Abstract

The field of two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterial-based cancer immunotherapy combines research from multiple subdisciplines of material science, nano-chemistry, in particular nano-biological interactions, immunology, and medicinal chemistry. Most importantly, the “biological identity” of nanomaterials governed by bio-molecular corona in terms of bimolecular types, relative abundance, and conformation at the nanomaterial surface is now believed to influence blood circulation time, bio-distribution, immune response, cellular uptake, and intracellular trafficking. A better understanding of nano-bio interactions can improve utilization of 2D nano-architectures for cancer immunotherapy and immunotheranostics, allowing them to be adapted or modified to treat other immune dysregulation syndromes including autoimmune diseases or inflammation, infection, tissue regeneration, and transplantation. The manuscript reviews the biological interactions and immunotherapeutic applications of 2D nanomaterials, including understanding their interactions with biological molecules of the immune system, summarizes and prospects the applications of 2D nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy.

Key words: Two-dimensional nanomaterials, Nano-bio interactions, Immune system, Antigens, Adjuvants, Modulators, Cancer immunotherapy, Biosensing

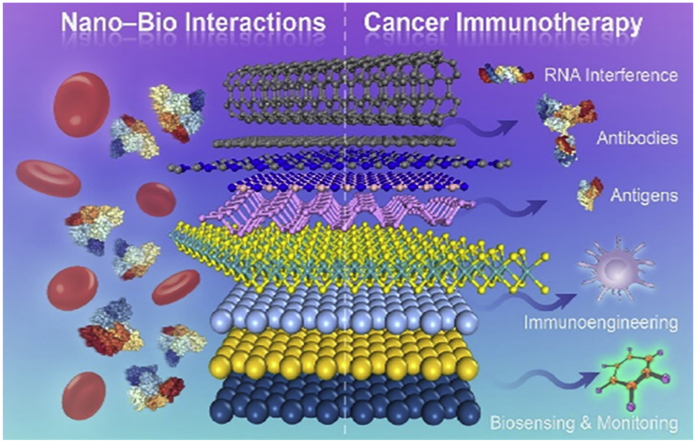

Graphical abstract

The two-dimensional nanomaterials would affect and could modulate immune system via specific design, which endows them great potential in cancer immunotherapy.

1. Introduction

The immune system plays a critical role in the causation and cure of various diseases including cancers. It is the main actor in chronic inflammation that promotes tumor development1, but it can also respond to malignant cells and kills them without harming healthy tissue2. Therefore, shaping the body's innate immune response has great potential for cancer treatment. At present, the treatment of cancer by regulating the immune system has become a very potential way, through the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors3, T cell therapy, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines to achieve tumor treatment. With the advent of nanotechnology, it has also continued to exert its advantages in the field of immunotherapy, including the ability to improve the stability of monoclonal antibodies and vaccines, improve their pharmacokinetics, and achieve the co-delivery of antigens and adjuvants realize simultaneously diagnosis and treatment4. Owing to the unique properties of two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials5, 6, 7 (e.g., high aspect ratio, ultra-high surface area, ultra-high therapeutics loading capacity, tunable structure and surface chemistry, and adjustable/desired physical characteristics), they have shown great promise for amplifying immune activation and enhancing targeted delivery of tumor vaccines, modulators and therapeutics through their intrinsic properties and surface modifications. Compared to other dimensional nanoparticles, 2D nanomaterials would provide ultra-high surface area for interacting with biological molecules related to the immune system, and then influence the immune system. Not only that, the tunable and complex surface chemistry of 2D nanomaterials endowed them with better ability in terms of immune modulation. The high loading capacity could also be utilized to deliver immune modulators for better immunotherapy than other types of nanomaterials.

2D material refers to substance with a thickness of a few nanometers or less which normally exists as layered material with strong in-plane bonds and weak van der Waals-like coupling between layers. Since the first report of few-layer graphene prepared by mechanical exfoliation in 2004 by Novoselov and Geim, the area of 2D materials is booming in the next decade8. The unexpected physiochemical, electronic, and optical properties of graphene thus inspire the exploration of other 2D nanomaterials9. Studies on graphene, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), MoS2, black phosphorus (BP), MXene, etc. have opened sights on electronics, catalyst, sensors, energy storage, biomedicine and so on10. The deep understanding and on-demand fabrication of 2D material are emerging but remain focus research. Exploring new materials has always been a hotspot. However, currently, the research on 2D materials, especially the emerging 2D materials like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), MXene, Metal–organic frameworks (MOF) and Covalent organic frameworks (COF), is still at an early stage. The synthesis methods, physicochemical, and thermal properties have gained extensive focus to expand their applications.

Adoption of 2D materials in biomedicine is challenging but inevitable11. Unlike the mature applications in electronics, their application in biomedicine is still in the early stage but with exponential growth. Currently, there are two main trends in biomedicine. One is devices based on optoelectronic materials such as sensors and wearable devices. The other is to perform as the therapy materials which are based on their large surface area, water solubility, biocompatibility and easy functionality. Such applications have already been applied in drug delivery system, disease theranostic, cell and tissue engineering, and studies on pharmacology and toxicology. For example, inspired by the excellent thermal property and drug loading ability, numerous researches have been focused on the cancer therapy by 2D materials via photothermal therapy, combined with chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy, etc. Considering the rapid development of nanotechnology, future direction should be spotted on the rational design of 2D materials with desired structural features toward specific applications, such as size, thickness, structure, crystal phase, modification, defects, doping, etc11,12. Additionality, the clinical application of 2D materials is urgent. Efforts should be devoted to the clinical trials rather than staying at the proof-of-concept demonstration. Therefore, robust interdisciplinary cooperation is required to push 2D materials to a new level.

The field of 2D nanomaterial-based cancer immunotherapy combines research from multiple subdisciplines of material science, nano-chemistry, immunology, and medicinal chemistry. Before the application of 2D nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy, more knowledge about the interactions between 2D nanomaterials and biological substances should be gained. Most importantly, the “biological identity” of nanomaterials governed by biomolecular corona in terms of biomolecule types, relative abundance, and conformation at the nanomaterial surface are now believed to influence blood circulation time, biodistribution, immune response, cellular uptake, and intracellular trafficking13,14. A better understanding of nano-bio interactions can improve the utilization of 2D nano-architectures for cancer immunotherapy and immunotheranostics, allowing them to be adapted or modified to treat other immune dysregulation syndromes including autoimmune diseases15 or inflammation16, infection17, tissue regeneration18, and transplantation19. Although there are few studies focused on regulating the nano-bio interactions of 2D nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy, it is urgent to comprehensively summarize the ignored important knowledge which will benefit the field of cancer immunotherapy.

Herein, the manuscript will review the interactions of 2D nanomaterials with biological molecules which would influence the immune system (Fig. 1). The properties of 2D nanomaterials allow for unique opportunities in modulating key components of the immune system, such as the inherent activation of immune cells and functional delivery of immunomodulators, as well as biosensing and monitoring of immune response. Furthermore, we will discuss the potential obstacles for practical application, including toxicity arising from unintended interaction of 2D nanomaterials with various components of the immune system, and their relevant implications for rational design. We will summarize by providing relevant insights on the future application of 2D nanomaterials, and how toxicological studies and nano-bio interactions will be key clues enabling the safe design of 2D nanomaterials as a platform for cancer immunotherapy. We believe that revealing the connection between 2D nanomaterials with the immune system would largely link the fields of materials science and biomedicine, inspiring further development and optimization of 2D nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 1.

The combination between nano-bio interactions understanding and cancer immunotherapy.

2. Nano-bio interactions of 2D nanomaterials

With the continuous development of the application of nanomaterials in the field of biomedicine, more and more scientists have begun to pay attention to the interaction between nanomaterials and organisms. Not only that, but nanomaterials also affect the immune system through various nano-bio interactions, influencing their biocompatibilities simultaneously. It is recognized that the human body's immune system plays an important role in avoiding contamination by foreign microorganisms and maintaining immune tolerance to antigens in the environment. To distinguish harmful antigens from harmless antigens, dendritic cells (DC) in the immune system perceive the environment and adjust their phenotype to achieve the most suitable response: immunogenicity and tolerance20. When nanomaterials enter the body, their interaction with the immune system (including innate and adaptive immune responses) can cause potential immunosuppression, hypersensitivity (allergies), immunogenicity, and autoimmunity. The inherent physical and chemical properties of nanomaterials will affect their immunotoxicity, that is, the side effects caused by exposure to nanomaterials21.

In the immune system, the mononuclear macrophage system plays an important role when exposed to nanomaterials, including the recognition, absorption, processing, and removal of nanomaterials22. Studies have shown that the uptake of nanomaterials can occur through phagocytosis, macropinocytosis, and endocytic pathways mediated by clathrin, pits, and scavenger receptors23. These processes largely depend on the size, properties, and surface characteristics of nanomaterials.

Compared with other types of nanomaterials, 2D nanomaterials have a high specific surface area for the interaction, and their interaction with immune system substances and physiological substances needs more in-depth exploration, because it will largely affect their biological safety and tumor treatment effect. Based on the above reasons, this part will discuss the interactions of 2D nanomaterials with immune system components, and physicochemical factors influencing the immune system and the tumor. The lessons learned from the toxicological and immunological effects of 2D nanomaterials over the past decade will also be summarized.

2.1. The role of protein adsorption in the immune response

Since the emergence of nanomaterials, its variety has been continuously enriched precisely because of its small size and high specific surface area, and its application in the field of biomedicine is also in full swing. Although more and more pre-clinical or clinical trials are related to nanomaterials, this phenomenon cannot solve the huge dilemma encountered by nanomaterials.

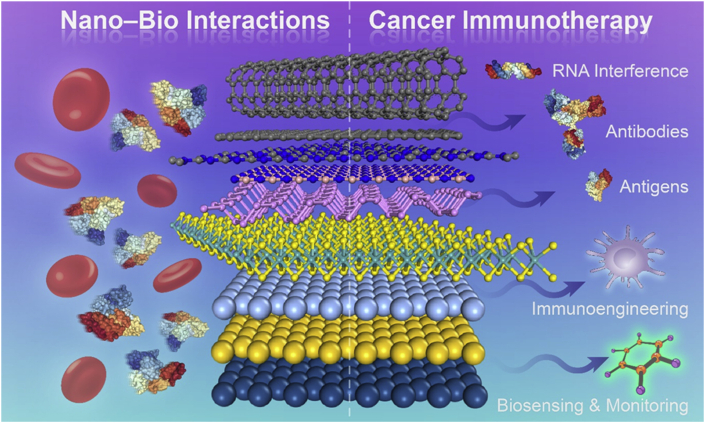

When the nanomaterial enters the body, it will not reach the corresponding area exactly as we expected and play the corresponding function. Due to the complex physiological environment, nanomaterials will encounter a series of roadblocks such as high concentrations of protein after entering the body. As early as 2007, the protein crown phenomenon was revealed. In short, nanomaterials will encounter a high concentration of protein after entering the body, forming a layer of protein crown on the surface of the nanomaterial24 (Fig. 2A). This protein crown will cause a series of unpredictable physiological recognition and unexpected effects, such as that the nanomaterials are recognized by the immune system, and then activate macrophages to clear the nanomaterials. For mammals, the main functions of their innate immune system are to recognize and immediately react to any abnormity, having the feature of nonspecific and no memory. At the same time, the innate immune system can cause sterile inflammation by feeling the damaged cells, and then activate a series of physiological activities. In addition, the adaptive immune system is another defense barrier. Unlike innate immunity, the adaptive immune system recognizes external antigens by destroying them by producing antibodies and then causing specific reactions. This process may take a certain amount of time, but when it encounters the same antigen again, the response speed will be very fast because the memory B and T cells will be activated.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative interactions between nanoparticles and proteins. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 24. Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Ltd.; (B) Detailed overview of the effects caused by nanoparticles on the immune system. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 25. Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; (C) Utilizing the surface chemistry to modulate the protein corona phenomenon with a simultaneously immune-related response. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 26. Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society.

Overall, the immune system's series of reactions need to be realized through first recognition, so the nano-bio effect, especially the protein crown phenomenon, will greatly affect the immune system and induce unwanted effects. Considering the significance of protein coronas of nanoparticles in the immune system, many studies have been concentrated on understanding the factors that influence the immune system response to nanoparticles25 (Fig. 2B). For example, Cai et al.26 studied how surface-induced chemical corona affects the phagocytosis and immune response of macrophages exposed to corona–nanoparticle complexes (Fig. 2C). The results of their research indicate that the corona protein change the internalization pathway of gold nanorods through macrophages through the interaction of the main corona protein with specific receptors on the cell membrane. The cytokine secretion curve of macrophages is also highly dependent on the adsorption mode of the protein corona. The more abundant proteins (such as acute phase, complement, and tissue leakage proteins) present in the obtained nanoparticles corona, the more macrophage interleukin-1β (IL-1β) released by stimulation. Although it is just an example, it is enough to show that this nano-bio effect will greatly affect the immune system, which should attract the attention of scientists in the fields of nanomedicine and immunology. Moreover, the features of nanoparticles that influence the immune system should also be explored and understood deeply. As the focus of our review is 2D nanomaterials, we will only present the connection between 2D nanomaterials and the immune system in the following sections.

2.2. Factors of 2D nanomaterials impacting the immune system

In the database of nanomaterials, 2D nanomaterials, as a rising star, have played a pivotal role in various fields since the advent of graphene. Due to its huge specific surface area, it is more likely to cause nano-bio effects in organisms and influence the immune system, and it deserves more attention. Currently, 2D nanomaterials mainly include graphene materials, synthetic silicate clays, layered double hydroxides (LDHs), transition metal oxides and transition metal dichalcogenides, nanodiscs, and many single-element 2D nanomaterials. Just like other types of nanomaterials, the factors that affect the immune system of 2D nanomaterials mainly include concentration, composition, stability, size, shape, and surface characteristics. The corresponding immune responses to the nanomaterials like inflammatory and toxic effects are critical factors that decide the clinical translation potential of nanomaterials, so we will select some of these factors that influence the immune response/biocompatibility of 2D nanomaterials as follows.

2.2.1. The role of size and concentration in biocompatibility and the immune system

As we presented before, the main parameters of 2D nanomaterials, including their size, shape, and surface properties, can affect the immune system and determine their biological safety. Among them, size and concentration are the basic factors in influencing biocompatibility and the immune system. For example, Akhavan et al.27 evaluated the genotoxicity of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanoplatelets with different sizes (∼11, ∼90, ∼420, and ∼4 μm) in human stem cells (hMSC). After comparing the hMSC toxicities induced by the rGO nanomaterials with various sizes, they found the rGO nanomaterials with the smallest size showed the worst biocompatibility with a low threshold of only 1.0 μg/mL. In contrast, the rGO nanomaterials with the largest size only presented obvious cytotoxicity at the concentration of 100 μg/mL 1 h after co-incubation. Furthermore, the small size of rGO may be able to penetrate the nucleus of the hMSCs and destroy DNA and chromosomal. To further evaluate the biocompatibility of MoS2 nanosheets, Shah et al.28 utilized the electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to study the cytotoxic effect on different cells of different layered nanosheets, and the few-layered nanosheets presented little toxicity. Besides, Liu et al.29 prepared the ultra-small glutathione (GSH) modified MoS2 nanodots and tested the potential toxicities on 4T1 cells. The nanodots presented well biocompatibility under the concentration of 200 μg/mL. Different from previous MoS2 nanosheets or nanoplates, the GSH-MoS2 could be efficiently cleared via urine within just seven days. Furthermore, Mao et al.30 detailly evaluated whether the interactions between graphene-nanosheets with the size of 10 μm and human plasma would induce toxic effects. Firstly, they found that the affinity of proteins to graphene nanosheets presented a concentration-dependent tendency. Moreover, the decrease of nuclei number and increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) were monitored on HeLa and Panc-1 cells after long co-incubation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are considered to be participating in the original immune response of macrophages to foreign substances including nanomaterials, and the increase in ROS content is also considered to be the main reflection of immunotoxicity caused by nanomaterials31. Recently, Sun et al.32 profoundly used live-cell fluorescence, confocal microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy to visualize plasma membrane ruffling and shedding reactions of cells when exposed to GO. The RBL cells, NIH-3T3 cells, and MDA-MB-231 cells presented similar features of characteristic contact inhibition loss and peripheral membrane fragments generation, which would help us to understand how the cell membranes react to GO and further utilize this phenomenon to push more useful biomedical applications of GO. Besides, the concentration of 2D nanomaterials also determines biosecurity. For instance, Teo et al.33 compared the cytotoxicity of several 2D nanomaterials like MoS2, WS2, and WSe2 nanosheets on A549 cells. When exposed to various concentrations of the above different nanomaterials for 24 h, MoS2 and WS2 nanosheets presented negligible toxicity even at high concentrations. On the contrary, WSe2 showed the concentration-dependent tendency on A549 cells, which may be ascribed to the different components. Besides, this feature was more obvious presented in black phosphorus nanosheets. As the research from Kong et al.34 depicted, BP nanosheets would produce more ROS in cancer cells than normal cells under a certain dosage range, then leading to cytoskeleton destruction, DNA damage, and cancer cell apoptosis. While exceeding this threshold, BP nanosheets would also induce side effects on normal cells, which not only provide the selective killing effect of BP nanosheets but also set the safe dosage threshold of BP nanosheets for further bioapplications. In addition, Han et al.35 evaluated the effect of three types of nanosheets (borophene, graphene, and phosphorene nanosheets) on immune responses. When compared to borophene and graphene nanosheets, phosphorene nanosheets would absorb much more immune-related proteins, inducing a different immune response. Further results indicated that phosphorene nanosheets facilitated higher cytokines release than the other two types of nanosheets. Most importantly, the 2D nanomaterials with various sizes and concentrations also impacted the immune system in various manners.

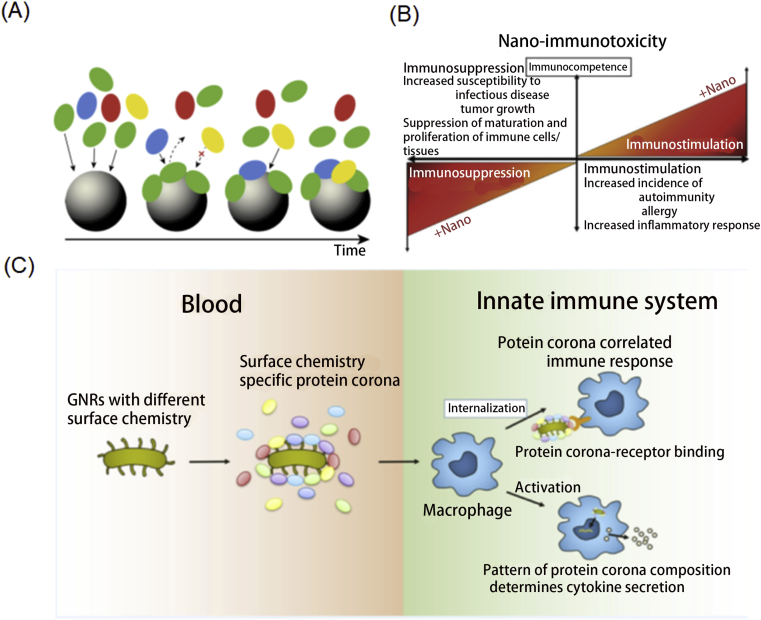

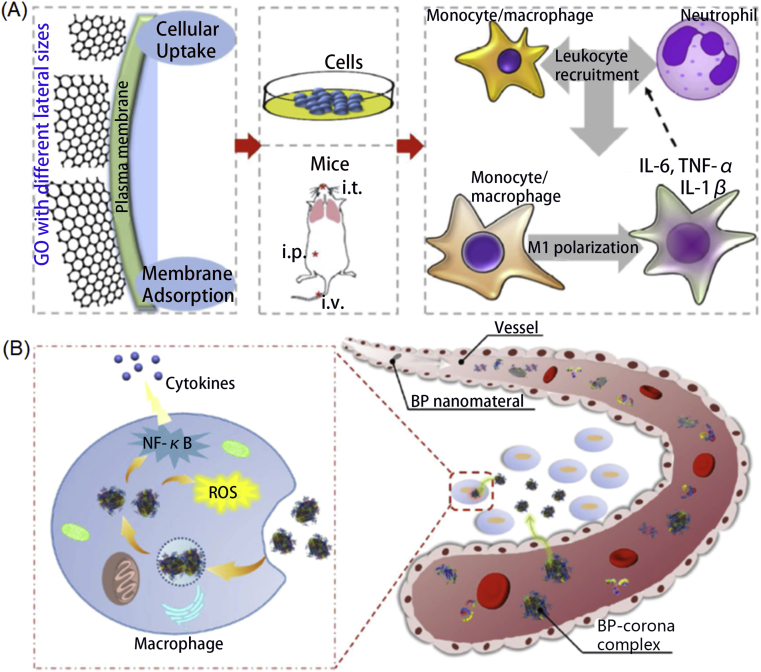

As an example, Ma et al.36 focused on evaluating the role of lateral size of GO in nanosheets in their biocompatibilities (Fig. 3A). Unlike the previous researches which only emphasized the toxicity, this work further revealed the effects in activating macrophages and regulating pro-inflammatory responses. They detected that larger GO nanosheets adsorbed onto the plasma membrane more tightly with less phagocytosis while the smaller GO nanosheets were more easily to be taken up by cells. Thus, larger GO nanosheets would induce greater M1 polarization and increased production of inflammatory cytokines and immune cell recruitment. Although MoS2 nanosheets with the size of 100–250 nm and 400–500 nm both had no obvious side effects on dendritic cells at all doses, the CD40, CD86, CD80, and CCR7 expressions were largely higher when the dose amounted to 128 μg/mL for the both sized nanosheets. The TNF-α production and IL-1β secretion would increase and decrease respectively when increasing the MoS2 nanosheets dose. Additionally, according to the expression of CD107a, CD69, and ICOS, enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation and activation had been monitored with the administration of MoS2 nanosheets in vivo. Wang et al.37 also evaluated the different in vivo immune responses triggered by graphene nanosheets and multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Judging from the molecule analysis of mice after injected with graphene nanosheets and multiwalled carbon nanotubes, they found the two nanoparticles promoted Th2 immune responses via IL-33/ST2 axis, resulting in unwanted side effects.

Figure 3.

(A) The size of GO nanomaterials matter in affecting the immune system. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 36. Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society.; (B) Scheme of BP–corona complex in immune system regulation. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 38. Copyright © 2018 Springer Nature Limited.

Furthermore, Mo et al.38 utilized liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to reveal that plasma proteins onto BP nanomaterials were mainly immune-related proteins and would induce a perturbation effect on the macrophages. BP quantum nanodots and nanosheets absorbed different ratios of immune-related proteins, which would affect cellular uptake, cytokine secretion, generate ROS, and regulate the NF-κB pathway to some degree and subsequently generate immunotoxicity (Fig. 3B). Orecchioni et al.39 also confirmed that different sizes of GO nanosheets would induce different immune system responses. They had analyzed the 84 immune-response-related genes after coincubation with GO-small and GO-large nanosheets, and had known that GO-small regulated more genes than that of GO-large, which clearly showed a size-dependent impact on the immune system. The leukocyte chemotaxis pathway also supported that GO-small nanosheets influenced immune cell activation.

2.2.2. The influence of surface chemistry on the immune system

As described before, the nano-bio interface plays an important role in the immune system and future clinical translation. Besides the above factors of 2D nanomaterials that affect the immune system, one critical factor is the surface chemistry of 2D nanomaterials. By processing or coating the surface of the material, the adhesion of proteins and the response of the immune system to nanomaterials can be adjusted. Basically, surface chemistry includes a surface charge, hydrophilic ability, and surface modifications on nanomaterials like PEG, aliphatic chains, and other substances.

Specifically, after many years of development of the surface chemistry of nanomaterials to minimize the side effects on the immune system, some useful conclusions have been concluded. For instance, the positive charge surface on the nanomaterials would react with the many parts in vivo like nucleic acids and anionic proteins, generating inflammatory reactions even under the cytotoxic threshold concentration, which is also applicable for 2D nanomaterials. Specifically, Kedmi et al.40 presented comprehensive evaluations of the toxicity of positive charge nanomaterials. They found that the administration of positive charge nanomaterials activated interferon type I response and the mRNA levels of interferon responsive genes were much higher than negative charge nanomaterials. Besides, the positive charge nanomaterials would also induce a more serious inflammatory response through TLR4 activation. Another work41 compared the uptake efficiency, biocompatibility, and immune responses on Raw 264.7 macrophage cells of GO nanosheets with different surface charges because of different surface modifications like PEG and branched polyethyleneimine. When compared with the GO-PEG nanomaterials which were concentrated in endosomes only, GO-PEI nanomaterials were more efficiently internalized by the cells and gathered in endosomes and cytoplasm. More IL-6 secretion would be promoted by GO-PEG nanomaterials, which demonstrated the better potential of the GO-PEI nanomaterials with positive surface charge. Luo et al.42 further evaluated the effects on macrophages of GO nanosheets without surface modification and those coated with PEG, PEI, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) respectively. Compared with the control GO nanosheets, PEG and BSA modifications would inhibit endocytosis while PEI modification was the endocytosis promoter. Meanwhile, the PEI-GO nanosheets likely to react with mitochondria and induce the apoptosis pathway, showing higher side effects.

Not only the surface charge matter, but PEG modification also affects the toxicity of 2D nanomaterials. Nowadays, PEGylation has been introduced as a universal method to diminish the protein-corona effect, enhance the circulation time and stability of nanomaterials. Gu et al.43 integrated theoretical and experimental methods to compare the interactions of MoS2 nanoflakes (with and without PEGylation) with macrophages. They firstly simulated the atomic-detailed interactions between MoS2 nanoflakes (with and without PEGylation) and macrophage membrane and found that the small MoS2 nanoflakes were able to penetrate the membrane at any concentrations. Moreover, the PEG chains would further inhibit the membrane insertion effect than the only MoS2 nanoflakes (Fig. 4A). Detailed simulation and experiments revealed that the MoS2-PEG activated more cytokine secretion but the same high ROS generation when compared with the MoS2 only. Another research from Luo et al.44 indicated that the PEGylated GO nanosheets induced potent cytokine response in macrophages whether they were internalized or not. The GO-PEG nanosheets would also promote cytokine secretion through integrin b8-related pathway enhancement, which indicated the conclusion that surface passivation may not always inhibit unwanted immunological responses to GO nanosheets.

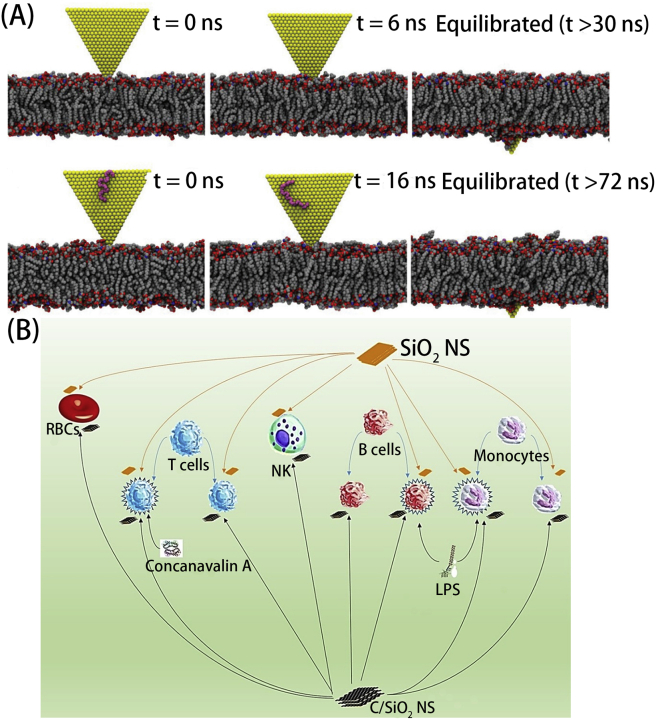

Figure 4.

(A) Macrophage membrane penetration process of the MoS2 nanoflakes without (up) and with PEG (bottom) modification respectively. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 43 Copyright © 2019 Royal Society of Chemistry; (B) Diagram of Immune cells related to the silica and carbon-coated silica nanosheets. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 46. Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V.

In addition, Chatterjee et al.45 further compared the immune responses of the GO/rGO with different surface chemistry. With various hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, GO/rGO presented similar side effects but different mechanisms. For the hydrophilic GO, they were mainly taken up by cells and induce ROS, high antioxidant/DNA repair/apoptosis relevant genes deregulation. While for hydrophobic rGO, they were mainly adsorbed at the cell surface and generated ROS by physical interaction, little gene regulation. Moreover, GO could induce toxicity through the TGFb1 pathway and rGO modulated innate immune reaction via TLR4-NFκB signaling. Al Soubaihi et al.46 tested the impact of SiO2 and carbon-coated SiO2 nanosheets (C/SiO2 NS) on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and other immune cells (Fig. 4B). Some differences had been monitored in the two nanomaterials like the enhanced biocompatibility and lower hemoglobin release of C/SiO2 NS. The same conclusion for the two nanomaterials were no acute inflammation reaction and pro-inflammatory cytokines release monitored. Even though the limited examples presented, they were able to support the importance of surface chemistry of 2D nanomaterials in immune response modulation which would be further presented in the following section.

3. Controlling immune response by structure and surface modifications

With the in-depth understanding of nano-bio interaction, scientists continue to optimize the engineering on the nanomaterials to achieve wanted immune regulation, and then to better release their functions and diminish side effects, especially for 2D nanomaterials. Among them, adjusting the structure and size of 2D nanomaterials or applying surface chemistry to 2D nanomaterials is a promising approach and has been constantly showing its potential. Although as mentioned before, the selection of different materials will cause different immune responses47, our focus is on the means of structural and surface modification. Below, we will list some representative examples including some of those not directly studying cancer immunotherapy but would largely inspire us.

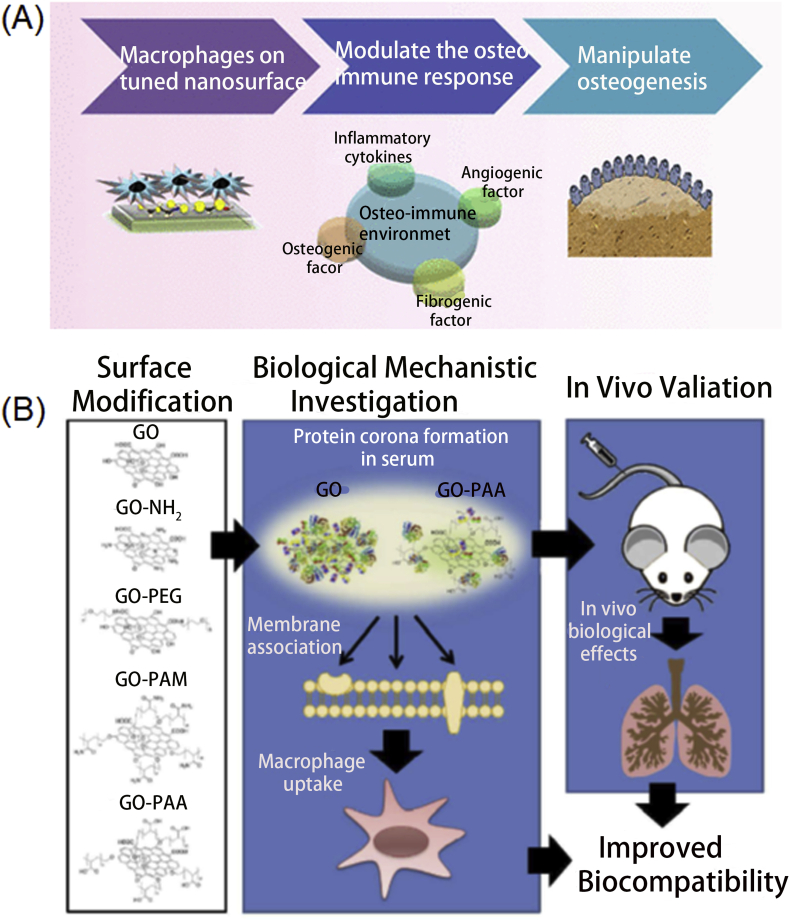

To regulate a helpful osteoimmune environment for bone engineering, Chen et al.48 combined the nanotopography and surface chemistry to realize better osteoimmunomodulatory abilities (Fig. 5A). They have compared several candidates and monitored the changes of osteoimmune-related factors and found the carboxyl acid-modified 68-nm thick surface had the best performance, which highlights the role of surface chemistry and topography in immune response modulation and holds potential in bone-related cancer immunotherapy. Not only that, but Shim et al.49 also used the CD47-like signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα)-binding peptide (SP) to modify the GO nanosheets. As the SIRPα would interact with CD47 to downregulate phagocytosis by macrophages, the SP surface of GO nanosheets ensured lower macrophage phagocytosis than PEGylation on GO nanosheets. In the in vivo experiments, the SP-coated GO nanosheets had longer circulation time after repeated administrations and higher tumor distribution than other groups, which indicated the introduction of SP could largely enhance the clinical translation of GO nanosheets or other 2D nanomaterials. Besides SP modification, poly(sarcosine) chains in peptide nanosheets could also suppress the immune response. Specifically, Hara et al.50 replaced the poly(l-lactic acid) block with the (l-Leu-Aib)6 block in the peptide nanosheets to overcome the accelerated blood clearance phenomenon which was resulted from the immune response. The in vivo fluorescence imaging pictures at different time points further confirmed the immune response suppression effect of the nanosheets. Inspired by the protein corona phenomenon, Chong et al.51 modified the GO nanosheets with serum proteins to largely decrease the cytotoxicity of GO nanosheets, which provided another insightful surface modification method. Similar to the mentioned approach, the natural proteins coated method was also applied in graphene nanomaterials to diminish adverse immune response. Belling et al.52 utilized the complement factor H against unwanted immune responses of complement activation and compared the efficiency with the graphene nanomaterials modified with bovine or human serum albumins. After careful comparison, the complement factor H could almost completely help graphene nanomaterials against complement activation while the other two proteins could only have moderate protection ability, which offered another promising method to regulate immune response to 2D nanomaterials.

Figure 5.

(A) Modulation of immune response for bone regeneration via designing nanomaterials surface and topography. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 48. Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society.; (B) Enhancing the biocompatibility of GO nanomaterials through different surface modifications. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 54. Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society.

Although the BP nanosheets presented well biocompatibility and easy to be degraded, many strategies were employed to further decrease the potential toxicity and proinflammation. For example, Qu et al.53 introduced the titanium sulfonate ligand (TiL4) to modify the BP nanosheets to escape from macrophages, decrease inflammation reaction, and lastly increase their biosafety. Xu et al.54 also utilized surface modification way to improve the biocompatibility of GO nanomaterials (Fig. 5B). As they presented, many GO-based nanomaterials were fabricated including aminated, poly(acrylamide), poly(acrylic acid), and poly(ethylene glycol) modified GO nanomaterials and employed in vitro and in vivo to compare the biocompatibility. Among the various modification substances, poly(acrylic acid) was regarded as the most favorable modification because of the different protein corona components, which ensures the least proinflammation and thrombus formation. The platelet substitutes of HHLGGAKQAGDV (H12) peptide was also used to modify biodegradable poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) nanosheets55, which would efficiently and specifically react with the activated platelets to promote platelet thrombus formation. Also, Chen et al.56 produced two sizes of Pd nanosheets and found that the smaller Pd nanosheets would mainly be cleared through renal while the larger one mainly accumulated in the liver and spleen. Although no obvious toxicities were observed on the small and large nanosheets, slight lipid accumulation and inflammation were monitored. Further gene expression results revealed stronger nano-bio interaction for large nanosheets in the liver, which provided us another method to control the immune response to 2D nanomaterials.

4. Current 2D nanomaterial-based approaches for cancer immunotherapy

For us, the ultimate goal of a clear understanding of the relationship between nanomaterials, especially 2D nanomaterials, and the immune system is to better apply nanomaterials to immune-related applications, including immunotherapy, immune biosensing and monitoring. Cancer immunotherapy has been widely investigated and made huge progress in the last decade. Since then, nanomaterials have gained much attention due to their advantage in high loading efficacy and their role in protecting payload in the physiological environment as well as tumor accumulating effect. Among them, the 2D nanomaterial is one of the most promising materials owing to their unique physicochemical properties discussed above, and the related properties could also be introduced to modulate immune system response when combined with external energy fields such as light and X-ray. Although no researches were reported on using the 2D nanomaterials only without external energy fields activation in modulating immune system for immune system-related applications, we have clearly presented and believed that the unique features of 2D nanomaterials could definitely endow them the ability in regulating cancer immunotherapy when acted as delivery platforms. Moreover, when integrated with external energy fields, the immune system response modulation ability of 2D nanomaterials would be activated. So in this section, we will briefly summarize current progress in immunotherapeutic delivery, immune-combined therapy, and cancer immune biosensing and monitoring, with many of our detailed perspectives on how to utilize the properties of 2D nanomaterials for immune system-related applications.

4.1. 2D nanomaterials for immunotherapeutic delivery

2D nanomaterials, generally presented in sheet-like and lamella structures, exhibit an extremely high drug loading efficiency due to their large surface area. Additionally, 2D nanomaterials, like graphene and their derivatives can interact with drugs via hydrophobic interactions and π–π stacking because of large surface contacts and special sp2-bond of carbon atoms10. Taking these unique advantages and the controlled immune response discussed above, 2D nanomaterials demonstrated great promise in both antigen and adjuvant delivery. In addition, detailed perspectives in utilizing 2D nanomaterials as delivery platforms for immune system modulation in cancer immunotherapy would also be described.

4.1.1. Antigens delivery

To improve the efficacy of antigen presentation on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), nanomaterials are widely adapted as a nanocarrier to protect the antigen from the physiological environment as well as enhance the delivery and uptake to APCs. With a large proportion of atoms presented on the surface, 2D nanomaterials, with and without modification, exhibit dramatically high specific surface area, leading to the improvement in physical and chemical reactivities, including interaction with antigens. Not only that, modified 2D nanomaterials could also be more helpful for stabilizing antigen and be utilized to escape unwanted immune system response which would damage loaded antigens, which may be helpful for better cancer immunotherapy.

Graphene oxide (GO) is widely adapted for protein delivery with high loading efficacy via hydrophobic interaction and π–π stacking57. Li et al.58 reported GO nanosheets that can absorb ovalbumin (OVA) at drug loading capacity (DLC) from 50% to 200% via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobicity-driven absorption. The immunotherapy was investigated by incubating nanomaterials and dendritic cells (DCs). GO nanosheets were first internalized by DCs, followed by the endo/lysosome escape and the release of loaded OVA into the cytoplasm. Cytokine levels, such as interferon (IFNγ), interleukin 13 (IL-13), interleukin 17 (IL-17) was investigated to indicate the successful antigen presentation and T cell proliferation. T cell proliferation was enhanced by OVA-loaded GO at DLC of 50% and 100%, whereas formulation with 200% OVA didn't show much proliferation, which indicated that excess GO is flavored for antigen presentation. Sinha et al.59 developed reduced GO modified with dextran for the successful delivery of OVA to DCs with followed cancer immunotherapy. The efficacy of antigen presentation was enhanced by improved cellular uptake via the specific carbohydrate-protein recognition between dextran and receptors on DCs as well as the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I). The cell line showed the maturation of DCs with high expression of CD86, MHC-I, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Tumor growth was suppressed in vivo by activating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, demonstrating promising cancer immunotherapy.

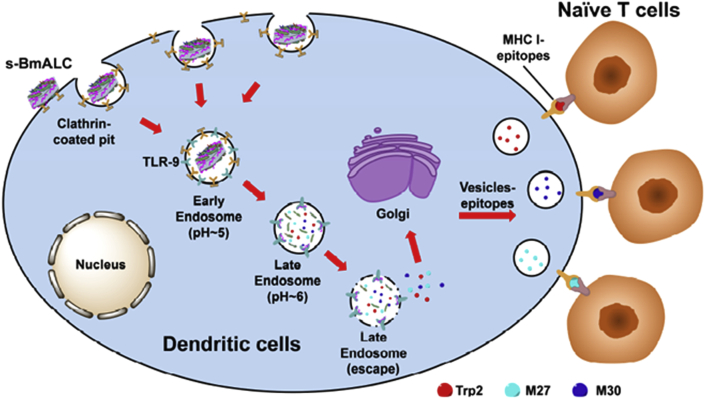

Apart from GO, other 2D nanomaterials also showed gratifying achievement in antigen delivery. For instant, Zhang et al.60 prepared BSA coated layered double hydroxide (LDH) for co-delivery of tyrosinase-related protein 2 (Trp 2) peptide and mutated epitopes (M27 and M30). As shown in Fig. 6, LDH was first internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and then endosome escape and reach the cytosol, where the loaded antigen was released. The free antigen epitope peptides then bind with MHC I to present on the membrane and activated naïve T cells, leading to a strong immune response. In vivo experiment showed strong immune response with T cells proliferation in spleen and high IFNγ level, and significant tumor growth inhibition with 87% tumor volume reduction in B16F10 melanoma bearing mouse model. Pei et al.61 prepared chitosan/calcium phosphate nanosheet by simply mixing chitosan with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and CaCl2. OVA was successfully encapsulated via electrostatic interaction with chitosan during coprecipitation and confirmed by both SEM and XRD. The antigen uptake and presentation were characterized by flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). In vitro test showed that the uptake of OVA-loaded nanosheets was 3.8-fold higher than that of free OVA, indicating enhanced cellular uptake assisted by nanosheet. In addition, nanosheets underwent endo/lysosomal related endocytosis and lysosome escape before entering cytoplasm and releasing payload to activate DCs. Both MHC I and MHC II levels were increased after treating with OVA-loaded nanosheets, illustrating effective antigen presentation via MHC pathway. Moreover, the secretion of various cytokines was also detected with a higher level in OVA-loaded nanosheets groups. Inspired by the above researches, we firmly believed that 2D nanomaterials could largely enhance the antigens stability and overcome many barriers such as avoiding unwanted immune system response on the road to targeted cells, inducing potent cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 6.

Utilizing LDH nanomaterials to deliver BSA-Ags and CpG simultaneously to DCs. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 60. Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V.

4.1.2. Adjuvants delivery

Immunologic adjuvants are nonspecific substance served to potentiate, accelerate, and prolong the specific immune response to antigens where it is administrated62. In general, adjuvants are co-administrated with antigens to protect antigens and promote immunogenicity and immune response to improve their immune response. Similar to antigen delivery, 2D nanomaterials also showed promise in adjuvants delivery in not only protecting, but also accurate delivery and escaping unwanted immune system response to guarantee well biocompatibility and satisfactory cancer immunotherapy.

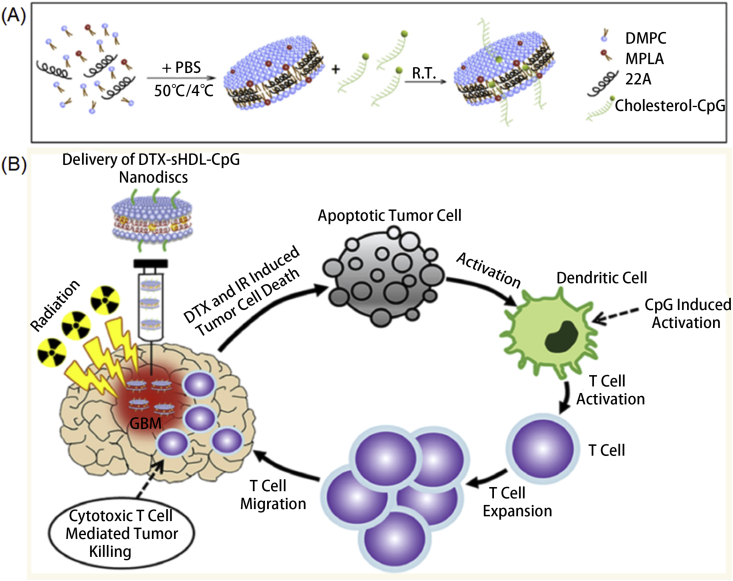

Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, one of the most studied immunologic adjuvants, have been widely applied and studied owing to their specific role in activating DCs63. To that end, Kuai et al.64 developed a series of 2D nanomaterials for different adjuvants delivery. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) nanodiscs containing phospholipids and apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1)-mimic peptides were developed as model vehicles. 5ʹ-C-phosphate-G-3ʹ (CpG), a potent TLR9 agonist, was conjugated with cholesterol and encapsulated into nanodiscs. Co-delivery of CpG and tumor antigen peptides using nanodiscs exhibited prolonged antigen presentation and immune response, which significantly demonstrated tumor inhibition ability. In vitro study showed 9-fold greater levels of antigen presentation than free CpG/antigen delivery. In vivo study demonstrated robust and long-term CD8α+ T-cell response in 2 months, indicating long-lived immunotherapy against tumor cells. Later, they65 developed a dual TLR agonist delivery system for cancer immunotherapy (Fig. 7A). By a combination of MPLA, a TLR4 agonist, and CpG into HDL nanodiscs, the formed adjuvant system prominently enhanced DCs activation with higher levels of CD80 and CD86 than a single TLR agonist adjuvant system. In addition, nanodiscs generated strong humoral immune responses with an obvious reduction of plasma cholesterol, which could largely enhance the biocompatibility of the nanodiscs. To generated strong anti-tumor efficacy, nanodiscs were further loaded with OVA. In vivo anti-tumor study against the B16F10-OVA melanoma model indicated remarkable CD8+ T cell responses, which are 8-fold stronger than free adjuvants. Kadiyala et al.66 also designed HDL nanodiscs for cancer immunotherapy and chemotherapy. CpG and docetaxel (DTX), a chemotherapeutic agent was introduced into the system to achieve synergetic cancer therapy against Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). CpG was applied to activate APCs, such as macrophages and DCs, which further presenting antigens to CD8 T cells, eliciting CD8+ T cell-related immunity (Fig. 7B). DTX was applied for targeting GBM and suppressing tumor growth. Codelivery of CpG and DTX results in significant tumor inhibition with 80% tumor elimination in vivo. moreover, antitumor immunological memory was elicited to prevent tumor recurrence, indicating long-lived antitumor activity. Thus, those nanodiscs related to vaccination provides insight into cancer immunotherapy. Inspired by the related researches, we believe that 2D nanomaterials composed by proteins or peptides could be further explored as they could avoid unwanted immune system response to not only enhance the biocompatibility but also protect the efficiency of the loaded antigens or adjuvants.

Figure 7.

(A) Scheme of dual adjuvant nanodiscs preparation. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 65. Copyright © 2018 Elsevier B.V.; (B) Mechanism of using DTX-sHDL-CpG nanodiscs for antiglioma application. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 66. Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society.

4.1.3. Immune modulators delivery

Immune modulation is more than just boosting the body's immune system. It involves adjusting different immune cells back into balance and bring the body's immune response back to a normal level to correctly and effectively perform its functions, which includes immune response stimulation and suppression67. Thus, unlike immune adjuvants, immune modulators refer to substances that medicate in the regulation or normalization of the immune system, to enable the immune system to function correctly. Through specific modifications, 2D nanomaterials could also be utilized to interfere the unwanted immune system caused by loaded things, acting as modulator-like substances to help cancer immunotherapy.

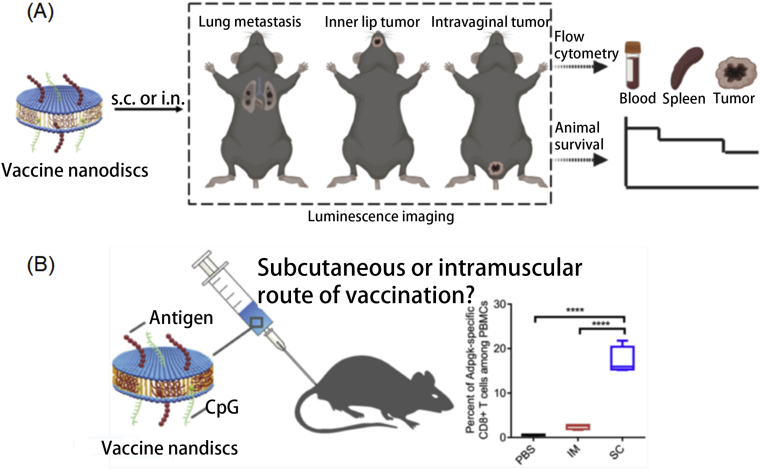

Immune modulators are a class of agents that can assist to modulate the immune response, thus leading to better cancer immunotherapy. Wang et al.68 constructed MnO2-CpG-silver nanoclusters (AgNCs) conjugated with doxorubicin (DOX) for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. CpG was recognized by Toll-like 9 (TLR9) and induced immune response while DOX was applied as an immune modulator by eliciting immunogenic cell death and reduced the immune–suppressive activity. Thus, the antitumor efficiency of AgNCs was enhanced by strong immune responses activated by both CpG and DOX. Additionally, MnO2 nanosheets not only afforded as a drug carrier, but also served as a T1 MRI agent, providing a new sight for cancer immune-theranostic. Mo et al.69 constructed black phosphorus nanosheets (BPNS) with corona protein (BPCCs) which can interact with calmodulin to enhance the activation of stromal interaction molecule 2 (STIM2) and promote the influx of Ca2+. Thus, BPCCs functioned as immune modulators to enhance the immune response. Macrophages treated with BPCCs significantly polarized into M1 macrophages via P38 MAPK and NF-κB P65 pathway. Additionally, the expression of M1 macrophages related cytokines, such as TNF-α, iNOS, IL-12p40, and CD16, were upregulated after treating with BPCCs, indicating the successful M1 macrophage polarization. Kuai et al.70 developed several nanodiscs vaccines. For example, they fabricated high-density lipoprotein (HDL) nanodiscs for antigen and immunostimulatory agent delivery (Fig. 8A). After subcutaneous (SC) injection, the nanodiscs were successfully delivered to draining lymph nodes, along with the uptake by antigen-presenting cells, such as DCs, B cells, and macrophages. Moreover, nanodiscs induced strong Ag-specific T cell response and inhibited HPV16 E7 expressing TC-1 tumors’ growth at lungs, inner lip, and intravaginal tissues with 100%, 100%, and ∼40% survival rate. In addition, they71 also advanced nanodiscs vaccination formulation with human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 E7 antigen and CpG to reach superior T cell responses (Fig. 8B). The nanodiscs elicited 32% E7-specific CD8+ T cells via SC administration, which is 29-fold higher than vaccination containing peptide only. When combined with anti-PD-1 IgG, nanodiscs exhibited excellent anti-tumor efficiency.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic illustration of utilizing vaccine nanodiscs for luminescence imaging-guided immunotherapy. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 70. Copyright © 2020 Wiley-VCH GmbH, Weinheim; (B) Subcutaneous administration of nanodiscs and neoantigens for immunotherapy. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 71. Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society.

Natural killer (NK) cells are another kind of immune-related cells that are capable of killing tumor cells without priming activation72. For an instant, Loftus et al.73 created nanoscale GO with a planar shape which holds the advantage in extending to large sizes. Artificial leukocyte-stimulating ligands were modified on the surface of GO, which mimics the immunoreceptor nanoclusters to bind CD16, one of the best-characterized NK cells activating receptors, and enhance the immune response via the increased secretion of IFN-γ. Inspired by the related researches, we hypothesized that if 2D nanomaterials could be modified to target tumor areas and also captured NK cells to kill tumors, generating enhanced cancer immunotherapy.

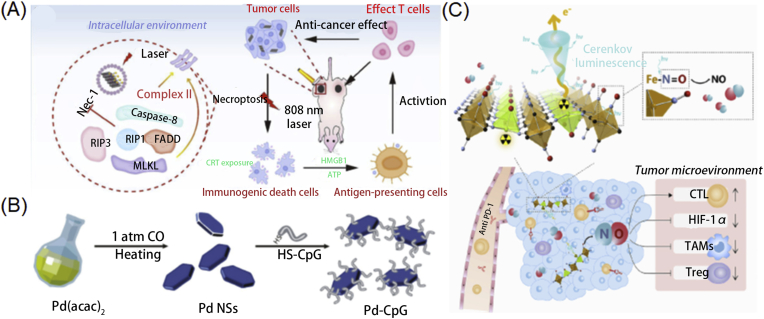

4.2. 2D nanomaterial-based combination therapy

Not only been utilized as delivery platforms for cancer immunotherapy, when combined with external energy fields such as light or X-ray, 2D nanomaterials could activate the immune system response modulation ability largely, so many researches have been conducted in using 2D nanomaterials and external energy fields for cancer immunotherapy. For example, taking the unique physical–chemical properties, 2D materials were applied for the combination of photothermal, radiotherapy, photodynamic, and immunotherapy. Also, numerous studies have demonstrated that the physical–chemical properties could modulate immune system response caused by loaded antigens, adjuvants or modulators, inducing enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Black phosphorus is a biocompatible and biodegradable nanomaterial with a high extinction coefficient in the NIR region, making it a potent candidate for cancer photothermal therapy (PTT). Wan et al.74 developed PEGylated BP nanosheets with imiquimod (R837) for photoimmunotherapy. Tumor antigen can be generated in situ by PTT which was regarded as modulating immune system response, and induced strong immune response together with R837, an immunoadjuvant. Immune-related cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNFα, were significantly upregulated, compared to those treated with only BP plus laser or R837. Additionally, CD80 and CD86, landmark of mature DCs also increased by 30.8%, confirming the excellent immune response by PTT and R837 treatment. In vivo antitumor study showed enhance tumor inhibition with abundant CD8+ T cells for photoimmunotherapy. Zhao et al.75 constructed adjuvant grafted BP nanosheets to achieve enhanced cancer photoimmunotherapy by in situ activation of necroptosis via PTT (Fig. 9A). Immunogenic cell death (ICD) was induced by BP based PTT, causing anti-tumor immunity or regarded as immune system response modulation. Necroptosis was investigated by monitoring cell viability after laser treatment, and ICD was determined by CRT biomarker expression. To further enhance the immune response, CpG was adopted as an immunologic adjuvant. The antitumor efficacy reaches the maximum in the combination of BP nanosheet and CpG group, along with the upregulated immune cytokines. More recently, Li et al.76 constructed Ag ions-coupled BP QDs for synergistic cancer photodynamic/Ag+ immunotherapy. During the PDT process, ICD was induced and Ag+ was released and captured by macrophages to stimulate a pro-inflammatory response. Those synergistically activated the cytotoxic T lymphocytes and further activate the immune response. Su et al.34 developed transformation growth factor-β (TGF-β) inhibitor and neutrophils (NEs) functionalized BP nanoflasks. The combined photodynamic (PDT), PTT, and immunotherapy effectively inhibited tumor growth and lung metastasis. Besides BP, other 2D nanomaterials with excellent photothermal convention efficiency were also widely studied for photoimmunotherapy. For example, Ming et al.77 designed palladium (Pd) nanosheets as a nanocarrier for the delivery of CpG (Fig. 9B). Similarly, Pd-CpG composites increased the level of matured DCs, macrophages, and CD8+ T cells and upregulated the related immune cytokines after laser treatment, demonstrating promising cancer photoimmunotherapy. He et al.78 developed 2D MoS2 nanosheet coated with red blood cell membranes for long circulation and better hemocompatibility. PTT exhibited significant antitumor efficacy, triggering the release of tumor-related antigens and leading to ICD. Meanwhile, immune responses were activated via the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to enhance the antitumor efficacy. Zhang et al.79 advanced MoS2 nanosheet with FePt nanoparticle and folic acid (FA) anchored outside. FA was introduced to target tumor sites and increase cellular uptake. The FePt nanoparticle could catalyze H2O2 to produce toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) via Fenton reaction, functionalizing as a chemotherapy agent. CpG was loaded to activate the immune response and led to systemic checkpoint blockade therapy after combined with the anti-CTLA4 antibody. The combination therapy not only improves the antitumor efficacy, but also obtained a strong immunological memory effect, which benefits long term therapy.

Figure 9.

(A) Illustration of introducing BP nanoparticles for enhanced immunotherapy through photothermal effect. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 75. Copyright © 2020 Wiley-VCH GmbH, Weinheim; (B) Synthesis of Pd-CpG nanosheets. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 77. Copyright © 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry; (C) Utilizing the radioisotope-induced NO release for enhanced radioisotope therapy through modulating the immune response. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 83. Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Ltd.

The synergy of radiotherapy (RT) and immunotherapy also attached more and more attention in recent years. Lu et al.80 developed a series of MOF for radio-immunotherapy. For example, they designed porous Hf-based MOF which performed as radioenhancers. Low dose RT generated ROS and eradicated local tumor after conjugated with anti-PD-L1 antibody, as well as suppressed distant tumors through immunotherapy. Furthermore, they introduced radiodynamic therapy (RDT) into the combination therapy of RT and immunotherapy81. Porphyrin was adopted into the Hf-based MOF to generate 1O2, resulting in RDT, whereas Hf could absorb X-ray photons to generate ∙OH radicals upon radiation. In vivo antitumor study exhibited efficient tumor killing upon irradiation. ELISPOT assay indicated increased IFN-γ and CD8+ T cell levels. In addition, PD-1+ expression was significantly increased as well as the tumor-infiltrating CD45+ leukocytes, indicating a systemic immune response. More recently, they reported Cu-porphyrin MOF for CDT and PDT, along with PD-L1 mediated immunotherapy82. The introduction of CDT into combination therapy synergistically elicited systemic antitumor immunity and enhanced antitumor efficacy against both local and distant tumors. Tian et al.83 prepared ZnFe(CN)5NO Nanosheets labeled with 32P which could generate NO to modulate immunosuppressive and hypoxic tumor microenvironment (Fig. 9C). RT induced ICD of tumor cells and enhanced immune response activation with PD-L1. Moreover, tumor metastases were significantly inhibited by the abscopal effect by radioisotope-immunotherapy.

4.3. Cancer immune biosensing and monitoring

Detection of tumor cells, related antigens, and cytokines offer opportunities for cancer therapy at an early stage and extent patent lives. Many methods have been developed for the diagnosis including surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technology, electrochemical immunoassay, fluorescent immunoassay, colorimetric immunoassay, etc. In general, 2D nanomaterials own high specific surface area and are widely applied to assist this process and improve the sensitivity of detection by target binding enhancement.

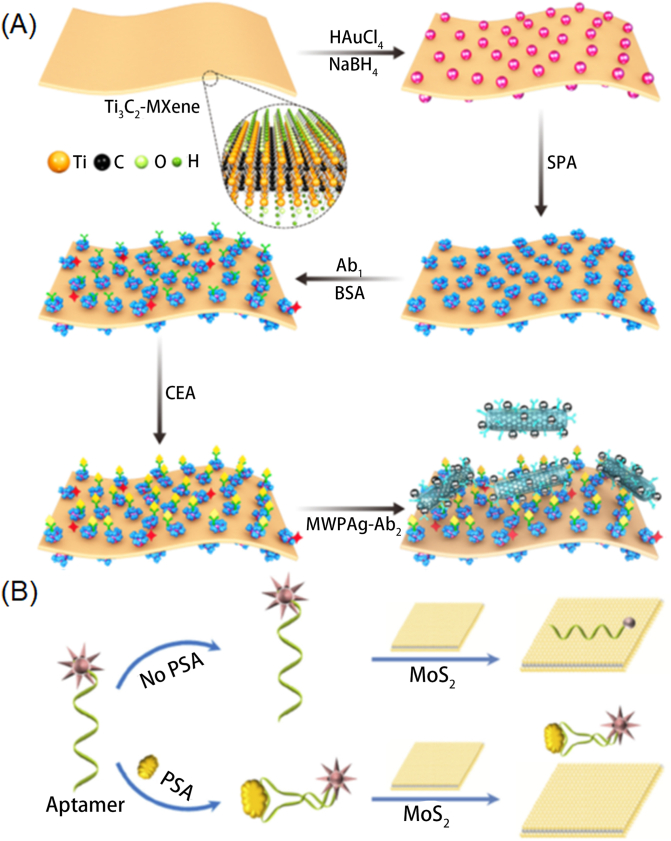

By introducing specific antibodies into nanomaterials, nanomaterials can functionalize as biosensors. For example, Xu et al.84 constructed Ti3C2 MXene derivate which exhibited superior electrical conductivity and was capable of electrochemical immunoassay. Au NPs were deposited on the surface of nanosheets to gain excess binding for Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) antibody and enhance the electrochemical response, which finally attributed to improving the detection sensitivity. The nanocomposite exhibited excellent analytical performance at a low limit of detection (LOD) of 0.03 pg/L against PSA. Chen et al.85 also fabricated Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets to detect PSA at a LOD of 0.31 ng/mL. Nanosheets were functionalized with AuNPs and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and the anti-PSA capture antibody was also immobilized to act as an immunosensor.

Sandwich-type electrochemical immunoassays by different 2D were also widely studied, which holds advantages in the amount of antibody loading. For example, Cai et al.86 designed an ultrasensitive immunosensor by BMIM·BF4-coated SBA-15 coated graphene. HRP was then loaded inside and secondary antibody (Ab2) was conjugated to SBA-15 via a covalent bond. The synergistic effect of BMIM·BF4, HRP, and Ab2 improved the sensitivity of breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA1) detection. The precision assay showed that immunosensor had specific recognition with BRCA1 with a range of 0.01–15 ng/mL and at LOD of 4.86 pg/mL. Wu et al.87 applied Ti3C2 MXene based SPR sensor for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) detection. As presented in Fig. 10A, Ti3C2 MXene was first modified with AuNPs by an in situ reduction of HAuCl4 followed by the attachment of staphylococcal protein A (SPA) to form Ti3C2 MXene/AuNPs/SPA composite. The composite was further mixed with Ag nanoparticles modified carbon nanotube for the immobilization of monoclonal antibody Ab2 via electrostatic interaction. The introduction of Ab2 remarkably enhanced the sensitivity of CEA capture at a LOD of 0.07 fM via antigen–antibody interaction. Li et al.6 combined photonic and ratiometric immunoassay to achieve label-free immune detection. Kong et al.88 developed novel fluorescence biosensor for detection of PSA (Fig. 10B). MoS2 nanosheets were applied to develop fluorescent sensors owing to their role in dye quenchers. Aptamer probe PA was then conjugated to target PSA. Fluorescence quenching rapidly observed at the presence of 0.2–300 ng/mL of PSA, indicating a simple but sensitive detection. Fu et al.89 constructed a sandwich-type immunocomplexes which is formed by GO matrix, antibody modified AuNPs and monoclonal antibody modified magnetic beads. Raman reporter was further conjugated to obtain s SERS signal. Thus, this performed high sensitivity towards AMI disease detection with a limitation of 5 pg/mL. Qin et al.90 applied triethanolamine functionalized MOF with GO or g-C3N4 nanosheets to obtain sandwich type biosensor with a limit detection of 360 fg/mL. Overall, these sandwich type biosensors not only exhibit high capability of antigen loading, but also hold advantages in protecting antibodies from physiological environment. Overall, these sandwich type biosensors not only exhibit high capability of antigen loading, but also hold advantages in protecting antibodies from physiological environment (Table 158, 59, 60, 61,64, 65, 66,69,70,74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82,84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90).

Figure 10.

(A) Detection mechanism of the Mxene-based biosensor. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 87. Copyright © 2019 Elsevier B.V.; (B) Mechanism of monitoring the PSA using MoS2 nanosheet-based biosensor. Reprinted with permission from Ref. 88. Copyright © 2015 Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature.

Table 1.

Summary of 2D nanomaterials and their application in cancer immunotherapy.

| 2D nanomaterial | Advantage | Disadvantage | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO | High loading efficacy, high aspect ratio and surface area | Hard preparation, poor water solubility | Antigen delivery, immune biosensing | 58,59,89 |

| LDH | Good biocompatibility, high payload loading capacity, controllable size, easy and low-cost preparation | Antigen delivery | 60 | |

| Chitosan/calcium phosphate | Easy and low-cost preparation, biocompatible, bioresorbable | Low efficacy of immune response | Antigen delivery | 61 |

| HDL nanodiscs | Safety, long term circulation, prolonged antigen presentation and immune response | Adjuvants and immune modulators delivery | 64,65,66,70 | |

| BP | High photothermal convention efficacy, rapid internalization, biodegradability, biocompatibility, in situ activation of necroptosis | Sensitive to oxygen and water, high bandgap | Immune modulators delivery, PTT, photoimmunotherapy, PDT | 69,74,75,76 |

| Pd nanosheets | High photothermal convention efficiency, controllable size, strong plasmon absorption in NIR | Photoimmunotherapy | 77 | |

| MoS2 | High photothermal convention efficiency, dye quenchers ability, strong NIR photothermal absorption, biocompatibility, water solubility | Difficulty in treatment of metastatic tumor | Photoimmunotherapy, immune biosensing | 78,79,88 |

| MOF | High ROS generation, high capability of antigen loading, structural tunability, synthetic flexibility, biocompatibility, high porosity | Poor stability | Radiotherapy, immunotherapy, radiodynamic therapy, CDT, PDT, immune biosensing | 80,81,82,90 |

| Ti3C2 MXene | Excellent analytical performance, large surface area, high electrical conductivity, significant chemical durability, hydrophilicity, environmentally friendly | Aggregation | Immune biosensing | 84,85,87 |

5. Conclusions and outlooks

2D materials have become a hot topic in the academic field due to their atomic layer thickness, broadband absorption, and ultrafast optical response. With a deep understanding of the biological effects of nanomaterials in the body, we also realize the relationship between nanomaterials and the immune system, and are constantly exploring new methods to regulate the immune response. The rise of 2D nanomaterials has also greatly promoted its application in the field of biomedicine. Therefore, the role between 2D nanomaterials and the immune system needs to be clearly explained, including what factors affect the immune system, and how 2D nanomaterials could be well designed to control the immune response. With these cognitive foundations, the role of 2D nanomaterials in immunotherapy is also very significant. In this review, we first explained that bio-interactions between immune system and nanomaterials, including 2D nanomaterials, affects the immune system, and then specifically explained the factors that affect the immune system/biological safety, and then exemplified some methods to control the immune system. Finally, the combination of 2D nanomaterials and immunotherapy is also well summarized. Although the cognition and application of nan-bio responses are getting deeper and deeper, the combination of 2D nanomaterials and immunity is still in its infancy, with some problems but full of prospects. Before the real clinical translation of 2D nanomaterials-based immunotherapy, there are also still many challenges remained. The specific issues and prospects are as follows:

-

1)

First of all, the current nano-bio effect of 2D nanomaterials in the body is not sufficiently understood when compared to other materials, which required more in-depth researches from proteome level to genome level. The second important point is to realize real-time dynamic observation of the relationship between 2D nanomaterials and the physiological system, especially the immune system. This requires the introduction of ultra-high resolution imaging techniques such as super-resolution imaging technology91 and ultra-fast imaging techniques92.

-

2)

Before real-time dynamic observation, a computational model can also be introduced to simulate the nano-bio reaction between 2D nanomaterials and the immune system in vivo.

-

3)

In addition, if conditions permit, a database can be established, which includes the effects of different 2D nanomaterials of various sizes and various surface chemistry in the body. The established database would not only help scientists from the related fields to understand the nano-bio reaction, but also promoted the potential clinical translation of 2D nanomaterials in cancer immunotherapy.

-

4)

The uniformity, repeatability, and productivity of 2D nanomaterials are huge challenges in the acceleration of clinical translation of 2D nanomaterials in immunotherapy. How to optimize the current synthesis method or introduce other synthesis methods is also a future direction, such as whether it can be combined with microfluidic technology93.

-

5)

For the immunotherapy application, how to achieve high enrichment of 2D nanomaterials in the tumor area is also a long-term problem and another challenge. We can optimize the size or surface chemistry of the material; modify the targeted antibody; select appropriate drug delivery ways to treat corresponding diseases (such as inhaled 2D nanomaterials for immunotherapy of lung cancer, orally delivery of 2D nanomaterials for immunotherapy of stomach cancer94), or can introduce a magnetic field to achieve a certain magnetic targeting effect, or can be wrapped with the cell membrane of the corresponding tumor cells for active targeting95. Not only that, the long-term toxicity and degradability of 2D nanomaterials in the body are also the crucial issues that need attention, as the safety is always the priority before the real applications of used nanomaterials. So, we need conduct much more experiments to detailly understand the pharmacokinetics, toxicity and biodegradation ability of 2D nanomaterials. Moreover, more cell-derived 2D nanomaterials such as the mentioned HDL should be further explored as they maybe more biocompatible, avoid many unwanted immune system responses and easy to degrade in vivo. To further accelerate the clinical translation of 2D nanomaterials-based immunotherapy, maybe the organoid technology96 can be utilized to understand the biocompatibility of designed 2D nanomaterials before the experiments in vivo or even in humans. Also, the immunotherapy efficiency realized by 2D nanomaterials could also be evaluated by organoid technology.

-

6)

The immunotherapy realized by 2D nanomaterials could also be optimized by the integration with other strategies. For example, with the advent of RNA interference therapy97, the combination with immunotherapy has shown great potential in other types of nanomaterials, and it is hoped that 2D nanomaterials can also play a greater role in this direction. Besides, as nowadays photothermal therapy, chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy, gene therapy, radiotherapy et al. have been integrated with immunotherapy via 2D nanomaterials because of their ample physicochemical properties, more new therapies such as starvation therapy98 and chemodynamic therapy99,100 with immunotherapy could also be another promising direction.

-

7)

How to achieve high-resolution monitoring of the treatment process is also a promising and difficult direction. This requires not only the optimization of the existing clinical imaging modes, or the introduction of new imaging technologies such as fluorescence imaging in the near-infrared region101.

-

8)

Although the current types of 2D materials are abundant, the exploration of new 2D materials is also very necessary. For example, 2D MOF nanomaterials or self-assembled 2D peptides nanomaterials may be a research hotspot in the future.

Finally, it is hoped that through theoretical design, structure and component optimization, nanomaterials, including 2D nanomaterials, can be better applied to tumor treatment, especially to play an important role in immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from the US METAvivor Early Career Investigator Award (No. 2018A020560, Wei Tao, USA), Harvard Medical School/Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Anesthesiology-Basic Scientist Grant (No. 2420 BPA075, Wei Tao, USA), and Center for Nanomedicine Research Fund (NO. 2019A014810, Wei Tao, USA). Wei Tao is also a recipient of the Khoury Innovation Award and American Heart Association (AHA) Collaborative Science Award (USA). Junqing Wang was supported by The Hundred Talents Program, China (75110-18841227) from Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China, and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019A1515110326, China). Zhongmin Tang is supported by the China postdoctoral science foundation (2019M663060).

Author contributions

Zhongmin Tang, Yufen Xiao, Junqing Wang, Han Zhang and Wei Tao conceived the idea. Zhongmin Tang, Yufen Xiao, Na Kong, Chuang Liu, Wei Chen, Xiangang Huang, Han Zhang and Wei Tao cowrote the whole manuscript. Daiyun Xu, Jiang Ouyang, Chan Feng and Junqing Wang draw the Scheme, Cong Wang arranged the other Figures and references, and all authors commented on and approved it.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Contributor Information

Junqing Wang, Email: wangjunqing@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Han Zhang, Email: hzhang@szu.edu.cn.

Wei Tao, Email: wtao@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Keibel A., Singh V., Sharma M.C. Inflammation, microenvironment, and the immune system in cancer progression. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:1949–1955. doi: 10.2174/138161209788453167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin J., Cohen B. An overview of the immune system. Lancet. 2001;357:1777–1789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang J., Yu J.X., Hubbard-Lucey V.M., Neftelinov S.T., Hodge J.P., Lin Y. The clinical trial landscape for PD1/PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:854–856. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg M.S. Improving cancer immunotherapy through nanotechnology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:587–602. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L., Wang X., Gong F., Liu T., Liu Z. 2D nanomaterials for cancer theranostic applications. Adv Mater. 2020;32:1902333. doi: 10.1002/adma.201902333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li B.L., Wang J., Gao Z.F., Shi H., Zou H.L., Ariga K., et al. Ratiometric immunoassays built from synergistic photonic absorption of size-diverse semiconducting MoS2 nanostructures. Mater Horiz. 2019;6:563–570. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu S., Pan X., Liu H. Two-dimensional nanomaterials for photothermal therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;132:5943–5953. doi: 10.1002/anie.201911477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novoselov K.S., Geim A.K., Morozov S.V., Jiang D., Zhang Y., Dubonos S.V., et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu M., Liang T., Shi M., Chen H. Graphene-like two-dimensional materials. Chem Rev. 2013;113:3766–3798. doi: 10.1021/cr300263a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgakilas V., Tiwari J.N., Kemp K.C., Perman J.A., Bourlinos A.B., Kim K.S., et al. Noncovalent functionalization of graphene and graphene oxide for energy materials, biosensing, catalytic, and biomedical applications. Chem Rev. 2016;116:5464–5519. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostarelos K. Translating graphene and 2D materials into medicine. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurapati R., Kostarelos K., Prato M., Bianco A. Biomedical uses for 2D materials beyond graphene: current advances and challenges ahead. Adv Mater. 2016;28:6052–6074. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertrand N., Grenier P., Mahmoudi M., Lima E.M., Appel E.A., Dormont F., et al. Mechanistic understanding of in vivo protein corona formation on polymeric nanoparticles and impact on pharmacokinetics. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ke P.C., Lin S., Parak W.J., Davis T.P., Caruso F. A decade of the protein corona. ACS Nano. 2017;11:11773–11776. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson A., Diamond B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:340–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Heredia F.P., Gómez-Martínez S., Marcos A. Obesity, inflammation and the immune system. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71:332–338. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai T., Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julier Z., Park A.J., Briquez P.S., Martino M.M. Promoting tissue regeneration by modulating the immune system. Acta Biomater. 2017;53:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood K.J., Bushell A., Hester J. Regulatory immune cells in transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:417–430. doi: 10.1038/nri3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manicassamy S., Pulendran B. Dendritic cell control of tolerogenic responses. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:206–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pallardy M.J., Turbica I., Biola-Vidamment A. Why the immune system should be concerned by nanomaterials?. Front Immunol. 2017;8:544. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafson H.H., Holt-Casper D., Grainger D.W., Ghandehari H. Nanoparticle uptake: the phagocyte problem. Nano Today. 2015;10:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behzadi S., Serpooshan V., Tao W., Hamaly M.A., Alkawareek M.Y., Dreaden E.C., et al. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: journey inside the cell. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:4218–4244. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00636a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caracciolo G., Farokhzad O.C., Mahmoudi M. Biological identity of nanoparticles in vivo: clinical implications of the protein corona. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hussain S., Vanoirbeek J.A., Hoet P.H. Interactions of nanomaterials with the immune system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2012;4:169–183. doi: 10.1002/wnan.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai R., Ren J., Ji Y., Wang Y., Liu Y., Chen Z., et al. Corona of thorns: the surface chemistry-mediated protein corona perturbs the recognition and immune response of macrophages. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:1997–2008. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b15910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akhavan O., Ghaderi E., Akhavan A. Size-dependent genotoxicity of graphene nanoplatelets in human stem cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8017–8025. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah P., Narayanan T.N., Li C.Z., Alwarappan S. Probing the biocompatibility of MoS2 nanosheets by cytotoxicity assay and electrical impedance spectroscopy. Nanotechnology. 2015;26:315102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/31/315102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T., Chao Y., Gao M., Liang C., Chen Q., Song G., et al. Ultra-small MoS2 nanodots with rapid body clearance for photothermal cancer therapy. Nano Res. 2016;9:3003–3017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao H., Chen W., Laurent S., Thirifays C., Burtea C., Rezaee F., et al. Hard corona composition and cellular toxicities of the graphene sheets. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;109:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y., Hardie J., Zhang X., Rotello V.M. Effects of engineered nanoparticles on the innate immune system. Semin Immunol. 2017;34:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun C., Wakefield D.L., Han Y., Muller D.A., Holowka D.A., Baird B.A., et al. Graphene oxide nanosheets stimulate ruffling and shedding of mammalian cell plasma membranes. Chem. 2016;1:273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teo W.Z., Chng E.L., Sofer Z., Pumera M. Cytotoxicity of exfoliated transition-metal dichalcogenides (MoS2 , WS2 , and WSe2 ) is lower than that of graphene and its analogues. Chemistry. 2014;20:9627–9632. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kong N., Ji X., Wang J., Sun X., Chen G., Fan T., et al. ROS-mediated selective killing effect of black phosphorus: mechanistic understanding and its guidance for safe biomedical applications. Nano Lett. 2020;20:3943–3955. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han M., Zhu L., Mo J., Wei W., Yuan B., Zhao J., et al. Protein corona and immune responses of borophene: a comparison of nanosheet–plasma interface with graphene and phosphorene. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3:4220–4229. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma J., Liu R., Wang X., Liu Q., Chen Y., Valle R.P., et al. Crucial role of lateral size for graphene oxide in activating macrophages and stimulating pro-inflammatory responses in cells and animals. ACS Nano. 2015;9:10498–10515. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Podila R., Shannahan J.H., Rao A.M., Brown J.M. Intravenously delivered graphene nanosheets and multiwalled carbon nanotubes induce site-specific Th2 inflammatory responses via the IL-33/ST2 axis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2013;8:1733–1748. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S44211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mo J., Xie Q., Wei W., Zhao J. Revealing the immune perturbation of black phosphorus nanomaterials to macrophages by understanding the protein corona. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2480. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04873-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orecchioni M., Jasim D., Pescatori M., Sgarrella F., Bedognetti D., Bianco A., et al. Molecular impact of graphene oxide with different shape dimension on human immune cells. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:P217. [Google Scholar]