ABSTRACT

Background

Aside from personal beliefs, women’s intention to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination can be influenced by their perceived risks of developing cervical cancer and daily communication.

Objectives

This study incorporated perceived risks and communication factors (i.e., media attention and interpersonal discussion) with theory of planned behavioral factors (i.e., attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control) to predict women’s intentions to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination in China.

Methods

A quantitative survey was conducted with 417 female university students in China. The Structural Equation Modeling analysis was applied to test the proposed extended TPB model and to examine the hypotheses in Mplus software.

Results

The results showed that the original theory of planned behavior factors and the perceived risk toward cervical cancer were positively related to their intention to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination. Moreover, media attention and interpersonal discussion positively affected people’s attitudes toward human papillomavirus vaccination and subjective norm, which further influenced their intentions to uptake human papillomavirus vaccination.

Conclusion

This study can help better understand unvaccinated eligible vaccine recipients and identify the differences between individuals who are likely and unlikely to get vaccinated.

KEYWORDS: HPV vaccination, theory of planned behavior, media attention, interpersonal discussion, perceived risk

Introduction

Cervical cancer is among the most common cancers among women worldwide, with an especially high occurrence in developing countries.1 According to the Catalan Institute of Oncology,2 China has the highest number of patients with cervical cancer, with 106,430 new cases and 47,739 deaths a year. This number accounts for over 28% of the world’s cervical cancer cases.2 Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a major cause of cervical cancer.3,4 Extensive clinical trials demonstrated that vaccination before sexual debut is effective in ensuring protection against the target HPV virus.5 However, HPV vaccine coverage rates among the target population in China are quite low. Studies among the general population of Chinese women showed that only 20% to 30% have heard of HPV and HPV vaccinations, and around 50% of them are willing to accept HPV vaccination.6,7 Hence, to ensure a successful application of an HPV vaccination program in mainland China, studies exploring willingness to be vaccinated among young Chinese women are imperative. Since extensive previous research has revealed that individuals’ actual preventive behavior is largely predicted by the behavioral intentions,8–10 the aim of this study was to examine the essential factors affecting young Chinese women’s intention to uptake HPV vaccination.

Studies on HPV vaccination have been conducted in several countries, including China.1,6,11-14 However, very few studies in China have investigated individuals’ uptake intention toward HPV vaccination from a theoretical and health communication perspective. Considering that the theory of planned behavior (TPB) is one of the most common theories used to predict individuals’ health behaviors,15,16 this study applies the TPB model as the theoretical underpinning to examine how behavioral factors (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control [PBC]) are related to young Chinese women’s intention to uptake HPV vaccination. In addition to TPB factors, the potential background factors such as individual’s risk perceptions of cervical cancer, media attention, and interpersonal discussion are included in the TPB model considering that these factors can shape individuals’ behavioral intentions on health-related issues.17,18 Therefore, this study adopted Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to investigate the relationships between the components of the original and extended TPB models, to examine whether or not the additional constructs improved the prediction of young Chinese women’s intention to uptake HPV vaccination.

Theoretical model and hypothesis development

Theory of planned behavior model (TPB model)

Since TPB model has been widely applied to assess the personal, psychological, and social effects on individuals’ intention and behavior across cultures, it was often applied to examine intention toward HPV vaccination.19 It postulates that an individual’s behavioral intention is affected by three behavioral factors: attitude, subjective norm, and PBC.

Attitude refers to the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of a behavioral object.20 Based on TPB, when people hold positive attitudes toward certain behaviors, they become more willing to engage in the behavior.19,21 Therefore, it is expected that young Chinese women with a positive attitude toward HPV vaccination would more likely uptake HPV vaccination than those with negative attitudes.

Subjective norm is defined as perceived prevalence of a behavior and the perception of others’ expectation toward the performance of the behavior.19 According to TPB, if a person believes that their social referents (such as parents and friends) consider certain behaviors as imperative, they tend to have higher intentions to perform such behaviors.22 Scholars noted that China is a collectivistic society23,24 and people in such societies are likely to adhere to behaviors deemed appropriate by the majority.25 Therefore, it is reasonable to expect subjective norm to play an important role in shaping young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake HPV vaccination.

PBC refers to the perceived ability to engage in the behavior of interest.19 Following the TPB model, individuals are more likely to perform a behavior if they are more confident of being able to perform it.26 In this study, consumers who perceived that they have control over their HPV vaccination behavior would have greater intention to uptake HPV vaccination.

A meta-analysis of TPB studies showed that attitudes, subjective norm, and PBC accounted for 39% variance in intentions, whilst intentions accounted for 25% variance in behavior.27 Therefore, the following hypotheses were posited:

H1a: Attitude toward HPV vaccination is positively associated with young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake HPV vaccination.

H1b: Subjective norm is positively associated with young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake HPV vaccination.

H1 c: PBC is positively associated with young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake HPV vaccination.

Linking risk perception to theory of planned behavior model

Though the TPB has been successfully used for predicting intentions in several topics, it should include additional constructs in order to better predict behavioral intentions.19 The first component to be included in TPB model is the risk perception, which refers to an individual’s subjective perception of their probability to develop cervical cancer.28 Previous research has shown that individuals who perceive that they are at risk are more intent to engage in protective behaviors compared with their counterparts.29 For example, previous studies found that women’s perceived risk of breast cancer was positively associated with their intention to engage in mammography screening.17,30 Therefore, this study expected young Chinese women who perceived the risk of developing cervical cancer to have a greater tendency to uptake HPV vaccination. Moreover, existing studies have shown that public risk perception is associated with their health-related attitudes as well.31,32 If young women perceived the risk of developing cervical cancer, they would be more likely to hold a positive attitude toward preventive measures, such as HPV vaccination. As such, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H2a: Risk perception of developing cervical cancer is positively associated with young Chinese women’s intentions to uptake HPV vaccination.

H2b: Risk perception of developing cervical cancer is positively associated with young Chinese women’s attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

Linking media attention to theory of planned behavior model

After HPV vaccination was officially licensed for use in mainland China, HPV vaccination-related information provided by the media increased sharply.33 Since the previous study has showed that the including media attention can enable a higher model fit than that of the original TPB model,15 the second component included in TPB model in this study was media attention, which refers to the level of conscious attention that people give to a type of media message.34 According to the information-processing model,35 the more attention individuals pay to messages generated by media outlets, the more likely that their attitude will be reinforced or changed.36,37 Ho, Scheufele, and Corley32found that attention to science-related messages on mass media was positively associated with people’s attitude toward nanotechnology. As such, we assume that the more attention young Chinese women paid to HPV vaccination-related news, the more likely they would be to hold positive attitudes toward it. Moreover, media attention would affect perceived subjective norm as well. The Influence of Presumed Media Influence (IPMI) model suggests that individuals often extrapolate the reach of media messages according to their own exposure to these messages, assume that these messages would influence other people, and they would spend cognitive effort on the messages and be affected by them.38 In this vein, if young Chinese women pay attention to the HPV vaccination messages via media platforms, they may perceive that others are likely to uptake HPV vaccination as they assume that these messages would reach them and affect them. Thus, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H3a: Media attention to HPV vaccination is positively associated with young Chinese women’s attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

H3b: Media attention to HPV vaccination is positively associated with young Chinese women’s perceived subjective norm toward HPV vaccination.

Linking interpersonal discussion to theory of planned behavior model

Aside from the media channels, individuals can develop various attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors by discussing with nearby social agents such as family members, friends, or colleagues.18 Through discussion with others, individuals can learn more about other groups and then modify their beliefs and attitude. For example, a past study found that females who discussed with friends about breast cancer were more likely to have a positive attitude toward mammography.39 As such, we argue that interpersonal discussion on HPV vaccination has a positive effect on young Chinese women’s attitude toward HPV vaccination. Furthermore, interpersonal discussion may affect perceived subjective norms, which consequently changes prevention behaviors. Frank et al.40 found that discussion about condoms positively predicted individuals’ attitudes and subjective norms toward condom use, which, in turn, predicted their intention to use condoms. In this vein, through discussing HPV vaccination with others, young women may perceive that their friends and families are willing to uptake HPV vaccination or expecting them to uptake HPV vaccination. Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H4a: Interpersonal discussion about HPV vaccination is positively associated with young Chinese women’s attitudes toward HPV vaccination.

H4b: Interpersonal discussion about HPV vaccination is positively associated with young Chinese women’s perceived subjective norm toward HPV vaccination.

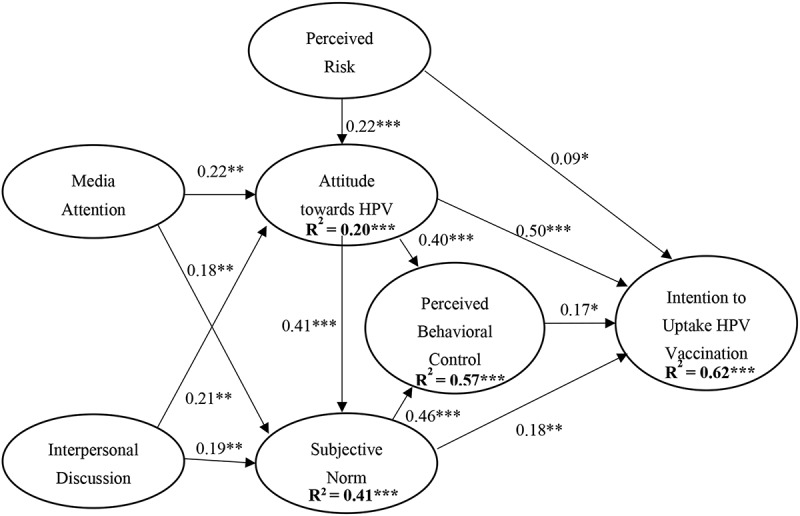

As a result, an extended TPB model was proposed based on the above hypotheses. Figure 1 demonstrates this proposed model to be examined in the following parts of the study.

Figure 1.

Proposed extended TPB model for uptaking HPV vaccination

Materials and methods

Data collection

A quantitative study was used to examine the research model and test the hypotheses. We employed a self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaire for data collection, which was conducted during May 2018. Since the study was a preliminary work for a larger project on this topic, we initially used a convenience sampling method to recruit respondents. The target participants were female university students in Kunming, a medium-sized city in Southwest China. We distributed a survey questionnaire to the target participants in the campus canteens of eight public universities in Kunming. To gather more data, respondents were also asked to invite their classmates and friends to take the survey. Before the survey, all the participants were asked to provide written informed consent of the study. Those who successfully completed the survey were given a small gift as a token of appreciation.

A total of 465 young women from eight public universities in Kunming city responded to the survey. After the data were cleaned, the survey finally included 417 valid respondents. The mean age of the participants was 21.64 (SD = 2.02) years. Most of them were undergraduate students (n = 325, 77.9%), and only 71 (17%) reported a sexual encounter history.

Measures

The questionnaire included seven constructs that were validated in previous studies. Intention to uptake HPV vaccination was evaluated by three items adapted from Kim, Jang, and Kim39 Attitude toward HPV vaccination was measured using four items adapted from Kim and Nan (2016).4,5,Subjective norm was measured using four items from Park and Smith (2007).5,41 Risk perception was measured using two items from Lee et al.17 Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement on the above items based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Media attention was measured using four items from Lin et al.18 Respondents were asked to indicate how much attention they pay to the information related to HPV vaccination in newspapers, television, Internet, and social media (1 = no attention at all, 5 = very close attention). Interpersonal discussion was measured using three items from Lin et al.18 Respondents were asked to report the frequency of their discussion with family, friends, and classmates about HPV vaccination-related issues (1 = never, 5 = all the time).

Data analysis

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied to test the extended TPB model proposed by this study, in order to examine the factors that influence young Chinese women’s intention to uptake HPV vaccination. According to Anderson and Gerbing’s29 two-step analysis, measurement model testing was first conducted to examine the uni-dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the multiple-item measures of the involved constructs before using structural model testing to examine the extended TPB model with the causal relationships between the predicting variables and the intention to uptake HPV vaccination. All the SEM analyses were performed in Mplus 6.0.42

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

Goodness-of-fit was first assessed in both CFA and SEM testing. Chi-square test (χ2) is the most common index for accessing the goodness-of-fit of a model.43 However, since Chi-square test is very sensitive to sample size,44 normed Chi-square (χ2/df) was calculated to reduce the bias. Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller (2003)45 stated that this ratio indicates a good fit when χ2/df ≤2 while it indicates an acceptable fit when χ2/df = 3. Other fit indices were also adopted to ensure the acceptability of the proposed and revised models, including comparative fit index (CFI), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). Previous researchers recommended that an acceptable model fit is a combination of CFI value greater than approximately.95 and an SRMR value smaller than.08 or an RMSEA value smaller than.06.46,47 The original CFA model had a fair model fit (See Table 1). The standardized factor loading for each of the measurement item in the CFA model is shown in Table 2. Hair et al.48 suggested using a cutoff of 0.4 in order to achieve a fair factor loading for practical significance in a sample of 200 participants. Considering the sample size in this study, two items (MA1 and SN4) with standardized factor loadings below 0.4 were removed from the original CFA model. Factor analysis was performed again with the revised CFA model, for which the model fit and standardized factor loadings were both satisfactory (See Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

The Fit Indices of CFA and Structural Model Testing

| χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Values | N/A | N/A | >.050 | < 3.000 | > 0.950 | < 0.060 | < 0.080 |

| Original CFA | 622.412 | 231 | <.001 | 2.694 | 0.916 | 0.064 | 0.060 |

| Revised CFA | 382.928 | 188 | <.001 | 2.037 | 0.956 | 0.050 | 0.051 |

| Proposed Extended TPB Model | 583.367 | 194 | <.001 | 3.007 | 0.911 | 0.069 | 0.102 |

| Revised Extended TPB Model | 423.643 | 194 | <.001 | 2.184 | 0.948 | 0.053 | 0.060 |

Table 2.

Standardized loadings of indicators in Confirmatory Factor Analysis (n = 417)

| Original CFA model |

Revised CFA model |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Items | Standardized loadings | Items | Standardized loadings |

| Media Attention | MA1 | 0.39 | - | - |

| MA2 | 0.52 | MA2 | 0.49 | |

| MA3 | 0.88 | MA3 | 0.89 | |

| MA4 | 0.83 | MA4 | 0.82 | |

| Interpersonal Discussion | ID1 | 0.58 | ID1 | 0.58 |

| ID2 | 0.94 | ID2 | 0.94 | |

| ID3 | 0.76 | ID3 | 0.76 | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1 | 0.83 | SN1 | 0.84 |

| SN2 | 0.86 | SN2 | 0.86 | |

| SN3 | 0.40 | SN3 | 0.41 | |

| SN4 | 0.20 | - | - | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | PBC1 | 0.74 | PBC1 | 0.74 |

| PBC2 | 0.64 | PBC2 | 0.64 | |

| PBC3 | 0.80 | PBC3 | 0.80 | |

| PBC4 | 0.49 | PBC4 | 0.49 | |

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.81 | AT1 | 0.81 |

| AT2 | 0.76 | AT2 | 0.76 | |

| AT3 | 0.71 | AT3 | 0.71 | |

| AT4 | 0.78 | AT4 | 0.78 | |

| Perceived Risk | PR1 | 0.79 | PR1 | 0.79 |

| PR2 | 0.76 | PR2 | 0.76 | |

| Intention to Uptake HPV Vaccination | IN1 | 0.91 | IN1 | 0.91 |

| IN2 | 0.93 | IN2 | 0.93 | |

| IN3 | 0.73 | IN3 | 0.72 | |

The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of the involved constructs in the revised CFA model are summarized in Table 3. These constructs were reported to be reliable with a good Cronbach’s alpha values higher than 0.7.49 The bivariate correlations between all these constructs were statistically significant at either p < .01 or p < .001 level. However, none of the correlations reached the problematic level of 0.70; therefore, no corrections were made for multicollinearity between these predictors.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix in Revised CFA Model (n = 417)

| Constructs | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Media Attention | 2.46 | 0.85 | 0.771 | ||||||

| 2 | Interpersonal Discussion | 2.35 | 0.82 | .569*** | 0.782 | |||||

| 3 | Subjective Norm | 3.50 | 0.63 | .336*** | .402*** | 0.723 | ||||

| 4 | Perceived Behavioral Control | 3.60 | 0.63 | .372*** | .397*** | .527*** | 0.728 | |||

| 5 | Attitude | 3.65 | 0.53 | .264*** | .277*** | .482*** | .511*** | 0.851 | ||

| 6 | Perceived Risk | 2.61 | 0.73 | .129** | .153** | .172*** | .216*** | .217*** | 0.747 | |

| 7 | Intention to Uptake HPV Vaccination | 3.60 | 0.67 | .396*** | .445*** | .530*** | .546*** | .659*** | .276*** | 0.878 |

Note: The Cronbach’s alpha values are shown in the diagonal line. SD, standard deviation. **p <.01, ***p <.001.

Structural model testing

The proposed extended TPB model was then examined using the SEM method. The results of various goodness-of-fit indices only suggested a fair model fit for this extended TPB model (see Table 1). In order to achieve a satisfactory fit for the structural model, the proposed TPB model was revised based on the model improvement suggestions from Mplus. Figure 2 demonstrates the results of the revised extended TPB model. The standardized path coefficients of the attitude of an individual toward HPV vaccination (β = 0.50, p < .001), the PBC of an individual (β = 0.17, p = .022), subjective norm (β = 0.18, p = .003), and perceived risk of developing cervical cancer (β = 0.09, p = .048) were all statistically significant for their intention to uptake HPV vaccination. Furthermore, a significantly large squared multiple correlation (R2) of 0.62 (p < .001) was reported in the intention of an individual to uptake HPV vaccination. This implied that the components of the extended TPB model in this study can explain a total of 62% variance in the intention of an individual to uptake HPV vaccination. Thus, H1a, H1b, H1 c, and H2a were all supported in the proposed extended TPB structural model.

Figure 2.

Revised extended TPB model for uptaking HPV vaccination. The solid line indicates significant path with * p <.05, ** p <.01, and *** p <.001. The dashed line indicates non-significant path with p >.05

Additionally, the attitude of an individual toward HPV vaccination was significantly affected by an individual’s attention to HPV news via the media (β = 0.22, p = .001), interpersonal discussion to HPV (β = 0.18, p = .009), as well as perceived risk of developing cervical cancer (β = 0.22, p < .001). These three constructs explained a total of 20% (p < .001) of the variance in their attitude toward HPV vaccination. These findings supported H2b, H3a, and H4a in the proposed model. H3b and H4b were also supported by strong predictions from media attention (β = 0.21, p = .001) and interpersonal discussion (β = 0.19, p = .003) to subjective norm.

Lastly, several additional significant paths were suggested in the revised extended TPB model. Strong and significant predictive effects from attitude of an individual toward HPV vaccination (β = 0.40, p < .001) and subjective norm (β = 0.46, p < .001) were also observed on the PBC of an individual, explaining 57% (p < .001) of the variance in this particular construct. Subjective norm was also found to be significantly predicted by the attitude of an individual toward HPV vaccination (β = 0.41, p < .001). Therefore, 41% (p < .001) of the variance in subjective norm was explained by media attention, interpersonal discussion, and attitude toward HPV vaccination.

Discussion

In line with previous studies which applied TPB to predict various health behaviors,5 our results suggested that Chinese women consumers were more likely to have greater intention to uptake HPV vaccination if they hold a positive attitude toward it, perceive beliefs where social agents approve of such behaviors, and feel that HPV vaccination is within their control. Additionally, this study found that TPB related factors explained more than 50% of the variance in HPV vaccination uptake intention, showing that the original TPB model is still robust in predicting behavioral intention in the context of HPV vaccination research in China. More importantly, the revised model revealed significant paths among attitude toward HPV, PBC, and subjective norm. Since the relationships between these two variables are rarely explored in previous TPB studies, the findings opened the discussion on how attitudes and subjective norm affected young Chinese women’s PBC in the HPV vaccination uptake. It has a theoretical contribution to the health behavioral domain and inspired future studies to confirm whether this significant relationship is specific to the Chinese culture or social contexts of HPV.

Consistent with past research,18 this study found if young Chinese women hold greater risk perception of developing cervical cancer, they were more likely to uptake HPV vaccination. Moreover, this study found that risk perception was associated with their attitude toward HPV vaccination as well. If young women perceived risk of developing cervical cancer, they were more likely to hold a positive attitude toward HPV vaccination. This result is in line with past studies that have shown that public risk perception influenced their health-related attitudes.31,32 Therefore, if health authorities attempt to increase the HPV vaccination uptake rate and form positive attitudes toward it among eligible vaccine recipients, it is important to let the participants understand their risks of developing cervical cancer.

Consistent with previous studies,15,32 media attention was found to positively relate to people’s attitude toward HPV vaccination. This result is in line with the information-processing model,35 which argues that the more attentive individuals were to messages generated by media outlets, the more the likelihood that their attitude will be reinforced or changed.36,37 After HPV vaccination was officially licensed for use in mainland China, HPV vaccination-related information provided by the media increased sharply.33 Because of the increased information and knowledge about HPV vaccination from various media platforms, it is unsurprising that individuals tend to have a more favorable attitude toward it. Moreover, consistent with the IPMI model, this research found that media attention was positively associated with subjective norm as well. This suggests that the more attention young Chinese women paid to HPV vaccination-related news, the stronger the subjective norm they perceived toward HPV vaccination uptake behavior, as they assumed that these messages would reach them and affect them.

Lastly, this research found that interpersonal discussion was positively associated with their attitudes toward HPV vaccination. This result is in line with previous studies indicating that interpersonal discussion can change individuals’ attitudes toward health-related behaviors.17,39 Moreover, in line with past research,40 discussion on HPV vaccination with nearby social agents such as family members, friends, or colleagues was positively associated with perceived subjective norm as well. Through discussing HPV vaccination with others, individuals could perceive that their friends and families were willing to uptake HPV vaccination or would expect them to uptake HPV vaccination, which, in turn, predicted their intention to uptake HPV vaccination.

The study has some limitations that are worth mentioning. Firstly, the participants were mainly young university students. Their profile may not represent the working adults in different occupations. Future studies should be expanded to female participants within diverse professional backgrounds. Secondly, a sample size of 417 is still considered to be small when analyzing a complex model with 7 latent variables such as in this study. In order to obtain more stable estimates, the major conclusions need to be examined in a large-scale study. Thirdly, the data was only collected from female participants who heard of the HPV vaccine, due to the methodological consideration of survey administration. We cannot be sure if the factors identified in the current study could apply to those who had no knowledge of the HPV vaccine. Thus, conclusions about the correlates of vaccination intention should be taken with some precaution.

Despite the limitations, this study has several theoretical and practical implications to the relevant domain. First, this study is one of the few health communication studies that explored the factors influencing public intention to uptake HPV vaccination in China. The results offer important knowledge to understand unvaccinated eligible vaccine recipients and to identify any differences between those likely and unlikely to get vaccinated, which may suggest barriers of some types. Secondly, the findings contribute to existing health communication literature by indicating how original TPB model cooperated with communication factors that are related to the intention to uptake HPV vaccination in China. The significant factors identified from this study can be applied to explore other health issues such as the public’s intention to take preventive measures toward various cancers, in other geographical contexts. Finally, the study can inspire government and health professionals in developing healthcare policies to improve HPV vaccine uptake, as well as provide lessons-learned for future vaccine programs to be considered in the early months of availability.

Biographies

Li Li (PhD, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) is an Associate Professor in the School of Journalism at Yunnan University, P. R. China. Her research interest spans the areas of uses and impacts of new media technology and health communication.

Jinhui Li (PhD, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) is a Professor in School of Journalism and Communication, Jinan University, P. R. China. His research interests focus on information technology and health communication.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Yunnan University Research Grant [number C176220100019]

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Chen L, Song Y, Ruan G, Zhang Q, Lin F, Zhang J, Wu T, An J, Dong B, Sun P, et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding HPV and vaccination among chinese women aged 20 to 35 years in fujian province: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Control. 2018;25(1):1073274818775356. doi: 10.1177/1073274818775356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICO Information Centre . (2018). Human papillomavirus and related cancers in China, fact sheet. [accessed 2019 May 25]. http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/CHN_FS.pdf

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . (2017). Genital HPV infection-CDC fact sheet. [accessed 2019 May 24]. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/HPVFS-July-2017.pdf

- 4.World Health Organization . (2010). Human papillomavirus (HPV). [accessed 2019 May 25]. http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/hpv/en/

- 5.Zhu F, Chen W, Hu Y, Hong Y, Li J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Pan Q, Zhao F, Yu J, et al. Efficacy, immunogenicity and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in healthy Chinese women aged 18-25 years: results from a randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2612–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He J, He L.. Knowledge of HPV and acceptability of HPV vaccine among women in western China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Wu X. Factors affecting HPV vaccination uptaking intention among migrant women in Dongwan (translated). J Prev Med Info. 2018;34:148–52. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR. Does the theory of planned behavior mediate the effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors? Results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2005;24(2):189–97. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katapodi MC, Dodd MJ, Lee KA, Facione NC. Underestimation of breast cancer risk: influence on screening behavior. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(3):306–14. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.306-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griva F, Anagnostopoulos F, Madoglou S. Mammography screening and the theory of planned behavior: suggestions toward an extended model of prediction. Women Health. 2010;49(8):662–81. doi: 10.1080/03630240903496010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Li L, Ma J, Wei L, Niyazi M, Li C, Xu A, Wang J, Liang H, Belinson J, et al. Knowledge and attitudes about human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccines among women living in metropolitan and rural regions of China. Vaccine. 2009;27(8):1210–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen N, Shen F. Communicating to young Chinese about human papillomavirus vaccination: examining the impact of message framing and temporal distance. Asian J Commun. 2016;26(4):387–404. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2016.1162821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine. 2012;30(16):2676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wigle J, Coast E, Watson-Jones D. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine implementation in low and middle-income countries (LMICs): health system experiences and prospects. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3811–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen MF. Modeling an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict intention to take precautions to avoid consuming food with additives. Food Qual Prefer. 2017;58:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook RL, Zhang JY, Mullins J, Kauf T, Brumback B, Steingraber H, Mallison C. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in medicaid. J Adolescent Health. 2010;47(6):596–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee EW, Ho SS, Chow JK, Wu YY, Yang Z. Communication and knowledge as motivators: understanding Singaporean women’s perceived risks of breast cancer and intentions to engage in preventive measures. J Risk Res. 2013;16(7):879–902. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2012.761264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin TT, Li L, Bautista JR. Examining how communication and knowledge relate to Singaporean youths’ perceived risk of haze and intentions to take preventive behaviors. Health Commun. 2017;32(6):749–58. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1172288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. (Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading (MA): Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker RK, White KM. Predicting adolescents’ use of social networking sites from an extended theory of planned behaviour perspective. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(6):1591–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanovitzky I, Stewart LP, Lederman LC. Social distance, perceived drinking by peers, and alcohol use by college students. Health Commun. 2006;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1901_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Yu J, Zhang J, Li X, McGue M. Investigating genetic and environmental contributions to adolescent externalizing behavior in a collectivistic culture: a multi-informant twin study. Psychol Med. 2015;45(9):1989–97. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earley PC. Social loafing and collectivism: A comparison of the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Adm Sci Q. 1989;565–81. doi: 10.2307/2393567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soh S, Leong FT. Validity of vertical and horizontal individualism and collectivism in Singapore: relationships with values and interests. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2002;33(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033001001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heirman W, Walrave M, Ponnet K. Predicting adolescents’ disclosure of personal information in exchange for commercial incentives: an application of an extended theory of planned behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(2):81–87. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta‐analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2011;40(4):471–99. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalewski MR, Henson KD, Longshore D. Rethinking perceived risk and health behavior: a critical review of HIV prevention research. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):313–25. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(3):411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2004;38(4):388–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brossard D, Scheufele DA, Kim E, Lewenstein BV. Religiosity as a perceptual filter: examining processes of opinion formation about nanotechnology. Public Underst Sci. 2009;18(5):546–58. doi: 10.1177/0963662507087304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho SS, Scheufele DA, Corley EA. Value predispositions, mass media, and attitudes toward nanotechnology: the interplay of public and experts. Sci Commun. 2011;33(2):167–200. doi: 10.1177/1075547010380386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, Nowak G, Jin Y, Cacciatore M. Inadequate and incomplete: chinese newspapers’ coverage of the first licensed human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in china. J Health Commun. 2018;23(6):581–90. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1493060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slater MD, Goodall CE, Hayes AF. Self-reported news attention does assess differential processing of media content: an experiment on risk perceptions utilizing a random sample of US local crime and accident news. J Commun. 2009;59(1):117–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01407.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGuire WJ. Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. In: Rice RE, Atkin CK, editors. Public Communication Campaigns. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2001. p. 22–48. [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeFleur M, Ball-Rokeach S. Media system dependency theory. In: DeFleur M, Ball-Rokeach S, editors. Theories of Mass Communication. New York (NY): Longman; 1989. p. 292–327. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin CA, Lagoe C. Effects of news media and interpersonal interactions on H1N1 risk perception and vaccination intent. Comm Res Rep. 2013;30(2):127–36. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2012.762907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunther AC, Storey JD. The influence of presumed influence. J Commun. 2003;53(2):199–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husaini BA, Sherkat DE, Bragg R, Levine R, Emerson JS, Mentes CM, Cain VA. Predictors of breast cancer screening in a panel study of African American women. Women Health. 2001;34(3):35–51. doi: 10.1300/J013v34n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank LB, Chatterjee JS, Chaudhuri ST, Lapsansky C, Bhanot A, Murphy ST. Conversation and compliance: role of interpersonal discussion and social norms in public communication campaigns. J Health Commun. 2012;17(9):1050–67. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.665426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho SS, Liao Y, Rosenthal S. Applying the theory of planned behavior and media dependency theory: predictors of public pro-environmental behavioral intentions in Singapore. Environ Commun. 2015;9(1):77–99. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.932819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide (Version 6th). Los Angeles (CA): Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equation manual. Encino (CA): Multivariate Software; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerbing DW, Anderson JC. Monte Carlo Evaluations of Goodness of Fit Indices for Structural Equation Models. Sociol Methods Res. 1992;21(2):132–60. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol Res. 2003;8:23–74. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1990;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(4):424–53. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hair JF, Tatham RL, Anderson RE, Black W. Multivariate data analysis. 5th. London, UK: Prentice-Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 3rd. New York, US: Tata McGraw-Hill Education; 2010. [Google Scholar]