Abstract

Purpose of review:

Supportive care services have evolved overtime to meet the growing supportive care need of patients with cancer and their families. In this review, we summarize existing definitions of supportive care, highlight empiric studies on supportive care delivery, and propose an integrated conceptual framework on supportive cancer care.

Recent findings:

Supportive care aims at addressing the patients’ physical, emotional, social, spiritual and informational needs throughout the disease trajectory. Interdisciplinary teams are needed to deliver multidimensional care. Oncology teams have an important role providing supportive care in the front lines and referring patients to supportive care services such as palliative care, social work, rehabilitation, psycho-oncology, and integrative medicine. However, the current model of as needed referral and siloed departments can lead to heterogeneous access and fragmented care. To overcome these challenges, we propose a conceptual model in which supportive care services are organized under one department with a unified approach to patient care, program development and research. Key features of this model include universal referral, systematic screening, tailored specialist involvement, streamlined care, collaborative teamwork and enhanced outcomes.

Summary:

Further research is needed to develop and test innovative supportive care models that can improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: supportive care, neoplasms, organizational models, palliative care, psycho-oncology, symptom management

Introduction

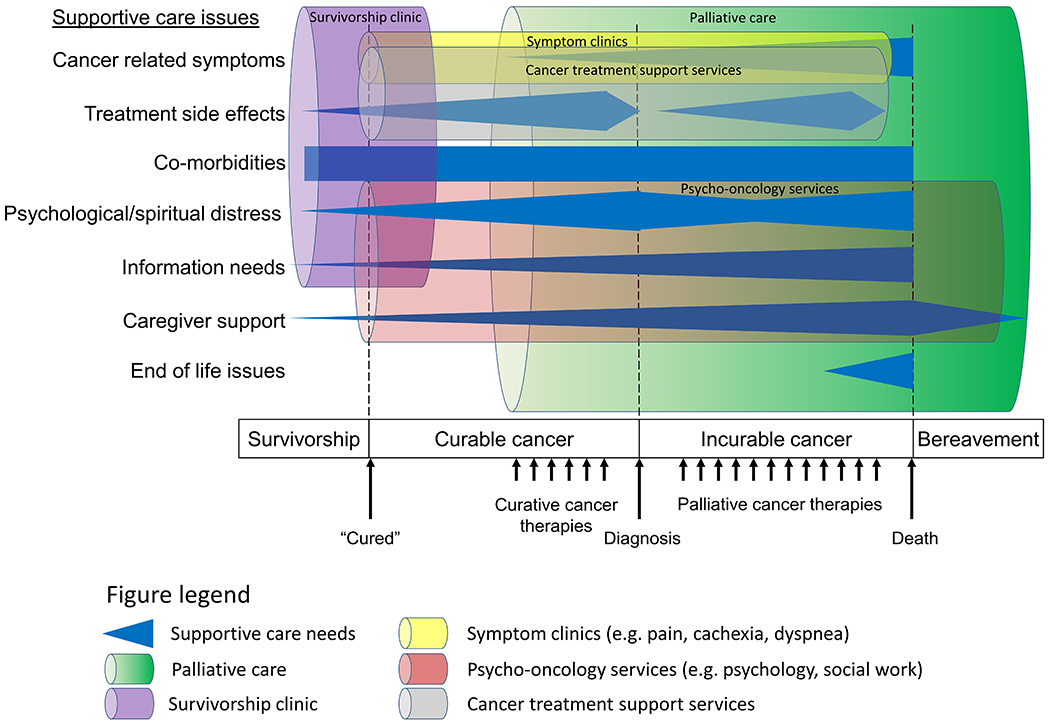

Cancer patients have significant supportive care needs throughout the disease trajectory (Figure 1).[1] Starting from the time of diagnosis, patients often present with a multitude of cancer-related symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and weight loss, along with heightened anxiety and worsened mood.[2] During treatment, patients frequently experience a myriad of adverse effects.[3] Surgery can lead to post-op pain and body image issues (e.g. ostomy). Radiation could result in inflammation acutely and fibrosis chronically. Chemotherapy is commonly associated with toxicities such as anemia, neutropenia, pain, nausea, and fatigue. Immunotherapy may contribute to immune-mediated adverse reactions. After curative therapies, patients are faced with the uncertainties of disease relapse and long term complications of cancer and its treatments. Patients on palliative therapies often eventually develop progressive disease, resulting in significant physical symptoms and emotional distress as they approach the end-of-life.[4]

Figure 1. Supportive Care Needs and Supportive Care Services throughout the cancer trajectory.

A vast majority of patients have multiple supportive care needs starting around the time of cancer diagnosis (blue horizontal shapes). These supportive care needs may vary along the disease trajectory and among patients. To address the supportive care needs of patients and their families, multiple specialized supportive care services have been developed. Examples of these services such as palliative care, cancer pain clinic, psycho-oncology teams and treatment support services are depicted here with colored cylinders. Of note, palliative care has evolved over the past decade from predominantly caring for patients at the end-of-life to earlier in the disease trajectory.

Because of the wide range of supportive care needs, multiple disciplines are involved in the delivery of supportive care, including but not limited to, advanced practice providers, chaplains, dieticians, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, pharmacists, physicians, psychologists, social workers, and volunteers.[5] These disciplines often collaborate together as part of an interdisciplinary team in a specialty supportive care service to deliver highly specialized care (Figure 1).[6] Table 1 includes several examples of specialty supportive care services.

Table 1.

Examples of Supportive Care Services

| Supportive Care Services | Focus | Disciplines |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer treatment support services | Cancer related complications and adverse effects of cancer therapies | Advanced practice providers, physicians, nurses |

| Integrative medicine | Complementary therapies | Acupuncturists, art therapists, massage therapists, music therapists, yoga therapists, physicians and others |

| Navigation programs | Information, health system navigation, community resources | Nurses, lay navigators |

| Ostomy care | Post-operative care | Nurses |

| Palliative care | Diverse needs of patients with advanced cancer | Advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, physicians, psychologists, social workers |

| Psycho-oncology services | Psychosocial care | Psychologists, psychiatrists, chaplains, social workers |

| Specialized symptom clinics | ||

| Cachexia clinic | Anorexia-cachexia | Dieticians, nurses, physicians, psychologists |

| Cancer pain clinic | Cancer pain | Physicians (pain specialists), nurses, psychologists |

| Dyspnea clinic | Dyspnea | Physicians (palliative care, pulmonologists), |

| Fatigue clinic | Cancer-related fatigue | Nurses, physicians, psychologists, physical therapists |

| Survivorship clinics | Cancer surveillance and long term toxicities | Advanced practice providers, physicians (oncologists), nurses |

Supportive care services are ever evolving to meet the growing needs of patients and their families. The aging population translates into higher incidence of cancer and multi-comorbidities. This, coupled with the fact that patients with cancer are living longer while on treatment and the increased recognition of the importance of quality of life, means that the demand for supportive care is only going to increase over time. Currently, there is much heterogeneity in how supportive care is delivered in different institutions. This is partly related to a lack of (1) standardization in how supportive care is defined, (2) limited data on empiric models for supportive care services, and (3) paucity of conceptual models on supportive cancer care delivery. A better understanding of the definitions, empiric models and conceptual framework on supportive cancer care may improve the organization and delivery of these services towards improving patient outcomes. In this review, we summarize existing definitions of supportive care, highlight empiric studies on supportive care delivery in oncology, and propose an integrated conceptual framework on supportive cancer care.

Definitions

One of the first definitions of Supportive care was proposed by Margaret Fitch: “the provision of the necessary services for those living with or affected by cancer to meet their informational, emotional, spiritual, social or physical need during their diagnostic treatment or follow-up phases encompassing issues of health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation and bereavement….”.[7,8]

A 2012 systematic review of published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks highlighted significant heterogeneity in how the term Supportive Care was defined.[9] Although many groups endorsed the broad definition above,[10,11] some had a much narrower interpretation and defined supportive care as mostly management of treatment side effects by oncology teams.[12]

Several professional organizations have also defined supportive care. With the exception of European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC), a majority have supported a broader definition.

The Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) defined supportive care in cancer as “the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment. This includes management of physical and psychological symptoms and side effects across the continuum of the cancer experience from diagnosis through treatment to post-treatment care. Enhancing rehabilitation, secondary cancer prevention, survivorship, and end-of-life care are integral to supportive care.”[13]

In a 2017 position paper, the European Society of Medical Oncology cited the MASCC definition above and proposed the term ‘patient-centered care’ to encompass both supportive and palliative care.[14]

In a 2009 white paper on standard and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe, the EAPC stated that supportive care is “the prevention and management of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment. This includes physical and psychosocial symptoms and side-effects across the entire continuum of the cancer experience, including the enhancement of rehabilitation and survivorship. There is considerable overlap and no clear differentiation between the use of the terms ‘palliative care’ and ‘supportive care’.” Paradoxically, it then stated that “However, most experts agree that supportive care is more appropriate for patients still receiving antineoplastic therapies and also extends to survivors, whereas palliative care has its major focus on patients with far advanced disease where antineoplastic therapies have been withdrawn… Supportive care should not be used as a synonym of palliative care. Supportive care is part of oncological care, whereas palliative care is a field of its own extending to all patients with life-threatening disease.”[15]

National Cancer Institute (NCI) dictionary defined supportive care as “care given to improve the quality of life of patients who have a serious or life-threatening disease. The goal of supportive care is to prevent or treat as early as possible the symptoms of a disease, side effects caused by treatment of a disease, and psychological, social, and spiritual problems related to a disease or its treatment. Also called comfort care, palliative care, and symptom management.”[16]

Empiric Models of Supportive Care

Multiple groups have published their supportive care clinical service model. A large number of these supportive care programs were variations of outpatient palliative care clinics delivered by palliative care teams.[17–19] Because a large proportion of oncologists perceived palliative care be to associated with end-of-life,[20,21] the palliative care clinic at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center changed its name to Supportive Care in 2007 as a re-branding effort to overcome the stigma. This name change to “Supportive Care” was associated with significant increase in outpatient palliative care referrals in a before-after name change comparison.[22] Indeed, the number of NCI-designated cancer centers in the US that adopted the program name supportive care increased from 10% to 35% between 2009 and 2018.[23,24] Among ESMO-designated cancer centers of integrated palliative are and oncology, over 50% carried the name “supportive care” or “supportive and palliative care”.[25] In the United Kingdom, Christie NHS Foundation trust has used the term “Enhanced Supportive Care” for their expanded palliative care service.[26] Because supportive/palliative care empiric models have been discussed extensively elsewhere, this review will focus on other variations of supportive care services.

An important aspect of supportive care is the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms. Although this role is traditionally assumed by oncologists, a number of centers have developed specialized cancer treatment support services to consolidate this aspect of care. Sherman et al. described their interdisciplinary supportive care service for patients with myeloma undergoing stem cell transplant.[27] Viklund et al. also reported their experience with nurse specialist led supportive care service for patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers.[28] These programs involved providing recommendations for symptom management, offering psycho-educational interventions and directing patients to the appropriate resources. Antonuzzo et al. ran a clinic staffed by medical oncologists, nurses, a psychologist, and a spiritual assistant to address issues related to cancer or cancer treatments. They reported a small reduction in the number of emergency room visits and unplanned hospitalizations.[29] In a retrospective series, Shih et al. reported that their nurse-led Symptom and Urgent Review Clinic reduced emergency room visits and cost of care.[30] Oatley et al. described their experience of a nurse-led supportive care program that included a telephone helpline, an urgent assessment clinic and a rapid day treatment consultation service.[31] Some supportive care clinics are highly specialized (e.g. sexual rehabilitation for patients with prostate cancer).[32]

Overlapping to a certain extent with cancer treatment support services above, patient navigators are supportive care services with a particular focus on system coordination. Howell et al. described their nurse-led community based supportive care program in Hamilton, Canada that focused on clinical case management and navigator services.[33] Modeled after the Macmillian nurse program in the United Kingdom, oncology nurses provided psychoeducation on symptom management, emotional support, information, coaching, and linkage of resources via home visits and telephone support. Villarreal-Garza et al. also described their supportive care program for young women with breast cancer that covered a range of issues, including information delivery, illness coping, fertility, and financial distress.[34]

Several integrative medicine programs have also adopted the name supportive care. For example, the Stanford Center for Integrative Medicine provides “coordinated supportive care to meet the psychosocial, nutritional and physical patient and family needs…”[35] This program included nurses, a dietitian, a social worker, an exercise physiologist, a massage therapist, a yoga instructor, a qigong instructor and healing imagery practitioner.[36] This model of supportive care has been adopted in several other countries. Kacel et al. proposed a supportive oncology collaborative visit model by integrating psycho-oncology and integrative medicine together to enhance symptom control, nutrition, physical activity, distress management, coping, treatment adherence, and patient values.[37]

Other variations of supportive care programs include a cancer pain service,[38] and a hospice care program for patients undergoing cancer treatments.[39,40]

The above empiric clinical models provide some examples of the supportive care programs in the literature and are not meant to be exclusive. They underscore the diversity of services that constitute supportive care. There are 4 important observations. First, all of the above programs shared a focus on improving patients’ quality of life, although their target patient population, team composition, setting of care, clinical scope and approach varied widely. Second, many other stand-alone programs that provide supportive care, such as cancer rehabilitation, wound care, smoking cessation and survivorship clinics were not included above simply because they rarely use the term Supportive Care in their program names. Third, several branches of supportive care, such as integrative medicine and psycho-oncology, may integrate to form to a larger, interdisciplinary supportive care service to better serve patients with multidimensional supportive care needs. Fourth, despite this trend, supportive care services appear to be fragmented and no all-encompassing supportive care service has been reported to date.

Conceptual Models of Supportive Care

Given that palliative care is sometimes considered as synonymous to supportive care, many models of supportive care in the literature tend to discuss the need for timely integration of supportive/palliative care and oncology.[6,41–43] As shown in Figure 1, palliative care addresses a wide range of supportive care needs over a wide spectrum of disease states. Conceptually, palliative care represents a main branch of supportive care; however, supportive care may also include services beyond palliative care. Supportive/palliative care models have been reviewed extensively elsewhere and will not be discussed here further.[6,41–43]

Outside of supportive/palliative care, few investigators have specifically proposed models for supportive care. Fitch et al. recommended a graded approach to supportive care, with all patients receiving a basic level of supportive care and those with greater needs gaining access to more specialized services similar to the model of primary, secondary and tertiary palliative care.[8,44] Anaissie et al. proposed an integrated care delivery model with involvement of supportive care team throughout the disease trajectory.[45]

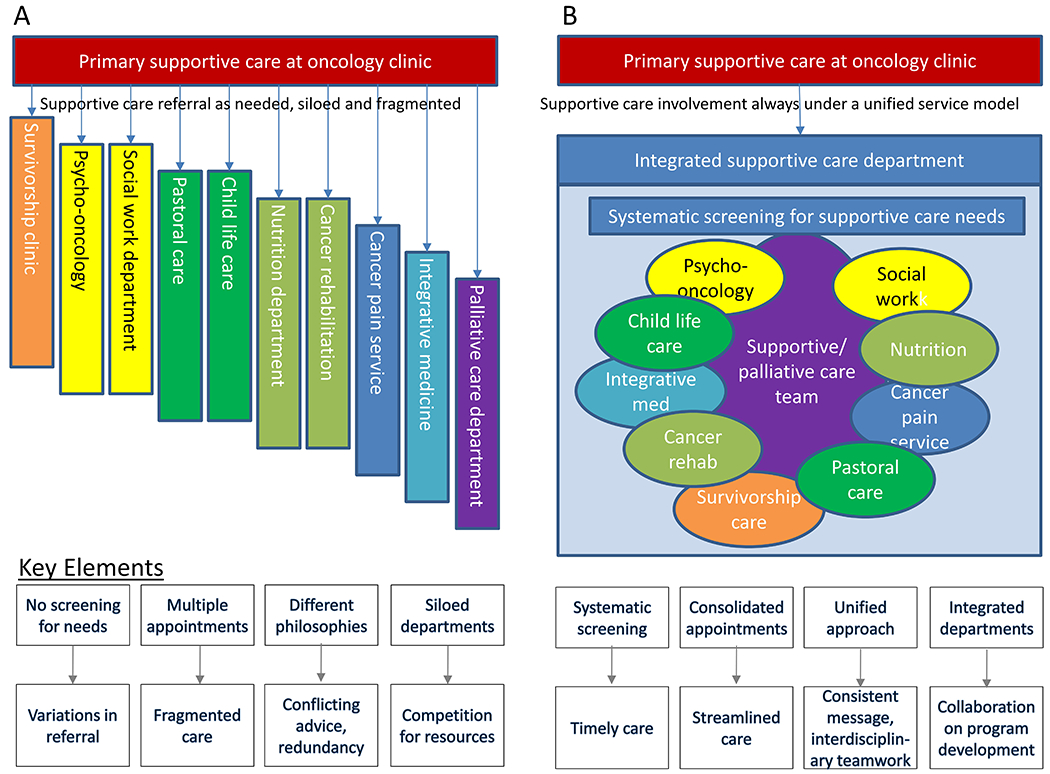

Based on the existing empiric and conceptual models, we propose an integrated framework for supportive cancer care. Figure 2a shows the current approach to supportive care. Oncologists have a critical role in the provision of supportive care in the front line and are skilled in management of cancer-related complications and cancer treatment adverse effects. They also have an important role in serious illness conversations and care planning. The oncology team may refer patients to specific supportive care service on an as needed basis, such as social work, cancer pain service, and palliative care. Although this model of care is the status quo, it has several disadvantages. First, this model puts the burden on oncology teams to recognize patients’ needs and to make the appropriate referral. Because of significant variation in practices, this could result in heterogenous utilization of supportive care services and delayed referrals. Second, this model could result in fragmented care as patients have to attend multiple clinics separated in time and space. For example, a patient with cancer pain and fatigue may be referred to the cancer pain service, fatigue clinic and palliative care at the same time. Sometimes, they may receive conflicting opinions from different team members. Third, even when members of an interdisciplinary clinic work closely together (e.g. social worker and pharmacist at a palliative care clinic), the siloed model means that they report to their own departmental manager who may have a different set of expectations and priorities. Fourth, rather than collaborating and sharing resources, different supportive care services may be competing against each other for institutional resources and advocating for their own political agenda. Given supportive care is becoming increasingly complex and diverse, this historical model of supportive care is becoming more problematic and thus re-organization is needed.

Figure 2. Conceptual Model for Supportive Care.

(A) Siloed Supportive Care Model. Currently, patients are mostly dependent on the oncology team to make referrals to various supportive care departments/services on an as needed basis, resulting in heterogenous access to specialized supportive care and fragmented care. Note that only several examples of supportive care services are shown here and the list is not meant to be exclusive. The key concerns are shown in the bottom half leading to suboptimal outcomes. (B) Integrated Supportive Care Model. This unifying framework may overcome some of the issues in the Siloed Model. Longitudinal specialist supportive care is provided by an interdisciplinary supportive/palliative care team, with timely involvement of other teams (e.g. cancer pain service, rehabilitation) when the need arise. For patients who have completed curative treatments on surveillance, the survivorship team may be the main supportive care service instead of the supportive/palliative care team. Key features of this model include universal referral, systematic supportive care needs screening, tailored specialist involvement, streamlined care, collaborative teamwork and extended followup.

Many of the above issues can be addressed with an integrated supportive care model in which all the supportive care team members are working in the same department administratively and clinically (Figure 2b). Key features of this model include the following:

Universal referral—because all patients could benefit from supportive care service, patients are automatically referred to the Department of Supportive care starting from the time of diagnosis.

Systematic screening—at consultation and regular visits, patients will be systematically screened for their supportive care needs, which would allow the supportive care team to tailor the level of services and intensity of followup.

Tailored specialist involvement—under this unified framework, specialist supportive care is provided by an interdisciplinary supportive/palliative care team longitudinally, with timely involvement of other teams (e.g. cancer pain service, rehabilitation) when the need arise. For patients who have completed curative treatments on surveillance, the survivorship team may be the main supportive care service instead of the supportive/palliative care team.

Collaborative teamwork—because supportive care involves a large number of disciplines, this consolidated administrative and clinical setup would facilitate communication and collaboration among interdisciplinary team members. Under a model of situational leadership, each discipline may contribute their unique expertise.

Streamlined care—patients can receive a variety of supportive care services all in one setting with less wait time or duplication. Moreover, closer communication among team members means that patients are more likely to receive a consistent message.

Consolidated leadership—administratively, this consolidated model would allow the institution to better advance its supportive care priorities, and promote development of innovative interdisciplinary initiatives to improve patient outcomes.

Improved outcomes—this effort has the potential to enhance timely access to patient-centered supportive care, improved patient outcomes, while reducing cost by removing redundancy (e.g. pain and palliative care both seeing patient).

Summary

Patients with cancer have significant supportive care needs throughout the disease trajectory. Oncology teams have an important role delivering supportive care in the front lines. Because of the focus on cancer therapies, the limited clinic time, and the lack of interdisciplinary staffing, it is not possible for oncology teams alone to address all the patients’ supportive care needs. Thus, many patients would benefit from referral to specialty supportive care services, such as palliative care, psycho-oncology, cancer rehabilitation, and integrative medicine. However, the current model of as needed referral to supportive care services can lead to uneven access. Moreover, the segmented and siloed approach means that patients have to see multiple providers separated in time and space, with the potential for overlapping/redundant roles, conflicting messages, and competition rather than collaboration among the different supportive care departments. Here, we propose a conceptual model in which supportive care services are organized under one department with a unified approach to patient care, program development and research. As supportive care continues to evolve to meet the growing demand, more research is needed to identify optimal models of care to better support the multidimensional care needs of patients with cancer and their families.

Key points:

Patients with cancer have significant supportive care needs throughout the disease trajectory.

Supportive care services need to continue to evolve to meet the growing needs of patients and their families.

Oncology teams have an important role delivering supportive care in the front lines and making referral to various supportive care services such as palliative care, psychooncology and integrative medicine.

Currently, patients are mostly dependent on the oncology team to make referrals to various supportive care departments/services on an as needed basis, resulting in heterogenous access to specialized supportive care and fragmented care.

We propose an integrated model in which all supportive care services are organized under one department with a unified approach to patient care, program development and research.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr. Angelique Wong for helpful discussions.

Financial support and sponsorship:

None

Funding support:

Dr. Hui reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (R01CA214960-01A1; R01CA225701-01A1; R01CA231471-01A1).

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: No relevant disclosure

Conflicts of interest:

None

References

- 1.Hui D: Definition of supportive care: Does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol 2014; 26:372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui D, Bruera E: Supportive and palliative oncology: A new paradigm for comprehensive cancer care. Hematology & Oncology Review 2013. 9:68–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M et al. Symptom and quality of life survey of medical oncology patients at a veterans affairs medical center: A role for symptom assessment. Cancer 2000; 88:1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ: A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, aids, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006; 31:58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray RE, Goel V, Fitch MI et al. Utilization of professional supportive care services by women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000; 64:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.**.Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68:356–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent review highlights the evidence and contemporary models of supportive/palliative care.

- 7.Fitch M: Providing supportive care for individuals living with cancer. Ontario Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation, Toronto: (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitch MI: Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J 2008; 18:6–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21:659–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page B: What is supportive care? Can Oncol Nurs J 1994; 4:62–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherny NI, Abernethy AP, Strasser F et al. Improving the methodologic and ethical validity of best supportive care studies in oncology: Lessons from a systematic review. In: Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27. United States (2009):5476–5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neill JE: What is supportive care and why is it important? J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2000; 17:133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Definition of supportive care: Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, Aurora, ON, Canada: (2020). https://www.mascc.org/mascc-strategic-plan [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S et al. European society for medical oncology (esmo) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in europe: Part 1. Recommendations from the european association for palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care 2009; 16:278–289. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Supportive care: National Cancer Institute, (2011). https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/supportive-care

- 17.Hannon B, Swami N, Pope A et al. The oncology palliative care clinic at the princess margaret cancer centre: An early intervention model for patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23:1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pimentel LE, De La Cruz M, Wong A et al. Snapshot of an outpatient supportive care center at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2017; 20:433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valgus J, Jarr S, Schwartz R et al. Pharmacist-led, interdisciplinary model for delivery of supportive care in the ambulatory cancer clinic setting. J Oncol Pract 2010; 6:e1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL et al. Supportive versus palliative care: What’s in a name?: A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009; 115:2013–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D, Cerana MA, Park M et al. Impact of oncologists’ attitudes toward end-of-life care on patients’ access to palliative care. Oncologist 2016; 21:1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. The Oncologist 2011; 16:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.*.Hui D, De La Rosa A, Chen J et al. State of palliative care services at us cancer centers: An updated national survey. Cancer 2020; 126:2013–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent survey reported the structures and processes of palliative care programs at US Cancer Centers.

- 24.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at us cancer centers. JAMA 2010; 303:1054–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui D, Cherny N, Latino N et al. The ‘critical mass’ survey of palliative care programme at esmo designated centres of integrated oncology and palliative care. Ann Oncol 2017; 28:2057–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enhanced supportive care–integrating supportive care in oncology: NHS, UK: (2017). https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/enhanced-supportive-care-integrating-supportive-care-in-oncology-phase-i-treatment-with-palliative-intent/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman AC, Coleman EA, Griffith K et al. Use of a supportive care team for screening and preemptive intervention among multiple myeloma patients receiving stem cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer 2003; 11:568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viklund P, Wengström Y, Lagergren J: Supportive care for patients with oesophageal and other upper gastrointestinal cancers: The role of a specialist nurse in the team. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2006; 10:353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonuzzo A, Vasile E, Sbrana A et al. Impact of a supportive care service for cancer outpatients: Management and reduction of hospitalizations. Preliminary results of an integrated model of care. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25:209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shih STF, Mellerick A, Akers G et al. Economic assessment of a new model of care to support patients with cancer experiencing cancer- and treatment-related toxicities. JCO Oncol Pract 2020; 16:e884–e892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oatley M, Fry M: A nurse practitioner-led model of care improves access, early assessment and integration of oncology services: An evaluation study. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28:5023–5029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong J, Witherspoon L, Wu E et al. Clinic utilization and characteristics of patients accessing a prostate cancer supportive care program’s sexual rehabilitation clinic. J Clin Med 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell DM, Sussman J, Wiernikowski J et al. A mixed-method evaluation of nurse-led community-based supportive cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16:1343–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarreal-Garza C, Platas A, Miaja M et al. Patients’ satisfaction with a supportive care program for young breast cancer patients in mexico: Joven & fuerte supports patients’ needs and eases their illness process. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28:4943–4951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenbaum E, Gautier H, Fobair P et al. Cancer supportive care, improving the quality of life for cancer patients. A program evaluation report. Support Care Cancer 2004; 12:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbaum E, Gautier H, Fobair P et al. Developing a free supportive care program for cancer patients within an integrative medicine clinic. Support Care Cancer 2003; 11:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kacel EL, Pereira DB, Estores IM: Advancing supportive oncology care via collaboration between psycho-oncology and integrative medicine. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27:3175–3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coyle N: Supportive care program, pain service, memorial sloan-kettering cancer center. Support Care Cancer 1995; 3:161–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esper P, Hampton JN, Finn J et al. A new concept in cancer care: The supportive care program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1999; 16:713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pienta KJ, Esper PS, Naik H et al. The hospice supportive care program: A new “transitionless” model of palliative care for patients with incurable prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996; 88:55–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruera E, Hui D: Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: Establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:4013–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hui D, Bruera E: Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Annals of palliative medicine 2015; 4:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hui D, Bruera E: Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38:852–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Gunten CF: Secondary and tertiary palliative care in us hospitals. JAMA 2002; 287:875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anaissie E, Mink T: The cancer supportive care model: A patient-partnered paradigm shift in health care delivery. . J Participat Med 2011; e26. [Google Scholar]