Abstract

Purpose

Morse code as a form of communication became widely used for telegraphy, radio and maritime communication, and military operations, and remains popular with ham radio operators. Some skilled users of Morse code are able to comprehend a full sentence as they listen to it, while others must first transcribe the sentence into its written letter sequence. Morse thus provides an interesting opportunity to examine comprehension differences in the context of skilled acoustic perception. Measures of comprehension and short-term memory show a strong correlation across multiple forms of communication. This study tests whether this relationship holds for Morse and investigates its underlying basis. Our analyses examine Morse and speech immediate serial recall, focusing on established markers of echoic storage, phonological-articulatory coding, and lexical-semantic support. We show a relationship between Morse short-term memory and Morse comprehension that is not explained by Morse perceptual fluency. In addition, we find that poorer serial recall for Morse compared to speech is primarily due to poorer item memory for Morse, indicating differences in lexical-semantic support. Interestingly, individual differences in speech item memory are also predictive of individual differences in Morse comprehension.

Conclusions

We point to a psycholinguistic framework to account for these results, concluding that Morse functions like “reading for the ears” (Maier et al., 2004) and that underlying differences in the integration of phonological and lexical-semantic knowledge impact both short-term memory and comprehension. The results provide insight into individual differences in the comprehension of degraded speech and strategies that build comprehension through listening experience.

Supplemental Material

Humans are born with the ability to acquire a spoken language. They extend this capacity by learning to use culturally instructed symbols to represent units of speech or meaning, for instance by acquiring the ability to read. Auditory Morse code is an acoustic form of symbolic communication based on the English alphabet that can function like “reading for the ears” (Maier et al., 2004). Here, the well-documented relationship between reading comprehension and verbal short-term memory (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993) leads us to investigate the potential for a similar relationship between Morse comprehension and verbal short-term 1 memory.

Morse Perceptual Fluency, Comprehension, and Short-Term Memory

Morse code was developed as an informationally efficient and robust communication system for telegraphy and maritime use (Fahie, 1884), and today, it is most commonly used by amateur radio enthusiasts (Coe, 2003; Halstead; 1949; Turnbull, 1853). An auditory Morse message consists of sequences of short and long tone pips (spoken as “dit” and “dah,” and written as “.” and “-”). Each letter of the Roman alphabet is represented by a unique combination of “dits” and “dahs.” Perceptual Morse fluency is standardly measured by “copy speed,” which is the fastest presentation rate at which a user can accurately transcribe a Morse message into its corresponding English letter sequence.

Some skilled Morse users are able to comprehend a Morse message as they listen to it, in a speechlike manner, without first transcribing it into printed English (for an example, see Supplemental Material S1). The ability to comprehend Morse online has been previously described within the literature but has received little investigation. In the current study, we assess speechlike Morse comprehension using a sentence repetition task. Spoken sentence repetition crucially rests upon the meaningful interpretation of the incoming information (G. A. Miller & Isard, 1963; Potter, 2012; Potter & Lombardi, 1990). Thus, when comprehension is intact, spoken sentences can be readily repeated with high accuracy, and poor performance is diagnostic of a comprehension disorder or low language proficiency (Klem et al., 2015; Marinis et al., 2017; McCarthy & Warrington, 1987; Theodorou et al., 2017; Ziethe et al., 2013). Similarly, repeating a Morse sentence is straightforward for individuals who self-report spontaneous online comprehension (see Supplemental Material S2), but difficult for those without this skill.

We also measure individual differences in Morse perceptual fluency, in this case using a Morse transcription task in which participants copy a spoken Morse sentence letter-by-letter into its English equivalent, concurrently with the sentence presentation. Importantly, similar to the ability to repeat spoken pseudowords, the transcription of a Morse word can be done without meaningful interpretation of the input. The widespread wartime use of Morse code, for instance, often involved the high-speed copying and receiving of Morse messages crafted using encryption algorithms that made comprehension impossible (Sterling, 2008; Turnbull, 1853).

Finally, we measure short-term memory for Morse and speech lists using an immediate serial recall task. This task is similar to digit and letter span tasks that are widely used in assessments of language and reading abilities (e.g., Gathercole, 1999). Measures of comprehension and short-term memory show a strong correlation across multiple forms of communication, including spoken English, written English, and American Sign Language (Ben-Yehudah & Fiez, 2007; Emmorey et al., 2017; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993; Just & Carpenter, 1992). If Morse functions like “reading for the ears,” individual differences in Morse short-term memory should predict differences in Morse comprehension, above any potential contributions from perceptual abilities.

Comparing Morse and Speech Short-Term Memory

Morse, where skilled perception is not necessarily associated with skilled comprehension, offers an opportunity to gain new insights into the relationship between short-term memory and comprehension. We focus on aspects of short-term memory performance that have been associated with three different speech-language abilities: (a) recency and suffix effects as markers of echoic storage, (b) order errors as a marker of phonological-articulatory coding, and (c) item errors as a marker of lexical-semantic support.

Echoic Storage

Echoic storage is thought to involve the retention of a single acoustic item in a short-term memory store. Evidence for echoic storage comes from the recency effect, which is the recall advantage observed for a final as compared to penultimate list item. It is typically observed for auditory lists but not written lists (Crowder & Morton, 1969; Frankish, 1996). By some accounts, the echoic store is speech-specific (e.g., Eimas et al., 1973; Liberman et al., 1967; c.f. Frankish 1996), in which case a recency effect should not be observed for Morse lists. Others have argued that nonspeech acoustic stimuli can benefit from echoic storage under some conditions. For example, Greene and Samuel (1986) found a recency effect in the recall of an auditory tone sequence by skilled musicians, and suggested that experience-dependent shaping of acoustic perception may lead to enhanced recency effects (Frankish, 1996; Greene & Samuel, 1986). Thus, differences between Morse and speech recency effects would provide evidence of underlying differences in echoic storage.

Suffix manipulations permit a further probe of echoic storage. A spoken suffix is an additional item presented at the end of the list that is not to be recalled and is thought to gain access to the echoic store, thereby displacing a final speech list item from memory and disrupting the recency effect (e.g., Crowder, 1978). This displacement from echoic storage is sensitive to the acoustic similarity between the final item and the suffix (Crowder & Morton, 1969; Frankish, 1996). For our task, on some trials an irrelevant Morse or spoken letter (i.e., a suffix) is presented. Since Morse and speech are acoustically very distinct, a speech but not a Morse suffix should displace the final item from a speech list, and thereby, reduce the recall of the final item in a spoken list. Conversely, if Morse recall benefits from echoic storage, then a Morse but not a speech suffix should reduce the recall of a final item in a Morse list. Overall, differences between Morse and speech suffix effects would provide additional evidence of underlying differences in echoic storage.

Phonological-Articulatory Coding

Both spoken and written lists are thought to benefit from phonological-articulatory coding. Though theories of short-term memory differ in important details, a common idea is that both spoken and written items can gain access to an amodal phonological store associated with speech planning, which allows the items to be retained using articulatory rehearsal (Baddeley, 1986) or another speech-based strategy, but makes the items prone to confusions based on phonological similarity (Jones et al., 2004; Page & Norris, 1998). Thus, differences between Morse and speech lists in patterns of item confusions would provide evidence of underlying differences in phonological-articulatory coding.

Lexical-Semantic Support

Lexical-semantic information is thought to protect against the degradation of items within phonological memory and facilitate memory repair (e.g., Jefferies et al., 2009; Savill et al., 2018). This is supported by studies demonstrating effects of lexical and semantic variables on short-term memory performance. For instance, recall is greater for lists of words as compared to nonwords, concrete as compared to abstract words, and high as compared to low frequency words (Hulme et al., 1997; Jefferies et al., 2006a, 2006b; Lewandowsky & Farrell, 2000; L. M. Miller & Roodenrys, 2009; Poirier & Saint-Aubin, 1996; Quinlan et al., 2017; Saint-Aubin & Poirier, 1999). Importantly, such lexical and semantic variables influence the rate of item but not order errors (Lewandowsky & Farrell, 2000). Thus, differences between Morse and speech lists in item errors would provide evidence of underlying differences in the use of lexical-semantic support to maintain items in phonological memory.

Summary

To summarize, in this study, we recruit skilled users of Morse code and assess their abilities to repeat a Morse sentence, transcribe a Morse sentence, and immediately recall Morse and speech lists in the order of their presentation. We expect to find individual differences in Morse comprehension that cannot be simply explained by individual differences in perceptual fluency. We also assess whether short-term memory performance for Morse and speech exhibit differences in echoic storage, phonological-articulatory coding, and lexical-semantic support.

Method

Participants

Participants were required to hold an amateur radio license and possess a self-reported skill level of sending and receiving Morse at 15 words per minute or above. All participants reported extensive years of experience with Morse (20–54 years). The subjects provided informed consent prior to participation according to a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and paid for their participation.

Twenty-five participants completed this study. An initial set of six participants completed the study in the laboratory. Due to difficulties in recruiting such a specialized sample, the procedures were modified to permit recruitment and testing of geographically distant participants, and the remaining 19 participants performed the experiment at home. For these participants, the experimental materials and equipment were sent to their residence, and included headphones, program installation software, a flash drive, two spiral bound answer booklets, comment sheets, instruction packets, and prepaid return postage. After each participant received the materials, a scheduled phone call with an experimenter provided an opportunity to review the materials and address any points of uncertainty. Participants were asked to complete all parts of the study within a week, calling the investigator if they experienced any confusion or problems executing the experiment. Crucially, the instructions, stimuli, response output, and experimental software were identical across the laboratory and at-home participant groups. Following data collection, three participants were excluded from analyses for not following instructions (e.g., reporting the suffix) and one for data loss. The reported data are from the remaining 21 participants, all of whom are male (mean age of 59 years ±9 SD).

To maximize our sample size, we recruited expert Morse code users over a 2-year period, using advertisements sent to Morse code clubs and organizations, and recruitment tables at amateur radio festivals until we exhausted this recruitment network. By leveraging the use of both in-lab and at-home testing, we were able to obtain a sample size consistent with that reported in other short-term memory studies (e.g., Frankish, 2008) that examine different error types produced by stimulus differences (e.g., intelligible vs. clear speech). However, a limitation of this study is that it is underpowered to observe subtle effects. In addition, any study conducted outside of the laboratory faces additional challenges such as monitoring compliance with instructions. For instance, although we saw no evidence of this, individuals could have disregarded our instruction to immediately write each letter as they heard it in our perceptual fluency task.

Stimulus Materials

Using freely available online software, 18 English sentences were transcribed into Morse code at three different rates (16, 19, and 25 words per minute). The sentences were divided into two sets, with the assignment to a sentence comprehension versus perceptual fluency task counterbalanced across participants, matched for average number of words across sentences in each task, for each participant. The sentences were 5–7 words and created to be plausable but not predictable. The audiofile from one sentence was accidentally misnamed causing one of the sentences to be omitted and replaced with another in some participants, and so these sentences were not included in the scoring for any participant. The same software was used to create audio files for eight Morse letters (H, R, W, M, F, X, K, L). Audio recordings were also created of a female native English speaker naming aloud the same set of letters. The resulting files were used as Morse and Speech list items (H, R, W, M, F, X, K, L) and an irrelevant suffix item (Q) in an immediate serial recall task.

Experimental Design

The study consisted of a Morse sentence comprehension task, a Morse perceptual fluency task, and an immediate serial recall task. Additionally, prior to this experiment, participants performed an initial immediate serial recall task with 5-item lists across three presentation modalities (written, speech, Morse). These results are not included because most participants performed at or near ceiling for all conditions.

Morse Comprehension and Perceptual Fluency

For the Morse sentence comprehension task, participants were presented with nine sentences at three different rates (16, 19, and 25 words per minute). Participants were asked to write each sentence in English on paper as soon as they finished hearing it. To assess Morse perceptual fluency, participants were presented with nine sentences at three different rates (16, 19, and 25 words per minute). Participants were asked to write down (“copy”) each sentences in English as they were listening to them. Performance was coded as the proportion of accurately transcribed words.

Morse and Speech Short-Term Memory

For the immediate serial recall task, participants first heard a list of letters, and then immediately following the list presentation they were instructed to write the presented items as English letters in their order of presentation, and if they could not recall a letter, they allowed to mark an omitted response in any give position. Stimuli were presented acoustically at a rate of one letter every 1.5 s. The list of letters for a given trial was randomly selected without replacement from pool of eight letters (H, R, W, M, F, X, K, L). On some trials, an additional letter (Q) was presented 500 ms after the onset of the response cue. Participants were instructed not to report this suffix item. Each list was immediately followed by a visual response cue that prompted subjects to write down their responses on a separate notecard for each trial. The task used a 2 × 3 × 2 design with stimulus type (speech, Morse), suffix type (speech, Morse, none), and list length (4 or 6 letters) as within-subject factors. There were 10 trials per condition. Stimulus type was blocked and counterbalanced across participants, such that a participant first completed either all of the Morse or all of the speech. Within each type of block, the no-suffix condition always occurred first, and the remaining two suffix conditions were presented in random order. List length was blocked such that the four letter lists were presented first in each condition. A brief practice session was used to familiarize participants with the task. For at-home participants, this was done with the experimenter over the phone. Nearly all participants exhibited perfect or near-perfect recall of the 4-item lists, and so the data from this condition are not included in the reported analyses.

Analysis Approach

Overall Measures of Task Performance and Relationships Between Tasks

In the first stage of data analysis, we computed the overall level of accuracy for the Morse comprehension, Morse perceptual fluency, and the serial recall tasks for the Morse and Speech conditions, separately. Accuracy on the Morse comprehension and perceptual fluency tasks was coded as the percentage of correctly produced words across the three different rates of sentence presentation. Accuracy on the serial recall task was defined as a correct item in the correct position. We then used paired t-tests to compare Morse comprehension and perceptual fluency accuracy, and to compare serial recall accuracy for the Morse and speech conditions. Lastly, we examined the correlations between Morse short-term memory and comprehension, above and beyond those explained by individual differences in Morse perceptual fluency. This analysis was implemented as a hierarchical regression model in which Morse perceptual fluency was entered as the first predictor followed by overall Morse short-term memory.

Investigating Components of Short-Term Memory

A second set of analyses examined specific aspects of short-term memory performance, with the goal of better understanding observed differences between Speech and Morse serial recall. To probe for differences in echoic storage, we first tested for recency effects in Morse and Speech conditions; this was done through paired t-tests comparing accuracy at position 5 versus 6 using data from the No-Suffix condition only, to avoid possible effects of a suffix item on echoic storage. Another paired t -test compared the size of the effect across the two conditions, subtracting accuracy for position 5 from postion 6 to compute a difference value that was used as the dependent measure. As another way to probe the nature of echoic storage for Morse and Speech lists, we used a generalized linear mixed effects model (implemented in R with glmer and the nlme package) to investigate the effects of our suffix conditions on the recall of the most recent list item. This model included List condition (Morse, speech) and all three suffix conditions (no-suffix, speech suffix, Morse suffix) as factors, participant as a random factor, and single trial accuracy of the final item as the dependent measure. 2

To evaluate differences in phonological-articulatory coding and lexical-semantic support, incorrect responses on the immediate serial recall task were coded as either an order or an item error. Order errors were defined as the recall of a list item in an incorrect list position. Item errors were defined as an omitted response for a given list position or the recall of an item not presented on the list. For each participant, we computed the mean rate of order errors for each list condition, collapsing across the three different suffix conditions. Separate paired t-tests were used to compare the rate of order errors between Morse and Speech conditions, and the rate of item errors between Morse and Speech conditions. In addition, we examined the correlation between the patterns of order errors for Morse and Speech. This was done by computing the frequency at which each spoken letter was mistakenly swapped with another spoken letter at recall (e.g., number of times F was swapped with R), and the frequency at which each Morse letter was swapped with another Morse letter at recall to generate separate confusion matrices for Morse and Speech. We then conducted a Pearson correlation analysis between the two resulting confusion matrices in R.

Relationship Between Item Memory and Morse Comprehension

Because we presume that lexical-semantic information is common to Speech and Morse, we wondered if individual variability in lexical-semantic support for Speech (measured as item memory for speech) could partially account for differences in Morse comprehension. To answer this question, a hierarchical linear regression tested whether individual item errors for Speech predicted individual differences in Morse comprehension, and whether item errors for Morse accounted for any additional variability in comprehension above and beyond the variability that was predicted by speech item memory. We tested this through a hierarchical regression model. To minimize any effects due to differences in echoic storage, data were only included from the congruent suffix conditions (Morse lists with a Morse suffix, speech lists with a speech suffix).

Results

Overall Measures of Task Performance and Relationships Between Tasks

Accuracy on the Morse comprehension task was more variable and slightly poorer (M = 85%, SD = 19%, range 40%–100%) than accuracy on the Morse perceptual fluency task (M = 90%, SD = 12%, range 55%–100%). Accuracy on the serial recall task was poorer for Morse as compared to speech lists, M = 74% (SD = .19) for Morse, M = 83% (SD = .15) for speech, t(21) = −4.23, p < .001).

Measures of comprehension and short-term memory typically show a strong correlation (Emmorey et al., 2017; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993; Just & Carpenter, 1992). To test whether this is true for Morse, over and above any contributions from perceptual fluency, we conducted a hierarchical regression with Morse perceptual fluency and Morse short-term memory accuracy as predictors of Morse comprehension accuracy. Adding Morse short-term memory to the model significantly changed the R value from .32 to .55 (see Table 1), and short-term memory significantly predicted comprehension, p = .037.

Table 1.

Hierarchical linear regression for Morse comprehension using perceptual fluency and Morse short-term memory as predictors.

| Predictor | B | SE b | β | t value | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | .17 | .30 | |||

| Copy performance | −.39 | .32 | .25 | 1.24 | .231 |

| Morse short-term memory | −.45 | .20 | .45* | 2.25 | .037 |

Note. R2 = .30 corrected R_corr 2 = .22; B = unstandardized coefficient; SE b = standard error of the coefficient; β = standardized coefficient.

p < .05.

Investigating Components of Short-Term Memory

To understand the component abilities that might underlie the poorer serial accuracy for Morse as compared to Speech lists, we conducted a series of analyses focusing on (a) recency and suffix effects as markers of echoic storage and (b) order and item errors as markers of phonological-and lexical-semantic support, respectively.

Echoic Storage

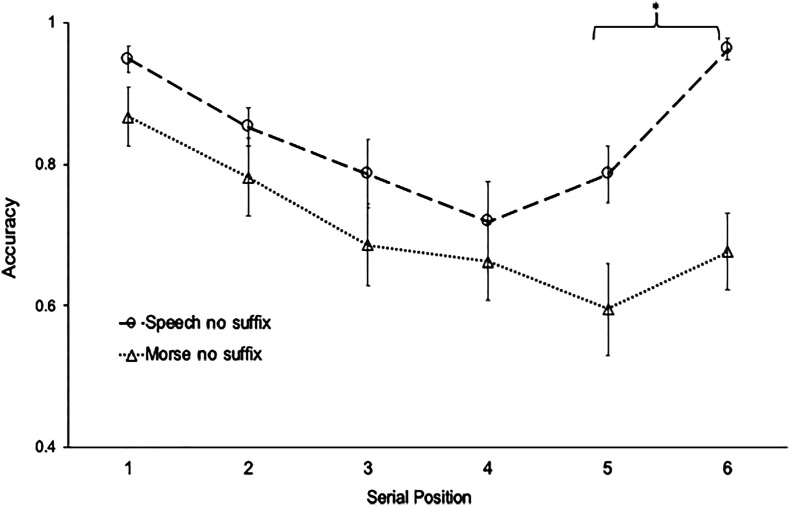

Planned analyses comparing positions 5 and 6 revealed a significant recency effect for speech, t(20) = −4.32, p < .001, and a trend for a significant recency effect for Morse, t(20) = −1.94, p = .067; the size of the recency effect did not significantly differ for Morse code as compared to Speech lists, t(20) = −1.69, p = .106 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall accuracy at each serial position speech (circles) and Morse (triangles) lists. Recall accuracy is the proportion of items recalled correctly in the correct position.

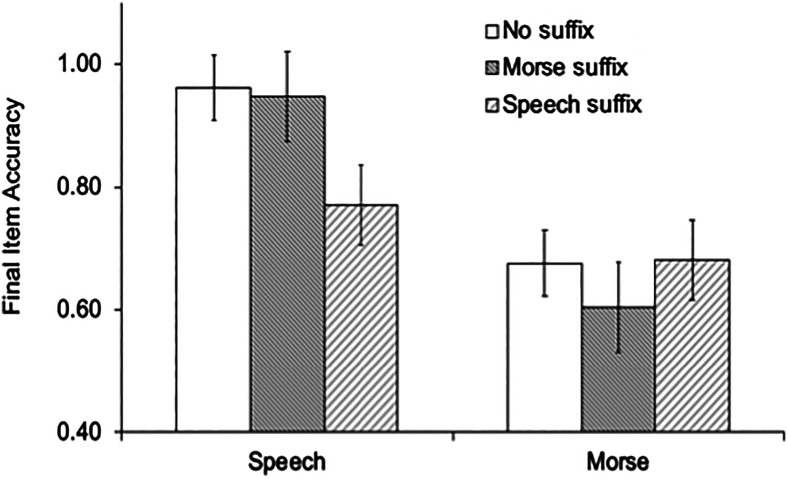

Suffix effects were examined with a generalized linear mixed effects model that revealed a significant main effect of List condition, p < .001, main effect of suffix, p = .005, and two-way list × suffix interaction, p < .001. Further, post hoc t-tests at the final position revealed the expected pattern of results for a spoken list: presentation of an acoustically similar (speech) suffix resulted in poorer final item recall as compared to presentation of an acoustically dissimilar suffix (see Figure 2), whereas results for Morse trended in the expected directions, but did not reach significance.

Figure 2.

Final item accuracy for speech and Morse lists. For speech, speech suffix condition results poorer final item recall as compared to Morse suffix, t(20) = −3.94, p = .001, or no suffix, t(20) = −4.48, p < .001. For Morse showed a similar pattern emerges but does not reach significance: poorer final item recall for Morse suffix condition as compared to presentation of an acoustically dissimilar (speech) suffix, t(20) = −1.67, p = .11, or no suffix, t(20) = −1.75, p = .10.

Taken together, the key effects of recency and suffix effects for Morse that would provide evidence for speechlike storage of a final Morse item in echoic memory (Crowder & Morton, 1969) were not statistically robust (despite exhibiting a pattern consistent with speech), and so the evidence that supports this conclusion is weak at best. Additionally, while list differences were observed, the size of the effects are too small to account for the large difference in overall short-term memory accuracy for Morse as compared to speech.

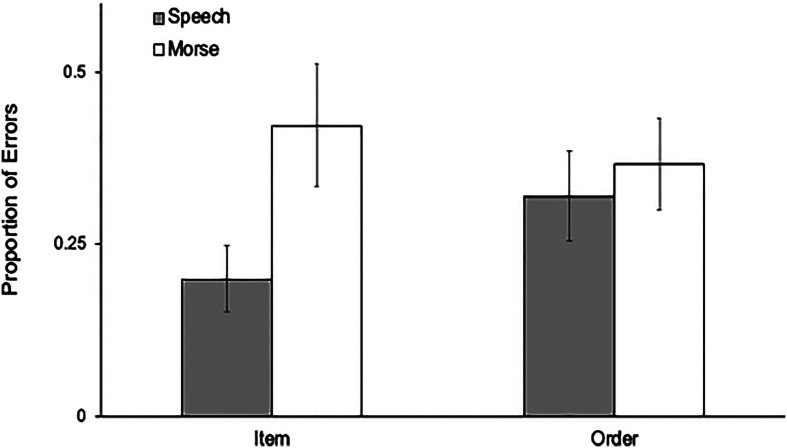

Patterns of Order and Item Errors

Similar rates of order errors were observed for Morse (M = .37, SE = .05) and speech lists (M = .32, SE = .06), and a t-test comparing the two rates yielded a non-significant result, t(21) = .95, p = .36. We also compared the confusion matrices for Morse and speech items using a Pearson correlation analysis and found a significant correlation, r(62) = .36, t = 3.07, p = .003. The results are consistent with the idea that the ordered recall of Morse and speech lists both rely on a speech-based mechanism in which order information is sensitive to phonological confusability between items.

We also computed the overall number of item errors for each list condition, collapsing across the three different suffix conditions. We observed higher rates of item errors for Morse lists (M = .42, SE = .09) than speech lists (M = .17, SE = .05) with a t-test revealing a highly significant difference between the two list conditons, t(20) = 5.17, p < .001. This result indicates that items in a Morse list are more likely to be forgotten than items in a speech list (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of item and order errors. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean over subjects.

Relationship Between Item Memory and Morse Comprehension

In a final analysis we investigated whether individual differences in item errors for Speech predict differences in Morse comprehension, and whether item errors for Morse accounted for any additional variability in comprehension above and beyond the variability that predicted by speech. We found that item memory for speech significantly predicted Morse comprehension, corrected R2 = .31, F = 8.5, p = .009. Adding item errors for Morse did not improve the model's predictive power (see Table 2), corrected R2 = .35, p = .022. This finding indicates that although item memory for Morse is poorer than for speech, individual differences in item memory reflect an underlying factor that is common to Morse and speech short-term memory, and this underlying factor contributes to Morse comprehension.

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear regression for Morse comprehension using Speech item and Morse Item short-term memory as predictors.

| Predictor | B | SE b | β | t value | sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | .92 | .04 | 21.91 | .000* | |

| Speech item errors | −.76 | .26 | −.55 | −.28 | .009* |

| Excluded variables |

|

|

|

|

|

| β in | t | sig | |||

|

Morse Item Errors |

−.37 |

−1.02 |

.32 |

|

|

Note. R2 = .31 corrected R_corr 2 = .27; B = unstandardized coefficient; SE b = standard error of the coefficient; β = standardized coefficient.

p < .05.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated individual differences in perceptual fluency, comprehension, and short-term memory for Morse stimuli. We find strong evidence that differences in Morse short-term memory predict differences in Morse comprehension, above and beyond any contributions from differences in perceptual fluency. Further, we find that short-term memory is poorer for Morse as compared to speech, and this difference is primarily explained by poorer item memory for Morse. Finally, we find that individual differences in Morse short-term memory are predictive of differences in Morse comprehension, and that even more specifically, item errors in serial recall predict poorer comprehension. Interestingly, item errors for speech sufficiently account for enough of the variability that item memory for Morse does not add any additional predictive power. Below, we draw upon parallels to the reading literature concluding that Morse functions like “reading for the ears” and we explain how a psycholinguistic framework can account for the observed relationships between short-term memory (for Morse and speech lists) and Morse comprehension. We end by considering the implications of our results for understanding individual differences in the comprehension of distorted speech and listening strategies that impact learning from experience.

The Relationship Between Short-Term Memory and Morse Comprehension

Our findings are consistent with decades of research showing that measures of verbal short-term memory are highly predictive of differences in written comprehension (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993; Just & Carpenter, 1992). Since Morse code is based on a 1:1 mapping between a perceptual input and a particular letter of the Roman alphabet, like the written alphabet it provides for largely consistent mappings between perceptual inputs and corresponding phonological and semantic knowledge of spoken English. Thus, it should not be suprising that we find a reading-like relationship between individual differences in Morse short-term memory and Morse comprehension.

While our participants varied in their Morse short-term memory, in general their short-term memory for Morse lists was poorer than for speech lists. To investigate the underlying sources of this difference, we analyzed aspects of short-term memory associated with three different speech-language abilities: recency and suffix effects as a marker of echoic memory, order errors as a marker of phonological-articulatory coding, and item errors as a marker of lexical-semantic support for items maintained in a phonological store. We observed large and highly significant differences only for the rate of item errors for Morse as compared to speech lists. Our observed dissociation between order and item error effects is consistent with neural evidence associating item errors in short-term memory with a ventral semantic processing pathway and order errors with a brain network for attention and exectuve control (Majerus, 2013).

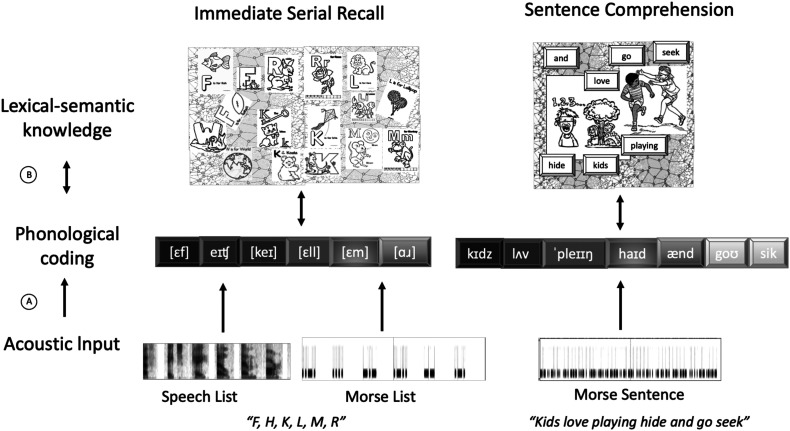

Psycholinguistic perspectives on short-term memory have explained differences in item errors as the natural outcome of a highly interactive speech-language network (Figure 4 schematically illustrates this perspective as applied to the current study). In these perspectives, active representations within a phonological store associated with speech planning are interconnected with lexical-semantic representations stored in long-term memory (for review, see Acheson & MacDonald, 2009). Those items with stronger lexical-semantic representation are better protected from loss or degradation within the phonological store, resulting in better recall of the items (Jefferies et al., 2006a, 2006b; Lewandowsky & Farrell, 2000). This leads us to infer that Morse lists experience weaker support from lexical-semantic knowledge, causing poorer item memory and hence poorer overall recall of Morse as compared to speech lists.

Figure 4.

Psycholinguistic perspective on commonalities between Morse and Speech. Both the Immediate Serial Recall (ISR) task and Sentence Comprehension tasks involve acoustic input that can be phonologically coded and mapped onto long-term lexical semantic knowledge (left panel), with perceptual fluency (A) reflecting the strength of acoustic mapping onto the phonological level, and lexical-semantic integration providing support, and (B) to maintain phonologically coded items in short-term memory. Phonological coding is conceptually depicted as something akin to a set of phono-lexical representations in a high level speech plan, with an activation gradient that declines across successive positions. Echoic memory is not depicted, but would be represented as the acoustic trace of the most recently heard item. In the ISR task (middle panel), the acoustic input arrives as a sequence of letters which maps onto learned letter-name and lexical long-term knowledge about English letters. This provides lexical-semantic support for item memory. Comprehension (right panel) rests on successful phonological coding and activation of long-term lexical knowledge as well. Across the participant sample tested, overall integration is weaker for Morse than Speech accounting for differences in item memory across conditions. However, individual differences lexical-semantic integration (B) would similarly affect both ISR and sentence comprehension performance, and thus, account for correlations between these two tasks.

Because psycholinguistic perspectives on short-term memory posit that immediate serial recall is parasitic on the speech-language network, factors attributed to this network should influence both short-term memory and comprehension (as depicted in Figure 4). Our results provide support for this general prediction. Specifically, we find that individual differences in item memory for Speech lists similarly predict individual differences in Morse comprehension, despite the overall poorer item memory observed for Morse lists. This somewhat counterintuitive pattern of results fits easily with two related ideas. The first is that the integration of phonological and lexical-semantic knowledge is weaker for Morse as compared to speech, which is to be expected given that individuals have vastly more experience listening to and comprehending speech as compared to Morse. In this way, Morse once again seems to function like “reading for the ears,” as reading experience is thought to build the integration of orthographic, phonological, and semantic knowledge that is a hallmark of skilled reading comprehension (Perfetti & Hart, 2002). The second idea is that individuals vary in the strength of their integration of phonological and lexical-semantic knowledge, but do so similarly for Morse and speech. This makes sense if Morse and speech stimuli for the same concept map onto the same lexical-level knowledge, as would be expected given that Morse (like printed English) symbolically represents spoken English. Therefore, those individuals with the strongest lexical-semantic integration should exhibit stronger item memory across perceptual differences in input.

Implications for Auditory Comprehension of Distorted Speech

Our results also provide a new perspective on auditory comprehension of degraded speech input. They are strikingly similar to results found by Frankish (2008), who compared the immediate serial recall of lists with distorted (less intelligible) versus nondistorted (intelligible) spoken letters as stimuli. Frankish found that the rate of item errors was higher for the distorted as compared to nondistorted list condition, but that order errors showed no difference between distorted and nondistorted spoken letters. Frankish attributed his results to differences in echoic storage, because the differences in item recall were greatest at the final position. Our data are not as easily interpreted as arising from an echoic store, as individual differences in item memory predicted Morse comprehension even under under suffix conditions that should minimize echoic storage. Instead, we suggest that differences in lexical-semantic support better explain our results. Differences in lexical-semantic support may also help to explain the Frankish (2008) results. Unintelligible (distorted) speech stimuli (like those used by Frankish) create uncertainty in mapping the acoustic input onto phonological and lexical-semantic knowledge in long-term memory. As a result, this weakens lexical-semantic integration and so less intelligible stimuli are more likely to be forgotten in short-term memory—the core result from the Frankish study.

One important distinction between this study and Frankish (2008) is that our study used auditory stimuli that were acoustically clear and accurately perceived by all participants, and yet we observed individual differences in comprehension and short-term item memory. This underscores the well-established point that differences in the quality or variability of the acoustic input do not solely explain differences in short-term memory and comprehension of speech items. For instance, individuals with cochlear implants show tremendous individual differences in word recognition ability (Koeritzer et al., 2018; Moberly et al., 2017; Nagaraj, 2017; Pisoni, Broadstock, et al., 2018) that are poorly predicted by the quality of the acoustic output provided by the implant (Battmer et al., 2009; Pisoni, Kronenberger, et al., 2018). Similar to our findings for Morse, these differences in comprehension are correlated with individual differences in short-term memory, and not simply explained by listening experience (in this case, amount of elapsed time since the implant surgery). Interestingly, one of the many likely factors that does seem to be important is the nature of listening experiences with the cochlear implant (Houston & Bergeson, 2014; Wang et al., 2018). For instance, infants with cochlear implants show individual differences in attentional orienting to speech input, which may account for individual differences in speech and linguistic development that have been associated with differences in lexical-semantic abilities (AuBuchon et al., 2015; Pisoni, Broadstock, et al., 2018). Further evidence that attention has an impact on listening comes from studies of adults with typical hearing (e.g., Kraljic et al., 2008).

Putting these ideas together, we suggest that while there are many sources of individual differences in speech comprehension, differences in lexical-semantic integration may be an explanatory mechanism that is relevant for seemingly different areas of speech research. Applying this idea to our study, many of the participants with the strongest comprehension of Morse reported using it on a regular basis to communicate with ham radio operators around the world, and began doing so at a relatively early age. Potentially, the nature of this listening experience may have fostered the mapping of Morse onto lexical-semantic knowledge, as well as the integration of phonological and lexical-semantic knowledge for both Morse and speech, which would in turn support maintenance of item information in short-term memory. Collectively, these results point to the value of further research on how different listening experiences impact short-term memory and comprehension outcomes (AuBuchon et al., 2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH Grant RO1-MH59256 (JAF). Sara Guediche, now at BCBL, is supported by funding from European Union's Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant agreement No-79954, the Basque Government through the Basque Excellence Research Centers 2018-2021 program, and the Spanish State Agency Severo Ochoa excellence accreditation SEV-2015-0490 (awarded to the BCBL). Thanks to Marina Kalashnikova and members of the Spoken Language Interest Group for helpful discussions. The authors thank Maryam Khatami, Jody Manners, Corrine Durisko, and Tanisha Hill-Jarrett for assisting with project. We also thank ham radio community, especially Paul Jacobs.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIMH Grant RO1-MH59256 (JAF). Sara Guediche, now at BCBL, is supported by funding from European Union's Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant agreement No-79954, the Basque Government through the Basque Excellence Research Centers 2018-2021 program, and the Spanish State Agency Severo Ochoa excellence accreditation SEV-2015-0490 (awarded to the BCBL).

Footnotes

In line with the predominant practice in speech sciences, we refer to performance on the immediate serial recall task as a measure of short-term memory. However, ordered serial recall likely involves additional cognitive and attentional processes such as those involved in intentional rehearsal, and not just passive storage. Historically, this led Baddeley and colleagues to consider forward and backward immediate serial recall tasks as measures of working memory (Baddeley, 1986).

Family: binomial (logit), Formula: Acc ~ Type × Suffix + (1 + Suffix|Participant)

References

- Acheson, D. J. , & MacDonald, M. C. (2009). Verbal working memory and language production: Common approaches to the serial ordering of verbal information. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AuBuchon, A. M. , Pisoni, D. B. , & Kronenberger, W. G. (2015). Short-term and working memory impairments in early-implanted, long-term cochlear implant users are independent of audibility and speech production. Ear and Hearing, 36(6), 733–737. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Oxford psychology series, No. 11. Working memory . Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battmer, R. D. , Linz, B. , & Lenarz, T. (2009). A review of device failure in more than 23 years of clinical experience of a cochlear implant program with more than 3,400 implantees. Otology & Neurotology, 30(4), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e31819e6206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehudah, G. , & Fiez, J. A. (2007). Development of verbal working memory. In D. Coch, K. W. Fisher, & G. Dawson (Eds.), Human behavior, learning, and the developing brain: Typical development (pp. 301–328). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coe, L. (2003). The telegraph: A history of Morse code's invention and its predecessors in the United States. McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, R. G. (1978). Mechanisms of auditory backward masking in the stimulus suffix effect. Psychological Review, 85(6), 502–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.85.6.502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, R. G. , & Morton, J. (1969). Precategorical acoustic storage (PAS). Perception & Psychophysics, 5(6), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03210660 [Google Scholar]

- Eimas, P. D. , Cooper, W. E. , & Corbit, J. D. (1973). Some properties of linguistic feature detectors. Perception & Psychophysics, 13(2), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03214135 [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey, K. , Giezen, M. R. , Petrich, J. A. , Spurgeon, E. , & O'Grady Farnady, L. (2017). The relation between working memory and language comprehension in signers and speakers. Acta Psychologica, 177, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2017.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahie, J. J. (1884). A history of electric telegraphy, to the year 1837. E. & F. N. Spon. [Google Scholar]

- Frankish, C. (1996). Auditory short-term memory and the perception of speech. In Gathercole S. E. (Ed.), Models of short-term memory (pp. 179–207). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frankish, C. (2008). Precategorical acoustic storage and the perception of speech. Journal of Memory and Language, 58(3), 815–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.06.003 [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, S. E. (1999). Cognitive approaches to the development of short-term memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(11), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01388-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, S. E. , & Baddeley, A. D. (1993). Essays in cognitive psychology. Working memory and language. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, R. L. , & Samuel, A. G. (1986). Recency and suffix effects in serial recall of musical stimuli. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.12.4.517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, F. G. (1949). The genesis and speed of the telegraph codes. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 93(5), 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D. M. , & Bergeson, T. R. (2014). Hearing versus listening: Attention to speech and its role in language acquisition in deaf infants with cochlear implants. Lingua, 139, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, C. , Roodenrys, S. , Schweickert, R. , Brown, G. D. , Martin, S. , & Stuart, G. (1997). Word-frequency effects on short-term memory tasks: Evidence for a redintegration process in immediate serial recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23(5), 1217–1232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.23.5.1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, E. , Frankish, C. R. , & Lambon-Ralph, M. A. (2006a). Lexical and semantic binding in verbal short-term memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 54, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2005.08.001 [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, E. , Frankish, C. R. , & Lambon-Ralph, M. A. (2006b). Lexical and semantic influences on item and order memory in immediate serial recognition: Evidence from a novel task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59(5), 949–964. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980543000141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, E. , Frankish, C. , & Noble, K. (2009). Lexical coherence in short-term memory: Strategic reconstruction or “semantic glue.” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(10), 1967–1982. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210802697672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. M. , Macken, W. J. , & Nicholls, A. P. (2004). The phonological store of working memory: Is it phonological and is it a store? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 30(3), 656–674. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.30.3.656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just, M. A. , & Carpenter, P. A. (1992). A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review, 99(1), 122–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klem, M. , Melby-Lervåg, M. , Hagtvet, B. , Lyster, S. A. H. , Gustafsson, J. E. , & Hulme, C. (2015). Sentence repetition is a measure of children's language skills rather than working memory limitations. Developmental Science, 18(1), 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeritzer, M. A. , Rogers, C. S. , Van Engen, K. J. , & Peelle, J. E. (2018). The impact of age, background noise, semantic ambiguity, and hearing loss on recognition memory for spoken sentences. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(3), 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-H-17-0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraljic, T. , Samuel, A. G. , & Brennan, S. E. (2008). First impressions and last resorts: How listeners adjust to speaker variability. Psychological Science, 19(4), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S. , & Farrell, S. (2000). A redintegration account of the effects of speech rate, lexicality, and word frequency in immediate serial recall. Psychological Research, 63(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00008175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, A. M. , Cooper, F. S. , Shankweiler, D. P. , & Studdert-Kennedy, M. (1967). Perception of the speech code. Psychological Review, 74(6), 431–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0020279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinis, T. , Armon-Lotem, S. , & Pontikas, G. (2017). Language impairment in bilingual children. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(3–4), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.00001.mar [Google Scholar]

- Maier, J. , Hartvig, N. V. , Green, A. C. , & Stodkilde-Jorgensen, H. (2004). Reading with the ears. Neuroscience Letters, 364(3), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2004.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerus, S. (2013). Language repetition and short-term memory: An integrative framework. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, R. A. , & Warrington, E. K. (1987). The double dissociation of short-term memory for lists and sentences: Evidence from aphasia. Brain, 110(6), 1545–1563. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/110.6.1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G. A. , & Isard, S. (1963). Some perceptual consequences of linguistic rules. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 2(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(63)80087-0 [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. M. , & Roodenrys, S. (2009). The interaction of word frequency and concreteness in immediate serial recall. Memory & Cognition, 37(6), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.37.6.850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberly, A. C. , Pisoni, D. B. , & Harris, M. S. (2017). Visual working memory span in adults with cochlear implants: Some preliminary findings. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 3(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj, N. K. (2017). Working memory and speech comprehension in older adults with hearing impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(10), 2949–2964. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-H-17-0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. P. , & Norris, D. (1998). The primacy model: A new model of immediate serial recall. Psychological Review, 105(4), 761–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.105.4.761-781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti, C. A. , & Hart, L. (2002). The lexical quality hypothesis. Precursors of Functional Literacy, 11, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni, D. B. , Broadstock, A. , Wucinich, T. , Safdar, N. , Miller, K. , Hernandez, L. R. , Vasil, K. , Boyce, L. , Davies, A. , Harris, M. S. , Castellanos, I. , Xu, H. , Kronenberger, W. G. , & Moberly, A. C. (2018). Verbal learning and memory after cochlear implantation in postlingually deaf adults: Some new findings with the CVLT-II. Ear and Hearing, 39(4), 720–745. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni, D. B. , Kronenberger, W. G. , Harris, M. S. , & Moberly, A. C. (2018). Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 3(4), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wjorl.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, M. , & Saint-Aubin, J. (1996). Immediate serial recall, word frequency, item identity and item position. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale, 50(4), 408–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/1196-1961.50.4.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. C. , & Lombardi, L. (1990). Regeneration in the short-term recall of sentences. Journal of Memory and Language, 29(6), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(90)90042-X [Google Scholar]

- Potter, M. C. (2012). Conceptual short term memory in perception and thought. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 113. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Aubin, J. , & Poirier, M. (1999). The influence of long-term memory factors on immediate serial recall: An item and order analysis. International Journal of Psychology, 34(5–6), 347–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075999399675 [Google Scholar]

- Savill, N. , Ellis, R. , Brooke, E. , Koa, T. , Ferguson, S. , Rojas-Rodriguez, E. , Arnold, D. , Smallwood, J. , & Jefferies, E. (2018). Keeping it together: Semantic coherence stabilizes phonological sequences in short-term memory. Memory & Cognition, 46(3), 426–437. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-017-0775-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, P. T. , Roodenrys, S. , & Miller, L. M. (2017). Serial reconstruction of order and serial recall in verbal short-term memory. Memory & Cognition, 45(7), 1126–1143. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-017-0719-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, C. H. (2008). Military communications: From ancient times to the 21st century. ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou, E. , Kambanaros, M. , & Grohmann, K. K. (2017). Sentence repetition as a tool for screening morphosyntactic abilities of bilectal children with SLI. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, L. (1853). The electro magnetic telegraph: With an historical account of its rise, progress, and present condition. A. Hart. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Shafto, C. L. , & Houston, D. M. (2018). Attention to speech and spoken language development in deaf children with cochlear implants: A 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Science, 21(6), e12677. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziethe, A. , Eysholdt, U. , & Doellinger, M. (2013). Sentence repetition and digit span: Potential markers of bilingual children with suspected SLI. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 38(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3109/14015439.2012.664652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.