Abstract

Introduction

The alar ligament is an important structure in restraining the rotational movement at the atlantoaxial joint. While bony fractures generally heal, rupture of ligaments may heal poorly in adults and often requires surgical stabilization. Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation (AARS) is a rare injury in adults, and the prognostic importance of the presence of alar ligament injury with regard to the success of nonoperative management is unknown.

Case presentation

A 28-year-old woman presented after a traumatic Type I AARS without evidence of osseous injury, but MRI demonstrated evidence of unilateral alar ligament disruption. Initial conservative management with closed reduction and maintenance in a rigid cervical collar proved unsuccessful, with worsening pain and failure to maintain reduction. She subsequently underwent open reduction and surgical fixation of C1-C2, resulting in resolution of her pain and maintenance of alignment.

Discussion

Alar ligament rupture may be a negative prognostic indicator in the success of nonoperative management of type I atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation. Additional study is warranted to better assess whether the status of the alar ligament should be considered an important factor in the management algorithm of type I AARS.

Subject terms: Prognosis, Spinal cord, Trauma, Magnetic resonance imaging, Bone imaging

Introduction

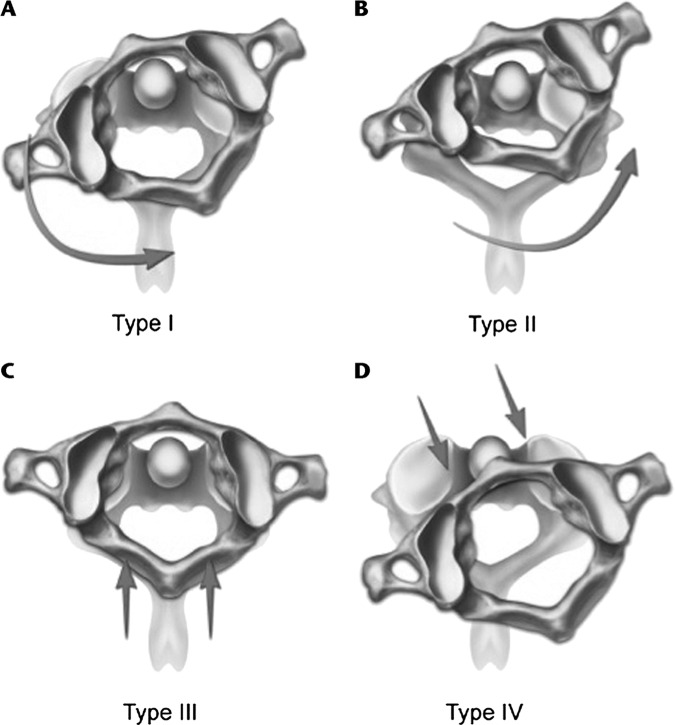

Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation (AARS) is an injury to C1-C2 that may appear with alar ligament, transverse ligament, and facet joint injury secondary to traumatic flexion and rotation [1–3]. These injuries are most commonly seen in pediatric patients because of a larger head size compared to the rest of the body, less developed neck muscles, increased elasticity of ligaments, and more horizontal configuration of the C1-C2 joint [4–6]. In adults, AARS is more commonly seen after high-energy trauma and is more frequently associated with damage to ligamentous structures and a higher risk of neurovascular injury [1]. Fielding and Hawkins described four types of AARS (Fig. 1), with the most common Type I having no horizontal dislocation, Type II and III with increasing atlanto-dental interval (ADI), and Type IV with posterior subluxation of the atlas on the axis [7, 8].

Fig. 1. Fielding and Hawkins Classification of Atlantoaxial Rotatory Subluxation.

A Fielding-Hawkins Type I: C1 is rotated and locked over the C2 without anterior displacement. B Fielding-Hawkins Type II: C1 is rotated over the facet of C2 with 3–5 mm of anterior translation C Fielding-Hawkins Type III: C1 crossing over C2 with more than 5 mm of anterior translation D Fielding-Hawkins Type IV: Rotatory fixation of C1 over C2 with posterior displacement. Reproduced from Kinon et al. 20164 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

AARS is usually diagnosed in adult trauma patients presenting with neck pain with computerized tomography (CT) imaging of the cervical spine [2]. Further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to clarify the extent of ligamentous injury [9]. In adults, AARS is an uncommon injury, with only case reports and case series described in the literature. As such, there is no established consensus for the optimal management strategy for these injuries, and treatment of adult traumatic AARS ranges from closed reduction with a trial of hard cervical orthosis to open surgical fixation or a combination of both. We present a case of adult traumatic AARS and review the current literature, focusing on ligamentous injury diagnosed on MRI and its association with management.

Case presentation

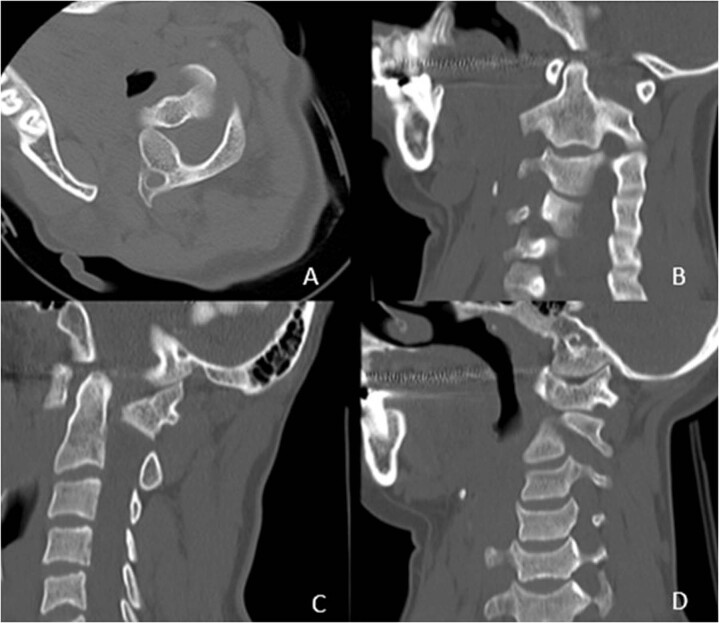

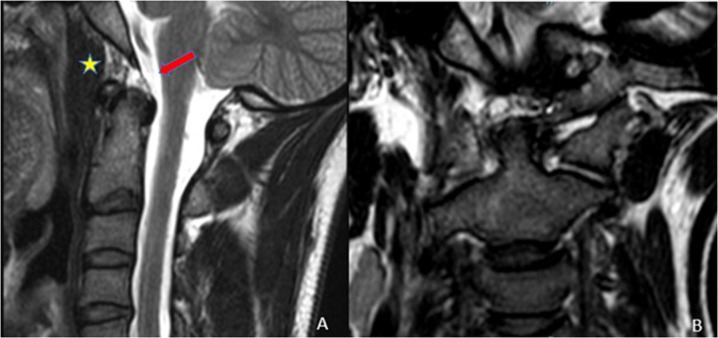

A 28-year-old female with an unremarkable past medical history presented to our institution as a transfer two days after a high-speed motor vehicle collision. She complained of severe neck pain radiating into her head and down into her shoulders with paresthesia into her hands and held her head in an abnormal “cock-robin posture,” turning it down and to the right. She was unable to straighten it. Neurologically, she had a normal exam except for subjective sensory changes in her arms and hands. Cervical spine CT was consistent with AARS Type I, showing rotation of C1 on C2 with the modest posterior translation of the right C1 right lateral mass (Fig. 2). A cervical spine MRI revealed the ligamentous injury in the apical and right alar ligaments, as well as injury in the tectorial membrane, but no compromise of the transverse ligament (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Pre-reduction cervical spine CT showing rotation of C1 on C2 with the modest posterior translation of the right C1 right lateral mass.

A Axial cut, B Coronal cut, C Sagittal cut, D Parasagittal cut.

Fig. 3. Noncontrast MRI of the craniocervical junction.

A Focal discontinuity of the apical ligament (yellow star) and tectorial membrane (red arrow). B Unilateral increased T2 signal in the right alar ligamentous complex compared with the left, suggestive of ligament injury.

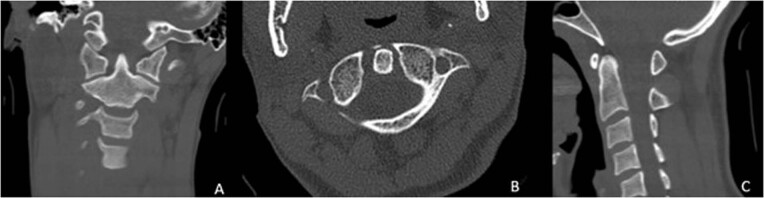

As she had a normal neurological exam and only unilateral ligamentous injury without the involvement of the transverse ligament, conservative management was advised. She was immobilized in a hard cervical collar, and her pain was managed with pain medications and muscle relaxants. Over the next several days, she reduced back into normal alignment, confirmed by a cervical spine CT prior to discharge on hospital day #5 (Fig. 4). The cervical collar was maintained with the intent to determine the length of immobilization based upon the clinical course observed in-office follow-up.

Fig. 4. Cervical CT prior to hospital discharge showing reduction of the AARS.

A Coronal cut, B Axial cut, C Sagittal cut.

Two days after discharge, she returned to the emergency department because of worsening of her neck pain and new-onset headache and dizziness. Repeat x-rays of the cervical spine did not show any significant loss of her reduction. Due to her persistent pain, surgery was offered because this was felt to be due to ligamentous instability. She was taken to the operating room for an open reduction of her AARS and posterior instrumented fusion of C1-C2. After surgery, the patient had significant relief of her neck pain and on the last follow up, her cervical alignment and instrumentation remained stable (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. The patient underwent an uncomplicated C1-C2 posterior instrumented fusion.

Supine cervical spine x-rays. A Lateral, B AP.

Discussion

Adult traumatic AARS is quite rare. After a review of the current literature, we found a total of 19 additional cases of adult AARS which utilized MRI evaluation to guide management (Table 1). We excluded patients that had AARS due to a non-traumatic etiology such as congenital, inflammatory, cancer-related instability, or infectious diagnosis causes [10–14]. The mechanisms of injury included motor vehicle collisions (MVC), falls, positioning injuries, seizure, and sports. Type I AARS was the most common injury, accounting for 80% of cases.

Table 1.

Summary of AARS cases found in the literature.

| Author | Age, Sex | Fielding & Hawkins Classification | Time to Diagnosis (days) | Mechanism | Failed conservative management | Ligamentous Injury | Other Cervical Injury | Treatment | Outcome (Follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castel 2001 [40] | 41 M | 1 | 0 | sports accident | no | none | none | immobilization | no sequelae (12 months) |

| Kim 2007 [30] | 34 M | 2 | 1 | fall down stairs | yes | partial left TL injury | left C2 superior articular facet fx | posterior C1-C2 fixation | no sequelae (12 months) |

| Sinigalia 2008 [23] | 26 F | 1 | 45 | MVC | no | nuchal ligament disruption | none | immobilization | chronic neck pain since injury (10 years) |

| Jeon 2009 [41] | 25 F | 1 | 5 | MVC | no | none | none | immobilization | no sequelae (6 months) |

| Marti 2011 [42] | 24 F | 1 | 1 | stretching | no | none | none | immobilization | neurologically intact during hospitalization |

| Stenson 2011 [43] | 31 F | 1 | 1 | backward fall | no | none | none | immobilization | no neurologic sequelae |

| Dholakia 2012 [44] | 21 F | 1 | 180 | MVC | yes | none | none | C1-C2 open reduction/fusion | no sequelae (3 weeks) |

| Maida 2012 [22] | 27 M | 3 | a few | MVC | no | Type IA TL injury, complete rupture of right AL, partial injury of left AL | none | posterior stabilization of occiput to C3 | no sequelae (60 days, 3 years) |

| Meza Escobar 2012 [45] | 19 F | 1 | 0 | MVC | no | none | none | immobilization | slight persistent AARD (6 weeks) |

| Meng 2014 [28] | 47 F | 4 | - | fall | no | none | Type 2 odontoid fx | posterior C1-C2 fusion | no sequelae (36 months) |

| Min Han 2014 [46] | 22 M | 1 | 0 | MVC | no | none | none | immobilization | no sequelae (1 month, 1 year) |

| Tarantino 2014 [24] | 34 F | 1 | 60 | seizure | yes | hyperintensity of ALs in STIR and T2 sequences | locked left facet | posterior C1–C2 reduction and fixation | no sequelae (1 year) |

| Hawi 2016 [47] | 34 F | 1 | 0 | MVC | no | none | none | immobilization | no sequelae (6 months) |

| Eghbal 2017 [3] | 35 M | 1 | 11 | fall | yes | motion artifact obstruction | none | posterior C1-C2 fusion | no sequalae during post operative course |

| Present Case 2019 | 28 F | 1 | 2 | MVC | yes | AP and right AL injury | none | posterior C1-C2 fusion | no neurologic sequelae (6 months) |

| Eghbal 2018 [20] | 21 M | 1 | 0 | MVC | yes | mild injury of TL | left locked facet | posterior C1-C2 fusion | 30° rotation limitation to each side (6 months) |

| Opoku-Darko 2018 [29] | 20 F | 2 | 0 | MVC | no | none | Type 2 odontoid fx | posterior C1-C2 fusion | no sequelae (1 year) |

| Garcia-Pallero 2019 [31] | 28 F | 1 | 7 | MVC | no | none | none | immobilization | slight neck pain with intense exercise (4 years) |

| Greenberg 2020 [38] | 38 F | 1 | 5 | manipulation | no | none | none | immobilization | no neurologic sequelae |

| Horsfall 2020 [9] | 65 F | 1 | 1 | fall down 10 steps | yes | no injury, thin ligamentum flavum | locked right facet | posterior C1-C2 fusion | no neurologic sequelae (6 months) |

Clinical presentation of adult patients with traumatic AARS frequently includes torticollis and a posterior headache if there is the involvement of the C2 nerve root [2, 3]. There have been reported cases describing vascular insufficiency with ataxia or nystagmus with vertebral artery involvement [3]. Other neurological deficits such as hemiparesis have also been described in the acute period [2, 15]. Given the rarity of the injury in adults, however, a high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis, and delay in diagnosis is thought to increase the risk of becoming irreducible as a result of chronic post-traumatic changes in the joint and soft tissues [14, 16, 17]. Most trauma patients with a suspected cervical spine injury will receive imaging of their cervical spine as part of the trauma evaluation [18, 19]. CT scan of the cervical spine is the preferred initial imaging modality to evaluate for AARS, with MRI being necessary when evaluating for ligamentous injury when there is a high suspicion for this injury since a missed ligamentous injury in a patient with an otherwise negative CT of the cervical spine is potentially devastating [17, 20, 21]. Our recommended indications for obtaining an MRI include increased ADI and instability suggested on CT or flexion-extension studies, persistent pain with conservative management, and neurologic deficit.

The mechanism of injury of AARS is traumatic rotation and flexion of the cervical spine, and it may be associated with additional high cervical injuries [1–3]. In our review of the AARS cases described in the literature with available MRI, a total of 9 patients (45%) had additional cervical injuries. This includes 6 cases (30%) of ligamentous injury, 3 cases (15%) of facet injury, and 3 cases (15%) of osseous injury. Two patients had both ligamentous and facet injuries, while one patient had both osseous and ligamentous injuries.

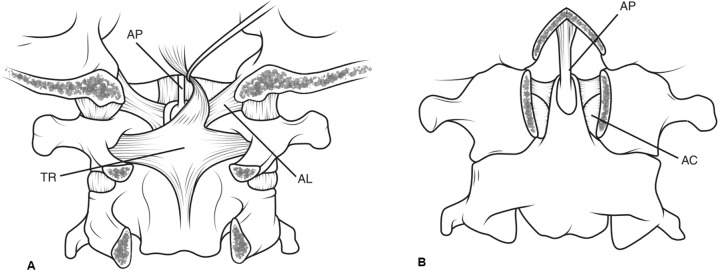

Ligamentous injury

Ligamentous injuries are usually considered unstable and are considered for early surgical stabilization [22]. In our review, six patients of 20 patients (30%) suffered from a ligamentous injury, that included injuries to the transverse, alar, nuchal, and apical ligaments (Fig. 6). Three of the six patients with ligamentous injuries (50%) had evidence of alar ligament involvement on MRI. Two of these patients presented with Type I AARS, one with unilateral alar ligament injury and one with a bilateral alar ligament injury. The third patient had had bilateral alar ligament injury and associated Type 1 A transverse ligament injury classifying it as a Type III AARS injury. Five of the six patients with ligamentous injury were treated (83.3%) surgically [20, 22–24]. All five patients recovered with good outcomes, including improvement/resolution of pain and stable reduction/fusion. Only one patient with isolated ligament injury (nuchal) was treated conservatively with immobilization. However, the patient continued to have chronic neck pain for ten years after her injury [23].

Fig. 6. Illustrations of the atlantoaxial articulation.

A Posterior, B Anterior; (AC Accessory ligament, AL Alar ligament, AP Apical ligament, TR Transverse ligament) Reproduced from Bransford et al. [39] with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

Additional notable injuries were locked facets, which were present in 3 patients. All three patients had Type I AARS and underwent surgical fixation [9, 20, 24]. Locked facet joints require careful manipulation during reduction and evaluation for surgical treatment even if reduced since this type of injury is caused by stretching or disruption of the facet capsule, raising the concern for spinal instability [20].

Osseous injuries

In our review of the literature, the osseous injuries found included fractures of the C2 odontoid processes and the articular process. Three patients had fractures, including two odontoid fractures and 1 C2 superior articular facet fracture. Fractures of C2 involving the odontoid process and the articular processes are rare in patients presenting with AARS, and surgical management is usually recommended if there is a concern for cervical spine instability or non-union of the fracture, such as for Anderson and D’Alonzo type II odontoid fractures [15, 25–27].

Both patients in our series with type II odontoid fractures and AARS were under 50 years old. They did not have evidence of ligamentous injury on MRI but underwent surgical fusion given the concern for non-union and potential spinal instability with nonoperative care, especially in the patients with Type IV AARS [28, 29]. Patients with injury to the C1-C2 facet complex were managed surgically, as injuries to the joints are associated with inherent instability and may not heal well without surgery [28–30]. One patient in our review with AARS had C2 articular facet fractures and underwent C1-C2 fusion [30].

Age

The average age of the patients in the series was 31 years, with elderly patients being rare and where only one patient over the age of 60 is present in the reviewed literature [9]. One reason for the preponderance of younger patients may be that younger adults are more likely to be involved in high-velocity accidents such as motor vehicular trauma. It is not clear how age factors into the decision to provide operative care, but early surgery may be appropriate in those with osteophytic changes that may contribute to poor outcomes if immobilization alone is attempted, as Horsfall et al. described for consideration of performing fusion in a 65-year-old patient with Type I AARS [9].

Management paradigm

Early reduction and rigid immobilization in the acute period are believed to decrease the risk of deformity from the instability of the facet joints [1, 2, 31]. The argument for non-surgical management includes the possibility of preserving C1-C2 motion, a joint that is responsible for 50% of the rotation of the cervical spine [32–34]. Fusion at the C1-C2 joint is associated with loss of motion significant enough to affect the quality of life [33]. A trial of non-surgical management with reduction and immobilization may be appropriate for acute injuries, but for injuries older than one month, chronic changes in the joints and ligaments may have a lower chance of reducing back into anatomic alignment and maintaining their reduction without surgery [17, 24].

The intent of our literature review was to examine which patterns of injury associated with AARS were not amenable to conservative management. Failure of conservative treatment was defined as unsuccessful closed reduction and/or persistent severe pain requiring further treatment, presumptively reflecting instability. Conservative management strategies described in the literature varied in method and duration, from an early attempt at closed reduction under general anesthesia to placement in a hard cervical collar and close follow-up with serial imaging. We encountered no accepted standard practice for the duration of a trial of nonsurgical management to determine if it was successful or not.

In AARS, the surgical procedure of choice is C1-2 fusion to address the instability that develops at the C1-2 joint. Of the patients in our literature search who underwent surgery for AARS, the majority (90%) were treated with C1-2 fusion. Only one patient was treated with occiput to C3 fusion since there was a concern for craniocervical instability due to injury of the transverse and bilateral alar ligaments [22]. In addition to a transverse ligament injury, we believe that disruption of the alar ligament warrants consideration for surgical intervention.

Implications of the Alar ligament in AARS

Three patients (15%), including our patient, had evidence of alar ligament injury on MRI. All of them ultimately underwent surgical treatment. Two patients failed initial conservative management with immobilization and subsequently required surgical fixation/fusion. The third patient had initial successful manual reduction but demonstrated bilateral alar ligament injury and Type IA transverse ligament injury that ultimately had surgical treatment on account of extensive ligamentous disruption and presumed instability.

Since alar ligaments prevent anterior shift and excessive rotation of the atlas, bilateral alar ligament disruption is thought to be a mechanism for producing AARS [23, 35, 36]. Isolated unilateral alar ligament injury rarely occurs, resulting from rotation and/or hyperflexion of the neck. Unal et al. suggest that it may be treated conservatively [37], but this injury subtype has not been thoroughly studied; we believe that its appearance after a high-velocity mechanism of injury is more likely to be unstable and unlikely to heal without surgical intervention. We believe that the illustrative case presented in this communication may reflect that unilateral alar ligament injury is a negative prognostic indicator of the likelihood of successful conservative management of AARS, a hypothesis that may be explored in future studies.

Conclusion

Traumatic AARS is rare in the adult population, and there is no general consensus for the management of adult patients with traumatic AARS who present with a unilateral alar ligament injury. MRI is the modality of choice for visualizing ligamentous injury, and the presence of unilateral alar ligament injury may be a negative prognosticator for the success of nonsurgical management of adult traumatic type I AARS. Further study of the effects of a unilateral alar ligament injury in adult traumatic type I AARS is warranted.

Supplementary information

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41394-021-00464-9.

References

- 1.Meyer C, Eysel P, Stein G. Traumatic atlantoaxial and fracture-related dislocation. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:5297950. doi: 10.1155/2019/5297950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh VK, Singh PK, Balakrishnan SK, Leitao J. Traumatic bilateral atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation mimicking as torticollis in an adult female. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:721–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eghbal K, Derakhshan N, Haghighat A. Ocular manifestation of a cervical spine injury: an adult case of traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation manifesting with nystagmus. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:817.e1–817.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinon MD, Nasser R, Nakhla J, Desai R, Moreno JR, Yassari R, et al. Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation: a review for the pediatric emergency physician. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:710–6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Missori P, Marruzzo D, Peschillo S, Domenicucci M. Clinical remarks on acute post-traumatic atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation in pediatric-aged patients. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:e645–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kombogiorgas D, Hussain I, Sgouros S. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation caused by spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage in a child. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1182–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fielding JW, Stillwell WT, Chynn KY, Spyropoulos EC. Use of computed tomography for the diagnosis of atlanto-axial rotatory fixation. A case report. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1978;60:1102–4. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197860080-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielding JW, Hawkins RJ. Atlanto-axial rotatory fixation. (Fixed rotatory subluxation of the atlanto-axial joint) J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1977;59:37–44. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197759010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horsfall HL, Gharooni A-A, Al-Mousa A, Shtaya A, Pereira E. Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation in adults - A case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2020;11:376. doi: 10.25259/SNI_671_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bapat MR, Gujral A, Patel BK. Congenital unilateral atlanto-occipital rotatory subluxation: rare cause of C1 neuralgia. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 2018;43:E1426–E1428. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khazim R, Makki D, Waheed A, Aslam M, Dasgupta B. Combined rotatory and lateral atlanto-axial subluxation in rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. J Bone Spine. 2009;76:112–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabib W, Sayegh S, Colona d’Istria F, Meyer M. Atlanto-axial Pott’s disease. Apropos of a case with review of the literature. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1994;80:734–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonomura Y, Kataoka H, Sugie K, Hirabayashi H, Nakase H, Ueno S. Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation associated with cervical dystonia. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 2007;32:E561–4. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318145ac12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elsissy J, Cheng W, Kutzner A, Danisa O. A 30-year-old male with delayed diagnosis and management of chronic post-traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation. J Orthop Case Rep. 2019;9:23–5. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spoor AB, Diekerhof CH, Bonnet M, Oner FC. Traumatic complex dislocation of the atlanto-axial joint with odontoid and C2 superior articular facet fracture. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 2008;33:E708–711. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817c140d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahimizadeh A, Williamson W, Rahimizadeh S. Traumatic chronic irreducible atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in adults: review of the literature, with two new examples. Int J Spine Surg. 2019;13:350–60. doi: 10.14444/6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barimani B, Fairag R, Abduljabbar F, Aoude A, Santaguida C, Ouellet J, et al. A missed traumatic atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation in an adult patient: case report. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019;11:39–42. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S149296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, Clement CM, Lesiuk H, De Maio VJ, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1841–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman JR, Wolfson AB, Todd K, Mower WR. Selective cervical spine radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:461–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eghbal K, Rakhsha A, Saffarrian A, Rahmanian A, Abdollahpour HR, Ghaffarpasand F. Surgical management of adult traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation with unilateral locked facet; case report and literature review. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2018;6:367–71. doi: 10.29252/beat-060416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fennessy J, Wick J, Scott F, Roberto R, Javidan Y, Klineberg E. The utility of magnetic resonance imaging for detecting unstable cervical spine injuries in the neurologically intact traumatized patient following negative computed tomography imaging. Int J Spine Surg. 2020;14:901–7. doi: 10.14444/7138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maida G, Marcati E, Sarubbo S. Posttraumatic atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation in a healthy adult patient: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:183581. doi: 10.1155/2012/183581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinigaglia R, Bundy A, Monterumici DAF. Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation in adults. Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2008;73:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarantino R, Donnarumma P, Marotta N, Missori P, Viozzi I, Landi A, et al. Atlanto axial rotatory dislocation in adults: a rare complication of an epileptic seizure_case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2014;54:413–6. doi: 10.2176/nmc.cr2012-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellil M, Hadhri K, Sridi M, Kooli M. Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation associated with C2 articular facet fracture in adult patient: case report. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2014;5:163–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-8237.147083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson LD, D’Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1974;56:1663–74. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197456080-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryken TC, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Hurlbert RJ, et al. Management of isolated fractures of the axis in adults. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:132–50. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318276ee40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meng H, Gao Y, Li M, Luo Z, Du J. Posterior atlantoaxial dislocation complicating odontoid fracture without neurologic deficit: a case report and review of the literature. Skelet Radio. 2014;43:1001–6. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opoku-Darko M, Isaacs A, du Plessis S. Closed reduction of traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation with type II odontoid fracture. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2018;11:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.inat.2017.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim Y-S, Lee J-K, Moon S-J, Kim S-H. Post-traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in an adult: a case report. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 2007;32:E682–7. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cf55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.García-Pallero MA, Torres CV, Delgado-Fernández J, Sola RG. Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in an adult patient. Eur Spine J. 2019;28:284–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4916-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang D-G, Park J-B, Jang H-J. Traumatic C1-2 rotatory subluxation with dens and bilateral articular facet fractures of C2: A case report. Med (Baltim) 2018;97:e0189. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen K, Deng Z, Yang J, Liu C, Zhang R. Novel posterior artificial atlanto-odontoid joint for atlantoaxial instability: a biomechanical study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28:459–66. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.SPINE17475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo Q, Deng Y, Wang J, Wang L, Lu X, Guo X, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes of posterior C1-C2 temporary fixation without fusion and C1-C2 fusion for fresh odontoid fractures. Neurosurgery. 2016;78:77–83. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willauschus WG, Kladny B, Beyer WF, Glückert K, Arnold H, Scheithauer R. Lesions of the alar ligaments. In vivo and in vitro studies with magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 1995;20:2493–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niibayashi H. Atlantoaxial rotatory dislocation. a case report. Spine (Philos Pa 1976) 1998;23:1494–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199807010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unal TC, Dolas I, Unal OF. Unilateral alar ligament injury: diagnostic, clinical, and biomechanical features. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e878–e884. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenberg MR, Forgeon JL, Kurth LM, Barraco RD, Parikh PM. Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation presenting as acute torticollis after mild trauma. Radio Case Rep. 2020;15:2112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bransford RJ, Alton TB, Patel AR, Bellabarba C. Upper cervical spine trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:718–29. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-11-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castel E, Benazet JP, Samaha C, Charlot N, Morin O, Saillant G. Delayed closed reduction of rotatory atlantoaxial dislocation in an adult. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:449–53. doi: 10.1007/s005860000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon SW, Jeong JH, Moon SM, Choi SK. Atlantoaxial rotatory fixation in adults patient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45:246–8. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.45.4.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marti JJ, Zalacain JF, Houry DE, Isakov AP. A 24-year-old woman with neck pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:473.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stenson D. Diagnosis of acute atlanto-axial rotatory fixation in adults. Radiography. 2011;17:165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2010.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dholakia A, Broyer Z, Conliffe T, Mandel S. Post-traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory Fixation in an adult Presenting as torticollis. Practical Neurology. Published online 2012.

- 45.Meza Escobar LE, Osterhoff G, Ossendorf C, Wanner GA, Simmen H-P, Werner CM. Traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation in an adolescent: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Min Han Z, Nagao N, Sakakibara T, Akeda K, Matsubara T, Sudo A, et al. Adult traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory fixation: a case report. Case Rep Orthop. 2014;2014:593621. doi: 10.1155/2014/593621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawi N, Alfke D, Liodakis E, Omar M, Krettek C, Müller CW, et al. Case report of a traumatic atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation with bilateral locked cervical facets: management, treatment, and outcome. Case Rep Orthop. 2016;2016:7308653. doi: 10.1155/2016/7308653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.