Abstract

Cardiac masses diagnosis and treatment are a true challenge, although they are infrequently encountered in clinical practice. They encompass a broad set of lesions that include neoplastic (primary and secondary), non-neoplastic masses and pseudomasses. The clinical presentation of cardiac tumors is highly variable and depends on several factors such as size, location, relation with other structures and mobility. The presumptive diagnosis is made based on a preliminary non-invasive diagnostic work-up due to technical difficulties and risks associated with biopsy, which is still the diagnostic gold standard. The findings should always be interpreted in the clinical context to avoid misdiagnosis, particularly in specific conditions (e.g., infective endocarditis or thrombi). The modern multi-modality imaging techniques has a key role not only for the initial assessment and differential diagnosis but also for management and surveillance of the cardiac masses. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) allows an optimal non-invasive localization of the lesion, providing multiplanar information on its relation to surrounding structures. Moreover, with the additional feature of tissue characterization, CMR can be highly effective to distinguish pseudomasses from masses, as well as benign from malignant lesions, with further differential diagnosis of the latter. Although histopathological assessment is important to make a definitive diagnosis, CMR plays a key role in the diagnosis of suspected cardiac masses with a great impact on patient management. This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of cardiac masses, from clinical and imaging protocol to pathological findings.

Keywords: Cine magnetic resonance imaging, Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, Heart neoplasm, Multimodal imaging, Late-gadolinium enhancement, Early gadolinium enhancement

Core Tip: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) allows an optimal non-invasive localization of cardiac masses by providing multiplanar information on its relation to the surrounding structures. Moreover, CMR can be highly effective to distinguish pseudomasses from masses as well as benign from malignant masses. Although histopathological assessment sometimes has an important role to make a definitive diagnosis, CMR is a key modality in the diagnosis of suspected cardiac masses with a great impact on patient management.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac masses diagnosis and treatment are a true challenge, although they are infrequently encountered in clinical practice[1]. They encompass a broad set of lesions that include both neoplastic (primary and secondary) and non-neoplastic masses (e.g., thrombi, vegetations, pericardial cysts, mitral annulus calcification or caseous necrosis) and pseudomasses (e.g., lipomatous hypertrophy of the atrial septum, coumadin ridge, Chiari network, Eustachian valve, crista terminalis)[2].

Some of those may be considered as anatomical variants, while some others represent variable prognosis; hence an accurate and early diagnosis is required to allow subsequent assessment of treatment strategy.

The most frequent cardiac masses are non-neoplastic or pseudomasses, which are potentially mimicking cardiac tumors. Cardiac thrombi have a prevalence ranging from 2%-7% in patients with atrial fibrillation or left ventricular dysfunction, while infective endocarditis may be found in 0.8%-3% intensive care unit patients[3-5]. Cardiac tumors are rarer (0.15% prevalence in echocardiographic studies) and mostly benign (90% of surgically-removed masses)[6,7]. Cardiac myxoma is the most frequent benign tumor in adults, while rhabdomyoma and fibroma are the most common in children[8]. However, malignant tumors have been reported to be at least 20 times more common in autopsy studies (1.23%)[9,10]. Sarcomas are the most common primary malignant tumors[11]. Among secondary tumors, the most frequently associated extracardiac neoplasms are lung, lymphoma, breast and esophageal cancer[12].

The clinical presentation of cardiac tumors is highly variable and depends on several factors such as size, location, relation to other surrounding structures and mobility[13]. As a consequence, symptoms may range from incidental detection through routine imaging tests in asymptomatic to exertional dyspnea, cardiogenic shock or sudden cardiac death[10]. Signs and symptoms may be non-specific, such as fever and weight loss, or associated with distal embolization of tumor (stroke or peripheral embolization in case of left-sided mass, pulmonary embolism in case of right-sided mass) or due to direct mass effects (obstruction, coronary artery encasement, pericardial effusion with cardiac tamponade, arrhythmia)[14].

Due to technical difficulties and risks associated with biopsy, which is still the diagnostic gold standard, the presumptive diagnosis is based on a preliminary non-invasive diagnostic work-up[10]. The clinical context should always be considered for the diagnostic work-up, particularly in specific conditions (e.g., infective endocarditis or thrombi). The modern multi-modality imaging techniques have a key role not only for the primary assessment and differential diagnosis but also for management and surveillance of the cardiac masses[15]. Among different techniques, two dimensional-echocardiography is the first level diagnostic test, due to its wide availability and low costs[16]. However, echocardiography may be inconclusive due to limited information about the composition of cardiac mass or pericardial/ myocardial infiltration, limited field of view and variable quality of acoustic window[17].

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is an advanced and highly accurate imaging test capable of providing not only accurate tissue characterization of the mass but also multiplanar information on its relation to surrounding structures, with a higher spatial resolution. Perfusion sequences are useful in the assessment of mass vascularization, while early- (EGE) and late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE) sequences are essential to detect the presence of thrombi and to provide further characterization of the mass[18,19]. Indeed CMR may provide reliable information for the differentiation of malignant from benign tumors[20,21].

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of cardiac masses, from exam protocol to pathological findings.

CMR PROTOCOL

A CMR protocol for the study of a suspected cardiac mass should encompass all available sequences for tissue characterization in order to distinguish pseudomasses from cardiac masses (non-neoplastic and neoplastic)[22].

A CMR exam for a suspected cardiac mass can be divided in two parts: The mass localization and its tissue characterization.

The exam should start with an axial steady-state free precession (SSFP) with a balanced T1/T2 effect sequences covering the entire thorax. After that cine-SSFP imaging in long and short axis planes should be performed in order to identify correctly the mass and an additional stack in at least two orthogonal customized imaging planes should be performed to confirm the presence, the location and the extension of the mass (i.e. intracavitary, intracardiac or extracardiac). Moreover cine-SSFP sequences allow the assessment of the mass mobility and its attachment points and the hemodynamic impact on cardiac valves[23]. In case of valve involvement, phase-contrast sequences might be performed for quantitative assessment of the hemodynamic effect of the mass[24].

The next step is tissue characterization utilizing all available sequences. “Black-blood” images may also be used to localize a suspected cardiac mass and to provide some information about its tissue composition. Such sequences are generally acquired using a double-inversion recovery fast spin-echo sequence with an initial non slice-selective 180° inversion pulse followed by a slice-selective 180° pulse; a third slice-selective 180° inversion pulse (triple inversion recovery) can be added to obtain fat saturation, resulting in low intensity of fat containing lesions[25,26].

In particular morphologic T1-weighted and T2-weighted, followed by fat-suppressed imaging, should be performed before contrast administration in the same optimal imaging planes identified as above.

Novel T1 and T2 quantitative mapping can provide quantitative information on the studied mass. T1 mapping should be performed before and after the injection of contrast medium to evaluate T1 native, T1 enhanced and extracellular volume[27,28].

A cardiac mass protocol must include contrast-enhanced imaging with first pass perfusion sequences, EGE images, repetition of T1-weighted sequences and LGE sequences.

Perfusion imaging and EGE sequences are used to evaluate the lesion vascularization, the presence of hyperemia near the lesion and for differential diagnosis with thrombus. EGE images are acquired about 3 min after gadolinium injection.

LGE sequences are performed 10-15 min after contrast injection. LGE sequences are fast (or turbo) gradient echo inversion recovery sequences (IR-fast spin-echo)[22,24,29]. The inversion recovery pulse is used to null the signal of normal myocardium in order to maximize the contrast of areas with gadolinium accumulation (edema, increased extracellular space, necrosis). It is crucial to select a proper inversion time (TI). These sequences should be acquired in short axis covering all the ventricles and in the optimal imaging planes mentioned above both for tissue characterization of the mass and identification of any underlying cardiac pathology.

In summary, to assess each suspected cardiac mass, the protocol must be tailored in terms of the optimal acquisition planes and sequences in order to obtain an accurate tissue characterization.

Table 1 summarizes CMR characteristics of cardiac masses (non-neoplastic and neoplastic).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characteristic (location, signal intensity and contrast contrast-enhanced relative to that of adjacent normal myocardium) of benign and malignant cardiac masses

|

Lesion

|

Location

|

T1-WI

|

T2-WI

|

Cine-SSFP

|

Perfusion

|

EGE

|

LGE

|

|

| Non-neoplastic | ||||||||

| Thrombus Acute/subacute | Mural or intraluminal | Iso-Hyper | Iso-Hyper | Iso-hypo | No enhancement | No enhancement | Hypointense border and brighter central zone | |

| Thrombus Chronic | Mural or intraluminal | Hypo | Hypo | Iso-hypo | Rare | No enhancement | Rarely heterogeneous | |

| Pericardial cyst | Right cardiophrenic angle | Hypo | Hyper | Hyper | No enhancement | No enhancement | No enhancement | |

| Mitral annular calcification | Annular fibrous ring of the left atrio-ventricular valve | Hypo | Hypo | Iso-hypo | No enhancement | Peripheral rim of enhancement | Peripheral rim of enhancement | |

| Liquefaction necrosis | Annular fibrous ring of the left atrio-ventricular valve | Mildly Hyper | Mildly Hyper | Iso-hypo | No enhancement | Peripheral rim of enhancement | Peripheral rim of enhancement +/- core enhancement | |

| Neoplastic - Benign | ||||||||

| Myxoma | Left atrium, arising from the interatrial septum | Iso (heterogeneous) | Hyper (heterogeneous) | Hypo | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous | |

| Papillary fibroelastoma | Atrial side of the mitral valve and the aortic surface of the aortic valve leaflet | Iso | Iso | Hypo | Usually not assessable | Mild and homogeneous or no enhancement | Homogeneous or no enhancement | |

| Lipoma | Atrial septum and epicardium, but it may occur anywhere in the heart | Hyper | Hyper (Hypo on STIR images) | Hyper (with black boundary artifact or India ink artifact) | No enhancement | No enhancement | No enhancement | |

| Hemangioma | Every cardiac chamber and also from pericardial space | Iso | Hyper | Hyper | Heterogeneous, intense and prolonged | Homogeneous or heterogeneous | Homogeneous or heterogeneous | |

| Fibroma | Intramural growth in the ventricles (interventricular septum or the ventricular free wall) | Iso | Hypo | Iso-hypo | Mild and homogeneous | Mild and homogeneous | No enhancement or minimal uptake | |

| Rhabdomyoma | Intramyocardial or intracavitary, with intraventricular growth that may cause outflow obstruction | Iso | Mildly Hyper | Iso-hypo | No enhancement or minimal uptake | No enhancement or minimal uptake | No enhancement or minimal uptake | |

| Cardiac teratomas | Intrapericardial (usually compressing superior vena cava and/or right atrium) | Iso or Hypo | Hyper | Iso or Slightly hyper | No enhancement | Mild and heterogeneous | Heterogeneous | |

| Paraganglioma | On the roof of left atrium | Iso-Hypo with “salt and pepper” appearance | Hyper with “salt and pepper” appearance | Hyper | Strong enhancement | Heterogeneous Peripheral | Heterogeneous Peripheral | |

| Neoplastic - malignant: Primary cardiac tumor | ||||||||

| Angiosarcoma | Right atrium close to atrio-ventricular sulcus | Iso-Hyper (heterogeneous) | Hyper (heterogeneous) | Iso (heterogeneous) | Strong enhancement | Marked and Heterogeneous | Marked and Heterogeneous | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | Typically involve the left atrium | Iso | Iso-Hyper | Iso | Heterogeneous, intense | Marked and Heterogeneous | Marked and Heterogeneous | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Multiple masses and there is not any predilection in terms of cardiac structures involved | Iso | Iso-Hyper (hyper on STIR images) | Iso | Heterogeneous, intense | Marked and Heterogeneous | Marked and Heterogeneous | |

| Lymphoma | Right chambers, often right ventricle and are associated with pericardial effusion | Hypo-Iso | Mildly Hyper (more evident on STIR images) | Iso | Mild | Heterogeneous | No or progressive mild heterogeneous enhancement | |

| Mesothelioma | Pericardium | Iso | Hyper (heterogeneous) | Iso | Progressive enhancement | Intense enhancement | Intense enhancement | |

| Malignant - Malignant: metastatic disease | Mainly involve myocardium and pericardium | Low (except for Melanoma which is Hyper) | Hyper | Iso | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous | Heterogeneous | |

T1-WI: T1-weighted images; T2-WI: T2-weighted images; STIR: Short tau inversion recovery; Cine-SSFP: Cine-steady state free precession; EGE: Early gadolinium enhancement; LGE: Late gadolinium enhancement; Hypo: Hypointense; Iso: Isointense; Hyper: Hyperintense.

PSEUDOMASS

Eustachian valve

The eustachian valve, also known as the valve of the inferior vena cava (IVC), is a thin flap-like structure located in the right atrium (RA) at the orifice of IVC that helps direct blood flow through the foramen ovale during embryogenesis. Note that the terms eustachian ridge and eustachian valve are occasionally used interchangeably. However, the eustachian ridge technically refers to the fibrous structure contiguous with the free margin of the eustachian valve[30]. When in doubt, CMR imaging is particularly useful for characterization of the lesion on the basis of its typical location at the inferior cavoatrial junction, lack of enhancement and linear shape.

Crista terminalis

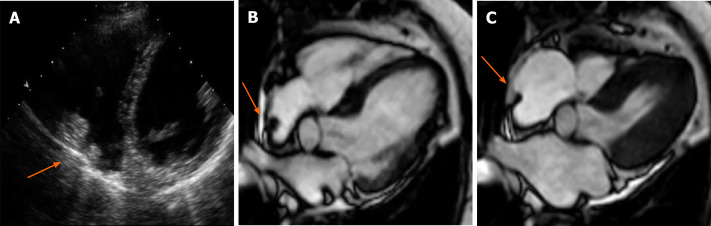

Crista terminalis, or terminal crest, is a horseshoe or twisted C-shaped fibromuscular ridge in the RA. It originates from the atrial septum, extends anteriorly, goes toward the right of the superior vena cava (SVC) orifice, subsequently descends along the posterolateral wall of the RA and turns anteriorly, terminating to the right of the IVC orifice. It is the remnant tissue from the septum spurium, which divides the embryologic primitive RA and sinus venosus[31]. It is an important anatomical landmark in electrophysiology owing to its relation to the sinoatrial node and artery, which should not be injured. Crista terminalis is present in every heart but is not always visualized at imaging. It varies in size, typically 3–6 mm, and is more prominent superiorly. Thrombus is a differential diagnosis (Figure 1), especially in patients with an indwelling right atrial catheter.

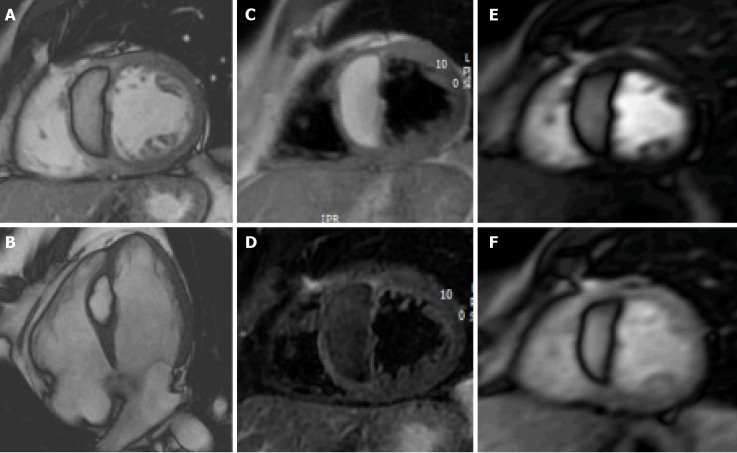

Figure 1.

Cardiac mass in a 68-year-old male. Transthoracic echocardiography shows (A) an apparently free mass in the right atrium mimicking a thrombus or a tumor (orange arrow). Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (B, C: 4-chamber cine steady state free precession diastolic and systolic frame respectively) reveals a pseudomass: A hypertrophied crista terminalis (orange arrow) with appearance of right atrial mass on transthoracic echocardiography.

Warfarin ridge (coumadin ridge)

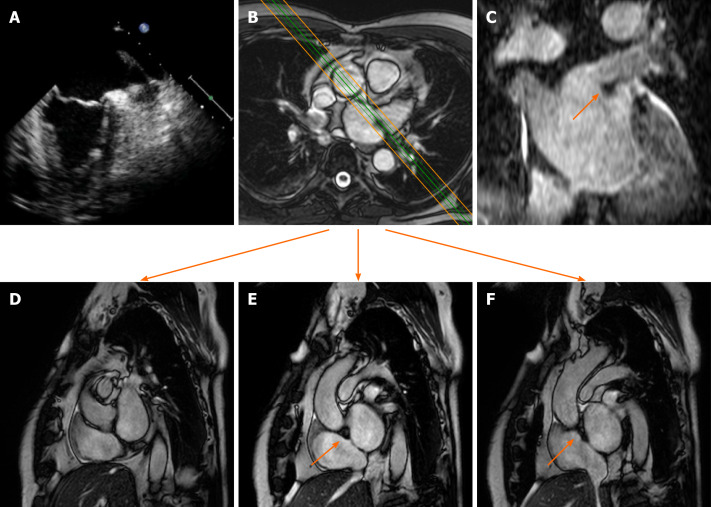

The coumadin ridge has been described from echocardiographic studies as a ridge of atrial tissue separating the left atrial appendage (LAA) from the left upper pulmonary vein[32]. It can present as a linear structure or even sometimes as a nodular mass that protrudes into the left atrium (LA). In the past, this structure was often mistaken for thrombus and resulted in patient being prescribed anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (coumadin), from which it derives its name. On cine-SSFP sequences, a prominent coumadin ridge can be identified by its typical location in the roof of the LA adjacent to the left upper pulmonary vein; a particularly prominent ridge can appear as a dark “mass” protruding into the bright left atrial cavity (Figure 2). Thrombus and myxoma are differential diagnosis. As the coumadin ridge is normal cardiac tissue, it should have the same signal intensity as adjacent myocardial tissue on both T1 and T2 -weighted imaging and typically does not show late gadolinium enhancement.

Figure 2.

Cardiac mass in a 63-year-old male with atrial fibrillation. Transthoracic echocardiography shows (A) a nodular mass that protrudes into the left atrium at the inlet of the left appendage. The patient underwent 2 mo of oral anticoagulant therapy, and the “mass” did not change. It was therefore requested a cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) (B: axial cine- steady state free precession (SSFP) with the correspondent perpendicular plane oriented according to the green and orange lines and reported in D, E and F), moreover it was performed a three dimensional-steady state free precession SSFP acquisition with an oriented reconstruction (C). Overall the CMR shows the presence of pseudomass (orange arrow), a prominent coumadin ridge in the roof of the left atrium adjacent to the left upper pulmonary vein.

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (IAS) is a benign condition characterized by mass like deposition of brown fat in the IAS. It results from adipose-cell hyperplasia and has been linked to advanced age and obesity[33]. Classically, there is sparing of the fossa ovalis, resulting in a dumbbell shape of the IAS. Unlike cardiac lipoma, lipomatous hypertrophy of the IAS appears as thickening and is not encapsulated. Lipoma is a differential diagnosis. Fat-suppressed sequences can be used at CMR imaging to characterize this pseudo-lesion; unenhanced chest CT can also help in confirmation of the diagnosis by measuring fat attenuation and demonstrating the dumbbell shape (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sixty-five-year-old male patient with a dumbbell-shaped mass along the interatrial septum with negative Hounsfield Unit values on computed tomography scan (A), cardiovascular magnetic resonance cine-steady state free precession images (B and C, diastolic and systolic frame respectively) reveals the chemical shift artifact, also known as “India ink” artifact, typical of structures with adipose content. These findings are in keeping with lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum (orange arrow).

MASS - NON-NEOPLASTIC

Thrombus

Intracardiac thrombi represent the most common cardiac masses, with a prevalence ranging between 2%-25% in normal population and between 3%-50% in patients with atrial fibrillation or left ventricular systolic dysfunction[3,34].

In case of atrial dilation or fibrillation, thrombi are usually located in the posterior wall of the LA or in the LAA. In the left ventricle, the location of thrombi usually relates to presence of regional or global wall motion abnormalities, as seen after myocardial infarction or in cardiomyopathies[35]. When thrombi are found in patients with normal systolic function and contractility, the presence of coagulation disorders should be considered[36]. Occasionally, thrombi can be located in the RA or in vena cava, especially in patients with enlarged right chambers and with central venous lines, and can mimic other masses[37-39].

Identification of a cardiac thrombus is pivotal to start anticoagulation treatment and to prevent systemic or pulmonary embolic events[40]. In most cases, the diagnosis is accidental, and patients are asymptomatic. Generally, thrombi are attached to cardiac walls by a broad base and are immobile. If they are pedunculated and mobile, distinguishing them from other tumors may be challenging.

CMR has excellent contrast resolution and allows for superior soft tissue characterization. It provides a combined evaluation of morphology, composition and LGE of cardiac masses, with unique advantage of being non-invasive assessment[41,42].

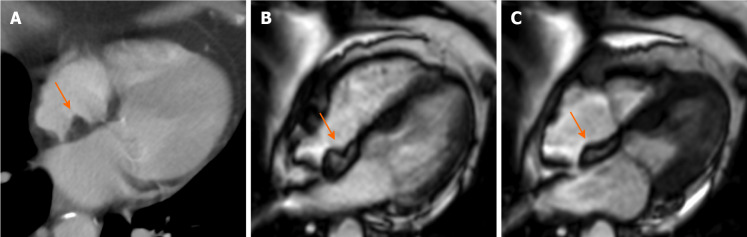

On CMR, thrombi may have different signals, depending on their age and sequence used. Fresh thrombi have a higher signal than myocardium on T1-weighted sequences, and contrast is further accentuated on T2-weighted images, due to high amount of hemoglobin[35]. After 1-2 wk, they tend to have increased signal on T1-weighted images and decreased on T2-weighted images, due to paramagnetic effect caused by deoxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin in the organizing thrombus[38]. Chronic organized thrombi have low signal either on T1- and T2-sequences, due to loss of water and protons, and they can appear heterogeneous in presence of calcifications (Figure 4).

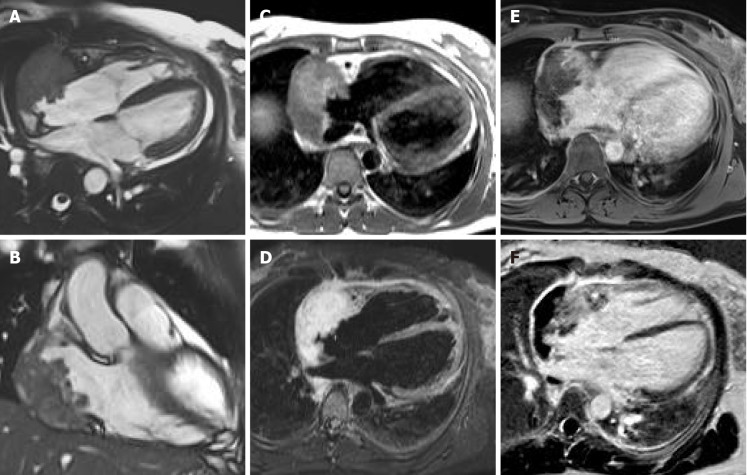

Figure 4.

Sixty-six-year-old male patient with a history of myocardial infarction and suspected thrombotic formation at echocardiographic transthoracic examination. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance shows a hypointense intraventricular “mass” at the left ventricular apex (orange arrow) in the early gadolinium enhancement (A) and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) (B) sequences near the infarcted wall (i.e. with transmural LGE involvement). The patient underwent 3 mo of anticoagulant therapy with disappearance of the thrombus in the follow-up examination.

Differentiation between thrombus and slow-flowing blood on spin-echo sequences may be difficult, due to poor contrast. On the other hand, gradient-echo sequences (or bright-blood imaging) allow for an improved contrast of thrombi from the surrounding blood pool, and clots usually have lower signal compared to normal myocardium[38].

The differentiation between thrombus and myocardium on bright-blood imaging can be difficult when thrombi have similar signal intensity of adjacent myocardium. However, the advantage of bright-blood imaging is represented by cine-CMR, which provides a dynamic evaluation of cardiac motion and blood flow. Balanced SSFP sequences are the most used for cine-CMR in clinical routine for precise detection of mural thrombi[43]. Other sequences that have been successfully used to detect thrombi are phase-contrast sequences with myocardial tagging. Mapping sequences do not provide any T1 or T2 values useful for diagnosis. However, a characteristic pattern of hyperintensity-isointensity-hypointensity has been described for thrombi when TI scout is performed at increasing inversion times, and it may allow to differentiate clots from other cardiac tumors[42].

The method that has shown the best performance for thrombus imaging on CMR is represented by LGE imaging[4]. This technique allows for a straightforward diagnosis, even in case of small thrombi, and independently of their location. Moreover, the presence of thrombus enhancement may also help to differentiate between subacute and chronic clots. In fact, subacute thrombi present homogeneously low-signal, without late enhancement, and can manifest magnetic susceptibility artifacts. In contrast, organized thrombi have intermediate signal and can be heterogeneous due to multiple areas of late enhancement, hindering a prompt differentiation from other cardiac masses[44].

Pericardial cyst

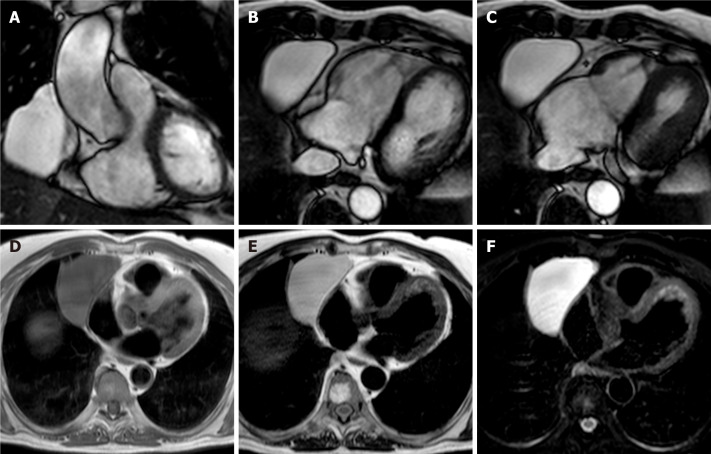

Pericardial cysts account for approximately 7% of all mediastinal masses and 33% of all mediastinal cysts, with an incidence of 1/100000. They are mostly congenital lesions, and commonly located in the right (51%–70%) or left cardiophrenic angles (28%–38%)[45-47]. The cyst walls consist of a single layer of mesothelial cells, and they are usually filled with clear fluid. On CMR they have low signal on T1-weighted sequences and high signal on T2-weighted images[48,49]. There is not fluid enhancement on LGE imaging, but enhancing walls or intracystic septations may be observed (Figure 5). CMR ability to discriminate these lesions from other mediastinal masses allows to avoid further invasive diagnostic procedures, since most patients are usually asymptomatic.

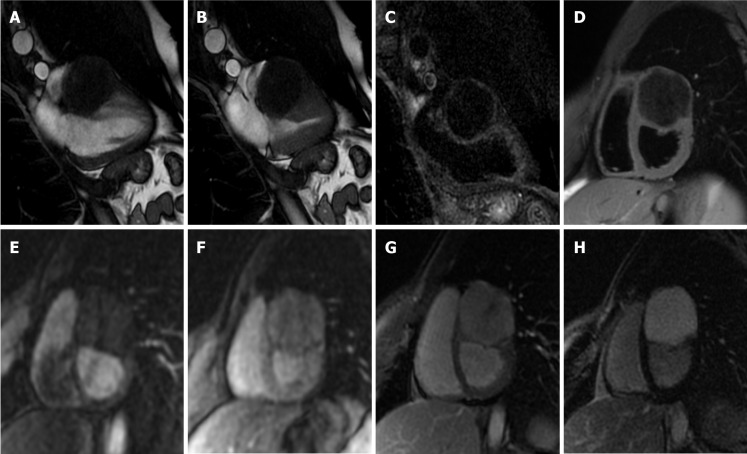

Figure 5.

Fifty-seven-year-old female patient with parenchymal mass in the right cardiophrenic angle on chest X-ray. This finding was first investigated by chest computed tomography and then by cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) (A-C). The CMR confirm the presence of the mass on cine-steady state free precession images (A and B, two orthogonal diastolic frames of plane through the mass respectively), without sign of infiltration confirmed by the preserved movement of the heart chambers in relation to the mass itself. The mass shows low signal on T1-weighted sequences (D) and high signal on T2-weighted images (E and F, without and with fat suppression, respectively). These findings are in keeping with pericardial cyst.

Symptoms may occur when cysts impinge upon or erodes into adjacent structures. In case of cardiac compression, patients may present with retrosternal pain or congestive heart failure symptoms, especially if the right side of the heart is involved. Treatment is usually conservative and CMR is particularly helpful to assess stability of the lesion. When pericardial cysts do not enlarge and patients are asymptomatic, a continued surveillance is the favored option. In contrast, when cysts enlarge and patients present symptoms, surgery may be indicated, mainly to prevent compressive effects and life-threatening complications[50].

Mitral annular calcification and liquefaction necrosis

Calcification of the mitral annulus is the result of a chronic non-inflammatory process, which is characterized by calcium deposition in the annular fibrous ring of the left atrio-ventricular valve[51].

It is more frequent in older patients, and it is related to altered metabolism of calcium phosphate and to chronic renal disease. Mitral annular calcification may present as an immobile mass, generally located in the inferior or inferolateral portion of the mitral anulus. In severe cases it may involve the whole annulus and compress the adjacent myocardium. Usually, it is composed by a calcified core enclosed by a fibrotic envelope. On CMR, it is typically characterized by low signal on T1- and T2-weighted sequences, without enhancement after intravenous injection of gadolinium. However, the fibrotic envelope may show a peripheral rim of enhancement on LGE imaging[51] (Figure 6). Rarely, this lesion can evolve to liquefaction necrosis (or caseous calcification). In this case, the core contains a mixture of cholesterol, fatty acids, and amorphous eosinophilic infiltrate, with a surrounding rim that encloses macrophages, lymphocytes and multiple necrotic areas with calcifications[29].

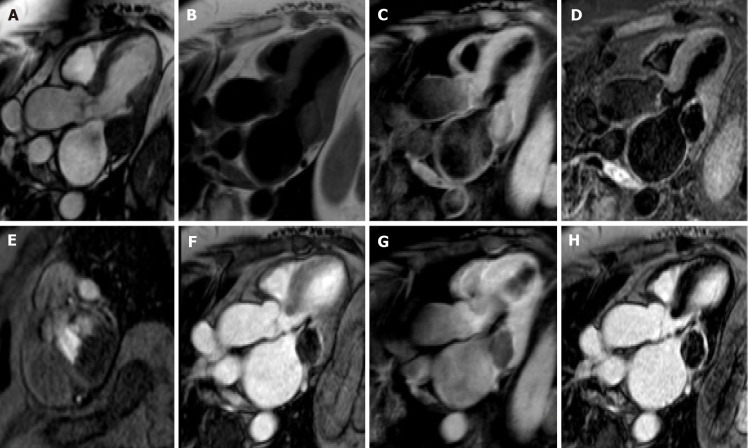

Figure 6.

Eighty-year-old female with hyperechoic mass of uncertain significance in the left atrio-ventricular groove discovered at transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance confirms the presence of the mass with the cine- steady state free precession images (A). The mass shows slight hyperintense signal on T1-weighted images without and with fat suppression (B and C, respectively), due to the presence of proteinaceous material, and hypointense signal on short tau inversion recovery images (D). The mass shows no contrast uptake during perfusion sequences (E) and no contrast enhancement both on early gadolinium enhancement images (F), T1- weighted images (G) repeated after the contrast medium injection, and late gadolinium enhancement images (H) with a peripheral rim of enhancement. These findings are in keeping with caseous calcification of the mitral valve.

In contrast to the previous entity, the proteinaceous and fatty components of the central part of the lesion may manifest with high signal on T1- and T2-weighted sequences. Moreover, core enhancement is typically observed, either in the early or late phases after gadolinium injection[29]. Both these entities are considered benign and they are usually asymptomatic and discovered as incidental findings. Symptoms are usually caused by related complications such as mitral stenosis or regurgitation, infective endocarditis and embolization.

Vegetations

CMR can be of help in visualization of valve or mural vegetations, either to clarify echocardiographic findings or to establish the diagnosis. They may not be visible on dark-blood imaging, while they are better depicted on cine-CMR, manifesting as low-signal areas that follow the motion of the cusp to which they are connected[52]. The differentiation from thrombus may be difficult, because both masses usually do not show contrast enhancement. However, a peripheral rim enhancement on LGE imaging has been observed in vegetations and might facilitate the differentiation from other cardiac masses. The presence of adjacent myocardial enhancement or endothelial lining may indicate irreversible myocardial damage or fibrosis, and they may represent indirect signs of infective endocarditis or perivalvular abscess[53].

Cardiac vegetations can also be found secondary to inflammation, in association with sterile endocarditis, as Libman-Sacks endocarditis. This is characteristic of patients suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus and can manifest with small verrucous vegetations, more frequently involving the mitral and aortic valves[54].

NEOPLASTIC-BENIGN

Myxoma

Cardiac myxomas, the most common primary benign cardiac tumor, are well-defined spherical or ovoidal mobile lobulated masses frequently in the LA (80%), arising from the IAS (80%)[55,56]. Less common locations are the posterior and lateral LA wall, the LAA, the mitral and tricuspid valve, the posterior RA wall and, rarely, the ventricles and the pulmonary artery[57]. The endocardial attachment point may be broad, sessile or narrow or pedunculated (typically mobile). Myxomas prolapse through the mitral valve has been reported in 30% of cases. Cardiac myxoma may be part of the Carney complex[58].

There are three patterns on CMR: Most frequently it is isointense in T1-weighted and hyperintense in T2-weighted images. Conversely, it might appear hypointense in both T1 and T2 due to calcifications or extremely hyperintense in T2 with “pseudocystic” appearance[56,57]. At first pass perfusion, it presents weaker enhancement than myocardium (16%-66%)[55]. About half of cardiac myxomas present heterogeneous LGE[23,57] (Figure 7). On parametric imaging, they show elevated native T1 and T2 relaxation times and extracellular volume values[27].

Figure 7.

Seventy-nine-year-old female patient with left atrial mass adherent to the interatrial septum discovered on cardiac computed tomography angiography. The cardiovascular magnetic resonance confirms the presence of the mass using the cine- steady state free precession images (A and B, two orthogonal planes along the mass respectively). The site of lesion and its heterogeneous appearance on T2-weighet sequence (C and D) short tau inversion recovery, are in keeping with cardiac myxoma.

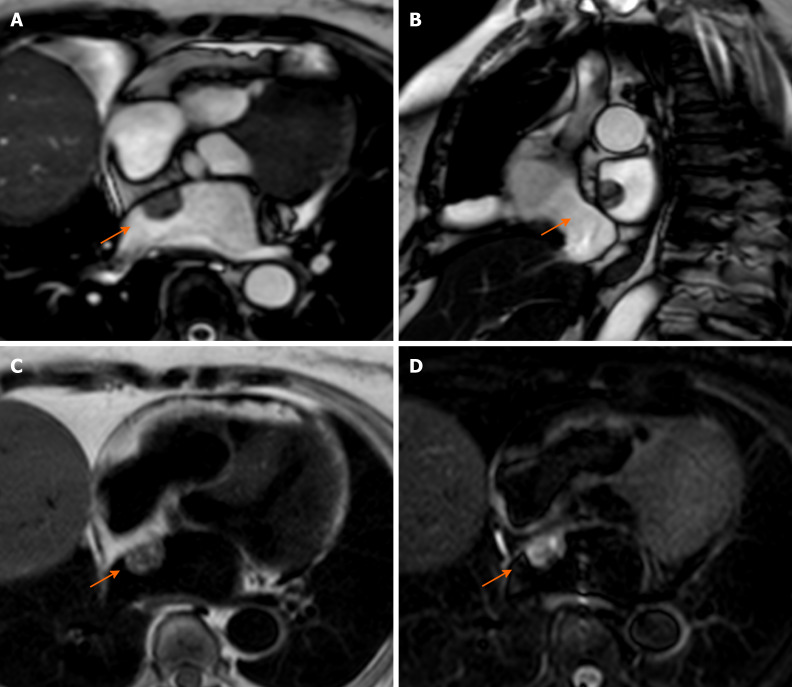

Papillary fibroelastoma

Papillary fibroelastoma (PF) is the most common cardiac valve tumor. It can arise from any endocardial surface but the most common locations are the atrial side of the mitral valve and the aortic surface of the aortic valve leaflets[23]. PFs are usually small lesions (< 1.5 cm) composed of collagen and elastic fibers lined by endothelium with a short pedicle[59]. PF presents signal isointense to normal myocardium in both T1- and T2-weighted images. On SSFP sequences, it appears as a well circumscribed mobile valve nodule with possible perilesional artefact[60]. PFs may have homogeneous LGE[61] (Figure 8). PFs have elevated native T1 and T2 relaxation times[23].

Figure 8.

Seventy-one-year-old female with incidental finding of cardiac mass adherent to the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. The examination was performed for suspected noncompact myocardium on a previous ultrasound examination in a patient with known metastatic thyroid cancer. Orange arrow shows a mobile “valvular” mass at cine-steady state free precession (SSFP) imaging (A and B), with intermediate signal on T1-weighted images (C), high signal on T2 short tau inversion recovery images (D) and with poor enhancement at late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) images (E and F). This location of the mass and its cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) features are in keeping with fibroelastoma. The patient underwent a periodic CMR follow-up for 3 years (G: cine-SSFP and H: LGE sequences), and the mass shows no change.

Lipoma

Lipoma is the second most common benign cardiac tumor; most frequently it grows within the atrial septum and epicardium, but it may occur anywhere in the heart.

At CMR lipoma generally shows a homogeneous nodular elevated signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences, slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images and hypointense on fat-saturated images. Lipomas do not present contrast enhancement or LGE (Figure 9). They have elevated T1 relaxation times with intermediate values on T2 mapping[23,62].

Figure 9.

Fifty-one-year-old male patient, with incidental finding of a suspicious intraseptal hyperechoic mass at transesophageal echocardiography. Cine-steady state free precession magnetic resonance (A and B) confirms the presence of an intraseptal mass with a chemical shift artefact at the border. The mass shows high signal intensity on proton density-weighted images (C) and low signal intensity on short tau inversion recovery images (D). The mass shows no enhancement on perfusion images (E and F, two different frame). These findings are in keeping with cardiac lipoma.

Hemangioma

Hemangioma accounts for approximately 5%-10% of benign cardiac masses. They are slow flow vascular malformations that can arise in every cardiac chamber and also from pericardial space. Most patients are asymptomatic, and cardiac hemangioma is discovered serendipitously; symptomatic patients may present with dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, arrhythmias, pericarditis, pericardial effusion, syncope and sudden death. Cardiac hemangiomas can occur in Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, characterized by multiple systemic hemangiomas, recurrent thrombocytopenia and consumptive coagulopathy[63].

At CMR hemangiomas have isointense signal to myocardium on T1-weighted images because of slow blood flow and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images[23,63,64]. On first pass and LGE sequences they have intense and prolonged enhancement and may appear heterogeneous depending on the presence of fibrotic tissue and calcifications[23,64].

Fibroma

Fibromas are benign neoplasms of the connective tissue that originate from fibroblasts, predominantly seen infants and children (the second most common congenital tumor after rhabdomyoma). Almost one-third of patients with cardiac fibroma are asymptomatic and they are mostly diagnosed incidentally. Symptomatic patients may present with arrhythmias, heart failure, or sudden death. Fibromas are usually solitary tumors (unlike rhabdomyomas) usually with intramural growth that involve the ventricles, either in interventricular septum or ventricular free walls[41,65]. They do not regress, unlike rhabdomyomas, therefore surgery is required[66]. Macroscopically, they are solid tumors with dimensions varying from few millimeters to a size that can obliterate cardiac chambers. Microscopically, they are composed of fibroblasts, and calcification is a common finding[67]. At echocardiography, they appear as a large, noncontractile, heterogeneous solid mass[65]. On CMR fibroma are well-defined masses, generally isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted images, and homogeneously hypointense on T2-weighted images[41,65].

Fibromas can show different enhancement patterns after gadolinium administration. In fact, they may not show any LGE, or manifest homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement with isointense rim and hypointense core, which is due to decreased blood supply from the surrounding myocardium[64] (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Twenty-five-year-old male patient with a ventricular mass of uncertain significance on computed tomography scan performed after an episode of dyspnea and chest pain. The cardiovascular magnetic resonance demonstrates a well-defined, solitary solid mass with intramural growth in the anterior wall of the left ventricle (A and B, cine steady state free precession diastolic and systolic frame, respectively). The mass shows homogeneous hypointense signal on short tau inversion recovery (C) and T1-weighted images (D). Homogeneous contrast uptake during perfusion sequences (E and F, two different frame of the perfusion sequence) and homogeneous hyperintensity in the early (G) and late gadolinium enhancement images (H). These findings are in keeping with cardiac fibroma. The patient finally underwent cardiac surgery, and the final histopathological diagnosis confirmed the radiological suspicion.

Rhabdomyoma

Rhabdomyomas are very rare in adults, while they are the most common cardiac tumors during fetal life and childhood. From a histopathological point of view, rhabdomyomas are hamartomas, and they are often associated with tuberous sclerosis. In particular, the incidence of tuberous sclerosis in patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas is 60%–80%, and more than 50% of patients with tuberous sclerosis have rhabdomyomas[65].

Rhabdomyomas are multiple in more than 60% of cases, and this multiplicity has an even higher association with tuberous sclerosis; nevertheless, findings of multiple cardiac masses at prenatal echocardiogram can be the first suggestion of tuberous sclerosis[65]. Rhabdomyomas are usually intramyocardial or intracavitary, with intraventricular growth that may cause outflow obstruction; less commonly, they may be located in the atrioventricular groove ,possibly causing arrhythmias related to an accessory pathway[65]. The majority of rhabdomyomas spontaneously regress in early childhood, therefore surgery is needed only in case of heart failure due to outflow obstruction or arrhythmias[68]. Rhabdomyomas appear as hyperechoic solid masses on echocardiogram[65]. On CMR, they are isointense (or slightly hyperintense) on T1-weighted images, and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with mild LGE[29].

Cardiac teratomas

Cardiac teratomas are rare and usually occur in children, representing the second most common primary cardiac tumor in newborns and fetal life. Cardiac teratomas derive from germ cells localized in pericardium. Usually, it is intrapericardial and attached to pulmonary artery and aorta and can compress SVC and RA. Intramyocardial teratoma is extremely rare and often manifests with congestive heart failure. Surgery is the treatment of choice. Recurrence or malignant degeneration is rare[68].

Typically, imaging modalities show an intrapericardial multilocular mass with cystic and solid components near aorta and pulmonary artery. On CMR, teratomas may appear iso- or hypointense on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images and hypointense on first-pass myocardial perfusion imaging, with this latter allowing to differentiate them from hemangiomas. After contrast injection teratomas appear hypointense on first pass perfusion, with heterogeneous LGE[69].

Paragangliomas

Paragangliomas are extremely rare, with an incidence varying between 1.5-9 cases per million people, and it is higher in the fourth decade of life. Up to a third of them may be familial, which makes important a proper family screening. Cardiac paragangliomas represent up to 2% of all paragangliomas[70,71].

They are chromaffin-cell tumors that arise from parasympathetic or sympathetic ganglia of neural crest cells localized outside adrenal glands. They may present as a cardiac mass associated with hypertension and/or palpitation. Echocardiography, computed tomography and CMR can provide valuable anatomical and tissue characterizations, however laboratory investigations such as urine and blood tests for analysis of catecholamines and catecholamines metabolites are required to assess the diagnosis[72] .

CMR shows hypointense signal on T1 weighted images and hyperintense signal on T2 with “salt and pepper” appearance on both T1 and T2 weighted sequences; salt represents hemoglobin degradation products from intralesional hemorrhage and pepper depends on flow voids due to high vascularity. Paragangliomas show strong and early contrast enhancement after gadolinium injection, which follows the arterial vessels enhancement[72]. These tumors are characterized by peripheral LGE, due to tumor necrosis.

Biopsy is contraindicated in these hyper-vascularized tumors due to the high risk of life-threatening bleeding.

NEOPLASTIC–MALIGNANT: PRIMARY CARDIAC TUMOR

Table 2 shows the CMR characteristics of cardiac masses that facilitates the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant masses.

Table 2.

Malignant tumor characteristic

| Size | More than 5 cm |

| Number | More than one |

| Location | Right heart involvement or more than one cardiac chamber |

| Implantation | Broad base of implantation |

| Infiltration | Direct infiltration of structures such as myocardium, valves, epicardial fat and pericardial leaflets |

| Effusion | Pericardial or pleural hemorrhagic effusion |

| Signal intensity | Heterogeneous signal intensity in T1-weighted and T2-weighted images |

| Perfusion | Heterogeneous enhancement |

| EGE and LGE | Heterogeneous enhancement |

EGE: Early gadolinium enhancement; LGE: Late gadolinium enhancement.

Sarcomas

Angiosarcoma is the most common cardiac mass and accounts approximately for 30% of malignant primary cardiac tumors[73]. It occurs mainly in the middle-aged adults and males are more often affected than females at a ratio of 2:1. Angiosarcoma is highly aggressive neoplasm characterized by rapid local spread and distant metastases. In approximately 75% of cases, angiosarcomas are located in RA close to atrio-ventricular sulcus[19]. However, as mentioned above, the loco-regional infiltration with involvement of pericardium, tricuspid valve, SVC, right ventricle and right coronary artery is also common[19]. It can cause symptoms such as chest pain and arrhythmias. The most common site of metastasis of angiosarcoma is lung followed by liver and brain[74].

The CMR characteristic of angiosarcoma reflects the heterogenous composition of angiosarcoma characterized by high vascularization, necrosis, hemorrhage and calcification[19]. T1 and T2 weighted images show heterogenous hyperintense signal intensity due to complex composition of mass with marked enhancement after contrast medium injection due to hyper vascularized nature of the mass[19] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Sixty-five-year-old female patient with transthoracic echocardiogram finding of irregular mass originates from the right atrium wall with intracavitary expansion. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance with cine-steady state free precession images (A and B) confirms the presence of an infiltrative atrial mass in the proximity of atrio-ventricular sulcus. T1-weighted and short tau inversion recovery images (C and D, respectively) show an heterogenous hyperintense signal intensity due to complex composition of the mass. The mass shows inhomogeneous enhancement at early gadolinium enhancement and late gadolinium enhancement sequences (E and F, respectively). These findings are in keeping with a malignant primary cardiac tumor. The patient underwent myocardial biopsy with diagnosis of angiosarcoma.

Leiomyosarcoma usually represent the 8%-9% of cardiac sarcomas and is associated with a worst prognosis in 6-14 mo[19,75]. In 60% of cases, leiomyosarcoma involve the LA followed by the involvement of right ventricle, RA and left ventricle[19]. Similar to other cardiac masses the main problems caused by tumors are mainly due to loco-regional invasion. The presence of leiomyosarcoma in the LA can cause pulmonary vein obstruction, pericardial effusion, chest pain, atrial arrhythmias and congestive heart failure. Furthermore, leiomyosarcoma is often characterized by rapid growth with distant metastasis and local recurrence after removal[75]. The CMR characteristics show hypo-isointense mass in T1 weighted sequences and hyperintense signal intensity in T2 weighted images[19]. LGE images show heterogenous signal intensity on post-contrast images due to hypervascular areas and necrosis[19].

Rhabdomyosarcoma represent the most common malignant cardiac mass in childhood[23]. Patients with rhabdomyosarcoma often show multiple masses, and there is not any predilection in terms of cardiac structures involved[23]. Rhabdomyosarcoma has the tendency to infiltrate the surrounding structures and in particular pericardium and valves[76]. Common symptoms include arrhythmia and heart failure sometimes associated with eosinophilia[19]. CMR shows isointense signal intensity on T1 and T2 images with hyperintense signal intensity on STIR images in presence of necrosis[23]. After the administration of contrast medium, rhabdomyosarcoma shows enhancement due to increased vascularization[19].

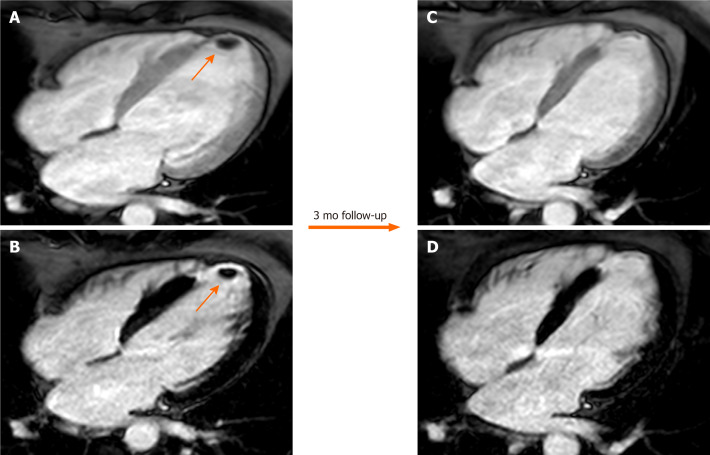

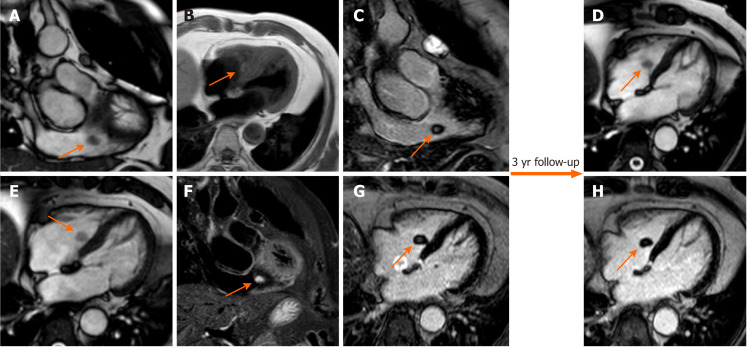

Lymphoma

Primary cardiac lymphoma usually occurs in 1.3% of primary cardiac tumors; typically arising from large B-cells in immunocompromised patients with an average age of 60-years-old[19]. Usually, masses are allocated in right chambers, often right ventricle, and are associated with pericardial effusion[63]. Despite the aggressive nature of this tumor, it shows a good response to monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody[23]. CMR images can be identified usually with the following two patterns: The first pattern shows multiple isointense masses in T1 and mildly hyperintense in T2 weighted images often located in right ventricle[77], while the second pattern is characterized by diffuse pericardial invasion of soft tissue associated with hemorrhagic effusion[23]. After administration of contrast agent, LGE usually shows no or progressive mild enhancement (Figure 12).

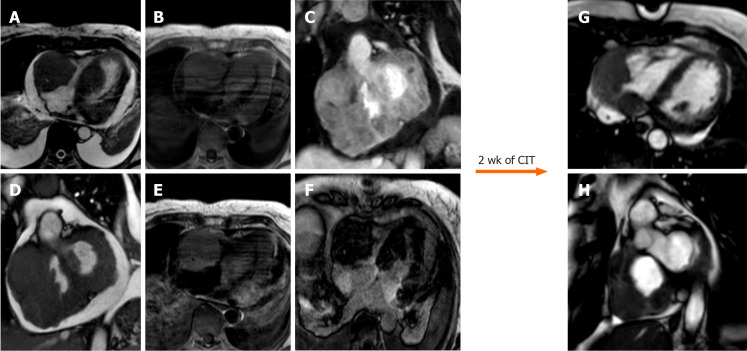

Figure 12.

Sixty-five-year-old female with transthoracic echocardiogram finding of two masses in the left ventricle and right cavities following an episode of lipothymia. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) with cine-steady state free precession images (A and B) demonstrates the presence of four distinct masses, the most voluminous mass with infiltrative features and irregular margins, extending from the right atrio-ventricular groove to both atrial and the ventricular walls. These lesions are characterized by a substantially isointense signal to cardiac muscle in T1-weighted images (C), slightly hyperintense in T2-weighted images (D) with heterogeneous enhancement at early gadolinium enhancement and relatively homogeneous hypointensity at late gadolinium enhancement images (E, F). These findings are in keeping with cardiac lymphoma. The patient underwent biopsy with a diagnosis of cardiac large B-cell lymphoma and started a chemoimmunotherapy with an excellent response as shown on CMR (G and H, cine steady state free precession) after 2 wk. CIT: Chemoimmunotherapy.

Mesothelioma

Pericardial mesothelioma is usually associated with asbestos exposure, and it is characterized by masses arising from pericardium, with pericardial thickening and hemorrhagic pericardial effusion[19]. Involvement of myocardium by mesothelioma is extremely rare, however protrusion of nodular mass from myocardium is suggestive for tumor invasion[19,78]. Symptoms related to pericardial mesothelioma often include breathlessness, chest pain and sometimes pericardial constriction or cardiac tamponade[23]. T1-weighted images show isointense mass, while T2-weighted images present heterogeneous hyperintense signal intensity[23]. Post-contrast images show high intense signal intensity on LGE images[23].

NEOPLASTIC–MALIGNANT: METASTATIC DISEASE

Secondary malignant cardiac tumors, also known as cardiac metastases, are cancerous tumors with spread to cardiac structures. Cardiac metastasis are very common in patients with primary tumors (usually arise from lung, breast and melanoma[12]), often clinically silent and mainly involve myocardium and pericardium[73].

Tumors can spread to the heart through four alternative pathways: Coronary arteries, lymphatic system, direct extension from nearby tissue and intracavitary diffusion through either the IVC or the pulmonary veins[23] (Figure 13).

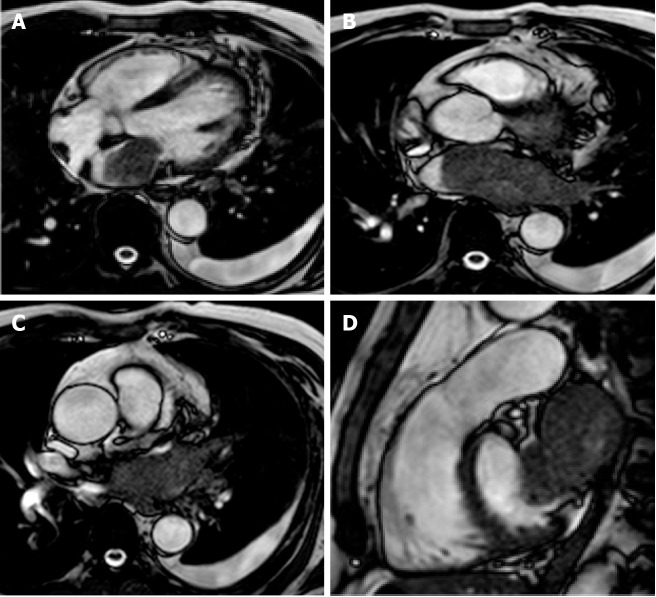

Figure 13.

Sixty-five-year-old male with lung cancer. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance examination with cine-steady state free precession sequences in planes of various orientations (A-D) clearly shows infiltration of the atrium through the pulmonary veins.

CMR finding on tissue characterization are not specific and can change based on the metastasis component, however the most common pattern show low signal intensity on T1 and high signal intensity on T2 weighted images with high signal intensity on LGE[23]. Metastasis due to melanoma are characterized by high signal intensity on T1 weighted images[79] (Figure 14).

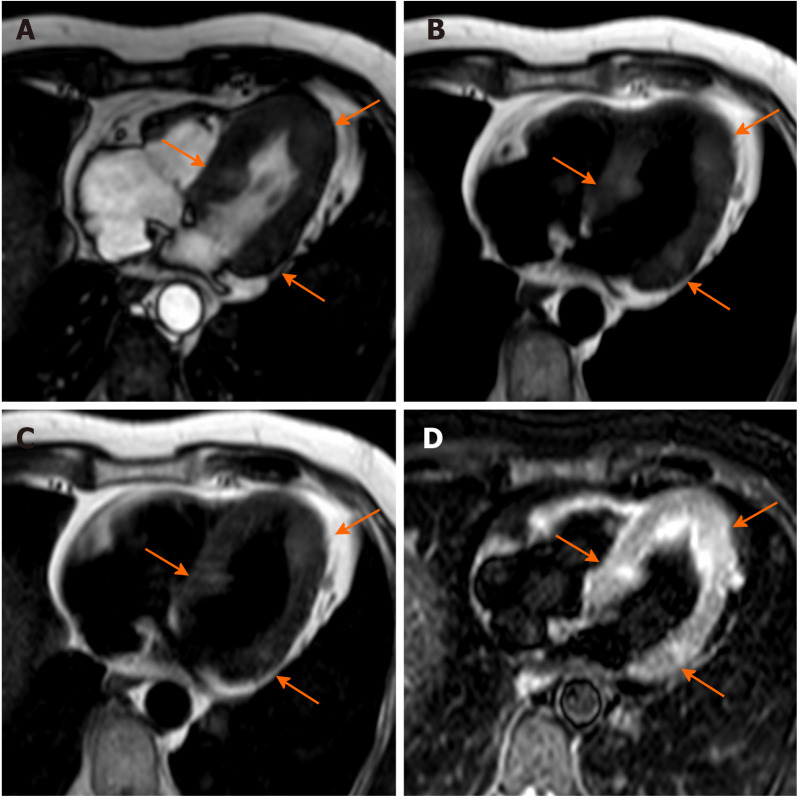

Figure 14.

Sixty-four-year-old male with ocular melanoma with multiple metastases underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance for characterization of a myocardial mass discovered at echocardiography. Nine oval nodules (three are indicated by orange arrows) with diameters ranging from 5 mm to 19 mm, slightly hyperintense in cine-steady state free precession images, T1-weighted (due to the presence of melanin) and T2-weighted sequences. The findings are in keeping with cardiac melanoma localization.

CONCLUSION

CMR is a fundamental radiological method in patients with suspected cardiac mass. It allows an optimal non-invasive localization of the lesion, providing multiplanar information on its relation to the surrounding structures. Moreover, with the additional feature of tissue characterization, CMR can be highly effective to distinguish pseudomasses from masses, as well as benign from malignant masses, that can also be used for differential diagnosis in the latter. Although histopathological assessment sometimes has an important role to make a definitive diagnosis, CMR is a key modality in the diagnosis of suspected cardiac masses with a great impact on patient management.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed

Peer-review started: March 18, 2021

First decision: July 8, 2021

Article in press: October 27, 2021

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gokce E S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Marco Gatti, Radiology Unit, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy. marcogatti17@gmail.com.

Tommaso D’Angelo, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Morphological and Functional Imaging, “G. Martino” University Hospital Messina, Messina 98100, Italy.

Giuseppe Muscogiuri, Department of Radiology, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, San Luca Hospital, Milan 20149, Italy.

Serena Dell'aversana, Department of Radiology, S. Maria Delle Grazie Hospital, Pozzuoli 80078, Italy.

Alessandro Andreis, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy.

Andrea Carisio, Radiology Unit, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy.

Fatemeh Darvizeh, School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20121, Italy.

Davide Tore, Radiology Unit, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy.

Gianluca Pontone, Department of Cardiovascular Imaging, Centro Cardiologico Monzino, IRCCS, Milan 20138, Italy.

Riccardo Faletti, Radiology Unit, Department of Surgical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin 10126, Italy.

References

- 1.Aggeli C, Dimitroglou Y, Raftopoulos L, Sarri G, Mavrogeni S, Wong J, Tsiamis E, Tsioufis C. Cardiac Masses: The Role of Cardiovascular Imaging in the Differential Diagnosis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10121088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim MJ, Jung HO. Anatomic variants mimicking pathology on echocardiography: differential diagnosis. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2013;21:103–112. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2013.21.3.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stöllberger C, Chnupa P, Kronik G, Brainin M, Finsterer J, Schneider B, Slany J. Transesophageal echocardiography to assess embolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. ELAT Study Group. Embolism in Left Atrial Thrombi. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:630–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinsaft JW, Kim HW, Shah DJ, Klem I, Crowley AL, Brosnan R, James OG, Patel MR, Heitner J, Parker M, Velazquez EJ, Steenbergen C, Judd RM, Kim RJ. Detection of left ventricular thrombus by delayed-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance prevalence and markers in patients with systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.L'Angiocola PD, Donati R. Cardiac Masses in Echocardiography: A Pragmatic Review. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2020;30:5–14. doi: 10.4103/jcecho.jcecho_2_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahouma M, Arisha MJ, Elmously A, El-Sayed Ahmed MM, Spadaccio C, Mehta K, Baudo M, Kamel M, Mansor E, Ruan Y, Morsi M, Shmushkevich S, Eldessouki I, Rahouma M, Mohamed A, Gambardella I, Girardi L, Gaudino M. Cardiac tumors prevalence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;76:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sütsch G, Jenni R, von Segesser L, Schneider J. [Heart tumors: incidence, distribution, diagnosis. Exemplified by 20,305 echocardiographies] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1991;121:621–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basso C, Valente M, Poletti A, Casarotto D, Thiene G. Surgical pathology of primary cardiac and pericardial tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1997;12:730–7; discussion 737. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(97)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam KY, Dickens P, Chan AC. Tumors of the heart. A 20-year experience with a review of 12,485 consecutive autopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:1027–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basso C, Rizzo S, Valente M, Thiene G. Cardiac masses and tumours. Heart. 2016;102:1230–1245. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekmektzoglou KA, Samelis GF, Xanthos T. Heart and tumors: location, metastasis, clinical manifestations, diagnostic approaches and therapeutic considerations. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9:769–777. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f88e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klatt EC, Heitz DR. Cardiac metastases. Cancer. 1990;65:1456–1459. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6<1456::aid-cncr2820650634>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bussani R, Castrichini M, Restivo L, Fabris E, Porcari A, Ferro F, Pivetta A, Korcova R, Cappelletto C, Manca P, Nuzzi V, Bessi R, Pagura L, Massa L, Sinagra G. Cardiac Tumors: Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:169. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01420-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poterucha TJ, Kochav J, O'Connor DS, Rosner GF. Cardiac Tumors: Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:66. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemasle M, Lavie Badie Y, Cariou E, Fournier P, Porterie J, Rousseau H, Petermann A, Hitzel A, Carrié D, Galinier M, Marcheix B, Lairez O. Contribution and performance of multimodal imaging in the diagnosis and management of cardiac masses. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:971–981. doi: 10.1007/s10554-020-01774-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng Q, Lai H, Lima J, Tong W, Qian Y, Lai S. Echocardiographic and pathologic characteristics of primary cardiac tumors: a study of 149 cases. Int J Cardiol. 2002;84:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckley O, Madan R, Kwong R, Rybicki FJ, Hunsaker A. Cardiac masses, part 1: imaging strategies and technical considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W837–W841. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tumma R, Dong W, Wang J, Litt H, Han Y. Evaluation of cardiac masses by CMR-strengths and pitfalls: a tertiary center experience. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:913–920. doi: 10.1007/s10554-016-0845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Chen Y, Liu J, Xu L, Li Y, Liu D, Sun Z, Wen Z. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of primary cardiac tumors. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10:294–313. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mousavi N, Cheezum MK, Aghayev A, Padera R, Vita T, Steigner M, Hulten E, Bittencourt MS, Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Kwong RY, Dunne R, Blankstein R. Assessment of Cardiac Masses by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Histological Correlation and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e007829. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pontone G, Di Cesare E, Castelletti S, De Cobelli F, De Lazzari M, Esposito A, Focardi M, Di Renzi P, Indolfi C, Lanzillo C, Lovato L, Maestrini V, Mercuro G, Natale L, Mantini C, Polizzi A, Rabbat M, Secchi F, Secinaro A, Aquaro GD, Barison A, Francone M. Appropriate use criteria for cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR): SIC-SIRM position paper part 1 (ischemic and congenital heart diseases, cardio-oncology, cardiac masses and heart transplant) Radiol Med. 2021;126:365–379. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01332-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito A, De Cobelli F, Ironi G, Marra P, Canu T, Mellone R, Del Maschio A. CMR in the assessment of cardiac masses: primary malignant tumors. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:1057–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoey ET, Shahid M, Ganeshan A, Baijal S, Simpson H, Watkin RW. MRI assessment of cardiac tumours: part 1, multiparametric imaging protocols and spectrum of appearances of histologically benign lesions. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2014;4:478–488. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.11.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposito A, De Cobelli F, Ironi G, Marra P, Canu T, Mellone R, Del Maschio A. CMR in assessment of cardiac masses: primary benign tumors. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:733–736. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stehling MK, Holzknecht NG, Laub G, Böhm D, von Smekal A, Reiser M. Single-shot T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the heart with black blood: preliminary experience. MAGMA. 1996;4:231–240. doi: 10.1007/BF01772011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simonetti OP, Finn JP, White RD, Laub G, Henry DA. "Black blood" T2-weighted inversion-recovery MR imaging of the heart. Radiology. 1996;199:49–57. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kübler D, Gräfe M, Schnackenburg B, Knosalla C, Wassilew K, Hassel JH, Ivanitzkaja E, Messroghli D, Fleck E, Kelle S. T1 and T2 mapping for tissue characterization of cardiac myxoma. Int J Cardiol. 2013;169:e17–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasser SB, Doeblin P, Doltra A, Schnackenburg B, Wassilew K, Berger A, Gebker R, Bigvava T, Hennig F, Pieske B, Kelle S. Cardiac Myxomas Show Elevated Native T1, T2 Relaxation Time and ECV on Parametric CMR. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:602137. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.602137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motwani M, Kidambi A, Herzog BA, Uddin A, Greenwood JP, Plein S. MR imaging of cardiac tumors and masses: a review of methods and clinical applications. Radiology. 2013;268:26–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carson W, Chiu SS. Image in cardiovascular medicine. Eustachian valve mimicking intracardiac mass. Circulation. 1998;97:2188. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Amato N, Pierfelice O, D'Agostino C. Crista terminalis bridge: a rare variant mimicking right atrial mass. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:444–445. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKay T, Thomas L. 'Coumadin ridge' in the left atrium demonstrated on three dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:298–300. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyer CM, Kagel T, Lemburg SP, Bauer TT, Nicolas V. Lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum: a prospective study of incidence, imaging findings, and clinical symptoms. Chest. 2003;124:2068–2073. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaitkus PT, Barnathan ES. Embolic potential, prevention and management of mural thrombus complicating anterior myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90409-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dooms GC, Higgins CB. MR imaging of cardiac thrombi. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeGroat TS, Parameswaran R, Popper PM, Kotler MN. Left ventricular thrombi in association with normal left ventricular wall motion in patients with malignancy. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:827–828. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)91160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elen E, D'Angelo T, Tjubandi A, Raharjo SB. A rare case of superior vena cava lipoma: its presentation from non-invasive examination. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:1183. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jez085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jungehülsing M, Sechtem U, Theissen P, Hilger HH, Schicha H. Left ventricular thrombi: evaluation with spin-echo and gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;182:225–229. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D'Angelo T, Mazziotti S, Inserra MC, De Luca F, Agati S, Magliolo E, Pathan F, Blandino A, Romeo P. Cardiac Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e009443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.009443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visser CA, Kan G, Meltzer RS, Dunning AJ, Roelandt J. Embolic potential of left ventricular thrombus after myocardial infarction: a two-dimensional echocardiographic study of 119 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:1276–1280. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sparrow PJ, Kurian JB, Jones TR, Sivananthan MU. MR imaging of cardiac tumors. Radiographics. 2005;25:1255–1276. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pazos-López P, Pozo E, Siqueira ME, García-Lunar I, Cham M, Jacobi A, Macaluso F, Fuster V, Narula J, Sanz J. Value of CMR for the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:896–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spuentrup E, Mahnken AH, Kühl HP, Krombach GA, Botnar RM, Wall A, Schaeffter T, Günther RW, Buecker A. Fast interactive real-time magnetic resonance imaging of cardiac masses using spiral gradient echo and radial steady-state free precession sequences. Invest Radiol. 2003;38:288–292. doi: 10.1097/01.RLI.0000064784.68316.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paydarfar D, Krieger D, Dib N, Blair RH, Pastore JO, Stetz JJ Jr, Symes JF. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging and surgical histopathology of intracardiac masses: distinct features of subacute thrombi. Cardiology. 2001;95:40–47. doi: 10.1159/000047342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LE ROUX BT. Pericardial coelomic cysts. Thorax. 1959;14:27–35. doi: 10.1136/thx.14.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoller JK, Shaw C, Matthay RA. Enlarging, atypically located pericardial cyst. Recent experience and literature review. Chest. 1986;89:402–406. doi: 10.1378/chest.89.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis RD Jr, Oldham HN Jr, Sabiston DC Jr. Primary cysts and neoplasms of the mediastinum: recent changes in clinical presentation, methods of diagnosis, management, and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sechtem U, Tscholakoff D, Higgins CB. MRI of the abnormal pericardium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:245–252. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verhaert D, Gabriel RS, Johnston D, Lytle BW, Desai MY, Klein AL. The role of multimodality imaging in the management of pericardial disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:333–343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.921791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parmar YJ, Shah AB, Poon M, Kronzon I. Congenital Abnormalities of the Pericardium. Cardiol Clin. 2017;35:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah BN, Babu-Narayan S, Li W, Rubens M, Wong T. Severe mitral annular calcification: insights from multimodality imaging. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41:245–247. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-12-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caduff JH, Hernandez RJ, Ludomirsky A. MR visualization of aortic valve vegetations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:613–615. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199607000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dursun M, Yilmaz S, Ali Sayin O, Olgar S, Dursun F, Yekeler E, Tunaci A. A rare cause of delayed contrast enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: infective endocarditis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:709–711. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000177520.02175.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doherty NE, Siegel RJ. Cardiovascular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am Heart J. 1985;110:1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kono T, Koide N, Hama Y, Kitahara H, Nakano H, Suzuki J, Isobe M, Amano J. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in cardiac myxoma: a study of fifteen patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(00)70223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colin GC, Dymarkowski S, Gerber B, Michoux N, Bogaert J. Cardiac myxoma imaging features and tissue characteristics at cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:950–951. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colin GC, Gerber BL, Amzulescu M, Bogaert J. Cardiac myxoma: a contemporary multimodality imaging review. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;34:1789–1808. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1396-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carney JA. Carney complex: the complex of myxomas, spotty pigmentation, endocrine overactivity, and schwannomas. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:90–98. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(05)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, Mehta NJ, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: a comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J. 2003;146:404–410. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Syed IS, Feng D, Harris SR, Martinez MW, Misselt AJ, Breen JF, Miller DV, Araoz PA. MR imaging of cardiac masses. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:137–164, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelle S, Chiribiri A, Meyer R, Fleck E, Nagel E. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Papillary fibroelastoma of the tricuspid valve seen on magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2008;117:e190–e191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cannavale G, Francone M, Galea N, Vullo F, Molisso A, Carbone I, Catalano C. Fatty Images of the Heart: Spectrum of Normal and Pathological Findings by Computed Tomography and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5610347. doi: 10.1155/2018/5610347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, Green CE, Galvin JR. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:1073–103; quiz 1110. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oshima H, Hara M, Kono T, Shibamoto Y, Mishima A, Akita S. Cardiac hemangioma of the left atrial appendage: CT and MR findings. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18:204–206. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200307000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tao TY, Yahyavi-Firouz-Abadi N, Singh GK, Bhalla S. Pediatric cardiac tumors: clinical and imaging features. Radiographics. 2014;34:1031–1046. doi: 10.1148/rg.344135163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burke A, Virmani R. Pediatric heart tumors. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burke AP, Rosado-de-Christenson M, Templeton PA, Virmani R. Cardiac fibroma: clinicopathologic correlates and surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:862–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Günther T, Schreiber C, Noebauer C, Eicken A, Lange R. Treatment strategies for pediatric patients with primary cardiac and pericardial tumors: a 30-year review. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:1071–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghadimi Mahani M, Lu JC, Rigsby CK, Krishnamurthy R, Dorfman AL, Agarwal PP. MRI of pediatric cardiac masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:971–981. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramlawi B, David EA, Kim MP, Garcia-Morales LJ, Blackmon SH, Rice DC, Vaporciyan AA, Reardon MJ. Contemporary surgical management of cardiac paragangliomas. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1972–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martucci VL, Emaminia A, del Rivero J, Lechan RM, Magoon BT, Galia A, Fojo T, Leung S, Lorusso R, Jimenez C, Shulkin BL, Audibert JL, Adams KT, Rosing DR, Vaidya A, Dluhy RG, Horvath KA, Pacak K. Succinate dehydrogenase gene mutations in cardiac paragangliomas. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1753–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joynt KE, Moslehi JJ, Baughman KL. Paragangliomas: etiology, presentation, and management. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:159–164. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181a6de40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:219–228. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim CH, Dancer JY, Coffey D, Zhai QJ, Reardon M, Ayala AG, Ro JY. Clinicopathologic study of 24 patients with primary cardiac sarcomas: a 10-year single institution experience. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andersen RE, Kristensen BW, Gill S. Cardiac leiomyosarcoma, a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:1197–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gilkeson RC, Chiles C. MR evaluation of cardiac and pericardial malignancy. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2003;11:173–186, viii. doi: 10.1016/s1064-9689(02)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ryu SJ, Choi BW, Choe KO. CT and MR findings of primary cardiac lymphoma: report upon 2 cases and review. Yonsei Med J. 2001;42:451–456. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2001.42.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loire R, Tabib A. [Malignant mesothelioma of the pericardium. An anatomo-clinical study of 10 cases] Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1994;87:255–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mousseaux E, Meunier P, Azancott S, Dubayle P, Gaux JC. Cardiac metastatic melanoma investigated by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;16:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]