Abstract

Objective

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a common glomerular disease caused by a variety of causes and is the second most common kidney disease. Guizhi is the key drug of Wulingsan in the treatment of NS. However, the action mechanism remains unclear. In this study, network pharmacology and molecular docking were used to explore the underlying molecular mechanism of Guizhi in treating NS.

Methods

The active components and targets of Guizhi were screened by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP), Hitpick, SEA, and Swiss Target Prediction database. The targets related to NS were obtained from the DisGeNET, GeneCards, and OMIM database, and the intersected targets were obtained by Venny2.1.0. Then, active component-target network was constructed using Cytoscape software. And the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was drawn through the String database and Cytoscape software. Next, Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed by DAVID database. And overall network was constructed through Cytoscape. Finally, molecular docking was conducted using Autodock Vina.

Results

According to the screening criteria, a total of 8 active compounds and 317 potential targets of Guizhi were chosen. Through the online database, 2125 NS-related targets were identified, and 93 overlapping targets were obtained. In active component-target network, beta-sitosterol, sitosterol, cinnamaldehyde, and peroxyergosterol were the important active components. In PPI network, VEGFA, MAPK3, SRC, PTGS2, and MAPK8 were the core targets. GO and KEGG analyses showed that the main pathways of Guizhi in treating NS involved VEGF, Toll-like receptor, and MAPK signaling pathway. In molecular docking, the active compounds of Guizhi had good affinity with the core targets.

Conclusions

In this study, we preliminarily predicted the main active components, targets, and signaling pathways of Guizhi to treat NS, which could provide new ideas for further research on the protective mechanism and clinical application of Guizhi against NS.

1. Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a clinical syndrome defined as massive proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and edema [1]. According to the epidemiological survey, the incidence of NS is about 2-10/100000, and it mostly occurs in male children [2]. NS greatly affects people's health and life quality with poor prognosis and high recurrence rate [3]. At present, the etiopathogenesis of NS is incompletely understood, but relevant reports have shown that it is related to inflammatory response and immune suppression.

According to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), NS belongs to “edema,” and the pathogenesis of NS lies in the dysfunction of the lung, spleen, and kidney [4]. TCM has been used to treat kidney disease and its complications, for that it can protect the kidney from dysfunction and delay the renal failure [5]. Guizhi is a Chinese herbal medicine that is commonly used to treat edema [6]. Currently, there are many reports on the pharmacological effects of Guizhi, but it is not comprehensive and systematic in the mechanism studies of Guizhi to treat NS.

Network pharmacology integrates diseases and drugs into the biomolecular network, to predict the active components and the action mechanism [7]. As a new idea approach of TCM research, network pharmacology has been widely applied in the research of the complex network relationship between TCM and disease [8–10].

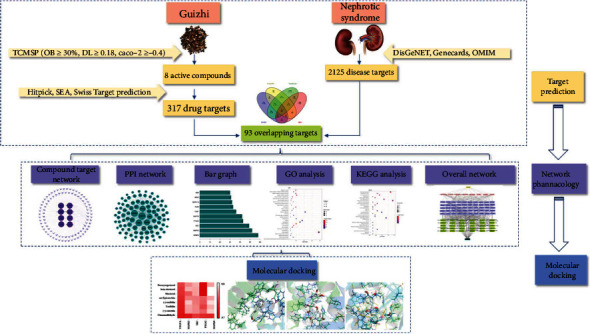

In the present study, network pharmacology and molecular docking were used to explore the potential action mechanism of Guizhi to treat NS. It is hoped to provide theoretical foundation and scientific evidence for the clinical treatment of NS, and the workflow of our study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow diagram based on a cohesive integration strategy of network pharmacology and molecular docking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Screening of Active Compounds

The active compounds of Guizhi were searched by TCMSP database (https://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php). The PubChem ID, molecular formula, and canonical SMILES of each component were collected through PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). And the main active components were obtained by the screening criteria of oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 30%, drug − like (DL) ≥ 0.18, and cell permeability (Caco − 2) ≥ −0.4.

2.2. Predicting Drug Targets

The targets of active compounds of Guizhi were predicted by Hitpick (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/hitpick/cgi-bin/index.cgi?content=help.html), SEA (http://sea.bkslab.org/), and Swiss Target Prediction database (http://swisstargetprediction.ch/). The duplicates were deleted after the predicted targets of the 3 databases were merged.

2.3. Screening of Disease Targets

Using “Nephrotic syndrome” and “Adriamycin Nephropathy” as the keywords, the NS-related targets were collected from DisGeNET, GeneCards, and OMIM databases. After the removal of repeated targets, Venny2.1.0 was used to screening the intersection of drug targets and disease targets to obtain the potential targets of Guizhi in the treatment of NS.

2.4. Construction of Active Component-Target Network

The potential targets were imported into Cytoscape to construct the components-target-network.

2.5. Construction of PPI Network

The PPI network was constructed using the String database and Cytoscape software. In this process, the potential targets were input into the String database to obtain the protein interactions, and the interactions were visualized by Cytoscape software in a form of PPI network.

2.6. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

DAVID database was used for GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. The GO and KEGG enriched terms were collected for biological process (BP), cell component (CC), and molecular function (MF), at a cutoff of P < 0.05, and the corresponding bubble diagram were drawn.

2.7. Construction of Overall Network

The active compounds of Guizhi, the top 30 KEGG signaling pathways, and the corresponding targets were used to construct the drug-compound-target-pathway-disease network through Cytoscape.

2.8. Molecular Docking

The top 5 important targets with high network connection degrees were selected for molecular docking analysis using Autodock Vina. The smaller the binding energy (affinity) was, the more stable the interaction between the target protein and the active ingredient was.

3. Results

3.1. Active Compounds of Guizhi

A total of 220 compounds were collected from the TCMSP database, with OB ≥ 30%, DL ≥ 0.18, and Caco − 2 ≥ −0.4, and 7 active compounds were identified. Cinnamaldehyde, OB = 31.99%, DL = 0.02, and Caco − 2 = 1.35, was not included in the results of TCMSP screening. However, our previous study found that cinnamaldehyde might be an important active compound of Guizhi [11]. Therefore, cinnamaldehyde was selected as a candidate active component in this study, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The main active compounds of Guizhi.

| Mol ID | Molecule name | OB (%) | DL | Caco-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOL000073 | Ent-Epicatechin | 48.96 | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| MOL000358 | Beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 1.32 |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | 1.32 |

| MOL000492 | (+)-catechin | 54.83 | 0.24 | -0.03 |

| MOL000991 | Cinnamaldehyde | 31.99 | 0.02 | 1.35 |

| MOL001736 | (-)-taxifolin | 60.51 | 0.27 | -0.24 |

| MOL004576 | Taxifolin | 57.84 | 0.27 | -0.23 |

| MOL011169 | Peroxyergosterol | 44.39 | 0.82 | 0.86 |

3.2. Drug Target Prediction

8 active components of Guizhi were input into Hitpick, SEA, and Swiss Target Prediction databases. After combining the predicted targets from the 3 databases, the duplicates were deleted, and a total of 317 potential targets were selected.

3.3. Disease Target Prediction

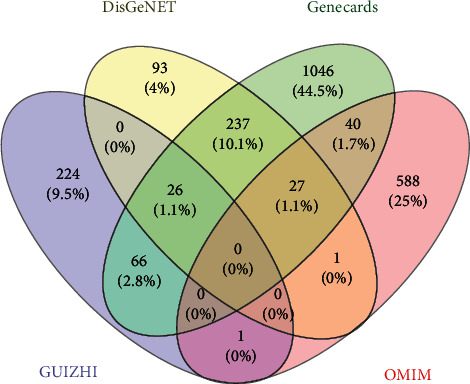

The keywords “Nephrotic syndrome” and “Adriamycin Nephropathy” were searched in DisGeNET, GeneCards, and OMIM databases. A total of 2125 targets were identified. Venny 2.1.0 was used to intersect disease targets with drug targets. Finally, 93 potential targets (Figure 2) were selected and further confirmed by UniProt database, as shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

The Venny plot of 93 potential targets.

Table 2.

93 potential targets and UniProt information.

| No. | Gene names | Protein names | UniProt ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABCB1 | ATP-dependent translocase ABCB1 | P08183 |

| 2 | ABCC2 | ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 2 | Q92887 |

| 3 | ABCG2 | Broad substrate specificity ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 | Q9UNQ0 |

| 4 | ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme | P12821 |

| 5 | ACHE | Acetylcholinesterase | P22303 |

| 6 | ACP1 | Low molecular weight phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase | P24666 |

| 7 | AKR1B1 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B1 | P15121 |

| 8 | AKR1B10 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 | O60218 |

| 9 | ALK | ALK tyrosine kinase receptor | Q9UM73 |

| 10 | APP | Amyloid-beta precursor protein | P05067 |

| 11 | AR | Androgen receptor | P10275 |

| 12 | AVPR1A | Vasopressin V1a receptor | P37288 |

| 13 | CASR | Extracellular calcium-sensing receptor | P41180 |

| 14 | CCR1 | C-C chemokine receptor type 1 | P32246 |

| 15 | CD4 | T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4 | P01730 |

| 16 | CDK4 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 | P11802 |

| 17 | CTSB | Cathepsin B | P07858 |

| 18 | CTSL | Procathepsin L | P07711 |

| 19 | CYP11B2 | Cytochrome P450 11B2 | P19099 |

| 20 | CYP19A1 | Cytochrome P450 19A1 | P11511 |

| 21 | CYP1A1 | Cytochrome P450 1A1 | P04798 |

| 22 | CYP1B1 | Cytochrome P450 1B1 | Q16678 |

| 23 | CYP2A6 | Cytochrome P450 2A6 | P11509 |

| 24 | CYP2C19 | Cytochrome P450 2C19 | P33261 |

| 25 | CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 | P08684 |

| 26 | DNMT1 | DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1 | P26358 |

| 27 | DUSP1 | Dual specificity protein phosphatase 1 | P28562 |

| 28 | ELANE | Neutrophil elastase | P08246 |

| 29 | ELAVL1 | ELAV-like protein 1 | Q15717 |

| 30 | ESR1 | Estrogen receptor | P03372 |

| 31 | ESR2 | Estrogen receptor beta | Q92731 |

| 32 | F10 | Coagulation factor X | P00742 |

| 33 | F2 | Coagulation factor II | P00734 |

| 34 | F2R | Coagulation factor II receptor | P25116 |

| 35 | F3 | Coagulation factor III | P13726 |

| 36 | FABP1 | Fatty acid-binding protein 1 | P07148 |

| 37 | G6PD | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | P11413 |

| 38 | GC | Group-specific component | P02774 |

| 39 | GLO1 | Glyoxalase I | Q04760 |

| 40 | HDAC2 | Histone deacetylase 2 | Q92769 |

| 41 | HIF1A | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha | Q16665 |

| 42 | HMGCR | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase | P04035 |

| 43 | HSD11B1 | Corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 1 | P28845 |

| 44 | HSD11B2 | Corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 2 | P80365 |

| 45 | HTR2B | 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B | P41595 |

| 46 | ICAM1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | P05362 |

| 47 | IGF1R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor | P08069 |

| 48 | ITGAL | Integrin alpha-L | P20701 |

| 49 | ITGB2 | Integrin beta-2 | P05107 |

| 50 | KAT2B | Histone acetyltransferase KAT2B | Q92831 |

| 51 | KCNH2 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 | Q12809 |

| 52 | KDR | Kinase insert domain receptor | P35968 |

| 53 | MAP2K1 | Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 | Q02750 |

| 54 | MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | Q16539 |

| 55 | MAPK3 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 | P27361 |

| 56 | MAPK8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | P45983 |

| 57 | MAPT | Microtubule-associated protein tau | P10636 |

| 58 | MCL1 | Induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein Mcl-1 | Q07820 |

| 59 | MDM2 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Mdm2 | Q00987 |

| 60 | MET | Hepatocyte growth factor receptor | P08581 |

| 61 | MMP12 | Matrix metalloproteinase-12 | P39900 |

| 62 | MPO | Myeloperoxidase | P05164 |

| 63 | NFE2L2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 | Q16236 |

| 64 | NOS1 | Peptidyl-cysteine S-nitrosylase NOS1 | P29475 |

| 65 | NOS2 | Peptidyl-cysteine S-nitrosylase NOS2 | P35228 |

| 66 | NOS3 | NOS type III | P29474 |

| 67 | NR1I2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 2 | O75469 |

| 68 | NR3C1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 | P04150 |

| 69 | PARP1 | Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 | P09874 |

| 70 | PLA2G1B | Phosphatidylcholine 2-acylhydrolase 1B | P04054 |

| 71 | PLA2G7 | Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase | Q13093 |

| 72 | PPARA | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha | Q07869 |

| 73 | PRKCB | Protein kinase C beta type | P05771 |

| 74 | PRKCD | Protein kinase C delta type | Q05655 |

| 75 | PSEN1 | Presenilin-1 | P49768 |

| 76 | PTGS2 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | P35354 |

| 77 | PTK2B | Protein-tyrosine kinase 2-beta | Q14289 |

| 78 | PTPN11 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 11 | Q06124 |

| 79 | PTPN2 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 2 | P17706 |

| 80 | PTPRC | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase C | P08575 |

| 81 | RELA | Transcription factor p65 | Q04206 |

| 82 | SLC6A2 | Sodium-dependent noradrenaline transporter | P23975 |

| 83 | SNCA | Alpha-synuclein | P37840 |

| 84 | SRC | Protooncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src | P12931 |

| 85 | TGM2 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | P21980 |

| 86 | TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 | O00206 |

| 87 | TOP1 | DNA topoisomerase 1 | P11387 |

| 88 | TRPA1 | Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily A member 1 | O75762 |

| 89 | TYMP | Thymidine phosphorylase | P19971 |

| 90 | TYMS | Thymidylate synthase | P04818 |

| 91 | VDR | Vitamin D3 receptor | P11473 |

| 92 | VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | P15692 |

| 93 | XDH | Xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase | P47989 |

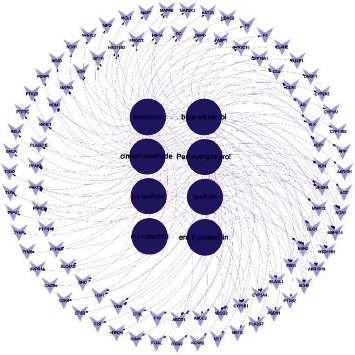

3.4. Analysis of Active Component-Target Network

The 93 potential targets were analyzed by Cytoscape to construct the active component-target interaction network (Figure 3). The result included 101 nodes and 169 edges. And different components indicated different targets. Among them, the degree values of beta-sitosterol, sitosterol, cinnamaldehyde, and peroxyergosterol were 37, 37, 36, and 29, respectively (Table 3), which might be the important active components in the network.

Figure 3.

The active component-target network. The network formed with 101 nodes and 169 edges. The dark purple circles represented active compounds; the light purple inverted triangles represented intersecting targets. The edges represented the connection between active component and targets.

Table 3.

Degree value of 8 main active components of Guizhi.

| Mol ID | Molecule name | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| MOL000358 | Beta-sitosterol | 37 |

| MOL000359 | Sitosterol | 37 |

| MOL000991 | Cinnamaldehyde | 36 |

| MOL011169 | Peroxyergosterol | 29 |

| MOL001736 | (-)-taxifolin | 12 |

| MOL004576 | Taxifolin | 12 |

| MOL000492 | (+)-catechin | 3 |

| MOL000073 | Ent-Epicatechin | 3 |

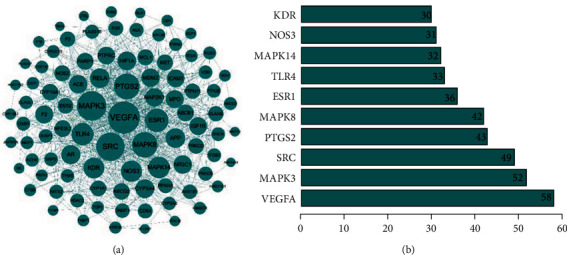

3.5. PPI Network Analysis

A total of 93 nodes and 1478 edges were involved in the PPI network (Figure 4(a)). The bar chart of the top 10 target proteins was drawn based on the degree value (Figure 4(b)). Among them, VEGFA, MAPK3, SRC, PTGS2, and MAPK8 degree values were 58, 52, 49, 43, and 42, respectively, which were the core nodes of the network, suggesting that Guizhi might play a significance role in the protection of NS through them.

Figure 4.

The PPI network diagram (a) and the bar graph of the top 10 intersecting targets with degree values in PPI network (b). In PPI network, nodes represented intersecting targets, and edges represented interactions between targets, and the size reflected the value of degree. In the bar graph, the top 10 targets were selected according to the degree value.

3.6. GO and KEGG Analysis

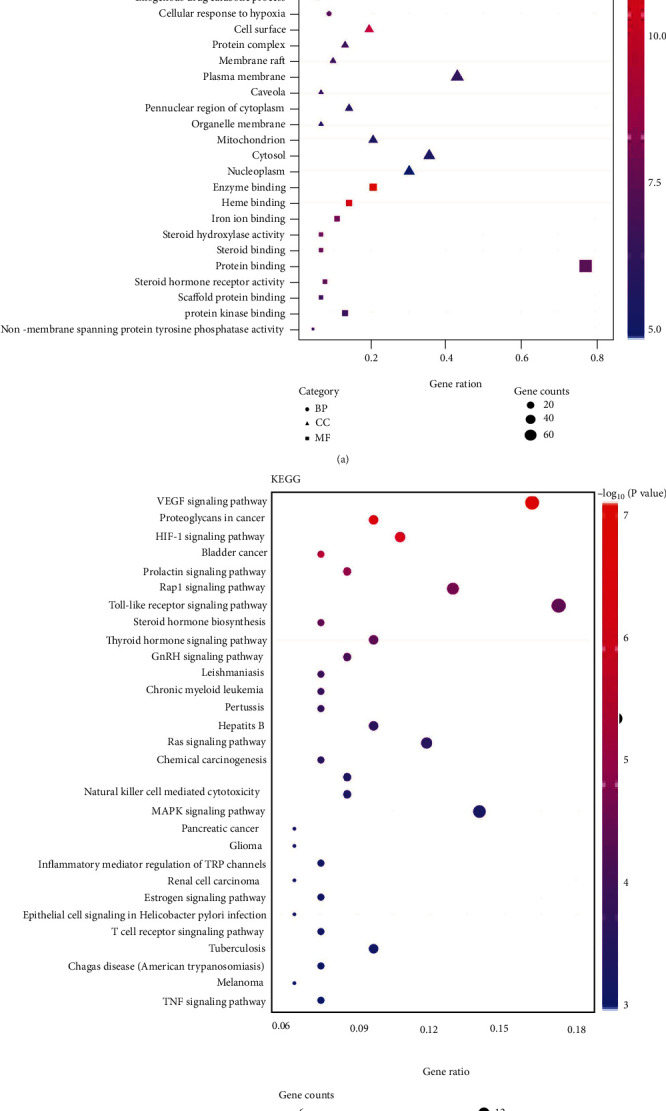

93 potential targets were analyzed using DAVID 6.8, and the GO terms (BP, CC, and MF) and KEGG signaling pathway were selected. Targets in the BP were closely related to response to organic substance and positive regulation of molecular function and response to hormone stimulus. In the CC, Guizhi had great effect on cell surface, cell fraction, and plasma membrane part. At the MF level, drug components of Guizhi were mainly related to steroid binding, heme binding, and tetrapyrrole binding (Figure 5(a)). A total of 71 KEGG pathways were mainly involved, including VEGF, Toll-like receptor, and MAPK signaling pathway (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Go (a) and KEGG enrichment analysis (b). The top 10 items of BP, CC, and MF and the top 30 KEGG signal pathways were selected according to the P value to draw the GO and KEGG bubble diagram. The color of the bubbles changes from purple to red indicating that the P value decreases from large to small. Gene ratio is the number of targets that located in the pathway. The higher the gene ratio is, the more targets were enriched.

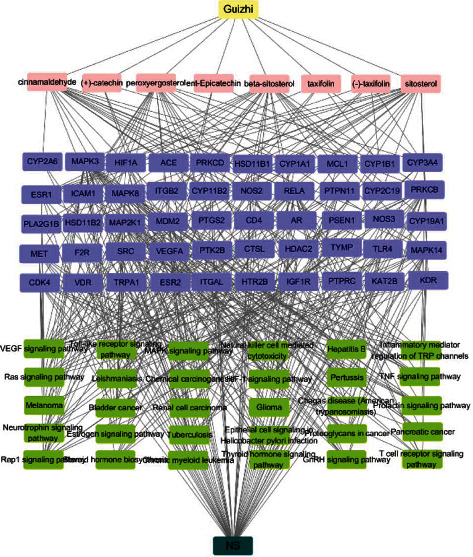

3.7. Overall Network Analysis

To further investigate the molecular mechanism of Guizhi against NS, overall network was constructed based on the top 30 significant KEGG signaling pathways and their corresponding targets (Figure 6). 90 nodes (1 drug, 8 compound, 50 targets, 30 pathways, and 1disease) were contained in this network. Among these targets, MAPK3, MAPK8, MAPK14, VEGFA, and TLR4 were identified as high-degree targets, and in these pathways, Toll-like receptor, VEGF, and MAPK signaling pathways were the most important signaling pathways. Therefore, the network analysis suggests that the action mechanism of Guizhi to treat NS might be related to Toll-like receptor, VEGF, and MAPK signaling pathways.

Figure 6.

The overall network of the top 30 significant KEGG signaling pathways with their corresponding targets. The yellow represents Guizhi, pink represents active compounds, purple represents core targets, green represents signaling pathways, and dark green represents NS.

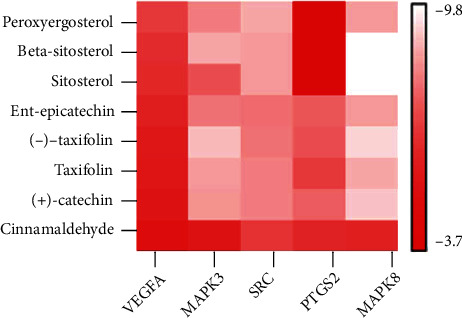

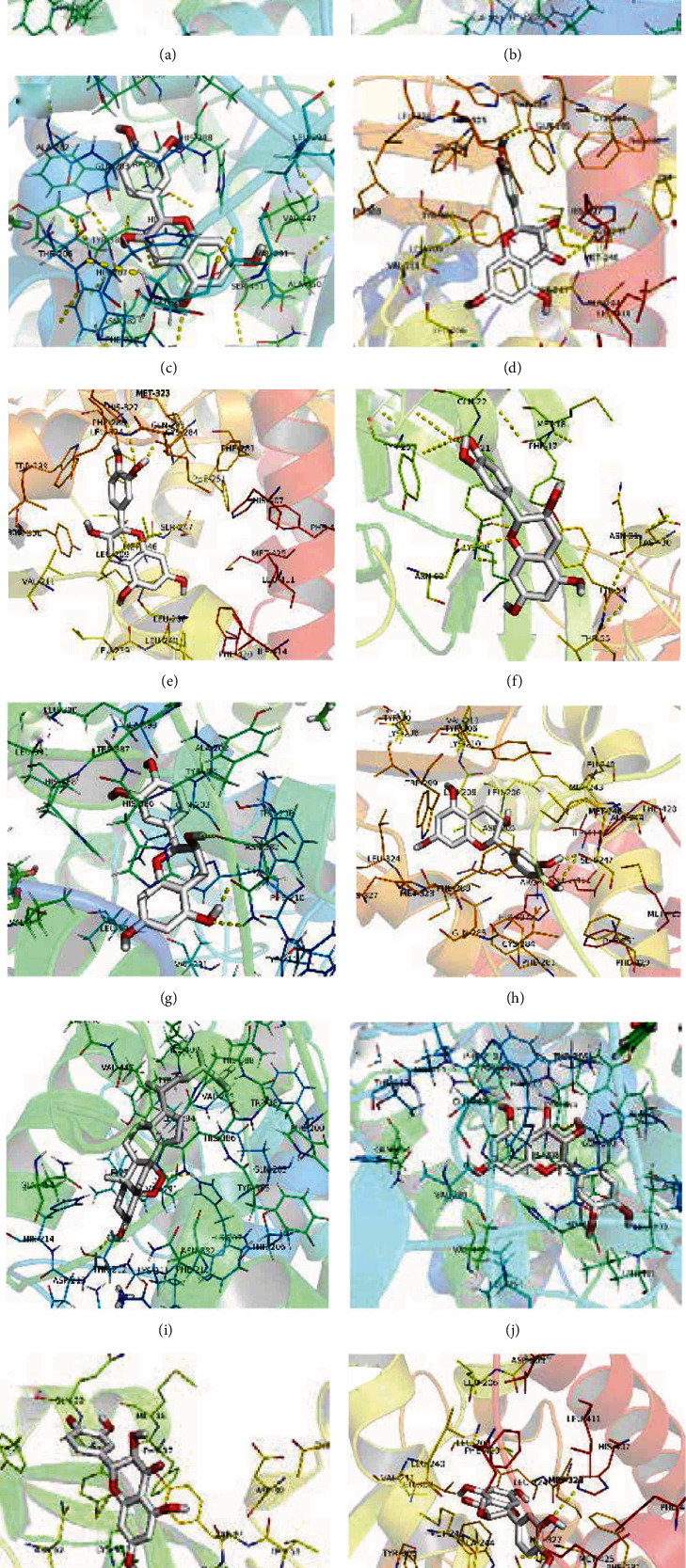

3.8. Molecular Docking

The top 5 targets, including VEGFA, MAPK3, SRC, PTGS2, and MAPK8 (Table 4) in the PPI network were analyzed for the molecular docking with the active compounds of Guizhi. It was found that the top 5 targets had good binding affinity with the active components of Guizhi (Table 5; Figure 7). And the binding site of compounds-targets are shown in Figure 8.

Table 4.

The top 5 targets in PPI network.

| No. | Target name | PDB ID | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VEGFA | 6BFT | 58 |

| 2 | MAPK3 | 2ZOQ | 52 |

| 3 | SRC | 6HTY | 49 |

| 4 | PTGS2 | 5IKV | 43 |

| 5 | MAPK8 | 4L7F | 42 |

Table 5.

Molecular docking results of targets and active components.

| Target name | PDB ID | Molecule name | Affinity (kcal/Mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | 6BFT | Peroxyergosterol | -6.8 |

| Beta-sitosterol | -6.4 | ||

| Sitosterol | -6.3 | ||

| Ent-Epicatechin | -5.9 | ||

| (-)-taxifolin | -5.7 | ||

| Taxifolin | -5.6 | ||

| (+)-catechin | -5.4 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | -4.9 | ||

|

| |||

| MAPK3 | 2ZOQ | (-)-taxifolin | -9.0 |

| Beta-sitosterol | -8.7 | ||

| Taxifolin | -8.5 | ||

| (+)-catechin | -8.4 | ||

| Peroxyergosterol | -8.1 | ||

| Ent-Epicatechin | -7.9 | ||

| Sitosterol | -7.3 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | -5.4 | ||

|

| |||

| SRC | 6HTY | Peroxyergosterol | -8.7 |

| Beta-sitosterol | -8.5 | ||

| Sitosterol | -8.4 | ||

| (+)-catechin | -8.1 | ||

| Taxifolin | -8.1 | ||

| (-)-taxifolin | -7.9 | ||

| Ent-Epicatechin | -7.8 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | -6.6 | ||

|

| |||

| PTGS2 | 5IKV | (+)-catechin | -7.6 |

| Ent-Epicatechin | -7.5 | ||

| (-)-taxifolin | -7.3 | ||

| Taxifolin | -6.8 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | -6.1 | ||

| Peroxyergosterol | -3.8 | ||

| Beta-sitosterol | -3.7 | ||

| Sitosterol | -3.7 | ||

|

| |||

| MAPK8 | 4L7F | Beta-sitosterol | -9.8 |

| Sitosterol | -9.8 | ||

| (-)-taxifolin | -9.3 | ||

| (+)-catechin | -9.1 | ||

| Taxifolin | -8.7 | ||

| Ent-Epicatechin | -8.5 | ||

| Peroxyergosterol | -8.5 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | -6.0 | ||

Figure 7.

The binding energy of the main active components of Guizhi and core targets.

Figure 8.

The molecular docking of active compounds and core targets: (a) cinnamaldehyde-PTGS2, (b) (-)-taxifolin-PTGS2, (c) (+)-catechin-PTGS2, (d) (-)-taxifolin-VEGFA, (e) (+)-catechin-SRC, (f) (+)-catechin-VEGFA, (g) ent-Epicatechin-PTGS2, (h) ent-Epicatechin-SRC, (i) peroxyergosterol-PTGS2, (j) taxifolin-PTGS2, (k) taxifolin-VEGFA, and (l) taxifolin-SRC.

4. Discussion

NS is a common glomerular disease caused by various etiologies and is the second most common kidney disease after acute glomerulonephritis. At present, Western medicine mainly focuses on glucocorticoids, cytotoxic drugs, and immunosuppressants for NS [1], such as glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine, which can achieve certain efficacy. However, hormone therapy is prone to infection, hormone resistance [12], withdrawal, and relapse [3], which eventually lead to chronic terminal renal failure [13, 14]. Therefore, to explore the pathogenesis of NS and to find safe and effective treatment drugs are urgent problems [15].

Wulingsan is a classic prescription for NS, which has obvious advantages in improving urinary system diseases. Guizhi is an important component of Wulingsan, which has the pharmacological activities of diuresis, improving blood circulation and dilating blood vessels. Our preliminary study found that Guizhi is indeed an important drug of Wulingsan with the protective effect on rats with adriamycin-induced nephropathy [11]. However, the action mechanism remains unknown.

In order to further explore the potential mechanism of Guizhi in treating NS and provide more evidence for clinical treatment, the main active components and targets of Guizhi, as well as the possible signaling pathways of Guizhi to treat NS, were predicted through network pharmacology and molecular docking.

In the active component-target network, the degree values of beta-sitosterol, sitosterol, cinnamaldehyde, and peroxyergosterol were much higher than those of other components, which were 37, 37, 36, and 29, respectively, suggesting that they were the key active components in the treatment of NS.

Among them, beta-sitosterol and sitosterol belong to plant sterols. Studies have found that beta-sitosterol has antihyperlipemia, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects and can treat cholesterol, proteinuria, and edema [16]. Cinnamaldehyde is an organic compound of olefine aldehyde, and it is the main component of Guizhi that plays a diuretic role. Pharmacological studies have shown that cinnamaldehyde has a variety of pharmacological activity of anti-inflammatory [17], antitumor [18], hypotensive [19], lipid-lowering [20], hypoglycemic [21], and vascular endothelial protection [22], that is playing a protective role on kidney in various aspects. Our previous study also found that cinnamaldehyde had a protective effect on renal function in adriamycin nephropathy rat [11]. Peroxyergosterol is a kind of relatively rare sterol, with antioxidant [23], antibacterial [24], immunosuppressive [25], antitumor [26], and other activities and can repair damaged kidney cells through antioxidant action. In conclusion, beta-sitosterol, sitosterol, cinnamaldehyde, and peroxyergosterol might be the main pharmacodynamic basis of Guizhi against NS.

In the PPI network, VEGFA, MAPK3, SRC, PTGS2, and MAPK8 had higher degrees than others, indicating that Guizhi might achieve the protective effect on the kidney through the above targets.

VEGFA is a receptor in vascular endothelial cells that can induce endothelial cell differentiation and proliferation [27]. It is an important molecule that maintains the function of the glomerular filtration barrier and plays an important role in renal microangiogenesis. The study has shown that the upregulation of VEGF expression is closely related to the occurrence of proteinuria [28]. Its signal conduction runs through the whole life process of podocytes and glomerular vascular endothelial cells. MAPK3 and MAPK8 are both mitogen-activated protein kinases that can mediate the progress of differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis [29, 30]. SRC is a nonreceptor protein with tyrosine protein kinase activity and plays an important role in mitosis and proliferation in normal cell [31, 32]. SRC can participate in the process of cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis through the MAPK signaling pathway and plays a crucial role in the inflammation and autoimmune diseases. PTGS2 is significant in inhibiting the development of excessive fibrosis and inflammatory response. When cells are stimulated, the expression of PTGS2 is rapidly upregulated, which catalyzes arachidonic acid to produce a variety of prostaglandins and produces anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects, thus achieving the protective effect on the kidney [33]. Therefore, the targets of VEGFA, MAPK3, SRC, PTGS2, and MAPK8 might play an essential role in the protective effect of Guizhi against NS.

In KEGG and overall network analysis, the key targets were mainly involved in VEGF, Toll-like receptor, and MAPK signaling pathway, which were highly correlated with renal disease, suggesting that the action mechanism of Guizhi to treat NS might be related to VEGF, Toll-like receptor, and MAPK signaling pathways.

VEGF signaling pathway plays an irreplaceable role in the whole process of angiogenesis and is directly related to the occurrence of hypertension. When the endothelial function of patients with hypertensive is impaired, blood pressure will significantly increase, and proteinuria is aggravated. Studies have found that the inhibition of VEGF signaling pathway can lead to large amounts of proteinuria accompanied by irreversible renal impairment [34]. In recent years, the role of the innate immune Toll-like receptor (TLR) in kidney disease has attracted more and more attention [35] and is involved in the innate immune and inflammatory response [36]. Studies have shown that TLR can be expressed in a small amount in renal mesangial cells, renal tubular epithelial cells, and podocytes [37]. The increase of TLR expression can cause the pathophysiological changes such as the upregulation of inflammatory factors and cell apoptosis [38]. MAPK signaling pathway is a stress pathway of cellular functional activities, plays a vital role in acute and chronic inflammation, and participates in physiological processes such as cell growth, development, differentiation, and apoptosis [39]. Activation of MAPK signaling pathway can not only trigger renal inflammation [40] but also lead to podocyte injury [41]. Studies have shown that MAPK signaling pathway can cause proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis through oxidative stress, triggering inflammatory factors and activating inflammatory pathways [42]. Munkonda et al. found that MAPK can also promote proximal tubule fibrosis, thus mediating the development of renal disease [43].

Based on the network pharmacology results, molecular docking was performed to verify the interactions between the 8 active components of Guizhi and the key targets. The docking results showed that all the compounds had good binding activities with the targets, indicating that they may play an important role in Guizhi to treat NS.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the potential mechanism of Guizhi to treat NS was predicted based on the network pharmacology and molecular docking. The results indicated that the underlying mechanism of Guizhi in treating NS may be related to VEGF, Toll-like receptor, and MAPK signaling pathway. However, the transmission of each signal pathway is complicated, and the final mechanism needs to be further verified by subsequent experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Three-Year Action Plan of Shanghai Municipality for Further Accelerating the Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine (no. ZY (2018-2020)-CCCX-2001-01.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions

Dan He designed the study. Dan He, Qiang Li, and Jijia Sun performed the data analysis. Guangli Du, Guofeng Meng, and Shaoli Chen modified the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Krishnan R. G. Nephrotic syndrome. Paediatrics and Child Health . 2012;22(8):337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2012.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah S. S., Akhtar N., Sunbleen F., ur Rehman M. F., Ahmed T. Histopathological patterns in paediatric idiopathic steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC . 2015;27(3):633–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaltonen S., Honkanen E. Outcome of idiopathic membranous nephropathy using targeted stepwise immunosuppressive treatment strategy. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation . 2011;26(9):2871–2877. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y. X., Zhang P. Q., Zhang Q. Professor Zhang Qi's experience in treating refractory nephrotic syndrome edema with “tong”. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Nephrology . 2014;5(8):663–664. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X. L., Liu C. H., Li H. J., Tian M., Wu L. J., Cao G. H. Effect of Guizhifuling Decoction combined with hormone on primary nephrotic syndrome in children and its effect on serum inflammatory factors. Shaanxi Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2018;39(11):1609–1612. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin R. Z., Yu R. H., Gao H., Yang C. X., Fang F., Wang J. N. Clinical control study of Wuling SAN and Wuling Tang in treating nephrotic syndrome with internal stasis of water and dampness. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2012;53(7):572–573. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S., Zhang B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: theory, methodology and application. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines . 2013;11(2):110–120. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlow D. J., Buriani A., Ehrman T., Bosisio E., Eberini I., Hylands P. J. In-silico studies in Chinese herbal medicines ' research: evaluation of in- silico methodologies and phytochemical data sources, and a review of research to date. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2012;140(3):526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai W., Chen J. X., Lu P., et al. Pathway pattern-based prediction of active drug components and gene targets from H1N1 influenza's treatment with maxingshigan-yinqiaosan formula. Molecular BioSystems . 2013;9(3):375–385. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25372k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun J. J., Han T., Yang T., Chen Y., Huang J. Interpreting the molecular mechanisms of Yinchenhao decoction on hepatocellular carcinoma through absorbed components based on network pharmacology. BioMed Research International . 2021;2021:22. doi: 10.1155/2021/6616908.6616908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q. X., Chen S. L., Wen X. P., Du G. L. Effect of Guizhi, the main drug of Wulingsan, on the renal protection of rats with adriamycin nephropathy. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine . 2019;60(2):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito T. Treatment and prognosis of idiopathic membranous nephropathy in guidelines for nephrotic syndrome. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi . 2011;53(5):708–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombel R. M., Gipson D. S., Hodson E. M. Treatment of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome: new guidelines from KDIGO. Pediatric Nephrology . 2013;28(3):415–426. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong W. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in New Zealand children, demographic, clinical features, initial management and outcome after twelve-month follow-up: results of a three-year national surveillance study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health . 2007;43(5):337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckardt K. U., Coresh J., Devuyst O., et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet . 2013;382(9887):158–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones P. J., Ntanios F. Y., Raeini-Sarjaz M., Vanstone C. A. Cholesterol-lowering efficacy of a sitostanol-containing phytosterol mixture with a prudent diet in hyperlipidemic men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 1999;69(6):1144–1150. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim B. H., Lee Y. G., Lee J., Lee J. Y., Cho J. Y. Regulatory effect of cinnamaldehyde on monocyte/macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators of Inflammation . 2010;2010:9. doi: 10.1155/2010/529359.529359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin L. T., Tai C. J., Chang S. P., Chen J. L., Wu S. J., Lin C. C. Cinnamaldehyde-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma PLC/PRF/5 cells involves the mitochondrial death pathway and is sensitive to inhibition by cyclosporin A and z-VAD-fmk. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry . 2013;13(10):1565–1574. doi: 10.2174/18715206113139990144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao Y., Huang H. Y., Yang Y. X., Guo J. Y. Cinnamic aldehyde treatment alleviates chronic unexpected stress-induced depressive-like behaviors via targeting cyclooxygenase-2 in mid-aged rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology . 2015;162:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang B., Yuan H. D., Kim D. Y., Quan H. Y., Chung S. H. Cinnamaldehyde prevents adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis via regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathways. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry . 2011;59(8):3666–3673. doi: 10.1021/jf104814t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikzamir A., Palangi A., Kheirollaha A., et al. Expression of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) is increased by cinnamaldehyde in C2C12 mouse muscle cells. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal . 2014;16(2):1–5. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F., Pu C. H., Zhou P., et al. Cinnamaldehyde prevents endothelial dysfunction induced by high glucose by activating nrf2. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry . 2015;36(1):315–324. doi: 10.1159/000374074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S. W., Park S. S., Min T. J., Yu K. H. Antioxidant activity of ergosterol peroxide (5,8-epidioxy-5a,8a-ergosta-6,22E-dien-3bo1) in Armillariella mellea. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society . 1999;20(7):819–823. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akihisa T., Franzblau S. G., Tokuda H., et al. Antitubercular activity and inhibitory effect on Epstein-Barr virus activation of sterols and polyisoprenepolyols from an edible mushroom, Hypsizigus marmoreus. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin . 2005;28(6):1117–1119. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo Y. C., Weng S. C., Chou C. J., Chang T. T., Tsai W. J. Activation and proliferation signals in primary human T lymphocytes inhibited by ergosterol peroxide isolated fromCordyceps cicadae. British Journal of Pharmacology . 2003;140(5):895–906. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takei T., Yoshida M., Ohnishi-Kameyama M., Kobori M. Ergosterol peroxide, an apoptosis-inducing component isolated fromSarcodon aspratus(Berk.) S. Ito. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry . 2005;69(1):212–215. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirata Y., Nagata D., Suzuki E., Nishimatsu H., Suzuki J. I., Nagai R. Diagnosis and treatment of endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease a review. International Heart Journal . 2010;51(1):1–6. doi: 10.1536/ihj.51.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eremina V., Sood M., Haigh J., et al. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. Journal of Clinical Investigation . 2003;111(5):707–716. doi: 10.1172/JCI17423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michael J. V., Wurtzel J. G., Goldfinger L. E. Regulation of H-Ras-driven MAPK signaling, transformation and tumorigenesis, but not PI3K signaling and tumor progression, by plasma membrane microdomains. Oncogene . 2016;5(5):e228–e228. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plotnikov A., Zehorai E., Procaccia S., Seger R. The MAPK cascades: signaling components, nuclear roles and mechanisms of nuclear translocation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta . 2011;1813(9):1619–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warmuth M., Damoiseaux R., Liu Y., Fabbro D., Gray N. Src family kinases: potential targets for the treatment of human cancer and leukemia. Current Pharmaceutical Design . 2003;9(25):2043–2059. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cordero J. B., Ridgway R. A., Valeri N., et al. c-Src drives intestinal regeneration and transformation. The EMBO Journal . 2014;33(13):1474–1491. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauman K. A., Wettlaufer S. H., Okunishi K., et al. The antifibrotic effects of plasminogen activation occur via prostaglandin E2 synthesis in humans and mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation . 2010;120(6):1950–1960. doi: 10.1172/JCI38369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi D., Nagahama K., Tsuura Y., Tanaka H., Tamura T. Sunitinib-induced nephrotic syndrome and irreversible renal dysfunction. Clinical and Experimental Nephrology . 2012;16(2):310–315. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang B. Z., Ramesh G., Uematsu S., Akira S., Reeves W. B. TLR4 signaling mediates inflammation and tissue injury in nephrotoxicity. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology . 2008;19(5):923–932. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khakpour S., Wilhelmsen K., Hellman J. Vascular endothelial cell toll-like receptor pathways in sepsis. Innate Immunity . 2015;21(8):827–846. doi: 10.1177/1753425915606525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gluba A., Banach M., Hannam S., Mikhailidis D. P., Sakowicz A., Rysz J. The role of Toll-like receptors in renal diseases. Nature Reviews. Nephrology . 2010;6(4):224–235. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaur H., Chien A., Jialal I. Hyperglycemia induced toll like receptor 4 expression and activity in mesangial cells: relevance to diabetic nephropathy. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology . 2012;303(8):1145–1150. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00319.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu K. C., Cheng K. S., Wang Y. W., et al. Perturbation of Akt signaling, mitochondrial potential, and ADP/ATP ratio in acidosis-challenged rat cortical astrocytes. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry . 2017;118(5):1108–1117. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park E. J., Park S. W., Kim H. J., Kwak J. H., Lee D. U., Chang K. C. Dehydrocostuslactone inhibits LPS-induced inflammation by p38MAPK-dependent induction of hemeoxygenase-1 in vitro and improves survival of mice in CLP- induced sepsis in vivo. International Immunopharmacology . 2014;22(2):332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida S., Nagase M., Shibata S., Fujita T. Podocyte injury induced by albumin overload in vivo and in vitro: involvement of TGF-beta and p38 MAPK. Nephron. Experimental Nephrology . 2008;108(3):e57–e68. doi: 10.1159/000124236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakim F. A., Pflueger A. Role of oxidative stress in diabetic kidney disease. Medical Science Monitor . 2010;16(2):37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munkonda M. N., Akbari S., Landry C., et al. Podocyte-derived microparticles promote proximal tubule fibrotic signaling via p38 MAPK and CD36. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles . 2018;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1432206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.