ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has spread rapidly. To date, countries have relied on the prevention of the disease through isolation, quarantine, and clinical care of affected individuals. However, studies on the roles of asymptomatic and mildly infected subjects in disease transmission, use of antiviral drugs, and vaccination of the general population will be very important for mitigating the effects of the eventual return of this pandemic. Initial investigations are ongoing to evaluate antigenic structures of SARS-CoV-2 and the immunogenicity of vaccine candidates. There also is a need to comprehensively compile the details of previous studies on SARS-related vaccines that can be extrapolated to identify potent vaccine targets for developing COVID-19 vaccines. This review aims to analyze previous studies, current status, and future possibilities for producing SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, pandemic, vaccines

Introduction

In late December 2019, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology linked to the Huanan seafood market, Wuhan, China was officially reported by the Health Commission of Hubei province, China.1,2 A virus formerly called as the “Wuhan virus” and provisionally designated as “2019-nCoV” by WHO was identified as being responsible for this outbreak. The virus was officially named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease as COVID-19.3,4 Following the reporting of COVID-19 infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 in China5 and subsequent confirmation by national6,7 and international health agencies,4,8 transmission dynamics studies9,10 and genomic analyses11-14 were undertaken to explore the various epidemiological attributes14-16 along with clinical features of the disease.1,15,17, However, the rapid global spread and alarming rise in the number and severity of the cases necessitated devising early therapeutics1,15,18, and preventive measures10,19 against COVID-19.20–23 For this combat strategy, deciphering the structure24,25 and functional roles11,13,26, of the structures of SARS-CoV-2,14,27-29 their antigenic properties,11,13,26-29 roles in immune response and pathogenesis,30–33 and the potential for vaccine development25,26,34 is of utmost importance for the prevention and control of this disease.33,35-37

Convalescent sera or plasma therapy,15,38 and killed and inactivated/attenuated vaccines26,39 can help in the prevention of this disease; however, numerous challenges are associated with these approaches including chances of re-infection.34,40 These limitations can be overcome by employing subunit vaccines based on the molecular structures of SARS-CoV-2; however, these prophylactics may require periodic boosters owing to their low immunization potential.9,11,13,41 Recombinant vaccines, DNA- or RNA-based vaccines, can further improve immunity with minimum side-effects; however, antigenicity and adequacy of immune response need further exploration.26,42,43 For the development of any of these vaccine types, understanding the antigenic structures of SARS-CoV-2 is essential.26,39

Structural11 and non-structural14 proteins of SARS-CoV-2, in addition to its genetic material,26,44 are being explored as vaccine candidates. These studies are possible as the genomic9,12,14 and molecular details,24,28,29 of the structures of SARS-CoV-2, their role in receptor binding, fusion, tissue tropism, and pathogenesis25,31,33,45 are under continuous and progressive investigation. The S gene of the coronaviruses encodes the spike (S) glycoprotein that is responsible for binding with a cellular receptor in order to initiate infection. The S protein consists of two subunits, S1 and S2, of which the S1 subunit constitutes the N-terminal domain (NTD) and receptor-binding domain (RBD).11 Similar to SARS-CoV, the SARS-CoV-2 utilizes the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor for cellular entry.28,46 Neutralizing antibodies are mainly directed against the S glycoprotein, as it is the major structural protein, rendering it a potent target for vaccine development against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.47,48 Similarly, the S protein can be targeted for the development of vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2 as well. Thus, targeting the structure11,24 of SARS-CoV-2 as well as examining its receptor recognition,28 affinity for binding,25 fusion,25,31 entry mechanisms,49 pathogenesis,25,29,31 and finally, its disease severity mechanisms1,50 can better help in the development of prophylactic or therapeutic strategies.

The impact of COVID-19 varies among countries and territories, probably due to differences in culture, health-care facilities and mitigation efforts. Moreover, a study proposed the role of national policies related to childhood BCG (Bacillus Calmette–Guerin) vaccination, which provides protection against a broad category of respiratory infections as possible explanation for these national differences in the impact of COVID-19.51 Surprisingly, countries without universal policies or with a late start of universal policies of childhood BCG vaccination were reported to be affected more severely with high mortality suggesting the BCG vaccination as a crucial tool to fight COVID-19.51 In a study, Pasteurella is transformed and an inactivated alum-precipitated infectious bronchitis (IB) vaccine is produced within a period of 2 weeks. Moreover, around 9000 birds were vaccinated and the vaccine has proven very effective against IB. In addition, it is assumed that formalin-killed Pasteurella multocida cells prepared by the above method may prove effective in COVID-19 if administered during the early course of the disease.52

COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

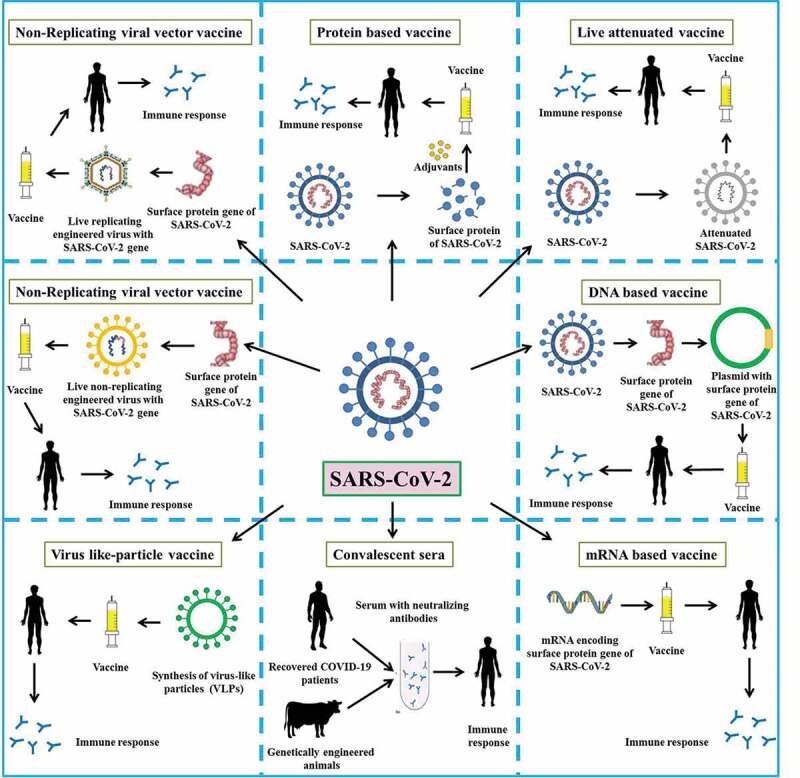

Currently, there are no specific vaccines or therapeutics available against COVID-19.26,27,42 With the rise in the number of affected individuals, severity of the disease, global spread, lack of prophylactics and therapeutics, the demand for immediate therapy and future prevention of COVID-19 is rising.26,38 Attempts are being made to develop safe and effective prophylactic strategies.20,26,39 Several vaccines are in various stages of clinical trials,39 however, in the current scenario, there is a dearth of prophylactics.17,34,39 Convalescent sera, live attenuated or killed virus vaccines, protein-based vaccines, DNA-based vaccines, mRNA-based vaccines, virus-like particle vaccines, vector and non-vector-based vaccines are some of the possibilities to be considered for developing prophylactics against COVID-19.26,39,53

Convalescent sera

One of the earliest available and achievable prophylactic measures is convalescent sera. Convalescent sera from persons who have recovered from the COVID-19 attack can be used as an immediate therapy.38 Genetically engineered animals, such as cows54 could also serve as sources of such sera; this serum contains immunoglobulins that can bestow passive immunity. These antibodies could help in the neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by triggering antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and/or phagocytosis.38 Consequently, convalescent sera can be used as a rapid mode of therapy and prevention. Vaccine-based approaches for prevention may require time. Additionally, although the vaccines might be effective against the current COVID-19 infection, vaccines based on viral-encoded peptides might not be effective against coronavirus outbreaks that may arise in the near future as novel mutated viral strains emerge every year, requiring new immunization strategies.41 Hence, convalescent sera can be a good option for immediate therapy.38,55,56 Immunoglobulins developed against SARS-CoV-2 in serum can help in neutralizing SARS-CoV-2.38 Plasma therapy,15,57,58 synthesized antibodies,59 preferably neutralizing monoclonal antibodies,60 and interferons57 can potentially be utilized in patients with COVID-19.

Monoclonal antibodies developed based on previous experience of working with other coronaviruses can play a role in prevention and control, and can be employed as passive immunotherapy against COVID-19.60 Intravenous administration of immunoglobulins to block FcR activation can be helpful in preventing SARS-CoV-2-induced pulmonary inflammation in the respiratory tract60-62 However, limitations of these sera-based therapies include transmission of causative agents and impurities, abnormal reactions, and insufficient or short-term therapy or prevention.

Possibility of other risks like induction of severe acute lung injury by anti-spike antibodies or antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) needs to be explored, which have been observed with either acute SARS-CoV infection, believed to be due to skewed macrophage responses during the infection,63 or COVID-19 affected patients.64,65 ADE is believed to be due to prior exposure to other coronaviruses.50 It modulates the immune response and can elicit sustained inflammation, lymphopenia, and/or cytokine storm.50 ADE also might be caused by the presence of non-neutralizing antibodies to parts of the S protein. These responses can be evaluated by investigating the effects of spike-based antibodies on in vitro cell cultures or animal models in the future, and simultaneous exploration of possible remedial measures to prevent acute lung injury including the blockade of FcγR60,66 or by carrying out independent large-cohort studies, which can help in testing this possibility.67 In addition, developing and using multiple monoclonal antibodies can help in the amelioration of such problems.60 As immunotherapy is a short-term measure, hence, for bestowing long-term immunity and future prevention, the development of vaccines is imperative.

COVID-19 vaccines

Efforts are being made by researchers to design and develop suitable vaccines for COVID-19, though vaccine-based approaches require years for development.17,34,39 In the current situation, national and international scientific guidelines proposed for the efficient management of COVID-19 need to be followed until vaccines are developed.68 Various types of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are possible. These include complete virus-based vaccines (live attenuated, killed), subunit vaccines, nucleic acid-based vaccines (RNA, DNA), recombinant vaccines, virus-like particle vaccines, and vector and non-vector–based vaccines.26,39

Whole organism-based vaccines

The earliest modes of vaccine development involved the utilization of either the entire virus (for the development of complete organism-based vaccines) or its parts (for subunit vaccines). These include attenuating or inactivating the cultured viruses by passaging or by physical and chemical methods, such as subjecting to treatment with ultraviolet light, formaldehyde, and β-propiolactone, respectively.26,39 A review reported that certain induced mutations can completely attenuate the viruses, and hence can be explored as agents for the development of vaccines.53 Moreover, recombinant viruses with deletions of virulent proteins can be utilized as live attenuated vaccines.26 However, these vaccines may have limitations associated with infectivity, reversion to pathogenicity, and disease-causing potential69 that preclude the use of such vaccines in humans.

SARS-COV-2-specific vaccines (subunit vaccines and future vaccine targets)

Exploration of vaccine candidates of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for the development of specific vaccines26,42 and research and development to achieve this objective have already been initiated.55 A set of epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 has been screened, and immune targeting of these epitopes can provide protection against this novel coronavirus, thus providing experimental platforms for the development of vaccines.27 Identification of putative protective antigens/peptides from SARS-CoV-2 is important for the development of subunit vaccines.26 A timely study of genome sequences is proving to be beneficial for subunit vaccine development.11,13 Structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2, including envelope (E), membrane (M), nucleocapsid (N), and spike (S) proteins are being explored as antigens for vaccine development, including subunit vaccines.11,26,39 Proper understanding of the viral structure, mechanisms of binding, entry, and pathogenesis and the events involved, specific to SARS-CoV-2, will help in designing better prophylactic and therapeutic modalities. The molecular structure of the novel coronavirus, role of its structures in immunogenicity, potential as vaccine candidate, cellular and antibody response developed by it or against it, need to be discussed with special focus on the whole structure or specific structures of SARS-CoV-2.

All the four structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2, including envelope (E), membrane (M), nucleocapsid (N), and spike (S) proteins can serve as antigens to induce cellular (through CD4+/CD8+ T cells) and humoral (through neutralizing antibodies) responses.11,13,26 The E and M proteins help in the assembly of CoV, whereas the N protein is involved in the synthesis of genetic material (RNA).43 The E protein also has a role in determining the virulence of these viruses; and hence, recombinant coronaviruses with mutated E protein are being evaluated as live attenuated vaccines.43,70 The M protein plays a role in determining the membrane structure, and can serve to increase the immunological stimulation of SARS-CoV N protein DNA vaccine.71 As the N protein is conserved in all CoV families, it is not a specific vaccine candidate. Furthermore, anti-SARS-CoV-2-N protein antibodies have not been successful in generating immunity against the infection.44 The S glycoprotein is a critical and important structural protein of SARS-CoV-2 that is responsible for mediating viral binding to host cell receptors and entry into host cells.28,44 Upon the proteolytic cleavage of the precursor S protein of SARS-CoV-2, two subunits are produced. These include S1 (685 aa) and S2 (588 aa) subunits.11 The S2 subunit is considered to be important as it is well conserved in SARS-CoV-2 viruses; it has 99% identity with bat SARS-CoVs.11 Therefore, it has a potential to be used as a vaccine candidate and can boost immune responses against SARS-CoV-2.26 The S1 subunit contains receptor-binding domain (RBD), which is important for binding to the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor via a receptor-binding motif (RBM), thereby mediating viral entry into sensitive host cells.25,28,29 The S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 shows 70% identity to human SARS-CoVs. Moreover, the external subdomain of the RBD that helps in virus and host receptor binding exhibits the highest number of amino acid variations.11,28 Strategies that target the initial entry of virus are considered to be effective for the prevention and control of COVID-19;26 consequently, elucidation of the mechanisms underlying binding and entry is crucial.

Wan et al.28 provided vital information on receptor usage, cell entry, and host cell infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. Sequences of RBD and its receptor-binding motif (RBM), which is mainly responsible for direct binding to ACE2, are similar in SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, thus indicating that ACE2 is the receptor for SARS-CoV-2.28 Some critical residues present in the RBM of SARS-CoV-2 also suggest a potential for human infection. Among these, some residues (especially Gln493) interact specifically with human ACE2, indicating the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect human cells, while others (especially Asn501) show compatibility with human ACE2, indicating its capability of human-to-human transmission. Phylogenetic analysis and recognition of ACE2 receptors from various animal species (excluding mice and rats) suggest an animal source of infection or animal model for infection.28 Furthermore, a single N501T mutation in SARS-CoV-2 (corresponding to the S487T mutation in SARS-CoV) can increase the binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 RBD to human ACE2, suggesting future emergence of infections.28 Further investigations have helped in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying these events. The S glycoprotein, which is an ~1200 aa long protein of the class-I viral fusion proteins, contributes to receptor binding, tissue tropism, and pathogenesis.25,31 It contains several conserved domains (RBDs) and motifs (RBMs). The trimetric S glycoprotein is cleaved at the S1/S2 cleavage site by host cell proteases during infection, resulting in the production of N-terminal S1-ectodomain and C-terminal S2-membrane-anchored protein.31 The former helps in recognizing the cell receptor, while the latter helps in viral entry. The subunit S1 contains an RBD that recognizes the ACE2 receptor. Of the 14 aa present on the RBD surface of S1/ACE2 of the S1 subunit of SARS-CoV, 8 residues are strictly conserved in SARS-CoV-2, further strengthening the fact that ACE2 acts as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2 as well.25,28,31 The S2 subunit contains a fusion peptide (FP), second proteolytic site (S’), an internal fusion peptide (IFP), two heptad-repeat domains, and a transmembrane domain (TM).31 Coutard et al.31 claim that there are two cleavage sites in SARS-CoV-2; first being between RBD and the FP (S1/S2) and the second being at KR↓SF. FP and IFP may be involved in entry mechanisms suggesting that the S-protein needs to be cleaved at both the S1/S2 and S2ʹ cleavage sites. In SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, the S2ʹ cleavage site at KR↓SF, downstream of the IFP is identical. Although processing at S2ʹ in SARS-CoV-2 is essential for the activation of the S protein, the proteases involved in this process are yet to be identified. However, based on the sequences studied, one or more furin-like proteases would cleave the S2ʹ at KR↓SF.31 Cleavage sites at S1/S2 have been extensively studied in CoVs.31 Proteases act as furin-like cleavage molecules to cleave S into S1 and S2.31 The presence of furin-like proteases increases the pathogenicity of the virus and hence the severity of disease.31 Consequently, targeting these sites, enzymes, or proteins can have beneficial applications. For targeting these structures, their antigenic potential needs to be evaluated to uncover potential epitopes.

Ahmed et al.27 have evaluated epitopes for SARS-CoV-2 based on epitopes that have induced immune responses against SARS-CoV, and hence can be explored as vaccine candidates. They have mainly investigated the S and N proteins of SARS-CoV-2 in relation to those of SARS-CoV. Percentage sequence identities of SARS-CoV-2 S protein, N protein, M protein, and E protein with those of SARS-CoV are 76.0%, 90.6%, 90.1%, and 94.7%, respectively (Ahmed et al. 2020).27 Based on genome sequencing and phylogenetic analyses,12,14 the cell entry mechanism and human cell receptor usage14,45,49 of SARS-CoV-2 resemble those of SARS-CoV.27 Although the genome sequences of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are similar to some extent, antigenic differences are found between them. Only around 23% and 16% of the known SARS-CoV T-cell and B-cell epitopes, respectively, map identically to those of SARS-CoV-2. No mutation has been noted in these epitopes in the available SARS-CoV-2 sequences, suggesting their potential roles in cellular and humoral immune responses.14,21,27 Ahmed et al.27 identified B-cell and T-cell epitopes in the immunogenic structural proteins, S and N of SARS-CoV. T cell-based epitopes are promising vaccine candidates, producing an effective cellular immune response, and as these epitopes have a large population coverage, therefore, vaccines against these epitopes can be used across a range of populations.27 Therefore, T cell response against SARS-CoV-2–derived epitopes may provide long-term protection and may provide immunity to large populations.27,72,73 Similarly, B cell-based epitopes, especially linear B cell epitopes, have shown promise as vaccine candidates by aiding the development of humoral immune response.27 These findings are similar to those of Ramaiah and Arumugaswami.74 However, Ramaiah and Arumugaswami74 have focused only on MHC class II epitopes when Ahmed et al.27 have focused on both MHC class I and MHC class II epitopes. Only the HLA-DRB1*01:01 epitope is common between both the studies, which may be due to comparatively low population coverage.74 Ramaiah and Arumugaswami74 used computational tools, while Ahmed et al.27 used epitopes that were positive in either T-cell or MHC binding assays.

As the RBD of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 shows some identity, Tian et al.24 examined the cross-reactivity of anti-SARS-CoV monoclonal antibodies with the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 to explore the possibility of prophylactic or therapeutic applicability. They reported effective binding of SARS-CoV-specific human monoclonal antibody, CR3022, to SARS-CoV-2 RBD. Within the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, the epitope bound by this monoclonal antibody does not overlap with the ACE2 binding site, suggesting the potential of CR3022 to be developed as a therapeutic entity. Other SARS-CoV-specific antibodies (m396, CR3014) do not bind with SARS-CoV-2 S protein suggesting variations in the RBDs of the two coronaviruses. Due to the difference in cross-reactivity, there is a need to develop SARS-CoV-2–specific monoclonal antibodies.24

The S protein of SARS-CoV-2, being a transmembrane glycoprotein, is essential for binding to the receptor (ACE2), fusion of viral-host cell membranes, and entry of virus into the human respiratory epithelial cells; the entire mechanism is mediated by the interaction of structural subunits of S with the cell surface receptor, ACE2.14,29,45,49 As the S protein is surface-exposed and essential for viral entry into host cells, it is the main target for neutralizing antibodies, and hence a candidate for vaccine development.29 Recently, the cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM)-based structure of SARS-CoV-2 S ectodomain trimer has been revealed, and is shown to have multiple SB conformations similar to those of SARS-CoVs and MERS-CoVs.29 However, it harbors a furin cleavage between the S1/S2 subunits, which is processed during biogenesis, and hence is differentiated from other CoVs.25,29 Using 3.5-angstrom-resolution Cryo-EM, Wrapp et al.25 have studied the prefusion conformation of the trimeric S glycoprotein and have revealed that the predominant state of the trimer has one of the three receptor-binding domains, rotated in a receptor-accessible conformation.

The S glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 shares 75% to 97% sequence identity with the amino acid sequences of S glycoprotein from other SARS-CoVs, including bat coronaviruses.14,25,28,29 A 193-aa long RBD (N318‒V510) within the S protein of CoVs is a critical target for neutralizing antibodies.24 There is a 50‒73% sequence identity between SARS-CoV RBDs and SARS-CoV-2 RBDs.24,28,29 However, some RBDs are conserved while others are not; hence, antibodies against SARS-CoV S protein may or may not show cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV-2 S protein.24,25 The binding motifs of the RBD of S protein of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 receptor have been noted to be similar, suggesting ACE2 to be a potential receptor for SARS-CoV-2.24,25,29

The RBD of SARS-CoV-2 differs from that of SARS-CoV, mainly at the C-terminus residues, which may not affect the binding with ACE2 but can affect the cross-reactivity.24 However, based on biophysical and structural evidences, Wrapp et al.25 have noted a 10-times greater binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 S protein RBD to human ACE2 than that of SARS-CoV, suggesting a stronger binding affinity than those of other CoV RBDs; this may be the cause of rapid transmission among humans. There is an insertion of a four amino-acid residue at the boundary between S1 and S2 subunits, producing a furin cleavage site, which is cleaved during biosynthesis, and is an important characteristic of SARS-CoV-2.14,29 Abrogation of this cleavage site slightly affected the mechanism of entry but increased the tropism of SARS-CoV-2.29 The binding affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for human ACE2 (hACE2) reflects the overall viral replication rate, transmissibility, and severity of the disease.28 The S protein of SARS-CoV contains approximately 14 hACE2 binding sites; among these, 8 are strictly conserved in SARS-CoV-2 S and the rest 6 are semi-conservatively substituted.29 This indicates similar binding affinities of the S proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 for hACE2; hence, these viruses display a high transduction efficiency mediated through S glycoproteins and the current rapid transmission in humans.29 The two structural conformations of the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein include trimers harboring a single open SB domain25,29 and trimers harboring three closed SB domains.29 In highly pathogenic coronaviruses, the S glycoprotein trimers remain partially open, whereas in those causing mild cold they remain closed.29 These conformational changes generate epitopes in the RBMs that can serve as a basis for vaccine development.29 Cellular proteases (TMPRSS2) are being used for entry into cells by SARS-CoV-2.49 SARS-CoV polyclonal antibodies prevent S glycoprotein-mediated entry of SARS-CoV-2 by targeting the highly conserved S2 subunit of these glycoproteins. S2 subunit being identical in both SARS-CoV S and SARS-CoV-2 S, an antibody-based response causes difficulties in serological investigations; however, similarities in immunogenicity can help in devising multivalent vaccines.29

SARS-CoV-derived antibodies targeting the RBM in the S2 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein may be more effective than that in the S1 subunit, because the S1 unit is less exposed and maps identically to that of SARS-CoV.24,25,27 B cell epitopes have a potential to generate cross-reactive and neutralizing antibodies against both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.27,29 Linear SARS-CoV-derived B cell epitopes in the S2 subunit may potentially be better candidates for inducing a protective antibody response than those in the S1 subunit, as large genetic mismatches are observed between the known structural epitopes of this domain in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.24,25,27, Therefore, S2 linear epitopes need to be explored for inducing a humoral immune response and as vaccine candidates.27 Overall, vaccine candidates that attempt to induce antibodies targeting the S2 linear epitopes may be effective and should be explored further.27

A study demonstrated that the cross-reactivity of antibodies against SARS-CoV RBDs toward SARS-CoV-2 RBDs, as three antibodies that bound to SARS-CoV did not bind to SARS-CoV-2, indicating the differences in RBDs of the S glycoproteins. Hence, there is a need to develop specific monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.25 This also implies that the structure of SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein can serve as a target for vaccine or therapeutic development.25

Ahmed et al.27 explored a set of T- and B-cell epitopes derived from the S and N proteins of SARS-CoV, which mapped identically to SARS-CoV-2 and had no mutations in the 120 genome sequences that were studied. Consequently, these can serve as candidates for the development of subunit vaccines. Recently antigenicity along with structure and function of the S glycoprotein, especially of a linear epitope of SARS-CoV-2 S2 subunit has been evaluated.29 Neutralizing antibodies have been raised against the S2 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 that cross-react with and neutralize SARS-CoV-2 as well as SARS-CoV;29 these can be explored as candidates for developing subunit vaccines. Subunit vaccines have limitations of low immunogenicity, requirement of adjuvants, and sometimes-inefficient protective immunity. An S-trimer subunit vaccine is under development, wherein a COVID-19S-trimer is being evaluated as a vaccine candidate by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Clover Biopharmaceuticals (China). In this Trimer-Tag technology, a protein-based coronavirus vaccine candidate (COVID-19S-Trimer) developed by Clover Biopharmaceuticals is being tagged with an adjuvant system of GlaxoSmithKline, aimed at boosting the immune response.53 TriSpike SARS coronavirus vaccine, hybrid peptides, and COVID-19 viral peptides are other candidates studied for the development of protein-based vaccines (https://storage.googleapis.com/wzukusers/user-26831283/documents/5e57ed391b286sVf68Kq/PR_Generex_Coronavirus_Update_2_27_2020.pdf).53

A vaccine based on the S2 protein subunit of the S glycoprotein that helps in membrane fusion can have broad-spectrum antiviral effects, as it is conserved in SARS-CoV-2.11,26,43 Targeting the S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 can prevent viral entry, and hence can be used as a strategy for controlling viral infection.26 Targeting the S protein can assist in developing both cellular and humoral immunity by inducing neutralizing antibodies and developing protective cellular immunity.26 The full-length S protein75 and RBD76 of SARS-CoV have shown a potential to be explored in SARS-CoV-2 for vaccine development.26 A study suggested the use of SARS-CoV RBD recombinant protein (RBD219-N1) for the development of a heterologous vaccine against COVID-19 due to the high similarity in amino acids between spike and RBD domains of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.77 Similarly, the S1 subunit of S protein in SARS-CoV-2 can be explored for antibody production; hence, it can be employed as a prophylactic and therapeutic target.11 However, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 have some antigenic differences. For example, they possess discontinuous epitopes; consequently, antibodies specific to the former (S230, m396, and 80R) may not bind to the same region in SARS-CoV-2.25,27 As a result, efforts are being made to identify antibodies against SARS-CoV that can bind to discontinuous epitopes of the SARS-CoV-2.24 Only 23% of the T-cell- and 16% of B-cell-identified epitopes of SARS-CoV map identically to SARS-CoV-2, and there is no mutation in these epitopes among the available SARS-CoV-2 sequences till date (21st February 2020), indicating their potential role in T cell or antibody response in SARS-CoV-2.27 In a study, a novel decoy cellular vaccine strategy was explored by using transgenic antigen-expressing cells called “I-cells” in the prototype of vaccine against the SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, this strategy suggests post-harvesting irradiation of the cells for the abolition of in vivo replication potential and offer a scalable and uniform cell product further allowing “off-the-shelf” frozen supply availability.78

Nucleic acid-based vaccines

The limitations of subunit vaccines can be overcome by DNA- and mRNA-based vaccines, which are easier to develop and can be quickly tested in clinical trials.26 Chimeric nucleic acids encoding calreticulin, an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone polypeptide that forms a part of the antigenic polypeptide or peptide of the SARS-CoV, have been explored in immunological studies as vaccine candidates.53 DNA vaccines are being explored for COVID-19 (http://ir.inovio.com/news-and-media/news/pressrelease-details/2020/Inovio-Accelerates-Timeline-for-COVID-19-DNA-Vaccine-INO-4800/default.aspx). Administration of mRNAs has the ability to recapitulate natural infections; thus, they can induce strong immune responses besides being compatible with each other when multiple mRNAs are combined in a single vaccine.39,50 Similarly, exploiting mRNAs that encode any one of the antigenic structures of SARS-CoV-2, including S protein or its subunits, S1 and S2, E, N or M proteins can help in mRNA-based vaccine development.39,53 An mRNA vaccine, consisting of mRNAs that code for full-length viral S, S1, or S2 proteins, and are antigenic in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, is under consideration. Recently, an mRNA vaccine, named mRNA-1273, has been developed by Moderna in collaboration with National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) against SARS-CoV-2 (https://investors.modernatx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/moderna-shipsmrna-vaccine-against-novel-coronavirus-mrna-1273). This vaccine targets a prefusion-stabilized form of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein. Mutated SARS-CoV-2 especially with altered E proteins can be exploited as recombinant vaccines, as the N proteins are conserved across CoVs and cannot be used as suitable vaccine candidates.26,44

Particle-based vaccines

These vaccines can be constructed and used without a need for adjuvants. The development of such vaccines is possible only when antigens having neutralizing epitopes are thoroughly explored.26 Virus-like particle (VLPs) vaccines are being explored for COVID-19.39,53,79 They can be produced in plants by expressing structural viral proteins.79 Recently, Novavax has developed a VLP vaccine for COVID-19 by utilizing the S protein of SARS-CoV-2. It is based on recombinant nanoparticle vaccine technology and contains the adjuvant, Matrix-M (http://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-advances-developmentnovel-covid-19-vaccine).

A study suggested the probable use of plant biotechnology for the development of low-cost vaccines and plant-made antibodies against COVID-19 for diagnosis, prophylaxis and therapy with the added advantage of timely production. In this context, some companies have already started vaccines and antibodies development against COVID-19 with the assumption that the obtained candidates will prove crucial in future outbreaks.80a In addition, the stably transformed plants were also considered as an option for the generation of injectable vaccines along with other transient expression systems but the time required for the development of antigen-producing lines is the main constraint. However, oral vaccines could be possibly developed by plant-based vaccine technology, using plant cell as an antigen delivery agent and may prove an attractive approach in terms of cost, induction of mucosal immunity and easy delivery.80,81

Live viral vector-based vaccines

These include the vaccines that are based on chemically weakened viruses, which are exploited for carrying antigens or pathogens of interest for inducing the immune response. They induce potent immunity including cell-mediated immunity (https://www.who.int/biologicals/publications/trs/areas/vaccines/typhus/viral_vectors/en/). Commonly adenovirus-based vectors expressing SARS-CoV-2 protein or similar viral vectors are being explored; however, the use of other vectors such as vaccinia virus, the canarypox virus, attenuated poliovirus, attenuated strains of Salmonella, the BCG strain of Mycobacterium bovis, and certain strains of streptococcus that normally exist in the oral cavity is also a possibility. The most promising approach is combining “prime-boost” strategies that utilize different vaccines like recombinant antigens and DNA vaccines together (https://www.who.int/biologicals/publications/trs/areas/vaccines/typhus/viral_vectors/en/). An adenovirus type 5 vector-based vaccine by CanSino Biological Inc./Beijing Institute of Biotechnology that uses a non-replicating viral vector platform has reached Phase 2 (ChiCTR2000031781) and Phase 1 (ChiCTR2000030906) of clinical evaluation (https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Novel_Coronavirus_Landscape_nCoV_11April2020.PDF?ua=1). Former trial uses middle dose (1E11vp); low dose (5E10vp); and placebo (http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=52006), whereas latter trial uses low dose (5E10vp); middle dose (1E11vp) and high dose (1E11vp) (http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=51154) of vaccine candidate. Phase 2 trial is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial with interventional type and parallel study design (http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=52006) whereas phase 1 is a single-center, open and dose-escalation trial with prevention type and non-randomized control of study design (http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=51154).

Using the same platform, the University of Oxford is exploring ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, a derivative of ChAdOx1 virus which is the weakened adenovirus that causes common cold and affects chimpanzees but is not able to replicate in humans, as a vaccine candidate against COVID-19 (Phase 3, ISRCTN89951424) (http://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2020-05-22-oxford-covid-19-vaccine-begin-phase-iii-human-trials). In preclinical trials, modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA)-encoded VLP is being explored by GeoVax/BravoVax, Ad26 (alone or with MVA boost) by Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, MVA-S by DZIF–German Center for Infection Research, adenovirus-based NasoVAX expressing SARS2-CoV S protein by Altimmune, and Ad5S (GREVAX™ platform) by Greffex using non-replicating viral vector platforms (https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Novel_Coronavirus_Landscape_nCoV_11April2020.PDF?ua=1).

Chimeric viral vaccines and membrane vesicle-vaccines are other probable options.26 Both aerosol and oral routes need to be explored as possible modes of administration.26 Until potential vaccine candidates are explored, evaluated, and safe and effective vaccines are developed, preventive measures need to be taken at all levels, i.e., in affected82,83 or containment areas,82 predisposed areas,84,85 affected persons,18,82 or vulnerable groups.84,85 Scientific guidelines pertaining to prevention and control measures need to be implemented until the vaccine trials carried out by various research institutions and vaccine manufacturing companies produce satisfactory results.20,23,39,55 In addition, careful evaluation of vaccine during each step of development is crucial which includes identification of target antigen, route of immunization, correlated-immune protection, various animal models, probable scalability, production facility, determination of target population, forecasting of the outbreak and target product profile.86

Product candidates in development

There are more than 149 vaccines and immunotherapeutics under development, with 132 being at the clinical trial stage and 17 reaching clinical evaluation (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines). Using ChAdOx nCoV-19 as vaccine candidate and employing nonreplicating viral vector platform, University of Oxford/AstraZeneca is currently leading the Phase 3 of clinical evaluation (ISRCTN89951424). An mRNA-based vaccine by Moderna® is believed to induce antibodies against the S proteins of SARS-CoV-2, and a batch of vaccine has been delivered to National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This vaccine was developed 42 days after the DNA sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was disclosed. It has reached Phase 2 of clinical evaluation (NCT04405076). A vaccine candidate, INO-4800, is being evaluated by Inovio Pharmaceuticals®; it is a DNA plasmid vaccine that is at Phase 1 of clinical evaluation (NCT04336410). The other candidate at clinical evaluation is adenovirus type 5 vector being explored by CanSino Biological Inc./Beijing Institute of Biotechnology. It has reached Phase 2 (ChiCTR2000031781) and Phase 1 (ChiCTR2000030906) of clinical evaluation or regulatory approval (https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Novel_Coronavirus_Landscape_nCoV_11April2020.PDF?ua=1).

Johnson and Johnson® is also working on the development of vaccines against COVID-19. It is planning to deactivate the virus to produce a vaccine that triggers an immune response without causing any infection. GlaxoSmithKline® has produced a pandemic vaccine adjuvant platform, through which it is collaborating with other institutes and companies for assessing candidate COVID-19 vaccines. Recombinant DNA vaccines are being investigated by Sanofi® (https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2020/03/13/coronavirus-drug-update-the-latest-info-on-pharmaceutical-treatments-and-vaccines/). A VLP vaccine has been developed by Novavax® (http://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-advances-developmentnovel-covid-19-vaccine). Genexine Inc. is developing a vaccine against COVID-19 using the Hyleukin-7 platform technology, which enhances the immunological responses by fusion of IL-7 to hyFc and designed to hybridize IgG4 and IgD in order to produce a long-acting effect of Fc fusion proteins.87–89 An oral subunit vaccine is being developed by MIGAL Galilee Research Institute. It uses an oral Escherichia coli-based protein expression system of S and N proteins and is in late-stage preclinical development (file:///C:/Users/M%20IQBAL/Downloads/novel-coronavirus-landscape-covid-19fbda851295d245e48d8d0a78b35af7ff.pdf).

Numerous immunotherapeutics are being explored for COVID-19 (Casadevall and Pirofski 2020; Shanmugaraj et al. 2020a).38,60 Antibody-based treatment is being evaluated by Eli Lilly® (using monoclonal antibody LY3127804), Rochi® (Tocilizumab) (https://www.clinicaltrialsarena.com/news/roche-actemra-covid-19-trial/), Sanofi® (Sarilumab) (https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-03-30-07-00-00) besides Temple University Hospital, USA (Gimsilumab) (https://theprint.in/health/us-begins-clinical-trial-of-an-artificial-antibody-for-covid-19-treatment/402978/). These are monoclonal antibody (mAb) based approaches under consideration. Takeda® is also working on antibodies against COVID-19 (https://www.wsj.com/articles/drugmaker-takeda-is-working-on-coronavirus-drug-11583301660). Monoclonal antibodies are preferred because of their specificity and effectiveness. Sarilumab, a rheumatoid arthritis treatment developed by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals®, is being tested for COVID-19 treatment (https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2020/03/13/coronavirus-drug-update-the-latest-info-on-pharmaceutical-treatments-and-vaccines/). Besides, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has started funding vaccine development initiatives for SARS-CoV-2 based on DNA, mRNA, and molecular clamp platforms (https://cepi.net/get_involved/cfps).

Patents on coronavirus vaccines

There are more than 500 patent applications on SARS vaccines, and around 50 for MERS vaccines.50 It is unknown how many of these will become granted patents given that the field is new as of 2020. Numerous vaccines are being explored for COVID-19 (research institutions as well as companies). Around 35 of these organizations have started investigations, with few even reaching clinical trials (Table 1). One of the following strategies is being used: previous experience and technology are being utilized; novel candidates are being exploited.53 Patents like US20060039926 for the live attenuated coronavirus or torovirus vaccines can guide the exploration of such vaccines for COVID-19; however, limitation of re-infection should be taken into consideration. Similarly, patent applications WO2010063685, US20070003577, and US20060002947 representing subunit vaccines based on S protein, its subunits or hybrid peptides can prevent problems of live or attenuated vaccines. Patent WO2015042373 can be explored for virus-like particles (VLPs), WO2005081716 and WO2015081155 for DNA-based vaccines, WO2017070626 and WO2018115527 for mRNA-based vaccines, which have been evaluated in other coronaviruses as detailed in Table 1. In future, there can be an exploration of combined vaccines also as evaluated in patent WO2017176596A1 for rabies and coronaviruses.93

Table 1.

Potential/putative vaccine candidates for COVID-19, inference from self or related coronaviruses

| Viral structure/Candidate | Nature | Role | Patents/potential of similar vaccine candidates | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attenuated/inactivated virus | Live attenuated/inactivated vaccine | After passages/inactivation viruses lose virulence, can be used as vaccines | US20060039926 (live attenuated coronavirus or torovirus vaccines), Potential for vaccine development but chances of reinfection |

26,39,53 |

| Killed virus | Killed vaccine | Killing by physical (ultraviolet light) or chemical means (formaldehyde, β-propiolactone) | Potential for vaccine development but chances of reinfection | 26,39,53 |

| Viral spike glycoprotein (S protein), T cell and B cell epitopes, nucleocapsid protein and/or an immunogenic fragment | Protein subunit vaccine | S glycoprotein helps in binding to host cell through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE2R). Generate antibodies against epitopes. MERS-CoV nucleocapsid protein (N) | WO2010063685 (S-Trimer subunit vaccine: S protein immunogen and an oil-in-water emulsion adjuvant) US20070003577 (TriSpike SARS coronavirus vaccine: recombinant full-length trimeric S protein) US20060002947 (hybrid peptides: Ii-Key/MHC II SARS hybrids for COVID-19 viral peptide vaccine). Targeting S2 linear epitopes more effective than S1 epitope EP3045181A1 Used as a vaccine as well as a method of inducing a protective immune response against MERS-CoV. |

25,27,90 https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/clover-and-gsk-announce-research-collaboration-to-evaluate-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-candidate-with-pandemic-adjuvant-system; https://storage.googleapis.com/wzukusers/user-26831283/documents/5e57ed391b286sVf68Kq/PR_Generex_Coronavirus_Update_2_27_2020.pdf. |

| Transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2), 3CLpro, and PLpro | Enzymes | TMPRSS2: Protease of the host cell that cleaves S protein and helps in binding to ACE2R; 3CLpro: The main coronavirus protease; PLpro: Papain-like protease. Both 3CLpro and PLpro help in proteolysis of viral polyprotein into functional units. Small-molecule inhibitor against MERS-CoV |

Potential for vaccine development but yet to be explored. CN105837487A Inhibitor targets basic structure of main protease of the coronavirus MERS-CoV, helpful for prevention of coronavirus infections like MERS and SARS. |

31,53,91 |

| Virus-like Particles (VLPs) | Molecules closely resembling coronaviruses, but are noninfectious as they do not contain viral genetic material | Virus-like particle vaccines | WO2015042373 (MERS-CoV nanoparticle VLPs having at least one trimer of a S protein, produced from baculovirus overexpression in Sf9 cells). COVID-19 recombinant nanoparticle vaccine (S protein of SARS-CoV-2, adjuvant Matrix-M) |

http://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-advances-development-novel-covid-19-vaccine. |

| Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) | Genetic material | DNA-based vaccines | WO2005081716 (chimeric nucleic acids encoding endoplasmic reticulum chaperone polypeptide calreticulin linked antigenic polypeptide or peptide from SARS-CoV) WO2015081155 (DNA-based vaccines targeting MERS-CoV spike protein. INO-4800 DNA based vaccine for COVID-19. Recombinant DNA vaccines are also being studied. |

http://ir.inovio.com/news-and-media/news/press-release-details/2020/Inovio-Accelerates-Timeline-for-COVID-19-DNA-Vaccine-INO-4800/default.aspx; https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2020/03/13/coronavirus-drug-update-the-latest-info-on-pharmaceutical-treatments-and-vaccines/. |

| Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) | Genetic material | mRNA-based vaccines | WO2017070626 (mRNAs coding viral full-length S, S1, or S2 proteins of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV virus. mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, targets a prefusion stabilized form of the S protein associated with SARS-CoV-2. WO2018115527 (mRNA coding for antigen of a MERS CoV, like S protein or a S, it subunit S1, or E, M, N protein) |

https://investors.modernatx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/moderna-ships-mrna-vaccine-against-novel-coronavirus-mrna-1273 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; angiotensin AT2 receptor | Enzyme and protein | ACE2R is a viral receptor protein on the host respiratory surface epithelial cells and helps in binding to S protein of SARS-CoV-2. AT2 is an effector that regulates blood pressure and volume of the cardiovascular system | Potential targets for vaccine development but yet to be explored | 25,28,31,53 |

| Immunoglobulins, monoclonal antibodies, interferons | Protein antibodies, cytokines | Immunoglobulins and interferons kill the coronavirus by neutralization or block its mechanisms of pathogenesis, passive immunotherapy against COVID-19 | Immunoglobulins synthetic or recombinant and interferons neutralizing SARS-CoV-2, immunoglobulins blocking FcR, monoclonal antibody (CR3022), US20190351049A1 Monoclonal antibodies against S protein of MERS Coronavirus, helpful in inhibiting or neutralizing MERS-CoV activity |

24,38,53,57,60,61,92 |

Although global research has focused on various epidemiological, genomic, and therapeutic aspects of COVID-19, development of vaccines and early prophylactic modalities have become a priority at this moment (summarized in Table 1), due to the lack of vaccines as well as an alarming rise in the incidence of COVID-19, worldwide.2,94,95

An overview on designing and developing COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An overview of the design and development of COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

Challenges for developing SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

There are huge challenges for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Emergencies due to frequent and continuously emerging new COVID-19 cases have caused a panic around the globe. Lack of complete understanding of SARS-CoV-2 and absence of information and research on putative vaccine candidates adds to the challenge.96 In addition, the lack of sufficient time for evaluation of the safety and efficacy of the candidates may undermine vaccine quality.94,96 Although researchers are working around the clock to produce an effective vaccine that would be available as soon as possible, sentiments associated with the heavy death toll associated with the ongoing illness may prove a major hurdle in the strict implementation of the regulations proposed by the regulatory bodies and approving authorities. Proper evaluation of immune response and avoiding any untoward immune reaction that may prove harmful to the body are very important.75,77 ADE may affect immune response.50 Immune responses aggravation by ADE may affect efforts in developing vaccine and hence require focus while exploring vaccines against COVID-19.50 Hence, utmost care must be taken before finalizing a decision regarding any developed vaccines, clinical trials, or market commercialization.94,96 In addition, robust infrastructure and financial support needed for the purpose are also major concerns, and must be addressed properly. Even if a large, international, multi-site, individually randomized controlled clinical trial is conducted, enabling the concurrent evaluation of the benefits and risks of each promising candidate vaccine will still take 3‒6 months after the trial (https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Outline_CoreProtocol_vaccine_trial_09042020.pdf?ua=1), and the randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-center study for determining efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of the vaccine candidate can take up to 6 months after the trial (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04324606). However, the actual commercial vaccine under emergency use or similar protocols may be available by early 2021 which otherwise usually takes 10 years for development.97 Clinical trials involving hundreds of healthy adult volunteers in phase I, thousands of adults in disease area in phase II and tens of thousands such people in area where the disease has spread will take around 18 months (6‒8 months for each phase) (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/vaccine-covid-19-coronavirus-pandemic-healthcare/).

Conclusion and future prospects

Zoonotic viruses are an unavoidable threat to humankind, which always pose new challenges to prevent and control the associated disease without or with minimum loss of human lives. Prevention is always considered better than cure, which can be accomplished effectively by immunization of the naïve population to save human lives. The world is suffering due to COVID-19, mainly because of the lack of vaccines and therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. An alarming rise in confirmed COVID-19 cases, severity of the disease, and global spread has resulted in a huge demand and necessity for the development of prophylactics and therapeutics. Global research and investigations are focusing on exploring vaccine candidates and therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2 in a few studies, with little success. Availability of genomic and structural data has encouraged the immuno-pharmacological evaluation of vaccine candidates. In addition to convalescent sera or plasma therapy and immunoglobulin administration, live attenuated or killed vaccines are evaluated for this purpose. Potential structural and non-structural proteins are being explored as subunit vaccines, mRNA- or DNA-based vaccines, or novel recombinant vaccines. Viral-like particle- (VLP-), vector- and non-vector–based vaccines are other possibilities of utmost importance. Many companies have come up with encouraging vaccines, such as mRNA-based vaccines, subunit vaccines, and VLP vaccines; however, there is enough scope and demand for exploring antigenic structures and therapeutic modalities for developing specific and effective curative, preventive, and control strategies for COVID-19. Although a few international companies and agencies have decided to fund this noble cause, a collaborative effort by government, semi-government, and private organizations is crucial to meet the increasing demand. However, by the time vaccines for COVID-19 become available commercially, the ongoing pandemic might have subsided, but the efforts and knowledge acquired during vaccine development would help the scientific fraternity to fight against such pandemics in the near future. Development of a highly safe and efficacious drug or vaccine for COVID-19 that can prevent or minimize the suffering of the global population is the need of the hour. Sufficient time and due care must be taken before the launch of any vaccine along with a genuine approval from the concerned authorities to avoid any untoward effect or vaccine-related health-care accidents. After the pandemic subsides, it is highly unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 will disappear, rather it is likely to return next year, and thus a vaccine will still benefit that great majority of people who have not been exposed to the virus. Further, considering the changing nature of the coronaviruses, regular updating of COVID-19 vaccines may be required. Considering challenges for the development of COVID-19 vaccines probability of successful development is unknown in this early field and that the timing of licensure of a safe and effective vaccines also is unknown.

Acknowledgments

All the authors acknowledge and thank their respective Institutes and Universities.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

All authors declare that there exist no commercial or financial relationships that could, in any way, lead to a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, et al. China novel coronavirus investigating and research team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS, de Groot RJ, Drosten C, Gulyaeva AA, Haagmans BL, Lauber C, Leontovich AM, Neuman BW, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . WHO statement regarding cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China. Beijing. WHO; 2020a. Jan 9 [accessed 2020 Jan 11]. https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-ofpneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china.

- 5.WMHC . Wuhan Municipal Health Commission. Report of clustering pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan City. 2019. [accessed 2020 Jan 14]. (http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/front/web/showDetail/2019123108989. opens in new tab).

- 6.China CDC 2020 . Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The 2019-nCoV Outbreak Joint Field Epidemiology Investigation Team, Li Q. Notes from the field: an outbreak of NCIP (2019-nCoV) infection in China — wuhan, Hubei Province, 2019-2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:79–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHC . National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Epidemic Prevention and Control of Dynamic; 2020. [accessed 2020 Mar 29]. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202002/ac1e98495cb04d36b0d0a4e1e7fab545.shtml. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.CDC . Center for disease control and prevention. 2020a. [accessed 2020 Mar 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

- 9.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC, Poon RW, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, Chu H, To KK, Yuan S, Yuen KY.. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):221–36. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, Hu Y, Tao ZW, Tian JH, Pei YY, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–69. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–73. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhama K, Patel SK, Pathak M, Yatoo MI, Tiwari R, Malik YS, Singh R, Sah R, Rabaan AA, Bonilla-Aldana DK, et al. An update on SARS-COV-2/COVID-19 with particular reference on its clinical pathology, pathogenesis, immunopathology and mitigation strategies – a review. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen ZM, Fu JF, Shu Q, Chen YH, Hua CZ, Li FB, Lin R, Tang LF, Wang TL, Wang W, et al. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. World J Pediatr. 2020;16(3):240–46. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ralph R, Lew J, Zeng T, Francis M, Xue B, Roux M, Toloue Ostadgavahi A, Rubino S, Dawe NJ, Al-Ahdal MN, et al. 2019-nCoV (Wuhan virus), a novel Coronavirus: human-to-human transmission, travel-related cases, and vaccine readiness. J Infect Dev Countr. 2020;14(1):3–17. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC 2020b . Centers for disease control and prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Prevention & Treatment. 2020. [accessed 2020 Mar 15]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/prevention-treatment.html.

- 21.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):401–02. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus infections-more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020;323(8):707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO 2020b . World Health Organization Novel coronavirus – China. 2020. Jan 12 [accessed 2020 Jan 19]. http://www.who. int/csr/don/12-january-2020-novel-coronavirus-china/en/.

- 24.Tian X, Li C, Huang A, Xia S, Lu S, Shi Z, Lu L, Jiang S, Yang Z, Wu Y, et al. Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):382–85. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, Graham BS, McLellan JS. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367(6483):1260–63. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shang W, Yang Y, Rao Y, Rao X. The outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia calls for viral vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-0170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed SF, Quadeer AA, McKay MR. Preliminary identification of potential vaccine targets for the COVID-19 Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Based on SARS-CoV immunological studies. Viruses. 2020;12(3):E254. doi: 10.3390/v12030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7):e00127–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(1):281–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50(3):e13209. doi: 10.1111/eci.13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coutard B, Valle C, de Lamballerie X, Canard B, Seidah NG, Decroly E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res. 2020;176:104742. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Zheng X, Tong Q, Li W, Wang B, Sutter K, Trilling M, Lu M, Dittmer U, Yang D. Overlapping and discrete aspects of the pathology and pathogenesis of the emerging human pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):491–94. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109:102433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R, Dadar M, Malik YS, Singh KP, Chaicumpa W. COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020b:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1735227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R, Sircar S, Bhat S, Malik YS, Singh KP, Chaicumpa W, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Coronavirus disease 2019 – COVID-19. Preprints. 2020c;2020a:2020030001. doi: 10.20944/preprints202003.0001.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malik YS, Sircar S, Bhat S, Sharun K, Dhama K, Dadar M, Tiwari R, Chaicumpa W. Emerging novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)-Current scenario, evolutionary perspective based on genome analysis and recent developments. Vet Q. 2020;40:68–76. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2020.1727993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik YS, Sircar S, Bhat S, Vinodhkumar OR, Tiwari R, Sah R, Rabaan AA, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Dhama K. Emerging coronavirus disease (COVID-19), a pandemic public health emergency with animal linkages: current status update. Indian J Anim Sci. 2020;90(3):xx. doi: 10.20944/preprints202003.0343.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020:138003. doi: 10.1172/JCI138003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pang J, Wang MX, Ang IYH, Tan SHX, Lewis RF, Chen JI, Gutierrez RA, Gwee SXW, Chua PEY, Yang Q, et al. Potential rapid diagnostics, vaccine and therapeutics for 2019 novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):E623. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roback JD, Guarner J. Convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19: possibilities and challenges. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev Res. 2020. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK. The novel Coronavirus: a bird’s eye view. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020;11(2):65–71. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2020.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol J. 2019;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gralinski LE, Menachery VD. Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses. 2020;12(2):135. doi: 10.3390/v12020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B –coronavirus, including 2019-nCoV. Nat Microbiol. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morse JS, Lalonde T, Xu S, Liu WR. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem. 2020;21(5):730–38. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du L, He Y, Zhou Y, Liu S, Zheng BJ, Jiang S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV–a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y, Jiang S, Du L. Prospects for a MERS-CoV spike vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(8):677–86. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1506702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Kruger N, Muller M, Drosten C, Pohlmann S. The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular proteases TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. bioRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.01.31.929042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tetro JA. Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes Infect. 2020;22(2):72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller A, Reandelar MJ, Fasciglione K, Roumenova V, Li Y, Otazu GH. Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: an epidemiological study. medRxiv. 2020. Jan 1. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20042937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myint A, Jones T. Possible treatment of Covid-19 with a therapeutic vaccine. Vet Rec. 2020;186(13):419. doi: 10.1136/vr.m1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu C, Zhou Q, Li Y, Garner LV, Watkins SP, Carter LJ, Smoot J, Gregg AC, Daniels AD, Jervey S, et al. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for COVID-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6(3):315–31. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beigel JH, Voell J, Kumar P, Raviprakash K, Wu H, Jiao JA, Sullivan E, Luke T, Davey RT Jr.. Safety and tolerability of a novel, polyclonal human anti-MERS coronavirus antibody produced from transchromosomic cattle: a phase 1 randomised, double-blind, single-dose-escalation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(4):410–18. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.WHO . Report of the WHO-China joint mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020c. [accessed 2020 Mar 29]. Mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. pp 1–40.

- 56.WHO . Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. 2020d. [accessed 2020 Mar 15]. www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severeacute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, Cheng H, Deng T, Fan YP, Fang C, Huang D, Huang LQ, Huang Q; for the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University Novel Coronavirus Management and Research Team, Evidence-Based Medicine Chapter of China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care (CPAM), et al.. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Q, Wang Y, Qi C, Shen L, Li J. Clinical trial analysis of 2019-nCoV therapy registered in China. J Med Virol. 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu K, Fang YY, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang MF, Ma JP, Xiao W, Wang YN, Zhong MH, Li CH, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shanmugaraj B, Siriwattananon K, Wangkanont K, Phoolcharoen W. Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020a;38(1):10–18. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fu Y, Cheng Y, Wu Y. Understanding SARS-CoV-2-mediated inflammatory responses: from mechanisms to potential therapeutic tools. Virol Sin. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00207-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu RM, Hwang YC, Liu IJ, Lee CC, Tsai HZ, Li HJ, Wu HC. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0592-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu L, Wei Q, Lin Q, Fang J, Wang H, Kwok H, Tang H, Nishiura K, Peng J, Tan Z, et al. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4(4):e123158. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang B, Zhou X, Zhu C, Feng F, Qiu Y, Feng J, Jia Q, Song Q, Zhu B, Wang J. Immune phenotyping based on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and IgG predicts disease severity and outcome for patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.12.20035048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, Liu W, Liao X, Su Y, Wang X, Yuan J, Li T, Li J, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pahl JH, Kwappenberg KM, Varypataki EM, Santos SJ, Kuijjer ML, Mohamed S, Wijnen JT, van Tol MJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, Egeler RM, et al. Macrophages inhibit human osteosarcoma cell growth after activation with the bacterial cell wall derivative liposomal muramyl tripeptide in combination with interferon-γ. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(5):269–70. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao QY, Chen YX, Fang JY. Novel coronavirus infection and gastrointestinal tract. J Dig Dis. 2019:2020. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roper RL, Rehm KE. SARS vaccines: where are we? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8(7):887–98. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Graham RL, Donaldson EF, Baric RS. A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(12):836–48. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi SQ, Peng JP, Li YC, Qin C, Liang GD, Xu L, Yang Y, Wang JL, Sun QH. The expression of membrane protein augments the specific responses induced by SARS-CoV nucleocapsid DNA immunization. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(11):1791–98. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu WJ, Zhao M, Liu K, Xu K, Wong G, Tan W, Gao GF. T-cell immunity of SARS-CoV: implications for vaccine development against MERS-CoV. Antiviral Res. 2017;137:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ng OW, Chia A, Tan AT, Jadi RS, Leong HN, Bertoletti A, Tan YJ. Memory T cell responses targeting the SARS coronavirus persist up to 11 years post-infection. Vaccine. 2016;34(17):2008–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramaiah A, Arumugaswami V. Insights into cross-species evolution of novel human coronavirus 2019-nCoV and defining immune determinants for vaccine development. BioRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.01.29.925867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bukreyev A, Lamirande EW, Buchholz UJ, Vogel LN, Elkins WR, St Claire M, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, Collins PL. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2122–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16501-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song Z, Xu Y, Bao L, Zhang L, Yu P, Qu Y, Zhu H, Zhao W, Han Y, Qin C. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses. 2019;11(1):59. doi: 10.3390/v11010059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen WH, Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME. Potential for developing a SARS-CoV receptor-binding domain (RBD) recombinant protein as a heterologous human vaccine against coronavirus infectious disease (COVID)-19. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1740560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ji H, Yan Y, Ding B, Guo W, Brunswick M, Niethammer A, SooHoo W, Smith R, Nahama A, Zhang Y. Novel decoy cellular vaccine strategy utilizing transgenic antigen-expressing cells as immune presenter and adjuvant in vaccine prototype against SARS-CoV-2 virus. Med Drug Discov. 2020;5:100026. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shanmugaraj B, Malla A, Phoolcharoen W. Emergence of novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: need for rapid vaccine and biologics development. Pathogens. 2020;9(2):E148. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9020148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosales-Mendoza S, Márquez-Escobar VA, González-Ortega O, Nieto-Gómez R, Arévalo-Villalobos JI. What does plant-based vaccine technology offer to the fight against COVID-19? Vaccines (Basel). 2020a;8(2):E183. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosales-Mendoza S. Will plant-made biopharmaceuticals play a role in the fight against COVID-19? Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020b:1–4. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1752177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen W, Wang Q, Li YQ, Yu HL, Xia YY, Zhang ML, Qin Y, Zhang T, Peng ZB, Zhang RC, et al. Early containment strategies and core measures for prevention and control of novel coronavirus pneumonia in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;54(3):1–6. Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j..0253-9624.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.She J, Jiang J, Ye L, Hu L, Bai C, Song Y. 2019 novel coronavirus of pneumonia in Wuhan, China: emerging attack and management strategies. Clin Transl Med. 2020;9(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40169-020-00271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shen K, Yang Y, Wang T, Zhao D, Jiang Y, Jin R, Zheng Y, Xu B, Xie Z, Lin L, et al. China National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Diseases; National Center for Children’s Health, Beijing, China; Group of Respirology, Chinese Pediatric Society, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Medical Doctor Association Committee on Respirology Pediatrics; China Medicine Education Association Committee on Pediatrics; Chinese Research Hospital Association Committee on Pediatrics; Chinese Non-government Medical Institutions Association Committee on Pediatrics; China Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Committee on Children’s Health and Medicine Research; China News of Drug Information Association, Committee on Children’s Safety Medication; Global Pediatric Pulmonology Alliance. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: experts’ consensus statement. World J Pediatr. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00343-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang HS, Yao ZQ, Wang WM. [Emergency management of prevention and control of novel coronavirus pneumonia in departments of stomatology]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;55:E002.Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112144-20200205-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu X, Xiang Y, Du H, Wing-Kin Wong G. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children - Understanding the immune responses and controlling the pandemic. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pai.13267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]