Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is a catastrophe. It was also preventable. The potential impacts of a novel pathogen were foreseen and for decades scientists and commentators around the world warned of the threat. Most governments and global institutions failed to heed the warnings or to pay enough attention to risks emerging at the interface of human, animal, and environmental health. We were not ready for COVID-19, and people, economies, and governments around the world have suffered as a result. We must learn from these experiences now and implement transformational changes so that we can prevent future crises, and if and when emergencies do emerge, we can respond in more timely, robust and equitable ways, and minimize immediate and longer-term impacts.

In 2020–21 the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development assessed the challenges posed by COVID-19 in the WHO European region and the lessons from the response. The Commissioners have addressed health in its entirety, analyzing the interactions between health and sustainable development and considering how other policy priorities can contribute to achieving both. The Commission's final report makes a series of policy recommendations that are evidence-informed and above all actionable. Adopting them would achieve seven key objectives and help build truly sustainable health systems and fairer societies.

1. Introduction

A catastrophe on the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic was preventable. For decades scientists and commentators around the world have urged governments and global institutions to prepare for the emergence of new diseases at the interface of human, animal, and environmental health [1] – but such warnings went unheeded. The potential impact of a novel airborne pathogen was known, yet we were still not ready. Global and national policy responses were inadequate; many countries have paid a heavy health, societal and economic price. We must learn the lessons from this pandemic [2], acting now to minimize its consequences, and to prevent another.

Over the past year, members of the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development [3], an independent multidisciplinary group of experts, reviewed lessons from the pandemic, identifying ways that society might change and address future threats to health, with a particular focus on the European Region of the World Health Organization (WHO). The Commission took a broad approach to health that went beyond pandemics to analyze the interactions between health and sustainable development and the position of health in relation to other policy priorities. Adopting a ‘One Health’ approach, the Commissioners reviewed evidence that embraces humans, animals, micro-organisms and the natural environment to consider the many proximal and distal determinants of health and the policies that impact on them [4].

1.1. Recommendations

The Commission's final report [5] recommends a series of evidence-informed policy recommendations designed to achieve the seven objectives it identified as key to building sustainable health systems and resilient societies (Table 1 ). Below, we briefly summarize each of these objectives and its associated recommendations in turn.

Table 1.

Recommendations from the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development.

| Objective | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 1. Operationalize the concept of One Health at all levels | a) Governments establish structures, incentives and a supportive environment to develop coherent cross-government One Health strategies, building on the concept of Health in All Policies and the SDGs. b) Mechanisms for coordination and collaboration between relevant international agencies, such as WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) are strengthened, in order to support efforts towards a shared understanding, common terminologies, and an appropriate international architecture for establishing priorities, agreeing areas of responsibility and identifying the scope for joint work to promote the health of humans, animals and the natural environment. c) Coordinated action is taken at all levels to reduce environmental risks to health, including biodiversity- and climate-related risks, and to enhance One Health reporting systems. |

| 2. Take action at all levels of societies to heal the fractures exacerbated by the pandemic | a) Information systems capture the many inequalities in health and access to care within populations, in order to inform policies and interventions that address the deep-seated causes of these inequalities. b) Those in society who lead impoverished or precarious lives are identified, and policies are developed and implemented to give them the security that underpins good health. c) Explicit quotas are adopted for the representation of women on public bodies that are involved in the formulation and implementation of health policy. |

| 3. Support innovation for better One Health | a) A strategic review is made of areas of unmet need for the innovations required to improve One Health in Europe. b) Mechanisms are established to align research, development and implementation of policies and interventions to improve One Health, based on a true partnership between the public and private sectors in which both risks and returns are shared. c) With the support of the WHO Regional Office for Europe, continue efforts to develop a mechanism for constant generation of knowledge, learning and improvement, based on innovation in the pan-European region. |

| 4. Invest in strong, resilient and inclusive national health systems | a) All investments in health systems are increased, particularly in those parts of systems that have traditionally attracted fewer resources, such as primary and mental health care, while ensuring that this investment is directed in ways that maximise the ability of health systems to deliver the best possible health for those who use them. b) The health workforce is invested in and strengthened in the light of experiences during the pandemic, with a focus on ways of attracting, retaining and supporting health and care workers throughout their careers, coupled with reviews of how the roles of health workers can evolve, given the rapidly changing nature of medicine and technology. c) The links between health and social care are reassessed and strengthened in the light of experiences during the pandemic, with the goal of increasing integration between them. d) Communicable and noncommunicable disease prevention is prioritized and investment in public health capacities is scaled up. |

| 5. Create an enabling environment to promote investment in health | a) The way in which health expenditure data are captured changes, so that there is a clearer distinction between consumed health expenditure, on the one hand, and so-called frontier-shifting investments in disease prevention and improvements in the efficiency of care delivery, on the other. b) Investment in measures to reduce threats, provide early warning systems and improve responses to crises is scaled up. c) WHO's health system surveillance powers are strengthened and include periodic assessments of preparedness, which feed into monitoring by the International Monetary Fund, development banks and other technical institutions. d) The share of development finance spent on global public goods, long-standing cross-border externalities and, more generally, health is increased. e) Health-related considerations are incorporated into economic forecasts, business strategies and risk management frameworks at all levels. |

| 6. Improve health governance at the global level | a) A Global Health Board is established under the auspices of the G20, in order to promote a better assessment of the social, economic and financial consequences of health-related risks, drawing on insights from experience with the Network for Greening the Financial System, the Financial Stability Board and other climate and biodiversity initiatives, and to scale up private finance for health. b) A Pandemic Treaty is agreed that is truly global, enables compliance, has sufficient flexibility and entails inventive mechanisms that encourage governments to pool some sovereign decision-making for policy-making areas. c) A global pandemic vaccine policy is developed that sets out the rights and responsibilities of all concerned to ensure the availability and distribution of vaccines. |

| 7. Improve health governance in the pan-European region | a) A Pan-European Network for Disease Control is established, led by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, to provide rapid, effective responses to emerging threats by strengthening early warning systems, including epidemiological and laboratory capacity, and supporting the development of an interoperable health data network based on common standards developed by WHO, recognising that governments will move at different speeds. b) A Pan-European Health Threats Council is convened by the WHO Regional Office for Europe to enhance and maintain political commitment, complementarity and cooperation across the multilateral system, accountability, and promotion of collaboration and coordination between legislatures and executive agencies in the pan-European region. c) Multilateral development banks and development finance institutions prioritise investments in data-sharing and data interoperability platforms. d) The necessary funding is secured for WHO to fulfil its mandate within the WHO European Region. |

Source: Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development. Drawing light from the pandemic: A new strategy for health and sustainable development. Copenhagen; 2021.

2. Operationalize the concept of one health at all levels

COVID-19 is a tragedy we must lament, but we can also seize it as an opportunity to rethink our existing global health architecture [6]. Many threats to health arise at the intersection of human, animal and environmental health – not least, the increase in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) that may yet reverse the achievements of modern medicine [7]. The inordinate effects on the planet of human (in)action are recognized in the naming of a new era, the Anthropocene [8]. The danger that the planet has reached an irrevocable tipping point is real: human activities have caused global warming and loss of habitat and biodiversity, and we know that exacerbating feedback between these phenomena is increasing the risks of food insecurity, conflict, mass migration and more.

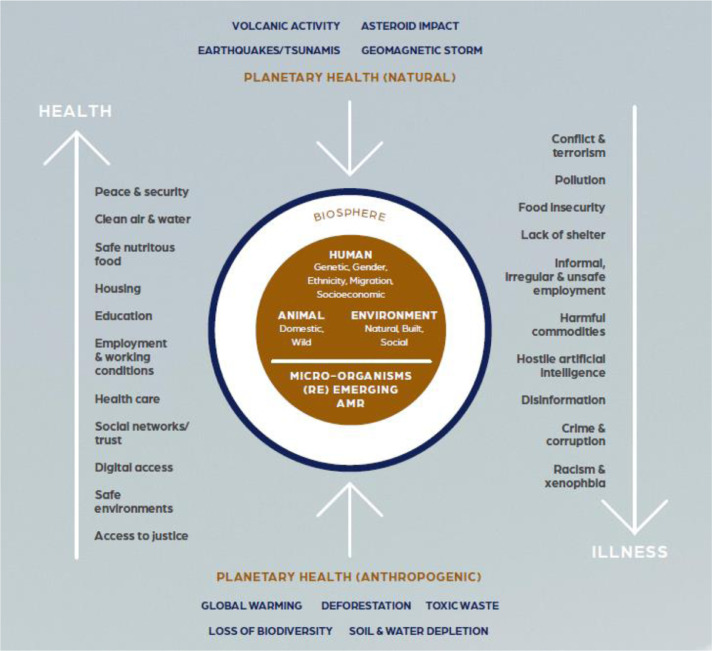

Despite the intrinsic links between their areas of work, those engaged with the different aspects of One Health frequently work in silos (Fig. 1 ). From now on, we must instead operationalize an integrated, holistic One Health approach [9,10], which acknowledges the complex interconnections between its various elements, and convenes and aligns stakeholders wherever relevant.

Fig. 1.

The Determinants of One Health in the 21st Century. Reprinted from: McKee, ed. (2021) Drawing light from the pandemic: a new strategy for health and sustainable development—a review of the evidence. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Challenges to operationalizing One Health have been described in the past [11,12], including a lack of surveillance capacity, siloed thinking and actors, unequal representation of disciplines and stakeholders, difficulties in engaging actors from a diverse set of backgrounds, lack of evidence on the benefits of One Health, including problems generating and obtaining access to relevant and accurate One Health data and other information [13]. We need to address these challenges with solutions that promote equitable engagement and collaboration between diverse stakeholders and enhanced monitoring and evaluation of One Health initiatives so that continued improvements can be made based on lessons learned through an increasingly comprehensive evidence-base.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the importance of effective joint working by national and regional governments, supported by timely access to high quality comparable data. Structures, incentives and a supportive policy environment are needed to establish whole-of-government One Health strategies. Mechanisms for strengthening coordination and collaboration [14] amongst relevant existing international agencies (including the WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Organisation for Animal Health, and the United Nations Environment Programme), grassroots movements, and community groups must be prioritized. This will require better metrics to be developed to enable the measurement of progress in all aspects of One Health so that policies, resource allocation and projects can be assessed and strengthened.

3. Take action at all levels of societies to heal the fractures exacerbated by the pandemic

COVID-19 continues to shine a light on the intersecting inequalities that characterize our societies and their interacting consequences for health [15]. Those who were disadvantaged before COVID-19 often suffer the worst consequences, both from the effects of the virus and from the policy responses required to tackle it. Pre-existing differences in wealth and income and unequal opportunities have left many people facing precariousness in employment, wages, and housing, and even food supplies have been exacerbated by inadequate social protection [16]. An ambitious approach must be taken to heal these fractures. This requires a renewed commitment to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of universal health coverage (UHC) and to joint procurement initiatives such as COVAX and Gavi. But it also demands access to appropriate information that can make these fractures visible [17], capturing all the characteristics that place people at increased risk. In particular, data on ethnicity and migration status is required, which is at present collected in only a few European countries, with the consequence that factors such as racism go unrecognized as determinants of health [18]. It is also important to better understand the concept of precariousness, whereby people may be coping at a particular time while facing constant insecurity [19]. COVID-19 has also highlighted the importance of tackling the divisions encouraged by disinformation spread through social media – including anti-vax messaging [20,21]. As lives move increasingly into the digital space it will be necessary to develop novel methods of addressing the growing number of online threats, working across sectors to design and implement policies that make the online world safe. As the role of technology and social media continues to increase in our daily lives, governments must work together with tech leaders and companies and civil society, and they must effectively regulate social media platforms to ensure users are exposed to information backed by evidence and science, and to guarantee disinformation is promptly addressed.

Recognizing the particular consequences that the pandemic has had for women and the vital role they have played in the COVID-19 response [22], it is essential that their input into decision-making is equal to that of men and that their involvement goes beyond the tokenistic. This same call was made more than 20 years ago in the Beijing Declaration, endorsed by the international community at the Fourth World Conference of Women in 1995 [23,24] – it must be acted on now.

4. Support innovation for one health

COVID-19 vaccines were developed, distributed and deployed in under a year – a remarkable success and a clear demonstration of the importance of support for innovation. The experience has shown what rapid mobilization of financial resources, collaboration, partnership between public, private and third sector organizations, and accelerated procedures for evaluating and approving innovative products can do to support One Health. Building on this momentum, governments must develop and support innovation strategies that proactively identify and address needs that are not otherwise being met. We must also learn the negative lessons from the experience of innovation during the pandemic. In particular, we must ask why so much risk is borne by the public sector (through research funding), while most of the returns flow to the private sector [25]. Governance and accountability mechanisms must be employed to ensure that incentives for discovery, development and implementation align with interventions that improve One Health, based on true public–private partnerships where risks and rewards are shared [26].

It is vital, too, to plan and prepare for the potential unintended or negative consequences of innovations – for example, in light of the growing influence of social media and the extension of the digital delivery of health care during the pandemic, what such changes mean for those for those who are susceptible to disinformation campaigns; for those who are digitally excluded; or for those who might be further disadvantaged by the use of algorithms that replicate the discrimination already afflicting so many societies [27].

5. Invest in strong, resilient and inclusive national health systems

We must invest in healthy and resilient societies for the future. Historically, calls for expenditure on health, social care, education and research have often been left unanswered because of difficulties in convincing spending ministries that these investments in human and intellectual capital are necessary to achieve progress in a knowledge-based economy [28]. We need to change this mindset, and foster international recognition of the economic arguments for investing in population health and wellbeing [29]. Fortunately, we are seeing increasing evidence that opinion leaders from the financial sector are acknowledging this. Policies to increase health system resilience must include the physical and human elements, including health facility design and the leveraging of digital innovations, and health workforce capacity and the greater flexibility arising from new approaches to task shifting [30]. Coordination of health and social care also needs to be strengthened. Investments in health systems must be increased, but especially in those areas that traditionally attract fewer resources such as primary care and mental health. Looking ahead, the experience of the pandemic, which created high levels of health worker burnout, has emphasized the importance of measures that can attract, retain and support health care workers throughout their careers [31]. Finally, the need for increased investment in public health capacity and the prevention of communicable and noncommunicable diseases remains essential.

6. Create an enabling environment to promote investment in health

Investments in health may have short-term costs but, if planned well, they often bring higher long-term financial benefits. Past failures to invest in health have been fuelled by short-termism, and failure to recognize the wider benefits that health systems bring to society. We cannot afford to continue in this manner; changes to the information, incentives and norms that govern the allocation of resources are needed. A clearer distinction should be made between health expenditure for consumption and frontier-shifting investments in disease prevention and improvements in the efficiency of care delivery. Additionally, the economic benefits of better health (and the converse) should be incorporated into macroeconomic forecasting [32] and greater investments should be made in measures to reduce health threats, provide early warning systems and improve crisis response. These measures will require increased global and international collaboration. By their nature, health threats cut across borders and responses often have the characteristics of public goods [33,34]. Therefore, the share of development finance spent on global public goods and long-standing cross-border externalities must be increased. The WHO's health system surveillance powers must also be strengthened, enabling the organization to conduct periodic assessments of countries’ preparedness, which can then feed into monitoring by the International Monetary Fund, development banks, and technical institutions.

7. Improve health governance at the global level

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred despite the fact that most nations in the world were States Parties to the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) and had agreed in principle to combat health threats through joint action. This failure demonstrates the weaknesses and gaps in this system. Echoing many others who have already expressed support [35] for an international legal framework for pandemics, the Commission supports the establishment of a pandemic treaty which is truly global. It must include as many countries as possible; be flexible yet also enforceable; and be feasible in terms of its scope. It needs to incentivize governments and foster willingness to pool sovereign decision-making in the case of pandemics.

We also need ways to hold countries to account for contributions towards the global public goods discussed above. Drawing on insights from experiences following the global financial crisis, a Global Health Board under the auspices of the G20 could be established to promote a better assessment of the social, economic and financial consequences of health-related risks. This could largely be based on the Financial Stability Board (FSB) which has demonstrated its value during the pandemic in preventing a global liquidity crisis.

Despite the most efficient vaccine development accomplishments in history, challenges still remain with COVID-19 vaccines [36,37] and therapeutics. Huge inequalities in the availability of and access to COVID-19 vaccines persist at a global level, while manufacturing and supply chain problems continue. To prepare for future pandemics, we need a comprehensive global vaccine policy which sets out the rights and responsibilities of all parties involved in the vaccine process to ensure the availability and distribution of safe, effective, affordable, high quality vaccines for all those who need them.

8. Improve health governance in the pan-European region

COVID-19 has highlighted the world's interconnectedness and both the benefits and the risks that this brings. Europe is vulnerable to any health threat that emerges anywhere in the world and, equally, the world is vulnerable to any health threat that emerges in Europe [38]. As a region with some of the most interconnected countries anywhere, Europe faces particular challenges not least because reducing connectedness carries enormous potential consequences for the functioning of societies and economies of countries in the region. The WHO European Region is very diverse, and there are large differences across countries in wealth, population size and demographics, political systems, cultures and health. This diversity is inevitable, but it creates challenges in emergency responses when coordinated efforts are needed. COVID-19 has highlighted these competing forces – the pros and cons of interconnectedness, the value of diversity, and the importance of collaboration in crisis response.

COVID-19 has exposed the fragmentation of governance in the WHO European Region (as it has globally), with competing priorities, agendas and strategies being pursued by different agencies, countries and organizations. Health governance in the pan-European region must be reinforced and the role of and funding for WHO strengthened. Complementing the work of the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC), a Pan-European Network for Disease Control convened by the WHO Regional Office for Europe could help to strengthen early warning systems, epidemiological and laboratory capacity, and interoperability of data systems [39]. As a secretariat, the WHO Regional Office for Europe could use this platform to convene technical counterparts in Member States, and health emergency and surveillance agencies in the region to boost cooperation and harmonization of efforts in the region and beyond.

A Pan-European Health Threats Council convened by the WHO Regional Office for Europe could support an early warning system and mechanisms to track and respond to changes in pathogens and disease symptoms across the region. The body should be regionally representative and serve to enhance political commitment to pandemic and health threat preparedness using a One Health approach, and to ensure that complementarity and cooperation across the pan-European region is maximized at all levels.

The pandemic has also shed light on the need for an interoperable health data network based on common standards developed by the WHO Regional Office for Europe to enable better coordination of crisis response efforts across the region. Multilateral development banks and development finance institutions can also play a role and prioritize investments in these fields.

Of course, to support all these measures above, and to better manage and coordinate health security and preparedness across the WHO European Region and globally, the WHO needs more sustainable and flexible financing at all levels of the organization – headquarters, regional offices and country offices. Increased financing for WHO alone is not enough though. We need to address existing challenges in the operationalization of One Health, with realization of commitments to improve population health and enhancement of health systems resilience. We also need stronger governance at national and international levels with effective leadership, transparent communication, coordinated activities across stakeholder groups, stronger surveillance systems and improved organizational learning [40,41].

9. Conclusion

We, as a global community, have our work cut out for us – but, with a shift in attitude and policy priorities, our goals are within reach. It is imperative that we implement the concept of One Health in all settings and proactively adopt prevention and resilience measures in the settings where threats to sustainable health are most likely to occur [42]. We cannot allow the conditions that created the catastrophe that is the COVID-19 pandemic to continue. We owe it to all those who have suffered in its wake to strengthen governance, transparency and accountability, and to make smarter investments now to achieve more resilient and equitable societies and health systems, and so prevent similar crises occurring in the future. The recommendations of the Pan-European Commission have drawn light from the catastrophe to illuminate the way forward. Now, we must take the steps to get there – together: only by collaborating in a powerful joint effort can we succeed in implementing the changes required.

References

- 1.Garrett L. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1994. The coming plague.https://www.lauriegarrett.com/the-coming-plague [cited 2021 Sep 16]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman R., Atun R., McKee M., Mossialos E. 12 Lessons learned from the management of the coronavirus pandemic. Health Policy. 2020;124(6):577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.05.008. Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Pan-European commission on health and sustainable development. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-policy/european-programme-of-work/pan-european-commission-on-health-and-sustainable-development.

- 4.McKee M. A Review of the Evidence for the Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development. WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; Copenhagen: 2021. Evidence review. Drawing light from the pandemic: a new strategy for health and sustainable development. [Google Scholar]; Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-policy/european-programme-of-work/pan-european-commission-on-health-and-sustainable-development/publications/evidence-review.-drawing-light-from-the-pandemic-a-new-strategy-for-health-and-sustainable-development.-2021.

- 5.Pan-European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development . WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2021. Drawing light from the pandemic: a new strategy for health and sustainable development. Sep. [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Schalkwyk M.C., Maani N., Cohen J., McKee M., Petticrew M. Our Postpandemic World: What Will It Take to Build a Better Future for People and Planet? Milbank Q. 2021;99(2):467–502. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12508. Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Neill J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. Rev Antimicrob Res. 2016 https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf May. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subramanian M. Anthropocene now: influential panel votes to recognize Earth’s new epoch. Nature. 2019 May 21 doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01641-5. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01641-5 Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. One health.https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-policy/one-health Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renwick M.J., Simpkin V., Mossialos E. Targeting innovation in antibiotic drug discovery and development: The need for a One Health – One Europe – One World Framework. European Observatory Health Policy Series. 2016 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28806044/ Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson I., Hansen A., Bi P. The challenges of implementing an integrated One Health surveillance system in Australia. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65(1):e229–e236. doi: 10.1111/zph.12433. Feb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Destoumieux-Garzón D., Mavingui P., Boetsch G., Boissier J., Darriet F., Duboz P., et al. The One Health Concept: 10 Years Old and a Long Road Ahead. Front Vet Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00014. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2018.00014/full 0. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.dos S, Ribeiro C., van de Burgwal L.H.M., Regeer B.J. Overcoming challenges for designing and implementing the One Health approach: A systematic review of the literature. One Health. 2019 Mar 18;7 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2019.100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.FAO, OiE, WHO . 2017. The tripartite's commitment: providing multi-sectoral, collaborative leadership in addressing health challenges. Oct. Available from: https://www.who.int/zoonoses/tripartite_oct2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paremoer L., Nandi S., Serag H., Baum F. Covid-19 pandemic and the social determinants of health. BMJ. 2021 Jan 29;372:n129. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed F., Ahmed N., Pissarides C., Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health. 2020 May 1;5(5):e240. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheikh A., Anderson M., Albala S., Casadei B., Franklin B.D., Mike R., et al. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. The Lancet Digital health. 2021;3(6) doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00005-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33967002/ Jun Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paradies Y., Ben J., Denson N., Elias A., Priest N., Pieterse A., et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKee M., Reeves A., Clair A., Stuckler D. Living on the edge: precariousness and why it matters for health. Arch Public Health. 2017;75:13. doi: 10.1186/s13690-017-0183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Albuquerque Veloso Machado M., Roberts B., Wong B.L.H., van Kessel R., Mossialos E. The Relationship Between the COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Hesitancy: A Scoping Review of Literature Until August 2021. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:1370. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.747787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burki T. Vaccine misinformation and social media. The Lancet Digital Health. 2019 Oct 1;1(6):e258–e259. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenham C., Smith J., Davies S.E., Feng H., Grépin K.A., Harman S., et al. Women are most affected by pandemics — Lessons from past outbreaks. Nature. 2020;583(7815):194–198. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02006-z. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UN Women . Fourth World Conference on Women: Beijing Declaration. UN Women. 1995. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/declar.htm Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.UN Women. World conferences on women. UN Women. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/how-we-work/intergovernmental-support/world-conferences-on-women.

- 25.Mrazek MF, Mossialos E. Stimulating pharmaceutical research and develop- ment for neglected diseases. Health Policy. 2003;64(1) doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00138-0. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12644330/ Apr. Available from. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzucato M. Anthem Press; 2013. The entrepreneurial state: debunking public vs. private sector myths; p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., McKee M., Torbica A., Stuckler D. Systematic Literature Review on the Spread of Health-related Misinformation on Social Media. Soc Sci Med. 2019;240 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112552. Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suhrcke M., McKee M., Stuckler D., Sauto Arce R., Tsolova S., Mortensen J. The contribution of health to the economy in the European Union. Public Health. 2006;120(11):994–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.08.011. Nov. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Figueras J., McKee M. Open University Press; Berkshire, England: 2011. Health Systems, Health, Wealth and Societal Well-being: Assessing the case for investing in health systems; p. 304. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/Health-systems/health-systems-financing/publications/2011/health-systems,-health,-wealth-and-societal-well-being.-assessing-the-case-for-investing-in-health-systems-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Schalkwyk M.C., Bourek A., Kringos D.S., Siciliani L., Barry M.M., De Maeseneer J., et al. The best person (or machine) for the job: Rethinking task shifting in health care. Health Policy. 2020;124(12):1379–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.08.008. Dec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aiken L.H., Sloane D.M., Bruyneel L., Van den Heede K., Griffiths P., Busse R., et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet. 2014 May 24;383(9931):1824–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allin S., Mossialos E., McKee M., Holland W. The Wanless report and decision-making in public health. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27(2):133–134. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi014. Jun. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett S. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. Why Cooperate? The incentive to supply global public goods. Available from: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199211890.001.0001/acprof-9780199211890. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renwick M., Mossialos E. What are the economic barriers of antibiotic R&D and how can we overcome them? Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2018;13(10):889–892. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2018.1515908. Oct. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.European Council; 2021. European Council. An international treaty on pandemic prevention and pre- paredness. Available from: https://www.consilium. europa.eu/en/policies/coronavirus/pandemic-treaty/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman R., Shah S., Jeurissen P., Jit M., Mossialos E. COVID-19 vaccine challenges: What have we learned so far and what remains to be done? Health Policy. 2021;125(5) doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.03.013. May Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168851021000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forman R., Anderson M., Jit M., Mossialos E. Ensuring access and affordability through COVID-19 vaccine research and development investments: A proposal for the options market for vaccines. Vaccine. 2020 Sep 3;38(39):6075–6077. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altman S.A., Bastian P. DHL Global Connectedness Index 2020 – The State of Globalization in a Distancing World. NYU Stern School of Business. 2021:104. Available from: https://www.dhl.com/global-en/spotlight/globalization/global-connectedness-index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salas-Vega S., Haimann A., Mossialos E. Big Data and Health Care: Challenges and Opportunities for Coordinated Policy Development in the EU. Health Systems & Reform. 2015 May 19;1(4):285–300. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2015.1091538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas S, Sagan A, Larkin J, Cylus J, Figueras J, Karanikolos M. Strengthening health systems resilience: key concepts and strategies. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2020 Jun. Policy Brief 36. Available from: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/strengthening-health-system-resilience-key-concepts-and-strategies. [PubMed]

- 41.Muscat NA, Nitzan D, Figueras J, Wismar M. COVID-19 and the oppor- tunity to strengthen health system governance. Journal of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2021;27(1) Available from: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/covid-19-and-the-opportunity-to-strengthen-health-system-governance-eurohealth. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monti M., Torbica A., Mossialos E., McKee M. A new strategy for health and sustainable development in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021 Sep 18;398(10305):1029–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01995-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]