Abstract

Background:

In a randomized controlled trial, compared with standard care alone in breast cancer, acupuncture as a prophylactic treatment did not show better quality of life or fewer side effects of chemotherapy (NCT01727362 [clinicaltrials.gov]). The aim of the qualitative part of this mixed methods study was to better understand the subjective perspectives of the patients regarding quality of life during chemotherapy and the perceived effects of acupuncture.

Methods:

In a nested retrospective qualitative study, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with 5 responders and 5 non-responders (defined by the outcome of the primary parameter FACT-B) who were randomly selected from both study arms. The interviews were digitally recorded, pseudonymized, transcribed, and then deductively and inductively analyzed according to Qualitative Content Analysis using MAXQDA® software.

Results:

A total of 20 patients were included in the qualitative part of the study. In both groups, most women stated that their quality of life was surprisingly better than what they had expected before starting the chemotherapy. All patients of the acupuncture group experienced the acupuncture treatments as relaxing and beneficial, mentioning a friendly setting, and empathic attitude of the therapist. Most of these patients stated that the acupuncture treatment reduced chemotherapy-induced side effects. The patients reported that acupuncture was supportive for coping with the disease in a salutogenic way. For all patients, finding strategies to cope with life-threatening cancer and the side effects of chemotherapy was essential, for example, keeping a positive attitude toward life, selecting social contacts, and staying active as much as possible.

Conclusions:

Patients in the acupuncture group reported positive effects on psychological and physical well-being after receiving the study intervention. For all patients, having coping strategies for cancer seemed to be more important than reducing side effects. Therefore, further studies should focus more on coping strategies and reducing acute side effects.

Keywords: acupuncture, breast cancer, quality of life, coping, qualitative research, mixed methods, triangulation

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women worldwide. 1 In Germany, it is the most common cancer in women, and compared with other cancer types, BC occurs more frequently in relatively younger women (with a median age of 63 years at diagnosis). 2 Despite less intense treatment plans and fewer side effects compared with BC treatment in the past, current BC treatment including surgery, chemotherapy, immune therapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine treatment is still burdensome for many BC patients. 3 With improved survival rates after BC, for example, with a 5-year relative survival rate of 81% in Germany, quality of life (QoL) before, during and after cancer treatment has become increasingly important to women.2,4,5

In BC patients, there is a high demand and use of complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) to improve QoL.6-10 Studies of acupuncture in addition to cancer treatment, including BC treatment, have shown a reduction in various side effects,11,12 for example, pain,13,14 fatigue, 15 hot flushes, 16 neuropathy, 17 nausea/vomiting, 18 and improvement of QoL.14,16 Therefore, acupuncture has been positively evaluated for cancer patients in general and BC patients in particular and included in several guidelines.19-21

In our pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT) we investigated the effectiveness of additional prophylactic acupuncture treatment during chemotherapy compared to standard treatment alone in breast cancer patients (NCT01727362 [clinicaltrials.gov]). Newly diagnosed BC patients were randomized to acupuncture treatments in addition to standard care over 6 months or to standard care alone (control group). The primary outcome was the disease-specific QoL (FACT-B). Secondary outcomes included cancer-related fatigue (FACIT), side effects of the cancer treatment (FACT-GOG-NTX), general health-related QoL (SF-12), patient satisfaction, and overall treatment effect. A total of 150 women (mean age 51.0 [standard deviation, SD 10.0] years) were included. For the primary endpoint, the total FACT-B score after 6 months, no statistically significant difference was found between groups. The secondary outcomes yielded similar results; however, most patients in the acupuncture group rated the overall effectiveness positively and were satisfied with the acupuncture treatment. 22

The retrospective qualitative study presented in this paper was nested in the RCT mentioned above. The aim of this qualitative study and the integration of this mixed methods approach were to better understand the subjective perspectives of the patients about QoL during chemotherapy in general and the perceived effects of acupuncture and to triangulate the results of the validated questionnaires in a secondary analysis.

Methods

Design

Empirical social research underlines the importance of combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a mixed methods approach to triangulate data. 23 In this paper, we understand triangulation as the integration of the results of quantitative and qualitative approaches. In the retrospective qualitative study, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with participants of the acupuncture und control groups, after completion of the pragmatic trial.

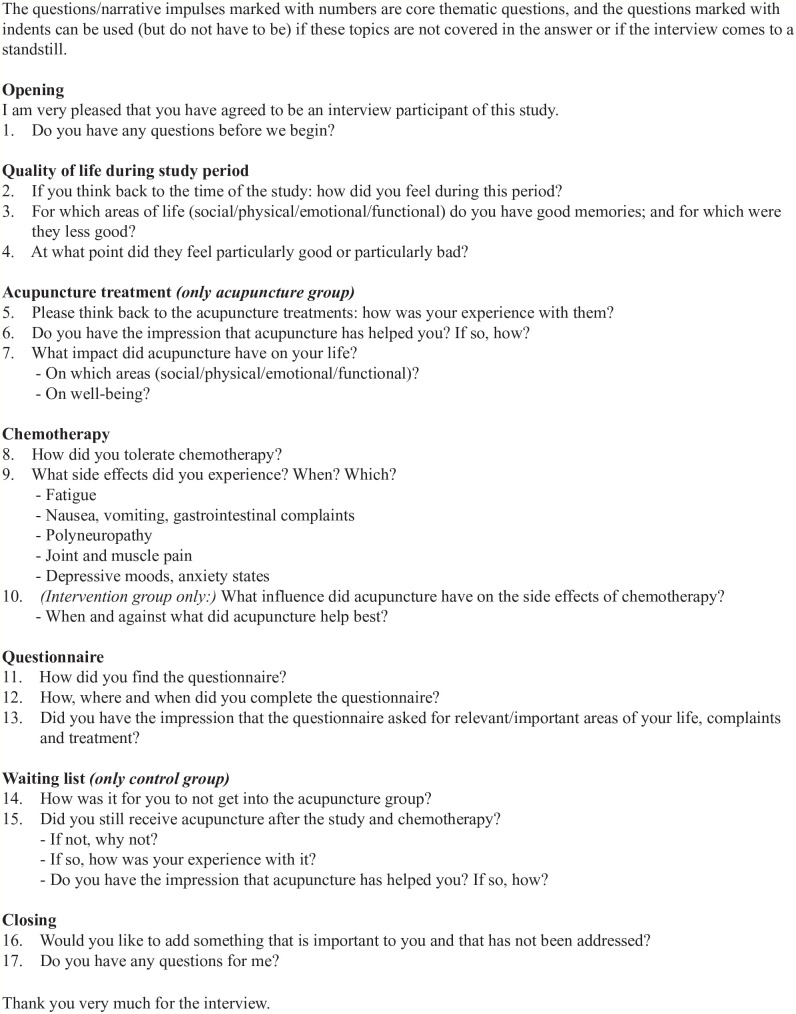

The main topics of the interview guideline were as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Interview guide.

The subjective experience of acupuncture and its perceived effects on QoL and well-being (acupuncture group only)

Personal satisfaction with the acupuncture treatment (acupuncture group only)

Subjectively perceived side effects during chemotherapy, the effects on everyday life and the strategies for handling them (both groups)

Sample

A total of 20 patients were to be included, recruited from a total sample of 150 women in the main study, and semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with them. From each treatment group (acupuncture treatments in addition to standard care and standard care alone) within our pragmatic RCT trial, 5 responders and 5 non-responders were randomly selected according to the results of the RCT as following (Table 1): Responder and non-responder were defined by the results of the primary outcome, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B) total score after 6 months.22,24 A responder was defined as a patient whose FACT-B total score has increased or decreased less than 7 points after 6 months. The randomization for the interviews followed the chemotherapy regime in subsequent order, including patients with completed FACT-B questionnaires at baseline, after 3 months and after 6 months. For the acupuncture group, the assessment of the effectiveness of and satisfaction with acupuncture and having received at least 6 acupuncture treatments was also part of the randomization criteria.

Table 1.

Sample.

| Acupuncture group (AG) | Control group (CG) | |

|---|---|---|

| Responder (R) | 5 AG-R | 5 CG-R |

| Non-responder (NR) | 5 AG-NR | 5 CG-NR |

Data Collection and Analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim and pseudonymized. Written memos of the interviews added further information on the interviewers’ subjective experiences. The interviews were analyzed based on a directed qualitative content analysis using MAXQDA® software. 25 Categories and codes were developed deductively according to the topics of the structured interview guide and the research question and inductively from the data. The analytic process was circular, meaning that new insights from the first data analysis were included in the subsequent data gathering and analyses. The analysis and its results were discussed among the research team and the interdisciplinary qualitative working group at the Charité (Qualitative Research Network, before Institute of Social Medicine, and Institute of Public Health). Thus, the quality and validity of the analysis were improved, and multidisciplinary and intersubjectivity were ensured. The research team included 3 medical doctors, all of them having expertise in various CIM methods and 2 of them also in qualitative research.

Ethical Issues

Written informed consent for the qualitative study part was obtained. The qualitative study part was approved with an amendment by the respective local ethics review board (Hamburg No. PV4002).

Results

Recruitment and Sample

Between August and October 2016, 69 participants were contacted by telephone in total, and 23 could be reached. Two patients declined to participate because of time constraints, and 1 participant was not available at the agreed-upon appointment time. In total, 20 patients (mean age 55 ± 9.6 SD) were included in the qualitative study and interviewed by phone between August and November 2016 (approximately 1.5 years after recruitment for the pragmatic trial was completed).

The Subjective Experience of the Acupuncture Treatment

All patients of the acupuncture group experienced the acupuncture treatment setting as very comfortable and the appointments organized according to their needs. The treatments were scheduled close to the chemotherapy treatment dates so that the patients did not have to travel too much and could often receive an acupuncture treatment directly after chemotherapy. The acupuncture clinic was located in the hospital and was easy to access. The waiting time was reduced as much as possible, and the rooms were described as having a warm, relaxing atmosphere, for example, due to furniture, colors, and music. The therapist was said to take sufficient time during the treatment itself to address all relevant issues at that moment. The empathetic understanding and the competent individual advice of the therapist were said to allow for building trust and feeling safe. All patients reported that they could relax and felt well treated during the treatments. They reported being able to calm down and feeling better than before the treatment.

“After a very short waiting time (. . .) the therapist asked me to enter the treatment room (. . .) and she took time (. . .) to first agree upon (. . .) what needed to be addressed (. . .) there was always some quiet music in the room (. . .) and it was a total relaxation for me.”

(T 6009, AG-R, Acupuncture group responder)

“You came down. You felt in good hands, it was relaxing (. . .) the therapist very, very empathetic. Giving also very good advices (. . .) I was thrilled, I really have to say.”

(P 5042, Acupuncture group non-responder [AG-NR])

All patients reported that they experienced improvement of their acute physical and psychological symptoms after the acupuncture treatment. They reported reductions in headache, limb pain, gastrointestinal problems (eg, nausea, taste, appetite, defecation), and polyneuropathy. Only 1 patient stated that the acupuncture did not reduce any physical complaints. All interviewed patients reported psychological improvement by feeling more relaxed, less stressed, less fearful, psychologically stronger, and sleeping better after acupuncture. This was similar in the responders and non-responders from the quantitative study.

“I liked the acupuncture a lot. It did me good. I had problems with my feet, numbness, also a bit on the arms. In the arms and fingers, it is gone, in the feet unfortunately not. (. . .) I couldn’t sleep very well. And she [the therapist] tried to do something against it (. . .) and indeed I could sleep uninterrupted for 3 to 4 h then.”

(P 5042, AG-NR)

“I have to say, the acupuncture helped me enormously. (. . .) the therapist supported me a lot and as soon as I entered and I showed my tongue [for diagnosis] (. . .) she applied needles accordingly (. . .) she always addressed what was needed and the acute symptoms after the chemotherapy treatment.”

(P 5001, AG-NR)

Quality of Life

In the interviews, the participants were asked directly about their QoL during chemotherapy. In both groups, most women stated that their QoL was surprisingly better than what they had expected before the start of the chemotherapy treatment. However, when asked about the side effects of the chemotherapy, the women reported having many side effects and having been quite affected and impaired by them, which appeared to be a contradiction (see chapter on side effects). Again, these results did not differ between responders and non-responders and the 2 groups.

The social QoL and social functioning was seen as very important by all participants. In this burdensome period, relationships were said to get tested. Often, close relationships, for example, with the partner, family members, and close friends, became intensified. Help and support in general were said to be essential. Nonetheless, most of the patients emphasized trying not to be too much of a burden and wanting to help their partner and especially children deal with their disease. One participant (P, patient 1016, control group responder, CG-R) reported breaking off the relationship with her adult children because of disappointment. She also reported being happy not living in a relationship because she would not have liked to be seen in such a weak state. Superficial contacts were often said to be avoided because the personal gain would be small relative to the effort needed. Additionally, gatherings were avoided because of that but also because of fear of infections. Most women reported that openly dealing with and not hiding the cancer would have been helpful for them and their social surrounding. All participants tried to stay as active as the disease and side effects of the chemotherapy allowed. A few even continued working or studying. They explained that work and studies helped them to structure their lives, stay connected and maintain part of their independence.

“I completely participated in life. I was totally open about my disease. And I almost worked the whole time (. . .) my husband has been a pensioner for 5 years and he then really (. . .) kept the whole house.”

(P 5006, AG-R)

“My daughter was twelve years old. And I thought (. . .) I cannot just die off (. . .) she needs me now and I want to be there for her during this whole [chemotherapy] period (. . .) that was a strong drive for me.”

(P 3019, Control group non-responder [CG-NR])

The physical QoL of the patients depended on the occurrence of chemotherapy side effects and varied in the sample, beside other factors, due to different treatment regimes. Most of them reported that some days up to 1 week after the chemotherapy they felt strongly impaired and then slowly recovered until the next treatment. Continuous impairments were rarely reported. Regarding the whole chemotherapy period, impairments were said to increase.

“Regarding the 6 [chemotherapy] cycles it got worse towards the end (. . .) Still I had the feeling that during the cycles for 1 or 2 days it was extremely bad (. . .) but got again better. But (. . .) “the better” at the end [of the chemotherapy period] was worse than at the beginning.”

(P 3019, CG-NR)

“This extreme weakness! Not being able—even as a normally very energetic person—to carry a bag of potatoes home without taking a break. Or even to open a water bottle.”

(P 1016, CG-R)

The psychological QoL of patients proceeded almost the other way around: after the shocking and frightening diagnosis and beginning of the therapy with all the fearsome expectations, for example, loss of hair, the participants reported to have found a way to deal with it and felt “okay” according to the circumstances. Nevertheless, phases of mood swings with fear and hopelessness were said to occur frequently. In addition, fears often arose during nighttime and in relation to sleep disturbances wherein helpful distractions of everyday life were not available. Continuous severe depression and anxiety states were rarely reported.

“After surpassing the first shock to some extent and you decided for it [the chemotherapy], I pulled myself together relatively quick (. . .) [but] it [the mood] fluctuated (. . .) there were these days where you just cried (. . .) that for sure.”

(P 5006, AG-R)

Perceived Side Effects of Chemotherapy

The type, intensity and perceived impairment of side effects during chemotherapy varied considerably among the participants. The most common side effects were as follows: all women suffered from hair loss, but they handled it very differently, ranging from showing their bald head self-confidently in public to even not entering the bedroom with their partner without wearing their wig. The psychological load of a life-threatening disease resulted in various psychological complaints; fear, sorrow, and rumination were most often mentioned. Sleep disturbance was also mentioned by most of the women and perceived as very straining. Most women reported suffering from fatigue by pointing out weakness, difficulties in concentration, and low endurance. Weakness and tiredness varied most from some days after chemotherapy treatment to weeks to constantly. Difficulty concentrating was mentioned by approximately half of the participants, and it was perceived as very burdensome. Almost all women reported gastrointestinal problems, for example, sore mouth because of mucosal dryness, loss of taste and appetite and nausea. Polyneuropathy, for example, numbness, tingling or pain in the feet, legs, fingers, and arms, was mentioned by approximately half of the women. Almost all women also suffered after the chemotherapy from persistent side effects in one way or the other; fatigue was most often mentioned, followed by polyneuropathy. No differences between acupuncture and control group or responder versus non-responder were obvious in the analysis.

“The physical exhaustion got worse and worse from [chemotherapy] cycle to cycle. I live on the third floor in an apartment building and at 1 point it got really difficult to get up the stairs.”

(P 3020, CG-NR)

“I suffered the whole time from extreme nausea. (. . .) And just in general, I was totally weak. And the worse was that nausea. That you cannot sleep, cannot eat, and cannot drink. Somehow nothing worked.”

(P 5043, AG-NR)

Coping With Cancer and the Side Effects of Chemotherapy

Reports of coping with BC were reported by all interviewed patients spontaneously. Coping with the tumor diagnoses and negative expectancy of the therapy seemed to have had a strong influence on the perception of the chemotherapy itself for all participants. Having a cancer diagnosis and needing chemotherapy was seen as one of the worst things that could happen to you. In reaction to that fearsome threat, all women of the control group and most women (7 out of 10) of the acupuncture group expressed the desire to keep a positive attitude toward life and their healing process in the sense of “I’m gonna make it.” Acceptance of the disease and taking up the challenge of wanting to survive were seen as essential for holding on. Social support (privately and professionally), staying active (housekeeping, working, studying), physical exercise and spending time outdoors in fresh air were most often reported to be important and helpful strategies for most women of both groups.

“What am I supposed to do? I can’t bury my head in the sand now. I must face the thing [breast cancer], I must go through there. And make the best of it and try. Then, we know if it works or not.”

(P2025, CG-NR)

“I always had a positive attitude and always told myself: you gonna show them all.”

(P 5017, AG-R)

All patients from both groups emphasized the support they reported to have received in the clinic. They felt they were treated empathetically, and the breast nurses were especially noted as persons to contact whenever needed. That the clinic offered complementary acupuncture treatment in addition to conventional medicine was appreciated by both groups. All patients receiving acupuncture perceived the treatments as an important support and opposite pole to the life-threatening disease and burdensome chemotherapy. This opposite pole was said to be directly experienced as a friendly setting, empathetic, and competent support by the acupuncture therapist and the relaxation and enhancement of well-being during the treatment sessions.

“All in all, this whole package (. . .) with this attached acupuncture (. . .) from the oncology and from the acupuncture therapist (. . .) gave such positive impulses (. . .) supporting me.”

(P 6009, AG-R)

“So, I can really only pronounce an even A for that [referred to school grades]. (. . .) the breast nurse (. . .) she was there straight away after the operation and explained me everything (. . .) how to get a disabled person`s pass and providing addresses for wig manufactures (. . .) “if anything is wrong, you can always call me (. . .) I am always available.” And she always was.”

(P 1015, CG-NR)

Evaluation of Questionnaires

In the interview, patients were asked specifically about the questionnaires used in the quantitative study. Most of the participants did not remember the details of the questionnaires. For them, the questionnaires were something “neutral, not very important.” Some participants could not even remember that they had completed questionnaires. Frequently, it was mentioned that rating averages, for example, for the last 7 days, was very abstract and did not correlate with the experiences they had because it would not show peaks of suffering nor periods of feeling well. Filling in the study questionnaire regarding their actual status was described as being extremely dependent on whether chemotherapy was received that day. Thus, filling in the questionnaire would result in very different statements when completing it, for example, 1 day before or 1 day after chemotherapy treatment: most likely, they would report a relatively good status before chemotherapy and a very bad status 1 day after. Only a few participants perceived the questionnaire as easy to understand and appropriate.

Altogether, the study was seen as very meaningful in finding ways to help women suffering from BC. With their participation, they wanted to support that. To have the chance to receive acupuncture was perceived as a “gain” and “gift,” and many patients felt grateful for it. The participants in the control group were sometimes disappointed that they did not receive acupuncture during chemotherapy, but they still wanted to support research about acupuncture.

“It is always quite difficult, to chop up complex interrelationships. (. . .) there was so much about all these symptoms and I could not really tell about it and also not relate that to acupuncture. I found it [the questionnaires] difficult to fill in.”

(P 6003, AG-R)

“Partly (. . .) the questions weren’t really applicable to me regarding the possible answers, (. . .) [but still] generally the questions were all right.”

(P 5045, CG-R)

Triangulation of Quantitative and Qualitative Results

The linking of the results from the interviews with the quantitative results did not reveal any different patterns in the responders and non-responders of both groups. With the following 4 quotations we want to illustrate that the results of the questionnaires do not match the statements in the interviews.

A responder from the acupuncture group said the following:

“Of course I always was very weak.”

(P 5006, AG-R)

A responder from the control group said the following:

“I would never do this [the chemotherapy] again, (. . .) I am still relatively young (. . .) and I wanted to be vital and strong now (. . .) but that is over, no need to think about it anymore.”

(P 1016, CG-R)

A non-responder from the acupuncture group said the following:

“In comparison to other patients I was doing very well. Okay, of course you had these little ailments, but it was all bearable. Frankly, influenza must be worse, I believe.”

(P 5029, AG-NR)

A non-responder from the control group said the following:

“As I said, it wasn’t as bad physically as I feared.”

(P 1015, CG-NR)

Discussion

In both groups, most women stated that their QoL was surprisingly better during chemotherapy than what they had expected beforehand. All patients of the acupuncture group experienced the acupuncture treatments as relaxing and beneficial. Most of these patients stated that the acupuncture treatment reduced the side effect symptoms triggered by chemotherapy. Moreover, acupuncture was said to support them in coping with the disease in a salutogenic way. Finding coping strategies to deal with the cancer and the side effects of the chemotherapy was primarily important and essential during the study period for all, for example, keeping a positive attitude toward life, choosing social contacts, and staying active as much as possible. The linking of the results from the interviews with the quantitative results did not reveal any different patterns in the responders and non-responders of both groups.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Triangulation of quantitative and qualitative data is seen as an important step to reflect research questions, methods, and their results. 23 The mixed methods approach in this study allowed a profound and broad analysis in interpreting the results of the quantitative study with more information about the patients’ thoughts and in obtaining better understanding of the subjective perspective of the patients.

Conducting telephone interviews was a practical and comfortable way to have a personal talk in an adequate setting (at home for the participants, in a quiet office for the interviewer) without having to travel far. According to the experience of the interviewer and frequent statements of the patients the fact that the interviewer and patient did not meet face to face did not seem to create distance. Nevertheless, telephone interviews are restricted in their information to the voice alone. Nonverbal information, for example, gestures, facial expressions, and appearance, are not perceived. Face-to-face contact might support a more personal and open contact and therefore are in general preferential in qualitative interviews.

Another limitation was the possible recall bias of the retrospective approach of the qualitative study, which was nested in the study after the pragmatic trail was completed. Therefore, the qualitative data cannot be compared directly with the quantitative data.

Effects of Acupuncture on Acute Complaints and QoL

The findings in our qualitative study correlate with many quantitative studies showing a positive effect of acupuncture on reducing various side effects of chemotherapy, especially regarding pain, gastrointestinal problems, and vasomotor symptoms, for example, polyneuropathy.26-28 Moreover, our findings show that the acupuncture treatments had various psychological effects in addition to the somatic effects, in particular supporting relaxation and sleep, feeling generally stronger, and reducing stress and fear. The reduction of side effects suggests a better QoL; nevertheless, a better QoL in the acupuncture group than in the control group was not observed in either the qualitative or the quantitative study, with most women in both groups reporting a better QoL than expected beforehand. 22

Importance of Coping With BC

While fewer side effects obviously allow for a better QoL, coping strategies, and resource orientation also have a high impact on QoL.4,29 The findings of our qualitative study underline the importance of finding coping strategies to deal with the cancer and the side effects of the chemotherapy. The concept of coping goes back to Lazarus and Folkman, who defined it as a dynamic process to deal with the stress and demands associated with diseases including cognitive and behavioral efforts. According to Folkman and Lazarus, 30 effective coping strategies include an optimistic approach, a self-confident approach, and seeking social support. Ineffective coping methods include hopelessness and submissive approaches. Resources, for example, optimism, positive emotions, self-efficacy, sense of coherence, spiritual orientation, and social support, seem to be protective factors in relation to QoL and cancer.29,31,32 Among women with BC, several studies have shown that positive and adaptive styles of coping strategies, such as planning, problem solving, positive reframing, and acceptance, are linked with better QoL. Social support (professional or private) seems to play an especially important role.4,29,33

The most important coping strategies reported in our study by the women in both groups were keeping a positive attitude toward life, choosing social contacts, and staying active as much as possible. With a life-threatening disease, the wish to survive seems most important, and side effects seem more likely to be tolerated. That could be one explanation for the relatively good QoL scores in both groups in our quantitative study findings, and it correlates with the extensive research body on coping with cancer and QoL. In our qualitative findings, we could identify various resources and positive and adaptive coping strategies4,29,31-33 such as positive emotions and reframing, acceptance, self-efficacy (including staying active and problem solving), and social support.

Acupuncture is apparently experienced as an important antithesis to the life-threatening disease and stressful, aggressive chemotherapy. In our study, the treatments were experienced as relaxing and beneficial, starting with the friendly setting and empathetic attitude of the therapist. On the one hand, the women reported to have felt in good hands and well taken care of. On the other hand, due to the useful tips of the acupuncturist, they were also supported in self-efficacy and actively dealing with their problems. Thus, acupuncture and the interaction between the patient and acupuncturist seemed to support positive coping in the sense of salutogenesis. The concept of salutogenesis was first described by Antonovsky 34 and can be understood as the orientation toward health, and it relates directly to coping. 35

Social support from professionals has an important impact on QoL of BC patients, too. 29 In our study, the women in the acupuncture group received much professional social support from their acupuncturist. In addition, the women of both groups were very positive about the social professional support they received in the clinic. Even just the offer of this study with a complementary acupuncture treatment was appreciated by the control group. That could also partly explain the relatively good QoL in both groups in the quantitative data. 22

Triangulation

One important goal in qualitative studies is bringing new topics to light. 36 In our qualitative study, the topic of coping strategies emerged in the interviews inductively, playing an important role for the patients. This concept expands the results of our quantitative study because coping strategies were not addressed in the questionnaires.

Compared to the quantitative study, in the retrospective approach of the qualitative study, partly different foci were laid purposely: To better understand the results of the quantitative study, the patients were asked directly about their subjective experience of acupuncture and its perceived effects on QoL in the interviews. In contrast, the questionnaire did not address the acute effects of acupuncture. Furthermore, to be able to compare quantitative and qualitative results better, mixed methods approaches should be included from the beginning of designing a study.

In further quantitative research about acupuncture treatment during chemotherapy in BC patients, coping strategies and the acute effects of acupuncture should be taken more into account. Furthermore, the data collection of filling out the questionnaires should be related much more with the primary anticancer treatment, especially to the chemotherapy, because of the huge variations in the QoL immediately before or after chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Overall, most women stated that their QoL was surprisingly better than what they had expected before starting chemotherapy. The patients in the acupuncture group reported positive effects on acute physical complaints and psychological well-being after receiving the study intervention. For both patient groups, having coping strategies for life-threatening cancer seemed to be more important than reducing side effects. That could be one explanation for the relatively good QoL in both groups. The questionnaires of the quantitative study unfortunately did not address the acute treatment effects of acupuncture or coping strategies, and in further studies, they should also relate more to the anticancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating women for their trust and participation. We thank the Dorit und Alexander Otto-Stiftung for funding. We thank Stephanie Roll and Sylvia Binting for their support and valuable comments in the discussion of the results.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Qualitative study concept and design: BS, BB, and CW. Data Management: BS. Qualitative Analysis: BS. Interpretation of data: BS, BB, and CW. Obtained funding: BB and CW. Drafting the manuscript: BS, BK, MC, BB, and CW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available to honor the individual privacy of the participants but are partially available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by the Dorit und Alexander Otto-Stiftung in Hamburg, Germany. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the qualitative study or in the collection and management, analysis, and interpretation of the data or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Barbara Stöckigt  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2438-876X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2438-876X

References

- 1. Ghoncheh M, Pournamdar Z, Salehiniya H. Incidence and mortality and epidemiology of breast cancer in the world. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:43-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Katalinic A, Pritzkuleit R, Waldmann A. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality in Germany. Breast Care. 2009;4:75-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harbeck N, Gnant M. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017;389:1134-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paek MS, Ip EH, Levine B, Avis NE. Longitudinal reciprocal relationships between quality of life and coping strategies among women with breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:775-783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boon HS, Olatunde F, Zick SM. Trends in complementary/alternative medicine use by breast cancer survivors: comparing survey data from 1998 and 2005. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11:187-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang E, Yang EJ, Kim SM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and assessment of quality of life in Korean breast cancer patients: a descriptive study. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:461-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molassiotis A, Fernández-Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:655-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oskay-Ozcelik G, Lehmacher W, Könsgen D, et al. Breast cancer patients’ expectations in respect of the physician-patient relationship and treatment management results of a survey of 617 patients. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:479-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zia FZ, Olaku O, Bao T, et al. The National Cancer Institute’s conference on acupuncture for symptom management in oncology: state of the science, evidence, and research gaps. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 2017;2017:68-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garcia MK, McQuade J, Lee R, Haddad R, Spano M, Cohen L. Acupuncture for symptom management in cancer care: an update. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16:418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crew KD, Capodice JL, Greenlee H, et al. Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1154-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu C, Zhang H, Wu W, et al. Acupuncture for pain management in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1720239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, et al. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4470-4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lesi G, Razzini G, Musti MA, et al. Acupuncture As an integrative approach for the treatment of hot flashes in women with breast cancer: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial (AcCliMaT). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1795-1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bao T, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, et al. A pilot study of acupuncture in treating bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with multiple myeloma. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13:396-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen J, Wenger N, Glaspy J, et al. Electroacupuncture for control of myeloablative chemotherapy-induced emesis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:2755-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Regan D, Filshie J. Acupuncture and cancer. Auton Neurosci. 2010;157:96-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:194-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Witt CM, Cardoso MJ. Complementary and integrative medicine for breast cancer patients: evidence based practical recommendations. Breast. 2016;28:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brinkhaus B, Kirschbaum B, Stöckigt B, et al. Prophylactic acupuncture treatment during chemotherapy with breast cancer: a randomized pragmatic trial with a retrospective nested qualitative study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178:617-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelle U. Sociological explanations between micro and macro and the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2001;2:22. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dibble SL, Chapman J, Mack KA, Shih AS. Acupressure for nausea: results of a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27:41-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mao JJ, Bruner DW, Stricker C, et al. Feasibility trial of electroacupuncture for aromatase inhibitor—related arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8:123-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walker EM, Rodriguez AI, Kohn B, et al. Acupuncture versus venlafaxine for the management of vasomotor symptoms in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:634-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Finck C, Barradas S, Zenger M, Hinz A. Quality of life in breast cancer patients: associations with optimism and social support. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2018;18:27-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48:150-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Popa-Velea O, Diaconescu L, Jidveian Popescu M, Truţescu C. Resilience and active coping style: effects on the self-reported quality of life in cancer patients. Int J Psychiatr Med. 2017;52:124-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chirico A, Lucidi F, Merluzzi T, et al. A meta-analytic review of the relationship of cancer coping self-efficacy with distress and quality of life. Oncotarget. 2017;8:36800-36811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ozdemir D, Tas Arslan F. An investigation of the relationship between social support and coping with stress in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2214-2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Antonovsky A. Health, Stress, Anc Coping. Jossey-Bass; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. 1st ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Flick U. Qualitative Forschung: ein Handbuch/Uwe Flick . . . (Hg.) Orig.-Ausg. 10th Aufl. Rowohlt; 2013. [Google Scholar]