To the Editor:

Emerging reports demonstrate persistent symptoms and lung function impairment in survivors of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) discharged from the hospital (1–6). However, little is known about the longer-term impact of COVID-19 in patients not requiring hospitalization. We hypothesized that both hospitalized and nonhospitalized survivors of COVID-19 will have persistent symptoms, impaired pulmonary function, and a diminished functional capacity 3 months after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Methods

Patients were prospectively screened and recruited from The Ottawa Hospital administrative registry and from our study website (https://omc.ohri.ca/left/) in sequential order. Patients had to be ⩾18 years of age and diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction 3 months (+6 wk) before enrollment. The study was approved by The Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Patients retrospectively reported the presence and severity of symptoms during the acute phase of illness (5-point scale: 0, absent; 4, very severe) and at the 3-month study visit (6-point scale: 0, absent; 5, much worse now). Patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography, pulmonary function testing, and a symptom-limited incremental (15 watts per minute) cycle cardiopulmonary exercise test (7).

Pulmonary function (8, 9) and cycle cardiopulmonary exercise test variables (10) were referenced to predicted normal values. Chronotropic insufficiency (CI) was defined as a heart rate reserve of <0.8 (11).

Mean differences between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients were evaluated using Student’s t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Binary variables were evaluated using a chi-square test. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Inc.). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and values are reported as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated.

Results

Between June and October 2020, 91 patients were screened for eligibility at The Ottawa Hospital. Of these, 15 refused participation and 13 did not meet the inclusion criteria. At the end, 25 hospitalized and 38 nonhospitalized patients were enrolled. The time to follow up was 119.9 ± 16.2 days after the first positive SARS-CoV-2 test result for hospitalized patients and 129.8 ± 16.5 days for nonhospitalized patients. Hospitalized patients were older and had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, baseline characteristics, admission details, and symptoms in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19

| Hospitalized (n = 25) |

Nonhospitalized (n = 38) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 59.1 ± 13.5 | 42.4 ± 12.9 |

| Sex (male, %) | 64.0 | 52.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.07 ± 7.50 | 28.17 ± 5.62 |

| Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups | 9 (36) | 7 (18.4) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Never-smoker | 17 (68.0) | 28 (73.7) |

| Active smoker | 0 | 0 |

| Past smoker | 8 (32.0) | 10 (26.3) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 2.12 ± 1.72 | 0.37 ± 0.59 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Obesity (BMI ⩾ 30) | 8 (32.0) | 13 (34.2) |

| Hypertension | 10 (40.0) | 4 (10.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (40.0) | 2 (5.3) |

| Diabetes | 10 (40.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Asthma (self-reported) | 9 (36.0) | 9 (23.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 5 (20.0) | 0 |

| Heart failure | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (12.0) | 3 (7.9) |

| Active cancer | 5 (20.0) | 0 |

| COVID-19 illness | ||

| Symptom prevalence | ||

| Exertional breathlessness | 19 (76.0) | 31 (81.6) |

| Mild to moderate | 4 (16.0) | 22 (57.9) |

| Severe to very severe | 15 (60.0) | 9 (23.7) |

| Fatigue | 23 (92.0) | 37 (97.4) |

| Mild to moderate | 7 (28.0) | 13 (34.2) |

| Severe to very severe | 16 (64.0) | 24 (63.2) |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 17.12 ± 17.20 | — |

| Required ICU admission | 10 (40.0) | — |

| Required oxygen | 21 (84.0) | — |

| Completed rehabilitation program | 5 (20.0) | 0 |

| Days to assessment | ||

| Days since first positive COVID-19 test result | 119.9 ± 16.2 | 129.8 ± 16.5 |

| Days since discharge from hospital | 102.3 ± 8.4 | — |

| Symptom persistence 3-mo after COVID-19 illness | ||

| Exertional breathlessness | 17 (68.0) | 21 (55.3) |

| Much or somewhat better | 15 (60.0) | 17 (44.7) |

| Same as during the acute phase of infection | 1 (4.0) | 2 (5.3) |

| Worse or much worse than during the acute phase of infection | 1 (4.0) | 2 (5.3) |

| Fatigue | 18 (72.0) | 27 (71.1) |

| Much or somewhat better | 15 (60.0) | 19 (50.0) |

| Same as during the acute phase of infection | 2 (8.0) | 7 (18.4) |

| Worse or much worse than during the acute phase of infection | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.6) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; ICU = intensive care unit.

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

In both groups, fatigue (hospitalized, 92.0%; nonhospitalized, 97.4%) and exertional breathlessness (hospitalized, 76.0%; nonhospitalized, 81.6%) were frequently reported during the acute phase of COVID-19. At follow up, fatigue (hospitalized, 72.0%; nonhospitalized, 71.1%) and exertional breathlessness (hospitalized, 68.0%; nonhospitalized, 55.3%) persisted as two of the most frequently reported symptoms (Table 1).

Forced vital capacity, total lung capacity (TLC), and the diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DlCO) were lower in hospitalized patients. Subnormal TLC and DlCO were more prevalent in hospitalized patients. Left ventricular ejection fraction was similar between groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spirometry, lung volumes, diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide, transthoracic echocardiography, and measurements at the peak of symptom-limited incremental cycle CPET in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 3–4 months after infection

| Hospitalized (n = 25) | Nonhospitalized (n = 38) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spirometry | ||

| FEV1, % predicted | 90.3 ± 13.5 | 95.5 ± 14.7 |

| FEV1 < LLN | 4 (16.0) | 4 (10.5) |

| FVC, % predicted | 88.6 ± 14.5 | 100.7 ± 14.3* |

| FVC < LLN | 6 (24.0) | 1 (2.6)† |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 76.0 ± 7.0 | 75.5 ± 7.8 |

| FEV1/FVC < LLN | 1 (4.0) | 6 (15.8) |

| Lung volumes | ||

| TLC, % predicted | 84.7 ± 14.5 | 95.7 ± 12.1* |

| TLC < LLN | 12 (48.0) | 3 (7.9)‡ |

| RV, % predicted | 76.5 ± 21.6 | 79.7 ± 17.7 |

| RV < LLN | 8 (32.0) | 4 (10.5) |

| RV/TLC, % predicted | 30.0 ± 6.8 | 24.0 ± 6.7‡ |

| RV/TLC < LLN | 7 (28.0) | 13 (34.2) |

| Diffusing capacity | ||

| DlCO, % predicted | 69.1 ± 14.9§ | 81.5 ± 15.1* |

| DlCO < LLN | 17 (70.8)§ | 12 (31.6)* |

| DlCO/Va, % predicted | 90.7 ± 14.3§ | 96.8 ± 17.0 |

| DlCO/Va < LLN | 2 (8.3)§ | 4 (10.5) |

| Transthoracic echocardiography | ||

| LVEF, % | 63.6 ± 2.5‖ | 62.7 ± 3.7 |

| LVEF < 55% | 0‖ | 1 (2.6) |

| Measurements at the peak of symptom-limited incremental cycle CPET | ||

| Work rate, % predicted | 80.2 ± 24.8 | 99.2 ± 26.1* |

| o2, % predicted | 64.3 ± 19.2 | 83.5 ± 17.9‡ |

| o2% predicted <85% | 20 (80.0) | 21 (55.2)* |

| co2, L/min | 1.73 ± 0.65 | 2.43 ± 0.80‡ |

| RQ | 1.24 ± 0.11 | 1.24 ± 0.09 |

| RQ < 1.05 | 1 (4.0) | 1 (2.6) |

| HR, % predicted | 86.1 ± 15.0 | 97.0 ± 9.0* |

| O2 pulse, % predicted | 71.9 ± 19.3 | 81.3 ± 12.8† |

| HRR, % | 65.4 ± 24.6 | 87.9 ± 18.8‡ |

| HRR < 0.8 | 17 (68.0) | 7 (18.4)‡ |

| SpO2, % | 97.0 ± 1.5 | 97.0 ± 1.7 |

| e, % predicted MVV | 51.0 ± 13.1 | 57.8 ± 12.2† |

| e/co2, nadir | 32.40 ± 5.65 | 29.04 ± 4.16* |

| IC, % predicted | 80.6 ± 17.9 | 92.4 ± 15.9* |

| IRV, L | 0.92 ± 0.50 | 1.13 ± 0.48 |

| Symptoms, Borg scale 0–10 | ||

| Breathlessness intensity | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.2 |

| Leg discomfort | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 7.8 ± 2.1 |

| Reason for stopping | ||

| Breathing discomfort | 3 (12.0) | 12 (31.6) |

| Leg discomfort | 13 (52.0) | 17 (44.7) |

| Combination of breathing and legs | 7 (28.0) | 9 (23.7) |

| Other | ||

| Anxiety | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Knee pain | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

Definition of abbreviations: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; CPET = cardiopulmonary exercise test; DlCO = diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC = forced vital capacity, HR = heart rate; HRR = heart rate reserve; IC = inspiratory capacity; IRV = inspiratory reserve volume; LLN = lower limit of normal; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MVV = maximum voluntary ventilation; RQ = respiratory quotient; RV = residual volume; SpO2 = oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry; TLC = total lung capacity; Va = alveolar volume; co2 = carbon dioxide production; e = minute ventilation; o2 = oxygen consumption.

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

n = 24, one patient was unable to perform DlCO.

n = 24, one patient did not complete transthoracic echocardiography.

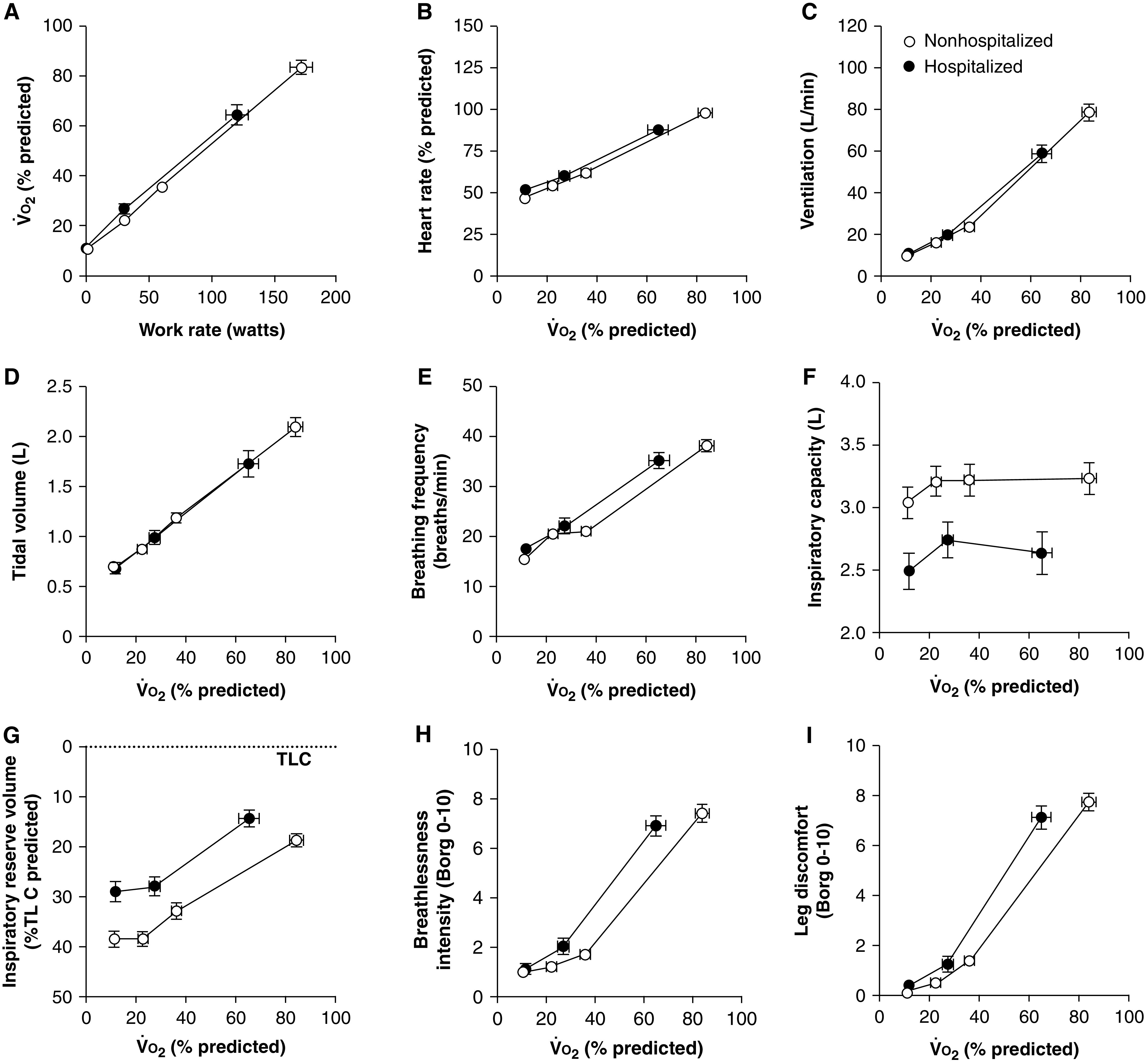

Peak oxygen consumption (o2) % predicted was lower in hospitalized versus nonhospitalized patients (hospitalized, 64.3 ± 19.2%; nonhospitalized, 83.5 ± 17.9%). Indices of respiratory mechanics, including inspiratory capacity and inspiratory reserve volume, were lower for a given o2 in hospitalized patients (Table 2, Figure 1). Peak heart rate, heart rate reserve, and oxygen pulse were lower, and the ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide nadir was higher in hospitalized patients. CI was identified in 68.0% of hospitalized and 18.4% of nonhospitalized patients (Table 2). CI could not be explained by medication use alone, as only 35.0% and 0.0% of hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with CI, respectively, were receiving heart rate–modifying treatment. Breathlessness and leg discomfort ratings were higher for a given o2 in hospitalized patients but were not different between groups at end-exercise (Table 2, Figure 1). Leg discomfort was the most frequently reported locus of symptom limitation to exercise in both groups, although it occurred at a lower peak o2 in hospitalized versus nonhospitalized patients (Table 2).

Figure 1.

(A–I) o2 during an incremental cycle exercise test (A), and heart rate (B), ventilation (C), tidal volume (D), breathing frequency (E), inspiratory capacity (F), inspiratory reserve volume (G), breathlessness intensity (H), and leg discomfort (I) for a given o2% predicted in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 3–4 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data presented at rest, iso-work rate (highest equivalent work rate completed by all patients within each group), and peak exercise. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TLC = total lung capacity; o2 = oxygen consumption.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies, we found that hospitalized and nonhospitalized survivors of COVID-19 report persistent fatigue and exertional breathlessness and exhibit impaired lung function and diminished functional capacity 3–4 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection (1–6). Although cardiopulmonary abnormalities were observed in both groups, they were more prevalent and severe in hospitalized patients.

Nonresolving lung parenchymal or pulmonary vascular lesions from the time of the acute infection (4) may account for the higher rate and severity of pulmonary sequelae in hospitalized patients. Persistent breathlessness in hospitalized patients may partly be explained by the residual impairments in TLC and DlCO. Although these findings are consistent with studies that evaluated breathlessness in patients with similar lung function defects (12), we cannot rule out the confounding effects of age, obesity, and comorbid conditions on lung mechanics, which may explain some of the differences between groups. Furthermore, extrapulmonary factors likely also contributed to breathlessness during exercise, as both groups reported severe breathlessness (Borg > 6) at end-exercise despite the presence of a ventilatory reserve.

Cardiorespiratory fitness is a powerful predictor of mortality in the general population (13). It is therefore striking that >50% of our COVID-19 survivors had a peak o2 below 85% predicted, a rate that is comparable to patients recovered from severe acute respiratory syndrome (14). The respiratory quotient >1.05 in conjunction with a ventilatory reserve at peak exercise suggests that cardiovascular factors were the primary cause of exercise limitation in both groups. Impaired tissue perfusion and/or skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction may be significant mediators of a low o2, particularly in hospitalized patients who reported higher leg discomfort for a given o2. This hypothesis is supported by the observed reduction in oxygen pulse in the context of a preserved ejection fraction in hospitalized patients, increasing evidence of COVID-19–related microvascular injury in various organs and the effects of critical illness on muscle wasting (15). Furthermore, compromised oxygen use at the peripheral muscles may exacerbate symptom perception, which may result in the early attainment of intolerable breathlessness and premature termination of exercise (16, 17). Physical deconditioning and concurrent comorbid conditions likely also contributed to the reduction in peak o2 in hospitalized patients. Finally, poor cardiorespiratory fitness in hospitalized patients may have preceded SARS-CoV-2 infection (18).

We provide the first report of CI in patients recovering from COVID-19. The lower peak o2 and heart rate in hospitalized versus nonhospitalized patients in the setting of a comparable peak respiratory quotient suggests that CI contributed to exercise limitation. The source of CI is unknown but may be due to the high prevalence of comorbid conditions in hospitalized patients, or it may be secondary to patients becoming breathless and terminating exercise before achieving a maximal heart rate response.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, lack of premorbid baseline information, and absence of matched control groups. Therefore, we cannot be certain if the physiologic abnormalities in our patients preceded or followed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Given the important differences in the demographic and clinical makeup of our study groups, we could not adequately assess the confounding effects that preexisting comorbidities could have on our observations. Finally, we caution against the generalizability of our results given the small sample size and use of Canadian reference values (8–10).

In conclusion, we demonstrate mild impairments in lung volumes and gas exchange and a diminished functional capacity 3–4 months after discharge from hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which occurred in the presence of a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Investigations into the effects of COVID-19 on peripheral muscle structure, perfusion, and function are warranted. Additional studies are required to understand the mechanisms of breathlessness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in patients not requiring hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Lori Ann Smith-Seguin, Nathalie Duffy, and Mylene Michaud for performing all pulmonary function and cycle cardiopulmonary exercise test procedures. They also thank Isabelle Seguin-Latreille, Danielle Tardiff, Laurie Bretzlaff, Wendy Fusee, Bashour Yazji, and Caroline Tessier for their assistance in coordinating the study.

Footnotes

Supported by The Ottawa Hospital COVID-19 Emergency Response Fund. S.J.A. and J.C. report grants from The Ottawa Hospital Foundation during the conduct of the study. K.L.L. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Sojecci, and Abbvie outside of the submitted work. J.C. reports personal fees from Sanofi-Genzyme outside of the submitted work.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: S.J.A. Design: S.J.A., N.V., V.F.C.-M., K.T., R.E.R.R., K.L.L., and J.C. Data collection: S.J.A., N.V., M.M., A.P., A. Chopra, A.L., H.A.G., A. Crawley, and J.C. Data analysis: S.J.A., N.V., and J.A.C. Data interpretation: S.J.A., N.V., V.F.C.-M., J.A.C., and J.C. Manuscript writing: S.J.A. Manuscript review: all authors. S.J.A. had full access to the study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA . 2020;18:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D’Cruz RF, Waller MD, Perrin F, Periselneris J, Norton S, Smith LJ, et al. Chest radiography is a poor predictor of respiratory symptoms and functional impairment in survivors of severe COVID-19 pneumonia. ERJ Open Res . 2021;18:00655-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00655-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goërtz YMJ, Van Herck M, Delbressine JM, Vaes AW, Meys R, Machado FVC, et al. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res . 2020;18:00542-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lerum TV, Aaløkken TM, Brønstad E, Aarli B, Ikdahl E, Lund KMA, et al. Dyspnoea, lung function and CT findings three months after hospital admission for COVID-19. Eur Respir J . 2021;18:2003448. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03448-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, Brown JS, Denneny EK, Hare SS, et al. ARC Study Group. ‘Long-COVID’: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax . 2020 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, Filippini N, Griffanti L, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine . 2021;18:100683. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Voduc N, la Porte C, Tessier C, Mallick R, Cameron DW. Effect of resveratrol on exercise capacity: a randomized placebo-controlled crossover pilot study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab . 2014;18:1183–1187. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tan WC, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Chapman K, Cowie R, FitzGerald MJ, et al. LHCE study investigators. Canadian prediction equations of spirometric lung function for Caucasian adults 20 to 90 years of age: results from the Canadian Obstructive Lung Disease (COLD) study and the Lung Health Canadian Environment (LHCE) study. Can Respir J . 2011;18:321–326. doi: 10.1155/2011/540396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gutierrez C, Ghezzo RH, Abboud RT, Cosio MG, Dill JR, Martin RR, et al. Reference values of pulmonary function tests for Canadian Caucasians. Can Respir J . 2004;18:414–424. doi: 10.1155/2004/857476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewthwaite H, Benedetti A, Stickland MK, Bourbeau J, Guenette JA, Maltais F, et al. CanCOLD Collaborative Research Group and the Canadian Respiratory Research Network. Normative peak cardiopulmonary exercise test responses in Canadian adults aged ≥40 years. Chest . 2020;18:2532–2545. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khan MN, Pothier CE, Lauer MS. Chronotropic incompetence as a predictor of death among patients with normal electrograms taking beta blockers (metoprolol or atenolol) Am J Cardiol . 2005;18:1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Faisal A, Alghamdi BJ, Ciavaglia CE, Elbehairy AF, Webb KA, Ora J, et al. Common mechanisms of dyspnea in chronic interstitial and obstructive lung disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2016;18:299–309. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0841OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA . 2009;18:2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ong KC, Ng AW, Lee LS, Kaw G, Kwek SK, Leow MK, et al. Pulmonary function and exercise capacity in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Eur Respir J . 2004;18:436–442. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA . 2013;18:1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amann M, Blain GM, Proctor LT, Sebranek JJ, Pegelow DF, Dempsey JA. Group III and IV muscle afferents contribute to ventilatory and cardiovascular response to rhythmic exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol . 2010;18:966–976. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gagnon P, Bussières JS, Ribeiro F, Gagnon SL, Saey D, Gagné N, et al. Influences of spinal anesthesia on exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012;18:606–615. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brawner CA, Ehrman JK, Bole S, Kerrigan DJ, Parikh SS, Lewis BK, et al. Inverse relationship of maximal exercise capacity to hospitalization secondary to coronavirus disease 2019. Mayo Clin Proc . 2021;18:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]