Abstract

Practical relevance:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common form of feline cardiomyopathy observed clinically and may affect up to approximately 15% of the domestic cat population, primarily as a subclinical disease. Fortunately, severe HCM, leading to heart failure or arterial thromboembolism (ATE), only occurs in a small proportion of these cats.

Patient group:

Domestic cats of any age from 3 months upward, of either sex and of any breed, can be affected. A higher prevalence in male and domestic shorthair cats has been reported.

Diagnostics:

Subclinical feline HCM may or may not produce a heart murmur or gallop sound. Substantial left atrial enlargement can often be identified radiographically in cats with severe HCM. Biomarkers should not be relied on solely to diagnose the disease. While severe feline HCM can usually be diagnosed via echocardiography alone, feline HCM with mild to moderate left ventricular (LV) wall thickening is a diagnosis of exclusion, which means there is no definitive test for HCM in these cats and so other disorders that can cause mild to moderate LV wall thickening (eg, hyperthyroidism, systemic hypertension, acromegaly, dehydration) need to be ruled out.

Key findings:

While a genetic cause of HCM has been identified in two breeds and is suspected in another, for most cats the cause is unknown. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM) is the most common cause of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (DLVOTO) and, in turn, the most common cause of a heart murmur with feline HCM. While severe DLVOTO is probably clinically significant and so should be treated, lesser degrees probably are not. Furthermore, since SAM can likely be induced in most cats with HCM, the distinction between HCM without obstruction and HCM with obstruction (HOCM) is of limited importance in cats. Diastolic dysfunction, and its consequences of abnormally increased atrial pressure leading to signs of heart failure, and sluggish atrial blood flow leading to ATE, is the primary abnormality that causes clinical signs and death in affected cats. Treatment (eg, loop diuretics) is aimed at controlling heart failure. Preventive treatment (eg, antithrombotic drugs) is aimed at reducing the risk of complications (eg, ATE).

Conclusions:

Most cats with HCM show no overt clinical signs and live a normal or near-normal life despite this disease. However, a substantial minority of cats develop overt clinical signs referable to heart failure or ATE that require treatment. For most cats with clinical signs caused by HCM, the long-term prognosis is poor to grave despite therapy.

Areas of uncertainty:

Genetic mutations (variants) that cause HCM have been identified in a few breeds, but, despite valiant efforts, the cause of HCM in the vast majority of cats remains unknown. No treatment currently exists that reverses or even slows the cardiomyopathic process in HCM, again despite valiant efforts. The search goes on.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathies, myocardial diseases, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, gene mutation, systolic anterior motion, mitral valve, echocardiography

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is defined as concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH; thickened left ventricular [LV] wall) in the absence of another cardiac or systemic disease capable of producing the magnitude of hypertrophy evident (Figure 1).1,2 The LV chamber in diastole is normal in some cats and is small in some others. Affected cats can present with signs of heart failure or arterial thrombo embolism (ATE). Some die suddenly. However, like humans with HCM, many cats never exhibit any clinical signs of cardiac disease (ie, have subclinical disease) and live a normal lifespan.3–6

Figure 1.

Gross pathologic specimen of a heart showing markedly thickened left ventricular walls and papillary muscles and an enlarged left atrium. At the upper left there is a thrombus in the left auricle (white asterisk). Another thrombus is present in the body of the left atrium on the right (black asterisk). S = interventricular septum; F = left ventricular free wall; P = base of the papillary muscles; A = body of the left atrium

In cats, the cause of HCM is unknown except in Maine Coons and Ragdolls, where a causative mutation has been identified (see below). 7 Consequently, HCM is a diagnosis of exclusion in most cats. other common causes of LVH that may need to be excluded include aortic stenosis, dehydration, systemic hypertension, hyperthyroidism and acromegaly. However, there are caveats. Systemic hypertension and hyperthyroidism do not cause severe LVH, so if a cat has severe LVH (arbitrarily defined as diastolic LV wall thickness ≥7 mm) and systemic hypertension or hyper-thyroidism, it can generally be assumed that these systemic disorders are not the sole cause of the LVH. Instead, it is likely that hyperthy-roidism (and probably also systemic hypertension) exacerbates the LVH seen with HCM, since it is known that successful treatment of hyperthyroidism results in a decrease in LVH.8,9

Therefore, if an older cat has severe LVH, hyper-thyroidism and systemic hypertension still need to be ruled out as complicating factors but are probably not the only disease process affecting the heart. Hyperthyroidism, acromegaly and systemic hypertension are rare in younger cats. Aortic stenosis is rare in any cat. 10

obviously, if a cat has hyperthyroidism, it should be treated appropriately and if it has systemic hypertension it should be treated with amlodipine or telmisartan.11–13 The hope is that successful treatment will result in a reduction in LV wall thickness and in clinical improvement, if heart failure is present.

Pathophysiology

When the LV wall is severely thickened, myocardial blood supply is compromised. 14 This results in ongoing myocyte damage and death, as evidenced by an elevation in cardiac troponin I (cTn I) in cats with HCM.15,16 Cardiomyocytes that die are replaced with fibrous tissue (replacement fibrosis), as evidenced by increased concentrations of circulating biomarkers of type I collagen. 17 In humans, myocardial fibrosis is most commonly identified and quantified non-invasively using MRI and a contrast agent (gadolini-um). 18 The first attempt to use this modality to identify myocardial fibrosis in cats with HCM failed. 19 A more recent study that utilized gadolinium to calculate extracellular volume fraction, an indirect measure of myocardial fibrosis, showed that cats with HCM had an increase in this variable, presumably due to myocardial fibrosis. 20 This presumption was strengthened by the fact that this variable correlated well with echocardiographic measures of diastolic dysfunction.

While thick fibrous myocardium contracts normally in systole due to the decrease in afterload (systolic myocardial wall stress) brought about by the thick LV wall, it does not relax normally in diastole. So, a common functional abnormality seen with HCM is diastolic dysfunction, which means the LV is stiff and so for any given blood volume that flows into the LV chamber in diastole, the diastolic pressure in the LV chamber is increased. 21 Since the mitral valve is open in diastole, whatever pressure is present in the LV in diastole is also present in the left atrium (LA). As a result, an increase in LV diastolic pressure causes an increase in LA pressure. An increase in LA pressure results in LA enlargement. This means in cats with HCM that have clinically significant diastolic dysfunction, the LA is enlarged. In general, the higher the pressure, the greater the enlargement. The increased LA pressure also results in increased pulmonary venous pressure, and therefore enlargement of the pulmonary veins, and in increased pulmonary capillary pressure, which causes pulmonary edema (PE). 22 The veins that drain the pleura that lie on the surface of the lungs (visceral pleural veins) drain into pulmonary veins, so an increase in LA and pulmonary venous pressure is also assumed to cause pleural effusion (PLE) in cats.23,24 This is what is referred to as left heart failure (see Part 1).

While cats with the commonly classified left-sided cardiomyopathies (HCM, dilated cardiomyopathy [DCM] and restrictive cardiomyopathy [RCM]) also frequently have right heart disease, in the authors’ opinion this is usually not severe enough to cause right heart failure, which can also cause PLE in cats.25–27 Additionally, while pulmonary hypertension secondary to left heart failure could theoretically cause severe enough right heart disease to lead to right heart failure, as is well recognized in dogs, pulmonary hypertension in cats in left heart failure due to a cardiomyopathy is uncommon and, when present, is usually not severe. 28

Etiology

In most humans, and in most Maine Coon, Ragdoll and probably Sphynx cats, HCM is caused by a gene mutation (variant).29,30 Most commonly in humans and in Maine Coon and Ragdoll cats (and one domestic shorthair cat), HCM is caused by a mutation in a gene that encodes for a protein that contributes to the formation of the sarcomere (the contractile element that includes myosin, actin, etc).7,31 While sarcomeric gene mutations most commonly cause HCM in humans, it should be noted that they can also cause DCM or RCM, as well as left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC; see Part 3). 32 In HCM, the gene mutation causes the sarcomere to contract either less than normally or more than normally. 32 In cats with HCM, the sarcomere is more responsive to calcium than normal, so the myocardium is hypercontractile. 33 However, the exact pathophysiologic mechanism of how this sarcomeric dysfunction causes the LV wall to grow thicker remains to be elucidated.

In Maine Coon and Ragdoll cats the cause of HCM in most cases is a mutation in the myosin binding protein C gene. 29 In Maine Coon cats, the A31P (c.91G>C; p.A31P) mutation creates an abnormal protein that is incorporated into the sarcomere, where it causes sarcomeric dysfunction (acting as a poison polypeptide). 34 When the A31P mutation is transferred into fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), numerous abnormalities are produced including downregulation of small nucleolar RNAs (a class of small RNA molecules that primarily guide chemical modifications of other RNAs) and the unfolded protein response. 35

Maine Coon cats heterozygous for this mutation develop subtle systolic and diastolic dysfunction but usually do not develop wall thickening and so are subclinical.36,37 Those that are homozygous for the mutation commonly develop various degrees of wall thickening (HCM), some severe enough to result in severe LA enlargement and hence left heart failure or ATE.38,39 This pattern suggests an incomplete dominance mode of inheritance. 40 In humans, HCM is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern but occasionally other modes of inheritance are also found. 41 Prevalence of the A31P mutation in Maine Coon cats ranges from 34% to 41%.42–44 Approximately 10% of the cats with the A31P mutation are homozygous (at risk for developing clinically significant HCM) and 90% are heterozygous for the mutation. A small percentage of Maine Coon cats with HCM do not have the A31P mutation and so there must be at least one more cause in this breed. Recently, a second mutation in cardiac troponin T was identified in one Maine Coon cat with HCM. 45

The natural history and pathophysiology of the R820W (c.2460C >T; p.R820W) myosin binding protein C mutation in Ragdoll cats has not been as well studied but the pattern appears to be similar to that seen in Maine Coon cats. 40 The same R820W mutation seen in Ragdoll cats causes both HCM and LVNC in humans. 46 Ragdoll cats that are homozygous for the R820W mutation have a thicker LV wall than those that are heterozygous for the mutation and the wall thickness of cats heterozygous for the mutation is thicker than it is in cats without the mutation. 47 In the UK, 27.4% of Ragdoll cats sampled in one study had the mutation (26% heterozygous, 1.4% homozygous). 42

In Sphynx cats with HCM, a mutation in the Alstrom syndrome 1 (ALMS1) gene has been identified. 48 Mutations in the ALMS1 gene are associated with the development of Alstrom syndrome in humans, a multisystem familial disease that can include retinal degeneration, obesity, neurosensorial deafness, type 2 diabetes, and DCM and RCM. 49 The variant identified in Sphynx cats has not been identified in humans and none of the cats studied had signs of Alstrom syndrome. Of the 71 Sphynx cats with HCM examined in this study, 62 had this variant (27 heterozygotes and 35 homozygotes), so not all affected cats had the variant and no Sphynx cats without HCM were examined for this variant. 48 Consequently, it has not been proven that this variant is responsible for HCM in this breed. However, this G/C mutation does change a highly conserved glycine to alanine and was predicted to be deleterious (cause disease) by three computer programs designed to analyze this probability.

In humans, in addition to the type of mutation present, the type of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene also influences how thick the LV wall becomes in patients with myosin binding protein C mutations. 50 Patients homozygous for a deletion polymorphism (D/D) have a lower circulating concentration of ACE, more severe LVH, faster disease progression and more sudden death. Similarly, Ragdoll cats homozygous for a feline ACE polymorphism have a thicker LV wall than those that either do not have the polymorphism or are heterozygous for the polymorphism. 47

HCM is prevalent in several other purebred cat breeds and so is likely to be heritable in them as well. These include, but are not limited to, Bengal, American Shorthair, British Shorthair, Persian and Siberian cats.51–55 One family of domestic shorthair cats with HCM has also been described. 56 While Norwegian Forest Cats have characteristics of HCM, including mild wall thickening, myocyte hypertrophy, myofiber disarray and interstitial fibrosis, they also have endomyocardial fibrosis, a form of RCM, as another component of their disease (see Part 3). 57

It is suspected that other cat breeds have a genetic cause of their HCM, but intensive efforts aimed at identifying such mutations have not been successful.52,58 Consequently, and since mixed-breed cats with no family history of cardiomyopathy most commonly develop HCM, it is likely there is some other unknown cause of feline HCM.

Supplementary file 1 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle from a cat with presumed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, at presentation. The left ventricular walls are markedly thickened

Supplementary file 2 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle of the same cat as in supplementary file 1 (presumed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), 5 months after presentation. There is partial resolution of the left ventricular wall thickening

Supplementary file 3 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle of the same cat as in supplementary files 1 and 2, 8 months after presentation. The left ventricle is normal. The diagnosis was transient myocardial thickening

Lymphoma is a rare cause of an increase in LV wall thickness (Figure 2). 65 Chemotherapy can result in resolution of the thickening.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional view of a gross pathologic specimen of a heart from a cat with lymphoma (pale areas) that invaded the left ventricular myocardium

Dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM) causing dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (DLVOTO) is common in cats with HCM. 66 SAM is due to the hypertrophied and cranially displaced papillary muscles pulling a part of the septal (anterior) leaflet of the mitral valve into a normal or narrowed left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) (Figures 3 and 4; and supplementary files 4–7).67,68 Once that portion of the leaflet is in the LVOT, blood flowing from the apex of the LV into the LVOT pushes the tip farther toward the septum, usually (but not always) to the point where at least part of the leaflet contacts the base of the interventricular septum. This results in DLVOTO, a form of subaortic stenosis that progressively worsens throughout systole (Figure 5). When the mitral valve leaflet is distorted by SAM, mitral regurgitation also occurs. This produces a characteristic bilobed jet on color flow Doppler, with simultaneous systolic turbulence in the ascending aorta and LA (supplementary file 8).

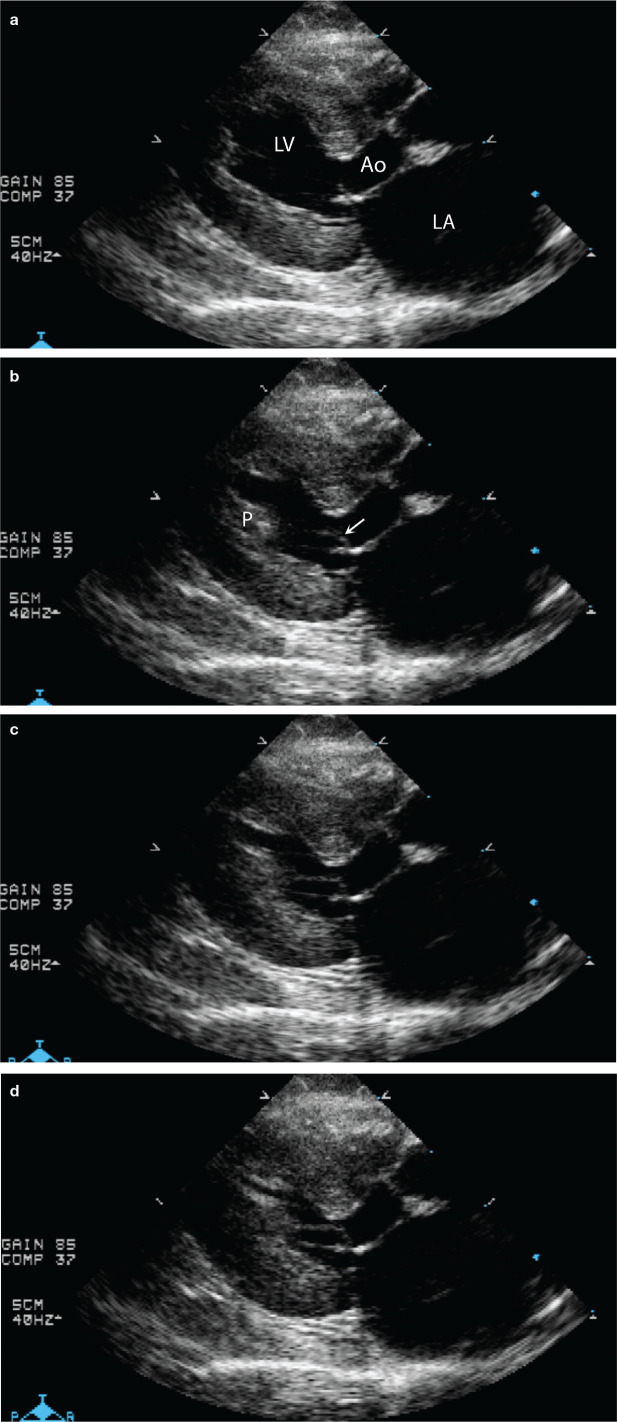

Figure 3.

Sequential echocardiographic frames that demonstrate systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM). (a) Early systole. The mitral valve is closed. The left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) is to the right of the LV label. A small section of the septal (anterior) leaflet of the mitral valve is being pulled into the LVOT by the papillary muscle at the apex of the ventricle. A chorda tendinea connecting the two is barely visible. (b) Mid-systole. The arrow points at the section of the septal leaflet of the mitral valve that is being simultaneously pulled into the LVOT by the papillary muscle (P) and pushed into the LVOT by blood flow that comes up underneath that section of leaflet tip. (c) Late systole. The tip of the mitral valve leaflet and its associated chorda now have the appearance of a cane. The mitral valve tip is partially occluding the LVOT. (d) End-systole. The SAM is further occluding the LVOT. LV = left ventricular lumen; Ao = aorta; LA = left atrium

Figure 4.

M-mode echocardiogram from a cat with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM). The SAM label overlies the region of SAM. The MV (mitral valve) label lies within the opening of the MV in diastole. SAM is visible in all cardiac cycles except the one after the MV label

Figure 5.

Continuous wave Doppler trace from a cat with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM). The peak velocity is elevated due to the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction caused by the SAM. The trace is shaped like a scimitar (superimposed graphic on the far right side) and is due to the region of obstruction progressively worsening throughout systole, especially in late systole (late peaking)

Supplementary file 4 Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle of a cat with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, played at full speed (real time)

Supplementary file 5 Same video as in supplementary file 4 (right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle of a cat with systolic anterior motion [SAM] of the mitral valve due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), played at half speed

Supplementary file 6 Video showing a left apical echocardiographic view of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, played at half speed. There is also a bulge in the basilar interventricular septum that contributes to the dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Supplementary file 7 Same video as in supplementary file 6 (left apical echocardiographic view of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), also played at half speed, but with an arrow pointing to the large cranial papillary muscle that is pulling the tip of the septal mitral valve leaflet into the left ventricular outflow tract

Supplementary file 8 Video showing a right parasternal color flow Doppler echocardiographic view of the two turbulent jets commonly seen in a cat with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. The upper jet is due to dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and the lower one is due to mitral regurgitation

Less commonly the basilar portion of the interventricular septum, particularly when it is thicker than normal, either contributes to, or causes, DLVOTO (supplementary files 9–13). At end-systole the hypertrophied septum can contact the septal leaflet of the mitral valve (if SAM is also present) or chordae tendineae.

Supplementary file 9 Video of a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view showing the basilar interventricular septum bulging into the left ventricular outflow tract in systole, creating dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Uncommonly an obstruction in the middle of the LV occurs. 69 This happens when the papillary muscles or a papillary muscle and an LV wall squeeze together. SAM also may affect the chordae tendineae predominantly or exclusively. 66

SAM is the usual cause of a heart murmur in a cat with HCM. The murmur is often dynamic, which means it becomes louder when the cat is excited/stressed and softer when the cat relaxes. This occurs because physical or emotional stress increases the severity of SAM and of DLVOTO, in turn increasing the velocity of flow through the dynamic outflow tract obstruction. Stress is typically accompanied by an increase in heart rate in a cat, so it is often thought that an increase in heart rate worsens SAM. However, ivabradine, an agent that decreases heart rate without decreasing contractility, has little to no effect on SAM, which proves that heart rate is not involved.70 instead SAM worsens when contractility increases with stress (ie, catecholamine stimulation) and decreases when contractility is lessened with a beta blocker such as atenolol.

Cats with SAM often have a longer than normal septal mitral valve leaflet. 66 Rarely this is a congenitally malformed mitral valve, where the SAM is the primary problem and hypertrophy is a secondary abnormality. 71 While it has been speculated that a primary, congenital mitral valve abnormality may occur in conjunction with HCM and even predispose a cat to SAM, it seems unlikely to the authors that a cat would be born with both HCM and an abnormally formed mitral valve; it seems more plausible that the affected mitral valve leaflet remodels (grows longer) in response to being stretched by the SAM. 66 However, there is one study in humans where the anterior mitral valve leaflet was longer in young patients with an HCM-causing mutation and no hypertrophy. 72

Supplemental Material

Supplementary file 10 Still frame, of early systole, from the video in supplementary file 9 (right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view showing the basilar interventricular septum bulging into the left ventricular outflow tract in systole, creating dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction)

Supplementary file 11 Still frame, of mid- to late-systole, from the video in supplementary file 9 (right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view showing the basilar interventricular septum bulging into the left ventricular outflow tract in systole, creating dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction)

Supplementary file 12 Still frame, of end-systole, from the video in supplementary file 9 (right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view showing the basilar interventricular septum bulging into the left ventricular outflow tract in systole, creating dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction)

Supplementary file 13 Image of a continuous wave Doppler trace showing the late peaking signal due to dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Pathology

The diagnosis of feline HCM is, on occasion, reliant on a gross pathologic and possibly histopathologic examination; one example is in the context of unexplained sudden death. After death, myocardium contracts (undergoes rigor) irreversibly because energy (adenosine triphosphate [ATP]) is depleted so sarcomeres can no longer relax. Consequently, the LV walls of a gross pathology specimen from a normal cat frequently look thicker than expected. Therefore, the post-mortem diagnosis of HCM cannot rely on a cursory macroscopic examination of the LV. Instead, to make the diagnosis of HCM, the LV must be measurably grossly thickened, and the heart weight must be greater than normal. Generally, a normal cat heart weighs <20 g, but a heart from a cat with HCM weighs >20 g, sometimes substantially more so (as high as 38 g). 77 The normal heart weight to body weight ratio is in the range of 3-4 g/kg in cats. Those with HCM have an average ratio of 6.3 g/kg. 77

While histopathology can be used to reliably provide the diagnosis of HCM in humans, this is generally not the case in cats. 78 The classic findings in humans of cardiomyocyte disarray, cardiomyocyte enlargement and medial hypertrophy of the walls of small coronary arteries may be present in some, but not all, cats (Figure 6).79,80 In fact, evidence from two groups suggests that cats with HCM do not have cardiomyocyte hypertrophy or hyperplasia but instead have increased interstitium filled with fibrous tissue, macrophages or lymphocytes, small vessels and degenerate cardiomyocytes.79,81 However, a recent study by another group found cardiomyocyte disarray and fibrosis via histopathologic examination and micro-CT to be prevalent in cats with HCM. 82 In addition, the aforementioned study of Sphynx cats also found cardiomyocyte disarray. 48 It is almost as if there may be two forms of the disease in cats.

Figure 6.

Histopathologic image of left ventricular myocardium from a Maine Coon cat with HCM showing cardiomyocyte disarray: the longitudinal axes of the cardiomyocytes converge and diverge instead of coursing in parallel

In a recent study, RNA was extracted from feline hearts at necropsy and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. 83 In cats with HCM the transcription of remodeling enzymes (eg, matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -3 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3) prevailed, especially in male cats.

Prevalence

HCM is common in domestic cats. Studies have suggested that its prevalence could be as high as 15%.84–86 In purebred cats HCM is prevalent in young cats as subclinical disease. 87 In mixed-breed cats, clinically apparent HCM is more common in older animals, although young cats and even kittens are also represent-ed.4–6 ,56,84 This speaks to the marked heterogeneity of HCM and, as discussed in Part 1, raises the possibility that ‘HCM’ is in fact a collection of numerous subtypes of disease, all sharing the characteristic of some form of LV thickening but each with its own genetic mutation, epigenetic triggers or unknown cause, and each with its own evolution over time, ability to respond to treatment and prognosis. Retrospective case series consistently identify a male predominance, with male to female ratios typically around 3:1.4–6 ,84,88,89 This may reflect a true sex difference, or the aforementioned association with larger cats (eg, perhaps some normal large cats have sometimes met the echocardiographic criteria for HCM simply by being larger). 90 Alternatively, as in Maine Coon cats, the prevalence of the disease could be the same in males and females, but disease severity is often worse in males so there is a male predominance in cats with clinically apparent disease. 87

In clinic populations, mixed-breed cats with HCM predominate over purebred cats with HCM, likely a reflection of the larger population of mixed-breed cats. While there are some reports of families of mixed-breed cats with HCM,56,91 for the most part the disease shows up in cats with no family history of the disease. Of course, many of those cats have no family history because only rarely is the family lineage tracked or able to be tracked in mixed-breed cats.

Natural history

With HCM, LVH and the other associated changes develop over time. 87 In Maine Coon cats the HCM phenotype is never present at birth. While it can develop as early as 6 months of age, more commonly it becomes apparent for the first time at 2-3 years of age. In a few Maine Coon cats, the phenotypic changes of HCM show up for the first time at 6-7 years of age. 87 The natural history of HCM in mixed-breed cats is poorly documented. While it often appears as if such cats develop HCM at an older age, in the authors’ opinion it is more likely that they have had the disease for many years prior to presentation because HCM often is ‘silent’ (devoid of auscultatory abnormalities).84–86 Still, it is common, for example, for a cat that is >10 years old to have a heart murmur first detected at that age, and for that to lead to the echocardiographic diagnosis of HCM.

Some cats with HCM develop mild to moderate LVH and never progress to severe LVH, whereas others do. 87 In addition, while most cats that develop LA enlargement and left heart failure have severe LVH, some do not. However, most of those with severe LVH develop LA enlargement. A recent small study found that 90% of cats with both LA enlargement and an amino terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentration >700 pmol/l went on to develop heart failure, suffer from ATE or die suddenly within 7-60 months of diagnosis. 92 Just 30% of cats with only LA enlargement (including mild enlargement) went on to develop one of those events, while 40% with just an elevated NT-proBNP concentration developed the same sequelae. 92

LA enlargement is due to the development of a higher than normal LA pressure, which, as described earlier, is caused by LV diastolic dysfunction (stiff LV). Cats that develop moderate to severe LA enlargement (left atrial diameter to aortic root diameter ratio [LA:Ao] >1.8-2.0) are at risk for developing, or being in, left heart failure (PE and/ or PLE). 5 Exactly why a cat goes from the subclinical stage to severe LA enlargement to presenting in heart failure is unknown. It is presumed that dias-tolic dysfunction is the primary inciting factor. Diastolic function in other species deteriorates with age, so age may be a contributing factor in cats as well.93,94 LA function is decreased in cats with HCM. 95 This may be primary dysfunction due to atrial myocardial disease and/ or may arise secondarily to atrial disease caused by the enlargement. The enlargement plus the reduced function result in blood flow stasis (reduced blood flow velocity). This contributes to thrombus formation

Endocrine diseases such as hyperthyroidism and acromegaly can cause LVH and therefore would be expected to exacerbate the changes produced by existing HCM (see Part 3). Acute stress resulting in severe tachycardia (eg, a cat fight) can result in acute deterioration of diastolic function and so precipitate acute left heart failure (PE).6,96 Anesthesia, surgery, IV fluid therapy and possibly corticosteroid administration can tip a cat with subclinical disease over into heart failure.6,61,64,97 However, most cats with HCM that present in heart failure have no apparent exacerbating disease or precipitating event.

Rarely a cat with HCM will develop myocar-dial failure (decreased myocardial contractility). This is often termed end-stage HCM (supplementary file 14). 98 These cats invariably present in left heart failure. On an echocardiogram there is still evidence of LV wall thickening but with accompanying evidence of systolic dysfunction, including an increased LV end-systolic diameter and reduced LV fractional shortening. The pathophysiologic mechanism is not understood. Some cats may have distinct regional (rather than global) LV wall hypokinesis or akinesis, and this portion of the wall may be thinner than normal (atrophied). These are all characteristics of chronic myocardial infarction. It is unlikely that myocardial infarction is due to coronary atherosclerosis, like it is in humans. In the authors’ opinion, more likely it is due to coronary thromboembolic disease.

Supplementary file 14 Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view from a cat with end-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The left ventricular free wall is 7 mm thick and contracts poorly. The interventricular septum is not thick and contracts very poorly. Fractional shortening is 17%. The left atrium is severely enlarged

Diagnosis

The definitive diagnosis of HCM is almost always made using echocardiography, although since there are other diseases that cause LV wall thickening, it is often still a diagnosis of exclusion. Other imaging modalities, such as CT and MRI, are used in human medicine and will likely be used more frequently in veterinary medicine as conscious restraining devices become more commonly used, and as machine costs and imaging times decrease (or achieve real-time status so anesthesia is no longer required; supplementary file 15).99–103 Electrocardiography (ECG) can reveal changes in some cats with HCM but is not a reliable indicator of disease.104–108 Radiography cannot be used to distinguish HCM from the other cardiomyopathies but is valuable for identifying severe LA enlargement, primarily on ventrodorsal or dorsoven-tral views (left auricular bulge), PE and PLE.

Supplementary file 15 Video showing a real-time MRI of a heart from a cat with severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Blood is white and most evident in diastole. The right side of the heart is on the left. The scan starts at the base of the heart and ends at the apex. The filling defects in the left ventricle in diastole are large papillary muscles. Courtesy of Kristin Lavely, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (Cardiology)

Echocardiography

The echocardiography diagnosis of HCM is straightforward when the disease is severe. 109 Marked regional or global LV wall thickening, severely enlarged papillary muscles, SAM, end-systolic cavity obliteration and moderate to severe LA enlargement are hallmark findings. In the authors’ opinion, the majority, or all, of these can be identified by most veterinarians with echocardiographic training (Figure 7 and supplementary files 16–19). 110

Figure 7.

Echocardiographic images from cats with HCM. (a) Right parasternal long-axis view showing severe global thickening of the left ventricle (LV). (b) Right parasternal short-axis view from a different cat with severe global thickening of the LV. (c) Right parasternal short-axis view of the LV from a cat with severe thickening of the left ventricular free wall and a less thick interventricular septum. LA = left atrium

Supplementary file 16 Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of global left ventricular hypertrophy in a cat with severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. SAM = systolic anterior motion

Supplementary file 17 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of large and hyperechoic papillary muscles in the same cat as in supplementary file 16 (severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). LVH = left ventricular hypertrophy

Supplementary file 18 Video showing a left cranial echocardiographic view of the thick interventricular septum (top), left ventricular free wall and papillary muscle, and severely enlarged left atrium in the same cat as in supplementary files 16 and 17 (severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy)

Supplementary file 19 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the aorta (center) and the severely enlarged left atrium (LA) of the same cat as in supplementary files 16–18 (severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy). L Aur = left auricle

Moderately severe HCM is more challenging to diagnose and so requires a more skilled operator. But even skilled operators may not agree on the diagnosis in some cases, primarily because the diagnosis relies on measurements, and both intra- and interindividual variation commonly occurs with echocardiog-raphy. 111 Heterogeneity of LV wall thickness also makes echocardiographic assessment challenging. In its mildest form, HCM probably cannot be distinguished from normal without using specialized techniques. 112 Some cats have a normal LA, no SAM, large papillary muscles and an LV wall thickness that is borderline (Figure 8a). 113 These cats are placed in an equivocal category, 8 and may or may not progress to having an overt HCM phenotype (unmistakable LV hypertrophy ± LA enlargement) over time. End-systolic cavity obliteration is common with feline HCM (Figure 8b), but can be seen in some normal cats also.

Figure 8.

Right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic images from a cat with severe HCM showing hypertrophied and hyperechoic left ventricular papillary muscles in diastole (a) and at end-systole showing end-systolic cavity obliteration (b)

LV wall thickening

Patterns of LV wall thickening are recognized in both humans and cats with HCM. The most common phenotype in humans is asymmetric hypertrophy, with the interventricular septum being thicker than the LV free wall. 114 While this form is well recognized in cats, global (symmetric) hypertrophy is more common. Wall thickening confined to the LV apex is well described in humans but rarely recognized in cats, possibly because this area is more difficult to image and because papillary muscle hypertrophy is so common.115,116 A frequent echocardiographic finding in a cat is a bulge at the base of the interventricular septum (supplementary file 20). This bulge can be an isolated finding, with no other thickened areas of the LV, or can be seen in a cat with other regions of the LV that are also too thick. In humans it has been termed discrete upper septal thickening (DUST). 117 When this abnormality is identified in isolation, it is unknown if it is a type of HCM; is due to normal aging, as noted in some humans; or is idiopathic. 118 Many cats with a left basilar septal bulge do not progress to having other regions of the LV become too thick, which presents a diagnostic dilemma (slowly evolving HCM vs non-HCM aging change). This bulge may cause LV outflow tract narrowing and so contribute to the formation of SAM (supplementary file 21).

Supplementary file 20 Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view from a cat with a bulge of the basilar interventricular septum (IVS). DUST = discrete upper septal thickening

Supplementary file 21 Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the heart from a cat with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The interventricular septum, including the basilar part of the septum, is thicker than normal. The thickened basilar septum narrows the left ventricular outflow tract, making it easier for systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (SAM) to form

While it is attractive to divide HCM into specific patterns, in reality LV wall thickening can encompass most possible patterns, from extensive and diffuse to mild and segmental. Consequently, the entire LV should be carefully examined using multiple echocardiographic views to find the thickest diastolic region(s).84–86

Upper limits for normal LV diastolic wall thickness are commonly debated. Part of this debate revolves around the difficulty identifying normal cats within a population from which to establish normal limits. Mostly this stems from the fact that subclinical HCM is so prevalent in the general feline population. 84 This makes it impossible to be confident that a control population of normal cats does not contain cats with HCM. In general, however, most agree that almost all average-sized adult cats with an LV free wall and interventricular septal thickness <5 mm have no LVH and that any value ≥6 mm is too thick in almost all normal-sized cats.8,119 Obviously this leaves a gray zone between 5 and 6 mm. LV wall thickness does vary with body weight (by about 1 mm from 2 to 8 kg), so it is likely that anything thicker than 5 mm in smaller cats (2-3 kg) is too thick.90,120 It is debatable whether this cut-off should be greater than 6 mm in very large (>10 kg) domestic cats.

It should be noted that measurement of LV wall thickness in cats is not an exact science and so, even though numerical results for measurements often are displayed to within tenths of a millimeter (the thickness of a sheet of paper), the authors believe one should strive to round off to the nearest 0.5 mm. Even when highly skilled operators perform repeat echocardiographic examinations on cats with the knowledge they will be compared with their colleagues, LV wall thickness still varies by up to approximately 20%. 111 In a cat with regional variations in wall thickness, errors can be compounded.

As stated previously, HCM is frequently regional, which can mean only one area of the LV wall is thick or can mean one region is thicker than other thick areas. 121 Because of the potential for regional heterogeneity, the LV must be examined carefully using two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography. M-mode echocardiography cannot be used to screen the LV for regions of thickening, although it might be used to measure an already identified region of thickness. This is more easily accomplished using so-called anatomical (free-positioning) M-mode echocardiography, which is available on some ultrasound machines. However, in most situations the wall thickness should be measured on a diastolic 2D image.8,84–86 Generally, this measurement should include endocardial surfaces (eg, leading to trailing edge for the interventricular septum) and care should always be taken to exclude LV and right ventricular papillary muscles, regions of endocardial thickening, areas where false tendons insert and the pericardium.8,122

LA size and function

Assessment of LA size is important in any cat with a left-sided cardiomyopathy, including HCM, and is within reach of most veterinarians who have received training (Figure 9).110,123 A severely enlarged LA means either the cat is already in left heart failure or the cat is at high risk of developing left heart failure, since the LA pressure is inferred to be increased (LA enlargement as an expression of the cardiomyopathic process, in the absence of increased atrial pressure, is not a recognized entity). 124 A severely enlarged LA also places the cat at risk of blood flow stasis and, in turn, thrombus formation; this is most commonly in the left auricle and can lead to ATE.

Figure 9.

Right parasternal short-axis view of the aorta (Ao), body of the left atrium (LA) and left atrial appendge (LAA). The LA and LAA are severely enlarged

The measurement of LA:Ao is commonly used to assess LA size. 125 Although there are different methods (eg, measuring at end-systole vs end-diastole; using a right paraster-nal short-axis or long-axis view), most often LA size is measured when at its largest (visually or at the beginning of ventricular electrical diastole) in a right parasternal short-axis basilar view. When performed in this manner, the normal LA:Ao is <1.6 and when the value is >1.8-2.0 (depending on the study; median value = 2.2) or the LA diameter is >18-19 mm, the LA is enlarged enough to put the cat at risk for being in, or developing, heart failure and/ or ATE (stage B2).126,127 When viewing the LA from a right parasternal short-axis view, one should strive to have the left auricle in view to use as a landmark. If possible, pulmonary veins should be excluded from the image for a more accurate assessment.

The LA is a three-dimensional structure. When it enlarges, it usually does so globally and will look large in any view, but this is not always the case (as it is in humans), especially when it is not severely enlarged. 128 For example, a minority of cats will have predominant left auricular enlargement with lesser enlargement of the body of the LA, or subjectively the LA will look larger from a left apical view than from a right parasternal view. Consequently, the LA should be examined from both right parasternal and left apical views, when possible. The size of the LA from the left apical view is a subjective assessment, comparing it with the size of the right atrium, aorta and LV chamber.

The best way to deal with the reality of the LA being a three-dimensional structure is to measure LA volume rather than diameter. This conventionally is undertaken in humans with a biplane method using orthogonal planes and utilizing the modified Simpson’s method of discs in the ultrasound software package to calculate volume.126,128 Unfortunately, obtaining orthogonal planes of the LA in the cat is difficult and has only begun to be studied. One investigation has used a simplified method utilizing a single plane from both the right parasternal long-axis four-chamber view and the left apical four-chamber view to make a rough estimate of LA volume. 127 This method did not outperform linear measurements of LA size. In another study, LA ejection fraction in cats with HCM causing heart failure was significantly different from LA ejection fraction in cats with subclinical HCM. 126

Other measures of LA function are also altered in cats with heart failure due to HCM. Measures that are decreased include left auricular flow velocity and mitral A wave velocity.126,129

It stands to reason that the pulmonary veins are also enlarged in a cat in left heart failure, since high hydrostatic venous pressures are the hallmark of heart failure and veins distend easily. Echocardiographic measures of pulmonary vein diameter can be indexed to pulmonary artery or aortic diameter. Both indices of pulmonary vein size are increased in cats in heart failure. 22

As opposed to dogs, where the LA is not known to decrease in size with diuretic administration, LA and pulmonary vein sizes are lower in both normal cats and cats in heart failure following furosemide administration (eg, median LA:Ao = 2.3 in cats in heart failure and no furosemide administration vs median LA:Ao = 1.8 in cats treated with furosemide 12 h or less before the echocardiographic examination in one study).22,130 On occasion, this can confound the diagnosis of left heart failure in a cat.

Diastolic dysfunction

Diastolic dysfunction is a characteristic feature of HCM. Diastolic function is typically assessed in cats with HCM using tissue Doppler imaging (TDI). Most commonly a pulsed wave TDI gate is placed at the lateral mitral valve annulus to measure the velocity at which it moves in early diastole (E’ wave). 21 In cats with severe HCM, the E’ wave velocity is typically decreased (Figure 10). 131 Global TDI analysis of diastolic function can also be assessed with higher-end echo-cardiographic machines. While it is interesting to assess diastolic function in cats with HCM, it often provides little additional insight for most feline patients with HCM. However, with other forms of cardiomyopathy, such as RCM, it may be diagnostic (see Part 3).

Figure 10.

Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) of a normal cat and a cat with severe HCM. (a) A left apical four-chamber view is used for TDI echocardiography of the lateral mitral annulus. The white bars represent the position of the pulsed wave Doppler gate. Images (b) and (c) show TDI myocardial velocity of the lateral mitral annulus in a cat with severe HCM and a normal cat, depicted with different velocity scales. The normal cat (c) had a higher heart rate (HR; 220 beats per minute [bpm] vs 115 bpm in the cat with HCM) and fusion of the early (E’) and late (A’) diastolic waves to form an EA’ wave. Fusion of the E’ and A’ diastolic waves does not affect the peak velocity in normal cats. Peak diastolic velocity and systolic velocity are greatly reduced in the cat with HCM (b), indicating diastolic dysfunction. S’ = systolic myocardial velocity

Thickened RV free wall

While the LV dominates the echocardiographic and clinical picture of HCM, the right ventricle can also be too thick. In about half the cases of feline HCM, the RV free wall is also mildly thickened.26,27

Cardiac biomarkers

The measurement of NT-proBNP and cTn I concentrations in serum or plasma has been evaluated extensively as a means of screening for HCM in cats without heart failure (subclinical HCM) in veterinary referral hospitals and also as a means of differentiating heart failure from primary respiratory disease in cats presented for dyspnea.132–136

In general, NT-proBNP is reasonably accurate for detecting severe HCM in a referral clinic and reasonably accurate for determining if a cat has left heart failure due to a severe cardiomyopathy when presented for dyspnea. However, it is not accurate enough to be a definitive test and so should generally be used in conjunction with other diagnostic tests, if possible. As an example, in one study approximately half the cats with subclinical HCM had a normal plasma NT-proBNP concentration (general practice population). 137 Other work suggests that cats in a referral population and with more advanced stages of subclinical HCM are more likely to have a higher plasma NT-proBNP concentration. 138 The quantitative NT-proBNP assay is most reliable when used to assess cats referred for a heart murmur, gallop rhythm or arrhythmia or when radiographic heart enlargement is detected.137,139 In general, a plasma NT-proBNP concentration >99 pmol/l suggests that mild to severe HCM is present, although this cut-off is less reliable in a general practice feline population.137,139 Further evaluation via echocardiography is generally indicated if this sort of elevation is identified. However, owners should be made aware that some cats with a high NT-proBNP concentration, especially male cats, will have a normal echocardiogram. 140

One study examined the ability of a highly sensitive cTn I assay (ADVIA; Centaur TnI-Ultra, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) to distinguish normal cats from cats with HCM. 141 For all cats with HCM, including those in heart failure and those with ATE, the test was 92% sensitive and 95% specific (cut-off of 0.06 ng/ml). Using the same cut-off, if only cats with subclinical HCM were evaluated the test was 88% sensitive and 95% specific. In another study, a standard cTn I assay was used to identify cats with subclinical and clinical HCM. A cut-off of 0.163 ng/ml was only 62% sensitive but 100% specific at distinguishing normal cats from cats with subclinical HCM and no LA dilation. A cut-off of 0.234 ng/ml was highly sensitive (95%) but less specific (78%) for identifying cats with heart failure due to HCM. 89

The ability of these tests to identify cats in the general population, with or without auscultatory abnormalities, at risk for morbidity and mortality associated with anesthesia and surgery has not been evaluated. The authors believe these tests should not be considered comprehensive methods for ruling in or ruling out HCM nor be used as part of the chemistry panel in the general population at this time.

Arrhythmias

Numerous types of arrhythmias can be identified on a resting ECG, including atrial and ventricular premature complexes (APCs and VPCs), atrial and ventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation. While the ECG is sensitive for detecting atrial fibrillation, atrial fibrillation is not an easy diagnosis to make in a cat (the ECG may not be specific for atrial fibrillation in cats). 146 Sinus rhythm with small P waves (which may be obscured by artifact) and frequent APCs and atrial tachycardia often masquerade as atrial fibrillation in cats. The ECG is insensitive for detecting sporadic APCs and VPCs in any species. A 24-h ambulatory ECG (Holter monitor) is a more sensitive means of identifying these arrhythmias.147–151

In one study, most cats with HCM, either subclinical or clinical, had more VPCs than normal cats. 150 Some had tens of thousands in one 24-h period. However, some had no more than a normal cat (0-13 VPCs per 24 h), a finding that has been noted in previous work.149,151 Only cats with HCM had ventricular tachycardia. There was no correlation between plasma cTn I concentration and the number of VPCs and there was no apparent relationship between the arrhythmias and prognosis. Consequently, whether or not a drug like sotalol should be used in an attempt to prevent sudden death due to ventricular fibrillation in cats with HCM and documented ventricular tachycardia remains an open question.

Treatment

There is no documented reason to treat a cat with subclinical HCM that has mild to severe wall thickening and a normal to mildly enlarged LA (stage B1) if the goal is to delay the onset of heart failure. This is because there is no medication (including ACE inhibitors, beta blockers and spironolactone) that has been shown to reduce hypertrophy or slow progression of the disease, if it is destined to progress.152–156 Therefore, the best that can be done is to:

✜ Monitor the cat for the development of severe LA enlargement (so that antiplatelet/ anticoagulant therapy can be started);

✜ Avoid treatments that can trigger heart failure iatrogenically (eg, injudicious fluid therapy);

✜ Not breed the cat if it is sexually intact;

✜ Monitor for the onset of left heart failure (PE and/ or PLE), if the LA is moderately to severely enlarged.

The best way to do the last is to have the owner monitor the cat’s sleeping respiratory rate (RR; normal is <30 breaths/min) and to maintain a log. In general, this should only be performed in a cat with evidence of moderate to severe LA enlargement to avoid overvigilance.157,158 The owner then needs to be instructed to call a veterinarian when the sleeping RR increases, before the onset of any severe dyspnea and hopefully avoid the all-too-common weekend or evening visit to an emergency clinic.

Antiarrhythmic agents

Beta blockers (eg, atenolol) and calcium channel blockers (eg, diltiazem) have been used to treat subclinical feline HCM. The use of beta blockers is partly an extrapolation from their use in humans where they alleviate angina and exertional dyspnea, particularly in patients with SAM.2,159 There is no evidence that cats with HCM experience chest pain (angina) and they only rarely exert themselves, so extrapolation from humans in this regard is difficult to justify.

Atenolol does have effects on cardiac function in cats.160,161 In normal cats at doses of 6.25 mg or 12.5 mg, it reduces heart rate, peak myocardial velocity during systole (S’), peak myocardial velocity during early diastole (E’), LA fractional shortening and LA ejection fraction. So, it decreases systolic and diastolic LV function and LA systolic function. It does not reduce systolic blood pressure. In cats with HCM, with or without LA enlargement, it has similar effects on heart rate, and LV systolic and diastolic function.

Atenolol administration does not prolong 5-year survival in cats with subclinical HCM, 152 nor does it reduce plasma NT-proBNP or cTn I concentrations in cats with subclinical HCM,156,162 or improve activity level or quality of life. 156 However, it does reduce heart rate and murmur intensity and NT-proBNP and cTn I are higher in cats with SAM due to HCM than those with HCM alone. 163 However, in the authors’ opinion and based on most of the literature, there appears to be no justification for the use of a beta blocker in cats with subclinical HCM and mild to moderate DLVOTO due to SAM. The authors do, however, think it is justified in those with severe DLVOTO due to SAM, as explained below.

Diltiazem was popular for decades (1990s and 2000s) for treating cats with both subclinical and clinical HCM based on work undertaken in the 1990s. 164 It has since fallen out of favor with most veterinary cardiologists because of perceived lack of efficacy and gastrointestinal (GI) side effects with some of the extended-release formulations, but not because new clinical trials provided evidence that overrode the original findings achieved with non-extended-release diltiazem. 165

DLVOTO, most commonly due to SAM, is a frequent therapeutic target. It has been treated with both atenolol and diltiazem, but atenolol is more efficacious at reducing the degree of dynamic obstruction (stenosis; pressure gradient; peak blood flow velocity via Doppler echocardiography).151,166,167 An increase in contractility worsens SAM so it stands to reason that a beta blocker (a negative inotropic agent) would reduce it. Disopyramide, an antiar-rhythmic agent that is also a potent negative inotrope, is another agent used in human patients to reduce SAM, primarily in those in whom a beta blocker has been ineffective.2,168 It can be combined with a beta blocker. There is only one report of its successful use in a cat with severe DLVOTO; it was combined with carvedilol, which did not work on its own. 169

It stands to reason that SAM, and so the degree of DLVOTO, worsens when a cat is stressed (eg, in a veterinary clinic) and improves when a cat is resting/sleeping (75% of its life). 156 Thus, SAM is likely at its most severe during an examination by a veterinarian and at its best at home. Therefore, in the authors’ opinion, it is illogical to try to lessen the degree of SAM in cats where stress is not a common event, particularly if medication administration is itself a stressful event. However, it is possible that a cat that has severe SAM either has the same degree of SAM at home or has the potential to generate the same or greater degree of SAM if maximally stressed at home. It has been shown that cats with SAM, for any given degree of LA size, have higher NT-proBNP and cTn I concentrations. 163 So, in the authors’ opinion, it is likely appropriate to treat a cat that has severe SAM (peak velocity through the LVOT >4.5-5.0 m/s), especially if that cat is likely to be maximally stressed while at home (eg, has access to the outdoors where it may get in a cat fight or be chased by a dog). Therefore, it is recommended that a cat with severe SAM be placed on atenolol (6.25-12.5 mg/cat PO q12h) if it can be administered relatively easily, consistently and without stress. 8

Antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants

A cat with subclinical HCM with severe LA enlargement is at risk for developing an intracardiac thrombus, most commonly in the left auricle (LA appendage) (Figure 1). Medication is indicated to try to prevent intracardiac thrombus formation in these cats.

Clopidogrel, either alone or possibly in combination with rivaroxaban, is currently the only drug that has been shown to decrease the incidence of recurrent systemic ATE in a population of cats.170,171 While clopidogrel has only been shown to prevent ATE recurrence, one can probably assume that if a drug can delay or reduce the risk of ATE in a population of cats that has already experienced one bout of ATE, it can probably delay or reduce the risk of the first formation of a left auricular thrombus also. However, it is not 100% efficacious due to factors such as differences in bioavailability from cat to cat, polymorphisms in genes that encode for platelet proteins, and owner adherence/compliance. For example, while bioavailability of clopidogrel in cats is unknown, it is known that there is a correlation between plasma clopidogrel and clopido-grel metabolite concentrations and platelet inhibition, but that correlation is weak, meaning there are other factors that also play a role in determining platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. 172 One of those factors is genetic polymorphisms (variants) in genes that encode for platelet adenosine diphosphate receptors. 172 Caveats aside, clopidogrel (18.75 mg/cat PO q24h) is the current standard for trying to prevent both first-time and recurrent ATE.

Since clopidogrel is not 100% effective, the search continues for drugs that can be used on their own or in combination with clopidogrel to prevent ATE. A common combination in human medicine is clopidogrel and aspirin (25 mg/kg PO q48-72h). 173 This combination is currently used by some veterinarians for treating cats at high risk for ATE. Both are antiplatelet drugs, so the combination is assumed to be more effective at inhibiting platelet function in cats than clopidogrel on its own. Anticoagulants, either alone or in combination with an antiplatelet drug such as clopi-dogrel, have not been formally studied, but may be as effective as, or more effective than, clopidogrel alone. These anticoagulants include the low molecular weight heparins (eg, enoxaparin [0.75-1 mg/kg SC q6-12h]) and the selective Xa inhibitors (eg, rivaroxaban [0.5-1 mg/kg PO q24h]; apixaban [0.625 mg/cat PO q12h]).171,174–178 Potential adverse effects primarily relate to bleeding complications. A recent study retrospectively examined use of clopidogrel in combination with rivaroxaban in cats with ATE, in cats with intracardiac thrombi and in cats with spontaneous echocardiograph-ic contrast. 171 Side effects (epistaxis, hemateme-sis, hematochezia or hematuria) occurred in 5/32 cats but none required hospitalization. It should also be noted that clopidogrel is bitter. Consideration should be given to placing the quartered tablet inside a small gelatin capsule or a pill pocket prior to administration. 179

Loop diuretics

Cats with PE (stage C) need to be treated with a loop diuretic – either furosemide or torsemide (torasemide). Route of administration and dosage depend on the nature and severity of clinical signs at presentation, severity of radiographic changes and response to initial therapy. Cats presented for veterinary attention due to dyspnea and severe tachypnea (most will have an RR in the 70s or 80s) typically have severe PE and so need to be treated with high-dose parenteral furosemide. The initial dose for such severe cases is 3-6 mg/kg, preferably IV, but IM can be used if catheter placement is too stressful. A constant rate infusion of 0.5-1 mg/kg/h can also be administered. 180 Once administered, the cat should be placed in an oxygen-enriched environment and left alone to reduce stress. A hiding box placed in the oxygen cage can significantly reduce stress for some cats. 181

If the dyspnea has not improved and the RR has not decreased significantly within 1-2 h, the initial dose or higher should be repeated and reassessment performed (eg, is the radio-graphic/point-of-care diagnosis of PE correct and is the IV catheter patent and in the vein?). Assuming no errors in diagnosis or treatment, this same dose or higher should be administered until the dyspnea has improved and the RR is below 50 breaths/min. At that time, the dose and dosing frequency should be decreased, oftentimes dramatically, or the drug discontinued for several hours.

Dyspnea due to severe PLE should be treated with thoracocentesis, as outlined in Part 1. Cats that are stable or have been stabilized need to remain on a loop diuretic, usually for life. The dosage varies depending on the severity of the PE and needs to be titrated based on the sleeping RR (goal is to keep it <30 breaths/min). 157 A typical furosemide dosage for a domestic cat is 1-2 mg/kg PO q8-12h but the dosage can increase up to 4 mg/kg PO q8h (12 mg/kg/day) and sometimes even higher (as high as 16.6 mg/kg/ day in one study 182 ). The initial dosage for torsemide is typically in the range of 0.1-0.3 mg/kg PO q24h. 183

A cat in stage D heart failure is refractory to furosemide administration, meaning clinical signs (eg, elevated sleeping RR [tachypnea], dyspnea) are persisting despite treatment. A cat that is not responding adequately to high-dose furosemide PO may not be responding because not enough drug is getting to the nephron due to poor bioavailability (poor absorption from the GI tract). Such a cat can be treated with parenteral (SC) furosemide (100% bioavailability) or switched to oral torsemide, which is more readily absorbed from the GI tract (higher bioavail-ability). Furosemide effect peaks 2-4 h after oral administration and is gone within 6 h (hence the brand name – LAsts SIX hours). Peak torsemide effect also occurs within 2-4 h after oral administration but its effect lasts at least 12 h. 184 Torsemide dosages administered to cats refractory to furosemide in one study ranged from 0.4-1.6 mg/kg q24h. 182 In another study dosages ranged from 0.1-0.75 mg/kg q24h, administered either once a day or divided into two doses. 185 In general, when switching from furosemide to torsemide, the dose of torsemide is 1/10 to 1/20 that of furosemide.

Torsemide can also be used as first-line therapy, where the starting dosage is usually closer to 0.2 mg/kg PO q24h but can be higher (eg, 0.4 mg/kg PO q24h or 0.2 mg/kg PO q12h) in a cat with severe heart failure. The primary problem with using torsemide in cats in the USA is that the smallest commercial tablet is 5 mg. Compounding pharmacies may carry a smaller size. Smaller tablet sizes are available in other parts of the world (licensed for use in dogs).186,187

Pimobendan

The use of pimobendan for the treatment of heart failure in cats with HCM is controversial. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies have shown that the serum concentration is 10 times higher in normal cats than seen in normal dogs for a comparable dose administered orally.188,189 Despite this markedly high serum concentration, LV myocardial function is only mildly increased for a short time when compared with dogs. 190 This finding is corroborated by the fact that pimobendan can be safely administered to cats with HCM, even those with SAM.191,192 If pimobendan did have potent positive inotropic properties in cats, it would be expected to worsen SAM and probably worsen the clinical status of any cat with HCM. Instead it appears to be safe to administer to most cats with HCM and it does not worsen SAM.191,193,194 Consequently, if it is beneficial for treating heart failure in cats with HCM, it must be via a different mechanism. Pimobendan does have the potential ability to improve diastolic function (in dogs) and it has been suggested that it may improve systolic LA function, again for a short time (<3 h) in cats.194–196 Both could result in clinical and hemodynamic improvement in a cat in heart failure due to HCM.

Few controlled clinical trials have been performed looking at pimobendan in cats with HCM in heart failure. In one case-controlled, retrospective study, the drug appeared to produce benefit. 197 However, in a more powerful prospective study it produced no benefit in cats with heart failure due to HCM. 198 The approach the authors generally use is to add it to the treatment protocol for a cat that has persistent signs of heart failure despite maximum diuretic therapy (stage D). Pimobendan is not known to alter platelet function. 199

ACE inhibitors

ACE inhibitors are relatively weak therapeutic agents, especially when compared with loop diuretics. There is some evidence that they are beneficial in cats in heart failure but, in general, one should not rely on them to result in visible clinical improvement.200,201 One study found no benefit; however, it included cats that were not in heart failure and so the strength of its conclusions is limited. 202 In general, the number of medications administered to a cat in heart failure should be minimized to reduce stress. In the authors’ opinion, one drug that might be safely eliminated, if elimination of a drug might be beneficial in this regard, is the ACE inhibitor.

Spironolactone

One small study looked at the use of spironolactone, in combination with a loop diuretic and an ACE inhibitor, and found it to be safe in cats in left heart failure. It also suggested that the drug prolongs survival. 203

Diet

While, in theory, a low sodium diet might be beneficial for a cat in heart failure, it is usually more important that the cat continues to eat. Any diet change that results in decreased food/calorie intake should be avoided. However, in a cat with persistent or recurrent signs of heart failure (eg, tachypnea, dyspnea, elevated sleeping RR), despite an appropriate level of diuretic therapy, a low sodium diet might be a beneficial adjunct to therapy. Certainly, adding sodium to the diet in any form (eg, commercial treats, canned fish, etc) should be avoided in these cats, as should high sodium diets. A list of cat foods and their sodium content is available. 204

One study has suggested that a diet restricted in starch, higher in protein than a control diet and supplemented with docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid results in marginal decreases in LV wall thickness and cTn I in cats with HCM. 205

Mavacamten

A small molecule inhibitor of myocardial contractility (MYK-461; mavacamten) is in phase III clinical trials in humans for the treatment of HCM. 206 It works by causing reversible inhibition of actin-myosin cross bridging. 207 In research cats with HCM it decreases contractility, and so reduces SAM and DLVOTO. 208 It also has the ability to improve diastolic function. 209

Prognosis

The prognosis for HCM depends on the stage of the disease. Many cats with mild to moderate HCM never progress to severe HCM and so have an excellent prognosis. 5 However, if followed serially, a significant number of cats will progress to severe HCM. Most cats with severe LV wall thickening and moderate to severe LA enlargement (stage B2) that are not in heart failure will progress to heart failure or experience ATE. Cats that are at increased risk of developing heart failure more frequently have the following:

✜ A gallop sound or arrhythmia on physical examination;

✜ /Moderate to severe LA enlargement;

✜ Decreased LA fractional shortening;

✜ Extreme LV hypertrophy (supplementary file 22);

✜ Decreased LV systolic function;

✜ Regional wall thinning with hypokinesis (presumed myocardial infarction);

✜ And / or a restrictive diastolic LV filling pattern.210–212

Supplementary file 22 Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the left ventricle from a cat with extreme hypertrophy due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The size of the left ventricular chamber is reduced in diastole. There is end-systolic cavity obliteration

Cats in heart failure due to HCM usually have a terminal disease. Most will die within months, not years. A few will live for up to 2 years. Most cats with ATE are euthanized on presentation but a few (~20%) survive. It is important to keep in mind that a self-fulfilling prophecy is possible, and owners of cats with ATE can be persuaded to euthanize if they perceive the prognosis to be hopeless. Therefore, the inevitability of future recurrence and chronic care need to be balanced against owners’ willingness to accept this and the occasional outlier cat that survives well beyond expectations.6,213

For some perspective, one study examined time from diagnosis of subclinical HCM (stages B1 and B2) to onset of heart failure and found that approximately 7% of the cats developed heart failure within the first year, 20% within 5 years and 25% within 10 years. 5 This is regardless of LA size at the time of diagnosis. Once in heart failure, approximately half were dead within 2 months. Overall, in cats with ATE, 70% were dead within a week. The last stands in contrast to the average survival of 11.5 months in the 37% of cats with ATE that survive the acute episode and the 20% of cats with ATE that lived 4 years or more in other studies.6,213

The exceptions to ′the most will die within months, not years’ rule include cats with TMT and those that are in heart failure due to stress, fluid administration or corticosteroid administration. These cats can stabilize after being treated for heart failure and may live for years. 6 In cats that are in heart failure due to HCM and concurrent hyperthyroidism, successful treatment or control of the hyperthyroidism often makes it easier to control the heart failure.

It is tempting to think about using NT-proBNP concentration as a tool to help determine prognosis. To date there are no studies to suggest that baseline NT-proBNP at the time of diagnosis of heart failure can be used to help determine prognosis in a cat with HCM. There is one study that suggests that, as a group, cats that experience a greater decrease in NT-proBNP during hospitalization for treatment of heart failure live longer. 214 However, how that translates to individual cats is unknown. That same study found that cats whose owners had difficulty administering medication fared worse. Therefore, adherence/compliance and ability to administer medications are key factors in treatment success. Pill pockets and small amounts of tuna can be helpful. One of the authors finds it easier to administer oral tablets and capsules using a hemostat.

Key Points

✜ Although many cats with HCM do not have a heart murmur, the presence of a heart murmur makes it more likely that a cat has HCM compared with a cat without a murmur.

✜ Screening cats for subclinical HCM should be performed using echocardiography because measurement of circulating cardiac biomarkers and thoracic radiography are inaccurate, primarily due to low sensitivity.

✜ Impostors for HCM include TMT, dehydration, systemic hypertension, hyperthyroidism and acromegaly. These and other phenocopies (disorders that produce the appearance of LV thickening on an echocardiogram) evolve differently from HCM and should be ruled out in order to make the diagnosis of HCM, especially when the LV wall thickening is mild to moderate.

✜ Severe DLVOTO with HCM, commonly referred to as hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), can be treated with a beta blocker. However, while A the benefit of doing so would appear to be self-evident, it is extrapolated from human medicine and is unproven in feline HCM.

Footnotes

Supplementary material: Brief outlines of the supplementary files are provided below; fuller descriptions accompany the files that are available online at journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1098612X211020162.

Files 1–3: Videos showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the LV over time from a cat with presumed HCM. The cat went on to have a diagnosis of TMT.

Files 4 and 5: Videos showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the LV of a cat with SAM due to HCM.

Files 6 and 7: Videos showing a left apical echocardiographic view of SAM in a cat with HCM.

File 8: Video showing a right parasternal color flow Doppler echocardiographic view of the two turbulent jets commonly seen in a cat with SAM.

Files 9–12: Video and still frames showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the basilar interventricular septum bulging into the LVOT in systole creating DLVOTO.

File 13: Image of a continuous wave Doppler trace showing the late peaking signal due to DLVOTO.

File 14: Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of a cat with end-stage HCM.

File 15: Video showing a real-time MRI of a heart from a cat with severe HCM. Courtesy of Kristin Lavely, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (Cardiology).

Files 16–19: Videos showing echocardiographic findings in a cat with severe HCM, including global LVH, SAM, large and hyperechoic papillary muscles, a thick interventricular septum and LV free wall, and an enlarged LA.

File 20: Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view from a cat with a bulge of the basilar interventricular septum.

File 21: Video showing a right parasternal long-axis echocardiographic view of the heart from a cat with HCM. The interventricular septum, including the basilar part, is thicker than normal, with the thickened basilar septum narrowing the LVOT, making it easier for SAM to form.

File 22: Video showing a right parasternal short-axis echocardiographic view of the LV from a cat with extreme hypertrophy due to HCM.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and / or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/ or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This work did not involve the use of animals and therefore ethical approval was not specifically required for publication in ]FMS.

Informed consent: This work did not involve the use of animals (including cadavers) and therefore informed consent was not required. No animals or people are identifiable within this publication, and therefore additional informed consent for publication was not required.

Contributor Information

Mark D Kittleson, School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Medicine and Epidemiology, University of California, Davis, and Veterinary Information Network, 777 West Covell Boulevard, Davis, CA 95616, USA.

Etienne Côté, Department of Companion Animals, Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada.

References

- 1. Cirino AL, Ho C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. (eds). GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle, 1993. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1768/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hyper-trophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. ] Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: e159–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maron BJ. Clinical course and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl ] Med 2018; 379: 655–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferasin L, Sturgess CP, Cannon MJ, et al. Feline idiopathic cardiomyopathy: a retrospective study of 106 cats (1994-2001). ] Feline Med Surg 2003; 5: 151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fox PR, Keene BW, Lamb K, et al. International collaborative study to assess cardiovascular risk and evaluate long-term health in cats with preclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and apparently healthy cats: The REVEAL Study. J Vet Intern Med 2018; 32: 930–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rush JE, Freeman LM, Fenollosa NK, et al. Population and survival characteristics of cats with hypertrophic cardio-myopathy: 260 cases (1990-1999). ] Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 220: 202–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kittleson MD, Meurs KM, Harris SP. The genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats and humans. J Vet Cardiol 2015; 17 Suppl 1: S53–S73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luis Fuentes V, Abbott J, Chetboul V, et al. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of cardiomyopathies in cats. ] Vet Intern Med 2020; 34: 1062–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sangster JK, Panciera DL, Abbott JA, et al. Cardiac biomark-ers in hyperthyroid cats. ] Vet Intern Med 2014; 28: 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schrope DP. Prevalence of congenital heart disease in 76,301 mixed-breed dogs and 57,025 mixed-breed cats. J Vet Cardiol 2015; 17: 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]