Abstract

This economic evaluation examines whether adult patients in the US who have commercial or Medicare insurance pay out-of-pocket costs associated with follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months of a noninvasive stool-based test.

Introduction

The ability of screening to decrease colorectal cancer morbidity and mortality has been established.1,2 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires several colorectal cancer screening modalities, including colonoscopy and noninvasive stool-based tests (SBTs), be covered with no consumer cost sharing for individuals with an average cancer risk who are eligible for such screening on the basis of age. Although colorectal cancer screening recommendations state that results of noninvasive SBTs that are positive for colorectal cancer require a subsequent colonoscopy to receive screening benefit, patients may still incur out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for follow-up colonoscopies.3 Therefore, cost barriers may remain for individuals who defer colorectal cancer screening or may present financial hardship for those who require follow-up care. The objective of this analysis was to describe OOP costs for colonoscopy within 6 months after a noninvasive SBT in the US.

Methods

In this economic evaluation, MarketScan Commercial (hereafter commercial) and Medicare Supplemental (hereafter Medicare) administrative claims databases were used to identify individuals (1) who completed a noninvasive SBT from January 1, 2014, through July 31, 2019 (the earliest noninvasive SBT served as the index date) and were continuously enrolled in the database for at least 6 months after the index date; (2) those aged 50 to 75 years at index date; and (3) those with continuous database enrollment for 10 years before the index date (preperiod). This preperiod was used to exclude individuals not due for screening and those with an above-average risk for colorectal cancer. Individuals who underwent colonoscopy within 6 months after the SBT were included in the analysis. Information on race and ethnicity was not collected because the data were not available in the commercial database. Health plan and patient costs for colonoscopy were stratified by whether a polypectomy was performed. Costs associated with colonoscopy were examined in the 30 days before and after the colonoscopy and included colonoscopy, pathology, anesthesia, and prescription bowel preparation costs. All database records are statistically de-identified and certified to be fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study is exempt from institutional review board review in accordance with the Common Rule. We followed relevant portions of the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Results

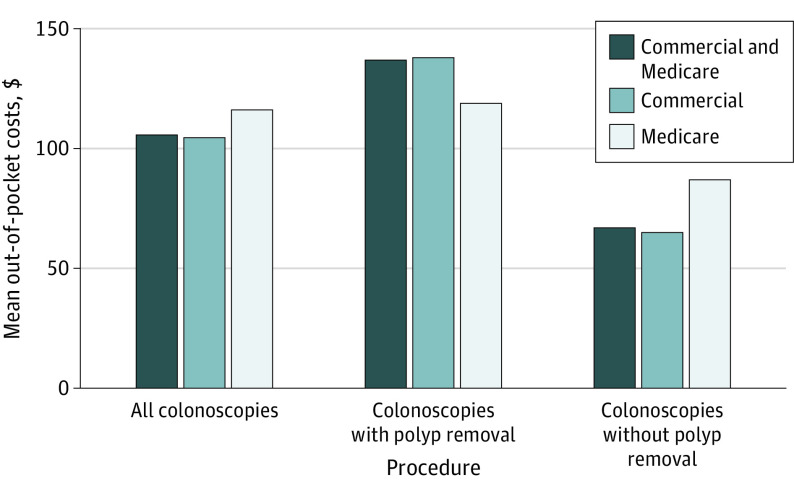

We identified 80 951 patients (74 235 [91.7%] from the commercial claims database and 6716 [8.3%] from the Medicare claims database) who completed a noninvasive SBT. Of these, 12 823 patients (15.8%) underwent subsequent colonoscopy within 6 months, and 7416 (57.8%) with a subsequent colonoscopy had a polypectomy (Table). Consumer cost sharing for colonoscopy after a noninvasive SBT was common (OOP cost>$0 in 48.2% of commercial claims [n = 5790 of 12 023] and 77.9% of Medicare claims [n = 613 of 787]); OOP costs (SD) ranged from $99 ($290) to $231 ($481), depending on the original screening test used (multitarget stool DNA, fecal immunochemical test, or fecal occult blood test) for patients with either commercial or Medicare insurance. The OOP costs were higher when polypectomy was performed (Figure).

Table. Proportion of Patients With Subsequent Colonoscopy in the 6 Months Following SBTa.

| Type of insurance | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | mt-sDNA cohort | FIT cohort | FOBT cohort | |

| Commercial or Medicare insurance | ||||

| Patients with at least 6 mo of CE on or after SBT, No. | 80 951 | 5993 | 50 840 | 24 118 |

| Subsequent colonoscopy within 6 mo after SBT | 12 823 (15.8) | 581 (9.7) | 7753 (15.2) | 4489 (18.6) |

| With polyp removal | 7416 (57.8) | 455 (78.3) | 4433 (57.2) | 2528 (56.3) |

| Without polyp removal | 5608 (43.7) | 145 (25.0) | 3425 (44.2) | 2038 (45.4) |

| Medicare insurance | ||||

| Patients with at least 6 mo of CE on or after SBT, No. | 6716 | 297 | 4207 | 2212 |

| Subsequent colonoscopy within 6 mo after SBT | 788 (11.7) | 36 (12.1) | 509 (12.1) | 243 (11.0) |

| With polyp removal | 544 (69.0) | 23 (63.9) | 340 (66.8) | 181 (74.5) |

| Without polyp removal | 267 (33.9) | 15 (41.7) | 181 (35.6) | 71 (29.2) |

| Commercial insurance | ||||

| Patients with at least 6 mo of CE on or after SBT, No. | 74 235 | 5696 | 46 633 | 21 906 |

| Subsequent colonoscopy within 6 mo after SBT | 12 035 (16.2) | 545 (9.6) | 7244 (15.5) | 4246 (19.4) |

| With polyp removal | 6872 (57.1) | 432 (79.3) | 4093 (56.5) | 2347 (55.3) |

| Without polyp removal | 5341 (44.4) | 130 (23.9) | 3244 (44.8) | 1967 (46.3) |

Abbreviations: CE, continuous enrollment; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; mt-sDNA, multitarget stool DNA; SBT, stool-based tests.

Colonoscopy after an SBT does not indicate a positive SBT result, as screening test results are not available in claims data.

Figure. Mean Out-of-Pocket Costs of Subsequent Colonoscopy in the 6 Months After Stool-Based Test With and Without Polypectomy, Overall and by Payer .

Discussion

Although the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act largely eliminated consumer cost sharing for colorectal cancer screening, for the more than 1 in 6 individuals who had an SBT and underwent colonoscopy within 6 months, OOP costs for colonoscopy were incurred by nearly half of those who were commercially insured and by more than three-quarters of those covered by Medicare in our data set. The findings suggest that among insured individuals, OOP costs for those who undergo colonoscopy after an SBT are common and increase when polypectomy is performed.

These analyses have important limitations. Administrative claims data do not have clinical detail available to indicate if the subsequent colonoscopy was performed because of a positive SBT result, for another indication, or if a patient came back early for screening. In addition, although costs associated with subsequent colonoscopy were examined in the 30 days before the event (to include preparation costs), additional OOP costs attributable to complications are not included, possibly leading to an underestimation of patient contribution. In addition, this study was limited to individuals with commercial health coverage or private Medicare supplemental coverage; therefore, results are not necessarily generalizable to individuals with other insurance or those who are uninsured.

Consumer cost sharing is associated with decreased use of evidence-based medical care and reduction of spending for other essential items (eg, food, rent).4 The level of cost sharing for subsequent colonoscopy could deter individuals from follow-up evaluation after a positive SBT result or add to financial stress for those who receive this preventive health service. As noninvasive SBT screening modalities are preferred by some, and use of these modalities has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (when colorectal cancer screening rates have declined),5 it is important for payer policies to cover all components of screening to avoid discouraging patients from completing the evaluation.

References

- 1.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687-696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1106-1114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan Foundation . Issue brief No. 15: food insecurity among older adults. January 2021. Accessed June 6, 2021. https://www.panfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/02/PAN-Issue-Brief-15.pdf

- 5.McBain RK, Cantor JH, Jena AB, Pera MF, Bravata DM, Whaley CM. Decline and rebound in routine cancer screening rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1829-1831. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06660-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]