Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has caused fear all around the world. With people avoiding hospitals, there has been a significant decrease in outpatient clinics. In this study, we aimed to compare and explore the first peak of the pandemic period by studying its effects on patient applications, new diagnoses and treatment approaches in a non‐infected hospital.

Methods

We collected data from the first peak of the pandemic period in Turkey, from the pandemic declaration (11 March 2020) to social normalization (1 June 2020), and compared it with the data from a pre‐pandemic period with a similar length of time. We analyzed the data of breast cancer patients from application to surgery.

Results

The data of 34 577 patients were analyzed for this study. The number of patients who applied to outpatient clinics decreased significantly during the pandemic period. After excluding control patients and benign disorders, a figure was reached for the number of patients who had a new diagnosis of breast cancer (146 vs. 250), were referred to neoadjuvant treatment (18 vs. 34), and were treated with surgery (121 vs. 229). All numbers decreased during the pandemic period, except for surgeries after neoadjuvant treatment (21 vs. 25). Surgical treatment approaches also changed. However, the rate of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients treated with surgery was similar in both periods. None of these patients were diagnosed with COVID‐19 or died during the pandemic.

Conclusion

This study shows that non‐infected hospitals can be useful in avoiding delays in the surgical treatment of cancer patients.

What’s known

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused fear worldwide. Curfews, social distancing and hospital avoidance have reduced routine controls and screening programs. Some new algorithms were published for breast cancer treatment throughout the pandemic, which were suggested postponing surgical treatment for low‐risk patients because of the increased infection risk in hospitals. However, we have seen postponing cannot be a solution.

What’s new

The effects of the Sars‐CoV‐2 pandemic and its spread continue to be seen. Another way has to be found to treat cancer patients but postpone surgical treatment or risk their lives in hospitals. Non‐infected hospitals may be the answer to this issue.

1. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has caused fear all around the world. Curfews, social distancing and hospital avoidance have reduced routine controls and screening programs.

Over the course of the pandemic, some new algorithms were published for breast cancer treatment. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Most of the algorithms suggested postponing surgical treatment for low‐risk patients because of the increased infection risk in hospitals. Also, it was suggested that screening and routine diagnostic imaging be deferred to a later date.

Surgery is an essential part of the treatment for breast cancer patients. Postponing surgical treatment may cause a progression in the cancer stage, or a patient may lose her chance to have breast‐conserving surgery.

This study aimed to compare and explore the pandemic period by studying its effect on patient applications, new diagnoses and treatment approaches for breast cancer patients in our hospital.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

This single‐centre, retrospective, observational cohort study includes patients admitted and treated in the breast unit of the University of Health Sciences Ankara Oncology Hospital between 21 December 2019 and, 1 June 2020. Data were collected from the hospital database.

2.2. Patient selection & method

The WHO declared the COVID‐19 pandemic on 11 March 2020. 5 According to the Turkish Ministry of Health statistics, a rapid increase of infected patients was seen in the first month of the pandemic; however, the situation stabilized in June 2020. 6 Between 11 March and 1 June 2020, most of the population was advised to stay at home. Since 1 June, our country has seen the onset of social normalization.

In Turkey, hospitals were classified into three groups: pandemic hospitals, non‐infected hospitals that do not admit patients with proven COVID‐19, and combined hospitals admitting COVID‐19 patients and others. Our hospital was in the second group. We continued both emergency surgeries and malignancy procedures but did not admit patients with either suspected or proven COVID‐19.

In this study, patients were explored in two groups. The first group was from the pandemic period, ie, 11 March 2020, to 1 June 2020. The second group was from a similar period (82 days) before the pandemic.

For these two groups, patients who applied to our outpatient clinics were analyzed. After excluding other medical conditions, 11 479 patients were analyzed to explore diagnoses and treatment approaches for breast disorders. Control patients and benign breast disorders were excluded to analyze breast cancer patients particularly.

2.3. Working in a non‐infected hospital during the pandemic

An outpatient clinic for patients suspected of being infected with Sars‐CoV‐2 was established in the hospital garden. In this way, neither suspected nor infected patients entered the hospital. The emergency room entrance was also separate.

Patients were given a temperature check at all of the hospital entrances and those with fever were referred to the separate outpatient clinic mentioned above.

There was a separate inpatient clinic and intensive care unit for isolating suspected patients who already had surgery.

All patients were given a PCR test for Sars‐CoV‐2 before hospitalization during pre‐operative preparations, to hospitalize only negative patients. PCR tests were repeated to avoid new contaminations and false negativity in delays of more than two days before surgery.

We made diagnoses and perform staging, preoperative preparations and treatment decisions permanently in outpatient clinics. We did not hospitalize patients before their operations without necessary situations.

We also shorten hospitalization time and discharged patients immediately after surgery unless any complications occurred.

Before discharging patients, we educated them about postoperative wound care, possible risks or complications, and protection from Sars‐CoV‐2 infection. Postoperative follow‐ups were made by phone calls and applications to outpatient clinics after discharge.

We did not operate on patients who had benign diagnoses without suspected malignancy or non‐emergency cases during the pandemic period.

The number of surgeries was limited for each operating room to reduce personnel exposure and limit the risk of spreading infection.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The distribution of the variables analyzed using visual (histogram and probability graphs) and analytical methods (Kolmogorov‐Smirnov/Shapiro‐Wilk tests). Definitive analyzes were performed as frequency tables for categorical variables. Median and range were calculated for the continuous variable (age). The numbers for admissions, breast cancer diagnoses, operation types and pathological results of each group were compared. Differences between the groups in terms of these frequencies were compared using the Pearson chi‐Square test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All analyses were performed with SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 25.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. RESULTS

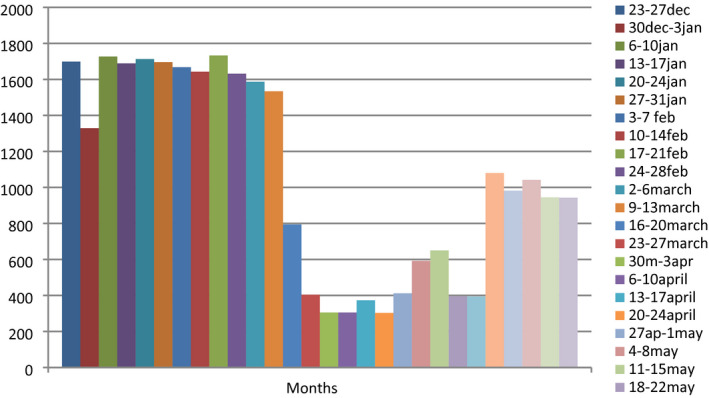

We explored a total of 34 577 patients who applied to outpatient clinics in our hospital. With the declaration of the pandemic, the number of applications to our outpatient clinics noticeably decreased (Figure 1). After excluding other medical conditions, there were 11 479 patients with breast disorders. There were 2420 patients who had breast cancer in our outpatient clinics (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Outpatient clinics approval by weeks

TABLE 1.

Differences between the number of patients who applied to outpatient clinics

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| During COVID‐19 pandemic | Before COVID‐19 pandemic | |

| (11 March 2020‐1 June 2020) | (21 December 2019‐10 March 2020) | |

| Application to outpatient clinics | 5872 | 28 705 |

| Number of patients with breast disorders | 2793 | 8686 |

| Number of breast cancer patients | 760 (27.3%) | 1660 (19.1%) |

| Breast cancer diagnosis | 146 (5.2%) | 250 (2.8%) |

| Number of referrals for neoadjuvant treatment | 18 (12.3%) | 34 (13.6) |

Two hundred and fifty patients had a breast cancer diagnosis before the pandemic (Group 2) and 146 during the pandemic period (Group 1). New breast cancer diagnoses comprised 5.2% of all applications to the breast unit in the first group and 2.8% in the second group. There were more patients in the second group with benign disorders and follow‐ups.

Before the pandemic, 143 of 250 patients (57.2%) underwent breast cancer surgery, and 34 (13.6%) of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients were referred to neoadjuvant treatment. Eighty‐nine of 146 patients (60.9%) had surgery for breast cancer during the pandemic period, and 18 (12.3%) patients were referred for neoadjuvant treatment. The increase in the number of referrals for neoadjuvant treatment during the pandemic period was not statistically significant (P = .71).

Three hundred and fifty surgically treated patients were analysed in particular. The median age was 51 (range: 20‐82), and all patients were women.

The mastectomy rate slightly increased during the pandemic, with 61 patients (68.5%) in the first group and 92 (64.3%) in the second group, but there was not a significant difference (P = .51). Similarly, the increase in the positivity rate of sentinel lymph node biopsies in the pandemic period was not statistically noticeable (P = .76). There were 19 patients (30.1%) who had metastatic sentinel lymph nodes in group 1 and 31 patients (28.4%) in group 2 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Treatment types and operations applied to patients who treated with surgery

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| (During COVID‐19 pandemic) | (Before COVID‐19 pandemic) | |

| Surgery | 121 (86.4%) | 229 (87.7%) |

| Benign procedures | 12 (9.9%) | 25 (10.9%) |

| Wire guided biopsies | 20 (16.5%) | 61 (26.6%) |

| Malignant procedures | 89 (73.6%) | 143 (62.4%) |

| Surgery after neoadjuvant treatment | 21 (23.6%) | 25 (17.5%) |

| Breast conserving surgery | 28 (31.5%) | 51 (35.7%) |

| Mastectomy | 61 (68.5%) | 92 (64.3%) |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy (slnb) | 62 (69.2%) | 109 (76.2%) |

| Slnb positive | 19 (30.6%) | 31 (28.4%) |

| Slnb negative | 43 (69.4%) | 78 (71.6%) |

| Axillary dissection | 45 (50.6%) | 66 (46.2%) |

Patients had larger tumours and more lymph node metastases in the pandemic period (Table 3). There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups for tumour size. When we compared two groups for t0 and t1 tumours with bigger ones (t2‐3‐4), we found more big tumours in the first group (P = .01). On the contrary, there was no significant difference in lymph node positivity rates (P = .22). But we found a statistically significant difference between the two groups for stages. More early‐stage breast cancer (stages 0‐1‐2a) patients in the second group (P = .02). Further, there were more DCIS (ductal carcinoma in‐situ) patients but no significant changes in the pathological type of tumours (P = .30).

TABLE 3.

Pathological tumor sizes and lymph node status of patients who treated surgically

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| (Pandemic period) | (Before pandemic) | |

| Tumour size | ||

| In situ | 7 (7.9%) | 7 (4.9%) |

| T1 | 14 (15.7%) | 48 (33.6%) |

| T2 | 58 (65.2%) | 75 (52.4%) |

| T3 | 9 (10.1%) | 12 (8.4%) |

| T4 | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Lymph node status | ||

| N0 | 40 (44.9%) | 76 (53.1%) |

| N1 | 35 (39.3%) | 47 (32.9%) |

| N2 | 5 (5.6%) | 10 (7.0%) |

| N3 | 9 (10.1%) | 10 (7.0%) |

| Pathological diagnosis | ||

| DCIS | 7 (7.9%) | 7 (4.9%) |

| Invasive | 80 (89.8%) | 135 (94.4%) |

| Others | 2 (2.2%) | 1 (0.7%) |

There were 12 benign operations during the pandemic period. Indications for these operations were biopsies to diagnose granulomatous mastitis, abscess, phyllodes tumours and growing masses suspected of malignancy.

We had no COVID‐19 positive patients during this period.

4. DISCUSSION

Our hospital is a reference centre for cancer patients. During the pandemic period, travel restrictions made it difficult to reach the hospital for some patients. Also, the fear of infection whilst visiting the hospitals caused patients to be wary of hospitals, leading to a noticeable decrease in applications to outpatient clinics.

Breast cancer screening programs could not work effectively during the pandemic. Screening programmes and routine diagnostic imaging were deferred. However, symptomatic patients were diagnosed.

More patients who already had a symptomatic disease and needed treatment came to our hospital during the pandemic, but fewer follow‐up patients and patients with benign disorders. There were fewer wire‐guided biopsies in the pandemic period because of the deferrals of the routine screening programs. The rate of patients diagnosed with breast cancer increased during the pandemic because of decreased patients with benign disorders.

Most of the guidelines suggested postponing surgical treatment for low‐risk patients. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 In an international survey of the European Breast Cancer Research Association of Surgical Trialists (EUBREAST), the results show considerably modified breast cancer treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. 7

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommended priority‐setting of health interventions in oncology during COVID‐19. 8 They categorized the new diagnosis of breast cancer as a high priority as well as symptomatic patients or those with BI‐RADS 5 mammograms. Non‐invasive breast cancers and BI‐RADS 4 mammograms in asymptomatic patients were categorized as medium priority. However, they also suggested postponing primary surgery up to 12 weeks for low‐risk early breast cancer patients.

We limited surgical operations with high and medium‐priority patients in our hospital. On the contrary, as we worked in a non‐infected hospital, most of our surgeons did not postpone surgical operations for early breast cancer patients.

The rate of surgically treated patients in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients was similar. The rate of malignant procedures was higher in the pandemic period because of the reduced number of benign procedures. We did not perform benign procedures except for emergencies and suspected malignancies.

Fear may have affected patients’ decision‐making process and caused them to be more anxious about the spread of COVID‐19. 9 Both patients and surgeons might have preferred more non‐complicated processes to decrease the amount of time spent in hospitals. Besides, our results show that patients seen during the pandemic period had larger tumours with more axillary metastases (Table 3). Increased stages may be related to people waited longer to be seen during the pandemic because of their fear of going to a hospital. Or more severe cases applied to hospitals than patients with asymptomatic tumours. Furthermore, the rate of surgeries after neoadjuvant treatment was higher in the second group. As a result, there was a slightly increased mastectomy rate and a significant increase in stages.

The number of breast cancer operations after neoadjuvant treatment did not change because their treatments had already been planned. Also, the rate of patients referred to neoadjuvant therapy was similar in both groups.

4.1. Study limitations

There are limitations to our study. We need more data covering a longer period of time to consider the pandemic's effect on the stages of cancer. This retrospective single‐centre observational study does not lend sufficient statistical power to draw firm conclusions.

5. CONCLUSION

The hospital in which we were working was a non‐infected hospital, so we could continue with malignant surgeries under the new rules mentioned before. Working in a non‐infected hospital allowed us to continue surgical oncology procedures more securely without compromising scientific suggestions in guidelines for cancer patients. There were no significant differences in our treatment approach for breast cancer patients in our hospital and no extra delays for surgery.

The effects of the Sars‐CoV‐2 pandemic and its spread continue to be seen. Another way has to be found for the treatment of cancer patients but postponing surgical treatment. Non‐infected hospitals may be the answer to this issue.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Cihangir Ozaslan and Gamze Kiziltan. Analysis and interpretation of data: Gamze Kiziltan and Bilge Kagan Cetin Tumer. Drafting of the manuscript: Gamze Kiziltan and Onur Can Guler. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Cihangir Ozaslan and Gamze Kiziltan.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

The data were collected retrospectively and approved by our institutional ethics committee. Also, we obtained permission for this study from the Turkish Ministry of Health Scientific Research Commission (Approval Code: 2020‐07.10T00_25_31) and Institutional Review Board (Approval Code: 2020‐08‐04‐99).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A part of this study was contributed as a poster at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference (https://register.event‐works.com/elsevier/ebcc2020/ps/pd/id/83067/).

Kiziltan G, Tumer BKC, Guler OC, Ozaslan C. Effects of COVID‐19 pandemic in a breast unit: Is it possible to avoid delays in surgical treatment? Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14995. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14995

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Curigliano G, Cardoso MJ, Poortmans P, et al. Recommendations for triage, prioritization and treatment of breast cancer patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Breast. 2020;52:8‐16. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soran A, Gimbel M, Diego E. Breast cancer diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up during COVID‐19 pandemic [published correction appears in Eur J Breast Health. 2020 July 1st;16(3):228]. Eur J Breast Health. 2020;16:86‐88. Published 2020 March 25th. 10.5152/ejbh.2020.240320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tzeng C‐W, Teshome M, Katz MHG, et al. Cancer surgery scheduling during and after the COVID‐19 first wave: the MD Anderson Cancer Center Experience. Ann Surg. 2020;272):e106‐e111. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ng CWQ, Tseng M, Lim JSJ, Chan CW. Maintaining breast cancer care in the face of COVID‐19. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1245‐1249. 10.1002/bjs.11835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Timeline of WHO’s response to COVID‐19 [online]. 2020. [cited 2020 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/29‐06‐2020‐covidtimeline

- 6.COVID‐19 situation report Turkey [online]. 2020; [cited 2020 Dec 6]. Available from: https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/EN‐69532/general‐coronavirus‐table.html

- 7. Gasparri ML, Gentilini OD, Lueftner D, Kuehn T, Kaidar‐Person O, Poortmans P. Changes in breast cancer management during the Corona Virus Disease 19 pandemic: an international survey of the European Breast Cancer Research Association of Surgical Trialists (EUBREAST). Breast. 2020;52:110‐115. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Azambuja E, Trapani D, Loibl S, et al. ESMO management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID‐19 era: breast cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000793. 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vanni G, Materazzo M, Pellicciaro M, et al. Breast cancer and COVID‐19: The effect of fear on patients' decision‐making process. In Vivo. 2020;34:1651‐1659. 10.21873/invivo.11957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.