Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is spreading like wildfire with no specific recommended treatment in sight. While some risk factors such as the presence of comorbidities, old age, and ethnicity have been recognized, not a lot is known about who the virus will strike first or impact more. In this hopeless scenario, exploration of time-tested facts about viral infections, in general, seems to be a sound basis to prop further research upon. The fact that immunity and its various determinants (e.g., micronutrients, sleep, and hygiene) have a crucial role to play in the defense against invading organisms, may be a good starting point for commencing research into these as yet undisclosed territories. Herein, the excellent immunomodulatory, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory roles of Vitamin D necessitate thorough investigation, particularly in COVID-19 perspective. This article reviews mechanisms and evidence suggesting the role Vitamin D plays in people infected by the newly identified COVID-19 virus. For this review, we searched the databases of Medline, PubMed, and Embase. We studied several meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials evaluating the role of Vitamin D in influenza and other contagious viral infections. We also reviewed the circumstantial and anecdotal evidence connecting Vitamin D with COVID-19 emerging recently. Consequently, it seems logical to conclude that the immune-enhancing, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and lung-protective role of Vitamin D can be potentially lifesaving. Hence, Vitamin D deserves exhaustive exploration through rigorously designed and controlled scientific trials. Using Vitamin D as prophylaxis and/or chemotherapeutic treatment of COVID-19 infection is an approach worth considering. In this regard, mass assessment and subsequent supplementation can be tried, especially considering the mechanistic evidence in respiratory infections, low potential for toxicity, and widespread prevalence of the deficiency of Vitamin D affecting many people worldwide.

Keywords: COVID-19, prophylaxis, treatment, viral respiratory illness, Vitamin D

Introduction

This is for the third time that our planet is facing an epidemic of coronavirus (CoV) infection, having recently been classified by the WHO as a pandemic of unprecedented proportions. Previous Coronaviridae infections that led to the epidemics comprise severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which has its origins from mainland China, and the still prevalent Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV. The most recent outbreak is the SARS-CoV-2 which is still causing a lot of casualties worldwide and making a mockery of the health system, workforce, and resources.

At present, nobody knows how or when this mortal adversary is relinquishing its hold on humanity. New therapies are constantly being tried based on the past experience of handling conditions with a similar presentation like COVID-19. Numerous trials are being conducted and there is hope. Several therapeutic options like antivirals (i.e., favipiravir, lopinavir/ritonavir, oseltamivir, remdesivir),immunomodulators (i.e., chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) , convalescent plasma, anticoagulants, dexamethasone and azithromycin have been tried and a variety of vaccines are being administered.[1] Around 16 monoclonal antibodies have received emergency authorization to augment the armamentarium against the disease.[2] Recently, dexamethasone and remdesivir combination therapy has arisen as a useful combination in moderate COVID-19 disease, with reduced mortality at 30 days and decreased need for mechanical ventilation.[3] However, several promising agents have also gone out of favor, for example, plasma therapy and tocilizumab, and complete cure remains a distant dream. Amid this scenario, it seems sensible to invest in the immediate repurposing of existing drugs with known mechanisms of action and profile, especially molecules that can help in prevention.

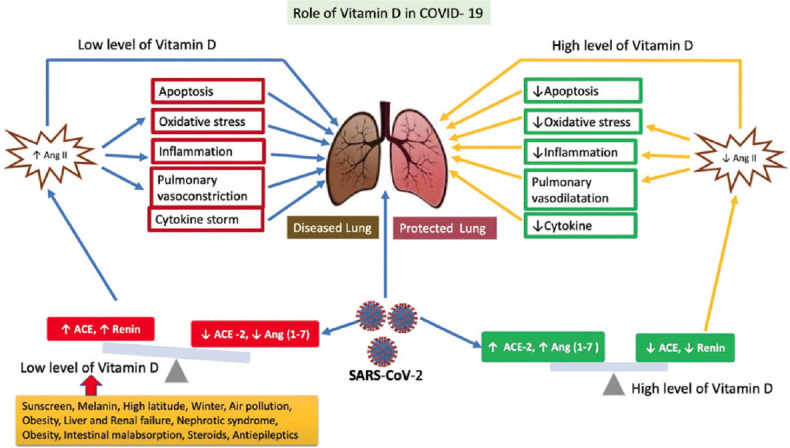

The importance of Vitamin D in maintaining bone health and metabolism of calcium and phosphate is well known. Recently, a lot of research has focused on its multiple pleiotropic effects ( immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral role) in various infectious diseases, autoimmune conditions, pulmonary fibrosis, cancer, diabetes, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and dementia, shortsightedness, neurological associated multiple sclerosis, and even psychological conditions such as depression. It is possible that these unique properties and associations of Vitamin D may very well be helpful even in this COVID infection. Accordingly, recent studies established a strong linkage between Vitamin D and COVID-19 [Figure 1]. Here, we review all circumstantial and discrete evidence pointing toward Vitamin D's role in SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 1.

Role of Vitamin D in COVID- 19. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and low levels of Vitamin D cause a downregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2-dependent angiotensin (1–7) and enhancement of angiotensin-converting enzyme E-mediated angiotensin II levels. Lung injury is consequent to increased pulmonary vasoconstriction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cytokine storm. These can well be attenuated by adequate levels of Vitamin D that restores a favorable angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 ratio

COVID-19 is a disease that damages several organs and adversely impacts almost all body processes. Symptoms range from asymptomatic disease, shortness of breath, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, etc. There are also some atypical presentations such as anosmia, dysgeusia, and chilblains.[4] The inflammatory responses against the virus are the prime reason behind some of these most debilitating symptoms. Despite extensive research being done through large-scale trials with various repurposed drugs (favipiravir, tocilizumab, etc.), only remdesivir and corticosteroids have shown any real-time benefit by a reduction in the time to recovery and suppression of hyperinflammatory syndrome, respectively, in COVID-19 patients, till now.[5] Nutraceuticals, probiotics, and diet supplementation in SARS-CoV-2 infection have therefore risen in popularity, with their proven defense against viral infections. Interestingly, Vitamin D with its pleiotropic mechanisms may curb the impact of the pandemic. This review conceptualizes and brings to one place all available information and evidence suggesting a liaison between Vitamin D and COVID-19 for more effective and informed decision-making regarding Vitamin D supplementation as prophylaxis or the possible chemotherapeutic treatment of the fast-spreading COVID-19 virus.

Immunomodulatory, Antioxidant, Lung-Protective, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antiviral Effects of Vitamin D: Potentially Useful in COVID-19 Infection

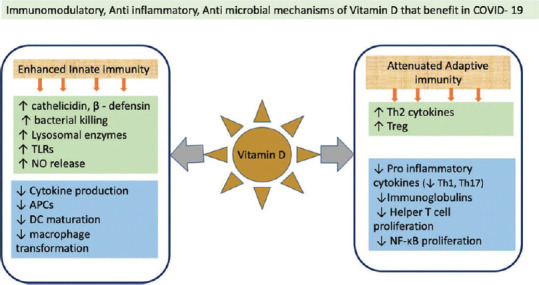

Numerous studies have been done to explain the putative mechanisms of value of Vitamin D in viral infections [Figure 2]. The protective mechanisms range from maintenance of the physical barrier's integrity via adherens, gap junctions, and tight junctions to modulation of innate (inborn) and adaptive (acquired) immunity. Numerous genes responsible for adaptive and innate immunity are controlled by Vitamin D. The Vitamin D receptor (VDR) characteristically occurs in antigen-presenting cells, B-cells, and in activated CD8+ and CD4+ cells. Their occurrence therefore proposes a likely physiological role. Vitamin D is similarly included in the regulation of T-cell immunity; decrease of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins [ILs]) (IL-8, TNF-α, etc.); and enhancement of anti-inflammatory ILs (cytokines) (IL-4, IL-10, IL-5, etc.). Additionally, B-cell apoptosis and proliferation, inhibition of plasma cells, and immunoglobulin secretion also contribute to its immunomodulatory role. Two antimicrobial peptides cathelicidin (showing apoptosis and autophagy of infected cells in HIV-1, influenza, HCV, and rhinovirus) and β-defensin are also enhanced by Vitamin D. Human cathelicidin peptide LL37 also modulates the expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs), possessing antimicrobial property against viral dsRNA. TLRs, similarly, upregulate the VDR expression which then leads to the production of cathelicidin; thus, it seems that effective antimicrobial defense is a complex and interdependent action, with Vitamin D in the center of it all. The expression of genes involved in antioxidant mechanism is, in addition, modulated by Vitamin D. Vitamin D is a membrane antioxidant. It offers a substantial role in the inhibition of iron-dependent liposomal lipid peroxidation.[6] All these mechanisms and more have consistently contributed to the clinical efficacy of Vitamin D in upper and lower respiratory tract infections (UandLRTIs) and several other viral infections.

Figure 2.

Putative mechanisms by which Vitamin D helps in COVID-19

Vitamin D has demonstrated a better prognosis and outcome in many LRTIs such as pneumonia, cytokine hyperproduction, ARDS, and several other infectious diseases as well.[7,8,9] The role of Vitamin D was also explored for influenza A H5N1-mediated lung injury and as an adjuvant drug in combination with antiretroviral agents in HIV-infected patients.[10,11] In animal studies of ARDS, Vitamin D pretreatment reduced lung permeability and subsequent compromise by modulation of the hemodynamic system-associated renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) activity and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in the lungs.[12] Certain VDR-mutated alleles have also been identified that led to an increased susceptibility to respiratory infections, and also the progression of dengue.[13,14] A similar pattern and profile of action and ensuing benefit may likely be seen in COVID-19 too.

Vitamin D after being activated in the lungs suppresses pulmonary fibrosis (bleomycin induced) and protects against interstitial pneumonia, by downregulating the pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, especially IL-1 beta. In experimental studies, lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury was relieved by Vitamin D injected into the veins of rats.[8,12] An important downside of the COVID-19 epidemic has been pulmonary fibrosis, where Vitamin D may serve as an important pathway toward recovery.

Working on the possible theory that Vitamin D holds an immune and therapeutic role in acute and chronic respiratory tract infections (ARTIs), several researchers have conducted all kinds of observational studies and randomized trials, conclusively proving a definite correlation between the risk of ARTIs and Vitamin D. A randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the possible clinical safety and efficacy of Vitamin D as an influenza A-preventive measure in schoolchildren and infants, reported a strong protective effect against RTIs in the group that received the Vitamin D supplements. A study conducted on healthy adults throughout the winter season of 2009 and 2010 reported, “Only 17% of people who maintained 25(OH)D >38 ng/mL throughout the study developed ARTIs, whereas 45% of those with 25(OH)D <38 ng/mL did. Concentrations of 38 ng/mL or more were associated with a significant (P < 0.0001) twofold reduction in risk of developing ARTIs and with a marked reduction in the percentage of days ill.”[15,16] The uncertainty surrounding the dosage providing beneficial effects against RTIs, needs to be further clarified by dose-ranging studies.

Therefore, it seems that Vitamin D might aid in COVID-19 infection in multiple ways: (a) by creation of antimicrobial peptides within the respiratory epithelium (b) as an anti-inflammatory (c) as an immunomodulatory agent (d) modulation of RAAS, favoring lung protection (e) as an antioxidant, etc.

Interleukin-6 Antagonizing Properties of Vitamin D: Potentially useful in COVID-19, Another Condition with Interleukin Excess

We now know with certainty that SARS-CoV-2 initially employs mechanisms to avoid immune system detection and attacks, which is accompanied by a cytokine storm and immune hyperreaction in some patients, with the production of a huge quantity of cytokines (ILs), precisely IL-1 and IL-6,[17] causing ARDS and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Dr. Guglielmo Gianotti, a director of surgery at Cremona Hospital located in northern Italy (possibly one of the most affected regions during the first wave of the pandemic), stated: “The only drug that we've seen that's showing the slightest bit of benefit to patients is the immunosuppressive drug tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor antagonist), which is mainly used for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.” Tocilizumab has been extensively researched through various well-controlled studies.[18,19,20] We know now that tocilizumab has questionable effectiveness in COVID-19, and its high cost in developing countries like India, is a deterrent.[21] Nevertheless, it makes sense to look for other entities that may well hold a role in attenuating the dreaded, cytokine storm, proving to be the most important reason for mortality among COVID-19 patients. In this context, research has demonstrated that low serological level of Vitamin D is related to increased levels of IL-6, and in such cases, the use of Vitamin D supplementation can reduce excess levels of IL-6.[22,23] Although there do not seem to be any published trials of tocilizumab, for influenza, there is also the possibility for a positive response in this condition. Hence, it might be hypothesized that COVID-19, a condition with excess IL-6 production, may respond to Vitamin D supplementation.

The Elderly Population and Vitamin D Deficiency – A Deadly Combination for Developing Severe Disease with COVID-19

Immunodeficiency, bronchiectasis, and increasing age have come up as key risk features for COVID-19 infection (severe form). Total serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations usually decline as a person ages which could be an central factor to consider in COVID-19 because case fatality rates (CFR) ideally escalate with age.[24,25] Apart from this, the escalation in CFR with advancing age may possibly be due to several reasons, all pointing toward a potential connection between hypovitaminosis D and COVID-19, (a) occurrence of chronic diseases spikes with an increase in age and people suffering from chronic diseases tend to have lesser Vitamin D concentrations compared to healthy persons, (b) reduced exposure to the sun when at home or in workplaces, (c) reduced ability of the skin to convert the precursor dehydrocholesterol into the active cholecalciferol, (d) a decreased appetite leading to suboptimal diet, predisposing to hypovitaminosis D, (e) impaired gastrointestinal absorption of Vitamin D, (f) use of medicines that interact with other medicines or with VDRs impairing uptake of Vitamin D, and (g) renal function impairment which is where the conversion of dehydrocholesterol into cholecalciferol occurs.[26,27,28,29] Italy, where some of the greatest mortality with COVID-19 has been seen, has a large population of old people relative to the general population, and reports state that 76% of old-age Italian women do have a form of hypovitaminosis D.

The Role of Hypovitaminosis D in Seasonal Influenza Infections and COVID-19

Most seasonal influenza infections occur during the cold season of winter.[30] Cannell et al. have theorized that the sharp rise of influenza cases in winter can be as a result of low solar UVB, and consequently, Vitamin D concentrations are lowest in winter.[31,32,33] Several ecological studies have subsequently proven that the increased risk of developing influenza in winter, could be attenuated by raising Vitamin D concentrations through supplementation.

The Role of Geographical Location-Sunlight Exposure-Vitamin D Levels in Influenza and COVID-19

Concerning COVID-19, another ecological study with the primary aim of checking for any possible connection between the typical Vitamin D levels in several nations and COVID-19-related mortality, found that serum Vitamin D levels and COVID-19 mortality were inversely correlated.[34]

It was the end of 2019 (winter) when COVID-19 appeared in the northern hemisphere at a time when Vitamin D levels are lowest. The northern hemisphere has been adversely affected by a profound COVID-19-related mortality. Ecological studies also point to the fact that higher latitudes (N + 30°N), and extremely cold winter season, are connected to a greater mortality rate in people that have been infected by the deadly COVID-19 virus; this is an observation that has also been replicated through ecological studies analyzing CFR data of previous non-COVID-19 epidemics.[35] An analysis of the CFR for about 50 states of the US has shown that there is a mortality rate increase with a relative rise in latitude. Furthermore, the CFR was higher for northern states than southern states (6.0% vs. 3.5%, P < .001). These data are reinforced by the article written by Rhodes et al., which states that COVID-19 infection-related deaths around the world were comparatively low for countries of 35° latitude and below. France, Spain, and Italy, European nations where most people suffer from severe Vitamin D deficiency, have the greatest age-specific CFR from COVID-19. This geographic variation in CFRs due to COVID-19 might be then credibly explained by the prevalence of low sun exposure leading to hypovitaminosis D.[36,37,38]

Exceptions do exist, with some northern countries showing lesser mortality and vice versa. This can be attributed to the extensive use of Vitamin D supplements and food fortification in these regions, earlier and more extensive lockdown timelines, racial makeup, sticking to social distancing advice, population density, access to quality medical care, etc.[39] Generally, countries with a government-sponsored Vitamin D fortification program seem to be faring better in terms of COVID-19 disease process and deaths.[40]

Ageusia and Dysgeusia: A Common Presentation of Both COVID-19 and Vitamin D Deficiency

COVID-19 patients have anosmia and ageusia, also seen in some patients with hypovitaminosis D. This is another proof to substantiate the correlation between Vitamin D and COVID-19, implying that COVID-19 infections could be associated with hypovitaminosis D.[41,42,43,44] At this point, studies were undertaken to check Vitamin D status and VDR polymorphisms may give new clues to the various atypical and unique presentations and outcomes of the COVID-19 infection.

The Role that Ethnicity Plays in COVID-19 Infection and Deficiency in Vitamin D

Almost a third of the confirmed cases in England are non-White, as reported by the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre.[45] Similarly, in the United States, a greater number of the African Americans race have been infected by the virus. A similar pattern has been observed during earlier epidemics of influenza too. Currently, the reasons for this strong correlation between ethnicity and COVID-19 are being explored as a matter of public health priority. Several possibilities (all linking hypovitaminosis D and COVID-19) that are being entertained are: (a) Black people are more likely to live in poor neighborhoods, (b) specific minority ethnic groups may suffer from greater prevalence of comorbid diseases burden, and (c) dark-skinned people have lesser Vitamin D concentrations since the high melanin concentrations in dark skin do not permit absorption of adequate ultraviolet, all explaining why Black people are more prone to deficient Vitamin D and thereby an increased susceptibility to viral infections.[46,47,48,49,50]

Angiotensin-converting Enzyme 2 Receptor Enhancement by Vitamin D: A Double-edged Sword?

A strong relationship exists between the levels of Vitamin D and ACE2-the main receptor onto which the CoV attaches.[51] Although Vitamin D escalates ACE2 receptors' expression, which may certainly enhance the virus's binding, it helps the infected person by starkly attenuating the pulmonary vasoconstrictor response seen in COVID-19 cases.

Lung injury due to the exaggerated angiotensin II-mediated responses (systemic vasoconstriction and increase in blood pressure) in influenza is prevented by the ACE2 protein; ACE2 breaks down angiotensin II, thus dropping its levels. COVID-19 downregulates ACE2, resulting in excessive build-up of angiotensin II, which may lead to ARDS, myocarditis, or cardiac injury, complicating care of COVID-19 patients.

Vitamin D is an inhibitor of renin too which is the rate-limiting enzyme for angiotensin II production.

It seems logical then that keeping ACE2 levels elevated in COVID-19 is a wise choice; Vitamin D may help with that considerably. However, conclusions like this warrant strict mechanistic proof, which is lacking at present.

Thrombotic Complications: A Common Presentation in both Hypovitaminosis D and COVID-19 Infection

Thrombotic complications are a common finding in people suffering from COVID-19. More than half the patients with severe COVID-19 disease have higher D-dimer levels. Vitamin D is closely related to the body's thrombotic pathways, and deficiency of Vitamin D has been connected to elevated thrombotic episodes, a correlation strengthening the causal relationship between hypovitaminosis D and COVID-19 infections.[52,53]

Higher Levels of Memory Regulatory T-cells in Women and Its Enhancement by Vitamin D: Possible Cause for a Lower Incidence of COVID-19 among Women

One constant topic of debate currently is whether, a patient once infected with COVID-19, can be re-infected at a later date. Memory regulatory T-cells (mTregs) are produced by virus exposure in virus-infected patients. These linger on in the host that makes re-infection with the same virus a distant possibility.[54] There was a remarkable decrease in the pathological inflammatory lung infiltrate after mTregs were injected into the tail vein of mice exposed to influenza A infection, in contrast to the injection of Tregs in those mice who had no prior exposure to the virus. It is likely that Tregs may have potential dual efficacy (prevention of re-infection and attenuation of disease severity) in combatting viral infection. Since higher levels of Tregs have been observed in women than in men, this might be a reason for women showing lower mortality by COVID-19.[55] Elevated serum levels of Vitamin D may trigger several anti-inflammatory functions including upregulation and increased potency of Tregs, a point in favor of the use of Vitamin D supplements to assist and preserve the number and potency of Tregs.

The Common Profile of Risk Factors for Both Vitamin D Deficiency and COVID-19

Vitamin D deficiency is consistently present in people with obesity, advanced age, smoking history, inadequate sun exposure, dark skin, and comorbid diseases.[34] These are known risk factors for COVID-19 as well.

Landmark Trials and Studies Revealing Important Clues to Establish a Causal Link between Hypovitaminosis D and an Elevated risk of ARTIs and COVID-19

A statement from a recent study stated: “Although contradictory data exist, available evidence indicates that supplementation with multiple micronutrients with immune-supporting roles may modulate immune function and reduce the risk of infection. Micronutrients with the strongest evidence for immune support are Vitamins C and D and zinc. Better design of human clinical studies addressing dosage and combinations of micronutrients in different populations are required to substantiate the benefits of micronutrient supplementation against infection.”[56,57] In a scenario where nothing can be relied upon and it is imperative to act and act fast, these findings can be extrapolated and conclusions drawn toward the formation of a near-normal Vitamin D status through supplementation.

Another study that retrospectively studied the Vitamin D concentration in plasma samples of selected patients from Switzerland found considerably lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels (P = 0.004) in COVID-19-positive (median value 11.1 ng/mL) patients in comparison to COVID-19-negative patients (24.6 ng/mL) that was similarly affirmed by stratifying patients by age >70 years. Here, it was expected that the reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-negative group due to the presence of the respiratory disease may have a lesser median Vitamin D level; even then, the lower Vitamin D level found in the RT-PCR-positive group, suggests that hypovitaminosis D deficiency is more strongly correlated to COVID-19 infection than with other respiratory diseases.[58] Another study comprising 20 patients with COVID-19 reported that hypovitaminosis D is quite common in patients suffering from COVID-19.[59]

A recent “individual patient data” meta-analysis has conclusively proven that supplementing with Vitamin D protects against ARTIs. In a study by Monlezun et al., 58% greater odds of ARTIs was observed in those having Vitamin D levels <30 ng/mL than in those having levels ≥30 ng/mL even after adjusting for demographics and season.[60,61,62] In a clinical trial including postmenopausal women, supplementation with 2000 IU/day of Vitamin D led to fewer RTIs compared to placebo or supplementation with 800 IU/day (30). A meta-analysis done by Charan et al. in 2012, reported a decrease in RTIs postsupplementation.[63] A large-scale systematic review, incorporating data from 7 meta-analyses and evaluating about 30 randomized controlled trials, determined that Vitamin D supplementation, particularly in patients with low baseline Vitamin D, reduces the risk of RTIs. “Vitamin D deficiency contributes directly to the ARDS,” as concluded by Dancer et al. in a study done on a large set of patients with ARDS and a group of patients (esophagectomy patients) who are at risk of contracting ARDS.[64]

Studies not showing any positive correlation also exist, but for most of them, the explanation could be the decreased generation of its active form (1,25-OH2-Vitamin D) which is not adequately formed even after supplementation in patients with chronic kidney or liver disease, inadequate compliance, failure to choose the dose, route, and duration based on preexisting level, etc.[65,66]

In a research paper titled “possible preventive and therapeutic role of Vitamin D in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic,” the authors advise correction of hypovitaminosis D through Vitamin D supplements toward the chemotherapeutic treatment and prevention of COVID-19, along with different preventive approaches like social distancing.[67]

A retrospective cohort research by Meltzer et al. done in 2020, demonstrated that inadequately treated Vitamin D deficiency may enhance the risk of COVID-19 infection. The authors therefore vehemently recommended that deficiency in Vitamin D should be aggressively pursued and treated.[68]

A dose of 50 ng/ml is protective against viral respiratory infections, especially in the elderly, dark-skinned people, and obese people, as suggested by Charan et al. Studies have recommended that those at risk of contracting influenza and/or COVID-19 would be benefitted by attempting to quickly elevate 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations by taking 10,000 IU/d of cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) for several weeks followed by 5000 IU/d. This approach would raise the 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations to over 40–60 ng/mL (100–150 nmol/L.[54] Other studies have revealed that using Vitamin D 200,000–300,000 IU bolus and then reducing to a maintenance dose, lessens the severity and risk of contracting COVID-19.[16]

Safety issues with Vitamin D supplements have hardly if ever been reported and that too at higher doses taken over a prolonged period. Several studies have reported the excellent tolerability of doses up to 100 mg/day, with a review claiming the safety of even 250 micrograms per day.[69,70,71]

A great amount of these data appear to be weak and associative. Nevertheless, it is highly suggestive and the extensive anecdotal evidence and sound scientific basis could help to establish a further link between Vitamin D and COVID-19.

Conclusion

The fact that immunity is important to protect us from invading organisms is common knowledge and nutrition affects immunity in multiple ways; a subnormal micronutrient status retards immunity and increases the chance of several infections. Still, not enough stress is laid to encourage the enhancement of immunity through nutritional strategies during public health policymaking. This is unfortunate, especially since both innate and adaptive immunities revolve around retinol, pyridoxine, cobalamin, ascorbic acid, calciferol, tocopherol, folate, and trace components such as selenium, zinc, iron, magnesium, and copper.

We are yet to know what role exactly Vitamin D has to play in pathogenesis or disease resistance. The route (oral, IV, IM, SC), dosage, frequency (daily or bolus), and safety of Vitamin D in COVID-19-infected patients remain to be ascertained, especially when multiple confounders may confuse the relationship between Vitamin D and disease outcome. Observational studies and reviews can only help us in generating hypotheses and formulating independent associations. For unequivocal confirmation of efficacy, we need to focus on well-designed experimental studies.

As of now, several placebos controlled and dose-ranging clinical trials as documented in the National Institutes of Health clinical trial registry are testing Vitamin D in COVID-19 patients. Some are researching much greater doses against regular doses of the same. Undoubtedly, the results of these trials will tell us whether or not Vitamin D can have a stronghold in the overall picture.

Despite decades of trials and favorable results, not many have actively recommended Vitamin D supplementation for better clinical outcomes in patients with various inflammatory diseases, and much of the clinical data remain to be translated into comprehensive management protocols. All of the abovementioned reasons and evidence could reinforce thorough supplementation with Vitamin D, as potential prophylaxis against COVID-19, especially considering the tolerability and excellent safety profile offered by even high doses of Vitamin D. If the many issues and morbidities associated with COVID-19, such as pneumonia/ARDS, inflammation, inflammatory cytokines, and thrombosis, can be ameliorated by Vitamin D, then the use of supplements would serve as a wonderfully simple solution to lessen the impact of the ravaging pandemic. Even a small benefit can go a long way at this time, justifying supplementation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Forni G, Mantovani A. COVID-19 Commission of Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome. COVID-19 vaccines: Where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:626–39. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corti D, Purcell LA, Snell G, Veesler D. Tackling COVID-19 with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Cell. 2021;184:4593–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benfield T, Bodilsen J, Brieghel C, Harboe ZB, Helleberg M, Holm C, et al. Improved survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 treated with remdesivir and dexamethasone. A nationwide population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 10;:ciab536. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.4de Masson A, Bouaziz JD, Sulimovic L, Cassius C, Jachiet M, Ionescu MA, et al. Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:667–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19 – Preliminary report. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2022236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teymoori-Rad M, Shokri F, Salimi V, Marashi SM. The interplay between vitamin D and viral infections. Rev Med Virol. 2019;29:e2032. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong M, Xiong T, Huang J, Wu Y, Lin L, Zhang Z, et al. Association of vitamin D supplementation with respiratory tract infection in infants. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16:e12987. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujino I, Ushikoshi-Nakayama R, Yamazaki T, Matsumoto N, Saito I. Pulmonary activation of vitamin D3 and preventive effect against interstitial pneumonia. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2019;65:245–51. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.19-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou YF, Luo BA, Qin LL. The association between vitamin D deficiency and community-acquired pneumonia: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17252. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang F, Zhang C, Liu Q, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Qin Y, et al. Identification of amitriptyline HCl, flavin adenine dinucleotide, azacitidine and calcitriol as repurposing drugs for influenza A H5N1 virus-induced lung injury. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008341. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Sousa MÁ, Martínez I, Medrano LM, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Resino S. Vitamin D in human immunodeficiency virus infection: Influence on immunity and disease. Front Immunol. 2018;9:458. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Yang J, Chen J, Luo Q, Zhang Q, Zhang H. Vitamin D alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via regulation of the renin-angiotensin system. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:7432–8. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolliffe DA, Greiller CL, Mein CA, Hoti M, Bakhsoliani E, Telcian AG, et al. Vitamin D receptor genotype influences risk of upper respiratory infection. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:891–900. doi: 10.1017/S000711451800209X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Moreno J, Hernandez JC, Urcuqui-Inchima S. Effect of high doses of vitamin D supplementation on dengue virus replication, Toll-like receptor expression, and cytokine profiles on dendritic cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;464:169–80. doi: 10.1007/s11010-019-03658-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urashima M, Segawa T, Okazaki M, Kurihara M, Wada Y, Ida H. Randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation to prevent seasonal influenza A in schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1255–60. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Du J, Huang L, Wang Y, Shi Y, Lin H. Preventive effects of vitamin D on seasonal influenza A in infants: A multicenter, randomized, open, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:749–54. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabetta JR, DePetrillo P, Cipriani RJ, Smardin J, Burns LA, Landry ML. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and the incidence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianotti G. I'm a Doctor at Italy's Hardest-Hit Hospital. Had to Decide Who Got a Ventilator and Who Didn't. 2020. Mar 27, [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 27]. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-27/coronavirus-doctor-cremona-hospital-decide-who-lives-and-dies/1209091 .

- 19.Chinese Clinical Trial Registry: A Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial for the Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab in the Treatment of New Coronavirus Pneumonia (COVID-19) [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=49409 .

- 20.ClinicalTrials.gov: Tocilizumab in COVID-19 Pneumonia (TOCIVID-19) [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04317092 .

- 21.Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Ogata A, Kishimoto T. A new era for the treatment of inflammatory autoimmune diseases by interleukin-6 blockade strategy. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Q, Zhou YH, Yang ZQ. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:3–10. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labudzynskyi D, Shymanskyy I, Veliky M. Role of vitamin D3 in regulation of interleukin-6 and osteopontin expression in liver of diabetic mice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:2916–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vásárhelyi B, Sátori A, Olajos F, Szabó A, Beko G. Low vitamin D levels among patients at Semmelweis University: Retrospective analysis during a one-year period. Orv Hetil. 2011;152:1272–7. doi: 10.1556/OH.2011.29187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–51. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henley SJ, Gallaway S, Singh SD, O'Neil ME, Buchanan Lunsford N, Momin B, et al. Lung cancer among women in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:1307–16. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malinovschi A, Masoero M, Bellocchia M, Ciuffreda A, Solidoro P, Mattei A, et al. Severe vitamin D deficiency is associated with frequent exacerbations and hospitalization in COPD patients. Respir Res. 2014;15:131. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Jang JG, Hong KS, Park JK, Choi EY. Relationship between serum vitamin D concentrations and clinical outcome of community-acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:729–34. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hope-Simpson RE. The role of season in the epidemiology of influenza. J Hyg (Lond) 1981;86:35–47. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400068728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cannell JJ, Vieth R, Umhau JC, Holick MF, Grant WB, Madronich S, et al. Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:1129–40. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannell JJ, Zasloff M, Garland CF, Scragg R, Giovannucci E. On the epidemiology of influenza. Virol J. 2008;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aloia JF, Li-Ng M. Re: Epidemic influenza and vitamin D. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135:1095–6. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807008308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilie PC, Stefanescu S, Smith L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1195–8. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant WB, Giovannucci E. The possible roles of solar ultraviolet-B radiation and vitamin D in reducing case-fatality rates from the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in the United States. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:215–9. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.4.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes JM, Subramanian S, Laird E, Kenny RA. Editorial: Low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:1434–7. doi: 10.1111/apt.15777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajadi MM, Habibzadeh P, Vintzileos A, Shokouhi S, Miralles-Wilhelm F, Amoroso A. Temperature, humidity, and latitude analysis to estimate potential spread and seasonality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011834. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marik PE, Kory P, Varon J. Does vitamin D status impact mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection? Med Drug Discov. 2020;6:100041. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laird E, Rhodes J, Kenny RA. Vitamin D and inflammation: Potential implications for severity of covid-19. Ir Med J. 2020;113:81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braiman M. Latitude Dependence of the COVID-19 Mortality Rate – A Possible Relationship to Vitamin D Deficiency? SSRN. 2020. Jun, [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 25]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3561958 .

- 41.Bigman G. Age-related smell and taste impairments and vitamin D associations in the U.S. Adults National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients. 2020;12:E984. doi: 10.3390/nu12040984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JE, Oh E, Park J, Youn J, Kim JS, Jang W. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 level may be associated with olfactory dysfunction in de novo Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;57:131–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:2251–61. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lüers JC, Klußmann JP, Guntinas-Lichius O. The COVID-19 pandemic and otolaryngology: What it comes down to? Laryngorhinootologie. 2020;99:287–91. doi: 10.1055/a-1095-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Intensive Care National Audit and Research Center. COVID-19 Study Case Mix Program. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.icnarc.org/

- 46.John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Jun 15]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/racial-data-transparency .

- 47.Khunti K, Singh AK, Pareek M, Hanif W. Is ethnicity linked to incidence or outcomes of covid-19? BMJ. 2020;369:m1548. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O'Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with COVID-19 disease in New York City. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tu H, Tu S, Gao S, Shao A, Sheng J. Current epidemiological and clinical features of COVID-19; a global perspective from China. J Infect. 2020;81:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nair R, Maseeh A. Vitamin D: The “sunshine” vitamin. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:118–26. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.95506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.La Vignera S, Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, Torre F, Aversa A, Calogero AE. Sex-specific SARS-CoV-2 mortality: Among hormone-modulated ACE2 expression, risk of venous thromboembolism and hypovitaminosis D. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:E2948. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giannis D, Ziogas IA, Gianni P. Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104362. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohammad S, Mishra A, Ashraf MZ. Emerging role of vitamin D and its associated molecules in pathways related to pathogenesis of thrombosis. Biomolecules. 2019;9:E649. doi: 10.3390/biom9110649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu C, Zanker D, Lock P, Jiang X, Deng J, Duan M, et al. Memory regulatory T cells home to the lung and control influenza A virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97:774–86. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melzer S, Zachariae S, Bocsi J, Engel C, Löffler M, Tárnok A. Reference intervals for leukocyte subsets in adults: Results from a population-based study using 10-color flow cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2015;88:270–81. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, Baggerly CA, French CB, Aliano JL, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020;12:E988. doi: 10.3390/nu12040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gombart AF, Pierre A, Maggini S. A review of micronutrients and the immune system-working in harmony to reduce the risk of infection. Nutrients. 2020;12:E236. doi: 10.3390/nu12010236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D'Avolio A, Avataneo V, Manca A, Cusato J, De Nicolò A, Lucchini R, et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are lower in patients with positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients. 2020;12:E1359. doi: 10.3390/nu12051359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Razdan K, Singh K, Singh D. Vitamin D Levels and COVID-19 Susceptibility: Is there any Correlation? Med Drug Discov. 2020;7:100051. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wimalawansa SJ. Global epidemic of coronavirus-COVID-19: What we can do to minimize risk. Eur J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2020;7:432–8. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Hooper RL, Greenberg L, Aloia JF, Bergman P, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356:i6583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monlezun DJ, Bittner EA, Christopher KB, Camargo CA, Quraishi SA. Vitamin D status and acute respiratory infection: Cross sectional results from the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001-2006. Nutrients. 2015;7:1933–44. doi: 10.3390/nu7031933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Charan J, Goyal JP, Saxena D, Yadav P. Vitamin D for prevention of respiratory tract infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2012;3:300–3. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.103685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dancer RC, Parekh D, Lax S, D'Souza V, Zheng S, Bassford CR, et al. Vitamin D deficiency contributes directly to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Thora×. 2015;70:617–24. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aglipay M, Birken CS, Parkin PC, Loeb MB, Thorpe K, Chen Y, et al. Effect of high-dose vs standard-dose wintertime vitamin D supplementation on viral upper respiratory tract infections in young healthy children. JAMA. 2017;318:245–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pletz MW, Terkamp C, Schumacher U, Rohde G, Schütte H, Welte T, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in community-acquired pneumonia: Low levels of 1,25(OH)2 D are associated with disease severity. Respir Res. 2014;15:53. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Isaia G, Medico E. Possible prevention and therapeutic role of vitamin D in the management of the COVID-19 2020 pandemics. Torino (ITA): University of Turin; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 01]. Italian. Available from: https://www.unitonews.it/storage/2515/8522/3585/Ipovitaminosi_D_e_Coronavirus_25_marzo_2020 . [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meltzer DO, Best TJ, Zhang H, Vokes T, Arora V, Solway J. Association of Vitamin D Deficiency and Treatment with COVID-19 Incidence. medRxiv [Preprint] 2020 May 13;2020 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vieth R, Kimball S, Hu A, Walfish PG. Randomized comparison of the effects of the vitamin D3 adequate intake versus 100 mcg (4000 IU) per day on biochemical responses and the wellbeing of patients. Nutr J. 2004;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Shao A, Dawson-Hughes B, Hathcock J, Giovannucci E, Willett WC. Benefit-risk assessment of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:1121–32. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:6–18. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]