Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐Cov‐2) resulting in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is documented to have a negative psychosocial impact on patients. Home dialysis patients may be at risk of additional isolating factors affecting their mental health. The aim of this study is to describe levels of anxiety and quality of life during the COVID‐19 pandemic among home dialysis patients. This is a single‐centre survey of home dialysis patients in Toronto, Ontario. Surveys were sent to 98 home haemodialysis and 43 peritoneal dialysis patients. Validated instruments (Haemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Item [GAD7] Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ‐9], Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale, Family APGAR Questionnaire and The Self Perceived Burden Scale) assessing well‐being were used. Forty of the 141 patients surveyed, participated in September 2020. The mean age was 53.1 ± 12.1 years, with 60% male, and 85% home haemodialysis, 80% of patients rated their satisfaction with dialysis at 8/10 or greater, 82% of respondents reported either “not at all” or “for several days” indicating frequency of anxiety and depressive symptoms, 79% said their illness minimally or moderately impacted their life, 76% of respondents were almost always satisfied with interactions with family members, 91% were never or sometimes worried about caregiver burden. Among our respondents, there was no indication of a negative psychosocial impact from the pandemic, despite the increased social isolation. Our data further supports the use of home dialysis as the optimal form of dialysis.

Keywords: dialysis, home haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis

SUMMARY AT A GLANCE

This survey of home haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis patients found no indication of a negative psychosocial impact from the COVID‐19 pandemic, despite the increased social isolation. Thus, patients who are able to practise dialysis at home and hence minimize infectious contacts do not experience high levels of psychosocial distress, adding to the paradigm of home dialysis as the optimal form of dialysis.

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, in response to the emergence and rapid spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐Cov‐2) resulting in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). The WHO warned of a natural psychological response involving anxiety and distress from these rapidly changing conditions. 1

Experience from previous pandemics, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐Cov‐1) pandemic from 2003, demonstrated that global pandemics have a significant effect on mental well‐being including fear of contraction and spreading infection to family members, loneliness, anxiety, depression and suicide. 2 Reasons include national lockdowns to contain virus spread resulting in isolation and family separation, panic and hysteria propagated by the vast spread of often‐inaccurate information via social media, lack of basic needs and financial losses and the fear and vulnerability associated with the uncertainty of disease progression. 2 , 3

This fear of disease progression may be increased in dialysis patients given their baseline medical comorbidities. Chronic dialysis patients had an increased risk of severe COVID‐19 infection‐related complications, intubation and mortality, particularly in patients aged 60–79 years old. 4

Therefore, we hypothesize that end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients performing home dialysis may have a high level of anxiety and psychological distress secondary to the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health.

2. METHODS

A single‐centre survey of home dialysis patients in Toronto, Ontario, including 98 home haemodialysis patients and 43 peritoneal dialysis patients, was performed. Approval was received from the Research Ethics Board from the University Health Network (20‐5439). Patients were emailed a list of six validated instruments for assessing wellbeing, including: Haemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Item (GAD7) Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9), Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale, Family APGAR Questionnaire and The Self Perceived Burden Scale. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Surveys were sent twice (approximately 4 weeks apart) with reminders to complete the questionnaires. Free text was also permitted.

Anonymized demographic data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University Health Network. 11 Data included age, sex, marital status, length of time on dialysis and renal replacement therapy modality. For each validated instrument, initial summary analysis included the percentage of patients who rated a neutral or optimal set of answers, based on that scale. Additionally, data was presented in cumulative bar graphs for each question of each survey, and data was approximately grouped and divided as the less optimal, neutral, and more optimal choice, labelled red, yellow and green, respectively. Each set of questions from the same survey are grouped in a single figure below. Qualitative analysis of free text collected via open‐ended questions was performed.

3. RESULTS

The survey was sent to 141 participants in September 2020, of which 40 returned a completed survey. The mean age was 53.1 ± 12.1 years, and the mean length of time on dialysis was 165.3 ± 135.8 months, 60% of participants were male, 85% used haemodialysis, and 63% were currently married.

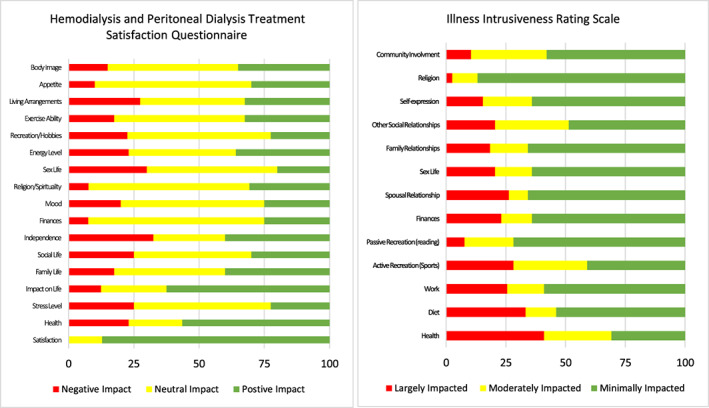

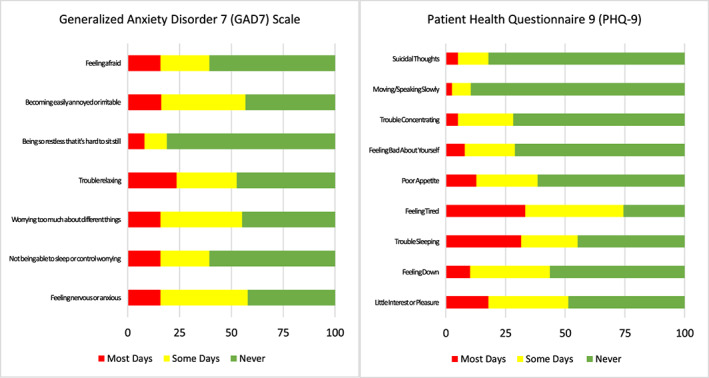

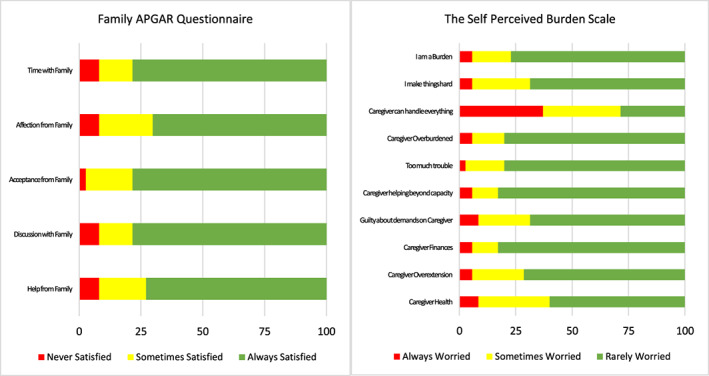

In the first survey, Haemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, where participants rated their satisfaction with various aspects of their life, 80% of respondents rated satisfaction as 8/10 or greater. In each of the 17 questions, over 70% of participants responded that the impact of dialysis on individual variables such as appetite, exercise ability, mood and stress life was either positive or neutral (Figure 1). On the Illness Intrusiveness Rating Scale, participants were asked to quantify the impact of ESRD and home dialysis on various aspects of their life. On average, 79% of patients said their illness minimally or moderately impacted their life, including the variables community involvement, religion, self‐expression, relationships, sex life, finances, work and recreation (Figure 1). Both diet and health had a slightly higher impact rating. In assessing for generalized anxiety and depression, 82% of participants noted symptoms either “not at all” or “several days”. Using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 Item (GAD7) and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ‐9) scales, where symptoms of anxiety and depression were broken down individually, most symptoms were experienced “some days” or “never” in more than 80% of respondents (Figure 2). “Trouble sleeping” and “tired” scored in red, in approximately one third of patients. Issues with sleeping and relaxing were slightly lower. The Family APGAR Questionnaire, assessing relationships with family members, showed participants “always satisfied” 76% of the time, and “always or sometimes satisfied” over 91% of the time (Figure 3). Finally, over 91% stated they were “rarely or sometimes worried” about their perceived burden to their caregivers on the Self Perceived Burden Scale (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Results of the surveys on the impact of renal failure and dialysis therapy on patients

FIGURE 2.

Results of the surveys on depression and anxiety symptoms of patients

FIGURE 3.

Results of the surveys of the relationships of patients with their family

Qualitative analysis of the free text collected in the Haemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire revealed common themes contributing to this high satisfaction. These included “a feeling of safety from COVID‐19 with no travel to in‐centre appointments”, “a flexible schedule that maintained autonomy and independence while also allowing patients to continue working during a period of potential economic instability”, “the support of family, children and a familiar environment”, “continuing to have a liberated diet and the opportunity to exercise” and “the opportunity to maintain social activities and lifestyle practices.”

4. DISCUSSION

Most home dialysis patients surveyed feel positively or neutral about their satisfaction on dialysis during the COVID‐19 pandemic. A minority of patients frequently experienced symptoms of generalized anxiety or depression or felt their illness was largely impacting various aspects of their life. Approximately 90% were satisfied with their family interactions and were not often worried about their caregiver burden. For those surveyed, this indicates wellbeing and quality of life remain high during the pandemic. Explanations identified include the comfort of minimized COVID‐19 infection exposure by avoiding travel, wellbeing maintenance through household family support, lifestyle activities and exercise, and having control and autonomy over management of their dialysis.

These results are unexpected given the increased risk of mental health disorders for baseline dialysis patients. Hospitalizations from depression, anxiety and substance abuse are 1.5–3× higher in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to other chronic diseases. 12 Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder in ESRD patients where 26.5% of patients reported depressive symptoms by questionnaire, and 21.5% had clinically significant symptoms when assessed by clinical interviews. 13

This also contrasts with a recent publication studying similar trends in in‐centre haemodialysis where patients reported a high amount of worry relating to the effect of the pandemic on their mental wellbeing. Perceived stress and feelings of being overwhelmed were both high, with the reasons cited related to travelling to dialysis centres where public transportation and ride sharing is often used, the inability to social distance in dialysis units often being cared for by multiple dialysis staff, and the stress of having to wear masks and have family restrictions. 14 Many of these risks are mitigated in the home dialysis population, possibly explaining the differences in results. A Chinese study comparing Impact of Event Scale (IES) scores between in‐centre haemodialysis patients and at‐home peritoneal dialysis patients, showed a significantly higher IES score in the haemodialysis population, equating to a post‐traumatic stress syndrome classification for 22.4% of in‐centre haemodialysis patients, and 13.4% of peritoneal dialysis patients. 15 This is consistent with the contrasting results of our home dialysis population compared to the in‐centre haemodialysis survey.

There are some limitations of this survey. A selection bias exists in home dialysis patients who sometimes have a higher capacity to cope and trouble shoot, permitting them to start and maintain home dialysis independently. Therefore, these patients' coping mechanisms likely extend beyond the management of their physical disease, to include mental health preservation. Second, the sample of home dialysis patients who completed the survey are likely coping well at this time, as opposed to those who did not complete the survey, who may be coping less well. Additionally, there was a low response rate which may limit the precision of the observations. Due to sample size limitations, a comparison between home haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis could not be performed. Finally, this survey was from one point in time. Unfortunately, due to the unexpected nature of the COVID‐19 pandemic, baseline wellbeing data does not exist for comparison purposes. We can only compare this data to other cross‐sectional samples, performed on different populations at different times.

There were two responses deemed adverse events. The first was from a home haemodialysis patient who, because of issues with his arteriovenous fistula, reported struggling daily and did not have the energy to complete the survey at the time. The second was from a patient who declined to participate as he felt effectively isolated prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic and therefore was disinterested. Both patients were offered medical care and mental health counselling assistance by the research team.

In conclusion, there does not appear to be excessive stress from the presence of the COVID‐19 pandemic on patients receiving dialysis at home. Even though both the pandemic and being on dialysis carry significant stressors, there does not appear to be an additive burden. For this group, home therapy is a feasible technique, supporting it as the optimal form of dialysis therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Davis MJ, Alqarni KA, McGrath‐Chong ME, Bargman JM, Chan CT. Anxiety and psychosocial impact during coronavirus disease 2019 in home dialysis patients. Nephrology. 2022;27(2):190‐194. doi: 10.1111/nep.13978

REFERENCES

- 1. Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Pandemic. http://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 2020.

- 2. Robertson E, Hershenfield K, Grace SL, Stewart DE. The psychosocial effects of being quarantined following exposure to SARS: a qualitative study of Toronto health care workers. Can J Psychiatr. 2004;49:403‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder‐Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID‐19 outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamada T, Mikami T, Chopra N, Miyashita H, Chernyavsky S, Miyashita S. Patients with chronic kidney disease have a poorer prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): an experience in New York City. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52:1405‐1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Juergensen E, Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Juergensen PH, Bekui A, Finkelstein FO. Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: patients' assessment of their satisfaction with therapy and the impact of the therapy on their lives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1191‐1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD‐7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092‐1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606‐613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Devins GM, Binik YM, Hutchinson TA, Hollomby DJ, Barré PE, Guttmann RD. The emotional impact of end‐stage renal disease: importance of patients' perceptions of intrusiveness and control. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1984;13:327‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. 1978;6:1231‐1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cousineau N, McDowell I, Hotz S, Hébert P. Measuring chronic patients' feelings of being a burden to their caregivers: development and preliminary validation of a scale. Med Care. 2003;41:110‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kimmel PL. Psychosocial factors in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1599‐1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmer S, Vecchio M, Craig JC, et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Course of depression and anxiety diagnosis in patients treated with hemodialysis: a 16‐month follow‐up. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1752‐1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xia X, Wu X, Zhou X, Zang Z, Pu L, Li Z. Comparison of psychological distress and demand induced by COVID‐19 during the lockdown period in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: a cross‐section study in a tertiary hospital. Blood Purif. 2020;28:1‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]