Abstract

The medicinal plants may serve as natural alternatives to synthetic antidiabetic medications such as dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors, which are commonly prescribed in clinical practise. The medicinal plants: Commiphora mukul and Phyllanthus emblica have considerable DPP-IV inhibitory efficacy, according to our findings. The present study is an extension of the previous study conducted in our laboratory and was designed to confirm the antidiabetic effects of C. mukul and P. emblica in the streptozotocin diabetes model and elucidate the active principles responsible for DPP-IV inhibition. C. mukul (Guggul) and P. emblica (Amla) have the ability to inhibit DPP-IV and have anti-diabetic properties in a Type 2 diabetes mellitus experimental model. The binding sites and affinity of the active principles of C. mukul (Gluggusterone E, Gluggusterone Z) and P. emblica (Pzrogallol, beta-glucogallin, and gallic acid) responsible for DPP-IV enzyme inhibition were identified using in silico studies and compared to Vildagliptin, a synthetic DPP-IV inhibitor. The Vildagliptin and therapy groups had significantly lower glycated hemoglobin and DPP-IV levels. The anti-diabetic effect of C. mukul and P. emblica is due to their DPP-IV inhibitory action. The DPP-IV inhibitory action of Gluggusterone E, Gluggusterone Z, and beta-Glucogallin was found to be superior to Vildagliptin in docking tests.

Keywords: Commiphora mukul, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors, Phyllanthus emblica, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Vildagliptin

Introduction

Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors are unquestionably potential new antidiabetic medications used clinically.[1] Vildagliptin and sitagliptin are two such synthetic DPP-IV inhibitors currently on the market. DPP-IV inhibitors are widely used in clinical practice, although there is growing evidence of their nil side effects, such as angioedema.[2] Furthermore, DPP-IV inhibitors are costly medications that may not be economically viable because patients from lower socioeconomic groups may be Non-compliant to medication over time.[3]

In this situation, the discovery of innovative DPP-IV inhibitors derived from alternate sources that are both safe and cost-effective is critical. This study was created with this goal in mind. Medicinal plants native to India, such as morphine, atropine, and digitoxin, have been utilized therapeutically and are now the mainstay of therapy.[4] As a result, medicinal plants must be screened to identify natural DPP-IV inhibitors, which could be beneficial to developing countries such as India and South-east Asia.

The DPP-IV inhibitory action of Commiphora mukul and Phyllanthus emblica was previously reported from our laboratory.[5] The experimental model of Type 2 diabetes mellitus was used to assess if their ability to inhibit DPP-IV translates into significant antidiabetic benefits. Docking studies were conducted to learn more about the active components in C. mukul (Gluggusterone E and Gluggusterone Z) and P. emblica (Pzrogallol, beta-glucogallin, and gallic acid) that contribute to their DPP-IV inhibiting properties. If the results are positive, they will pave the way for the active compounds in C. mukul and P. emblica as DPP-IV inhibitor alternatives to synthetic inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

Wistar rats, weighing 150–200 g, were kept under conventional laboratory conditions in the Institutional Animal Facility (CPCSEA No 303/PO/Re/S/2000/CPCSEA). The Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC/2014/2/11) authorized the study.

Test drugs

Sanat Pharmaceutical Limited, New Delhi, provided standardized hydro-alcoholic extracts of C. mukul oleo-gum-resin and P. emblica fresh fruit.

Inhibitory test for dipeptidyl peptidase-IV

The Al-masri 2009 technique was used to perform the DPP-IV inhibition experiment.[6]

Type 2 diabetes mellitus produced in the lab

Intraperitonally administered streptozotocin (45 mg/kg) caused Type II diabetes in rats.[7] For 4 weeks, Vildagliptin (10 mg/kg), C. Mukul (200 mg/kg), and P. Emblica (300 mg/kg) were given orally, and blood samples were collected for calculating glycated hemoglobin (HBA1C) and DPP-IV values.

In-silico research

The crystal structure of DPP IV was retrieved from Protein Data Bank[8] The active ingredients of C. mukul and P. emblica Gallic acid, gluggustrone E, gluggustrone Z, Pzrogallol, and beta-glucogallin were obtained from the Pubchem database, as were Sitagliptin, Vildagliptin.[9] The DPP-IV active site was determined using the PDB Sum data from 2Q79. The optimised DPP-IV enzyme and ligands were docked using Hex software 8.0.[10] Ten Poses were created for interaction investigation using Swiss pdb viewer. CASTp software was also used to predict active sites.[11] Using Webnm@software in Normal Mode, a DPP-IV inhibitor was investigated for domain mobility analysis.[11]

Statistical analysis

P < 0.05 defined the statistical significance. For post hoc analysis, ANOVA with Tukey's test was performed.

Results

Medicinal herbs with dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibiting action

When compared to P. emblica (85.957.16%), Sitaglitin (84.67% +8.21%), and Vildagliptin (90.42% +7.84%), the DPP-IV inhibition displayed by C. mukul (92.978.45%) was shown to be superior.

Biochemical values

A considerable increase in HbA1C readings in the STZ-Control group when compared to NC confirmed the induction of diabetes. When compared to STZ-Control, the treatment groups had significantly lower HBA1C and DPP-IV levels [Table 1].

Table 1.

Levels of glycated hemoglobin and dipeptidyl peptidase-IV in various experimental groups

| Variable | NC | STZ-control | VIL | C. mukul | P. emblica |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1C (%) | 6.22±1.3 | 10.4±2.3* | 8.01±1.7@ | 8.42±1.8@ | 8.65±1.8@ |

| Serum DPP-IV (microunit/ml) | 4.7±0.4 | 38.2±4.3** | 12.2±1.4@@@,# | 16.42±2.04@@@ | 17.42±2.04@@@ |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 NC versus STZ-control, @P<0.05, @@@P<0.001 STZ-control versus VIL, C. mukul, P. emblica, #P<0.05 VIL versus C. mukul, P. emblica. For post hoc analysis and comparison between research groups, ANOVA and Tukey’s test were utilised. HbA1C=Glycated hemoglobin, DPP-IV=Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV, NC=Normal control, STZ-Control=Disease (Streptozotocin) control (n=9), VIL=Vildagliptin (n=8), C. mukul=Commiphora mukul (n=7), P. emblica=Phyllanthus emblica (n=7)

In-silico research

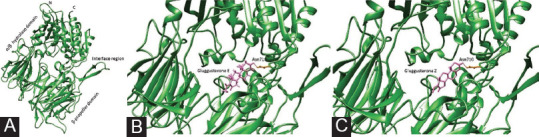

The DPP-IV enzyme has two domains: A-propeller and a hydrolase. A catalytic triad (D708, H740, S630) was produced at the-propeller and hydrolase domain interface [Figure 1A]. The lipophilic S1 pocket (formed by Tyr631, Val656, Trp659, Tyr662, Tyr666, and Val711) and the negatively charged Glu205/206 pair were the two major binding-site locations for DPP-intermolecular IV's interaction. The initial pocket predicted turned out to be the largest, with a volume of 16471Å3. meters and an area of 6086.4 Å2.

Figure 1.

(1A) The three domains of DPP-IV crystal structure: beta; hydrolase domain, interface region and β propeller region Docking results of (1B) Gluggusterone E and (1C) Gluggusterone Z (active ingredients of Commiphora mukul ) in the active site pocket of DPPIV receptor

The second largest pocket was discovered to have a volume of 1171.83 Å3 and a surface area of 574.32 Å2. For each of the six modes, the square fluctuation of the DPP-IV inhibitor's C-alpha atom was calculated.

Gluggusterone E and Gluggusterone Z prefer to bind to the DPP-IV enzyme's active site pocket. Gluggusterone E and Gluggusterone Z bind to Glu205 and Glu206 very tightly [Figure 1B and IC]. Sitaglitin and gallic acid [Figure 2A] interact with the hydrolase and propeller domain, Pzrogallol [Figure 2B], vildagliptin prefer to bind to the DPP-IV enzyme's interface area, and beta-glucogallin [Figure 2C] preferably bind to active site pocket [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Docking results of (2A) Gallic Acid 2B) Pzrogallol (2C) beta;-glucogallin (active ingredients of Phyllanthus emblica) near beta propeller domain and beta; hydrolase domain of DPPIV receptor

Table 2.

The findings of a docking study with several ligands

| Ligands | IC50 | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Amino acids residue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 0.36 µM | −182.63 | Arg382 |

| Gluggusterone E | 15 µM | −239.64 | Asn710 |

| Gluggusterone Z | 17 µM | −239.64 | Asn710 |

| Pzrogallol | 39 microM | −200.79 | Glu347, Arg382 |

| β-glucogallin | 0.8 μg/mL | −271.97 | Ala743 |

| Sitagliptin | 18 nm | −138.90 | Glu452 |

| Vildagliptin | 3 nm | −236.55 | Asp739 |

Discussion

DPP-IV is found in the liver, kidney, gut, B-cells, T-cells, and natural killer cells, among other places.[12] DPP-IV inhibitors are widely utilized in clinical practice as anti-diabetic medications due to their minimal risk of hypoglycemia and convenient once-daily dosage schedules. They appear to reduce beta cell apoptosis and increase beta cell bulk while being weight-neutral.[13] Despite their beneficial therapeutic effects, their high price and side effects are a source of worry, and their clinical usage may be limited.[14]

In order to find new sources of DPP-IV inhibitors, the potential of producing DPP-IV inhibitors from natural sources such as medicinal plants must be explored. Previous research from our lab has shown that C. mukul and P. emblica have considerable DPP-IV inhibitory properties.[5] Surprisingly, the DPP-IV inhibition induced by C. mukul was superior to the therapeutically available Sitagliptin and Vildagliptin.

In an experimental model of diabetes, C. mukul and P. emblica dramatically increased DPP-IV levels. The medicinal herbs' DPP-IV inhibitory activity also translated into considerable antidiabetic efficacy, as seen by a considerable reduction in HBA1C levels.[15]

The purpose of this study was to learn more about the active components responsible for the DPP-IV inhibitory activity of C. mukul and P. emblica. Docking experiments against DPP-IV revealed that the active compounds in C. mukul (Gluggusterone E, Gluggusterone Z) and P. emblica (Pzrogallol, beta-glucogallin, gallic acid) have considerable inhibitory activity against the enzyme. DPP-IV has a propeller and hydrolase domains in its crystal structure, as well as a catalytic triad (S630, H740, and D708) generated at the interface of the-propeller and hydrolase domains.

Gluggusterone E, Gluggusterone Z, and glucogallin bind to the DPP-IV enzyme's active site pocket. Pzrogallol and Vildagliptin bind to the interface area, whereas Sitagliptin binds to the α/β hydrolase domain of DPP-IV. Between the α/β hydrolase and the propeller domain, gallic acid binds. When compared to Sitagliptin, all of the active components in C. mukul and P. emblica demonstrated higher DPP-IV inhibitory action. Interestingly, the DPP-IV inhibition displayed by Gluggusterone E, Gluggusterone Z, and beta-Glucogallin was shown to be superior to Vildagliptin based on binding energy data.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mentlein R, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1 (7-36) amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:829–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monami M, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and pancreatitis risk: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:48–56. doi: 10.1111/dom.12176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan SY, Litscher G, Gao SH, Zhou SF, Yu ZL, Chen HQ, et al. Historical perspective of traditional indigenous medical practices: The current renaissance and conservation of herbal resources. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:525340. doi: 10.1155/2014/525340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharti SK, Sharma NK, Kumar A. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitory activity of seed extracts of Castanospermum austral and molecular docking of their alkaloids. J Herb Med. 2012;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borde M, Mohanty IR, Suman RK. Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitory activities of medicinal plants: Terminalia arjuna, Commiphora mukul, Gymnema sylvestre, Morinda citrifolia, Emblica officinalis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;3:180–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-masri IM, Mohammad MK, Tahaa MO. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) is one of the mechanisms explaining the hypoglycemic effect of berberine. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2009;24:1061–6. doi: 10.1080/14756360802610761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rakieten N, Rakieten ML, Nadkarni MV. Studies on the diabetogenic action of streptozotocin (NSC-37917) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1963;29:91–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaelin DE, Smenton AL, Eiermann GJ, He H, Leiting B, Lyons KA, et al. 4-arylcyclohexylalanine analogs as potent, selective, and orally active inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:5806–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, Chen J, Fu G, Gindulyte A, et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. CASTp: Computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopsu-Havu VK, Glenner GG. A new dipeptide naphthylamidase hydrolyzing glycyl-prolyl-beta-naphthylamide. Histochemie. 1966;7:197–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00577838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mentlein R. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26)-role in the inactivation of regulatory peptides. Regul Pept. 1999;85:9–24. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wajchenberg BL. Beta-cell failure in diabetes and preservation by clinical treatment. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:187–218. doi: 10.1210/10.1210/er.2006-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kshirsagar AD, Aggarwal AS, Harle UN, Deshpande AD. DPP IV inhibitors: Successes, failures and future prospects. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2011;5:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borde MK, Mohanty IR, Maheshwari U. DPP-4 inhibitory activity and myocardial salvaging effects of Commiphora mukul in experimental diabetes. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2019;8:575–83. [Google Scholar]