Abstract

Background

Malnutrition negatively impacts on health, quality of life and disease outcomes in older adults. The reported factors associated with, and determinants of malnutrition, are inconsistent between studies. These factors may vary according to differences in rate of ageing. This review critically examines the evidence for the most frequently reported sociodemographic factors and determinants of malnutrition and identifies differences according to rates of ageing.

Methods

A systematic search of the PubMed Central and Embase databases was conducted in April 2019 to identify papers on ageing and poor nutritional status. Numerous factors were identified, including factors from demographic, food intake, lifestyle, social, physical functioning, psychological and disease-related domains. Where possible, community-dwelling populations assessed within the included studies (N = 68) were categorised according to their ageing rate: ‘successful’, ‘usual’ or ‘accelerated’.

Results

Low education level and unmarried status appear to be more frequently associated with malnutrition within the successful ageing category. Indicators of declining mobility and function are associated with malnutrition and increase in severity across the ageing categories. Falls and hospitalisation are associated with malnutrition irrespective of rate of ageing. Factors associated with malnutrition from the food intake, social and disease-related domains increase in severity in the accelerated ageing category. Having a cognitive impairment appears to be a determinant of malnutrition in successfully ageing populations whilst dementia is reported to be associated with malnutrition within usual and accelerated ageing populations.

Conclusions

This review summarises the factors associated with malnutrition and malnutrition risk reported in community-dwelling older adults focusing on differences identified according to rate of ageing. As the rate of ageing speeds up, an increasing number of factors are reported within the food intake, social and disease-related domains; these factors increase in severity in the accelerated ageing category. Knowledge of the specific factors and determinants associated with malnutrition according to older adults’ ageing rate could contribute to the identification and prevention of malnutrition. As most studies included in this review were cross-sectional, longitudinal studies and meta-analyses comprehensively assessing potential contributory factors are required to establish the true determinants of malnutrition.

Keywords: Undernutrition, Older adults, Determinants, Malnutrition

Background

Improvements in healthcare, along with the development of medical treatments and vaccines, have increased life expectancy worldwide [1]. This has radically changed the global population demographic, with the proportion of older adults increasing, especially in developed countries [2]. Within Europe, 19.2% of the population were aged 65 years or over in 2016, with a projected increase to 29.1% by 2080 [3]. Considerable challenges arise with this increasing ageing population, among them promoting good health and well-being within this group so that they can live independently in the community for as long as possible [4].

One such challenge among older adults living in the community is risk of malnutrition and more specifically undernutrition (hereafter referred to as malnutrition) [5, 6]. Older adults are at increased risk of developing malnutrition due to natural age-related changes [7], namely, unfavourable changes in body composition, increased requirements for protein and certain micronutrients, alterations in appetite and declining sensory function. Left untreated, malnutrition can detrimentally affect cognitive and physical function, both of which can lead to loss of independence, increased risk of disease and poorer health outcomes [8–11]. Moreover, malnutrition is a complex multifactorial process, with many other components, such as, lifestyle, financial, social, psychological, presence of disease and medication use, known to contribute [12]. Within the published literature, there is little consistency between previously reported factors associated with malnutrition. In developed countries, malnutrition prevalence differs across community and healthcare settings depending on the individual’s characteristics, and the tools used to identify malnutrition. The greatest number of malnourished older adults in the UK is in the community setting (accounting for approximately 5% of the older population) [13, 14]. Community-dwelling older adults are a heterogeneous group who may experience remarkable differences in their ageing trajectory; namely, successful, usual or accelerated rates [15]. Successfully ageing older adults have few health conditions, are independent, rarely use healthcare services and their years of ill health are condensed into the end-of-life. Usually ageing older adults typically maintain their functional ability and independence but have health conditions and require frequent visits to their general practitioner (GP) to maintain their health status. Those experiencing an accelerated rate of ageing are frailer and more dependent than expected for their age, have multiple chronic diseases or experience rapid disease progression, and are frequent users of healthcare services [15].

With the global increase in life expectancy, more attention is being drawn to different rates of ageing. In particular, the concept of successful ageing is now acknowledged to be an important area of research. Nonetheless, whilst there is general agreement on the characteristics typical of a person ageing at a successful rate, to date, there is no consensus on how this concept should be defined. One of the most used definitions for successful ageing is someone who is ‘free of disease and disability, has a high physical and cognitive functioning ability and has an active engagement with life in general’ [16]. Rate of ageing can be influenced both positively and negatively by lifestyle, diet, psychological, psychosocial and disease related factors. Higher rates of physical activity throughout life are strongly linked to successful ageing [17, 18]. Older adults who self-report good health and no pain are more likely to age successfully than those that don’t [19]. Older adults experiencing different ageing trajectories may have different determinants of malnutrition which are specific to their rate of ageing.

Malnutrition in older adults is often under-recognised and poorly managed [20]. This can be attributed to the fact that it is a slow progressing condition and, therefore, its early signs and symptoms are not easily recognised either by affected individuals [21] or healthcare professionals (HCPs) [22]. Additionally, a universal definition and agreed diagnostic criteria have only recently emerged [20, 23, 24]. With the aim of achieving consensus on the definition of malnutrition, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) stated (in 2015) that the following definition of malnutrition was generally accepted; “a state resulting from lack of uptake or intake of nutrition leading to altered body composition (decreased FFM) and body cell mass leading to diminished physical and mental function and impaired clinical outcome from disease” [25]. Furthermore, a global consensus for the diagnosis of malnutrition has recently (2019) been published based on a two-step approach; screening for risk of malnutrition using a validated tool, followed by assessment of the condition to provide a diagnosis of malnutrition and to grade its severity [26, 27].

Understanding and identifying factors that lead to malnutrition is critical for developing interventions aimed at preventing or delaying disability in older adults. This is particularly important in the community, where although prevalence is low, the greatest number of at-risk individuals reside [14, 28]. Community-dwelling older adults are a heterogeneous group; thus, the factors related to, or determinants of, malnutrition may vary according to individual differences in the rate of ageing. Potential differences in determinants of, and factors related to malnutrition according to differences in ageing rates may contribute to the heterogeneity between currently published studies. The aim of this review, therefore, is to summarise the current evidence relating to the sociodemographic factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition and malnutrition risk in community-dwelling older populations and, to explore potential differences according to different rates of ageing [15].

Methods

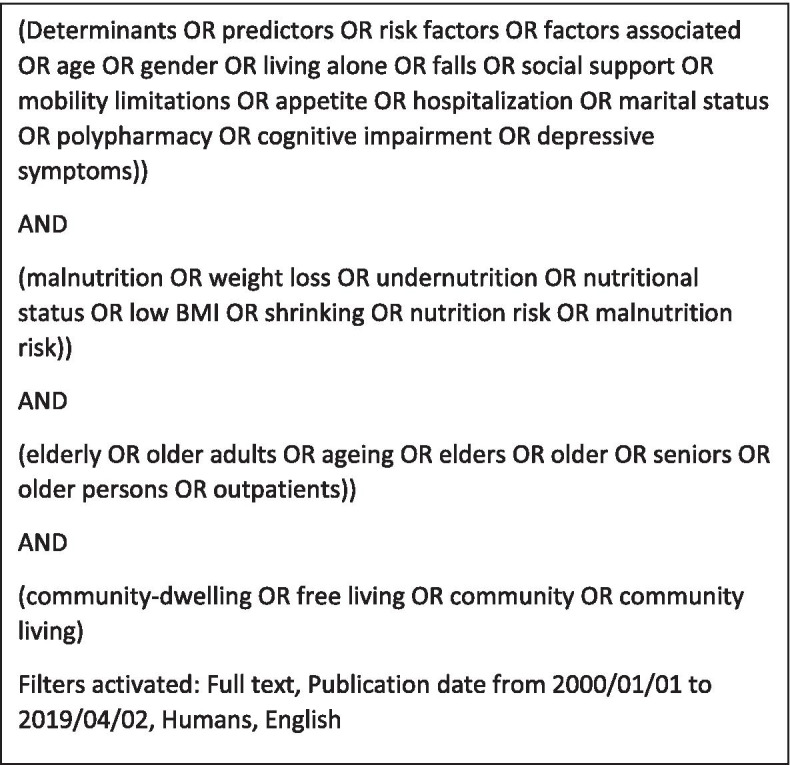

Search strategy

Two independent systematic searches (Search 1, LAB; Search 2, KL, ML, MGB) of PubMed Central and Embase databases were conducted in April 2019 to identify relevant papers on ageing and poor nutritional status. Duplicates were excluded (LAB and KL), and titles examined to assess suitability for inclusion (LAB and ML). Studies examining the sociodemographic factors associated with, or determinants of, malnutrition were included. The key search terms were as follows: the primary outcome (protein-energy malnutrition, malnutrition, undernutrition, weight loss, nutritional status); the population sub-group (elderly, older adults, ageing, aging); and the exposure (determinants, predictors, risk factors). Figure 1 shows the exact search terms used.

Fig. 1.

Search terms

Inclusion criteria

Studies with populations with mean age > 65 years, majority community-dwelling (> 80%), and conducted in Western populations (specifically European, North American, Canadian, Australian and New-Zealanders) were selected for consideration. Studies containing populations from multiple countries were only included if the majority of the population came from the specified Western countries. As the standardised criteria for diagnosing malnutrition were only published in 2019 [26, 27], papers using any definition of malnutrition arising from use of screening tools, specific BMI cut-offs or weight loss percentages were considered for inclusion. Only papers which were published since 2000, peer-reviewed, available in full-text, written in English, conducted on humans and in which the study authors completed multivariate statistical analysis were considered for inclusion. As the main aim of this review was to assess the sociodemographic factors associated with malnutrition according to a population’s rate of ageing, studies examining a combination of biochemical or nutritional factors in addition to sociodemographic factors were excluded [29–31].

Study selection

Abstracts were screened for inclusion by two authors independently (LAB and ML). If a study appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, full text articles were read and analysed for inclusion by two authors working independently (LAB and MGB). Final inclusion was decided by consensus discussion with a senior researcher working on the topic of community malnutrition (PDC).

Data synthesis

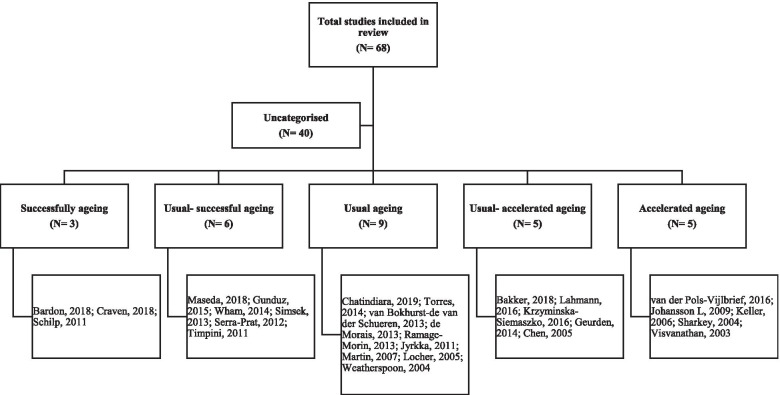

Selected full-text articles were read in full and the investigated factors categorised into domains. Factors suggested as being associated with malnutrition or as determinants of malnutrition were categorised under nine known domains: demographic, food intake, oral, lifestyle, social, economic, physical functioning, psychological and disease-related [32]. For the purposes of this review, poverty was included in the social domain and both edentulousness and chewing difficulties included in the food intake domain. Factors reported within each domain are summarised in Table 1. Where possible, study populations were categorised into successful, usual or accelerated rate of ageing groups according to the criteria suggested by Keller et al. (2007), as summarised below [15] (Fig. 2).

Successful ageing: predominantly functionally independent (> 60%), not frail (< 40%), low prevalence of polypharmacy (< 40%), and low prevalence of multi-morbidity (< 40%).

Usual ageing: predominantly functionally independent (> 60%), not frail (< 40%), a high proportion regularly attending a GP (> 50%), high prevalence of multi-morbidity (> 50%) and polypharmacy (> 50%).

Accelerated ageing: predominantly frail (> 60%), functionally dependent (> 60%), users of home-care services (> 40%), and a high proportion was recently hospitalised (> 50%).

Table 1.

Reported associated factors, and determinants, of malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults by domain

| Demographic | Food Intake | Lifestyle | Social | Physical function | Psychological | Disease-related |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [33] | Reduced appetite [34] | No alcohol use [35] | Poverty [36] | Frailty [37] | Depression [38] | Polypharmacy [39] |

| Marital status [33] | Edentulousness [38] | Smoking status [40] | Living alone [41] | Dependency [40] | Dementia [38] | Chronic disease [42] |

| Sex [43] | Ability to self-feed [44] | Low physical activity [40] | Social support [45] | Mobility [46] | Cognitive decline [46] | Self-reported health status [37] |

| Education [42] | Falls [47] | Anxiety [37] | Hospitalisation [46] | |||

| Handgrip strength [43] | Acute disease [40] | |||||

| Pain [48] |

Fig. 2.

Categorisation of studies included in review by rate of ageing

For each of the parameters listed above, any measure or tool or definition used by a particular study was deemed acceptable. In order for study populations to be categorised, information had to be available for at least two of the above criteria. Study populations were placed between two categories if there was insufficient information to differentiate which specific category the population should be placed in.

Results

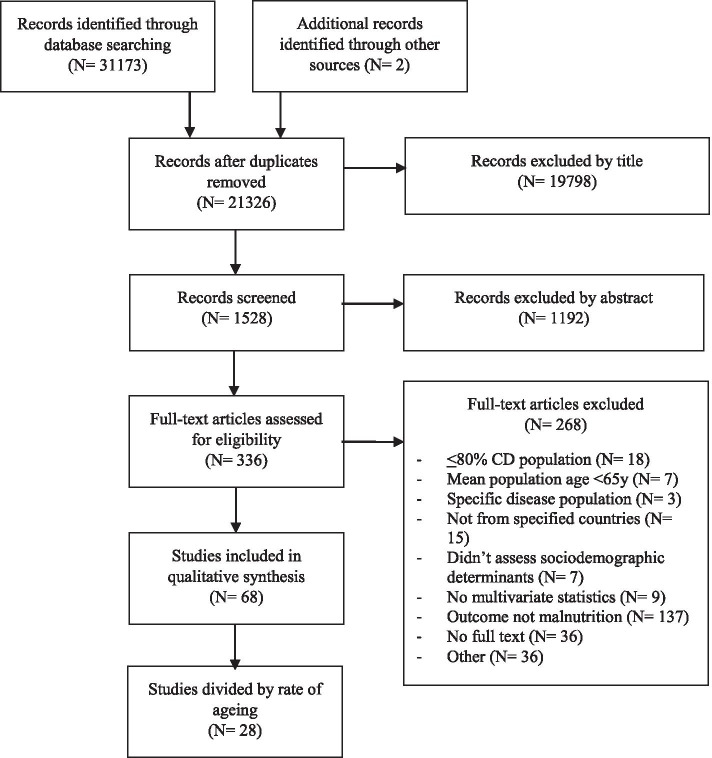

Search results

The initial database search yielded 21,326 papers once duplicates were deleted. All papers were considered for inclusion; reasons for exclusion are outlined in Fig. 3. The most common reasons for exclusion were studies conducted in non-Western populations, younger populations (mean < 65 years), populations with a specific disease or condition (e.g., Parkinson’s disease), studies whose primary focus was not malnutrition and studies completed in hospital, residential care, or rehabilitation settings. A total of 68 papers met the final inclusion criteria (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of selection criteria for inclusion in review

The articles included were heterogeneous in study design (Table 2). Studies were predominantly of cross-sectional (N = 54) or longitudinal design (N = 11). There were two systematic reviews of observational studies and one meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sample size of the studies ranged from 49 to 15,669 participants. The majority of included studies were conducted within European countries.

Table 2.

Factors associated with, and, determinants of malnutrition

| First Author, Year, Country, Sample size, Age (mean (SD)) | Sex (male %), Setting, Rate of Ageing | Outcome (assessment method) | Domain: Determinants Assessed | FU time | Statistical Analysis | Key Results* [OR (95% CI) p-value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||

| Chatindiara [49], 2019, New Zealand, N = 257, median 79 (IQR 7) | 46.7, CD, U | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, marital status, ethnicity, sex, education Social: Living situation, income source Food Intake: dysphagia risk (EAT-10), dental status Psychological: cognitive impairment (MoCA) Physical function: ADLs, handgrip strength, gait speed, physical performance (FTSTS) Disease-related: inflammation (CRP), number of comorbidities (> 5), polypharmacy (> 5 drugs), nutrition supplements use |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

age (continuous) [1.09 (1.01–1.17) p = 0.033]; age < 85y [0.30 (0.1–0.79) p = 0.015]; normal swallowing [0.29 (0.09–0.97) p = 0.045]; healthy physical performance [0.22 (0.07–0.71) p = 0.012]; BMI [0.82 (0.74–0.91) p < 0.001]; fat mass [0.86 (0.78–0.94) p = 0.002]; % body fat [0.81 (0.72–0.90) p < 0.001]; FFMI [0.51 (0.34–0.77) p = 0.001] |

| Craven [23], 2018, Australia, N = 77, 73.3 (5.1) | 60.0, CD, S | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Demographic: age, sex, relationship status, education Food Intake: SR healthiness of diet Social: living arrangement, home care services Disease-related: SR health, short form health survey (SF-12)- calculated PCS and MCS |

N/A | Multiple regression | PCS (ẞ = 0.290, Seẞ = 0.065, p < 0.05); MCS (ẞ = 0.377, Seẞ = 0.073, p < 0.05) |

| Maseda [45], 2018, Spain, N = 749, 75.8 (7.2) | 39.4%, CD attending SC, U-S | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, marital status Social: social support (OARS), living situation, loneliness Physical function: IADL Disease-related: QOL (WHOQOL-BREF) |

N/A | Multiple LR (forward stepwise) |

Total: female sex [0.6 (0.38–0.95) p = 0.028], social resources- total impairment [0.257 (0.08–0.85) p = 0.025], low physical health [1.676 (1.09–2.57) p = 0.018] Males: single status [0.08 (0.02–0.34) p < 0.001], divorced/separated status [0.096 (0.02–0.39) p < 0.001], poor health satisfaction [4.31 (1.82–10.25) p < 0.001] Females: social resources- mild impairment [0.51 (0.28–0.96) p = 0.036] |

| Ganhão-Arranhado [50], 2018, Portugal, N = 337, 78.4 (7.05) | 37.7%, CD attending SC, N/A | MN, MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age group, sex, marital status Social: income, SC attendance, motives for SC attendance, time of SC attendance, social risk, social net, social relationships Food Intake: food security Lifestyle: alcohol consumption, smoking status Disease-related: SR health, SR health conditions (respiratory, liver and rheumatic diseases, angina, MI, high BP, high blood cholesterol, stroke, DM, cancer, depression) Psychological: psychological stress |

N/A | UV regression, multinomial regression | MN risk: cerebrovascular accident [4.04 (1.19–13.74) P < 0.05]; acute MI [2.12 (0.95–4.72) p < 0.05]; better perceived health status [− 0.54 (0.37–0.79) p < 0.05]; attending SC <5y [− 0.41 (0.16–1.04) p < 0.05]; loneliness [2.01 (1.06–3.81) p < 0.05] MN: food insecurity [1.73 (1.20–2.48) p < 0.05]; female [7.87 (1.33–46.72) p < 0.05]; age 74-85y [− 0.10 (0.02–0.57) p < 0.05]; depression [37.41 (2.06–679.55) p < 0.05]; DM [− 0.105 (0.01–1.06) p < 0.05] |

| Fjell [51], 2018, Norway, N = 166, 78.7 (3.3) | 42%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, marital status Social: social support (OSLO 3-SSS) Lifestyle: exercise, alcohol consumption, smoking status Other: vision, hearing, sleep problems Disease-related: SR pain, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, eye disease, arthrosis, cancer Psychological: depression |

N/A | MV LR | poor SR health [5.77 (2.04–16.29) p = 0.001] |

| Grammatikopoulou [52], 2018, Greece, N = 207, 72.4 (8.5) | 43.5%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age, education, marital status, waist circumference, BMI Social: income, receiving financial assistance, Lifestyle: smoking status Food intake: appetite (CNAQ), food security (HFIAS), dietary variety (HDDS), diet quality (MEDAS) Disease-related: catabolic disease (cancer/renal/lung), cardiometabolic disease (CVD, hypertension, angina, arrhythmia, hyperuricemia, microalbuminuria, retinopathy, neuropathy, or history of acute MI, stroke or coronary by-pass surgery) |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

smoking [2.35 (1.09–5.08) p = 0.030]; not being married [2.10 (1.06–4.15) p = 0.033]; at risk for 5% WL [7.86 (4.07–15.18) p < 0.001]; food insecure [2.63 (1.21–5.75) p = 0.015] |

| Bakker [53], 2018, The Netherlands, N = 1325, median (IQR) 80 (77–84) | 41.4%, CD attending GP, U-A | MN (BMI < 20 kg/m2 and/or unintentional WL > 10% in 6 m and/or unintentional WL > 5% in 1 m) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, education, income Social: living situation Food intake: oral status, irregular dentist visits, oral hygiene, chewing problems, eating problems, speech problems, dental pain, dry mouth, insecurity with oral status, satisfaction with oral status Physical function: frailty (GFI), risk profile (frail, complex care needs, robust), ADL (Katz-15) Disease-related: number of chronic conditions, polypharmacy (> 4 drugs), complex care (IM-E-SA), QOL (EQ-5D, EQ-VAS) |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

health related QOL [0.97 (0.95–0.995) p = 0.015] |

| Jung [54], 2017, America, N = 171, 77.5 (8.2) | 29.8%, Rural CD excluding mild- moderate dementia (SPMSQ), N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, race or ethnicity, marital status, education Social: annual income, loneliness (UCLA loneliness scale) Psychological: depression (GDS) Disease-related: health status (SHPS), Physical function: ADL, IADL (Self-Care Capacity Scale) |

N/A | SEM |

parameter estimate (standard error): depression −0.30 (0.10) p = 0.001 |

| van der Pols-Vijlbrief [40], 2016, The Netherlands, N = 300, 81.7 (7.6) | 31.7%, CD, receiving home-care, A | MN risk (SNAQ65+) |

Demographic: sex, age, education level, marital status Social: living situation, social network (LSNS-6), social support, monthly income, financial ability to buy food (Determine your health checklist) Food intake: eating alone, SR oral health, chewing surface (full vs partial/none) appetite (SNAQapp), taste/smell loss, adequate snacks per day (> 3) Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption, PA Disease-related: number chronic diseases (> 2), polypharmacy (> 5 drugs), hospitalisation in past 6 m, SR health, pain (NHP), nausea, intestinal problems, fatigue Psychological: cognitive decline (IQCODE), depression (CES-D-10) Physical functioning: ADL (BI), IADL, mobility (bed/chair bound, able to move around the house but unable to leave house independently, able to leave house independently, difficulty climbing stairs, ability to walk 100 m), falls Other: visual function, hearing function |

N/A | MV LR | unable to go outside [5.39 (2.46–11.81) p < 0.001], intestinal problems [2.88 (1.57–5.28) p = 0.001], smoking [2.56 (1.37–4.77) p = 0.003], osteoporosis [2.46 (1.27–4.76) p = 0.007], fewer than 3 snacks per day [2.61 (1.37–4.97) p = 0.003], ADL dependency [1.21 (1.09–1.35) p = 0.001], physical inactivity [2.01 (1.13–3.59) p = 0.018], nausea [2.50 (1.14–5.48) p = 0.022], cancer [2.84 (1.12–7.21) p = 0.028] |

|

Lahmann [44], 2016, Germany, N = 878, 78.5 (12.2) |

37.1%, CD home care recipients, U-A | MN risk (MUST, MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex Social: social living status Disease-related: duration receiving home care Physical functioning: functional capacity (BI) |

N/A | LR | mental overload [8.1 (2.2–30.2) p < 0.01]; loss of appetite [3.6 (1.8–7.3) p < 0.01]; needs help with feeding [5.0 (2.3–11.2) p < 0.01]; dependent on feeding [1.9 (1.2–2.8) p < 0.01] |

| Maseda [55], 2016, Spain, N = 749, 75.8 (7.2) | 39.4%, CD attending SC, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: sex, age, education level, BMI ≥25 kg/m2 Disease-related: co-morbidity (CCI), SR health, polypharmacy (> 5 drugs) Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE), depressive symptoms (GDS-SF) Physical functioning: frailty status |

N/A | muliple LR (forward stepwise likelihood ratio) |

Total: BMI > 25 kg/m2 [2.15 (1.28–3.61) p = 0.004]; polypharmacy [0.43 (0.28–0.68) p < 0.001]; poor SR health [0.32 (0.12–0.86) p = 0.023]; depressive symptoms [0.45 (0.23–0.86) p = 0.015]; pre-frail/frail [0.51 (0.28–0.93) p = 0.027] Females: polypharmacy [0.52 (0.31–0.88) p = 0.014]; poor SR health [0.24 (0.09–0.66) p = 0.005] Males: BMI > 25 kg/m2 [4.35 (1.61–11.75) p = 0.004]; polypharmacy [0.26 (0.11–0.62) p = 0.002]; depressive symptoms [0.10 (0.04–0.31) p < 0.001] |

| Krzyminska-Siemaszko [38], 2016, Poland, N = 3751, 77.4 (8.0) | 52.8%, CD excluding cognitively impaired (MMSE), U-A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Psychological: depression (GDS), cognitive impairment (MMSE) Disease-related: polypharmacy (> 5 drugs), number chronic diseases (> 4), anaemia, peptic ulcer, stroke, Parkinson’s, cancer, pain Food intake: edentulism |

N/A | Multiple LR |

Total: female sex [1.72 (1.45–2.04) p < 0.001], age [2.16 (1.80–2.58) p < 0.001], depression [11.52 (9.24–14.38) p < 0.001], dementia [1.52 (1.20–1.93) p < 0.001], multi-morbidity [1.27 (1.04–1.57) p = 0.02], anaemia [1.80 (1.41–2.29) p < 0.001], total edentulism [1.26 (1.06–1.49) p = 0.009] Males: age [1.78 (1.40–2.27) p < 0.001], depression [12.80 (9.40–17.43) p < 0.001], dementia [1.58 (1.15–2.18) p = 0.005], anaemia [1.81(1.34–2.44) p < 0.001], total edentulism [1.31(1.04–1.66) p = 0.02] Females: age [2.77 (2.11–3.61) p < 0.001], depression [10.80 (7.85–14.87) p < 0.001], multi-morbidity [1.35 (1.01–1.79) p = 0.04], anaemia [1.99 (1.30–3.07) p = 0.002] |

| Krzymińska-Siemaszko [56], 2015, Poland, N = 4482, 78.6 (8.5) | 52.2%, CD, cognitively well (MMSE), N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, education Social: living situation |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

female [1.51 (1.19–1.92) p < 0.01]; every 10 y of life [2.18 (1.9–2.51) p < 0.01]; not married [1.50 (1.16–1.95) p < 0.01] |

|

Gunduz [42], 2015, Turkey, N = 1030, 71.7 (7) |

45.05% CD, outpatients, cognitively well (MMSE > 17), U-S |

MN (MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, education, no children Physical functioning: ADL, IADL Psychological: depression (GDS) Disease-related: comorbidities, polypharmacy (≥5 drugs) |

N/A | MV LR | age [(1.007–1.056) p = 0.012]; low BMI [(0.702–0.796) p < 0.001]; low education level [(0.359–0.897) p = 0.015]; depression score [(1.104–3.051); p = 0.02]; > 4 comorbidities [3.5 (2.30–5.45) p < 0.001] |

| Bailly [57], 2015, France, N = 464, 77.41 (7.48) | 31.3%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age Social: living alone, financial satisfaction Food intake: pleasure of eating (HTAQ) Psychological: depressive symptoms (GDS) Disease-related: SR health Physical functioning: IADL |

N/A | SEM |

Males: depression β = − 0.38; greater pleasure eating β = 0.20; higher SR health β = 0.32; greater IADL score β = 0.16 Females: age β = − 0.13; depression β = − 0.33; greater pleasure eating 0.19; higher SR health β = 0.25; greater IADL score β = 0.32 |

| Wham [58], 2015, New Zealand, Maori: N = 421, 82.8 (2.6) Non-maori: N = 516, 84.6 (0.5) | 33%, CD, N/A | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Demographic: age, sex Lifestyle: PA (PASE), smoking status, alcohol consumption Social: residential care, living situation, life satisfaction, difficulty getting to shops, drives a car, occupation, deprivation index, income Physical functioning: HGS, physical function (NEADL) Disease-related: health related QOL (SF-12), stroke, MI Psychological: cognitive function (3MS), depression (GDS-15) |

N/A | MV LR |

Maori: age [0.89 (0.79–0.99) p = 0.04]; primary education [3.41 (1.35–8.62) p = 0.03]; living alone (vs with others) [2.85 (1.34–6.05) p < 0.001]; living alone (vs with spouse) [4.10 (1.90–8.84) p < 0.001]; depression [1.30 (1.06–1.60) p = 0.01] Non-Maori: male [0.49 (0.30–0.81) p = 0.005]; living alone (vs with spouse) [2.41 (1.42–4.08) p = 0.002]; SF-12 PCS [0.98 (0.96–0.99) p = 0.02]; depression [1.24 (1.08–1.43) p = 0.002] |

| Wham, 2015 [59], New Zealand, N = 67, 77.0 (1.5) | 44%, CD Maori, N/A | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Demographic: sex, age, education, marital status Social: living situation, SR standard of living, importance of traditional food, importance of spirituality, use of traditional Māori as first language, living in large extended family area Disease-related: use of Māori medicine and healing Psychological: depression (GDS-15) Physical functioning: physical disability (NEADL) |

N/A | MV linear regression | language and culture being a little to moderately important [ẞ = 6.70, p < 0.05]; availability of traditional food [ẞ = − 5.23, p < 0.01]; waist-to-hip ratio [ẞ = 20.17, p = 0.01]; depressive symptoms [ẞ = − 0.60, p = 0.02] |

| Toussaint [60], 2015, The Netherlands, N = 345, 67.1 (6.0) CD; N = 138, 80.9 (7.6) outpatients | 46.4%, CD; 34.1%, outpatients, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex Food intake: olfactory function Lifestyle: smoking status Psychological: cognitive function (CD: MMSE; outpatients: DemTect), depressive symptoms (GDS) Disease-related: comorbidities (CCI), polypharmacy (> 5 drugs) |

N/A | Linear regression | CD: female [0.259 (0.031–0.488) p = 0.026] Outpatients: MMSE [ẞ (95% CI) p-value] [0.208 (0.059–0.357) p = 0.007]; GDS [− 0.378 (− 0.491- − 0.265) p < 0.001] |

| Rullier [61], 2014, France, N = 56, 70.9 (11.0) | 27%, CD caregivers, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, caregiver relationship with patient Social: living arrangements Psychological: Trait anxiety (STAI Y-B), depression (CES-d), caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview) Physical functioning: functional status (AGGIR) |

N/A | UV linear regression, multiple linear regression | functional dependency [ẞ = − 0.336, (1.57–6.48) p = 0.002]; depressive symptoms [ẞ = − 0.365, (− 0.199- − 0.054) p = 0.001]; more apathetic patient with dementia [ẞ = − 0.342 (− 0.606- − 0.158) p = 0.001] |

|

Torres [39], 2014, France, Rural: N = 692, 75.5 (6.2) Urban: N = 8691, 74.1 (5.5) |

62% (rural), 39.7% (urban), CD, U | MN risk (proxy MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, marital status Social: income Physical function: ADL (Katz ADL scale) Disease-related: polypharmacy (> 3 drugs) |

N/A | MV LR |

Rural: BMI < 21 kg/m2 [23.09 (5.1–104.46) p < 0.01], BMI 25–30 kg/m2 [0.41 (0.18–0.94) p < 0.01], BMI > 30 kg/m2 [0.16 (0.05–0.50) p < 0.01], dementia [3.04 (1.08–8.57) p = 0.04], polypharmacy [10.4 (2.59–4.20) p < 0.01] Urban: females [1.46 (1.22–1.75) p < 0.001], widowed status [1.36 (1.12–1.66) p < 0.01], BMI < 21 kg/m2 [9.11 (7.39–11.23) p < 0.001], BMI 25–30 kg/m2 [0.74 (0.61–0.89) p < 0.001], depression [20.67 (17.46–24.49) p < 0.001], dementia [3.42 (2.22–2.58) p < 0.001], loss of ADL [6.94 (3.91–12.31) p < 0.001], polypharmacy [3.52 (2.95–4.20) p < 0.001] |

|

Wham [41], 2014, New Zealand, N = 3893, > 65y, Maori: >75y |

46%, CD, U-S | MN risk (ANSI) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, education Social: WHOQOL- social, living situation Physical functioning: ADLs (NEADL) Psychological: depression (GDS) Disease-related: chronic diseases, polypharmacy (> 3 drugs) |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

female [1.41 (1.11–1.80) p = 0.006]; being Māori/other ethnicities vs European p = 0.002; not married p = 0.003; higher social health related QOL [0.94 (0.89–1.00) p = 0.036]; living with others related to low risk p < 0.0001; higher functional status [0.94 (0.90–0.99) p = 0.0182]; more depressive symptoms [1.10 (1.02–1.19)]; polypharmacy [1.34 (1.27–1.41) p < 0.0001] |

| Akin [62], 2014, Turkey, N = 845, 71.6 (5.6) | 53.2%, urban CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: sex, age, weight, BMI, WC, MUAC, education, marital status Social: living situation, income Physical functioning: 4 min walking speed, fear of falling, IADL, ADL, urinary incontinence Disease-related: SR chronic diseases (diabetes, hypertension, CHD, cerebrovascular disease, renal failure) Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE), depression (GDS) |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

depressive mood [4.18 (2.85–6.11) p < 0.001]; diabetes [1.60 (1.09–2.35) p = 0.017]; moderate income [1.65 (1.08–2.49) p = 0.019]; low income [2.36 (1.48–3.77) p < 0.001]; living alone [2.49 (1.56–3.97) p < 0.001]; WC [0.98 (0.96–0.99) p = 0.015]; MUAC [0.93 (0.83–0.99) p = 0.014]; 4 min walking speed [1.16 (1.07–1.25) p < 0.001] |

|

Geurden [63], 2014, Belgium, N = 100, 75.2 (17) |

22%, urban CD receiving homecare nursing, U-A | MN risk [64] |

Demographic: age, sex Food intake: eating problem, swallowing problem, loss of appetite, concern about eating problem/loss of appetite, GP informed about eating problem/loss of appetite, nutrition intervention prescribed, one warm meal every day Physical functioning: independent shopping, independent cooking, use of informal care, use of professional homecare Disease-related: hospitalisation in last 3 m, days since last GP visit |

N/A | MV LR | loss of appetite p < 0.001 |

| Westergren [65], 2014, Sweden, N = 465, 78.5 (3.7) | 46.5%, CD without cognitive deficits, N/A | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Social: need for help with groceries, need for help with cooking Physical functioning: falls (Downton falls risk index) Disease-related: SR health Psychological: SR life satisfaction, anxiety/worries, low-spiritedness, fatigue/tiredness, sleeping well |

N/A | stepwise ordinal regression Linear (backward) regression | living alone (females) [4.63 (2.85–7.52) p < 0.001]; living alone (males) [6.23 (3.35–11.59) p < 0.001]; age [0.86 (0.81–0.91) p < 0.001]; quite good SR health [2.03 (1.27–3.27) p = 0.003]; quite/very poor SR health [5.01 (2.23–11.23) p < 0.001]; often/always tired [2.38 (1.26–4.50) p = 0.008]; falls risk [1.21 (1.05–1.40) p = 0.010] |

|

van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren [35], 2013, Netherlands, N = 448, 80 (7) |

38%, outpatients living independently- in own home or assisted care facility, U |

MN (MNA) |

Demographic: education, marital status, children Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption Physical functioning: ADLs, IADLs, falls, walking aid Psychological: depression (GDS), cognitive impairment (MMSE) Disease-related: polypharmacy (> 6 drugs), multi-comorbidities (> 4 diseases) |

N/A |

UV LR MV backward stepwise LR |

alcohol use [0.4 (0.2–0.9) p < 0.05]; being IADL dependent [2.8 (1.3–6.4) p < 0.05]; depression [2.6 (1.3–5.3) p < 0.05] |

|

de Morais [66], 2013, 8 European countries (Denmark, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK), N = 644, 74.8 (5.8) |

49.8%, CD, U | MN risk (Determine your health checklist) |

Demographic: BMI Social: living situation Food Intake: number of fruit and vegetables per day, chooses easy to chew food, changes in appetite Disease-related: SR health, changes in health/health problems (SF-36) |

N/A | backward stepwise LR | low BMI [ẞ (95% CI) p-value] [0.005 (0.001–0.01) p = 0.007]; number fruit and vegetables/day [− 0.21 (− 0.40- -0.03) p = 0.023]; general health [− 0.02 (− 0.03- -0.01) p = 0.006]; chooses easy to chew food [0.32 (0.15–0.49) p < 0.001]; living with another adult [2.82 (1.27–6.25) p = 0.011]; living alone [3.22 (2.00–5.16) p < 0.001]; changes in appetite [0.41 (0.20–0.85) p = 0.016]; changes in health/health problems [7.74 (4.02–14.90) p < 0.001] |

| Syrjälä [67], 2013, Finland, N = 157, > 75y | 29.9%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: sex, education Food Intake: unstimulated salivary flow, stimulated salivary flow, number of teeth, number of the occluding molars/pre-molars, dentures, SR chewing problems Social: use of a meal service Disease-related: number of medications, DM Psychological: cognitive function (MMSE) Physical functioning: IADLs |

N/A | MV LR | Stimulated/unstimulated salivary flow not associated with MN risk |

| Simsek [68], 2013, Turkey, N = 650, 74.1 (6.3) | 37.1%, CD living in a low socioeconomic area, U-S | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, education Social: self-perceived economic status, social class, social insurance, ownership of house, personal income, living situation Food intake: food insecurity Physical functioning: orthopaedic disability Disease-related: number chronic diseases, polypharmacy (> 5 drugs), SR health |

N/A | MV LR | age [1.06 (1.02–1.10) p = 0.001]; number chronic diseases [1.41 (1.18–1.70) p < 0.001]; not being married [2.13 (1.31–3.46) p = 0.002]; SR poor economic status [2.49 (1.41–4.41) p = 0.002]; orthopaedic disability [1.95 (1.01–3.75) p = 0.047]; food insecurity [2.49 (1.48–4.16) p = 0.001]; poor SR health [4.33 (2.58–7.27) p < 0.001] |

|

Smoliner [69], 2013, Germany, N = 191, 79.6 (6.3) |

28.3%, CD day hospital attendees without Parkinson’s disease or MMSE score < 20, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age Food intake: olfactory function (Sniffin sticks test) Psychological: cognitive function (MMSE) Disease-related: number of drugs Physical functioning: self-care capacity (BI) |

N/A | Linear regression | BI [0.329 (0.03–0.08) p < 0.001] |

| Ramage-Morin [70], 2013, Canada, N = 15,669, 77 (No SD) | 40.4%, CD, U | MN risk (SCREEN 2-AB) |

Demographic: age, education Food Intake: oral health Social: income quintile, living situation, social support (Tangible Support MOS Subscale), social participation, driving status Disease-related: number of medications Psychological: depressive symptoms (subset of questions from CIDI) Physical functioning: level of disability (HUI) |

N/A | MV LR |

Males: lowest income quintile [1.46 (1.16–1.85) p < 0.05]; living alone [2.86 (2.39–3.42) p < 0.05]; low social support [1.31 (1.06–1.62) p < 0.05]; infrequent social participation [1.46 (1.20–1.76) p < 0.05]; depression [2.77 (1.51–5.06) p < 0.05]; moderate/severe disability [1.59 (1.32–1.90) p < 0.05]; taking 2–4 drugs/day [1.31 (1.10–1.56) p < 0.05]; taking > 5 drugs/day [1.69 (1.17–2.44) p < 0.05] Females: age [0.98 (0.97–0.99) p < 0.05]; living alone [1.85 (1.61–2.12) p < 0.05]; low social support [1.49 (1.26–1.75) p < 0.05]; infrequent social participation [1.43 (1.22–1.69) p < 0.05]; depression [2.21 (1.54–3.17) p < 0.05]; moderate/severe disability [1.82 (1.58–2.11) p < 0.05]; 2–4 drugs/day [1.42 (1.23–1.63) p < 0.05]; > 5 drugs/day [2.23 (1.71–2.91) p < 0.05]; fair/poor oral health [1.54 (1.27–1.88) p < 0.05] |

|

Söderhamn [71], 2012, Norway, N = 2106, 74.5 (6.9) |

49.5, CD, N/A | MN risk (NUFFE-NO, MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status Lifestyle: being active Food Intake: eating sufficiently, preparing food, having access to meals Social: occupation, social support (receiving help to manage daily life), frequency of contact with family/neighbours/friends, loneliness, receiving home nursing, receiving home help Disease-related: SR health, presence of chronic disease/handicap Psychological: feeling depressed |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR (forward stepwise conditional) |

NUFFE-NO: single [2.99 (2.17–4.13) p < 0.001]; professional/white collar worker [0.50 (0.36–0.69) p < 0.001]; depressed [1.71 (1.07–2.76) p = 0.026]; chronic disease/handicap [2.15 (1.57–2.96) p < 0.001]; being active [0.26 (0.17–0.39) p < 0.001]; eating sufficiently [0.07 (0.02–0.21) p < 0.001]; receiving home nursing [2.99 (1.37–6.56) p < 0.006]; receiving family help [1.92 (1.40–2.64) p < 0.001]; contact with neighbours [0.73 (0.61–0.89) p = 0.001] MNA-SF: female [1.70 (1.18–2.43) p = 0.004]; receiving help [1.67 (1.02–2.75) p = 0.042]; perceived helplessness [2.39 (1.41–4.02) p = 0.001]; chronic disease/handicap [1.56 (1.08–2.25) p = 0.019]; eating sufficiently [0.18 (0.08–0.39) p < 0.001]; receiving home help [1.88 (1.25–2.81) p = 0.006]; receiving family help [1.88 (1.25–2.81) p = 0.002]; having contacts with family [0.59 (0.40–0.86) p = 0.006]; having contacts with neighbours [0.76 (0.62–0.93) p = 0.008] |

| Nykänen [72], 2012, Finland, N = 696, 81 (4.6) | 30.6%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, education Food Intake: dry mouth/chewing problems Social: living situation Disease-related: SR health, number of drugs used regularly Psychological: depressive symptoms (GDS), cognitive impairment (MMSE) Physical functioning: ADLs, IADLs, ability to walk 400 m independently |

N/A | UV regression MV regression (stepwise, forward selection) | dry mouth/chewing problems [2.01 (1.14–3.54) p < 0.05]; IADL [0.85 (0.75–0.96) p < 0.05]; MMSE [0.90 (0.85–0.96) p < 0.05] |

| Tomstad [73], 2012, Norway, N = 158, 73.2 (6.9) | 41.8%, CD, N/A | MN risk (NUFFE) | Demographic: age, marital status Physical functioning: self-care (SASE) Social: attitude to life (SOC), living situation, social support, receiving home help, perceived helplessness Lifestyle: being active Psychological: perceiving life as meaningful | N/A | MV LR (forward stepwise conditional) | living alone [7.46 (2.58–21.53) p < 0.001]; receiving help regularly [9.32 (2.39–36.42) p = 0.001]; being active [0.17 (0.04–0.65) p = 0.010]; perceived helplessness [6.87 (1.44–32.78) p = 0.016] |

| McElnay [74], 2012, New Zealand, N = 473, 74.0 (no SD) | 43.8%, CD, N/A | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Demographic: ethnicity (Maori vs not), sex, age Social: living situation |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR (model 1, forced entry; model 2, forward stepwise) |

Model 1: Maori [5.21 (1.52–17.90) p = 0.009]; living alone [3.53 (2.06–6.06) p < 0.001] Model 2: Maori [6.44 (1.87–22.11) p = 0.003] |

| Zeanandin [75], 2012, France, N = 190, 81.2 (4.4) | 37.4%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: BMI Food intake: restrictive diet type, diet duration, diet compliance Disease-related: comorbidities, polypharmacy |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR |

absence of diet [0.3 (0.1–0.6) p < 0.001]; increased BMI [1.3 (1.2–1.5) p < 0.001]; on a restrictive diet [3.6 (1.8–7.2) p < 0.001] |

|

Samuel [76], 2012, America, N = 679, 74.06 (2.8) |

0%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, race, marital status, education Social: financial strain, annual income, participation in food stamps program, difficulty driving Disease-related: congestive heart failure, cancer |

N/A | MV LR |

Enough to make ends meet model: not enough to make ends meet [4.08 (1.95–8.52) p < 0.05]; income < $6000/m [2.54 (1.07–5.99) p < 0.05]; age [1.12 (1.03–1.22) p < 0.05] Lack of income for food model: lack of money fairly/very often [2.98 (1.15–7.73) p < 0.05]; income < $6000/m [2.77 (1.10–6.98) p < 0.05]; age [1.11 (1.02–1.21) p < 0.05] |

|

Timpini [77], 2011, Italy, N = 698, 75.6 (6.4) |

41.5%, CD, U-S | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: education Lifestyle: PA |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR models |

low education [2.9 (1.2–6.8) p < 0.05]; lack of PA- model 1 [4.5 (2.2–9.8) p < 0.05], model 2 [4.8 (1.9–11.8) p < 0.05] |

|

Kvamme [78], 2011, Norway, N = 3111, 71.6 (5.45) |

50%, CD, N/A | MN, MN risk [64] | Psychological: anxiety and depression (SCL-10) | N/A | LR | anxiety/depression symptoms with MN risk: males [3.9 (1.7–8.6) p < 0.05], females [2.5 (1.3–4.9) p < 0.05] |

| Fagerstrom [79], 2011, Sweden, N = 1230, 76.1 (9.9) | 42.4%, CD, N/A | MN (BMI < 23 kg/m2) |

Demographic: age, sex, living arrangement Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE) Physical functioning: ADLs |

N/A |

UV LR MV LR (backward likelihood ratio stepwise) |

age [1.02 (1.00–1.04) p = 0.032]; being female [2.20 (1.55–3.11) p < 0.001]; moderate/severe cognitive impairment [3.32 (1.77–6.24) p < 0.001] |

| Wham [80], 2011, New Zealand, N = 51, 82.4 (1.7) | 29.0%, CD, N/A | MN risk (SCREEN 2) |

Demographic: age, sex, ethnicity Social: living situation, access to a car, socioeconomic deprivation, strength of social support/network (PANT), loneliness (EASY-Care) Psychological: depression (EASY-Care), cognitive impairment (EASY-Care) Physical functioning: disability score (EASY-Care) Disease-related: SR health (EASY-Care), |

N/A | multiple linear regression | good SR health [coefficient (SE) p-value] [− 4.31 (1.98) p = 0.035]; poor SR health [− 10.23 (2.31) p < 0.001]; British/Canadian country of origin [− 5.55 (2.14) p = 0.013]; change in living situation, previously with spouse [− 5.31 (2.2) p = 0.02]; good SR health*some evidence depression [12.40 (5.24) p = 0.023]; poor SR health*some evidence depression [14.96 (5.84) p = 0.014] |

| Romero-Ortuno [81], 2011, Ireland, N = 556, 72.5 (7.1) | 30.2%, CD independently mobile (with/without walking aid) outpatients, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex Social: social support (LSNS-18), deprivation scale (NIDS), personality traits (EPI), loneliness (De Jong gierveld) Physical functioning: mobility (TUG) Disease-related: comorbidities (CCI) Psychological: cognitive function (MMSE), depressive symptoms (CES-d) |

N/A | MV LR | TUG [1.11 (1.05–1.18) p < 0.001]; LSNS-18 [0.96 (0.93–0.99) p < 0.005]; NIDS [1.20 (1.03–1.39) p < 0.018]; age [1.07 (1.01–1.13) p < 0.032] |

| Soderhamn [82], 2010, Sweden, N = 1461, > 75 y | 45.2, 98% CD, 2% institutionalised, N/A | MN risk (NUFFE) |

Demographic: sex, marital status, education Social: living setting Physical function: help to manage daily life Disease-related: perceived health |

N/A | MV stepwise LR | living alone [4.85 (3.59–6.56) p < 0.05]; receiving help to manage daily life [2.55 (1.77–3.66) p < 0.05]; perceived health [0.96 (0.96–0.97) p < 0.05] |

| Sorbye [48], 2008, 11 European sites (Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Netherlands, Germany, UK), N = 4010, 82.5 (7.3) | 26%, CD receiving home care or nursing care services, N/A | unintentional WL (> 5% in past 30 days or > 10% in past 180 days) | Demographic: age, sex, severe MN Food intake: < 1 meal/day, insufficient food and fluid intake, insufficient fluid intake, oral problems with swallowing food, pain in the mouth while eating, dry mouth, tube feeding, reduced appetite, vomiting Disease-related: constipation, diarrhoea, daily pain, pain disrupts normal activity, pressure ulcers, SR health, terminal prognosis < 6 m Physical functioning: fall last 90 days, IADL dependency > 3 (index 0–7), ADL dependency > 3 (index 0–8) Other: vision decline past 90 days Social: reduced social activity, feels lonely, not out of house in last week Psychological: risk of depression ≥1 (index 0–9), cognition [CPS > 3 (hierarchy scale 0–6)] | N/A | MV LR (Wald forward stepwise) | < 1 meal/day [4.2 (2.8–6.4) p < 0.05]; reduced appetite [2.5 (1.9–3.4) p < 0.05]; severe MN [7.1 (4.2–11.9) p < 0.05]; reduced social activity [2.0 (1.6–2.5) p < 0.05]; hospitalisation past 90 days [2.1 (1.6–2.7) p < 0.05]; eating less [2.8 (1.8–4.4) p < 0.05]; constipation [1.9 (1.3–2.7) p < 0.05]; falls [1.5 (1.2–1.9) p < 0.05]; oral problem swallowing food [2.8 (1.8–4.4) p < 0.05]; flare-up of chronic disease [1.5 (1.1–2.1) p < 0.05]; pressure ulcers [1.5 (1.2–1.9) p < 0.05]; daily pain [1.3 (1.0–1.6) p < 0.05] |

|

Gil-Montoya [83], 2008, Spain, N = 2860, 73.6 (6.8) |

42, 88.5% CD, 11.5% institutionalised, N/A | MN risk (MNA) | Demographic: age, sex, institutionalization Food intake: dental status, oral health QOL (GOHAI score) | N/A | multiple linear regression | age [(1.01–1.04) p < 0.001]; male [(1.19–1.66) p < 0.001]; institutionalisation [(1.16–1.92) p < 0.05]; GOHAI [(0.93–0.95) p < 0.001] |

| Roberts [37], 2007, Canada, N = 839, 79.6 (no SD) | 31.3%, CD with no more than MCI, N/A | MN risk (ENS) |

Demographic: sex, age, education, marital status Social: living situation Physical functioning: physical limitations (walking), ADLs/IADLs a Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE) Disease-related: chronic diseases (CDS), SR health status |

longitudinal subset (N = 335 at risk at baseline): 1 y FU |

Cross-sectional: simple LR, MV Longitudinal: simple LR, MV |

Cross-sectional: age [1.05 (1.00–1.09) p < 0.05]; ADL [1.59 (1.02–2.49) p < 0.05]; IADL ‘need’ [1.45 (1.02–2.07) p < 0.05]; psychological distress (feelings of depression, anxiety, irritability, impaired cognition) [2.24 (1.22–4.09) p < 0.05]; current SR health [3.34 (2.01–5.54) p < 0.05] Longitudinal: SR health among those at low MN risk [OR = 3.30, p < 0.05] |

|

Martin [84], 2007, America, N = 130, 78 (2.3) |

45.4%, CD attending VA outpatient clinics with BMI < 24 kg/m2, without dementia (MMSE)/ cancer/heart failure, U | MN (BMI < 19 kg/m2) |

Demographic: age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, religion Social: annual income, social support, type of residence Lifestyle: PA, smoking status, alcohol consumption Disease-related: medication use, comorbidities, hospitalisation, doctor visits Psychological: depression (GDS) |

N/A | MV LR | having an illness/condition which changed the type/amount of food eaten [4.7 (1.6–13.1) p < 0.05], unintentional WL of > 10 lb. in past 6 m [4.0 (1.5–10.7) p < 0.05], requiring assistance with travel [4.0 (1.4–11.3) p < 0.05] |

|

Chen [36], 2005, America, N = 240, 81.7 (8.7) |

21.7, CD, U-A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, education, religion Social: living situation, income levels, social support (SSQSF), loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale) Disease-related: comorbidities (Co-morbidity checklist), medication use Food Intake: oral health (BOHSE, GOHAI) Psychological: depression (GDS) Physical functioning: physical and social competence (ESDS) |

N/A | MV hierarchical LR | annual income > $10,000 [0.40 (0.19–0.84) p = 0.014], depression [1.12 (1.03–1.21) p = 0.008], functional status [1.09 (1.03–1.15) p = 0.005], self-perceived oral health [0.87 (0.78–0.97) p = 0.009] |

|

Locher [85], 2005, America, N = 1000, 75.3 (no SD) |

50.1%, CD, U | MN risk (Determine your health checklist) | Demographic: age, education, marital status Social: rural location, income, reliable transportation, social support, y at address, religious attendance, fear attack, experience discrimination, veteran Physical functioning: mobility (Independent life-space) | N/A | multiple linear regression |

Black women: reliable transportation [ẞ = 0.196, t = 2.896, p = 0.004]; independent life-space [ẞ = − 0.344, t = − 4.626, p < 0.001]; income [ẞ = − 0.185, t = − 2.227, p = 0.027] Black men: independent life-space [ẞ = − 0.245, t = − 3.415, p = 0.001]; being married [ẞ = − 0.245, t = − 3.415, p = 0.001]; religious attendance [ẞ = − 0.185, t = − 2.781, p = 0.006]; fear attack [ẞ = 0.143, t = 2.300, p = 0.023]; experienced discrimination [ẞ = 0.157, t = 2.450, p = 0.015] White women: independent life-space [ẞ = − 0.297, t = − 4.121, p < 0.001]; social support scale [ẞ = 0.156, t = 2.425, p = 0.016]; income [ẞ = − 0.216, t = − 2.259, p = 0.025] White men: reliable transportation [ẞ = 0.195, t = 2.957, p = 0.003]; independent life-space [ẞ = − 0.282, t = − 4.151, p < 0.001] |

| Johnson [86], 2005, Canada, N = 54, 81 (no SD) | 48%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) | Social: perceived social support (LSNS) Psychological: life satisfaction (13-item Life Satisfaction Index Form Z), depression (GDS) | N/A | Hierarchical regression analysis (forward selection) | depression (B = − 0.534, p = 0.001), social support (B = 0.310, p = 0.013) |

| Weatherspoon [87], 2004, America, N = 324, > 60 y (no mean) | 25%, CD, U | MN risk (Determine your health checklist) |

Demographic: age, sex, ethnicity Social: use of home health aide/caregiver Disease-related: SR health, frequency of doctor, clinic and dentist visits, use of visiting nurse, number of nutritionist/dietitian visits, intake of laxatives, sleep medication, tranquilizers, antacids Food intake: intake of vitamins, fibre supplements, fluid intake |

N/A | MV LR | rural location [2.70 (1.2–5.9) p = 0.01]; poor SR health [4.28 (1.02–17.9) p = 0.04]; not visiting GP regularly [0.34 (0.15–0.77) p = 0.01] |

|

Sharkey [88], 2004, America, N = 908, 78.2 (8.2) |

37.8%, CD MOW recipients, A | MN risk (Nutritional Health Screen- modified version of Determine your health checklist) |

Demographic: age, sex, ethnicity (Mexican-American vs not), marital status Social: rural area of residence, poverty guideline Disease-related: multi-comorbidities (> 3 comorbidities) Physical-functioning: ADLs, IADLs |

N/A | MV LR | Mexican-American [1.47 (1.05–2.06) p = 0.026]; rural [1.49 (1.02–2.18) p = 0.04]; not being married [1.77 (1.33–2.36) p = 0.001]; worst IADL score [0.44 (0.27–0.70) p = 0.001]; worst ADL score [1.74 (1.12–2.71) p = 0.014] |

| Margetts [89], 2003, UK, N = 1632, > 65 y (no mean given) | 50.7%, CD: 82.5%, institutionalised: 17.5%, N/A | MN risk (MAG tool: high risk = BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or BMI 18.5–20.0 kg/m2 with WL of > 3.2 kg or BMI > 20.0 kg/m2 with WL > 6.4 kg; medium risk = BMI 18.5–20.0 kg/m2 with < 3.2 kg (unless no long-term illness and no WL) or BMI > 20 kg/m2 and WL 3.2–6.4 kg; low risk = BMI > 20 kg/m2 with no WL (< 5% BW) |

Demographic: age, region, setting Disease-related: SR health, long standing illness, hospitalisation in the last y |

N/A | MV LR |

Males: hospitalisation in past y [1.83 (1.06–3.16) p < 0.05]; being institutionalised [2.17 (1.22–3.88) p < 0.05]; longstanding illness [2.34 (1.20–4.58) p < 0.05]; age > 85 y [2.64 (1.30–5.33) p < 0.05]; from northern England/Scotland vs southeast England/London [2.81 (1.54–5.11) p < 0.05] Females: poor SR health [2.82 (1.25–6.38) p < 0.05]; longstanding illness [2.98 (1.58–5.62) p < 0.05] |

| Sharkey [90], 2002, America, N = 729, 79 (no SD) | 0%, CD receiving MOW, N/A | MN risk (Determine your health checklist) |

Demographic: age, race Social: living situation, income, MOW service use Physical functioning: functional disability (ADL) |

N/A |

UV ordered LR MV ordered LR |

Total sample: being black [coefficient, p-value] [0.62, p < 0.001]; age 60–74 y [0.80, p < 0.001]; poverty [0.43, p < 0.001]; living alone [0.51, p < 0.001]; increasing m using MOW service [0.096, p < 0.05] Black women: aged 60–74 y [0.72, p < 0.01] White women: living alone [0.76, p < 0.001]; poverty [0.47, p < 0.05], aged 60–74 y [0.86, p < 0.001] |

| Pearson [91], 2001, towns within 9 European countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Poland), N = 627, 80–85 y (no mean/SD given) | 45.9%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: sex, living situation Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE) Physical functioning: ability to complete all self-care ADLs |

N/A | MV LR |

Total: diminished cognitive function [2.10 (1.98–2.22) p < 0.05]; diminished self-care ability [2.44 (2.32–2.56) p < 0.001] Males: diminished self-care ability [2.93 (2.76–3.10) p < 0.01]; diminished cognitive function [2.65 (2.46–2.84) p < 0.05]; living alone [1.23 (1.06–1.40) p < 0.05] Females: diminished self-care ability [2.06 (1.90–2.22) p < 0.05]; diminished cognitive function [1.77 (1.61–1.93) p < 0.05] |

| Longitudinal studies | ||||||

| Bardon [46], 2018, Ireland, N = 1841, 72 (4.99) | 49.8%, CD dementia free (MMSE), S | MN (BMI < 20 kg/m2 or WL > 10% over 2 y) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, marital status Food intake: appetite Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption, PA Social: living situation, social support Disease-related: number chronic disease (> 2), polypharmacy (> 5 drugs), pain, SR health, hospitalisation 1 y before baseline, hospitalisation 1 y before FU Physical functioning: falls 1 y before baseline, falls during FU, difficulty climbing stairs without rest, difficulty walking 100 m without rest, HGS Psychological: depression (CES-D), cognitive impairment (MMSE) |

2 y |

UV LR MV LR |

Total: unmarried/separated/divorced status [1.84 (1.21–2.81) p < 0.05], hospitalisation 1 y before FU [1.62 (1.14–2.30) p < 0.05], difficulty climbing stairs [1.56 (1.12–2.17) p < 0.05], difficulty walking 100 m [1.83 (1.13–2.97) p < 0.05] Males: falls during FU [1.62 (1.01–2.59) p < 0.05], difficulty climbing flight stairs [2.25 (1.44–3.50) p < 0.05], hospitalisation 1 y before FU [1.73 (1.08–2.77) p < 0.05] Females: social support [2.44 (1.19–4.99) p < 0.05], cognitive impairment [2.29 (1.04–5.03) p < 0.05] |

| Hengeveld [92], 2018, America, N = 2212, 74.6 (2.9) | 49.6%, well functioning CD, N/A | MN (PEM: BMI < 20 kg/m2 and/or involuntary WL ≥5% in the past y) |

Demographic: age, sex, race, education, BMI Social: living situation, income Lifestyle: PA, smoking status, alcohol consumption Food Intake: diet quality (HEI), protein intake (g/kg BW/d), appetite, biting/chewing difficulty Disease-related: SR health status, chronic diseases (cancer, DM, CVD, chronic pulmonary disease, osteoporosis) Psychological: cognitive function (modified MMSE), depression |

yearly for 4 y | MV Cox proportional hazards analysis | Developing PEM during 4 y of FU: low energy intake [0.71 (0.55–0.91) p < 0.05] Having persistent PEM (PEM at 2 consecutive FUs): poor HEI score [0.97 (0.95–0.99) p < 0.05]; low EI [0.56 (0.36–0.87) p < 0.05]; low protein intake [1.15 (1.03–1.29) p < 0.05] |

| Serra-Prat [93], 2012, Spain, N = 254, 78.2 (5.6) | 53.5%, CD, U-S | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age Food Intake: impaired efficacy of swallow (impaired labial seal, oral or pharyngeal residue, piecemeal deglutition) Physical functioning: functional capacity (BI) |

1 y | MV LR | No significant results when adjusted for age |

|

Schilp [94], 2011, Netherlands, N = 1120, 74.1 (5.7) |

48.5%, CD (97.9%) and institutionalised (2.1%), S | MN (BMI < 20 kg/m2 or SR invol. WL ≥ 5% in previous 6 m) |

Demographic: sex, age, education Food Intake: appetite, chewing difficulties Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption, PA (LAPAQ) Social: loneliness Physical functioning: limitations climbing stairs, physical performance (chair stands, tandem stand and walk test) Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE), depression (CESD), anxiety (HADS) Disease-related: medication use, SR pain, chronic diseases |

3, 6, 9 y |

cox proportional-HR UV LR MV LR |

poor appetite [1.63 (1.02–2.61) p < 0.05]; difficulties climbing stairs (in those < 75 y only) [HR (95% CI) 1.91 (1.14–3.22)]; one or two medications (vs none in females only) [HR (95% CI) 0.39 (0.18–0.83) p < 0.05] |

| Jyrkka [78], 2011, Finland, N = 294, 81.3 (4.5) | 31%, CD (94.6%) and institutionalised (5.4), U | MN risk (MNA-SF) |

Demographic: age, sex, education, residential status (home vs institution) Physical function: functional comorbidity index Disease-related: polypharmacy, SR health |

3 y | Linear mixed model approach | excessive polypharmacy 0.62 points lower MNA-SF scores (p < 0.001); age [ẞ (standard error) p-value; − 0.04 (0.02) p = 0.016]; institution [− 1.89 (0.25) p < 0.001]; moderate [− 0.27 (0.11) p = 0.016] and poor [− 1.05 (0.17) p < 0.001] SR health status |

| Johansson Y [43], 2009, Sweden, N = 579, 75 y and 80 y cohort | 52.5%, CD, N/A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age Physical functioning: HGS, physical mobility (NHP), walking limitations, limitations climbing stairs, physical health (PGC-MAI) b Psychological: depression (GDS), cognitive impairment (MMSE) Disease-related: SR health, pain (NHP) |

75 y olds: yearly for 5 y 80 y olds: yearly for 3 y |

forward stepwise multiple LR | higher age p = 0.005 at 1 y; HGS [0.938 (0.91–0.97) p < 0.001]; physical health [0.65 (0.55–0.76) p < 0.001] predicted risk of MN at baseline; more depression symptoms [1.178 (1.07–1.30) p = 0.001] 1 y predictor; depressive symptoms*males [OR 1.26] depressive symptoms*females [OR 1.03]; lower SR health [0.432 (0.27–0.70) p = 0.001] |

| Johansson L [95], 2009, Sweden, N = 258, 74.2 (2.55) | 49.6%, CD, A | MN risk (MNA) |

Social: social support Physical functioning: ADLs Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE) Disease-related: SR health, hospitalisation |

4, 8, 12 y |

UV LR MV LR |

Total: MOW use [OR 19.6, p < 0.001]; Males; use of MOW [OR 21.9, p < 0.01]; MMSE score (cut-off 23/24) [12.9 (2.9–56.7) p < 0.01]; poorer SR health compared to 4 y ago [OR 5.1, p < 0.05] Females: increased MOW use [OR 31.0, p < 0.01]; hospital stay during the past 2 m [OR 7.1, p < 0.05] |

| Keller [96], 2006, Canada, N = 367, 78.7 (8.0) | 24%, vulnerable CD c, A | MN risk (SCREEN) | Social: social support- MOW use | 1.5 y | multiple linear regression | MOW use associated with a 1.6-point higher score in SCREEN at FU [(0.02–3.23) p = 0.04]; increasing help making meals [(2.91–0.49) p = 0.006] |

| Visvanathan [47], 2003, Australia, N = 250, 79.45 (no SD) | 30.8%, CD receiving domiciliary care (all had MMSE > 24), A | MN risk (MNA) |

Demographic: age Lifestyle: smoking status Social: MOW use, amount of domiciliary care per m Disease-related: comorbidities, health status and QOL (SF-36) |

1 y | UV LR binomial analysis | hospitalisation [RR 1.51 (1.07–2.14) p = 0.015], > 2 emergency hospitalisation [RR 2.96 (1.17–7.50) p = 0.022], > 4 week hospitalisation [RR 3.22 (1.29–8.07) p = 0.008], falls [RR 1.65 (1.13–2.41) p = 0.013], WL [RR 2.63 (1.67–4.15) p < 0.001], > 2 hospitalisations [RR 2.11 (1.04–4.29) p = 0.039], emergency hospitalisation [RR 1.99 (1.28–3.11) p = 0.002] |

| Shatenstein [86], 2001, Canada, N = 584, > 70 y (no mean given) | 40.4%, CD, N/A | MN risk (WL > 5% baseline weight) | Demographic: age, study region, WL Social: ability to shop, bereavement Psychological: cognitive diagnosis at FU, depression, SR interest in life Food Intake: ability to eat independently, loss of appetite Physical functioning: frailty | 5 y | MV LR (backward stepwise) | consistent appetite [0.22 (0.12–0.42) p < 0.001]; loss of interest in life [0.56 (0.34–0.90) p = 0.017] |

|

Ritchie [97], 2000, America, N = 563, Males: 77.3 (4.7), Females: 78.1 (5.3) |

43%, CD, N/A | MN (WL > 10% BW) |

Demographic: age, sex Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption, PA Food Intake: edentulousness, wears full prostheses, % sites with gingival bleeding, mean attachment loss, mean recession Disease-related: > 2 comorbidities Physical functioning: ADLs Psychological: depression |

1 y |

UV LR MV LR |

female sex [3.77 (1.71–8.33) p < 0.05], baseline weight [1.02 (1.01–1.03) p < 0.05]; dependent in > 1 ADL [2.27 (1.08–4.78) p < 0.05]; edentulousness [2.03 (1.05–3.96) p < 0.05] |

| Systematic Review | ||||||

|

O’Keeffe [98], 2018, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Israel, Japan, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, USA, 23 studies N = 108–4512, 74 (12) |

17–53.5%, N = 15 CD, N = 3 institutionalised, N = 3 acute hospital, N = 2 CD and institutionalised combined, N/A | MN (any definition/screening tool) |

Food intake: appetite, complaints about taste, nutrient intake/modified texture diet, hunger, thirst, dental status, chewing, mouth pain, gum issues, swallowing, eating dependency/difficulty feeding Psychological: cognitive function, depression, psychological distress, anxiety Social: social support, living situation, transport, loneliness, wellbeing, MOW, vision and hearing Disease-related: medication use, polypharmacy, hospitalisation, comorbidities, constipation, SR health Physical functioning: ADLs Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol consumption, PA |

24 weeks- 12 y | Mixed |

Moderate evidence for association: hospitalisation, eating dependency, poor SR health, poor physical function, poor appetite Moderate evidence for no association: chewing difficulties, mouth pain, gum issues, comorbidity, hearing and vision impairments, smoking, alcohol consumption, low PA, complaints about taste of food, specific nutrient intakes Low evidence determinants: modified texture diets, loss of interest in life, MOW access Low evidence not determinants: psychological distress, anxiety, loneliness, access to transport, wellbeing, hunger, thirst Conflicting evidence: dental status, swallowing, cognitive function, depression, residential status, medication intake and/or polypharmacy, constipation, periodontal disease |

|

van der Pols-Vijlbrief [34], 2014 USA, Canada, Netherlands, Sweden, Cuba, France, Japan, Brazil, UK, Israel, Russia, 28 studies N = 49–12,883, mean > 65y |

21.3–56.5%, CD, N/A |

PEM (WL over time/ low nutritional intake/ low BW/ poor appetite) |

Demographic: sex, age, education Food Intake: reduced appetite, edentulousness, chewing difficulties Lifestyle: PA, alcohol use, smoking Social: few friends, living situation, loneliness, death of spouse Physical functioning: ADLs Psychological: depression, cognitive decline, dementia, anxiety Disease-related: hospitalisation, SR health status, polypharmacy, chronic diseases, cancer |

N/A | MV analyses |

Association: poor appetite Moderate evidence for an association: edentulousness, hospitalization, SR health moderate evidence for no association: older age, low education, depression, chronic diseases Strong evidence for no association: few friends, living alone, loneliness, death of spouse No association: chewing difficulties, alcohol consumption, anxiety, number of diseases, heart failure, use of anti-inflammatories Inconclusive: sex, low PA, smoking, ADL dependency, cognitive decline, dementia, polypharmacy |

| Meta-analysis | ||||||

|

Streicher [33], 2018, 6 studies: Germany (30, Ireland (1), Netherlands (1), New Zealand (1), N = 209–1841, 71.7 (5.0)- 84.6 (0.5) |

36.6–50.5%, CD, N/A | MN (BMI < 20 kg/m2 or WL > 10% over FU) |

Demographic: age, sex, marital status, education Social: living alone, social support Lifestyle: PA, smoking status, alcohol consumption Disease-related: comorbidities (> 2), hospitalisation (6 m/1 y before baseline and 6 m/1 y before FU), pain, SR health, polypharmacy (> 5 drugs) Psychological: cognitive impairment (MMSE < 23, TICS-m < 31), depression (GDS > 6, CES-D > 16, HADS > 8) Physical functioning: difficulty walking, difficulty climbing stairs, HGS, falls (y before baseline and 1 y/2 y before FU) Food intake: appetite |

1–3 y | LR analyses (UV and MV), random-effects meta-analyses | increasing age [1.05 (1.03–1.07) p < 0.05]; unmarried, separated, or divorced status [1.54 (1.14–2.08) p < 0.05]; difficulty walking 100 m [1.41 (1.06–1.89) p < 0.05]; difficulty climbing stairs [1.45 (1.14–1.85) p < 0.05]; hospitalisation before baseline [1.49 (1.25–1.76) p < 0.05]; hospitalisation during FU [2.02 (1.41–2.88) p < 0.05] |

A accelerated, AACI Charlson’s Age Adjusted Co-Morbidity Index, ADL activities of daily living, AGGIR Autonomy, Gerontology and Group Resources Scale, ANOVA analysis of variance, ANSI Australian nutritional screening initiative, BI Barthel Index, BMI body mass index, BOHSE Brief Oral Health State Examination, BP blood pressure, BW body weight, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, CD community dwelling, CDS chronic disease score, CESD center for epidemiologic studies depression scale, CHD coronary heart disease, CI confidence interval, CIDI Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CNAQ Council on Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire, CPS Cognitive performance scale, CRP C-reactive protein, CVD cardiovascular disease, DM diabetes mellitus, EAT-10 Eating Assessment Tool-10, EI energy intake, ENS elderly nutrition screening, EPI Eysenck Personality Inventory, EQ-5D euro quality of life- 5 dimension, ESDS Enforced Social Dependency Scale, FFMI fat free mass index, FTSTS Five-times-sit-to-stand test, FU follow up, GDS geriatric depression scale, GFI Groningen Frailty Index, GOHAI Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index, GP general practitioner, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HDDS Household Dietary Diversity Score, HEI Healthy Eating Index, HFIAS Household Food Insecurity Access Scale, HGS handgrip strength, HR hazards regression, HTAQ Health and Taste Attitudes Questionnaire, HUI Health Utility Index, IADL instrumental activities of daily living, invol involuntary, IM-E-SA INTERMED questionnaire for the Elderly Self-Assessment, IQCODE Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, IQR interquartile range, LAPAQ Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA)-Physical Activity Questionnaire, lb pound, LR logistic regression, LSNS-6 Lubben social network scale-6, m months, MAG Malnutrition Advisory Group, MCI mild cognitive impairment, MCS mental component score, MEDAS Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screen, MI myocardial infraction, min minute, MMSE mini mental state examination, MN malnutrition, MNA mini nutritional assessment, MNA-SF mini nutritional assessment- short form, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MOS Medical Outcomes Study, MOW meals on wheels, MUAC mid-upper arm circumference, MUST malnutrition universal screening tool, MV multivariate, NEADL Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living, NHP Nottingham health profile, NIDS National Irish Deprivation Score, NRS-2002 Nutritional Risk Screening, NUFFE Nutritional Form For the Elderly, NUFFE-NO Norwegian version of the Nutritional Form For the Elderly, OARS Older Americans Resources and Services, OHQ oral health questionnaire, OR odds ratio, OSLO 3-SSS Oslo 3 item social support scale, PA physical activity, PASE Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly, PCS physical component score, PEM protein energy malnutrition, PGC MAI Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Multilevel Assessment Instrument, QOL quality of life, RR risk ratio, S successful, SASE Self-care Ability Scale for Elderly, SC senior centre, SCL-10 symptoms check list- 10, SCREEN Seniors in the community: Risk Evaluation for eating and Nutrition, SD standard deviation, SEM structural equation modelling, SF-12 short form survey-12, SF-36 short form survey-36, SHPS Subjective Health Perceptions Scale, SNAQapp Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire, SNAQ65+ Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire for over 65 s, SOC Sense of coherence scale, SOF Study of osteoporotic fractures, SPMSQ Short-Portable Mini-Mental Status Questionnaire, SR self rated, SSQSF Social Support Questionnaire- Short Form, STAI Y-B State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y, TICS-m modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status, TUG Timed Up and Go, U usual, U-A usual to accelerated, U-S usual to successful, UCLA University of California at Los Angles, UV univariate, VA Veterans Administrative, VAS visual analogue scale, WC waist circumference, WHOQOL world health organisation quality of life scale, WL weight loss, y years, 3MS Modified Mini-Mental State

a answering ‘yes’ to either an ADL/IADL was categorised as ‘need’; b assessed using PGC-MAI: measures cognition, physical health, mobility, ADLs, time use, personal adjustment, social interaction and environmental domains; c dependent for activities of daily living (grocery shopping, transportation, cooking, or self-care); *Key results are only presented for multivariate analyses

Categorisation of studies according to rate of ageing

Nine studies were classified as ageing at a usual rate [35, 36, 39, 49, 63, 66, 70, 84, 99]. Three studies were classified as ageing successfully and five studies were categorised as ageing at an accelerated rate. Six studies were placed between the successful and usual ageing groups [34, 41, 42, 45, 68, 100] and five studies were placed between the usual and accelerated ageing categories [38, 44, 53, 77, 93]. In order to include as many studies as possible in our results, studies classed within the usual to successful ageing category were collapsed into the successful ageing category [21, 85, 87] whilst studies within the usual to accelerated category were collapsed into the accelerated ageing category [40, 46, 94–96] (Fig. 2). Forty studies remained uncategorised so were omitted from the synthesis of studies by ageing rate; however, the details of each of these studies are described in Table 2. Primary reasons for not categorising studies included lack of information on presence of chronic diseases, polypharmacy, functionality, frailty or use of social or medical services not being provided or that the study included multiple cohorts (details of all studies included in this review are within Table 2).

Factors associated with, and determinants of, malnutrition

Factors in the demographic and disease-related domains were most-commonly examined (63 and 54 studies respectively), followed by the social (50 studies), psychological and physical functioning domains (46 studies each) (Table 2). Factors under the food intake and lifestyle domains were the least well studied (32 and 20 studies respectively). The factors most-commonly reported to be associated with malnutrition were within the demographic (41 studies), disease-related (34 studies), physical functioning (30 studies) and psychological (30 studies) domains. Domains less commonly reported as associated with malnutrition were the social (27 studies), food intake (23 studies) and lifestyle (7 studies). The evidence for individual factors within each domain is critically considered.

The frequency of factors reported as associated with malnutrition according to the rate of ageing category is presented in Table 3. In this review, demographic factors such as being female (successful, N = 2; usual, N = 1; accelerated, N = 1) and increasing age (successful, N = 2; usual, N = 3; accelerated, N = 1) were commonly reported as associated with malnutrition/malnutrition risk across all ageing rate categories. Other demographic (unmarried status (N = 4) [42, 45, 85, 100] and a low education level (N = 2) [34, 68]) and physical functioning factors were more commonly reported within the successful ageing category compared to the other ageing rate categories. Factors within the food intake and disease-related domains were most-commonly reported in older adults who are ageing at an accelerated rate.

Table 3.

Factors associated with malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults stratified by ageing rate

| Domain | Successful (N = 9) | Usual (N = 9) | Accelerated (N = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Female (2), marital status (4), age (2), BMI (1), education (2), ethnicity (1) | Age (3), BMI (3), WL (1), measures of fat mass (1), female (1), marital status (2), rural location (1) | Female (1), age (1), unintentional WL (1), rural location (1), ethnicity (1), marital status (1) |

| Lifestyle | PA (1) | Alcohol (1) | Smoking (1), PA (1) |

| Food Intake | Appetite (1), food insecurity (1) | Appetite (1), oral health (1), illness which affects food intake (1), normal swallow (RR) (1), choosing food that’s easy to chew (1) | Appetite (2), < 3 snacks per day (1), oral health (1), eating difficulty (1), eating dependency (1) |

| Social | Social support (2), living situation (1), income (1) | Living alone (2), living with another adult (1), income (3), low social support (2), social isolation (2), requiring assistance to travel (1), availability of reliable transport (1), religious attendance (1), fear of attack (1), fear discrimination (1) | Income (1), MOW (2), increasing use of MOW (1), help making meals (1) |

| Physical Functioning | difficulty walking/climbing stairs (2), falls (1), orthopaedic disability (1) | Healthy physical performance (1), IADL (1), moderate/severe disability (1) | Unable to go outside (1), ADL (2), functional status (1), falls (1), IADL (RR) (1) |

| Psychological | Cognitive impairment (1), depression (1), mental health (1) | Dementia (1), depression (2) | Depression (2), dementia (1), mental overload (1), cognitive impairment-men (1) |

| Disease-related | SR health (2), hospitalisation (1), low medication use (RR vs none) (1), multi-morbidity (2), QoL (1), physical health (1) | Polypharmacy (3), SR health (2), institutionalisation (1), not regularly attending GP (RR) (1), health problems (1), general health status (1) | Intestinal problems (1), multi-morbidity (1), osteoporosis (1), nausea (1), cancer (1), health related QoL (1), poor SR health (1), hospitalisation (2), > 2 emergency hospitalisation (1), hospital stay > 4 weeks (1) |

ADL activities of daily living, MOW meals on wheels, PA physical activity, QoL quality of life, RR reduced risk, SR self-rated, WL weight loss

Bold text indicates factors which are more frequently reported as the rate of ageing increases

This review found that factors reported to be associated with malnutrition from the food intake domain increased in frequency and severity across the three ageing categories (successful, usual, accelerated). Food insecurity was reported as a risk factor in the successfully ageing category [42], choosing foods that were easy to chew was a risk factor in the usual ageing category [39], whilst difficulties eating and eating dependency were associated with malnutrition risk in the accelerated ageing category [77]. Having a poor or reduced appetite is reported as being associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk across all categories of ageing rate [39, 44, 77, 87].

Within this review, lifestyle factors were rarely reported as being associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in any of the ageing categories. Lack of physical activity was reported once in both the successfully [68] and accelerated [46] ageing categories. Alcohol use was reported as being associated with a lower risk of malnutrition once within the usual ageing category [49]. Smoking was reported to be associated with malnutrition in one study from the accelerated ageing category [46].

Cognitive impairment, a factor within the psychological domain was reported as being associated with malnutrition by one study in the successful ageing category [85], whilst dementia was reported as associated with malnutrition risk in both the usual (N = 1) [36] and accelerated (N = 2) [53, 94] ageing categories. Depressive symptoms were reported in the successful ageing (N = 2) [34, 45], usual ageing (N = 3) [35, 36, 49] and accelerated ageing (N = 2) [38, 53] categories.

Indicators of declining mobility (difficulty walking 100 m and difficulty climbing a flight of stairs) were reported in the successful ageing category only (N = 2) [85, 87]. Factors indicative of physical dependency (being unable to go outside) were reported in one study from the accelerated ageing category [46]. Falls were reported to be associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in the successful ageing (N = 1) [85] and accelerated ageing (N = 1) [96] categories.

Living with others was associated with reduced risk of developing malnutrition in the successful ageing category (N = 1) [45], whilst living alone was associated with increased risk of malnutrition risk in the usual ageing category (N = 2) [35, 39]. Social support was reported to be associated with malnutrition or malnutrition risk in both the successful (N = 2) [85, 100] and usual (N = 2) [35, 99] ageing categories.

This review found factors from the disease-related domain were commonly reported across all ageing rate categories but increased in severity as the ageing rate progressed into the accelerated ageing category. Recent hospitalisation was reported in the successful (N = 1) [85] and accelerated (N = 2) [94, 96] ageing categories. Factors such as multi-morbidity were more commonly reported in the successful ageing category (N = 2) (N = 0, usual ageing category, N = 1, accelerated ageing category) whilst individual diseases such as cancer and osteoporosis (N = 1) [46] and extended hospital stays (N = 1) [96] were reported in the accelerated ageing category.

Discussion