Abstract

Background

The impact of COVID-19 on mental health is tremendous. Since the beginning of the pandemic, several actors have raised concerns about the impact of the pandemic on gambling. Many actors fear a switch to online gambling in the context of the closure of many land-based gambling activities due to the restrictions imposed by public health authorities, such as physical distancing and lockdowns. This switch is worrisome because online gambling is considered a high-risk game. In that context, we need to know more about the impacts of the pandemic on gambling. This scoping review aims to summarize the literature that addresses the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on gambling. To our knowledge, this is the first review to focus on this subject.

Methods

An electronic literature search involving a strategy using keywords related to COVID-19 and gambling was conducted using MEDLINE, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, PsychINFO, Social Works Abstract, and Socio Index databases on February 25th 2021. This search was combined with a manual search in Google Scholar. To be included, studies had to discuss gambling and COVID-19 as a primary theme, be written in English, and be published in a peer-reviewed journal. After collecting the information, we collated, summarized, and reported the results using narrative synthesis.

Results

The search identified 181 articles. After the removal of duplicates and screening, 24 full-text articles were reviewed and included in this study: 14 original articles, 8 commentaries or editorials, and 2 protocols. Contrary to expectations, preliminary evidence suggested that gambling behavior often either decreased or stayed the same for most gamblers during the pandemic. However, for the minority who showed increased gambling behavior, there was frequently an association with problem gambling.

Conclusion

The available literature on COVID-19 and gambling is limited and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gambling behavior and gambling problems is still unclear. Therefore, there is a need for more research on this topic, both qualitative and mixed methods studies, to better understand the impact of the pandemic on gambling. Considering the results, we need to be careful, particularly with problem gamblers and other subgroups of the population who seem to be more vulnerable to increased gambling habits during this pandemic period.

Keywords: Gambling, COVID-19, Pandemic, Review, Addiction

1. Introduction

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are significant. The COVID-19 crisis is putting considerable pressure on individuals, industries, health systems, and the economy. The extent of collateral damage caused by the pandemic has only begun to be understood.

COVID-19 has created a mental health crisis. Symptoms of anxiety and depression appear to occur more frequently since the beginning of the pandemic (Rajkumar, 2020). In the past, it has been observed that people in isolation who are experiencing stress increase their use of substances, such as alcohol and drugs, to alleviate their negative emotions (Volkow, 2020). The same phenomenon has been observed regarding gambling during a crisis (Economou et al., 2019; Jiménez-Murcia et al., 2013; Olason et al., 2015).

Gambling disorder is a mental health issue that is becoming increasingly recognized as a major public health concern (Abbott, 2020; Delfabbro and King, 2020; Korn and Shaffer, 1999; Korn et al., 2003; Messerlian et al., 2005; Shaffer and Korn, 2002; van Schalkwyk et al., 2019; Wardle et al., 2019). The prevalence of gambling disorder is estimated to be between 0.12% and 5.8% (Potenza et al., 2019). In the DSM-5, gambling disorder is defined as persistent and recurrent problematic gambling behavior that can cause clinically significant impairment or distress (APA, 2013). In the general population, different scales that are used to assess problem gambling classify gamblers into non-problem gamblers, low-risk gamblers, moderate-risk gamblers, and problem gamblers (e.g., Problem Gambling Severity Index; Holtgraves, 2008).

Psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder, are common among “individuals with pathological gambling. 96% have been estimated to have one or more psychiatric disorders and 64% have been estimated to have three or more psychiatric disorders” (Kessler et al., 2008). This situation is of particular concern in the context of the current pandemic, in which anxiety and depressive symptoms seem to be on the rise (Rajkumar, 2020).

Since the beginning of the pandemic, several actors have raised concerns about the impact of the pandemic on gambling. Many actors fear a switch to online gambling in the context of the closure of many land-based gambling activities because of the restrictions imposed by public health authorities, such as physical distancing and lockdowns (Davies, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; King et al., 2020). The situation is worrisome, as online gambling is considered a high-risk activity given its accessibility, velocity, and, among others, the anonymity it provides (Gainsbury et al., 2015; Hing et al., 2015).

The purpose of this review is to summarize the literature that addresses the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on gambling. In the present context, conducting an up-to-date assessment of the situation to guide public policies related to gambling and to reduce the harm associated with gambling is important. As outlined by Langham et al. (2016), “[h]arm from gambling is known to impact individuals, families, and communities; and theses harms are not restricted to people with gambling disorder”.

2. Methods

This study is a scoping review. This type of review is generally used in new areas of research with emerging evidence to capture the current state of understanding (Anderson et al., 2008; Levac et al., 2010). More precisely, scoping reviews are “exploratory projects that systematically map the literature available on a topic, identifying the key concepts, theories, sources of evidence, and gaps in the research” (CIHR, 2010).

This scoping review followed the methodological framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley and refined by Levac et al. (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010). The process followed five key steps: 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The primary research question guiding this review is “What are the impacts of COVID-19 on gambling?”

This review follows the PRISMA guidelines for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018).

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

An electronic literature search was conducted on February 25th 2021, in six databases: MEDLINE with Full Text, CINAHL with Full Text, PsychINFO, Academic Search Complete, Social Work Abstract, and SocINDEX. An experienced information specialist helped develop a search strategy using a controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and keywords related to the concepts “gambling” (S1) and “COVID-19” (S2) (see Box 1 ). An electronic search was also conducted on Google Scholar to include all articles published until February 25th 2021. The search identified 181 articles.

Box 1.

Search strategy.

| S1: gambl* OR betting OR “electronic gaming machines” OR lotto OR casino OR poker OR bingo OR blackjack OR lottery OR “slot machine*” S2: covid OR coronavirus OR “2019-ncov” OR “sars-cov-2” OR “cov-19” OR pandemi* |

2.2. Study selection

Study eligible for the review needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) Main theme is related to both gambling and COVID-19; 2) English-language publication; 3) Published in a peer-reviewed journal.

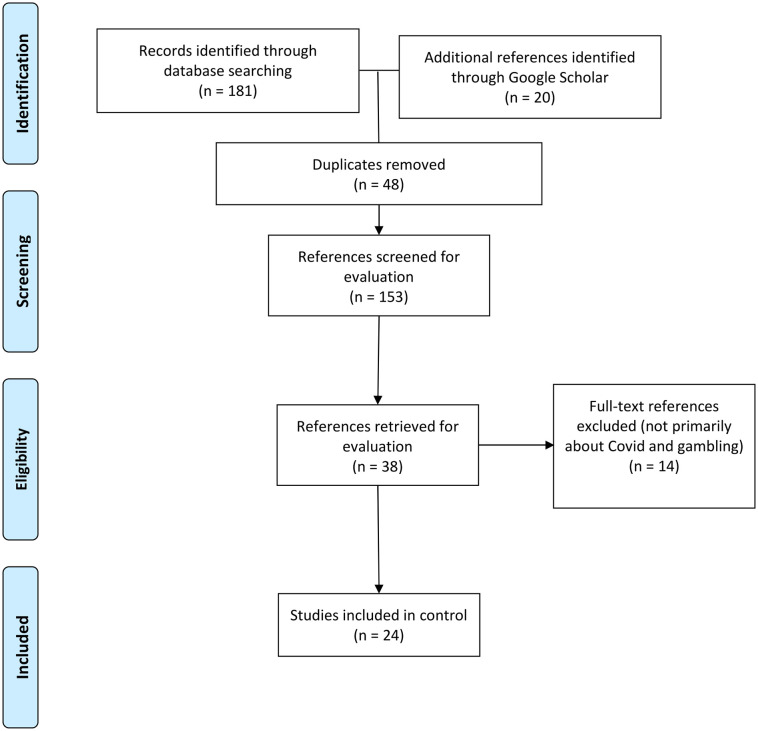

After the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were reviewed by SA-C to determine inclusion for full-text review. Two independent researchers, MB and SA-C, reviewed each article retained for full-text review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. 38 articles were retained for detailed evaluation by team members MB and SA-C. 14 of the 38 articles were excluded. A final sample of 24 articles was included in the review. As this is a review on an emerging theme, we included all relevant commentaries and editorials in our selection, and no critical appraisal was made (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the search strategy and study selection

2.3. Data extraction and reporting

Two researchers, MB and SA-C, extracted the information from the 24 articles. Descriptive characteristics, such as the names of authors, year, region/country, population, aim, design, and conclusion, were collected (see Table 1 ). After collecting the information, we collated, summarized, and reported the results using narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006). Narrative synthesis is an approach to synthesize “findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarize and explain the findings” (Popay et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Description of the included studies.

| Author, year | Title | Continent and country | Type | Objective | Methodology | Population and age | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auer et al. (2020) | Gambling Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic among European Regular Sports Bettors: An Empirical Study Using Behavioral Tracking Data | Europe (Sweden, Germany, Finland, Norway) | Original Research | “[I]nvestigate the behavior of a sample of online sports bettors before and after COVID-19 measures were put in place by European governments” | Quantitative (Data from a large European online gambling operator) | Regular online sports bettors (N = 5396). Age not mentioned. | “Overall, the frequency of wagering upon online casino games by online sport bettors before COVID-19-related lockdown significantly decreased during the COVID-19 Pandemic. […] Frequent online sports bettors wagering upon online casino game[s] stayed approximately the same before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings suggest that the speculations that individuals may spend more time and money gambling online as a consequence of being confined in their house for long periods of time appear unfounded.” |

| Czegledy (2020) | Canadian Land-Based Gambling in the Time of COVID-19 | North America (Canada) | Commentary | “Although it is still in progress, a review of the Canadian land-based gambling industry's response to date to the COVID-19 pandemic is a useful illustration of how decisive, concerted and cooperative planning and action can set the stage for economic recovery once associated risks to health and safety are ameliorated. It provides, in addition, a strong indication of certain trends that will likely shape how the industry develops in the years to come.” | N/A | N/A | “At the time of this writing, many Canadian gambling business remain shuttered, operating at partial capacity, or operating subject to severe restrictions or strict conditions. The pandemic is still active, with vaccines yet to be found. It continues to force society and industry to re-evaluate how they operate. Many would say this is long overdue in regard to the gambling industry, including in Canada—and therefore perhaps there is a silver lining to be found even in such trying times.” |

| Donati et al. (2021) | Being a Gambler during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study with Italian Patients and the Effects of Reduced Exposition | Europe (Italy) | Original Research | The aim of this study is to “[a]nalyze patients' gambling behavior and craving during the lockdown and to conduct a comparison between gambling disorder (GD) symptoms at the beginning of the treatment and during lockdown.” | Quantitative (phone survey) | N = 135 | “During the 3 months lockdown, “most PGs achieved a significant improvement in their quality of life, with less gambling behavior, GD symptoms, and lower craving. No shift toward online gambling and very limited shift toward other potential addictive and excessive behaviors occurred. The longer the treatment, the more monitoring is present and the better the results in terms of symptoms reduction. Individual and environmental characteristics during the lockdown favored the reduction in symptoms.” |

| All are problem gamblers (PG) under treatment | |||||||

| 109 men | |||||||

| Age mean = 50.07 years old | |||||||

| Frisone et al. (2020) | Problem Gambling During Covid-19 | Europe (Italy) | Original Research | “This pilot study highlights if the problem gambling, during a period of isolation such as that of COVID-19, can be explained by personality or sociodemographic characteristics, therefore it investigates the emotional and impulsive characteristics of problem gamblers and examines whether those who are adults, those who have more years of study or who work are less likely to have problem gambling.” | Quantitative (Online survey) | N = 200 | “The results of this exploratory research suggest that in a period characterized by a pandemic, problem gambling is associated with some personality and sociodemographic characteristics. Moreover, age, male gender, low levels of study and impulsive characteristics play a decisive role in problem gambling.” |

| 62.5% women | |||||||

| Age 16–80 | |||||||

| Age mean = 31.19 years old | |||||||

| Gainsbury et al. (2020) | Impacts of the COVID-19 Shutdown on Gambling Patterns in Australia: Consideration of Problem Gambling and Psychological Distress | Australia | Original Research | The aim of this study is to “investigate the impact of the shutdown of gambling venues on Australians, particularly among those vulnerable to mental health problems and gambling disorder.” | Quantitative (Online cross-sectional survey) | N = 764 | “Most people moderated their gambling when venue-based gambling was unavailable and opportunities for sports betting were limited. However, harms experienced by individuals with some gambling problems may have been exacerbated during the period of limited access. Policies to enhance prevention and treatment of gambling problems are necessary even when availability is reduced.” |

| Australian adults who had gambled at least once in the past 12 months | |||||||

| 85.2% male | |||||||

| George (2020)) | “Holidays” in People Who Are Addicted to Lotteries: A Window of Treatment Opportunity Provided by the COVID-19 Lockdown | Asia (India) | Editorial | Reflect on the observed increase in demand in psychiatric treatment after lockdown, from people with lottery addiction. | N/A | N/A | “Lockdown […] provided a crucial window of opportunity for lottery addicts to seek treatment (detoxification and rehabilitation), and to turn their (and their families') lives around. It needs to be borne in mind that such ‘clinical observations’ need to be substantiated and followed up by ‘evidence-based’ systematic research. [S]uch lottery ‘holidays’ [might be] worth considering a public health prevention strategy to encourage more lottery addicts to receive treatment and support, thereby benefiting them and their families.” |

| Griffiths et al. (2020) | Pandemics and Epidemics: Public Health and Gambling Harms | Europe (UK) | Editorial | Introduce the special issue of Public Health entitled “Gambling: An Emerging Public Health Challenge” to facilitate mature debate and “help public health, primary care, and healthcare professionals see that gambling harms contribute to many of the social and economic inequalities that are determinants of health and well-being for individuals, their families and the communities in which they live” | N/A | N/A | “We all recognise that the world into which we will return will be very different, and within that new world, we will have an opportunity to do things differently. Once the immediate pandemic is past its peak and lockdown is slowly released, the public health community will refocus on what recovery will be needed and begin planning for the new normal. With this pandemic, we are already seeing questions being asked about how we can ‘reset’ rather than ‘recover’.” |

| Håkansson (2020a) | Changes in Gambling Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Web Survey Study in Sweden | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “examine whether self-reported gambling has increased during the pandemic, and to examine the potential correlates of such a change” | Quantitative (Cross-sectional web survey) | General population (N = 2016). At least 18 years old. | “Although the number of individuals reporting a gambling increase was smaller than the number reporting a decrease, and although the large majority reported no change, it can be concluded that increasing overall gambling […] is clearly associated with having a higher degree of gambling problems […] given the potential vulnerability in that group, there is reason to take action in order to prevent crisis-related increases in gambling.” Furthermore, “the link between alcohol and gambling is particularly important to address and to prevent during the crisis.” |

| Håkansson (2020b) | Impact of Covid-19 on Online Gambling – A General Population Survey During the Pandemic | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “Describe [the] past-30-day use of different gambling types during the COVID-19 pandemic in individuals defined as online gamblers, in order to enable a comparison with past-30-day data reported from a previous survey in online gamblers carried out in 2018″ | Quantitative (Web panel) | Past year online gamblers (N = 997). At least 18 years old. | “Those reporting sports betting even during a period with decreased sports betting occasions proved to have markedly higher gambling problems. COVID-19 may alter gambling behaviors, and online gamblers who maintain or initiate gambling types theoretically reduced by the crisis may represent a group at particular risk.” |

| Håkansson (2020c) | Effects on Gambling Activity from Coronavirus Disease 2019-An Analysis of Revenue-Based Taxation of Online- and Land-Based Gambling Operators During the Pandemic | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “The present study aimed to assess changes in the online and land-based gambling markets in Sweden during the first months affected by the societal impact of COVID-19.” | Quantitative | N/A (tax data analysis) | “Commercial online gambling operators' revenues remained stable throughout the pandemic, despite the dramatic lockdown in sports. Thus, chance-based online games may have remained a strong actor in the gambling market despite the COVID-19 crisis, in line with previous self-report data. A sudden increase in horse betting during the sports lockdown and its decrease when sports reopened confirm the picture of possible COVID-19-related migration between gambling types, indicating a volatility with potential impact on gambling-related public health.” |

| “[N]ational authority data describing monthly taxations of all licensed Swedish gambling operators […] Subdivisions of the gambling market were followed monthly from before COVID-19 onset […] through June 2020” | |||||||

| Håkansson et al. (2021) | No Apparent Increase in Treatment Uptake for Gambling Disorder during Ten Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic—Analysis of a Regional Specialized Treatment Unit in Sweden | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “The present study assessed the treatment uptake at a regional specialized gambling-disorder unit in the healthcare system of Region Skåne, Sweden” | Quantitative data analysis from 2018, 2019 and 2020 (number of patients treated at a Gambling Disorder Unit) | N/A (data analysis of the number of patients) | “[D]uring the first 10 months of the pandemic in Sweden, no obvious increase in treatment uptake for gambling disorder could be seen. Moreover, longer follow-up may be necessary in order to see if effects of worsening socioeconomic conditions may be a possible long-term risk factor of increased gambling after COVID-19.” |

| Håkansson et al. (2020a) | Gambling During the COVID-19 Crisis – A Cause for Concern | Europe (not specific) | Commentary | “[D]escribe observations suggesting that the current crisis and its sequelae may worsen problem gambling […] [because it] may impact financial and psychological well-being […]” | N/A | N/A | “In summary, when facing an unforeseen situation with confinement, fear of disease and financial uncertainty for the future, problem gambling may be an important health hazard to monitor and prevent during and following the COVID-19 crisis, especially given current online gambling availability. To date, research data are limited, and rapid action should be taken by researchers and stakeholders worldwide.” |

| Håkansson et al. (2020b) | Psychological Distress and Problem Gambling in Elite Athletes during COVID-19 Restrictions-A Web Survey in Top Leagues of Three Sports During the Pandemic | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “This study in top elite athletes aimed to study current perceived psychological influence from COVID-19 and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and changes in alcohol drinking, gambling behavior, and problem gambling in the midst of the COVID-19 lockdown.” | Quantitative (Web survey) | Athletes in top leagues of football, ice hockey, and handball (N = 327). At least 15 years old. | “Depression and anxiety were not markedly higher than expected but were associated with COVID-19-related descriptions of worry. Fear of increased gambling during the crisis could not be clearly demonstrated, but at-risk gambling in male athletes was common and also linked to an increase in gambling during the pandemic. Psychological influence from the pandemic or other enduring crisis should be further addressed in athletes and more research is needed, including in-depth study design and studies beyond the specific sports assessed here.” |

| Hunt et al. (2020) | Protocol for a Mixed-Method Investigation of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Gambling Practices, Experiences and Marketing in the UK: The “Betting and Gaming COVID-19 Impact Study” | Europe (United Kingdom) | Study Protocol | This study aims to answer these three questions: “(1) How has COVID-19 changed gambling practices and the risk factors for, and experience of, gambling harms? (2) What is the effect of COVID-19 on gambling marketing? (3) How has COVID-19 changed high risk groups' gambling experiences and practices?” | Qualitative and quantitative (Mixed-method study), including: extension of a longitudinal survey, content analysis of paid-for-gambling-advertising, and qualitative interviews | Young adults (16–24 years old) and sport bettors | “Collecting timely data on the ways in which patterns and experiences of gambling change in key groups of people engaged in betting and gambling, alongside data on marketing spend and approaches, will be essential to informing regulatory bodies and others concerned with the prevention and treatment of gambling harms.” |

| Lindner et al. (2020) | Transitioning between Online Gambling Modalities and Decrease in Total Gambling Activity, but No Indication of Increase in Problematic Online Gambling Intensity During the First Phase of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Sweden: A Time Series Forecast Study | Europe (Sweden) | Original Research | “[T]o examine whether the first phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden was associated with an increase in overall gambling activity on a population level, whether high-intensity online gamblers were particularly affected, and whether online gamblers transitioned between gambling modalities” | Quantitative (Data from gambling authorities and the gambling industry) | Gamblers and online gamblers (analysis of aggregated datasets). Age not mentioned. | “[N]o indication of increased total gambling activity in the first phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden [was found] and the social distancing procedures introduced to combat it. Although betting decreased substantially in synchrony with a slight increase in online casino gambling, there was no increase in high-intensity, likely problematic gambling as per the Swedish government's own definition, and neither did total online gambling increase. Future research is required to examine the impact of the outbreak over longer periods of time, on different types of gambling and on subgroups of gamblers, including problem gamblers, preferably using behavior tracking of individual gambling accounts.” |

| Lischer et al. (2021) | The Influence of Lockdown on the Gambling Pattern of Swiss Casinos Players | Europe (Switzerland) | Original Research | Study the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on “gambling behavior. Particularly, changes in self-reported gambling by Swiss, land-based casino players” | Quantitative (online questionnaire) | N = 110 | “Considering only those respondents (n = 66) who reported having gambled during lockdown, gambling intensity also decreased (p < 0.001), but online gambling significantly increased (p < 0.002). Those players who have increased their gambling activity require particular attention. It is important that casinos respond with appropriate player protection measures to those who have increased their gambling activity during the pandemic.” |

| All are players who were previously banned from Swiss Casinos | |||||||

| This study is part of a broader “ongoing online longitudinal study, which evaluates the influence of voluntary and imposed exclusion as a player protection measure” | |||||||

| Ng Yuen and Bursby (2020) | Are all Bets Off? The Reopening of Casinos, Bingo Halls, and Other Gambling Establishments in Post-Lockdown UK | Europe (United Kingdom) | Commentary | “This article considers the ways the UK government and the devolved governments of Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland have worked together during lockdown, and how their different approaches to reopening their respective economies, in particular casinos, bingo halls, and other gambling establishments, has created additional challenges for the sector.” | N/A | N/A | “While many gambling establishments in England are relieved to be open, those in other parts of the UK continue to remain in a state of uncertainty as to when they will reopen and how they will recover. Even those gambling establishments that have reopened continue to exist in a state of financial uncertainty […][and] the stakes remain high for this sector.” |

| Price (2020) | Online Gambling in the Midst of COVID-19: A Nexus of Mental Health Concerns, Substance Use and Financial Stress | North America (Canada) | Original Research | “[Examine] the emerging impact of COVID-19 on gambling during the first 6 weeks of emergency measures in Ontario, Canada.” Assess risky gambling behaviors and motivations, financial impacts from COVID-19, influence of COVID-19 on online gambling, mental health concerns and substance use. | Quantitative (Cross-sectional online survey) | Gamblers (N = 2005), including online gamblers (N = 1081). At least 18 years old. | “This study has confirmed many of the risk associations presented in past research on global economic crisis, gambling risk, mental health concerns and substance use. However, unlike many past studies, the present paper takes note of all of these elements together and provides a clear emphasis on online gambling. Together, the strength of high-risk gambling motives in predicting problematic gambling status, mental health concerns, financial difficulties and risky substance use among online gamblers was a novel insight worth further exploration.” |

| Sharman et al. (2021) | Gambling in COVID-19 Lockdown in the UK: Depression, Stress, and Anxiety | Europe (United Kingdom) | Original Research | This study aims to understand the impact of around 6 weeks of lockdown on gambler's mental health. | Quantitative (Online questionnaire) | N = 1028 | “Results indicate that depression, stress and anxiety has increased across the whole sample. Participants classified in the PPG group reported higher scores on each sub scale at both baseline and during lockdown. Increases were observed on each DASS21 subscale, for each gambler group, however despite variable significance and effect sizes, the magnitude of increases did not differ between groups. Lockdown has had a significant impact on mental health of participants; whilst depression stress and anxiety remain highest in potential problem gamblers, pre-lockdown gambler status did not affect changes in DASS21 scores.” |

| All are gamblers | |||||||

| 72% female | |||||||

| Age mean = 33.19 years old | |||||||

| Sharman (2020) | Gambling in Football: How Much is Too Much? | Europe (UK) | Commentary | “This commentary seeks to explore the changing nature of [the relationship between football and gambling], how [it] has been affected by COVID-19, and how [it] may change in the future.” | N/A | N/A | “Gambling has long been a part of football and will undoubtedly retain a presence within the sport in the future, however the nature of its relationship […] with gambling companies, […] it is clear there is a growing appetite at [the] legislative level to loosen the grip of the gambling industry on football in the UK. The relationship may look very different as football moves into the future.” |

| Turner (2020) | Covid-19 and Gambling in Ontario | North America (Canada) | Editorial | Discuss the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on problem gambling in Ontario using data from the Ontario Problem Gambling Helpline and ConnexOntario Helpline data | N/A | N/A | “[T]he pandemic resulted in a sharp decrease in the number of calls related to problem gambling. […] [But] one clear effect of the pandemic is a sharp increase in the number of people making telephone calls to [other] crisis [helplines] […]. In conclusion, the drop in helpline numbers suggests that the pandemic may in fact be leading to a decrease in the number of persons who are in crisis over gambling problems. The Covid-19 pandemic is clearly negatively affecting people's mental health […]” |

| Wardle et al. (2021) | The Impact of the Initial Covid-19 Lockdown Upon Regular Sports Bettors in Britain: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Online Study | Europe (United Kingdom) | Original Research | This study aims to “observe changes in sports bettors' behavior when their primary form of activity is removed and assess the impact of Covid-19 related circumstances upon gambling.” | Quantitative (Cross-sectional online study) | N = 3866 | “Whilst a reduction in gambling was the norm for most regular sports bettors during the initial Covid19 lockdown in Britain, some started new forms of gambling or increased their frequency of gambling on other activities, a factor associated with indicators of problem gambling. Among men, those who switch forms of gambling under lockdown conditions should thus be considered vulnerable to harms, as should women who increased their frequency of gambling on any activity. Among women, shielding status and poorer wellbeing were also associated with the experience of gambling harms during Britain's initial Covid-19 lockdown. Hence, those facing these challenges should be considered potentially vulnerable to gambling harms. Regulators and industry should take action to further protect these emerging vulnerable groups.” |

| 3084 men | |||||||

| All were regular sports bettors before the Covid-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Wardle (2020) | The Emerging Adults Gambling Survey: Study Protocol | Europe (UK) | Study Protocol | “It aims to explore a range of gambling behaviors and harms among young adults and examine how this change over time [two wave of data collection]. […] This study will enable some examination of the immediate impact of COVID-19 on gambling behaviors.” | Quantitative (Longitudinal survey/online panel) | Young adults living in the UK and aged between 16 and 24 years old (N = 3549) | “This protocol is intended to support other researchers to use this resource by setting out the study design and methods.” |

| Yahya and Khawaja (2020) | Problem Gambling during the COVID-19 Pandemic | Europe (UK) | Commentary | Express concern about the “prediction of [the] socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic [which risk] not only [to] exacerbate the symptoms of those with existing illness but also contribute to new cases occurring” | N/A | N/A | Physicians must be “aware that gambling behaviors may escalate during and after the COVID-19 pandemic […] [and should] routinely ask about problem gambling when patients present with possible risk factors for the condition. Early identification and management are essentials to prevent adverse consequences and significant impairment.” |

3. Results

3.1. Study characteristics

The majority of the 24 studies were published in 2020 (Auer et al., 2020; Czegledy, 2020; Frisone et al., 2020; Gainsbury et al., 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2020a, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Hunt et al., 2020; Lindner et al., 2020; Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020; Price, 2020; Sharman, 2020; Turner, 2020; Wardle, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020), while 6 of the studies were published in 2021 (Donati et al., 2021; George, 2020, Håkansson et al., 2021; Lischer et al., 2021; Sharman et al., 2021; Wardle et al., 2021).

Nineteen studies were from Europe, including six from Sweden (Håkansson et al., 2021; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2020b; Lindner et al., 2020), eight from the UK (Griffiths et al., 2020; Hunt et al., 2020; Sharman, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021, Wardle, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020; Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020), two from Italy (Donati et al., 2021; Frisone et al., 2020), one from Switzerland (Lischer et al., 2021) and two from a non-specific country or multiple countries (Auer et al., 2020; Håkansson et al., 2020a). Three articles were from North America (all from Canada; Czegledy, 2020; Price, 2020; Turner, 2020), one from Australia (Gainsbury et al., 2020), and one from Asia (India) (George, 2020). Country and region of origin were established by cross-referencing the country and region of origin of the authors and the content of the articles.

Fourteen studies were original articles (Auer et al., 2020; Donati et al., 2021; Frisone et al., 2020; Gainsbury et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2020b; Håkansson et al., 2021; Lindner et al., 2020; Lischer et al., 2021; Price, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021; Wardle et al., 2020), eight were commentaries or editorials (Czegledy, 2020; George, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; Håkansson et al., 2020a; Sharman, 2020; Turner, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020; Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020), and two were protocols (Hunt et al., 2020; Wardle, 2020) (see Table 1).

3.2. Methodology

All fourteen original studies used a quantitative design or mixed-design. Among them, 4 studies used data from the industry, gambling authorities, or data from gambling treatment centers (Auer et al., 2020; Lindner et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2021), whereas 10 used a web-based survey or panel (Frisone et al., 2020; Gainsbury et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b; Håkansson et al., 2020b; Lischer et al., 2021; Price, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021; Wardle et al., 2020) and one used a phone survey (Donati et al., 2021). One protocol used a web-based panel (Wardle, 2020), while the other one, being a mixed-method study, used both a qualitative and quantitative design (Hunt et al., 2020). As expected, the commentaries or editorial articles did not provide any methodology.

3.3. Type of gambling

Eighteen studies focused on gambling, in general, during the pandemic (Czegledy, 2020; Donati et al., 2021; Frisone et al., 2020; Gainsbury et al., 2020; George, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a; Håkansson et al., 2021, Håkansson et al., 2020a, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Hunt et al., 2020; Lischer et al., 2021; Lindner et al., 2020; Sharman et al., 2021; Turner, 2020; Wardle, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020; Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020). Three addressed sports betting (Auer et al., 2020; Sharman, 2020; Wardle et al., 2020), and four have a particular interest in online gambling (Auer et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Price, 2020).

3.4. Populations studied

Seventeen articles studied general populations, gamblers in general, or gamblers 18 years old and above (Auer et al., 2020; Czegledy, 2020; Donati et al., 2021; Gainsbury et al., 2020; George, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2021, Håkansson et al., 2020a; Lindner et al., 2020; Price, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021; Sharman, 2020; Turner, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020). Four studies included gamblers aged less than 18 years (Frisone et al., 2020; Håkansson et al., 2020b; Hunt et al., 2020; Wardle, 2020). Two articles looked at emerging adults aged between 16 and 24 years (Hunt et al., 2020; Wardle, 2020). One article focused on elite athletes at least 15 years old (Håkansson et al., 2020b), one on sport bettors that were already regular bettors before the pandemic (Wardle et al., 2020), one on previously banned casino gamblers before the pandemic (Lischer et al., 2021), and one article focused on gambling institutions and authorities during the pandemic (Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020).

3.5. Impact of COVID-19 on gambling

In all articles, the authors raised concerns about the impact of the pandemic on gamblers or the gambling industry (Auer et al., 2020; Czegledy, 2020; Donati et al., 2021; Frisone et al., 2020; Gainsbury et al., 2020; George, 2020; Griffiths et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2021, Håkansson et al., 2020a, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Hunt et al., 2020; Lindner et al., 2020; Lischer et al., 2021; Price, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021, Sharman, 2020; Turner, 2020; Wardle, 2020; Wardle et al., 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020; Ng Yuen and Bursby, 2020). Contrary to expectations, ten of the original studies reported that gambling behaviors decreased or stayed the same for most gamblers (Auer et al., 2020; Donati et al., 2021; Gainsbury et al., 2020; Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2021, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Lindner et al., 2020; Wardle et al., 2020).

Lindner et al. (2020) demonstrated that the “total gambling activity decreased by 13.29% during the first phase of the outbreak compared to [the] forecast. Analyses of online gambling data revealed that although betting decreased substantially in synchrony with a slight decrease in online casino gambling, there was no increase in likely problematic, high-intensity gambling and neither did total online gambling increase”. Håkansson (2020) found that only “four percent [4%] reported an overall gambling increase during the pandemic”. In another study on elite athletes, Håkansson et al. (2020b) outlined that “gambling increase during the pandemic was rare but [was] related to gambling problems”. In contrast, Donati et al. (2021) finds that even problem gamblers reduced their gambling behaviors and gambling cravings during the pandemic, and that no “shift toward online gambling and very limited shift towards other potential addictive and excessive behaviors” were found. Auer et al. (2020) also reached a similar conclusion, noting that “speculations that individuals may spend more time and money gambling online as a consequence of being confined in their house for long periods appear unfounded”.

The exact risk factors associated with increased gambling behavior and gambling problems during the COVID-19 pandemic are still unclear. In five studies, the rare increases observed were always attributed to high-risk gamblers (Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b; Håkansson et al., 2020a, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Lindner et al., 2020). According to Håkansson (2020), “increased gambling was independently and clearly associated with the problem gambling severity.” In their study, Gainsbury et al. (2020) rather found that “individuals engaged in moderate-risk gambling, but not problem gambling, were more likely to report increased gambling frequency” during the pandemic. Frisone et al. (2020) found that problem gambling during the pandemic was mostly associated with “personality and sociodemographic characteristics”, such as “age, male gender, low levels of study and impulsive characteristics play a decisive role in problem gambling”.

Regarding the feared shift to online gambling, Auer et al. (2020) noted that “there was no conversion of money spent from sports betting to online casinos games […] and that frequent online sports bettors wagering upon online casino games stayed the same before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Håkansson (2020) reported that “the minority reporting a switch to other gambling had a clear picture of problematic gambling involvement.” He also came to the same conclusion in another study conducted with colleagues (Håkansson, 2020b). Lindner et al. (2020) concluded that “although betting decreased substantially in synchrony with a slight increase in online casino gambling, there was no increase in high-intensity, likely problematic gambling”. In contrast, a more recent study (Lischer et al., 2021) found a significant increase (p < 0.002) in online gambling among the studied population, and Håkansson (2020c) mentions an important “increase in horse betting during the sports lockdown” and warns against a “possible COVID-19-related migration between gambling types, indicating a volatility with potential impact on gambling-related public health.”

In four articles, an association between gambling and related known comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder, was highlighted (Håkansson, 2020; Håkansson et al., 2020b; Price, 2020; Sharman et al., 2021). In his study of gambling behavior, Håkansson (2020) noted that “the group reporting increased gambling had higher rates of psychological distress […] and one of the clearest findings of the study has been that self-reported increase in alcohol consumption during the pandemic is associated with a self-reported increase in gambling.” In his study, Price (2020) observed that “gambling under the influence of alcohol or cannabis increased the odds of high-risk gambling status by approximately 9 times (p < 0.01) […] and those screened for [a] moderate and severe form of anxiety (25.7%) and depression (12.6%) were more likely to gamble online during the first 6 weeks of emergency measures and be classified as high-risk gamblers.” In their commentary exploring gambling during COVID-19, Håkansson et al. (2020a) cited a pilot study conducted early in the pandemic at the Gambling Disorder and Other Behavioral Addictions Unit of the Department of Psychiatry at the University Hospital of Bellvitge in Barcelona, Spain; the study found that “after two weeks of confinement, 12% […] reported worsening gambling […] 46% showed anxiety symptoms and 27% showed depressive symptoms” (Håkansson et al., 2020a). Sharman et al. (2021) found that the impact of lockdown was significant on the “mental health of participants; whilst depression stress and anxiety remain highest in potential problem gamblers”. Interestingly, in Ontario, Canada, Turner (2020) reported a decrease in calls to the National Gambling Helpline in the first weeks of the pandemic. However, this decrease was counterbalanced by a significant increase in calls in other crisis lines.

In commentaries and editorials, some authors expressed concern that access to care and services for gamblers and support groups, such as Gamblers Anonymous, has been limited because of the pandemic (Turner, 2020; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020); they outlined the need to raise awareness about problem gambling among the public and health professionals (Håkansson et al., 2020a; Yahya and Khawaja, 2020). For their part, Griffiths et al. (2020) believed that COVID-19 is likely to create many more vulnerable people and exacerbate existing inequalities. George (2020) mentions that the pandemic creates a rare window of opportunity that should be seized, as lockdown is a favorable moment for treatment, detoxification, and rehabilitation of problem gamblers, as there are reduced opportunities to gamble.

Some authors also focused on public policies put in place regarding gambling in response to the pandemic. As pointed out by Håkansson (2020) in the introduction of his article, “the overall concerns about an altered gambling behavior during the crisis have led several governments to take action through different measures, such as a limitation in gambling advertisements in Spain, deposit limits in Belgium, and a total ban in Latvia”. In Sweden, the government has adopted legislation limiting deposits in online casinos and a limit on time spent gaming (Lindner et al., 2020). Hunt et al. (2020) insists on the “urgent need to provide regulators, policymakers and treatment providers with evidence on the patterns and context of gambling during COVID-19 and its aftermath”, essential to alleviate gambling harms. Gainsbury et al. (2020), warn that policies need to be very well thought of. Too restrictive policies can lead to an increase of other forms of unregulated gambling activities that are known to exacerbate gambling issues.

The impact of the pandemic on the gambling industry has likewise been briefly discussed by some authors. Indeed, the gambling market has been considerably transformed by the pandemic. As outlined by Griffiths et al. (2020), some operators have shown creativity by creating drive-thru gambling centers. However, as mentioned by Sharman (2020), the industry acted cautiously in some countries. In the UK, the most notable changes to gambling […] regulation have come from industry-led self-regulation initiatives. Members of the Betting and Gaming Council […] agreed to a 10-point pledge during lockdown to encourage ‘safer gambling’, […] which was augmented by a voluntary reduction in gambling advertising on TV and radio”. Czegledy (2020) suggest that the pandemic lockdowns should be used to implement long-needed changes within the land-based gambling industry, such as a complete re-evaluation of their operations. Ng Yuen and Bursby (2020) concerned for the increased uncertainty of the gambling industry sector, as caused by the pandemic.

During the past few years, gambling has been a public health issue that has attracted the increased attention of policymakers and sports associations. In pre-pandemic Europe, different authorities were trying to create distance between some sports, mainly football, and gambling (Sharman, 2020). However, because of the pandemic, some football clubs found themselves in a precarious financial situation. This highlighted “how financially linking clubs [are] on gambling money” (Sharman, 2020). This financial dependence on gambling money is of concern to Griffiths et al. (2020), who noted that it “may also be tempting for governments to use gambling expansion and its subsequent revenues to recover resources which will be a priority with the inevitable economic depression looming”.

4. Discussion

The impacts of the pandemic on gambling are sprawling. To our knowledge, this review is the first to focus specifically on gambling and COVID-19. It provides an overview of the literature on gambling and COVID-19 published from the beginning of the pandemic until February 25th 2021. The preliminary results seem to point to an overall decrease in gambling since the beginning of the pandemic and suggest that problem gamblers appear to be at a greater risk.

Several limitations of this review should be outlined. First, it contains only published peer-reviewed articles and does not include grey literature. Second, in the original articles, six out of fourteen were from Sweden (Håkansson, 2020a, Håkansson, 2020b, Håkansson, 2020c; Håkansson et al., 2021, Håkansson et al., 2020b; Lindner et al., 2020). As there was no lockdown during the first wave of the pandemic in Sweden (Warren et al., 2021), and some gambling restrictions, such as limited deposits and limited game times, were not applied in other countries (Lindner et al., 2020), the results may be different in other jurisdictions and are therefore not generalizable. In that context, we must be careful and not conclude that the pandemic has not produced an exacerbation of gambling. Problem gamblers seem to be at risk. This is a previously known vulnerable group for whom it is important to remain vigilant, especially in the present context in which symptoms of anxiety and depression are on the rise (Rajkumar, 2020).

So far, the literature on the subject remains limited. Indeed, no qualitative or mixed studies have been published. A better understanding of the experience of gamblers during the pandemic is essential. As outlined by Auer et al. (2020), “The decrease in overall gambling might be due to several factors including individuals having less money to gamble because their occupational earning potential has been lower during the pandemic, individuals not wanting to gamble in front of their family members, or individuals spending more time on other activities such as spending ‘quality time’ with their families or finally having the time to do bigger jobs around the house and garden”. In that context, we need to know more about such hypotheses. There is also a lack of studies on certain populations, such as LGBTQ+ and Aboriginal people. Finally, comparative studies on gambling policies adopted during the pandemic, the impacts of COVID-19 on the gambling industry, and alternative forms of gambling developed by gamblers, such as teenage football games or amateur low-tier friendship games, as outlined by Håkansson et al. (2020a), are necessary.

It is important to note that this review covers articles published until February 25th, 2021. In that context, a larger number of included studies have mostly or exclusively focused on the first wave of the pandemic. Longitudinal studies or studies covering the impact of the entire pandemic on gambling and of subsequent waves are needed. Studies from around the world are also required to obtain a more complete picture of the problem. Given that the literature on gambling and COVID-19 is rapidly evolving, further reviews on the subject will be needed by the end of the pandemic. As noted by Griffiths et al. (2020), “even in the midst of the pandemic, we need to be aware that gambling harms are still occurring”.

5. Conclusion

The current literature indicates that problem gamblers, among others, are particularly vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic and that resources are needed to help and prevent increased harm. The pandemic still being active to this day, future research will be needed on this topic. Unforeseen consequences, impacts, and behavioral reactions are probable as the different waves of the pandemic are also situated in evolving contexts around the world. Future research should adopt a variety of methodology designs and focus on different populations and geographical areas, to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gambling. They will be necessary to reduce gambling harms and help the most vulnerable populations.

Author statement

This material is the authors' own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

All authors reviewed and accepted the final version of the article.

Ethical statement

This research included no animal or human subjects.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health and Social Services of the Government of Quebec in collaboration with the Quebec Research Fund and the Ministry of Innovation and Economy as part of the COVID-19 call for solutions (grant number #20-CP-00309). The funding body is not involved in the research, and the researchers are independent.

Authors' contributions

MB and SA-C designed the study and developed the search strategy. Study selection and data extraction were done by MB and SA-C. MB was responsible for drafting this manuscript and was supported by SAC, ACS, and SK. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Annie Desjardins, patient-partner, for her involvement in the study and the revision of the review.

References

- Abbott M.W. Public Health; 2020. The Changing Epidemiology of Gambling Disorder and Gambling-Related Harm: Public Health Implications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S., Allen P., Peckham S., Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2008;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . 5th ed. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auer M., Malischnig D., Griffiths M.D. Gambling before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among european regular sports bettors: an empirical study using behavioral tracking data. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00327-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIHR A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis - CIHR [WWW Document] 2010. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41382.html URL. (accessed 12.10.20)

- Czegledy P. Canadian land-based gambling in the time of COVID-19. Gaming Law Rev. 2020;24:555–558. [Google Scholar]

- Davies R. Frequent gamblers betting more despite coronavirus sports lockdown, study says. Guardian. 2020 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/24/growth-in-problem-gambling-amid-coronavirus-lockdown [WWW Document] URL. (accessed 12.11.20) [Google Scholar]

- Delfabbro P., King D.L. On the limits and challenges of public health approaches in addressing gambling-related problems. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Addict. 2020;18(3):844–859. [Google Scholar]

- Donati M.A., et al. Being a gambler during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study with Italian patients and the effects of reduced exposition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:424. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou M., Souliotis K., Malliori M., Peppou L.E., Kontoangelos K., Lazaratou H., Anagnostopoulos D., Golna C., Dimitriadis G., Papadimitriou G., Papageorgiou C. Problem gambling in Greece: prevalence and risk factors during the financial crisis. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019;35:1193–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisone F., Alibrandi A., Settineri S. Problem gambling during Covid-19. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020;8:3. [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S.M., Russell A., Wood R., Hing N., Blaszczynski A. How risky is internet gambling? A comparison of subgroups of internet gamblers based on problem gambling status. New Media Soc. 2015;17:861–879. doi: 10.1177/1461444813518185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S.M., Swanton T.B., Burgess M.T., Blaszczynski A. Impacts of the COVID-19 shutdown on gambling patterns in Australia: consideration of problem gambling and psychological distress. J. Addict. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000793. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S. “Holidays” in people who are addicted to lotteries: a window of treatment opportunity provided by the COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;36:6. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S., Reith G., Wardle H., Mackie P. Pandemics and epidemics: public health and gambling harms. Public Health. 2020;184:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A. Changes in gambling behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic—a web survey study in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:4013. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A. Impact of COVID-19 on online gambling – a general population survey during the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:568543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A. Effects on gambling activity from coronavirus disease 2019-an analysis of revenue-based taxation of online and land-based gambling operators during the pandemic. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:611939. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.611939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A., Fernández-Aranda F., Menchón J.M., Potenza M.N., Jiménez-Murcia S. Gambling during the COVID-19 crisis - a cause for concern? J. Addict. Med. 2020:e10–e12. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000690. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A., Jönsson C., Kenttä G. Psychological distress and problem gambling in elite athletes during COVID-19 restrictions-a web survey in top leagues of three sports during the pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:6693. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A., Åkesson G., Grudet C., Broman N. No apparent increase in treatment uptake for gambling disorder during ten months of the COVID-19 pandemic—analysis of a regional specialized treatment unit in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:1918. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Cherney L., Gainsbury S.M., Lubman D.I., Wood R.T., Blaszczynski A. Maintaining and losing control during internet gambling: a qualitative study of gamblers’ experiences. New Media Soc. 2015;17:1075–1095. doi: 10.1177/1461444814521140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holtgraves T. Evaluating the problem gambling severity index. J. Gambl. Stud. 2008;25:105. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt K., et al. Protocol for a mixed-method investigation of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and gambling practices, experiences and marketing in the UK: the “Betting and Gaming COVID-19 Impact Study”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:8449. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Murcia S., Fernández-Aranda F., Granero R., Menchón J.M. Gambling in Spain: update on experience, research and policy: gambling in Spain. Addiction. 2013;109:1595–1601. doi: 10.1111/add.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Hwang I., LaBrie R., Petukhova M., Sampson N.A., Winters K.C., Shaffer H.J. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 2008;38:1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/s0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D.L., Delfabbro P.H., Billieux J., Potenza M.N. Problematic online gaming and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Behav. Addict. 2020 doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn D.A., Shaffer H.J. Gambling and the health of the public: adopting a public health perspective. J. Gambl. Stud. 1999;15(4):289–365. doi: 10.1023/a:1023005115932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn D., Gibbins R., Azmier J. Framing public policy towards a public health paradigm for gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 2003;19(2):235–256. doi: 10.1023/a:1023685416816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langham E., Thorne H., Browne M., Donaldson P., Rose J., Rockloff M. Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:80. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner P., Forsström D., Jonsson J., Berman A.H., Carlbring P. Transitioning between online gambling modalities and decrease in Total gambling activity, but no indication of increase in problematic online gambling intensity during the first phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden: a time series forecast study. Front. Public Health. 2020;8:554542. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.554542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischer S., Steffen A., Schwarz J., Mathys J. The influence of lockdown on the gambling pattern of Swiss casinos players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:1973. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerlian C., Derevensky J., Gupta R. Youth gambling problems: a public health perspective. Health Promot. Int. 2005;20(1):69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Yuen N., Bursby R. Are all bets off? The reopening of casinos, bingo halls, and other gambling establishments in post-lockdown UK. Gaming Law Rev. 2020;24:559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Olason D.T., Hayer T., Brosowski T., Meyer G. Gambling in the mist of economic crisis: results from three national prevalence studies from Iceland. J. Gambl. Stud. 2015;31:759–774. doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Roberts H., Sowden A., Patticrew M., Arai L., Rodgers M., Britten N., Roen K., Duffy S. 2006. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Potenza M.N., Balodis I.M., Derevensky J., Grant J.E., Petry N.M., Verdejo-Garcia A., Yip S.W. Gambling disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2019;5:51. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price A. Online gambling in the midst of COVID-19: a Nexus of mental health concerns, substance use and financial stress. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer H.J., Korn D.A. Gambling and related mental disorders: a public health analysis. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2002;23(1):171–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharman S. Gambling in football: how much is too much? Manag. Sport Leis. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1811135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharman S., Roberts A., Bowden-Jones H., Strang J. Gambling in COVID-19 lockdown in the UK: depression, stress, and anxiety. Front. Psychiatry. 2021;12:621497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.621497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K.K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M.D.J., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S., Akl E.A., Chang C., McGowan J., Stewart L., Hartling L., Aldcroft A., Wilson M.G., Garritty C., Lewin S., Godfrey C.M., Macdonald M.T., Langlois E.V., Soares-Weiser K., Moriarty J., Clifford T., Tunçalp Ö., Straus S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018;169:467. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner N.E. COVID-19 and gambling in Ontario. J. Gambl. Issues. 2020;44 doi: 10.4309/jgi.2020.44.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schalkwyk M.C., Cassidy R., McKee M., Petticrew M. Gambling control: in support of a public health response to gambling. Lancet (London, England) 2019;393(10182):1680–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N.D. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173:61–62. doi: 10.7326/m20-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H. The emerging adults gambling survey: study protocol. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:102. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15969.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H., Reith G., Langham E., Rogers R.D. Gambling and public health: we need policy action to prevent harm. Bmj. 2019:365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H., et al. The impact of the initial Covid-19 lockdown upon regular sports bettors in Britain: findings from a cross-sectional online study. Addict. Behav. 2021;106876 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren G.W., Lofstedt Ragnar, Wardman Jamie K. COVID-19: the winter lockdown strategy in five European nations. J. Risk Res. 2021 doi: 10.1080/13669877.2021.1891802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yahya A.S., Khawaja S. Problem gambling during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prim Care Companion Cns Disord. 2020;22 doi: 10.4088/pcc.20com02690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]