Abstract

Inundation-adapted trees were recently established as the dominant egress pathway for soil-produced methane (CH4) in forested wetlands. This raises the possibility that CH4 produced deep within the soil column can vent to the atmosphere via tree roots even when the water table (WT) is below the surface. If correct, this would challenge modelling efforts where inundation often defines the spatial extent of ecosystem CH4 production and emission. Here, we examine CH4 exchange on tree, soil and aquatic surfaces in forest experiencing a dynamic WT at three floodplain locations spanning the Amazon basin at four hydrologically distinct times from April 2017 to January 2018. Tree stem emissions were orders of magnitude larger than from soil or aquatic surface emissions and exhibited a strong relationship to WT depth below the surface (less than 0). We estimate that Amazon riparian floodplain margins with a WT < 0 contribute 2.2–3.6 Tg CH4 yr−1 to the atmosphere in addition to inundated tree emissions of approximately 12.7–21.1 Tg CH4 yr−1. Applying our approach to all tropical wetland broad-leaf trees yields an estimated non-flooded floodplain tree flux of 6.4 Tg CH4 yr−1 which, at 17% of the flooded tropical tree flux of approximately 37.1 Tg CH4 yr−1, demonstrates the importance of these ecosystems in extending the effective CH4 emitting area beyond flooded lands.

This article is part of a discussion meeting issue 'Rising methane: is warming feeding warming? (part 2)'.

Keywords: methane, Amazon, floodplain, riparian, trees, soils

1. Introduction

Methane (CH4) is the second most important greenhouse gas and wetlands constitute the largest individual source emitting an estimated 102–200 Tg of CH4 to the troposphere each year [1]. Given their importance to the atmospheric CH4 budget, there is considerable effort devoted to quantifying wetland emissions and characterizing fluxes at the global scale. A principal characteristic of so called process-based or ‘bottom up’ models of CH4 emission from wetlands is that soils and sediments are inundated in order for CH4 to be produced and emitted [2]. These models are usually parameterized against flux measurements from only soil, aquatic or herbaceous surfaces [3,4]. However, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that trees can access and transmit CH4 from within the soil column of both temperate [5–7] and subtropical and tropical wetlands [8–10]. We recently reported that tree emissions dominate the CH4 budget of the Amazon basin, with trees within the pulsing hydrological system of the floodplain contributing around half of all methane from the region [11]. The presence of wetland-adapted trees as an important egress pathway presents a more pronounced vertical dimension to previously examined emission pathways both above and below the forest floor. This complicates approaches to quantifying emissions, but yields opportunities to consider new processes of CH4 source access, entrainment and evasion.

Tree roots penetrate down to around 6 m, and up to 18 m beneath the forest floor in broad-leaved tropical forest [12]. This raises the possibility that CH4 produced deep within the soil, which would normally be consumed by soil oxidation while diffusing to the surface [13], is instead entrained within wetland tree roots that access anaerobic soil microsites. The root-entrained CH4 is then transported to the surface via the tree's vascular system and emitted from the stem surfaces. This process has been identified in a number of studies where CH4 fluxes were observed to correlate with WT depth below the soil surface at relatively shallow depths [10,14,15]. Furthermore, in ostensibly dry upland soils, trees emit CH4 from their stem bases [16,17].

Seasonal flooding along the Amazon river and its tributaries is followed by prolonged periods of low water-table and, on occasion, drought with the period of low water varying across the Amazon [18]. We explore the possibility that trees, adapted to inundation through internal architecture facilitating root aeration [19], may be emitting CH4 sourced from below the soil surface during dry conditions when the WT is below the soil surface. This opens the possibility that previous efforts to characterize CH4 fluxes from trees in the Amazon floodplain [11] during a single high water event may have missed a significant source of CH4. Gedney et al. [20] sought to characterize this below-ground WT < 0 contribution to emissions by extending a process-based CH4 emission model to incorporate a simple parameterization for a tree-mediated flux from saturated soils. However, due to a lack of available measurements from trees with a WT below the surface, they assumed a relative tree flux dependency on both WT depth and root density distributions, which they combined to produce a global wetland flux consistent with best estimates. Field measurements are therefore required to evaluate this idea fully. To better characterize the Amazon CH4 budget, we measured CH4 fluxes across four seasonal intervals for three representative Central Amazonian floodplain forests. This involved repeated visits to the same individual trees experiencing inundation and, by turn, low water.

2. CH4 flux measurements

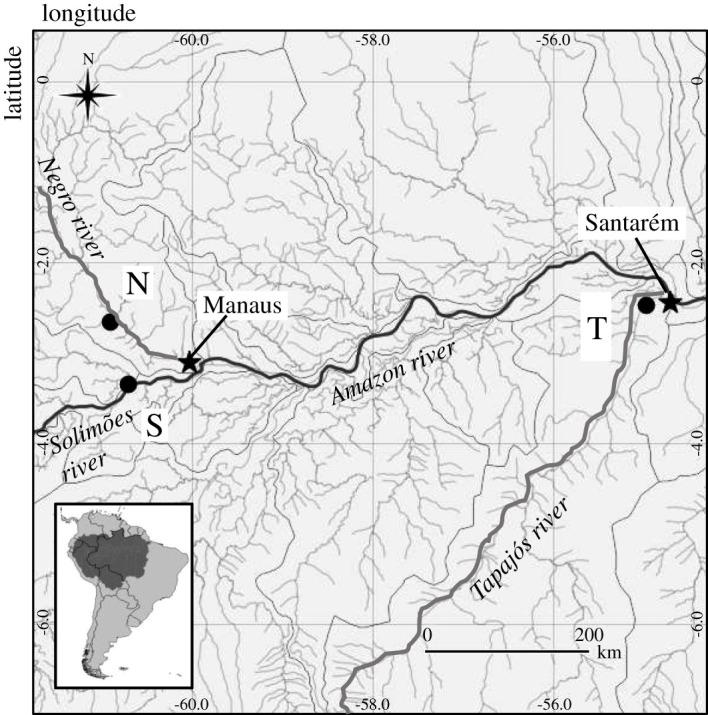

We established three plots spanning a topographic gradient from the water's edge, within seasonally flooded forests within the 1.77 million km2 reference quadrants of the central Amazon basin [21]. The temporary plots (60 × 60 m) were set up within the floodplains of three major rivers of the Amazon (figure 1): the Negro river (black water), Solimões river (white water) and Tapajós river (clear water). We quantified CH4 fluxes from a total of 108 trees (36 across each plot) at vertical intervals above the forest floor/aquatic surface across four fieldwork campaigns: rising water (campaign 1; April 2017), peak water (campaign 2; July 2017), receding water (campaign 3; October 2017) and low WT (campaign 4; January 2018). We further quantified CH4 fluxes on soil and aquatic surfaces within each plot.

Figure 1.

Map showing the locations of the three sampling sites within the floodplains of Solimões (S; white water) Negro (N; black water) and Tapajós (T; white water) rivers.

Each plot was divided into three distinct hydrological zones: (1) wet zone—closest to the river channel/lake (2) an intermediate zone and (3) dry zone—furthest away from the water source (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The plot in Solimões was an exception to this, as all three zones were of the same elevation, hence experienced similar WT depths (electronic supplementary material, table S1). In each of these plots, intensive field campaigns were carried out at the four distinct hydrological time points. At the plot level, within each of the hydrological zones (60 × 20 m), stem CH4 fluxes were measured from 12 trees, resulting in a total of 36 trees measured per plot, with the same trees measured across all four campaigns. Stem CH4 fluxes were measured at three points between 20 and 120 cm above the soil or aquatic surface (20–50 cm, 55–85 cm and 90–120 cm), depending on whether the WT level was above or below the soil surface. WT depths when above the water surface were measured using a marked, weighted cord at two locations around the tree under investigation and averaged to obtain a mean WT position. For the dry zone, the ground elevation, distance from the water body and water levels within the plot and river were recorded to calculate the relative WT levels below the soil surface. A similar approach was used during the receding and low water field campaigns when the WT was below the soil surface, where the WT level in the adjoining lake or river along with the elevation at each of the trees were measured and their distance from the water body was used to calculate the WT height.

Tree stem CH4 emissions (n = 432 per plot across all four campaigns) were measured using static chambers as described in Siegenthaler et al. [22] and Pangala et al. [11]. During inundated periods (campaigns 1 and 2), CH4 emissions from the aquatic surfaces within each plot (n = 168 per plot across the two campaigns) were measured using floating chambers as described in Bastviken et al. [23] and Pangala et al. [11]. There were no aquatic fluxes measured in campaigns 3 and 4 as the WT was below the soil surface. Soil CH4 fluxes were measured using cylindrical static chambers as described in Pangala et al. [11]; five chambers were placed within each hydrological zone where the WT was below the soil surface and as and when the WT receded additional soil chambers were installed to measure the soil flux. Therefore, soil CH4 flux measurements equated to: (a) campaign 1: n = 5 in Tapajós and Negro plot, no soil flux was measured in the Solimões plot as the entire plot was flooded, (b) campaign 2: n = 5 in the Negro plot, n = 10 in Tapajós plot as the water receded more quickly at this site relative to others and no soil flux measurement in Solimões plot and (c) campaigns 3 and 4: n = 15 in each plot.

As and when it was possible, stem and soil CH4 fluxes were measured by cavity-enhanced absorption spectroscopy (LGR ultraportable greenhouse gas analyser, ABB, Canada) as described in Pangala et al. [11]; however, when it rained or in the absence of the instrument due to repair, gas samples were extracted from the tree at T = 1, 5, 10, 15 and 20 min, T = 0, 10, 20, 30 and 40 min from soil chambers and T = 0 and 24 h from aquatic chambers. Gas samples extracted using gas tight syringes from tree stem, soil and aquatic chambers were transferred to 12 ml Labco glass vials (Labco Ltd. Ceredigion, UK) and analysed for CH4 using modified cavity ring-down laser spectroscopy [11,24]. CH4 fluxes are expressed per unit area enclosed by the chamber on the tree, soil or aquatic surface, respectively and therefore reported as mg m−2 h−1 corresponding to mg m−2 soil h−1 for soil fluxes, mg m−2 stem h−1 for tree stem fluxes and mg m−2 aquatic h−1 for aquatic fluxes (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary table of CH4 fluxes for each measured surface across all four campaigns. Large standard deviations reflect broad topographical gradients spanned within each plot and known species dependency on fluxes e.g. [8]. n = 36 for tree flux measurements at each plot per campaign. Sixty-four aquatic fluxes were made at each location during the first two campaigns only and soil flux measurement n were as follows: campaign 1: n = 5 in the Tapajós and Negro plots; campaign 2: n = 5 in the Negro plot, n = 10 in the Tapajós plot and campaigns 3 and 4: n = 15 at each plot.

| CH4 flux mg m−2 h−1 (± s.d.) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| surface | location | Apr 2017 | July 2017 | Oct 2017 | Jan 2018 |

| tree stem (20–50 cm) | s.d. | s.d. | s.d. | s.d. | |

| Solimões | 61.9 ± 68.2 | 78.9 ± 52.3 | 8.19 ± 15.7 | 0.0128 ± 0.042 | |

| Negro | 38.2 ± 53.3 | 55.8 ± 50.5 | 5.18 ± 11.8 | 0.0052 ± 0.015 | |

| Tapajós | 69.7 ± 75.8 | 9.6 ± 20.2 | 5.94 ± 11.7 | −0.0045 ± 0.007 | |

| aquatic surface | |||||

| Solimões | 1.84 ± 1.85 | 2.33 ± 18.7 | dry | dry | |

| Negro | 0.49 ± 0.48 | 0.77 ± 0.73 | dry | dry | |

| Tapajós | 1.68 ± 2.26 | 1.64 ± 1.47 | dry | dry | |

| soil surface | |||||

| Solimões | flooded | flooded | −0.022 ± 0.0435 | 0.0092 ± 0.0158 | |

| Negro | 0.027 ± 0.165 | 0.049 ± 0.9 | −0.039 ± 0.0262 | −0.0015 ± 0.0123 | |

| Tapajós | −0.013 ± 0.103 | −0.008 ± 0.031 | −0.043 ± 0.0403 | −0.0094 ± 0.0166 | |

The four selected sampling season intervals were successful in representing the full hydrological range experienced within these study tributaries in the Amazon basin (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Due to topography along each monitoring transect, Solimões had the narrowest within site water-table range, with Negro the largest. Both Solimões and Negro experienced a peak inundation in campaign 2 (July 2017) and subsequent declining water level/table with both sites experiencing below surface WT in the October 2017 and January 2018 (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, table S1). By contrast, Tapajós already had a peaking WT in campaign 1 (April 2017) with a soil surface that was only partially submerged during this peak flood. Thereafter the WT declined with WT reaching up to approximately 8 m below the soils surface.

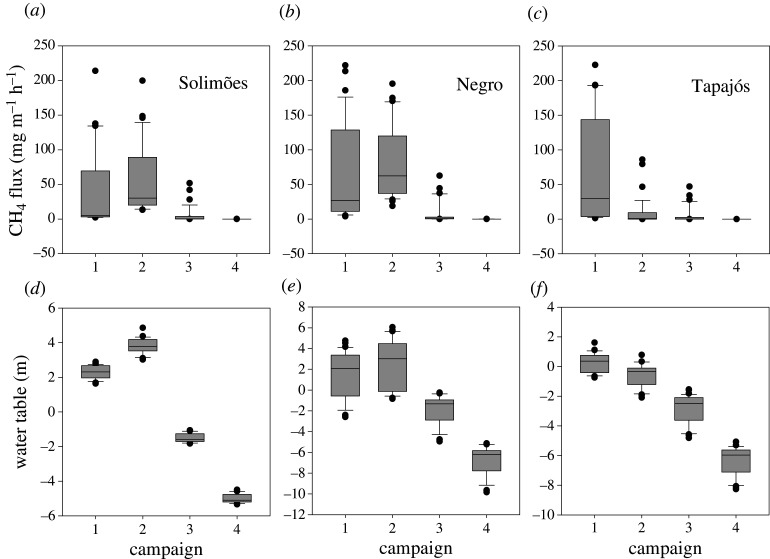

Figure 2.

Box and whisker plots of seasonal changes in tree CH4 flux measured at 20–50 cm above the forest floor (either soil or water depending on the state of flood) for the three study plots in each catchment (a–c). Figure (d–f) demonstrates the corresponding water table for each location at each seasonal time point. Campaigns 1 through 4 were carried out, respectively, during rising (campaign 1; April 2017), peak (campaign 2; July 2017), receding (campaign 3; October 2017) and low water table conditions (campaign 4; January 2018). Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles.

CH4 fluxes at the lowermost sampling position on each tree (20–50 cm above the forest floor/water surface) during rising and peak water for all three catchments were comparable to emissions observed by Pangala et al. [11] of approximately 40–80 mg CH4 m−2 h−1 (table 1) and, as in that study, stem fluxes declined with tree height. We only observed these large tree stem base fluxes during the first sampling campaign at Tapajós (table 1 and figure 2). CH4 fluxes during these rising and peak water periods were the largest recorded from any surface with aquatic and soil surface fluxes orders of magnitude smaller than those from trees (table 1). CH4 emissions declined substantially from tree stems when the water-table fell to below the soil surface in campaigns 3 and 4 (also 2 in Tapajós). While we tended to observe emissions from these sites in October and January (campaigns 3 and 4) when the WT was below the surface, the range in tree fluxes observed during the driest sampling (January) (when the WT at all sites was lower than 5 m below the soils surface (electronic supplementary material, table S1)) suggests that trees no longer accessing CH4-rich pore waters possess the capacity to switch function from CH4 emission to uptake.

3. From local to Amazon basin and tropical upscaling using JULES

To scale our findings, we first sought to establish total tree fluxes. We measured tree height, diameter at breast height (DBH), stem diameter at 10 cm intervals in the bottom-most 150 cm of exposed tree stem, along with the basal diameter for all trees within each plot. This allowed the total exposed tree surface area to be estimated for each plot across all four campaigns. The stem diameters measured between stem sampling positions of 20 and 120 cm above the forest floor/water surface, the stem surface area was calculated by considering each tree as a truncated cone that was divided into 30 cm sections [8]. The relationship established between stem position above the forest floor/water surface and corresponding stem diameter measured between 10 and 150 cm was applied to the entire length of the tree which allowed total tree flux to be estimated as described in Pangala et al. [11]. Figure 2 clearly shows that the tree mediated CH4 flux (CH4tree) is dependent on WT when it is below the soil surface.

To uncover any empirical relationships, we regressed total tree flux against WT depth (zWT). If we assume that rooting density decreases approximately exponentially with soil depth [25], then the relative number of roots beneath a specified soil depth would also decrease exponentially with depth. The tree flux originating from the saturated zone below the soil surface may therefore be described as a function of WT depth below the surface:

where C and M are tuneable parameters. This is equivalent to

| 3.1 |

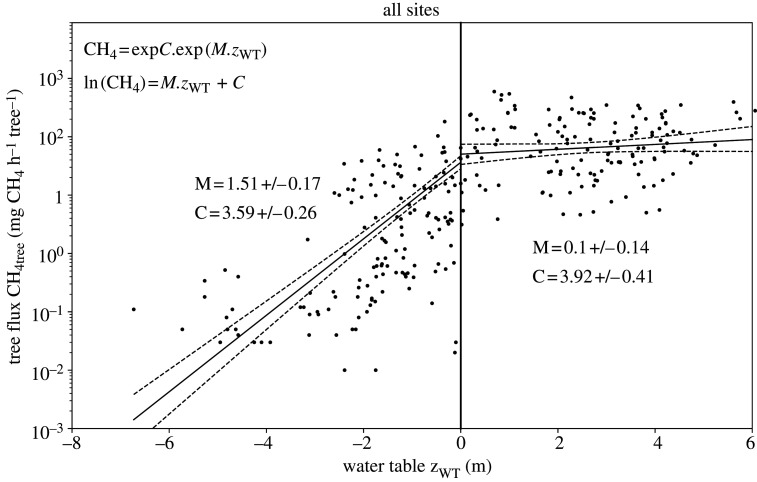

If roots are the primary facilitating factor then it might also be expected that, for WTs above the surface, the tree flux is independent of WT height. To confirm this, first we apply a linear regression to the measured WT and natural logarithm of tree flux (equation (3.1); figure 3) using data from all sites and campaigns when the WT is above the soil surface. This yields a negligible gradient M, which is not statistically significantly different from zero with M = 0.10 ± 0.14 (where the ± value is 95% confidence interval from hence forth, unless stated otherwise). Utilizing this result we apply a linear regression to all the data, but limit zWT in equation (3.1) to be no higher than the soil surface (i.e. zWT ≤ 0). This gives a gradient M of 1.51 ± 0.17 and implies roughly a 150% increase in flux per 1 m increase in zWT (d[CH4tree]/CH4tree = MdzWT).

Figure 3.

The dependence of total tree flux on water table. Measurements are shown as black dots. zWT〈0, and〉0 refer to water table below and above the soil surface, respectively. Linear regressions of ln(CH4tree) = M.zWT + C (equation (3.1)) are applied to all site data when the water table is at or above the soil surface (zWT ≥ 0), and applied to all site data but limiting zWT in equation (3.1) to be no higher than the soil surface (i.e. zWT ≤ 0) – see text for details. Mean and 95% confidence intervals are shown with solid and dashed lines, respectively.

Results of our regression analysis (figure 3) clearly demonstrate that the tree-mediated CH4 flux (CH4tree) is strongly dependent on WT depth beneath the soil surface. This is consistent with tree roots playing a facilitating role in the CH4 transfer.

To investigate the significance of this at the regional scale, we use an optimized version of the land surface model JULES ([25,26], electronic supplementary material). As well as simulating the flux of water through shallow soil layers, JULES includes a simple groundwater model which can simulate WT depth: a requirement for the regional WT dependent tree flux estimates. Although JULES lacks the detailed inundation modelling in hydrological models specifically calibrated to the Amazon (e.g. [27,28]) it is a global scheme, enabling us to estimate the magnitude of this flux over both the Amazon basin and all tropical forests. JULES combines modelled grid box mean WT depth with sub-grid topographic distribution to produce the sub-grid, WT distribution fw’(z) (see electronic supplementary material for details). The flux dependence on depth is combined with fw’(z) and tree cover to scale up the fluxes initially over the entire Amazonian forest.

Nine surface tile fractions are specified in each JULES grid-box i [29]. These are produced by remapping and reclassifying land cover maps from the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (see [29] for details). These tiles include an open water tile and five plant functional types, with broadleaf trees dominant in tropical forests. To extrapolate up from local tree density measurements from Pangala et al. [11] (electronic supplementary material), we must equate basal tree area with prescribed broadleaf tree fractional cover fblt used in JULES. In the classification scheme used in JULES evergreen broadleaf forest fblt is set as 0.85 [29]. The average tree densities measured for the Tapajós, Negro and Solimões sites is ρ(TNS) = 0.153 trees m−2. At low water, none of the sites in this study contain any open water, so we assume that the sites can be classified entirely as evergreen broadleaf forest. We therefore set the JULES broadleaf tree fraction from these sites fblt(TNS) to 0.85. We can then estimate the mean tree density for each grid box ‘i’ using the ratio of the grid box and site broad leaf tree fractions:

In each grid box, the sub-grid WT distribution fw′(z) is combined with the flux at WT depth zWT and integrated. This is scaled by the tree density to give the total ‘sub-surface’ Fsub(i) (i.e. when WT is below the surface) and surface Fsfc(i) (WT is at or above the surface) tree fluxes (mgCH4 m−2 h−1):

| 3.2 |

and

| 3.3 |

where the inundation fraction is the integral over where the WT is above the surface: . The total Amazon fluxes are calculated by multiplying each grid box flux by the grid box area and then summing over the entire basin.

To scale up over the entire basin JULES is run at 0.5° resolution and forced off-line with observed meteorology [30] for the time period 2000–2009. The vegetation and soil properties are based on those described in [29], but with a modification to allow for better tropical soils representation (electronic supplementary material). JULES, with a modified version of hydrology (electronic supplementary material), is optimized (using tuning parameter fexp) to produce the best overall simulations of inundation and WT depths, as well as successfully simulating river discharge (electronic supplementary material). fexp = 1 (ctl) simulates the overall observed spatial distribution of inundation (electronic supplementary material). It produces total Amazon inundated tree areas of 2.54 × 1011 m2 and 2.88 × 1011 m2 averaged over low water 1995 and high water 1996, and 2000–2009, respectively. These are comparable to the mean estimated using the Hess et al. [31] (electronic supplementary material, 1.61–2.63 × 1011 m2) and WAD2M [32] (2.78 × 1011 m2) data from the same respective time periods (see electronic supplementary material for details).

The simulated WT measurement errors for the default JULES version are comparable to the Fan & Miguez-Macho [33] groundwater model (electronic supplementary material). Other fexp parameter values produce slightly lower WT errors (but worse inundation extents), so we consider these in sensitivity studies (table 2).

Table 2.

Amazon tree fluxes (Tg CH4 yr−1) averaged between years 2000 and 2009. Estimates are given for different JULES hydrology tuning parameter fexp values (electronic supplementary material). Fsfc and Fsub are the inundated (WT at or above the soil surface) and riparian (WT below the soil surface) tree fluxes, respectively. Ftot is the total tree flux (Fsfc + Fsub). ‘CI’ represents results when using the 95% confidence intervals in tree flux fit, with gradients and intercepts: M = 1.51 + 0.17, C = 3.65–0.26 and M = 1.51–0.17, C = 3.59 + 0.26. Similarly, ‘s.d.’ represents the standard deviation in the fit.

| tuning parameter | Fsub | Fsfc | Ftot = Fsub + Fsfc | %Fsub/Ftot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fexp = 1 (ctl) | 2.78 | 16.35 | 19.14 | 14.5 |

| fexp = 1 lower CI | 2.16 | 12.66 | 14.83 | 14.6 |

| fexp = 1 upper CI | 3.58 | 21.13 | 24.71 | 14.5 |

| fexp = 1 − s.d. | 2.45 | 14.36 | 16.81 | 14.6 |

| fexp = 1 + s.d. | 3.16 | 18.63 | 21.79 | 14.5 |

| fexp = 0.5 | 2.37 | 13.94 | 16.31 | 14.5 |

| fexp = 0.75 | 2.63 | 15.47 | 18.10 | 14.5 |

| fexp = 1.5 | 2.99 | 17.52 | 20.52 | 14.6 |

| fexp = 2.0 | 3.19 | 18.46 | 21.64 | 14.7 |

Our best estimate modelled total tree flux for the region is 19.1 Tg CH4 yr−1 (table 2, ctl), with a range of 16.8–21.8 Tg CH4 yr−1 allowing for the standard deviation of the regression fit. This modelled total Amazon tree flux is consistent with the Pangala et al. [11] estimate range of 13.3–23.7 Tg CH4 yr−1 based on flooded area observations. It is also consistent with the modelled estimates from Gedney et al. [20] (12.3–27.0 Tg CH4 yr−1). We estimate modelled tree emissions from areas with a WT at or above the surface is 16.4 (±95% CI 12.7–21.1) Tg CH4 yr−1. Our new observation-based approach of considering trees with a WT < 0 across seasonal WT fluctuations within the Amazon pulsing system results in an additional CH4 emission of 2.8 (±95% CI 2.2–3.6) Tg CH4 yr−1 from trees with a WT below the soil surface. This is about 15% of the total modelled tree flux and demonstrates the need to include tree emitted CH4 from floodplains where the soil surface is not inundated but has a near-surface WT extending as deep as approximately 7 m beneath the soil surface.

We extend this approach by utilizing the inundation and water tables simulated by JULES over the tropical regions defined as tropical S America, tropical Asia and tropical Africa in TRANSCOM [34]. Over all broadleaf tropical forests, this gives a total additional modelled sub-surface WT tree flux of approximately 6.4 Tg CH4 yr−1 and total tropical tree flux of 43.5 Tg CH4 yr−1, i.e. floodplain riparian trees that are not inundated emit approximately 15% of total tree CH4 flux and approximately 17% of the flooded wetland tree flux.

There are many uncertainties in this estimate, however. These include both limitations in the JULES model and lack of observations. JULES is designed so it can run globally, enabling it to produce regional and global flux estimates. It does not include some of the detailed modelling and calibration of flooding in hydrological models. There is limited availability of datasets of deeper sub-surface hydrological properties, as well as sparse measurements of WT depths in this region also limiting modelling capability. There are also uncertainties in inundation extent estimates [35]. The process of extrapolation from plot measurements to regional scale implicitly assumes that these plots are representative of the region. Thus there are many challenges which limit the tree flux estimations.

In spite of the uncertainties, these first estimates demonstrate that the tree flux, both from the riparian zone and the surface flooded area, is an important contributor to global tropical estimates. For example, the standard wetland CH4 formulation of JULES (which does not explicitly represent tree fluxes) estimates a total tropical emission of approximately 96 Tg CH4 yr−1. Our estimate of 43.5 Tg CH4 yr−1 emitted from both tropical riparian (6.4 Tg) and wetland (37.1 Tg) trees is nearly half of this total tropical wetland CH4 emission estimate. This is similar in proportion to the initial estimate of tree contributions to the Amazon CH4 budget [11] with trees representing a quarter of the upper estimate for the global wetland CH4 source [1].

4. Conclusion

Our results demonstrate a clear WT dependency on the CH4 emitting function of trees within the pulsing river floodplains of the Amazon basin. Among the different CH4 emission pathways, wetland adapted trees persisted in providing the largest emissions throughout periods of rising, peak and declining water-table in the first three measurement campaigns. Thereafter, in the final measurement campaign, emissions diminished to levels that were negligible in comparison to those measured under previous campaigns such that at the driest site, Tapajós, we observed trees taking up CH4 at a rate similar to those observed in soils.

We produced a regression model of the response of tree emissions to a varying WT that demonstrated a negligible response to increasing flood level above the soil surface but a clear dependence of ‘whole tree’ CH4 emissions on WT below the soil surface. We applied this relationship within JULES to scale our findings to the entire Amazon basin and to all tropical forests and found close agreement with the observation-based estimates reported by Pangala et al. [11]. We further found that approximately 15% of all tropical broadleaf tree CH4 emissions are emitted from trees with a WT that was below the soil surface. This amounted to an additional approximately 3 Tg of CH4 emissions within the Amazon basin and an additional approximately 6 Tg CH4 yr−1 for all broadleaf tropical forests. Our findings demonstrate the clear need to use approaches that capture, not only flooded tree flux but also this soil-derived, tree-mediated source of ‘non-wetland’ but anaerobically derived CH4 from riparian trees when estimating global emissions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support from the following students who participated in the fieldwork: Ida Nilsson, Emelie Thomsen, Magdalena Lindgren, Ida Pehrson, Felicia Widing, Nina Rubensson, Pernilla Eriksson and Louise Larsson. We are also grateful for useful suggestions and discussions with David Bastviken and Humberto Marotta. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for thoughtful suggestions on a previous version.

Contributor Information

Vincent Gauci, Email: v.gauci@bham.ac.uk.

Nicola Gedney, Email: nicola.gedney@metoffice.gov.uk.

Data accessibility

All measurement data will be made available via the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis along with data from other MOYA contributors. The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [36].

Authors' contributions

V.G., N.G., S.R.P. and A.E.-P. conceived and designed the overall study. The expeditions were planned and organized by S.R.P., V.F., T.S., V.G. and A.E.-P. They were designed by S.R.P. and carried out by V.F., T.S. and S.R.P. S.R.P., V.G., N.G. and G.W. analysed the field data. N.G. performed the JULES simulations and interpreted those results. V.G., N.G. and S.R.P. wrote the manuscript with contributions from the remaining authors. All authors commented on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

V.G. and N.G. acknowledge support from the UK NERC (grant no. NE/N015606/1 & subcontract no. NEC05779 resp.) as part of The Global Methane Budget MOYA consortium. N.G. was also supported by the Newton Fund through the Met Office Climate Science for Service Partnership Brazil (CSSP Brazil). S.R.P. acknowledges support from the Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Research fellowship (DH160111). A.E.-P. acknowledges support from the Brazilian funding agencies CNPq, CAPES and FAPERJ grants supported part of the work.

References

- 1.Saunois M, et al. 2020. The global methane budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1561-1623. ( 10.5194/essd-12-1561-2020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulter B, et al. 2017. Global wetland contribution to 2000–2012 atmospheric methane growth rate dynamics. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 094013. ( 10.1088/1748-9326/aa8391) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter BP, Heimann M. 2000. A process-based, climate-sensitive model to derive methane emissions from natural wetlands: application to five wetland sites, sensitivity to model parameters, and climate. Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 14, 745-765. ( 10.1029/1999GB001204) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melton JR, et al. 2013. Present state of global wetland extent and wetland methane modelling: conclusions from a model inter-comparison project (WETCHIMP). Biogeosciences 10, 753-788. ( 10.5194/bg-10-753-2013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terazawa K, Ishizuka S, Sakata T, Yamada K, Takahashi M. 2007. Methane emissions from stems of Fraxinus mandshurica var. japonica trees in a floodplain forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 2689-2692. ( 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauci V, Gowing DJ, Hornibrook ER, Davis JM, Dise NB. 2010. Woody stem methane emission in mature wetland alder trees. Atmos. Environ. 44, 2157-2160. ( 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.02.034) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pangala SR, Hornibrook ER, Gowing DJ, Gauci V. 2015. The contribution of trees to ecosystem methane emissions in a temperate forested wetland. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2642-2654. ( 10.1111/gcb.12891) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pangala SR, Moore S, Hornibrook ER, Gauci V. 2013. Trees are major conduits for methane egress from tropical forested wetlands. New Phytol. 197, 524-531. ( 10.1111/nph.12031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjögersten S, Siegenthaler A, Lopez OR, Aplin P, Turner B, Gauci V. 2020. Methane emissions from tree stems in neotropical peatlands. New Phytol. 225, 769-781. ( 10.1111/nph.16178) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffrey LC, Maher DT, Tait DR, Euler S, Johnston SG. 2020. Tree stem methane emissions from subtropical lowland forest (Melaleuca quinquenervia) regulated by local and seasonal hydrology. Biogeochemistry 151, 273-290. ( 10.1007/s10533-020-00726-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pangala SR, et al. 2017. Large emissions from floodplain trees close the Amazon methane budget. Nature 552, 230-234. ( 10.1038/nature24639) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadell J, Jackson RB, Ehleringer JB, Mooney HA, Sala OE, Schulze ED. 1996. Maximum rooting depth of vegetation types at the global scale. Oecologia 108, 583-595. ( 10.1007/BF00329030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Mer J, Roger P. 2001. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: a review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 37, 25-50. ( 10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01067-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pangala SR, Gowing DJ, Hornibrook ER, Gauci V. 2014. Controls on methane emissions from Alnus glutinosa saplings. New Phytol. 201, 887-896. ( 10.1111/nph.12561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terazawa K, Yamada K, Ohno Y, Sakata T, Ishizuka S. 2015. Spatial and temporal variability in methane emissions from tree stems of Fraxinus mandshurica in a cool-temperate floodplain forest. Biogeochemistry 123, 349-362. ( 10.1007/s10533-015-0070-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitz S, Megonigal JP. 2017. Temperate forest methane sink diminished by tree emissions. New Phytol. 214, 1432-1439. ( 10.1111/nph.14559) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welch B, Gauci V, Sayer EJ. 2019. Tree stem bases are sources of CH4 and N2O in a tropical forest on upland soil during the dry to wet season transition. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 361-372. ( 10.1111/gcb.14498) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parolin P, Lucas C, Piedade MT, Wittmann F. 2010. Drought responses of flood-tolerant trees in Amazonian floodplains. Ann. Bot. 105, 129-139. ( 10.1093/aob/mcp258) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parolin P. 2009. Submerged in darkness: adaptations to prolonged submergence by woody species of the Amazonian floodplains. Ann. Bot. 103, 359-376. ( 10.1093/aob/mcn216) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gedney N, Huntingford C, Comyn-Platt E, Wiltshire A. 2019. Significant feedbacks of wetland methane release on climate change and the causes of their uncertainty. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 084027. ( 10.1088/1748-9326/ab2726) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melack JM, Hess LL, Gastil M, Forsberg BR, Hamilton SK, Lima IB, Novo EM. 2004. Regionalization of methane emissions in the Amazon Basin with microwave remote sensing. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 530-544. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00763.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegenthaler A, Welch B, Pangala SR, Peacock M, Gauci V. 2016. Semi-rigid chambers for methane gas flux measurements on tree stems. Biogeosciences 13, 1197-1207. ( 10.5194/bg-13-1197-2016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastviken D, Cole JJ, Pace ML, Van de Bogert MC. 2008. Fates of methane from different lake habitats: connecting whole-lake budgets and CH4 emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 113. ( 10.1029/2007JG000608) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird AJ, Stamp I, Heppell CM, Green SM. 2010. CH4 flux from peatlands: a new measurement method. Ecohydrology 3, 360-367. ( 10.1002/eco.109) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark DB, et al. 2011. The joint UK land environment simulator (JULES), model description–Part 2: carbon fluxes and vegetation dynamics. Geoscientific Model Dev. 4, 701-722. ( 10.5194/gmd-4-701-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Best MJ, et al. 2011. The joint UK land environment simulator (JULES), model description–Part 1: energy and water fluxes. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 677-699. ( 10.5194/gmd-4-677-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paiva RCD, Buarque DC, Collischonn W, Bonnet MP, Frappart F, Calmant S, Mendes CAB. 2013. Large-scale hydrologic and hydrodynamic modeling of the Amazon River basin. Water Resour. Res. 49, 1226-1243. ( 10.1002/wrcr.20067) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coe MT, Costa MH, Howard E. 2007. Simulating the surface waters of the Amazon River basin: impacts of new river geomorphic and dynamic flow parameterizations. Hydrol. Processes 22, 2542-2553. ( 10.1002/hyp.6850) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiltshire AJ, Duran Rojas MC, Edwards JM, Gedney N, Harper AB, Hartley AJ, Hendry MA, Robertson E, Smout-Day K. 2020. JULES-GL7: the global land configuration of the joint UK land environment simulator version 7.0 and 7.2. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 483-505. ( 10.5194/gmd-13-483-2020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weedon GP, Balsamo G, Bellouin N, Gomes S, Best MJ, Viterbo P. 2014. The WFDEI meteorological forcing data set: WATCH Forcing data methodology applied to ERA-Interim reanalysis data. Water Resour. Res. 50, 7505-7514. ( 10.1002/2014WR015638) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess LL, Melack JM, Affonso AG, Barbosa C, Gastil-Buhl M, Novo EM. 2015. Wetlands of the lowland Amazon basin: extent, vegetative cover, and dual-season inundated area as mapped with JERS-1 synthetic aperture radar. Wetlands 35, 745-756. ( 10.1007/s13157-015-0666-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, et al. 2021. Development of the global dataset of Wetland Area and Dynamics for Methane Modeling (WAD2M). Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 13, 2001-2023. ( 10.5194/essd-13-2001-2021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan Y, Miguez-Macho G. 2010. Potential groundwater contribution to Amazon evapotranspiration. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 2039-2056. ( 10.5194/hess-14-2039-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurney KR, et al. 2003. TransCom 3 CO2 inversion intercomparison: 1. Annual mean control results and sensitivity to transport and prior flux information. Tellus B: Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 55, 555-579. ( 10.3402/tellusb.v55i2.16728) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson NC, Fluet-Chouinard E, Finlayson CM. 2018. Global extent and distribution of wetlands: trends and issues. Mar. Freshwater Res. 69, 620-627. ( 10.1071/MF17019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gauci V, Figueiredo V, Gedney N, Pangala SR, Stauffer T, Weedon GP, Enrich-Prast A. 2021. Non-flooded riparian Amazon trees are a regionally significant methane source. Figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All measurement data will be made available via the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis along with data from other MOYA contributors. The data are provided in electronic supplementary material [36].