Abstract

Objective

This study aims to better understand the current practice of clinical guideline adaptation and identify challenges raised in this process, given that published adapted clinical guidelines are generally of low quality, poorly reported and not based on published frameworks.

Design

A qualitative study based on semistructured interviews. We conducted a framework analysis for the adaptation process, and thematic analysis for participants’ views and experiences about adaptation process.

Setting

Nine guideline development organisations from seven countries.

Participants

Guideline developers who have adapted clinical guidelines within the last 3 years. We identified potential participants through published adapted clinical guidelines, recommendations from experts, and a review of the Guideline International Network Conference attendees’ list.

Results

We conducted ten interviews and identified nine adaptation methodologies. The reasons for adapting clinical guidelines include developing de novo clinical guidelines, implementing source clinical guidelines, and harmonising and updating existing clinical guidelines. We identified the following core steps of the adaptation process (1) selection of scope and source guideline(s), (2) assessment of source materials (guidelines, recommendations and evidence level), (3) decision-making process and (4) external review and follow-up process. Challenges on the adaptation of clinical guidelines include limitations from source clinical guidelines (poor quality or reporting), limitations from adaptation settings (lacking resources or skills), adaptation process intensity and complexity, and implementation barriers. We also described how participants address the complexities and implementation issues of the adaptation process.

Conclusions

Adaptation processes have been increasingly used to develop clinical guidelines, with the emergence of different purposes. The identification of core steps and assessment levels could help guideline adaptation developers streamline their processes. More methodological research is needed to develop rigorous international standards for adapting clinical guidelines.

Keywords: quality in health care, qualitative research, statistics & research methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To ensure participants’ representativeness, we invited clinical guideline (CG) adaptation experts through different ways, including adapted CGs, attendees from the Guideline International Network conference and additional strategies or sources.

To reduce participant’s bias, we complemented participants’ views and experiences with their adaptation methodology publications.

The interview format allowed us to explore the challenges of CG adaptation in depth and how the participants address specific issues.

The challenges highlighted by our study are likely to be universal to experienced CG adaptation developers, since our participants’ selection process limits the study samples to experts with sufficiently large experience in the CG adaptation or development field.

Some specific challenges, such as particular contextualisation issues, might be under-reported in our study due to the small sample size and fewer participants from low-income/middle-income countries.

Introduction

Clinical guidelines (CGs) adaptation is an efficient methodology to develop contextualised recommendations.1 2 CG adaptation tailors existing trustworthy CGs for local, regional or national guidance, by considering local contextual factors, such as language, availability and accessibility of services and resources, the healthcare setting and the relevant stakeholders’ cultural and ethical values.3 CG adaptation may lead to changes compared with the original recommendations in (1) the specific population, intervention or comparator, (2) the certainty of the evidence or (3) the strength of recommendations by including additional information regarding the health conditions, monitoring, implementation and implications for research.4 Besides, CG adaptation could also be used as an alternative method to develop de novo CGs, with the expectation of reducing waste of resources and avoiding duplication of efforts. However, this process should follow a similar and systematic approach as that of the source CGs to benefit from their quality.3 5 6

Currently, there is no single standard adaptation methodology.7 8 One systematic review identified eight frameworks for CG adaptation1: Resource Toolkit for Guideline Adaptation—ADAPTE instrument,9 Adapted ADAPTE,10 Alberta Ambassador programme adaptation phase,11 Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Evidence to Decision frameworks for adoption, adaptation and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations (GRADE-ADOLOPMENT),4 Making GRADE the irresistible choice,12 RAPADAPTE for rapid guideline development,13 Royal College of Nursing (RCN)14 and Systematic Guideline Review.15 Most of these frameworks are based on the ADAPTE instrument,9 while some use the GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks.1 4 The comparison between frameworks showed similarities in the initial and final phases of the process, and notable differences in the ‘adaptation’ phase of the process.1 Another recent review categorised the frameworks into formal and informal.7 However, new methods and experiences of CG adaptation periodically emerge.16–18

Despite this, published adapted CGs seldom used a published adaptation methodology and their quality is still suboptimal.19 A systematic survey that assessed 72 published adapted CGs found that only 57 reported any details on adaptation methods, and only 23 used a published adaptation methodology. The proportion of published adapted CGs satisfying the steps of ADAPTE ranges from 4% to 100%. In addition, the mean score of adapted CGs assessed using Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II (AGREE II) was 57% for the ‘rigour of development’ domain, and 50% for the ‘applicability’ domain. Similarly, another systematic assessment found that only 30% of adapted WHO CGs reported adaptation process methods.20

Challenges faced by adaptation groups are not well known and are likely to vary across CG organisations. A recent review described several limitations of published adaptation frameworks and showed that the time to adapt CGs using the same framework varies between 18 months and 3 years.7 Besides, most adaptation frameworks require methodology expertise; this might be a barrier for many CG adaptation groups, especially those from low-income/middle-income countries (LMICs). Although international collaboration and providing staff training could help, this should be based on a standardised adaptation process. Furthermore, most published adaptation frameworks were developed from adaptation experiences and lacked validation.7 No formal evaluation instrument or guidance could help expertise methodologists improve adaptation frameworks.7

In addition, fundamental gaps between international recommendations and realistic best practice are being reported due to poorly CG adaptation, which leaves health providers with non-useful guidance.21 There is an urgent need to explore the proper adaptation process and share the global adaptation experience. This study aims to better understand the current practice of CG adaptation and identify the challenges raised in this process, thus providing accordance for the improvement of the adaptation process.

Methods

We applied a qualitative design using semi-structured interviews. This study is part of the RIGHT-Ad@pt project, which aims to develop a reporting checklist for CG adaptation.22 We reported findings using the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research checklist.23

From now on, we will refer to the CGs selected for adaptation as ‘source CGs’, and to the evidence from the source CGs as ‘source evidence’.

Participants

We sampled a group of CG developers, who had been involved in CG adaptation over the past 3 years using a snowball sampling method.24 We identified potential participants from (1) authors lists of 16 published adapted CGs retrieved from a search for adapted CGs via PubMed (from 1992 to December 2019) (online supplemental appendix 01);25 (2) suggestions from the advisory group of the RIGHT-Ad@pt project and (3) attendees of the 2019 Guideline International Network (G-I-N) conference.

bmjopen-2021-053587supp001.pdf (385.7KB, pdf)

We contacted potential participants by email with an invitation letter including (1) an introduction to the RIGHT-Ad@pt project, (2) the eligibility criteria, (3) the purpose of the semistructured interview, (4) the topics to be discussed and (5) the expected contribution from participants. We sent two email reminders within 1 month. After receiving consent for participation and before starting the semi-structured interviews, we circulated a more detailed description of the RIGHT-Ad@pt project, the interview guide, and collected the Conflicts of interest (CoI) form from each participant. We continued to recruit participants and collect data until we reached saturation.

Data collection

We designed an interview guide based on checklists previously developed by our group, and the experience obtained from the development of the RIGHT-Ad@pt checklist.22 26 27 The interview guide included four sections (online supplemental appendix 02): (1) characteristics of participants (country, experience in the field of health-related CGs and CG adaptation), (2) characteristics of participants’ CGs developing organisation, (3) participants’ experiences about current practice in the adaptation process and (4) participants’ views and experiences about challenges in the adaptation process. Participants completed the first two sections before the interview. We also asked participants to provide the published methodology that supported their adaptation processes if applicable. Interviews were conducted face to face or via teleconference and lasted approximately 40 min. We audiorecorded each interview with the participant’s permission. One researcher (YS, PhD(c), female, with guideline development and adaptation experience) conducted the semistructured interviews and transcribed them verbatim.

Data analysis

For quantitative variables (characteristics of participants and organisations), we calculated absolute frequencies and proportions.

For qualitative data regarding adaptation processes, we followed a framework deductive analysis.28 First, we generated a priori thematic framework for the main steps of adaptation processes, based on relevant systematic reviews.1 7 Second, we sought additional concepts from the methodological evidence provided by participants. Third, we coded semistructured interviews findings against the resulting thematic framework, revised and merged codes into themes as new aspects emerged. Finally, we proposed subthemes under the drafted thematic framework. For participants’ views and experiences about challenges, we applied an inductive thematic analysis; we coded the interview transcripts ‘line by line’, proposed descriptive themes following the coding process; and generated analytical themes by analysing, organising and creating descriptive subthemes.29 30 One author (YS) coded and extracted qualitative data, drafted the framework and proposed themes independently. Two authors (MB and JL) double-checked selected codes and the corresponding quotations. A second senior author (PA-C) reviewed the framework and themes. A final structure was confirmed by discussion and approved by consensus. We used NVivo (V.12 for Mac, QSR International) for qualitative analysis.31

Patient and public involvement

The patient and public were not involved in the study.

Results

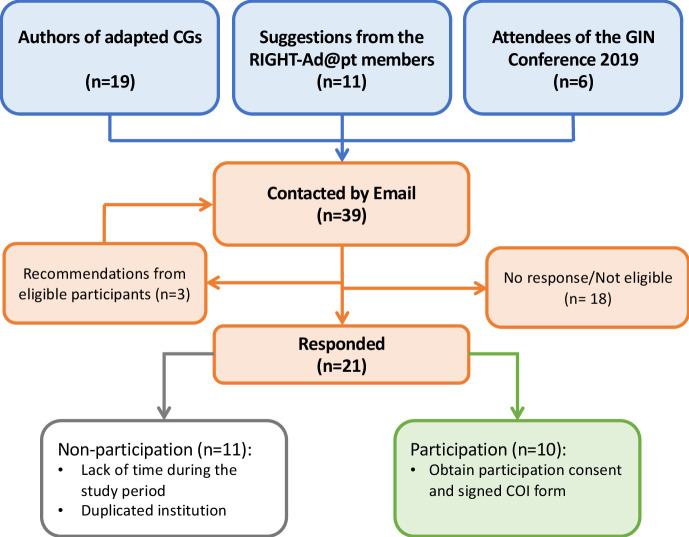

We invited 39 CG adaptation developers to participate. Participants were identified from published adapted CGs (49%; 19/39), suggestions from the Advisory Group of the RIGHT-Ad@pt project (28%; 11/39), attendees of G-I-N conference (2019) (15%; 6/39) and eligible participants’ recommendations (7%; 3/39) (See figure 1). Finally, we conducted ten semistructured interviews between November 2019 and January 2020 until data saturation on the reason for CG adaptation and methodology was reached. Data from published methodologies of different participating organisations were included in framework analysis to avoid individual bias. In addition, data from individuals were included in the thematic analysis to reflect participants’ views and experiences.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment flow diagram. Relevant conference attendees were identified by screening the list of conference attendees and oral presentation regarding CG adaptation. CGs, clinical guidelines; CoI, conflict of interest; GIN, Guideline International Network.

Participants

The main characteristics of participants, as well as their organisations, are summarised in table 1. Participants worked in nine different organisations from seven countries, the majority being from high-income countries (60%; 6/10). Most participants had over 5 years of experience in CG adaptation (70%; 7/10). Most of the included organisations were research/knowledge-producing centres (67%; 6/9), had over 5 years of experience in CG adaptation (78%; 7/9), had a working group size that ranged from 6 to 20 members (78%; 7/9) and spent less than 2 years to complete their adaptation process (78%; 7/9). Most of these organisations had funding sources from government, medical association operation fees, national/international foundations, or the combination of those above (78%; 7/9). Three participants declared a CoI as a coauthor of published adaptation methodology. Other participants have nothing to declare.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample

| Characteristics of interviewees (n=10) | n (%) |

| Continents (n=10) | |

| Africa | 1 (10) |

| Asia‡ | 3 (30) |

| Europe | 2 (20) |

| North America | 4 (40) |

| Experience in the CG field (n=10) | |

| Experience in developing CGs* | 8 (80) |

| Experience in adapting CGs* | 8 (80) |

| Methodological experience in developing CGs† | 7 (70) |

| Methodological experience in adapting CGs† | 9 (90) |

| CG user | 4 (40) |

| Years of CG adaptation experience (n=10) | |

| 0–5 years | 3 (30) |

| 6–10 years | 3 (30) |

| 11–20 years | 4 (40) |

| Characteristics of organisations (n=9) | n (%) |

| Type of organisations (n=9) | |

| Hospital | 1 (11) |

| Research/knowledge producing organisation | 6 (67) |

| Service provider organisation (community) | 1 (11) |

| University | 2 (22) |

| Professional medical association | 2 (22) |

| Years of CG adaptation practice (n=9) | |

| 0–5 years | 2 (22) |

| 6–10 years | 3 (33) |

| 11–20 years | 3 (33) |

| >20 years | 1 (11) |

| The average size of CG adaptation working group (n=9) | |

| 0–5 | 1 (11) |

| 6–10 | 2 (22) |

| 11–20 | 5 (56) |

| >20 | 1 (11) |

| Average time for CG adaptation (n=9) | |

| 0–1 year | 3 (33) |

| 1–2 years | 4 (44) |

| 2–3 years | 1 (11) |

| NR | 1 (11) |

| Funding source (n=9) | |

| Government funding | 2 (22) |

| Medical association operational fee | 2 (22) |

| National/international foundations | 4 (44) |

| Self-service fee | 1 (11) |

| Pharmacy company | 1 (11) |

| Multiple funding without industry | 3 (33) |

| Multiple funding including industry | 1 (11) |

*Participation in a CG development/adaptation group at least once in the past year.

†Participation in a CG technical team at least once in the past year or participation in methodological research.

‡One expert is from Australia but develops CG adaptation in Philippines, we classified the country as Philippines.

CG, clinical guideline; NR, not reported.

Reasons for adapting CGs

We identified four main reasons for CG adaptation (table 2, online supplemental appendix 03): (1) to develop their own CGs; (2) to implement or endorse source CGs; (3) to update an existing CG and (4) to analyse conflicting recommendations from different source CGs. The most common reason to adapt was to develop CGs for their intended setting based on other existing CGs, by first retrieving and adapting existing CGs that could potentially answer their questions, saving resources and time and avoiding duplication of efforts. Some organisations focused on implementing source CGs in the target setting through CG adaptation. Three organisations also updated their own CGs by adapting newly published CGs, while another conducted adaptation processes only when there were discrepancies among different recommendations for the same topic.

Table 2.

Views and experiences of CG adaptation

| Themes | No of participants |

| Reasons for adapting CGs | |

| Develop their CGs | |

| As part of de novo CG development process | 3 |

| To avoid duplicates and save efforts | 1 |

| To save resources and time | 3 |

| Implementing/endorsing for target settings | 5 |

| Updating existing CGs | 3 |

| Solving recommendations’ controversy | 1 |

| Challenges for adapting CGs | |

| Poor reporting or the limitations of source CG(s) | 2 |

| Limited skills in advanced CG development and adaptation | 3 |

| The intensity in terms of resources and time for adaptation | 2 |

| Specific steps of adaptation process: | |

| Addressing context differences between source CG(s) and adapted CG | 4 |

| Addressing inconsistency and integrate recommendations from different source CG(s) | 3 |

| Updating or supplementing with research evidence | 1 |

| Implementation barriers | 5 |

| Addressing context differences between source CG(s) and the adapted CG | |

| Through panel discussion | 7 |

| Adapting to the target context (at CG level) | |

| Prioritising the source CG(s) according to different factors | 2 |

| Discarding the source CG(s) | 1 |

| Adapting to the target context (at recommendation level) | |

| Evaluating the reason behind and reconsidering the strength of the recommendations | 1 |

| Contextualising by considering different factors | 3 |

| Formulating new recommendations for a specific population (eg, subgroups) | 1 |

| Adapting to the target context (at evidence level) | |

| Supplementing new evidence/other considerations | 2 |

| Reporting the differences when drafting the recommendation | 3 |

| Addressing inconsistencies between recommendations from different source CG(s) | |

| Through panel discussion | 2 |

| Selecting source CG(s) with different criteria (at CG level) | |

| Good quality/rigorous development of source CG(s) | 5 |

| Content relevance/suitability to the target context | 2 |

| Most up to date | 2 |

| Trustworthy source CG(s) | 1 |

| Assessing the reason for inconsistency | |

| At recommendation level | 4 |

| At evidence level | 3 |

| Not applicable when single CG was included | 4 |

| Updating source evidence | |

| Trigger for supplement/update search of source CG(s) | |

| Source CG(s) do not answer all the questions of interest | 3 |

| Source CG(s) are outdated | 1 |

| Source CG(s) are consensus-based | 2 |

| Experts’ suggestions | 2 |

| Way of including new evidence | |

| Literature search (eg, pragmatic search or a full de novo search) | 6 |

| Update the search from source CG(s) | 3 |

| Experts’ suggestions | 3 |

| If the source CG(s) are not evidence-based or do not answer the questions | |

| Start CG de novo development process | 3 |

| Discard the recommendation | 1 |

| Conduct the consensus process | 1 |

| Considering implementation barriers | |

| Way of obtaining information | |

| Experts’ opinion | 4 |

| Literature search | 5 |

| Group discussion | 5 |

| Decision making after consideration of implementation barriers | |

| Modifying the practice instead of change recommendations | 1 |

| Modifying the recommendations | 1 |

| Reporting the differences if needed | 4 |

CGs, clinical guidelines.

Current practice

Six participants reported using their own adaptation methodology.8 32–36 Three of them were based on the ADAPTE instrument and/or the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT framework.4 9 One participant used a published adaptation framework9 and supplemented it with GRADE to rate the certainty of the evidence.37 Two used a guideline quality assessment tool named German Instrument for Methodological Guideline Appraisal (DELBI) to inform the CG adaptation process in their setting.38 Lastly, one participant reported not using a formal methodology. See online supplemental appendix 04 for detailed new methodologies.

Participants reported using the following nine CG adaptation methodologies (table 3):

Table 3.

Main steps of the adaptation process

| Adaptation methodology/year | Selection of the scope and source CG(s) | Assessment of source materials | Decision-making process | External review and follow-up |

| ADAPTE 20109 |

|

|

|

|

| Adopt–Contextualise–Adapt Framework 201636 |

|

|

|

|

| ACP guidance statement 201934 |

|

|

|

|

| ASCO CG endorsement/adaptation methodology 201932 |

|

|

|

|

| CCO endorsement protocol 201935 |

|

|

|

|

| DynaMed editorial methodology 201933 |

|

|

|

|

| DELBI 201938 |

|

|

|

|

| GRADE-ADOLOPMENT 20174 |

|

|

|

|

| Piloted adaptation framework 20178 |

|

|

|

|

| Adaptation experience 2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

The criteria or clarification for topic/scope/questions selection and source CG screening: 1: Quote: ‘At that time we have identified the top of the conditions for stroke and low back pain. We look at the literature, even at that time, there were so many CGs published already for those two topics.’ (Participant 10) 2: Sources were from PubMed and GIN library in the last five years or current practice, and Web of science. 3: Criteria are: high-quality CG developers, detailed CoI management, and financially independence; or applicant organisations’ preferable. 4: Quote: ‘If the CG adaptation groups plan to develop a new CG, they will search for the existing evidence from published CGs first.’ (Participant 06) 5: Assessed the relevance to stakeholders, proposed by a professional group or prioritised by stakeholders; In addition, GRADE approach and Evidence to Decision frameworks availability are required. 6: Quote: ‘A lot of kind of process will be in a national process, and there will be specific health questions and PICOs. Then we will be asked to conduct SRs. We do have in that particular process is that the SR would include first to look at what CGs are out there, and then we will look at what SRs are out there before we conduct our systematic review.’ (Participant 09) | ||||

|

The considerations or clarifications for the assessment of source materials: a: Quote: ‘We quickly appraise source CGs using AGREE II to ensure the source CG you are basing on are good quality; … To adapt, we update the search and include new evidence. …It means you take evidence surrounded for instance in the local context settings, there might be a new paper has been published locally, not internationally, but it answers the questions the local context actually asked. Then the recommendation could change.’ (Participant 10) b: Quote: ‘We will look at the evidence and do the assessment ourselves. If we do the quality assessment, we look at the systematic review, and if the systematic review doesn’t make sense, we will look at the primary studies.’ (Participant 07) c: Quote: ‘We do not have a numeric cut-off for AGREE II.’ (Participant 02) d: Criteria: Scope, relevance, and timing, quality and methods, resource availability; acceptability; e: Interpretation and justification, applicability/relevance, qualifications & clarifications. f: Quote: ‘If we see many CGs agree, and we know the evidence is high quality, we don’t need to go into a lot of greater depth because everything is pointing into the right direction. If we see the CGs are disagreeing, then we may have to evaluate and see why they are disagreeing and that where we checked the currency of the content to help us to understand the disagreement.’ (Participant 01) g: Quote: ‘We don’t have a critical cut off to choose which CG to use, we do prioritise by the quality of the CG. The CG adaptation group will create CG synopses, prefer methodologically sound recommendations. …The adaptation group should be transparent if they have appropriate changes in the recommendations when the adaptation process and provide the scientific rationale behind the change.’ (Participant 03) h: We conducted rapid SRs of patient’s value, cost-effectiveness; We considered local data suggested by panel members (patients’ value and preference, cost, resource use, population prevalence and incidence). i: Quote: ‘We request the adaptation group to assess the quality of the CGs using the AGREE II instrument. We do not have a cut-off of the AGREE score, because sometimes there are few source CGs for the consideration of adaptation. … If there are no clear answers for several questions in the source CG(s), they looked at existing Cochrane SRs but do not conduct a new one. No cost-effectiveness evidence was searched, but patients’ values and preferences, yes.’ (Participant 08) j: Quote: ‘If there is a CG of good quality, those are the recommendations. So, if I see a CG from NICE, or from European, our society will have both or do an AGREE appraisal. If there are good quality, I transparently put in my review about what the quality it was, and I pooled out the recommendations that could be relevant for that health question. And then I also look at the underlying evidence from those CGs, also the SRs, that independent of pooling out the if possible, a GRADE evidence table, or something that explains the magnitude of the effect and the certainty of evidence.’ (Participant 09) | ||||

|

The considerations or clarifications for the decision-making process: α: Quote: ‘In the most recent CG we published, we extracted the source recommendations from the source CGs, we have developed composite recommendations, which is the new recommendation based on the other CG have said…’ (Participant 10) β: ‘Current evidence, current CGs, and clinical expertise’s recommendations to support clinical decision making’. µ: Quote: ‘For people who work in the CG adaptation group they have any Evidence to Decision framework, so they will look at the quality of evidence from source CGs or other SRs.’ (Participant 09) | ||||

|

The considerations or clarifications for the external review process: * Quote: ‘Our organisation doesn’t do for the CG adaptation group, but they do the external review process by themselves’. (Participant 03) ƚ Quote: ‘The national group I am referring to send the adapted CG out for comment, feedback, and input as external review. We don’t have a specific small external review team broadly.’ (Participant 10) | ||||

DELBI is a CG assessment tool used by adaptation group to inform CG adaptation.

ACP, American College of Physicians; ADAPTE, Resource Toolkit for Guideline Adaptation; AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CCO, Cancer Care Ontario; CGs, clinical guidelines; CoI, conflict of interest; DELBI, German Instrument for Methodological Guideline Appraisal; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations; NA, not applicable; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SR, systematic review.

ADAPTE instrument.9

Adopt–Contextualise–Adapt framework.36

American College of Physicians guidance statement.34

American Society of Clinical Oncology CG endorsement/adaptation methodology.32

Cancer Care Ontario’s endorsement protocol.35

DynaMed editorial methodology.33

DELBI38

GRADE-ADOLOPMENT framework.4

Piloted adaptation Framework.8

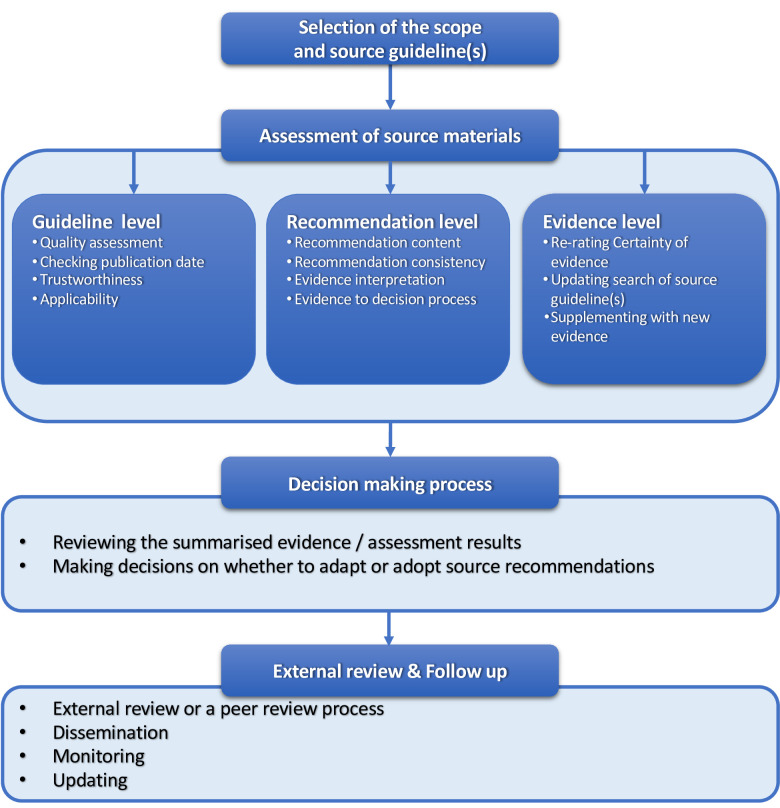

Seven of the nine methodologies were not identified in previous publications. Based on the framework analysis, we identified four main steps in the process of adapting CGs (figure 2 and table 3).

Figure 2.

Main steps of the adaptation process. CGs, clinical guidelines.

Selection of the scope and source CG(s)

CG adaptation groups defined or identified CG topic, scope and key questions before or after the selection of source CGs. Most organisations reported first predefining the topic, scope and key questions, then searching for existing relevant or implementable CGs.9 32 33 35 Some also identified key questions from newly released, well-known and trustworthy CGs.4 35 The screening criteria of source CGs for a further appraisal at this preliminary stage were: (1) stakeholders’ preferences of CG topic;4 32 35 (2) a good reputation of the CGs developers;32 34 35 (3) methodological quality of the source CGs;8 9 (4) clinical relevance to the target context33 and (5) CoIs management and funding independence of the source CGs.32

Assessment of source materials

CG adaptation groups reviewed and assessed source CGs. We stratified this step into three levels based on participants’ reported practice:

Guideline level: The guideline quality, trustworthiness, transparency of the process, value and relevance to clinical practice, resource availability and inclusion of latest evidence (up to date) were assessed.9 32–36 To rate the CG quality, most participants applied the AGREE II instrument. To ensure source CGs were up to date, some participants conducted a comprehensive search and chose the most recent CG among those with similar quality.

Recommendation level: The recommendation content, the formulation process of source recommendations (eg, how the net benefit, resources, patients’ values and other criteria were considered), as well as the strength of recommendation were reviewed.8 9 32–35 Some participants used a CG summary format to display recommendations and facilitate panel discussion.8 32 38 Recommendations were modified as needed based on the discussion of the evidence.4 33 34

Evidence level: The certainty of the evidence of the source recommendations was reviewed.4 6 9 33–35 Some participants assessed the risk of bias of included primary studies and systematic reviews, and the certainty of the source evidence.32 33 Besides, updating the original search or supplementing with new evidence was also conducted at this level, if necessary.4 6 8 32 33 38 The reasons to update source evidence were: (1) it did not clearly answer all the key questions; (2) it was not adequately searched or appraised; (3) it was considered outdated (eg, more than 3 years since the last search) or (4) when panel experts recommended it (table 2, online supplemental appendix 03).

Decision-making process

CG adaptation groups review the summarised evidence and decide whether to adapt (with modifications) or adopt (without modifications) the source recommendations. To support the decision, some participants presented the summarised evidence using a matrix or direct links containing both recommendations and evidence. Where CG developers of source CGs used GRADE-ADOLOPMENT, the GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks of source CGs were reviewed or completed by the CG adaptation groups.4 Decisions were made mostly through panel discussion or voting.

External review and follow-up

Following the decision-making process, an external review or a peer review process was conducted. Moreover, a follow-up process was scheduled, including the plan for dissemination, monitoring and updating. Those processes were similar to de novo CG development processes. However, some organisations also consulted source CG developers on the changes made to source recommendations.9 32

Challenges for adapting CGS

Most participants reported challenges to the adaptation and development of CGs in general (table 2, online supplemental appendix 03). Challenges of the adaptation process were: (1) limitations from source CGs, including poor reporting and quality; (2) limited advanced CG development and adaptation skills of the CG adaptation group; (3) resource and time intensity required for adaptation; (4) challenges arising from specific adaptation process, including how to address and report context differences between source CGs and adapted CGs; how to address inconsistency and integrate recommendations from different source CGs, and how to update source evidence, including update search and supplement with additional evidence and (5) implementation barriers of CG adaptation.

We identified participants’ strategies for dealing with the specific challenges within the adaptation process and implementation issues (table 2, online supplemental appendix 03).

Addressing context differences between source CG(s) and adapted CG

According to participants’ views and experiences, the differences in setting or population between source CGs and target context were addressed mainly through panel discussion and experts’ opinions. CG adaptation groups could address these differences at multiple levels: (1) at CG level, by prioritising source CGs according to different criteria or discarding the entire source CGs if the difference was large enough; (2) at recommendation level, by modifying the strength of recommendations due to differences after considering the balance of the benefits and harms, other factors (eg, acceptability or feasibility) or formulating new recommendations (eg, new recommendations for subgroup population) and (3) at evidence level, by supplementing with new evidence (eg, local data). Finally, participants stated that differences and modifications were reported or documented along with the adapted CG.

Addressing inconsistencies between recommendations from different source CG(s)

The inconsistency between recommendations was addressed by prioritising those source CGs that (1) had good quality or rigorous development process, (2) were relevant to the target context, (3) were most up to date and (4) were considered trustworthy. The reasons behind the inconsistency were also assessed on the recommendation and evidence level. At the recommendation level, whether (1) the inconsistency was due to a different target population, (2) the evidence was sufficient or up to date and (3) the evidence was appropriately interpreted. At the evidence level, whether the source evidence was appropriately assessed.

Updating source evidence

CG adaptation groups sometimes used evidence that is more recent or relevant in addition to the source evidence. To identify new evidence, participants relied on literature searches, including full de novo search or pragmatic search (eg, PubMed, local databases or Cochrane database), updating the source search or experts’ suggestions. However, half of the participants expressed their unwillingness to supplement with new evidence since they generally based on the source CGs, maintaining the merits of adaptation to save resources and time. If the evidence base of the source CGs was unclear or did not answer their questions, participants conducted a de novo CG development process, discarded the recommendation or formulated recommendations based on the discussion.

Considering implementation barriers

CG adaptation groups considered different implementation barriers, including medical policy, cost of the intervention or management, equity, applicability or feasibility. The implementation barriers were identified through experts’ opinions (eg, policymakers, primary carers or CG adaptation panel) or literature search (eg, local data). Most of the CG adaptation groups held a discussion to address implementation barriers by considering the applicability of their settings. As a result, either the recommendations or the implementation plan were modified to facilitate the CG adaptation. Finally, the differences in implementation considerations with the source CGs and the modifications were reported in the adapted CGs.

Discussion

Our study summarises the current practice of CG adaptation derived from different methodologies used by nine organisations worldwide. We structured adaptation processes into four steps, including three-level source materials assessment (guideline, recommendation and evidence level). We identified the reasons of CG adaptation groups for adaptation, the challenges faced during the process, and their strategies to overcome these. Most of the identified methodologies were not discussed in previous systematic reviews.

Our findings in the context of previous research

We described reasons for conducting adaptation processes, which has not been previously highlighted in the literature.1 7 Fervers et al defined CG adaptation as an alternative methodology to developing de novo CGs or as a systematic method to improve implementation.39 Our findings reflect this definition and suggest that most adaptation groups are conducting adaptation processes as part of their CG de novo development. Besides, we identified that adaptation processes could also play a role in updating and harmonising source recommendations.

We identified nine adaptation methodologies that CG adaptation groups have been using, two of which had been described by previous reviews, while seven had not.1 7 Unlike previous reviews, our study—in addition to summarising and comparing published frameworks—describes the used adaptation processes in a novel structured way, including the stratified assessment of source materials. This stratification fits the conceptual progression of CG adaptation; Fervers et al considered two levels in this process, the guideline level (quality of source CGs) and recommendation level (coherence between evidence and recommendations, and the applicability of specific recommendations).39 More recently, Wang et al described a shift towards an evidence level (evidence of recommendations).7

To this day, very few studies have explored the challenges arising from the adaptation process. Only one review has described the limitations of using adaptation frameworks and gaps for adaptation knowledge.7 Our study identified that adaptation challenges arise from limitations of source CGs (poor quality or reporting), limitations of adaptation settings (lacking resources or skills), and the complexity of the adaptation process. In addition, we described the strategies used by the participants to address specific steps of the adaptation process, thereby providing new knowledge to inform more streamlined adaptation processes: for contextualisation and reconciliation, adaptation groups could address different issues at three levels of source materials assessment; for updating source evidence, they could add new evidence through a literature search or experts’ suggestions; for implementation, adaptation groups could hold a panel discussion, and consider modifying recommendations or the implementation plan if necessary.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has some limitations. We only conducted ten interviews and hence could have missed additional adaptation methods from other countries. In addition, we recruited participants from published adapted guidelines and G-I-N attendees, limiting the study samples to experts with sufficiently large experience in CG adaptation or development field. Besides, we did not interview non-English-speakers, which may bias the study results. Finally, we did not conduct data analysis based on country income due to the small sample size and fewer participants from LMICs that lack resources and technical/methodological experts.21 The challenges highlighted by our study are likely to be universal within experienced guideline adaptation developers (eg, intensity and complexity of adaptation process, limitations of source CGs, and implementation barriers). However, some specific challenges, such as specific contextualisation issues, would be under-reported in our study.

Our study also has some strengths. We invited CG adaptation experts from identified adapted CGs, attendees from the G-I-N conference, and other additional strategies or sources to ensure representativeness. To reduce participant’s bias, we complemented participants’ views and experiences with their adaptation methodology publications. The interview format allowed us to explore the challenges of CG adaptation in depth and how the participants address specific issues. Moreover, we conducted a framework analysis based on published adaptation frameworks, ensuring our findings’ comprehensiveness. Finally, we presented the results in a user-friendly format, including tables and figures.

Implication for practice

CG adaptation has been increasingly used in the guideline arena with diverse initiatives emerging and can be used as a pragmatic methodology to develop recommendations. In 2020, an international WHO collaboration project developed a living map of the latest evidence-based recommendations for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.40 This project makes the source materials available online and allows CG developers to adopt or adapt relevant recommendations for their questions of interest. CG developers could therefore avoid duplication of efforts and focus on how to implement scientific guidance to tackle this public health crisis.

Adaptation processes should be conducted rigorously. The identified core steps of the adaptation process and assessment levels could help CG adaptation groups streamline their future initiatives. CG adaptation groups could predefine the level of source materials to evaluate, simplifying the adaptation process while remaining rigorous. The adaptation process overlaps with the CG de novo process when assessing source materials at the recommendation level and the evidence level. At the recommendation level, CG adaptation groups need to review the factors considered to formulate source recommendations. This process uses an approach similar to that applied by the source panels and requires explicit and transparent reporting on the formulation of source recommendations to achieve feasibility. For example, if source CGs followed the GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks, the adaptation groups need to review the interpretation of evidence regarding each factor considered under the Evidence to Decision frameworks. Not all robust source CGs use the GRADE Evidence to Decision frameworks, but yet, describe in detail how they make recommendations. Similarly, at the evidence level, the boundary between the CG adaptation process and the de novo process blurs. The notable difference could be that a de novo process conducts a full de novo search while the adaptation process updates the source search or supplements it with local evidence. Although the structured adaptation process could be used as a framework, its usability should be further formally assessed and validated.

Implication for future research

There is still room for improving adaptation methodology, especially the efficiency of adaptation processes and the quality as well as credibility of CG adaptation. Besides, there is no framework to guide CG adaptation groups to make judgements on whether to adapt, adopt or develop de novo recommendations based on the assessment of source materials. Although the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT is available, it requires the Evidence to Decisions frameworks from source CGs. A standardised and pragmatic adaptation methodology, including guidance on how to make judgements, should be developed. Furthermore, there is still a need of a validated quality assessment tool and comprehensive reporting guidance to improve the rigorous CG adaptation. The structured adaptation process could be considered as a critical aspect of the quality assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

YS is a doctoral candidate for the PhD in Methodology of Biomedical Research and Public Health (Department of Paediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Preventive Medicine), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Footnotes

Contributors: YS, PA-C, LMG, MB, EAA, FC and RWMV participated in protocol drafting. YS collected and analysed data. MB and JL reviewed the data for accuracy. ENdG provided methodological contributions for the data analysis. YS and PA-C interpreted the results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version. YS took responsibility for guaranteeing the overall content and ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Funding: YS is funded by China Scholarship Council (No 201707040103).

Competing interests: EAA has intellectual CoIs related to his contribution to the development of methods of guideline adaptation, the RIGHT statement and methodological studies in the field.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The protocol obtained a waiver approval (did not involve patients, biological samples or clinical data) from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain).

References

- 1.Darzi A, Abou-Jaoude EA, Agarwal A, et al. A methodological survey identified eight proposed frameworks for the adaptation of health related guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;86:3–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okely AD, Ghersi D, Hesketh KD, et al. A collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines - The Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the early years (Birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. BMC Public Health 2017;17:869. 10.1186/s12889-017-4867-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgers JS, Anzueto A, Black PN, et al. Adaptation, evaluation, and updating of guidelines: article 14 in integrating and coordinating efforts in COPD Guideline development. An official ATS/ERS workshop report. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012;9:304–10. 10.1513/pats.201208-067ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. Grade evidence to decision (ETD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:101–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, et al. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in Guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:228–36. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kristiansen A, Brandt L, Agoritsas T, et al. Adaptation of trustworthy guidelines developed using the grade methodology: a novel five-step process. Chest 2014;146:727–34. 10.1378/chest.13-2828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Norris SL, Bero L. The advantages and limitations of guideline adaptation frameworks. Implement Sci 2018;13:72. 10.1186/s13012-018-0763-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehndiratta A, Sharma S, Gupta NP, et al. Adapting clinical guidelines in India-a pragmatic approach. BMJ 2017;359:j5147. 10.1136/bmj.j5147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The ADAPTE Collaboration . The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation. version 2.0, 2009. Available: http://www.g-i-n.net

- 10.Amer YS, Elzalabany MM, Omar TI, et al. The 'Adapted ADAPTE': an approach to improve utilization of the ADAPTE guideline adaptation resource toolkit in the Alexandria Center for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract 2015;21:1095–106. 10.1111/jep.12479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harstall C, Taenzer P, Zuck N, et al. Adapting low back pain guidelines within a multidisciplinary context: a process evaluation. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:773–81. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kristiansen A, Brandt L, Agoritsas T, et al. Applying new strategies for the National adaptation, updating, and dissemination of trustworthy guidelines: results from the Norwegian adaptation of the antithrombotic therapy and the prevention of thrombosis, 9th ED: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2014;146:735–61. 10.1378/chest.13-2993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alper BS, Tristan M, Ramirez-Morera A, et al. RAPADAPTE for rapid Guideline development: high-quality clinical guidelines can be rapidly developed with limited resources. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:268–74. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rycroft-Malone J, Duff L. Developing clinical guidelines: issues and challenges. J Tissue Viability 2000;10:144–53. 10.1016/S0965-206X(00)80004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muth C, Gensichen J, Beyer M, et al. The systematic guideline review: method, rationale, and test on chronic heart failure. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:74. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amer YS, Wahabi HA, Abou Elkheir MM, et al. Adapting evidence-based clinical practice guidelines at university teaching hospitals: a model for the eastern Mediterranean region. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25:550–60. 10.1111/jep.12927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCaul M, Ernstzen D, Temmingh H, et al. Clinical practice guideline adaptation methods in resource-constrained settings: four case studies from South Africa. BMJ Evid Based Med 2020;25:193–8. 10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darzi A, Harfouche M, Arayssi T, et al. Adaptation of the 2015 American College of rheumatology treatment guideline for rheumatoid arthritis for the eastern Mediterranean region: an exemplar of the grade Adolopment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:183. 10.1186/s12955-017-0754-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdul-Khalek RA, Darzi AJ, Godah MW, et al. Methods used in adaptation of health-related guidelines: a systematic survey. J Glob Health 2017;7:020412. 10.7189/jogh.07.020412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godah MW, Abdul Khalek RA, Kilzar L, et al. A very low number of national adaptations of the world Health organization guidelines for HIV and tuberculosis reported their processes. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;80:50–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maaløe N, Ørtved AMR, Sørensen JB, et al. The injustice of unfit clinical practice guidelines in low-resource realities. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e875–9. 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00059-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y, Darzi A, Ballesteros M, et al. Extending the RIGHT statement for reporting adapted practice guidelines in healthcare: the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031767. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong ASP, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2015;42:533–44. 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez García L, Sanabria AJ, Araya I, et al. Efficiency of pragmatic search strategies to update clinical guidelines recommendations. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:57. 10.1186/s12874-015-0058-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernooij RWM, Alonso-Coello P, Brouwers M, et al. Reporting items for updated clinical guidelines: checklist for the reporting of updated guidelines (checkup). PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002207. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanabria AJ, Pardo-Hernandez H, Ballesteros M, et al. The UpPriority tool was developed to guide the prioritization of clinical guideline questions for updating. J Clin Epidemiol 2020;126:80–92. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, et al. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. sage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, et al. Thematic Analysis. In: Liamputtong P, ed. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.QSR International . NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software [Software], 1999. Available: https://qsrinternational.com/nvivo/nvivo-products/

- 32.Shah MA, Oliver TK, Peterson DE, et al. ASCO clinical practice guideline Endorsements and adaptations. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:834–40. 10.1200/JCO.19.02839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dynamed evidence-based methodology, 2019. Available: https://www.dynamed.com/home/editorial/evidence-based-methodology

- 34.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Lin JS, et al. The development of clinical guidelines and guidance statements by the clinical guidelines Committee of the American College of physicians: update of methods. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:863–70. 10.7326/M18-3290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CCO guideline endorsement protocol 2019.

- 36.Dizon JM, Machingaidze S, Grimmer K. To adopt, to adapt, or to contextualise? the big question in clinical practice Guideline development. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:442. 10.1186/s13104-016-2244-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schünemann HBJ, Guyatt G, Oxman A, eds. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 38.DELBI . German instrument for methodological guideline, 2019. Available: https://www.leitlinien.de/mdb/edocs/pdf/literatur/german-guideline-appraisal-instrument-delbi.pdf

- 39.Fervers B, Burgers JS, Haugh MC, et al. Adaptation of clinical guidelines: literature review and proposition for a framework and procedure. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:167–76. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.COVID19 recommendations and gateway to Contextualization. Available: https://covid19.recmap.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-053587supp001.pdf (385.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.