Abstract

COVID‐19 has become the focal point since 2019 after the outbreak of coronavirus disease. Many drugs are being tested and used to treat coronavirus infections; different kinds of vaccines are also introduced as preventive measure. Alternative therapeutics are as well incorporated into the health guidelines of some countries. This research aimed to look into the underlying mechanisms of functional foods and how they may improve the long‐term post COVID‐19 cardiovascular, diabetic, and respiratory complications through their bioactive compounds. The potentiality of nine functional foods for post COVID‐19 complications was investigated through computational approaches. A total of 266 bioactive compounds of these foods were searched via extensive literature reviewing. Three highly associated targets namely troponin I interacting kinase (TNNI3K), dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP‐4), and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF‐β1) were selected for cardiovascular, diabetes, and respiratory disorders, respectively, after COVID‐19 infections. Best docked compounds were further analyzed by network pharmacological tools to explore their interactions with complication‐related genes (MAPK1 and HSP90AA1 for cardiovascular, PPARG and TNF‐alpha for diabetes, and AKT‐1 for respiratory disorders). Seventy‐one suggested compounds out of one‐hundred and thirty‐nine (139) docked compounds in network pharmacology recommended 169 Gene Ontology (GO) items and 99 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes signaling pathways preferably AKT signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, ACE2 receptor signaling pathway, insulin signaling pathway, and PPAR signaling pathway. Among the chosen functional foods, black cumin, fenugreek, garlic, ginger, turmeric, bitter melon, and Indian pennywort were found to modulate the actions. Results demonstrate that aforesaid functional foods have attenuating roles to manage post COVID‐19 complications.

Practical applications

Functional foods have been approaching a greater interest due to their medicinal uses other than gastronomic pleasure. Nine functional food resources have been used in this research for their traditional and ethnopharmacological uses, but their directive‐role in modulating the genes involved in the management of post COVID‐19 complications is inadequately studied and reported. Therefore, the foods types used in this research may be prioritized to be used as functional foods for ameliorating the major post COVID‐19 complications through appropriate science.

Keywords: ADME, cardiovascular diseases, COVID‐19, diabetes, functional food, molecular docking, network pharmacology, post COVID‐19 complications, respiratory diseases

Therapeutic potential food sources and their approach to be used in post COVID‐19 complications.

Highlights

This article rediscovers the benefits of nine chosen functional foods.

Black cumin, Indian pennywort, fenugreek, fish oil, garlic, ginger, bitter melon, peppermint, and turmeric in improving post COVID‐19 complications.

Bioactive compounds in the mentioned foods are studied upon and analyzed by ADME to find how they are processed in a living system.

Network pharmacology analysis revealed the synergistic nature of the compounds and interaction with the genes.

Combination of the most enriched and highest interacted compounds in the created network could be chosen for mitigation of complications from post infection via SARS‐CoV‐2.

Molecular docking further analyzed the binding affinity of the finally screened bioactive compounds with MAPK‐1, HSP90AA1, AKT1, PPARG, and TNF‐alpha targets.

1. INTRODUCTION

In late December 2019, the first few cases of pneumonia from an unknown cause were reported in Wuhan, China, which started to increase in number very rapidly. By 30 January 2020, there were already about 7,734 reported cases in China along with increasing incidences abroad—all associated with a novel (new) coronavirus (Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020). This coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19 as named by WHO) is an infection primarily targeting the human respiratory system, caused by the enveloped RNA β coronavirus named SARS‐CoV‐2 and belongs to the large family of coronaviruses that have previously caused outbreaks namely Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)‐CoV and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)‐CoV (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020). With the rapid human‐to‐human transmission resulting in increased morbidity and mortality, COVID‐19 was soon declared a pandemic on 11 March 2020 by WHO (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020).

The population that seems to be affected most are those of older age, suppressed immune systems, and with pre‐existing health conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular disease etc. Most patients with COVID‐19 acquired symptoms ranging from fever, cough, myalgia, fatigue, and sputum production to lesser common incidents of diarrhea, dyspnea, nausea, lymphopenia, and others, in approximately 5.2 days from incubation, depending on the age group and immunity (Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020). Although lungs are the principal organs for the infection, the virus reportedly binds to angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors abundant in the lower respiratory tract, heart, intestinal epithelium, vascular endothelium, kidney, etc. making them susceptible to severe complications elsewhere in the body too (Rothan & Byrareddy, 2020; Silva Andrade et al., 2021). The SARS‐CoV‐2 infection has also shown to initiate a “cytokine storm”—a hyperinflammatory response, whereby too many immune cells are activated, and they subsequently release inflammatory cytokines and chemical mediators like interleukins like IL‐6, IL‐2, IL‐7, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interferon‐inducible protein (IP)‐10, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)‐1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)‐1α, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF), C‐reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin, and ferritin (Hu et al., 2021). Hence, these causes immune‐mediated injuries to other organs alongside lungs and are considered as one of the main reasons for deaths in COVID‐19‐infected patients (Hu et al., 2021).

Till date, COVID‐19 infection has shown to have long‐term widespread complications in the cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, neurovascular, and gastrointestinal (GI) systems, some of which will be discussed further in this study. To make it worse, first few therapeutic regimens did not include an antiviral drug specific to destruction of this virus but rather involved disease curative treatments, which make use of clinically approved antivirals, IL‐6 receptor (IL‐6R) antagonists tocilizumab, hydroxychloroquine, immunosuppressant drugs, etc. (Hu et al., 2021). Several other repurposed drugs such as remdesivir and favipiravir have been shown to alleviate some of the COVID‐19 symptoms (Tarighi et al., 2021). Another mode of therapy used was the plasma transfusion from COVID‐19 survivors, preferably collected within 2 weeks after recovery, given to infected patients (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2020), while still waiting for achieving herd immunity via safe use of vaccines (Forni and Mantovani, 2021; Zhai et al., 2020). Hence, we are still racing against time to find ways to stay healthy naturally in the meanwhile.

Because there are chances of mutation of the virus, new variants were being reported namely alpha (B.1.1.7) in the United Kingdom, beta (B.1.351) in South Africa, gamma (P.1) in Brazil, delta (B.1.617.2) in India alongside other variants of interest as mentioned by WHO (WHO, 2021). It means that it may persist in the human population for longer than expected, eventually leading to a number of complications. Moreover, a report from CNN health also stated that months after the initial infection/recovery, some monitored patients still experienced mild symptoms; developed on and off health problems like terrible sinus pain, nausea, loss of appetite, bone‐crushing fatigue, burning sensation in chest, dry cough, brain fog, etc. or even worse they never go back to the active lifestyle they led prior to COVID‐19 infection (Gupta, 2021). Their condition may be referred to as long COVID, continued COVID‐19, post COVID‐19 syndrome, or post‐acute COVID‐19 syndrome (Gupta, 2021; Silva Andrade et al., 2021). This among many other reasons suggests that it is the best to prepare for a healthier lifestyle to improve the post COVID‐19 complications alongside therapy, and we believe there is good scope for doing so naturally using functional food in diet. “Functional food” is a phrase with rather debatable definitions, most of which refers to food whose components may provide positive effects on health or reduce risk of evolution of existing or possible diseases, beyond intake of basic nutrition (Siro et al., 2008; Viuda‐Martos et al., 2010). With increased cost of healthcare services, the desire to stay fit at middle to older age has become more important with time and functional food in diet play a role in this regard (Siro et al., 2008; Viuda‐Martos et al., 2010). Examples of functional food that are readily available and cheap and were reported to improve health in case of some of the diseases like cardiovascular, respiratory, and diabetes are black cumin, tomato, Indian pennywort, fenugreek, fish oil, garlic, ginger, Momordica (bitter gourd), peppermint, turmeric, pumpkin, etc. (Asgary et al., 2018; Gholamnezhad et al., 2015; Perera & Li, 2012). As stated above that cardiovascular (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020; Silva Andrade et al., 2021), respiratory, and nephrological complications are among the many complications in patients of post COVID‐19 infections (Iwasaki, 2021; Silva Andrade et al., 2021), we tried to rediscover the potential use of some selected functional food sources, analyze their chemical compounds and their mechanism of action in ameliorating the post COVID‐19 complications, via ADME, bioinformatics‐based network pharmacology and molecular docking study.

2. SELECTED FUNCTIONAL FOOD AND ITS BIOACTIVITIES

Functional foods have evolved as foods or food products having a role beyond gastronomic pleasure, energy and nutrient supply. Tremendous benefits of functional foods have been alluring scientists to look into their molecular approach of therapeutic potentiality. Enormous numbers of functional or medicinal foods are literally cited and based on their traditional uses, perceived feedback and screening data guided future prospects, and we have focused on the following functional foods for their uses in long‐term post COVID‐19 complications.

2.1. Black cumin (Nigella sativa)

Black cumin (Nigella sativa), belonging to the family Ranunculaceae (Iqbal et al., 2017), has been very commonly used in India and the Middle Eastern population as a spice, preservative for food and medicine since long ago. Its seeds are rich in oil, proteins, minerals, and carbohydrates (Iqbal et al., 2017). The oil contains unsaturated fatty acids, terpenoids, and quinones like thymoquinone, along with small amount of alkaloids—all of which are good for memory (Fontanet et al., 2021). Most of N. sativa’s pharmacological activities were reported to be due to its active compounds thymoquinone, p‐cymene, and α‐thujene (Silva Andrade et al., 2021). Its alkaloids such as nigellicine, nigellidine, and nigellimine have shown to reduce cholesterol levels, hence being potentially beneficial against cardiovascular diseases (Asgary et al., 2018). Thymoquinone also showed similar effects by reducing total cholesterol, LDL‐C, triglyceride [TG], and thiobarbituric acid (TBA)‐reactive substance’s concentrations and increasing the helpful high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C) concentrations in animal fed with cholesterol diet (Shabana et al., 2013). One of the suggested mechanisms for this hypolipidemia is the prevention of the de novo cholesterol synthesis, whereas another could be due to activation of bile acid secretion (Shabana et al., 2013). Similarly, N. sativa has also reduced chances of aortic plaque formation directly and indirectly via controlling the inflammatory mediators released by macrophages that take up LDL and form foam cells’ preliminary stage in atherosclerosis (Shabana et al., 2013).

On the other hand, it has gained a lot of importance due to its antidiabetic activity when tested in rats and less commonly on human subjects where both showed hypoglycemic results (Shabana et al., 2013). The underlying mechanism is predicted that the N. sativa, and its components are able to sustain the beta cell integrity and regeneration of such cells, leading to increased insulin production (Shabana et al., 2013). Some other explanations of the antidiabetic property suggested extra pancreatic actions (exclusive of insulin release) (Shabana et al., 2013) and decrease in hepatic gluconeogenesis (Srinivasan, 2018). In another animal study, it has reportedly inhibited intestinal absorption of glucose, in vitro and in vivo alongside causing insulin sensitization in skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver via upregulation of adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPAR‐ɣ), and increasing the amount of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) proteins (Viuda‐Martos et al., 2010).

N. sativa is also useful in treating inflammatory pulmonary responses. In one such study, it decreased iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) activity and increased surfactant protein D when experimented on rats after pulmonary aspiration (Srinivasan, 2018). Moreover, it also alleviated health conditions in patients with hyperoxia‐induced lung injury or even asthma. Thymoquinone plays a role here by the inhibition of the formation of leukotrienes which are potential inflammatory mediators in asthma, hence improving chest wheezing, pulmonary function tests, and other asthma symptoms (Srinivasan, 2018). Additionally, tests performed on guinea pigs demonstrated antitussive activity of N. sativa that was comparable with codeine (Maideen, 2020). Subjects exposed to aerosols of N. sativa and codeine had fewer coughs than those exposed to saline. Thymoquinone was predicted to exert such an effect via opioid receptors since pretreatment of subjects using 2 mg/kg naloxone (opioid antagonist) blocked such antitussive effect (Maideen, 2020).

2.2. Indian pennywort (Centella asiatica L. urban sys.)/Gotu Kola/Thankuni

Gotu Kola falls in the genus Centella (Syn. Hydrocotyle) of Apiaceae family (previously known as Umbelliferae) and subfamily Mackinlayoideae. It is a plant that has the reputation to heal abnormal metabolic conditions in folk medicine, especially in the Ayurvedic system. Extract of Centella asiatica has been tested against endocrine diseases like obesity, osteolytic bone diseases and type 2 diabetes (Rameshreddy et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). These reasons led us to select this functional food to combat the post COVID‐19 complications in patients with diabetes. The most vital bioactive components of C. asiatica were categorized into major collections, which contained triterpenoids saponins and their aglycones correspondents (asiaticoside, madecassoside, asiatic acid, and madecassic acid), and pectin, volatile oil, traces of alkaloids, and others (Hashim et al., 2011). Triterpenes are the best bioactive chemical components responsible for pharmacological activity. Asiaticoside, Asiatic acid, Madecassoside, and Madecassic acid are the most common of them (Inamdar et al., 1996; Lv et al., 2018). Some pentacyclic triterpenoids including asiaticoside, brahmoside, and madecassic acid, along with other constituents for instance centellose, centelloside, and madecassoside are also bioactive compounds of C. asiatica. Sun et al. (2020) stated in their review study that Madecassoside, Asiaticoside, Madecassic acid, and Asiatic acid are widely distributed in the body, whereas Madecassoside and Asiaticoside may exert their biological activity through conversion into aglycone (Madecassic acid and Asiatic acid) (Sun et al., 2020). They concluded these characteristics of compounds with the help of the experiments done by other researchers (Sun et al., 2020). Many in vitro, in vivo, and also in silico studies were conducted to investigate the antidiabetic activity of it. Ethanol extract of C. asiatica has given highly propitious hypoglycemic activity as its extract inhibited absorption of glucose by inhibition of both intestinal disaccharidase enzyme and α‐amylase 1 (Berawi et al., 2017; Kabir et al., 2014). Fitrawan et al performed in vitro experiment on C. asiatica fraction with the combination of Andrographis paniculata herb fraction and found that 10 and 30 μg/ml concentrations, respectively, were able to increase insulin‐stimulated glucose uptake (Fitrawan et al., 2018). Assessment of the antidiabetic activity of ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extract fraction and isolated compounds were conducted against yeast α‐glucosidase. Yeast α‐glucosidase enzyme from S. cereviseae could be categorized as α‐glycosidase type and hence was selected for general screening of α‐glycosidase inhibitors. Further investigation revealed that kaempferol and quercetin are the most active inhibitors (Dewi & Maryani, 2015). Chauhan et al confirmed with their in vivo study on alloxan‐induced rats with diabetes using methanolic and ethanolic extracts that this herb has significant antihyperglycemic activity (Chauhan et al., 2010). Antioxidant potential of C. asiatica has been reported in many studies (Zainol et al., 2003), and this effect is related to the hypoglycemic mechanism of this food. So, triterpene compounds function against diabetes mellitus by reducing the oxidative stress and facilitating the anti‐inflammatory activity. Antioxidative activity of the extracts was measured using the ferric thiocyanate method and TBA test. The antioxidative activities were then compared with that of α‐tocopherol (natural antioxidant) and butylated hydroxytoluene or BHT (synthetic antioxidant). The antioxidant activity of Centella extract was evaluated by measuring its ability to scavenge 2,2‐diphenyl‐1‐picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radicals (Hashim et al., 2011; Mensor et al., 2001). Hashim et al. (2011) compared with other natural antioxidants, Centella showed better antioxidant effects than a great grape seed extract.

2.3. Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum‐graecum L)

Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum‐graecum L) is a 20–130 cm long, straight, rarely ascending, annual legume plant. Seed is the part that is used and could be rectangular to rounded (Petropoulos, 2002). It falls in the Rosaceae order, Legouminosae family, subfamily Papilionacea, and is distributed in Iran, India, Egypt, Pakistan, Algeria, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. From the data of ancient times, religious scripture, travel records and anecdotes belonging to different continents and from different periods of human history, a range of medicinal properties were acknowledged. Egyptian traditional medicine, Chinese traditional medicine, and Ayurvedic medicines have been extensively using this for making their formulations (Morcos et al., 1981; Yoshikawa et al., 1997). Romans used it to facilitate labor and deliver, whereas in Chinese medicine fenugreek seeds are considered tonic as well as a treatment for weakness and legs edema (Patil et al., 1997; Yoshikawa et al., 1997). Many pharmacological activities have been reported on fenugreek, experimented by many researchers. Fenugreek seeds are known to be effective against cardiovascular problems. Its lipid‐lowering activity makes this a potential functional food against cardiovascular diseases. It can lower the level of low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) in the blood; consequently, it is effective in combating hypercholesterolemia (Ribes et al., 1987; Sharma, 1984). Active compound diosgenin in fenugreek was observed to show significant hypercholesteremic activity in vitro and in vivo studies (Malinow, 1985; Malinow et al., 1978). Olfa Belguith‐Hadriche and his team (2013) studied methanol and ethyl acetate extracts of fenugreek and concluded that the flavonoids in fenugreek could be responsible for the hypercholesteremic activity (Belguith‐Hadriche et al., 2013; Hernandez‐Galicia et al., 2002). Fenugreek also shows hypoglycemic activity claimed by many researchers. They were helpful in achieving good glycemic control in type 2 diabetes (Bouyahya et al., 2020; Büyükbalci & El, 2008; Capetti, 2020; Hernandez‐Galicia et al., 2002). Animal studies also explain antidiabetic activity of fenugreek. Fenugreek powder, suspension, decoction, and even oil fraction showed good antidiabetic activity on diabetic animals’ in vivo (Ajabnoor & Tilmisany, 1988; Khosla et al., 1995; Madar, 1984; Mishkinsky et al., 1974; Ribes et al., 1986).

Ben‐Arye et al. (2011) experimented on aromatic herbs for the ailment of upper respiratory tract problems and observed peppermint spray was showing significant effects (Ben‐Arye et al., 2011; Schilcher, 2000). They could be useful to combat common cold and other respiratory tract problems which were exhibited in vitro studies (Ács et al., 2016; Fabio et al., 2007; Li et al., 2017). Animal studies show that Mentha piperita is antispasmodic to tracheal smooth muscle (de Sousa et al., 2010), stimulates cold receptors (Shah & Mello, 2004), and shows antitussive effect on guinea pigs (Laude et al., 1994). Compound of M. piperita, Menthol showed healing effect on capsaicin and neurokinin A induced airway restriction plus helped in relaxing potassium chloride (KCl) and acetylcholine induced bronchoconstriction ex vivo.

2.4. Fish oil

In recent years, fish oil supplements have been promoted as health‐protective in different ailments. People with more fish intake in their diet reported lesser incidences of stiffening of arterial walls, platelet aggregation in blood circulation, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart diseases following that (Kundam et al., 2018). Even patients who already developed cardiovascular disorders were benefited from a small inclusion (150 g) of fish intake, preventing further complications (Kundam et al., 2018). Fish oil supplements in diet, following ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury also alleviated changes associated with it‐ for example decreased cardiac contraction force, increased coronary perfusion pressure, ventricular arrhythmia, and release of creatine kinase and thromboxane B2 (Kundam et al., 2018). As we know, fish is a functional food with plentiful minerals, vitamins, proteins, and essential fatty acids. Fish oil from the liver, contains vitamin A, vitamin D, omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid, and many more bioactive compounds responsible for the aforementioned health benefits (Kundam et al., 2018; Sidhu, 2003). Moreover, the cardiovascular diseases are associated with increased plasma cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides, raised blood pressure along with decreased levels of HDL, whereas the omega‐3 PUFAs in fish oil (mainly EPA and DHA) have shown to lower blood pressure and viscosity. They may also cause slight elevation of HDL2 levels, hence reducing the overall risks of coronary heart disease (Kundam et al., 2018). Following the control of triglyceride levels and hypertension in a patient, omega‐3 PUFAs are also able to reduce chances of insulin resistance and hence diabetes mellitus (Kundam et al., 2018; Sidhu, 2003). Another study showed that 150 g of salmon intake for three times in a week, led to reduction of C‐reactive protein, IL‐6 and prostaglandins which are inflammatory markers, hence improving immune function (Sidhu, 2003). Occurrence of asthma and allergic reactions will also decrease on eating sufficient fish meals (Kundam et al., 2018).

2.5. Garlic (Allium sativum)

Allium sativum has been cultivated worldwide and used in diversified ways in different countries for thousands of years (Beato et al., 2011). A. sativum generally named as (Rashun in Bengali) falls in the family of Alliaceae and plant order Liliales (Rocio & Rion, 1982). It is generally famous for its culinary use in many parts of the world, especially in Asia. Garlic is an erect, monocot, and bulbous crop, which is known as a perennial plant that is sterile and propagates asexually because it does not produce seeds, thus called a diploid plant (Benke et al., 2018; Mayer et al., 2013; Rocio & Rion, 1982). Garlic has the reputation of being a traditional remedy as an antihypertensive agent. Garlic is being used by the traditional healers of many countries as a prophylactic as well as for making their folk medicine against a variety of diseases (Duke & Ayensu, 1985). Its compounds were investigated against hypertension and a sulfur compound alliin (S‐allyl cysteine sulfoxide) showed significant antihypertensive effect as well as also increased the efficacy of other cardioprotective agents like captopril (Duke & Ayensu, 1985). It can inhibit the Squalene Monooxygenase enzyme by binding with vicinal sulfhydryl part of the enzyme and reduce cholesterol production (Gupta & Porter, 2001). Garlic oil showed hypolipidemic effect in rats fed a high‐fat diet (Gupta & Porter, 2001; Yang et al., 2018). Platelet aggregation is a noteworthy cause of cardiovascular disease, and garlic can suppress aggregate formation in many different pathways, thus can be considered as a better cardioprotective agent (Isensee et al., 1993; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Rahman, 2007).

In vitro experiments proved that four compounds of garlic namely allyl cysteine, alliin, allicin, and allyl disulfide have antioxidant properties and exhibit protection against free radical scavenging (Wang et al., 2016) for being antioxidant (Yang et al., 2001). Another work demonstrated that six organosulfur compounds (DAS, diallyl sulfide; DADS, diallyl disulfide; SAC, S‐allylcysteine; SEC, S‐ethylcysteine; SMC, S methylcysteine; SPC, S‐propyl cysteine) derived from garlic hinder further oxidative and glycative deterioration of partially oxidized and glycated LDL or plasma that is effective against diabetes‐related vascular disease (Asdaq & Inamdar, 2010; Huang et al., 2004). Significant fact is that home‐cooked garlic also retains the antioxidant activity of it (Locatelli et al., 2017). As garlic has a good antioxidant property that links it with its antidiabetic activity. Phenol‐rich garlic extract is found to be potent hypoglycemic agent (Akolade et al., 2019). Garlic when taken along with metformin (a hypoglycemic drug, which shows remarkable decrease in fasting blood glucose level and LDL level in patients with type 2 diabetes) (Chhatwal, et al., 2012). Cholesterol level can be controlled by modifying one’s diet with garlic. Studies show that garlic could be used to lower the cholesterol level (Kamanna & Chandrasekhara, 1984; Kannar et al., 2001). But precisely, the essential oil of garlic was tested for cholesterol lowering effect and showed most of the hypocholesterolemic effect comes from that portion (Kamanna & Chandrasekhara, 1984). Garlic lowers the LDL and increases HDL in the rat model (Aouadi et al., 2000). Garlic also shows synergistic effect with medicine like glibenclamide (Poonam et al., 2013).

2.6. Ginger

Zingiber officinale belonging to the Zingiberaceae family and the Zingiber genus (Shahrajabian et al., 2019), is a common spice of choice when it comes to improving health conditions in patients with pulmonary fibrosis, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, and many inflammatory responses (Thota et al., 2020). It consists of plenty of phenolic compounds, terpenes, lipids, and organic acids, out of which gingerols, shogaols, and paradols have gained lot of importance as bioactive compounds are responsible for beneficial pharmacological effects (Mao et al., 2019). Fresh ginger is rich in gingerols like 6‐gingerol, 8‐gingerol and 10‐gingerol, which later changes into corresponding shogaols on heat or storage (Mao et al., 2019). Ginger exerted cardioprotective effects by increasing the levels of HDL‐C directly and indirectly by increasing apolipoprotein A‐1 and lecithin‐cholesterol acyltransferase mRNA in the liver, both being essential part of HDL formation (Mao et al., 2019). In addition to that, ginger extract reduced body weight, total cholesterol, and LDL in high‐fat‐diet rats, possibly due to the expression of peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARα and PPARγ). Ginger also helped reduce blood pressure in hypertensive rat models, whereas 6‐shogaol increased the number of cells in G0/G1 phase and activated Nrf2 and HO‐1 pathways, hence exerting antiproliferative effects. ACE1 and arginase activities were downregulated and NO upregulated, hence causing vasodilation. Ginger was also said to reduce platelet adenosine deaminase activity and hence increase in adenosine levels, which has shown to prevent platelet aggregation and cause vasodilation in rats (Mao et al., 2019).

Ginger has played an important role in controlling disease conditions like diabetes indirectly via management of obesity. Moreover, both six shogaol and six gingerol inhibited the production of advanced glycation end products that lead to pathogenesis of diabetic complications like retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiomyopathy (Mao et al., 2019). Six‐paradol and 6‐shogaol also caused better glucose utilizations in 3T3‐L1 adipocytes and C2C12 myotubes via increased phosphorylation of AMPK. Among the many animal studies conducted, they have proved beneficial properties of 6‐gingerol, which caused glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion, improved glucose tolerance in type 2 diabetic mice via increased glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) hormones, activated glycogen synthase 1, and increased presence of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT 4) to cause more glycogen storage in skeletal muscles (Mao et al., 2019). Overall, bioactive constituents of ginger have shown to be antidiabetic for patients perhaps not by decreasing the level of insulin but increasing the sensitivity of it (Mao et al., 2019). In terms of respiratory complications, ginger’s constituents—6‐gingerol, 8‐gingerol, and 6‐shogaol have shown to relax the airway smooth muscle in both guinea pig and human trachea models. Possible explanations of the effect could be attenuation of airway resistance in mice, due to the reduction of Ca2+ influx caused by 8‐gingerol and another could be due to suppression of phosphodiesterase 4D in humans (Mao et al., 2019). Patients with allergic asthma symptoms and even ARDS, which also happen to be common incidences in patients with COVID‐19 (Silva Andrade et al., 2021; Thota et al., 2020), were benefited from ginger‐rich diet where its constituents improved gaseous exchange in lungs and prevented alveoli abnormalities, wall thickening, infiltration of multinucleated cells and pneumocytes, lung cell proliferation, and even fibrosis. In a study, 32 ARDS patients were compared with placebo, where 120 mg of ginger extract has increased the tolerance of enteral feeding, reduced nosocomial pneumonia, and even reduced number of days requiring external ventilation in ICU (Thota et al., 2020). Citral and eucalyptol in ginger oil also successfully inhibited tracheal contraction in rats when induced by carbachol (Mao et al., 2019). Zingerone in ginger has shown to reduce pulmonary fibrosis, fibrosis marker, hydroxyproline, oxidative stress marker, and malondialdehyde. Instead, reduced glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH‐Px), etc., antioxidant markers in the lungs were increased in rats pretreated with bleomycin. As we know, patients with COVID‐19 face hyperinflammatory reactions, it is also essential to note that constituents of ginger have been successful in reducing TNF‐α, IL‐β, and kidney injury markers (KIM‐1) (Chhatwal et al., 2012).

2.7. Bitter melon (Momordica charantia L)

Momordica charantia L. (bitter melon) is seen in tropical regions precisely in India, China, East Africa, and Central and South America and usually cultivated as a vegetable (Walters & Decker‐Walters, 1988). The most used parts of M. charantia are fruits, leaves, and roots, which have been extensively used in Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine against many diseases, as a bitter stomachic, laxative, anthelmintic, antidiabetic, jaundice, stones, kidney, liver, fever (malaria), eczema, gout, fat loss, hemorrhoids, hydrophobia (Ahmad et al., 2016; Begum et al., 1997). The fruit tastes bitter as the name suggest and, the palatability of this vegetable is known as “an acquired taste.” This has been used in diabetes mellitus (Baldwa et al., 1977; Krawinkel & Keding, 2006). It has a good proportion of vitamins, minerals, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds (de Melo et al., 2000; Horax et al., 2005). Other bioactive compounds like saponins, peptides, and alkaloids are also present as well as seeds contain essential oils (de Melo et al., 2000. Bitter melon has the reputation for being a potential antidiabetic and hypoglycemic plant in many traditional medicines and that attracted researchers to investigate its activity to get precise data of its activity. In vitro and in vivo studies show quite good results for non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM, type II) and insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus (type I) (Ahmad et al., 2012; Beloin et al., 2005; Grover & Yadav, 2004). Leatherdale et al. (1981) run an experiment in nine Asian NIDDM outpatients, which concluded bitter melon juice intake in glucose load caused significant improvement in glucose tolerance without increasing the insulin levels in the blood (Leatherdale et al., 1981). Srivastava et al. (1993) showed that it has a chronic effect on NIDDM as 3–7 weeks of consumption of dried fruit caused noteworthy fall in postprandial blood glucose levels. They also showed that the aqueous extract of bitter melon caused a significant fall in blood and urine sugar level within 7 weeks of time (Leatherdale et al., 1981; Srivastava et al., 1993) investigated on the seed oil of M. charantia, and it suggested that it is a potent antidiabetic agent, with the help of α‐glucosidase and α‐amylase inhibition assays. Their study shows that seed oil causes inhibition of α‐glucosidase more than α‐amylase. From in vitro study done by Cumming and Hundal, it is seen that the fresh juice of the plant causes significant increase in the uptake of amino acids in the skeletal muscle and also increased glucose uptake in L6 myotubes (Cummings et al., 2004). Other researches on the aqueous and chloroform extracts also confirmed increased glucose uptake and upregulated GLUT‐4, PPAR‐γ, and phosphatidylinositol‐3 kinase (PI3K) in L6 myotubes (Kumar et al., 2009). Another study on the adipose cell 3T3‐L1 was conducted to investigate glucose uptake and adiponectin secretion and concluded that the water‐soluble part of the plant increased the glucose uptake at suboptimal concentrations of insulin in 3T3‐L1 adipocytes (Meir & Yaniv, 1985). In vitro and in vivo pharmacological studies describe that bitter melon extracts and bioactive compounds facilitate the regulation of glucose uptake (Meir & Yaniv, 1985; Roffey et al., 2007) stimulation of insulin secretion from pancreatic cells (Keller et al., 2011), prevent pancreatic β‐cells from inflammatory conditions, display insulin mimetic activities, and reduce lipid accumulation in adipocytes (Popovich et al., 2010). In vivo studies on animal models also show antihyperglycemic activity. Aqueous, alkaline, and chloroform extracts of bitter melon in normal mice lessen the glycemic response of both oral and intraperitoneal glucose load (Day et al., 1990). Ali, Khan, and colleagues investigated pulp juice, and their result depicts lowered fasting blood glucose and glucose intolerance in NIDDM model rats (Ali et al., 1993). Later on Srivasta et al. showed blood sugar level had fallen after 3 weeks of treatment with aqueous extract of bitter melon in alloxan‐induced diabetic rats (Srivastava et al., 1993). The extract also improved glucose intolerance in streptozotocin (STZ)‐treated diabetic rats and increased the glycogen synthesis in the liver (Sarkar et al., 1996). Virdi, Sivakami, and team administered 20 mg/kg body dose of fresh unripe fruits, in rats and observed 48% reduced fasting blood glucose, which was similar to glibenclamide, a well‐known oral antidiabetic drug (Virdi et al., 2003). Dose‐dependent hypoglycemia in normal (normoglycemic) and streptozotocin (STZ)‐treated diabetic rats was observed by the administration of the whole plant extract (Ojewole et al., 2006). Other studies described that M. charantia extract enhanced insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and insulin signaling in high‐fat diet‐induced insulin resistance rats (Sridhar et al., 2008) and also levelled up the normal glucose concentration in chronic sucrose‐loaded rats (Chaturvedi & George, 2010). Some studies suggested bitter melon juice could be used as an antidiabetic remedy by using them through crushing and straining the unripe fruit and taken once or twice a day. They can also be taken as a decoction or “tea” (hot water extract) of the aerial parts of the plants, free of large fruit (Bailey et al., 1986). The immature fruits of M. charantia can be prepared in many ways. Moreover, they can also be dehydrated, pickled, or canned and could be blanched or soaked in salt water before cooking to reduce the bitter taste (Grover & Yadav, 2004).

2.8. Peppermint (Mentha piperita L)

M. piperita L belongs to the Lamiaceae family (mint family) and is a perennial, glabrous, and strongly fragrant herb. This is known as peppermint and is native to Europe, found in the northern USA and Canada, and cultivated in many parts of the world (McKay et al., 2006). Temperate and subtropical areas have been the zone for cultivation for more than 1,000 years (Benabdallah et al., 2018). The list of purported benefits and uses of peppermint as a folk remedy or in complementary and alternative medical therapy include the following: biliary disorders, dyspepsia, enteritis, flatulence, gastritis, intestinal colic, and spasms of the bile duct, gallbladder, and GI tract (Mahendran & Rahman, 2020; McKay et al., 2006). Its leaves are used as carminatives and for gastric problems. They are also used as stimulants, in vomiting, liver problems and gallbladder infection. Traditional uses have been reported in many forms. In vivo and in vitro studies have been done extensively to understand its pharmacological activity. An antibacterial study on respiratory tract pathogens Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus done by Inouye et al. (2001). They used modified dilution assays and further which showed that peppermint oil has significant effect on respiratory tract infections and suggested that menthol and menthone are the most effective compounds (Bahl et al., 2000; Inouye et al., 2001) along with other terpene molecules (Phatak & Heble, 2002). A similar experiment was done by (Furuhata et al., 2000). They estimated time‐course changes in the bacterial count of L. pneumophila in the extract solutions of peppermint and found that the bacterial count became undetectable after 3–12 hr of peppermint treatment (Furuhata et al., 2000). Later on, many studies also proved its activity against respiratory tract pathogens (Ács et al., 2016; Ács et al., 2018). Another significant compound of peppermint is 1,8‐cineole 200 mg dose of which reduced the medication rate to 36% for asthmatic patients who were taking prednisolone (Juergens et al., 2003). It showed good anti‐inflammatory activity (Juergens et al., 2003). Morice et al. explained peppermint oil as antitussive agent (Morice et al., 1994). M. piperita is also known to have antispasmodic activity, which was observed on rat trachea involving prostaglandins and nitric oxide synthase by de Sousa and his team (de Sousa et al., 2010). From the studies of traditional medicine, it was depicted that M. piperita has been widely used for respiratory tract diseases. Its leaves, infusions, or essential oil used to be good expectorant and anticongestive (Morice et al., 1994). Latest study on peppermint done by Cam, Basyigit, and team with powdered peppermint extract, which proved that it is potent antidiabetic and antihypertensive functional food. Eriocitrin is a dominant phenolic compound, and (Cam et al., 2020) antidiabetic and antihypertensive activities were evaluated by the degree of inhibition of (α‐glucosidase) and angiotensin 1‐converting enzyme, ACE, respectively.

2.9. Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L.)

Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) is a functional food belonging to the Zingiberaceae family and is a spice that has been an essential part of cooking Asian cuisine and in traditional medicine like Ayurveda (Niranjan & Prakash, 2008), Unani and Chinese medicines for centuries (Niranjan & Prakash, 2008). Its bioactive compounds are basically phenols, terpenes, sterols, and alkaloids in nature (Emirik, 2020). Curcumin in turmeric is a phenol that has good hopes for use in patients with COVID‐19 as it has previously been effective against influenza A virus, HIV, enterovirus, 71 (EV71), herpes simplex virus and even inhibited the replication of SARS‐CoV and inhibited 3 Cl protease in Vero E6 cells when tested (Babaei et al., 2020). In terms of improving post COVID‐19 complications, curcumin and tetrahydro curcumin have shown to reduce blood sugar and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in rats, hence proving to be antidiabetic (Niranjan & Prakash, 2008). Turmeric also reduced oxidative stress due to the decrease of glucose in the polyol pathway leading to increased NADPH/NADP ratio and increased GSH‐Px activity, which is an antioxidant enzyme (Mao et al., 2019). Turmeric may also be useful because of its ability to reduce the levels of circulating inflammatory mediators like IL‐6 and TNF‐α, cytokines, chemokines, bradykinin, transforming growth factor‐beta‐1 (TGF‐β1), cyclooxygenase (COX), plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1), IL‐17A, and caspase‐3 (Cas‐3) (Babaei et al., 2020; Locatelli et al., 2017). Most importantly, it can target the proinflammatory NF‐κB pathway, hence protecting against acute lung injury and ARDS, commonly seen in patients with COVID‐19. Curcumin also inhibits the activity of bradykinin, hence suppressing coughs induced by it. Moreover, it decreased interstitial fibrosis and bronchoconstriction. Curcumin may also delay fibrosis progression by inhibiting the synthesis of collagen and procollagen I mRNA, thus decreasing collagen deposition found in pulmonary fibrosis (Madar, 1984). Turmeric extract (1.5, 3 mg/ml) has shown to reduce tracheal contraction induced by ovalbumin and showed maximum response to methacholine in rats (Babaei et al., 2020). Capsule Curcumin 500 mg BD improved forced expiratory volume (FEV1) in comparison with standard therapy for bronchial asthmatic patients when taken daily for 30 days (Babaei et al., 2020). Hence, it is potential in improving post COVID‐19 respiratory symptoms and complications remain notable.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Selection of functional food sources

The nine functional foods namely black cumin, Indian pennywort, fenugreek, fish oil, garlic, ginger, bitter melon, peppermint, and turmeric were shortlisted because of the positive effects they possess in ameliorating cardiac, diabetic, and respiratory complications that are common in patients of post COVID‐19 survival. It was also taken into account that the above chosen foods were affordable and readily available for consumption by the mass population, even in developing countries like Bangladesh. Then bioactive compounds in those foods were listed, as many as possible based on extensive research and literature search.

3.2. Library preparation and ADME study

A library of 266 bioactive compounds present in the selected functional foods has been prepared. Compounds were downloaded from the “PubChem” and “Chemspider” database, and the library was compiled. Duplicate compounds were deleted. Compounds were subjected to ADME analysis. We used the webserver SwissADME (Daina et al., 2017) to analyze the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination properties of the compounds. Moreover, drug likeness properties were evaluated by analyzing the number of H‐bond acceptor, H‐bond donator, solubility class, and Lipinski’s rule of five criteria (Barret, 2018).

3.3. Primary virtual screening via molecular docking for network pharmacology study

After ADME screening, these compounds were subjected to molecular docking analysis and network pharmacology studies using the following methodological approaches.

3.3.1. Protein selection TNNI3K

Three proteins namely troponin I interacting kinase (TNNI3K, PDB ID: 4YFI), dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4, PDB ID: 6B1E), and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF‐β1, PDB ID: 6B8Y) for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and respiratory disease, respectively, were selected for first molecular docking studies. These proteins were selected based on literature studies of post COVID‐19 complications. Cardiac TNNI3K is a kinase of cardiomyocyte, which causes IR injury by oxidative stress. As a result, cardiomyocyte death, ischemic injury, and myocardial infarction occur (Lal et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Post COVID‐19 patients show cardiomyocyte‐related complications; thus, TNNI3K was selected as the target. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and related cytokine storm causes an increase in DPP‐4‐integrin‐β1 interactions, also induce mesenchymal activations and profibrotic signaling in the kidney cells. This can lead to higher extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, collagens, and accumulation of fibronectin. Inhibiting DPP‐4 counterbalances the mesenchymal transition processes and suppresses pro‐fibrotic signaling, ECM deposition, fibronectin, and collagen accumulation (Srivastava et al., 2021). Besides, studies also show that DPP‐4 inhibitors are proved safe in post COVID‐19 infections of patients with diabetes, and some say they also reduce mortality (Nauck & Meier, 2020; Roussel et al., 2021). That is why, it was selected for antidiabetic target. On the other hand, pulmonary fibrosis and impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities in post COVID‐19 patients is dominant due to the prevalence of respiratory failure, as well as use of noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation and high‐flow nasal cannula (Ambardar et al., 2021). Viral pneumonia and pneumonitis (Lechowicz et al., 2020; Ojo et al., 2020), COVID‐19 related sepsis (Lechowicz et al., 2020), thromboembolism, and hyperoxia and dysregulation of immune response are thought to be the pathological causes of post COVID‐19 respiratory complications. However, studies showed that TGF‐β‐1(PDB ID: 6B8Y) upregulation has a potential role in this process of pathogenesis (Khalil et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2020). So, this was selected for respiratory tract target of post COVID‐19 infection.

3.3.2. Protein preparation and molecular docking

Proteins were prepared using Discovery studio and SwissPdb viewer (Guex et al., 2009). At first, all water molecules and ligands were discarded from the complex proteins. Subsequently, molecular docking study was conducted using the virtual screening tool PyRx (https://pyrx.sourceforge.io/).

3.4. Bioinformatics‐based network pharmacology

3.4.1. Bioactive compound—Target protein network construction

On the account of network pharmacology–based prediction, STITCH 5 (http://stitch.embl.de/, ver. 5.0) was used to identify the target proteins related to bioactive compounds, which were identified from functional foods. It was used to calculate the score for each pair of protein–chemical interactions. Bioactive compounds were inputted into STITCH 5 together to match their potential targets, selecting the organism, Homo sapiens and medium required interaction score being ≥0.4. We have also used (Guex et al., 2009). SwissTargetPrediction to perform a combination of similarity measurements based on known 2D and 3D chemical structures to predict the corresponding potential bioactive targets (probability >0.1, http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) (Gfeller et al., 2014). The online tool “Calculate and draw custom Venn diagrams” (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) was used to identify common genes between the target genes of STITCH and the SwissTargetPrediction.

3.4.2. Construction of protein–protein interaction network of the predicted genes

We constructed a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the predicted genes by search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes (STRING) database (https://string‐db.org/cgi/input.pl; STRING‐DB v11.0) (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). Cytoscape plugin cytoHubba (Chin et al., 2014) was used to identify the rank of the target proteins based on degree of interactions in the PPI network. The obtained protein interaction data of target proteins were imported into Cytoscape 3.6.1 software to construct a PPI network (Shannon et al., 2003).

3.4.3. Gene ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses of the target proteins

The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to identify the role of target proteins that interact with the active ingredient sample in gene function and signaling pathway. The KEGG (Kanehisa et al., 2017) pathways significantly associated with the predicted genes were identified. We analyzed the GO function and KEGG pathway enrichment of 159 common target proteins. The target proteins involved in the cellular components (CCs), molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and the KEGG pathways were also described. The FDR value <0.05, calculated by the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995), was considered as significant.

3.5. Redocking of the target compounds

Among the best genes selected from network pharmacology study, some targets were selected, which were related to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and respiratory disorders. These targets were prepared the same way as explained in the Sections 3.3.1 and 3.3.2 followed by molecular docking analysis. After docking, 3D and 2D complexes were visualized in the protein plus web server (https://proteins.plus).

4. RESULTS

4.1. ADME and pharmacokinetic properties

In total, 139 compounds passed our criteria selected for ADME study and pharmacokinetic properties (Table 1). As the food will be directly consumed, they should be properly absorbed in the GI tract. Hence, compounds with high GI absorption rate were selected. Bioavailability is also important to know if the compounds are present in systemic circulation or not. Compounds with a bioavailability of greater than 0.55 were chosen as candidates. Solubility is important to ensure the distribution of the constituents via the systemic circulations into the target tissues and the compounds having high to moderate solubility were selected. Molecular weight, number of H‐bond donor, and H‐bond acceptor are the structural parameters, which were in acceptable limits.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, structural parameters, Lipinski rule violation number, and solubility prediction of selected bioactive compounds

| Bioactive compounds | Functional food | GI absorption | No. of Lipinski violations | Bioavailability score | #H‐bond acceptors | #H‐bond donors | Molecular weight | ESOL class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic acid | Bitter melon | High | 0 | 0.56 | 4 | 3 | 180.16 | Very soluble |

| Gallic acid | Bitter melon | High | 0 | 0.56 | 5 | 4 | 170.12 | Very soluble |

| Gentisic acid | Bitter melon | High | 0 | 0.56 | 4 | 3 | 154.12 | Soluble |

| Catechin | Bitter melon | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 5 | 290.27 | Soluble |

| Epicatechin | Bitter melon | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 5 | 290.27 | Soluble |

| Nigellicine | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.85 | 3 | 1 | 246.26 | Soluble |

| Dihomo linoleic acid | Black cumin | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 280.45 | Moderately soluble |

| Eicosadienoic acid | Black cumin | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 308.5 | Moderately soluble |

| Linoleic acid | Black cumin | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 280.45 | Moderately soluble |

| Oleic acid | Black cumin | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 282.46 | Moderately soluble |

| Carvacrol | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 150.22 | Soluble |

| Dithymoquinone | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 0 | 328.4 | Soluble |

| Nigellidine | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 294.35 | Soluble |

| Nigellone | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 0 | 328.4 | Soluble |

| t‐Anethole (1%–4%) | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 148.2 | Soluble |

| Thymol | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 150.22 | Soluble |

| Thymoquinone (TQ) (30%–48%), | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 164.2 | Soluble |

| Thymohydroquinone | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 2 | 166.22 | Soluble |

| 4‐Terpineol (2%–7%) | Black cumin | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Apigenin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 3 | 270.24 | Soluble |

| Ethanolamine | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 2 | 61.08 | Highly soluble |

| Eugenol | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 164.2 | Soluble |

| Gingerol | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 294.39 | Soluble |

| Hymecromone | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 176.17 | Soluble |

| Luteolin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 4 | 286.24 | Soluble |

| Medicarpin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 1 | 270.28 | Soluble |

| Naringenin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 3 | 272.25 | Soluble |

| Quercetin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 7 | 5 | 302.24 | Soluble |

| Scopoletin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 1 | 192.17 | Soluble |

| Tricin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 7 | 3 | 330.29 | Moderately soluble |

| Trigonelline | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 137.14 | Very soluble |

| Vanillin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 152.15 | Very soluble |

| Zingerone | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 194.23 | Very soluble |

| γ‐Schizandrin | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 0 | 400.46 | Moderately soluble |

| (2S, 3R, 4S)‐4‐hydroxyisoleucine | Fenugreek | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 3 | 147.17 | Highly soluble |

| Diosgenin | Fenugreek | High | 1 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 414.62 | Moderately soluble |

| Yamogenin | Fenugreek | High | 1 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 414.62 | Moderately soluble |

| Octadecanoic acid (18:0, stearic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 284.48 | Moderately soluble |

| cis‐9‐hexadecenoic acid (16:1 (n‐7), palmitoleic acid) | Fish oil | High | 0 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 254.41 | Moderately soluble |

| Hexadecadienoic acid (16:2) | Fish oil | High | 0 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 252.39 | Moderately soluble |

| Hexadecatrienoic acid (16:3) | Fish oil | High | 0 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 250.38 | Moderately soluble |

| Pentadecanoic acid (15:0) | Fish oil | High | 0 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 242.4 | Moderately soluble |

| ‐Tetradecanoic acid (14:0, myristic acid) | Fish oil | High | 0 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 228.37 | Moderately soluble |

| ‐cis‐9‐ octadecenoic acid (18:1 (n‐9), oleic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 282.46 | Moderately soluble |

| cis−11‐octadecenoic acid (18:l (n−7), asclepic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 282.46 | Moderately soluble |

| ‐cis‐9,12‐octadecadienoic acid (18:2 (n‐6), linoleic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 280.45 | Moderately soluble |

| cis‐9,12,15‐octadecatrienoic acid (18:3 (n‐3), a‐linolenic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 278.43 | Moderately soluble |

| ‐cis‐6,9,12,15‐octadecatetraenoic acid (18:4 (n‐3), moroctic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 0 | 275.41 | Moderately soluble |

| cis‐5,8,11,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid (20:4 (n‐6), arachidonic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 304.47 | Moderately soluble |

| cis‐8,11,14,17‐eicosatetraenoic acid (20:4 (n‐3)) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 304.47 | Moderately soluble |

| DHA (22:6n‐3) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 328.49 | Moderately soluble |

| EPA (20:5n‐3) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 302.45 | Moderately soluble |

| Heptadecanoic (17:O) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 270.45 | Moderately soluble |

| Hexadecanoic acid (16:0, palmitic acid) | Fish oil | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 256.42 | Moderately soluble |

| S‐methyl‐L‐cysteine sulfoxide | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 151.18 | Highly soluble |

| DAS, diallyl sulfide | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 114.21 | Very soluble |

| Diallyldisulfide DADS | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 146.27 | Very soluble |

| SAC S‐allylcysteine | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 161.22 | Highly soluble |

| S‐ethylcysteine SEC | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 149.21 | Highly soluble |

| S‐methylcysteine SMC | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 135.18 | Highly soluble |

| S‐propylcysteine | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 163.24 | Highly soluble |

| Allyl propyl sulfide | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 116.22 | Very soluble |

| SAC S‐allylcysteine sulfoxide | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 177.22 | Highly soluble |

| Allicin | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 177.22 | Highly soluble |

| Ajoene | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 234.4 | Very soluble |

| Diallyl tetrasulfide | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 210.4 | Soluble |

| Diallyl thiosulfinate | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 162.27 | Very soluble |

| Quercetin | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 7 | 5 | 302.24 | Soluble |

| Apigenin | Garlic | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 3 | 270.24 | Soluble |

| Geranyl acetate | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 196.29 | Soluble |

| 6‐Dehydrogingerdione | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.85 | 4 | 2 | 290.35 | Moderately soluble |

| Alpha‐eudesmol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 222.37 | Soluble |

| Citral | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 152.23 | Soluble |

| Endo‐borneol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Eucalyptol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Geraniol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Gingerenone‐A | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 2 | 356.41 | Moderately soluble |

| 6‐Gingerol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 294.39 | Soluble |

| 8‐Gingerol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 322.44 | Soluble |

| 10‐Gingerol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 350.49 | Moderately soluble |

| Nerolidol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 222.37 | Soluble |

| Paradol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 278.39 | Soluble |

| Quercetin | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 7 | 5 | 302.24 | Soluble |

| 6‐Shogaol | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 276.37 | Soluble |

| Zingerone | Ginger | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 1 | 194.23 | Very soluble |

| Catechin | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 5 | 290.27 | Soluble |

| Gallic acid | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 4 | 170.12 | Very soluble |

| Kaempferol | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 4 | 286.24 | Soluble |

| Luteolin | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 4 | 286.24 | Soluble |

| Madasiatic acid | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 4 | 488.7 | Moderately soluble |

| Madecassic acid | Indian pennywort | High | 1 | 0.55 | 6 | 5 | 504.7 | Moderately soluble |

| Pinene | Indian pennywort | High | 0 | 0.55 | 0 | 0 | 136.23 | Soluble |

| n‐Hexadecanoic acid | Peppermint | High | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 1 | 256.42 | Moderately soluble |

| Bornyl acetate | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 196.29 | Soluble |

| Carvacrol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 150.22 | Soluble |

| Caryophyllene oxide | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 220.35 | Soluble |

| Eucalyptol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Iso‐amyl isovalerate | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 172.26 | Soluble |

| Isopulegol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Ledene oxide‐(II) | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 220.35 | Soluble |

| Linalool | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Menthofuran | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 150.22 | Soluble |

| Menthol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 156.27 | Soluble |

| Menthone | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Menthyl acetate | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 198.3 | Soluble |

| Methyleugenol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 178.23 | Soluble |

| Neoisomenthyl acetate | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 198.3 | Soluble |

| Neo‐menthol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 156.27 | Soluble |

| p‐Menth‐1‐en‐3‐one (piperidone) | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 152.23 | Soluble |

| Pulegone | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 152.23 | Soluble |

| Spathulenol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 220.35 | Soluble |

| Thymol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 150.22 | Soluble |

| Trans‐sabinene hydrate | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| Viridiflorol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 222.37 | Soluble |

| 1,8‐Cineole | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 154.25 | Soluble |

| 3‐Octanol | Peppermint | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 130.23 | Soluble |

| Ar‐turmerone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 216.32 | Soluble |

| ‐α‐Turmerone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 218.33 | Soluble |

| Bisdemethoxycurcumin | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 4 | 2 | 308.33 | Soluble |

| Bisabola 3, 10‐diene 2‐one | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 220.35 | Soluble |

| Bisacumol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 1 | 218.33 | Soluble |

| Bisacurone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 252.35 | Soluble |

| β‐Turmerone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 218.33 | Soluble |

| 1, 7‐bis (4‐hydroxyphenyl)‐1, 4, 6‐heptatriene‐3‐one | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 292.33 | Moderately soluble |

| Curcumin | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 2 | 368.38 | Soluble |

| Curcumenone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Curcumenol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Curcumadiol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 2 | 238.37 | Soluble |

| Demethoxycurcumin | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 5 | 2 | 338.35 | Soluble |

| Dehydrocurdione | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Epiprocurcumenol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Germacrone‐13‐al | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 232.32 | Soluble |

| 1‐(4‐ hydroxyl‐3, 5‐dimethoxyphenyl)‐7‐(4‐ hydroxyl‐3‐methoxyphenyl)‐(1E, 6E)‐1, 6‐ heptadiene‐3, 4‐dione | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 7 | 2 | 398.41 | Soluble |

| PC261‐1‐(4‐hydroxy‐3‐methoxyphenyl)‐7‐(3, 4‐dihydroxyphenyl)‐1, 6‐heptadiene‐3, 5‐dione | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 3 | 354.35 | Soluble |

| Isoprocurcumenol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Phenylbutazone | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 0 | 308.37 | Soluble |

| Procurcumenol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 234.33 | Soluble |

| Procurcumadiol | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 3 | 2 | 250.33 | Soluble |

| Tetrahydrocurcumin | Turmeric | High | 0 | 0.55 | 6 | 2 | 372.41 | Soluble |

4.2. Primary virtual screening via molecular docking for network pharmacology study

From the primary screening of compounds for network pharmacology studies, we got 71 compounds that showed good binding affinity of “−7” or better for the respective target proteins that were carried forward for reconfirmation via network pharmacology studies (Table 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Binding affinity of compounds with primary targets in different diseases

| Respiratory disorders | Diabetes | Cardiovascular diseases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transforming growth factor beta (TGF‐β1) (PDB ID:6B8Y) | Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 DPP‐4(PDB:6B1E) | Troponin I interacting kinase TNNI3K (4YFI) | |||

| Compound name | Binding affinity | Compound name | Binding affinity | Compound name | Binding affinity |

| Luteolin | −9.7 | Protodioscin | −10.4 | Quercetin glycoside | −13 |

| Quercetin glycoside | −9.7 | Quercetin glycoside | −10.1 | Stigmasterol | −11.2 |

| Tricin | −9.7 | Yamogenin | −9.4 | Nigellicimine | −11 |

| Protodioscin | −9.6 | Diosgenin | −9.3 | diosgenin | −10.9 |

| Apigenin | −9.5 | Madasiatic acid | −9.2 | Dithymoquinone | −10.2 |

| Nigellidine | −9.4 | Stigmasterol | −9 | Nigellone | −10.2 |

| Stigmasterol | −9.4 | Luteolin | −8.8 | Quercetin | −9.9 |

| Naringenin | −9.4 | Asiatic acid | −8.7 | Asiatic acid | −9.8 |

| Quercetin | −9.3 | Quercetin | −8.7 | Luteolin | −9.8 |

| Laricytrin | −9.3 | Madecassic acid | −8.5 | Catechin | −9.7 |

| Quercetin | −9.3 | Catechin | −8.3 | Madecassic acid | −9.6 |

| Kaempferol | −9.2 | Apigenin | −8.1 | Nigellidine | −9.5 |

| Procurcumenol | −9.2 | ‐1‐(4‐ hydroxyl‐3, 5‐dimethoxyphenyl)‐7‐(4‐ hydroxyl‐3‐methoxyphenyl) ‐(1E, 6E)‐1, 6‐ heptadiene‐3, 4‐dione | −8.1 | Medicarpin | −9.5 |

| Nigellone | −9.1 | Curcumin | −8 | Kaempferol | −9.4 |

| Catechin | −9.1 | Procurcumenol | −8 | Gallic acid | −9.4 |

| Zingerone | −9.1 | Nigellidine | −7.9 | Madasiatic acid | −9.3 |

| Diosgenin | −9 | Tricin | −7.9 | Sitosterol | −9.2 |

| Yamogenin | −9 | Dithymoquinone | −7.8 | Naringenin | −9.2 |

| Catechin and epicatechin | −8.9 | Nigellone | −7.8 | Protodioscin | −9.2 |

| Zedoaronediol | −8.7 | Medicarpin | −7.8 | Apigenin | −9.2 |

| Hymecromone | −8.5 | Laricytrin | −7.7 | Isopulegol | −9.1 |

| Scopoletin | −8.5 | Epiprocurcumenol | −7.7 | Procurcumenol | −9.1 |

| Medicarpin | −8.4 | Isoprocurcumenol | −7.7 | 1‐hydroxy‐1, 7‐bis (4‐hydroxy‐3‐) | −9 |

| Dehydrocurdione | −8.3 | Triethyl curcumin | −7.7 | Laricytrin | −8.9 |

| ‐1‐(4‐hydroxy‐3‐methoxyphenyl)‐7‐ (3, 4‐dihydroxyphenyl)‐1, 6‐heptadiene‐3, 5‐dione | −8.3 | Kaempferol | −7.6 | Catechin and epicatechin | −8.9 |

| Madasiatic acid | −8.1 | Catechin and epicatechin | −7.6 | Caffeic acid | −8.8 |

| Gingerenone‐A | −8.1 | Gallic acid | −7.6 | Zedoaronediol | −8.7 |

| Curcumadiol | −8.1 | 4‐methoxy5‐hydroxybisabola‐2, 10‐diene‐9‐one | −7.6 | Tricin | −8.6 |

| Nigellicine | −8 | Naringenin | −7.5 | ‐1‐(4‐hydroxy‐3‐methoxyphenyl)‐7‐ (3, 4‐dihydroxyphenyl)‐1, 6‐heptadiene‐3, 5‐dione | −8.6 |

| Curcumin | −8 | Alpha‐Eudesmol | −7.5 | 4, 5‐ dihydrobisabola‐2, 10‐diene | −8.5 |

| Triethyl curcumin | −8 | β‐Pinene | −7.5 | Epiprocurcumenol | −8.5 |

| Isoprocurcumenol | −7.9 | Dehydrocurdione | −7.5 | Germacrone‐13‐al | −8.5 |

| Asiatic acid | −7.8 | Germacrone‐13‐al | −7.5 | Triethyl curcumin | −8.5 |

| Germacrene D | −7.8 | Germacrene D | −7.4 | Nigellicine | −8.4 |

| Demethoxycurcumin | −7.8 | Methyleugenol | −7.4 | Germacrene D | −8.4 |

| −7.8 | Isopulegol | −7.3 | Alpha‐Eudesmol | −8.4 | |

| Madecassic acid | −7.7 | −7.3 | Curcumin | −8.4 | |

| β‐Pinene | −7.7 | (4 S, 5 S)‐Germacrone 4, 5‐epoxide | −7.2 | Isoprocurcumenol | −8.3 |

| Curcumenol | −7.7 | (methoxyphenyl)‐(6E)‐6‐heptene‐3, 5‐dione | −7.2 | Methyleugenol | −8.1 |

| 4, 5‐ dihydrobisabola‐2, 10‐diene | −7.7 | Zedoaronediol | −7.2 | γ‐Schizandrin | −8 |

| 4‐terpineol (2%–7%) | −7.6 | γ‐Schizandrin | −7.1 | (4 S, 5 S)‐Germacrone 4, 5‐Epoxide | −7.9 |

| Alpha‐Eudesmol | −7.6 | 4, 5‐ dihydrobisabola‐2, 10‐diene | −7 | β‐Pinene | −7.8 |

| 6‐Shogaol | −7.6 | Dehydrocurdione | −7.8 | ||

| Isopulegol | −7.6 | 4‐Methoxy5‐hydroxybisabola‐2, 10‐diene‐9‐one | −7.8 | ||

| Methyleugenol | −7.6 | β‐turmerone | −7.7 | ||

| Germacrone‐13‐al | −7.6 | Curcumenone | −7.7 | ||

| (methoxyphenyl)‐(6E)‐6‐heptene‐3, 5‐dione | −7.6 | Curcumadiol | −7.7 | ||

| Gingerol | −7.5 | Demethoxycurcumin | −7.7 | ||

| Curcumenone | −7.5 | Hymecromone | −7.6 | ||

| Paradol | −7.4 | 6‐Dehydrogingerdione | −7.5 | ||

| 2, 5‐dihydroxy bisabola‐3, 10‐diene | −7.4 | −7.5 | |||

| (4 S, 5 S)‐germacrone 4, 5‐epoxide | −7.4 | Scopoletin | −7.4 | ||

| −7.4 | Gingerenone‐A | −7.4 | |||

| Thymoquinone (TQ) (30%–48%) | −7.3 | Curcumenol | −7.4 | ||

| Germacrene‐D | −7.3 | 2, 5‐Dihydroxy bisabola‐3, 10‐diene | −7.4 | ||

| β‐turmerone | −7.3 | DHA | −7.3 | ||

| Dithymoquinone | −7.2 | Gingerol | −7.2 | ||

| 6‐Dehydrogingerdione | −7.2 | EPA (20:5n‐3) | −7.1 | ||

| Epiprocurcumenol | −7.2 | Nerolidol | −7 | ||

| ‐cis‐6,9,12,15‐octadecatetraenoic acid (18:4 (n‐3), moroctic acid) | −7.1 | ||||

| 6‐Gingerol | −7.1 | ||||

| Menthyl acetate | −7.1 | ||||

| Elemene | −7 | ||||

| Gentisic acid | −7 | ||||

TABLE 3.

Selected compounds after primary screening via molecular docking

| SL No. | SL No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isoprocurcumenol | 38 | DHA |

| 2 | (4 S, 5 S)‐Germacrone 4, 5‐epoxide | 39 | Diosgenin |

| 3 | ‐1‐(4‐Hydroxy‐3, 5‐dimethoxyphenyl)‐7‐(4‐Hydroxy‐3‐methoxyphenyl)‐(1E, 6E)‐1, 6‐ heptadiene‐3, 4‐dione; | 40 | Dithymoquinone |

| 4 | 2, 5‐Dihydroxybisabola‐3, 10‐diene | 41 | Elemene |

| 5 | 4, 5‐Dihydrobisabola‐2, 10‐diene | 42 | EPA (20:5n‐3) |

| 6 | 4‐Methoxy5‐hydroxybisabola‐2, 10‐diene‐9‐one | 43 | Germacrene D |

| 7 | Catechin | 44 | Gingerenone‐A |

| 8 | Curcumadiol | 45 | Gingerol |

| 9 | Curcumenol | 46 | Hymecromone |

| 10 | Curcumenone | 47 | Kaempferol |

| 11 | Curcumin | 48 | Laricytrin |

| 12 | Dehydrocurdione | 49 | Luteolin |

| 13 | Demethoxycurcumin | 50 | Madasiatic acid |

| 14 | Epiprocurcumenol | 51 | Madecassic acid |

| 15 | Gallic acid | 52 | Medicarpin |

| 16 | Gentisic acid | 53 | methoxyphenyl‐(6E)‐6‐heptene‐3, 5‐dione |

| 17 | Germacrene D | 54 | Naringenin |

| 18 | Germacrone‐13‐al | 55 | Nerolidol |

| 19 | Isopulegol | 56 | Nigellicimine |

| 20 | Menthyl acetate | 57 | Nigellicine |

| 21 | Methyleugenol | 58 | Nigellidine |

| 22 | Procurcumenol | 59 | Nigellone |

| 23 | Triethyl curcumin | 60 | Paradol |

| 24 | Zedoaronediol | 61 | Protodioscin |

| 25 | β‐Pinene | 62 | Quercetin |

| 26 | βturmerone | 63 | Quercetin glycoside |

| 27 | 1‐Hydroxy‐1, 7‐bis (4‐hydroxy‐3‐) | 64 | Scopoletin |

| 28 | 4‐Terpineol (2%–7%) | 65 | Sitosterol |

| 29 | 6‐Dehydrogingerdione | 66 | Stigmasterol |

| 30 | 6‐Gingerol | 67 | Thymoquinone (TQ) (30%–48%) |

| 31 | 6‐Shogaol | 68 | Tricin |

| 32 | Alpha‐Eudesmol | 69 | Yamogenin |

| 33 | Apigenin | 70 | Zingerone |

| 34 | Asiatic acid | 71 | γ‐Schizandrin |

| 35 | Caffeic acid | ||

| 36 | Epicatechin | ||

| 37 | ‐cis‐6,9,12,15‐octadecatetraenoic acid (18:4 (n‐3), moroctic acid) |

4.3. Network pharmacology

4.3.1. Identification of target proteins

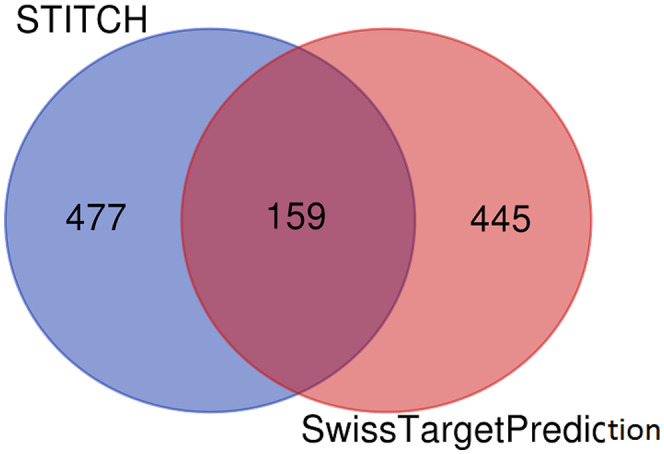

We identified 636 target proteins (Table S1) using STITCH and 604 target proteins (Table S2) using SwissTargetPrediction. After overlapping by the Venn tool, we got 159 common target proteins (Figure 1), and 159 target proteins are tabulated in Table S3.

FIGURE 1.

Overlapping 159 target proteins identified by STITCH and SwissTargetPrediction

4.3.2. Construction, analysis of target proteins’ protein–protein interaction network, and identification of hub nodes

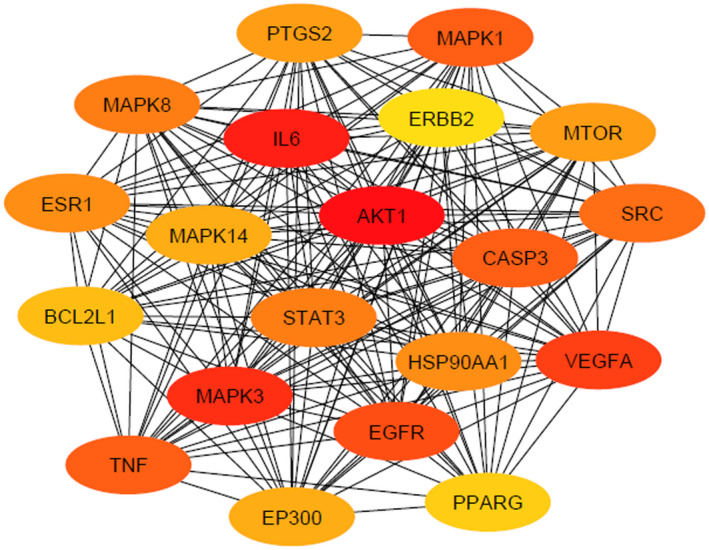

Common target proteins were set to STRING‐DB v11.0 for the construction of PPI. We found that 159 target proteins are involved in PPI (except STK17B). Then the interaction of STRING was inputted in 3.6.1 software to construct a PPI network. The top 20 hub nodes based on the maximum degree of interaction are displayed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Protein–protein interaction network of top 20 target proteins. In the constructed network, colorful nodes represent the target genes, whereas the connections between the nodes represent the interactions between these biological analyses

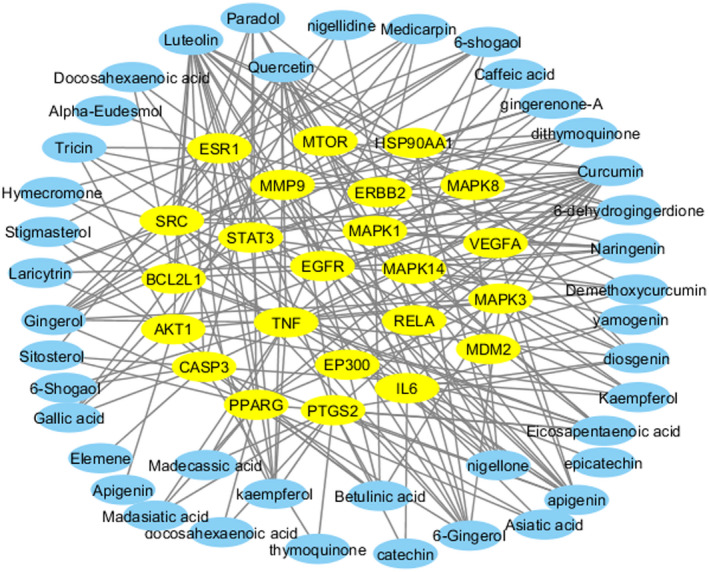

Additionally, we identified the rank of interacted target proteins by applying Cytoscape plugin cytoHubba as shown in Figure 3 (Chin et al., 2014). Most interaction degrees indicate the potential biological functions. The rank of the top 23 target proteins on the basis of the degree of interaction is shown in Table 4 (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). All the target proteins are tabulated in Table S3. AKT1, with 99 degrees of interaction, was placed in the top position. Then the interaction of STRING was put into 3.6.1 software to construct a PPI network.

FIGURE 3.

Protein–protein interaction network of top 23 target genes with interacting compounds. In the constructed network, yellow nodes represent the target genes and blue nodes represent the compounds, whereas the connections between the nodes represent the interactions between these biological analyses

TABLE 4.

Top 23 hub nodes identified based on degree of interactions

| Rank | Name of target genes | Degree of interactions | Interacting compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AKT1 | 99 | Apigenin, betulinic acid, curcumin, kaempferol, luteolin, quercetin, gallic acid, demethoxycurcumin, laricytrin, nigellidine, tricin |

| 2 | IL6 | 91 | Catechin, curcumin, epicatechin, quercetin, Asiatic acid, diosgenin, yamogenin |

| 3 | MAPK3 | 87 | Apigenin, betulinic acid, curcumin, kaempferol, quercetin, gingerol, 6‐gingerol |

| 4 | VEGFA | 86 | Apigenin, curcumin, diosgenin, quercetin, naringenin |

| 5 | EGFR | 83 | 6‐Dehydrogingerdione, apigenin, curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, hymecromone, kaempferol, laricytrin, luteolin, quercetin, tricin, betulinic acid |

| 6 | CASP3 | 82 | Gallic acid, sitosterol, thymoquinone, quercetin, luteolin, kaempferol elemene, curcumin, betulinic acid, apigenin, 6‐shogaol, medicarpin |

| 7 | MAPK1 | 82 | Medicarpin, nigellone, eicosapentaenoic acid, dithymoquinone, diosgenin, 6‐shogaol, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, apigenin, betulinic acid, curcumin, kaempferol, luteolin, naringenin, quercetin, caffeic acid |

| 8 | TNF | 82 | 6‐Gingerol, 6‐shogaol, apigenin, curcumin, diosgenin, gingerol, hymecromone, kaempferol, luteolin, medicarpin, naringenin, quercetin, stigmasterol, eicosapentaenoic acid, demethoxycurcumin, gingerenone‐A, madasiatic acid, madecassic acid |

| 9 | SRC | 78 | 6‐Dehydrogingerdione, 6‐gingerol, 6‐shogaol, apigenin, dithymoquinone, gingerol, kaempferol, laricytrin, luteolin, medicarpin, naringenin, nigellone, paradol, quercetin, tricin |

| 10 | STAT3 | 73 | Curcumin, kaempferol, luteolin, demethoxycurcumin, dithymoquinone, docosahexaenoic acid, nigellone, paradol |

| 11 | MAPK8 | 73 | Dithymoquinone, curcumin, diosgenin, luteolin, quercetin, caffeic acid |

| 12 | HSP90AA1 | 70 | Luteolin, curcumin, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, 6‐gingerol, dithymoquinone, gingerenone‐A, gingerol, nigellone, paradol |

| 13 | ESR1 | 70 | Apigenin, kaempferol, quercetin, 6‐gingerol, 6‐shogaol, alpha‐eudesmol, gingerol, hymecromone, kaempferol, luteolin, medicarpin, naringenin, nigellidine, paradol, sitosterol, stigmasterol, tricin |

| 14 | PTGS2 | 68 | Apigenin, catechin, curcumin, diosgenin, quercetin, thymoquinone, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, asiatic acid, betulinic acid, kaempferol, luteolin, madecassic acid, madasiatic acid |

| 15 | MTOR | 68 | Curcumin, luteolin, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, 6‐gingerol, 6‐shogaol, demethoxycurcumin, gingerol, medicarpin, paradol |

| 16 | EP300 | 62 | Curcumin, eicosapentaenoic acid, demethoxycurcumin |

| 17 | MAPK14 | 62 | Naringenin, quercetin, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, 6‐shogaol, diosgenin, eicosapentaenoic acid, yamogenin |

| 18 | BCL2L1 | 59 | Curcumin, luteolin, gallic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, naringenin |

| 19 | PPARG | 58 | Curcumin, luteolin, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, 6‐gingerol, Asiatic acid, betulinic acid, dithymoquinone, gingerol, madasiatic acid, naringenin, madecassic acid, paradol, sitosterol, stigmasterol |

| 20 | ERBB2 | 57 | Curcumin, luteolin, 6‐gingerol, gingerenone‐A, gingerol, nigellidine |

| 21 | RELA | 56 | Curcumin, paradol |

| 22 | MMP9 | 55 | 6‐Gingerol, apigenin, curcumin, gingerol, luteolin, quercetin, caffeic acid, gallic acid, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, 6‐shogaol, apigenin, dithymoquinone, docosahexaenoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, gingerenone‐A, kaempferol, laricytrin, nigellone, tricin |

| 23 | MDM2 | 53 | Curcumin, yamogenin |

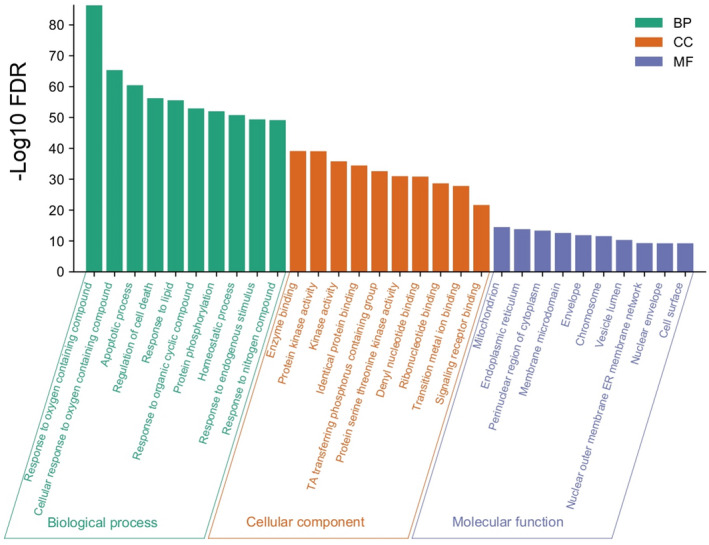

4.3.3. Gene Ontology analysis of interacted target proteins

GO enrichment analysis of interacted target proteins (total 159) that interact with compounds was performed by GSEA. The 159 target proteins were incorporated into the GSEA and selected humans. A wide variety of BPs (Table S4), MFs (Table S5), and CCs (Table S6) were identified. The top 10 BPs, MFs, and CC are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Top 10 biological process, molecular function, and cellular connection associated with target proteins

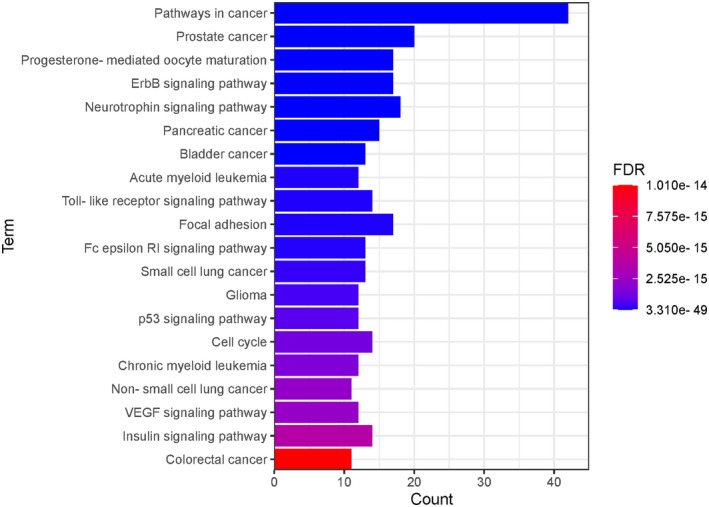

4.3.4. Target proteins’ set enrichment analysis of KEGG pathway

To further elucidate the relationship between the target proteins and the pathways, we identified 97 KEGG pathways (Table S7) that were significantly associated with the target proteins. These pathways were mainly involved in cancer, respiratory diseases, diabetes, immune regulation, metabolisms, and other cellular and developmental signaling pathways as shown in Figure 5. These results indicate that these compounds may be associated with the enrichment of these pathways.

FIGURE 5.

Top 20 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways associated with target proteins

4.4. Redocking of the target compounds

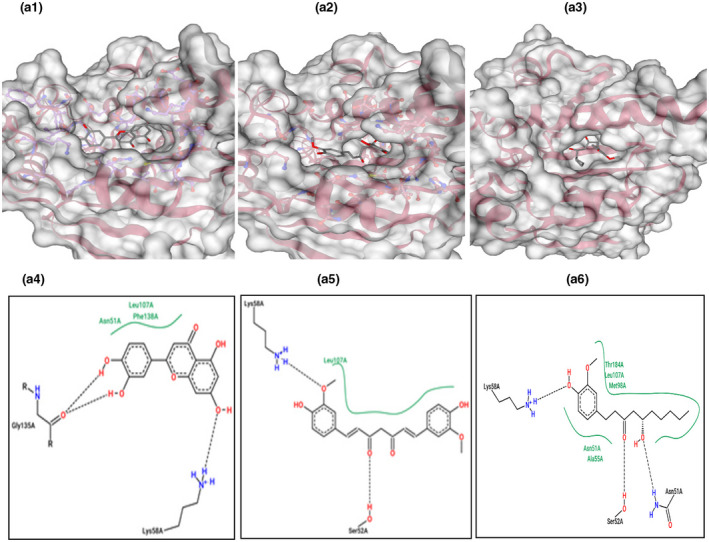

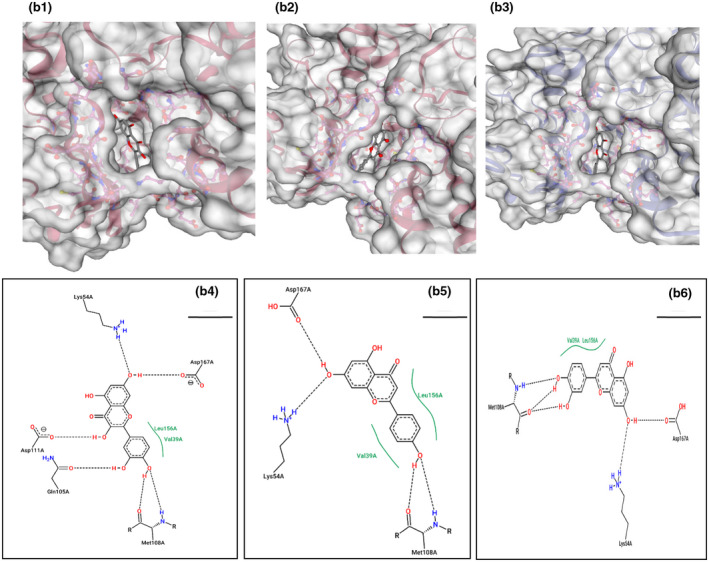

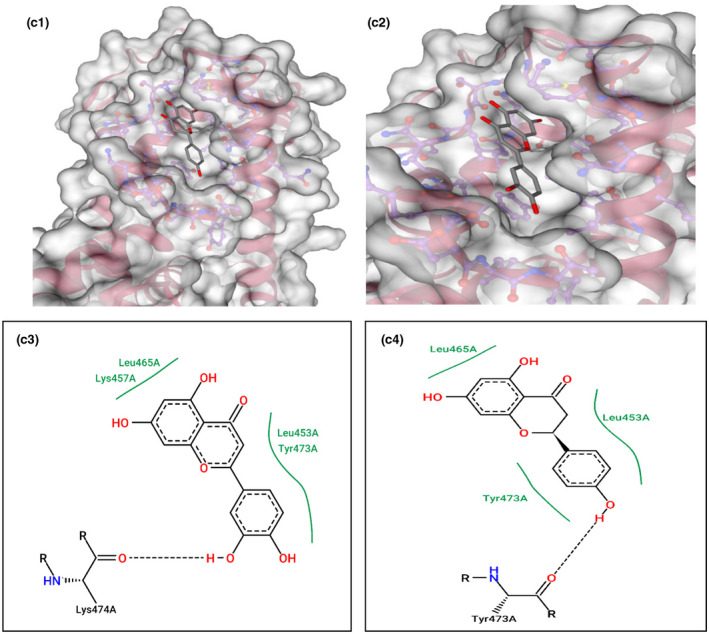

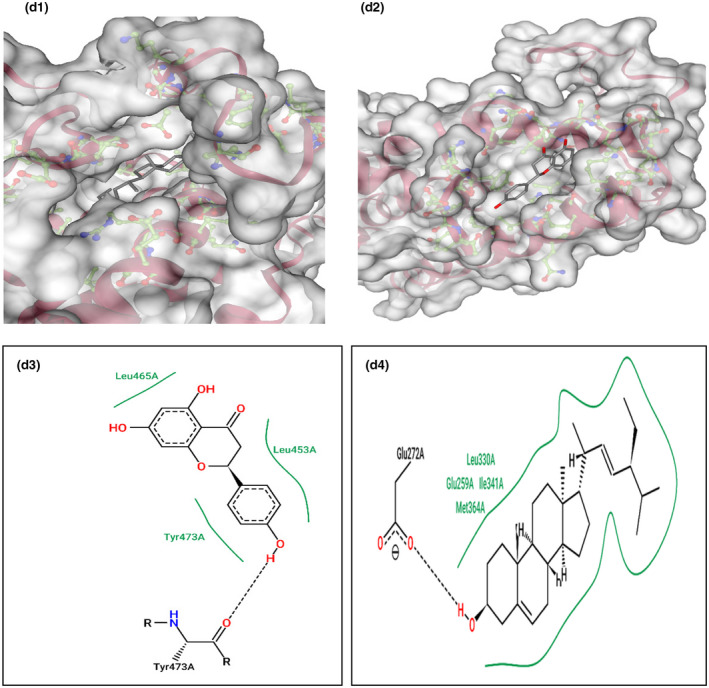

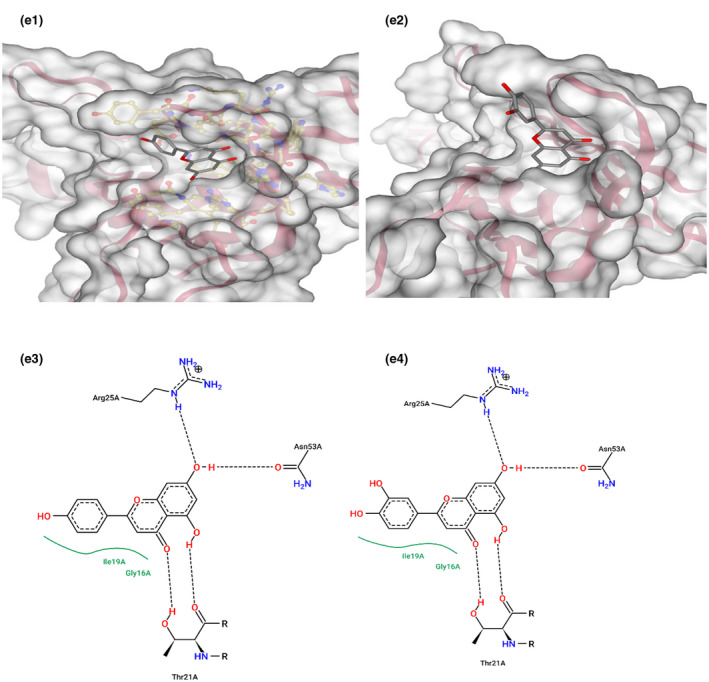

We selected the best five targets that interacted with a good number of compounds and were strongly associated with the disease pathogenesis and have a good degree of interactions. MAPK‐1, HSP90AA1, AKT1, PPARG, and TNF‐alpha are the targets, and the compounds that showed interaction in network pharmacology study were subjected to molecular docking to analyze their binding affinity. For cardiovascular complications, HSP90AA1 (PDB ID: 1BYQ) and MAPK1 (PDB ID: 2Y9Q) were chosen, whereas for diabetes PPARG (PDB ID: 1ZGY) and TNF‐alpha (PDB ID: 5M3J) and for respiratory disorders AKT‐1(PDB ID: 1UNP) were selected.

4.4.1. Genes associated with cardiovascular diseases

Heat shock protein (HSP90AA1) gene

This gene is related to cardiovascular diseases. The interacting compounds were luteolin, curcumin, 6‐dehydrogingerdione, 6‐gingerol, dithymoquinone, gingerenone‐A, gingerol, nigellone, paradol. luteolin, and curcumin that proved to be the best compounds from docking results (Table 5).

TABLE 5.