Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of the study was to investigate post-mortem changes in dogs infected with Babesia canis and to establish the probable cause of death of the affected animals.

Material and Methods

Cadavers of six dogs that did not survive babesiosis were collected. Necropsies were performed and samples of various organs were collected for histological examination.

Results

Necropsies and histological examinations revealed congestion and oedemata in various organs. Most of the dogs had ascites, hydrothorax or hydropericardium, pulmonary oedema, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, and cerebral congestion, and necrosis of cardiomyocytes.

Conclusion

These results suggested disorders in blood circulation as the most probable cause of death. However, the pulmonary inflammatory response and cerebral babesiosis observed in some of these dogs could also be considered possible causes of death. This study also showed a possible role for renal congestion in the development of renal hypoxia and azotaemia in canine babesiosis.

Keywords: Babesia canis, canine babesiosis, cerebral babesiosis, pulmonary oedema, renal congestion

Introduction

Canine babesiosis is a disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia. The disease results from the infection of dogs with species such as Babesia canis, B. vogeli, B. rossi, B. gibsoni, B. conradae, B. vulpes, and at least one unnamed large Babesia species (19). The infection may lead to injury of many internal organs and may result in systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The disease is considered to be protozoan sepsis (21). There are several studies on the histological changes observed in the internal organs of affected dogs. However, only a few of them present results from dogs infected specifically with B. canis, and the results of most of these works are based on single case reports or a low number of examinations of dogs (1, 4, 11, 29, 30). The aim of this study was to investigate post-mortem pathological changes observed in dogs infected with B. canis to establish the probable cause of death of the affected dogs.

Material and Methods

Cadavers of six dogs of various breeds (three males and three females, 4 months to 8 years old), which had been naturally infected with B. canis, hospitalised in two veterinary clinics and treated with imidocarb dipropionate before their deaths, were collected from March 2013 to May 2017. During this time the authors diagnosed 272 cases of canine babesiosis. Among them, 17 dogs did not survive the disease. The owners of 11 of them did not agree to post-mortem examinations being performed, but those of six did give their consent. These six canine babesiosis fatalities were the dogs investigated. Depending on the clinical status, the treatment of the dogs had also included intravenous fluids, furosemide, dopamine, dexamethasone, dextrose, and oxygen inhalation. Moreover, one dog with epileptic seizures had also been treated with diazepam, pentobarbital, and mannitol. Diagnosis of the infection was based on blood smear examination and confirmed by the PCR technique described in detail by Zygner et al. (44). Determination that the infection was not Anaplasma phagocytophilum (the second most prevalent tick-borne canine pathogen in Poland) was based on the results of the PCR method described in a previous study (36, 40). The duration of the disease before any treatment was between 1 and 3 days (Table 1). According to the information provided by the owners of the dogs, no signs of any disease had been observed before babesiosis. Blood samples were collected from all of the six dogs before treatment. Biochemical parameters such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities and urea, creatinine, glucose, total bilirubin, total protein, and albumin concentrations were determined in serum samples using a clinical chemistry analyser (XL 640, Erba Mannheim, Germany). Complete blood counts were determined in blood samples with anticoagulant (ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid) using a haematological analyser (Abacus, Diatron, Budapest, Hungary). All six dogs died within 1 to 2 days of hospitalisation and none was euthanised. After death, the bodies of the dogs were kept at 4°C until necropsy, which was undertaken within 6 to 24 hours. Samples of the brain, cardiac muscle, lungs, kidneys, liver, pancreas, spleen, stomach, small intestines, and mesenteric lymph nodes were collected for histological examination. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned to 5 μm, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (routine morphological staining), by Masson’s technique (for visualisation of the connective tissue), and by Perls’ technique (for demonstration of ferric iron salts).

Table 1.

Results of clinical examination, serum biochemical changes and haematological changes observed in six dogs infected with B. canis during the first visit to the clinic

| Dog No. | Description | Basic serum biochemical changes | Basic haematological changes | Clinical signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Border collie, M, 1 y old | ALT 64, AST 206, ALP 153, T. Bil. 1.24, Glu. 97, Creat. 2.1, Urea 204, T. Prot. 63, Alb. 26 | RBC 5.97, Hb 8.76, Ht 0.39, WBC 3.40, Plt 48 | Apathy, anorexia, diarrhoea, dehydration, pale mucosal membranes, normal body temperature, dark brown urine, DD 2 days |

| II | Mixed breed, F, 8 y old | ALT 127, AST 618, ALP 790, T. Bil. 6.25, Glu. 156, Creat. 14.2, Urea 393, T. Prot 54, Alb. 25 | RBC 3.07, Hb 8.53, Ht 0.20, WBC 29.8, Plt 152 | Apathy, anorexia, diarrhoea, vomiting, dehydration, pale and yellow mucosal membranes, normal body temperature, oliguria (yellow urine), DD 3 days |

| III | Mixed breed, M, 4 m old | ALT 46, AST 117, ALP 124, T. Bil. 1,14, Glu. 72, Creat. 3.8, Urea 331, T. Prot. 41, Alb. 20 | RBC 1.54, Hb 2.18, Ht 0.09, WBC 9.14, Plt 7 | Apathy, anorexia, diarrhoea, vomiting, dehydration, pale mucosal membranes, tachycardia, hyperventilation, vocalisation, normal body temperature, oliguria (dark brown urine), DD 1 day |

| IV | St. Bernard, F, 7 y old | ALT 49, AST 273, ALP 119, T. Bil. 0.9, Glu. 195, Creat. 5.1, Urea 264, T. Prot. 58, Alb. 26 | RBC 6.56, Hb 9.56, Ht 0.42, WBC 6.7, Plt 41 | Apathy, anorexia, diarrhoea, epileptic seizures, menace deficit and lack of PLRs in both eyes, tachycardia, hyperventilation, congestion of mucosal membranes, fever (40.2°C), haematuria, DD 2 days |

| V | American Staffordshire terrier, M, 7 y old | ALT 200, AST 103, ALP 1408, T. Bil. 8.7, Glu. 103, Creat. 3.8, Urea 277, T. Prot. 69, Alb. 30, | RBC 4.34, Hb 5.59, Ht 0.30, WBC 11.0, Plt 133 | Apathy, anorexia, vomiting, dehydration, yellow mucosal membranes, fever (39.5°C), oliguria (dark brown urine), DD 3 days |

| VI | Siberian husky, F, 7 m old | ALT 61, AST 116, ALP 198, T. Bil. 1.41, Glu. 105, Creat. 1.0, Urea 39, T. Prot. 55, Alb. 26 | RBC 4.09, Hb 6.16, Ht 0.27, WBC 4.1, Plt 32 | Apathy, anorexia, pale mucosal membranes, fever (40.0°C), dark brown urine, DD 1 day |

M – male; F – female; m – months; y – years; ALT – alanine aminotransferase (reference interval 3–60 U/L); AST – aspartate aminotransferase (reference interval 1–45 U/L); ALP – alkaline phosphatase (reference interval 20–155 U/L); T. Bil. – total bilirubin (reference interval 0.3–0.9 mg/dL); Glu – glucose (reference interval 70–120 mg/dL); Creat. – creatinine (reference interval 0.8–1.7 mg/dL); Urea (reference interval 20–45 mg/dL); T. Prot. – total protein (reference interval 55–75 g/L); Alb. – albumin (reference interval 29–43 g/L); RBC – red blood cells (reference interval 5.5–8.0 T/L); Hb – haemoglobin (reference interval 7.45–11.17 mmol/L); Ht – haematocrit (reference interval 0.37–0.55 L/L); WBC – white blood cells (reference interval 6.0–12.0); Plt – platelets (reference interval 200–580 G/L); DD – duration of the disease (according to the owner of the dog) before the first visit to the clinic; PLRs – pupillary light reflexes

Results

All six studied dogs required hospitalisation when brought to the clinics. Determination of serum biochemical parameters and complete blood counts showed renal involvement, hepatopathy and anaemia (Table 1). In one dog (No. IV) epileptic seizures were the main clinical sign that suggested cerebral babesiosis.

In three dogs, the mucosal membranes were changed: two had yellow mucosal membranes (Nos II and VI), and one had cyanosis of this tissue (No. I). In three dogs, (Nos III, V, and VI) ascites and hydrothorax were observed.

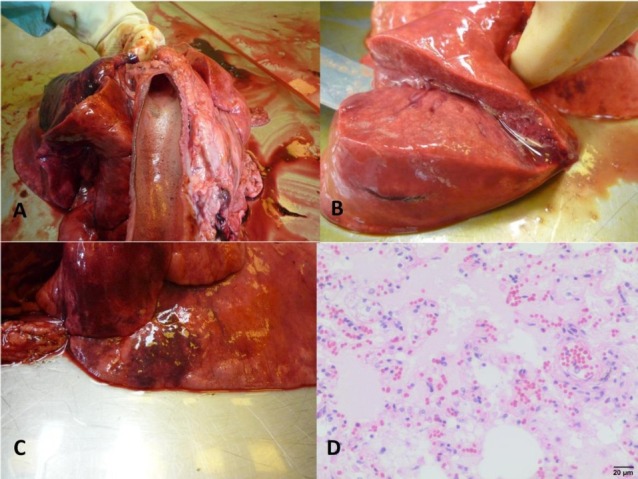

Lungs. Pulmonary oedema and congestion were observed in all the dogs (Fig. 1). Histological examination of the lungs also showed emphysema in four dogs, interstitial inflammation in three, subpleural fibrosis in three and the presence of thrombi in one animal. Moreover, the presence of siderophages was observed in four dogs, atelectasis in one and anthracosis in three.

Fig. 1.

Pulmonary changes in dogs infected with B. canis

A – Foamy exudate in the trachea of dog No. II; B – Pulmonary oedema in dog No. II; C – Pulmonary congestion and foci of emphysema in dog No. IV; D – Microphotograph of pulmonary oedema in dog No. VI, visible oedema fluid filling alveoli and dilatation of blood vessels (haematoxylin and eosin staining)

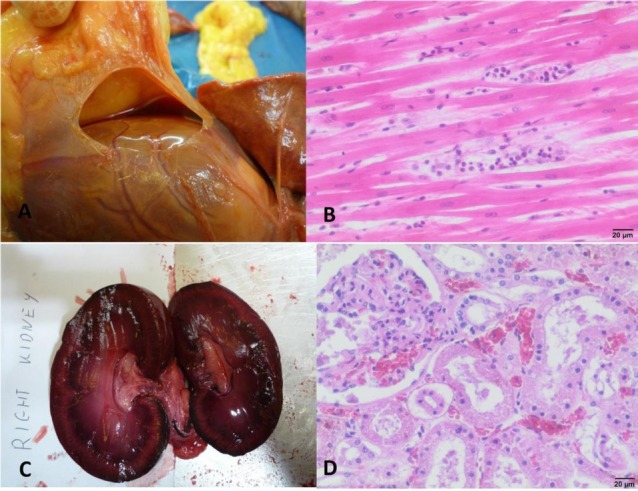

Heart. All six necropsies showed cardiac pathology. Hydropericardium was observed in three dogs (Fig. 2), hypertrophy of the left ventricle wall in two, endocardiosis of the bicuspid valve in three, clots in the left ventricle in two, subepicardial extravasations in the wall of the left ventricle in one animal, and dilatation of the right ventricle in one of the subjects. Histological examination showed multifocal necrosis of cardiomyocytes in all six dogs (Fig. 2). Mononuclear cell infiltration was observed in two dogs, hyperaemia and extravasations were observed in two, and multifocal fibrosis was observed once.

Fig. 2.

Cardiac and renal changes in dogs infected with B. canis

A – Hydropericardium observed in dog No. II; B – Necrosis of the myocardium, visible fragmentation of cardiomyocytes and inflammatory infiltration in dog No. VI (haematoxylin and eosin staining); C – Congested right kidney of dog No. IV; D – Congestion of renal cortex and tubular necrosis in dog No. I (haematoxylin and eosin staining)

Kidneys. Biochemical examination during the first visit to the clinics showed renal involvement in five out of six dogs (No. VI being the unaffected patient). However, in dog No. VI, azotaemia developed within 12 hours of admission to the clinic. On gross examination, the kidneys of five dogs were congested (Fig. 2). The presence of dark brown urine was observed in the urine bladder of one dog (No. III), and petechiae in the bladder of another (No. V). Histological examination of the kidneys of the dogs showed necrosis of the tubule cells in all cases (Fig. 2), interstitial inflammation in three cases, the presence of haemoglobin in the lumen of the tubules in two dogs (Nos I and III), presence of haemoglobin in the tubule cells in three (Nos I, II, and VI), proteinuria in five, congestion and focal extravasations in four animals, and glomeruli necrosis in one (No. I). Dog No. VI also had renal fibrosis and cysts (as a result of chronic inflammation), and erythrocytic casts were present in the lumen of the tubules.

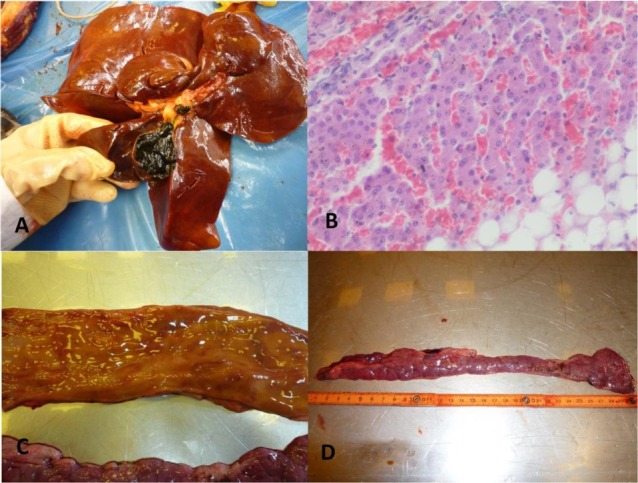

Liver. The necropsies showed ubiquitous liver pathology. Lipid degeneration was observed in four livers, congestion in three, nutmeg liver in two dogs, and concentrated (almost solid) bile in the gallbladder in one dog (Fig. 3). Icterus was visible in two cadavers. Histological examination showed lipid degeneration of hepatocytes in all samples, necrosis of hepatocytes in four of them, congestion in four, presence of bile pigment in hepatocytes in three, infiltration of mononuclear cells in two, fibrosis around the portal triad in four, and cholestasis and the presence of siderophages in one liver section (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Changes in the alimentary system in dogs infected with B. canis

A – Congestion and lipid degeneration of the liver with almost solid bile in the gallbladder in dog No. II; B – Microphotograph of liver congestion and lipid degeneration of hepatocytes in dog No. I (haematoxylin and eosin staining); C – Petechiae in the mucosal membrane of duodenum in dog No. IV; D – Congestion of the pancreas in dog No. IV

Pancreas. In three dogs, necropsy and histological examination showed congestion (Fig. 3), and in one dog histological examination showed hypertrophy of the connective tissues.

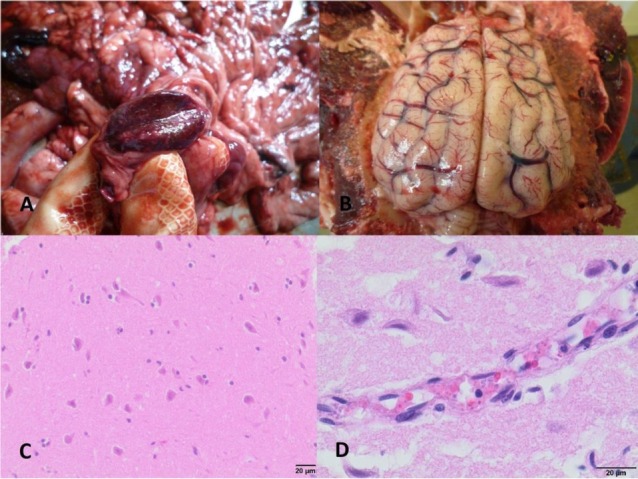

Stomach, small intestine, and mesenteric lymph nodes. In four instances, petechiae were observed in the mucosal membranes of the small intestine and/or the stomach (Fig. 3). One dog was infected with Toxocara canis. Histological examination revealed one case of chronic inflammation of the small intestine. Congestion of mesenteric lymph nodes was observed in three necropsies and histological examinations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Changes in the mesenteric lymph nodes and the brain in dogs infected with B. canis

A – Congestion of the mesenteric lymph node in dog No. IV; B – Congestion of the brain and brain meninges in dog No. IV; C – Microphotograph of the brain, visible neuronal degeneration and necrosis, and neuronophagia in dog No. I (haematoxylin and eosin staining); D – Microphotograph of the brain, visible brain oedema and sequestration of B. canis-infected red blood cells in cerebral capillary vessels in dog No. IV (haematoxylin and eosin staining)

Spleen. Splenomegaly and hyperaemia of the spleen was observed without exceptions. Histological examination also revealed atrophy of the lymphoid follicles in three dogs (Nos II, V, and VI), and the presence of siderophages in the same number of dogs (Nos I, II, and VI).

Brain. Necropsies revealed congestion of the brain on two occasions and congestion of the meninges in four cases (Fig. 4). Histological examination of the brain showed congestion in five dogs and oedema in all six dogs. Moreover, focal extravasations were observed in four brain samples, neuronal necrosis and degeneration was observed in all of them, microglia proliferation in two, and neutrophil infiltrations in one (Fig. 4). Merozoites and trophozoites of B. canis inside red blood cells were detected in the capillary vessels of the brain of dog No. IV (Fig. 4).

Discussion

It seems obvious that all dogs included in this study had acute severe complicated babesiosis, which caused death in a short time, and most of the pathologies observed in these animals resulted from such a course of the disease. It was shown in previous studies that babesiosis of this form resulted mainly from overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and was associated with high mortality (16, 25, 42, 43). Some changes and chronic progressing pathologies, such as pulmonary anthracosis, fibrosis, hypertrophy of the wall of the left ventricle, endocardiosis of the bicuspid valve, nutmeg liver, or chronic renal interstitial inflammation did not result from the infection. However, these changes might have an influence on the course of babesiosis and its outcome in dogs with these pathologies.

Pulmonary oedema and congestion were observed in all dogs. In canine babesiosis, pulmonary oedema may result from disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, and damage of type I pneumocytes by free radicals (16, 28, 35, 42, 43). These factors lead to the noncardiogenic permeability type of pulmonary oedema, which occurs in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) as previously observed in canine babesiosis (11, 14, 28). Acute pancreatitis, which was described in a previous study on canine babesiosis, may also trigger ARDS (28, 32). Moreover, in dog No. IV epileptic seizures might have led to the development of neurogenic pulmonary oedema caused by rapid systemic hypertension (6). On the other hand, the cardiac pathology and hypoalbuminaemia observed in dogs in this study might influence the development of the usually cardiogenic hydrostatic type of pulmonary oedema (12, 28). The presence of siderophages in the lungs of four dogs in this study may confirm the congestion of this organ. This suggests cardiac involvement in the development of pulmonary oedema (28). Cardiogenic pulmonary disorders in these dogs can also be confirmed by the presence of hydrothorax in three dogs, and multifocal necrosis of cardiomyocytes and other cardiac pathologies observed in all six dogs. Similar changes were also previously observed in dogs infected with Babesia rossi (12). According to Dvir et al. (12), these myocardial changes in canine babesiosis may result from hypoxia, inflammation and DIC. Although cardiac disorders seemed to have little clinical significance in most cases of dogs infected with B. canis in a previous study, in fatal cases cardiac and vascular disorders may have had a key influence on the course of the disease (3).

In this study pneumonitis was observed in three dogs, and was probably associated with ARDS, in which overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines causes release of cytotoxic enzymes and free radicals from pulmonary neutrophils, leading to injury of endothelial cells. Moreover, DIC might also have had an influence on the development of interstitial pneumonia in these dogs. This pathology might have led to the development of pulmonary oedema in these cases (11, 16, 28, 35). The emphysema observed in four animals and atelectasis in one might have resulted from inflammation or from these dogs’ other earlier diseases.

Tubular necrosis was ubiquitous. This pathology was also observed in previous studies on histological lesions in the kidneys of dogs infected with B. canis in Hungary and in one dog infected with an unnamed large Babesia species (according to the authors, probably B. canis) in France (11, 29). However, in the study from Hungary, like in a previous study on dogs infected with the less pathogenic species B. vogeli from Australia, the main changes that were observed in renal tubules were degenerations (20, 29). In two other works on B. canis-infected dogs no tubular changes were detected (1, 4). In this study, the presence of haemoglobin in the tubule cells was observed in three samples and the presence of haemoglobin in renal tubules was detected in two. Haemoglobin itself is not considered nephrotoxic (33). Lobetti et al. (27) showed that haemoglobinaemia in dogs infected with B. rossi did not induce significant nephropathy. Notwithstanding this, free haemoglobin in the glomerular filtrate and haemoglobinuria are considered factors that may exacerbate tubular necrosis in hypoxic kidneys (33).

Both tubular degenerative changes and necrosis of tubular cells result from renal hypoxia (33). Tubular necrosis in all six dogs suggests that tubular changes could be more advanced and severe in the dogs in this study than in the dogs in the previous study from Hungary, where canine babesiosis was also caused by B. canis. Yet, it is also possible that babesiosis in the Hungarian study may have been caused by a less pathogenic strain of this species of parasite. In this study, tubular changes probably resulted from decreased renal blood flow, which may be associated with decreased cardiac output (10). This seems to result from cardiac pathologies in canine babesiosis (12). It has been shown in humans that decreased intraoperative arterial blood pressure may also have an influence on renal blood flow and acute kidney injury (38), and a previous study on canine babesiosis showed an association between arterial hypotension and renal azotaemia (42). Thus, hypotension should have an influence on renal ischaemia, hypoxia, and the development of acute renal failure (41). However, this study showed no renal ischaemia, as the kidneys of five out of six dogs in this study were congested. Renal congestion is associated with heart failure and increased central venous pressure, and thus is also a cause of decreased renal blood flow and further renal hypoxia (37). Renal congestion in this study is consistent with an increased renal resistive index in dogs infected with B. canis, which was observed in a previous study on abdominal ultrasonographic findings in canine babesiosis (15). Shimada et al. (37) also showed in a rat model that decreased renal blood flow in renal congestion is associated with increased renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure leading to compression of renal tubules and reduction of glomerular filtration rate. Thus, it seems probable that cardiac pathologies in canine babesiosis may cause renal congestion, and in this way may contribute to the development of oliguria and renal azotaemia in affected dogs. Moreover, ascites and abdominal compartment syndrome are also associated with decreased renal blood flow (31). In this study, half of the dogs had ascites, and abdominal compartment syndrome was described in a dog with babesiosis and azotaemia in a previous work (23). Thus, it cannot be excluded that the ascites observed in this study also contributed to decreased renal blood flow caused by increased abdominal pressure.

Liver changes were mainly associated with congestion and lipid accumulation. Chronic congestion leading to nutmeg liver was not associated with babesiosis. The congestion of the liver and the resulting consequences (hypoxic injury leading to atrophy, necrosis and fibrosis) observed in three dogs might nevertheless have resulted from cardiac disorders. Hypoxia of the liver in canine babesiosis may also be exacerbated by anaemia (8). Habela et al. (18) observed similar changes in sheep infected with B. ovis, and described them as centrilobular necrotic hepatitis. The lipid degeneration manifested as a common liver pathology and observed in this study might result from nutritional factors (fatty food) before the dogs contracted babesiosis. Yet, it cannot be excluded that hypoxia caused by congestion of the liver and anaemia might also have contributed to the degenerative changes in this organ (8). The jaundice observed in two dogs in this study might have resulted from both liver injury and haemolytic anaemia. However, according to Jacobson and Clark (22), icterus in dogs with babesiosis is not associated with haemolytic anaemia, but results from hypoxic or anoxic damage of the liver and impaired transfer of conjugated bilirubin between hepatocytes and bile canaliculi. In this study, only total bilirubin was determined, so it was not possible to recognise the cause of hyperbilirubinaemia. In previous studies on canine babesiosis, this pathology was associated with the complicated form of the disease (21, 30). In dogs infected with B. rossi, icterus was also associated with pancreatitis (21). However, in this study there was no evidence of pancreatitis in any of the dogs. In three out of six animals, congestion of the pancreas was observed. In humans, congestive changes of the pancreas may result from liver cirrhosis or portal hypertension (24). Among other causes, increased vascular resistance in portal circulation may result from splenomegaly, in which case the cause is prehepatic, or from right heart failure with a post-hepatic cause. Moreover, portal hypertension may be exacerbated by increased abdominal pressure and may be associated with ascites (7). It seems possible that in canine babesiosis, both splenomegaly and cardiac pathologies may contribute to the development of portal hypertension. Abdominal compartment syndrome may also bring about an intensification of this pathology which leads to congestion of the pancreas. A common and rapid post-mortem change, the autolysis of the pancreas probably developed after the deaths of the two dogs in which it was observed (8).

The presence of petechiae in the mucosal membranes of the stomach and small intestine might result from thrombocytopenia, which was observed in previous studies on canine babesiosis and according to some authors may result from DIC (35). However, no thrombi were observed in histological examinations of the stomach and intestinal wall, nor were haemorrhages observed in the studied dogs, and these results are consistent with the results of a previous study on thrombocytopenia in canine babesiosis (17). Another explanation for this observation may be local endothelial dysfunction or injury caused by sequestration of infected red blood cells in capillary vessels, blocked microcirculation and local increased concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines (2). Congestion of mesenteric lymph nodes was observed in three dogs in this study. Similar changes were also detected in feline babesiosis caused by B. lengau and bovine babesiosis caused by B. bovis (5, 34). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is local activation of Hageman factor (coagulation factor XII), which has been shown to be able to cause lymph node congestion in rats in an experimental study (9). Thus, this result may confirm the possible development of coagulation disorders in canine babesiosis.

Splenomegaly is one of the most common pathologies observed in canine babesiosis, and this pathology is considered to be associated with haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia (15, 30).

Cerebral babesiosis has been previously described in affected animals including dogs, cats, and cattle (1, 5, 11, 21, 34). In this study, gross examination revealed cerebral changes (congestion of the brain and/or meninges) in five dogs, and histological examination revealed changes (congestion, extravasations, oedema, neuronal degeneration and necrosis) in the brains of all six dogs. However, only one dog (No. IV) had neurological signs, and histological examination revealed Babesia-infected red blood cells sequestrated in the brain capillary vessels only in this dog. However, we cannot exclude that the vocalisation by dog No. III could have been a neurological sign.

A previous study on human cerebral malaria (a protozoan disease similar to babesiosis) showed an association between sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells in the brain capillary vessels and microvascular congestion and coma in patients with malaria (26). Thus, it seems probable that sequestration of parasitised red blood cells in the brain capillary vessels may be an explanation for the observed ante-mortem neurological signs in dog No. IV. Contradictingly, in one previous case report on cerebral babesiosis, parasites were not detected in the brain microvessels of the affected dog although, the genetic material of the parasite was isolated from the dog’s brain (1). On the other hand, in some Babesia-infected dogs with marked sequestration of red blood cells in the brain microvessels, no neurological signs were observed before death (21). Thus, it seems that it is not only sequestration of parasitised red blood cells and obstructions in cerebral microcirculation that have an influence on the development of neurological signs in affected dogs. In most dogs with cerebral babesiosis and a cat infected with B. lengau, congestion of the grey matter was observed, and histological examination revealed endothelial injuries and haemorrhages (5, 11, 21, 26). Inflammatory infiltrations were observed only in association with endothelial injury and protozoan parasites in microvessels in dogs infected with B. rossi (21). Similarly, in this study neutrophil infiltrations were observed only in the dog with parasitised red blood cells in the brain microvasculature. In opposition to this study’s findings, in a South African form of canine babesiosis neuronal changes were minimal, and according to Jacobson (21) brain lesions did not result from hypoxia. This study showed degenerative and necrotic neuronal changes typical for hypoxic injury in all six dogs, but these changes in canine babesiosis, probably resulting from decreased capillary blood flow, did not manifest clinically as the cerebral form of the disease. Thus, it seems probable that the presence of the parasite and its sequestration in the brain capillary vessels, rather than blood stasis in the cerebral microvasculature and hypoxia, is key to the development of cerebral babesiosis. This is consistent with the pathogenesis of human cerebral malaria (13). In this study, the presence of the parasite inside red blood cells in capillary vessels despite antiparasitic treatment probably resulted from the parasite being drug resistant (39).

The main pathological changes in the infected dogs were associated with disorders in blood circulation. The oedemata and congestion of various organs observed in necropsies of these dogs suggested disorders in circulation as the most probable cause of death. It seems probable that cardiac pathology, coagulation disorders, overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and septic shock described previously in canine babesiosis might contribute to the development of disorders in circulation. It cannot be excluded that in the three dogs with pneumonitis, pro-inflammatory cytokines were coagents in the development of pulmonary insufficiency, which could also have led to death. In the dog with sequestrated parasitised red blood cells in the microvasculature of the brain, the fatal outcome may have been through cerebral babesiosis. However, in this dog congestion of various organs and pulmonary oedema also suggests disorders in the blood circulation as a possible cause of death.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interests Statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

Financial Disclosure Statement: The source of funding of research and the article was Institute of Veterinary Medicine research budget and the authors’ own resources.

Animal Rights Statement: None required.

References

- 1.Adaszek L., Górna M., Klimiuk P., Kalinowski M., Winiarczyk S.. A presumptive case of cerebral babesiosis in a dog in Poland caused by a virulent Babesia canis strain. Tierärztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2012;40:367–371. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1623660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barić Rafaj R., Kuleš J., Selanec J., Vrkić N., Zovko V., Zupančič M., Trampuš Bakija A., Matijatko V., Crnogaj M., Mrljak V.. Markers of Coagulation Activation, Endothelial Stimulation, and Inflammation in Dogs with Babesiosis. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:1172–1178. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartnicki M., Łyp P., Dębiak P., Staniec M., Winiarczyk S., Buczek K., Adaszek Ł.. Cardiac disorders in dogs infected with Babesia canis. Pol J Vet Sci. 2017;20:573–581. doi: 10.1515/pjvs-2017-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonfanti U., Zini E., Minetti E., Zatelli A.. Free light-chain proteinuria and normal renal histopathology and function in 11 dogs exposed to Leishmania infantum Ehrlichia canis, and Babesia canis. J Vet Intern Med. 2004;18:618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2004.tb02596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosman A.M., Oosthuizen M.C., Venter E.H., Steyl J.C.A., Gous T.A., Penzhorn B.L.. Babesia lengau associated with cerebral and haemolytic babesiosis in two domestic cats. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:128. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouyssou S., Specchi S., Desquilbet L., Pey P.. Radiographic appearance of presumed noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and correlation with the underlying cause in dogs and cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2017;58:259–265. doi: 10.1111/vru.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buob S., Johnston A.N., Webster C.R.L.. Portal Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:169–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullen J.M. McGavin M.D., Zachary J.F. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis; 2007. Liver, Biliary System, and Exocrine Pancreas; pp. 393–461. edited by. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damas J., Remacle-Volon G., Adam A.. Mechanism of the congestion of lymph nodes induced by ellagic acid in rats. Agents Actions. 1987;22:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02009047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damman K., Navis G., Smilde T.D.J., Voors A.A., van der Bij W., van Veldhuisen D.J., Hillege H.L.. Decreased cardiac output, venous congestion and the association with renal impairment in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daste T., Lucas M.N., Aumann M.. Cerebral babesiosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome in a dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2013;23:615–623. doi: 10.1111/vec.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dvir E., Lobetti R.G., Jacobson L.S., Pearson J., Becker P.J.. Electrocardiographic changes and cardiac pathology in canine babesiosis. J Vet Cardiol. 2004;6:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S1760-2734(06)70060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dvorin J.D.. Getting Your Head around Cerebral Malaria. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:586–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fanelli V., Vlachou A., Ghannadian S., Simonetti U., Slutsky A.S., Zhang H.. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: new definition, current and future therapeutic options. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:326–334. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraga E., Barreiro J.D., Goicoa A., Espino L., Fraga G., Barreiro A.. Abdominal ultrasonographic findings in dogs naturally infected with babesiosis. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2011;52:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goddard A., Leisewitz A.L., Kjelgaard-Hansen M., Kristensen A.T., Schoeman J.P.. Excessive Pro-Inflammatory Serum Cytokine Concentrations in Virulent Canine Babesiosis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goddard A., Leisewitz A.L., Kristensen A.T., Schoeman J.P.. Platelet indices in dogs with Babesia rossi infection. Vet Clin Pathol. 2015;44:493–497. doi: 10.1111/vcp.12306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habela M.A., Reina D., Navarrete I., Redondo E., Hernández S.. Histopathological changes in sheep experimentally infected with Babesia ovis. Vet Parasitol. 1991;38:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(91)90002-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irwin P.J.. Canine babesiosis: from molecular taxonomy to control. Parasit. Vectors. 2009;2(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-S1-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwin P.J., Hutchinson G.W.. Clinical and pathological findings of Babesia infection in dogs. Aust Vet J. 1991;68:204–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1991.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson L.S.. The South African form of severe and complicated canine babesiosis: Clinical advances 1994–2004. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson L.S., Clark I.A.. The pathophysiology of canine babesiosis: new approaches to an old puzzle. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1994;65:134–145. 10520/AJA00382809_1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joubert K.E., Oglesby P.A., Downie J., Serfontein T.. Abdominal compartment syndrome in a dog with babesiosis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2007;17:184–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2006.00219.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda T., Hirooka M., Koizumi M., Ochi H., Hisano Y., Bando K., Matsuura B., Kumagi T., Hiasa Y.. Pancreatic congestion in liver cirrhosis correlates with impaired insulin secretion. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:683–693. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leisewitz A., Goddard A., De Gier J., Van Engelshoven J., Clift S., Thompson P., Schoeman J.P.. Disease severity and blood cytokine concentrations in dogs with natural Babesia rossi infection. Parasite Immunol. 2019;41:e12630. doi: 10.1111/pim.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leisewitz A., Turner G., Clift S., Pardini A.. The neuropathology of canine cerebral babesiosis compared to human cerebral malaria. Malaria J. 2014;13(Suppl 1):P55. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-S1-P55. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lobetti R.G., Reyers F., Nesbit J.W.. The comparative role of haemoglobinaemia and hypoxia in the development of canine babesial nephropathy. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1996;67:188–198. 10520/AJA00382809_1681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López A. McGavin M.D., Zachary J.F. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis; 2007. Respiratory System; pp. 463–558. edited by. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Máthé A., Dobos-Kovács M., Vörös K.. Histological and ultrastructural studies of renal lesions in Babesia canis infected dogs treated with imidocarb. Acta Vet Hung. 2007;55:511–523. doi: 10.1556/AVet.55.2007.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Máthé A., Vörös K., Németh T., Biksi I., Hetyey C., Manczur F.. Clinicopathological changes and effect of imidocarb therapy in dogs experimentally infected with Babesia canis. Acta Vet Hung. 2006;54:19–33. doi: 10.1556/AVet.54.2006.1.3. Tekes L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohmand H., Goldfarb S.. Renal Dysfunction Associated with Intra-abdominal Hypertension and the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:615–621. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Möhr A.J., Lobetti R.G., van der Lugt J.J.. Acute pancreatitis: a newly recognised potential complication of canine babesiosis. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000;71:232–239. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v71i4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman S.J., Confer A.W., Panciera R.J. McGavin M.D., Zachary J.F. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis; 2007. Urinary System; pp. 613–691. edited by. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodrigues A., Rech R.R., de Barros R.R., Fighera R.A., de Barros C.S.L.. Cerebral babesiosis in cattle: 20 cases. Cienc Rural. 2005;35:121–125. doi: 10.1590/S0103-84782005000100019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz de Gopegui R., Peñalba B., Goicoa A., Espada Y., Fidalgo L.E., Espino L.. Clinico-pathological findings and coagulation disorders in 45 cases of canine babesiosis in Spain. Vet J. 2007;174:129–132. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rymaszewska A., Adamska M.. Molecular evidence of vector-borne pathogens coinfecting dogs from Poland. Acta Vet Hung. 2011;59:215–223. doi: 10.1556/AVet.2011.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimada S., Hirose T., Takahashi C., Sato E., Kinugasa S., Ohsaki Y., Kisu K., Sato S., Ito S., Mori T.. Pathophysiological and molecular mechanisms involved in renal congestion in a novel rat model. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16808. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35162-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun L.Y., Wijeysundera D.N., Tait G.A., Beattie W.S.. Association of Intraoperative Hypotension with Acute Kidney Injury after Elective Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:515–523. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vial H.J., Gorenflot A.. Chemotherapy against babesiosis. Vet Parasitol. 2006;138:147–160. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walls J.J., Caturegli P., Bakken J.S., Asanovich K.M., Dumler J.S.. Improved sensitivity of PCR for diagnosis of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis using epank1 genes of Ehrlichia phagocytophila-group ehrlichiae. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:354–356. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.1.354-356.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh M., Devereaux P.J., Garg A.X., Kurz A., Turan A., Rodseth R.N., Cywinski J., Thabane L., Sessler D.I.. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zygner W., Gójska-Zygner O., Bąska P., Długosz E.. Increased concentration of serum TNF alpha and its correlations with arterial blood pressure and indices of renal damage in dogs infected with Babesia canis. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:1499–1503. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3792-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zygner W., Gójska-Zygner O., Bąska P., Długosz E.. Low T3 syndrome in canine babesiosis associated with increased serum IL-6 concentration and azotaemia. Vet Parasitol. 2015;211:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zygner W., Gójska-Zygner O., Wędrychowicz H.. Strong monovalent electrolyte imbalances in serum of dogs infected with Babesia canis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]