Abstract

Patients enter the healthcare space shouldering a lot of personal stress. Concurrently, health care providers and staff are managing their own personalstressors as well as workplace stressors. As stress can negatively affect the patient–provider experience and cognitive function of both individuals, it is imperative to try to uplift the health care environment for all. Part of the healthcare environmental psychology strategy to reduce stress often includes televisions in waiting rooms, cafeterias, and elsewhere, with the intent to distract the viewer and make waiting easier. Although well-intentioned, many select programming which can induce stress (eg, news). In contrast, as positive media can induce desirable changes in mood, it is possible to use it to decrease stress and uplift viewers, including staff. Positive media includes both nature media, which can relax and calm viewers and kindness media, which uplifts viewers, induces calm, and promotes interpersonal connection and generosity. Careful consideration of waiting room media can affect the patient–provider experience.

Keywords: stress, burnout, cognitive function, health care environment, media psychology, emotion contagion, kindness, compassion

Overview

The health care environment is a high stress experience for many patients and staff. In addition to their personal stressors, many patients have significant amounts of anxiety regarding the visit itself, including how they will be treated or if the provider will find a problem. Providers must manage their own personal stressors while providing empathy, caring, active listening, and clear thinking to patients and colleagues in a time-constrained encounter that also demands completion of required administrative tasks.

In addition to its relationship to overall patient and staff satisfaction, stress in the health care environment is important for how it affects decision-making and other executive functions (EFs) as well as how people will subconsciously spread their emotions to one another. An important aspect of the health care experience—the waiting room environment—can either exacerbate or attenuate that stress. In order to better appreciate this complex dynamic, a brief review of the impact of stress is provided accompanied by how the waiting room environment-with a focus on the effects of media—can alter the patient's and the provider's experience.

Patient and Provider Stress During a Health Care Visit

A patient entering the healthcare space does so likely shouldering a significant amount of stress or allostatic load. Even before being seated in the waiting room, a typical American is tied for fourth place as one of the most stressed citizens in the world (1). This is due to many possible stressors, including health and the cost of health care, financial hardship, interpersonal issues, discrimination, workplace stress, mass shootings, climate change, and loneliness, among many (2). Patients may also have physical stressors, including disability, pain, heavy workloads, and so on.

Any individual person, of course, can be experiencing a differential mix of these stressors at any given time. The general, population-level observation resonates with estimates of stress burden in the primary care setting, that is, that 60% to 90% of patients have emotional distress and somatization (3). This observation preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, which has markedly amplified the burden on patients, their families, and staff (4).

It is understandable, therefore, that patients will have varying degrees of tension over the visit. Patient anxiety is further augmented by whether the provider is going to say or find something untoward or that the patient would be characterized as difficult if they appear to challenge the physician (5). It is also amplified by prolonged waiting time—the perception of which can contribute to a negative outlook on the care experience by the patient and sometimes yield aggression and even violence (6–8).

A physiologic manifestation of tension is routinely visible in “white coat hypertension,” a well-recognized entity observed in 15% to 30% of patients (9). Consistent with sympathetic nervous system activation during stress, this substantial proportion of patients manifesting criteria-defined hypertension suggests that it is an underestimation of the stressed state of many others, that is, undoubtedly there are many patients who had increases in blood pressure but did not cross that threshold and thus were not labeled with this diagnosis.

Another clinical marker of anxiety is found in patients undergoing a health care procedure. For example, approximately 25% of patients coming to a dentist have moderate to severe anxiety, which is often accompanied by increased gagging (10), need for greater anesthetic (11) and more operatory time. Similar observations have been made in other specialities (12,13), likely driven by heightened sympathetic activation with a decreased tolerance for pain (14).

Health care providers also shoulder a lot of stress. On top of many of the same stressors experienced by the general population, they must cope with multiple, concurrent demands and provide support to patients who need compassion in a time-constrained environment. Added demands such as electronic health records create a classic workplace stress of high workloads and low control (15). That providers have burnout, depression and suicide rates twice that of the general public (16–19) is a predictable consequence of these large allostatic loads. Evidence of that pressure in day-to-day interactions is found in the median time to interrupt the patient discussing their agenda: 11 s (20). It is also found in the higher rates of errors in overly stressed physicians (21,22).

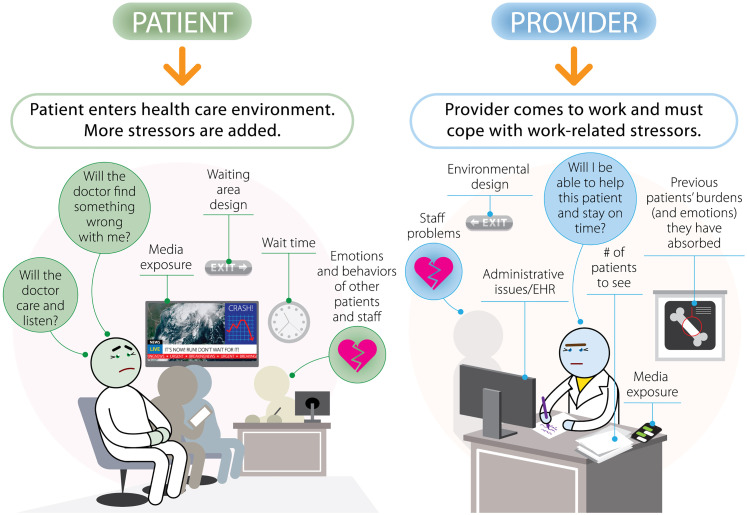

Figure 1 depicts an integrated view of some of the manifold situational and environmental stressors that patients and providers (including staff) may be experiencing in a health care office. For any individual on a specific day, the differential mix of these stressors may vary. For example, a patient may enter shouldering a particular personal problem and is worried about their health. Added to this, the provider may be running late, prolonging the patient's wait time. Other potential stressors, such as the behavior of other patients and staff as well as the clinic environment can impact them. Although these may be separated into individual issues, nonetheless they are integrated in a holistic sense of how stressed someone feels, with many of these effects being subconscious.

Figure 1.

Both patients and providers come to the health care setting with their own personal stressors, including finances, health, discrimination, among many others. In the health care setting, additional stressors are potentially imposed, as shown. One of those is how media and other environmental factors will affect them, often subconsciously. The providers will be burdened by a heavy workload in a time-constrained encounter. They will undoubtedly feel the pressure to stay on time and manage their workloads as well as be affected by interactions with staff and other patients. Finally, they likely have had some media exposure during the day, even briefly.

What makes this a (more) complex dynamic is that negative emotions and mood (eg, sadness, anxiety, anger) from one cause can spillover onto other issues for that same person. Those other issues can appear worse than they might otherwise under more relaxed conditions, an effect termed “mood congruence.” For example, in the presence of other stressors (eg, a family issue, an unengaged (emotionally cold) staff member), an additional stressor, such as waiting time, is assessed more negatively that it otherwise might have been.

All of these considerations (and more) apply to the provider and office staff, too, as shown in Figure 1. In particular, the provider must be able to adhere to the schedule yet manage a diverse array of issues and be able to actively listen, show caring, and provide an integrated and organized plan while trying to complete the patient's records in a time-constrained encounter.

Media Use As A Distraction

One of the causes or triggers of negative mood in health care can be the media that is displayed in the waiting room, hallways, and elsewhere. Many waiting areas use a television as a distraction. The well-intentioned idea is to occupy the patient and allow the wait to pass more easily.

Very often practices choose commercially available cable programming, such as home and garden or a network that has a mix of talk shows, news, commercials, and so on or sometimes just news. Alternatively, some medical and dental offices may display educational material, services offered at the practice, and occasionally nature media (23).

What can be overlooked is that media has a rapid and often profound impact on viewers. For those waiting rooms still showing the news (as all or part of its programming), it is critical to recognize that negative news can rapidly induce stress, anxiety, and fear (24,25). A news story about a distant war can also induce mood congruence, wherein the mood created by the news can amplify anxiety about the viewer's personal life issues or the upcoming visit.

And although neutral programming, such as home and garden shows, may be distracting, neutral media may be boring (26). Perhaps thought of as innocuous entertainment, boredom may be mildly-to-moderately stressful, especially when induced in people prone to boredom. Exemplifying its stress induction potential, chronic boredom is associated with increased incidence of disease and death (27). Finally, while educational materials and practice offerings maybe valuable, some patients and visitors may react with fear induction.

Thus, negative (and even neutral) media can instigate a stress response as well as augment the perception of, or reaction to, other stressors in what is likely a vicious cycle. As media is a potent and yet readily changeable aspect of the office experience, it is worthy of attention.

Consequences of Stress on Cognitive Function and Communication During a Health Care Visit

Some may view the stress experienced by both patients and providers (including staff) as a natural consequence of the health care environment that needs to be acknowledged and regrettably accepted. This passive acceptance disregards its potential impact. Beyond the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and triggering an inflammatory response, an immediately relevant consequence for that person is that stress also affects cognitive function and behavior that would be critical to patient engagement, activation, and success.

Stress rapidly impairs executive function (EF), the top-down mental processes that are critical for paying attention, assimilating new information, and making decisions (28). Contrasted to more automatic or habitual responses, the 3 core EFs include inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. From these core EFs spring problem-solving, reasoning, and planning/organization (29).

Inhibitory control includes the ability to pay attention and focus, such as what the health care provider is saying. Inhibitory control also describes the ability to inhibit a premature conclusion or to restrain undesirable behaviors, such as overeating. Working memory involves holding information in mind and mentally working with it, such as internalizing information from the provider regarding what a patient needs to do.

Finally, cognitive flexibility is the ability to change perspective or point-of-view. Localized in the prefrontal cortex (29), cognitive flexibility uses inhibitory control and working memory to allow for a shift in perspective (“what if I tried something this way?”) or facilitate empathy (“how does the other person feel?”). Adaptability and creativity depend on cognitive flexibility.

As stress disrupts EFs, it impairs decision-making and problem solving in both humans and animals (30,31). When experienced chronically, stress manifests in changes in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex (32) emphasizing that stress has significant biological ramifications.

With impaired decision-making, both humans and animals default to more habitual decision-making processes (such as food choices) (33) or are less able to assimilate and process new information (30,33). Avoidance behavior can also arise as a coping mechanism to avoid any additional stressors (34,35) perhaps explaining, at least in part, why over 80% of patients do not disclose key pieces of information, such as about their diet, exercise, taking medication, and so on (36).

In the Exam (Hospital) Room

Let us reconsider the patient–provider encounter focusing on the emotional states of both parties. Our prototypic patient may have active medical problems, is often older with perhaps mild cognitive decline, and may take multiple medications. His or her health care provider has a heavy schedule of patients allotted 15 to 20 min each to acquire follow up information, address new problems, and create, explain, and document a forward plan.

The integrated allostatic load our patient carries into the exam room impedes concentration and engagement. They likely respond more slowly than desired. Our provider, burdened by their own issues and under pressure from time constraints and charting requirements can be strained further by patients who respond with a slow cadence, compelling interruption. Their respective stressors and circumstances will most likely make it harder to listen to one another, process new information, and make decisions.

Another factor complicating this interaction is that emotions are contagious (37–40). Patients who are stressed, anxious, fearful, or angry can spread it to the provider (and staff), who can also spread it to other patients (41) and likely staff. This is a well-described, subconscious process (38,39); both parties likely affect each other without realizing it. Beyond the technical and transactional aspects of medicine, providers, as well as all of the staff, need to emotionally manage the issues of multiple patients and can spread both negative and positive emotions back to the patients.

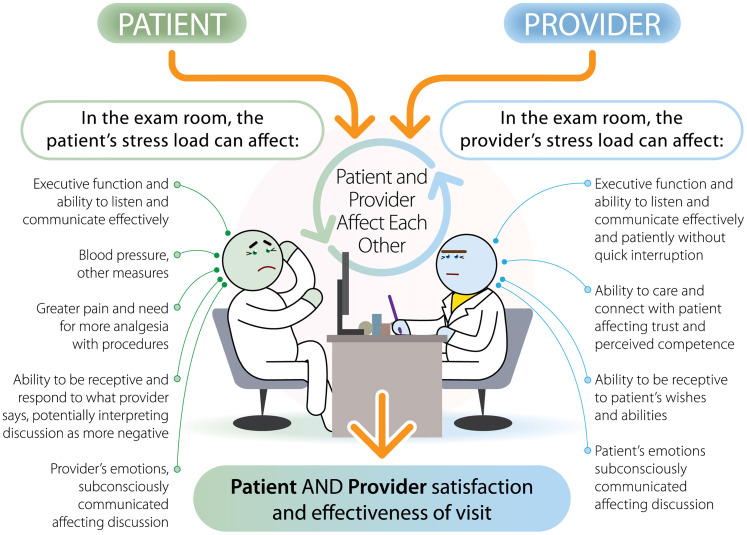

An integrated view of the examination room interaction is depicted in Figure 2. What is particularly important is how their respective stressors will affect their thinking and behavior, followed by how each party will affect the other. And because of mood congruence, a more negative affect will drive a more severe interpretation of events and interactions, amplifying the perceived negative aspects of the care experience.

Figure 2.

The patient and provider enter the encounter, each being differentially affected by their own stressors. The weight of those stressors will influence how well they can listen and communicate with one another. Listening is a key aspect for the patient demonstrating that the provider cares about them, creating trust and greater patient engagement. In addition, the emotional state of each is affecting the other. A more negative mood of one party will affect the other and likely create a vicious cycle. Conversely, a more positive mood can positively affect the quality of that interaction.

There is also evidence how the spread of negative emotions can affect decision-making in clinical care. For example, either directly experiencing or simply witnessing incivility (either as impatience or rudeness) caused anethesia residents during a training exercise to more likely make incorrect decisions (and actions) regarding a simulated patient with a drop in blood pressure (42). Similar observations have been made for physicians and nurses in a neonatal ICU (43). In nonmedical studies, witnessing or experiencing rudeness also decreases working memory, decision-making, as well as helpfulness (44, 45). Taken together, these provide significant motivation to uplift the healthcare environment to prevent, or at least attenuate, cognitive dysfunction.

Beyond how the patient assesses the quality of the visit, an important effect of stress in health care is the development of a positive interpersonal connection with the provider. Optimizing communication is a major driver in patient-centered care and that includes how the patient perceives the compassion or caring of the provider, which, in turn, affects patient trust and activation (46–48). Dissatisfied patients are less likely to engage in their own care as well as trust the provider (48). As stress will affect how patients perceive the provider's intent and that stress will affect how the provider displays compassion, makes correct decisions and avoids errors, as well as draws satisfaction from their work, it is critical to relieve stress as much as possible.

Stress has Measurable Biological Consequences

Some clinicians might discount the role of psychological stress in clinical care and need to understand the biological consequences to bolster conviction of its importance for patients, for staff, and for themselves. Psychological stress, even in healthy volunteers, who are asked to solve math problems or give a speech, will acutely increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, as well as norepinephrine, cortisol, IL-6, CRP, TNF-alpha, and fibrinogen (49–52). These responses are also observed in response to negative media; study participants exhibit increased markers of inflammation increase as well as changes brain region activity in fMRI studies, effects that are not observed with positive images (53,54).

These acute effects are also seen with chronic stress (55), including increased arterial stiffness, even in normotensive individuals (51,56,57). Taken together, these and other observations link to longer-term studies of chronic stress, increased carotid intima media thickness (50) and directly and indirectly explains the phenotypic manifestations and exacerbations of diseases that the provider treats, including anxiety, depression, hypertension, asthma, diabetes, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (58–61).

Beyond the important psychological and behavioral impact of stress, the biological response to stress in the clinical setting is adding its own pathophysiological burden for everyone involved and re-emphasizes the need to mitigate it.

Making the Health Care Environment Less Stressful

It is understandable, therefore, that the effect of the care environment on psychological well-being has been a focus of health care design (61–65) and is perhaps the simplest change to make to lower stress. Many environmental psychology factors, including noise, layout, color choice, and lighting have been studied and incorporated to varying degrees. For example, natural light from a window has been shown to affect recovery from surgery (64,65) or result in earlier discharge for patients with bipolar disorder (66). This effect also applies to staff; nurses who worked in windowless areas had more stress and decreased alertness than those who worked in areas with windows and external views (67).

Nature and Art in Healthcare

One area of special focus in environmental psychology has been how seeing nature—through direct experience or photography or art—might affect stress and healing. Florence Nightingale observed the importance of experiencing beauty, including exposure to natural light and the ability to look out the window or gaze at flowers. She noted that: “People say the effect [of natural beauty] is only on the mind. It is no such thing—it has a physical effect on the body.’” (64)

The extension of Nightingale's observation is that exposure to nature, or scenes of nature, decreases stress and has been characterized as “restorative therapy” (68–71). Studies of restorative experiences suggested that the inclusion of plants, or images of plants and other natural elements, decreased reported anxiety or stress (70,72,73) and that this exposure could also help restore attention (63,68,69) as well as enable more rapid healing (71). That is, seeing or experiencing nature could aid in the cognitive dysfunction and delayed healing (74) that stress induces.

In alignment with a decrease in stress and anxiety, nature video or images have also been reported to decrease subjective pain (75) as well as markers of stress (70) and positively affect mood (76). As a result, nature imagery (eg, photography or art) has been incorporated into many health care settings, including emergency rooms and behavioral health clinics, where there is evidence of a positive impact (77,78).

Use Of Positive Media in Waiting Rooms

As the eye is naturally (and subconsciously) drawn to motion, the television is a significant element of the waiting room environment and will command more attention than static images or wall decorations (79).

In contrast to the impact of negative or neutral media described earlier, it is more advisable to show patients positive media while they wait. One aforementioned type of positive media is nature-based. Nature media induces relaxation, decreases negative emotions following a stress-induction period, as well as decreases heart rate, blood pressure, R-R variation (a measure of sympathetic-parasympathetic activity), and facial tension (73). Viewers primed with nature images react faster to joyful speech (80) and display improved EF, particularly attention control (68,71).

A second type of positive media that can reduce stress is that depicting kindness and compassion or other prosocial acts. Studies of this type of media have generally used short video clips (∼2-7 min) from commercial programming such as The Oprah Winfrey Show and measured changes in affect and behavior (81–85). In those studies, viewers experienced “elevation,” which is a sense of relaxation while being uplifted, usually accompanied by physical sensations such as warmth (86). These and other studies showed that viewers felt a greater sense of feeling connected to others, including to members of other racial or cultural groups (84) and decreases in dehumanization of others (87).

The impact of kindness media was recently tested in a healthcare setting (pediatric dental clinic) (88). Fifty parents and staff were randomized to view either children's commercial television or kindness media. This media is a multicultural blend of images of kindness and compassion complemented by kindness-related quotes, concepts, suggestions, and humor that is streamed into the waiting room. In comparison to children's programming, viewers of kindness media were more inspired, happier, calmer, and grateful. They were also more generous. This field study opens the prospect of using kindness media to help uplift the healthcare environment.

One of the features of media use is that these effects are largely subconscious or precognitive. That is, viewers’ emotions and behaviors are shaped by the visual primes that they are given, just as they are when seeing negative or violent imagery with increased sadness and aggression (89). As subconsciously interpreted, they are also processed rapidly, a desirable quality in a rapid paced and information overloaded world. Some still image examples of kindness media can be seen in Figures 3 and 4. A video sample can be found at https://vimeo.com/440459946.

Figure 3.

A still image example of kindness media from a Filipino photographer. The reader might reflect on how they feel after seeing the image, which can provide personal insight into how kindness media can affect viewers. Photo by Brian Enriquez, with permission.

Figure 4.

A still image example of kindness media from a photographer from Turkey. The reader might reflect on how they feel after seeing the image, which can provide personal insight into how kindness media can affect viewers. Photo by Leyla Emektar, with permission.

Beyond a priming effect, the media may work well because it stirs an innate predisposition to care for and connect with others. Connection is a known path to buffer stress and increase resilience and caring in multiple studies, just as the disconnection of loneliness and ostracism increase stress and mortality. Thus, the potential of kindness media to induce connection on a widespread and passive basis has significant implications for stress reduction and the promotion of community (90).

Envisioning an Uplifted Patient–Provider Encounter

Although the direct relief of stressors (eg, financial problems) is highly desirable, these take considerable time, money, and cooperation. And although helping patients and staff engage in meditation, exercise, yoga, and other practices would be immensely beneficial, that, too, is also resource challenged.

Given the simplicity and low cost with which media can be deployed, however, consideration of media selection can be an immediate change that can help uplift the health care environment. Minimally, negative and neutral media should be removed. Above all, the news should not be displayed. To actively help reduce stress, use positive media like kindness and nature media. Kindness media can also uplift the environment by inspiring eudaimonia (transcendent happiness) and strengthening interpersonal connection.

It is anticipated that when a more uplifted and relaxed patient enters the examination room, the ported emotional state will spread to the provider, who can reflect it back through better communication and perceived caring, as well as pass it on to others, including staff. In the longer-term, this can help enable heightened patient activation and engagement and provider satisfaction and morale, with clinical outcomes as a beneficiary.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the many volunteers and contributors who over the years helped create this integrated view of how the promotion of kindness may affect personal connection and quality of life. Envision Kindness is a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) with a mission to reduce stress and promote positive interpersonal connection through promoting kindness, compassion, joy, and love. Envision Kindness creates, studies, and distributes kindness media (EnSpire™).

Author Biography

David Fryburg, MD is the president and co-founder of Envision Kindness, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to promote kindness, caring, and joy through kindness media. Envision Kindness creates and distributes kindness media to stream into health care and other high stress environments. Envision Kindness also studies the impact of kindness media. Prior to Envision Kindness, Dr. Fryburg was a faculty member of the University of Virginia School of Medicine, followed by the Global Translational Medicine Leader For Cardiovascular, Metabolic, and Endocrine Diseases at Pfizer, and later, Consultant and Team Leader, Foundation for the NIH Biomarkers Consortium.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The author is the co-founder and President or Envision Kindness, a not-for-profit (501(c)(3)) organization that creates and studies kindness media. Dr Fryburg serves in these capacities as a volunteer. Envision Kindness creates and distributes kindness media. As Envision Kindness is a not-for-profit organization, no ownership stake is available to anyone.

Funding: The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The author gratefully acknowledges the funding of Envision Kindness's recent work by our generous donors and the Good People Fund.

ORCID iD: David A. Fryburg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5348-2707

References

- 1.Gallup. Gallup Global Emotions Survey Report . 2019.

- 2.APA. Stress in America Annual report of American Psychological Association. 2019.

- 3.Avey H Matheny KB Robbins A Jacobson TA.. et al. Health care providers’ training, perceptions, and practices regarding stress and health outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95(9):833,846 -45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park CL Russell BS Fendrich M Finkelstein-Fox L Hutchison M Becker J.. et al. Americans’ COVID-19 stress, coping, and adherence to CDC guidelines. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(8):2296-303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KA, Tietbohl C, Elwyn Get al. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled ‘difficult’ among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(5):1030-8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu H Westbrook RA Njue-Marendes S Giordano TP Dang BN.. et al. The psychology of the wait time experience – what clinics can do to manage the waiting experience for patients: a longitudinal, qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):459. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4301-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherwin HN McKeown M Evans MF Bhattacharyya OK.. et al. The waiting room “wait”: from annoyance to opportunity. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(5):479-81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Efrat-Treister D, Cheshin A, Harari D, Rafaeli A, Agasi A, Moriah H, et al. How psychology might alleviate violence in queues: perceived future wait and perceived load moderate violence against service providers. PLoS One 2019;14(6):e0218184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin SS, Thijs L, Hansen TW, O’Brien E, Staessen JA. White-coat hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62(6):982-7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randall CL, Shulman GP, Crout RJ, McNeil DW. Gagging and its associations with dental care-related fear, fear of pain and beliefs about treatment. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145(5):452-8. 2014/05/03. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborn TM, Sandler NA. The effects of preoperative anxiety on intravenous sedation. Anesth Prog. 2004;51(2):46-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gras S, Servin F, Bedairia E, Montravers P, Desmonts JM, Longrois D, et al. The effect of preoperative heart rate and anxiety on the propofol dose required for loss of consciousness. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(1):89-93. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c5bd11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gürbulak B, Üçüncü MZ, Yardımcı E, Kırlı E, Tüzüner F. Impact of anxiety on sedative medication dosage in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2018;13(2):192-8. 2018/07/14. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2018.73594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geva N, Pruessner J, Defrin R. Acute psychosocial stress reduces pain modulation capabilities in healthy men. Pain 2014;155(11):2418-25. 2014/09/25. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teoh KRH, Hassard J, Cox T. Individual and organizational psychosocial predictors of hospital doctors’ work-related well-being: a multilevel and moderation perspective. Health Care Manage Rev 2020;45(2):162-72. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Hunderfund AL, Sinsky CA, Trockel M, Tutty M, et al. Relationship between burnout, professional behaviors, and cost-conscious attitudes Among US physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(5):1465-76. 2019/11/18. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05376-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínez-Zaragoza F, Fernández-Castro J, Benavides-Gil G, García-Sierra R. How the lagged and accumulated effects of stress, coping, and tasks affect mood and fatigue during nurses’ shifts. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(19):7277. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen M, Burnett C. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occup Med (Chic Ill). 2008;58(1):25-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National_Academy_of_Medicine_Action_Collaborative_on_ Clinician_Well-being.

- 20.Singh Ospina N, Phillips KA, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Eliciting the patient’s agenda- secondary analysis of recorded clinical encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):36-40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4540-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, Satele D, Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571-80. 2018/07/09. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jawad M Ingram S Choudhury I Airebamen A Christodoulou K Wilson Sharma A.. et al. Television-based health promotion in general practice waiting rooms in London: a cross-sectional study evaluating patients’ knowledge and intentions to access dental services. BMC Oral Health. 2016;17(1):24-24. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0252-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Hoog N, Verboon P. Is the news making us unhappy? The influence of Daily News exposure on emotional states. Br J Psychol 2020;111(2):157-73. 2019/03/23. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston WM, Davey GCL. The psychological impact of negative TV news bulletins: the catastrophizing of personal worries. Br J Psychol. 1997;88(1):85-91. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1997.tb02622.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubenking B. Boring is bad: effects of emotional content and multitasking on enjoyment and memory. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;72:488-95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eastwood JD, Frischen A, Fenske MJ, Smilek D. The unengaged mind: defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspect Psychol Sci 2012;7(5):482-95. 2012/09/01. doi: 10.1177/1745691612456044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukasik KM, Waris O, Soveri A, Lehtonen M, Laine M. The relationship of anxiety and stress With working memory performance in a large Non-depressed sample. Original Research. Front Psychol. 2019;10(4):1-8. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgado P, Sousa N, Cerqueira J. The impact of stress in decision making in the context of uncertainty. J Neurosci Res. 2015;93:839-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartley CA, Phelps EA. Anxiety and decision-making. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72(2):113-8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnsten AFT. Stress weakens prefrontal networks: molecular insults to higher cognition. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(10):1376-85. doi: 10.1038/nn.4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwabe L, Wolf OT. Stress prompts habit behavior in humans. J Neurosci. 2009;29(22):7191-8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0979-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnaudova I, Kindt M, Fanselow M, Beckers T. Pathways towards the proliferation of avoidance in anxiety and implications for treatment. Behav Res Ther 2017;96:3-13. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holahan CJ Moos RH Holahan CK Brennan PL Schutte KK.. et al. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):658-66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy AG Scherer AM Zikmund-Fisher BJ Larkin K Barnes GD Fagerlin A.. et al. Prevalence of and factors associated With patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(7):e185293-e185293. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimitroff SJ, Kardan O, Necka EA, Larkin K, Decety J, Berman MG, et al. Physiological dynamics of stress contagion. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6168-6168. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05811-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barsade SG. The ripple effect: emotional contagion and Its influence on group behavior. Adm Sci Q. 2002;47(4):644-75. doi: 10.2307/3094912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional contagion. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1993;2(3):96-9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly JR, Iannone NE, McCarty MK. Emotional contagion of anger is automatic: an evolutionary explanation. Br J Soc Psychol. 2016;55(1):182-91. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchanan TW, Bagley SL, Stansfield RB, Preston SD. The empathic, physiological resonance of stress. Soc Neurosci 2012;7(2):191-201. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.588723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper B, Giordano CR, Erez A, Foulk TA, Reed H, Berg KB. Trapped by a first hypothesis: How rudeness leads to anchoring. J Appl Psychol. 2021 Jun 10. 10.1037/apl0000914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katz D, Blasius K, Isaak R, Lipps J, Kushelev M, Goldberg A, Fastman J, Marsh B, DeMaria S. Exposure to incivility hinders clinical performance in a simulated operative crisis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019 Sep;28(9):750-757. 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, Riskin-Geuz KS, Ziv A, Sela R, Pessach-Gelblum L, Bamberger PA. Rudeness and Medical Team Performance. Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20162305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porath CL, Erez, A. Does rudeness really matter? The effects of rudeness on task performance and helpfulness. Academy of Management Journal 2007;50(5):1181-1197. doi: 10.2307/20159919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballatt J, Campling P. Intelligent Kindness: Reforming the Culture of Healthcare. Pensacola FL: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trzeciak S, Mazzarelli A, Booker C. Compassionomics : the revolutionary scientific evidence that caring makes a difference . 2019.

- 48.Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(4):431-7. 2015/03/04. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sin NL, Graham-Engeland JE, Ong AD, Almeida DMet al. Affective reactivity to daily stressors is associated with elevated inflammation. Health Psychol: Official J Div Health Psychol, Am Psychol Assoc 2015;34(12):1154-65. 2015/06/01. doi: 10.1037/hea0000240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Greater cardiovascular responses to laboratory mental stress Are associated With poor subsequent cardiovascular risk Status. Hypertension. 2010;55(4):1026-32. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellins E, Halcox J, Donald A, et al. Arterial stiffness and inflammatory response to psychophysiological stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(6):941-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marsland AL, Walsh C, Lockwood K, John-Henderson NA. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating and stimulated inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2017;64:208-19. 2017/01/17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stellar JE, John-Henderson N, Anderson CL, Gordon AM, McNeil GD, Keltner D. Positive affect and markers of inflammation: discrete positive emotions predict lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. Emotion 2015;15(2):129-33. doi: 10.1037/emo0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvarez GM, Hackman DA, Miller AB, Muscatell KA. Systemic inflammation is associated with differential neural reactivity and connectivity to affective images. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2020;15(10):1024-33. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsaa065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gouin JP, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Beversdorf D, Kiecolt-Glaser J. Chronic stress, daily stressors, and circulating inflammatory markers. Health Psychol 2012;31(2):264-8. doi: 10.1037/a0025536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Munakata M. Clinical significance of stress-related increase in blood pressure: current evidence in office and out-of-office settings. Hypertens Res. 2018;41(8):553-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Stefanadis C. Mental stress, arterial stiffness, central pressures, and cardiovascular risk. Hypertension 2010;56(3):e28. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.110.156505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brotman DJ, Golden SH, Wittstein IS. The cardiovascular toll of stress. Lancet 2007;370(9592):1089-100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61305-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA 2007;298(14):1685-7. 2007/10/11. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010;35(1):2-16. 2009/10/14. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Devlin A, Arneill AB. Health care environments and patient outcomes. Environ Behav. 2003;35:665-94. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frampton SB. Healthcare and the patient experience: harmonizing care and environment. Herd 2012;5(2):3-6. 2012/11/17. doi: 10.1177/193758671200500201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness: theory and recent scientific research. J Health Care Inter Des. 1991;1(3):97-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, Jennifer DuBose J, Seo H-B, Choi Y-S, et al. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. Herd 2008;1(3):61-125. 2008/04/01. doi: 10.1177/193758670800100306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nanda U, Pati D, McCurry K. Neuroesthetics and healthcare design. Herd 2009;2(2):116-33. 2009/01/01. doi: 10.1177/193758670900200210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beauchemin KM, Hays P. Sunny hospital rooms expedite recovery from severe and refractory depressions. J Affect Disord 1996;40(1-2):49-51. 1996/09/09. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pati D, Harvey TE, Jr., Barach P. Relationships between exterior views and nurse stress: an exploratory examination. Herd 2008;1(2):27-38. doi: 10.1177/193758670800100204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gamble KR, Howard JH, Jr., Howard DV. Not just scenery: viewing nature pictures improves executive attention in older adults. Exp Aging Res 2014;40(5):513-30. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2014.956618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15:169-82. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kjellgren A, Buhrkall H. A comparison of the restorative effect of a natural environment with that of a simulated natural environment. J Environ Psychol. 2010;30(4):464-72. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ulrich RS Simons RF Losito BD Fiorito E Miles MA Zelson M.. et al. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol. 1991;11(3):201-30. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dijkstra K, Pieterse ME, Pruyn A. Stress-reducing effects of indoor plants in the built healthcare environment: the mediating role of perceived attractiveness. Prev Med 2008;47(3):279-83. 2008/03/11. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jo H, Song C, Miyazaki Y. Physiological benefits of viewing nature: a systematic review of indoor experiments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4739. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gouin JP, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and mechanisms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2011;31(1):81-93. 2010/11/26. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malenbaum S, Keefe FJ, Williams A, Ulrich R , Somers TJ, et al. Pain in its environmental context: implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain 2008;134(3):241-4. 2008/01/04. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weinstein N, Przybylski AK, Ryan RM. Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2009;35(10):1315-29. 2009/08/07. doi: 10.1177/0146167209341649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nanda U, Chanaud C, Nelson M, Zhu X, Bajema R, Jansen BH. Impact of visual art on patient behavior in the emergency department waiting room. J Emerg Med 2012;43(1):172-81. 2012/02/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nanda U, Eisen S, Zadeh RS, Owen D. Effect of visual art on patient anxiety and agitation in a mental health facility and implications for the business case. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2011;18(5):386-93. 2011/05/05. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wolfe JM, Horowitz TS. Five factors that guide attention in visual search. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1(3):0058. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Korpela KM, Klemettilä T, Hietanen JK. Evidence for rapid affective evaluation of environmental scenes. Environ Behav. 2002;34(5):634-50. doi: 10.1177/0013916502034005004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Janicke S, Oliver MB. Meaningful films: the relationship between elevation, connectedness and compassionate love. J Psychol Pop Media Cult 2015;6(3):274-89. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oliver MB, Kim K, Hoewe J, Ash E, Woolley JK, Shade DD, et al. Media-Induced elevation as a means of enhancing feelings of intergroup connectedness. J Soc Issues. 2015;71(1):106-22. doi: 10.1111/josi.12099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oliver MB, Raney AA, Slater MD, et al. Self-transcendent Media experiences: taking meaningful Media to a higher level. J Commun. 2018;68(2):380-9. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Freeman D, Aquino K, McFerran B. Overcoming beneficiary race as an impediment to charitable donations: social dominance orientation, the experience of moral elevation, and donation behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2009;35(1):72-84. 2008/11/20. doi: 10.1177/0146167208325415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schnall S, Roper J, Fessler DM. Elevation leads to altruistic behavior. Psychol Sci 2010;21(3):315-20. doi: 10.1177/0956797609359882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Algoe SB, Haidt J. Witnessing excellence in action: the ‘other-praising’ emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. J Posit Psychol 2009;4(2):105-27. 2009/06/06. doi: 10.1080/17439760802650519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blomster Lyshol JK, Thomsen L, Seibt B. Moved by observing the love of others: kama muta evoked through Media fosters humanization of Out-groups. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1240-1240. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fryburg DA, Ureles SD, Myrick JG, Carpentier FD, Oliver MB. Kindness Media rapidly inspires viewers and increases happiness, calm, gratitude, and generosity in a healthcare setting. Front Psychol 2020;11:591942. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.591942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dillman Carpentier FR. Priming. In P. Rossler (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0050. 2017. [DOI]

- 90.Fryburg DA. Kindness as a stress reduction–health promotion intervention: a review of the psychobiology of caring. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021:1559827620988268. doi: 10.1177/1559827620988268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]