Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a life-threatening condition that causes physical and psychological disorders and decreases patients’ quality of life (QoL). Performing proper educational self-care program may lead to higher QoL in these patients. This study was performed to investigate the effectiveness of a self-care educational program on QoL in patients with CAD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This semi-experimental study was performed on 60 patients with CAD referred to the cardiac rehabilitation (CR) center of Vali Asr hospital in Qom, Iran, in 2018–2019. Patients were divided into control and intervention groups by randomized sampling. The self-care educational program was provided through lectures and booklet. Data collection was done using the “demographic and clinical data questionnaire,” and “Seattle Angina questionnaire.” Questionnaires were completed in both groups, before and at least 1 month after education. Analysis of the obtained data was performed using SPSS software (version 25), central indexes, Mann–Whitney test, and Wilcoxon test.

RESULTS:

No significant differences were observed between the two groups for demographics characteristics and quality of life before the intervention. Before the self-care program, the mean score of the QoL in the intervention and control group were 56.14 ± 9.75 and 58.46 ± 11.71, respectively. After that, the mean score of the QoL in the intervention and control group were 59.25 ± 10.56 and 59.7 ± 13.33, respectively. The statistical analysis showed significant differences in the mean scores of QoL in the intervention group before and after the intervention (P < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences were seen in the control group before and after the study (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS:

The self-care educational program improved the QoL in patients with CAD. Therefore, lectures and educational booklets should be considered by CR nurses.

Keywords: Cardiac rehabilitation, coronary artery disease, quality of life, self-care

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the major global concerns.[1] According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimation, CVD can cause more than 23 million death in 2030 around the world.[2] Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a common CVD that causes high morbidity and mortality in industrialized countries.[3,4] In the USA, approximately one-third of all deaths are due to CAD.[5] Furthermore, it can be a serious threat in less developed countries. For instance, in Iran, CVD is responsible for half of all death annually, and it will increase sharply as a result of the aging population, industrialization, and unhealthy lifestyle.[6,7] The current CAD treatment is medical or surgical, such as the infarcted artery's reperfusion strategy with the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PTCA) and fibrinolytic therapy, which can improve myocardial recovery and reduce mortality. However, it remains a leading cause of death and disability.[8]

CAD and other chronic conditions can cause not only physical and psychological disorders, but also they can impair patients’ quality of life (QoL). Therefore, CAD's current management should focus on reducing mortality and morbidity rate and improving QoL.[9,10,11] QoL has been defined by WHO (1997) as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”[12]

Some studies illustrate the high prevalence of CAD and its risk factors such as dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, metabolic syndrome, obesity, addiction, and low levels of physical activity in the Iranian population.[13,14] Nurses have a key role in improving patients’ QoL by increasing their awareness about disease risk factors through self-care educational programs.[15] Patient education is one of the essential nurses’ roles that could positively change patients’ lives by reducing risky behaviors, stress, and medical costs, increasing physical activity, and improving their QoL with better clinical outcomes.[16,17]

Usually, self-care among patients with CVD is neglected, and most of them suffer from inadequate self-confidence in doing self-care.[18] Self-care is an essential aspect of risk factor management, and it leads to higher QoL in patients with CVD.[19] Self-care is defined as the management and prevention of chronic disease and health maintenance.[20] Although adherence to self-care programs in CVD patients leads to a higher QoL, lower mortality, morbidity, and medical costs,[21] self-care in these patients is not desirable and should be improved.[22]

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is a secondary prevention program as a Class I recommendation after cardiac events.[23] CR programs can significantly reduce mortality and morbidity rates in patients with CAD and improve their QoL, boost their functional capacity and psychological and social well-being.[24,25] CR programs offer tailored exercise, psychological support, nutritional consultation, and risk factor modification programs for cardiovascular sufferers.[26,27]

Given the increasing incidence of CAD, unhealthy lifestyle, and lack of a specific self-care educational program after cardiac events, the researchers were motivated to investigate and determine the effectiveness of self-care program on QoL in patients with CAD undergoing CR. This study was performed to investigate the effectiveness of a self-care educational program on QoL in patients with CAD.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

A semi-experimental study was conducted on 60 patients with CAD referred to the CR center of Vali Asr Hospital in Qom during 2018–2019. The inclusion criteria were having a definitive diagnosis of CAD by angiography findings, no previous formal education in self-care for heart disease patients, having Iranian nationality, interest in learning and participating in the study, not having any known mental problems, having a stable physical condition, being able to answer researchers’ questions and speak Persian. Patients who wanted to withdraw from the study, were re-hospitalized, faced death after discharge, and before completing the study questionnaires, were excluded.

Study participants and sampling

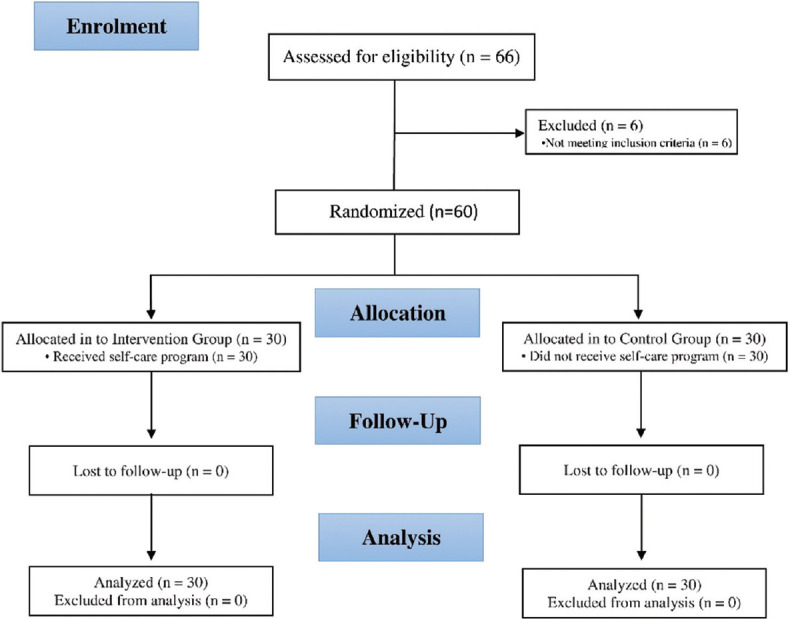

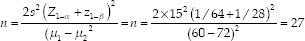

The sample size was calculated with the hypothesis test formula and using the results of a local study (μ1= 60, μ2= 72, δ = 15, α = 0.05, β = 0.1).According to the formula, the sample size in each group was 27 members, but for more confidence, a randomized sample of 30 patients in each group with CAD was drawn.[3] At first, 66 patients with CAD were assessed for eligibility. Among those, six did not have the inclusion criteria. Therefore, 60 patients were randomly allocated into two groups; 30 patients of even days were assigned in the control group, and 30 patients of the odd days were assigned to be the intervention group [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted based on the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the research deputy and the research ethics committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.MUQ.REC.1395.48). We informed patients about the aim and the flow of the study and asked them to sign a written consent form before attending the research. The researchers also prepared an educational booklet for the control group at the end of the study.

Data collection tool and technique

After receiving the necessary permissions and approvals, we referred to the study setting and identified eligible subjects. The researcher randomly selected patients and allocated to two equal groups of intervention and control groups. The study continued until the sample size reached the desired level. The aim and the methods of the study were explained to them, and informed consent was obtained. Then, study subjects were invited to complete the demographic questionnaire and Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ). During the 1st week of the CR beginning, the researcher presented an education program through power point-enhanced lecture with oral explanation and video presentation and gave them an educational booklet in the intervention group within 60 min. Discussions were about heart disease, its risk factor, the role of proper diet, regular exercise, the use of cardiac drugs and their complications, stress management smoking cessation.

After the end of the rehabilitation period, the questionnaires were completed again by both groups. Two questionnaires are completed at least 1 month apart. For participants who were unable to read or write, questionnaires were filled using the interview technique. Patients’ names were coded for being kept secret, and patients could leave this study if they do not want to continue cooperation.

Study data were collected using a clinical and demographic questionnaire (on participants’ age, gender, education, employment, use of cardiac medications, and history of other underlying diseases) and the SAQ. The SAQ is a 19-item and 5 subscale standardized questionnaire for evaluating the QoL in heart disease patients. 5 subscale is physical limitation (item 1–9), angina stability (item 10), angina frequency (item 11–12), treatment satisfaction (item 13–16), and disease perception (item 17–19). Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale on which 0 is equal to “severity limitation,” and four is equal to “no limitation.” In negative items are scored reversely. The total score of the SAQ ranges from 0 to 100. Scores higher than 51 show a higher QoL. Taheri-Kharameh et al. evaluated the reliability and validity of the Persian SAQ. They reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.85 for the questionnaire.[28] Besides, Cronbach's alpha coefficient in this research was obtained at 0.87.

The data have been analyzed using the SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 13. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. The mean score and standard deviation were calculated. The central indexes assessed clinical and demographic variables (such as gender, education, history of an underlying disease, and use of cardiac medications), and mean of quality of life score. Due to the data normality was used Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Mann–Whitney test was employed for comparing the QoL in patients before and after receiving the self-care educational program between the control and intervention groups. We also performed the Wilcoxon Test for comparing the QoL in patients before and after receiving the self-care educational program in the control and intervention groups. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

In total, 66 subjects had been admitted in the CR center, from whom six did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 60 participants (30 subjects in the control group and 30 subjects in the intervention group) entered and completed the study. Men comprised more than 65% of the participants in each group. The average age of intervention and control participants were 58.1 ± 5.8 and 57.66 ± 4.5, respectively. Most of the participants had a low level of education in both groups, and 50% of subjects were employed. More than 50% of them did not have underlying diseases and drug consumption. No significant statistical difference was observed between groups about demographic characteristics [Table 1].

Table 1.

Study participant’s demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Groups | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 20 (66.66) | 20 (66.66) | 0.608 |

| Female | 10 (33.33) | 10 (33.33) | |

| Education | |||

| Illiterate | 19 (63.33) | 20 (66.66) | 0.5 |

| Literate | 11 (36.66) | 10 (33.33) | |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed | 15 (50) | 14 (46.66) | 0.5 |

| Employed | 15 (50) | 16 (53.33) | |

| History of underlying disease | |||

| Yes | 13 (43.33) | 10 (33.33) | 0.356 |

| No | 17 (56.66) | 20 (66.66) | |

| Use of cardiac medications | |||

| Yes | 11 (36.66) | 8 (26.66) | 0.356 |

| No | 19 (63.33) | 22 (73.33) | |

Before the self-care program, the mean score of the QoL in the intervention and control group were 56.14 ± 9.75 and 58.46 ± 11.71, respectively. After that, the mean score of the QoL in the intervention and control group were 59.25 ± 10.56 and 59.7 ± 13.33, respectively. According to the Mann–Whitney test, there was no difference in the QoL between the two groups before the program. After intervention, the QoL in the intervention group was better than the control group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of quality of life before and after self-care program in two groups

| Variable | Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Groups (mean±SD), median (range) | Z | P | ||

|

| ||||

| Intervention | Control | |||

| Quality of life | ||||

| Before self-care program | 56.14±9.75 | 58.46±11.71 | −0.696 | 0.487 |

| After self-care program | 59.25±10.56 | 59.7±13.33 | −0.568 | 0.049 |

SD=Standard deviation

According to the Wilcoxon test, QoL, before and after the self-care program, in the intervention group had a significant difference. However, there was no significant difference in the control group before and after the self-care program [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of quality of life before and after self-care program in the intervention and control groups

| Seattle Angina Questionnaire (Wilcoxon test) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Statistic variables | Groups | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Intervention | Control | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Mean±SD | IQR | Range | Z | P | Mean±SD | IQR | Range | Z | P | |

| Physical restrictive | ||||||||||

| Before | 21.26±5.72 | 11 | 18 | −1.348 | 0.178 | 21.78±6.89 | 12 | 24 | −0.157 | 0.875 |

| After | 22±7.51 | 9 | 24 | 22.83±7.76 | 13 | 26 | ||||

| Stability | ||||||||||

| Before | 3.8±0.92 | 1 | 3 | 0.108 | 0.914 | 4±1.05 | 2 | 3 | −0.261 | 0.794 |

| After | 3.8±0.76 | 1 | 3 | 4±1.05 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Angina frequency | ||||||||||

| Before | 9.46±1.61 | 3 | 5 | 0.000 | 1 | 9.57±1.47 | 2 | 5 | −0.108 | 0.914 |

| After | 9.35±1.57 | 2 | 5 | 9.73±1.55 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Satisfaction of treatment | ||||||||||

| Before | 14.06±3.55 | 4 | 13 | −0.743 | 0.458 | 15.07±2.35 | 4 | 8 | 0.079 | 0.937 |

| After | 13.93±3.27 | 2 | 13 | 19.46±15.04 | 3.45 | 57 | ||||

| Perception of disease | ||||||||||

| Before | 8.57±2.23 | 2 | 9 | −2.585 | 0.1 | 8.64±2.89 | 1 | 12 | −0.974 | 0.33 |

| After | 9±2.07 | 2 | 9 | 9.06±3.37 | 1 | 13 | ||||

| Total quality of life | ||||||||||

| Before | 56.14±9.75 | 16 | 31 | −2.852 | 0.004 | 58.46±11.71 | 12 | 46 | −0.153 | 0.878 |

| After | 59.25±10.56 | 18 | 30 | 59.7±13.33 | 6 | 51 | ||||

SD=Standard deviation, IQR=Interquartile range

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of self-care program on QoL in patients with CAD undergoing CR. The obtained results showed that using such a self-care program would improve the QoL of these patients.

These findings are consistent with the results Nekouei et al.,[29] Vahedian-Azimi et al.,[30] Ebrahimi et al.,[31] and Moattari et al.[32] Those indicated that a self-care program could improve the QoL of the patients. It should be noted that the topics mentioned in the tutorial were cognitive-behavioral education, family-centered education, peer support education, and self-management program in all of the following studies.

In a study, the effect of two different methods (self-directed vs. support group learning) has been compared on the QoL and self-care behaviors in postmenopausal women. This study showed the effect of group education was far more than self-directed learning because people prefer to learn from peer groups.[33] Therefore, the researchers recommend that future studies compare the effectiveness of peer-group with individualized education in CVD patients.

In another study, Ahn et al. indicated that self-care health behaviors play an important role in QoL in adults with CAD. Nurses should motivate them to perform self-care health behaviors strategies to improve QoL.[34] Furthermore, González-Chica et al. reported that inadequate health literacy could lead to low physical activity, and health education program strategies improve QoL in patients with ischemic heart disease.[35] Besides, higher health literacy can be achieved by self-care educational programs in cardiovascular patients leading to lower hospital readmission in the long term.[36]

However, our findings are inconsistent with Dickson et al. study, which reported that self-care educational programs in low literacy heart failure patients did not affect their QoL.[37] Moreover, Asadi et al. investigated the relationship between self-care and QoL in chronic heart failure patients. They reported that there was not a correlation between self-care and QoL in those patients. They also noted that single, male, higher educated, and urbanist patients had a higher QoL.[38] The inconsistencies between different studies may be associated with different study designs, small sample size, differences in educational methods, and duration of their study intervention.

In this study, researchers used various educational methods through a PowerPoint lecture, a video presentation, and an educational booklet. Uhlig et al. reported that patients with chronic disease need different approaches to enhance their self-management behavior.[39] As new education tools such as multimedia find it difficult to cover all aspects of self-care behaviors, health-care providers should not ignore traditional methods such as booklets. Therefore, it is suggested that nurses can combine different types of education methods and enhance self-care abilities in patients.

Berndt et al. have also reported that the effectiveness of patients’ education with face-to-face and lecture-delivered methods may have the same effect as indirect telephone follow-up in coronary heart disease patients.[40] However, Strömberg et al. have studied the impact of computer-based education for patients with chronic heart failure and reported that a direct patient education program through lectures was more effective than indirect education using a computer-based method.[41]

Furthermore, Rahmani et al. reported that teach-back education methods that offer face-to-face education about the signs and symptoms of heart failure, diet, medication, and exercise can positively affect heart failure patients’ QoL and health literacy as routine discharge educations.[42]

As educational booklets have their benefits such as easy to use, cheap, and referable for the patients and their families at any time and also face to face presentation may have more effects on their knowledge about performing self-care program, researchers used both direct and indirect educational programs through PowerPoint presentations and an educational booklet. Specialists often neglect patients’ education. CR nurses can play a vital role in educating valuable self-care programs about CAD risk factors, the role of nutrition, exercise, drug consumption and their complications, stress management, and smoking cessation in patients with heart disease. This study indicated that performing an educational program based on self-care theory in patients with CAD can improve their QoL.

Limitation and suggestion

The limitations of this study were the accuracy of research units at the time of answering questions regarding their psychological state. The questionnaires were completed in a calm and convenient environment to overcome this limitation. The second limitation of this study was the difference in cultural beliefs and physiological states of patients. Educational pamphlets and videos were provided to study at home to overcome this limitation.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that the self-care program as a video and PowerPoint presentation and educational booklet for cardiac patients could enhance their QoL. Considering the importance of self-care knowledge in patients with cardiac disease, nurses need to enhance their educational role, provide the best solution to solve patients’ problems, and improve their QoL by performing a proper self-care educational program.

Financial support and sponsorship

Qom University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 95682) funded this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to all study participants. We would also like to express our special gratitude to Qom University of Medical Sciences and Vali Asr Heart Center to permit study implementation.

References

- 1.Anand SS, Yusuf S. Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2011;377:529–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62346-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammad AM, Jehangeer HI, Shaikhow SK. Prevalence and risk factors of premature coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography in Kurdistan, Iraq. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:155. doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchis-Gomar F, Perez-Quilis C, Leischik R, Lucia A. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:256. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarrafzadegan N, Mohammmadifard N. Cardiovascular disease in Iran in the last 40 years: Prevalence, mortality, morbidity, challenges and strategies for cardiovascular prevention. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:204–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joseph P, Leong D, McKee M, Anand SS, Schwalm JD, Teo K, et al. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, Part 1: The epidemiology and risk factors. Circ Res. 2017;121:677–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.308903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maleki M, Alizadehasl A, Haghjoo M. Practical Cardiology. 19. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; pp. 311–28. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong E. Health-related quality of life and health condition of community-dwelling populations with cancer, stroke, and cardiovascular disease. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:2521–4. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell DJ. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: New guidelines, technologies and therapies. Med J Aust. 2014;200:146. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludt S, Wensing M, Szecsenyi J, van Lieshout J, Rochon J, Freund T, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients at risk for cardiovascular disease in European primary care. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization WH. Measuring Quality of Life: The World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments (the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF). Apps.who.int. WHOQOL-Measuring Quality of Life. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebrahimi M, Kazemi-Bajestani SM, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Ferns GA. Coronary artery disease and its risk factors status in Iran: A review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13:610–23. doi: 10.5812/kowsar.20741804.2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maleki A, Ghanavati R, Montazeri M, Forughi S, Nabatchi B. Prevalence of coronary artery disease and the associated risk factors in the adult population of Borujerd City, Iran. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2019;14:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho E, Sloane DM, Kim EY, Kim S, Choi M, Yoo IY, et al. Effects of nurse staffing, work environments, and education on patient mortality: An observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahsavari H, Matory P, Zare Z, Taleghani F, Kaji MA. Effect of self-care education on the quality of life in patients with breast cancer. J Educ Health Promot. 2015;4:70. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.171782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salem P, Sandler I, Wolchik S. Taking stock of parent education in the family courts: Envisioning a public health model. Fam Court Rev. 2013;51:131–48. doi: 10.1111/fcre.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evangelista LS, Shinnick MA. What do we know about adherence and self-care? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:250–7. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317428.98844.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CS, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Riegel B. Event-free survival in adults with heart failure who engage in self-care management. Heart Lung. 2011;40:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Organization WH. Health Education in Self-Care: Possibilities and Limitations. Apps.who.int. World Health Organization; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riegel B, Moser DK, Buck HG, Dickson VV, Dunbar SB, Lee CS, et al. Self-care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006997. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaarsma T, Strömberg A, Ben Gal T, Cameron J, Driscoll A, Duengen HD, et al. Comparison of self-care behaviors of heart failure patients in 15 countries worldwide. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:114–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bush M, Kucharska-Newton A, Simpson RJ, Jr, Fang G, Stürmer T, Brookhart MA. Effect of initiating cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction on subsequent hospitalization in older adults. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2020;40:87–93. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francis T, Kabboul N, Rac V, Mitsakakis N, Pechlivanoglou P, Bielecki J, et al. The effect of cardiac rehabilitation on health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:352–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavie CJ, Menezes AR, De Schutter A, Milani RV, Blumenthal JA. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training on psychological risk factors and subsequent prognosis in patients with cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:S365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.07.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taheri-Kharameh Z, Heravi-Karimooi M, Rejeh N, Hajizadeh E, Vaismoradi M, Snelgrove S, et al. Translation and psychometric testing of the Farsi version of the Seattle angina questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:234. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nekouei ZK, Yousefy A, Manshaee G. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and quality of life: An experience among cardiac patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:2. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.94410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vahedian-Azimi A, Alhani F, Goharimogaddam K, Madani S, Naderi A, Hajiesmaeili M. Effect of family-centered empowerment model on the quality of life in patients with myocardial infarction: A clinical trial study. J Nurs Educ. 2015;4:8–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebrahimi H, Abbasi A, Bagheri H, Basirinezhad MH, Shakeri S, Mohammadpourhodki R. The role of peer support education model on the quality of life and self-care behaviors of patients with myocardial infarction. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moattari M, Adib F, Kojuri J, Tabatabaee SH. Angina self-management plan and quality of life, anxiety and depression in post coronary angioplasty patients. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e16981. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.16981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dastgerdi FA, Zandiyeh Z, Kohan S. Comparing the effect of two health education methods, self-directed and support group learning on the quality of life and self-care in Iranian postmenopausal woman. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:62. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_484_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn S, Song R, Choi SW. Effects of self-care health behaviors on quality of life mediated by cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with coronary artery disease: A structural equation modeling approach. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2016;10:158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.González-Chica DA, Mnisi Z, Avery J, Duszynski K, Doust J, Tideman P, et al. Effect of health literacy on quality of life amongst patients with Ischaemic Heart Disease in Australian General Practice. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lima MA, Duque AP, Rodrigues Junior LF, Lima VC, Trotte LA, Guimaraes TC. Health literacy and quality of life in hospitalized heart failure patients: A cross-sectional study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;10:490–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickson VV, Chyun D, Caridi C, Gregory JK, Katz S. Low literacy self-care management patient education for a multi-lingual heart failure population: Results of a pilot study. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;29:122–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asadi P, Ahmadi S, Abdi A, Shareef OH, Mohamadyari T, Miri J. Relationship between self-care behaviors and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02493. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uhlig K, Patel K, Ip S, Kitsios GD, Balk EM. Self-measured blood pressure monitoring in the management of hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:185–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berndt N, Bolman C, Froelicher ES, Mudde A, Candel M, de Vries H, et al. Effectiveness of a telephone delivered and a face-to-face delivered counseling intervention for smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: A 6-month follow-up. J Behav Med. 2014;37:709–24. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9522-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strömberg A, Dahlström U, Fridlund B. Computer-based education for patients with chronic heart failure. A randomised, controlled, multicentre trial of the effects on knowledge, compliance and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahmani A, Vahedian-Azimi A, Sirati-Nir M, Norouzadeh R, Rozdar H, Sahebkar A. The effect of the teach-back method on knowledge, performance, readmission, and quality of life in heart failure patients. Cardiol Res Pract. 2020;2020:8897881. doi: 10.1155/2020/8897881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]