On Nov 25, 2021, about 23 months since the first reported case of COVID-19 and after a global estimated 260 million cases and 5·2 million deaths,1 a new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern (VoC), omicron,2 was reported. Omicron emerged in a COVID-19-weary world in which anger and frustration with the pandemic are rife amid widespread negative impacts on social, mental, and economic wellbeing. Although previous VoCs emerged in a world in which natural immunity from COVID-19 infections was common, this fifth VoC has emerged at a time when vaccine immunity is increasing in the world.

The emergence of the alpha, beta, and delta SARS-CoV-2 VoCs were associated with new waves of infections, sometimes across the entire world.3 For example, the increased transmissibility of the delta VoC was associated with, among others, a higher viral load,4 longer duration of infectiousness,5 and high rates of reinfection, because of its ability to escape from natural immunity,6 which resulted in the delta VoC rapidly becoming the globally dominant variant. The delta VoC continues to drive new waves of infection and remains the dominant VoC during the fourth wave in many countries. Concerns about lower vaccine efficacy because of new variants have changed our understanding of the COVID-19 endgame, disabusing the world of the notion that global vaccination is by itself adequate for controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indeed, VoCs have highlighted the importance of vaccination in combination with existing public health prevention measures, such as masks, as a pathway to viral endemicity.7

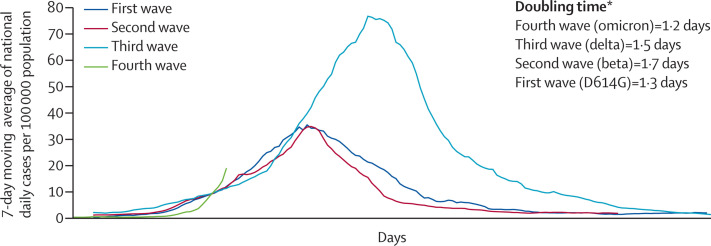

The first sequenced omicron case was reported from Botswana on Nov 11, 2021, and a few days later another sequenced case was reported from Hong Kong in a traveller from South Africa.8 Several sequences from South Africa followed, after initial identification that the new variant was associated with an S-gene target failure on a specific PCR assay because of a 69–70del deletion, similar to that observed with the alpha variant.9 The earliest known case of omicron in South Africa was a patient diagnosed with COVID-19 on Nov 9, 2021, although it is probable that there were unidentified cases in several countries across the world before then. In South Africa, the mean number of 280 COVID-19 cases per day in the week before the detection of omicron increased to 800 cases per day in the following week, partly attributed to increased surveillance.10 COVID-19 cases are increasing rapidly in the Gauteng province of South Africa; the early doubling time in the fourth wave is higher than that of the previous three waves (figure , appendix).10

Figure.

SARS-CoV-2 cases in first, second, third, and fourth waves, Gauteng Province of South Africa

*Doubling time for the first 3 days after the wave threshold of ten cases per 100 000 population. 7-day moving average cases per 100 000 population up to Dec 1, 2021. Data are from the Department of Health, Government of South Africa.10

The principal concerns about omicron include whether it is more infectious or severe than other VoCs and whether it can circumvent vaccine protection. Although immunological and clinical data are not yet available to provide definitive evidence, we can extrapolate from what is known about the mutations of omicron to provide preliminary indications on transmissibility, severity, and immune escape. Omicron has some deletions and more than 30 mutations, several of which (eg, 69–70del, T95I, G142D/143–145del, K417N, T478K, N501Y, N655Y, N679K, and P681H) overlap with those in the alpha, beta, gamma, or delta VoCs.8 These deletions and mutations are known to lead to increased transmissibility, higher viral binding affinity, and higher antibody escape.11, 12 Some of the other omicron mutations with known effects confer increased transmissibility and affect binding affinity.11, 12 Importantly, the effects of most of the remaining omicron mutations are not known, resulting in a high level of uncertainty about how the full combination of deletions and mutations will affect viral behaviour and susceptibility to natural and vaccine-mediated immunity.

The impact of omicron on transmissibility is a concern. If the overlapping omicron mutations maintain their known effects, then higher transmissibility is expected, particularly because of the mutations near the furin cleavage site. Early epidemiological evidence suggests that cases are rising in South Africa and that PCR tests with S-gene target failure are also rising. Although omicron is likely to be highly transmissible, it is not yet clear whether it has greater transmissibility than delta, although preliminary indications suggest that it is spreading rapidly against a backdrop of ongoing delta-variant transmission and high levels of natural immunity to the delta variant. If this trend continues, omicron is anticipated to displace delta as the dominant variant in South Africa.

We await knowledge of how this new VoC will impact clinical presentation. At this stage, the available anecdotal data from clinicians at the front lines in South Africa suggest that patients with omicron are younger people with a clinical presentation similar to that of past variants.13 Although no alarming clinical concerns have been raised thus far, this anecdotal information should be treated with caution given that severe COVID-19 cases typically present several weeks after the initial symptoms associated with mild disease.

Immune escape is another concern. In the absence of data on observational vaccine effectiveness and antibody-neutralisation studies on vaccinee sera, preliminary data from the national PCR testing programme could provide some clues. Data on positive PCR tests in people with previous positive tests suggest an increase in cases of reinfection in South Africa. However, the increased use of rapid antigen tests and incomplete capturing of negative results have complicated the interpretation of test positivity rates, which have risen to about four times the previous rate in the past week. Notwithstanding this limitation, the increase in cases of reinfection is in keeping with the immune-escape mutations present in omicron.

Although there are conflicting reports on whether COVID-19 vaccines have consistently retained high efficacy for each of the four VoCs preceding omicron, clinical trials have reported lower efficacy for some vaccines in transmission settings in which the beta variant is dominant. Previous variants have lowered vaccine efficacy; for example, the ChAdOx1 vaccine was 70% effective in preventing clinical infections for the D614G variant in the UK, but this efficacy decreased to 10% for the beta variant in South Africa.14 However, the efficacy of the BNT162b2 vaccine in preventing clinical infections was retained across both the D614G and beta variants.14 Given that omicron has a larger number of mutations than previous VoCs, the potential impact of omicron on the clinical efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines for mild infections is not clear.

Thus far, most COVID-19 vaccines have remained effective in preventing severe COVID-19, hospitalisation, and death, for all previous variants, because this efficacy might be more dependent on T-cell immune responses than antibodies. Observational studies from Qatar (n=231 826)15 and Kaiser Permanente (n=3 436 957)16 reported vaccine efficacy of more than 90% in preventing hospital admissions during delta-variant transmission, even up to 6 months after vaccination. Observational data from the state of New York, USA (n=8 834 604) indicated high vaccine efficacy in preventing severe disease in people older than 65 years, with varying levels of protection conferred by different vaccines—95% for BNT162b2, 97% for mRNA-1273, and 86% for Ad26.COV2.S17—with minimal declines in protection 6 months after vaccination.

In terms of diagnostics, the omicron variant is detectable on widely used PCR platforms in South Africa. There is no reason to believe that current COVID-19 treatment protocols and therapeutics would no longer be effective, with the possible exception of monoclonal antibodies, for which data on the omicron variant's susceptibility are not yet available. Importantly, existing public health prevention measures (mask wearing, physical distancing, avoidance of enclosed spaces, outdoor preference, and hand hygiene) that have remained effective against past variants should be just as effective against the omicron variant.

Extrapolations based on known mutations and preliminary observations, which should be interpreted with caution, indicate that omicron might spread faster and might escape antibodies more readily than previous variants, thereby increasing cases of reinfection and cases of mild breakthrough infections in people who are vaccinated. On the basis of data from previous VoCs, people who are vaccinated are likely to have a much lower risk of severe disease from omicron infection. A combination prevention approach of vaccination and public health measures is expected to remain an effective strategy.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com on January 6, 2021

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.WHO WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.WHO Update on omicron. Nov 28, 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2021-update-on-omicron

- 3.Fontanet A, Autran B, Lina B, Kieny MP, Abdool Karim SS, Sridhar D. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;397:952–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo CH, Morris CP, Sachithanandham J, et al. Infection with the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant is associated with higher infectious virus loads compared to the alpha variant in both unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.15.21262077. published online Aug 20. (preprint). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Chen R, Hu F, et al. Transmission, viral kinetics and clinical characteristics of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Guangzhou, China. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend JP, Hassler HB, Wang Z, et al. The durability of immunity against reinfection by SARS-CoV-2: a comparative evolutionary study. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e666–e675. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Lancet COVID-19 Commission Task Force on Public Health Measures to Suppress the Pandemic SARs-CoV-2 variants: the need for urgent public health action beyond vaccines. 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef3652ab722df11fcb2ba5d/t/60a3d54f8b42b505d0d0de4f/1621349714141/NPIs+TF+Policy+Brief+March+2021.pdf

- 8.GISAID Tracking of variants. 2021. https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/

- 9.Volz E, Mishra S, Chand M, et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England. Nature. 2021;593:266–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. Government of South Africa COVID-19. Dec 2, 2021. https://sacoronavirus.co.za/ (accessed Dec 2, 2021).

- 11.Greaney AJ, Starr TN, Gilchuk P, et al. Complete mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain that escape antibody recognition. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey WT, Carabelli AM, Jackson B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Communicable Diseases Frequently asked questions for the B.1.1.529 mutated SARS-CoV-2 lineage in South Africa. 2021. https://www.nicd.ac.za/frequently-asked-questions-for-the-b-1-1-529-mutated-sars-cov-2-lineage-in-south-africa/

- 14.Abdool Karim SS, de Oliveira T. New SARS-CoV-2 variants: clinical, public health, and vaccine implications. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1866–1868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2100362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, et al. Waning of BNT161b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114114. published online Aug 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398:1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg ES, Dorabawila V, Easton D, et al. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in New York state. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116063. published online Dec 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.