Abstract

Background:

Digital health interventions are becoming increasingly important and may be particularly relevant for paediatric palliative care. In line with the aims of palliative care, digital health interventions should aim to maintain, if not improve, psychological wellbeing. However, the extent to which the psychological outcomes of digital health interventions are assessed is currently unknown.

Aim:

To identify and synthesise the literature exploring the impact of all digital health interventions on the psychological outcomes of patients and families receiving paediatric palliative care.

Design:

Systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Data sources:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and the Midwives Information & Resource Service were searched on the 27th July 2020, in addition to the first five pages of Google Scholar. To be included in the review, papers must have contained: quantitative or qualitative data on psychosocial outcomes, data from patients aged 0–18 receiving palliative care or their families, a digital health intervention, and been written in English.

Results:

Three studies were included in the review. All looked at the psychological impact of telehealth interventions. Papers demonstrated fair or good quality reporting but had small sample sizes and varied designs.

Conclusions:

Despite the design and development of digital health interventions that span the technological landscape, little research has assessed their psychosocial impact in the paediatric palliative care community. Whilst the evidence base around the role of these interventions continues to grow, their impact on children and their families must not be overlooked.

Keywords: Digital health interventions, psychosocial outcomes, paediatric, palliative care, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

Digital health interventions are becoming increasingly important in paediatric and adult palliative care.

Only a small number of publications have acknowledged the need to assess the psychosocial impact of digital health interventions on paediatric palliative care patients and their families; these mostly focus on telehealth.

What this paper adds?

The small literature exploring the psychosocial impact of digital health interventions continues to focus on telehealth interventions. There is no evidence of research being published across a wider range of digital health interventions.

Published papers were disparate in the range of psychosocial outcomes assessed, had small sample sizes and varied designs.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Little research explores the psychosocial impact of digital health interventions in the paediatric palliative care community despite their growing role in accessible quality care.

Several promising conference abstracts were identified that had not yet been turned into full papers; publication of this work would help to strengthen the evidence base in this area.

Developers and regulators of digital health interventions should consider whether the psychosocial impact of new digital health interventions should be included in the assessment of efficacy and acceptability prior to implementation.

Introduction

Digital health interventions, such as electronic health records, decision support tools, mobile phone apps, wearables and social media are becoming increasingly important in improving access to, and the quality of, palliative care.1,2 As children and young people are pervasive users of technology, digital health interventions may be particularly relevant for some paediatric palliative care patients. 3

As paediatric palliative care focuses on improving the quality of life, maintaining the dignity and ameliorating the suffering of ill and dying children and their families, 4 it may be reasonable to assume that any digital health intervention used within this population should ideally improve or at least maintain current levels of psychological wellbeing.

However, in a recent systematic meta-review of evidence exploring the use of digital health interventions in palliative care, 1 few publications (n = 7) looked at the effect of digital health interventions on quality of life. Of these, only one review focusing on home telehealth included any studies related to quality of life and the provision of paediatric palliative care. 5 This review, and its recent update 6 which was also restricted to home telehealth, only found two papers7,8 that looked at the impact of digital health interventions explicitly on children receiving palliative care and/or their families.

As both of these reviews have been confined to digital health interventions providing home telehealth, the purpose of this review was to identify and synthesise the literature exploring the impact of all digital health interventions on the psychological outcomes of patients and families receiving paediatric palliative care.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was used to identify relevant research; narrative synthesis was undertaken to combine and describe the findings. Data are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline. 9 The protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020199519).

Search strategy

Six databases were searched – MEDLINE, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Midwives Information & Resource Service (MIDIRS). In addition, the first five pages of Google Scholar were searched by combining the key phrases ‘paediatric’, ‘palliative care’, ‘digital intervention’ and ‘psychosocial’. The full MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Supplemental Table 1. Searches were performed on 27th July 2020 and included titles and abstracts from the start of each database until that date. No additional search limitations were applied with regards to study type or language. The reference lists of included articles plus any relevant systematic reviews were also reviewed by the research team to ensure that no key articles were missed.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts identified in the database search were exported into EndNote, and duplicates were removed. The lead author (SA) applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see below) at the title/abstract screening stage using an excel spreadsheet. A second reviewer (NC) checked 20% of the titles and abstracts. Interrater reliability between the two reviewers was measured using Cohen’s kappa. 10 At the full text stage, both reviewers assessed each paper against the inclusion criteria and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

To be included in the review the papers must have: collected quantitative or qualitative data on psychosocial outcomes, included data from patients aged 0-18 receiving palliative care or their families, included a digital health intervention (see box 1), 11 and been written in the English language. Papers were not included if they did not distinguish between adults and children for the reporting of results, did not distinguish between palliative and non-palliative populations or were not reporting empirical research (i.e. articles that do not have a clearly defined hypothesis or research question).

Box 1. Definition of digital health intervention adapted from Hollis et al. 11 .

Digital health interventions provide information, support and therapy (emotional, decisional, behavioural and neurocognitive) for physical and/or mental health problems via a technological or digital platform (e.g. website, computer, mobile phone application (app), SMS, email, videoconferencing, wearable device)

Data extraction and quality assessment

The lead author (SA) extracted data from the included papers. A second reviewer (NC) checked this for consistency. The data extraction included Authors, Year of publication, Title, Study design, Demographic information, Setting, Intervention and Outcome data (quantitative/qualitative).

The quality of the included studies was assessed by the lead author (SA) using the Hawker Checklist 12 and checked by NC. Studies were not excluded on the basis of quality. The quality assessment was included to inform the current state of knowledge in this area.

Data synthesis

As data from the studies were heterogeneous, a meta-analysis was not appropriate. Therefore, extracted data were combined into a narrative synthesis. 13

Results

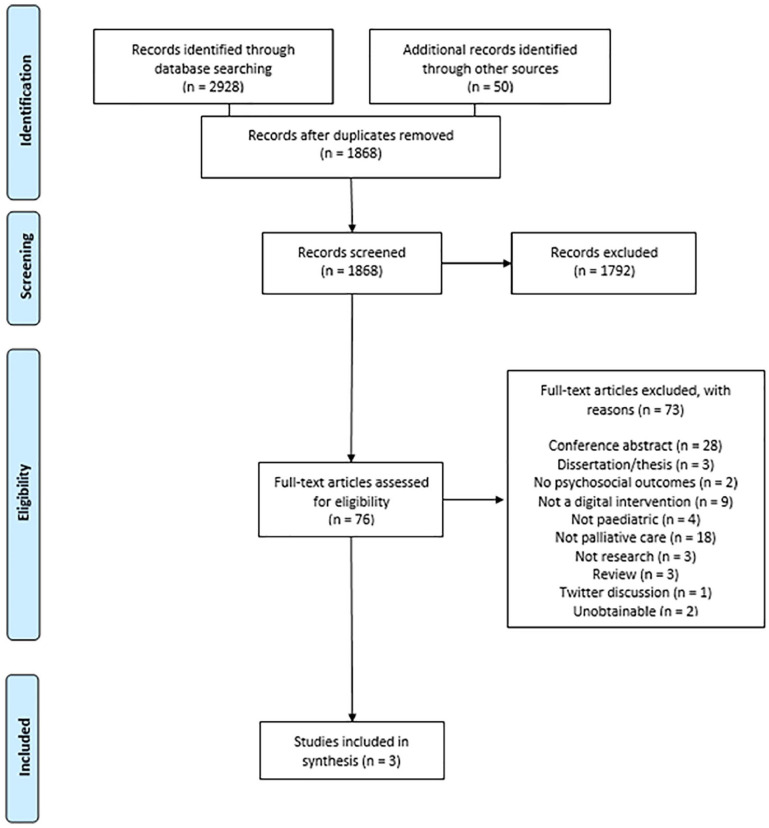

After de-duplication, the database and Google Scholar search identified 1868 titles and abstracts for initial screening; 1792 of these were removed at this stage as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (the interrater reliability was 0.745 (p < 0.001)). Of the 76 full text articles reviewed, 73 were excluded (reasons are presented in Figure 1). Two additional relevant systematic reviews14,15 were identified and their references checked – no additional papers were identified. Three papers7,8,16 met the inclusion criteria and have been synthesised below.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of studies included in the systematic review.

Characteristics of the three studies are shown in Table 1. The papers were from Australia, 7 UK 8 and USA 16 and were published in 2012, 2016 and 2020 respectively. A total of 61 patient/family caregivers participated. The studies were set in a paediatric palliative care service, 7 three children’s hospices, 8 and a home hospice, 16 The papers reported varied study designs, including a prospective exploratory cohort study, 7 a longitudinal mixed methods evaluation 8 and a two time-point longitudinal case series study. 16 The papers were rated as either fair 7 or good quality.8,16

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 3).

| Authors | Date | Country | Study design | Study aim | Tool used | Intervention description | Setting | Participants | Relevant outcome measures | Findings | Quality score 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradford et al. 7 | 2012 | Australia | Prospective exploratory cohort study | To evaluate the home telehealth programme (HTP) which included measuring feasibility, acceptability, parental and clinician satisfaction with care, and caregiver quality of life. | Logitech Vid (video), standard telephone (audio) | The HTP is used to provide specialist consultations directly to patients and their caregivers in the family home, consultations that families may not otherwise receive because of the distance between the family home and the hospital. HTP consultations involve symptom management, changes in patient condition and subsequent management options, as well as the provision of emotional support to caregivers. | One paediatric palliative care service (PPSC) based within a Children’s hospital in Australia | Fourteen primary caregivers of patients referred to, and expected to be cared for by, the paediatric palliative care service for the duration of their palliative care | Quality of Life in Life Threatening Illness-Family (QOLLTI-F) instrument | Following a 10 week intervention period, the descriptive analysis of the quality-of-life data that was collected showed no differences in QOLLTI-F scores between caregivers in control and intervention groups. | Fair (27/36) |

| Harris et al. 8 | 2016 | UK | Longitudinal, multisite mixed methods evaluation | To evaluate the use of MyQuality within a children’s hospice population by assessing acceptability of the tool and patterns of usage, exploring families’ perceptions of the tool and measuring self-scored levels of family empowerment. | Bespoke website (my-quality.net) | MyQuality allows families to identify, describe, prioritise and monitor the issues that most impact on their quality of life, and to share this information with their health and social care team. The tool can be accessed via the internet and is free of charge. The data entered, and access to that data, is controlled by the patient/carer. The child’s nominated key professionals can be given access to their graphs, and trigger points can be set up to instigate early review of symptoms that fall outside set limits. | Three non-National Health Service children’s hospices in the UK | Thirty-two families who attended the hospice and had no immediate events making an invitation inappropriate (such as imminent death, social or other personal issues). | Family empowerment scale (FES), semi structured interviews about their views of the intervention | Mean scores increased over the 3 month time period (3.45–3.85) and showed a significant increase (p ⩽ 0.01) overall, and across all but the community domain whether all or only paired data were compared. Themes from qualiative data consisted of: Acceptability of use of website; empowerment; communication; and clinical value. Families who had used the tool had felt that it had helped give them a voice and given them some control over access to their personal information. There was evidence that some families perceived a significant shift in power during consultations, enabling them to share information and communicate about issues affecting their current QOL. | Good (30/36) |

| Weaver et al. 16 | 2020 | USA | Two time point, longitudinal case series study | Determine whether telehealth inclusion of a familiar paediatric palliative care provider during the first two home-based hospice visits was acceptable to children, families, and adult-trained home hospice nurses in rural settings. | Zoom videoconferencing/FaceTime | The telehealth intervention included a hospital-based palliative care provider familiar to the family partnering with a rural, adult-trained home hospice nurse for the nurse’s first two visits to the child’s home after discharge from the free-standing children’s hospital. Each study participant received a standard of care in person visit with a home hospice nurse from an adult-trained hospice team within 48 h of arrival to home after hospital discharge. The study intervention was the additional presence of the inpatient paediatric palliative care physician who had been following the child during hospitalisation and then joining the home hospice nurse’s in-person visit as a telehealth presence using a FaceTime screen. The same intervention occurred on day 14 at home. | Home hospice in rural Midwest, USA | Fifteen children aged 0–18 years, their family caregivers and nurses referred to the hospital-based paediatric palliative care team at the free-standing children’s hospital, and enrolling on home hospice services within a rural zip code in the state of Nebraska at the time of discharge from the hospital. | Open-text comment box for paediatric-age hospice recipients to record their perspective on telehealth visits | Themes from qualitative data consisted of: Being remembered (child reports liking the feeling of not being forgotten by hospital staff); medical knowledge and care planning (child values anticipatory symptom management, discussing medical questions, and reviewing the care plan together; comfort of home (child cherishes the cosiness and comforts of home over the hospital; being known (child appreciates the personalised care available through familiarity and shared history); continuity and introduction (child welcomes new care team member in context of formative introduction and information-sharing); and peace of mind (child finds assurance in the family caregiver and nurse receiving shared education for confidence in ongoing care). | Good (30/36) |

Two studies7,16 explored how remote consultations might improve patient/carer/clinician communication. The first study 7 focused on a programme for patients and their primary care givers delivered via video link and telephone. All patients received usual care; those in the intervention group received supplementary telehealth consultations with hospital staff. The second study 16 focused on a telehealth intervention delivered via Zoom videoconferencing/FaceTime for patients and their caregivers who lived in a rural part of Nebraska, USA. Patients received their standard in-person visits from the home hospice nurse with the additional online presence of the inpatient paediatric palliative care physician from their hospital admission. The remaining study 8 evaluated the psychosocial impact of using a bespoke website (My-Quality.net) to collect data on patient reported outcomes. Data recorded via the website by patients and families could be shared with the clinical team to identify, describe, prioritise and monitor the issues that most impact on quality of life.

Studies collected data on caregivers’ quality of life (quantitative), 7 family empowerment (quantitative), 8 and general feedback (qualitative).8,16 The two interventions based on remote consultations described differing impact on psychosocial outcomes.7,16 The first study reported no differences in quality of life between caregivers in control and intervention groups over a 10-week period. 7 The second study reported an increased sense of identity and peace of mind in paediatric patients following two sequential telehealth visits. 16 The results from the MyQuality intervention showed a significant improvement in family empowerment over a 3-month period and increased feelings of control. 8

Discussion

Whilst a broad range of digital health interventions are becoming widely used in paediatric palliative care, only three papers, all focusing on telehealth interventions, explore their psychosocial impact. A single paper, 16 published in 2020, was added to those previously identified in existing systematic reviews.5,6 Despite the positive psychosocial impact reported in two of the three studies,8,16 the findings are disparate due to the diverse nature of the interventions. This, combined with small sample sizes and varied research designs, limits the conclusions we are able to draw about the psychosocial impact of digital health interventions and the mechanisms involved.

Whilst a recent systematic review had primed us to expect that digital health interventions for palliative care were being described but not evaluated in the published academic literature, 17 the absence of any additional papers outside of the telehealth domain was particularly surprising. Despite the design and development of digital health interventions that span the technological landscape, from mobile phone apps 18 to virtual reality, 19 it appears no research has yet been published that reports studies assessing their psychosocial impact in the paediatric palliative care community.

Whilst our strict inclusion criteria (such as the need for papers to focus explicitly on the paediatric palliative care setting or separate other results from the paediatric palliative care population) may have limited the number of papers that were included in this review, other factors leading to the low number of publications in this area must be considered. We found a relatively large number of conference abstracts (n = 28) that had not yet been turned into full publications. This is consistent with other systematic reviews in this topic area 17 and some have reasoned that publication is a low priority among clinical time pressures, 20 despite calls for clinicians to contribute to evidence-based care. 21

Whilst there is growing evidence surrounding the benefits of using digital health interventions to improve the access to and quality of paediatric palliative care,1,2 further research establishing that digital technologies are maintaining or improving the psychological wellbeing of children and young people is required. In terms of policy, we must consider whether the psychosocial impact of new digital health interventions should be included in the assessment of efficacy and acceptability, typically required to meet digital service standards such as those published by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence in England 22 and other governing and regulatory bodies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211026523 for The impact of digital health interventions on the psychological outcomes of patients and families receiving paediatric palliative care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Stephanie Archer, Natalie H.Y. Cheung, Ivor Williams and Ara Darzi in Palliative Medicine

Footnotes

Authorship: SA & IW contributed towards designing the review, SA & NC contributed to the data analysis and synthesis; all authors contributed to the drafting and editing the manuscript and gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SA is the Director of Cheung & Archer Limited – a research consultancy company focusing on health and social care research.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this project was provided by a grant from Fondazione Isabella Seràgnoli to the Institute of Global Health Innovation at Imperial College London.

Research ethics and patient consent: Ethical approval was not sought for this systematic review of the published literature.

ORCID iD: Stephanie Archer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1349-7178

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1349-7178

Data management and sharing: All data included in this paper are reported within the manuscript.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Finucane AM, O’Donnell H, Lugton J, et al. Digital health interventions in palliative care: a systematic meta-review. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4(1): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Payne S, Tanner M, Hughes S. Digitisation and the patient–professional relationship in palliative care. Palliat Med 2020; 34(4): 441–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devine KA, Viola AS, Coups EJ, et al. Digital health interventions for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2018; 2: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, et al. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(17): 1752–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bradford N, Armfield NR, Young J, et al. The case for home based telehealth in pediatric palliative care: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2013; 12(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holmen H, Riiser K, Winger A. Home-based pediatric palliative care and electronic health: systematic mixed methods review. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22(2): e16248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradford N, Young J, Armfield NR, et al. A pilot study of the effectiveness of home teleconsultations in paediatric palliative care. J Telemed Telecare 2012; 18(8): 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris N, Beringer A, Fletcher M. Families’ priorities in life-limiting illness: improving quality with online empowerment. Arch Dis Child 2016; 101(3): 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960; 20(1): 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, et al. Annual research review: digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017; 58(4): 474–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(9): 1284–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, vol. 1. Lancaster University, 2006, p.b92. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ostherr K, Killoran P, Shegogg R, et al. Death in the digital age: a systematic review of information and communication technologies in end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2016; 19(4): 408–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peat G, Rodriguez A, Smith J. Social media use in adolescents and young adults with serious illnesses: an integrative review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019; 9(3): 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weaver MS, Robinson JE, Shostrom VK, et al., Telehealth acceptability for children, family, and adult hospice nurses when integrating the pediatric palliative inpatient provider during sequential rural home hospice visits. J Palliat Med 2020; 23(5): 641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hancock S, Kaufman MS. Telehealth in palliative care is being described but not evaluated: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2019; 18(1): 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brock KE, Wolfe J, Ullrich C. From the child’s word to clinical intervention: Novel, new, and innovative approaches to symptoms in pediatric palliative care. Children 2018; 5(4): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niki K, Okamoto Y, Maeda I, et al. A novel palliative care approach using virtual reality for improving various symptoms of terminal cancer patients: a preliminary prospective, multicenter study. J Palliat Med 2019; 22(6): 702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanchanale S, Kerr M, Ashwood P, et al. Conference presentation in palliative medicine: predictors of subsequent publication. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018; 8(1): 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. Am Psychol 2008; 63(3): 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. NICE, 2019, https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211026523 for The impact of digital health interventions on the psychological outcomes of patients and families receiving paediatric palliative care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis by Stephanie Archer, Natalie H.Y. Cheung, Ivor Williams and Ara Darzi in Palliative Medicine