Abstract

Background:

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are formed through nonenzymatic glycation of free amino groups in proteins or lipid. They are associated with inflammation and oxidative stress and their accumulation in the body is implicated in chronic disease morbidity and mortality. We examined the association between post-diagnosis dietary NƐ-carboxymethyl-lysine (CML)-AGE intake and mortality among women diagnosed with breast cancer (BC).

Methods:

Postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years were enrolled in the Women’s Health Initiative between 1993 and 1998 and followed up until death or censoring through March 2018. We included 2,023 women diagnosed with first primary invasive BC during follow-up who completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) after diagnosis. Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression models estimated adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of association between tertiles of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake and mortality risk from all-causes, BC, and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Results:

After a median 15.1 years of follow-up, 630 deaths from all-causes were reported (193 were BC-related and 129 were CVD-related). Post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake was associated with all-cause (HRT3vsT1: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.09–1.74), BC (HRT3vsT1: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.98–2.24) and CVD (HRT3vsT1: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.09–3.32) mortality.

Conclusions:

Higher intake of AGEs was associated with higher risk of major causes of mortality among postmenopausal women diagnosed with BC.

Impact:

Our findings suggest that dietary AGEs may contribute to the risk of mortality after BC diagnosis. Further prospective studies examining dietary AGEs in BC outcomes and intervention studies targeting dietary AGE reduction are needed to confirm our findings.

Keywords: Advanced glycation end-products, breast cancer, lifestyle, diet, mortality

Introduction

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are compounds that form naturally in the body but can also be consumed in the diet, largely as a result of high heat cooking of select foods.1 Specifically, AGEs are formed through irreversible nonenzymatic reactions of reducing sugars with proteins or lipids.1 High AGE levels are seen in hyperglycemic conditions and are linked to vascular complications in type II diabetes and the ageing process.2 Further accumulation of circulating AGEs occur through dietary intake of AGE-rich foods. A common mechanistic consequence of AGE accumulation is the activation of the transmembrane receptor for AGE (RAGE). AGE activation of the RAGE signaling cascade leads to persistent increases in oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. This promotes a tissue microenvironment conducive to the onset of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer, as well their associated complications and comorbidities.3–6 In addition, factors such as unhealthy diet, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity are positive risk factors for breast cancer (BC) and CVD morbidity and mortality7–9 and also are positively associated with AGEs.10,11

Compared to healthy women, higher serum AGE levels have been observed in women with BC and CVD, and RAGE is markedly over-expressed in cancerous as compared to non-cancerous breast tissue.12–14

In BC survivors, poor cardiovascular health and further aggravation of pre-existing disease may negatively impact survival outcomes.15,16 AGEs also have been suggested to inhibit the effects of tamoxifen treatment in hormone receptor positive BC.12 In addition to the naturally produced AGEs in the body, we hypothesize that further AGE accumulation from dietary exposure may represent a mechanism driving both cancer and cardiovascular disease and may be associated with their co-morbidity in cancer survivors thus reducing survival outcomes for women with BC. No study to date has examined dietary AGEs and mortality after BC diagnosis. Using data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), we examined the association between post-diagnosis intake of a priori-defined dietary AGEs assessed by food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among postmenopausal women diagnosed with invasive BC. The limited number of serum samples available for WHI participants at the time of diagnosis would not allow for sufficient power to use serum concentrations of AGEs in this data set. Whereas serum levels would reflect both endogenous and exogenous sources of AGEs, we focused instead on dietary intake of AGEs as a modifiable risk factor and potential target for future interventions. Specifically, we assessed dietary intake of NƐ-carboxymethyl-lysine (CML)-AGE, because it is a commonly measured form of AGE in previous epidemiologic studies.17–19

We hypothesized that higher CML-AGE intake after invasive BC diagnosis would be positively associated with mortality outcomes. We also examined if associations were stronger in hormone receptor positive BC and among low consumers of fruits and vegetables who may have reduced intake of phytochemicals and nutrients that could counter the pro-inflammatory and oxidative activity of AGEs. Finally, by incorporating pre-diagnosis dietary data, we explored whether contrasts in pre- and post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake were differentially associated with mortality risk.

Methods

Study population

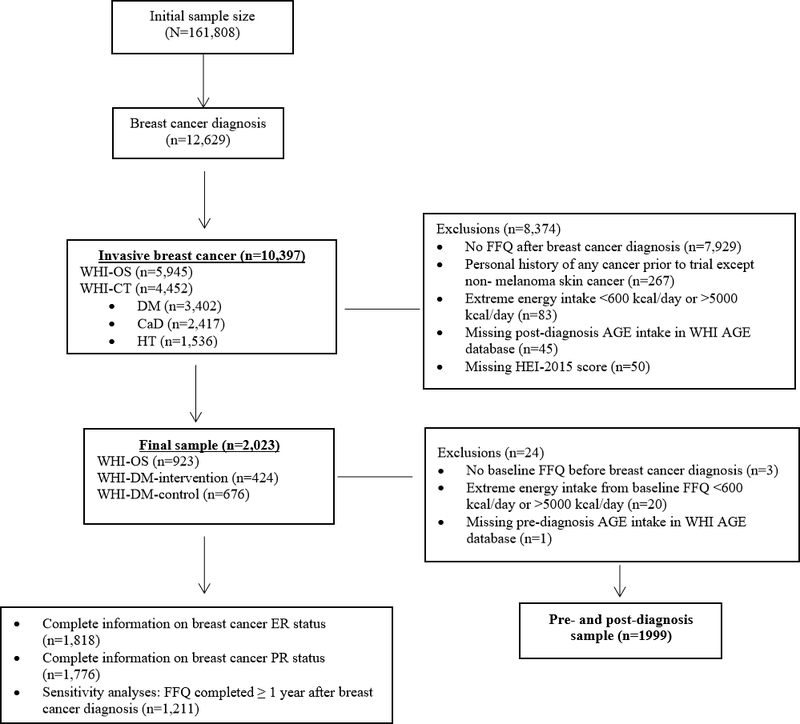

The WHI enrolled 161,808 postmenopausal women aged between 50 and 79 years from 1993 to 1998 across 40 clinical centers into one or more of three clinical trials (n=68,132) or an observational study (OS; n=93,676).20,21 The clinical trials included the hormone therapy (HT) trial, dietary modification (DM) trial, and the calcium plus vitamin D supplementation (CaD) trial. The current study used data only from the OS and DM trial of the WHI because FFQs which were used to calculate AGEs were completed multiple times during the course of the study. The methodology of the WHI have been previously published.21 Our study sample included participants who had a first primary diagnosis of invasive BC after enrollment in the WHI, completed a FFQ post-diagnosis, were cancer-free before or at WHI enrollment (except for non-melanoma skin cancer), had FFQ-assessed energy intakes between ≥600 kcal/day and ≤5000 kcal/day, and had FFQ records in the WHI dietary AGE database (Figure 1). Our analytical sample contained 2,023 women diagnosed with invasive BC as determined through self-report, followed by trained physician adjudication including review of medical records.22 In the analyses utilizing both pre- and post-diagnosis FFQ data, we further excluded participants with missing baseline (i.e., at time of WHI enrollment) FFQ or with baseline FFQ energy intakes <600 or >5000 kcal/day (n=24).

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Participants in the WHI.

Only women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer during follow-up and who completed a food frequency questionnaire after breast cancer diagnosis were included. Additional exclusion criteria are described for the main analyses, the joint analyses of pre- and post-diagnosis dietary intake, and the sensitivity analyses.

Data collection

Participants completed self-administered questionnaires at baseline that obtained information on age at screening for study eligibility, race/ethnicity, education, income and use of hormone therapy. Physical measurements on weight and height from which body mass index (BMI) was calculated were assessed during clinic visits and smoking and physical activity were assessed through personal habit questionnaires. Because BMI after BC diagnosis was missing in 178 participants, BMI at baseline was applied throughout these analyses as it was highly correlated with post-diagnosis BMI (r = 0.81). We also used physical activity and smoking status at baseline because these measures were not updated in the WHI-OS after BC diagnosis.

Usual dietary intake in the past three months was assessed through a self-administered FFQ.23 The FFQ consisted of three sections: (1) 122 foods or food groups soliciting information on usual dietary intake frequency and portion size, (2) four summary questions on usual intake of fruits and vegetables and added fat for comparison with the information obtained from the line items, and (3) 19 adjustment questions on nutritional content in food, preparation methods and added fats (Nutrition Data Systems for Research (NDSR®) version 2005). The nutrition database at the Nutrition Coordinating Center, University of Minnesota was used to derive the nutrients from the FFQ responses.23 FFQs were administered to participants in the WHI-DM at baseline and at one year of follow-up. Subsequently, one third of WHI-DM participants were randomly selected each year and FFQs were administered annually for 9 years. Participants in the WHI-OS were administered FFQs at baseline and after three years of follow-up.23 For pre-diagnosis dietary assessment we utilized the first FFQ administered at baseline, while the first FFQ that was completed after BC diagnosis (ranged between 1.1–6.3 years; average ± standard deviation was 1.5 ± 1.1 years) was utilized in the post-diagnosis dietary assessment.24

Exposure assessment

WHI investigators at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center assigned dietary AGE values to each food item on the FFQ using a published database.1,10 The database contains CML-AGE content of 549 selected foods commonly consumed in the northeastern metropolitan region of the United States.1 In the database, CML-AGE content was estimated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on monoclonal anti-CML antibody.1 CML-AGE values were matched to each food item on the FFQ. CML-AGE has been used as a measure of AGE exposure in previous epidemiological studies to estimate dietary AGE intake.18,19,25 CML-AGE intake was energy adjusted using the nutrient density method.26 Total post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake was categorized into tertiles with the lowest tertile serving as the referent in regression analysis. In the combined pre- and post-diagnosis assessment, CML-AGE intake was categorized into low and high intake categories using median cut points. Categories created include low pre- and low post-diagnosis, low pre- and high post-diagnosis, high pre- and low post-diagnosis, or high pre- and high post-diagnosis. Low pre- and low post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake served as the referent in regression analysis.

Covariate assessment

Potential confounders were identified through a literature search on known or suspected factors implicated in BC survival.9,27,28 The factors identified include age at BC diagnosis; time from BC diagnosis to the closest subsequent FFQ (years); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white (NHW), black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, or Others); annual household income (missing/don’t know, <$20,000, $20,000-<$50,000, or ≥$50,000); education (missing, high school or less, some college, college or some postgraduate, or postgraduate); WHI study arm (WHI-OS, WHI-DM-intervention, or WHI-DM-control); BC stage (localized, regional, distant, or unknown); estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status [positive, negative, or other (borderline, ordered/results not available, or unknown)]; energy intake (kcal/day); alcohol intake (servings/week); red and processed meat (servings/day); healthy eating index (HEI)-2015 score; baseline BMI (kg/m2) (<18.5 or missing, 18.5-<25, 25-<30, or ≥30); baseline recreational physical activity such as walking, mild, moderate, and strenuous activity (MET-hours/week) (missing, 0, ≤3, 3.1–8.9, or ≥9); baseline HT use (never user/missing, past user, or current user); and baseline smoking status (missing, never, past smoker, or current smoker). Because of potential bias if missing covariate data were not missing at random, we included separate categories for missing for physical activity (missing = 147), smoking (missing =31) and education (missing =14). For income, missing (n=76) and “don’t know” (n=30) responses were assumed to be similar and grouped together into one category. For HT use, only two person were missing HT use data and these were grouped with HR never users.

Outcome assessment

Our study outcomes included adjudicated death from all-causes, BC, and CVD. CVD deaths were defined as deaths from definite coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular, pulmonary embolism, possible coronary heart disease, other CVD, and unspecified CVD.29 Cause of death was ascertained through death certificates, medical records, hospitalization and autopsy reports.22 Unreported deaths and causes of death were ascertained through data linked to National Death Index of the National Center for Health Statistics.22

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses estimated means and percentages for continuous and categorical characteristics, respectively. The association between CML-AGE intake and risk of mortality from all-causeswas estimated using hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated from a Cox proportional hazards (PH) model. A competing risk analysis estimated risk of mortality from BC and CVD.30 Person-time was estimated from the date of diagnosis of invasive BC until death or censoring through March 2018. We adjusted for the time period between BC diagnosis and completion of the FFQ, when no participants were at risk of death (i.e., immortal time),31 by including a time-dependent covariate which stratified the status of the study outcome before and after completion of post-diagnosis FFQ.29,32 Adjustment models included a simple model that adjusted for age at BC diagnosis and energy intake. Multivariable Cox PH models included the covariates mentioned previously.

Our analyses were stratified by fruit and vegetable intake which was categorized into tertiles based on the frequency distribution (low intake: 0.3–3.38 servings/day, medium intake: 3.39–5.30 servings/day, or high intake: 5.31–14.29 servings/day). Associations were assessed for differences in the strength of the association by fruit and vegetable intake level. We also stratified our analyses by tumor hormone receptor status (ER, PR, and ER/PR combinations) and assessed for potential interaction with CML-AGE intake by including a multiplicative interaction term in the models. Because dietary changes may occur in the first year after BC diagnosis, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricting the sample to 1,211 women who completed a FFQ at least one year after BC diagnosis. Women enrolled in the WHI-DM intervention arm may have a healthier diet quality thus further analyses were restricted to 1) women enrolled in only the WHI-OS (n=923), and 2) WHI-OS and control arm of the WHI-DM (n=1,599).

PH assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residual test.33 For covariates violating PH assumption, we fitted stratified Cox PH models for categorical covariates (BMI) and time dependent Cox PH models for continuous covariates (age at BC diagnosis and intakes of alcohol and red and processed meat). P values for trend were calculated by modeling CML-AGE as a continuous variable. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and statistical significance was set at α=0.05.

Results

After a median follow-up time of 15.1 years, 630 deaths from all-causes were reported, from which 193 were BC-specific and 129 were CVD-related deaths. The average daily post-diagnosis CML-AGE consumption was 6,659 ± 2309 kilounits (kU)/1000 kcal and ranged from 830 kU/1000 kcal to 19,420 kU/1000 kcal. Compared to women in the lowest tertile of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake, women in the highest tertile had higher reported daily energy intake and red and processed meat intake, were more likely to be younger at BC diagnosis, obese, current smokers, physically inactive, and more likely to be diagnosed with PR-, regional (locally advanced), or distant BC (Table 1). Women in the highest tertile of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake had lower intake of fruits and vegetables and were least likely to be current HT users, have a college education or higher, or have a higher income.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by tertiles of post-diagnosis CML-AGE (kU/1000 kcal) intake

| Tertile 1 (n=674) | Tertile 2 (n=675) | Tertile 3 (n=674) | |

|

| |||

| CML-AGE, kU/1000 kcal | < 5549 | 5549–7311 | >7311 |

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|

| |||

| Years from enrollment to BC diagnosis | 2.5 (1.8) | 2.8 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) |

|

| |||

| Years from BC diagnosis to FFQ | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.1) |

|

| |||

| Total energy intake, kcal/day | 1477.5 (501.6) | 1568.6 (562.2) | 1578.5 (615.9) |

|

| |||

| Alcohol, servings/week | 2.5 (6.0) | 1.9 (3.4) | 2.1 (3.8) |

|

| |||

| Red and processed meat, servings/day | 0.5 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.6) |

|

| |||

| Daily fruit and vegetable intake, portion/day | 5.4 (2.4) | 4.7 (2.2) | 3.8 (1.9) |

|

| |||

| Total HEI-2015 score | 72.9 (8.8) | 68.5 (9.2) | 62.3 (8.6) |

|

| |||

| Age at BC diagnosis, year | 67.4 (7.1) | 66.6 (6.8) | 66.3 (7.1) |

|

| |||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| |||

| WHI study arm | |||

| WHI-OS | 348 (51.6) | 318 (47.1) | 257 (38.1) |

| WHI-DM-intervention | 194 (28.8) | 140 (20.7) | 90 (13.4) |

| WHI-DM- control | 132 (19.6) | 217 (32.2) | 327 (48.5) |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 622 (92.2) | 623 (92.3) | 573 (85.0) |

| Black or African American | 26 (3.9) | 28 (4.2) | 61 (9.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 (2.1) | 14 (2.1) | 24 (3.6) |

| Others | 12 (1.8) | 10 (1.5) | 16 (2.4) |

|

| |||

| BMI at enrollment (kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 or missing | 7 (1.0) | 4 (0.6) | 12 (1.8) |

| 18.5–<25 | 264 (39.2) | 235 (34.8) | 159 (23.6) |

| 25–<30 | 232 (34.4) | 219 (32.4) | 233 (34.6) |

| ≥30 | 171 (25.4) | 217 (32.2) | 270 (40.1) |

|

| |||

| Physical activity at enrollment, MET-hours/week | |||

| Missing | 35 (5.2) | 53 (7.9) | 59 (8.8) |

| 0 | 87 (12.9) | 85 (12.6) | 127 (18.8) |

| ≤3 | 70 (10.4) | 82 (12.2) | 90 (13.4) |

| 3.1–8.9 | 154 (22.9) | 142 (21.0) | 145 (21.5) |

| ≥9 | 328 (48.7) | 313 (46.4) | 253 (37.5) |

|

| |||

| Income | |||

| Missing or don’t know | 32 (4.8) | 31 (4.6) | 43 (6.4) |

| <$20,000 | 80 (11.9) | 73 (10.8) | 86 (12.8) |

| $20,000–<$50,000 | 296 (43.9) | 285 (42.2) | 286 (42.4) |

| ≥$50,000 | 266 (39.5) | 286 (42.4) | 259 (38.4) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| Missing | 7 (1.0) | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.5) |

| High school or less | 107 (15.9) | 102 (15.1) | 123 (18.3) |

| Some college | 233 (34.6) | 247 (36.6) | 274 (40.7) |

| College or some postgraduate | 193 (28.6) | 178 (26.4) | 159 (23.6) |

| Postgraduate | 134 (19.9) | 144 (21.3) | 115 (17.1) |

|

| |||

| Cause of death | |||

| No death | 479 (71.1) | 473 (70.1) | 441 (65.4) |

| BC death | 60 (8.9) | 52 (7.7) | 81 (12.0) |

| CVD death | 35 (5.2) | 46 (6.8) | 48 (7.1) |

| Death from other causes | 100 (14.8) | 104 (15.4) | 104 (15.4) |

|

| |||

| Cancer stage | |||

| Localized | 514 (76.3) | 515 (76.3) | 494 (73.3) |

| Regional | 151 (22.4) | 147 (21.8) | 167 (24.8) |

| Distant | 3 (0.5) | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 6 (0.9) | 9 (1.3) | 6 (0.9) |

|

| |||

| Smoking status at enrollment | |||

| Missing | 6 (0.9) | 11 (1.6) | 14 (2.1) |

| Never | 339 (50.3) | 309 (45.8) | 314 (46.6) |

| Past smoker | 300 (44.5) | 319 (47.3) | 310 (46.0) |

| Current smoker | 29 (4.3) | 36 (5.3) | 36 (5.3) |

|

| |||

| ER status | |||

| Positive | 508 (75.4) | 525 (77.8) | 513 (76.1) |

| Negative | 94 (14.0) | 90 (13.3) | 88 (13.1) |

| Other | 72 (10.7) | 60 (8.9) | 73 (10.8) |

|

| |||

| PR status | |||

| Positive | 422 (62.6) | 438 (64.9) | 415 (61.6) |

| Negative | 165 (24.5) | 165 (24.4) | 171 (25.4) |

| Other | 87 (12.9) | 72 (10.7) | 88 (13.1) |

|

| |||

| HT use at enrollment | |||

| Never user or missing | 210 (31.2) | 231 (34.2) | 232 (34.4) |

| Past user | 88 (13.1) | 79 (11.7) | 95 (14.1) |

| Current user | 376 (55.8) | 365 (54.1) | 347 (51.5) |

The results showing HRs and 95% CIs for mortality risk across the tertiles of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake are presented in Table 2. In multivariable model 2, there was a higher risk for all-cause (HRT3VST1: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.06–1.66; ptrend=0.024), BC-specific (HRT3VST1: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.05–2.13; ptrend=0.098), and CVD-related (HRT3VST1: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.08–3.15; ptrend=0.354) mortality. The associations persisted after additional adjustment for red and processed meat intake (model 3) for all-cause mortality (HRT3VST1: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.09–1.74; ptrend=0.009), BC-specific mortality (HRT3VST1: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.98–2.24; ptrend=0.285), and CVD-related mortality (HRT3VST1: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.09–3.32; ptrend=0.381). In sensitivity analysis restricting the sample to 1,211 women who completed a FFQ at least one year after BC diagnosis, the results were similar for BC mortality. However, the associations between post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake and all-cause mortality (HRT3VST1: 1.19, 95% CI: 0.88–1.62; ptrend=0.09) and CVD mortality (HRT3VST1: 1.41, 95% CI: 0.69–2.90; ptrend=0.576) were attenuated and confidence intervals included the null (Supplementary Table S1). In analyses restricting the sample to include only participants in the WHI-OS and WHI-DM control arm, the results were similar to the main findings for all mortality outcomes (Supplementary Table S2). Among WHI-OS participants only the associations were similar, though the BC mortality association was attenuated (HRT3VST1: 1.35, 95% CI: 0.79–2.28; ptrend=0.264) (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality, BC-specific mortality, and CVD-related mortality by tertilesa of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake in women diagnosed with BC in the WHI

| HR (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of deaths | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | |

|

| ||||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| Tertile 1 | 195 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Tertile 2 | 202 | 1.09 (0.89–1.33) | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | 1.04 (0.85–1.29) |

| Tertile 3 | 233 | 1.50 (1.24–1.82) | 1.33 (1.06–1.66) | 1.37 (1.09–1.74) |

| P trend e | 630 | <0.0001 | 0.024 | 0.009 |

|

| ||||

| BC mortality | ||||

| Tertile 1 | 60 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Tertile 2 | 52 | 0.85(0.58–1.23) | 0.81 (0.55–1.20) | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) |

| Tertile 3 | 81 | 1.46 (1.04–2.05) | 1.55 (1.05–2.31) | 1.49 (0.98–2.24) |

| P trend e | 193 | 0.056 | 0.098 | 0.29 |

|

| ||||

| CVD mortality f | ||||

| Tertile 1 | 35 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Tertile 2 | 46 | 1.57 (1.00–2.46) | 1.56 (0.97–2.51) | 1.58 (0.98–2.55) |

| Tertile 3 | 48 | 2.06 (1.31–3.21) | 1.85 (1.08–3.15) | 1.91 (1.09–3.32) |

| P trend e | 129 | 0.028 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

Tertile cutpoints in kU/1000kcal: Tertile 1: <5549; Tertile 2: 5549–7311; Tertile 3: >7311

Adjusted for age at BC diagnosis and energy intake

Adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, energy intake, income, race/ethnicity, study arm, time from BC diagnosis to FFQ, education, physical activity, smoking status, BMI, ER status, PR status, BC stage, HT use, alcohol intake, HEI-2015 and covariate of time-dependent status before and after post-diagnosis FFQ

Adjusted for all covariates in c and dietary intake of red and processed meat

P value for trend estimated by modeling CML-AGE as a continuous variable

Adjusted for time-dependent age at BC diagnosis due to PH assumption violation

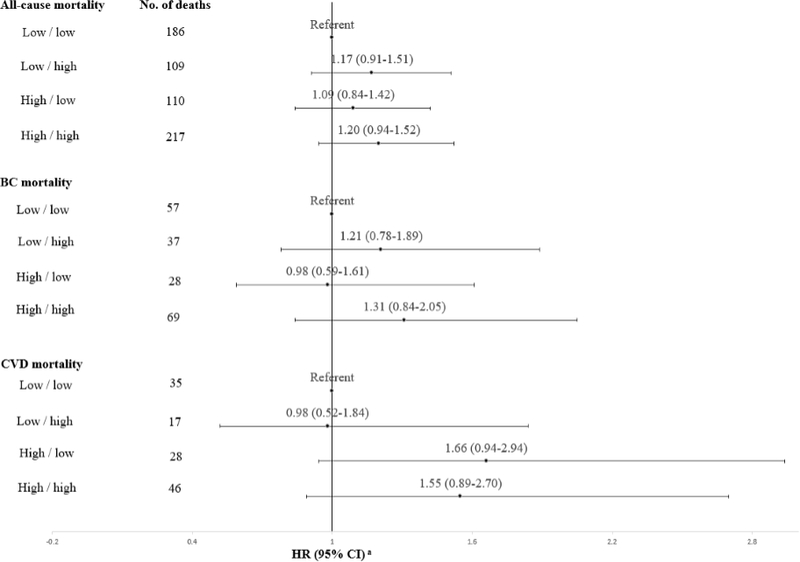

In the assessment of combined pre- and post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake, higher CML-AGE intake at both pre- and post-diagnosis was associated with modestly higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.94–1.52), BC mortality (HR: 1.31, 95%CI: 0.84–2.05), and CVD mortality (HR: 1.55, 95% CI: 0.89–2.70) compared to women with low pre- and post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake (Figure 2). Women who reported high post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake, regardless of whether their pre-diagnosis intake was low or high, had greater risk of death from all-causes and BC compared to women with low pre- and post-diagnosis intake, though confidence intervals included the null.

Figure 2.

HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality, BC-specific mortality, and CVD-related mortality by categories of pre-/post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake based on the median split

Note: Low/low, Low/high, High/low, and High/high refer to pre-diagnosis/post-diagnosis intakes of CML-AGE where low pre-diagnosis refers to <6752 kU/1000kcal, low post-diagnosis refers to <6362 kU/1000kcal, high pre-diagnosis refers to ≥6752 kU/1000kcal, and high post-diagnosis refers to ≥6362 kU/1000kcal intakes.

aAdjusted for age group at BC diagnosis, pre- and post-diagnosis energy intake, income, race/ethnicity, study arm, time from BC diagnosis to FFQ, education, physical activity, smoking status, BMI, ER status, PR status, BC stage, HT use, covariate of time-dependent status before and after postdiagnosis FFQ, and pre- and post-diagnosis alcohol intake, HEI-2015 and dietary intake of red and processed meat

In Table 3, higher risk for all-cause mortality was observed among all hormone receptor types and significant interaction was detected between CML-AGE and ER status (pinteraction= 0.042) but not for PR status (pinteraction= 0.12) or ER/PR combinations (pinteraction= 0.15). Associations tended to be stronger for hormone receptor negative subtypes [ER- (HRT3vsT1: 1.92, 95%CI: 1.01–3.62); PR- (HRT3vsT1: 1.79, 95%CI: 1.10–2.92); ER- and PR- (HRT3vsT1: 2.02, 95%CI: 1.01–4.05)]. In stratified analyses, positive associations between post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake and risk of BC-specific mortality were strongest among low and medium consumers of fruits and vegetables than among high consumers of fruits and vegetables (Supplementary Table S4). For all-cause and CVD-related mortality, higher intake of CML-AGE was associated with higher mortality risk across all strata of fruit and vegetable intake, though confidence intervals included the null.

Table 3.

HRs (95% CI) for all-cause mortality by tertilesa of post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake stratified by hormone receptor status in the WHI

| ER Status (n=1,818) | No. of deaths from any cause | HR (95% CI)b | Pinteractionc |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ER+ | |||

| Tertile 1 | 142 | Referent | |

| Tertile 2 | 148 | 0.99 (0.78–1.27) | |

| Tertile 3 | 171 | 1.36 (1.04–1.80) | |

|

| |||

| ER− | |||

| Tertile 1 | 33 | Referent | 0.042 |

| Tertile 2 | 32 | 0.78 (0.43–1.41) | |

| Tertile 3 | 40 | 1.92 (1.01–3.62) | |

|

| |||

| PR Status (n=1,776) | |||

|

| |||

| PR+ | |||

| Tertile 1 | 115 | Referent | |

| Tertile 2 | 122 | 0.98 (0.75–1.39) | |

| Tertile 3 | 139 | 1.31 (0.97–1.78) | |

|

| |||

| PR− | |||

| Tertile 1 | 56 | Referent | 0.12 |

| Tertile 2 | 54 | 1.03 (0.67–1.58) | |

| Tertile 3 | 66 | 1.79 (1.10–2.92) | |

|

| |||

| ER/PR combination | |||

|

| |||

| ER+/PR+ (n=1,578) | |||

| Tertile 1 | 145 | Referent | |

| Tertile 2 | 152 | 1.01 (0.79–1.28) | |

| Tertile 3 | 178 | 1.37 (1.05–1.80) | |

|

| |||

| ER− and PR− (n=234) | |||

| Tertile 1 | 28 | Referent | 0.15 |

| Tertile 2 | 28 | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | |

| Tertile 3 | 33 | 2.02 (1.01–4.05) | |

Tertile cutpoints in kU/1000kcal: Tertile 1: <5549; Tertile 2: 5549–7311; Tertile 3: >7311

Adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, energy intake, income, race/ethnicity, study arm, time from BC diagnosis to FFQ, education, physical activity, smoking status, BMI, BC stage, HT use, alcohol intake, HEI-2015, dietary intake of red and processed meat, and covariate of time-dependent status before and after post-diagnosis FFQ (for ER/PR combination model), ER status (for PR model) and PR status (for ER model).

Interaction between tertiles of CML-AGE and ER and PR status

Discussion

Higher dietary intake of CML-AGE, a modifiable dietary exposure, was associated with higher mortality risk from all-causes, BC, and CVD in postmenopausal women diagnosed with invasive BC among participants of the large, prospective WHI study. When examining both pre- and post-diagnosis dietary data, higher CML-AGE intake post-diagnosis was associated with higher mortality risk from all-causes and BC regardless of pre-diagnosis intake, suggesting that modification of intake post-diagnosis holds promise to improve outcomes after a BC diagnosis. Positive associations between post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake and mortality from all-causes were particularly strong for women with hormone receptor negative (ER- and PR-) BC.

There is a scarcity of literature on the association between AGEs and mortality among cancer survivors. Previous epidemiologic studies utilizing the same published AGE database for dietary assessment of CML-AGE are limited to associations with cancer incidence and reported that higher intake levels were associated with the risk of overall19 and invasive BC,25 and pancreatic cancer in men.18 Whereas our associations persisted even after adjustment for intake of red and processed meats, in previous analyses utilizing the NIH-American Association for Retired Persons Diet and Health Study, the increased risk of invasive BC was attenuated after adjustment for total fat and meat intakes.25 Stratified analyses showed positive associations for BC mortality with high post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake which appeared to be attenuated among high consumers of fruits and vegetables. In the WHI-DM trial, women randomized to a diet characterized by low fat and increased intake of fruits, vegetables and grains, reduced mortality risk was seen when compared to women in the usual diet comparison group,34 and this effect persisted even after long-term follow-up (median follow-up of 19.6 years).35 The high amounts of phytochemicals and fiber contained in fruits and vegetables may counter the pro-inflammatory and oxidative activity of AGEs and be protective of BC.36

While there has been limited research on post-diagnosis AGEs intake and survival after BC diagnosis, previous studies have examined post-diagnosis overall diet quality, for example by using the HEI-2015 which was developed based on the 2015–2020 U.S. Federal Dietary Guidelines for Americans, with higher scores indicating better diet quality.37 In previous studies, better diet quality (higher HEI-2015 score) was associated with a reduced risk of death from all-causes but not from BC-specific death in women diagnosed with early stage BC38 and invasive BC.24 Similarly, better adherence to the American Cancer Society dietary guidelines post-diagnosis was not associated with BC mortality, but was associated with modest decreased risk of death from other causes in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort.39 In our sample, there was a moderate negative correlation between HEI-2015 score and post-diagnosis CML-AGE intake (r: −0.45 p value: <0.0001). Reduced risk of CVD mortality in the WHI among women diagnosed with BC who consumed a more anti-inflammatory diet after diagnosis compared to those consuming a more pro-inflammatory diet using the dietary inflammatory index (DII) as a measure of inflammatory potential was previously reported.29 While AGEs are not included in the DII scoring algorithm, they have been associated with increased biomarkers of inflammation.40 Chronic diseases and adverse health outcomes have been linked to the Western diet.1,41–43 The Western diet is characterized by high intake of red and processed meat, fried foods, and products high in sugar and saturated fats, which are also major sources of AGEs.1 Findings from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) showed a positive relationship between the Western dietary pattern and risk of mortality from all-causes in women diagnosed with invasive BC.44 Similarly, higher consumption of grilled/barbecued and smoked meat (sources of AGEs) before and after BC diagnosis compared to low pre- and post-diagnosis intake was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality among women in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project.45

Accumulation of AGEs in tissues can promote protein structure damage thereby modifying mechanical and physiological function impacting carcinogenesis and inflammation. AGEs markedly stimulate RAGE activity and therefore increase release of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species that could induce DNA damage.46–50 RAGE is markedly expressed in breast tumors51 and increased RAGE expression enhances the proliferation and invasion of BC cells.14,52 High accumulation of CML in BC tissues53 and elevated serum CML levels were observed in women with BC.12 Clinical studies in humans suggest a link between high AGE plasma levels and CVD outcomes. AGEs can quench nitric oxide and increase production of endothelin favoring vasoconstriction and therefore promote vascular complications.54 These are some of the many potential links between AGEs and CVD that may explain the significant association with CVD-related mortality demonstrated herein. Plasma CML levels have been linked to the severity of cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary heart failure.55 Furthermore, serum AGE levels were associated with increased risk of mortality from all-causes and CVD in women aged 45 to 64 years who were followed for 18 years in a population registry in Finland.56

We utilized data from a large prospective study with adequate sample size, long follow-up period, and information on multiple potential confounders. Our study included only women with a post-diagnosis FFQ in the WHI which might introduce bias since women with poorer diet quality may have died or dropped out of the study before completing the FFQ after diagnosis. However, we compared baseline characteristics between participants included in our sample with those excluded who lacked information on post-diagnosis diet (Supplementary Table 5) and noted that average HEI-2015 score from baseline FFQ (pre-diagnosis) was actually lower among participants in our analytical sample as compared to those who were not included.

Because diet after BC diagnosis was assessed from the first FFQ completed after diagnosis, it is possible that changes to diet during the follow-up period may have occurred. In our sensitivity analyses, we excluded women with a post-diagnosis FFQ completed less than one year after diagnosis and the results were unchanged for BC-specific mortality. Of note, the associations for all-cause mortality and CVD mortality were attenuated and the confidence intervals included the null, which may be partially due to the smaller sample size and number of CVD-related deaths. Comprehensive information on types of treatment received such as chemotherapy could be a clinical predictor for cause-specific mortality. Though information on BC treatment was not included in our analyses, we controlled for BC stage and hormone receptor status, which might serve as an indicator of pharmacological treatment. In addition, we did not have information on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in our dataset. AGEs may increase inflammation and thus, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may modify the association between AGEs and mortality.

Based on the distribution of BMI in our study, it is likely that energy intake from diet was under-reported and FFQs have known measurement error.57,58 Since dietary information was obtained both before and after BC diagnosis in all subjects, measurement error that might have occurred from the self-reported FFQ is more likely to be non-differential.59 The database developed by Uribarri et al. that assessed CML-AGE content of over 500 foods and beverages using ELISA was used to estimate total CML-AGE intake.1 Some other analytical methods produced varying CML-AGE contents for certain foods but a standard approach to quantify AGEs is yet to be established.60 Thus, the true AGE content present in food may be under- or over-estimated.17,60 Other AGE databases measuring AGE contents of foods consumed in other populations have been developed. Some of these databases have included measurement of AGEs other than CML such as carboxyethyllysine (CEL). One database utilized the UPLC-MS/MS method to examine CML-AGE contents of 190 food items commonly consumed by the Dutch population.61 The Takeuchi et. al. database measured CML-AGE contents of 1,650 beverages and foods consumed in Japan using ELISA.62 More recently, an AGE database is being developed by researchers at the Dresden University of Technology and contains AGE contents measured in 537 food items.63 Previous studies reported moderate correlations between estimated dietary AGE intake and serum AGE levels,64 while one study averaging two assessments of serum CML measured by ELISA and taken 13 weeks apart reported no correlation between intake of foods considered high in dietary AGE and serum CML-AGE.65 Cooking methods utilizing high heat such as grilling or frying are major contributors to total AGE; the FFQ generally did not ascertain food preparation information thus limiting the precision in estimating this exposure. Apart from diet contributing to AGE levels in the body, endogenous production of AGE may contribute to the levels found in serum.1 Also, AGE metabolism may be influenced by the composition of the gut microbiome66,67 which may impact serum AGE levels. Thus far, the Uribarri et al. AGE database is the most frequently utilized in epidemiologic studies to estimate dietary AGE intake from FFQ responses,18,19,25 and thus enhances reproducibility and comparability of our results with other studies. We were unable to explore associations by race/ethnicity due to the small sample size among various racial/ethnic groups. Further studies utilizing large and racially diverse datasets are warranted to explore differential associations by race/ethnicity and BC hormone receptor status.

Higher intake of AGEs was associated with higher risk of major causes of mortality among women diagnosed with BC. Further prospective studies examining dietary AGEs in BC outcomes and intervention studies targeting dietary AGE reduction are needed to evaluate potential benefits on survival outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

For a list of all the investigators who have contributed to WHI science, please visit: https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/www-whi-org/wp-content/uploads/WHI-Investigator-Long-List.pdf

Financial support:

Omonefe O. Omofuma is funded by:

1. A Graduate Training in Disparities Research grant from Susan G. Komen (GTDR17500160; PI: S. Steck; Trainee: O. Omofuma)

2. A Support to Promote Advancement of Research and Creativity (SPARC) grant from the UofSC Office of the Vice President for Research.

Lindsay L. Peterson is funded by the:

1. American Cancer Society, (MRSG-18-199-01-NEC)

2. TREC Training Workshop, (R25CA203650)

David P. Turner is funded by the:

1. NIH/NCI, (U54CA210962)

2. NIH/NCI, (R21CA218929)

3. NIH, (R01CA245143)

Susan E. Steck is funded by:

1. A Graduate Training in Disparities Research grant from Susan G. Komen (GTDR17500160; PI: S. Steck)

The WHI program is funded by the:

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services contracts: HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure statement: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, et al. Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):911–16.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luevano-Contreras C, Chapman-Novakofski K, Luevano-Contreras C, Chapman-Novakofski K. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products and Aging. Nutrients. 2010;2(12):1247–1265. doi: 10.3390/nu2121247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramasamy R, Vannucci SJ, Yan SSD, Herold K, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Advanced glycation end products and RAGE: a common thread in aging, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Glycobiology. 2005;15(7):16R–28R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riehl A, Németh J, Angel P, Hess J. The receptor RAGE: Bridging inflammation and cancer. Cell Commun Signal CCS. 2009;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kierdorf K, Fritz G. RAGE regulation and signaling in inflammation and beyond. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94(1):55–68. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritz G RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36(12):625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dieterich M, Stubert J, Reimer T, Erickson N, Berling A. Influence of lifestyle factors on breast cancer risk. Breast Care Basel Switz. 2014;9(6):407–414. doi: 10.1159/000369571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttar HS, Li T, Ravi N. Prevention of cardiovascular diseases: Role of exercise, dietary interventions, obesity and smoking cessation. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2005;10(4):229–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Cancer Research Fund/ American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer

- 10.Uribarri J, del Castillo MD, de la Maza MP, et al. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products and Their Role in Health and Disease12. Adv Nutr. 2015;6(4):461–473. doi: 10.3945/an.115.008433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner DP. Advanced Glycation End-Products: A Biological Consequence of Lifestyle Contributing to Cancer Disparity. Cancer Res. 2015;75(10):1925–1929. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walter KR, Ford ME, Gregoski MJ, et al. Advanced glycation end products are elevated in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients, alter response to therapy, and can be targeted by lifestyle intervention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Published online October 27, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4992-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesarová P, Kalousová M, Trnková B, et al. Carbonyl and oxidative stress in patients with breast cancer--is there a relation to the stage of the disease? Neoplasma. 2007;54(3):219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nankali M, Karimi J, Goodarzi MT, et al. Increased Expression of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Products (RAGE) Is Associated with Advanced Breast Cancer Stage. Oncol Res Treat. 2016;39(10):622–628. doi: 10.1159/000449326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masoudkabir F, Sarrafzadegan N, Gotay C, et al. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: Evidence for shared disease pathways and pharmacologic prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Qadir H, Austin PC, Lee DS, et al. A Population-Based Study of Cardiovascular Mortality Following Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(1):88. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Ames JM, Smith RD, Baynes JW, Metz TO. A Perspective on the Maillard Reaction and the Analysis of Protein Glycation by Mass Spectrometry: Probing the Pathogenesis of Chronic Disease. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(2):754–769. doi: 10.1021/pr800858h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiao L, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Zimmerman TP, et al. Dietary consumption of advanced glycation end products and pancreatic cancer in the prospective NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(1):126–134. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.098061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omofuma OO, Turner DP, Peterson LL, Merchant AT, Zhang J, Steck SE. Dietary advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and risk of breast cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO). Cancer Prev Res Phila Pa. Published online March 13, 2020. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, et al. The women’s health initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9, Supplement):S18–S77. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00042-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curb JD, McTiernan A, Heckbert SR, et al. Outcomes ascertainment and adjudication methods in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13(9 Suppl):S122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement characteristics of the Women’s Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(3):178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George SM, Ballard-Barbash R, Shikany JM, et al. Better Postdiagnosis Diet Quality Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Death among Postmenopausal Women with Invasive Breast Cancer in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2014;23(4):575–583. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson LL, Park S, Park Y, Colditz GA, Anbardar N, Turner DP. Dietary advanced glycation end products and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. Cancer. 2020;126(11):2648–2657. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4):1220S–1228S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1220S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caleffi M, Fentiman IS, Birkhead BG. Factors at presentation influencing the prognosis in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1989;25(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(89)90050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seedhom AE, Kamal NN. Factors Affecting Survival of Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer in El-Minia Governorate, Egypt. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2(3):131–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng J, Tabung FK, Zhang J, et al. Association between Post-Cancer Diagnosis Dietary Inflammatory Potential and Mortality among Invasive Breast Cancer Survivors in the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomark. 2018;27(4):454–463. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine JP. Regression modeling of competing crude failure probabilities. Biostatistics. 2001;2(1):85–97. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/2.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lévesque LE, Hanley JA, Kezouh A, Suissa S. Problem of immortal time bias in cohort studies: example using statins for preventing progression of diabetes. BMJ. 2010;340:b5087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal P, Moshier E, Ru M, et al. Immortal Time Bias in Observational Studies of Time-to-Event Outcomes. Cancer Control J Moffitt Cancer Cent. 2018;25(1). doi: 10.1177/1073274818789355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoenfeld D Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69(1):239–241. doi: 10.1093/biomet/69.1.239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Anderson GL, et al. Low-Fat Dietary Pattern and Breast Cancer Mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(25):2919–2926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, Anderson GL, et al. Dietary Modification and Breast Cancer Mortality: Long-Term Follow-Up of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1419–1428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michels KB, Mohllajee AP, Roset-Bahmanyar E, Beehler GP, Moysich KB. Diet and breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(S12):2712–2749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(9):1591–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George SM, Irwin ML, Smith AW, et al. Postdiagnosis diet quality, the combination of diet quality and recreational physical activity, and prognosis after early-stage breast cancer. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2011;22(4):589–598. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9732-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, Shah R, et al. Pre- and postdiagnostic diet in relation to mortality among breast cancer survivors in the CPS-II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2016;27(11):1303–1314. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0802-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almajwal AM, Alam I, Abulmeaty M, Razak S, Pawelec G, Alam W. Intake of dietary advanced glycation end products influences inflammatory markers, immune phenotypes, and antiradical capacity of healthy elderly in a little-studied population. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8(2):1046–1057. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uribarri J, Cai W, Sandu O, Peppa M, Goldberg T, Vlassara H. Diet-derived advanced glycation end products are major contributors to the body’s AGE pool and induce inflammation in healthy subjects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:461–466. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uribarri J, Cai W, Peppa M, et al. Circulating Glycotoxins and Dietary Advanced Glycation Endproducts: Two Links to Inflammatory Response, Oxidative Stress, and Aging. J Gerontol Ser A. 2007;62(4):427–433. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vlassara H Advanced glycation in health and disease: role of the modern environment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:452–460. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroenke CH, Fung TT, Hu FB, Holmes MD. Dietary Patterns and Survival After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9295–9303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parada H, Steck SE, Bradshaw PT, et al. Grilled, Barbecued, and Smoked Meat Intake and Survival Following Breast Cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(6). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward MS, Fotheringham AK, Cooper ME, Forbes JM. Targeting advanced glycation endproducts and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13(4):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clarke RE, Dordevic AL, Tan SM, Ryan L, Coughlan MT. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products and Risk Factors for Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):125. doi: 10.3390/nu8030125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kellow NJ, Savige GS. Dietary advanced glycation end-product restriction for the attenuation of insulin resistance, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(3):239–248. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bansal S, Siddarth M, Chawla D, Banerjee BD, Madhu SV, Tripathi AK. Advanced glycation end products enhance reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generation in neutrophils in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;361(1–2):289–296. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1114-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guimarães ELM, Empsen C, Geerts A, van Grunsven LA. Advanced glycation end products induce production of reactive oxygen species via the activation of NADPH oxidase in murine hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2010;52(3):389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Logsdon CD, Fuentes MK, Huang EH, Arumugam T. RAGE and RAGE ligands in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7(8):777–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharaf H, Matou-Nasri S, Wang Q, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts increase proliferation, migration and invasion of the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis. 2015;1852(3):429–441. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nass N, Ignatov A, Andreas L, Weißenborn C, Kalinski T, Sel S. Accumulation of the advanced glycation end product carboxymethyl lysine in breast cancer is positively associated with estrogen receptor expression and unfavorable prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative cases. Histochem Cell Biol. 2017;147(5):625–634. doi: 10.1007/s00418-016-1534-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartog JWL, Voors AA, Bakker SJL, Smit AJ, Veldhuisen DJ van. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and heart failure: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(12):1146–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartog JWL, Voors AA, Schalkwijk CG, et al. Clinical and prognostic value of advanced glycation end-products in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(23):2879–2885. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kilhovd Bente K, Juutilainen Auni, Lehto Seppo, et al. High Serum Levels of Advanced Glycation End Products Predict Increased Coronary Heart Disease Mortality in Nondiabetic Women but not in Nondiabetic Men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(4):815–820. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000158380.44231.fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freedman LS, Commins JM, Moler JE, et al. Pooled results from 5 validation studies of dietary self-report instruments using recovery biomarkers for energy and protein intake. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(2):172–188. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prentice RL, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Huang Y, et al. Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(5):591–603. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freedman LS, Schatzkin A, Midthune D, Kipnis V. Dealing With Dietary Measurement Error in Nutritional Cohort Studies. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(14):1086–1092. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nowotny K, Schröter D, Schreiner M, Grune T. Dietary advanced glycation end products and their relevance for human health. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scheijen JLJM, Clevers E, Engelen L, et al. Analysis of advanced glycation endproducts in selected food items by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: Presentation of a dietary AGE database. Food Chem. 2016;190:1145–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeuchi M, Takino J, Furuno S, et al. Assessment of the Concentrations of Various Advanced Glycation End-Products in Beverages and Foods That Are Commonly Consumed in Japan. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0118652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.TUD - AGE Database. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://lemchem.file3.wcms.tu-dresden.de//index.php

- 64.Uribarri J, Peppa M, Cai W, et al. Dietary glycotoxins correlate with circulating advanced glycation end product levels in renal failure patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(3):532–538. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(03)00779-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Semba RD, Ang A, Talegawkar S, et al. Dietary intake associated with serum versus urinary carboxymethyl-lysine, a major advanced glycation end product, in adults: the Energetics Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(1):3–9. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seiquer I, Rubio LA, Peinado MJ, Delgado-Andrade C, Navarro MP. Maillard reaction products modulate gut microbiota composition in adolescents. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58(7):1552–1560. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snelson M, Coughlan MT. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products: Digestion, Metabolism and Modulation of Gut Microbial Ecology. Nutrients. 2019;11(2). doi: 10.3390/nu11020215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.