Abstract

Background

Hyponatremia due to endocrinopathies such as adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism has been reported in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). We determined the risk and predictors of hyponatremia and other electrolyte abnormalities in a ‘real-world’ sample of patients receiving ICIs to treat advanced malignancies.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study of all patients who received ICIs from a single cancer center between 2011 and 2018. Patients were followed for 12 months after initiation of ICIs or until death. Common Terminology for Cancer Adverse Events version 5.0 criteria were used to grade the severity of hyponatremia and other electrolyte abnormalities. The predictors of severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia were determined using a multivariable logistic regression model. The etiology of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia was determined by chart review.

Results

A total of 2458 patients were included. Their average age was 64 years [standard deviation (SD) 13], 58% were male and 90% were white. In the first year after starting ICIs, 62% experienced hyponatremia (sodium <134 mEq/L) and 136 (6%) experienced severe hyponatremia (<124 mEq/L). Severe hyponatremia occurred on average 164 days (SD 100) after drug initiation. Only nine cases of severe hyponatremia were due to endocrinopathies (0.3% overall incidence). Risk factors for severe hyponatremia included ipilimumab (a cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibitor) use, diuretic use and non-White race. Other severe electrolyte abnormalities were also commonly observed: severe hypokalemia (potassium <3.0 mEq/L) occurred in 6%, severe hyperkalemia (potassium ≥6.1 mEq/L) occurred in 0.6%, severe hypophosphatemia (phosphorus <2 mg/dL) occurred in 17% and severe hypocalcemia (corrected calcium <7.0 mg/dL) occurred in 0.2%.

Conclusions

Hyponatremia is common in cancer patients receiving ICIs. However, endocrinopathies are an uncommon cause of severe hyponatremia.

Keywords: electrolytes, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, hyponatremia, hypophysitis, immune checkpoint inhibitor

KEY LEARNING POINTS

What is already known about this subject?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can lead to autoimmune side effects.

Hyponatremia due to endocrinopathies such as adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism has been reported in patients receiving ICIs.

The risk of hyponatremia and other electrolyte disorders has never been reported in a ‘real-world’ population of patients receiving ICIs.

What this study adds?

Hyponatremia is very common in cancer patients receiving ICIs.

We found that immune-mediated endocrinopathies are an uncommon cause of severe hyponatremia, leading to severe hyponatremia in only 0.3% of patients.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

Given the widespread use of ICIs in patients with advanced malignancies, it is imperative that clinicians who manage these patients are aware of the high risk of hyponatremia and other electrolyte disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are monoclonal antibodies that block key negative regulators on T cells, unleashing anti-tumor T-cell responses that can lead to durable responses in cancers that were previously treatment refractory [1]. ICIs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat 18 different cancer types and their use is rapidly increasing [1–5]. Approved agents include those that target programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptor, including pembrolizumab, nivolumab and cemiplimab; PD-1 ligand (PDL-1), including atezolizumab, avelumab and durvalumab; or cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), including ipilimumab. Combination therapy with a PD-1 inhibitor and a CTLA-4 inhibitor is increasingly used, as it is superior to monotherapy in several cancers [6]. However, inhibition of immune checkpoints may disrupt immunologic homeostasis, unleashing autoreactive T cells that can attack host tissues and produce autoimmune side effects called immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which may affect any organ system, commonly involving the skin, intestinal tract, lungs, endocrine organs and kidney [7].

While acute interstitial nephritis causing acute kidney injury (AKI) is now a well-recognized side effect of ICIs, other important adverse events such as hyponatremia and other electrolyte abnormalities in patients receiving ICIs have not been well characterized [8–10]. Endocrinopathies such as hypothyroidism, adrenalitis and hypophysitis have been widely reported with ICIs and these can be associated with hyponatremia [11–13]. In a query of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Database (2011–15), Wanchoo et al. [14] found that hyponatremia was commonly reported with ICIs and another study looking at lung cancer patients [15] reported a higher incidence of hyponatremia with ICIs when compared with standard chemotherapy. However, a recent meta-analysis of patients receiving PD-1 inhibitors in clinical trials concluded that the pooled incidence of electrolyte abnormalities was only 1.2%, with a total of 52 events in ∼4300 patients [16]. We and others have also noted higher rates of irAEs from real-world data compared with those previously reported from clinical trials [8, 10]. In this study we aimed to define the risk of electrolyte abnormalities over the first year of ICI use and determine the risk factors and etiology of severe hyponatremia in a real-world population of patients receiving ICIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We included all patients who received ICIs at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center by reviewing oncology infusion records between May 2011 and December 2018. The follow-up period began at the date of the first ICI exposure. The drug classes included in the study were CTLA-4 inhibitors, PD-1 inhibitors, PDL-1 inhibitors and combination therapy (concurrent CTLA-4/PD-1). The cancer type and ICI start date were obtained from oncology infusion records. Clinical data including comorbidities, concomitant medication use and laboratory data were collected using the Partners Healthcare Research Patient Data Registry [7]. Exposure to anticancer agents associated with electrolyte abnormalities (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, vincristine, vinblastine, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide) within 6 months prior to ICI initiation or any time during the 1-year follow-up was also recorded. Baseline values for electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, calcium and phosphate were obtained from the laboratory results just prior to ICI initiation. Baseline creatinine was calculated by averaging all values obtained in the 3 months prior to ICI start. Excluded patients were those without electrolyte results within 3 months prior to starting ICI, those who did not have at least one follow-up laboratory value after the start date and those on dialysis. Laboratory data were collected for all patients for 12 months or until death, whichever occurred earlier. Comorbidities were defined by using the International Classification of Diseases 9th or 10th Revision codes at the ICI start date as we have previously described [8]. Medications included those active in the electronic health record at the date of beginning ICI. Diuretic use was defined as a prescription for a loop, thiazide or potassium-sparing diuretic.

Hyponatremia was defined as serum sodium ≤134 mEq/dL. The stages of severity were defined using the Common Terminology for Cancer Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 criteria: Grade 1, 130–134 mEq/L; Grade 2, 125–129 mEq/L; Grade 3, 120–124 mEq/L; and Grade 4, <120 mEq/L [17]. Severe hyponatremia was defined as serum sodium ≤124 mEq/L (Grade 3 or 4). Other electrolyte abnormalities were also graded using CTCAE version 5.0. Corrected calcium was calculated by using the formula 0.8 (four patient albumin levels) + measured calcium. Laboratory errors were defined as any Grade 3 or 4 abnormality that was not confirmed by a repeat test that was also out of the normal reference range. Baseline use of concomitant medications associated with electrolyte disorders was recorded, including the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), diuretics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs). In order to identify the etiology of severe (Grade 3 or 4) cases of hyponatremia, a detailed review of the electronic health record was performed. The etiology of severe hyponatremia was categorized as follows: hyponatremia due to a hemodynamic disturbance, including either hypovolemic hyponatremia due to volume depletion or hypervolemic hyponatremia due to cirrhosis or congestive heart failure; hyponatremia from syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), as defined by a lack of response to intravenous fluids, and elevated urinary sodium and osmolarity; hyponatremia due to endocrinopathy, confirmed by laboratory testing or brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating an increase in size/enhancement of the pituitary gland and/or infundibulum; hyponatremia associated with the patient’s terminal decline leading to hospice enrollment or death and hyponatremia from other/unknown causes.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were described using means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Univariable logistic regression was performed to evaluate for predictors of each electrolyte disorder. Multivariable logistic regression was performed using variables that were statistically significant with a P-value <0.10 in the univariable model. A stepwise selection model was performed to assess collinearity in the multivariable logistic regression models. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

The Institutional Review Board at Partners Healthcare System approved this study and waived the need for informed consent.

RESULTS

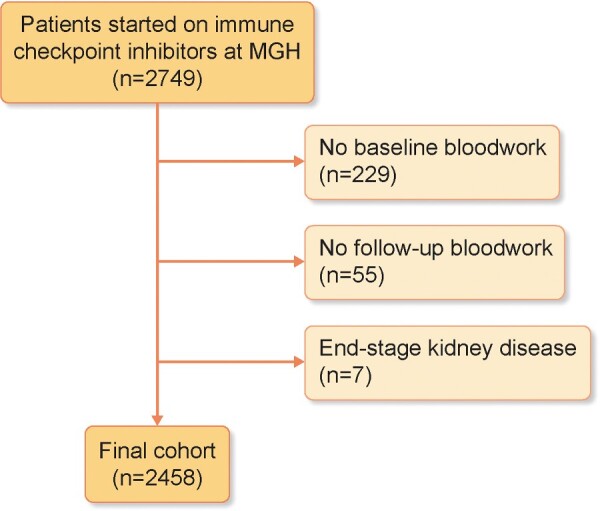

In our cancer center, 2749 patients were started on ICIs between 2011 and 2018. After applying the above exclusions, 2458 patients were included (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the included patients are listed in Table 1. The average age was 64 years (SD 13), 58% were male and 90% identified as White. The mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 81 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 19% of patients had an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline. The breakdown of malignancy types is shown in Table 1; thoracic malignancies were most common (31%), followed by melanoma (29%). PD-1 inhibitors were the most commonly used ICI class (71%), followed by CTLA-4 inhibitors (11%), PDL-1 inhibitors (9%) and PD-1/CTLA-4 combination therapy (9%). Diuretic, ACE/ARB, PPI and SSRI use was prevalent in 29, 25, 41 and 15% of patients, respectively. Thirteen percent of patients also received other anticancer agents known to be associated with electrolyte abnormalities. On average, patients in the included cohort had 21 (SD 15) metabolic panels measured in the first year after starting ICI.

FIGURE 1.

Patient flow. Flow sheet of patients on ICIs investigated for electrolyte abnormalities. Excluded patients were those without electrolyte results within 3 months prior to starting an ICI, those who did not have at least one follow-up laboratory value after the start date and those with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis. The final cohort included 2458 patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients who received ICIs

| Characteristics | Total |

|---|---|

| Patients, N | 2458 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64 (13) |

| Male, n (%) | 1422 (58) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 2208 (90) |

| Black | 47 (2) |

| Asian | 27 (1) |

| Hispanic | 80 (3) |

| Other/unknown | 96 (4) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2),amean (SD) | 81 (22) |

| Malignancy, n (%) | |

| Thoracic | 768 (31) |

| Melanoma | 721 (29) |

| GI | 276 (11) |

| Otherb | 693 (29) |

| ICI type, n (%) | |

| CTLA-4 | 263 (11) |

| PDL-1 | 225 (9) |

| PD-1 | 1742 (71) |

| Combined (CTLA-4 + PD-1) | 228 (9) |

| Comorbidities,cn (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 445 (18) |

| Hypertension | 1505 (61) |

| Coronary artery disease | 620 (25) |

| Cirrhosis | 87 (4) |

| CKD (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 463 (19) |

| Medications,dn (%) | |

| Diuretic use | 714 (29) |

| Loop diuretics | 410 (17) |

| Thiazides | 255 (10) |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 59 (2) |

| ACEi/ARB | 622 (25) |

| SSRI | 368 (15) |

| PPI | 1009 (41) |

| Anticancer agents associated with electrolyte abnormalitiese | 323 (13) |

eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.

Other cancers include genitourinary cancers, gynecological cancers, head and neck cancers, glioblastoma, breast cancers, lymphomas and leukemias.

Comorbidities were determined by the presence of International Classification of Diseases 9th or 10 Revision codes at the time of ICI administration.

Medications were determined by active prescriptions at the time of ICI administration.

Anticancer agents associated with electrolyte abnormalities included cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, vincristine, vinblastine, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide.

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Incidence of hyponatremia and other electrolyte abnormalities

The overall incidence of Grade 1 or higher hyponatremia (≤134 mEq/L) was 62% (n = 1519) within the first year after ICI therapy; 136 patients (6%) experienced Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia (≤124 mEq/L). Among other electrolytes, severe hypophosphatemia was very common, while severe hypocalcemia was uncommon (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of electrolyte abnormalities in patients receiving ICIs

| Electrolyte disorders | Values |

|---|---|

| Hyponatremia (N = 2456) | |

| Baseline sodium (mEq/L), mean (SD) | 137 (3) |

| Overall incidence, n (%) | 1519 (62) |

| Grade 1 (130–134 mEq/L) | 974 (40) |

| Grade 2 (125–129 mEq/L) | 409 (17) |

| Grade 3 (120–124 mEq/L) | 113 (5) |

| Grade 4 (<120 mEq/L) | 23 (1) |

| Hypokalemia (N = 2455) | |

| Baseline potassium (mEq/L), mean (SD) | 4 (1) |

| Overall incidence, n (%) | 677 (27) |

| Grades 1 and 2 (3.0–3.3 mEq/L)a | 544 (22) |

| Grade 3 (2.5–2.9 mEq/L) | 114 (5) |

| Grade 4 (<2.5 mEq/L) | 19 (1) |

| Hyperkalemia (N = 2455) | |

| Baseline potassium (mEq/L), mean (SD) | 4 (1) |

| Overall incidence, n (%) | 643 (26) |

| Grade 1 (5.1–5.5 mEq/L) | 453 (18) |

| Grade 2 (5.6–6.0 mEq/L) | 135 (5) |

| Grade 3 (6.1–7.0 mEq/L) | 47 (0.3) |

| Grade 4 (>7.0 mEq/L) | 8 (0.3) |

| Hypophosphatemia (N = 2208) | |

| Baseline phosphorous (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 3 (1) |

| Overall incidence, n (%) | 1106 (49) |

| Grades 1 and 2 (2.0–2.5 mg/dL) | 757 (38) |

| Grade 3 (1.0–1.9 mg/dL) | 329 (16) |

| Grade 4 (<1.0 mg/dL) | 20 (1) |

| Hypocalcemia (N = 2454) | |

| Baseline calcium (mg/dL), mean (SD) | 10 (1) |

| Overall incidence, n (%) | 213 (9) |

| Grade 1 (8.0–8.4 mg/dL) | 145 (6) |

| Grade 2 (7.0–7.9 mg/dL) | 63 (3) |

| Grade 3 (6.0–6.9 mg/dL)b | 5 (0.2) |

| Grade 4 (<6.0 mg/dL) | 0 (0) |

Severity of electrolyte abnormalities was graded per the CTCAE version 5.0 (2017). Baseline values were determined from the entire cohort. N for each electrolyte abnormality includes the total number of patients who had both baseline and at least one follow-up value determined.

In the CTCAE grading criteria, Grades 1 and 2 were differentiated based on symptoms and/or intervention, which were not included in the grading provided in this table. Only laboratory values were used for CTCAE grading in this table.

Grade 3 or 4 hypocalcemia was extremely rare, with an incidence of 0.2%, and chart review of each of the five cases of Grade 3 hypocalcemia did not uncover any plausible link to ICI use.

Predictors of severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia

In univariable analyses, age, gender, race, ICI class, malignancy type, cirrhosis, PPI use and diuretic use were associated with severe (Grade 3 or 4, serum sodium ≤124 mEq/L) hyponatremia. In the adjusted multivariable analyses, White race was associated with a lower risk of severe hyponatremia {adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.50 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32–0.80], P < 0.01}. Among the different ICI classes, being on anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy was associated with a higher risk of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia [aOR 2.69 (95% CI 1.42–5.09), P < 0.01, PD-1 inhibitors as the reference group]. There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of severe hyponatremia among patients receiving combination (CTLA-4/PD-1) therapy [aOR 1.72 (95% CI 0.97–3.05), P = 0.06] and any-grade hyponatremia was significantly more common in patients receiving combination therapy (Supplementary data, Table S1). Malignancy type was not associated with an increased risk of severe hyponatremia in the adjusted model. Finally, diuretic use, including loop, thiazide or potassium-sparing diuretics, was associated with a higher risk of severe hyponatremia [aOR 1.57 (95% CI 1.09–2.28), P = 0.02]. Diuretics use was also an important predictor of any-grade hyponatremia, as was ICI type, diabetes and concurrent use of other anticancer agents associated with hyponatremia. Predictors of any-grade (Grades 1–4) hyponatremia are shown in Supplementary data, Table S1 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of severe hyponatremia (Grade 3 or 4) in patients receiving ICIs

| Variables | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.97–0.10) | 0.03 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.04 |

| Male | 1.45 (1.01–2.09) | 0.04 | 1.35 (0.93–1.97) | 0.12 |

| White | 0.50 (0.32–0.80) | <0.01 | 0.52 (0.32–0.84) | <0.01 |

| ICI class | 0.01 | |||

| CTLA4 | 2.01 (1.24–3.23) | <0.01 | 2.69 (1.42–5.09) | <0.01 |

| Combined (CTLA4 + PD-1) | 1.71 (1.01–291) | 0.05 | 1.72 (0.97–3.05) | 0.06 |

| PD-L1 | 1.03 (0.54–1.96) | 0.94 | 1.04 (0.54–2.00) | 0.92 |

| Malignancy type | 0.02 | |||

| Thoracic | 1.01 (0.65–1.56) | 0.65 | 1.54 (0.86–2.75) | 0.15 |

| GI | 1.65 (0.98–2.77) | 0.98 | 1.63 (0.84–3.18) | 0.15 |

| Othera | 0.65 (0.39–1.07) | 0.39 | 0.99 (0.53–1.85) | 0.98 |

| Diabetes | 1.42 (0.94–2.14) | 0.09 | 1.34 (0.87–2.06) | 0.18 |

| Hypertension | 0.99 (0.70–1.41) | 0.96 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 2.60 (1.35–5.02) | <0.01 | 1.99 (0.96–4.13) | 0.06 |

| CKD (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.69 (0.42–1.23) | 0.14 | ||

| Diuretic use | 1.71 (1.20–2.44) | <0.01 | 1.57 (1.09–2.28) | 0.02 |

| Loop diuretics | 1.45 (0.95–2.20) | 0.09 | – | – |

| Thiazides | 1.34 (0.80–2.24) | 0.26 | – | – |

| Potassium-sparing diuretics | 1.60 (0.63–4.08) | 0.32 | – | – |

| ACE/ARB | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 0.13 | – | – |

| SSRIs | 0.75 (0.44–1.27) | 0.28 | – | – |

| PPI | 1.51 (1.07–2.14) | 0.02 | 1.33 (0.92–1.90) | 0.13 |

| Anticancer agents associated with hyponatremiab | 1.45 (0.91–2.29) | 0.11 | – | – |

Predictors that reached a P-value threshold of 0.10 were included in the multivariable analysis.

Other cancers include genitourinary, gynecological, head and neck, glioblastoma, breast, lymphomas and leukemias.

Anticancer agents associated with electrolyte abnormalities included cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, vincristine, vinblastine, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide.

CKD, chronic kidney disease.

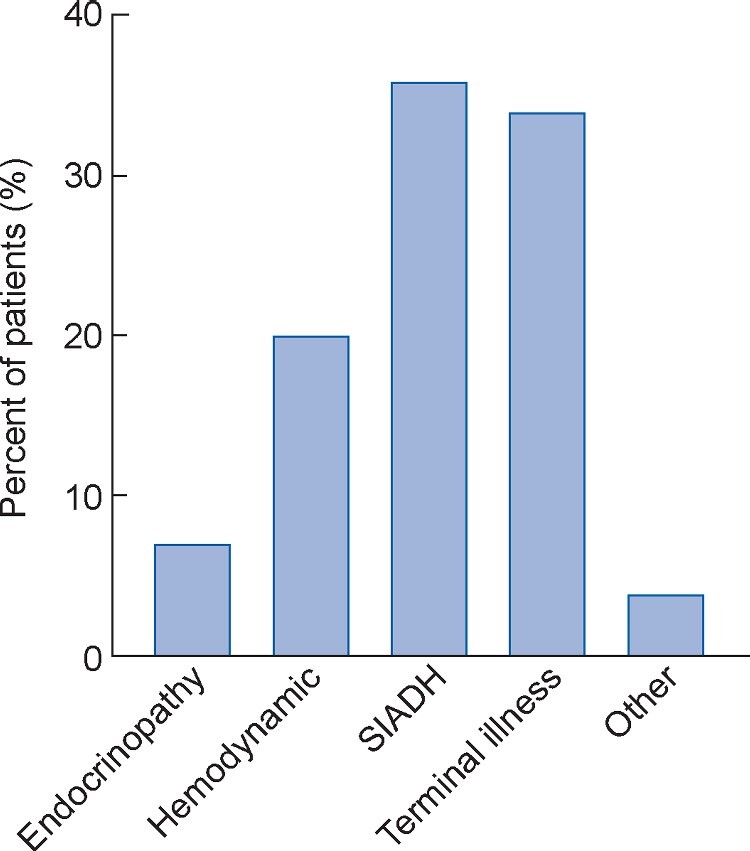

Etiology of severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia

Each case of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia was reviewed manually to determine the etiology; the breakdown of etiologies is shown in Figure 2. Endocrinopathies led to Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia in a total of nine cases (7% of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia and 0.3% of the overall cohort). Each of these patients had been evaluated by an endocrinologist. Adrenal insufficiency was secondary in all cases; eight patients had hypopituitarism, with abnormal levels of other pituitary hormones, and one patient had isolated low adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; Table 4). The average time from ICI initiation to diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency–induced hyponatremia was 164 days (SD 100). Of these nine patients, five also had immune-mediated thyroiditis. The other common causes of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia were SIADH (35%) and hyponatremia due to a hemodynamic disturbance (20%). Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia occurring at the time of a terminal decline (hospice enrollment or death) explained many cases of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia (34%), and only 4% were related to other/unknown causes (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Etiology of Grade 3 and 4 hyponatremia. Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia was present in 136 patients (6% of the overall cohort). SIADH was the most common etiology (36%), followed by hyponatremia occurring in the context of terminal illness leading to death or hospice enrollment (34%) and hyponatremia due to hemodynamic disturbances (20%). ICI-related autoimmune adrenal insufficiency was the cause of 7% of the cases of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia. About 4% of the cases (n = 5) were due to other causes [drug-induced (n = 2), polydipsia (n = 1)] or due to unknown causes (n = 2).

Table 4.

Case summaries of patients with hyponatremia caused by ICI-related adrenal insufficiency

| Age (years)/sex | Drug | Cancer | Baseline sodium (mEq/L) | Minimum sodium (mEq/L) | Days from ICI start | Hypophysitis on MRI | Cosyntropin test | ACTH | Other endocrine hormones | Resolution with steroids | Concomitant irAE | Other Grade 3 or 4 electrolyte abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70/F | Pembrolizumab | Thoracic | 135 | 124 | 148 | No | Normal | Low | Normal | Yes | None | None |

| 90/F | Ipilimumab | Melanoma | 140 | 121 | 155 | Yes | Failed | Not checked | ↓FSH, LH, TSH | Yes | Hypothyroidism | None |

| 65/M | Nivolumab | Thoracic | 134 | 123 | 175 | No | Failed | Low | ↓FSH, LH, prolactin, TSH | Partial | Hypothyroidism, diabetes, skin rash | Hypophosphatemia Grade 3 |

| 80/M | Ipilimumab | Melanoma | 137 | 123 | 70 | Yes | Failed | Low | ↓FSH, LH, testosterone, TSH | Yes | Hypothyroidism | Hypokalemia Grade 3 |

| 75/M | Ipilimumab | Melanoma | 131 | 121 | 72 | Yes | Failed | Low | ↓FSH, LH, testosterone | Yes | None | Hypophosphatemia Grade 3 |

| 50/M | Nivolumab | Thoracic | 138 | 118 | 309 | Yes | Failed | Low | ↓TSH | Yes | Hypothyroidism | Hypophosphatemia Grade 3 |

| 40/M | Ipilimumab | Melanoma | 137 | 123 | 29 | No | Not done | Low | ↓FSH, LH, testosterone, TSH (later) | Yes | None, hypothyroidism later | Hypophosphatemia Grade 3 |

| 80/M | Pembrolizumab | Melanoma | 138 | 122 | 347 | Not definitive | Failed | Low | ↓FSH, LH | Yes | None | None |

| 70/M | Ipilimumab and nivolumab | Melanoma | 140 | 124 | 175 | No | Failed | Low | ↓Testosterone (FSH, LH not checked) | Yes | Hypothyroidism | None |

Adjudication (primary/secondary) was made by an endocrine physician in all cases. Secondary: pituitary cause of adrenal insufficiency; primary: adrenalitis leading to adrenal insufficiency. Ages were rounded to the nearest 5 years. Grading of electrolyte abnormalities is per CTCAE version 5.0.

F, female; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

DISCUSSION

In a large real-world cohort of nearly 2500 consecutive patients with a variety of different cancer types, we found that hyponatremia was the most common electrolyte abnormality observed, occurring in 62% of patients, with 6% of patients developing severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia (serum sodium ≤124 mEq/L) within the first year after ICIs. This is the first and largest study to date that systematically determined the risk and etiology of severe hyponatremia after ICI use. We found that severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia attributed to immune-related endocrinopathies was rare, affecting only 0.3% of the cohort. We identified important risk factors for severe (Grade 3 or 4) hyponatremia, including ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) use, diuretic use and race. It is well known that certain irAEs, particularly hypophysitis, are more common in patients receiving CTLA-4 inhibitors compared with those receiving PD-1 or PDL-1 monotherapy [12, 18]. Additionally, in both the FDA reporting system and in the literature, most cases of hyponatremia and hypophysitis were reported in patients on ipilimumab [14]. Gastrointestinal (GI) malignancies were associated with a higher risk of any-grade hyponatremia (Supplementary data, Table S1) and there was a nonsignificant trend toward a higher risk of severe hyponatremia. This is likely due to the association with chronic liver disease or luminal disease that may affect oral intake and nutrient absorption.

Knowledge of hyponatremia associated with ICI is important. In general, in patients with cancer, hyponatremia negatively impacts cancer survival at all stages and its development can signal the presence of new comorbidities or toxicity, such as cardiomyopathy or advanced liver disease, or signal as a biomarker of advanced or unresponsive malignancy [19, 20]. In addition, hyponatremia has been shown to impact response to cancer therapy and can affect healthcare costs and utilization. The direct costs of treating hyponatremia in the USA on an annual basis have been estimated to range between $1 and 4 billion [21–23]. Early diagnosis and treatment of ICI-associated hyponatremia might help in mitigating some of the above concerns and outcomes associated with hyponatremia in cancer patients.

Importantly, we found substantially higher rates of other electrolyte abnormalities than other recent reports. A systematic review of clinical trial data found that in patients on PD-1 inhibitors, the pooled incidence of electrolyte abnormalities was only 1.2% (95% CI 0.7–2.1%) while another analysis summarizing clinical trial data reported an incidence of hyponatremia of 8.7% [15, 16]. This dramatic difference is likely due to several reasons. The prior studies only included trial participants, who are highly selected with normal or near-normal baseline organ function and closely monitored, making them less prone to adverse events in general. Additionally, patients whose cancer progresses will often be taken off of a trial and their electrolytes may no longer be included in study follow-up data, whereas our study followed patients for 1 year or to death. Because electrolyte abnormalities are common in patients with cancer, with the reported frequency of hyponatremia ranging from 4 to 47%, hypokalemia from 43 to 64%, hypocalcemia from 20 to 30% and hypophosphatemia from 20 to 30% in different cancers and settings, it can be hard to determine causality. This in turn could lead to underreporting in clinical trials, as some trials only report electrolyte abnormalities as adverse events if the investigators attributed it to the study drug [24–26]. In our study, we did not detect an association between ICIs and hypocalcemia that a recently published meta-analysis showed [16]. In fact, Grade 3 or 4 hypocalcemia was extremely rare, with an incidence of 0.2%, and a chart review of each case of severe hypocalcemia did not find a single instance of a plausible link to ICI use.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a predominantly White population sourced from a single cancer center, limiting generalizability. Practice patterns at our cancer center in terms of frequency of electrolyte monitoring may have influenced the detection rate. Additionally, it is possible that patients had laboratory studies performed at hospitals outside our healthcare network, resulting in an underestimation of the frequency of electrolyte abnormalities. We only included patients who had at least one metabolic panel measured in the 12-month follow-up period to ensure that patients getting the majority of their care outside our healthcare system were not included in the analysis. Furthermore, on average, our cohort had 21 metabolic panel measurements in the 12 months after starting ICIs, suggesting they were followed closely. Retrospective data collection led to limited clinical phenotyping of some cases of Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia and hypocalcemia; we relied on the available laboratory data and clinical evaluation at the time of the event. All cases of endocrinopathies leading to Grade 3 or 4 hyponatremia had been evaluated by an endocrinologist at the time of diagnosis, strengthening the validity of this diagnosis group. However, it is possible that endocrinopathies were underdiagnosed in patients who did not undergo a full workup, as they can present similarly to SIADH; the uncertainty of this diagnosis group is a limitation. We used the first ICI regimen administered and did not account for sequential therapy, which may have occurred if patients were switched from one ICI regimen to another. Additionally, we did not take into account the dose or total number of ICI doses patients received, duration of therapy nor dose response of ICI on the risk of electrolyte abnormalities. The dose/exposure–toxicity relationship is not well understood, but a large meta-analysis conducted with anti-PD/PD-L1 found no relationship between irAEs and dose of ICI agent [27]. Given the unique mechanism of action and prolonged duration of immunologic activity of even a single dose of an ICI (up to 1 year), we evaluated all electrolyte abnormalities within 1 year of the start date regardless of the duration of treatment [28].

In conclusion, hyponatremia is very common in patients receiving ICIs; however, immune-related causes of severe hyponatremia were uncommon. Given the widespread use of these drugs in patients with advanced malignancies, it is imperative that clinicians who manage these patients are aware of the high risk of these abnormalities; a focused workup is recommended to establish whether hyponatremia may be immune mediated or related to another cause, because if left uncorrected it could lead to serious consequences. Also, because we found that severe hypophosphatemia is also common, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines should consider recommending routine phosphate monitoring after ICI. Additional research is required to establish the ideal screening protocol and mechanisms driving electrolyte abnormalities in patients on ICIs.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ndt online.

FUNDING

M.E.S. is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (K23 DK117014).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

K.D.J. serves as a consultant for Astex Pharmaceuticals and Natera. L.Z. serves as a consultant for Merck. The other authors have no disclosures. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Ribas A, Wolchok JD.. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018; 359: 1350–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JRet al. Five-year survival and correlates among patients with advanced melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, or non-small cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. JAMA Oncol 2019; 5: 1411–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolchok JD. PD-1 blockers. Cell 2015; 162: 937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marquart J, Chen EY, Prasad V.. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who benefit from genome-driven oncology. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 1093–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haslam A, Gill J, Prasad V.. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e200423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez Ret al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD.. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seethapathy H, Zhao S, Chute DFet al. The incidence, causes, and risk factors of acute kidney injury in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 14: 1692–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cortazar FB, Kibbelaar ZA, Glezerman IGet al. Clinical features and outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated AKI: a multicenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31: 435–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cortazar FB, Marrone KA, Troxell MLet al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 638–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tan MH, Iyengar R, Mizokami-Stout Ket al. Spectrum of immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced endocrinopathies in cancer patients: a scoping review of case reports. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2019; 5: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barroso-Sousa R, Barry WT, Garrido-Castro ACet al. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 173–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhai Y, Ye X, Hu Fet al. Endocrine toxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a real-world study leveraging US food and drug administration adverse events reporting system. J Immunother Cancer 2019; 7: 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wanchoo R, Karam S, Uppal NNet al. Adverse renal effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a narrative review. Am J Nephrol 2017; 45: 160–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cantini L, Merloni F, Rinaldi Set al. Electrolyte disorders in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune check-point inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020; 151: 102974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manohar S, Kompotiatis P, Thongprayoon Cet al. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor treatment is associated with acute kidney injury and hypocalcemia: meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019; 34: 108–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2017. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf

- 18. Faje A, Reynolds K, Zubiri Let al. Hypophysitis secondary to nivolumab and pembrolizumab is a clinical entity distinct from ipilimumab-associated hypophysitis. Eur J Endocrinol 2019; 181: 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Osterlind K, Andersen PK.. Prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer: multivariate model based on 778 patients treated with chemotherapy with or without irradiation. Cancer Res 1986; 46: 4189–4194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rawson NS, Peto J.. An overview of prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer. A report from the Subcommittee for the Management of Lung Cancer of the United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Br J Cancer 1990; 61: 597–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waikar SS, Mount DB, Curhan GC.. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am J Med 2009; 122: 857–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doshi KH, Shriyan B, Nookala MKet al. Prognostic significance of pretreatment sodium levels in patients of nonsmall cell lung cancer treated with pemetrexed-platinum doublet chemotherapy. J Can Res Ther 2018; 14: 1049–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boscoe A, Paramore C, Verbalis JG.. Cost of illness of hyponatremia in the United States. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006; 4: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosner MH, Dalkin AC.. Electrolyte disorders associated with cancer. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014; 21: 7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shirali AC. Chapter 5. Electrolyte and Acid–Base Disorders in Malignancy. Onco-nephrology core curriculum. Washington, DC:American Society of Nephrology, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Y, Chen X, Shen Zet al. Electrolyte and acid-base disorders in cancer patients and its impact on clinical outcomes: evidence from a real-world study in China. Ren Fail 2020; 42: 234–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang PF, Chen Y, Song SYet al. Immune-related adverse events associated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment for malignancies: a meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 2017; 8: 730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner Iet al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3167–3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.