Abstract

Microbial metabolite mimicry is a new concept that promises to deliver compounds that have minimal liabilities and enhanced therapeutic effects in a host. In a previous publication, we have shown that microbial metabolites of L-tryptophan, indoles, when chemically altered, yielded potent anti-inflammatory pregnane X Receptor (PXR)-targeting lead compounds, FKK5 and FKK6, targeting intestinal inflammation. Our aim in this study was to further define structure-activity relationships between indole analogs and PXR, we removed the phenyl-sulfonyl group or replaced the pyridyl residue with imidazolopyridyl of FKK6. Our results showed that while removal of the phenyl-sulfonyl group from FKK6 (now called CVK003) shifts agonist activity away from PXR towards the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), the imidazolopyridyl addition preserves PXR activity in vitro. However, when these compounds are administered to mice, that unlike the parent molecule, FKK6, they exhibit poor induction of PXR target genes in the intestines and the liver. These data suggest that modifications of FKK6 specifically in the pyridyl moiety can result in compounds with weak PXR activity in vivo. These observations are a significant step forward for understanding the structure-activity relationships (SAR) between indole mimics and receptors, PXR and AhR.

Keywords: pregnane X receptor, microbial mimics, tryptophan catabolites, intestinal inflammation

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The pregnane X receptor (PXR; NR1I2) is an orphan nuclear receptor, which is transcriptionally activated by a number of structurally unrelated compounds. In the initial period, following the discovery of the PXR, it was also referred to as steroid and xenobiotic sensing nuclear receptor (SXR), because its known activators comprised xenobiotics and steroids. Xenobiotic ligands of the PXR were found to induce drug-metabolizing genes, resulting in pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions [1]. The roles of the PXR in the transcriptional regulation of CYP2/3 families, phase II enzymes and some drug transporters are now firmly established. Therefore, the PXR had long time been regarded as an enfant terrible in the drug discovery, whose activation by a candidate drug is undesirable. Nowadays, physiological roles for the PXR are known, such as the transcriptional control of intermediary metabolism of lipids, carbohydrates and bile acids, renal mitochondrial metabolism [2] or endothelium-dependent vasodilatation [3]. Accordingly, endogenous ligands of the PXR, including estrogens, bile acids and vitamin K2, were identified, thus, the PXR was de-orphanized. The involvement of the PXR in the etiology of many diseases including Alzheimer disease [4], inflammatory bowel disease [5], cancer [6] or diabetes [7], was unveiled. Collectively, given the broad and pivotal roles of the PXR in human physiology and patho-physiology, therapeutic targeting of the PXR with both agonists and antagonists is of topical interest [6].

Based on prior work from our laboratory that links microbial derived indoles as PXR ligands with intestinal barrier control [8], we hypothesize that in rodents and humans, extreme concentrations of microbial-derived indoles correlate with resolution of inflammation; however, at a population level, the cytoplasmic retention and reduction of PXR limits complete resolution of inflammation and is in part attributed to weak overall in vivo activation of human PXR by these metabolites [9]. Thus, improving metabolite ligand potency while preserving minimal compound liabilities, is a compelling rationale for the discovery of novel and safe PXR-targeted drugs for IBD. Thus far the indole metabolite medicinal chemistry has mainly focused on developing indole-pharmacophore based drugs, however, not specifically as PXR ligands [10]. Indeed, while some databases have few indole-like structures that do bind and activate PXR [11–14], there is no formal or focused effort defining the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of a focused library built around bis-indole motif. Overall, it is clear that engaging the appropriate activation of PXR in the setting of colitis using drug-like ligands that are essentially non-toxic to the host and have a locoregionally (intestine-specific) restricted pharmacology (no systemic exposure), will be the ideal way to create a paradigm shift in IBD therapeutics. In IBD, there is an inappropriately low level of PXR activation in colonic tissues, largely through loss of endogenous ligands [8, 15–17]. Thus, pharmacologic activation in this setting will not overdrive the receptor but keep the receptor engaged in a physiologically active state using moderately potent ligands (as if the system were replaced with endogenous ligands). This physiologic re-establishment of PXR signaling in the setting of intestinal inflammation is consistent with our companion work on PXR, that the receptor can paradoxically induce a selective pro-inflammatory state (e.g., IL1β) to prevent pathogenic bacterial invasion and further limit intestinal pathology (unpublished observations, [18]).

One possible strategy is to exploit off-targeting the PXR with existing approved drugs, which are ligands of the PXR. Whereas these compounds have their on-targets, their translational potential is high due to their routine use in clinical pharmacotherapy for years. Another approach to identify novel PXR ligands is a screening of chemical libraries and ad hoc compounds (natural, synthetic) in high-throughput assays. Finally, tailored synthesis, which may also take advantage from former approaches, seems to be most suitable way to obtain potent, efficacious and selective PXR ligands. Inspired by nature, we have proposed that metabolites produced by a human microbiota might be a treasure trove for using biomimicry to discover and optimize drugs [19]. Indeed, human microbiota that colonizes barrier organs including intestines, skin and lungs, produces the wide array of compounds, which account for on-site and distant biological effects. A distinct group of microbial metabolites is formed from dietary amino acid tryptophan. We have reported that tryptophan microbial catabolites indole (IND) and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) synergistically activate mouse PXR [8], and that IND and indole-3-acetamide are ligands and agonists of human PXR [20]. A series of compounds derived from IND and IPA (referred to as FKK) were designed, synthesized and demonstrated as medium-potency / high-efficacy agonists, and medium-affinity ligands of human PXR, displaying in vivo anti-colitis effects in mice, and anti-inflammatory effects in human cancer cells and intestinal organoids [21]. In our published study of the concept of microbial metabolite mimicry [19], we described the first proof of potent lead analogs of indole/IPA pharmacophore, FKK5 and FKK6[21]. Here we report the synthesis, in vitro and in vivo studies with novel series of microbial indole-based compounds generated from FKK5 and FKK6 (referred to as CVK), which were derived from parental FKK series by either removal of phenyl-sulfonyl group or by replacement of pyridyl residue with imidazolopyridyl.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and rifampicin (RIF) were from Sigma Aldrich (Prague, Czech Republic). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) was from Ultra Scientific (RI, USA). FuGENE® HD Transfection reagent and reporter lysis buffer were from Promega (Hercules, CA, USA). All other chemicals were of the highest quality commercially available.

CVK-LN compounds

All chemical reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. Chromatography was performed on a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash Rf 200i using disposable silica cartridges. Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Merck silica gel plates and compounds were visualized using UV. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 300 or 600 MHz spectrometers. The Bruker 600 NMR instrument was purchased using funds from NIH award 1S10OD016305. 1H chemical shifts (δ) are reported relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS, 0.00 ppm) as an internal standard or relative to residual solvent signals.

Synthesis of 1-(1H-indol-2-yl)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)but-3-yn-1-ol (2/CVK-003):

In a vial 1-(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)but-3-yn-1-ol (75 mg, 0.186 mmol) was dissolved in dry MeOH and THF mixture (3:1 mL). Slowly warmed the reaction mixture to dissolve completely. Magnesium (67.9 mg, 2.80 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture and sonicated at 35 °C. Reaction was monitored by TLC. After 3 h reaction was diluted by adding DCM (10 mL). Transferred into a separatory funnel and washed the organic layer with 0.5 M HCl (2×5 mL), then with 1 M NaHCO3 (3×10 mL) and with Brine. Organic phase was dried over Na2SO4. Filtered and remove solvents under reduce pressure. Purified the crude using silica chromatography (CombiFlash 5% MeOH in DCM) to get the product 1-(1H-indol-2-yl)-1-(pyridin-4-yl)but-3-yn-1-ol in 21% yield. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.48 (d, J= 5.5 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (d, J =5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 3.33 (s, 1H), 3.25 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 155.2, 148.1, 141.4, 136.8, 127.9, 121.9, 121.2, 119.8, 118.7, 110.7, 99.54, 79.1, 73.1, 71.4, 31.

Synthesis of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-7-yl(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)methanol (3/CVK-017):

In a flame-dried and Ar-flushed round bottom flask with a stir bar and a septum, THF (1 mL) was added and cooled to 0°C. N-butyllithium (0.311 mL, 0.777 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture. A solution of 1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indole (200 mg, 0.777 mmol) in dry THF 1.5 mL) was then slowly added over 10 min at 0°C. After stirring for 30 min at 0°C, the mixture was cooled to −78°C for 10 min. Then, added imidazo[1,2-α]pyridine-7-carbaldehyde (148 mg, 1.010 mmol) in THF (1 mL) (aldehyde is not dissolved in THF, warmed to dissolve). Reaction was gradually warmed to RT and monitored by Mass Spectroscopy. Stirred overnight. After stirring for 16 h, reaction was quenched by adding saturated NH4Cl (10 mL). This was extracted with EtOAc (3×10 mL). Solvents were removed and purified using CombiFlash (0–10% Methanol in DCM) to give the product imidazo[1,2-α]pyridin-7-yl(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)methanol in 25% yield. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (s, 1H), 7.86 (s, 2H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 19.4 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 3H), 7.34 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (s, 1H), 6.47 (s, 1H), 6.37 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.1, 142.5, 138.7, 137.5, 136.7, 134.07, 129.5, 129.2, 128.5, 126.3, 125.3, 125.2, 124.0, 121.4, 115.6, 115.3, 114.7, 112.4, 112.0, 68.1.

Synthesis of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-7-yl(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)methanone (4/CVK016):

In a flame-dried 50 mL RB flask with stir bar and septum, Dess-Martin periodinane (123 mg, 0.290 mmol) was suspended in Dichloromethane (2 mL) and cooled to 0°C (ice bath). A solution of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-7-yl(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)methanol (78 mg, 0.193 mmol) (200 mg, 0.549 mmol) in dry Dichloromethane 5 mL was slowly added over 5 min. The mixture was kept stirring, while the ice bath was allowed to melt slowly. After 2 h, TLC analysis indicated complete conversion. The mixture was poured into 10 mL saturated aq. sodium thiosulfate solution and EtOAc (20 mL) were added, the mixture was shaken vigorously, and the layers separated. The organic layer was washed with saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate (20 mL), and brine (20 mL), then dried (Na2SO4), filtered and evaporated. Purified using Combiflash (0–5% MeOH in DCM) gave a light yellow foam. This was further purified using a second silica column using 0–50% Acetone in DCM. Fractions with the product were pooled together. Solvents were removed and the product was dissolved in minimum amount of acetone and precipitated out with hexane. Filtered the crystals and rinsed the product with EtOAc to remove remaining impurities.

Synthesis of 1-(imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-7-yl)-1-(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)but-3-yn-1-ol (5/CVK-021):

Step-1: A flame-dried 2-neck Schlenk flask, reflux condenser, addition funnel and stir bar was set up. Magnesium (0.385 g, 15.84 mmol) and mercury(II) chloride (10.03 mg, 0.037 mmol) were added in to the flask. The apparatus was, connected to vacuum and purge with Ar. The addition funnel was filled with diethyl ether (7 mL) and diethyl ether (Ratio: 1.000, Volume: 2 mL) was added to the reaction. Then pre-dried (dried over MS 4Å for overnight) 3-bromoprop-1-yne (0.5 mL, 5.28 mmol) was added to the addition funnel containing remaining 5 mL ether. About 1 mL of the propargyl bromide solution was added to the reaction and the mixture warmed with the heat gun until boiling started. Boiled up two more times, while adding a few more drops of the bromide. After Mg turnips turned dark gray the reaction Cooled to 0°C in an ice bath. The remaining bromide was set up to add dropwise over (25 min) at this temperature. Ice bath removed. Stirred for another 1.5 h before allowing to settle. Transferred the solution into a pre-dried Schlenk flask using cannula. Concentration of prop-2-yn-1-ylmagnesium bromide was conformed as 0.72 M (Titration with phenanthroline/menthol; orange color). Use directly to the next step.

Step-2: A round bottom flask with a stir bar was charged with imidazo[1,2-a]pyridin-7-yl(1-(phenylsulfonyl)-1H-indol-2-yl)methanone (53 mg, 0.132 mmol) and THF (4 mL). Cooled the mixture to 0 °C. Then prop-2-yn-1-ylmagnesium bromide (0.550 mL, 0.396 mmol) was added dropwise. Reaction was gradually warmed to RT. Reaction was monitored using Mass Spectroscopy. After 1 h added another 0.7 mL of Grinard reagent and stirred for 48 h. Reaction was quenched by adding saturated NH4Cl (2 mL) to the reaction mixture. Transferred the mixture into a separative funnel and extracted with EtOAc. Organic phase was dried over Na2SO4 and rotovaped to remove all solvents. The crude was purified using CombiFlash. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.43 (m, 5H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.21 (s, 1H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 5.32 (s, 0H), 3.20 (s, 2H), 2.11 (s, 1H), 1.70 (s, 1H), 1.29–1.32 (m, 3H), 0.99 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 0H), 0.86–0.92 (m, 3H); 13C-NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.1, 142.8, 141.2, 138.6, 138.0, 134.6, 133.3, 128.8, 128.3, 125.7, 125.0, 124.3, 121.6, 115.2, 113.8, 111.8, 110.8, 79.7, 74.9, 72.8, 35.3, 31.5, 22.7, 14.3. and 13C-NMR Data (see Supplementary Figure 1)

Cell cultures

Caucasian colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 was purchased from European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC No. 87021202). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, as recommended by supplier. LS174T cells (ATCC: CL-188; 7 000 3535) (Synthego Corporation, Redwood City, CA, USA) were the parental cells used to generate PXR knockout variant LS174-PXR-KO, using CRISPR Cas9 technology, as we described and validated recently [21]. Stably transfected reporter gene cell line AZ-AHR was as described elsewhere [22]. Primary human hepatocyte cultures were of two origins: (i) Long-term primary human hepatocytes in monolayer batch Hep2201016 (male, 66 years, Caucasian), Hep2201020 (male, 75 years, Caucasian), Hep2201029 (male, 89 years), Hep2201032 (male, 43 years, Caucasian) were purchased from Biopredic International (Rennes, France). (ii) Primary human hepatocytes from multiorgan donor LH79 (male, 60 years, Caucasian) were prepared at Palacky University Olomouc. Liver tissue was obtained from Faculty Hospital Olomouc, Czech Republic, and the tissue acquisition protocol followed the requirements issued by “Ethical Committee of the Faculty Hospital Olomouc, Czech Republic” and Transplantation law #285/2002 Coll.

Reporter gene assays

Transcriptional activity of AhR was assessed using the stably transfected gene reporter cells AZ-AHR [22]. Intestinal LS180 cells transiently transfected by lipofection (FuGENE® HD Transfection Reagent) with pSG5-hPXR expression plasmid along with a luciferase reporter plasmid p3A4-luc were used for assessment of PXR transcriptional activity [21]. Cells were incubated with tested compounds as indicated in detail in figure legends. Thereafter, the cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured on Tecan Infinite M200 Pro plate reader (Schoeller Instruments, Czech Republic). Incubations were carried out in quadruplicates (technical replicates).

Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

Cells or primary human hepatocytes from five different donors (Hep2201016, Hep2201020, Hep2201029, Hep2201032, LH79) were incubated for 24 h with test compounds; the vehicle was DMSO (0.1% v/v). Total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent® (Molecular Research Center, Ohio, USA). qRT–PCR determination of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP3A4, MDR1 and GAPDH mRNAs was performed as described elsewhere [21], using LightCycler® 480 Probes Master on a LightCycler® 480 II apparatus (Roche Diagnostic Corporation). For the mouse tissue studies (n = 3 mice/treatment group), CYP3A11 and MDR1a primers and qRT-PCR conditions were used as previously published [21]. Each PCR run was performed in quadruplicates (technical replicates).

Time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET)

The LanthaScreen® TR-FRET PXR (SXR) Competitive Binding Assay Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to determine the binding of CVK compounds on PXR. Assay was performed as described previously [23]. Fluorescence was measured on Tecan Infinite F200 Pro Plate Reader (Schoeller Instruments, Czech Republic). The TR-FRET ratio was calculated by dividing the emission signal at 520 nm by that at 495 nm. Binding assays were done in at least four independent experiments, and IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) applying standard curve interpolation (sigmoidal, 4PL, variable slope).

Human studies

Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division / University of Chicago Medical Center issued on 30th September 2016 an approval for study “Characterization of Pregnane X receptor (PXR) in Inflammatory Bowel Disease” (# IRB16–0894) (data in Figure 1, Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 2). In addition, IBD tissue and specimens (de-identified) were obtained through approval of the Committee on Clinical Investigations (CCI) of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY (CCI#2007–554). The colonoscopy aspirate or fecal collection study that was collected under Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved studies for aspirate or fecal collections (#2015–4465; #2009–446; #2007–554). The patients eligible for colonoscopy were enrolled sequentially after they provided study consent (#2015–4465; audited by the IRB on April 24, 2019; NCT04089501). All patients were screened and evaluated by a single gastroenterologist and inflammatory bowel disease specialist (DL). Patients were enrolled if they had a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or Ulcerative colitis) or were undergoing routine screening colonoscopy for colorectal polyps/cancer screening or required a colonoscopy as part of their medical management of any gastrointestinal disorder as clinically indicated. All pathology was evaluated at Montefiore Hospital (QL, AA) using published criteria [24, 25].

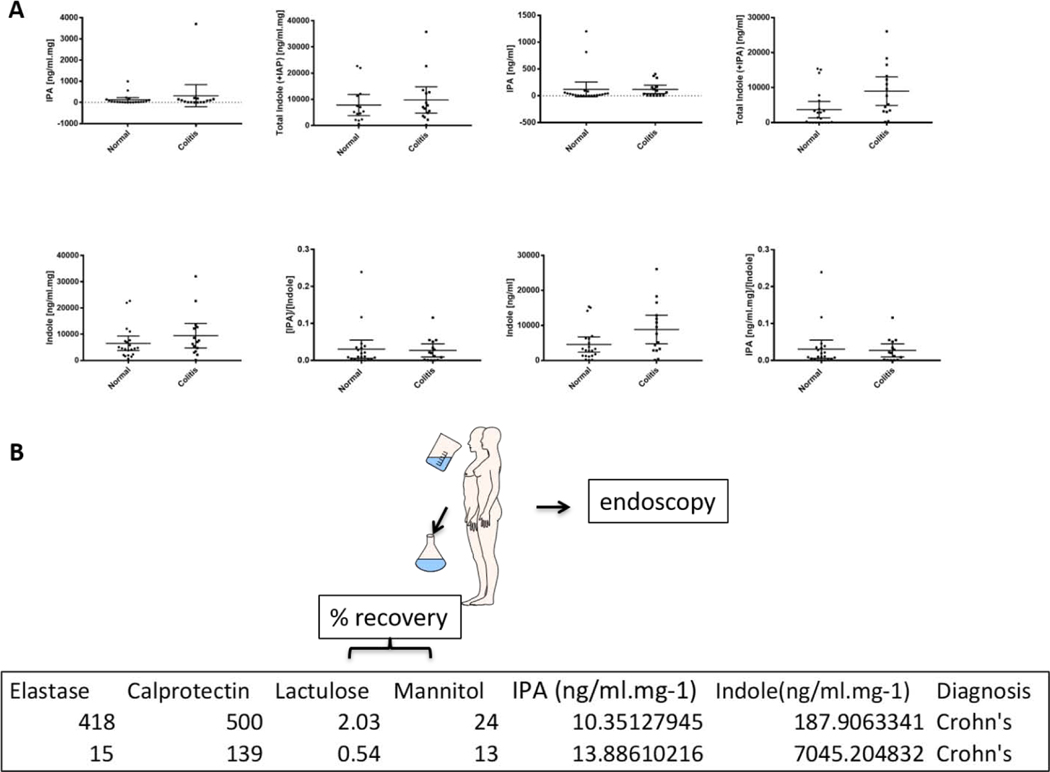

Figure 1.

Panel A: Indole and indole 3-propionic acid (IPA) levels in colonoscopy aspirates. Specimens were obtained from unselected patients with inflammatory bowel disease (acute and chronic, Crohn’s (n = 9) and Ulcerative colitis; n = 6) (mean age 52 years, 8 males: 7 females) as well as non-inflammatory bowel disease patients (n = 21; mean age 57 years, 10 males; 11 females). The figure panels, as captioned, represent IPA, indole, or total indole plus IPA or a ratio of the IPA to indole concentration in a normalized to total aspirate protein concentrations or in given volume of aspirate, respectively. The student t-test, for any given figure panel mean (95% CI), is not significant (p > 0.05). Panel B: Relationship between colonoscopy aspirate indole and IPA concentrations and intestinal inflammation and permeability in two patients with Crohn’s colitis. A single time-point colonoscopy assessment was performed in two patients with active Crohn’s colitis (CC). Colonoscopy aspirates were sent for assessment of markers of inflammation (elastase [μg/g], calprotectin [μg/g]) as well as for indole/IPA concentrations by MS-MS. Intestinal permeability was assessed prior to the colonoscopy procedure via the Intestinal Permeability Test (Urine) (Genova Diagnostics, Ashville, NC). Lactulose and mannitol values represent percent recovery of the initial dose administered via a drinking solution (as illustrated).

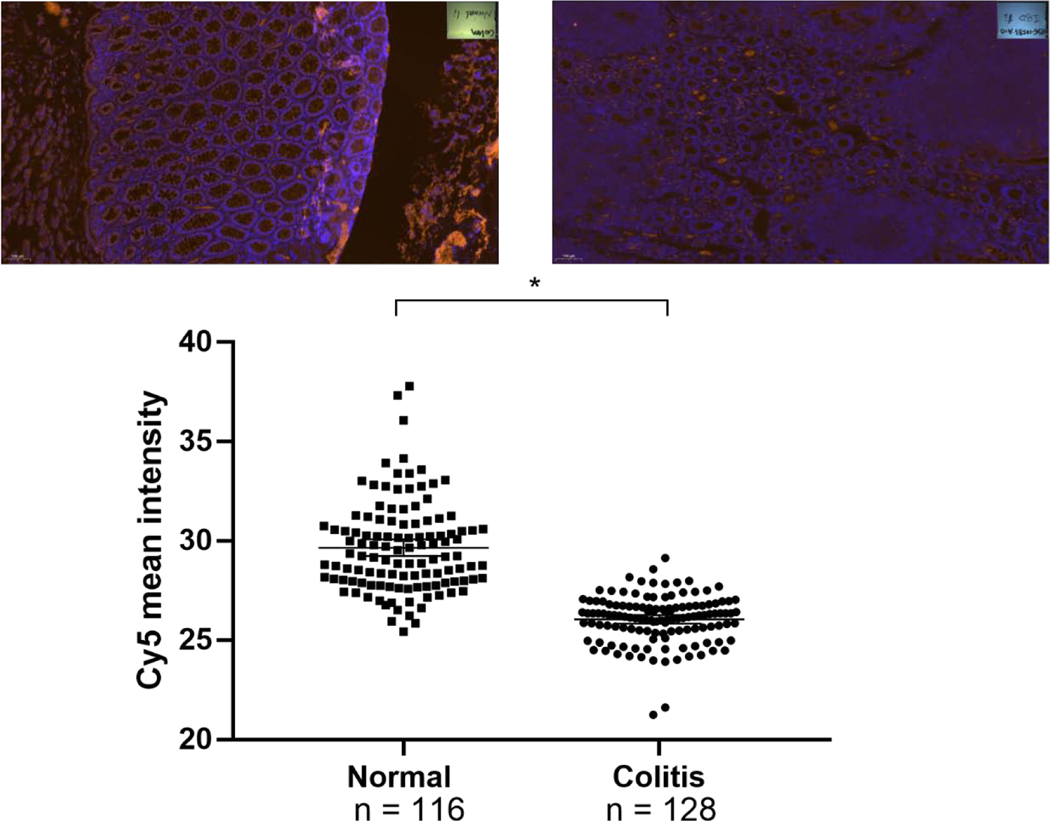

Figure 2. PXR expression by immunofluorescence (IF) in colon sections from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

In a unselected retrospective survey of cases of inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s/CC, N = 25 and Ulcerative colitis/UC, N = 22), random histologic specimens were evaluated for PXR expression using GTX81102 (Gentex,CA) (UC, N = 5 with CC, N = 5 slides from two patients with each diagnosis). For all slides, n =116 glands from “normal, non-inflamed histology” and n = 128 glands from colitis affected areas were assessed for immunofluorescence intensity. Each point on the dot plot represents fluorescence intensity value (ratio of strong positive pixels to total pixels counted). Representative IF stains are shown above as “colon normal” and “IBD LI, large intestine”; n, total number of glands scored in all slides examined; signal reports mean (95%CI) * p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test.

Animal studies

Male and female mice expressing the human PXR gene (hPXR) [Taconic, C57BL/6-Nr1i2tm1(NR1I2)Arte (9,104, females; 9,104, males), 6–10 weeks] were administered 10% DMSO (n = 3) or CVK-021 (n = 3) in 3 or 5 doses (500 μM/dose), with each dose interval of 12 h. The vivarium conditions were identical to our prior studies [21]. Animal studies were approved by the Institute of Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, INC (IACUC # 20160706, 20160701 and preceding protocols), and specific animal protocols were also approved by additional protocols (IACUC# 20170406, 20170504).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human colonic tissue from patients who underwent ileocolectomy (for CC) or total proctocolectomy (for UC) underwent antigen retrieval at pH 6 in target retrieval solution (Dako). Duplicate sections were then stained separately with two different anti-human PXR antibodies. A rabbit polyclonal anti-PXR (Gene Tex, Inc., Irvine, CA; GTX81102) antibody was used at a dilution of 1:100. This primary antibody was detected with EnVision+ System-HRP anti-rabbit reagent and developed with a DAB substrate kit (Cell Marque). The second anti-PXR antibody was a goat polyclonal (LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc., Seattle, WA; LS-B3968–50) used at a dilution of 1:30 (16.7 μg/mL). This was detected using an HRP-labeled donkey anti goat IgG secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, Inc., West Grove, PA) diluted 1:500 in wash buffer and visualized with a DAB kit (Cell Marque). A blocking peptide (LS-E26983) was used in some slides to ensure blocking of antibody staining.

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin embedded human normal and IBD intestine slides (5 μm thickness) were incubated with PXR antibody (cat# GTX81102, Genetex, CA 92606, USA; dilution 1:20). The secondary antibody was Alexia Fluor 647 (cat# 4414S, Cell Signaling, MA 01923, USA; dilution 1:100) and slides were set using 50 μL Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA 94010). The slides were scanned by 3D Histech P250 High Capacity Slide Scanner. The whole images were scanned by CaseViewer Version 2.2. The Alexia-647 stained cells (crypts and glands) were circled and analyzed by ImageJ.

Pixel density quantitation

Slides were scanned on the 3D Histech Panoramic 250 Flash II slide scanner in the Analytical Imaging Facility at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY using a 20X objective. Brown stain analysis was completed on the whole piece of tissue on each slide with 3D Histec’s QuantCenter software, using the DensitoQuant module. In this module, brown stain pixels are distinguished from the rest of the tissue by color thresh-holding. Brown pixels are detected in a range from light brown to dark brown. A thresh-hold is set in the software to distinguish a range of light brown (negative) from a range of dark brown (positive) pixels. The same thresh-hold is used for all slides and data is displayed as percent negative and percent positive pixels.

Cheminformatics

In silico assessment of drug-likeness (and lead-like rule) [21], ADME (2D descriptors calculated by topomol module followed by Resilient back-propagation [Rprop]) and toxicity prediction was conducted using the PreADMET software v.2.0 (Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea).

Statistical Analysis

For the analysis of mouse gene expression in tissues, tissue expression was analysed using unpaired multiple t-test without assuming consistent standard deviation across the data. The significance level α = 0.05 was set correcting for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method (Prism for Mac, v8.4.3).

RESULTS

Indole and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) levels in colonoscopy aspirates from healthy versus IBD patients

Given the importance of L-tryptophan metabolites in mammalian physiology and pathophysiology, the past decade has witnessed a significant rise in papers relating to host effects and targets relating to tryptophan metabolites [26–30]. Our laboratories demonstrated that multiple indole/indole metabolites could co-activate human PXR and directly regulate intestinal immunity and inflammation via a TLR4 pathway in mice [8, 31–33]. In this context, in our unselected serial colonoscopy aspirates from patients and normal volunteers seen in the IBD clinic, the levels of indole or indole metabolite, IPA, were highly variable and not significantly different in IBD (Crohn’s and Ulcerative colitis, n = 15) cases versus “non-inflammatory bowel disease” controls (n = 21) (Figure 1A). Interestingly, within patients undergoing colonoscopy, we compared the indole and IPA levels in two Crohn’s colitis patients (one with high level of inflammation and the other with low level of inflammation) with intestinal permeability (Figure 1B). Indole and IPA levels in their endoscopic aspirates were inversely proportional to the degree of intestinal inflammation and permeability.

PXR expression in colon sections from IBD patients

In a large unselected random cohort of archived IBD cases (Crohn’s n = 25, and Ulcerative Colitis n = 22, respectively), PXR protein expression is present in both the acutely involved and non-inflamed mucosal epithelia. PXR expression is quantitatively higher in IBD (inflamed) versus normal (non-inflamed) mucosa (Supplementary Figure 2) [34]. On the contrary, we performed immunofluorescence staining, where the quantitation is more accurate, the net staining, predominantly observed in the cytoplasm, is significantly less in IBD versus controls (Figure 2). A caveat to be considered is that the IF staining was performed in only two randomly selected patient cases and further confirmation is awaited from larger studies. It is important to emphasize that the subcellular localization of PXR in human samples has only been modestly evaluated – while it is well documented, after ligand tethering to interact with NF-κB and other target genes when residing in the nucleus [35–40].

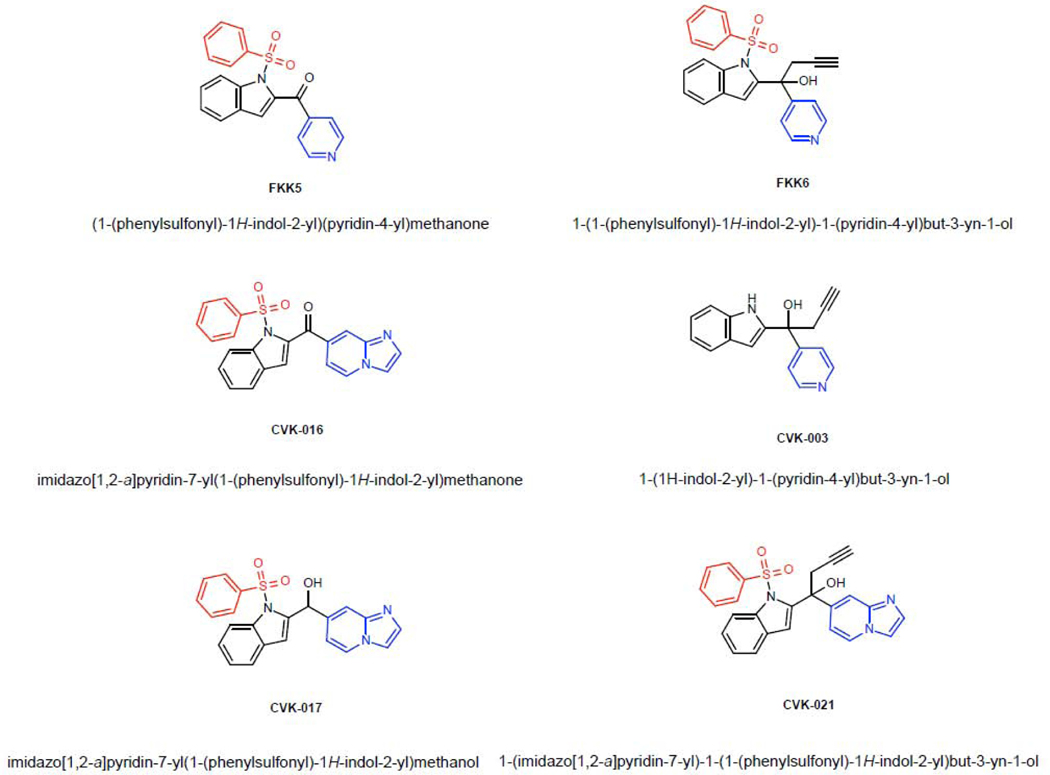

Development of chemical mimics of the indole-IPA pharmacophore

We had built a small indole analog library based on a collection of intermediates of bis-indole synthesis and demonstrated two structures, FKK5 and FKK6, as hits for therapeutic lead development [21]. Incidentally, FKK6 also has very specific PXR isoform activity (Supplementary Figure 3). There are three critical modules in the FKK5/6 structures that confer their PXR-selective activity – the phenylsulfonyl group (red), the indole (black), and the pyridyl group (blue) (Figure 3). We observed that the introduction of the additional indol-2-yl group led to the acquisition of the AhR activity and the AhR/PXR-dual agonists, and further removal of phenyl sulfonyl group resulted in AhR supra-agonist compounds [21]. Here, we focused on eliminating or altering the phenylsulfonyl or pyridinyl group (Figure 3). To limit systemic absorption, we decided to alter the hydrophobicity of the pyridyl group by deriving fused ring structures (Figure 3). Of twenty-two compounds schematically conceived (CVK), PXR ligand binding domain (LBD) docking revealed good scores (data not shown) for four compounds, CVK-003, CVK-016, CVK-017, CVK-021 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of FKK and CVK series.

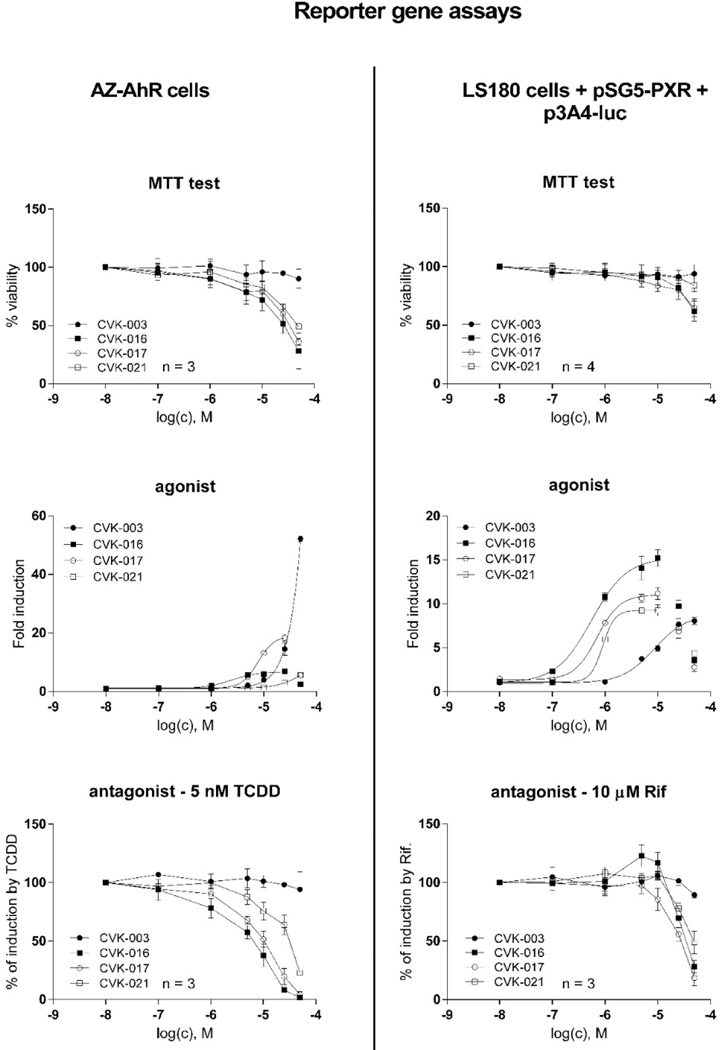

Activation of PXR and AhR by CVK compounds in reporter gene assays

Using reporter gene assay in intestinal LS180 cells, transiently transfected with pSG5-hPXR vector and p3A4-luc reporter, we show that all tested CVKs dose-dependently activate PXR, with efficacies (EMAX) comparable to a model PXR ligand rifampicin. The potencies (EC50) of CVK-016, CVK-017 and CVK-021 were approx. 0.8 μM, whereas CVK-003 was much less potent with EC50 7.5 μM. Dose-dependent antagonist effects of CVK-016, CVK-017 and CVK-021 were observed; however, these compounds were slightly cytotoxic at 50 μM, and a drop of luciferase activity superior to 10 μM concentration of CVKs occurred also in agonist mode (Figure 4). Hence, all tested CVKs display full PXR agonistic activity up to 10 μM concentration. We also carried out counter-screen in stably transfected AZ-AHR reporter cell, because many compounds are dual ligands and activators of PXR and AhR. We observed strong and moderate AhR agonistic activities for CVK-003 and CVK-017, respectively. Dose-dependent inhibition of TCDD-inducible luciferase activity by CVK-016, CVK-017 and CVK-021 was rather due to the cytotoxic effects in AZ-AHR cells (Figure 4). The reporter gene data indicate that the elimination of the phenylsulfonyl group from FKK6, which yields CVK-003 (Figure 3), causes the substantial decrease of potency against the PXR. In parallel, a resulting free indole moiety (not protected by phenylsulfonyl), imposes strong AhR agonist activity on CVK-003.

Figure 4. Activation of PXR and AhR by CVK compounds in reporter gene assays.

Cell line LS180 was transiently co-transfected with p3A4-luc reporter plasmid and pSG5-hPXR vector; AZ-AHR cells are stably transfected reporter human hepatoma cells. Cells were incubated for 24 h with vehicle (DMSO, 0.1% v/v) and /or tested CVK compounds in concentrations up to 50 μM. Incubations were in the presence (antagonist mode) or in the absence (agonist mode) of AhR ligand TCDD (5 nM) or PXR ligand RIF (10 μM). Experiments were performed in three consecutive cell passages. Each treatment was carried out in four technical replicates (culture wells). Upper panel: MTT test, data expressed as percentage of viability; Middle panel: Agonist mode. data are expressed as a fold induction over a negative control (representative experiments from one cell passage are shown in the plots.); Lower panel: Antagonist mode. Data are expressed as a percentage of maximal induction attained by 10 μM RIF and/or 5 nM TCDD.

Expression of PXR- and AhR-target genes by CVK compounds in human intestinal and hepatic cells

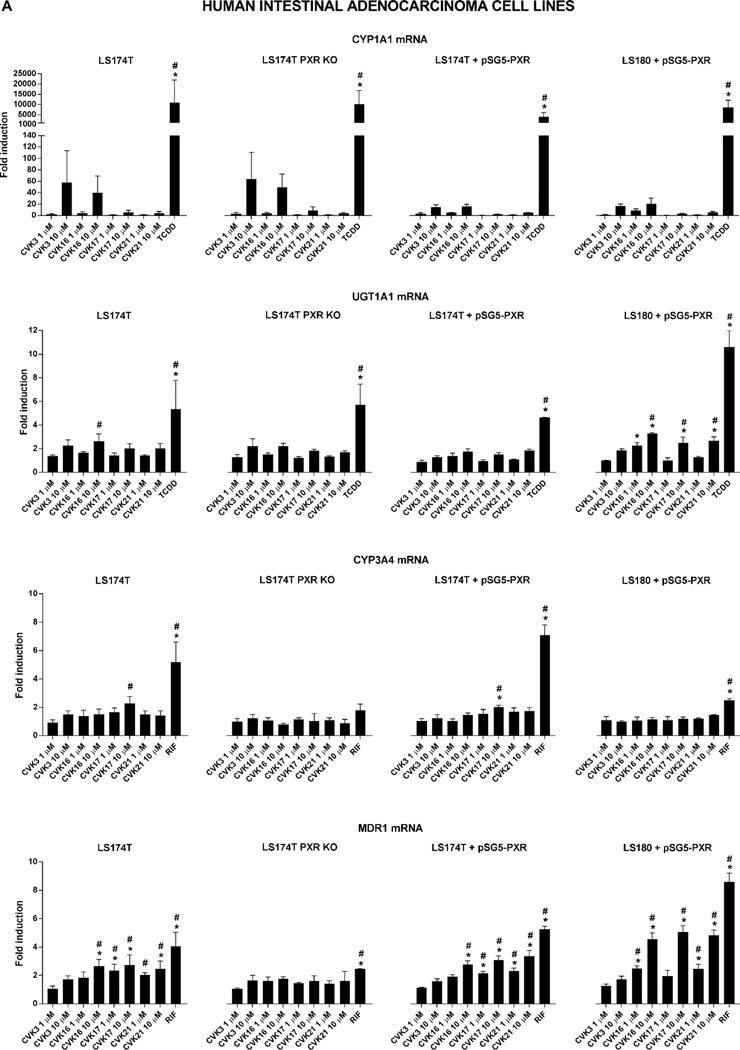

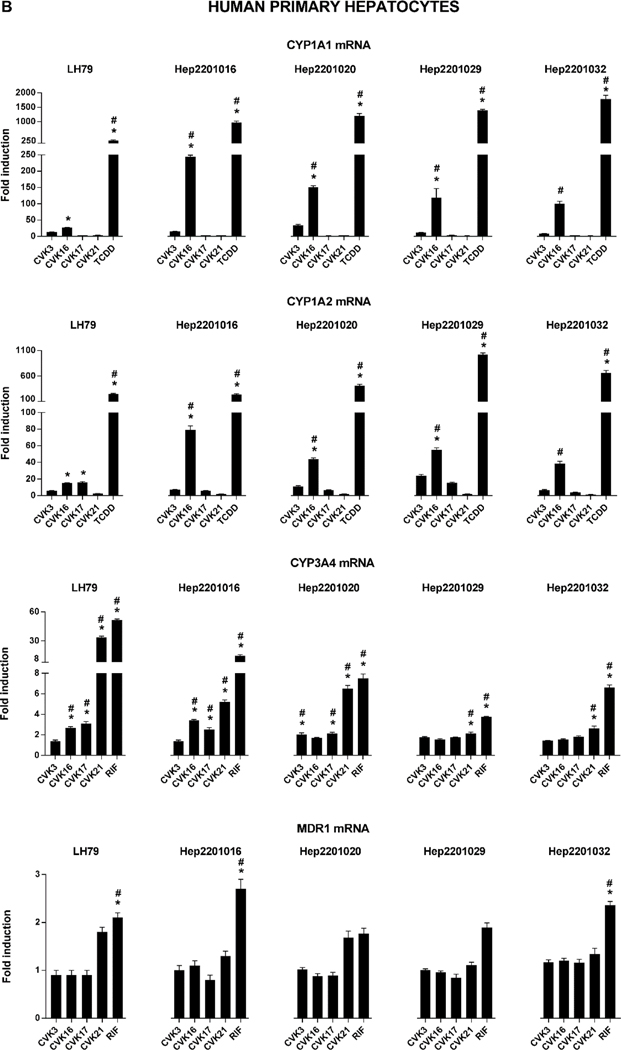

The expression of AhR/PXR-regulated genes by CVK compounds was examined in primary cultures of human hepatocytes in a monolayer, and in four different models based on human intestinal adenocarcinoma cells, including wild-type LS174T cells, PXR-KO LS174T cells, and LS174T/LS180 cells transiently transfected with human PXR expression vector. Intestinal CYP1A1 and UGT1A1, as model AhR-regulated genes, were not induced by CVK compounds in any of the models used, with exception of weak increase of UGT1A1 mRNA in LS180 cells (Figure 5A). In contrast, hepatic CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 mRNAs were significantly induced by CVK-016 in human hepatocytes from five different donors (Figure 5B), implying a metabolic activation of CVK-016 into AhR-active species. Dose-dependent induction of MDR1 was achieved by CVK-016, CVK-017 and CVK-021 in LS174T, LS174T+PXR and LS180+PXR cells, whereas no effects were observed in PXR-KO LS174T cells, which corroborates the involvement of the PXR in the MDR1 induction by CVK compounds. On the other hand, MDR1 is only weakly inducible in human hepatocytes, hence, we observed an induction only by rifampicin and only in three hepatocytes cultures. Finally, CVKs induced CYP3A4 mRNA in human hepatocytes, but not in intestinal cells; the strongest effects were displayed by CVK-021, which significantly induced CYP3A4 mRNA in all five human hepatocytes cultures. Collectively, CVKs induced CYP3A4 in hepatic, but not intestinal cells, whereas opposite effects were observed with MDR1 (Figure 5A, Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Expression of PXR- and AhR-target genes by CVK compounds.

Cells were incubated for 24 h with CVK compounds (10 μM), TCDD (10 nM) and/or RIF (10 μM). The levels of CYP1A1/2, CYP3A4 and MDR1 mRNAs were determined using qRT-PCR. Analyses were done in triplicates (technical replicates). The data were normalized per GAPDH, as a housekeeping gene. Panel A: Human intestinal adenocarcinoma LS174T cells (wild-type, PXR-knock-out, PXR-transfected) and LS180 cells (PXR-transfected). Experiments were carried out in three consecutive cell passages (one well per treatment); Panel B: Long-term primary cultures of human hepatocytes (5 donors). * p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA test; # p < 0.05, Two-way ANOVA test; a borderline 2-fold induction was applied to perform statistical tests.

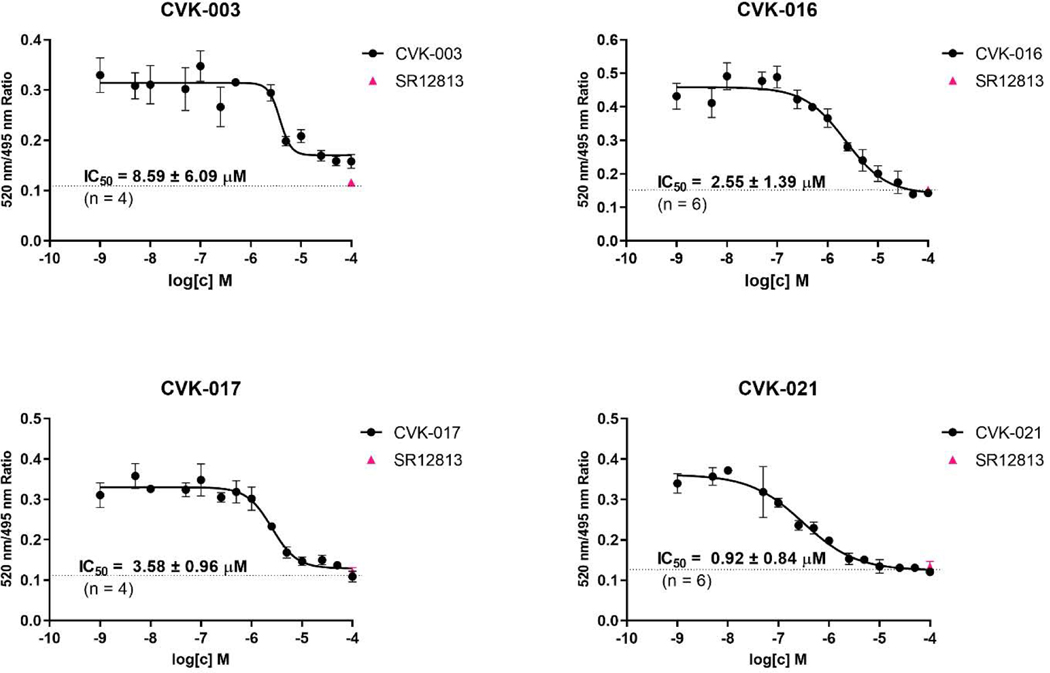

Binding of CVK compounds on PXR – time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET)

The ability of CVK compounds to interact with ligand-binding domain of human PXR was examined by TR-FRET assay (LanthaScreen®). All tested CVK dose-dependently displaced fluorescent ligand from binding on PXR. The highest affinity was displayed by CVK-021 (IC50 0.92 μM), whereas CVK-003 was an order of magnitude less affinity ligand, which further corroborates the essence of phenylsulfonyl group in the interaction with the PXR (IC50 8.59 μM) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Binding of CVK compounds on PXR – TR-FRET assay.

Ratio 520 nm / 495 nm was plotted against concentration of CVK compounds. Half-maximal inhibitory concentrations IC50 were obtained from interpolated standard curves (sigmoidal, variable slope), and are indicated in plots. Experiments were performed at least four times and the representative plots are shown. The presented data are mean ± SE from quadruplicates (technical replicates). Positive control SR12813 (100 μM) is depicted as a single point at the dashed line inserted in each plot.

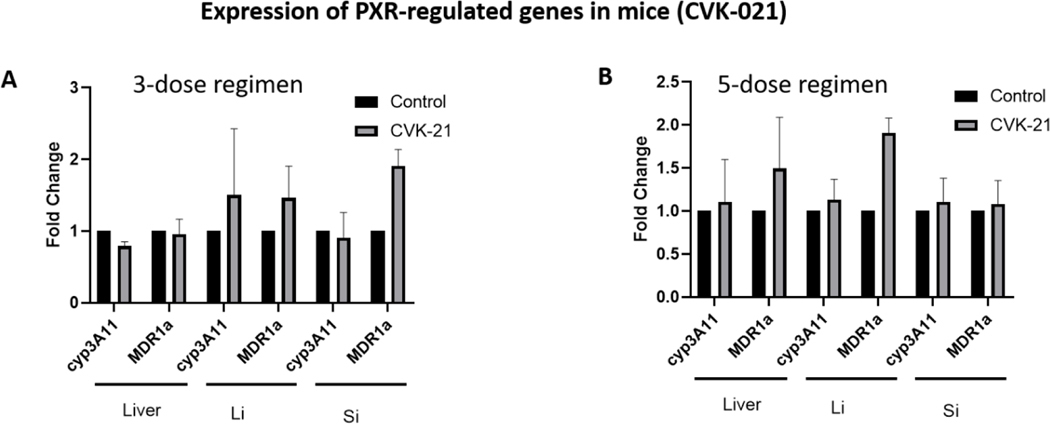

In vivo gene expression in mice expressing the human PXR transgene

We have previously published on FKK6 and its effects on induction of PXR target genes, CYP3A11 and MDR1a, in mouse tissues (small and large intestines, liver). The FKK doses studied included a 3-dose and a 5-dose regimen with each dose interval being 12 h. To be consistent and to compare results of CVK-021 with FKK6 in mice, we used the same dose and schedule for CVK-021 as previously published [21]. There is no significant induction (≥ 2) of the mean mRNA expression levels of CYP3A11 or MDR1a in any of the mouse tissues examined (Figure 7). However, increased gene expression was observed for MDR1a in the large and small intestines (Figure 7A) and in the liver and the large intestine (Figure 7B). In both CVK-021 doses (3-dose and 5-dose study), gene expression of CYP3A11 was not affected (Figure 7).

Figure 7. CVK-021 induction of PXR target genes expression in mice carrying the human PXR transgene.

Male and female mice expressing the human PXR gene [Taconic, C57BL/6-Nr1i2tm1(NR1I2)Arte] were administered 10% DMSO (n = 3: 1 male, 2 females ) or CVK-021 (n = 3: 1 male, 2 females) in 3 or 10% DMSO (n = 3: 1 male, 2 females) or CVK-021 (n = 3: 1 male, 2 females) in 5 doses (500 μM/dose), with each dose interval of 12 h. The levels of CYP3A11 and MDR1a mRNAs were determined in liver, large intestine (Li) and small intestine (Si) by the means of qRT-PCR.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our study shows that in IBD, the pregnane X receptor (PXR) is down-regulated and indeed localized to the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus. This makes the protein inactive as far as its gene transcription function and interactions with NF-κB [41, 42]. The microbial L-tryptophan metabolite pathway is highly variable in humans and while extremes of abundance of these metabolites correlate with functional consequences on intestinal permeability and inflammation, stronger ligands that can return PXR function to physiologic levels is necessary to abrogate intestinal inflammation. We have previously demonstrated that microbial specific metabolites of L-tryptophan in a mammalian intestine can serve as an endogenous ligand for the human pregnane X receptor (PXR) [8]. Subsequently, we developed chemical mimics of the indole-IPA binding pharmacophore on PXR, FKK5 and FKK6 [21]. These compounds showed potent anti-inflammatory activity in rodents with colitis [21]. To expand on the SARs of indole analogs as it relates to PXR and AhR, we developed analogs of FKK6.

Our results show that FKK6 with removal of phenyl-sulfonyl group (CVK-003), results in strong AhR agonist activity, unlike what is observed with FKK6, which was a selective PXR agonist [21]. These results inform on the necessity of retaining the phenyl-sulfonyl group for PXR activity or lack of AhR activity. On the other hand, the replacement of pyridyl residue with imidazolopyridyl on FKK6, resulted in strong PXR activity in vitro. However, in mice administered CVK-021, a lead imidazolopyridyl analog of FKK6, there was no biologically discernible induction of PXR target genes (CYP3A11, MDR1a) in the intestines or the liver. On the contrary, FKK6 robustly induced PXR target genes in the intestines or the liver depending on the dose schedule administered [21]. These data suggest that significant modification (e.g., imidazolopyridyl) may make the compound less metabolically stable in vivo. While we have not demonstrated the metabolic stability of CVK compounds in vivo, the fact that the lead compound, CVK-021, does not induce PXR target genes in mice suggests that either the compound is metabolized to non-PXR activating molecules or that it does not reach its target in vivo. The latter is highly unlikely given the fact that from oral gavage it is likely that CVK-021 transits through the small intestines or is absorbed prior to that, and would have to enter the liver via the portal system. It is also possible that CVK-021 is unstable in solution or gastric juices causing degradation in vivo. All these possibilities further delimit the utility of the imidazolopyridyl for improvement over FKK6.

There are other limitations of our study that restrain broad generalisations of the analogs with respect to PXR and AhR activity. First, only a limited set of imidazolopyridyl analogs were studied. It is conceivable that further modifications of the imidazolopyridyl group would provide the compound with stability in vivo. Second, limited phenyl-sulfonyl group modifications were studied; here, only the loss of this group was demonstrated as being salient for PXR-specific activity. Third, since these compounds were not efficacious PXR activators in mice, there was no follow-up performed for the efficacy of these compounds in murine colitis. These limitations will be overcome in the future as more analogs are synthesized and screened in vitro and in vivo. This study also highlights the fact that both in vitro and in vivo analysis of the compound analog is necessary in order to completely understand its utility in PXR-directed therapies.

The results of our study show that extensive modifications of select chemical groups, likely very divergent from close mimicry of the original metabolite pharmacophore, could essentially result in target inactivity in vivo. These studies allow us to focus on the indole ring itself for further enhancement of potency and/or drug likeness.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The abundance of indole and indole 3-propionate (IPA) are variable in human feces

Very high and very low values are found in patients with IBD

PXR protein expression is reduced in human colon samples from IBD patients

Molecular mimicry of indole/indole 3-propionic acid (IPA) is feasible

Essential structural features for indole-based PXR agonist effect were defined

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ondřej Ženata for qRT-PCR measurements in LS174T WT and PXR-KO cells. We thank Dr. John Hart from the University of Chicago for helping access deidentified pathology specimens (AURA IRB: IRB16-0894).

FUNDING

We acknowledge financial support from Czech Science Foundation [19-00236S]; the student grant from Palacký University in Olomouc [PrF-2020-006]; NIH Instrument Award (1S10OD019961-01); LTQ Orbitrap Velos Mass Spectrometer System (1S10RR029398); NIH CTSA (1UL1TR001073); the ICTR Pilot Award (AECOM); Grant #362520 Broad Medical Research Program (BMRP, not Litwin) at CCFA (Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America); NIH grants CA127231 and CA 161879; Department of Defense Partnering PI (W81XWH-17-1-0479; PR160167; ES030197).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IPA

Indole-3-propionic acid

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- RIF

rifampicin

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The studies presented here are included in a patent submitted by The Albert Einstein College of Medicine in conjunction with Palacký University and The Drexel University College of Medicine to the US Patent and Trademark Office.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lehmann JM, et al. , The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest, 1998. 102(5): p. 1016–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu X, et al. , Nuclear receptor PXR targets AKR1B7 to protect mitochondrial metabolism and renal function in AKI. Sci Transl Med, 2020. 12(543). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulakazhi Venu VK, et al. , The pregnane X receptor and its microbiota-derived ligand indole 3-propionic acid regulate endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2019. 317(2): p. E350–E361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain S, et al. , Pregnane X Receptor and P-glycoprotein: a connexion for Alzheimer’s disease management. Mol Divers, 2014. 18(4): p. 895–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng J, Shah YM, and Gonzalez FJ, Pregnane X receptor as a target for treatment of inflammatory bowel disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2012. 33(6): p. 323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai SC, Wright WC, and Chen T, Strategies for developing pregnane X receptor antagonists: Implications from metabolism to cancer. Med Res Rev, 2020. 40(3): p. 1061–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukkanen J, Hakkola J, and Rysa J, Pregnane X receptor (PXR)--a contributor to the diabetes epidemic? Drug Metabol Drug Interact, 2014. 29(1): p. 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatesh M, et al. , Symbiotic bacterial metabolites regulate gastrointestinal barrier function via the xenobiotic sensor PXR and Toll-like receptor 4. Immunity, 2014. 41(2): p. 296–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squires EJ, Sueyoshi T, and Negishi M, Cytoplasmic Localization of Pregnane X Receptor and Ligand-dependent Nuclear Translocation in Mouse Liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2004. 279(47): p. 49307–49314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chadha N. and Silakari O, Indoles as therapeutics of interest in medicinal chemistry: Bird’s eye view. Eur J Med Chem, 2017. 134: p. 159–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ratajewski M, et al. , Screening of a chemical library reveals novel PXR-activating pharmacologic compounds. Toxicol Lett, 2015. 232(1): p. 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla SJ, et al. , Identification of clinically used drugs that activate pregnane X receptors. Drug Metab Dispos, 2011. 39(1): p. 151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dring AM, et al. , Rational quantitative structure-activity relationship (RQSAR) screen for PXR and CAR isoform-specific nuclear receptor ligands. Chem Biol Interact, 2010. 188(3): p. 512–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pondugula SR, et al. , Diindolylmethane, a naturally occurring compound, induces CYP3A4 and MDR1 gene expression by activating human PXR. Toxicol Lett, 2014. 232(3): p. 580–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson A, et al. , Attenuation of bile acid-mediated FXR and PXR activation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep, 2020. 10(1): p. 1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding X, et al. , Tryptophan Metabolism, Regulatory T Cells, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Mini Review. Mediators Inflamm, 2020. 2020: p. 9706140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huhn M, et al. , Inflammation-Induced Mucosal KYNU Expression Identifies Human Ileal Crohn’s Disease. J Clin Med, 2020. 9(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little M, et al. , Understanding the Physiological Functions of the Host Xenobiotic-sensing Nuclear Receptors PXR and CAR on the Gut Microbiome using Genetically Modified Mice. BMC Preprint (Research Square), 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dvorak Z, et al. , Weak Microbial Metabolites: a Treasure Trove for Using Biomimicry to Discover and Optimize Drugs. Mol Pharmacol, 2020. 98(4): p. 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Illes P, et al. , Indole microbial intestinal metabolites expand the repertoire of ligands and agonists of the human pregnane X receptor. Toxicol Lett, 2020. 334: p. 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dvorak Z, et al. , Targeting the pregnane X receptor using microbial metabolite mimicry. EMBO Mol Med, 2020. 12(4): p. e11621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novotna A, Pavek P, and Dvorak Z, Novel stably transfected gene reporter human hepatoma cell line for assessment of aryl hydrocarbon receptor transcriptional activity: construction and characterization. Environ Sci Technol, 2011. 45(23): p. 10133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vyhlidalova B, et al. , Differential activation of human pregnane X receptor PXR by isomeric mono-methylated indoles in intestinal and hepatic in vitro models. Toxicol Lett, 2020. 324: p. 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magro F, et al. , European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis, 2013. 7(10): p. 827–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feakins RM, Inflammatory bowel disease biopsies: updated British Society of Gastroenterology reporting guidelines. J Clin Pathol, 2013. 66(12): p. 1005–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ, and Ruas JL, Kynurenines: Tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science, 2017. 357(6349). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang LS and Davies SS, Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions. Genome Med, 2016. 8(1): p. 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernstrom JD, A Perspective on the Safety of Supplemental Tryptophan Based on Its Metabolic Fates. J Nutr, 2016. 146(12): p. 2601s–2608s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamas B, et al. , CARD9 impacts colitis by altering gut microbiota metabolism of tryptophan into aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands. Nat Med, 2016. 22(6): p. 598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothhammer V, et al. , Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Med, 2016. 22(6): p. 586–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mani S, Indole microbial metabolites: expanding and translating target(s). Oncotarget, 2017. 8(32): p. 52014–52015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranhotra HS, et al. , Xenobiotic Receptor-Mediated Regulation of Intestinal Barrier Function and Innate Immunity. Nucl Receptor Res, 2016. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brave M, Lukin DJ, and Mani S, Microbial control of intestinal innate immunity. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(24): p. 19962–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blokzijl H, et al. , Decreased P-glycoprotein (P-gp/MDR1) expression in inflamed human intestinal epithelium is independent of PXR protein levels. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2007. 13(6): p. 710–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yokobori K, et al. , Intracellular localization of pregnane X receptor in HepG2 cells cultured by the hanging drop method. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, 2017. 32(5): p. 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dash AK, et al. , Heterodimerization of Retinoid X Receptor with Xenobiotic Receptor partners occurs in the cytoplasmic compartment: Mechanistic insights of events in living cells. Exp Cell Res, 2017. 360(2): p. 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Winkel A, et al. , Expression, localization and polymorphisms of the nuclear receptor PXR in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol, 2011. 11: p. 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matic M, et al. , A novel approach to investigate the subcellular distribution of nuclear receptors in vivo. Nucl Recept Signal, 2009. 7: p. e004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saradhi M, et al. , Pregnane and Xenobiotic Receptor (PXR/SXR) resides predominantly in the nuclear compartment of the interphase cell and associates with the condensed chromosomes during mitosis. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2005. 1746(2): p. 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Squires EJ, Sueyoshi T, and Negishi M, Cytoplasmic localization of pregnane X receptor and ligand-dependent nuclear translocation in mouse liver. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(47): p. 49307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deuring JJ, et al. , Pregnane X receptor activation constrains mucosal NF-κB activity in active inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One, 2019. 14(10): p. e0221924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie W. and Tian Y, Xenobiotic receptor meets NF-kappaB, a collision in the small bowel. Cell Metab, 2006. 4(3): p. 177–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.