Abstract

Objectives

Our study aimed to calculate the prevalence and estimate the direct health care costs of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and test if trends in the prevalence and direct health care costs of IBD increased over two decades in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective population-based cohort study using administrative health data of Saskatchewan between 1999/2000 and 2016/2017 fiscal years. A validated case definition was used to identify prevalent IBD cases. Direct health care costs were estimated in 2013/2014 Canadian dollars. Generalized linear models with generalized estimating equations tested the trend. Annual prevalence rates and direct health care costs were estimated along with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Results

In 2016/2017, 6468 IBD cases were observed in our cohort; Crohn’s disease: 3663 (56.6%), ulcerative colitis: 2805 (43.4%). The prevalence of IBD increased from 341/100,000 (95%CI 340 to 341) in 1999/2000 to 664/100,000 (95%CI 663 to 665) population in 2016/2017, resulting in a 3.3% (95%CI 2.4 to 4.3) average annual increase. The estimated average health care cost for each IBD patient increased from $1879 (95%CI 1686 to 2093) in 1999/2000 to $7185 (95%CI 6733 to 7668) in 2016/2017, corresponding to an average annual increase of 9.5% (95%CI 8.9 to 10.1).

Conclusions

Our results provide relevant information and analysis on the burden of IBD in Saskatchewan. The evidence of the constant increasing prevalence and health care cost trends of IBD needs to be recognized by health care decision-makers to promote cost-effective health care policies at provincial and national levels and respond to the needs of patients living with IBD.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Direct health care costs, Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Prevalence

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC?

Predictions have reported increasing prevalence rates of IBD in Canada.

Hospitalizations and surgeries have traditionally been the major cost drivers for IBD direct health care costs.

No studies have evaluated the prevalence and direct annual costs trends of IBD in Saskatchewan.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

Our study observed a higher prevalence rate of IBD in comparison to previously forecasted rates in Saskatchewan.

Prescription medication accounted for about 90% of IBD direct health care costs in Saskatchewan.

The total direct health care costs of IBD increased more than six-fold from 7.8 million CAD in 1999/2000 to 50.9 million CAD in 2016/2017 FY in Saskatchewan.

Per patient average total annual costs of IBD increased from 1879 Canadian dollars (CAD) in 1999/2000 to 7185 CAD in 2016/2017.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) (1,2). The prevalence of IBD is increasing globally (3). Studies have associated this rise with the western lifestyle, incurability of the disease and low disease mortality rate (4–6). The regions with the highest prevalence of IBD include Europe and North America, specifically Canada (3,4,6). Today, the number of people living with IBD is estimated between 2.5 and 3 million in Europe, over 1 million in the United States, and 270,000 (7 out of 1000) in Canada (3,4,6,7).

In 2013, the annual direct health care cost for managing patients with IBD in Europe was 4.6 to 5.6 billion Euros (7), while U.S. and Canadian costs were, respectively, 14.6 billion U.S. dollars (USD) in 2014 and 1.2 billion Canadian dollars (CAD) in 2018 (8,9). The costs associated with IBD are mainly dominated by biologic medications (8,10), a treatment for IBD made from animal and human live cells (11). Before the introduction of biologic medications, hospitalizations and surgeries were the major cost drivers of IBD (8,10). Today, biologic medications are the cost drivers of IBD-related direct health care costs (8). For instance, between 2010 and 2015, Canadian spending on immunobiologics increased two-fold at 2.2 billion CAD. This increase accounted for 10.3% of the Canadian pharmaceutical market share (8). IBD is a costly disease (6,8) with increasing prevalence and medication costs that could pose a substantial economic burden for the health care system.

In the mid-western province of Saskatchewan, detailed evidence on the prevalence and direct health care costs of IBD is limited and needed. Despite a recent Canadian study predicted a rise in the prevalence of IBD in Saskatchewan (4), there are no retrospective evaluations in Saskatchewan of the prevalence trends during the last decades. Also, there is data from Manitoba, Quebec and Alberta regarding the health care cost of IBD (8,12,13), which may not apply to Saskatchewan given that the pattern and trends might vary across provinces. Local evidence about the actual prevalence and direct health care costs estimates of IBD over time is needed to contribute to health care resources allocation and planning. This study aimed to (1) calculate the prevalence and estimate the direct health care costs of IBD among adults, and (2) test if the prevalence and direct health care costs of IBD increased over the past two decades in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

METHODS

Setting and Data Source

A retrospective population-based cohort study was completed utilizing administrative health databases for the mid-Western Canadian province of Saskatchewan, with a population of approximately 1.2 million (14). These data, accessed at the Saskatchewan Health Quality Council (HQC), contain health care information for persons with provincial health care coverage. Excluded are individuals for whom health coverage is provided by the federal government (e.g., members of the Canadian armed forces, inmates in national penitentiaries), who comprise ~1% of the total Saskatchewan population (14). The administrative data used in this study included the hospital discharge abstract database (DAD), medical services branch claims database (MSB), prescription drug plan database (PDP) and person health registration system (PHRS). The DAD captures information on inpatient hospitalizations, day surgeries and diagnostic procedures (including endoscopies) captured each time patients are discharged from acute health care facilities. The MSB records physicians’ fee-for-service billing claims submitted to the Ministry of Health for services provided to patients. Physicians whose payment is not on a fee-for-service basis (e.g., salary) report services through a ‘shadow billing’ claim (14). The PDP data contain information about all dispensed outpatient prescription medications irrespective of whether the costs for these medications were covered by the government, patients, private insurance companies or a third party. This database does not include information about over the counter and inpatient medications. The PHRS captures individual demographic information, such as age, sex, location of residence, as well as health care coverage start and end dates. Deterministic, anonymized linkage of Saskatchewan PHRS data to the other databases (DAD, MSB and PDP) was completed using encrypted identifiers. Linked data are kept on secure servers at the HQC. These databases contain health care coverage and health care utilization information for more than two decades for Saskatchewan residents.

Case Definition and Study Population

A validated algorithm was used to identify cases of IBD (15) between 1999/2000 and 2016/2017 fiscal years (FY), specifically from April 1, 1999, and March 31, 2017. This algorithm considered individuals as IBD cases if they had (a) five or more health care contacts with the diagnosis of IBD within two years of continuous health insurance coverage or (b) three or more contacts with the diagnosis of IBD with less than 2 years of health insurance coverage (15). The International Classification of Disease (ICD) diagnosis codes for CD (ICD-9 555.x and ICD-10-CA K50.xx) and UC (ICD-9 556.x and ICD-10-CA K51.xx) were used to identify IBD cases (15,16). This case definition was previously validated in Manitoba using self-administered questionnaires and chart reviews and had high sensitivity (74.4 to 89.2%) and specificity (89.8 to 93.7%) (15). Manitoba is a neighbouring province that has a similar population and comparable health care data to the province of Saskatchewan. We assume equivalent validity properties in the two provinces. This case definition has been adopted in several population-based studies that use administrative health data from Saskatchewan (16–18) and was identified as the most accurate IBD algorithm for adults in Canada (19).

Prevalent cases were defined as individuals aged 18 years and older who met the case definition between 1999/2000 and 2016/2017 FY. Prevalent cases were classified as CD or UC based on the most frequent diagnosis (16). The PHRS was used to determine the population at risk, defined as all individuals aged 18 years and older with provincial health insurance coverage at any point. The prevalence of IBD, CD and UC were calculated annually and stratified by sex and age groups. Individuals less than 18 years old were excluded from this study due to the limitations of applying a paediatric IBD case definition, given that patients in Saskatchewan were required to access paediatric gastroenterology care in neighbouring provinces for several years during the last decade.

Direct Health Care Cost of IBD

Our study adopted a costing approach used in recent Canadian studies (20,21). We used two approaches to generate a total cost for each prevalent case: macro costs, assigned to inpatient/ day surgery hospital costs, and micro costs, assigned to physician services and prescription medications.

In Canada, individual hospital cost data are not available. Hence, hospitalization costs are obtained using the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s (CIHI) cost per standard hospital stay (CSHS) and resource intensity weight (RIWs) (20,22). RIWs are case weights for case-mix groups (CMGs), to measure the intensity of resource use associated with different diagnostic and surgical procedures and demographic characteristics of individuals (20). The average RIW is equal to 1 (23). Each hospital inpatient record is assigned an RIW. Each day surgery is assigned a Day Procedure Group (DPG) created for surgical procedures without overnight stays (20). The mean RIW for an IBD admission might vary from 1 year to another due to methodological differences, although CIHI adopts a hospital costing approach which makes comparisons over time feasible (24). DPG clustering is done based on patient resource utilization and clinical episode similarities. The average cost for a patient’s hospitalization is then obtained by multiplying the provincial CSHS by the sum of the RIWs and DPGs (20). These costs do not reflect the specific cost of a patient’s hospitalization, but rather the average cost for patients who share similar hospital stays (23). The CSHS values used for this study are reported in Supplementary Appendix I.

Costs of prescription medication claims were estimated by summing the total expenses for dispensed outpatient IBD medications during the study period. IBD medications were defined as medication claims for UC or CD (i.e., immune modulator, biologics and 5-aminosalicylic acid therapies), which were captured using drug identification numbers (DINs). We constructed a list of DINs for immune modulators (i.e., azathioprine, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, mycophenolate and cyclosporine), biologics (i.e., infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and vedolizumab) and 5-aminosalicylic acid (i.e., mesalamine, olsalazine sodium and sulfasalazine).

Prices of medications are available in the online Saskatchewan Drug Formulary (https://formulary.drugplan.ehealthsask.ca/FormularyBooks).

To obtain IBD physician costs, we summed the costs of outpatient services provided by physicians in the province to diagnosed IBD patients during the study period. These costs were defined as those with the diagnosis of IBD (i.e., CD: ICD-9 555.x and UC: ICD-9 556.x). Hospital, prescription medication and physician costs were adjusted to 2013/2014 CAD, using the Saskatchewan consumer price index (25). The Saskatchewan Medical Association has online the fee schedules of physician services (see a sample at https://www.sma.sk.ca/105/sma-fee-guide.html).

Statistical Analysis

The prevalence and cost data were analyzed using generalized linear models with generalized estimating equations (GEEs), used to address for correlation in the data. The negative binomial distribution (selected based on the model fit assessment) (26) was used to model the prevalence of IBD, CD and UC. To assess the model fit, the ratio of the deviance to the degrees of freedom was used. We considered a model to have a good fit to the data when this ratio was closer to 1 (26). Covariates for the models of IBD prevalence were sex, FY and age group categorized as 18 to 29 (reference group), 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, and 60+ years old. The model offset was the natural logarithm of the Saskatchewan population at risk.

Using non-zero cost data, the gamma distribution was selected to model total annual direct health care costs of IBD, as well as the annual hospital, physician and prescription medication claim costs. Model covariates included age group, sex, fiscal year, diagnosis type (UC or CD) and comorbidity burden (determined using the Charlson comorbidity index) (27). We calculated the comorbidity index based on the diagnoses from hospital and physician claims one year before the index date (27), defined as the date of the earliest hospital or physician UC or CD diagnoses.

Separate models were fit for IBD hospitalization, medication, physician and total cost (defined as the sum of the three components). An exchangeable correlation structure of the GEEs (which assumes observations over time have the same correlation) accounted for dependence among the prevalence and cost observations over time. Changes in prevalence and direct health care cost over time were tested with a linear trend by including FY as a continuous predictor in the models. Prevalence and cost estimates along with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were reported. The significance level was α = 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using the GENMOD procedure of the Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Our study received ethical approval from the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Ethics Board (REB, BIO 91).

RESULTS

Prevalence of IBD

The number of diagnosed IBD cases in Saskatchewan increased from 2834 in 1999/2000 to 6468 in 2016/2017 FY. The characteristics of the IBD cases in the first and last years of our study period are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics for individuals meeting the IBD case definition in Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1999/2000 and 2016/2017 fiscal years

| Variable | 1999/2000 (n = 2834) | 2016/2017 (n = 6468) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | ||

| 18–29 | 521 (18.4) | 556 (8.6) |

| 30–39 | 689 (24.3) | 988 (15.3) |

| 40–49 | 785 (27.7) | 1076 (16.6) |

| 50–59 | 401 (14.1) | 1607 (24.9) |

| 60+ | 438 (15.5) | 2241 (34.6) |

| Disease type | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 1734 (61.2) | 3663 (56.6) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1100 (38.8) | 2805 (43.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1493 (52.7) | 3402 (52.6) |

| Male | 1341 (47.3) | 3066 (47.4) |

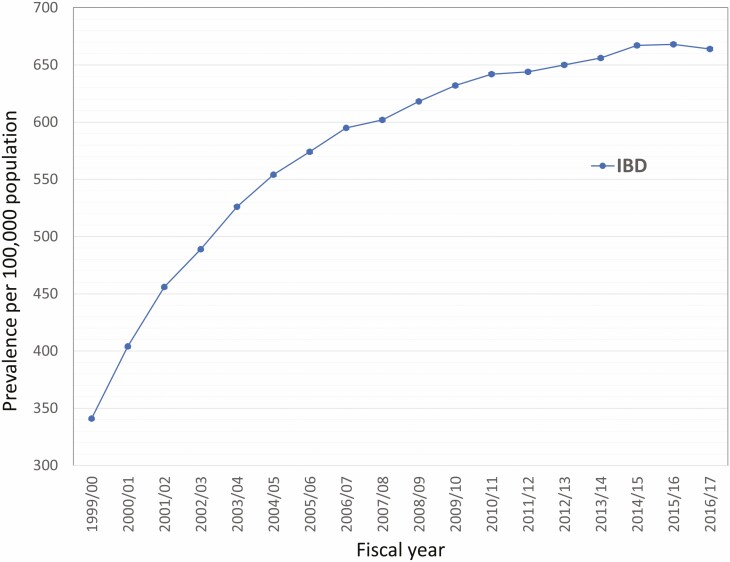

Based on our model results, the prevalence of IBD increased from 341/100,000 (95%CI 340 to 341) in 1999/2000 to 664/100,000 (95%CI 663 to 665) in 2016/2017, estimating a 3.3% (95%CI 2.4 to 4.3) annual average increase during the study period (Figure 1). Similarly, increasing trends in IBD prevalence were observed among females and males and by age groups; steeper increasing trends were observed in the oldest age groups (i.e., 50 to 59 and 60+ years old) than in younger age groups. The annual prevalence of IBD stratified by sex and age groups are reported in Supplementary Appendices II and III.

Figure 1.

Model-based prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Saskatchewan, Canada.

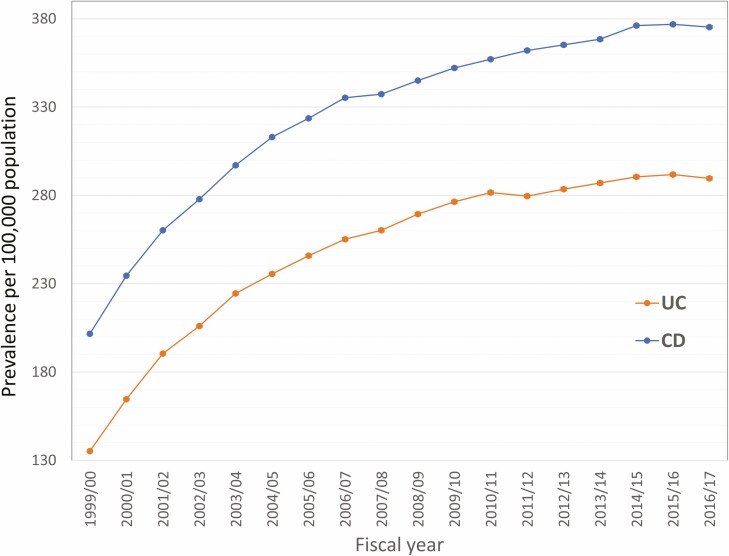

The prevalence of UC increased from 135/100,000 (95%CI 134 to 135) in 1999/2000 to 289/100,000 (95%CI 288 to 290) in 2016/2017. For CD, the prevalence increased from 201/100,000 (95%CI 201 to 202) in 1999/2000 to 375/100,000 (95%CI 375 to 376) in 2016/2017. Also, we identified statistically significant increasing linear trends in the prevalence of both UC (3.9% [95%CI 2.8 to 5.1]) and CD (3.1% [95%CI 2.2 to 3.9]) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model-based prevalence of ulcerative colitis (UC), and Crohn’s disease (CD) in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Direct Health Care Costs of IBD

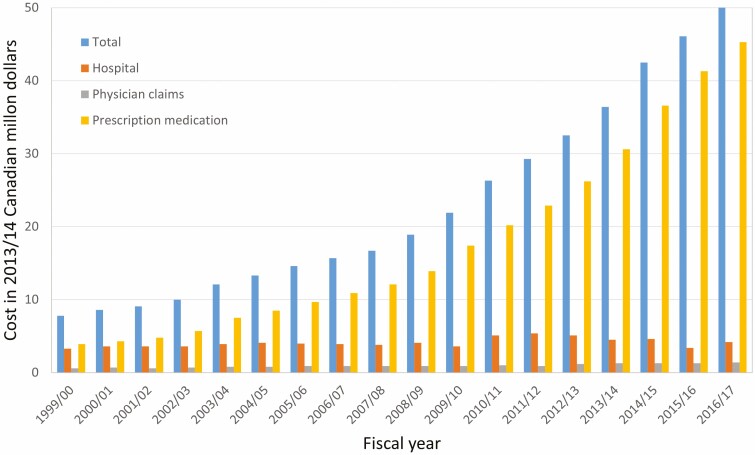

The total estimated direct health care cost of IBD was $7.8 million in 1999/00, observing that prescription medication costs ($3.9 million) and hospital costs ($3.3 million) were the main cost drivers at the beginning of the study period. At the end of the study period, the estimated total direct health care cost of IBD was $50.9 million. Prescription medication costs accounted for $45.3 million, while hospital and physician costs accounted for $4.2 and $1.4 million, respectively. In fact, hospital and physician costs were 10.8% of the entire estimated direct health care cost of IBD in 2016/2017 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Estimated direct health care costs of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Saskatchewan, Canada, from 1999/2000 to 2016/2017. Costs are presented in 2013/2014 Canadian million dollars.

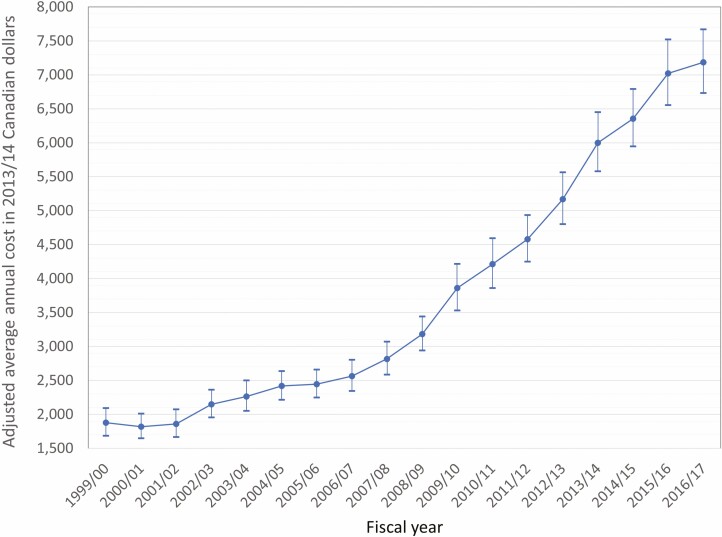

The percent of individuals with non-zero total direct health care costs ranged from 38.9% to 74.7% in each fiscal year. According to the model-based estimates, the average annual direct health care costs of IBD per patient increased from $1879 (95%CI 1686 to 2093) in 1999/2000 to $7185 (95%CI 6733 to 7668) in 2016/2017 (Figure 4). The average annual increase in direct health care costs of IBD per patient was estimated at 9.5% (95%CI 8.9 to 10.1).

Figure 4.

Model-based estimates of total average annual direct health care costs of IBD per patient in Saskatchewan. Costs presented in 2013/2014 Canadian dollars with 95% confidence intervals.

As given in Table 2, the average prescription medication costs per patient are estimated to have dramatically increased from $660 (95%CI 595 to 732) in 1999/2000 to $6530 (95%CI 6024 to 7078) in 2016/2017, with an estimated average annual increase of 15.4 (95% CI 14.6 to 16.2). In contrast, hospital costs per patient fluctuated from $4373 (95%CI 3752 to 5098) in 1999/2000 to $4477 (95% CI 3633 to 5517) in 2016/2017, with no statistically significant change over time (0.8%, 95% CI −0.1 to 1.6). Furthermore, a small average annual percentage increase was observed in physician costs within the study period (0.7%, 95%CI 0.4 to 1.0).

Table 2.

Model-based hospital, physician and prescription medication cost estimates of IBD per patient in Saskatchewan, Canada, from 1999/2000 to 2016/2017

| Fiscal year | Hospital | Physician | Prescription medication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999/2000 | 4373 (3752–5098) | 271 (251–291) | 660 (595–732) |

| 2000/2001 | 4849 (4223–5569) | 280 (259–301) | 670 (608–739) |

| 2001/2002 | 4582 (4033–5205) | 293 (273–314) | 754 (685–830) |

| 2002/2003 | 4388 (3722–5173) | 281 (263–301) | 1006 (893–1134) |

| 2003/2004 | 4368 (3883–4913) | 320 (300–341) | 1122 (1003–1256) |

| 2004/2005 | 4530 (3949–5196) | 323 (304–343) | 1256 (1125–1401) |

| 2005/2006 | 4353 (3854–4916) | 291 (273–309) | 1350 (1208–1510) |

| 2006/2007 | 4560 (4018–5175) | 299 (283–316) | 1527 (1383–1686) |

| 2007/2008 | 4578 (3885–5394) | 300 (283–318) | 1749 (1583–1932) |

| 2008/2009 | 4682 (3992–5491) | 301 (284–319) | 2227 (2020–2455) |

| 2009/2010 | 3871 (3344–4481) | 275 (260–290) | 2604 (2369–2862) |

| 2010/2011 | 5032 (4001–6327) | 323 (306–340) | 2918 (2659–3201) |

| 2011/2012 | 5687 (4503–7180) | 333 (316–351) | 3416 (3119–3742) |

| 2012/2013 | 4887 (4202–5685) | 326 (309–343) | 3987 (3647–4358) |

| 2013/2014 | 4604 (3880–5464) | 308 (295–323) | 4831 (4427–5271) |

| 2014/2015 | 4787 (4011–5713) | 310 (297–325) | 5443 (5011–5912) |

| 2015/2016 | 3544 (3150–3987) | 324 (310–339) | 5951 (5475–6468) |

| 2016/2017 | 4477 (3633–5517) | 295 (273–319) | 6530 (6024–7078) |

| Change (%)* | 0.8 (−0.1 to 1.6) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 15.4 (14.6–16.2) |

Estimated costs of IBD presented in 2013/14 Canadian dollars with 95% confidence intervals.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

*Average annual percentage change. Bolded statistically significant change over time.

Discussion

This retrospective population-based study contributes to the literature with evidence that the prevalence of IBD among adults has been increasing in Saskatchewan, on average at a rate of 3% per annum since 1999. Our results support the findings of a previous study that forecasted a rise in the prevalence rates of IBD in Canada (4). Between 2008 and 2018, Coward et al. (4) reported an increase in the prevalence rates of IBD from 510 to 725/100,000 population. By 2030, this number is expected to rise to 981/100,000 population, equivalent to an average annual percentage change of 2.9% (4). Also, the prevalence rate of IBD for Saskatchewan by Coward et al. was 636/100,000 in 2018; although our study identified a slightly higher prevalence of IBD in Saskatchewan, specifically 664/100,000 in 2016/2017 (4). The results of our research and previous studies support worldwide studies describing and predicting increasing prevalence rates of IBD (1,3).

A study in the United States estimated that the prevalence of IBD will increase from 660/100,000 in 2015 to 790/100,000 in 2025 (3,28). Jones et al. (29) also forecasted an increase in the number of individuals with IBD in Lothian, Scotland (from 1 in 125 for 2018 to 1 in 98 for 2028). Also, Santiago and colleagues (5) reported that the prevalence of IBD will be four to six times higher in Portugal by 2030. Compounding prevalence, where the prevalence grows much more rapidly than the incidence, appears to be inevitable phenomena in the future burden of IBD (3–5). The increasing prevalence of IBD has a significant financial implication that requires attention from both health care professionals and decision-makers.

Our results confirm that IBD is a costly disease and that, direct health care costs are rising. As we identified, the total direct health care cost of IBD in Saskatchewan increased dramatically from 7.8 million CAD in 1999/2000 to 50.9 million CAD in 2016/2017, an increase of more than six-fold. Per patient, the average annual direct health care costs of IBD increased from 1879 to 7185CAD within this study period. In our results, sex (P < 0.0001), age groups (P < 0.0001), disease type (P < 0.0001) and comorbidity index (P < 0.0001) were statistically significant predictors in the cost models, highlighting the need for these predictors to be considered when estimating the direct health care costs of IBD.

A similar pattern of increasing health care cost of IBD has also been reported. For instance, a 2020 study published by researchers from South Korea observed a dramatic increase in IBD-related health care costs from 23.2 million USD in 2010 to 49.7 million USD in 2014 (30). At the end of our study period, most of the IBD costs (almost 90%) were attributed to prescription medication claims. Biologic therapies are the main cost driver of this dramatic increase; these therapies are effective but expensive IBD medications (8,10).

Our cost analyses are consistent with those from the Canadian province of Manitoba. Targownik et al. (23) reported an increase in the total per capita annual costs of IBD in Manitoba from $3354 in 2005 to $7801 in 2015. A significant proportion of this increase in Manitoba was attributed to anti-tumour necrosis therapy costs, which increased from $181 in 2005 to $5270 in 2015 (23). These population-based findings from Saskatchewan and Manitoba reveal that IBD medication costs are increasing over time in Canada and that biologic therapies play a critical role in this increase. This evidence highlights the need to monitor the costs attributable to IBD medication and their trends over time in other Canadian provinces.

In contrast to our findings, international studies estimating the direct health care cost of IBD observed a lower burden of medication costs (8,31–33). In an IBD cohort study in the Netherlands, medications for treating UC and CD accounted for 31% to 64% of total costs for IBD patients (31). Also, a study in Australia attributed 32% and 39% of direct costs of care to prescription medications for patients diagnosed with CD and UC (32). In a recently published Swiss study, medication costs for IBD were 42% and biologic medications accounted for 70% of the total costs (33). However, direct comparisons between these international studies and our work have limitations due to contextual and methodological differences. One of the reasons for the differential burden of medication costs observed in international studies and Canadian ones could be the lack of a strong position for Canadian provinces to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies for the price of medications (34), e.g., price of biologic therapies. Provincial health care systems work and negotiate independently with each of their providers. Among developed countries, Canada is the only one whose provinces deliver universal health care without universal drug coverage (35).

Currently, Canada has an expensive multi-payer drug system which is handled by numerous public and private schemes (35–37). As a result, Canada spends more on medications. Researchers estimate that the introduction of a single-payer drug plan in Canada could yield savings between 4 and 11 billion CAD annually (34,35). These numbers could illustrate the need for cost-effective strategies that can ease the financial burden of IBD at the provincial and national levels. With universal drug coverage in Canada, access to medications and health care outcomes could be potentially improved while reducing health care costs. Future Canadian and international studies should evaluate the presence and absence of universal drug coverage and the effect it may have on medication costs for different chronic conditions, including IBD.

In recent years, studies have observed a shift in the direct health care cost of IBD (8,10). Most of these studies have reported a decrease in IBD hospitalizations and surgeries (8,10). While this decrease may be dependent on numerous factors, the introduction of biologic therapies has been cited as the main reason (8,10,23). Despite the dramatic increase observed in prescription medication costs of IBD, the fact that hospitalization cost remained stable over time in our study despite the increase in the prevalence of CD and UC might be a sign that medication treatments for IBD are effective in reducing the need of inpatient care.

We recognize some limitations of our study. First, misclassification bias in accurately identifying IBD cases is always a concern. This limitation was reduced by applying a validated case definition requiring multiple health care contacts with the diagnosis of IBD. Second, the inclusion of FY as a linear predictor in our model showed a significant annual increase in the prevalence and cost estimates over time. However, the above prevalence and cost figures depict curvilinear features. Therefore, to continue studying the increasing prevalence and cost of IBD, future studies could apply our model-based approach considering nonlinear trends. Besides, the prevalence of IBD in Saskatchewan appears to show a plateau trend during the last years of the study period. Although, it is important to note that the case definition might not be capturing all the true cases during the last years of the study period as multiple health care contacts are required. Regarding the costs of IBD, the databases used in this study did not capture the costs of outpatient laboratory (e.g., blood and stool samples) services, medical imaging or non-physician outpatient care (e.g., care provided by nurses). Finally, studies on the indirect health care cost of IBD are still needed in Saskatchewan and other Canadian provinces.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. This study is the first to link multiple administrative health databases to study the prevalence and direct health care costs of IBD in the province of Saskatchewan. Further strengths of this study include its large sample size, population-based nature and extensive study period of 18 years, which enabled us to test trends over time.

Conclusions

This population-based study provides detailed evidence on the burden of IBD in the province of Saskatchewan. We determined that the prevalence and direct health care costs, among adults respectively, doubled and increased more than six-fold over two decades. Thus, in 2016/2017, the prevalence and total direct health care cost of IBD, respectively, reached 664/100,000 population and 50.9 million CAD. Additionally, we identified that the average direct health care cost for each IBD patient was 7185 CAD at the end of the study period. While the increasing IBD costs are associated with the rising prevalence of the disease, prescription medication costs are playing a quite significant role in the financial burden of IBD. The increasing prevalence and health care costs associated with IBD over time need to be acknowledged by health care decision and policymakers. This study, along with future evidence, could promote the development of cost-effective health care policies at provincial and national levels that respond to the needs of patients living with IBD and reduce per capita costs of health care. For example, a universal pharmacare plan or reforms seeking to adopt a multi-province public pharmacare could support negotiation arrangements through bulk medications purchasing and produce savings to the Canadian health care system.

Funding

This work was supported by the College of Medicine Graduate Student Award - CoMGRAD (University of Saskatchewan) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Project Grant (funding reference number PJT-162393).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant for funding this study. In addition, the authors thank the staff of the Saskatchewan Health Quality Council, specially Meriç Osman, Jacqueline Quail, and Nirmal S. Sidhu who helped in the development of this study. Gilaad G. Kaplan is a CIHR Embedded Clinician Research Chair. This study is based in part on de-identified data provided by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health and eHealth Saskatchewan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of Saskatchewan, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, or eHealth Saskatchewan.

Author Contributions

J.A.O. and J.N.P.S. initiated and designed the study. J.A.O. completed the data analysis, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. L.M.L. and J.N.P.S. contributed to the study design and manuscript preparation. J.A.O., J.N.P.S., S.F., N.M., G.K. and L.M.L. critically revised the study for important intellectual content, contributed to data interpretation, and revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017;390(10114):2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: A scientific report from the Canadian Gastro-Intestinal Epidemiology Consortium to Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2(Suppl 1):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12(12):720–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coward S, Clement F, Benchimol EI, et al. Past and future burden of inflammatory bowel diseases based on modeling of population-based data. Gastroenterology 2019;156(5):1345–1353.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santiago M, Magro F, Correia L, et al. What forecasting the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease may tell us about its evolution on a national scale. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2019;12:1756284819860044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaplan GG, Bernstein CN, Coward S, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: Epidemiology. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2(Suppl 1):S6–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. ; ECCO -EpiCom . The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7(4):322–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuenzig ME, Benchimol EI, Lee L, et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: Direct costs and health services utilization. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2(Suppl 1):17–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehta F. Report: Economic implications of inflammatory bowel disease and its management. Am J Manag Care 2016;22(3 Suppl):s51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: A Canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol 2012;26(11):811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rawla P, Sunkara T, Raj JP. Role of biologics and biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: Current trends and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res 2018;11:215–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernstein CN, Longobardi T, Finlayson G, et al. Direct medical cost of managing IBD patients: A Canadian population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18(8):1498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dan A, Boutros M, Nedjar H, et al. Cost of ulcerative colitis in Quebec, Canada: A retrospective cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23(8):1262–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anderson M, Revie CW, Quail JM, et al. The effect of socio-demographic factors on mental health and addiction high-cost use: A retrospective, population-based study in Saskatchewan. Can J Public Health 2018;109(5–6):810–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, et al. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: A population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149(10):916–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peña-Sánchez JN, Lix LM, Teare GF, et al. Impact of an integrated model of care on outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Evidence from a population-based study. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11(12):1471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101(7):1559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Osei JA, Peña-Sánchez JN, Fowler SA, et al. Population-based evidence from a Western Canadian province of the decreasing incidence rates and trends of inflammatory bowel disease among adults. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2020; gwaa028: 1– 8. doi: 10.1093/jcag/gwaa028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Mack DR, et al. Validation of International algorithms to identify adults with inflammatory bowel disease in health administrative data from Ontario, Canada. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67(8):887–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finlayson G RJ, Dahl M, Stargardter M, McGowan K. The Direct Cost of Hospitalizations in Manitoba, 2005/06. Winnipeg, MB: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Targownik LE, Benchimol EI, Witt J, et al. The effect of initiation of anti-TNF therapy on the subsequent direct health care costs of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25(10):1718–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Resource intensity weights and expected length of stay: discharge abstract database, 2020. https://indicatorlibrary.cihi.ca/display/HSPIL/Cost+of+a+Standard+Hospital+Stay (Accessed July 15, 2020).

- 23. Targownik LE, Kaplan GG, Witt J, et al. Longitudinal trends in the direct costs and health care utilization ascribable to inflammatory bowel disease in the biologic era: Results from a Canadian population–based analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115(1):128–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singh H, Nugent Z, Walkty A, et al. Direct cost of health care for individuals with community associated Clostridium difficile infections: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14(11):e0224609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Statistics Canada. Consumer price index. Health and personal care component. 2020. https://www.150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000408&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.20 (Accessed July 15, 2020).

- 26. Allison PD, Waterman RP. Fixed–effects negative binomial regression models. Sociol Methodol 2002;32(1):247–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuwornu JP, Teare GF, Quail JM, et al. Comparison of the accuracy of classification models to estimate healthcare use and costs associated with COPD exacerbations in Saskatchewan, Canada: A retrospective cohort study. Can J Respir Ther 2017;53(3):37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, Toledo-Mauriño JJ, et al. ; EPIMEX Study Group . Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Mexico from a nationwide cohort study in a period of 15 years (2000-2017). Medicine 2019;98(27):e16291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones GR, Lyons M, Plevris N, et al. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut 2019;68(11):1953–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim JW, Lee CK, Rhee SY, et al. Trends in health-care costs and utilization for inflammatory bowel disease from 2010 to 2014 in Korea: A nationwide population-based study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;33(4):847–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van der Valk ME, Mangen MJ, Leenders M, et al. ; COIN study group and the Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis . Healthcare costs of inflammatory bowel disease have shifted from hospitalisation and surgery towards anti-TNFα therapy: Results from the COIN study. Gut 2014;63(1):72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Niewiadomski O, Studd C, Hair C, et al. Health care cost analysis in a population-based inception cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients in the first year of diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9(11):988–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bähler C, Vavricka SR, Schoepfer AM, et al. Trends in prevalence, mortality, health care utilization and health care costs of Swiss IBD patients: A claims data based study of the years 2010, 2012 and 2014. BMC Gastroenterol 2017; 17(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morgan SG, Law M, Daw JR, et al. Estimated cost of universal public coverage of prescription drugs in Canada. CMAJ 2015;187(7):491–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brandt J, Shearer B, Morgan SG. Prescription drug coverage in Canada: A review of the economic, policy and political considerations for universal pharmacare. J Pharm Policy Pract 2018;11:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morgan SG, Leopold C, Wagner AK. Drivers of expenditure on primary care prescription drugs in 10 high-income countries with universal health coverage. CMAJ 2017;189(23):E794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clement FM, Harris A, Li JJ, et al. Using effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to make drug coverage decisions: A comparison of Britain, Australia, and Canada. JAMA 2009;302(13):1437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.