Abstract

Using a two-hybrid screening with TOM1, a putative ubiquitin-ligase gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we isolated KRR1, a homologue of human HRB2 (for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev-binding protein 2). To characterize the gene function, we constructed temperature-sensitive krr1 mutants and isolated two multicopy suppressors. One suppressor is RPS14A, encoding a 40S ribosomal protein. The C-terminal-truncated rpS14p, which was reported to have diminished binding activity to 18S rRNA, failed to suppress the krr1 mutant. The other suppressor is a novel gene, KRI1 (for KRR1 interacting protein; YNL308c). KRI1 is essential for viability, and Kri1p is localized to the nucleolus. We constructed a galactose-dependent kri1 strain by placing KRI1 under control of the GAL1 promoter, so that expression of KRI1 was shut off when transferring the culture to glucose medium. Polysome and 40S ribosome fractions were severely decreased in the krr1 mutant and Kri1p-depleted cells. Pulse-chase analysis of newly synthesized rRNAs demonstrated that 18S rRNA is not produced in either mutant. However, wild-type levels of 25S rRNA are made in either mutant. Northern analysis revealed that the steady-state levels of 18S rRNA and 20S pre-rRNAs were reduced in both mutants. Precursors for 18S rRNA were detected but probably very unstable in both mutants. A myc-tagged Kri1p coimmunoprecipitated with a hemagglutinin-tagged Krr1p. Furthermore, the krr1 mutant protein was defective in its interaction with Kri1p. These data lead us to conclude that Krr1p physically and functionally interacts with Kri1p to form a complex which is required for 40S ribosome biogenesis in the nucleolus.

Ribosome biosynthesis is a complex process that occurs in a specialized subnuclear compartment termed the nucleolus in eukaryotic cells. There, 100 to 200 copies of the rDNA unit are repeated on chromosome XII in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The rRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase I to produce the 35S rRNA precursor, which is rapidly processed, resulting in the separation of the pre-rRNAs destined for the small and large ribosomal subunits. The 20S rRNA precursor is matured to 18S rRNA for 40S ribosome subunits, and the 27S pre-rRNA is processed to the mature 25S and 5.8S rRNAs for 60S subunits (reviewed in reference 15).

These rRNA-processing events are coupled with ribosomal assembly, which requires a large number of nonribosomal protein trans-acting factors and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) as well as ribosomal proteins. Such nucleolar proteins include rRNA-modifying enzymes, endo- and exonucleases, RNA helicases, and components of small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein complexes (15). For example, Nop1p, a typical nucleolar protein (an orthologue to human fibrillarin) is a component of C/D-box snoRNP, which is involved in pre-rRNA 2′-O-ribose methylation and rRNA processing (1, 23, 27).

TOM1 encodes a putative ubiquitin-ligase. At high temperatures, the tom1 mutant exhibits pleiotropic phenotypes, such as G2/M arrest in the cell cycle, accumulation of mRNAs in the nucleus, fragmentation of the nucleolus, and impaired heat stress responses (22, 28). Hoping to identify the substrates of Tom1p, we screened Tom1p-interacting proteins by the two-hybrid system and isolated the KRR1 gene. KRR1 encodes a protein containing a KRR motif conserved from yeast to human cells and was shown to be essential for cell viability (8), but KRR1 has not been characterized yet. Here we report the characterization of KRR1 and a novel KRI1 (KRR1-interacting protein; YNL308c) gene of budding yeast cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and genetic manipulations.

Strains of S. cerevisiae used in this study are described in Table 1. Techniques for yeast genetics, molecular biological experiments, and the composition of media are described elsewhere (12, 21). Plasmid vector YEplac181 was described previously (7). Plasmid pTS1010 (YCp-KRR1-TRP1) was constructed by cloning the KRR1 open reading frame (ORF) flanked by the 304-bp upstream and 552-bp downstream regions into pRS314 (24). Plasmid pTS1011 (YIp-KRR1-5HA) carries the KRR1 gene fused with five copies of the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag at the C-terminal region of KRR1 and was integrated into the KRR1 locus of diploid strain W303. Haploid strain YST029-4A containing the tagged gene was isolated by tetrad dissection. Plasmid pTS1013 (YCp-KRR1-2HA-TRP1), pTS1053-17 (YCp-krr1-17-2HA), or pTS1053-18 (YCp-krr1-18-2HA) was constructed by cloning PCR products into a YCplac-based vector pTS903CT, which was constructed to fuse the codons for a double-HA tag to the 3′ region of a gene of interest. Plasmid pTS1034 (YCp-KRR1-2HA-LEU2) has the same fragment of pTS1013 on pTS903CL, a YCplac111-based vector (7) for tagging the HA epitope. Plasmid pTS068 (YCp-NOP1-GFP) was constructed as follows: the DNA sequence of the NOP1 ORF plus a 1-kb 5′-upstream region was amplified by PCR and cloned into pTS070, which was constructed to express a fusion gene with enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Clontech) at the 3′ end of a gene of interest. pTS1501 (YEp-RPS14A) was isolated from a YEpl3-based genomic library and contained a 7.5-kb insert. The 2.4-kb HindIII-SalI fragment carrying RPS14A and SNR65 was cloned into YEplac181 (7), and the resulting plasmid suppressed krr1. When a part of RPS14A was deleted with EcoRI, the resulting plasmid lost the ability to suppress krr1. To introduce a premature stop codon into the C-terminal region of RPS14A, we used the following primers, TCTACCCTGCAGAACTCAGGTGGAG for pTS1506 (rpS14-ΔC11) and CAATACCTGCAGAACTCATCATCTTC for pTS1508 (rpS14-CryR). Underlined nucleotides indicate the introduced stop codons. Both pTS1506 and pTS1508 carry the 2.4-kb HindIII-SalI fragment containing the respective mutated genes. pTS1601 (YEp-KRI1) isolated from the YEp13 library contained a 10-kb insert. Subcloning experiments revealed that the 3.3-kb SacII-XbaI fragment containing only KRI1 had the ability to suppress krr1.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Straina | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATaade2-1 ura3-1 trp1-1 leu2-3, 112 his3-11, 15 can1-100 ssd1-d2 |

| W303 | Homozygous diploid derived from W303-1A |

| YTS029-4A | MATakrr1::KRR1::5HA-TRP1 |

| YTS039 | MATa/α KRR1/krr1::URA3 |

| YTS040 | MATa/α KRR1/krr1::HIS3 |

| YTS047 | MATα krr1::HIS3 pTS1019 (YCp-Pgal-KRR1) |

| YTS055 | MATα krr1::HIS3 pTS1010 (YCp-KRR1-TRP1) |

| YTS076 | MATakri1::KRI1::2HA-LEU2 |

| YTS077 | MATakri1::KRI1::9myc-LEU2 |

| YTS084 | krr1::HIS3 kri1::KRI1 ::9myc-LEU2 pTS1010 (YCp-KRR1) |

| YTS085 | krr1::HIS3 kri1::KRI1::9myc-LEU2 pTS1013 (YCp-KRR1::2HA) |

| YTS089 | krr1::HIS3 kri1::KRI1::9myc-LEU2 pTS1053-17 (YCp-krr1-17::2HA) |

| YTS090 | krr1::HIS3 kri1::KRI1::9myc-LEU2 pTS1053-18 (YCp-krr1-18::2HA) |

| YTS094 | MATα krr1::HIS3 pTS1010-17 (YCp-krr1-17) |

| YTS095 | MATα krr1::HIS3 pTS1010-18 (YCp-krr1-18) |

| YTS097A | MATakri1::Pgal-KRI1-URA 3 |

| YTS100 | MATa/α KRI1/kri1::HIS3 |

All of the YTS strains are derivatives of W303.

Construction of temperature-sensitive krr1 mutants.

To disrupt one of the KRR1 genes of the diploid strain W303, we first constructed plasmid pTS1017 by replacing the 578-bp HpaI (−61)-NcoI (+518) (ATG of the start codon of KRR1 is numbered as +1) fragment of pTS1010 with the 1.2-kb SmaI-PvuII fragment carrying URA3. Plasmid pTS1017 was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and introduced into strain W303 to generate strain YTS039. To change the selective marker, we replaced URA3 with HIS3 to generate YTS040. Plasmid pTS1019 (YCp-Pga1-KRR1-URA3) was introduced into YTS040, and Ura+ transformants were sporulated and dissected on galactose medium. This strain YTS047 (Δkrr1 YCp-Pgal-KRR1-URA3) showed galactose-dependent growth. Both mutagenized PCR products of the KRR1 ORF and the cleavage products of the plasmid pTS1010 (YCp-KRR1-TRP1) with HpaI (−61) and MluI (+1159) were cotransformed into YTS047, to clone the mutagenized PCR products into the YCp-TRP1 plasmid by the gap repair method. Ura+ Trp+ transformants, which could grow on glucose medium at 25°C, were screened for those which failed to form colonies at 37°C. Out of 3,220 colonies, 60 failed to grow at 37°C. Plasmids were isolated, and the temperature-sensitive phenotype was confirmed by reintroducing them into strain YTS047.

Deletion of KRI1.

Plasmid pTS1620 was constructed such that HIS3 was inserted between nucleotides +312 and +758 of the KRI1 ORF. The plasmid was cut with EcoRI and ScaI, and the DNA fragment was introduced into W303 to disrupt one of the KRI1 genes. Correct disruption was confirmed by PCR. The resulting heterozygous diploid is YTS100.

Construction of a strain expressing KRI1 from the GAL1 promoter.

The DNA fragment from +1 to +623 of the KRI1 ORF was cloned into pTS911IU, a YIp-type plasmid constructed by deleting the SpeI-BglII fragment of CEN4 and ARS1 from YCplac33 (7) and by inserting the GAL1 promoter to express a gene of interest in a galactose-dependent manner. The resulting plasmid (pTS1613) was cleaved at the BamHI site (+312) and integrated into the chromosomal KRI1 locus in haploid strain W303-1A to generate YTS097A. When the liquid culture of YTS097A was transferred to glucose medium to shut off expression of the KRI1 gene, growth was impaired at 20 h after the shift, judging from the optical density at 600 nm.

Construction of a strain carrying a tagged KRI1.

The DNA fragment containing the C-terminal region of KRI1 (+328 to +773) was amplified by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into pTS906IL and pTS904IL. These are YIp-type plasmids constructed by deleting the SpeI-BglII fragment containing CEN4 and ARS1 from YCplac111 to fuse the 3′ end of a gene of interest to codons for a double-HA tag and nine copies of a myc epitope tag, respectively. The resulting plasmids were cleaved at the unique PstI site (+758) and integrated into the chromosomal KRI1 locus to generate YTS076 and YTS077. Correct integration was confirmed by PCR and Western blot analysis. Both strains grew like wild-type strains (data not shown). Thus both tagged KRI1 genes are functional.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (11, 19).

Fractionation of ribosomes.

Ribosomal patterns were analyzed according to the method of Baim et al. (2). Cells were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium to mid-log phase (optical density at 660 nm, 1.0 to 1.5) and collected. Cell lysates were prepared and centrifuged through a sucrose density gradient (7 to 47%) at 20,000 rpm for 12 h at 4°C for a polysome profile or at 24,000 rpm for 16 h at 4°C for free subunits in a Beckman SW41 rotor. Absorbance at 254 nm was measured.

Analysis of pre-rRNA processing.

For pulse-chase analysis, cultured cells were concentrated in 1 ml of synthetic dextrose (SD) medium, labeled for 2 min with 100 μCi of [methyl-3H]methionine, and chased by adding cold methionine (5 mM), as described previously (10). At each time point, samples were taken, centrifuged, and frozen in liquid N2. Techniques of RNA extraction, gel electrophoresis, blotting, and exposure to X-ray films were performed as described previously (14).

Northern hybridization was performed as described previously (5). Total RNA was isolated by the hot-phenol method (9). Five micrograms of total RNA was resolved through 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis, and the RNA was transferred onto Zeta-Probe membrane (Bio-Rad). The blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled oligodeoxyribonucleotide probes overnight at 37°C in 5× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7])–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The membranes were washed twice with 5× SSPE–0.1% SDS at 37°C for 15 min each and once in 1× SSPE–0.1% SDS for 15 min. Oligonucleotides were those described previously (3).

Immunoprecipitation experiments.

Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (30) with some modifications. Cells expressing KRR1 or KRR1-2HA, KRI1-9myc, and NOP1-GFP were grown to log phase and broken in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 μg of antipain per ml, 1 μg of pepstatin per ml, and 2 μg of aprotinin per ml). After centrifugation (10 min; 13,000 × g), 1 ml of binding buffer (extraction buffer containing 5 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml) was added to the extracts (600 μg of proteins), followed by incubation with 100 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) for 30 min. After brief centrifugation, supernatants were further incubated with 2 μl of anti-HA antibody (16B12; Promega) for 30 min and with 100 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads for 30 min. Beads were washed twice with 1 ml each of washing buffers B50, B100, and B125 (binding buffer containing different concentrations of NaCl [indicated by numbers] in millimolar) for 10 min by end-over-end rotation. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and detected by immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Isolation of KRR1 and its temperature-sensitive mutants.

TOM1 encodes a putative ubiquitin ligase (28). We isolated KRR1 by two-hybrid screening, using TOM1 as bait. KRR1 is an essential and highly conserved gene among eukaryotes (8).

To explore the functions of KRR1, we constructed temperature-sensitive mutants by PCR mutagenesis, as described in Materials and Methods. We isolated 18 temperature-sensitive krr1 mutants; all of the mutations were recessive to the wild type. Two mutants, YTS094 (krr1-17) and YTS095 (krr1-18), were selected for further analysis. Both mutants grew normally at 25°C (data not shown) but failed to grow at 35°C (Fig. 1A). Sequence analysis revealed that the krr1-17 mutant contains four point mutations, K20E, K66N, C162R, and D261A, and the krr1-18 mutant has three point mutations, F45L, L95S, and R207G.

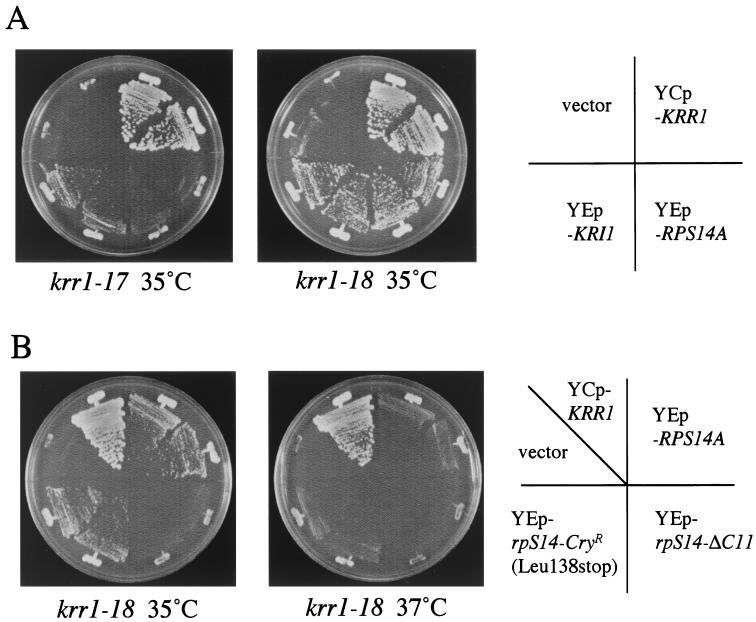

FIG. 1.

A high dose of RPS14A or KRI1 suppresses the temperature sensitivity of krr1 mutants. (A) A plasmid YEplac181 (YEp-vector), pTS1034 (YCp-KRR1), pTS1501 (YEp-RPS14A), or pTS1601 (YEp-KRI1) was introduced into the krr1 mutant strains YTS094 (krr1-17) and YTS095 (krr1-18). Transformants were streaked on SD-Leu medium which was incubated at 35°C for 3 days. (B) The strain YTS095 (krr1-18) harboring YEplac181 (YEp-vector), pTS1034 (YCp-KRR1), pTS1501 (YEp-RPS14A), pTS1506 (YEp-rpS14-ΔC11), or pTS1508 (rpS14-CryR) was streaked on SD-Leu medium which was incubated at 35 or 37°C for 3 days.

RPS14A is a high-dosage suppressor of krr1.

To acquire information about the functions of Krr1p, we screened high-dosage suppressors of the krr1 mutant. A yeast genomic library constructed on multicopy vector YEp13 was introduced into strain YTS095 (krr1-18). Two plasmids, pTS1501 and pTS1601, were isolated. As described in Materials and Methods, subcloning and sequencing experiments revealed that one of the multicopy suppressors was RPS14A encoding a 40S ribosomal protein (6). A high dose of RPS14A suppressed the temperature sensitivity of krr1-18 at 35°C (Fig. 1A) but not at 37°C (Fig. 1B). It did not suppress krr1-17 at 35°C (Fig. 1A) or the lethality of the krr1-null mutant (data not shown).

It has been reported that a deletion of the last amino acid in the C terminus of rpS14p confers cryptopleurine resistance (CryR) and increases rpS14p RNA-binding activity by twofold, while a deletion of 11 amino acids of the C terminus interrupts binding to 18S rRNA and its own mRNA, thereby leading to inability to assemble into the mature 40S ribosome subunit (6, 16, 18). We constructed the same kinds of mutants; one contained the CryR mutation (rpS14-CryR; Leu138stop), and the other had an 11-amino-acid truncation (rpS14-ΔC11). A multicopy plasmid containing rpS14-CryR (pTS1508) suppressed krr1-18 at 35°C (Fig. 1B). However, a multicopy plasmid carrying rpS14-ΔC11 (pTS1506) failed to suppress even at 35°C (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that the fully functional rpS14p is required for the suppression of the temperature sensitivity of the krr1-18 mutant.

The other multicopy suppressor, KRI1, is a novel essential gene.

As described in Materials and Methods, subcloning experiments with pTS1601 revealed that a novel gene, KRI1 (for KRR1-interacting protein 1; YNL308c), was a multicopy suppressor of the krr1-18 mutant (Fig. 1A). It suppressed the temperature sensitivity of the krr1-17 mutant at 35°C (Fig. 1A) but failed to rescue the lethality of the krr1 disruptant (data not shown). The predicted Kri1p is a very hydrophilic protein with a molecular mass of 69 kDa and has 30.0% identical amino acids to its homologue found in Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

We disrupted one of the KRI1 genes of the wild-type diploid strain (W303) by replacing the ORF with the HIS3 marker, as described in Materials and Methods. A heterozygous diploid strain (YTS100; KRI1/kri1::HIS3) was sporulated, and the tetrads were dissected on a YPD plate (Fig. 2A). Two clones from each ascus were viable, all of which were His−. Microscopic observation revealed that cells harboring the kri1::HIS3-null allele progressed a few cell cycles, since several but less than 10 large budded cells were observed (data not shown). Thus we conclude that KRI1 is essential for cell viability.

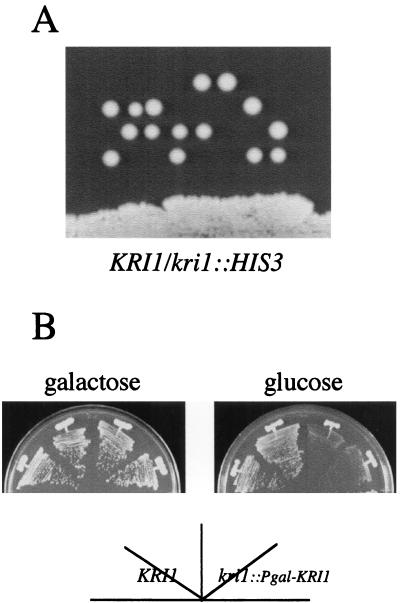

FIG. 2.

The novel gene KRI1 is essential. (A) KRI1 is essential for viability. A heterozygous diploid strain, YTS100 (KRI1/kri1::HIS3) was sporulated, and the tetrads were dissected on a YPD plate, which was incubated at 25°C for 4 days. (B) The effect of depletion of Kri1p. Strains YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) and W303-1A (KRI1) were streaked on galactose or glucose medium and incubated at 25°C for 3 or 2 days, respectively.

To create a conditional kri1 mutant, the N-terminal region of the KRI1 ORF was cloned under the control of the GAL1 promoter. The resulting plasmid, pTS1613 (YIp-Pgal1-KRI1-URA3), was integrated into the chromosomal KRI1 locus by homologous recombination. Strain YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) grew normally on galactose medium, but it did not grow on glucose (Fig. 2B).

Kri1p as well as Krr1p is localized to the nucleolus.

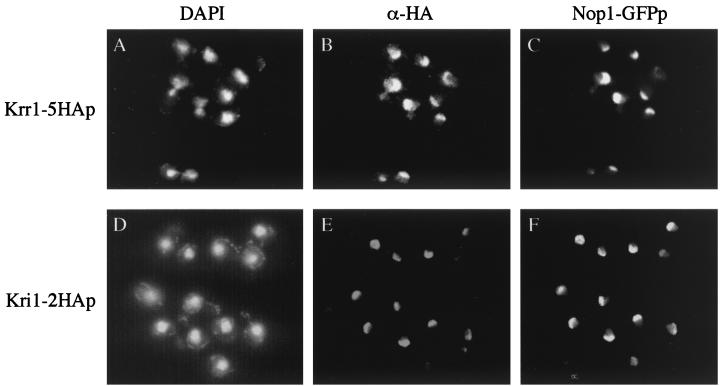

Although a large-scale analysis of protein localization revealed that Krr1p was localized to the nucleolus, this assay used a Krr1–β-galactosidase fusion protein which was not confirmed to be functional (4). Furthermore, another group reported that localization of HA-tagged Krr1p was at the nuclear rim (20). To clarify this discrepancy, we constructed a haploid strain (YTS029-4A) expressing an HA-tagged Krr1p as the only source of cellular Krr1p, as described in Materials and Methods. This strain grew normally as did wild-type cells (data not shown), indicating that the tagged Krr1p was functional. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy showed that Krr1-HAp was localized to the nucleolus, because it showed a caplike or crescent shape and colocalized with GFP-tagged Nop1p, a nucleolar marker protein (1, 23, 27) (Fig. 3A to C). We conclude that Krr1p is a nucleolar protein, as previously reported (4).

FIG. 3.

Krr1p and Kri1p are nucleolar proteins. Strain YTS029-4A (Krr1-5HAp) or YTS076 (Kri1-2HAp), each harboring pTS068 to express Nop1-GFPp, was stained with anti-HA antibody and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (B, Krr1-HAp; E, Kri1-HAp). Nop1-GFPp was used as a nucleolar marker (C and F). DNA was detected by 4′, 6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (A and D).

To decide the localization of Kri1p, we constructed strain YTS076, which expressed an HA-tagged Kri1p as the only source of Kri1p, as described in Materials and Methods. This strain grew normally, indicating that the tagged Kri1p was functional (data not shown). Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that the HA-tagged Kri1p showed a crescent shape and colocalized with the GFP-tagged Nop1p (Fig. 3D to F). Thus we conclude that Kri1p is also a nucleolar protein.

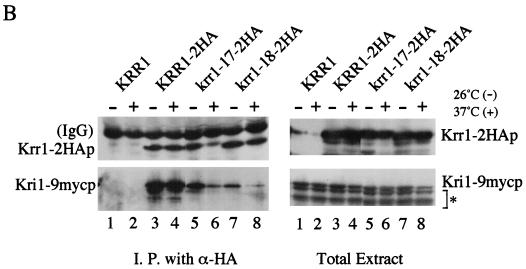

Both KRR1 and KRI1 are required for formation of 40S ribosome subunits.

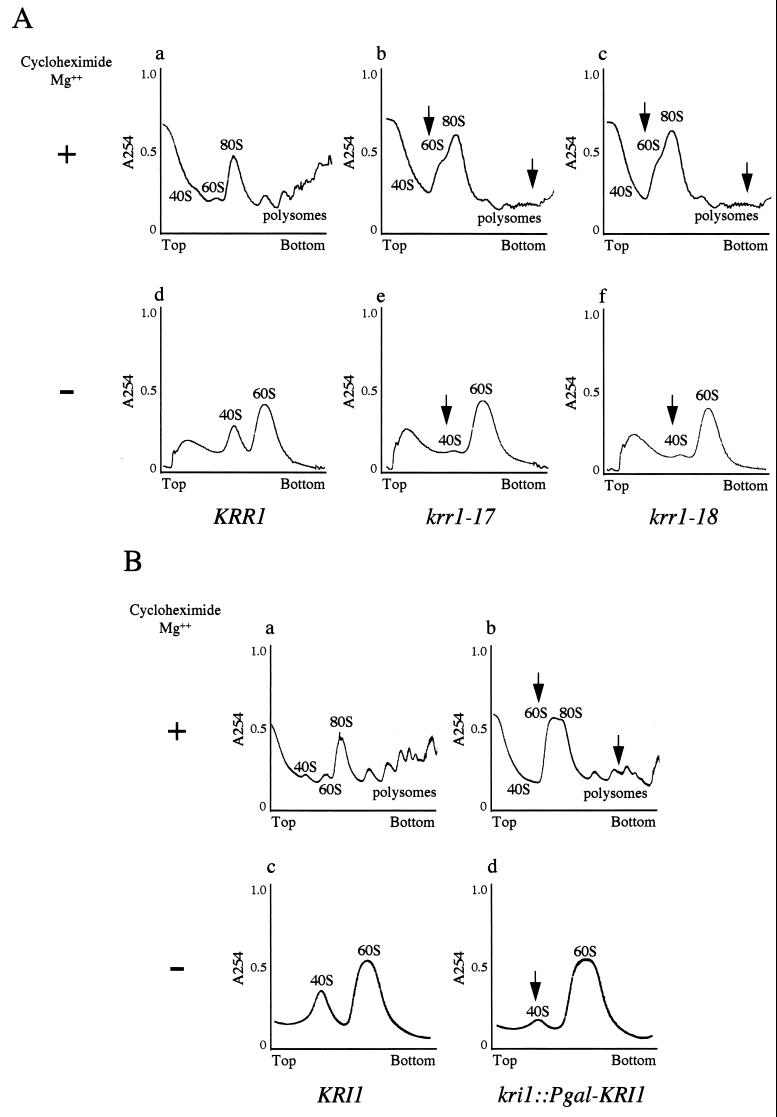

To address whether Krr1p and Kri1p were involved in ribosome synthesis, we examined ribosomal profiles of those mutant lysates by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Cells of strain YTS055 (KRR1), YTS094 (krr1-17), or YTS095 (krr1-18) were grown to mid-log phase at 25°C, and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Polysome fractions severely decreased, and free 60S ribosome subunits accumulated in either mutant (Fig. 4A, charts b and c), compared to the wild type (Fig. 4A, chart a).

FIG. 4.

The level of 40S ribosome subunits decreases in both krr1 and kri1 mutants under the restrictive conditions. (A) Cultures of YTS055 (KRR1 [a and d]), temperature-sensitive krr1 mutant YTS094 (krr1-17 [b and e]), and YTS095 (krr1-18 [c and f]) were grown at 37°C for 6 h. The cell lysates were prepared with (+ [a, b, and c]) or without (− [d, e, and f]) cycloheximide and Mg2+ and were centrifuged through 7 to 47% sucrose density gradients. (B) The wild-type strain W303-1A (KRI1 [a and c]) and the glucose-repressible kri1 strain YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1 [b and d]) were transferred to glucose medium and grown at 25°C for 24 h. Extracts were prepared and analyzed as described for panel A. Arrows indicate aberrant patterns observed in the krr1 and kri1 mutants.

To examine the polysome profile of the Kri1p-depleted cells, cultures of YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) and W303-1A (wild type) were grown to mid-log phase in galactose medium at 25°C, transferred to glucose medium, and incubated at 25°C for 24 h. Again the polysome fractions of the mutant severely decreased, and free 60S ribosome subunits increased (Fig. 4B, chart b), compared to the wild-type cells (Fig. 4B, chart a).

Next the lysates were prepared without magnesium, and the amounts of free 40S and 60S ribosome subunits were analyzed. The level of 40S ribosome subunits severely decreased in both the krr1 mutant and Kri1p-depleted cells. In contrast, the peak of 60S subunits was as high as that in the wild-type cells (Fig. 4A, charts d through f and 4B, charts c and d). Taking the data together, we conclude that both KRR1 and KRI1 are required for the synthesis of 40S ribosome subunits.

The processing of pre-rRNAs for 18S rRNA is impaired in both krr1 and kri1 mutants.

To determine whether Krr1p and Kri1p were involved in pre-rRNA processing, we performed pulse-chase labeling of rRNAs. Cells of YTS055 (KRR1), YTS094 (krr1-17), or YTS095 (krr1-18) were grown at 37°C for 4 h, and the newly synthesized rRNAs were labeled with [methyl-3H]methionine for 2 min and chased by adding cold methionine. Neither 20S pre-rRNA nor 18S rRNA were produced, even at the 10-min chase time point in the krr1 mutants (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 through 9). In contrast, 25S rRNA was produced in the mutants, although the appearance of 25S rRNA was slightly slower in the mutants than in the wild type (Fig. 5A, lanes 2, 5, and 8). Consistent with this, little 27S pre-rRNA was made during the 2-min pulse in the mutants (Fig. 5A, lanes 4 and 7), and the processing of 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs was slightly delayed, since a small amount of 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs remained at the 5-min chase time point (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 and 8).

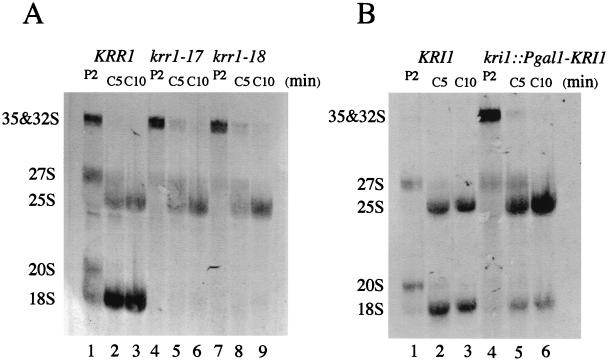

FIG. 5.

Both Krr1p and Kri1p are required for the synthesis of 18S rRNA. (A) Cultures of YTS055 (KRR1), YTS094 (krr1-17), and YTS095 (krr1-18) were grown in SD medium without methionine at 37°C for 4 h. Cells were pulse-labeled for 2 min with [methyl-3H]methionine (P2), which was chased for 5 min (C5) or 10 min (C10) with an excess of cold methionine. A total of 60,000 cpm was loaded on each lane. (B) Wild-type strain W303-1A (KRI1) and the glucose-repressible kri1 strain YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) were grown in glucose medium at 25°C for 24 h. Cells were pulse-labeled and chased as described for panel A. A total of 30,000 cpm (KRI1) or 240,000 cpm (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) was loaded on each lane.

Similar results were obtained when cells of YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) were grown in glucose medium at 25°C for 24 h (Fig. 5B). Compared to the level of 25S rRNA, little 18S rRNA was made in Kri1p-depleted cells (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 6). The 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs were prominent during the 2-min pulse period (Fig. 5B, lane 4). In contrast, the appearance of 25S rRNA was not significantly affected.

Next, the steady-state level of rRNAs was examined. Cells of YTS055 (KRR1), YTS094 (krr1-17), and YTS095 (krr1-18) were grown at 25 or 37°C for 4 h, and RNA was prepared and electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose–formaldehyde gel. The level of 18S rRNA was reduced in either mutant under the restrictive condition (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 6), whereas the level of 25S rRNA remained constant. Cells of YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1) and the wild-type W303-1A were grown in glucose medium at 25°C for 24 h, and the level of 18S rRNA was also reduced in the Kri1p-depleted cells (data not shown).

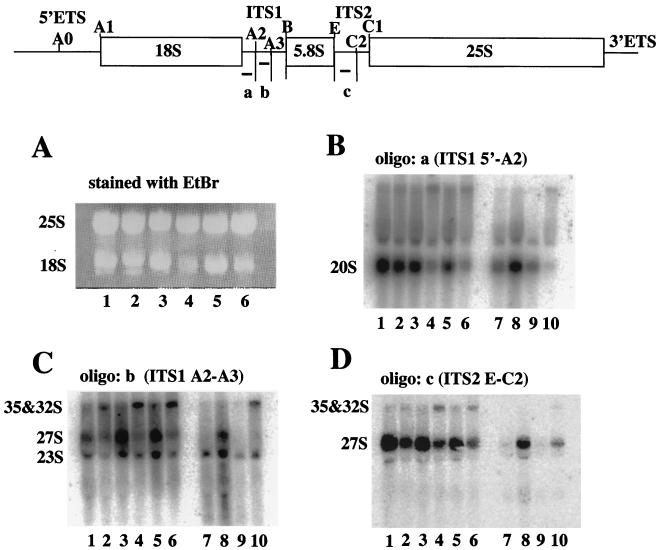

FIG. 6.

The steady-state level of rRNAs in both krr1 and kri1 mutants. (A through D) Cultures of YTS055 (KRR1; lanes 1 and 2), YTS094 (krr1-17; lanes 3 and 4) and YTS095 (krr1-18; lanes 5 and 6) were grown at 25°C (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or 37°C (lanes 2, 4, and 6) for 4 h. (A) RNA was prepared and electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose–formaldehyde gel which was stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr). (B through D) For a Kri1p-depletion experiment, W303-1A (KRI1; lanes 7 and 8) and the glucose-repressible kri1 strain YTS097A (kri1::Pgal-KRI1; lanes 9 and 10) were grown in galactose (lanes 7 and 9) or glucose medium (lanes 8 and 10) at 25°C for 24 h. The agarose gels were subjected to Northern blotting, using oligonucleotides complementary to ITS1 5′-A2 (oligo a) (B), ITS1 A2–A3 (oligo b) (C), and ITS2 E-C2 (oligo c) (D). The positions of various rRNAs are indicated.

When the RNA samples were subjected to Northern blotting by using 32P-labeled oligonucleotide a (ITS1 5′-A2), the level of 20S pre-rRNA was reduced in the krr1 mutants grown at high temperature (Fig. 6B, lanes 4 and 6) and in the Kri1p-depleted cells (Fig. 6B, lane 10), which is consistent with the results of the pulse-chase experiment.

Most mutants defective in 40S ribosomal biosynthesis are blocked in processing at sites A0, A1, and A2 but not at the A3, B, and C sites (Fig. 6, top). Such mutants accumulate the 23S and 27SA3 pre-rRNAs as well as the 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs (3, 5, 13, 17, 29). To clarify this, we performed Northern blotting using oligonucleotide b (ITS1 A2–A3). 23S and 27S pre-rRNAs were detected in the krr1 mutants grown at the permissive temperature (Fig. 6C, lanes 3 and 5), suggesting that the processing occurred at both the A2 and A3-B sites. At the restrictive temperature, however, 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs were prominent in the krr1 mutants (Fig. 6C, lanes 4 and 6). In Kri1p-depleted cells, the 23S pre-rRNA and 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs were accumulated (Fig. 6C, lane 10), suggesting that the processing at the A2 site was impaired.

When oligonucleotide c (ITS2 E-C2) was used, the 27S pre-rRNA and small amounts of 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs were detected in the krr1 mutants and Kri1p-depleted cells (Fig. 6D, lanes 4, 6, and 10). Taking the data together, we conclude that the processing of pre-rRNAs especially for 18S rRNA is impaired in both the krr1 and kri1 mutants.

Krr1p forms a complex with Kri1p.

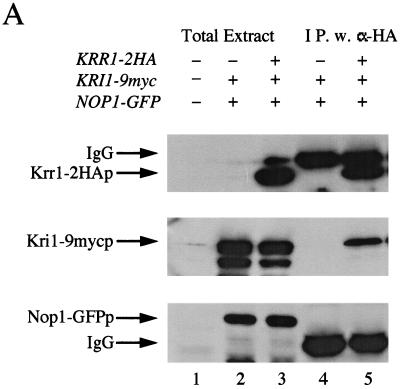

To see a physical interaction of Krr1p with Kri1p, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed. We constructed strains of YTS084 expressing Krr1p and a myc-tagged Kri1p (Kri1-mycp) and YTS085 expressing the HA-tagged Krr1p (Krr1-HAp) and Kri1-mycp. Both tagged genes were functional, as described in Materials and Methods. These strains were transformed with plasmid pTS068 expressing a GFP-tagged Nop1p. The lysates were prepared, and anti-HA antibody was added for immunoprecipitation. As shown in Fig. 7A (lane 5), Kri1-mycp was coimmunoprecipitated with Krr1-HAp. Furthermore, Nop1-GFPp was not coprecipitated with Krr1-HAp.

FIG. 7.

Association of Krr1p with Kri1p in vivo. (A) Strains of W303-1A (Krr1p and Kri1p; lane 1), YTS084 (Krr1p and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 2 and 4) containing pTS068 (Nop1p-GFP) and YTS085 (Krr1-2HAp and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 3 and 5) harboring pTS068 (Nop1p-GFP) were grown at 26°C to mid-log phase. The cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and the bound proteins were subjected to Western blotting with anti-HA, anti-myc, or anti-GFP antibody. + or − signifies the presence or absence, respectively, of the indicated tagged proteins. (B) The mutant Krr1p impaired the association with Kri1p. Cultures of YTS084 (Krr1p and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 1 and 2), YTS085 (Krr1-2HAp and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 3 and 4), YTS089 (Krr1-17-2HAp and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 5 and 6) and YTS090 (Krr1-18-2HAp and Kri1-9mycp; lanes 7 and 8) were grown at 26°C (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or 37°C (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) for 4 h. Immunoprecipitation was performed as described in panel A. Breakdown products of Kri1-9mycp are indicated by a bracket with an asterisk.

Next we constructed plasmids expressing HA-tagged krr1 mutant proteins, as described in Materials and Methods. Cells of strains YTS084 (Krr1p, Kri1-mycp), YTS085 (Krr1-HAp, Kri1-mycp), YTS089 (krr1-17-HAp, Kri1-mycp), and YTS090 (krr1-18-HAp, Kri1-mycp) were grown at either 26 or 37°C. The same kind of immunoprecipitation was performed as shown in Fig. 7A. A similar amount of each HA-tagged Krr1 protein was precipitated with anti-HA antibody, except that krr1-17-HAp was prepared at 37°C (Fig. 7B, lane 6). Very reduced amounts of Kri1p were coimmunoprecipitated with the krr1 mutant proteins, even when the cultures were grown at the permissive temperature (Fig. 7B, lanes 5 through 8). Thus the krr1-18 mutant protein is defective in binding to Kri1p, and the krr1-17 mutant protein seems to be unstable.

DISCUSSION

KRR1 encodes a protein that is evolutionarily conserved among yeast, nematode, fly, rice, and human cells (8). The novel KRI1 gene isolated as a multicopy suppressor of the temperature-sensitive krr1 mutants (Fig. 1A) also seems to be a conserved gene among eukaryotes, since there are homologues in fission yeast, nematode, and fly cells. Both genes are indispensable for cell growth (Fig. 2A) (8), and the products are localized to the nucleolus (Fig. 3). These results suggest that Krr1p and Kri1p play essential roles in nucleolar functions which are common in eukaryotes.

The present analysis of the temperature-sensitive krr1 mutants revealed that Krr1p was required for biogenesis of 40S ribosome subunits, but it was dispensable for the synthesis of 60S ribosome subunits. The same phenotype was also found in Kri1p-depleted cells. Consistent with the data of the ribosomal profiles (Fig. 4), the production of 18S rRNA and 20S pre-rRNA was considerably reduced in both krr1 and kri1 mutants in the pulse-chase and Northern blotting experiments (Fig. 5 and 6).

In mutants defective in 40S ribosomal biosynthesis such as rrp7, mpp10, fal1, rok1, imp3, and imp4 mutants, the 23S and 27SA3, as well as 35S and 32S, pre-rRNAs are accumulated (3, 5, 13, 17, 29). The 23S pre-rRNA is the cleavage product at the A3 site without cleavage at A0, A1, and A2. Likewise, the cleavage at the A2 site seems to be impaired in the Kri1p-depleted cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, both 23S (A3-B-product) and 27S (A2-product) pre-rRNAs were hybridized with the A2-A3 probe in the krr1 mutants at the permissive temperature. At the high temperature, however, the 35S and 32S pre-rRNAs were accumulated (Fig. 6). Taken together, these data suggest that the precursors for 18S rRNA are very unstable in the krr1 mutants, which is consistent with the result of pulse-chase experiment (Fig. 5).

To obtain a multicopy suppressor of the krr1 mutant, we isolated RPS14A, encoding one of the 40S ribosomal proteins (Fig. 1). The C terminus of rpS14p, which is essential for binding to 18S rRNA (6), was also required to suppress krr1. These results suggest that the primary defect of the krr1 mutant is a failure in the assembly of the 43S preribosome in the nucleolus and that an excess amount of rpS14p rescued the defect by facilitating the assembly of the 43S preribosome through its binding to the precursors of 18S rRNA. This may be similar to Rrp7p, since the depletion of Rrp7p leads to a reduction of 18S rRNA synthesis and the lethality of rrp7 deletion is suppressed by overproduction of rpS27A or B that assembles late into the pre-40S ribosomal particles (3). It has been suggested that Rrp7p is required for the correct assembly of rpS27A/Bp into pre-40S ribosomal particles.

Overexpression of KRI1 partially rescued the defect of the krr1 mutant (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 7, Kri1p and Krr1p form a complex, which is different from the Nop1p-containing snoRNP. Furthermore, Kri1p was poorly associated with the mutant Krr1p. These results suggest that the Krr1p-Kri1p association is crucial for their functions.

Krr1p contains a putative KH domain, a conserved RNA-binding motif, which was first found as repeated sequences in hnRNP K and then in several other proteins (25, 26). Krr1p may be bound to the precursors of 18S rRNA or snoRNAs through its KH domain to facilitate the assembly of the 43S preribosome subunit.

As well as the two-hybrid interaction between Tom1p and Krr1p, KRR1 and TOM1 interact genetically, since overexpression of KRR1 severely inhibited the growth of the tom1 mutant at permissive temperatures (T. Sasaki, A. Toh-e, and Y. Kikuchi, unpublished results). Tom1p must be involved in some nucleolar functions, because the arrested cells of the tom1 mutant exhibit nucleolar fragmentation and NPI46 encoding a nucleolar protein is a potent multicopy suppressor of the tom1 mutant (28). Furthermore, in collaboration with S. Ellis, we have recently found that ribosome biogenesis is impaired in the tom1 mutant (A. Tabb, T. Utsugi, C. Wooten, T. Sasaki, S. Edling, W. Gump, Y. Kikuchi, and S. Ellis, unpublished data).

From these results, we expected that Krr1p might be a substrate of Tom1p-ubiquitin ligase. However, we have not found any evidence that Krr1p is ubiquitinated in a Tom1p-dependent way. Further work is needed to clarify the nature of the interaction between Tom1p and the nucleolar proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Ohya for the DNA bank and S. Ellis of The University of Louisville and K. Mizuta of Hiroshima University for technical suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture to Y.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aris J P, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:17–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baim S B, Pietras D F, Eustice D C, Sherman F. A mutation allowing an mRNA secondary structure diminishes translation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae iso-1-cytochrome c. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1839–1846. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.8.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baudin-Baillieu A, Tollervey D, Cullin C, Lacroute F. Functional analysis of Rrp7p, an essential yeast protein involved in pre-rRNA processing and ribosome assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5023–5032. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-Macdonald P B, Choi E Y, Finberg K, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunbar D A, Wormsley S, Agentis T M, Baserga S J. Mpp10p, a U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein component required for pre-18S rRNA processing in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5803–5812. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fewell S W, Woolford J L., Jr Ribosomal protein S14 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae regulates its expression by binding to RPS14B pre-mRNA and to 18S rRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:826–834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gromadka R, Kaniak A, Slonimski P P, Rytka J. A novel cross-phylum family of proteins comprises a KRR1 (YCL059c) gene which is essential for viability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Gene. 1996;171:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie C, Fink G R. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:1–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong B, Brockenbrough J S, Wu P, Aris J P. Nop2p is required for pre-rRNA processing and 60S ribosome subunit synthesis in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:378–388. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagami M, Toh-e A, Matsui Y. Sro7p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae counterpart of the tumor suppressor 1(2)gl protein, is related to myosins in function. Genetics. 1998;149:1717–1727. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.4.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser C, Michaelis S, Mitchell A. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kressler D, de la Cruz J, Rojo M, Linder P. Fal1p is an essential DEAD-box protein involved in 40S-ribosomal-subunit biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7283–7294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kressler D, de la Cruz J, Rojo M, Linder P. Dbp6p is an essential putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase required for 60S-ribosomal-subunit assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1855–1865. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kressler D, Linder P, de la Cruz J. Protein trans-acting factors involved in ribosome biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7897–7912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.7897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larkin J C, Woolford J L. Molecular cloning and analysis of the CRY1 gene: a yeast ribosomal protein gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:403–420. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S J, Baserga S J. Imp3p and Imp4p, two specific components of the U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein that are essential for pre-18S rRNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5441–5452. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulovich A G, Thompson J R, Larkin J C, Li Z, Woolford J L., Jr Molecular genetics of cryptopleurine resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: expression of a ribosomal protein gene family. Genetics. 1993;135:719–730. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.3.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pringle J R, Preston R A, Adams A E, Stearns T, Drubin D G, Haarer B K, Jones E W. Fluorescence microscopy methods for yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1989;31:357–435. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61620-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rout M P, Aitchison J D, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait B T. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki T, Toh-e A, Kikuchi Y. Extragenic suppressors that rescue defects in the heat stress response of the budding yeast mutant tom1. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;262:940–948. doi: 10.1007/pl00008662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schimmang T, Tollervey D, Kern H, Frank R, Hurt E C. A yeast nucleolar protein related to mammalian fibrillarin is associated with small nucleolar RNA and is essential for viability. EMBO J. 1989;8:4015–4024. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siomi H, Matunis M J, Michael W M, Dreyfuss G. The pre-mRNA binding K protein contains a novel evolutionarily conserved motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1193–1198. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siomi H, Choi M, Siomi M C, Nussbaum R L, Dreyfuss G. Essential role for KH domains in RNA binding: impaired RNA binding by a mutation in the KH domain of FMR1 that causes fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1994;77:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tollervey D, Lehtonen H, Carmo-Fonseca M, Hurt E C. The small nucleolar RNP protein NOP1 (fibrillarin) is required for pre-rRNA processing in yeast. EMBO J. 1991;10:573–583. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utsugi T, Hirata A, Sekiguchi Y, Sasaki T, Toh-e A, Kikuchi Y. Yeast tom1 mutant exhibits pleiotropic defects in nuclear division, maintenance of nuclear structure and nucleocytoplasmic transport at high temperatures. Gene. 1999;234:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venema J, Bousquet-Antonelli C, Gelugne J P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Tollervey D. Rok1p is a putative RNA helicase required for rRNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3398–3407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zachariae W, Shevchenko A, Andrews P D, Ciosk R, Galova M, Stark M J, Mann M, Nasmyth K. Mass spectrometric analysis of the anaphase-promoting complex from yeast: identification of a subunit related to cullins. Science. 1998;279:1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]