Abstract

There is much concern today about the spread of fake news and the misinformation it can produce among the public. In this article, we investigate how the American public interprets accurate and inaccurate statements from the news. Moving beyond partisanship, we theorize that ideological and ethnoracial identities also shape individuals’ interpretations of the news. We argue that people have incentives to interpret information they encounter in ways that favor their ideological and ethnoracial ingroups and that these incentives are particularly strong when ideological and ethnoracial identities align. Using a survey that asks respondents to classify statements from news stories as facts or opinions, we find support for these hypotheses. Liberals and conservatives, and white, Black, and Hispanic respondents, more often classify as factual statements that favor their ingroup’s interests while classifying information opposing their ingroup’s interests as opinions. Holding cross-cutting ethnoracial and ideological identities diminishes these effects, while identities that align produce stronger ingroup biases in information processing, particularly among whites. Our study reveals that it is not only partisanship but also ideological and ethnoracial identities that shape how Americans interpret the news, and therefore how informed, or misinformed, they are.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, the media extensively covered the disease. In one Washington Post article discussing hydroxychloroquine as a treatment, readers encountered statements including:

“‘I think it’s good. I’ve heard a lot of good stories… Here’s my evidence. I get a lot of positive calls about it,’ Trump said Monday. ‘The only negative I’ve heard was the study where they gave it—was it the VA with, you know, people that aren’t big Trump fans gave it,’” and

“In late April, researchers posted an analysis of the medical records of 368 male patients at Veterans Affairs hospitals nationwide and found that the rates of death in those treated with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with the antibiotic azithromycin were higher than in those who did not receive the drugs.” (Gearan et al. 2020)

Trump’s declaration that “it’s good” is an opinion—a belief based on his views regarding feedback he’s heard about hydroxychloroquine. The second statement is a fact—it can be proven true or verified based on evidence. Yet the spring 2020 increase in prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine suggests people sought out the drug based on trusting an opinion rather than a fact. This case provides yet another example of why many are concerned about the spread of “fake news” and misinformation and their consequences for political (and other) behavior (e.g., Southwell, Thorson, and Sheble 2018; O’Connor and Weatherall 2019).

What determines how people interpret information they obtain from the media or other sources? Previous literature explains that people tend to evaluate information they receive in line with their partisan identity (Lodge and Hamill 1986; Taber and Lodge 2006). People know more about things that relate to their own party (Lodge and Hamill 1986; Jerit and Barabas 2012) and form opinions in a way consistent with their partisanship (Bartels 2002; Bolsen, Druckman, and Cook 2014; Weeks 2015; Flynn, Nyhan, and Reifler 2017). We know less about other forces that may shape how people read and interpret the news. Yet there are reasons to believe that other identities might also affect how people interpret facts and opinions about the world. In this paper, we investigate the role ideology and ethnoracial membership play in shaping people’s understanding of the news.1 Might one’s ability to distinguish the fact from the opinion statement above depend on attachments other than partisanship? We theorize and provide evidence supporting this possibility.

Drawing on a survey that asks respondents to classify statements from news stories as facts or opinions, we examine how an individual’s ideology, ethnoracial membership, and the intersection of the two shape their classifications of fact and opinion statements. Because ideology and ethnoracial membership are powerful social identities, we theorize that people have incentives to interpret information they encounter in ways that favor their ideological and ethnoracial ingroups. We further expect that this incentive is largest when one’s ideology and ethnoracial membership align regarding a particular piece of information. Thus, we hypothesize that people will classify as “facts” statements seen to benefit their identity groups and will classify as “opinions” statements perceived as detrimental to their groups. We find support for this hypothesis. Identity shapes how Americans interpret information—an effect with implications for political behavior from policy attitudes to vote choice. Furthermore, this effect is not constrained to partisan identity, the primary focus of the literature to this point. Rather, we demonstrate that ideology and ethnoracial membership also influence how individuals interpret information and how informed, or misinformed, they are.

Social Identities Affect Political Knowledge and Behavior

People may associate with many groups based on their personal traits, position in society, and affiliations to which they have been socialized. Social identity theory demonstrates that individuals will closely identify with some of these groups. Further, this close identification yields ingroup favoritism, as upholding positive beliefs about groups one identifies with is important for upholding one’s own self-image (Tajfel 1974; Leonardelli, Pickett, and Brewer 2010), and ethnocentrism, leading people to define groups as friend or foe and favor members of their preferred groups (Kinder and Kam 2010). This behavior can have powerful political consequences.

Most research on the effects of social identity on political knowledge and information have focused on partisan identity. Motivated reasoning leads partisan identifiers to believe information that benefits their partisan ingroup over their partisan outgroup, regardless of its accuracy (Bartels 2002; Bullock 2007; Jerit and Barabas 2012; Theodoridis 2017). Indeed, people are generally more willing to believe a piece of information that aligns with their partisanship or that makes the party they oppose look bad—even if that information is from a less credible source (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus 2013; Kahan 2013; Schroeder and Stone 2015; Meirick and Bessarabova 2016). This systematic filtering of information can affect how partisans perceive, reward, and punish political figures (Lebo and Cassino 2007).

However, motivated reasoning and biased engagement with information can occur when individuals seek to bolster a variety of beliefs or issue positions (Lodge and Taber 2013). Thus, other social identities may have similar political consequences as partisanship. Huddy (2013) outlines that political cohesion of a social group—and thus group membership’s ability to affect political behavior—is more likely to occur when an identity is strong, has political meaning, and when group members perceive threats to their group (whether realistic or not). We propose that each of these criteria is present not just for partisanship but also for ideological identification and ethnoracial group membership. Thus, we expect these will affect political behavior—including levels of political (mis)information.

Ideology

While ideology is often defined as a set of cohesive positions on issues, it is likely more accurate to consider ideological identification a social identity. Only a minority of knowledgeable citizens show “polar, coherent, stable, and potent ideological orientations” that fit with the former definition (Converse 1964; Kinder and Kalmoe 2017; Kalmoe 2020, p. 1). Rather, for many, ideology is a symbolic identity—like partisanship (Ellis and Stimson 2012)—that can have powerful effects based on “the intensity with which individuals identify with the groups that are labeled liberals or conservatives [rather than] the set of individual policy preferences that each person holds” (Mason 2018, p. 22). In part because it has become sorted into alignment with other social identities such as partisanship, region, and religion (Mason 2018), ideology is a strong group identity for many Americans. It is also “inherently political and automatically generate[s] political cohesion among strong identifiers” (Huddy 2013, p. 747). Additionally, due to discourse among political leaders and the media who seek to promote “conservative thinkers” and attack ideological outgroups like the “left, liberal media” (Carlson 2019; Trump 2019), liberals and conservatives likely perceive threats to and grievances shared by their ideological group.

Consequently, despite ideologues’ rarity, there are significant effects of ideological identification on behavior. Individuals are more likely to approve policies supported by their ideological ingroup (Malka and Lelkes 2010). A desire to maintain views favorable to one’s ideology can lead to the acceptance of conspiracy theories, particularly among conservatives (Miller, Saunders, and Farhart 2016), and can prevent individuals from accepting corrections about misperceptions they hold or even provoke a “backfire effect” in which misperceptions become more strongly held (Nyhan and Reifler 2010). Ideological disagreement has increased affective polarization between partisans (Webster and Abramowitz 2017). Further, ideological and partisan identities can even lead to shifts in one’s generally closely held religious, ethnic, and LGB identities (Egan 2020).

While the effects of ideological identity on some political behaviors are similar to the effects of party identity, it is important to differentiate their effects, as ideology and partisanship are “distinct (though interrelated) facets of political identity” (Deichert, Goggin, and Theodoridis 2018, p. 28). Americans hold on to their ideological and partisan identities at differing rates, and ideology is more likely than partisanship to shift over time (Kinder and Kalmoe 2017).

Further, research suggests that ideology is a weaker identity for some ethnoracial groups. Black Americans’ partisanship and ideological identifications align less often, perhaps due to racialized social constraint (White and Laird 2020) or prioritizing racial group consciousness over ideological conservatism (Philpot 2017)—or because ideological labels are less meaningful for Black than white Americans (Jefferson 2020). Ideology and partisanship are less closely linked among some groups of Hispanics as well, perhaps due to socialization and experiences with other political systems among immigrants to the United States (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010). These findings question the validity of ideology as a predictor of political behavior across ethnoracial groups.

In a context of polarization that has boosted ideological consistency (Pew Research Center 2014, 2017), we thus evaluate whether ideology has an effect on political (mis)information distinct from partisanship and across ethnoracial groups. Because ideology can function as a social identity, leading group identifiers to prefer information that upholds positive views of their group, we expect it to shape interpretations of political information. Specifically, we hypothesize that people will interpret as facts, rather than opinions, information that is consistent with their ideological group interests (H1). Because ideological labels may be less meaningful for Black and Hispanic than white Americans, this effect may be larger among whites (see H3 below).

Ethnoracial Group Membership

Ethnoracial group membership is also a social identity that can shape political behavior, leading to affinity voting and supporting group causes among Blacks, whites, and Latinos (Sanchez 2006; Sidanius et al. 2008). There is also political meaning associated with ethnoracial membership in the United States, as the two major parties have diverging ethnoracial composition and distinct positions on race-related policies and the status of ethnoracial groups (Huddy 2013; Huddy, Mason, and Horwitz 2016; Tesler 2016; Mason and Wronski 2018; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck 2018; Jardina 2019b). Finally, ethnoracial group members often perceive shared interests, grievances, and threats with others in their group. Research on group consciousness and linked fate highlights the presence of a “black utility heuristic” (Dawson 1994) among African Americans (Olsen 1970; Dawson 1994; Chong and Rogers 2005; Mangum 2007). Although perceptions of linked fate are generally lower among the panethnic categories of Hispanic or Latino, studies also reveal evidence of Latino-linked fate (Sanchez and Masuoka 2010; Fraga et al. 2011), with levels affected by socioeconomic status, acculturation, perceptions of discrimination, and social movements (Masuoka 2006; Barreto and Pedraza 2009; Stokes‐Brown 2012; Zepeda-Millán 2017). Research increasingly identifies shared perceptions of threat among white Americans as well, due both to beliefs about increased immigration to the United States (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015) and to the election of America’s first Black president (Parker, Sawyer, and Towler 2009; Tesler 2016; Yadon and Piston 2019).

The effects of ethnoracial membership on political behavior are wide ranging. For example, compared to other ethnoracial groups, white Americans are more opposed to immigration; whites with high white identity or group consciousness are especially more supportive of policies like Social Security and candidates like Donald Trump who they believe help their ethnoracial ingroup (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015; Schildkraut 2017; Jardina 2019a, 2019b). Prejudice held by whites toward Black Americans and Hispanics (Goff et al. 2008; Huddy and Feldman 2009; Pérez 2016; Yadon and Piston 2019) also shapes political behavior and attitudes toward candidates of color and policies perceived as benefiting particular ethnoracial groups (Kam 2007; Banks and Hicks 2016; Pérez 2016; Tesler 2016; Kinder and Ryan 2017; Ramirez and Peterson 2020). Racial prejudice even affects perceptions of information. White Americans holding negative attitudes about Blacks are more likely to believe rumors about President Obama’s birthplace (Pasek et al. 2015; Jardina and Traugott 2019). And racially prejudiced individuals are more likely to resist correction of misinformation when misinformation enables opposition to a Black candidate from their party (Flynn and Krupnikov 2019). Further, both white and Black Americans seek out information about officer-involved shootings that is favorable to their racial ingroups and interpret new information in light of their “racially distinct priors” (Jefferson, Neuner, and Pasek 2020).

Ethnoracial membership also shapes behavior among Hispanics and Black Americans. This may be due to how ethnoracial membership shapes an individual’s life experiences, or to a broader desire to support groups with whom one perceives a linked fate. For example, Black Americans are more likely than whites to experience discrimination and are more supportive of government efforts to promote equality and address discriminatory policies affecting their group (Tate 1994; Alexander 2012; Dowe 2016). Hispanics and Asians are more likely to have recent personal or familial experience with immigration (Lopez and Radford 2017), and are less likely to favor restrictive immigration policies (Masuoka and Junn 2013). In fact, evidence demonstrates that more punitive immigration policies (Vargas, Sanchez, and Valdez 2017), higher immigration enforcement (Maltby et al. 2020), and President Donald Trump’s harsher anti-immigrant and discriminatory rhetoric (Le, Arora, and Stout 2020) increased panethnic linked fate among Latinos (including those born in the United States) and Asian Americans.

Further, while the interests of Black Americans and Hispanics do not always overlap, there are some reasons to expect Blacks and Hispanics to perceive political information in ways aimed at supporting a broader ethnoracial minority ingroup rather than just their own specific ethnic or racial ingroup. Lopez and Pantoja (2004) find fairly broad support for race-conscious policies that apply to a broad set of ethnoracial groups among Blacks and, to a lesser extent, among Latinos. Even on the issue of immigration, where Black Americans have been perceived to hold more nativist opinions, recent research finds that Blacks feel positively toward immigrants and perceive commonality with Latinos relative to whites (Carter 2019). The recent rise in acceptance of explicitly racial rhetoric and increasing levels of hate crimes and white supremacist activities in the United States (FBI 2018; Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek 2018; Farley 2019) may have reinforced a shared identity among those most likely to be targeted by hateful rhetoric, strengthening support among Black Americans and Hispanics for policies perceived as beneficial to ethnoracial minorities more broadly. Perceiving discrimination while holding group consciousness regarding one’s own group can increase perceptions of commonality with other groups (Sanchez 2008)—even among those who have not personally experienced discrimination (Lu and Jones 2019). Additionally, having superordinate goals “that go beyond group boundaries and include both groups” can diminish distrust of outgroups (Mason 2018, p. 133). Opposing the rise of white supremacy and explicit racism in the United States may serve as a superordinate goal, and perceiving discrimination in the current hostile racial context may extend group consciousness across “people of color” (Pérez 2021). Together, these could promote support among an ethnoracial minority group for policies that benefit other groups or limit white supremacy.

We theorize that the same forces that lead those who classify as Black, white, and Hispanic to support policies and candidates perceived as beneficial to their ethnoracial ingroup will also shape how those from specific ethnoracial groups perceive political information. Specifically, we hypothesize that people will interpret as facts, rather than opinions, information that is consistent with their ethnoracial group interests (H2).

Interacting Ideology and Ethnoracial Group Membership

The alignment of one’s social identities can influence how powerfully they affect political behavior. People with more sorted identities—whose party, ideology, religion, race, and Tea Party affiliation align in a consistent direction politically—show higher partisan prejudice (Mason 2018). Individuals with more aligned identities demonstrate less outgroup tolerance, more prejudice toward outsiders (Brewer and Pierce 2005), and more racial prejudice (Miller, Brewer, and Arbuckle 2009). On the other hand, having cross-cutting identities that do not politically align can diminish polarization, negative attitudes toward outgroups, favorable attitudes toward ingroups, and emotional reactivity when faced with threats or reassurances (Mason 2016, 2018; Deichert, Goggin, and Theodoridis 2018). Consequently, we hypothesize that people will be more likely to interpret as facts, rather than opinions, information that is consistent with the interests of both their ideological and ethnoracial groups, than information that is consistent with the interests of only one of their identity groups (H3). However, because research suggests ideological labels are more consistently understood by white than Hispanic or especially Black Americans (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010; Jefferson 2020), this effect should be largest among white respondents.

Defining Group Membership and Group Interests

Our hypotheses predict that individuals will interpret information differently based on their ideological and ethnoracial identities. Existing research documenting such “identity-to-politics” links varies widely in how identity is measured—examining distinctions between individuals simply classified as belonging to particular groups, between those expressing strong identification with their groups, or between those with varying levels of group consciousness or resentment toward outgroups (Lee 2008). These comparisons can thus find an identity-to-politics link for reasons including: shared individual experiences across many members of a group (e.g., distinct treatment by law enforcement, recent experience with the immigration system, experiences of racism and prejudice), a desire to uphold positive views of a group with whom one identifies closely (either through genuinely believing information that favors that group or through responding positively to information favoring that group without sincerely believing it), or attempts to favor the interests of a group with whom one perceives a linked fate through promoting that group or hindering an outgroup seen as a threat.

Each of these mechanisms may play a role in shaping the behavior of respondents in our study. Our data enables us to compare respondents who self-classify into one ethnoracial or ideological group with those in another group. We do not have access to variables measuring strength of identity, group consciousness, or prejudice, nor thus the ability to measure their effects on interpretations of political information. However, other studies show high levels of ethnoracial identity among those classified into each ethnoracial group. In recent national surveys, many Black (69–85 percent) and Hispanic (49–75 percent) respondents and some white (30–40 percent) respondents indicate that their ethnorace is very or extremely important to their identity (Jardina 2019b). Thus, we anticipate that those classified into different ethnoracial groups will interpret information differently. Future studies examining the effects of strong group identification, racial resentment, or racial sympathy might find even stronger effects of these variables on information processing. Regarding ideological identification, 2016 American National Election Studies data reveal closeness between those who self-identify as liberal or conservative and those in their ideological ingroups. Specifically, those who self-identified as (slightly to extremely) liberal indicated an average feeling thermometer rating of 71 degrees for liberals and only 36 degrees for conservatives, while those identifying as (slightly to extremely) conservative rated conservatives at 69 degrees and liberals at 32 degrees on average (these differences are of similar magnitude and statistically significant for all ethnoracial groups except Black conservatives). Consequently, we expect ideological self-identification in our data to shape respondents’ perceptions of information to favor the ideological ingroup toward whom they likely feel warmly.

Data and Method

To test our hypotheses, we use data from a Pew Research Center survey of American adults fielded in February–March 2018 (8,066 panelists were invited to take part, of whom 5,035 completed the survey, for a cooperation rate of 62 percent). This survey examines “whether members of the public can recognize news as factual—something that’s capable of being proved or disproved by objective evidence—or as an opinion that reflects the beliefs and values of whoever expressed it” (Pew Research Center 2018, p. 3). The questionnaire presented to respondents a series of “statements that have been taken from news stories.” Respondents were asked, “Regardless of how knowledgeable you are about the topic, would you consider this statement to be a factual statement (whether you think it is accurate or not) OR an opinion statement (whether you agree with it or not)?”2 Supplementary Material section 1 describes the data and variables.

We hypothesized that people will be more likely to interpret a statement as a factual statement when it contains information that is consistent with their (ideological and/or ethnoracial) group interests, whereas they will interpret a statement as an opinion if its information is perceived as detrimental to the interests of their ingroup(s). Consider this statement: “Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally have some rights under the Constitution.” According to previous literature, this should be perceived as threatening to the interests of those classified as white because they are more likely to perceive immigrants to the United States as a threat (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015), while members of ethnoracial groups concerned about increases in explicit prejudice and discrimination would perceive this statement as beneficial to themselves or those with whom they hold shared interests (Sanchez 2008). We therefore expect that Black or Hispanic respondents will be more likely to classify this statement as a fact than white respondents, while white respondents should be more likely to classify this statement as an opinion than Black or Hispanic respondents.3 Similarly, we would expect a statement like “Abortion should be legal in most cases” to be perceived differently by respondents based on their ideology. Conservatism (relative to liberalism) is strongly associated with negative attitudes toward legal abortion, even controlling for religious and partisan identities (Yen and Zampelli 2017), for reasons including preferences for traditional values and minimal social change among conservatives and increased receptivity to social change and prioritization of (gender) equality among liberals (Cook, Jelen, and Wilcox [1992] 2018). Given this, we expect that liberal respondents will be more likely to classify this statement as a fact, and conservative respondents as an opinion.

Drawing on similar logic and the extant literature, we classified each statement according to whether it favors the interests of an ideological group (liberal or conservative) and/or an ethnoracial group (white, Black or Hispanic) (for a similar strategy, see Jerit and Barabas 2012). Four coders allocated all statements to any of these categories, with 100 percent agreement (see also Pew Research Center 2018, pp. 24–27). A statement is classified as liberal (or conservative/wWhite/Black or Hispanic) if its correct classification as either fact or opinion is generally consistent with the interests of the corresponding identity group.

Table 1 presents the exact wording of the 10 statements and their classifications—whether the statement would correctly be considered a fact or an opinion, and which ideological and ethnoracial groups’ interests are more consistent with the correct answer for each item. In addition, we provide references that support our classification of the group interests supported by each statement. Table 1 reveals an overlap between ideological and ethnoracial interests, as all items that are coded as Black or Hispanic are also coded as liberal, and the only item that is coded as white is conservative.

Table 1.

Classification of 10 statements judged to be fact or opinion

| Statement | Correct answer | Ideological group interest | Ethnoracial group interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| President Barack Obama was born in the United States.a | Fact | Liberal | Black or Hispanic |

| Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally have some rights under the Constitution.b | Fact | Liberal | Black or Hispanic |

| Health care costs per person in the U.S. are the highest in the developed world.c | Fact | Liberal | |

| Immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally are a very big problem for the country today.d | Opinion | Liberal | Black or Hispanic |

| Government is almost always wasteful and inefficient.e | Opinion | Liberal | |

| Abortion should be legal in most cases.f | Opinion | Conservative | |

| Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential for the health of the U.S. economy.g | Opinion | Conservative | |

| ISIS lost a significant portion of its territory in Iraq and Syria in 2017.h | Fact | Conservative | |

| Spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid make up the largest portion of the U.S. federal budget.i | Fact | Conservative | |

| Applying additional scrutiny to Muslim Americans would not reduce terrorism in the U.S.j | Opinion | Conservative | White |

aCoding of interests based on Jardina and Traugott (2019); Parker, Sawyer, and Towler (2009); Pasek et al. (2015); Tesler (2016); Yadon and Piston (2019).

bCoding of interests based on Abrajano and Hajnal (2015); Brooks, Manza, and Cohen (2016); Jardina (2019b).

cCoding of interests based on Jerit and Barabas (2012); Sears et al. (1980).

dCoding of interests based on Abrajano and Hajnal (2015); Brooks, Manza, and Cohen (2016); Jardina (2019b).

eCoding of interests based on Lakoff (2010).

fCoding of interests based on Hout (1999); Lakoff (2010).

gCoding of interests based on McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal (2016).

hCoding of interests based on Nincic and Ramos (2010).

iCoding of interests based on Baker and Hunt (2016); McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal (2016).

jCoding of interests based on Brown-Dean (2019); Masuoka and Junn (2013); Mitchell (2016); Theiss-Morse (2009); Wong (2018).

Based on these classifications, we developed two types of dependent variables. First, we created one variable for each statement that takes the value 1 if it is classified correctly as fact or opinion by the respondent and 0 if not. Second, we created two additive scales that correspond with our ideological and ethnoracial group classifications for the statements. The ideological statements scale is composed of all items listed in table 1. It is coded so that a higher number indicates that a respondent classified more items consistently with liberal interests while a lower number indicates that respondents classified more items consistently with conservative interests. Thus, a respondent with a 0 on this variable classified all statements consistently with the interests of a conservative, while a 1 indicates that a respondent classified all statements consistently with liberal interests.4 The ethnoracial statements scale is composed of four items, coded so that a higher number indicates that a respondent classified more items consistently with the interests of Blacks or Hispanics—given literature predicting some shared group consciousness and interests across these ethnoracial groups—while a lower number indicates that a respondent classified more items consistently with the interests of whites.5 Thus, a 0 on this scale means a respondent classified all statements consistently with the interests of whites and a 1 means all statements were classified consistently with Black or Hispanic interests.

Our main independent variables are ideology and ethnoracial group. Ideology is a categorical variable that distinguishes between liberal (the reference category), moderate, and conservative respondents.6 The ethnoracial group variable distinguishes between respondents who classify as white (the reference category), Black, Hispanic, and a non-Hispanic other race. While our theory and existing literature provide reasons to expect that Blacks and Hispanics will perceive some shared interests across ethnoracial lines, we distinguish between these groups in our analyses given the many distinctions in their experiences and political behavior and in order to test whether the two groups actually do interpret political information in a similar way. We also include a number of controls that are typical antecedents of people’s political information: age, sex (female is coded as 1), level of education (High school or less—the reference category; Some College; Bachelor’s degree or more); and income (from less than $5,000 to $250,000 or more; treated as continuous). In addition, because statements are presented as if they appeared in news stories, we control for an individual’s trust in national news organizations (four categories, from not at all to a lot). Finally, to test the effects of ideological (and ethnoracial) membership on political information distinct from partisanship, and because partisanship consistently drives interpretations of information in existing research, all analyses control for the party identification of the respondents (Republican—the reference category, Democrat, Independent, Other).

In our first analyses, we examine correct categorization of each statement as a separate dependent variable. Then we use linear regression to estimate the relationship between respondents’ ideology and ethnoracial groups and their scores on the ideological and ethnoracial statements scales.

Results

Table 2 presents the percentage of respondents, by ideology and ethnoracial membership, who classify each individual statement correctly. We also indicate the statistical significance of ideology and ethnoracial group coefficients from logit models predicting correct classification of each statement by respondent identities while controlling for sex, age, education, income, media trust, and party identification (see Supplementary Material table SM.2).

Table 2.

Percentage of respondents who classify each statement correctly

| Respondent identifies as |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Conserv. | p-value | |

| Obama born in US | 90% | 67% | 0.000 |

| Immigrants have rights | 72% | 43% | 0.000 |

| Health care costs high in US | 84% | 72% | 0.001 |

| Immigrants are problem | 86% | 52% | 0.000 |

| Government is wasteful | 78% | 65% | 0.073 |

| Abortion should be legal | 78% | 86% | 0.013 |

| Wage increases are essential | 69% | 81% | 0.036 |

| ISIS lost territory | 73% | 72% | 0.537 |

| Social programs are much of budget | 60% | 62% | 0.040 |

|

Muslim scrutiny wouldn’t reduce terrorism |

69% |

80% |

0.028 |

|

Average correct |

76% |

68% |

0.000 |

|

Respondent identifies as |

|||

|

White |

Black |

p-value |

|

| Obama born in US | 76% | 86% | 0.062 |

| Immigrants have rights | 53% | 58% | 0.606 |

| Immigrants are problem | 65% | 80% | 0.000 |

|

Muslim scrutiny wouldn’t reduce terrorism |

81% |

62% |

0.000 |

|

Average correct |

69% |

72% |

0.575 |

|

Respondent identifies as |

|||

|

White |

Hispanic |

p-value |

|

| Obama born in US | 76% | 78% | 0.508 |

| Immigrants have rights | 53% | 64% | 0.037 |

| Immigrants are problem | 65% | 75% | 0.077 |

|

Muslim scrutiny wouldn’t reduce terrorism |

81% |

62% |

0.000 |

| Average correct | 69% | 70% | 0.225 |

Note.—Table displays the percentages of liberal/conservative respondents and white/Black/Hispanic respondents who accurately classified each statement as a fact or an opinion, and indicators of statistical significance (two tailed p-values) of the coefficients for conservative identity (compared to liberal identity), Black identity (compared to white identity), and Hispanic identity (compared to white identity). These p-values are drawn from logit models—displayed in Supplementary Material table SM.2 predicting correct classification of each statement by ideological and ethnoracial identification, controlling for sex, age, education, income, trust in media, and party identification. All data are weighted. Data Source: Pew Research Center (2018).

Table 2 reveals that a majority of respondents are able to classify most statements correctly as a fact or an opinion, and the patterns of responses by ideological and ethnoracial identities are consistent with our first and second hypotheses. Specifically, we find that liberals and conservatives each tend to classify more accurately statements for which doing so is consistent with the interests of their ideological identity. Indeed, our models controlling for other respondent characteristics (including party identification) reveal that conservatives are statistically less likely than liberals to classify each liberal-leaning statement correctly and more likely to classify all but one conservative-leaning statement correctly. Only the statement about ISIS does not provide results in our hypothesized direction; here, the percentage of correct answers is nearly identical for liberals and conservatives and there is no statistically significant effect of ideological identity on correct classification in our multivariate model. In all, then, these results suggest strong support for H1.

H2 is also supported by the results in table 2. We find that Hispanic and Black respondents are more likely than white respondents to correctly classify as facts the statements that are favorable to ethnoracial minority interests and as opinion the statement that is unfavorable to minority interests. On the other hand, white respondents classify the statement about Muslims correctly as an opinion more frequently than Black and Hispanic respondents, consistent with white interests. We also find differences in how Black and Hispanic respondents classify individual statements, supporting our argument that ethnorace shapes perceptions of political information. Black respondents are more likely to classify the news about Obama’s birth in the United States as a fact than Hispanics or whites (see table 2). Given Obama’s identification as Black, this statement is more important for affirming Black than Hispanic ingroup identity. In addition, while a higher percentage of both Black and Hispanic respondents than white respondents classify the statements referencing immigrants accurately, our multivariate models reveal that Hispanics (relative to whites) are statistically more likely to accurately classify both immigrant-related statements while Black identity is related to accurate classification of only one of these two statements. Thus, there is some sense of shared interests across the Black and Hispanic ethnoracial groups, but belonging to a specific ethnic or racial group also shapes perceptions of political information for white, Black, and Hispanic respondents.

In table 3, we identify factors influencing respondents’ positions on the ideological and ethnoracial statements scales. These results confirm that party identification shapes interpretations of political information—Democrats and Independents, relative to Republicans, are more likely to classify statements in line with liberal ideology and ethnoracial minority group interests. Importantly, however, table 3 also demonstrates that even controlling for this effect of partisanship, both ideology and ethnoracial membership also shape respondents’ behavior.

Table 3.

The influence of ideological and ethnoracial identities on perceptions of the news—ordinary least squares regression estimates (and standard errors)

| Ideological statements scale (Model 1) |

Ethnoracial statements scale (Model 2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Democrat | 0.0859 | 0.000 | 0.127 | 0.000 |

| (ref. Republican) | (0.00657) | (0.0108) | ||

| Independent | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.0773 | 0.000 |

| (ref. Republican) | (0.00596) | (0.00981) | ||

| Other Party | 0.0618 | 0.000 | 0.0893 | 0.000 |

| (ref. Republican) | −0.00826) | (0.0136) | ||

| Moderate | −0.0258 | 0.000 | −0.0653 | 0.000 |

| (ref. Liberal) | (0.00553) | (0.00909) | ||

| Conservative | −0.0692 | 0.000 | −0.114 | 0.000 |

| (ref. Liberal) | (0.00672) | (0.0111) | ||

| Black | 0.0687 | 0.000 | 0.0631 | 0.000 |

| (ref. White) | (0.00697) | (0.0115) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.000 |

| (ref. White) | (0.00612) | (0.0101) | ||

| Other Race | 0.00495 | 0.524 | −0.00231 | 0.856 |

| (ref. White) | (0.00776) | (0.0128) | ||

| Sex | 0.013 | 0.002 | −0.00234 | 0.732 |

| (1=female) | (0.00414) | (0.00682) | ||

| Age | −0.000525 | 0.000 | −0.00193 | 0.000 |

| (0.000124) | (0.000204) | |||

| Some college | 0.00569 | 0.276 | 0.0364 | 0.000 |

| (ref. High school) | (0.00523) | (0.0086) | ||

| Bachelor | 0.00484 | 0.392 | 0.0864 | 0.000 |

| (ref. High school) | (0.00566) | (0.00931) | ||

| Income | −0.000164 | 0.741 | 0.00366 | 0.000 |

| (0.000497) | (0.000818) | |||

| Trust in media | 0.0269 | 0.000 | 0.0544 | 0.000 |

| (0.00261) | (0.0043) | |||

| Constant | 0.402 | 0.000 | 0.391 | 0.000 |

| (0.0128) | (0.0211) | |||

| Observations | 4,843 | 4,840 | ||

| R-squared | 0.222 | 0.235 | ||

Note.—Tests of significance are two-tailed. All data are weighted. Data Source: Pew Research Center (2018).

First, Model 1 in table 3 supports H1: being conservative is negatively associated with the ideological statements scale, meaning that conservatives are less likely to interpret political statements in a way favorable to the interests of liberal identifiers than are liberals. And Model 2 demonstrates support for H2: self-classifying as Black or Hispanic is positively associated with the ethnoracial scale—Black and Hispanic respondents interpret the statements in line with the interests of ethnoracial minority groups while white respondents interpret the statements in ways consistent with white identity interests. These findings indicate that partisanship, ideology, and ethnoracial identity are each separate identities that affect individuals’ interpretations of the news.

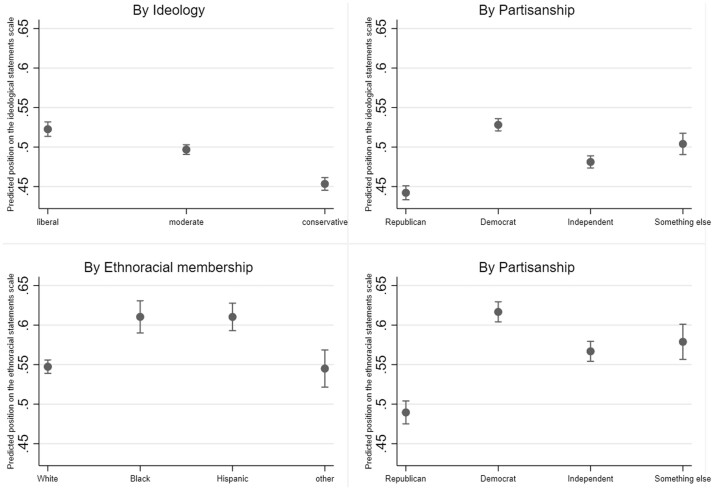

The consequences of these effects can be seen clearly in figure 1. Here we display average marginal respondents’ positions on the ideological and ethnoracial statements scales (which each range from 0 to 1) by ideology and ethnoracial membership, predicted using results from Models 1 and 2. To assess the magnitude of these effects in comparison to the effects of partisanship, we also present the respondent’s positions on the two scales by partisanship. Figure 1 shows that the gap between conservative and liberal identifiers on the ideological statements scale is nearly a tenth of the entire scale—or classifying an entire additional statement differently—almost the same difference as between Republicans and Democrats. Ethnoracial identity also shapes information processing, with white and other race identifiers scoring lower than Black and Hispanic respondents on the ethnoracial statements scale—a significant difference, though one smaller than that between partisans.

Figure 1.

Average marginal effects of ideological and ethnoracial identities. Figure presents the predicted average respondents’ positions on the ideological (upper figure) and ethnoracial (lower figure) statements scales by ideology, ethnorace, and partisanship, predicted based on Models 1 and 2 in table 3.

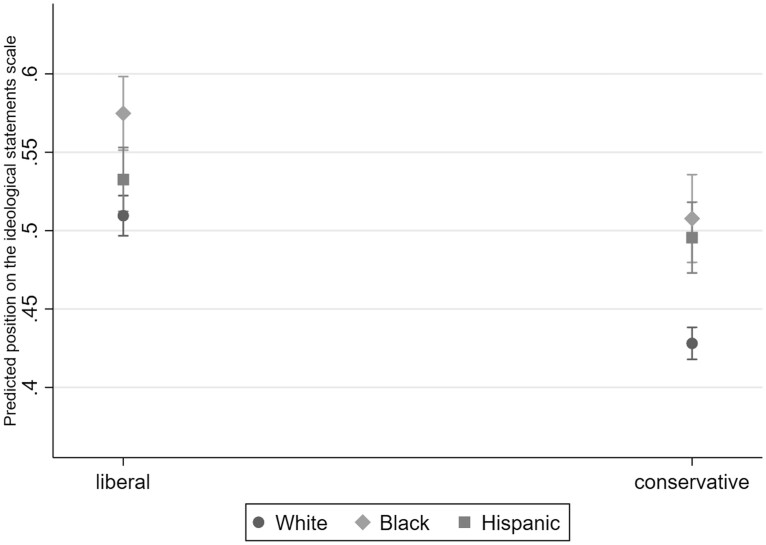

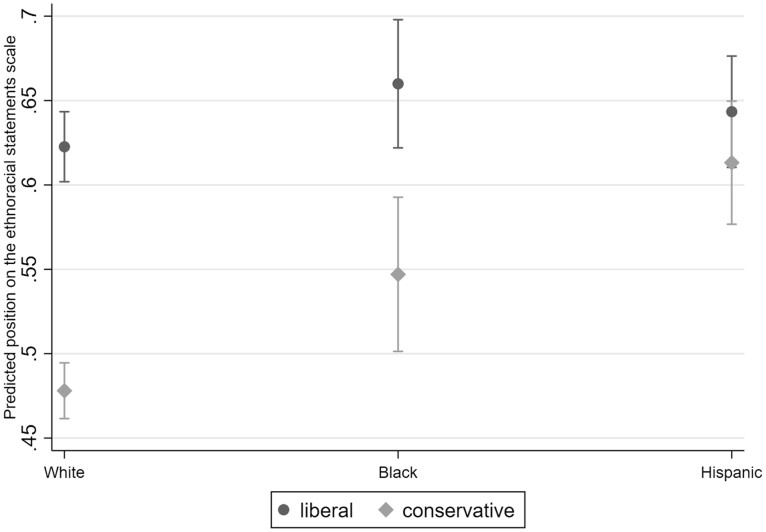

H3 predicts that ideological and ethnoracial identities do not work in isolation. Rather, we expect that people will be more likely to classify as fact information that is consistent with the interests of both their ethnoracial and ideological groups than information that is cross-cutting—consistent with the interests of only one of two groups with which they identify. Because ideological labels are more consistently meaningful among whites than Blacks and Hispanics (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010; Jefferson 2020), these effects should be particularly strong among white respondents. Table 3 already revealed that ideology, ethnoracial group, and partisanship remain significant predictors even when controlling for the effects of the other identities, and that there is an overlap between ideology and ethnoracial membership: Blacks and Hispanics tend to be more liberally biased than whites, and liberals are more biased toward Black and Hispanic interests than conservatives. To test H3, we replicated the models in table 3, adding an interaction term between the ideology and ethnoracial variables (see Supplementary Material table SM.3). Figures 2 and 3 provide an interpretation of the results of these interactive models, displaying the marginal effects of a respondent’s ideology/ethnoracial membership—depending on their ethnoracial/ideological group—on the ideological statements scale (figure 2) and ethnoracial statements scale (figure 3). Here, again, respondents’ partisanship is included in the models, confirming both that partisanship influences our dependent variables and that ideology and ethnoracial membership shape interpretations of political information even when controlling for partisanship.7

Figure 2.

Marginal effects of ideology on the ideological statements scale, by ethnoracial identity. Figure presents the marginal effects (and 95 percent confidence intervals) of a respondent’s ideology—dependent on their ethnoracial group—on the ideological statements scale. Effects estimated from Model 1 of Supplementary Material table SM.3, which interacts the ideology and ethnoracial variables.

Figure 3.

Marginal effects of ethnoracial identity on the ethnoracial statements scale, by ideology. Figure presents the marginal effects (and 95 percent confidence intervals) of a respondent’s ethnoracial group—dependent on their ideology—on the ethnoracial statements scale. Effects estimated from Model 2 of Supplementary Material table SM.3, which interacts the ideology and ethnoracial variables.

We find evidence supporting H3 for both dependent variables. Figure 2 shows that when classifying statements on our ideological scale, being white and conservative yields an interpretation most in line with conservative ideology, while being Black and liberal produces a classification most consistent with liberal ideological interests. These groups have a predicted difference in their classification of more than one of the 10 statements in this scale. In addition, having cross-cutting identities moderates the effect of ideology on classifying statements on the ideological scale. As the non-overlapping confidence intervals indicate, conservative Black and Hispanic respondents are less likely to use the conservative lens when interpreting statements than are conservative whites, and liberal white respondents are less likely to use the liberal lens when interpreting statements than are liberal Black respondents.

Similar patterns, confirming H3, can be seen in figure 3, which displays the effects of interacted ideological and ethnoracial identity on a respondent’s position on the ethnoracial statements scale. Again, conservative whites, whose identities align, stand out in classifying the statements most consistently with white interests while Black and Hispanic liberals classify statements most consistently with ethnoracial minority interests—a difference between these groups of about 20 percent of the ethnoracial statements scale (just under one of the four statements). Further, as above, inconsistency between one’s ethnoracial group and ideology moderates the effects of identity, with ethnoracial membership leading ideology in shaping news interpretation (except for among white liberals). Clear distinctions emerge between how white conservatives interpret statements on the ethnoracial scale—more in line with white interests—and how Black and Hispanic conservatives interpret these statements—in both cases more in line with ethnoracial minority group interests.

The findings in figures 2 and 3 are partly consistent with literature indicating less understanding or use of liberal and conservative ideological labels among Hispanic and Black Americans than white Americans (Abrajano and Alvarez 2010; Jefferson 2020). The gaps in classification of statements on our ideological and ethnoracial scales between liberals, moderates, and conservatives are larger and more often statistically significant among white respondents than Black or (especially) Hispanic respondents. However, even if our interactive models suggest that ethnoracial membership is a more powerful driver of Hispanic and Black interpretations of the news, ideology also influences Black interpretations of political information, with Black liberals and Black conservatives positioned significantly differently on both scales.

Discussion

News consumers are not neutral: each person interprets the news through the lens of their identity. In this article, we have shown that ideology and ethnoracial membership shape these interpretations. Respondents more often classify news statements favorable to their ideological and ethnoracial ingroups as facts and news detrimental to their ingroups as opinions. Furthermore, these identities interact, though differently for Black, Hispanic, and white respondents.

We find that liberal and conservative whites interpret the news in particularly distinct ways, while ethnoracial identity is a more significant driver of interpretations of the news among Black and Hispanic respondents. Thus, Black and Hispanic respondents generally interpret statements to favor liberal and ethnoracial minority interests more often than whites, independently of ideology, while white respondents’ positions on the two scales depend greatly on ideology. Additionally, our results indicate that the combination of conservative and white identities particularly distorts individuals’ perceptions of the news, especially on statements related to ethnoracial minorities which white conservatives most often incorrectly classify. And, perhaps unexpectedly given looser attachment to ideological labels among Blacks and Hispanics, ideology also shapes the way Black (and, less so, Hispanic) respondents understand political information. Black conservatives are significantly less biased toward liberal and ethnoracial minority interpretations of the news than Black liberals.

Expanding on previous literature, we thus confirm that party identification matters, but we advance previous research by showing that ideology and ethnoracial membership are also key lenses through which people see the world. Our findings regarding the effects of ethnoracial identity on news interpretation will be of particular import to future research on identity, public opinion, and political communication. Little existing literature has examined the relationship between ethnoracial identity and people’s (mis)information, especially looking beyond opinions about candidates. We show that white, Black, and Hispanic identities each affect the way people interpret the news—about both political figures and policies. This finding helps explain the racial gaps evident in interpretations of recent events, from Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the killing of George Floyd (Pew Research Center 2020a) to patterns in COVID-19 hospitalizations (Pew Research Center 2020b). Further, while our data constrain us to measuring only the effects of ethnoracial classification on behavior, this article paves the way for future studies examining the effects of racial identity strength, group consciousness, and racial resentment/sympathy. They might find even stronger effects of these racial identities and attitudes on information processing.

Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to distinguish genuine misinformation from expressive responding. However, the survey we use asked respondents to classify statements as facts or opinions regardless of whether they agreed with or believed the statements. This framing emphasized neutrality and therefore likely attenuated the effects of identity on interpretations of the news. We cannot be sure that this wording precludes interviewees from expressive responding, though some evidence suggests this is not widespread in our data.8 Most importantly, outside the survey world, the average news consumer may well be encouraged to interpret the news through their identity lenses due to media and politician framing. To the extent that politicians or media sources frame news statements in light of ideological or ethnoracial group identities, threats, and grievances, our findings likely understate the magnitude of American news consumers’ polarized understandings of the political world.

Data Availability Statement

REPLICATION DATA AND DOCUMENTATION are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BJUKYY.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL may be found in the online version of this article: https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab038.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We discuss race, ethnicity, and combinations of racial and ethnic identities, and thus use “ethnoracial” (Omi and Winant 2014) to characterize ethnic and racial membership.

Respondents are explicitly asked to disregard their beliefs, which poses a hard test to our hypotheses.

While individuals may personally identify with both a racial group (e.g., Black, white) and the Hispanic panethnic group, and these intersecting identities almost certainly shape their perceptions of political information, the racial coding available in the dataset used here splits respondents by their racial and ethnic identities without these intersections. Thus, we are constrained to comparing white non-Hispanic respondents, Black non-Hispanic respondents, and Hispanic respondents, and controlling for a non-Hispanic other ethnoracial group, each coded as mutually exclusive categories (see Supplementary Material).

We reverse-coded all conservative items so that 1 means the statement is not classified correctly by the respondent, in order to orient all items in the scale such that higher numbers indicate liberal ideological alignment.

We reverse-coded Muslim (the only item on the ethnoracial scale where a correct answer is more in line with white than Black or Hispanic interests): it is coded 1 if it is classified incorrectly by the respondents, so that all items in the scale are coded with higher numbers indicating alignment with Black or Hispanic interests.

Replicating all models with a (continuous) five-point ideology variable does not change the results.

Supplementary Material figures SM.1 and SM.2 replicate figures 2 and 3 for party rather than ideology and confirm that while partisanship does affect interpretations of political statements, it does so to a similar degree as ideological identity.

To test for expressive responding (“whereby individuals intentionally provide misinformation to survey researchers as a way of showing support for their political viewpoint”; see Schaffner and Luks 2018, p. 136), we analyze the relationship between political awareness and incorrect classification of the Obama’s birth statement—one especially likely to be subject to expressive responding—among conservatives. If conservative respondents with high political awareness were more likely to classify the statement incorrectly than conservative respondents with low political awareness, this would suggest expressive responding (as in Schaffner and Luks 2018). Our results do not support this hypothesis (see Supplementary Material, figure SM.3).

References

- Abrajano Marisa, Michael Alvarez R.. 2010. New Faces, New Voices. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abrajano Marisa, Hajnal Zoltan L.. 2015. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Michelle. 2012. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Allison M., Hunt Linda M.. 2016. “Counterproductive Consequences of a Conservative Ideology: Medicaid Expansion and Personal Responsibility Requirements.” American Journal of Public Health 106(7):1181–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks Antoine J., Hicks Heather M.. 2016. “Fear and Implicit Racism: Whites’ Support for Voter ID Laws.” Political Psychology 37(5):641–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Matt A., Pedraza Francisco I.. 2009. “The Renewal and Persistence of Group Identification in American Politics.” Electoral Studies 28(4):595–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels Larry M. 2002. “Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions.” Political Behavior 24(2):117–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bolsen Toby, Druckman James N., Cook Fay Lomax. 2014. “The Influence of Partisan Motivated Reasoning on Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 36(2):235–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer Marilynn B., Pierce Kathleen P.. 2005. “Social Identity Complexity and Outgroup Tolerance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31(3):428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Clem, Manza Jeff, Cohen Emma D.. 2016. “Political Ideology and Immigrant Acceptance.” Socius 2:1–12. 10.1177/2378023116668881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Dean Khalilah L. 2019. Identity Politics in the United States. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock John. 2007. “Experiments on Partisanship and Public Opinion: Party Cues, False Beliefs, and Bayesian Updating.” Unpublished PhD dissertation, Stanford University.

- Carlson Tucker. 2019. “Tucker: Left, Liberal Media Want Fox News Gone.” https://video.foxnews.com/v/6013242116001#sp=show-clips.

- Carter Niambi Michele. 2019. American While Black: African Americans, Immigration, and the Limits of Citizenship. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chong Dennis, Rogers Reuel. 2005. “Racial Solidarity and Political Participation.” Political Behavior 27(4):347–74. [Google Scholar]

- Converse Philip E. 1964. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” In Ideology and Its Discontents, edited by Apter David. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. [Google Scholar]

- Cook Elizabeth Adell, Jelen Ted, Wilcox Clyde. [1992] 2018. Between Two Absolutes: Public Opinion and the Politics of Abortion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deichert Maggie A., Goggin Stephen N., Theodoridis Alexander G.. 2018. “God, Sex, and Especially Politics: Disentangling the Dimensions of Discrimination.” Working Paper, August 14. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/94cb/e2b3d5729e707fea61d94c69070a2e94f6ca.pdf.

- Dowe Pearl K. Ford. 2016. “African American Women: Leading Ladies of Liberal Politics.” In Distinct Identities: Minority Women in U.S. Politics, edited by Brown Nadia and Gershon Sarah Allen, 49–62. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Druckman James N., Peterson Erik, Slothuus Rune. 2013. “How Elite Partisan Polarization Affects Public Opinion Formation.” American Political Science Review 107(1):57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Egan Patrick J. 2020. “Identity as Dependent Variable: How Americans Shift Their Identities to Align with Their Politics.” American Journal of Political Science 64(3):699–716. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Christopher, Stimson James A.. 2012. Ideology in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Farley Robert. 2019. “The Facts on White Nationalism.” FactCheck.Org (blog). March 20. https://www.factcheck.org/2019/03/the-facts-on-white-nationalism/.

- FBI. 2018. “Hate Crime Statistics.” Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/publications.

- Flynn D. J., Krupnikov Yanna. 2019. “Misinformation and the Justification of Socially Undesirable Preferences.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 6(1):5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn D. J., Nyhan Brendan, Reifler Jason. 2017. “The Nature and Origins of Misperceptions: Understanding False and Unsupported Beliefs About Politics.” Political Psychology 38(S1):127–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga Luis R., Garcia John A., Hero Rodney E., Jones-Correa Michael, Martinez-Ebers Valerie, Segura Gary M.. 2011. Latinos in the New Millennium: An Almanac of Opinion, Behavior, and Policy Preferences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gearan Anne, McGinley Laurie, Bernstein Lenny, Cha Ariana Eunjung. 2020. “Trump Says He Is Taking Hydroxychloroquine to Protect against Coronavirus, Dismissing Safety Concerns.” Washington Post, May 18. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-says-he-is-taking-hydroxychloroquine-to-protect-against-coronavirus-dismissing-safety-concerns/2020/05/18/7b8c928a-9946-11ea-ac72-3841fcc9b35f_story.html.

- Goff Phillip Atiba, Eberhardt Jennifer L., Williams Melissa J., Jackson Matthew Christian. 2008. “Not Yet Human: Implicit Knowledge, Historical Dehumanization, and Contemporary Consequences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94(2):292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hout Michael. 1999. “Abortion Politics in the United States, 1972–1994: From Single Issue to Ideology.” Gender Issues 17(2):3–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddy Leonie. 2013. “From Group Identity to Political Cohesion and Commitment.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by Huddy Leonie, Sears David, Levy Jack. 737–73. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy Leonie, Feldman Stanley. 2009. “On Assessing the Political Effects of Racial Prejudice.” Annual Review of Political Science 12(1):423–47. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy Leonie, Mason Lilliana, Horwitz S. Nechama. 2016. “Political Identity Convergence: On Being Latino, Becoming a Democrat, and Getting Active.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2(3):205–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jardina Ashley. 2019a. “White Consciousness and White Prejudice: Two Compounding Forces in Contemporary American Politics.” The Forum 17(3):447–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jardina Ashley. 2019b. White Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jardina Ashley, Traugott Michael. 2019. “The Genesis of the Birther Rumor: Partisanship, Racial Attitudes, and Political Knowledge.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 4(1):60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Hakeem. 2020. “The Curious Case of Black Conservatives: Construct Validity and the 7-Point Liberal-Conservative Scale.” Working Paper, May. Available at 10.2139/ssrn.3602209. [DOI]

- Jefferson Hakeem, Neuner Fabian, Pasek Josh. 2020. “Seeing Blue in Black and White: Race and Perceptions of Officer-Involved Shootings.” Working Paper, June. Available at https://www.dropbox.com/s/8uvb9lfk9pelpsd/Seeing%20Blue%20in%20Black%20and%20White_June2020.pdf?dl=0.

- Jerit Jennifer, Barabas Jason. 2012. “Partisan Perceptual Bias and the Information Environment.” Journal of Politics 74(3):672–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kahan Dan M. 2013. “Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection.” Judgment and Decision Making 8(4):407–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmoe Nathan P. 2020. “Uses & Abuses of Ideology in Political Psychology.” Political Psychology 41(4):771–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kam Cindy D. 2007. “Implicit Attitudes, Explicit Choices: When Subliminal Priming Predicts Candidate Preference.” Political Behavior 29(3):343–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder Donald, Kam Cindy. 2010. Us Against Them: Ethnocentric Foundations of American Opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder Donald, Kalmoe Nathan. 2017. Neither Liberal nor Conservative: Ideological Innocence in the American Public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder Donald, Ryan Timothy. 2017. “Prejudice and Politics Re-Examined: The Political Significance of Implicit Racial Bias.” Political Science Research and Methods 5(2):241–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff George. 2010. Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Le Danvy, Arora Maneesh, Stout Christopher. 2020. “Are You Threatening Me? Asian-American Panethnicity in the Trump Era.” Social Science Quarterly 101(6):2183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebo Matthew J., Cassino Daniel. 2007. “The Aggregated Consequences of Motivated Reasoning and the Dynamics of Partisan Presidential Approval.” Political Psychology 28(6):719–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Taeku. 2008. “Race, Immigration, and the Identity-to-Politics Link.” Annual Review of Political Science 11(1):457–78. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardelli Geoffrey J., Pickett Cynthia L., Brewer Marilynn B.. 2010. “Optimal Distinctiveness Theory: A Framework for Social Identity, Social Cognition, and Intergroup Relations.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by Zanna Mark P., Olson James M., vol. 43, 63–113. Cambridge: Academic Press. 10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43002-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge Milton, Hamill Ruth. 1986. “A Partisan Schema for Political Information Processing.” American Political Science Review 80(2):505–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge Milton, Taber Charles S.. 2013. The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Gustavo, Radford Jynnah. 2017. “Facts on U.S. Immigrants, 2015.” Pew Research Center. Available at http://www.pewhispanic.org/2017/05/03/facts-on-u-s-immigrants/.

- Lopez Linda, Pantoja Adrian D.. 2004. “Beyond Black and White: General Support for Race-Conscious Policies Among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans and Whites.” Political Research Quarterly 57(4):633–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Fan, Jones Bradford. 2019. “Effects of Belief versus Experiential Discrimination on Race-Based Linked Fate.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7(3):615–24. [Google Scholar]

- Malka Ariel, Lelkes Yphtach. 2010. “More Than Ideology: Conservative–Liberal Identity and Receptivity to Political Cues.” Social Justice Research 23(2):156–88. [Google Scholar]

- Maltby Elizabeth, Rocha Rene R., Jones Bradford, Vannette David L.. 2020. “Demographic Context, Mass Deportation, and Latino Linked Fate.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 5(3):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mangum Maurice. 2007. “Unpacking the Black Utility Heuristic: Explaining Black Identification with the Democratic Party.” American Review of Politics 28(April):37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Lilliana. 2016. “A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80(S1):351–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Lilliana. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mason Lilliana, Wronski Julie. 2018. “One Tribe to Bind Them All: How Our Social Group Attachments Strengthen Partisanship.” Political Psychology 39:257–77. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie. 2006. “Together They Become One: Examining the Predictors of Panethnic Group Consciousness Among Asian Americans and Latinos.” Social Science Quarterly 87(5):993–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka Natalie, Junn Jane. 2013. The Politics of Belonging: Race, Public Opinion, and Immigration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. 2016. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meirick Patrick C., Bessarabova Elena. 2016. “Epistemic Factors in Selective Exposure and Political Misperceptions on the Right and Left.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 16(1):36–68. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Joanne M., Saunders Kyle L., Farhart Christina E.. 2016. “Conspiracy Endorsement as Motivated Reasoning: The Moderating Roles of Political Knowledge and Trust.” American Journal of Political Science 60(4):824–44. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Kevin P., Brewer Marilynn B., Arbuckle Nathan L.. 2009. “Social Identity Complexity: Its Correlates and Antecedents.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12(1):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Travis. 2016. “Republicans Prefer Blunt Talk About Islamic Extremism, Democrats Favor Caution.” Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project (blog). February 3, 2016. https://www.pewforum.org/2016/02/03/republicans-prefer-blunt-talk-about-islamic-extremism-democrats-favor-caution/.

- Nincic Miroslav, Ramos Jennifer M.. 2010. “Ideological Structure and Foreign Policy Preferences.” Journal of Political Ideologies 15(2):119–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan Brendan, Reifler Jason. 2010. “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32(2):303–30. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor Cailin, Weatherall James Owen. 2019. The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread. Edición: 1. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen Marvin E. 1970. “Social and Political Participation of Blacks.” American Sociological Review 35(4):682–97. [Google Scholar]

- Omi Michael, Winant Howard. 2014. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Christopher S., Sawyer Mark Q., Towler Christopher. 2009. “A Black Man in the White House? The Role of Racism and Patriotism in the 2008 Presidential Election.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 6(1):193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pasek Josh, Stark Tobias H., Krosnick Jon A., Tompson Trevor. 2015. “What Motivates a Conspiracy Theory? Birther Beliefs, Partisanship, Liberal-Conservative Ideology, and Anti-Black Attitudes.” Electoral Studies 40(December):482–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Efrén. 2016. Unspoken Politics: Implicit Attitudes and Political Thinking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Efrén. 2021. “(Mis)Calculations, Psychological Mechanisms, and the Future Politics of People of Color.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 6(1):33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2014. “Political Polarization in the American Public.” Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2014/06/12/section-1-growing-ideological-consistency/.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. “The Partisan Divide on Political Values Grows Even Wider.” Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/05/the-partisan-divide-on-political-values-grows-even-wider/.

- Pew Research Center. 2018. “Distinguishing Between Factual and Opinion Statements in the News.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog), June 18. https://www.journalism.org/2018/06/18/distinguishing-between-factual-and-opinion-statements-in-the-news/.

- Pew Research Center. 2020a. “Majorities Across Racial, Ethnic Groups Express Support for the Black Lives Matter Movement.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project (blog), June 12. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/06/12/amid-protests-majorities-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-express-support-for-the-black-lives-matter-movement/.

- Pew Research Center. 2020b. “Views on Why Black Americans Face Higher COVID-19 Hospitalization Rates Vary by Party, Race and Ethnicity.” Pew Research Center (blog), June 26. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/26/views-on-why-black-americans-face-higher-covid-19-hospitalization-rates-vary-by-party-race-and-ethnicity/.

- Philpot Tasha S. 2017. Conservative but Not Republican: The Paradox of Party Identification and Ideology among African Americans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Mark D., Peterson David A. M.. 2020. Ignored Racism: White Animus Toward Latinos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel. 2006. “The Role of Group Consciousness in Latino Public Opinion.” Political Research Quarterly 59(3):435–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel. 2008. “Latino Group Consciousness and Perceptions of Commonality with African Americans.” Social Science Quarterly 89(2):428–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Gabriel, Masuoka Natalie. 2010. “Brown-Utility Heuristic? The Presence and Contributing Factors of Latino Linked Fate.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 32(4):519–31. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner Brian F., Luks Samantha. 2018. “Misinformation or Expressive Responding?” Public Opinion Quarterly 82(1):135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut Deborah J. 2017. “White Attitudes about Descriptive Representation in the US: The Roles of Identity, Discrimination, and Linked Fate.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 5(1):84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder Elizabeth, Stone Daniel F.. 2015. “Fox News and Political Knowledge.” Journal of Public Economics 126(June):52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sears David O., Lau Richard R., Tyler Tom R., Allen Harris M.. 1980. “Self-Interest vs. Symbolic Politics in Policy Attitudes and Presidential Voting.” The American Political Science Review 74(3):670–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius James, Levin Shana, Van Laar Colette, Sears David O.. 2008. The Diversity Challenge: Social Identity and Intergroup Relations on the College Campus. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Sides John, Tesler Michael, Vavreck Lynn. 2018. Identity Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Southwell Brian G., Thorson Emily A., Sheble Laura, eds. 2018. Misinformation and Mass Audiences. https://utpress.utexas.edu/books/southwell-thorson-sheble-misinformation-and-mass-audiences.

- Stokes‐Brown Atiya Kai. 2012. “America’s Shifting Color Line? Reexamining Determinants of Latino Racial Self-Identification.” Social Science Quarterly 93(2):309–32. [Google Scholar]

- Taber Charles S., Lodge Milton. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50(3):755–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel Henri. 1974. “Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour.” Information (International Social Science Council) 13(2):65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tate Katherine. 1994. From Protest to Politics: The New Black Voters in American Elections. New York: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tesler Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial? Race and Politics in the Obama Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Theiss-Morse Elizabeth. 2009. Who Counts as an American?: The Boundaries of National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoridis Alexander G. 2017. “Me, Myself, and (I), (D), or (R)? Partisanship and Political Cognition through the Lens of Implicit Identity.” Journal of Politics 79(4):1253–67. 10.1086/692738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trump Donald. 2019. “So Surprised to See Conservative Thinkers…” March 5. Available at https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1124454991341793281.

- Valentino Nicholas A., Neuner Fabian G., Vandenbroek L. Matthew. 2018. “The Changing Norms of Racial Political Rhetoric and the End of Racial Priming.” Journal of Politics 80(3):757–71. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Edward D., Sanchez Gabriel R., Valdez Juan A.. 2017. “Immigration Policies and Group Identity: How Immigrant Laws Affect Linked Fate among U.S. Latino Populations.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 2(1):35–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Steven W., Abramowitz Alan I.. 2017. “The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the U.S. Electorate.” American Politics Research 45(4):621–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks Brian E. 2015. “Emotions, Partisanship, and Misperceptions: How Anger and Anxiety Moderate the Effect of Partisan Bias on Susceptibility to Political Misinformation.” Journal of Communication 65(4):699–719. [Google Scholar]

- White Ismail, Laird Chryl. 2020. Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong Janelle S. 2018. Immigrants, Evangelicals, and Politics in an Era of Demographic Change. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Yadon Nicole, Piston Spencer. 2019. “Examining Whites’ Anti-Black Attitudes after Obama’s Presidency.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7(4):794–814. [Google Scholar]

- Yen Steven T., Zampelli Ernest M.. 2017. “Religiosity, Political Conservatism, and Support for Legalized Abortion: A Bivariate Ordered Probit Model with Endogenous Regressors.” Social Science Journal 54(1):39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zepeda-Millán Chris. 2017. Latino Mass Mobilization: Immigration, Racialization, and Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

REPLICATION DATA AND DOCUMENTATION are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BJUKYY.