Abstract

Background

Since its inception in late 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has been evolving continuously by procuring mutations, leading to emergence of numerous variants, causing second wave of pandemic in many countries including India in 2021. To control this pandemic continuous mutational surveillance and genomic epidemiology of circulating strains is very important to unveil the emergence of the novel variants and also monitor the evolution of existing variants.

Methods

SARS-CoV-2 sequences were retrieved from GISAID database. Sequence alignment was performed with MAFT version 7. Phylogenetic tree was constructed by using MEGA (version X) and UShER.

Results

In this study, we reported the emergence of a novel variant of SARS-CoV-2, named B.1.1.526, in India. This novel variant encompasses 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains which are characterized by the presence of 11 coexisting mutations including D614G, P681H, and V1230L in S glycoprotein. Out of these 129 sequences, 27 sequences also harbored E484K mutation in S glycoprotein. Phylogenetic analysis revealed strains of this novel variant emerged from the GR clade and formed a new cluster. Geographical distribution showed, out of 129 sequences, 126 were found in seven different states of India. Rest 3 sequences were observed in USA. Temporal analysis revealed this novel variant was first collected from Kolkata district of West Bengal, India.

Conclusions

The D614G, P618H and E484K mutations have previously been reported to favor increased transmissibility, enhanced infectivity, and immune invasion, respectively. The transmembrane domain (TM) of S2 subunit anchors S glycoprotein to the virus envelope. The V1230L mutation, present within the TM domain of S glycoprotein, might strengthen the interaction of S glycoprotein with the viral envelope and increase S glycoprotein deposition to the virion, resulting in more infectious virion. Therefore, the new variant having D614G, P618H, V1230L, and E484K may have higher infectivity, transmissibility, and immune invasion characteristics, and thus need to be monitored closely.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, B.1.1.526, V1230L, West Bengal

Introduction

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, in December 2019, the virus has continuously been evolving by acquiring mutations throughout the genome with the progression of the pandemic [1]. Continuous efforts are being made towards SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing and genomic epidemiology to investigate the virus evolution, their pathogenic potential, and transmission. Gradual accumulation of mutation within the genome resulted in the delineation of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains into different clades (L, S, O, V, G, GH, GR, GV, and GRY according to GISAID nomenclature), lineages, and sublineages [2]. Special attention is given to the mutations which have evolved within the S glycoprotein due to their influence in host cell receptor binding and entry, immune invasion, and antibody neutralization [3]. Not surprisingly, most of the new mutations have been observed within the S glycoprotein, which could provide fitness advantage in terms of enhanced infectivity, transmissibility, immune invasion or antibody neutralization [4].

The D614G, the first mutation emerged within the S glycoprotein, has been shown to be responsible for better infectivity and transmissibility of the virus [[5], [6], [7]]. This mutation has become the part of all Variants of Concern (VOCs), Variants of Interest (VOIs), and Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs). Currently, there are four VOC namely the Alpha variant/B.1.1.7 (originated in United Kingdom from the GR clade), the Beta variant/B.1.351 (originated in South African from the GH clade), the Gamma variant/P.1 (originated in Brazil from the GR clade), and the Delta variant/B.1.617.2 (originated in India from the G clade). VOI mainly includes the Lambda variant/C.37 (originated in Peru from the GR clade) and the Mu variant/B.1.1.621 (originated in Colombia from the GH clade). Currently designated VUMs include AZ.5 (earliest documentation in multiple countries, evolved from the GR clade), C.1.2 (originated in South Africa from the GR clade), B.1.617.1/Kappa (originated in India from the G clade), B.1.525/Eta (earliest documentation in multiple countries, evolved from the G clade), B.1.526/Iota (originated in USA from the GH clade), and B.1.630 (originated in Dominican Republic from the GH clade) (https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/). Along with the clade specific mutations, these variants have their own sets of characteristics mutations including several mutations in the S glycoprotein like Δ69–70, Δ144–145, N501Y, A570D, P681H, T716I, S982A, D1118H in the Alpha variant; D80A, D215G, Δ241–243, K417N, E484K, N501Y, A701V in the Beta variant; L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, H655Y, T1027I in the Gamma variant; and T19R, E156G, Δ157-158, L452R, T478K, P681R, D950N in the Delta variant [4,[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]].

India has witnessed the emergence of two new variants namely B.1.617, first detected in Maharashtra on 5th October 2020, and B.1.618, first detected in West Bengal on 25th October. B.1.617 is characterized by the S glycoprotein mutations L452R, D614G, and P681R [[14], [15], [16]]. It has three sublineages B.1.617.1/Kappa (S protein mutations: T95I, G142D, E154K, L452R, E484Q, D614G, P681R and Q1071H), B.1.617.2/Delta (S protein mutations: T19R, E156G, Δ157-158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N), and B.1.617.3 (S glycoprotein mutations: T19R, G142D, L452R, E484Q, D614G, P681R and D950N) (https://www.cdc.gov). Among these three sublineages, B.1.617.3 was first detected in October 2020. However, its prevalence remained very low compared to the other two sublineages B.1.617.1 and B.1.617.2, both of which were first identified in December 2020. Frequency of B.1.617 (all sublineages) started to rise significantly in February 2021, resulting in devastating second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in India [14]. Spread of this variant outside India was first reported from UK, USA and Singapore in late February 2021. By 13 May 2020, this variant has been detected in about 60 countries with more than 4500 confirmed cases. On 7 May 2020, Public Health Authorities of England declared B.1.617.2 as VOC. On 11 May, WHO also recommended this variant as VOC under the name VOC-21ARP-02 based on evidences that this variant is at least as transmissible as the UK variant and less sensitive to antibody neutralization. Currently, this variant has spread to around 147 countries and became the dominant clade globally. The second Indian variant, B.1.618, also known as triple mutant, has four mutations ΔH146, ΔY147, E484K, and D614G in the S glycoprotein. Members of this lineage have also been found to spread in other countries like USA, Singapore, Switzerland, and Finland [16].

In the current scenario, tracking new mutations within these newly emerged variants as well as investigating the emergence of new variants is crucial to take necessary preventive measures for effective public health responses. With the aim of tracing new mutations within the circulating SAR-CoV-2 strains in India during August 2020 to October 2021, we have identified the emergence of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage named B.1.1.526. This new variant is characterized by the presence of 12 co-existing mutations including E484K, D614G, P681H, and V1230L in the S glycoprotein.

Materials and methods

Sequence retrieval

High coverage full genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 strains (n = 8592), collected during August 2020 to October 2021 from India, were retrieved from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) on 9th November 2021 [17]. The genome sequences of the prototype SARS-CoV-2 strain hCoV-19/Wuhan/WIV04/2019 (GISAID accession no. EPI_ISL_402124) and several clades/variants were also downloaded from the GISAID database for the purpose of mutational analysis and construction of the phylogenetic tree.

Screening of mutations

We have performed non-synonymous mutational analysis of 25 proteins (NSP1–NSP16, S glycoprotein, NS3, E, M, NS6, NS7a, NS7b, NS8, and N) encoded by each of the 8592 SARS-CoV-2 strains collected during August 2020 to October 2021 from India. For performing mutational analysis of a specific protein, the coding region of that protein of 8592 SARS-CoV-2 genomes as well as prototype genome (hCoV-19/Wuhan/WIV04/2019) were translated to amino acid sequences by using TRANSEQ nucleotide-to-protein sequence conversion tool (EMBL-EBI, Cambridgeshire, UK). Next, the protein sequences (specific for a single protein) of 8592 SARS-CoV-2 strains and the prototype strain were aligned by using MEGA software (Version X) and observed for amino acid substitutions in the circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains with compared to the prototype strain [18]. The amino acid substitution observed at a particular location of a specific protein of the circulating strain was marked with the number according to its position with compared to the first amino acid (which was considered as 1) of that specific protein of the prototype strain.

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic dendrogram was constructed based on the whole genome sequences of 111 SARS-CoV-2 strains, including 38 high coverage sequences of the new variant and 73 reference sequences of different clades/variants (11 reference sequences of Indian variant B.1.617; 5 reference sequences of each of G clade, GR clade, GV clade, L clade, V clade, GRY clade/UK variant, South African variant, Brazilian variant, California variant, Nigerian variant, and Indian variant B.1.618; 4 reference sequences of S clade; 3 reference sequences of GH clade), using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) version X [19]. Initially, genome sequences of 111 SARS-CoV-2 strains were aligned by multiple alignment program MAFT version 7 [20]. The alignment file was then used to build phylogenetic tree by maximum-likelihood method using general time reversal (GTR) statistical model with 1000 bootstrap replicates [18]. We also performed the phylogenetic analysis of the 129 sequences of the new variant with the Ultafast Sample Placement of Existing Trees (UShER) that has been integrated in the UCSC SARS-CoV-2 Genome Browser [21]. We accessed to the UCSC SARS-CoV-2 Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgPhyloPlace) and uploaded the sequence IDs of 129 sequences (Table S1) for the construction of the phylogenetic tree. UShER is a program that rapidly places new samples onto an existing phylogeny using maximum parsimony. It is particularly helpful in understanding the relationships of newly sequenced SARS-CoV-2 genomes with each other and with previously sequenced genomes in a global phylogeny.

Results

Identification of SARS-CoV-2 strains harboring new set of coexisting mutations

By performing the whole genome mutational analysis of 8592 SARS-CoV-2 strains collected during August 2020 to October 2021 from India, we identified 126 SARS-CoV-2 strains having new set of 11 coexisting mutations among 7 different genes: D279N and L353F in NSP4; V26F in NSP8; P323L in NSP12; D614G, P681H and V1230L in S glycoprotein; G172C in NS3; V62L in NS8; and R203K and G204R in N gene. Table 1 is representing the 11 coexisting mutations associated with the seven different genes. We also searched for SARS-CoV-2 strains having this new set of coexisting mutation in other part of the world. Outside India, only 3 SARS-CoV-2 strains of this new variant were found in USA. Therefore, in total, 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains with 11 coexisting mutations were identified. Interestingly, among 129 sequences, 27 sequences also harbored E484K mutation along with D614G, P681H and V1230L in the S glycoprotein. Table S1 is representing the names of 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains along with all the amino acid substitutions present within their genomes, including the 11 coexisting mutations.

Table 1.

List of coexisting non-synonymous mutations present within the different proteins of the 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains.

| Gene name | Mutation(s) |

|---|---|

| NSP4 | D279N, L353F |

| NSP8 | V26F |

| NSP12 | P323L |

| Spike protein | D614G, P681H, V1230L, ±E484K |

| NS3 | G172C |

| NS8 | V62L |

| N | R203K, G204R |

In addition to 12 coexisting mutations including E484K, 186 different mutations were also found throughout the genome of these 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains. Among these 186 mutations, 36 were found in NSP3, 29 were found in S glycoprotein, 20 were found in NSP2, 17 were found in NS3, 10 were found in N, 9 were found in both NSP6 and NS8, 7 were found in both NSP14 and NSP16, 6 were found in both NSP5 and NSP15, 4 were found in each of NSP4, NSP9, NSP12, and NS7a, 3 were found in both NSP13 and E, 2 were found in each of NSP8, M, and NS6, and single mutation was found in each of NSP1 and NSP7. No mutation was observed in NSP10, NSP11, and NS7b (Table 2 , Table S1). Among 186 different mutations, Q18stop mutation in NS8 protein was found to occur with highest frequency (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of amino acid changes, excluding the 11 coexisting mutations, found within the different proteins of 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains.

| Gene name | Mutation(s) with frequency |

|---|---|

| NSP1: | R119H (1) |

| NSP2: | V94L (3), P129S (1), Q134K (5), T153M (1), A174T (1), S196L (1), R222C (2), I224T (1), G265C (1), I273T (2), A318S (3), Q383R (2), S430A (2), W450C (1), L451F (1), A476V (1), V480D (1), P589S (1), V594F (1), P597S (1) |

| NSP3: | G132D (1), D135Y (1), A150V (2), P153L (1), M196I (1), L198F (1), T217I (1), G277R (1), P340L (1), V477F (1), K525R (2), S609I (1), A614V (2), L620F (3), L689G (1), A690V (1), T724I (1), P822S (11), M829V (1), A861S (2), T936I (1), T1004I (1), P1044S (1), V1048I (2), T1184M (1), T1189I (3), L1259F (2), N1263T (1), P1292S (1), T1335I (7), L1137F (1), T1348I (1), T1379I (3), C1392F (1), A1711V (1), M1788T (1) |

| NSP4: | H31Y (1), V210I (1), L264F (1), T295I (1) |

| NSP5: | L58F (1), K90R (3), Y126stop (1), A129V (2), T196M (9), S284G (1) |

| NSP6: | L37F (2), S106F (2), K109N (7), S118L (3), V149F (8), F184V (1), V190F (1), I273T (1), G277S (2) |

| NSP7: | T45I (1) |

| NSP8: | P133S (1), T148I (1) |

| NSP9: | T24I (1), G38S (1), R39G (1), P71S (7) |

| NSP12: | L49I (1), K91R (2), V435I (1), E919D (1) |

| NSP13: | H290Y (1), A296S (1), T481M (1) |

| NSP14: | G44C (1), V125F (1), T131I (1), L152I (3), A274S (1), P297S (1), P393S (1) |

| NSP15: | A81V (1), A171V (1), S261L (2), S288Y (2), D300N (1), M330T (1) |

| NSP16: | A34V (1), P80A (1), T91M (1), L126F (1), T151I (1), K160R (2), K182N (1) |

| Spike protein: | L5F (1), P26S (2), H49Y (1), L54F (1), G72R (1), E156G (1), E157del (1), E158 del (1), Q173H (2), G184V (2), V213L (1), A243del (1), L244del (1), W258S (2), V382L (1), P384L (1), E583Q (1), I587S (1), V622F (1), Q675H (1), T681A (1), A845S (1), Q913H (2), V952F (1), V1104I (2), I1130M (1), K1181N (2), K1191N (1), L1200F (2) |

| NS3: | T9K (1), G11R (2), S26L (1), L53F (1), K67N (1), H78Y (1), A110V (1), V112I (1), C133F (1), V163L (1), D201Y (1), Q213K (1), P240S (1), G251C (1), V256F (1), P262S (1), D265Y (1) |

| E: | T9I (2), S60T (2), V62F (2) |

| M: | S4F (1), I76M (1) |

| NS6: | T21I (1), W27L (1) |

| NS7a: | G38V (1), T39I (2), P84L (1), Q90R (1) |

| NS8: | T11I (9), A15V (2), Q18stop (20), P36S (1), W45L (1), R52I (1), S67F (6), L95F (1), C102F (1) |

| N: | P13L (3), G30R (2), A35V (1), P122L (1), D128Y (1), D128H (1), D144G (1), A152V (1), P279L (1), D402H (1) |

Phylogenetic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 strains: classification as new Pango lineage B.1.1.526

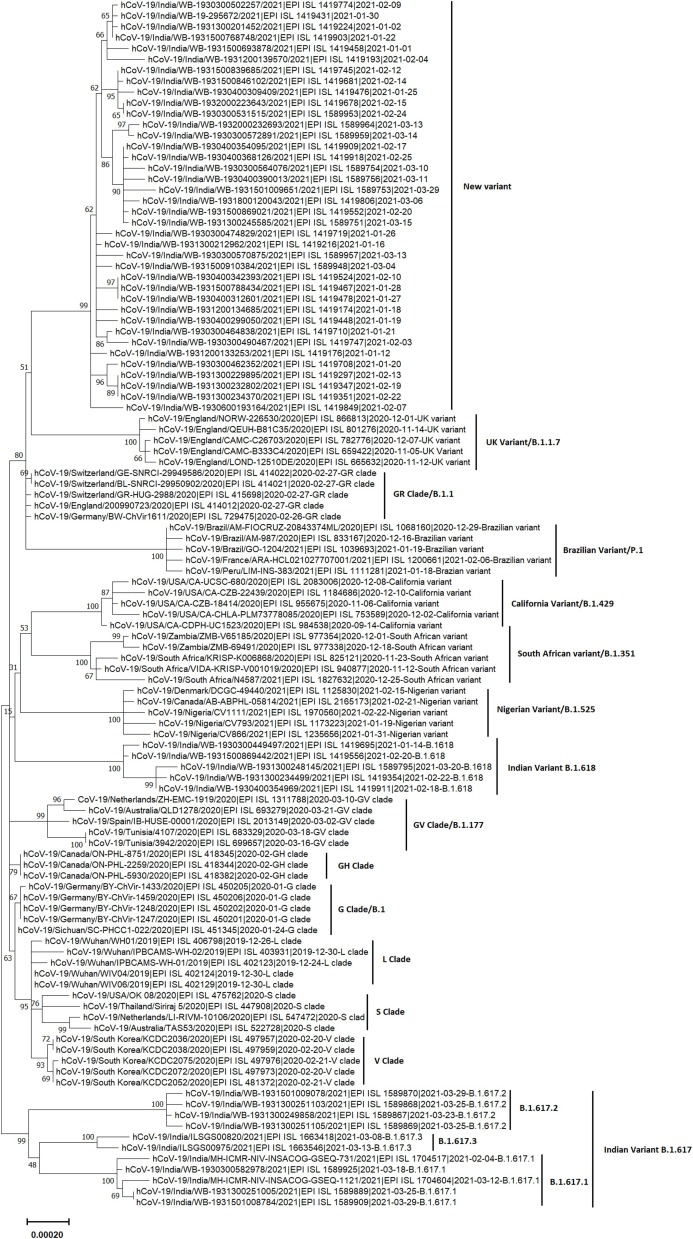

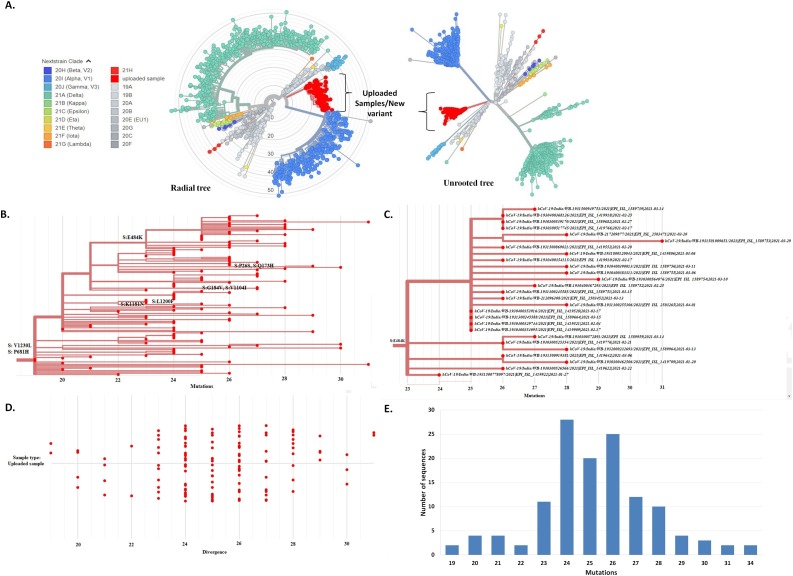

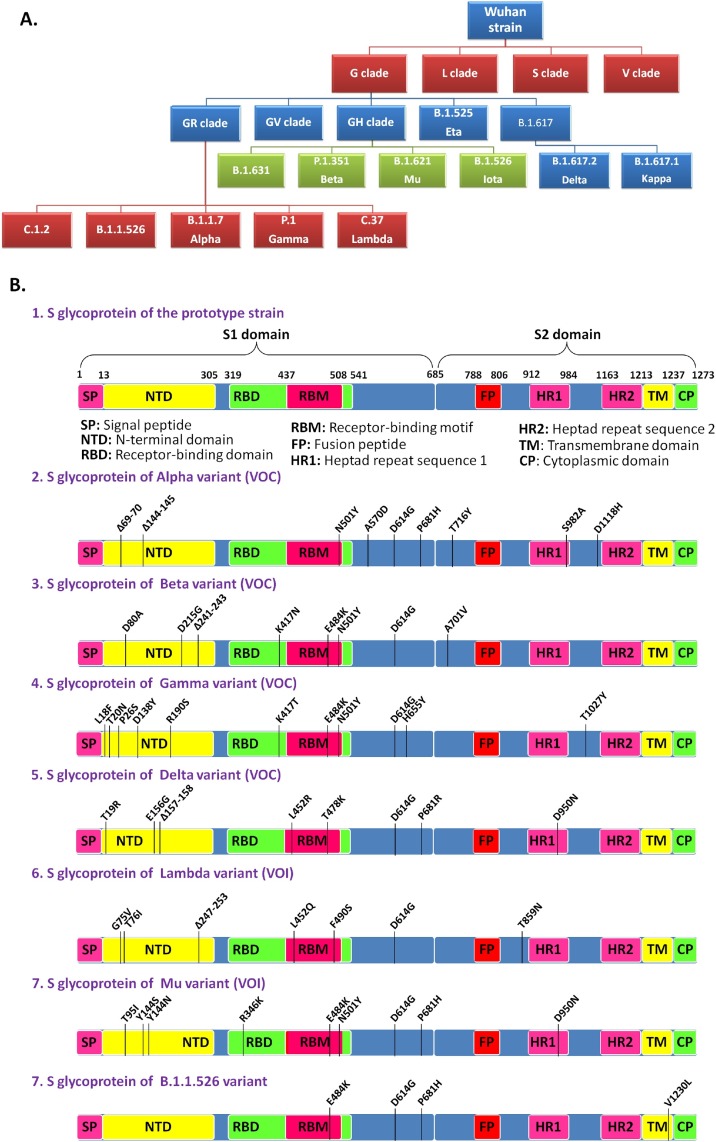

Phylogenetic analysis of 38 representative genomes of the new variant along with 73 reference genomes of different clades/variants by MEGA X revealed that genomes of this new variant formed a novel cluster that emerged from the GR clade (B.1.1) which is characterized by four coexisting signature mutations: D614G in S glycoprotein, P323L in NSP12, and R203K and G204R in N protein (Fig. 1 ). Consistent with this result, the placement of all the 129 genomes of the new variant within the already existing phylogenetic tree of 1127 SARS-CoV-2 genomes of different clades by UShER also revealed a new cluster, that encompasses the 129 sequences of the new variant, within the 20B clade (GR clade) (Fig. 2 A, https://nextstrain.org/fetch/genome.ucsc.edu/trash/ct/singleSubtreeAuspice_genome_3511c_b706f0.json?l=radial). This novel cluster has evolved from the GR clade by acquiring S glycoprotein mutations V1230L and P681H, and has been depicted in Fig. 2B. Among 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains, 27 strains with additional S: E484K mutation also formed a sub-cluster that was presented in Fig. 2C. Fig. 2D and 2E represented divergence graphs showing frequency of the new variants harboring varying number of mutations. This new variant was named as Pangolin lineage B.1.1.526 by Github in response to our new lineage proposal (https://github.com/cov-lineages/pango-designation/issues/91) and has also been incorporated into the GISAID database. A schematic diagram illustrating the evolution of various clades/lineages including B.1.1.526 from their parent clade was shown in Fig. 3 A. and S glycoprotein mutations of the 4 VOCs, 2 VOIs, and B.1.1.526 were depicted in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 1.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the new variant by MEGA X using maximum-likelihood method. The phylogenetic dendrogram is based on whole genome sequences of 38 representative strains of the new variant and 73 reference strains of 16 clades/variants. The scale bar represents 0.00020 nucleotide substitution per site. The best-fit model used for constructing the phylogenetic dendrogram was the general time-reversal model (GTR).

Fig. 2.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the new variant by UShER. (A) The phylogenetic tree (both Radial and Unrooted) depicting the position of 129 strains of the new variant (labelled as uploaded sample/new variant, red color) within the 1127 SARS-CoV-2 strains of different clades or variants. Each color is representing a different clade/lineage. (B) The branch of phylogenetic tree (made by UShER) containing 129 strains of the new variant (B1.1.526). (C) The sub-branch of the new lineage (B.1.1.526) illustrating 27 strains with additional S: E484K mutation. (D) The divergence tree of 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains of the novel lineage B.1.1526. (E) Frequency distribution of SARS-CoV-2 strains of the novel lineage B.1.1.526 harboring varying numbers of coexisting mutations.

Fig. 3.

The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 strains. (A) A schematic presentation illustrating the evolution of various clades/lineages including B.1.1.526. (B) A schematic illustration of S glycoprotein mutations found within the prototype strain, VOCs (Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta), VOIs (Lambda and Mu), and B.1.1.526.

Geographical and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 strains of the new Pango lineage B.1.1.526

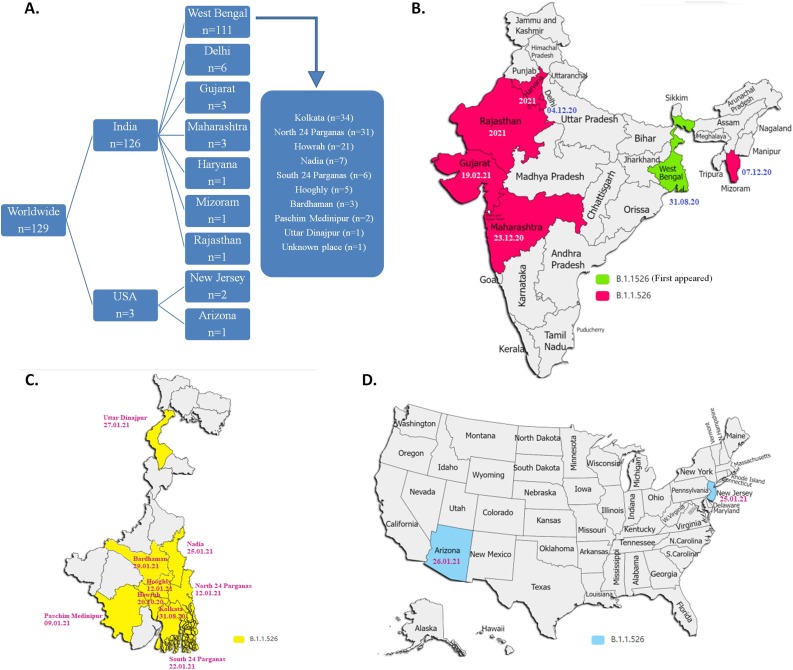

Among the 129 strains of the lineage B.1.1.526, 126 strains were collected from COVID-19 patients in India and 3 strains were collected from USA. One hundred twenty six SARS-CoV-2 strains were found to be distributed among 7 different states of India: West Bengal (n = 111), Delhi (n = 6), Maharashtra (n = 3), Gujarat (n = 3), Haryana (n = 1), Mizoram (n = 1), and Rajasthan (n = 1). In West Bengal, the lineage B.1.1.526 was observed in 9 different districts: Kolkata (n = 34), North 24 Parganas (n = 31), Howrah (n = 21), Nadia (n = 7), South 24 Parganas (n = 6), Hooghly (n = 5), Bardhaman (n = 3), Paschim Medinipur (n = 2), and Uttar Dinajpur (n = 1). Three strains, observed outside India, were collected from New Jersey (n = 2) and Arizona (n = 1) in USA. (Fig. 4 A). Temporal analysis revealed that the strain of lineage B.1.1.526 was first collected from Kolkata in West Bengal, India on 31st August 2020, following which it has spread to various districts of West Bengal during October 2020 to January 2021. The first strain of this new variant was isolated from Maharashtra, Delhi, and Mizoram on December 2020, and from Gujarat, Haryana, and Rajasthan in early 2021 (Fig. 4B and 4C). The first incidence of B.1.1.526 was found in USA on 25th January 2021 in New Jersey (Fig. 4D). Due to lack of metadata in GISAID, it was difficult to predict the association of three USA cases to India.

Fig. 4.

Geographical and temporal distribution of B.1.1.526 lineage. (A) Frequency distribution of 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains of the novel lineage B.1.1.526 in different geographic regions. (B) The geographic map of India highlights 7 different states (marked with green and red color) where the novel lineage was observed. The first date of isolation of the novel strain was also mentioned. (C) The geographic map of West Bengal state of India, showing 9 different districts (marked with yellow colour) where the novel lineage was found. (D) The geographic map of USA, highlighting 2 different states (marked with sky blue) where B.1.1.526 was found to spread.

Discussion

Emergence of new mutations in the S glycoprotein, which is involved in the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and entry into the host cell, could have influence on virus binding, entry, immune invasion, and antibody neutralization. Since the first emergence in December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 has acquired numerous mutations in the S glycoprotein that gave special adaptive advantages to the virus and play key role in the virus evolution so far. D614G, the first mutation appeared in the S glycoprotein, was detected in Germany in January 2020 and became the dominant mutation in all the circulating strains worldwide by June 2020 [5]. Now, it is present in all the circulating strains including all the VOC, VOI, and VUM [4,22]. Patients infected with the D614G mutant had higher nasopharyngeal viral RNA loads, indicating its role in increased infectivity [5]. Wet lab experiments confirmed that the D614G mutation enhances virus replication in human lung epithelial cells and primary human airway tissues by increasing the infectivity and stability of the virions. Hamster infected with the D614G variant produces higher infectious virus titers in nasal washes and the trachea, supporting the role of D614G mutation in high transmissibility. It has also been demonstrated that D614G mutation confers higher susceptibility to serum neutralization [23]. Another study showed that pseudovirus particles carrying S-G614 enter ACE2 overexpressing cells more efficiently than those with S-D614. This increased entry correlates with less S1 domain shedding and higher S protein incorporation into the virion. However, D614G does not alter S protein binding to ACE2 or neutralization sensitivity to pseudoviruses [24]. K417N and K417T mutations, detected in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of S glycoprotein of Beta and Gamma variant respectively, have been shown to have potential role in immune escape [25,26]. In addition to immune evasion, both K417N and K417T are expected to moderately decrease ACE2-binding affinity of S glycoprotein [27]. Another RBD mutation L452R, appeared in Delta variant, made the conformation of the S protein more stable, leading to the increased affinity of the virus to ACE2 receptor. L452 residue did not directly interact with ACE2, but could affect the structural stability of the region by which S protein interacts with ACE2 and facilitate SARS-CoV-2 entry into the host cell [28]. In addition, L452R mutation induces the conformational change of RBD and reduces the ability of monoclonal antibodies and convalescent sera to neutralize the virus [29]. N501Y mutation, shared by the three VOCs Alpha, Beta and Gamma, could enhance the affinity of the S protein with ACE2, especially with the side chains of residues Y41 and K353 of ACE2 [27,[30], [31], [32]]. In addition, N501Y mutation enabled the virus to infect BALB/c mice, which expanded its host range. Mutation at E484 site of RBD domain exists in the form of K484 in Beta and Gamma variants, while Q484 in Kappa variant. E484 site is one of the important immune dominant epitopes of S glycoprotein and mutation of this site to K, Q, or P decreases the neutralization ability of convalescent serum and some antibodies [[33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38]].

The present study primarily focused on the non-synonymous mutations which most likely have wide range of functional influence on viral proteins depending on the magnitude of differences in properties between the original and substituted amino acid. Although we overlooked the synonymous mutations which thought to have no phenotypic consequence on a protein, synonymous nucleotide substitution could affect mRNA folding, mRNA stability, miRNA binding, and translation efficiency [[39], [40], [41]]. Both synonymous and non-synonymous mutations have significant effects on the adaptation, virulence, and evolution of RNA viruses. Based on non-synonymous mutational analysis, here we revealed the emergence of a novel SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.526 harboring 11 coexisting mutations in seven different genes including D614G, P681H and V1230L in the S glycoprotein. Though the role of D614G in increased infectivity and transmissibility is well known, the functional relevance of P681H/R (previously observed in Alpha variant and Delta variant) and V1230L (first detected in this study) is yet to be determined. P681 is located adjacent to the polybasic furin cleavage site 681P-R-R-A-R-S686 where furin mediated proteolytic cleavage is expected to occur between arginine (R685) and serine (S686). This furin cleavage site is positioned at the junction between S1 domain, essential for virus binding to ACE2 receptor, and S2 domain, necessary for the fusion of virus envelope and cell membrane. The furin mediated cleavage at the junction of S1/S2 is essential for virus entry into the host cells [[42], [43], [44]]. Therefore, any mutation at this site could influence S1/S2 cleavage by furin-like proteases, and hence the infection properties of the virus. V1230L mutation, not observed previously in other lineage of SAR-CoV-2, is located at the transmembrane (TM) domain of S2 subunit of S glycoprotein. This transmembrane domain anchors S glycoprotein to the virus envelope. The replacement of valine with more hydrophobic amino acid leucine may tighten the association of S glycoprotein to the viral envelope and also increase S glycoprotein incorporation into the viral envelope. The high density of S glycoprotein to the viral envelope may lead to increased infectivity of the virus. However, further studies are required to reveal the functional relevance of this mutation. Interestingly, among 129 SARS-CoV-2 strains that encompass the novel lineage B.1.1.526, 27 strains harbor E484K mutation, which described to have role in immune evasion. Therefore, the novel lineage B.1.1.526 having D614G, P681H, V1230L and E484K mutations in the S glycoprotein is expected to have increased infectivity, high transmissibility, and enhanced immune evasion properties. Surveillance of this novel lineage is very essential to monitor the emergence of new mutations as well as to track their spread in the immediate future.

Authors’ contribution

RS1 and MCS conceived and designed the research. RS1, RS2, PM, RS3 and AK performed sequence retrieval, mutational analysis, and figure and table preparation. SD and MCS guided the project and gave valuable scientific inputs. RS1 and MCS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

No funding sources.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the scientists, researchers and laboratory staffs in India for their valued contribution in SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing and deposition in GISAID. We would also like to applaud GISAID consortium for allowing us the open access to the deposited SARS-CoV-2 sequences.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.11.020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Koyama T., Platt D., Parida L. Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(7):495. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.253591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rambaut A., Holmes E.C., O’Toole Á., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Ruis C., et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1403–1407. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey W.T., Carabelli A.M., Jackson B., Gupta R.K., Thomson E.C., Harrison E.M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(July (7)):409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;182(4):812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volz E., Hill V., McCrone J.T., Price A., Jorgensen D., O’Toole Á., et al. Evaluating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutation D614G on transmissibility and pathogenicity. Cell. 2021;184(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniloski Z., Jordan T.X., Ilmain J.K., Guo X., Bhabha G., Sanjana N.E. The spike D614G mutation increases SARS-CoV-2 infection of multiple human cell types. Elife. 2021;10:e65365. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rambaut A., Loman N., Pybus O., Barclay W., Barrett J., Carabelli A., et al. 2020. Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARSCoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations.https://virological.org/t/preliminary-genomic-characterisation-of-an-emergent-sars-cov-2-lineage-in-the-uk-defined-by-a-novel-set-of-spike-mutations/563 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Giovanetti M., Iranzadeh A., Fonseca V., Giandhari J., et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. MedRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P., Nair M.S., Liu L., Iketani S., Luo Y., Guo Y., et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593(7857):130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faria N.R., Claro I.M., Candido D., Franco L.M., Andrade P.S., Coletti T.M., et al. Genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus: preliminary findings. Virological. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabino E.C., Buss L.F., Carvalho M.P., Prete C.A., Crispim M.A., Fraiji N.A., et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):452–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W., Davis B.D., Chen S.S., Martinez J.M., Plummer J.T., Vail E. Emergence of a novel SARS-CoV-2 variant in Southern California. JAMA. 2021;325(13):1324–1326. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherian S., Potdar V., Jadhav S., Yadav P., Gupta N., Das M., et al. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations, L452R, E484Q and P681R, in the second wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira I., Datir R., Papa G., Kemp S., Meng B., Rakshit P., et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 emergence and sensitivity to vaccine-elicited antibodies. bioRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahoo J.P., Mishra A.P., Samal K.C. Triple mutant Bengal strain (B.1.618) of coronavirus and the worst COVID outbreak in India. Biotica Res Today. 2021;3(4):261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shu Y., McCauley J. GISAID: global initiative on sharing all influenza data — from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(13):30494. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar R., Mitra S., Chandra P., Saha P., Banerjee A., Dutta S., et al. Comprehensive analysis of genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in different geographic regions of India: an endeavour to classify Indian SARS-CoV-2 strains on the basis of co-existing mutations. Arch Virol. 2021;166(3):801–812. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K.I., Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(14):3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turakhia Y., Thornlow B., Hinrichs A.S., De Maio N., Gozashti L., Lanfear R., et al. Ultrafast Sample placement on existing tRees (UShER) enables real-time phylogenetics for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Nat Genet. 2021;53(6):809–816. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00862-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kostaki E.G., Tseti I., Tsiodras S., Pavlakis G.N., Sfikakis P.P., Paraskevis D. Temporal dominance of B. 1.1. 7 over B. 1.354 SARS-CoV-2 variant: a hypothesis based on areas of variant co-circulation. Life. 2021;11(5):375. doi: 10.3390/life11050375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plante J.A., Liu Y., Liu J., Xia H., Johnson B.A., Lokugamage K.G., et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature. 2021;592(7852):116–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L., Jackson C.B., Mou H., Ojha A., Peng H., Quinlan B.D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wibmer C.K., Ayres F., Hermanus T., Madzivhandila M., Kgagudi P., Oosthuysen B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 501Y. V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nat Med. 2021;27(April (4)):622–625. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greaney A.J., Starr T.N., Barnes C.O., Weisblum Y., Schmidt F., Caskey M., et al. Mutational escape from the polyclonal antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection is largely shaped by a single class of antibodies. bioRxiv. 2021;(January) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starr T.N., Greaney A.J., Hilton S.K., Ellis D., Crawford K.H., Dingens A.S., et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell. 2020;182(September (5)):1295–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng X., Garcia-Knight M.A., Khalid M.M., Servellita V., Wang C., Morris M.K., et al. Transmission, infectivity, and antibody neutralization of an emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant in California carrying a L452R spike protein mutation. MedRxiv. 2021;(January) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z., Van Blargan L.A., Bloyet L.M., Rothlauf P.W., Chen R.E., Stumpf S., et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations that attenuate monoclonal and serum antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(March (3)):477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villoutreix B.O., Calvez V., Marcelin A.G., Khatib A.M. In silico investigation of the new UK (B.1.1. 7) and South African (501y. v2) SARS-CoV-2 variants with a focus at the ACE2–spike RBD interface. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(January (4)):1695. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q., Nie J., Wu J., Zhang L., Ding R., Wang H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 501Y. V2 variants lack higher infectivity but do have immune escape. Cell. 2021;184(9):2362–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teruel N., Mailhot O., Najmanovich R.J. Modelling conformational state dynamics and its role on infection for SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein variants. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(August (8)):e1009286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greaney A.J., Loes A.N., Crawford K.H., Starr T.N., Malone K.D., Chu H.Y., et al. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(March (3)):463–476. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weisblum Y., Schmidt F., Zhang F., DaSilva J., Poston D., Lorenzi J.C., et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. Elife. 2020;9(October):e61312. doi: 10.7554/eLife.61312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreano E., Piccini G., Licastro D., Casalino L., Johnson N.V., Paciello I., et al. SARS-CoV-2 escape in vitro from a highly neutralizing COVID-19 convalescent plasma. BioRxiv. 2020;(January) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2103154118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baum A., Fulton B.O., Wloga E., Copin R., Pascal K.E., Russo V., et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science. 2020;369(August (6506)):1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q., Wu J., Nie J., Zhang L., Hao H., Liu S., et al. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. 2020;182(5):1284–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jangra S., Ye C., Rathnasinghe R., Stadlbauer D., Alshammary H., Amoako A.A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike E484K mutation reduces antibody neutralization. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e283–e284. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma Y., Miladi M., Dukare S., Boulay K., Caudron-Herger M., Groß M., et al. A pan-cancer analysis of synonymous mutations. Nat Commun. 2019;10(June (1)):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boon W.X., Sia B.Z., Ng C.H. Prediction of the effects of synonymous variants on SARS-CoV-2 genome. F1000Research. 2021;10(October (1053)):1053. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H., Pipes L., Nielsen R. Synonymous mutations and the molecular evolution of SARS-Cov-2 origins. Virus Evol. 2021;7(January (1)):veaa098. doi: 10.1093/ve/veaa098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson B.A., Xie X., Bailey A.L., Kalveram B., Lokugamage K.G., Muruato A., et al. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature. 2021;591(7849):293–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Pöhlmann S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol Cell. 2020;78(4):779–784. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lubinski B., Tang T., Daniel S., Jaimes J.A., Whittaker G. Functional evaluation of proteolytic activation for the SARS-CoV-2 variant B. 1.1.7: role of the P681H mutation. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.