Abstract

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contains an elaborate protein quality control network that promotes protein folding and prevents accumulation of misfolded proteins. Evolutionarily conserved UBIQUITIN-ASSOCIATED DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 2 (UBAC2) is involved in ER-associated protein degradation in metazoans. We have previously reported that two close UBAC2 homologs from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) not only participate in selective autophagy of ER components but also interact with plant-specific PATHOGEN-ASSOCIATED MOLECULAR PATTERN (PAMP)-INDUCED COILED COIL (PICC) protein to increase the accumulation of POWDERY MILDEW-RESISTANT 4 callose synthase. Here, we report that UBAC2s also interacted with COPPER (Cu) TRANSPORTER 1 (COPT1) and plasma membrane-targeted members of the Cu transporter family. The ubac2 mutants were significantly reduced in both the accumulation of COPT proteins and Cu content, and also displayed increased sensitivity to a Cu chelator. Therefore, UBAC2s positively regulate the accumulation of COPT transporters, thereby increasing Cu uptake by plant cells. Unlike with POWDERY MILDEW RESISTANCE 4, however, the positive role of UBAC2s in the accumulation of COPT1 is not dependent on PICC or the UBA domain of UBAC2s. When COPT1 was overexpressed under the CaMV 35S promoter, the increased accumulation of COPT1 was strongly UBAC2-dependent, particularly when a signal peptide was added to the N-terminus of COPT1. Further analysis using inhibitors of protein synthesis and degradation strongly suggested that UBAC2s stabilize newly synthesized COPT proteins against degradation by the proteasome system. These results indicate that plant UBAC2s are multifunctional proteins that regulate the degradation and accumulation of specific ER-synthesized proteins.

Two endoplasmic reticulum-resident UBIQUITIN-ASSOCIATED DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 2s play an important role in copper accumulation through interacting COPT copper transporters and modulating their accumulation.

Introduction

About one-third of all cellular proteins in eukaryotic cells are secretory/membrane proteins that function in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the Golgi apparatus, the lysosome/vacuole, the plasma membrane, and the extracellular space (Benham, 2012). During or upon synthesis on cytosolic ribosomes, secretory/membrane proteins are directed by specific signal sequences for import into the ER for folding, modification, and trafficking (Benham, 2012). Because protein folding is an error-prone process, the ER contains complex protein folding and quality control networks (Adams et al., 2019). When unfolded nascent protein chains first enter the ER, its hydrophobic sequences are bound by heat-shock protein chaperones to promote folding (Adams et al., 2019). Protein disulfide isomerases and the oxidative environment of the ER help catalyze the formation of disulfide bonds in the proteins (Adams et al., 2019). At the same time, the majority of the proteins that enter the ER are appended en bloc with a GlcNAc2Man9Gluc3 glycan to the Asn residue in the Asn-X-Ser/Thr motif (where X is any amino acid except proline; Adams et al., 2019). The glycan appendage enhances protein solubility and promotes folding and trafficking of the glycoproteins. The N-linked glycans also act as reporters of the folded state and age of the glycoproteins. After glycosylation, the first and second glucose of the glycan are trimmed by α-glucosidases I and II, respectively, generating a glycan with one glucose, which is bound by lectin chaperones calnexin and calreticulin to promote further folding (Adams et al., 2019). The last glucose is then trimmed by α-glucosidase II to yield a nonglucosylated glycan that supports release of the glycoprotein from calnexin and calreticulin so the protein can be further trafficked through the secretory pathway if it is correctly folded. Incorrectly folded proteins can be reglucosylated and returned to the calnexin/calreticulin cycle for continued folding (Adams et al., 2019). Those proteins that are incapable of reaching their native fold are subjected to ER-associated degradation (ERAD).

ERAD is a cellular pathway in eukaryotic cells that targets misfolded ER proteins for degradation by the proteasome (Berner et al., 2018). The first step of ERAD is recognition of terminally misfolded protein substrates, which is not completely understood but most likely involves targeting of the nonglucosylated GlcNAc2Man9 glycan by ER mannosidases that generate specific glycosylation signatures as an ERAD signal (Berner et al., 2018). The recognized luminal protein substrates then need to traverse the ER retrotranslocation pore formed by the membrane-embedded ubiquitin E3 ligase 3-HYDROXY-3-METHYLGLUTARYL-COENZYME A REDUCTASE DEGRADATION 1 (Hrd1), which in yeast forms a complex with three other membrane proteins (Hrd3, U1 SMALL NUCLEAR RIBONUCLEOPROTEIN 1-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 1 and DERLIN 1) and the lumen-soluble YEAST OSTEOSARCOMA AMPLIFIED 9 HOMOLOG (Berner et al., 2018). On the cytosolic side, the protein substrates are ubiquitinated and degraded by the 26S proteasome. In mammalian cells, Hrd1 E3 ligase has a close homolog gp78, which is also involved in ERAD (Berner et al., 2018). Despite its sequence similarity to Hrd1, gp78 interacts with a different set of proteins including UBIQUITIN-ASSOCIATED (UBA) DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 2 (UBAC2; Christianson et al., 2012). While Hrd1 plays an essential role in retrotranslocation and ubiquitination of ERAD substrates, the gp78 E3 ligase complex appears to act downstream of Hrd1 and assist Hrd1 during retrotranslocation (Zhang et al., 2015). Recently, it has been shown that Gp78 and associated UBAC2 are involved in the attenuation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling important for immune system development in lymphocytes by promoting degradation of ER-localized Wnt receptors FZD and LRP6 (Choi et al., 2019). The polymorphism of the UBAC2 gene is related to Behcet’s disease, a rare inflammation disorder in blood vessels (Sawalha et al., 2011; Hou et al., 2012; Yamazoe et al., 2017). UBAC2 is also closely related to the occurrence and development of skin and bladder cancers (Nan et al., 2011; Hedegaard et al., 2016; Gu et al., 2020). The association of gp78 and UBAC2 with a variety of human disorders underscores the important physiological roles of the ERAD pathway.

UBAC2 is a highly conserved protein found in different species including plants (Zhou et al., 2018). We have previously reported that two close homologs of mammalian UBAC2 in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) play an important role in plant heat tolerance and resistance to necrotrophic pathogens by interacting with plant-specific ATG8-INTERACTING PROTEINS 3 (ATI3) autophagy receptors and mediating selective autophagy of specific ER components (Zhou et al., 2018). We have also recently reported that Arabidopsis UBAC2s interact with the plant-specific PATHOGEN-ASSOCIATED MOLECULAR PATTERN-INDUCED COILED COIL (PICC) protein, which is also localized in the ER (Wang et al., 2019). UBAC2 and PICC proteins coordinately regulate the accumulation of the POWDERY MILDEW-RESISTANT 4 (PMR4) callose synthase and play a critical role in pathogen-induced callose deposition and plant immunity (Wang et al., 2019). A positive role of UBAC2s in PMR4 accumulation is dependent on its UBA domain. Given the critical role of the UBA domain and the established function of UBAC2 in ERAD, it is possible that plant UBAC2s target the degradation of a negative regulator of PMR4 stability to promote PMR4 accumulation (Wang et al., 2019). Here, we report that UBAC2s also interact directly with COPPER (Cu) TRANSPORTER 1 (COPT1) and two other plasma membrane-targeted members of the COPT Cu transporter family. The ubac2 mutants were reduced in Cu content and were more sensitive to a Cu chelator, indicating a role of UBAC2s in Cu uptake. The modulation of Cu content by UBAC2s was associated with its positive role in the COPT transporter protein accumulation. However, unlike their roles with PMR4, UBAC2s’ promotion of COPT1 protein accumulation was not dependent on PICC or the UBA domain of UBAC2s. Further analysis using COPT1 and UBAC2 variants in combination with protein synthesis and degradation inhibitors strongly suggests that the ER-localized UBAC2 proteins directly bind newly synthesized COPT proteins to stabilize them against degradation by the proteasome system. These results indicate that plant UBAC2 proteins have important and complex roles in the regulation of the fate of specific ER-synthesized proteins through distinct pathways and mechanisms that are unknown with their mammalian homologs.

Results

ER-localized UBAC2 proteins interact with COPT Cu transporters

Using yeast two-hybrid screens with UBAC2a as a bait, we have previously identified positive clones encoding UBAC2-interacting proteins, one of which is the plant-specific PICC protein (Wang et al., 2019). We have reported that UBAC2 and PICC proteins coordinately regulate the biogenesis of the PMR4 callose synthase and play a critical role in pathogen-induced callose deposition and immunity (Wang et al., 2019). Among other positive clones encoding UBAC2-interacting proteins, three match Arabidopsis loci At5g59030, which encodes COPT1, a plasma membrane-localized high-affinity Cu transporter (Figure 1A;Sancenon et al., 2004). Other two clones match At1g52200, which encodes PLANT CADMIUM RESISTANCE8 (PCR8), a protein belonging to a family of proteins containing the CCXXXXCPC or CLXXXXCPC PLAC8 motif. In Arabidopsis, PLAC8 motif-containing proteins include PCR1 and PCR2, whose overexpression led to increased cadmium tolerance in both yeast and plants (Song et al., 2004). Transport experiments and structural modeling indicate that PCR1 and PCR2 proteins act as transporters of cadmium and zinc (Song et al., 2010). Despite its structural similarity, Arabidopsis PCR8 does not confer increased cadmium resistance when overexpressed in yeast cells, indicating that it may play a role in the transport of other metal ions (Song et al., 2010). This study will focus on UBAC2-interacting COPT proteins because of their established role in Cu transport.

Figure 1.

Interaction of UBAC2 proteins with COPT1 in yeast and plant cells. A, Yeast two-hybrid assay of UBAC2a-COPT1 interaction. The Gal4 DNA binding domain vector (bait) with or without (−) fused UBAC2a gene were cotransformed with the activation domain vector (prey) with or without (−) fused COPT1 gene into yeast cells and the transformed cells were grown on the selection medium with (+) or without (−) His. B, BiFC assays of UBAC2a-COPT1 interactions in N. benthamiana. BiFC fluorescence was observed in the transformed N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells from complementation of the N-terminal half of the YFP fused with UBAC2a (UBAC2a-N-YFP) by the C-terminal half of the YFP fused with COPT1 (COPT1-C-YFP). No fluorescence was observed when COPT1-C-YFP was co-expressed with fused NBR1-N-YFP or unfused N-YFP or when unfused C-YFP was co-expressed with UBAC2a-N-YFP. YFP epifluorescence, bright-field, and merged images of the same cells are shown. Bar = 10 μm.

To determine whether UBAC2 and COPT1 interact in plant cells, we performed bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) in Agrobacterium-infiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana. We fused Arabidopsis UBAC2a to the N-terminal yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fragment (UBAC2a-N-YFP) and co-expressed it with COPT1-C-YFP in the leaves of N. benthamiana. As control, we also included in the assay the NBR1-N-YFP construct in which the Arabidopsis selective autophagy receptor NBR1 was fused to the N-terminal YFP fragment. BiFC signals were detected in transformed cells as a reticulum network pattern characteristic of the ER (Figure 1B). Control experiments in which NBR1-N-YFP or unfused N-YFP was co-expressed with COPT1-C-YFP or when UBAC2a-N-YFP was co-expressed with unfused C-YFP did not show fluorescence (Figure 1B). Thus, Arabidopsis UBAC2 and COPT1 interacted and formed complexes at the ER.

COPT1 is a relatively small protein of 170 amino acid residues predicted to contain three transmembrane domains (TMDs; Sancenon et al., 2004; Supplemental Figure S1). To determine the region of COPT1 important for its interaction with UBAC2a, we generated a series of truncated COPT1 protein constructs and tested them for interaction with UBAC2a using yeast two-hybrid assays. As shown in Figure 2, deletion of the N-terminal 20, 40, 60, or 80 residues of COPT1 completely abolished its interaction with UBAC2a. On the other hand, deletion of the C-terminal 20 amino acid residues had no effect on its interaction with UBAC2a (Figure 2). However, deletion of 50 or more amino acid residues from its C-terminus abolished its interaction with UBAC2a (Figure 2). Thus, COPT1 interaction with UBAC2a required a large N-terminal COPT1 sequence of more than 100 residues. Deletion of the N-terminal 20 residues of COPT1 also abolished its interaction with UBAC2a in plant cells based on BiFC assays (Supplemental Figure S2A). In the BiFC assays, deletion of the N-terminal 20 residues of COPT1 did not affect its accumulation in the leaves of N. benthamiana (Supplemental Figure S2B), indicating that failure to observe the BiFC signals was not caused by the reduced accumulation of the truncated COPT1 protein.

Figure 2.

Mapping of the UBAC2a-interacting domain of COPT1 using yeast two-hybrid assay. The yeast two-hybrid UBAC2a bait vector was cotransformed with prey vectors containing different truncated COPT1 gene fragments into yeast cells and the transformed cells were grown in the selection medium with (+) or without (−)His. The corresponding amino acid residues and the TMDs (black rectangles) for each truncated COPT1 gene fragment are shown.

COPT1 has five homologs in Arabidopsis (COPT2–6; Sancenon et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2012; Garcia-Molina et al., 2013). Sequence comparison shows that COPT2 and 6 are most similar to COPT1 with ∼60% amino acid sequence identity (Supplemental Figure S1). COPT3–5 are more distantly related to COPT1 with 40%–50% sequence identity (Supplemental Figure S1). Five of the six COPT proteins (COPT1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) are high-affinity Cu transporters that complement yeast Cu transporter (ctr) mutant (Sancenon et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2012; Garcia-Molina et al., 2013). COPT1, 2, and 6 are targeted to the plasma membrane for Cu uptake from the extracellular medium (Sancenon et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2012; Garcia-Molina et al., 2013), while COPT3 and 5 are localized in intracellular membranes (Sancenon et al., 2004; Garcia-Molina et al., 2011; Klaumann et al., 2011). COPT4 cannot complement the yeast ctr mutant and, therefore, appears to be not functional as a high-affinity Cu transporter (Sancenon et al., 2004). Using yeast two-hybrid assays, we analyzed whether UBAC2a also interacted with the other five members of the COPT protein family. Preliminary assays based on histidine (His) prototrophy showed that UBAC2a also interacted with COPT2 and 6 but not with the other three COPT proteins from Arabidopsis (Supplemental Figure S3). This finding was confirmed by the quantitative assays of β-galactosidase activity based on LacZ reporter gene expression (Figure 3). These results indicated that ER-localized UBAC2a interacted not only with COPT1 but also with COPT2 and 6 at reduced affinities based on the β-galactosidase activities (Figure 3). Likewise, UBAC2b interacted with COPT1, 2, and 6, but not with the other three Arabidopsis COPT proteins in yeast cells (Figure 3; Supplemental Figure S3). Thus, both UBAC2a and 2b interacted with the three plasma membrane-targeted COPT proteins in Arabidopsis.

Figure 3.

Interaction of UBAC2 proteins with members of the COPT protein family. The Gal4 binding domain fusion vector (bait) for UBAC2a or UBAC2b was cotransformed with the activation domain fusion vector (prey) of different COPT proteins into yeast cells. Proteins were isolated from the yeast cells and assayed for β-galactosidase activity using ONPG as substrate. Data represent means and standard errors (n = 5).

Significantly reduced COPT1 protein accumulation in the ubac2 mutant

As homologs of evolutionarily conserved UBACs involved in ERAD, Arabidopsis UBAC2 proteins may interact with plasma membrane-targeted COPT proteins to regulate their synthesis, folding, modification, and trafficking, which ultimately affect their accumulation and subcellular localization. To test this possibility, we examined the effects of the mutations of UBAC2s on the accumulation and subcellular localization of COPT1. For this purpose, we generated a COPT1-GFP fusion gene under control of the COPT1 native promoter (PCOPT1::COPT1-GFP) and introduced it into both Arabidopsis wild-type (WT) and the ubac2a/2b double mutant plants. Confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed that in the root and leaf cells of both WT and ubac2 mutant seedlings, a majority of the COPT1-GFP signals were localized at the plasma membrane with some signals also in intracellular space mostly with a reticulum ER network pattern (Supplemental Figure S4). Therefore, mutations of UBAC2s did not appear to affect the subcellular localization of COPT1. The intensities of COPT1-GFP signals, as an indicator of COPT1-GFP protein levels, were, in general, substantially higher in the transgenic WT lines than in the transgenic ubac2 mutant lines harboring the PCOPT1::COPT1-GFP construct (Supplemental Figure S4). However, likely due to positional effects of transgene integration at different genome sites, there was substantial variation in the intensities of GFP signals even among independent lines of the same genetic background, which complicated the comparison for assessing the effect of UBAC2 mutations on the protein levels of COPT1-GFP.

We also generated a myc-tagged COPT1 transgene under control of its native promoter (PCOPT1::COPT1-myc) and transformed it into both WT and ubac2a/2b mutant plants. Protein blotting using an anti-myc antibody revealed that the protein levels of myc-tagged COPT1 were substantially higher in WT than in the ubac2a/2b mutant background, but again there was substantial variation even among independent lines of the same genetic background (Supplemental Figure S5A). To avoid this problem, we generated transgenic lines that contained the PCOPT1::COPT1-myc transgene integrated at the same genome site but differed in the zygosity of the ubac2a/2b mutations. First, we selected two transgenic PCOPT1::COPT1-myc lines in the ubac2a/2b mutant background (lines 1 and 2) and crossed them with both WT and ubac2a/2b double mutant. The resulting two groups of F1 progeny for each line were heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− and homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− plants but contained a PCOPT1::COPT1-myc transgene integrated at the same genome site. The two types of F1 progeny for each of the two lines were then compared for the levels of COPT1-myc proteins by protein blotting. As shown in Figure 4, the protein levels of COPT1-myc in the homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− progeny were <40% of those in the heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny for both lines (Figure 4). Reverse transcription quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis showed that the two types of F1 progeny for each of the two lines contained very similar levels of COPT-myc transcripts (Figure 4B). These results indicated that the disruption of UBAC2 genes had a significant effect on the accumulation of COPT1 proteins.

Figure 4.

Disruption of UBAC2 genes significantly reduced accumulation of COPT1-myc under control of the native promoter. A, Protein blot analysis of COPT1-myc accumulation expressed under its native promoter. PCOPT1::COPT1-myc construct was first introduced into the ubac2a/2b mutant plants. Two independent transgenic lines (L1 and L2) were crossed to both the WT and ubac2a/2b mutant to generate two types of progeny for each line that contained the same PCOPT1::COPT1-myc transgene gene but differed in the zygosity of the ubac2a/2b mutations. The COPT1-myc protein levels in the two types of progeny for each line were compared by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Rubisco large subunit proteins stained with Ponceau S were used as loading control. B, Measurements of the levels of COPT1-myc proteins and COPT1-transcript. The relative levels of the COPT1-myc protein bands were determined from the immunoblots by ImageJ. Values are means of five samples ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the band density between the ubac2a/2b−/− and UBAC2a/2b+/−progeny calculated for each line using Student’s t test. The experiments were repeated twice with very similar results.

Strongly reduced accumulation of overexpressed COPT proteins in the ubac2 mutant

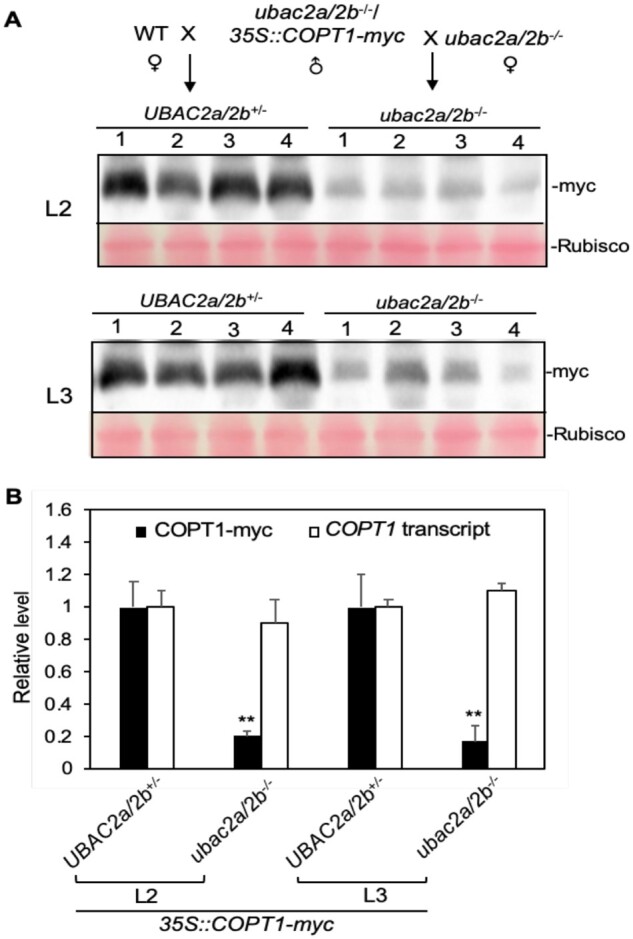

The protein quality control network in the ER promotes protein homeostasis through promotion of protein folding, timely recognition, and degradation of misfolded and aggregated proteins, which are influenced by protein level and structure (Gupta et al., 1998). To further gain insights into the role of UBAC2 in promoting COPT protein accumulation, we examined the effect of UBAC2 mutations on the accumulation of overexpressed COPT proteins. For this purpose, we generated a COPT1-myc construct under control of the strong CaMV 35S promoter (35S::COPT1-myc) and transformed it into both WT and ubac2a/2b mutant plants. Survey of these independent T1 transgenic lines by protein blot analysis showed that the protein levels of COPT1-myc in transgenic 35S::COPT1-myc lines were generally substantially higher in WT than those in the ubac2a/2b mutant (Supplemental Figure S5B). However, as often observed in transgene expression driven by the strong CaMV 35S promoter, there was a substantial variation among independent lines harboring the same construct in the same genetic background (Supplemental Figure S5B). Therefore, for more reliable comparison of COPT1-myc protein levels between WT and ubac2a/2b, we again crossed two independent single-copy transgenic 35S::COPT1-myc lines in the ubac2a/2b mutant background to both WT and ubac2a/2b mutant to generate both heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− and homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− progeny that contained the same 35S::COPT1-myc transgene (Figure 5A). Protein blot analysis revealed that for both lines, the levels of COPT1-myc proteins in the heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny were ∼5 times higher than those in the homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− progeny despite similar levels of COPT1-myc transcripts in the two genotypes (Figure 5). We also generated COPT2-myc and COPT6-myc overexpression constructs under the CaMV 35S promoter and found that the levels of the two myc-tagged COPT proteins were substantially higher in the WT background than in the ubac2 mutant background despite similar levels of their respective transcript levels (Supplemental Figure S6). Thus, the product accumulation of overexpressed COPT1, 2, and 6-myc transgenes was all strongly UBAC2-dependent.

Figure 5.

Disruption of UBAC2 genes significantly reduced accumulation of COPT1-myc under control of the CaMV 35S promoter. A, Protein blot analysis of COPT1-myc accumulation expressed under the CaMV 35S promoter. The 35S::COPT1-myc construct was first introduced into the ubac2a/2b mutant plants. Two independent transgenic lines (L2 and L3) were crossed to both the WT and ubac2a/2b mutant to generate two types of progeny for each line that contained the same 35S::COPT1-myc gene but differ in the zygosity of the ubac2a/2b mutations. The COPT1-myc protein levels in the two types of progeny for each line were compared by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Rubisco large subunit proteins stained with Ponceau S as loading control. B, Measurements of the levels of COPT1-myc proteins and COPT1-transcript. The relative densities of the COPT1-myc protein bands from the immunoblots were measured by ImageJ. Values are means of four bands ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the band density between the ubac2a/2b−/− and UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny calculated for each line using Student’s t test. The experiments were repeated twice with very similar results.

Role of UBAC2 in the accumulation of COPT1 with a N-terminal signal peptide

In eukaryotic cells, integral membrane proteins of cell surfaces such as Arabidopsis COPT1 are assembled at the ER. Most plasma membrane proteins contain either a cleavable signal peptide or a TMD at the N-terminus that is recognized upon exit from the ribosome and targeted to the ER by the signal recognition particle (SRP) through interaction with the SRP receptor (Benham, 2012). Arabidopsis plasma membrane-targeted COPT1 does not contain a cleavable N-terminal signal peptide. Its first TMD, which probably acts as its signal peptide, is preceded by a relatively large N-terminal domain of >60 amino acid residues (Supplemental Figure S1), which is predicted to contain an intrinsically disordered sequence (Supplemental Figure S7), and, therefore, has a high propensity of misfolding and interaction with other proteins upon emerging from the ribosomes during synthesis. To examine whether altered N-terminal structure of COP1 affects its accumulation, we inserted the signal peptide of tobacco (N. tabacum) PATHOGENESIS-RELATED 1 (PR1) protein at the N-terminus of COPT1 (SPPR1-COPT1-myc) and placed it behind the CaMV 35S promoter (35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc). The constructs were then transformed into WT and ubac2a/2b mutant plants and the T1 progeny were examined for the accumulation of COPT1-myc by protein blotting. As expected, high levels of COPT1-myc proteins were detected in the WT progeny harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc construct (Supplemental Figure S5C). Surprisingly, there was little accumulation of COPT1-myc proteins in the ubac2a/2b mutant plants harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc construct (Supplemental Figure S5C). To confirm the drastic effect of the UBAC2 mutations on SPPR1-COPT1-myc accumulation, we again selected two independent transgenic 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc lines in the ubac2a/2b mutant background and crossed with both WT and the ubac2a/2b mutant. Comparison of the COPT1-myc transcripts and COPT1-myc proteins were then made between the heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− and homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− lines containing the same 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene. As found in the ubac2a/2b parental mutant lines, little accumulation of COPT1-myc proteins was detected in the homozygous ubac2a/2b−/− progeny harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene (Figure 6). In contrast, high protein levels of COPT1-myc were detected in the heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny harboring the same transgene (Figure 6). RT-qPCR showed that the transcript levels of COPT1-myc in the ubac2a/2b mutant harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene were still >65% of those in the WT background (Figure 6B). Thus, the accumulation of a modified COPT1 protein with an N-terminal signal peptide was almost completely dependent on UBAC2 proteins.

Figure 6.

Little accumulation of COPT1-myc with a N-terminal signal peptide under control of the CaMV 35S promoter in the ubac2a/2b mutant. A, Protein blot analysis of COPT1-myc accumulation expressed from the SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene under the CaMV 35S promoter. The 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc construct was first introduced into the ubac2a/2b mutant plants. Two independent transgenic lines (L1 and L2) were crossed to both the WT and ubac2a/2b mutant to generate two types of progeny for each line that contained the same 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc gene but differ in the zygosity of the ubac2a/2b mutations. The protein levels of COPT1-myc in the two types of progeny for each line were compared by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Rubisco large subunit proteins stained with Ponceau S were used as loading control. The experiments were repeated twice with very similar results. B, Measurements of the levels of COPT1-myc proteins and COPT1-transcript. The relative densities of the COPT1-myc protein bands from the immunoblots were measured by ImageJ. Values are means of four bands ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the band density between the ubac2a/2b−/− and UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny calculated for each line using Student’s t test.

To determine whether expression of the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene generated functional COPT1-myc proteins, we first compared its molecular mass with that of COPT1-myc expressed from the 35S::COPT1-myc transgene using protein blotting. Despite the fact that SPPR1-COPT1-myc is ∼15% larger in molecular mass than COPT1-myc, side-by-side comparison revealed that the main COP1-myc protein bands from the SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgenic plants were of the same size of ∼24 kDa as those from the COPT1-myc transgenic plants (Supplemental Figure S8A), suggesting that the signal peptide of SPPR1-COPT1-myc was cleaved in WT plants. There were also similar minor products of larger sizes that could be due to posttranslational modifications or incomplete protein denaturation of the COPT1 trimeric protein complexes or aggregates. We also compared the Cu contents between a 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc lines and a 35S::COPT1-myc line that accumulated similar levels of COPT1-myc proteins and found that there were elevated to similar levels when compared to those in WT plants (Supplemental Figure S8B). Furthermore, the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1 seedlings became highly sensitive to increased Cu in the growth medium just like the 35S::COPT1 seedlings (Supplemental Figure S8C). Taken together, these results indicated that in WT background, the signal peptide of SP-COPT1 appeared to be removed and processed to generate a functional COPT1 protein. In the ubac2a/2b mutant background, however, the addition of the signal peptide renders the fusion protein highly unstable with little accumulation (Supplemental Figure S8A) and as a result, no significant elevation of Cu content (Supplemental Figure S8B) or sensitivity to elevated Cu (Supplemental Figure S8C) was observed in the transgenic ubac2a/2b mutant harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene.

Reduced Cu content and increased sensitivity to Cu chelator in the ubac2 mutants

Arabidopsis UBAC2 proteins physically interact with plasma membrane-targeted COPT1, 2, and 6 (Figure 3) and positively regulates the accumulation of COPT1, 2, and 6 (Figures 4–6; Supplemental Figures S5 and S6). These plasma membrane-targeted COPT1, 2, and 6 are involved in Cu uptake from the extracellular medium including root Cu uptake from soil (Sancenon et al., 2004; Jung et al., 2012; Garcia-Molina et al., 2013). Therefore, the loss of functional UBAC2s in the ubac2a/2b mutants could affect Cu accumulation as a result of reduced protein levels of the Cu transporters. To test this, we compared the Cu levels of 12-d-old seedlings of a ubac2a/2b double mutant with WT and a copt1 mutant. As shown in Figure 7, the Cu content in the root of the ubac2a/2b double mutant was reduced by ∼27% relative to those in WT root (Figure 7). The Cu content in the shoot of the ubac2a/2b mutants was also reduced by ∼25% when compared to those in WT plants (Figure 7). Therefore, the ubac2 mutants are compromised in Cu accumulation even when grown under normal conditions. On the other hand, the Cu levels in the root and shoot of the copt1 mutant were reduced by only 10% and 6%, respectively, when compared to those in WT seedlings (Figure 7). Similarly, Li et al. (2020) have recently reported that the Cu levels in both the root and shoot in a copt1 T-DNA insertion mutant were largely normal but the Cu levels in a copt1/2 double mutant were substantially reduced relative to those in WT, indicating functional redundancy among the plasma membrane-targeted Cu transporters in Cu uptake.

Figure 7.

Cu contents in WT and ubac2a/2b mutants. Roots and shoots of 12-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on 1/2 MS plates were harvested and determined for Cu contents using atomic absorption spectrometry. Values are means of three replicates ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the Cu content between a mutant and WT calculated using Student’s t test. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

The ubac2a/2b mutants grow normally under normal growth conditions despite their significantly reduced Cu levels. To test whether reduced Cu availability affects the growth of the ubac2a/2b mutants, we compared WT and ubac2a/2b mutants for sensitivity to bathocuproine disulfonic acid (BCS), a Cu chelator (Sancenon et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 8, in the absence of the Cu chelator, there was no significant difference in the root growth between WT and the ubac2a/2b mutants. In the presence of 100 µM BCS, the root growth of Col-0 WT seedlings was reduced by ∼10% when compared to those of untreated seedlings, while the roots length of the ubac2a/2b mutants were reduced by ∼40% (Figure 8). When the BCS concentration was increased to 150 µM, the root growth of Col-0 WT seedlings was reduced by ∼23% when compared to those of untreated WT seedlings, while the roots growth of the ubac2a/2b mutants were reduced by ∼45% (Figure 8). Therefore, at the higher BCS concentration, WT root growth was further reduced but again the ubac2a/2b mutants displayed even stronger reduction in root growth (Figure 8). These results indicated that the ubac2a/2b mutant seedlings were more sensitive to reduced Cu levels in the medium as a result of the presence of the Cu chelator. Despite only a slight reduction in the Cu content in the copt1 mutant under normal conditions, the extent of reduction in root growth of the copt1 mutant seedlings was similar to that of the ubac2a/2b mutant at both 100 and 150 µM BCS (Figure 8). As a major high-affinity Cu transporter in roots, the importance of COPT1 apparently becomes more prominent when the Cu levels in the growth medium are reduced with the addition of the Cu chelator. Indeed, although the root Cu content in the copt1 mutant was similar to that in WT on half MS medium, it was ∼35% lower in the copt1 mutant than in WT in the presence of 100 µM BCS (Supplemental Figure S9).

Figure 8.

Increased sensitivity of ubac2a/2b and copt1 mutant seedlings to a Cu chelator. Arabidopsis WT, ubac2a/2b and copt1 mutant seeds were surface-sterilized and sown onto 1/2 MS medium containing indicated concentrations of BCS. Ten days later, the pictures of the seedlings were taken (A) and the root lengths were measured (B). Bar = 1 cm. Values of root lengths are means of >10 seedlings ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the root length between the ubac2a/2b or copt1 mutant and WT for each BCS concentration calculated using Student’s t test. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

Degradation of COPT1 through the proteasome system

UBAC2s positively regulate the accumulation of COPT transporters, thereby increasing Cu uptake by plant cells. To test whether reduced accumulation of COPT1 proteins in the ubac2a/2b mutants was due to increased degradation by the 26S proteasome system, we examined the effect of MG132 (carbobenzoxy-Leu-Leu-leucinal), a proteasome inhibitor, on the protein levels of COPT-myc in transgenic WT and ubac2a/2b lines. Leaves of WT and ubac2a/2b lines containing the same PCOPT1::COPT1-myc, 35S::COPT1-myc or 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene were treated with 50 µM MG132 for 5 h. Protein blotting showed that MG132 treatment could substantially increase the COPT-myc protein levels in ubac2a/2− lines harboring the three COPT1-myc transgenes but only had relatively small or little effect on the COPT1-myc protein levels in WT plants expressing the same transgenes (Supplemental Figure S10). These results suggest that reduced accumulation of the Cu transporter in the ubac2a/2b mutant plants was largely due to increased degradation by the proteasome system.

To further investigate the mechanism of increased COPT1 degradation in the ubac2a/2b mutant, we analyzed the effects of MG132 and protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) individually or in combination on the kinetics of the COPT1-myc protein accumulation in transgenic WT and ubac2a/2b plants harboring the same 35S::COPT1-myc transgene. As shown in Figure 9, MG132 treatment resulted in only a slight increase in the COPT1-myc protein levels in the WT transgenic plants. In contrast, the COPT-myc protein levels increased by more than three-fold after 2 h and were restored almost to the WT levels after 4 h of MG132 treatment in the ubac2a/2b mutant background (Figure 9). However, in the presence of CHX, MG132-induced COPT1-myc protein increase in the ubac2a/2b mutant was blocked (Figure 9). Thus, increased accumulation of the COPT1-myc proteins in the ubac2a/2b mutant as a result of the inhibition of the proteasome system by MG132 is dependent on active protein synthesis. Interestingly, treatment of CHX alone resulted in only a small but detectable decrease in the COPT1-myc protein levels in both the WT and ubac2 mutant backgrounds (Figure 9), indicating that undegraded COPT1 proteins are quite stable under normal growth conditions as previously reported (Li et al., 2020).

Figure 9.

Effect of proteasome and protein synthesis inhibitors on the accumulation of COPT-myc proteins. A, Protein blot analysis of COPT1-myc levels affected by MG132 and CHX treatment. Leaves from transgenic lines containing the same 35S::COPT1-myc transgene but either in the WT or ubac2a/2b background were treated with MG132 (50 µM), CHX (100 µg/mL) or both MG132 and CHX (MG132/CHX) for indicated hours. The protein levels of COPT1-myc were then compared by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Actin proteins probed with an anti-acting monoclonal antibody were used as loading control. B, Measurements of the relative levels of COPT1-myc proteins in response to MG132 and CHX treatment. The relative densities of the COPT1-myc protein bands from the immunoblots were measured by ImageJ. Values of the relative densities of the COPT1-myc protein bands are means ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Role of the UBA domain of UBAC and PICC in COPT1 accumulation

As a ubiquitin-binding ERAD component, UBAC2 contains a conserved UBA domain at their C-terminus (Christianson et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2018). To determine the role of the UBA domain of Arabidopsis UBAC2 proteins, we previously generated a mutant UBAC2a in which two conserved residues in its UBA domain (M262 and L288) required for ubiquitin binding were changed to alanine residues (Wang et al., 2019). Genes encoding WT UBAC2a and mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A proteins were transformed into the ubac2a/2b double mutant plants. Analysis of these transgenic lines indicated that the C-terminal UBA domain of the UBAC2 proteins is critical for their role in pathogen-induced callose deposition and plant immunity (Wang et al., 2019). To determine whether the UBA domain of Arabidopsis UBAC2 is required for the COPT protein accumulation, we first tested the ability of WT UBAC2a and mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A proteins to restore the Cu deficient phenotype of the ubac2a/2b mutant. As shown in Figure 10A, while the ubac2a/2b mutant had a substantially reduced Cu content when compared to that in WT, the ubac2a/2b mutant expressing either WT UBAC2a or mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A proteins had Cu levels similar to those of WT plants. Thus, the UBA domain of UBAC2 protein is not required for regulating Cu uptake and accumulation.

Figure 10.

The role of the UBA domain of UBAC2a in Cu uptake and COPT1 accumulation. A, Cu content in WT, ubac2a/2b, and ubac2a/2b transgenic lines expressing either WT UBAC2a or mutant UBAC2a(mUBA) (UBAC2aM262A/L288A) proteins. Roots and shoots of 12-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on 1/2 MS plates were harvested and determined for Cu contents using atomic absorption spectrometry. Values are means of three replicates ±standard deviation. Double asterisks indicate statistically significant difference at P < 0.01 in the Cu content between the ubac2a/2b mutant and WT calculated using Student’s t test. B, Protein blot analysis of COPT1-myc accumulation as affected by the UBA domain of UBAC2a. A 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgenic line in the heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− background was crossed with ubac2a/2b/UBAC2a or ubac2a/2b/UBAC2a (mUBA) lines and the progeny were PCR-genotyped and analyzed for the protein levels of COPT1-myc by immunoblotting using an anti-myc monoclonal antibody. Actin proteins probed by an anti-actin monoclonal antibody were used as loading control. The experiments were repeated twice with very similar results.

To determine whether the UBA domain of UBAC2 proteins is required for the accumulation of COPT proteins, we crossed a heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− line harboring the 35S::COPT1-myc transgene (UBAC2a/2b+/−/35S::COPT1-myc) with a ubac2a/2b/UBAC2a or ubac2a/2b/UBAC2aM262A/L288A line. The progeny from the crosses were genotyped and those 35S::COPT1-myc transgenic progeny that differed in the zygosity of the ubac2a/2b mutations but also contained the WT UBAC2a or mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A transgene were compared for the COPT1-myc protein levels. As expected, heterozygous UBAC2a/2b+/− progeny accumulated high levels of COPT1-myc, whereas homozygous ubac2a/2b progeny with neither WT UBAC2a nor mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A transgene had reduced COPT-myc protein levels (Figure 10B). Importantly, homozygous ubac2a/2b progeny containing either WT UBAC2a or mutant UBAC2aM262A/L288A transgene accumulated high levels of COPT1-myc proteins (Figure 10B). These results indicate that the UBA domain of UVAC2 proteins is not required for COPT1 accumulation.

Arabidopsis UBAC2s interact with the plant-specific PICC protein, which is also localized in the ER (Wang et al., 2019). The UBAC2 and PICC proteins coordinately regulate the accumulation of the PMR4 callose synthase and play a critical role in pathogen-induced callose deposition and immunity (Wang et al., 2019). To determine whether PICC also plays a role in the accumulation of COPT proteins, we examined the effect of picc mutation on the accumulation of COPT1-myc by comparing its protein levels in transgenic WT and picc mutant plants harboring the PCOPT1::COPT1-myc, 35S::COPT1-myc or 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc transgene. Protein blotting detected similar levels of COPT1-myc proteins in independent transformants of WT and picc mutant plants harboring the PCOPT1::COPT1-myc or 35S::COPT1-myc construct (Supplemental Figure S11). More importantly, unlike transgenic ubac2a/2b mutant lines harboring the 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc construct, which accumulated almost no COPT1-myc proteins (Figure 8;Supplemental Figure S5C), transgenic picc mutant lines harboring the same 35S::SPPR1-COPT1-myc construct accumulated levels of COPT1-myc proteins similar to those in transgenic WT lines (Supplemental Figure S11). These results indicated that unlike UBAC2s, PICC did not have a significant role in the accumulation of the COPT proteins.

Discussion

Arabidopsis mutants for the two ER-localized UBAC2 homologs are compromised in plant heat tolerance, resistance to necrotrophic pathogens and pathogen-induced callose deposition (Zhou et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). The critical roles of Arabidopsis UBAC2s in plant stress tolerance and disease resistance are mediated through at least two mechanisms. First, UBAC2s interact with plant-specific ATI3 selective autophagy receptors and mediate autophagic degradation of specific ER components, thereby mitigating ER stress and promoting cell survival during biotic and abiotic stresses (Zhou et al., 2018). On the other hand, the critical role of UBAC2s in pathogen-induced callose deposition and immunity is mediated through its coordinated action with ER-localized PICC protein in the accumulation of PMR4 callose synthase (Wang et al., 1998). In this study, we report that Arabidopsis UBAC2s also interacted with plasma membrane-targeted COPT Cu transporters (Figures 1–3) and positively regulated their accumulation and Cu content in Arabidopsis (Figure 7). Arabidopsis UBAC2 proteins also interact with PCR8, a member of the PCR metal transporter family. Preliminary analysis showed that UBAC2 proteins also promoted the accumulation of PCR8 in Arabidopsis indicating that UBAC2s may also be involved in the modulation of uptake and distribution of other metal ions in plant cells. These findings underscore the importance of the evolutionarily conserved UBAC2 proteins in a wide spectrum of biological and physiological processes not only in animals but also in plants.

As a highly conserved protein, UBAC2 was initially identified as a subunit of the gp78 E3 ligase complex in mammalian cells and has been linked with a number of cellular processes and pathological disorders likely through its action with the Hrd1 and gp78 ubiquitin ligases in ERAD (Christianson et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). Defects in ERAD lead to reduced degradation of misfolded and other abnormal protein substrates such as the mutated forms of the BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) receptor kinases bri1-5 and bri1-9 proteins (Hong et al., 2008, 2009; Jin et al., 2009; Su et al., 2011, 2012). Given the role of mammalian UBAC2s in ERAD, therefore, promotion of accumulation of PMR4 callose synthase and COPT transporter proteins by UBAC2s is unexpected. Neither UBAC2s nor PICC directly interacts with PMR4, indicating that UBAC2s and PPICC promote PMR4 accumulation through an indirect mechanism. Furthermore, the role of UBAC2s in promoting PMR4 accumulation and pathogen-induced callose deposition is dependent on the UBA domain of UBAC2s, suggesting involvement of ubiquitination, possibly through targeted degradation of a negative regulator of PMR4 stability (Wang et al., 2019). Reduced accumulation of COPT1 proteins in the ubac2a/2b mutant plants could be largely restored by the MG132, proteasome inhibitor (Figure 9; Supplemental Figure S10), indicating that the positive role of UBAC2 proteins in the accumulation of COPT1 was largely through inhibition of their degradation. However, there are important differences in the mechanisms by which UBAC2s promote COPT proteins versus PMR4 callose synthase. First, UBAC2s interact directly with COPT proteins and, therefore, the positive effect of UBAC2s on COPT protein accumulation is more likely to be direct. Second, unlike with PMR4, UBAC2s promote the accumulation of COPT1 in a manner that is not dependent on PICC or the UBA domain of UBAC2s (Figure 10; Supplemental Figure S11). These findings strongly suggest that UBAC2s stabilize COPT proteins most likely by stabilizing the Cu transporter proteins through direct binding to protect them against degradation by the proteasome system.

Analysis of the effects of both MG132 and protein synthesis inhibitor CHX provided further insights into the nature of COPT proteins that are targeted by the proteasome system. Even though MG132 alone could restore the COPT1 protein levels in the ubac2a/2b mutant close to the WT levels, this effect of MG132 was completely blocked by CHX (Figure 9). Therefore, the ability of MG132 to increase COPT1 accumulation in the ubac2a/2b mutant was dependent on active protein synthesis. A plausible explanation for the observation is that the absence of UBAC2s in the ubac2a/2b mutant renders the newly synthesized COPT1 at the ER unstable and susceptible to increased degradation by the proteasome system. Interestingly, in the presence of CHX alone, the COPT1 proteins levels were quite steady over the 4-h period in both WT and ubac2a/2b mutants (Figure 9), indicating that those COPT1 proteins that escape proteasomal degradation are quite stable under normal condition even in the ubac2a/2b mutant. It has been recently reported that although the levels of Arabidopsis COPT1 protein remained steady after CHX treatment under normal growth condition, they were reduced substantially in the presence of excess Cu (Li et al., 2020). Further pharmacological analysis revealed that Cu-induced COPT1 degradation is not mediated by increased endocytosis and vacuolar degradation (Li et al., 2020), which often target plasma membrane-localized proteins including Arabidopsis boron transporter BOR1 upon high boron availability and IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER 1 in the presence of excess noniron metal ions (Barberon et al., 2011; Kasai et al., 2011; Dubeaux et al., 2018). However, Cu-induced COPT1 degradation was blocked by MG132 but excess Cu and MG132 did not induce COPT1 ubiquitination, indicating that COPT1 is subjected to degradation by the ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation pathway probably at both the plasma membrane and the ER (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, while targeted endocytosis and vesicle trafficking are involved in the regulation of many plasma membrane-targeted proteins such as receptor-like protein kinases and transporters, targeted proteasomal degradation of newly synthesized proteins at the ER could play a uniquely important role in the regulation of specific ER-synthesized proteins such as plasma membrane-targeted COPT-family transporter proteins. Further analysis will be necessary to determine whether evolutionarily conserved UBAC2 proteins are part of the ER protein quality control network that provides differential stabilization of specific ER proteins in response to changes in the environmental conditions.

The activity of UBAC2 proteins to physically interact with the COPT proteins and protect them from proteasomal degradation suggest a function of UBAC2s potentially as protein chaperones for specific ER-synthesized proteins. Plant COPT proteins belong to the highly conserved CTR1 high-affinity Cu transporter family highly conserved in different eukaryotic organisms (Sancenon et al., 2004). Genetic, biochemical, and structural characterization has established that CTR1 Cu transporter is a symmetric trimer architecture (Ren et al., 2019). Unlike other secretory proteins synthesized at the ER, COPT proteins have unusual structures. As discussed earlier and also recently reported (Li et al., 2020), Arabidopsis plasma membrane-targeted COPT proteins do not contain a canonical cleavable N-terminal signal peptide (Supplemental Figure S1). Its first TMD may act as its signal peptide but is preceded by a relatively large N-terminal domain of >60 amino acid residues that contains an intrinsically disordered sequence (Supplemental Figures S1 and S7). Therefore, the N-terminal domain of COPT proteins may have a high propensity of misfolding and interaction with other proteins upon emerging from the ribosomes during synthesis. In addition, the subcellular distribution of Arabidopsis COPT1 is not affected by treatment of Brefeldin, a fungal macrocyclic lactone and a potent, reversible inhibitor of intracellular vesicle formation and protein trafficking between the ER the Golgi apparatus (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, ER-synthesized COPT1 is probably not transported to the plasma membrane through the conventional ER-Golgi transport pathway (Li et al., 2020). Due to the unusual N-terminal domain and unconventional trafficking, ER-synthesized COPT proteins may require UBAC2 proteins through direct physical interaction for stabilization, proper sorting, and trafficking. Interestingly, the UBAC2–COPT1 interaction requires a large N-terminal COPT1 sequence of more than 100 residues (Figure 2), which may involve an unstable COPT conformational structure that is recognized by UBAC2s for stabilization and protection against proteasomal degradation. While UBAC2 proteins protect the full-length COPT1 through direct binding of a conformational structure of the COPT, deletion of the N-terminal 20 amino acid residues of COPT1 abolished its interaction with UBAC2, but did not affect its accumulation in N. benthamiana cells in the BiFC assays (Supplemental Figure S2B). It is possible that deletion of the intrinsically disorganized N-terminal 20 amino acids of COPT1 renders the truncated protein more stable and resistant to proteasomal degradation.

A highly unexpected finding of the study was the drastic effect of UBAC2s on the accumulation of the COPT1 proteins with an added signal peptide at its N-terminus (Figure 6;Supplemental Figure S5C). Adding a signal peptide to COPT1 was originally designed to improve the stability of COPT1 because of the relatively large N-terminal domain of >60 amino acid residues with an intrinsically disordered sequence preceding its first TMD. The relative long N-terminal domain might prematurely fold or interact with other proteins upon emerging from the ribosome during synthesis and inhibits translocation. In WT plants, however, the COPT1 protein with no N-terminal signal peptide accumulated at high levels (Figure 5;Supplemental Figure S5), indicating that cellular protein quality control system is apparently capable of stabilizing the N-terminal soluble domain of COPT proteins to prevent degradation by the proteasome system. Likewise, addition of a signal peptide at the N-terminus of COPT1 did not affect the accumulation or the size of mature COPT1 proteins in WT plants (Figure 6;Supplemental Figure S5C). The generated Cu transporter proteins from SPPR1-COPT1 also appeared to be fully functional based on the observations that its overexpression increased Cu content and conferred Cu hypersensitivity in transgenic plants (Supplemental Figure S8). In contrast, while the ubac2a/2b mutations had a substantial effect on the levels of COPT1 proteins with no N-terminal signal peptide (Figures 4 and 5), they abolished the accumulation of the SPPR1-COP1-myc fusion proteins (Figure 5;Supplemental Figure S5C). Adding a signal peptide could potentially change the kinetics of translocation of COPT proteins across the ER membrane. Translocation of the native COPT proteins without an N-terminal signal peptide is likely to be directed by their first TMD, which will occur after the relative long N-terminal domain has already emerged from the ribosome during the synthesis of the COPT proteins. Adding a signal peptide at the N-terminus, on the other hand, would direct the soluble N-terminal domain for import into the ER as the peptide is being synthesized. In addition, prior to its cleavage inside the ER, the added signal peptide at the N-terminus could affect the folding and assembly of COPT proteins at the ER. In the absence of functional UBAC2s in the ubac2a/2b mutant, altered kinetics or protein structure of COPT proteins with an added signal peptide at the N-terminus apparently make the COPT proteins abnormal and highly susceptible to the proteasome system. These results again support a role of UBAC2s in the quality control of specific ER proteins. It is worthy to note that even though the physiological relevance of the UBAC2 dependency of the accumulation of SPPR1-COPT remains to be examined, this engineered fusion protein can be a powerful tool for dissecting the important ER protein quality control pathway through genetic, biochemical, and molecular approaches.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the conserved UBAC2 proteins from Arabidopsis play a critical role not only in plant heat tolerance and plant immunity but also in the regulation of Cu content by interacting with plasma membrane-localized COPT Cu transporter proteins and promoting their accumulation. Studies using different COPT1 transgenes and assays of sensitivity to the proteasome and protein synthesis inhibitors strongly suggest that UBAC2s promote accumulation of COPT proteins most likely by stabilizing the newly synthesized COPT proteins to protect them from degradation by the proteasome system. COPT proteins are among a substantial percentage of ER-synthesized secretory proteins that contain no canonical signal peptide and are exported through unconventional trafficking pathways (Li et al., 2020). UBAC2 proteins could be part of an ER quality control pathway that regulates the stability and trafficking of the special class of ER-synthesized secretory/membrane proteins. With the knowledge and tools generated from the study, it is now possible to identify and characterize the components and mechanisms of the UBAC2-mediated protein quality control pathway. Even though the critical role of mammalian UBAC2 in ERAD has been well established, the important roles of Arabidopsis UBAC2 proteins in plant stress responses and Cu accumulation appear to be mediated by mechanisms that are not directly linked with ERAD. It remains to be determined whether structurally conserved UBAC proteins have diversified functions in different organisms.

Materials and methods

Arabidopsis genotypes and plant growth conditions

The Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) mutants and WT plants used in the study are all in the Col-0 background. The uba2a-1, uba2a-2, uba2b-1, picc1-1, and copt1 mutants have been previously described (Zhou et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana plants were grown in growth chambers or rooms at 24°C, 120 µE m−2s−1 light on a photoperiod of 12-h light and 12-h dark.

Yeast two-hybrid screen and assays

Gal4 based yeast two-hybrid system was utilized for identification of UBAC2a-interacting proteins, as described previously (Zhou et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Briefly, full-length UBAC2a coding sequence was PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (5′-agcgaattcatgaacggcggtccctcc-3′ and 5′-agcgtcgacttagtttctgtcgaatcccatt-3′) and cloned into pBD-GAL4 vector to generate the bait vector. The Arabidopsis HybridZAP-2.1 two-hybrid cDNA library, which was prepared from Arabidopsis plants, has been described previously. The bait plasmid and the cDNA library were used to transform yeast strain YRG-2. Yeast transformants were plated onto selection medium lacking Trp, Leu, His, and confirmed by β-galactosidase activity assays using O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as substrate.

For assays of interactions among UBAC2a and UBAC2b with truncated COPT1 and other members of the COPT protein family, their corresponding coding sequences were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1), and the PCR products were inserted into the pBD-GAL4 or pAD-GAL4 vector, as appropriate. Various combinations of bait and prey constructs were cotransformed into yeast cells, and interactions were analyzed through assays of the LacZ β-galactosidase reporter gene activity.

BiFC assays

The full-length UBAC2a and COPT1 coding sequences were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (UBAC2a: 5′-agcgagctcatgaacggcggtccctcc-3′ and 5′-agctctagagtgggactgtgcttcgaga-3′; COPT1: 5′- agcgagctcatggatcatgatcacatgca-3′ and 5′- agctctagaacaagcacaacctgagggag-3′) and cloned into pFGC-C-YFP and pFGC-N-YFP, respectively. The truncated COPT1(Δ1-20) coding sequence was PCR-amplified using specific primers (5′-agcgagctcatgtcatccatgatgaacaatgg-3′ and 5′- agctctagaacaagcacaacctgagggag-3′). The plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV3101) and infiltration into N. benthamiana. BiFC fluorescent signals in infected tissues were analyzed at 24 h after infiltration with a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope with appropriate filter sets (excitation 514 nm, emission 525–555 nm, see details below).

Measurement of Cu content

Root and shoot tissues of 12-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on 1/2 MS plates were harvested, washed with 20 μm EDTA, and deionized water and dried at 65°C. Dried samples (∼50 mg) were digested in HNO3. The Cu contents of the samples were then determined by atomic absorption spectrometry (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan).

Assays of BCS sensitivity

Arabidopsis seeds of different genotypes were surface-sterilized and sown onto 1/2 MS medium containing 0, 100, and 150 µM BCS. The plates were vertically placed in a growth chamber at 24°C, 120 µE m−2s−1 light on a photoperiod of 12-h light and 12-h dark. The seedling growth and root lengths were observed 10 d later.

Generation of COPT1-GFP and COPT1-myc constructs and plant transformation

The 1,434-bp promoter sequence upstream of the start codon of Arabidopsis COPT1 gene was PCR-amplified using sequence-specific primers (5′-agcaagcttgtggtatctggtcgtcatcg-3′ and 5′-agcctcgagttctttgttcttggctcttgtg-3′) and cloned into a modified pCAMBIA1300 vector. For generating COPT1-GFP fusion gene, full-length COPT1 coding sequence was PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (5′-agcctcgagatggatcatgatcacatgca-3′ and 5′-agcccatggcacaagcacaacctgagggag-3′) and fused to the GFP gene or myc tag behind the COPT1 native or the CaMV 35S promoter in a modified pCAMBIA1300 plant transformation vector. For generating the SPPR1a-COPT-myc fusion, the sequence for the N. tabacum PR1 SP was first amplified using gene-specific primers (5′-agcccatgggatttgttctcttttcaca-3′ and 5′-catgcatgtgatcatgatccatattttgggcacggcaagagt-3′) and fused to the COPT1-myc sequence by using overlap PCR using the sequence-specific primers (5′-agcccatgggatttgttctcttttcaca-3′ and 5′-agcttaattaaacaagcacaacctgagggag-3′). The fusion gene was placed behind the CaMV 35S promoter in a modified pCAMBIA1300 plant transformation vector. Full-length COPT2 and COPT6 coding sequences were PCR-amplified using gene-specific primers (COPT2: 5′-agcccatggatcatgatcacatgcat-3′ and 5′-agcttaattaaacaaacgcagcctgaagac-3′; COPT6: 5′-agcccatggatcatggtaacatgcc-3′ and 5′-agcttaattaatagttgttcgaagggtttctcg-3′) and fused with the myc tag behind the CaMV 35S promoter in modified pCAMBIA1300 plant transformation vector. The resulting constructs were introduced into the A. tumefaciens (strain GV3101) and transformed into Arabidopsis by floral-dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) followed by DNase treatment with Turbo DNA-free). cDNA was synthesized from 2.5 μg total RNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Transcript levels were determined by RT-qPCR with ACTIN2 as an internal control using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S2).

Confocal fluorescence microscopy

Imaging of GFP signals was performed with a Nikon A1 Rsi confocal laser microscope with the following filter sets: excitation 488 nm, emission 500–550 nm. Specific settings for the confocal microscopy include the following: optical section, 2.92 μm; optical resolution, 0.4 μm; pixel dwell time, 2.2 μs; laser power, 5%; pinhole, 52.36 μm; HV gain, 90–120; offset background adjustment, 0.

Western blotting

Total leaf proteins were prepared by homogenization of leaf tissues in a protein extraction buffer and clarification by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined by the colorimetric assay using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit. Proteins were fractionated by SDS–PAGE on 12.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel, and the separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described with an anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) or polyclonal antibodies recognizing N- or C-terminal of YFP (Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden). Rubisco large subunit proteins stained with Ponceau S or acting proteins probed with an anti-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma) were used as loading control.

Prediction of intrinsically disordered protein sequences

The IUPred2 software (https://iupred2a.elte.hu) was used to predict intrinsically disordered sequences in the COPT1 protein.

Accession numbers

Arabidopsis Genome Initiative numbers for the genes discussed in this article are as follows: UBAC2a (AT3g56740), UBAC2b (AT2g41160), PICC (AT2g32240), COPT1 (At5g59030), COPT2 (At3g46900), COPT3 (At5g59040), COPY4(At2g37925), COPT5 (At5g20650), and COPT6 (At2g26975), ACTIN2 (AT3g18780).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Comparison of Arabidopsis COPT Cu transporter protein sequences.

Supplemental Figure S2. BiFC assays of the interaction between UBAC2a and COPT1(Δ1-20).

Supplemental Figure S3. Interaction of UBAC2 proteins with members of the COPT protein family.

Supplemental Figure S4. Accumulation and subcellular accumulation of COPT1-GFP under control of its native promoter.

Supplemental Figure S5. Accumulation of COPT1-myc in the transgenic lines harboring different COPT1-myc transgene constructs.

Supplemental Figure S6. Accumulation of COPT2- and COPT6-myc in the transgenic lines.

Supplemental Figure S7. Prediction of intrinsically disordered protein region in COPT1.

Supplemental Figure S8. SP-COPT1-myc is functional in WT as a Cu transporter.

Supplemental Figure S9. Effect of BCS in the growth medium on the Cu contents in WT and ubac2a/2b mutant roots.

Supplemental Figure S10. Effect of the MG132 proteasomal inhibitor on the accumulation of COPT-myc proteins.

Supplemental Figure S11. Effect of PICC mutation on the accumulation of COPT-myc proteins.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers for gene constructs used in yeast two-hybrid assays.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers for RT-qPCR analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Xiaoting Wang and Xiaohui Li for their help and Dr Lola Penarrubia for the copt1 mutant.

Funding

This work was supported by China National Major Research and Development Plan (grant no. 0111900) and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. LQ20C020002) at China Jiliang University and by US National Science Foundation (grant no. IOS-0958066 and IOS1456300) at Purdue University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

C.Z. and Z.C. conceived the original research plans and supervised the experiments; X.L., Z.W., and Y.F. performed most of the experiments; X.C., Y.Z., and B.F. performed some of the experiments; X.L., Z.W., Y.F., C.Z., and Z.C. analyzed the data and wrote the article with contributions of all the authors.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/General-Instructions) is Zhixiang Chen (zhixiang@purdue.edu).

References

- Adams BM, Oster ME, Hebert DN (2019) Protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Protein J 38:317–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberon M, Zelazny E, Robert S, Conejero G, Curie C, Friml J, Vert G (2011) Monoubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of the IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER 1 (IRT1) transporter controls iron uptake in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:E450–E458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham AM (2012) Protein secretion and the endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4:a012872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner N, Reutter KR, Wolf DH (2018) Protein quality control of the endoplasmic reticulum and ubiquitin-proteasome-triggered degradation of aberrant proteins: yeast pioneers the path. Annu Rev Biochem 87:751–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Zhong X, McAlpine W, Liao TC, Zhang D, Fang B, Russell J, Ludwig S, Nair-Gill E, Zhang Z, et al. (2019) LMBR1L regulates lymphopoiesis through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Science 364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JC, Olzmann JA, Shaler TA, Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Richter CM, Tyler RE, Greenblatt EJ, Harper JW, Kopito RR (2012) Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol 14:93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16:735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubeaux G, Neveu J, Zelazny E, Vert G (2018) Metal sensing by the IRT1 transporter-receptor orchestrates its own degradation and plant metal nutrition. Mol Cell 69:953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina A, Andres-Colas N, Perea-Garcia A, Del Valle-Tascon S, Penarrubia L, Puig S (2011) The intracellular Arabidopsis COPT5 transport protein is required for photosynthetic electron transport under severe copper deficiency. Plant J 65:848–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina A, Andres-Colas N, Perea-Garcia A, Neumann U, Dodani SC, Huijser P, Penarrubia L, Puig S (2013) The Arabidopsis COPT6 transport protein functions in copper distribution under copper-deficient conditions. Plant Cell Physiol 54:1378–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C, Zhao K, Zhou N, Liu F, Xie F, Yu S, Feng Y, Chen L, Yang J, Tian F, Jiang G (2020) UBAC2 promotes bladder cancer proliferation through BCRC-3/miRNA-182-5p/p27 axis. Cell Death Dis 11:733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Hall CK, Voegler AC (1998) Effect of denaturant and protein concentrations upon protein refolding and aggregation: a simple lattice model. Protein Sci 7:2642–2652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard J, Lamy P, Nordentoft I, Algaba F, Hoyer S, Ulhoi BP, Vang S, Reinert T, Hermann GG, Mogensen K, et al. (2016) Comprehensive transcriptional analysis of early-stage urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell 30:27–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Jin H, Fitchette AC, Xia Y, Monk AM, Faye L, Li J (2009) Mutations of an alpha1,6 mannosyltransferase inhibit endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of defective brassinosteroid receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21:3792–3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Jin H, Tzfira T, Li J (2008) Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20:3418–3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S, Shu Q, Jiang Z, Chen Y, Li F, Chen F, Kijlstra A, Yang P (2012) Replication study confirms the association between UBAC2 and Behcet’s disease in two independent Chinese sets of patients and controls. Arthritis Res Ther 14:R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Hong Z, Su W, Li J (2009) A plant-specific calreticulin is a key retention factor for a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HI, Gayomba SR, Rutzke MA, Craft E, Kochian LV, Vatamaniuk OK (2012) COPT6 is a plasma membrane transporter that functions in copper homeostasis in Arabidopsis and is a novel target of SQUAMOSA promoter-binding protein-like 7. J Biol Chem 287:33252–33267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai K, Takano J, Miwa K, Toyoda A, Fujiwara T (2011) High boron-induced ubiquitination regulates vacuolar sorting of the BOR1 borate transporter in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem 286:6175–6183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaumann S, Nickolaus SD, Furst SH, Starck S, Schneider S, Ekkehard Neuhaus H, Trentmann O (2011) The tonoplast copper transporter COPT5 acts as an exporter and is required for interorgan allocation of copper in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 192:393–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yuan J, Wang H, Zhang H, Zhang H (2020) Arabidopsis COPPER TRANSPORTER 1 undergoes degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner. J Exp Bot 71:6174–6186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan H, Xu M, Kraft P, Qureshi AA, Chen C, Guo Q, Hu FB, Curhan G, Amos CI, Wang LE, et al. (2011) Genome-wide association study identifies novel alleles associated with risk of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Mol Genet 20:3718–3724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren F, Logeman BL, Zhang X, Liu Y, Thiele DJ, Yuan P (2019) X-ray structures of the high-affinity copper transporter Ctr1. Nat Commun 10:1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancenon V, Puig S, Mateu-Andres I, Dorcey E, Thiele DJ, Penarrubia L (2004) The Arabidopsis copper transporter COPT1 functions in root elongation and pollen development. J Biol Chem 279:15348–15355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawalha AH, Hughes T, Nadig A, Yilmaz V, Aksu K, Keser G, Cefle A, Yazici A, Ergen A, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, et al. (2011) A putative functional variant within the UBAC2 gene is associated with increased risk of Behcet's disease. Arthritis Rheum 63:3607–3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WY, Choi KS, Kim DY, Geisler M, Park J, Vincenzetti V, Schellenberg M, Kim SH, Lim YP, Noh EW, et al. (2010) Arabidopsis PCR2 is a zinc exporter involved in both zinc extrusion and long-distance zinc transport. Plant Cell 22:2237–2252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WY, Martinoia E, Lee J, Kim D, Kim DY, Vogt E, Shim D, Choi KS, Hwang I, Lee Y (2004) A novel family of cys-rich membrane proteins mediates cadmium resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 135:1027–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Liu Y, Xia Y, Hong Z, Li J (2011) Conserved endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system to eliminate mutated receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:870–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Liu Y, Xia Y, Hong Z, Li J (2012) The Arabidopsis homolog of the mammalian OS-9 protein plays a key role in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of misfolded receptor-like kinases. Mol Plant 5:929–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fang P, Sachs MS (1998) The evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic arginine attenuator peptide regulates the movement of ribosomes that have translated it [in process citation]. Mol Cell Biol 18:7528–7536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Li X, Wang X, Liu N, Xu B, Peng Q, Guo Z, Fan B, Zhu C, Chen Z (2019) Arabidopsis endoplasmic reticulum-localized UBAC2 proteins interact with PAMP-INDUCED COILED-COIL to regulate pathogen-induced callose deposition and plant immunity. Plant Cell 31:153–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazoe K, Meguro A, Takeuchi M, Shibuya E, Ohno S, Mizuki N (2017) Comprehensive analysis of the association between UBAC2 polymorphisms and Behcet's disease in a Japanese population. Sci Rep 7:742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Xu Y, Liu Y, Ye Y (2015) gp78 functions downstream of Hrd1 to promote degradation of misfolded proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell 26:4438–4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang Z, Wang X, Li X, Zhang Z, Fan B, Zhu C, Chen Z (2018) Dicot-specific ATG8-interacting ATI3 proteins interact with conserved UBAC2 proteins and play critical roles in plant stress responses. Autophagy 14:487–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.