQuant. Variable modifications were searched for on: Trp (m/z +4, kynurenine, Kyn; m/z +14, carbonyl formation; m/z +16, addition of one oxygen atom; m/z +32, addition of 2 oxygen atoms), Tyr (m/z +16, DOPA), Met (m/z +16, m/z +16, addition of one oxygen, sulfoxide) and His (m/z +16, addition of one oxygen). The % modification at a particular site was determined based on label–free quantification of the total MS1 area ratios of the corresponding modified or non–modified peptides, as determined using Bruker QuantAnalysis software.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means + SD from at least three independent replicates. To reduce the complexity of some figures, only representative kinetic profiles of the replicates are shown. Statistical analyses were carried out using the packages available in OriginPro 8.5, using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test. p < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of solutions containing dextran

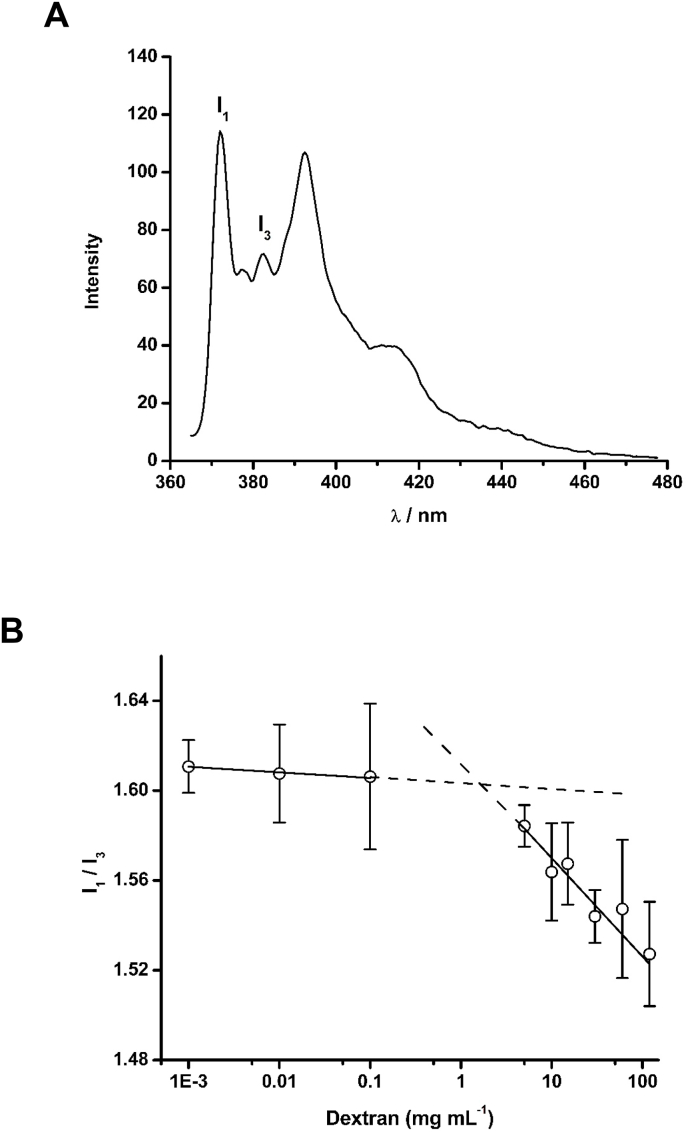

Dextran is a hydrophilic polysaccharide polymer that has been widely employed to generate excluded volume phenomenon, a characteristic property of biological systems, for in vitro studies [38,39]. To investigate the possible formation of microdomains in solutions containing this polymer, pyrene (1 μM) was used as a probe as its fluorescence spectrum (Fig. 1A) is sensitive to changes in the micropolarity and hydrophobicity of the region in which it is solubilized [33]. From the decrease in the ratio of the fluorescence intensities of the bands I1 and I3 (i.e. I1/I3) of pyrene it was possible to identify the presence of microdomains in solutions containing dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) at concentrations greater than ∼5 mg mL−1 (Fig. 1B), in agreement with previous reports [34].

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence spectrum (λex 337 nm) of 1 μM pyrene prepared in 200 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (Panel A), and I1/I3 ratio of the vibronic band intensities of pyrene as a function of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) concentration (Panel B).

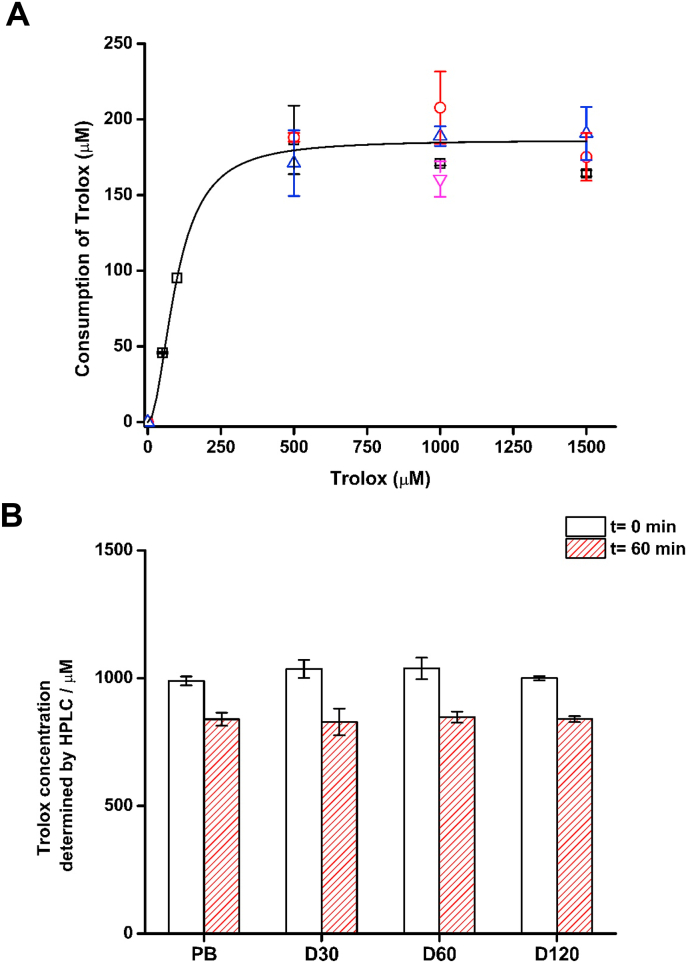

3.2. Determination of the rate of formation of ROO• upon thermolysis of AAPH under dilute and crowded conditions

Decomposition of AAPH in aqueous solutions generates alkyl radicals (R•) which react with O2, through a diffusion-controlled reaction (k ∼ 109 M−1 s−1), producing ROO• at a known and constant rate at 37 °C in phosphate buffer [32]. From these values a rate of formation of ROO• (RROO•) of 0.8 and 8 μM min−1 can be calculated for 10 and 100 mM AAPH respectively [40]. As changes in viscosity may affect the efficiency of escape of R• from the solvent cage resulting in a lower rate of formation (and decreased dose) of ROO• in comparison to phosphate buffer [41], experiments were carried out to investigate whether added dextran modulated the extent of formation of ROO•. Consumption of Trolox, a water-soluble analogue of vitamin E, mediated by AAPH-derived ROO• was quantified in both the absence and presence of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000), using a stoichiometry of 2 ROO• trapped per Trolox molecule [42]. Fig. 2A depicts the dependence of the total consumption of Trolox, on incubation with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C, at different initial Trolox concentrations in phosphate buffer in the absence or presence of 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000). At low concentrations (<500 μM), the extent of oxidation of Trolox depends on its initial concentration, whereas at higher concentrations the extent of oxidation of Trolox was independent of its initial concentration indicating complete scavenging of all ROO•. Under these conditions, the extent of consumption was independent of the presence or absence of dextran (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B depicts the residual Trolox concentration, as quantified by HPLC, after incubation of 1 mM Trolox, without or with 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran, at time zero (t0) or 60 min (t60) with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C. At this concentration, and also at 0.5 and 1.5 mM (data not shown) no significant differences were observed in Trolox consumption induced by AAPH-derived ROO• in the absence and presence of dextran, though statistically-significant losses in Trolox were detected for each sample between the t0 and t60 samples, as expected. Thus, in phosphate buffer 184 ± 15 μM of Trolox were consumed, with similar values determined in the presence of 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) (Fig. 2B). The absence of any differences at different dextran concentrations is consistent with dextran not affecting the rate or extent of ROO• generation.

Fig. 2.

The molecular crowding agent dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) does not affect the rate or extent of formation of ROO• from the thermo-labile azocompound AAPH. Total doses of ROO• generated from AAPH thermolysis at 37 °C in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.0) were determined from the consumption of Trolox (50–1500 μM) in the absence and presence of dextran as described in materials and methods. Panel (A): Dependence of the initial consumption of Trolox with its initial concentration in phosphate buffer in the absence (black), or presence of 30 mg mL−1 (red), 60 mg mL−1 (blue) or 120 mg mL−1 (magenta) dextran. Panel (B): Total consumption of Trolox (1000 μM) after 0 and 60 min of incubation in the presence of 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C under 20% O2 in phosphate buffer (PB), and 30 mg mL−1 (D30), 60 mg mL−1 (D60) and 120 mg mL−1 (D120) dextran. Data are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments. In panel B, no significant differences were observed between the samples at identical time points, with the same Trolox concentration, but each of the t = 60 min samples was significantly different to its corresponding t = 0 min control (p < 0.05). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

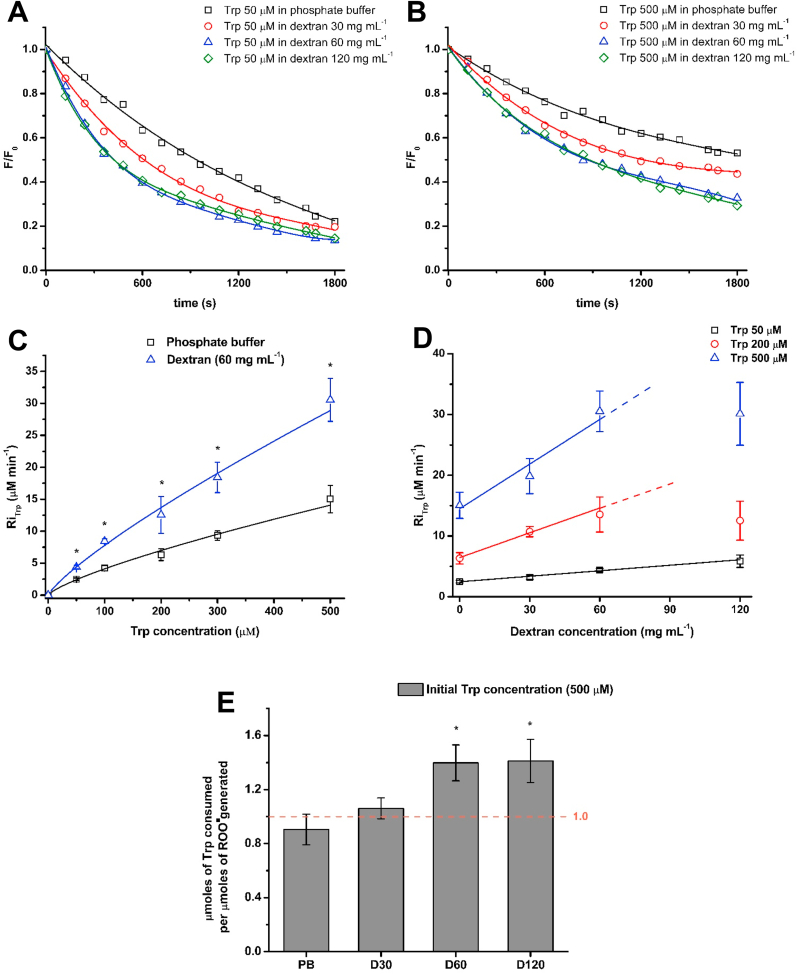

3.3. Effects of macromolecular crowding on the rate and extent of Trp and Tyr consumption

Taking advantage of the inherent fluorescent properties of Tyr and Trp, we analyzed the decay in the fluorescence intensity of the parent amino acids on incubation with AAPH in the absence and presence of dextran. This approach has been used extensively to determine the rate and extent of Trp and Tyr consumption [9,[43], [44], [45], [46]]. As depicted in Fig. 3A, the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp (50 μM) was efficiently depleted, over time, on incubation with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C. After 30 min a decrease of ∼78, ∼82 and ∼87% of the initial fluorescence was determined for solutions incubated in phosphate buffer, and 30 and 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000), respectively (Fig. 3A). The kinetic profiles of decay of the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp (50 μM) were similar in 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 3A). Incubation of Trp with 100 mM AAPH at higher amino acid concentrations (500 μM) showed similar effects with an enhanced depletion of fluorescence in crowded versus diluted systems. After 30 min, decreases of ∼48, ∼56 and ∼68% of the initial fluorescence were determined for solutions incubated in phosphate buffer, and 30 and 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000), respectively (Fig. 3B). From these kinetic profiles, the initial rate of Trp consumption (RiTrp) was determined [9]. RiTrp values of 10.1 ± 0.9 μM min−1 and 11.1 ± 1.9 μM min−1 were determined for incubation of Trp (500 μM) with 10 mM AAPH in the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, respectively (Table 1). Increasing the concentration of AAPH to 100 mM resulted in RiTrp values of 15.0 ± 2.1 μM min−1 and 30.5 ± 3.4 μM min−1, respectively (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 3C the RiTrp obtained on incubation of different Trp concentrations (50–500 μM) with 100 mM AAPH in presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) was significantly higher than the RiTrp obtained in absence of the crowding agent. For samples containing 50 μM Trp and 100 mM AAPH, a 1.8-fold increase in RiTrp was determined between the absence and the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (2.5 ± 0.3 to 4.4 ± 0.3 μM min−1), respectively (Fig. 3C), with an intermediate value (3.2 ± 0.3 μM min−1) determined for 30 mg mL−1 dextran (data not shown). These increases in RiTrp indicate that macromolecular crowding enhances the rate of Trp consumption. As shown in Fig. 3D, RiTrp also increased in a linear manner as the concentration of dextran was increased up to 60 mg mL−1 with, for the 500 μM Trp condition incubated with 100 mM AAPH, an increase from 15.0 ± 2.1 μM min−1 (phosphate buffer) to 19.9 ± 2.9 (30 mg mL−1 dextran), 30.5 ± 3.3 μM min−1 (60 mg mL−1 dextran) and 30.1 ± 5.2 μM min−1 (120 mg mL−1 dextran) detected (Fig. 3D). Along with the increased RiTrp detected in presence of dextran, an increase in Trp loss was evident after 30 min of incubation of Trp (500 μM) with 100 mM AAPH, with a loss of 217.2 ± 27.0 and 336.5 ± 22.0 μM of Trp detected in the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, respectively (Table 1). Interestingly, no significant differences were observed on the rate and extent of Trp oxidation in presence of 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) consistent with a plateau effect.

Fig. 3.

Macromolecular crowding enhances the initial rate and the overall extent of consumption of Trp residues. The initial rate of Trp consumption (RiTrp) was determined in the absence or presence of the crowding agent dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) by following the loss of the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp (λex: 295 nm; λem: 360 nm). The length of radical chain reactions was determined from the ratio of the total number of μmoles of Trp consumed per μmoles of ROO• generated after 30 min of incubation in presence of AAPH (100 mM) at 37 °C. Panel A: Kinetic profiles of Trp (50 μM) consumption on incubation with AAPH (100 mM) in phosphate buffer, 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran. Panel B: Kinetic profiles of Trp (500 μM) consumption on incubation with AAPH (100 mM) in phosphate buffer, 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran. Panel C: RiTrp elicited by radicals derived from AAPH (100 mM) in phosphate buffer in the absence (black squares) or presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (blue triangles). Panel D: Linear fit of RiTrp values as a function of the concentration of the crowding agent dextran at different Trp concentrations. Panel E: Ratio of total Trp consumption (μmoles) per total dose (μmoles) of ROO• generated upon AAPH thermolysis in phosphate buffer, 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran. Data are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicates data significantly different (p < 0.05) to the samples incubated in absence of dextran. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Initial rates (Ri) of Trp (W, 500 μM) and Tyr (Y, 500 μM) consumption, extent of consumption after 30 min of incubation, and μmoles of Trp/Tyr consumed per total dose (μmoles) of ROO● generated after 30 min of incubation elicited by AAPH (10 and 100 mM) derived radicals. Reactions were carried out in phosphate buffer in the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) at 37 °C, with Trp/Tyr consumption determined by the loss of intrinsic fluorescence from these residues. For Tyr, consumption was only determined with 100 mM AAPH.

| Ri (μM/min) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [AAPH] | W | GWG | KWK | Y | GYG | KYK | |

| Phosphate buffer | 10 mM | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 9.9 ± 0.8 | 11.8 ± 1.4 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 15.0 ± 2.1 | 14.9 ± 1.0 | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 12.0 ± 0.8 | |

| Dextran (60 mg mL−1) | 10 mM | 11.1 ± 1.9 | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 13. 1 ± 1.2 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 30.5 ± 3.4 | 19.0 ± 1.2 | 21.0 ± 2.2 | 14.4 ± 0.9 | 12.2 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 1.3 | |

| Consumption (μM) after 30 min | |||||||

| Phosphate buffer | 10 mM | 93.5 ± 4.0 | 60.0 ± 9.1 | 92.1 ± 8.9 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 217.2 ± 27.0 | 214.0 ± 9.7 | 241.4 ± 9.6 | 161.5 ± 12.5 | 153.7 ± 19.8 | 148.6 ± 16.7 | |

| Dextran (60 mg mL−1) | 10 mM | 139.5 ± 8.5 | 83.0 ± 12.9 | 126.2 ± 14.4 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 336.5 ± 22.0 | 259.2 ± 15.1 | 304.9 ± 12.1 | 173.0 ± 11.5 | 158.6 ± 9.4 | 151.2 ± 13.4 | |

| μmoles of Trp/Tyr consumed per total dose (μmoles) of ROO● generated after 30 min of incubation | |||||||

| Phosphate buffer | 10 mM | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

| Dextran (60 mg mL−1) | 10 mM | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | – | – | – |

| 100 mM | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | |

As the doses of ROO• generated from AAPH thermolysis are similar in the absence or presence of dextran (Fig. 2), the ratio of the μmoles of Trp consumed per μmole of ROO• generated, after 30 min of incubation, was calculated using the values of ROO• formation of 0.8 and 8.0 μM min−1 for 10 and 100 mM AAPH, respectively (Fig. 3E). These data indicate the presence of radical chain reactions in both phosphate buffer and solutions containing 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (Table 1). A ratio of ≤1 is expected in the absence of chain reactions, with all Trp oxidation occurring as a direct consequence of reaction with AAPH-derived radicals, whereas a ratio of >1 is expected if chain reactions occur. With 10 mM AAPH, the ratio increased from 3.9 ± 0.2 to 5.8 ± 0.4 in absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, respectively (Table 1). These values are in agreement with previous reports indicating that Trp oxidation occurs via short chain reactions [10,12]. Similarly, an increase from 0.9 ± 0.1 to 1.4 ± 0.1 was calculated for Trp (500 μM) oxidation induced by 100 mM AAPH (Table 1, Fig. 3E). Independent of both the Trp and AAPH concentrations, an increased ratio was detected when oxidation was carried out in presence of dextran (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

To investigate whether the effect of dextran on Trp oxidation was dependent on the molecular mass of the dextran, additional kinetic assays were carried out using a higher molecular mass dextran (Mw 150,000) at two different concentrations (30 and 60 mg mL−1). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, incubation of 50 or 500 μM Trp with 100 mM AAPH, gave increased values for both RiTrp and loss of fluorescence from the parent amino acid, after 30 min incubation in the presence of this dextran.

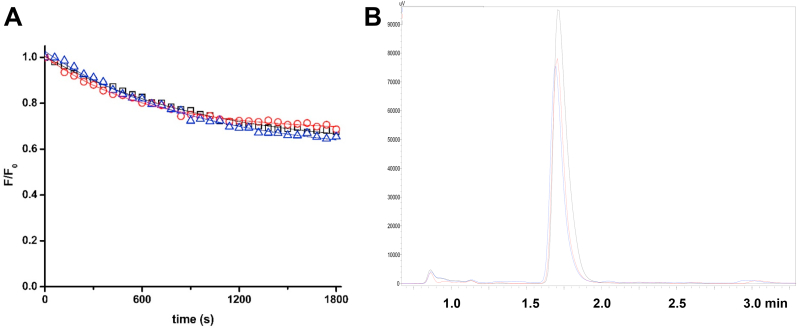

Tyr is also a common target of oxidants, with modifications to this residue affecting cellular homeostasis and signalling pathways [47]. Consequently, the effect of macromolecular crowding on Tyr oxidation by ROO• was also examined. As depicted in Fig. 4A and Table 1, oxidation of 500 μM Tyr by 100 mM AAPH gave similar RiTyr values, and overall loss of parent Tyr, in both the absence and presence of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000), indicating an absence of effects of the crowding agent on oxidation of this residue under these conditions. These findings were corroborated by HPLC-DAD analyses, in which a similar decrease in the Tyr peak area was evident in both the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Tyr oxidation is not affected by the presence of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000). The initial rate (RiTyr) and the total consumption of Tyr (initial concentration 500 μM) on incubation with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C were determined from the decay in the intrinsic fluorescence of the amino acid (λex: 274 nm; λem: 304 nm), and by HPLC with diode array detector (280 nm) in the absence or presence of dextran, respectively. Panel A: kinetic profiles of Tyr (500 μM) consumption on incubation with AAPH (100 mM) in phosphate buffer in the absence (black), or presence of 30 mg mL−1 dextran (red) or 60 mg mL−1 dextran (blue). Panel B: Total consumption of Tyr after 0 (black) and 30 min of incubation in the presence of 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C under 20% O2 in phosphate buffer in the absence (red), and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (blue) as determined by HPLC-diode array detection (280 nm). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

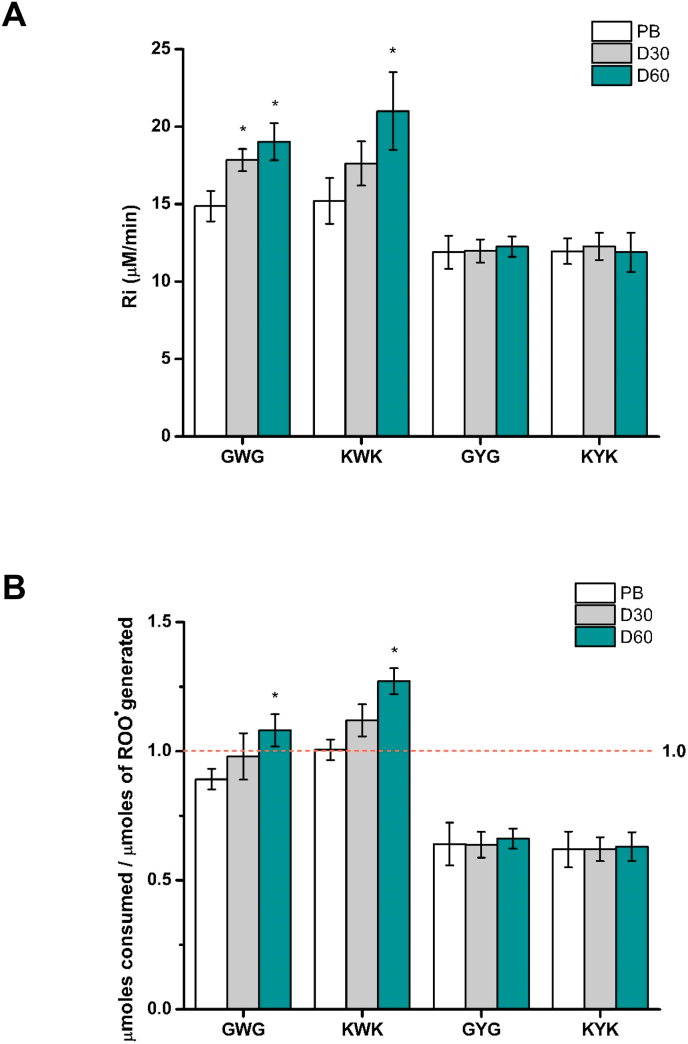

To explore the effect of steric and electronic (charge) interactions with neighbouring residues, oxidation of Trp and Tyr was examined using tripeptides. Fig. 5A show the RiTrp and RiTyr determined for Gly-Trp-Gly, Lys-Trp-Lys, Gly-Tyr-Gly and Lys-Tyr-Lys. As with the free amino acids, a significant increase in Ri was observed for the Trp-, but not the Tyr-, containing peptides when oxidation was carried out in the presence of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) (Fig. 5A and Table 1). Thus RiTrp for Gly-Trp-Gly increased from 14.9 ± 1.0 in phosphate buffer to 17.8 ± 0.7 and 19.0 ± 1.2 in the presence of 30 and 60 mg mL−1 dextran respectively. Likewise, the RiTrp of Lys-Trp-Lys increased from 15.2 ± 1.5 to 17.6 ± 1.4 and 21.0 ± 2.5 in the presence of 30 and 60 mg mL−1 dextran, respectively (Fig. 5A). No further significant differences were detected when the dextran concentration was increased to 120 mg mL−1 (RiTrp of 21.6 ± 2.0) in agreement with the data obtained for free Trp (Fig. 3). Similar behavior was observed for the ratio of peptide consumed per ROO• generated (after 30 min incubation), with this increasing, for Lys-Trp-Lys, from 1.0 ± 0.1 in phosphate buffer to 1.3 ± 0.1 in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, consistent with the presence of short chain reactions (Table 1, Fig. 5B). In contrast, Tyr-containing peptides yielded ratios of <1 in both the absence and presence of dextran suggesting an absence of chain reactions.

Fig. 5.

Effect of macromolecular crowding on the initial rate and total consumption of peptides containing Trp and Tyr residues. Panel A: RiTrp obtained for the peptides Gly-Trp-Gly (GWG), Lys-Trp-Lys (KWK) (500 μM), and RiTyr obtained for the peptides Gly-Tyr-Gly (GYG), Lys-Tyr-Lys (KYK) (500 μM) upon incubation in presence of 100 mM AAPH in the absence, and presence of 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran. Panel B: ratio of the total consumption (μmoles) of GWG, KWK, GYG, KYK per total dose (μmoles) of ROO• generated on 100 mM AAPH thermolysis at 37 °C (30 min) under 20% O2. Control (white), 30 mg mL−1 dextran (light grey bars), 60 mg mL−1 dextran (grey bars) and 120 mg mL−1 (dark cyan bars). Data are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicates data significantly (p < 0.05) different to the samples incubated in absence of dextran. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The effect of dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) on Trp oxidation mediated by AAPH-derived ROO•, was further examined using O2 consumption measurements. Experiments performed in absence of Trp (100 mM AAPH alone) in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.0) at 37 °C showed rates of O2 consumption, from reaction of AAPH-derived alkyl radicals with O2 to give ROO•, in agreement with previous reports (i.e. rates of ROO• formation of ∼ 8 μM min−1) [40]. Experiments with 100 mM AAPH in presence of increasing dextran concentrations, showed enhanced O2 consumption when compared to the absence of dextran (Supplementary Fig. 2). This is ascribed to the oxidation of dextran in absence of other targets for the AAPH-derived radicals, as a consequence of alkoxyl radical (RO•) formation (via termination reactions of ROO•), with these being more powerful oxidants than ROO•. The formation of these species has been reported previously in the absence of targets for ROO• [32]. The formation of RO• is not expected when ROO• are efficiently trapped by high Trp concentrations [9]. Supplementary Fig. 3 depicts O2 consumption data obtained with 16.34 mM Trp (i.e. a ∼ 5 fold higher concentration than 120 mg mL−1 dextran) incubated with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C in the absence and presence of dextran. In both the absence and presence of dextran, O2 consumption was enhanced by the presence of Trp. Moreover, in agreement with the data presented in Fig. 3, Fig. 5, and Table 1, these experiments showed enhanced O2 consumption rates when Trp was oxidized in the presence of dextran, when compared to its absence.

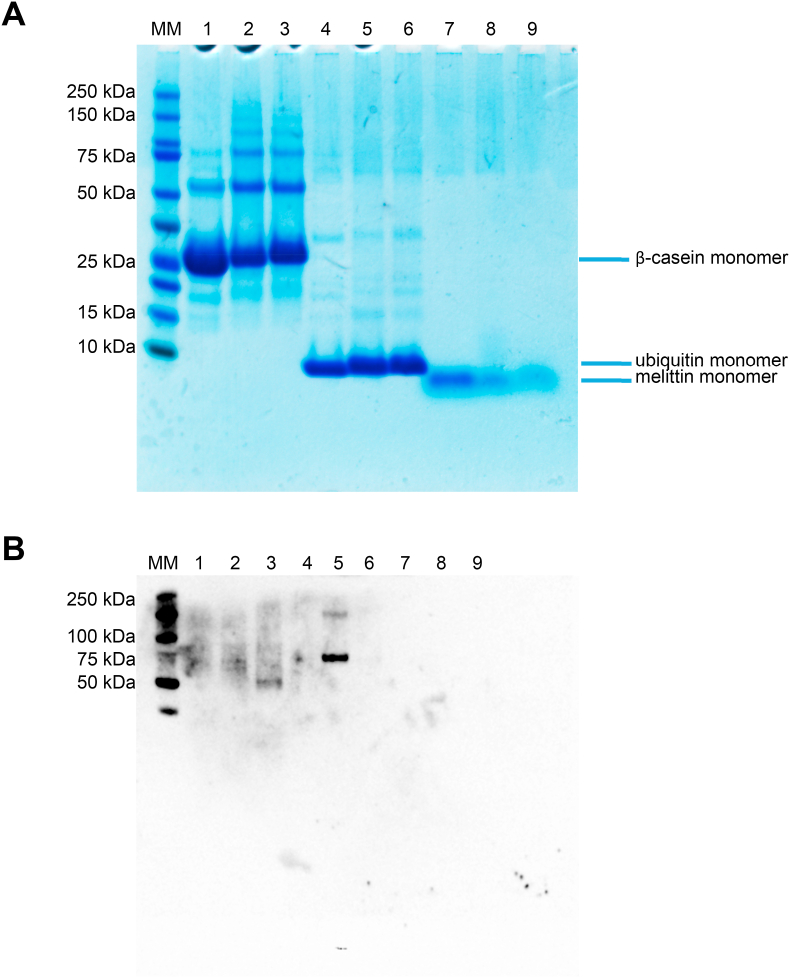

3.4. Effect of macromolecular crowding on the oxidation of Trp- and Tyr-containing proteins

Three proteins were selected to investigate the effect of macromolecular crowding on Trp and Tyr oxidation. Melittin (molecular mass ∼2.8 kDa) and ubiquitin (∼8.6 kDa) were chosen as these contain only a single Trp and Tyr residue, respectively, and do not contain Met or Cys residues which might complicate data interpretation. β-Casein (∼24.0 kDa) was examined, as a more complex model, with this protein containing one Trp, four Tyr and six Met residues, but no Cys or cystine [48]. Fig. 6A depicts a representative SDS-PAGE gel, with lanes 1–3 corresponding to β-casein control, β-casein oxidized in phosphate buffer, and β-casein oxidized in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000), by 100 mM AAPH for 90 min at 37 °C. Lanes 4–6 and 7–9 correspond to analogous experiments with ubiquitin and melittin, respectively. In each case, the controls showed a major band from the monomer as expected (Fig. 6A). Oxidation of melittin (500 μM) resulted in marked monomer consumption, but no evidence for protein cross-linking and/or fragmentation (lane 8, Fig. 6A). The presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) did not perturb these effects (lane 9, Fig. 6A). In contrast, the ubiquitin monomer did not appear to be markedly consumed on incubation with AAPH in the absence (lane 5) or presence (lane 6) of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, but under both oxidation conditions the monomer protein band ran at a slightly higher apparent molecular mass than the parent consistent with protein modification (Fig. 6A). Oxidation of β-casein by ROO• resulted in monomer consumption and formation of protein dimers higher oligomers as reported previously [11]. In the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000) the extent of β-casein oligomer formation was decreased, and monomer band ran at a higher apparent molecular mass (lane 3) when compared to the no-dextran system (lane 2) (Fig. 6A). These effects were even more pronounced in experiments carried out with dextran concentrations of 120 mg mL−1 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 6.

Panel A: the presence of dextran modulates the changes in molecular mass of β-casein, ubiquitin and melittin (each 500 μM) induced by AAPH-derived ROO•. β-Casein (lanes 1–3), ubiquitin (lanes 4–6) and melittin (lanes 7–9) were incubated with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C under 20% O2 in phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 7.0) in the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1dextran. SDS–PAGE was run, under non-reducing conditions, on 4–12% Bis-Tris acrylamide gels, with 12 μg of protein loaded per well. Panel B: Detection of di-Tyr formation by immunoblotting. Gels from Panel A were blotted to a PVDF membrane as described in the Materials and methods section and probed with an anti-diTyr primary monoclonal antibody. MM: molecular mass markers, with masses indicated on the left-hand vertical axis. Lanes 1, 4 and 7 correspond to control samples of each protein incubated in absence of AAPH, whilst lanes 2, 5 and 8, and 3, 6 and 9 correspond to samples incubated with AAPH in absence, and presence of dextran, respectively. Each gel image or blot is representative of one of three independent experiments carried out on different days.

The potential formation of diTyr, a well-established cross-link species, on β-casein and ubiquitin under the above oxidation conditions was examined using an anti-diTyr monoclonal antibody. As shown in Fig. 6B, positive bands indicating the presence of diTyr were detected from both the β-casein and ubiquitin samples. For control β-casein (500 μM, lane 1, Fig. 6B) weak diffuse bands were detected between 50 and 100 kDa. On incubation with 100 mM AAPH for 90 min at 37 °C in phosphate buffer these bands did not change significantly (lane 2 vs lane 1, Fig. 6B). However, when the protein was oxidized in presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, a stronger signal at a molecular mass consistent with a β-casein dimer (50 kDa) was evident (lane 3, Fig. 6B). With ubiquitin, no evidence for diTyr was detected in control samples (lane 4), but oxidation with AAPH, in absence of dextran, gave rise to two distinct bands at ∼75 and ∼150 kDa (lane 5) consistent with the presence of oligomers. These bands were not detected in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (lane 6, Fig. 6B). Together, these data suggest that the presence of dextran modulates the generation of cross-links and oligomers in a protein-specific manner.

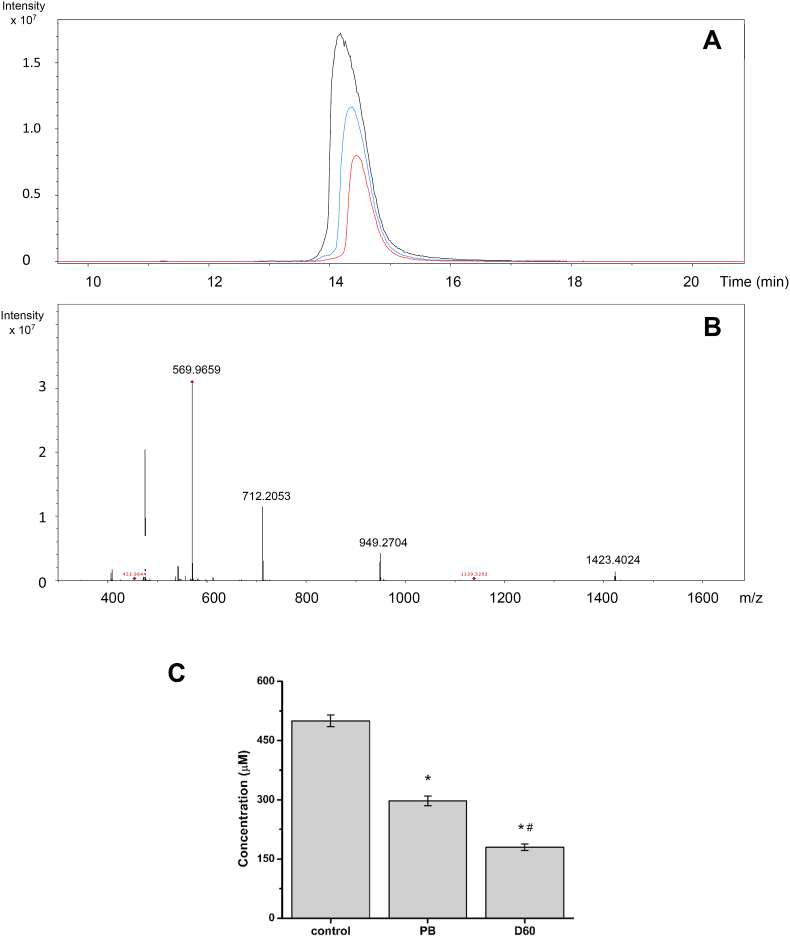

3.5. Analysis of the effect of macromolecular crowding on melittin oxidation by LC-MS

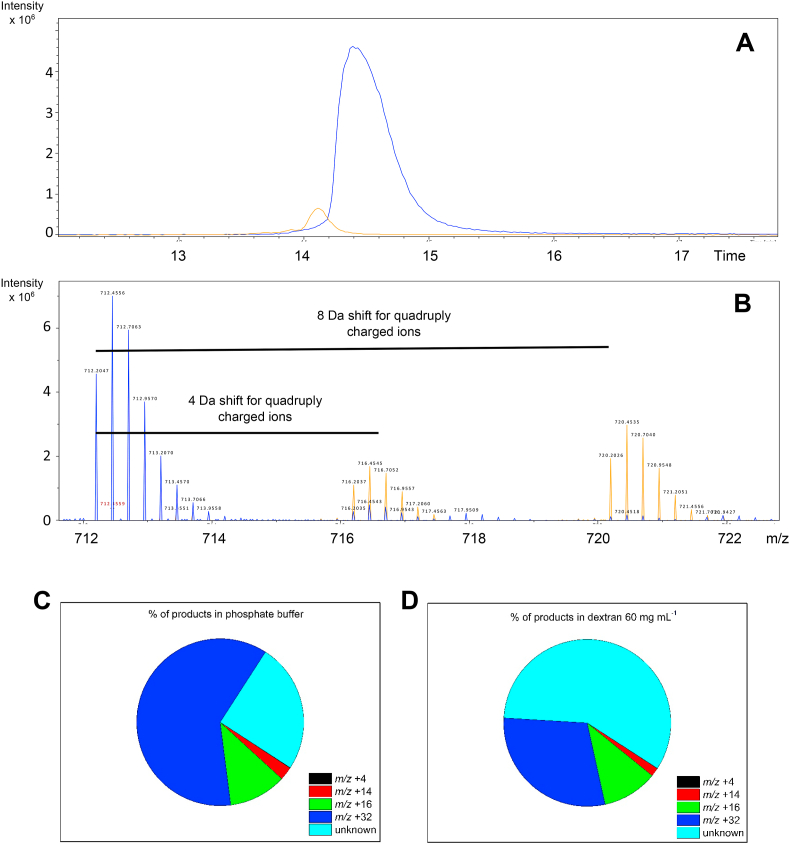

Melittin oxidation was studied by LC-MS. Analysis of control samples showed a single LC peak with a retention time of 14.6 min (Fig. 7A), with this yielding predominant ions with m/z 1423.4024, 949.2704, 712.2053 and 569.9659 corresponding to parent melittin with 2, 3, 4 and 5 positive charges (Fig. 7B). These values are consistent with the expected values (e.g. m/z 1423.3849 for +2 state, error 12.28 ppm). Oxidation of melittin (500 μM) with 100 mM AAPH in phosphate buffer (90 min, 37 °C) resulted in a significant loss on the parent ion signals (Fig. 7A), with a consumption of 203.6 ± 12.2 μmoles determined under these conditions, and ∼40% loss of the parent protein (Fig. 7C). As ROO• are generated at a rate of 8.0 μmol min−1 under these conditions, a total flux of 1.44 μmoles of ROO• are formed in the 2 mL reaction volume after 90 min, resulting in ∼0.28 μmoles of melittin being consumed per μmole of ROO• formed. In agreement with the kinetic data presented in Fig. 3, Fig. 5, melittin consumption was enhanced when oxidation was carried out in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 7A), with 320.1 ± 8.1 μM (64.0% of parent) consumed, as determined by LC-MS (Fig. 7C). These data indicate that 0.44 μmoles of melittin are consumed per μmole ROO• formed under these conditions. Despite this dextran-induced increase in the extent of oxidation, the ratio of μmoles melittin modified per μmole ROO• generated, were below 1 in both the absence and presence of dextran.

Fig. 7.

Consumption of melittin (500 μM) is enhanced in the presence of dextran. Melittin consumption was determined by LC-MS by following the loss of the parent protein molecular ion. Panel A: Extracted ion chromatogram of samples containing melittin (rt: 14.6 min) incubated in the absence (black) and presence of 100 mM AAPH for 90 min in phosphate buffer in the absence (blue), or presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (red). Panel B: MS spectrum recorded at 14.6 min showing the peaks corresponding to doubly (2+; 1423.4024), triply (3+; 949.2704), quadruply (4+; 712.2053) and quintuply (5+; 569.9659) charged melittin ions. Panel C: Total consumption of melittin, determined at the MS1 level, in phosphate buffer in the absence (PB) and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (D60). Data are expressed as means ± SD from three independent experiments with asterisks indicating statistical differences when compared to the control samples, and # indicating statistical differences with the sample oxidized in phosphate buffer. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In agreement with the SDS-PAGE analyses, no evidence for melittin dimers or trimers was obtained by LC-MS in either the presence or absence of dextran (data not shown). However extensive formation of Trp oxidation products was detected, with ions corresponding to kynurenine (+4 Da), carbonyl species (+14 Da, oxindole), hydroxylated (+16 Da) and dioxygenated species (+32 Da, N-formylkynurenine, hydroperoxides or diols). The +16 and +32 Da species predominated, with these having modest changes in retention time when compared to the parent protein (Fig. 8A). Experimental masses of 716.2046 and 720.2031 (both for quadruply-charged species) were detected for these products with an error compared to the theoretical value of 13.26 and 12.91 ppm for the +16 and +32 species, respectively (Fig. 8B). Fig. 8C depicts the quantification of the oxidation products detected from 500 μM melittin at the MS1 level, with the dioxygenated species being the predominant product in phosphate buffer, followed by the mono-oxygenated (∼61 and ∼11% of the total products generated, relative to parent Trp, respectively; Fig. 8C). The extent of formation of the +32 Da species was significantly decreased when oxidation was carried out in presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 8D), with the presence of the crowding agent resulting in an ∼50% decrease in level of this product (∼61–∼29%; Fig. 8D). The extent of formation of the +16 species (∼11%) was not however significantly affected (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

LC-MS analysis of Trp oxidation products generated on melittin by incubation with 100 mM AAPH in phosphate buffer in the absence, and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, at 37 °C for 90 min at 37 °C under 20% O2. Panel A: Representative chromatogram depicting the addition of two oxygen atoms to melittin (m/z +31.98 Da) upon incubation with 100 mM AAPH at 37 °C under 20% O2. Panel B: MS spectrum showing the peaks corresponding to quadruply (4+; m/z 712.2047) charged melittin ions with addition of one (m/z 716.2037) and two (m/z 720.2026) oxygen atoms. Panel C and D: percentage (%) of products with m/z +4, +14, +16 and +32 Da compared to the parent protein, generated on oxidation of melittin in the absence (panel C) and presence (panel D) of dextran. To facilitate data interpretation only mean values are presented in panels B and C.

3.6. Analysis of parent amino acid loss and oxidation products generated on oxidation of model proteins in dilute and crowded environments

LC-MS mass mapping of tryptic peptides generated from ubiquitin and β-casein gave a sequence coverage of 94.3 and 98.1% for the native proteins, respectively. The corresponding values for the proteins (500 μM) modified with 100 mM AAPH, in phosphate buffer, after 90 min at 37 °C, were 94.3 and 90.0% respectively, with the corresponding values in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran being 94.3 and 90.0%, respectively. No significant modifications were detected in the control protein samples.

Mapping of the modifications detected after incubation with AAPH, showed that these were located on the single Tyr residue in ubiquitin (Y59), and at five Met residues (M93, M109, M144, M156 and M185), one Tyr residue (Y180) and the single Trp (W143) for β-casein (Table 2). These data for β-casein are similar to those obtained when this protein was incubated with 10 mM AAPH at high protein concentrations (27 mg mL−1) in the absence of dextran [14]. Whilst these experiments provide valuable data on the sites of modification, absolute quantification of the extents of modification are confounded by the <100% sequence coverage, and an incomplete knowledge of all Trp oxidation products (cf. data in Fig. 8C and D).

Table 2.

Modified peptides identified by LC-MS after tryptic digestion of oxidized ubiquitin and β-casein samples (500 μM). The mass to charge ratio (m/z) of modified peptides, with charge state in parenthesis, and the mass error (ppm) are indicated. The last three columns specify the experimental conditions where the modified peptides were identified, and the number of replicates showing the modified peptides (indicated with a + symbol). Ctrl: control; PB: phosphate buffer; D60: 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Mw 35,000–45,000).

| m/z modified peptide | Mass error (ppm) | Sequence and site of modification | Ctrl | PB | D60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | |||||

| 549.2773 (+2) | 0.2116 | 55TLSDY(+16)NIQK63 | + | +++ | +++ |

| β-casein | |||||

| 1333.9675 (+4) | −0.1177 | 49IHPFAQTQSLVYPFPGPIPNSLPQNIPPLTQTPVVVPPFLQPEVM(+16)GVSK97 | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| 343.8443 (+3) | −0.7956 | 106HKEM(+16)PFPK113 | +++ | +++ | |

| 1279.0549 (+5) | −0.1468 | 114YPVEPFTESQSLTLTDVENLHLPLPLLQSW(+16)MHQPHQPLPPTVM(+16)FPPQSVLSLSQSK169 | + | +++ | +++ |

| 1282.2539 (+5) | −0.1672 | 114YPVEPFTESQSLTLTDVENLHLPLPLLQSW(+32)M(+16)HQPHQPLPPTVMFPPQSVLSLSQSK169 | +++ | +++ | |

| 423.7271 (+2) | −1.2702 | 177AVPY(+16)PQR183 | +++ | +++ | |

| 734.7257 (+3) | −0.2506 | 184DM(+16)PIQAFLLYQEPVLGPVR202 | + | +++ | +++ |

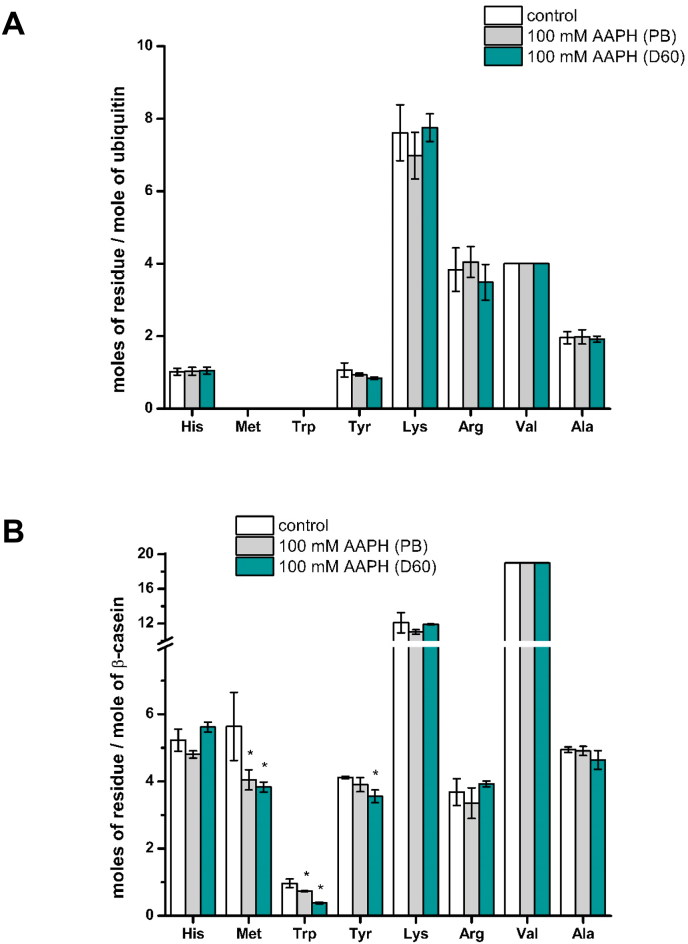

To overcome the above problems, quantitative data on the extent of amino acid loss induced by AAPH-induced oxidation was obtained after acid hydrolysis (to release free amino acids and products), and subsequent LC-MS quantification against isotope-labelled standards as described previously [37]. Of the 17 common amino acids quantified using this method, only Tyr showed a significant decrease in ubiquitin after incubation with AAPH (Fig. 9A). 1.07 ± 0.19 mol of Tyr were detected per mole of protein in controls, as expected from the protein sequence data (Uniprot ID P0CG48). Incubation with 100 mM AAPH for 90 min in the absence or presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran resulted in a decrease to 0.93 ± 0.04 and 0.84 ± 0.03 mol of Tyr per mole ubiquitin, respectively (Fig. 9A). These values correspond to a consumption of 0.14 and 0.23 mol of Tyr per mole of ubiquitin in the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, respectively, and a ratio of moles of Tyr consumed per mole of ROO• generated of 0.10 and 0.16, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Moles of amino acid residues per mole of casein quantified by LC-MS before and after incubation of ubiquitin (panel A) or β-casein (panel B) with 100 mM AAPH for 90 min at 37 °C under 20% O2 in phosphate buffer in the absence (PB) and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (D60). White bars correspond to control samples whilst light grey and dark cyan correspond to samples incubated with AAPH in the absence (PB) or presence (D60) of dextran. To minimize variations arising from protein hydrolysis, the data are normalized to the numbers of moles of Val quantified in each sample (as this residue is not target by ROO•) and then expressed as moles of residue per mole of protein. Data represent the means ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments. Asterisks indicates data significantly (p < 0.05) different to the control samples. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

In contrast, β-casein showed high levels of oxidation on Trp, Tyr and Met residues in both the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 9B). For controls 0.96 ± 0.13, 4.12 ± 0.04 and 5.63 ± 1.01 mol of Trp, Tyr and Met per mole of casein were detected, with 1.0, 4.0 and 6.0 mol of Trp, Tyr and Met per mole of casein expected (Uniprot ID P02666). These values decreased to 0.73 ± 0.02, 3.90 ± 0.21 and 4.04 ± 0.30 (Trp, Tyr and Met, respectively) on incubation with 100 mM AAPH in phosphate buffer, and 0.38 ± 0.03, 3.55 ± 0.19 and 3.83 ± 0.15 on incubation with 100 mM AAPH in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 9B). These values indicate that a total of 2.04 mol of amino acid (Met, Trp and Tyr), were consumed by AAPH-derived radicals, per mole of casein in the absence of dextran. Oxidation in the presence of the crowding agent resulted in 2.95 mol of amino acid consumed per mole of casein, which corresponds to an increase of ∼45% over the values obtained in phosphate buffer. Likewise, the ratios of the number of moles of amino acid consumed, per mole of ROO• generated during thermolysis of 100 mM AAPH, were 1.42 and 2.05 for samples oxidized in absence and presence of the crowding agent, respectively. As these values are >1 they indicate the occurrence of chain reactions [11] during these oxidations.

Quantification of kynurenine (from Trp) and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine and 3,3′-dityrosine (from Tyr) was also attempted for control and treated samples of ubiquitin and β-casein, but the extent of formation of these products was below the limit of detection for the method, indicating that other unknown products are formed.

4. Discussion

Macromolecular crowding is an inherent property of most biological environments. For example, in blood plasma the total protein concentration is close to 80 mg mL−1, and the cytosol of most cells macromolecule concentrations can reach 400 mg mL−1 [16,49]. Crowding also occurs in other biological materials such as foods (e.g. the protein concentration in milk is ∼35 mg mL−1) and some pharmaceutical products (e.g. concentrations of antibodies in injectable formulations are often 50–200 mg mL−1 [50]). Previous studies have demonstrated that the close packing arising from these concentrated conditions plays a significant role in determining biochemical interactions and properties including effects on diffusion, protein-protein interactions, folding, enzyme kinetics, and aggregation [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22],51]. In the light of these data, we hypothesized that such crowding may affect the rate and extent of protein oxidation, as well as the mechanisms (and hence products) arising from these reactions. This hypothesis is supported by recent findings from Perusko et al. [52], Aicardo et al. [13], and work from our laboratory [14]. In particular, Aicardo et al., have shown that macromolecular crowding induced by high protein concentrations or non-peptide polymers (e.g. PEG) can enhance protein oxidation. These important observations are developed in the studies reported here, because of their enormous potential consequences in rationalizing the pathways leading to accumulation of damaged proteins in multiple diseases.

In the present work, the effect of macromolecular crowding on the rate and extent of Trp and Tyr oxidation was examined, as both residues are major oxidant target in cells and biological fluids [6,8,47]. Furthermore, it is known that oxidation of these residues can generate intermediates that contribute to damage propagation, and result in altered redox-signalling [6,7]. AAPH thermolysis was employed to generate defined radical species (ROO•) at a known and constant rate to allow accurate quantification of the extent of oxidant formation, and hence the yields of products per oxidant introduced. Dextran was chosen as the crowding agent, as this polymer was not expected to compete with the indole (of Trp) or phenol group (of Tyr) for the ROO• generated. Moreover, dextran is known to generate an exclusion volume phenomenon as result of steric repulsion [53]. Thus, dextran excludes other molecules present in the solution from the space occupied by this macromolecule, resulting in a lower available volume and increased crowding of the species undergoing reaction.

In initial experiments, the capacity of dextran to generate microdomains (Fig. 1) was examined, and the data obtained indicate that these are generated with dextran concentrations of > ∼5 mg mL−1. The capacity of dextran to modulate the efficiency of radical formation from AAPH and subsequent escape from the solvent cage (Eq. (1)) was also explored, as this might result in altered rates of formation and doses of ROO• when compared to phosphate buffer [40]. Previous studies have reported such effects with another azocompound (AIBN) where the efficiency is altered with increasing solvent viscosity [41]. To investigate this with AAPH, Trolox consumption was quantified in the absence and presence of 30, 60 and 120 mg mL−1 dextran (35,000–45,000), as the mechanism and stoichiometry of this reaction in aqueous media is well established [42,54]. A similar extent of consumption (184 ± 15 μM) was determined for each condition (phosphate buffer without and with 30, 60 or 120 mg mL−1 dextran; Fig. 2), indicating that the rate and total doses of ROO• formed under the conditions employed, are not affected by the crowding agent.

In agreement with previous studies, the time course of decay of Trp fluorescence induced by ROO• followed a pseudo-first order (exponential) decay profile at low Trp concentrations (50 μM) (Fig. 3A) [9]. However, a significantly higher loss of Trp fluorescence was detected for solutions containing 500 μM Trp and 100 mM AAPH after 30 min in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran compared to its absence (68% vs 47%; Fig. 3A). From these kinetic profiles, the initial rate of RiTrp was determined, with higher Trp concentrations leading to higher rates of oxidation. Thus the RiTrp values determined for 50 μM and 500 μM Trp, respectively (Fig. 3B, Table 1) were approximately doubled in the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran. Similarly, the total loss of Trp (from 500 μM Trp), on incubation with 10 and 100 mM AAPH for 30 min, was enhanced from 93.5 ± 4.0 to 139.5 ± 8.5 μM, and from 217.2 ± 27.0 to 336.5 ± 22.0 μM, in phosphate buffer compared to crowded media, respectively (Table 1). Of particular note, is the observation that the concentration of ROO• formed from 10 mM AAPH over 30 min is lower than the amount of Trp consumed, giving a ratio of 3.9 ± 0.2 mol of Trp consumed per mole of ROO• generated, and a ratio of 5.8 ± 0.4 for phosphate buffer vs the 60 mg mL−1 dextran (crowded) condition (Table 1). These results indicate the occurrence of short chain reactions during Trp oxidation under the 20% O2 atmospheres employed [9,10]. Furthermore, these data indicate that these chain reactions are exacerbated by the presence of dextran. The data are consistent with the following minimum set of reactions for Trp oxidation by ROO•, with equations (1), (2), (3) corresponding to the initiation phase of the oxidation process, and equation (4) representing the propagation phase [8].

| AAPH → 2R• + O2 → 2ROO• | (1) |

| Trp(H) + ROO• → Trp• + ROOH | (2) |

| Trp• + O2 → TrpOO• | (3) |

| TrpOO• (or Trp•) + Trp(H) → Trpox + Trp• | (4) |

| Trp• + Trp• → diTrp | (5) |

The major chain carrying species is likely to be TrpOO•, rather than Trp•, as reaction of the latter with another Trp(H) would simply alter the site of damage, rather than result in additional damage. Equation (5) indicates one of the possible termination reactions for the system with ROO•, Trp•, and TrpOO• present, but it is likely that multiple radical-radical termination reactions occur. Therefore, the length of the chain reactions will depend both on the concentration of the oxidizable target (Trp), as well as the probability of reaction between two radicals to yield stable non-radical products. This is supported by the data obtained with higher Trp concentrations (and a constant AAPH concentration) which resulted in higher RiTrp values (Fig. 3C). Increasing the AAPH concentration, from 10 to 100 mM, resulted in shorter chains, as expected from the higher radical fluxes (ROO•/TrpOO•) which enhance the probability of termination (Table 1). These differences were observed for both phosphate buffer and the dextran conditions (Fig. 3B and C). Of particular note, is the observation that RiTrp was consistently higher for oxidations carried out in presence of dextran (Fig. 3B). As the AAPH concentration - and hence ROO• dose - was kept constant, this suggests that the increase in the chain length is a consequence of a decrease in the extent of radical termination, rather than an increase in the extent of formation of Trp• and TrpOO•. This decrease in termination is likely to arise from steric impediments to radical diffusion, and therefore radical-radical interactions. Whilst the rate constants for radical-radical reactions are typically very high (due to low energy barriers), and greater than those involved in damage propagation, dimerization reactions are less probable at low steady-state radical concentrations [55]. Propagation may also be increased by crowding agents, due to an enhancement of collisional encounters within the microdomains present in crowded solutions. These findings are in agreement with previous data where it was shown that Cys and Trp residues can contribute to the propagation of damage within proteins via short radical chain reactions [13,14], especially under situations where proteins are forced into closer proximity as seen during bovine serum albumin oxidation [13].

In contrast to the dextran-induced changes in RiTrp (Fig. 3, Table 1), RiTyr was unperturbed by this crowding agent (Fig. 4, Table 1). This is ascribed to differences in the chemistry of Trp• or Tyr• radicals. Thus whilst indolyl radicals (Trp•) react with O2, to generate TrpOO•, with moderate rate constants (k ∼105 M−1 s−1 [56]), k for the addition of O2 to Tyr phenoxyl radicals is at least 100 times slower (k < 103 M−1 s−1 [47]). This lower rate constant, together with the high rate constant for Tyr• dimerization to give diTyr (k ∼3 × 108 M−1 s−1, with this being structure and situation dependent [47]), is likely to result in a lower extent of chain propagation, and a greater extent of radical termination, with these being (at best) weakly dependent on the presence of crowding agents.

To explore whether these conclusions hold for more complex systems, studies were carried out with peptides and a limited number of proteins. As depicted in Fig. 5A, the RiTrp determined for Gly-Trp-Gly, Lys-Trp-Lys, Gly-Tyr-Gly and Lys-Tyr-Lys showed similar trends to those observed for free Trp and Tyr in phosphate buffer and dextran-containing media. Thus, whilst RiTrp increased in a manner dependent on the dextran concentration, RiTyr was unaffected. Similarly, the ratio of μmoles of peptide consumed per μmole ROO• generated was ≥1 (indicating chain reactions) only for the Trp-containing peptides (Fig. 5B, Table 1).

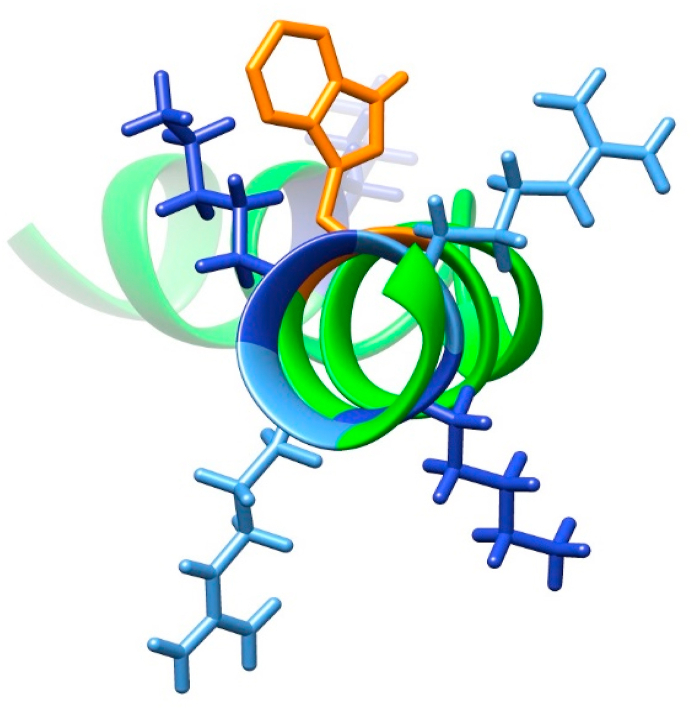

Consumption of the β-casein monomer and formation of cross-links (in line with previous studies [11]) was observed by SDS-PAGE after incubation with AAPH, in both the absence and presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran (Fig. 6A). A greater staining intensity of the bands assigned to trimers and high mass aggregates was detected in phosphate buffer alone, compared to the presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran. This effect was more pronounced at higher dextran concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 4), supporting the conclusion that the presence of dextran can modulate reactions leading to protein cross-linking. In contrast, oxidation of ubiquitin and melittin did not result in the formation of cross-linked species. However, a decrease in the intensity of the melittin monomer band was observed in both the absence and presence of dextran, with the latter condition resulting in a greater loss of the parent (Fig. 6). These results are corroborated by the LC-MS analyses, where the extent of monomer consumption was determined as 203.6 ± 12.2 and 320.1 ± 8.1 μM in phosphate buffer and dextran-containing solutions, respectively, on incubation with 100 mM AAPH for 90 min (Fig. 7). The higher consumption observed in the presence of dextran is consistent with the data in Table 1, and Fig. 3, Fig. 5, but unlike the experiments with free amino acids or peptides, the ratio of the number moles of melittin lost per mole of ROO• formed was <1. This is not surprising because melittin has four positively charged residues in its carboxyl-terminal region in close proximity to the single Trp residue, with two of these located on the same helical face (Fig. 10). These may give rise to unfavourable electronic interactions with other melittin molecules and hence diminish propagation reactions. This is similar to the “spatial” shielding reported for dendrons (bulky monodisperse wedge-shaped polymers with multiple terminal groups and a single reactive moiety), where a decreased rate and yield of radical-induced modification of the aromatic group was observed [57].

Fig. 10.

Rendering of the locations of Trp (orange), Lys (blue) and Arg (light blue) residues in melittin (structure from Protein Database ID: 2MW6). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Further information on the mechanism of oxidation of melittin under phosphate buffer vs crowded conditions was obtained from LC-MS analyses of the reaction products. The major product detected (∼61%, Fig. 8C) in phosphate buffer was identified as a Trp-derived species with two added oxygen atoms. This +32 Da mass addition is likely to correspond to either a hydroperoxide (e.g. the Trpox species in equation (4), arising from reaction of TrpOO• with a hydrogen atom donor) or N-formylkynurenine (a well-established downstream product of Trp hydroperoxides) [58,59]. Di-alcohol structures cannot be excluded, but these are more commonly observed as secondary products (e.g. of photochemical processes, or Trp hydroperoxide decomposition) [[59], [60], [61]]. Importantly, when oxidation was carried out in presence of 60 mg mL−1 dextran, this +32 Da product was less prevalent (∼29% of the modified melittin). These results imply that ∼124 μM and ∼94 μM of this product are formed in the absence and presence of dextran, respectively. The nature of the other product(s) generated under crowding conditions remain to be determined, and these appear to be different to those searched for in the current study. The lower abundance of the established Trp-derived species under crowded conditions suggests that alternative species are being formed – possibly as a result of alternative oxidative pathways.

Consistent with the data obtained for free Tyr oxidation in diluted and crowded milieus, the presence of dextran did not alter the extent of oxidation of the single Tyr in ubiquitin (Fig. 9A). In contrast, when β-casein (500 μM) – a flexible and intrinsically-unstructured protein containing four Tyr, one Trp and six Met residues – was exposed to AAPH-derived ROO• an increased loss of parent amino acids was observed under crowding conditions (Fig. 9B). Thus, 2.04 mol of amino acid were consumed per mole of protein in phosphate buffer, with this increasing to 2.95 mol in the presence of dextran, for the 100 mM AAPH-mediated oxidation condition. Met was the most modified residue under these conditions, followed by Trp and Tyr (Fig. 9B), with enhanced consumption of each of these detected in the presence of dextran. These data are in agreement with previous reports that have highlighted the role of Met in casein oxidation [11]. The ratio of moles of amino acid consumed per mole of ROO• generated, of 1.42 and 2.05, determined for the phosphate-buffer and dextran conditions, respectively, indicate the occurrence of short chain reactions. Overall, these data demonstrate that macromolecular crowding induced by dextran modulates the rate and extent of Trp oxidation induced by ROO•, consistent with excluded volume phenomena playing a role in oxidative processes involving this residue. These effects appear to depend on the protein and oxidants examined, as contrarily to previous published data where inclusion of a crowding agent (PEG) was not enough to change the response of BSA oxidation induced by ONOO−, our findings do show an effect [13].

5. Conclusions

The data reported here indicate that in vitro experiments need to be carefully designed if the aim is to understand oxidative pathways of relevance for cell function, signalling and pathology. The results presented establish that, in addition to earlier data on differential effects of crowding on trafficking and diffusion of molecules, that oxidation mechanisms and rates are also affected by crowding agents. Molecular crowding should therefore be a major consideration in experimental design. Such crowding has been shown to modulate: 1) the rates of oxidation, 2) the total extent of modification, and 3) the nature of the products formed. This appears to be of particular importance for Trp residues, but enhanced Tyr and Met oxidation was also observed. This is postulated to be due to modulation of the rates of termination reactions (involving the chain-carrying species TrpOO•) rather than an increase in the rate constants for secondary oxidation processes. The lesser effects of dextran on Tyr oxidation may indicate a lesser role for radicals formed from this residue as chain carrying species, though the results obtained with β-casein demonstrate enhanced oxidation of Tyr and Met under crowded conditions. Whether this is a direct consequence of the presence of the single Trp residue in β-casein remains to be established. These findings reveal the significance of volume effects on oxidative processes and the importance of developing approaches to minimize Trp oxidation in crowded environments. Such effects may also occur with other residues, such as Cys, and this warrants further study due to the critical role of this residue in cell signalling.

These crowding effects are likely to have their greatest influence with oxidants of modest reactivity – the species most likely to act as cell signalling molecules - due to their capacity to diffuse significant distances. This is because relatively slow reactions are limited by the rates of encounter between two reactants, and by the formation of association/transition states, with the latter being the predominant energy barrier for reaction. In contrast, for highly reactive species (e.g. hydroxyl radical, HO•, reactions, and some radical-radical reactions), reaction occurs immediately on encounter with a target. Such events are largely dominated by translational diffusion, and since macromolecular crowding decreases this (as a result of an increase in the number of ‘obstacles’), crowding might be expected to reduce these. However, micro-domains with high local concentrations of reactants, due to the crowded environment, may act as micro-reactors and enhance the extent of reaction. The role of these two contradictory effects has yet to be fully elucidated.

The data presented here indicate that are inherent complications in monitoring the kinetics of protein oxidation and modification (and also of other biological molecules) in intact biological systems, including within cells. The experimental methods presented here provide a new approach to exploring oxidation kinetics and mechanisms using a high concentration of soluble macromolecules that resemble the network of extended and crowded structures present in biological systems, and the microdomains generated in different cell compartments. This approach should provide a greater understanding of the effects of crowded environments, and microdomains, on oxidation processes, with this information shedding light on multiple problems in the redox biology and signalling fields. An example of this, is the uncertainty as to how signalling by oxidants occurs in the presence of high levels of oxidant removal systems, such as glutathione (GSH) and peroxide-removing enzymes (e.g. peroxiredoxins, glutathione peroxidases and catalase). A possible explanation is that signalling occurs within microdomains, and with different kinetics to those reported for bulk dilute solutions. Therefore, the study of oxidative processes under conditions that exhibit excluded volume phenomenon and microdomains, has the potential to throw light on redox signalling paradigms in health and disease.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 890681 (to EFL) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Laureate grants: NNF13OC0004294 and NNF20SA0064214 to MJD). LFG acknowledges the Lundbeck Foundation for financial support (fellowship 117939). CLA acknowledges funding from Fondecyt grant n° 1180642.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.102202.

Contributor Information

Eduardo Fuentes-Lemus, Email: eduardo.lemus@sund.ku.dk.

Michael J. Davies, Email: davies@sund.ku.dk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Butterfield D.A., Halliwell B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;20:148–160. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Świderska M., Maciejczyk M., Zalewska A., Pogorzelska J., Flisiak R., Chabowski A. Oxidative stress biomarkers in the serum and plasma of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Can plasma AGE be a marker of NAFLD? Oxidative stress biomarkers in NAFLD patients. Free Radic. Res. 2019;53:841–850. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2019.1635691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryk A.H., Konieczynska M., Rostoff P., Broniatowska E., Hohendorff J., Malecki M.T., Undas A. Plasma protein oxidation as a determinant of impaired fibrinolysis in type 2 diabetes. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2019;119:213–222. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed U., Anwar A., Savage R.S., Thornalley P.J., Rabbani N. Protein oxidation, nitration and glycation biomarkers for early-stage diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the knee and typing and progression of arthritic disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016;18:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y., Beyer A., Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell. 2016;165:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies M.J. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem. J. 2016;473:805–825. doi: 10.1042/BJ20151227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins C.L., Davies M.J. Generation and propagation of radical reactions on proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2001;1504:196–219. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Alarcón C., Arenas A., Lissi E., Silva E. The role of protein-derived free radicals as intermediaries of oxidative processes. Biomol. Concepts. 2014;5:119–130. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2014-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuentes-Lemus E., Dorta E., Escobar E., Aspée A., Pino E., Abasq M.L., Speisky H., Silva E., Lissi E., Davies M.J., López-Alarcón C. Oxidation of free, peptide and protein tryptophan residues mediated by AAPH-derived free radicals: role of alkoxyl and peroxyl radicals. RSC Adv. 2016;6:57948–57955. doi: 10.1039/c6ra12859a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janković I.A., Josimović L.R. Autoxidation of tryptophan in aqueous solutions. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2001;66:571–580. doi: 10.2298/jsc0109571j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuentes-Lemus E., Silva E., Barrias P., Aspee A., Escobar E., Lorentzen L.G., Carroll L., Leinisch F., Davies M.J., López-Alarcón C. Aggregation of α- and β- caseins induced by peroxyl radicals involves secondary reactions of carbonyl compounds as well as di-tyrosine and di-tryptophan formation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;124:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lissi E.A., Clavero N. Inactivation of lysozyme by alkylperoxyl radicals. Free Radic. Res. 1990;10:177–184. doi: 10.3109/10715769009149886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aicardo A., Mastrogiovanni M., Cassina A., Radi R. Propagation of free-radical reactions in concentrated protein solutions. Free Radic. Res. 2018;52:159–170. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2017.1420905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]