Abstract

Viruses are infectious agents that pose significant threats to plants, animals, and humans. The current coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has spread globally and resulted in over 2 million deaths and immeasurable financial losses. Rapid and sensitive virus diagnostics become crucially important in controlling the spread of a pandemic before effective treatment and vaccines are available. Gold nanoparticle (AuNP)‐based testing holds great potential for this urgent unmet biomedical need. In this review, we describe the most recent advances in AuNP‐based viral detection applications. In addition, we discuss considerations for the design of AuNP‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 testings. Finally, we highlight and propose important parameters to consider for the future development of effective AuNP‐based testings that would be critical for not only this COVID‐19 pandemic, but also potential future outbreaks.

This article is categorized under:

Diagnostic Tools > Biosensing

Diagnostic Tools > In Vitro Nanoparticle‐Based Sensing

Keywords: COVID‐19, electrochemical detection, fluorescence resonance energy transfer, gold nanoparticle, in vitro diagnostics, lateral flow assay, microfluidic, point‐of‐care, surface plasmon resonance

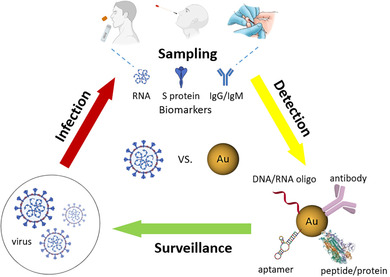

Multifunctional gold nanoparticles enable rapid and effective SARS‐CoV‐2 testing and can be employed for the surveillance and control of COVID‐19 spread.

1. INTRODUCTION

A virus is an insidious pathogen and one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although the global death toll caused by viral infection is less than that caused by cardiovascular diseases or cancers (Ritchie & Roser, 2020), the impact of virus infection on patients and even healthy individuals is much more significant than the number of deaths can tell. Importantly, viruses have been the only cause of major pandemics since the 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic (CDC website. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/basics/past-pandemics.html). The main reasons behind this are manifold, including the virus's highly contagious nature, evolving capability, and the absence of efficient diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. Currently, the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has spread to over 210 countries and territories, leaving over 100 million people infected, over 2 million people dead and millions jobless (Johns Hopkins website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu; United Nations website. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061322).

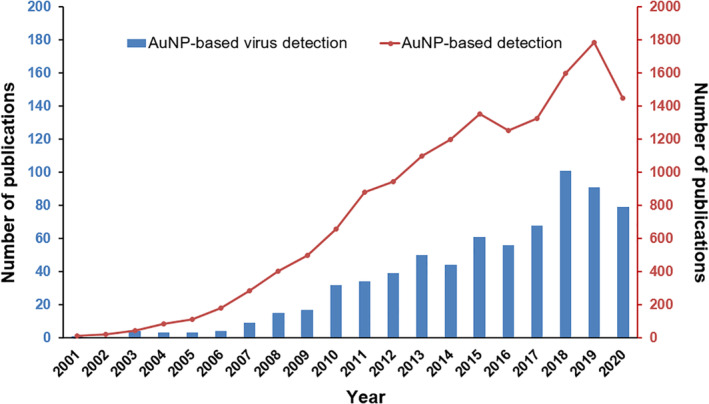

Rapid and accurate viral detection is critical for infectious status assessment, decision making, and subsequent control of viral dissemination. For such application, highly sensitive and reliable diagnosis tools, such as in vitro diagnostic devices (IVDs), are required and are of great scientific and clinical interest due to their ease of use, low cost, and high throughput. Among IVDs, gold nanoparticle (AuNP)‐based IVDs represent a promising approach because of the unique physical and optical properties of AuNPs, including localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), surface‐enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), nonlinear optical properties, and the quantized charging effect (Zhou et al., 2015). Over the past two decades, a significant progress has been made on AuNP‐based detection for viruses as well as other pathogens and diseases, which is evidenced by the dramatically increased number of publications found in PubMed since the year 2001 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The number of PubMed records for terms “gold nanoparticle detection” and “gold nanoparticle virus detection” from 2001 to 2020

In this review, we summarize recent AuNP‐based virus detection applications based on the amplification and detection strategies used. Our goal in this review is to understand the status quo of AuNP‐based assays for virus detection applications and provide considerations for the design of AuNP‐based COVID‐19 diagnostics and insights into trending parameters of IVDs so that researchers can incorporate the knowledge and develop AuNP‐based assays more efficiently for combating COVID‐19, as well as for other infectious diseases in the future.

2. RECENT ADVANCES IN AuNP‐BASED VIRUS DETECTION

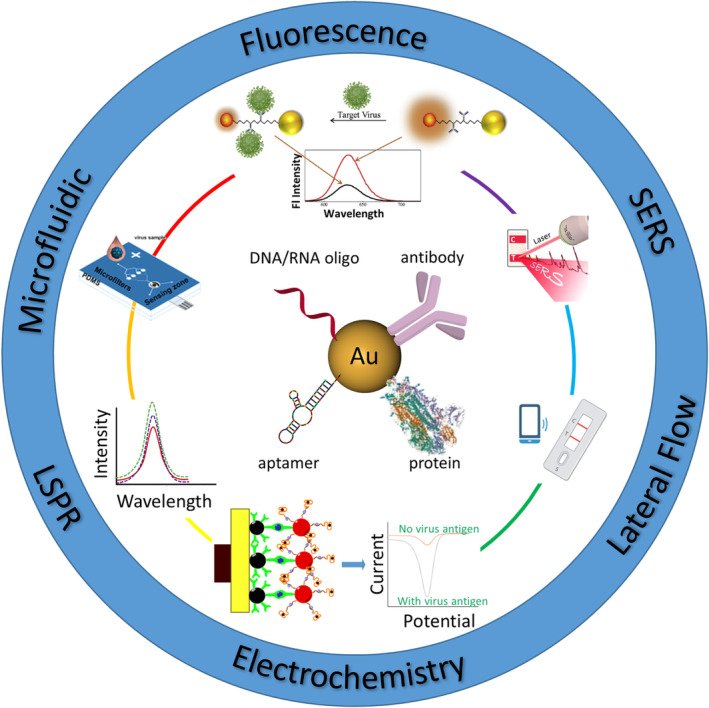

In the following sections, we will mainly discuss the recent advances in AuNP‐based virus detection since 2016, as earlier studies have been well summarized elsewhere (Draz & Shafiee, 2018). We have divided the detection assays based on the amplification strategy involved, whether it is through a more traditional approach or a combination of different amplification strategies to maximize the limit of detection (LOD) (Figure 2). An extensive overview of recent applications in AuNP‐based virus detection is shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic illustration of AuNP‐based virus detection approaches discussed in this article

TABLE 1.

Overview of recent applications in AuNP‐based virus detection

| Virus/target | AuNPs | Detection or capture molecule | Assay | Detection range | Detection limit | Real sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS‐CoV‐2/N gene RNA | Spherical ⁓10 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Colorimetric | 0.2–3 ng/μl | 0.18 ng/μl | Oropharyngeal swab | Moitra et al. (2020) |

| SARS‐CoV‐2/RdRp gene RNA | Film n.a. | Complementary DNA oligo | LSPR | 0.1 pM–1 μM | 0.22 pM | Synthetic DNA oligo | Qiu et al. (2020) |

| SARS‐CoV‐2/IgG, IgM | Spherical ⁓40 nm | Recombinant spike protein | LFIA colorimetric | n.a. | n.a. | Fingerstick blood, serum, plasma | Li et al. (2020) |

| H1N1/HA | Spherical ⁓26 nm | Ab | Fluorescence | 10−14–10−9 g/ml | 17.02 fg/ml | Recombinant H1N1 | Nasrin et al. (2020) |

| H1N1/HA | Spherical ⁓23 nm | Ab | LFIA immunochromato reader | 6.25 × 10−3 − 6.4 HAU/ml | 6.25 × 10−3 HAU/ml | Commercial HA | Matsumura et al. (2018) |

| H1N1 H3N2/HA | Hexagonal ⁓30 nm | Ab | Colorimetric |

5 × 10−15 − 5 × 10−6 g/ml (H1N1) 6 × 10−1 − 6 × 106 PFU/ml (H3N2) |

44.2 × 10−15 g/ml (H1N1) 2.5 PFU/ml (H3N2) |

Recombinant H1N, clinical H3N2 in human serum | Oh et al. (2018) |

| H1N1, norovirus/DNA oligo | Spherical 20–200 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical | 1 pM–10 nM |

8.4 pM (H1N1) 8.8 pM (norovirus) |

DNA oligo | Lee et al. (2018) |

| H1N1, H3N2/NA | Quasi‐Spherical ⁓32 nm | Ab | FRET | 10–100 pg/ml | H1N1: 0.03 pg/ml (DI water), 0.4 pg/ml (human serum), H3N2: 10 PFU/ml | Human serum | Takemura et al. (2017) |

| H3N2 AIV/HA | Spherical 10–60 nm | Ab | Colorimetric | 10–5 × 104 PFU/ml | 3.4 PFU/ml | Clinically isolated virus spiked in human serum | Ahmed et al. (2016) |

| H5N1/HA | Bipyramid n.a. | Ab | Colorimetric | 0.001–2.5 ng/ml | 1 pg/ml | HA spiked in human serum | Xu et al. (2017) |

| H5N2 AIV /HA | Spherical ⁓13 nm | mAb | Microfluidic colorimetric | 8 × 103 to ⁓8 × 106 EID50/ml |

2.7 × 104 EID50/ml (naked eye) 8 × 103 EID50/ml (smartphone) |

n.a. | Xia et al. (2019) |

| H7N9/HA | Spherical 11–41 nm | Ab | Electrochemical | 0.01–1.5 pg/ml | 7.8 fg/ml | Inactivated H7N9 spiked in ground chicken liver and serum | Wu et al. (2018) |

| H9N2 AIV/M2, HA | Spherical ⁓14 nm | Ab, Fetuin A | Electrochemical | 8–128 HAU titer | 16 HAU titer | Allantoic fluid | Sayhi et al. (2018) |

| HBV/HBsAg | Spherical ⁓20 nm | Ab | Electrochemical | 0.5–10,000 pg/ml | 166 fg/ml (S/N = 3) | Human serum | Pei et al. (2019) |

| HBV/HBsAg | Spherical ⁓15/30/50 nm | Ab | LSPR | 102–107 fg/ml | 100 fg/ml | HbsAg solution | Kim et al. (2018) |

| HBV/HBsAg | Spherical ⁓15 nm | Ab | Photoelectrochemical | 0.005–30 ng/ml | 0.5 pg/ml | Human serum | Hu et al. (2018) |

| HBV/HBsAg | Spherical 15–20 nm | Ab | Electrochemical | 0.3–1000 pg/ml | 0.19 pg/ml | HbsAg spiked in human serum | Alizadeh et al. (2017) |

| HBV/HBsAg | Spherical 16–65 nm | Ab | Fluorescence | 10−4–1 IU/ml | 5 × 10−4 IU/ml | HbsAg spiked in PBS | Wu et al. (2017) |

| HBV/DNA oligo | Spherical ⁓15 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | LFA colorimetric | 0.1 pM–250 nM | 0.01 pM | DNA oligo spiked in human serum | Gao et al. (2017) |

| HBV/DNA | Spherical ⁓30 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical | 102–105.1 copies/ml | 111 copies/ml | DNA isolated from clinical samples | Chen et al. (2016) |

| HBV/DNA | Spherical ⁓13 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | LFA colorimetric | 134–5.35 × 108 IU/ml | 134 IU/ml | Clinical blood sample | Choi et al. (2016) |

| HBV HCV/DNA | Spherical n.a. | Complementary DNA oligo | ECL |

0.5–500 pM (HBV) 1–1000 pM (HCV) |

0.082 pM (HBV) 0.34 pM (HCV) |

DNA oligo spiked in human serum | Liu et al. (2016) |

| HCV/RNA extract | Spherical 20–41 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | LSPR | 10–1200 IU/μl | 4.57 IU/μl | Human serum | Shawky et al. (2017) |

| HEV/virus | Spherical ⁓14 nm | Ab | Colorimetric | 8.75 × 10−8–10−11 g/ml | 4.3 × 10−12 g/ml | Monkey feces | Khoris et al. (2020) |

| Zika/NS1 | Spherical ⁓102 nm | Ab | SERS | 10 ng/ml–50 μg/ml | 12.5 ng/ml | Recombinant NS1 in PBS | Camacho et al. (2018) |

| Zika/DNA | Spherical ⁓13 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical | 10−12–10−6 M | 0.82 pM | Human serum | Steinmetz et al. (2019) |

| Zika/RNA | Spherical 2.7–4.4 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | FRET | 6.73–6730 copies/ml | 1.7 copies/ml | Culture supernatant total RNA isolation | Adegoke et al. (2017) |

| Norovirus/NoV GII | Spherical ⁓12 nm | Ab | Colorimetric | 102–106 copies RNA/ml fecal solution | 13.2 copies/ml fecal solution | Feces | Khoris et al. (2019) |

| Norovirus/virus | Spherical ⁓20 nm | Aptamer | Colorimetric | 200–33,000 copies/ml | 30 copies/ml | Cultured virus | Weerathunge and Ramanathan (2019) |

| Norovirus/virus | Spherical ⁓11 nm | Ab | FRET | 102–105 copies/ml | 95 copies/ml | Feces | Nasrin et al. (2018) |

| Norovirus/capsid protein | Spherical ⁓16 nm | DNA aptamer | Microfluidic electrochemical | 100 pM–3.5 nM | 100 pM | rVLP spiked in peptidoglycan solution or whole bovine blood | Chand and Neethirajan (2017) |

| Norovirus/NoV‐LP | Spherical 10–500 nm | Ab | Colorimetric | 100 pg/ml–10 μg/ml | 92.7 pg/ml | NoV‐LP spiked in human serum | Ahmed et al. (2017) |

| Norovirus/flavivirus group antigen | Spherical ⁓200 nm | Ab | Electrochemical | 0.01 pg/ml–1 ng/ml | 1.16 pg/ml | NoV‐LPs | Lee et al. (2017) |

| HIV‐1/pol gene oligo | Spherical ⁓75 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical | 10−16–10−7 M | 3.7 × 10−17 M | DNA oligo | Shamsipur et al. (2019) |

| HIV/DNA oligo | Spherical ⁓13 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | PCR‐DLS | 10 aM – 1.9 pM | 1.8 aM | DNA oligo spiked in human serum | Zou and Ling (2018) |

| HIV/DNA oligo | Spherical ⁓28 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | RCA fluorescence | 5 fM–1.67 pM | 1.46 fM | DNA oligo spiked in bovine serum | Zheng et al. (2018) |

| HIV/p24 protein | Cluster ⁓2 nm | Ab | Fluorescence | 5–1000 pg/ml | 5 pg/ml | Protein spiked in buffer or human serum | Kurdekar et al. (2018) |

| HIV‐1/DNA oligo | Spherical ⁓40 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | LFA SERS | 0–64 ng/ml | 0.24 pg/ml | DNA oligo in buffer | Fu et al. (2016) |

| EV71/VP2 | Spherical ⁓13 nm | Ab | LDI‐MS | 103–105 PFU/ml | 103 PFU/ml | Clinical human serum | Chu et al. (2019) |

| EV71/virion | Spherical ⁓13 nm | Ab | Fluorescence | 1.67 × 103–2.505 × 105 copies/ml | 1.4 copies/μl | Clinically isolated | Xiong et al. (2018) |

| EV71/VP1 | Spherical ⁓27 nm | Ab | Colorimetric | 0.25–10,000 ng/ml | 0.65 ng/ml | Human throat and cloacal swabs | Xiong et al. (2017) |

| Ebola/oligo | Spherical n.a. | Complementary DNA oligo | LRET | 50–700 fM | 300 fM | Clinically isolated RNA | Tsang et al. (2016) |

| Ebola/IgG | Spherical ⁓20/40 nm | Anti‐human IgG Ab rGP1–649 VP40 NP | LFIA smart phone reader | 20 ng/ml–20 μg/ml | 200 ng/ml | Sera | Brangel et al. (2018) |

| Ebola virus/glycoprotein | Spherical ⁓20 nm | Ab | LFIA fluorescence colorimetric | 2–1000 ng/ml | 0.18 ng/ml | Glycoprotein or whole virion spiked in buffer, tap water, urine, and plasma | Hu et al. (2017) |

| Dengue/ | Spherical ⁓78 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical fluorescence | 10−14–10−6 M | 9.4 fM | DNA oligo spiked in PBS buffer | Dutta Chowdhury and Ganganboina (2018) |

| Dengue/NS1 | Spherical ⁓40 nm | Ab | Electrochemical | 1–25 ng/ml | 0.5 ng/ml | NS1 spiked in PBS | Sinawang et al. (2016) |

| HPV 16/L1 protein | Spherical ⁓5/20/40 nm | Aptamer | LDI‐MS | 2–80 ng/ml | 58.8 pg/ml | Clinical sample, HPV vaccine | Zhu et al. (2019) |

| IPNV/virus | Spherical ⁓5 nm | Ab | Fluorescence LFIA colorimetric | 8–8 × 104 TCID50/ml |

1.02 TCID50/ml (fluorescence) 0.88 TCID50/ml (LFIA) |

Recombinant virus | Chayan et al. (2019) |

| NDV–AV29/virus | Spherical ⁓80 nm | Ab | LSPR | 5–5000 pg/ml | ~25 pg/ml with a minimum detectable volume of 200 μl or 5 pg | Allantoic fluid | Luo et al. (2018) |

| Coxsackie B3/oligo | Spherical ⁓16 nm | Complementary DNA oligo | Electrochemical | 0.01–20 μM | 0.18 nM | DNA oligo | Nagar et al. (2019) |

| FAdV‐9/virus | Nanobundle ⁓700 nm (length) ⁓10 (diameter) | Ab | optoelectronic | 10–104 PFU/ml (buffer), 50–104 PFU/ml (chicken blood) | 8.75 PFU/ml (buffer), 37.15 PFU/ml (chicken blood) | PBS buffer, chicken blood | Ahmed et al. (2018) |

| SFTSV/nucleocapsid protein | Spherical ⁓20 nm | Ab | LFIA colorimetric | 0.1–2000 ng/ml | 1 ng/ml | Human serum | Zuo et al. (2018) |

| Rubella virus/IgM | Rod ⁓60 × 16 nm | Rubella antigen | Colorimetric | 10–107 ng/ml | 10 ng/ml | Clinical serum samples | Zhang et al. (2018) |

Abbreviations: AIV, avian influenza virus; ECL, electrochemiluminescence; EV71, Enterovirus 71; FAdV‐9, Fowl adenovirus‐9; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; HA, hemagglutinin; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus; HIV‐1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; HPV, human papillomavirus; IPNV, infectious pancreatic necrosis virus; LDI‐MS, laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry; LFA, lateral‐flow assay; LFIA, lateral‐flow immunochromatographic assay; LSPR, localized surface plasmon resonance; M2, Matrix protein 2; n.a., not available; NA, neuraminidase; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NoV‐LP, norovirus‐like particle; NP, nucleoprotein; RCA, rolling circle amplification; rGP, recombinant glycoprotein; rVLP, recombinant virus‐like particle; SERS, surface‐enhanced Raman scattering; SFTSV, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus; VP40, matrix protein.

2.1. Single amplification‐based detection

2.1.1. Lateral flow assays

The lateral‐flow assay (LFA) is probably the most commonly used point‐of‐care (POC) diagnostic format of AuNP‐based IVD. For example, over‐the‐counter (OTC) pregnancy test strips are widely used from home due to ease of use, short testing time, and low cost. For virus detection, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is typically used due to its high sensitivity and specificity. However, it often requires specialized equipment and reagents, along with trained personnel to operate. In contrast, paper‐based LFAs require no expensive equipment and can be performed with simple steps and return results within minutes, making them useful tools in field applications and remote and low‐resource settings.

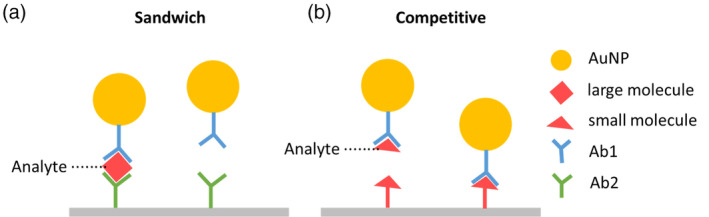

In a traditional LFA, antibodies are used as capture or detection molecules. This type of LFA is called a lateral‐flow immunochromatographic assay (LFIA). Generally, LFIAs have two formats: sandwich format and competitive format. For analytes with more than one epitope (e.g., viruses), the sandwich format LFIA (Figure 3a) is commonly used. In this format, antibodies against the target analyte are dispensed at the test line. When target analytes are present in the sample, analytes bind to antibody‐NP conjugates first, followed by secondary binding to antibodies pre‐immobilized on the test surface, which forms a sandwich complex and displays a color indicating a positive result. When there is no target analyte present in the sample, the antibody‐NP conjugates would not bind to the test line and no color changes would be displayed. For analytes with lower molecular weights and a single antigenic determinant, which cannot bind two antibodies simultaneously, the competitive format LFIA (Figure 3b) is applicable. In this case, target antigens are dispensed at the test line. When the target analytes are present in the sample, the analytes bind to the antibody‐NP conjugates and leave the test line blank, indicating a positive result. When target analytes are absent, in contrast, the antibody‐NP conjugates bind to the antigens pre‐immobilized at the test line, which displays a visible test line indicating a negative result.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic of LFIA formats. (a) Sandwich format. (b) Competitive format

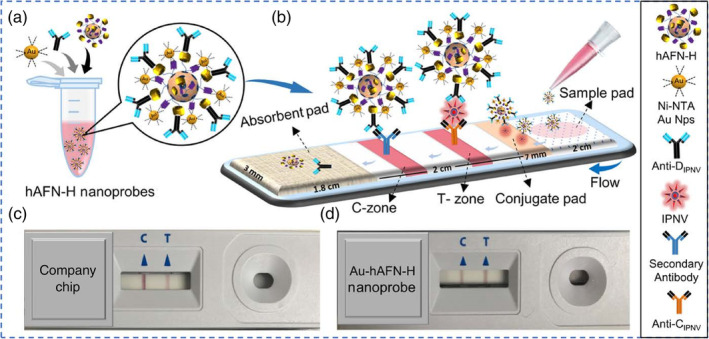

For AuNP‐based LFIAs, antibodies are typically conjugated directly to AuNPs. In a recent study, Chavan et al. developed a protein nanoparticle as a new scaffold by genetically modifying human apoferritin heavy chain protein with a 6×His and protein‐G tag, enabling direct binding of 5 nm Ni‐NTA‐nanogold and anti‐infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) antibodies, respectively. This approach effectively avoids bioconjugation through chemical linkers (Figure 4). The efficiency of this nanoprobe was tested for IPNV detection in an LFIA format, in which case a linear range of 101–103 TCID50 (median tissue culture infectious dose)/ml with a LOD of 0.88 TCID50/ml was obtained, which is equivalent to c.a. 0.62 PFUs/ml (ATCC website. https://www.atcc.org/support/faqs/48802/Converting+TCID50+to+plaque+forming+units+PFU-124.aspx). Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that this nanoprobe exhibited excellent sensitivity towards IPNV, in contrast to the commercial paper‐based system, and holds promise to be adapted for the detection of other biomarkers (Chayan et al., 2019).

FIGURE 4.

Schematic diagram for paper chip‐based detection of IPNV. (a) Ni‐NTA‐nanogold (5 nm) and anti‐DIPNV antibodies bind to the surface of the recombinant hAFN‐H to form the Au‐hAFN‐H nanoprobes. (b) Immobilization of IPNV‐bound and unbound Au‐hAFN‐H nanoprobes at the T‐ and C‐zones, respectively, on the paper chip. Representative images of actual paper chips used for IPNV detection, using (c) a commercially available company chip and (d) Au‐hAFN‐H nanoprobes. Reprinted with permission from Chayan et al. (2019). American Chemical Society

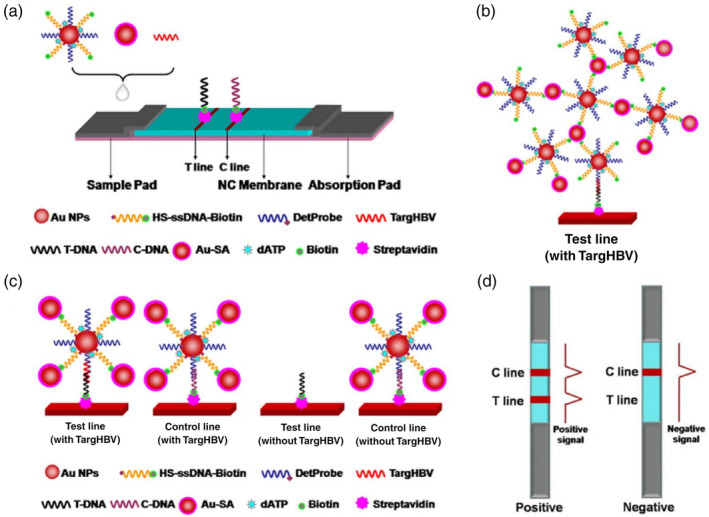

Although antibodies have been the commonly employed detection molecules in LFA‐based diagnostics, they face some challenges. For example, the choice of targets has been limited to proteins on the viral surface. Moreover, cross activities may be a concern among viruses with close homology. Nucleic acid‐based detection holds great promise in addressing this. In a recent study, Gao et al. engineered a nanoprobe consisting of a 15 nm AuNP labeled with two DNA oligos: (i) one as a detection DNA oligo, which is complementary to the target DNA and (ii) an additional biotinylated DNA oligo as a streptavidin assembly site for three‐dimensional DNA‐AuNPs network amplification (Figure 5). A 30‐base nucleotide sequence characteristic of the hepatitis B virus (targHBV) was selected as a model to test the performance of this nanoprobe. The authors reported a linear range of target concentration from 0.1 pM to 250 nM with a LOD of 0.01 pM, which is four orders of magnitude more sensitive than traditional sandwich assays without network amplification, although a real sample of long DNA with secondary structures will need to be investigated in their future work (Gao et al., 2017).

FIGURE 5.

Lateral flow test amplified by Au‐SA for nucleic acid detection. (a) Schematic representation of the configuration of the test strip. (b) Schematic illustration of the detection of nucleic acid using Au‐SA enhanced lateral flow assay. (c) Network structure on test line in the presence of targHBV. (d) Interpretation of positive and negative results. Reprinted with permission from Gao et al. (2017). Elsevier B.V

LFAs provide a simple and fast diagnostic tool for both clinical professionals and the public through OTC devices. The global LFA market has made solid growth over the past few decades and is anticipated to reach over $9 billion by 2024 (Lateral Flow Assay Market. https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/lateral-flow-assay-market). Nevertheless, more efforts needed to be devoted in order for LFAs to meet new requirements and challenges. First, sensitivity. Clinical professionals have a persisting need for better sensitivity so viruses, as well as other biomarkers, can be detected at earlier stages of disease progression. Second, digitalization. The digitalization of LFAs can offer many benefits. One promising approach is to integrate LFAs into mobile devices with cameras and image analysis software, which could help patients interpret LFA results and share information with healthcare providers. Third, multiplexing. Multiplexing endows LFAs the ability to analyze multiple analytes in a single sample, which can reduce the number and volume of samples required and reduce test times and costs, but provide more information to healthcare providers. Fourth, more efforts are needed for the development of LFAs relying on nucleic acid and other capture molecules instead of antibodies, for nucleic acid‐based diagnosis. In light of the COVID‐19 pandemic, developing nucleic acid or antigen‐based LFAs will enable direct detection of SARS‐CoV‐2.

2.1.2. Fluorescent assays

Another characteristic of AuNPs that has been well utilized in biosensor development is LSPR‐induced fluorescence quenching or enhancement, including FRET (Zhou et al., 2015) and nanoparticle surface energy transfer (Griffin et al., 2009).

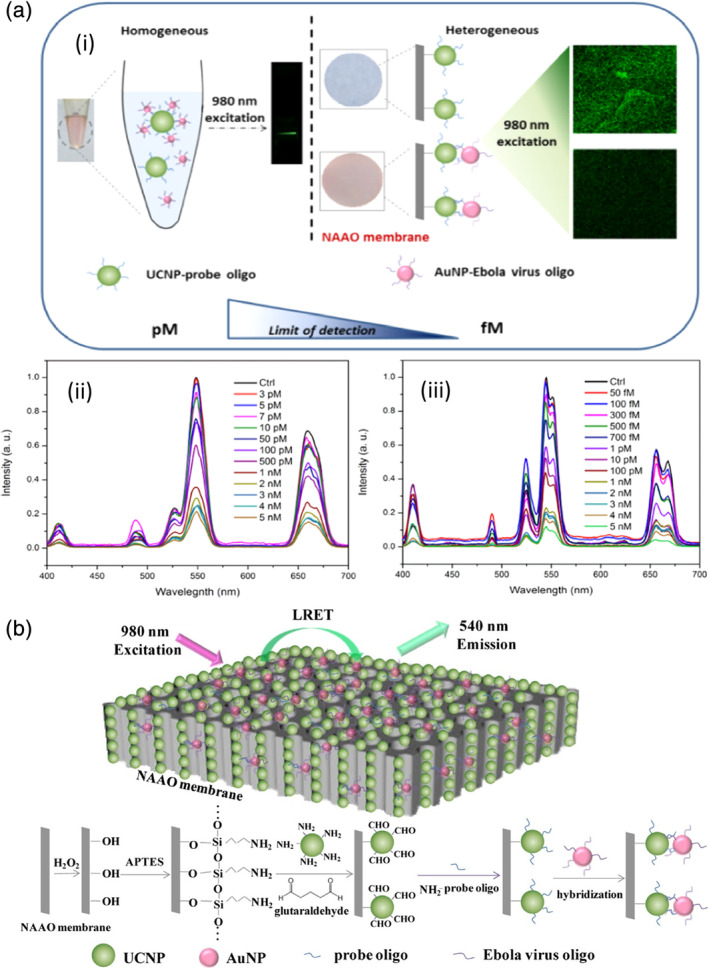

Recently, a luminescence resonance energy transfer biosensor specific for the Ebola virus was demonstrated by Tsang and coworkers. This sensor consisted of two types of NPs: a 980‐nm absorbing BaGdF5:Yb/Er upconversion nanoparticle (UCNP) conjugated with oligonucleotide probe and an AuNP linked with Ebola virus oligonucleotide. For clinical samples, viral RNA was extracted and conjugated to carboxylated AuNPs via EDC chemistry. When the target virus was present, AuNP bound to UCNP through DNA/DNA or DNA/RNA hybridization caused the quenching effect to take place. The AuNP‐bound UCNP through DNA/DNA or DNA/RNA hybridization and the quenching effect took place. As a result, the intensity of the main emission peaks (523, 546, and 654 nm) of UCNP decreased in proportion to the concentration of virus oligos. Two formats, homogeneous and heterogeneous, were developed. The homogeneous format simply mixed two types of NPs in a colloidal solution. Subsequently, green upconversion luminescence emission was observed with the naked eye as a result of 980 nm laser excitation. For the heterogeneous format, UCNPs were anchored on a nanoporous alumina (NAAO) membrane (Figure 6). Compared to the homogeneous assay, the LOD of the heterogeneous assay is significantly improved from 7 pM to 300 fM (Tsang et al., 2016). The short reaction time and easy operation of the nanoprobe are advantages of this assay compared to other existing detection methods, such as real‐time PCR (RT‐PCR) and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

FIGURE 6.

(a) (i) Comparison of the homogeneous and heterogeneous assays for Ebola virus oligo detection; (ii) UC emission spectra of BaGdF5:Yb/Er‐probe UCNPs with various concentrations of Ebola virus oligo target in the homogeneous assay; (iii) UC emission spectra of BaGdF5:Yb/Er‐probe UCNPs with various concentration of Ebola virus oligo target in the heterogeneous assay with NAAO membrane. (b) Schematic diagram of Ebola target oligo detection based on LRET biosensor with energy transfer from UCNPs to AuNPs on NAAO membrane. Reprinted with permission from Tsang et al. (2016). American Chemical Society

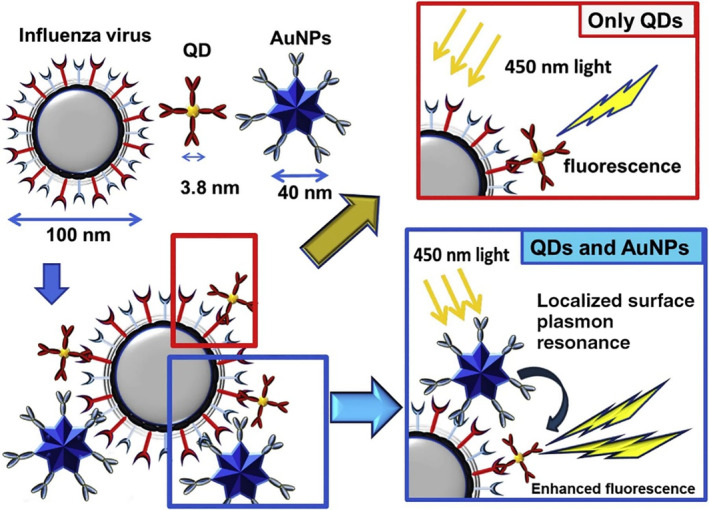

Takemura et al. developed a fluorescence‐enhancement influenza virus immunosensor using anti‐NA Ab‐conjugated AuNPs in conjunction with anti‐HA Ab‐conjugated QDs. As shown in Figure 7, the simultaneous binding of AuNP and QD to the same virus virion brought AuNPs in close proximity to QDs and triggered an LSPR‐induced fluorescence enhancement, which in turn provided a quantitative linear concentration range of 10–100 pg/ml and LOD down to 0.03 pg/ml for H1N1 detection (Takemura et al., 2017).

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of the detection principle for the influenza virus using the LSPR‐induced fluorescence nanobiosensor. Reprinted with permission from Takemura et al. (2017). Elsevier B.V

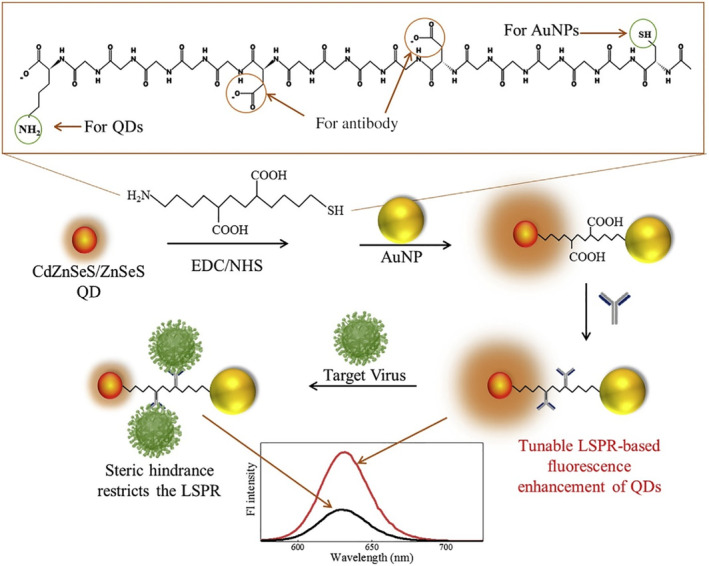

In a recent study by Nasrin and coworkers, an AuNP‐based H1N1 immunosensor was developed based on the exquisite manipulation of the distance between QD and AuNP before and after virus binding. The study clearly showed a distance‐dependent LSPR influence, from fluorescence quenching when AuNP and QD were very close together, to a continuous fluorescence enhancement when the distance was above a threshold. In the sensor, an 18 amino acid‐based peptide linker was used to tether AuNP and QD to each end and two antibodies were anchored in the middle for virus binding (Figure 8). When no virus was present, AuNP and QD were in close proximity and the fluorescence intensity of QD was low. When the virus was present and bound to the antibodies, the steric hindrance helped to lift fluorescence in proportion to a virus concentration range of 10−14–10−9 g/ml. Impressively, an ultra‐low LOD of 17.02 fg/ml was achieved (Nasrin et al., 2020).

FIGURE 8.

Schematic diagram for the preparation of CdZnSeS/ZnSeS QD‐peptide‐AuNP nanocomposite and its detecting mechanism towards the influenza virus. AuNPs and QDs are conjugated by peptide linkers in this current work. Reprinted with permission from Nasrin et al. (2020). Elsevier B.V

A traditional AuNP‐based fluorescent assay consists of fluorophores, and AuNPs often as fluorescence quenchers, featuring high sensitivity, biocompatibility, easy and tunable AuNP synthesis, and unique distance‐dependent fluorescence quenching/enhancement properties of AuNPs. However, precise control of the distance between AuNP and fluorophore remains a challenge. Alternatively, assays using fluorescent AuNPs (e.g., gold nanoclusters), which function as fluorophores by themselves, represent another type of AuNP‐based fluorescent assays. Like all fluorescent assays, background fluorescent signals, particularly for complex clinical samples, often cause an issue. This issue can be potentially addressed using NIR dyes or UCNPs in combination with two‐photon optics.

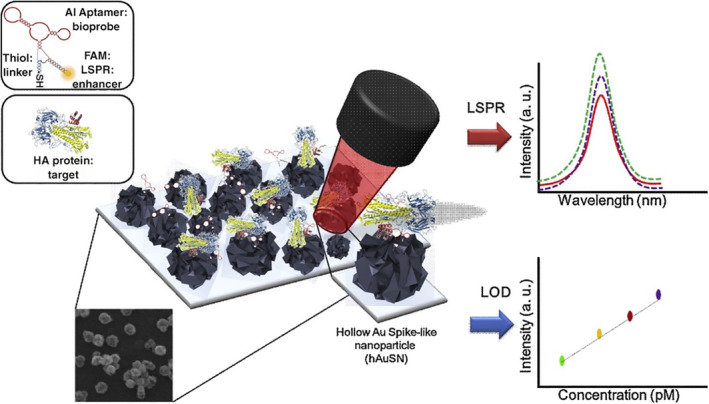

2.1.3. LSPR assays

LSPR of AuNPs is largely driven by the light‐induced excitation of conduction electrons. LSPR is a characteristic optical property of AuNPs, which produces strong optical absorption or scattering at characteristic frequencies in the visible to NIR region (Wei et al., 2013). AuNPs are well known as LSPR sensors due to their sensitive spectral response to the local environment of the nanoparticle surface, and many AuNP‐based LSPR sensors have been reported in virus detection applications recently (Kim et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2018; Qiu et al., 2020; Shawky et al., 2017). Lee et al. engineered an H5N1 aptasensor using hollow Au spike‐like NPs functionalized with aptamers specific for hemagglutinin (HA) protein (Figure 9). A detection limit of 1 pM was obtained with a linear concentration range of 1 pM to 10 nM HA spiked in chick serum (Lee et al., 2019). In addition, Shawky et al. (2017) developed an AuNP‐based nucleic acid sensor for HCV detection from human serum containing isolated HCV RNA and obtained a LOD of 4.57 IU/μl. Another study by Kim et al. (2018) showed a LOD of 100 fg/ml for HBV detection using an HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) Ab‐coated AuNP as the probe and LSPR peak shift as the readout.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic image of the fabricated AIV detection biosensor based on the LSPR method. Reprinted with permission from Lee et al. (2019). Elsevier B.V

The advantage of AuNP‐based LSPR assays is quite obvious: the positives are often interpretable by the naked eye, although quantitative analysis will rely on a simple UV–Vis spectrometer or plate reader. However, precautions are needed to prevent pitfalls of false positives especially in complex samples, since AuNPs tend to aggregate when high ionic strength and high levels of biothiols are present, as most AuNPs are stabilized by ligands via a thiol linkage. Moreover, a few challenges, such as sensitivity, selectivity in complex biological solutions, and adaptation of sensing elements for POC diagnostic devices need to be addressed before a wider translation of LSPR‐based assays into clinical practice (Unser et al., 2015).

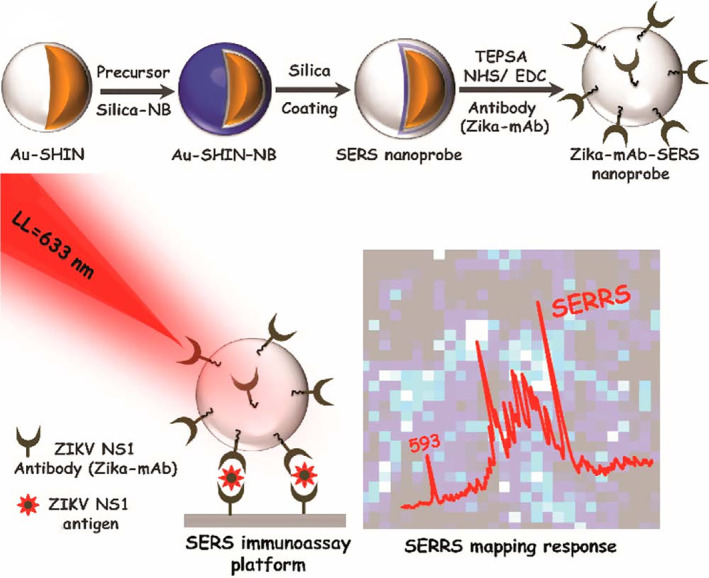

2.1.4. SERS assays

SERS spectroscopy has emerged as a next‐generation biosensor technology that affords rapidity, high sensitivity, multiplexing and can be miniaturized for POC applications in conjunction with portable Raman readers (Neng et al., 2013). SERS sensors usually consist of Raman reporters adsorbed to noble metal (i.e., Ag or Au) nanoparticles or roughened noble metal surfaces, which produce an electromagnetic field upon laser excitation because of their LSPR property. Strong inelastic light scattering from Raman reporters can be further magnified and used as a readout for quantitative analyte detection. AuNPs have been employed in SERS for decades and many groups have developed AuNP‐based SERS assays for virus detection in the past (Kamińska et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Lim et al., 2015; Neng et al., 2013). Recently, Camacho et al. (2018) developed SERS probes using gold shell‐isolated nanoparticles (Au‐SHIN), which consists of 100 nm Au nanoparticles and a 4 nm silica shell as the scaffold and Nile Blue (NB) as the Raman reporter. The nanoprobes were wrapped in a final silica shell and functionalized with monoclonal anti‐NS1 antibodies for Zika virus (ZIKV) detection. The platform was irradiated with a 633 nm laser line and the surface‐enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS) signal from NB molecules, located in close proximity to AuNPs (∼4 nm), is recorded by area mappings. Brighter spots indicate the higher intensity of the NB band at 593 cm−1 (Figure 10). This method was used to detect NS1 in PBS with a range of 10 ng/ml–50 μg/ml and showed a LOD down to 10 ng/ml. Dengue virus (DENV) is another flavivirus that belongs to the same family of ZIKV. Impressively, no cross‐reactivity with DENV NS1 antigens was found, showing a good specificity for this platform.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic illustration of (a) Zika‐mAb‐SERS nanoprobe assembly: Au‐SHIN (∼100 nm Au core + 4 nm silica shell thickness); Au‐SHIN + NB Raman reporter layer; Au‐SHIN + NB Raman reporter layer + final ∼10 nm silica shell (SERS nanoprobe); conjugation onto Zika NS1 monoclonal antibodies (Zika‐mAb). (b) SERS immunoassay platform for detecting different concentrations of Zika NS1. The platform is irradiated with a 633 nm laser line and the SERRS signal from NB molecules, located in close proximity to gold nanoparticles (∼4 nm), is recorded by area mapping. Brighter spots indicate the higher intensity of the NB band at 593 cm−1. Reprinted with permission from Camacho et al. (2018). American Chemical Society

SERS offers many unique advantages over traditional fluorescent techniques, including ultrasensitivity and excellent multiplexing ability, especially insensitivity to photobleaching and quenching, which makes repetitive and long‐term measurement possible. Aside from these advantages and established improvements, significant technical challenges remain to be overcome before SERS‐based assays can be translated from proof‐of‐concept studies to clinically available tools. First, reproducibility. SERS signals are very sensitive to many parameters, such as the size and shape of nanoparticles, the distance between nanoparticles, and even the orientation of the “hot spots” to the incident laser. As batch variance is common with nanoparticle synthesis, even fine differences could lead to inconsistent results of SERS assays. Also, drying nanoparticles on a substrate is a common process of many SERS assays. This drying process may lead to nanoparticle aggregation and generate capture‐independent SERS signals, which make reproducible SERS measurement more challenging. Second, quantification of SERS signal in complex biological samples might not be straightforward and obtaining a broad linear detection range sometimes could be challenging. Third, the selection of Raman reporters is very critical for SERS‐based multiplexing detection. Ideally, Raman reporters used for multiplexing detection should have minimal spectral overlap, which can make deconvolution of each reporter much easier. Therefore, more efforts are needed in developing a larger pool of Raman reporters with high intensity and unique spectrum. Fourth, minimization of Raman reporter fluorescence background through the development of instrumentation or other suppression techniques is needed.

2.1.5. Electrochemical assays

Electrochemical biosensors represent another class of popular biosensors besides optical (e.g., colorimetric, fluorescent, chemiluminescent, etc.) biosensors (Table 1). Electrochemical biosensors often employ gold nanomaterials to enlarge the electrochemically active areas and improve the electron transfer efficiency between electrodes with detection materials, which can help to achieve better performance with ultrahigh sensitivity and stability (Holzinger et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2018).

Recently, Alizadeh et al. developed an electrochemical‐based HepB virus immunosensor. In this sensor, Fe3O4/antibody (Ab1) magnetic nanoparticles were adsorbed to the electrode by the magnetic field. G‐quadruplex DNA/hemin and antibody (Ab2) labeled AuNPs formed a sandwich‐structure when target analyte HBsAg was present in the sample, and as HRP mimicking‐DNAzyme, triggered methylene blue oxidation (Figure 11a). The oxidation signal was converted to a square wave voltammetry signal and provided a quantitative measurement of HbsAg with a linear concentration range of 0.3–1000 pg/ml and LOD of 0.19 pg/ml (Alizadeh et al., 2017). In another study of HepB virus detection, Pei et al. fabricated an electrochemical immunosensor using a carbon electrode coated with a AuNPs‐loaded polypyrrole nanosheet (AuNPs/PPy NS), which was further functionalized with specific antibodies for HBsAg capture (Figure 11b). The HBsAg concentration was converted to a quantitative electric current signal and provided a broader linear concentration range of 0.5–10,000 pg/ml and a similar LOD of 0.166 pg/ml (Pei et al., 2019).

FIGURE 11.

Schemata of the fabrication process of the sandwich‐type electrochemical immunosensor. (a) Reprinted with permission from Alizadeh et al. (2017). Elsevier B.V. (b) Reprinted with permission from Pei et al. (2019). Elsevier B.V

Electrochemical sensors hold the promise of transformative change in clinical practice due to their speed, sensitivity, and selectivity. Although electrochemical assays are very popular in proof‐of‐concept studies, they still face many challenges to achieve their goal. One drawback is many electrochemical assays rely on metallic or ceramic electrodes, which are relatively expensive. More efforts need to focus on developing alternative electrodes with cheaper materials (e.g., carbon‐based electrodes). Another drawback is that many electrochemical assays require a bulky instrument, which dramatically reduces its value as a POC tool. Integration with microfluidics is a good way to overcome both cost and portability challenges.

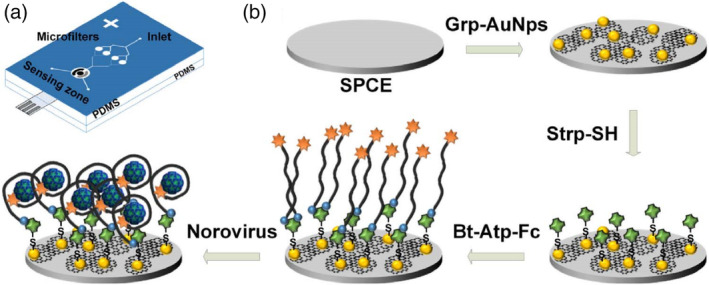

2.1.6. Microfluidic assays

Microfluidic systems are an attractive format for POC diagnostics that feature advantages such as portability, faster reaction time, enhanced analytical sensitivity, low reagent and sample consumptions, low cost, high‐throughput, easier automation, integration of lab routines in one device (lab‐on‐a‐chip), and so on. AuNPs are attractive for the development of microfluidic diagnostic devices because of their size‐dependent colorimetric and fluorescent properties. A study by Chand et al. reported a proof‐of‐concept microfluidic chip for the electrochemical detection of norovirus. As shown in Figure 12, screen‐printed carbon electrode was modified with a graphene‐AuNPs composite, which was further functionalized through streptavidin‐biotin binding with aptamer tagged with ferrocene as a redox probe. Using differential pulse voltammetric analysis, a detection limit of 100 pM with a detection range from 100 pM to 3.5 nM for norovirus was obtained (Chand & Neethirajan, 2017). The testing time of the proposed microfluidic electrochemical aptasensor was less than 35 min, which is faster than conventional ELISA and PCR analysis. With a specific aptamer, sensitivity and specificity can be further enhanced.

FIGURE 12.

Microfluidic electrochemical aptasensor for norovirus detection: (a) structure of PDMS microfluidic chip showing microfilters, sensing zone, and integrated screen‐printed carbon electrode (SPCE). (b) Sequence of electrode functionalization and aptasensing of norovirus. Bt‐Atp‐Fc, biotin and ferrocene tagged aptamer; Grp‐AuNPs, graphene‐gold nanoparticles composite; Strp‐SH, thiolated streptavidin. Reprinted with permission from Chand and Neethirajan (2017). Elsevier B.V

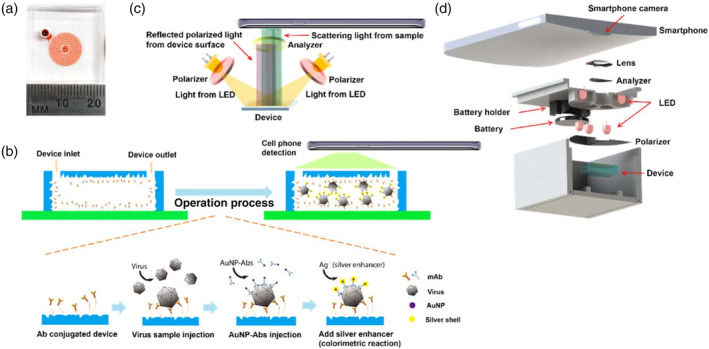

Later, Xia et al. fabricated a microfluidic sensor with PDMS herringbone structures coated with HA‐specific antibodies for H5N2 virus capture. The captured virus was further labeled with Ab‐coated Au–Ag core–shell NPs. A detection limit of 2.7 × 104 EID50/ml was obtained with visual detection by the naked eye, which was one order of magnitude better than that of conventional fluorescence‐based ELISA. The LOD was further improved to 8 × 103 EID50/ml with a pair of polarizers and a smartphone for imaging and colorimetric detection (Figure 13). The entire virus capture and detection process could be completed in 1.5 h (Xia et al., 2019).

FIGURE 13.

Design of the nanostructured microdevice and the portable smartphone‐enabled virus detection system. (a) Photo of the microfluidic device. (b) Schematic of the sandwich virus detection assay in the device. (c) Setup of the optical system. (d) Design of the smartphone imaging system. Reprinted with permission from Xia et al. (2019). American Chemical Society

Microfluidic assays benefit from portability, extremely low sample volume requirement, and hold great promise for high throughput screening, especially in low‐resource settings. Miniaturization and automation are critical to the commercial success of microfluidic assays. Several products, such as Filmarray®, Cobas® Liat®, GeneXpert®, and VerePLEX™ have already been commercialized. With the development of instrumentation in combination with modern technologies such as 3D printing, rapid prototyping becomes easily accessible. It is anticipated that more and more commercial microfluidic devices will become available.

2.2. Multi‐amplification‐based detection

Although single amplification‐based diagnostics are relatively easy to develop and easy to use, for applications that require an ultra‐low LOD, these single amplification‐based assays often lack sufficient sensitivity. In this section, we discuss recent advances in AuNP‐based virus detection using multi‐amplification strategies.

2.2.1. Lateral flow assays coupled with detection tools

As discussed above, LFA is one of the most popular AuNP‐based IVD formats. However, traditional LFAs face challenges like not being quantitative, poor sensitivity for some analytes, and so on. Along with the advancement of LFA development, more tools are integrated with traditional LFA strips to help overcome the aforementioned weaknesses, as discussed in detail below.

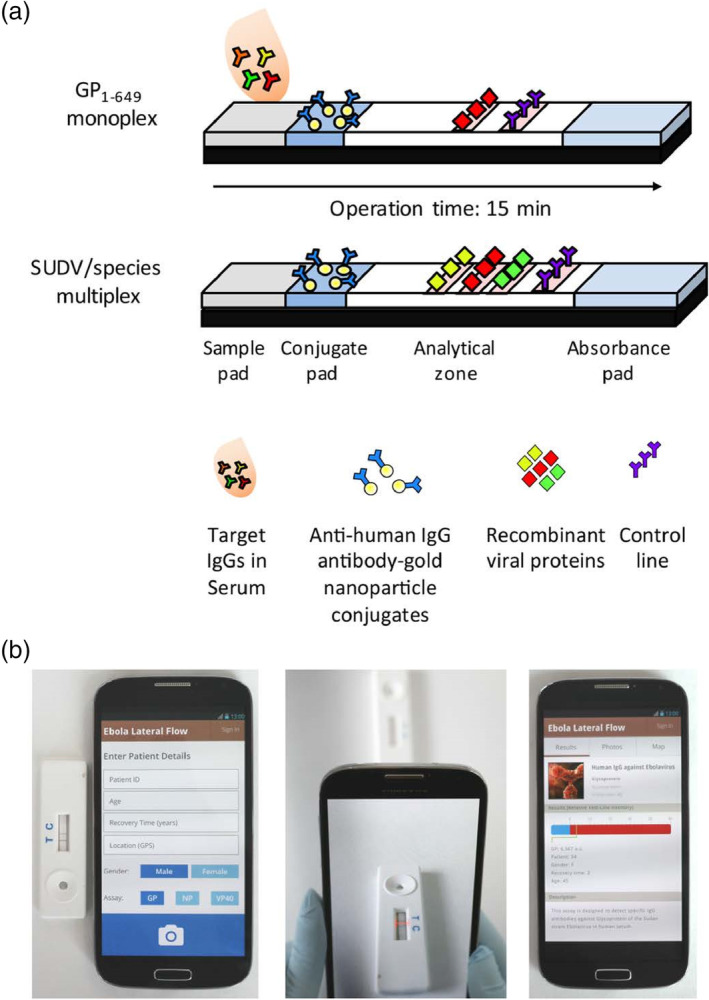

Brangel et al. designed an LFA assay combined with a custom smartphone application (app) for semiquantitative detection of viral hemorrhagic Ebola virus disease IgG antibodies in human serum. Two configurations were developed, one for monoplex detection of IgG against recombinant glycoprotein GP1–649, and the other for multiplex detection of either different Ebola species or different IgG antibodies against different viral proteins of the same virus (Figure 14). The monoplex platform demonstrated a 200 ng/ml LOD and 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity in a cohort of 90 SUDV survivors and 31 noninfected controls compared to standard whole antigen ELISA. The availability of a POC test to detect antibody immune response in multiplex platforms is especially valuable in remote areas for enhanced vaccine efficiency evaluation, as well as more efficient diagnosis, patient management, and surveillance both during and post outbreaks (Brangel et al., 2018).

FIGURE 14.

Smartphone lateral flow point‐of‐care test for Ebola virus IgG detection. (a) Lateral flow strip illustration: serum applied onto the sample pad migrates through the analytical area, and subsequently forms complexes between the labeled gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and the target analytes. Specifically targeted IgG serum antibodies against single or multiple recombinant Ebola viral proteins then bind to preprinted test lines, forming a visual red‐purple line. A control line is used to validate the assay function for the detection of antihuman antibody‐gold nanoparticle conjugates. Assay results appear after 15 min. (b) Illustration of the smartphone application (app) interface login window to record patient details; following submission, the analysis window opens; once the red box is aligned between the test and control lines, a tap on the screen provides the strips' analysis; result analysis window, which presents the relative intensity of the test line and determines whether the result is positive or negative based on an evaluated cutoff threshold. The window also provides a summary of patient details and a description of the test taken. Reprinted with permission from Brangel et al. (2018). American Chemical Society

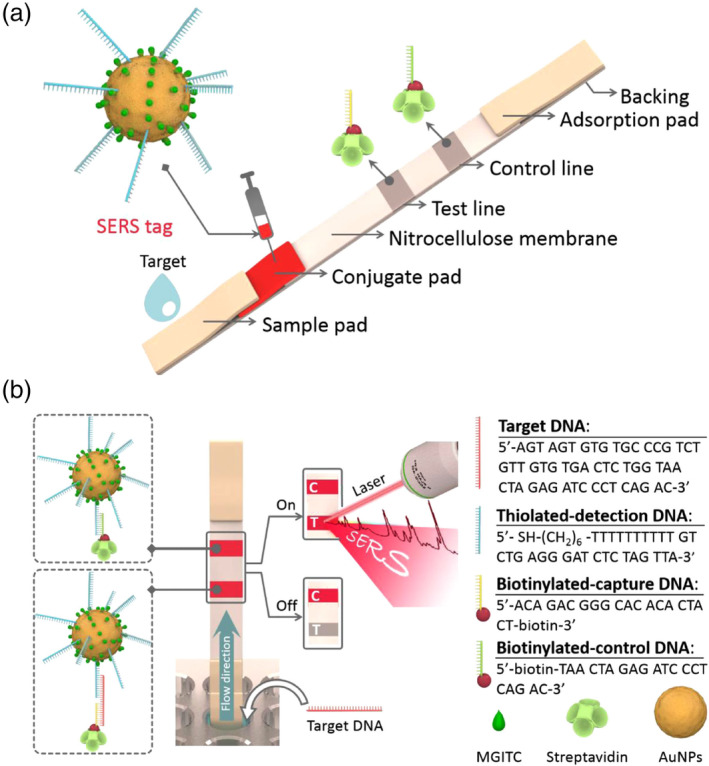

Another strategy to improve the sensitivity of AuNP‐based LFA is to characterize AuNPs after chromatographic separation using a sensitive analytical technique such as SERS. Fu et al. proposed a SERS‐based LFA using Raman reporter‐functionalized AuNPs as SERS tags, which were further functionalized with oligonucleotides as detection/capture molecules, for the quantitative analysis of HIV‐1 DNA (Figure 15). The authors were able to achieve a LOD of 0.24 pg/ml. In contrast, most commercial LFA products, including those for glucose and pregnancy tests, are limited to biomarkers with high concentrations (at mg/ml or μg/ml levels). Importantly, many portable Raman systems have already been commercialized. It is expected that the integrated SERS‐based LFAs can maintain high sensitivity and portability features simultaneously (Fu et al., 2016).

FIGURE 15.

(a) Schematic illustration of the configuration and (b) the measurement principle of the SERS‐based lateral flow assay for quantification of HIV‐1 DNA (C is the control line and T is the test line). Reprinted with permission from Fu et al. (2016). Elsevier B.V

2.2.2. Lateral flow assays with nucleic acid preamplification

LFIA and lateral flow aptamer assay rely on high‐quality antibodies or aptamers for antigen binding and detection. This not only increases the cost and production time, but they also suffer from poor availability and low sensitivity. Many samples from patients only contain very low virus titers. A diagnostic device with high sensitivity means viruses or diseases can be detected very early or at pre‐symptomatic phases, which is critical in the dissemination control of an epidemic or pandemic.

To obtain high sensitivity for virus detection, especially when nucleic acids become the target analytes, PCR‐coupled LFAs have emerged as a powerful tool. Traditional PCRs rely on professionals and expensive PCR cyclers for amplification, which is not practical for resource‐limited settings. Excitingly, many isothermal PCRs have been developed over the past few decades, which tremendously reduced the reliance on bulky instruments. Although many studies have applied different isothermal PCR methods for virus detection, including loop‐mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (Cheng et al., 2017; Chi et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2018), helicase‐dependent amplification (Moura‐Melo et al., 2015), rolling circle amplification (Xing et al., 2013), and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) (Wang & Yang, 2019), very few were integrated with LFAs.

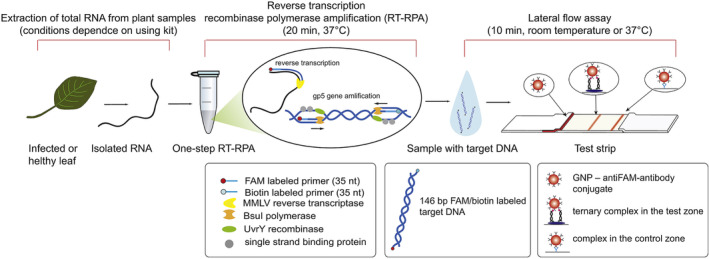

In a recent study, Ivanov et al. (2020) integrated RPA into an LFA for potato virus X (PVX) detection and obtained a LOD of 0.14 ng PVX per gram of potato leaves, which was 260 times more sensitive than a conventional lateral flow assay based on antibodies, and demonstrated the same sensitivity as PCR detection. Although isothermal amplification techniques simplify the process of nucleic acid amplification to a constant temperature, most of the isothermal amplification methods need to be performed at a temperature of 65°C or higher, which limits their field applications. This limitation has been improved with the development of RPA, which runs only at a constant temperature of 30–42°C. In Ivanov's study, the isolated virus RNA was amplified with a one‐step reverse transcription RPA (RT‐RPA) at 37°C for only 20 min and then loaded to a typical nucleic acid‐based LFA strip (Figure 16). Another study by Khater and Escosura‐Muniz (2019) showed that the RPA step can even be performed at room temperature, which further removed the need for a heating source (to be discussed in Section 2.2.3).

FIGURE 16.

The scheme of RT‐RPA‐LFA proposed for PVX detection. Reprinted with permission from Ivanov et al. (2020). Elsevier B.V

2.2.3. Electrochemical assays with nucleic acid preamplification

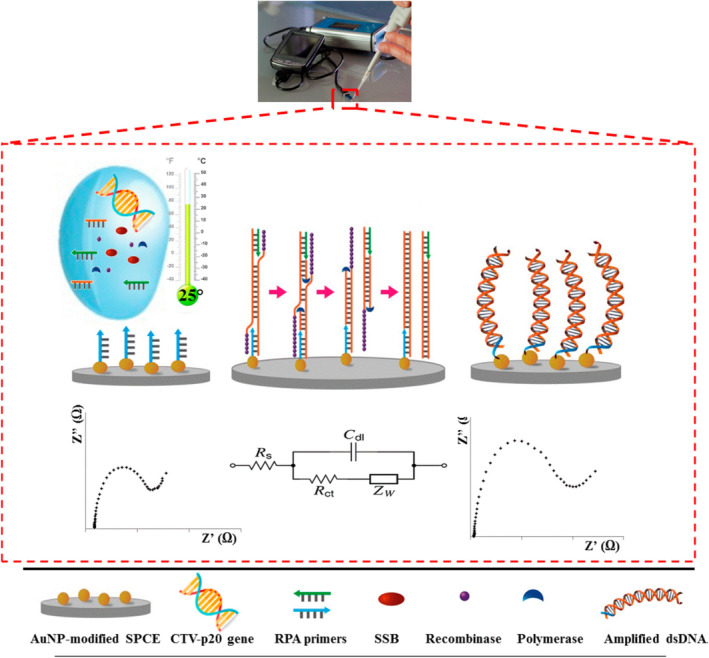

In a recent study by Khater and coworkers, an electrochemical nucleic acid biosensor was integrated with an in situ preamplification of Citrus tristeza virus DNA for highly sensitive detection. This assay employed solid‐phase isothermal RPA technology, which offered many benefits over the standard RPA in a homogeneous phase in terms of sensitivity, portability, and versatility (Khater & Escosura‐Muniz, 2019). Moreover, previous RPA devices are limited by the need for heating sources to reach sensitive detection. Importantly, this study demonstrated a high sensitivity (1 pg/μl) obtained at room temperature by using AuNP‐modified sensing substrates and electrochemical impedance spectroscopic detection (Figure 17) (Khater & Escosura‐Muniz, 2019). Although the use of 50 nm AuNP seems successful, incorporating AuNPs with other sizes might potentially further improve the sensitivity.

FIGURE 17.

Steps of the developed label‐free in situ isothermal RPA amplification/detection biosensor on primer‐modified SPCE‐AuNP electrodes employing impedance for the determination of CTV‐related nucleic acid. Reprinted with permission from Khater and Escosura‐Muniz (2019). American Chemical Society

Similar to the combination therapy strategies employed in cancer treatments, we hope this review can stimulate future thoughts and efforts on harnessing multi‐amplification strategies in developing AuNP‐based assays, in order to meet the persisting clinical need for better sensitivity.

3. CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUNP‐BASED TESTING FOR SARS‐CoV‐2

At the beginning of the pandemic, COVID‐19 is primarily diagnosed by RT‐PCR in conjunction with chest computed tomography for suspicious negative cases. Additional PCR assays have been approved by the FDA or are under rapid development to expand diagnosing capability. However, these methods are expensive, time‐consuming, and require sophisticated instruments and well‐trained personnel, which are not economical for mass screening and not practical in low‐resource settings. Portable, fast, sensitive, and affordable POC testing is of crucial importance in controlling the spread of a pandemic before effective treatment and vaccines become available. As aforementioned, AuNP‐based diagnostics can be developed to detect nucleic acids and antibodies, with detection limits comparable to, or even better than, RT‐PCR and commercial non‐AuNP‐based ELISA kits. Consequently, AuNP‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 testing is a powerful alternative to RT‐PCR and holds great potential for this enormous unmet biomedical need, especially in resource‐limited areas. As of January 17, AuNP‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 testing kits have already been approved for use in the United States (Table 2) and many other countries (Johns Hopkins website. https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/resources/COVID-19/serology/Serology-based-tests-for-COVID-19.html). In this section, we aim to discuss some considerations for developing effective AuNP‐based diagnostics for SARS‐CoV‐2.

TABLE 2.

FDA‐approved gold nanoparticle‐based serology tests for SARS‐CoV‐2 under EUA designation (as of January 17, 2021)

| Diagnostic | Manufacturer | Antibody/assay format | Sample | Authorized setting(s) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID‐19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette (Whole Blood/Serum/Plasma) | Healgen Scientific LLC | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| qSARS‐CoV‐2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test | Cellex Inc. | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venipuncture whole blood | H, M |

| WANTAI SARS‐CoV‐2 Ab Rapid Test | Beijing Wantai Biological Pharmacy Enterprise Co., Ltd. | Total antibody, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| Rapid COVID‐19 IgM/IgG Combo Test Kit | Megna Health, Inc. | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum and plasma | H, M |

| Tell Me Fast Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19) IgG/IgM Antibody Test | Biocan Diagnostics | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| TBG SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG / IgM Rapid Test Kit | TBG Biotechnology | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum and plasma | H, M |

| SGTi‐flex COVID‐19 IgG | Sugentech | IgG, lateral flow | Serum, venous whole blood, and plasma | H, M |

| Assure COVID‐19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Device | Assure Tech. (Hangzhou) | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, venous whole blood, and fingerstick whole blood | H, M, W |

| MosaiQ COVID‐19 Antibody Magazine | Quotient Suisse SA | Total Antibody, photometric immunoassay | Serum and plasma | H |

| Nirmidas COVID‐19 (SARS‐CoV‐2) IgM/IgG Antibody Detection Kit | Nirmidas Biotech | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum and plasma | H, M |

| Biohit SARS‐CoV‐2 IgM/IgG Antibody Test Kit | Biohit Healthcare (Hefei) | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venipuncture whole blood | H, M |

| CareStart COVID‐19 IgM/IgG | Access Bio | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| BIOTIME SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG/IgM Rapid Qualitative Test | Xiamen Biotime Biotechnology | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| Jiangsu Well Biotech | Orawell IgM/IgG Rapid Test | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum and plasma | H, M |

| Innovita 2019‐nCoV Ab Test | Innovita (Tangshan) Biological Technology | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| RightSign COVID‐19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette | Hangzhou Biotest Biotech | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, venous whole blood, and fingerstick whole blood | H, M, W |

| ACON SARS‐CoV‐2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test | ACON Laboratories | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum, plasma, and venous whole blood | H, M |

| LYHER Novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) IgM/IgG Antibody Combo Test Kit | Hangzhou Laihe Biotech | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Serum and plasma | H, M |

| MidaSpot COVID‐19 Antibody Combo Detection Kit | Nirmidas Biotech | IgM and IgG, lateral flow | Fingerstick whole blood, serum, and plasma | H, M, W |

| Sienna‐Clarity COVIBLOCK COVID‐19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette | Salofa Oy | IgM and IgG, Lateral Flow | Fingerstick whole blood | H, M, W |

| RapCov Rapid COVID‐19 Test | ADVAITE | IgG, Lateral Flow | Fingerstick whole blood | H, M, W |

Abbreviation: EUA, Emergency Use Authorization.

Authorized settings include the following: H—Laboratories certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, that meet requirements to perform high complexity tests. M—Laboratories certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, that meet requirements to perform moderate complexity tests. W—Patient care settings operating under a CLIA Certificate of Waiver.

3.1. Size and shape of AuNPs

Despite the rapid increase in publications and commercial products on AuNP‐based diagnostics in recent years, not many of them have carefully optimized the size and shape of AuNPs in their assays. To develop highly sensitive testings for SARS‐CoV‐2, the selection of AuNPs with proper size and shape is as important as the assay development itself. One beauty of using AuNP is that a wide range of sizes (a few to several hundred nanometers) and shapes (e.g., sphere, rod, core–shell, cube, star, cage, pyramid, Janus, etc.) of AuNPs and even hybrids with other nanoparticles can be synthesized in a controlled manner through well‐defined approaches (Grzelczak et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2013). The size and shape of AuNPs are closely associated with their physical and optical properties, which can greatly influence the performance of AuNP‐based diagnostics. For spherical AuNPs, 10–20 nm size is commonly chosen because of the ease of synthesis and good control of monodispersity as both smaller and larger AuNPs tend to have a higher polydispersity index. When developing an assay, depending on the property of AuNP employed, that size range might not be ideal. Generally speaking, larger gold nanospheres have a larger absorption cross‐section and magnitude of extinction (Jain et al., 2006). So for assays that reply on the absorption property, such as LSPR‐based as well as many colorimetric assays like LFAs, larger AuNPs have a better chance of obtaining a higher sensitivity relative to smaller AuNPs. Similarly, gold nanoshells tend to have a higher sensitivity than gold nanospheres. However, this assumption always needs to be tested in each assay development as many other factors could influence the ultimate LOD as well. In one study, Khlebtsov et al. (2019) evaluated the size‐dependent LODs of an ideal colorimetric LFIA, assuming that one analyte molecule corresponds to one AuNP captured in the test zone, and suggest that the expected LFIA sensitivity can increase for larger AuNP sizes like d−1 (d for diameter). In another study, Kim et al. (2016) analyzed size‐dependent LFA performance for HbsAg detection using AuNPs in the size range of 34–138 nm and found 43 nm AuNP exhibited the best performance. However, in an LSPR‐based HbsAg sensing assay, Kim et al. (2018) found 15 nm AuNPs have a lower LOD than AuNPs with larger sizes (30 nm, 50 nm). For assays that are not related to the optical property of AuNPs, size of AuNPs might play a different role in determining the sensitivity of an assay. For example, Park et al. developed graphene/AuNP hybrids for norovirus detection based on the catalytic efficiency of NPs. They found the 10 nm AuNP showed the lowest LOD of 92.7 pg/ml from AuNPs in a size range of 10–500 nm likely due to the large surface‐to‐volume ratio (Ahmed et al., 2017). Overall, to select the size of AuNPs for SARS‐CoV‐2 detection assays, one‐size‐fits‐all approaches would not be ideal. One needs to optimize the size of AuNPs in each assay developed to achieve the best performance.

In terms of shape, there is no doubt that spherical AuNPs are among the most studied ones due to the ease of synthesis. However, other shapes of AuNPs are worth studying when a higher sensitivity or a different sensing strategy is desired but beyond the reach of gold nanospheres. Among non‐spherical AuNPs, gold nanorods (AuNRs) are often chosen for biomedical applications due to their unique characteristics such as large absorption cross‐section, high extinction coefficient, and more interestingly, AuNRs display two separate LSPR in the visible/near‐IR spectral range, due to transverse and longitudinal oscillations of conduction electrons. Importantly, this longitudinal band can be tuned by adjusting the aspect ratio of AuNRs. AuNPs are commonly used as FRET receptors for biosensors (Adegoke et al., 2017; Nasrin et al., 2018; Tsang et al., 2016). As AuNRs have two absorption bands, they are superior to the spherical AuNPs in multiplex sensing. For example, Zeng et al. reported a FRET nanosensor using green and red quantum dots (QDs) and tuned AuNRs so that the emission spectra of QDs overlap with the two absorption bands of AuNRs respectively. With this design, the researchers can simultaneously detect two different HBsAgs (Zeng et al., 2012). In another study, Xu et al. reported an H5N1 virus biosensor utilizing the sharp edges of highly uniform gold nanobipyramids (Au NBPs) that displayed a color change upon silver deposition triggered by virus antigen binding. This alkaline phosphatase‐based ELISA strategy showed a LOD as low as 1 pg/ml. The vivid colors of the proposed sensing strategy also enabled semiquantitative detection of the analytes with the naked eye (Xu et al., 2017). This sensing strategy would not succeed without the recent progress on the synthesis of highly homogeneous Au NBPs, which indicates the importance of the design of the shape of AuNPs. Nonetheless, the selection of non‐spherical AuNPs may not be necessarily related to the unique physical property associated with the shape. Nikbakht et al. (2014) reported a colorimetric influenza A virus M gene biosensor using AuNRs, which formed aggregates during DNA amplification due to the interaction between LAMP DNA and the positive surface capping agents cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, a critical surfactant used in AuNRs synthesis.

It is worth noting that although higher sensitivity is always the goal of any sensor, for better clinical and commercial translation, it is critical to balance the trade‐off between sensitivity, complexity, cost‐effectiveness, portability, and stability of the AuNP‐based colloidal system. The actual application setting (e.g., laboratory, hospital, home) is also an important factor one should not overlook during assay development.

3.2. Design of target molecules

The selection of targets for detecting SARS‐CoV‐2 is different between nucleic acid testing and antibody testing. A summary of representative targets is listed in Table 3. For nucleic acid testing, targets are selected from key functional genes and genes encoding structural proteins. There are four structural proteins encoded by a coronavirus genome: Spike surface glycoprotein (S), envelope protein (E), matrix protein (M), and nucleocapsid protein (N). Besides these structural proteins, another three genes have also been used for nucleic acid‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 detection: ORF1ab gene, ORF1b‐nsp14 gene, and RdRp gene (Udugama et al., 2020). ORF1ab gene encodes replicase polyprotein 1ab. ORF1b‐nsp14 gene encodes nonstructural protein 14. RdRp gene encodes RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase. These proteins play an important role in virus RNA transcription and replication (Wu et al., 2020).

TABLE 3.

Representative targets for diagnosing SARS‐CoV‐2

| Target | Type of test | Function |

|---|---|---|

| ORF1ab gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding replicase polyprotein 1ab |

| ORF1b‐nsp14 gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding nonstructural protein 14 |

| RdRP gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase |

| S gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding spike glycoprotein (structural) |

| E gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding small envelope protein (structural) |

| M gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding matrix protein (structural) |

| N gene | Nucleic acid | Encoding nucleocapsid protein (structural) |

| Spike protein RBD domain | Antibody | Bind to ACE2 receptor |

Abbreviations: ACE2, angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2; RBD, receptor binding domain.

For antibody testing, the Spike protein RBD domain is believed to be the most common target to choose. Spike is a surface protein on viral capsid that mediates cell entry by binding to host cell receptor angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Functionally, the Spike protein is divided into two subunits. S1 subunit, including the receptor‐binding domain (RBD), is responsible for receptor binding. S2 subunit is responsible for cell membrane fusion. Although the full Spike protein could be used as an antigen for antibody detection, the RBD domain is likely the antigen giving the best sensitivity and specificity (Jiang et al., 2020). Interestingly, Ventura and coworkers developed a SARS‐CoV‐2 testing by mixing 1:1:1 of three antibody‐AuNP conjugates targeting three surface proteins of SARS‐CoV‐2 (spike, envelope, and membrane). This assay reported a detection limit approaching that of the real‐time PCR, although both the ratio and the size of AuNPs are still susceptible to optimization to allow one to push even further the LOD. It is worth noting that because this biosensor relies on its sensitivity to the virion rather than to its content (RNA), it offers a powerful tool to quantify the viral load, and is apt to assess the actual degree of infectiveness of a specimen, a nontrivial issue in diagnostic assays in virology (Ventura et al., 2020).

3.3. Conjugation strategies

Passive adsorption and covalent conjugation are the two most commonly used strategies to conjugate ligands such as antibodies, proteins, aptamers, or DNA/RNA oligos to AuNPs. Passive adsorption is relatively straightforward and also effective in conjugating certain ligands to AuNPs. However, this method has several drawbacks. These include desorption of the ligands from the gold surface over time under certain conditions (e.g., salt and pH changes). Any detachment of ligands from the particle surface can result in compromised assay sensitivity, susceptible particle stability, and even false‐positive testing results. On the other side, covalent conjugation represents a popular conjugation strategy for AuNPs thanks to the ease of gold‐thiol chemistry. Besides that, covalent conjugation also favors several benefits. First, covalent conjugates offer increased stability in difficult sample conditions (high salt or detergent concentrations), which is important for many assays that deal with clinical samples. Second, the ligand‐to‐particle ratio can be precisely controlled, which is important for optimizing assay sensitivity, providing reproducible conjugates and reliable quantitation of analytes. Recently, a photochemical immobilization technique (PIT), which involves using a 254 nm UV light to disrupt the disulfide bridges located next to the tryptophan residues, has been applied for surface functionalization of antibodies to AuNPs for SARS‐CoV‐2 detection (Ventura et al., 2020). PIT not only always exposed Fab to make AuNP highly “reactive,” but also avoided using any linker (e.g., protein A), the latter being detrimental for the plasmonic interactions among AuNPs on which the colorimetric biosensor is based (Ventura et al., 2020). In another study, Wang et al. (2019) developed an AuNP/RNA conjugate through a dithiocarbamate functional group, which showed improved stability and less premature ligand release over using traditional monothiol linker at high ionic strength and in the presence of reducing reagents. Other conjugation strategies such as antibody orientation, with or without PEG backfilling, length of PEG chains or other biolinkers, ligand coverage on AuNP, and so on, all have implications of LOD for the assay development (Avvakumova et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2019; Tam et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2013).

3.4. Assay formats

COVID‐19 testings include nucleic acid‐based testing and antibody‐based testing. Despite nucleic acid testing being the gold standard for diagnosing COVID‐19, antibody testing can be used as a good complementary test for several reasons. First, although qRT‐PCR is the tried‐and‐true method for nucleic acid testing, it can hardly meet needed demands due to the rapid growth of the disease, limited accessibility of the instruments, and lengthy testing time. Second, for suspected cases where nucleic acid detection was negative, antibody testing could help to determine the status of the infection. For example, if it tests positive, it could mean that the patient has been exposed to, and recovered from SARS‐CoV‐2 or possibly a related coronavirus. These tests are important in the fight against the pandemic by providing information on disease prevalence and the frequency of asymptomatic infection, and also by identifying potential donors of “convalescent plasma,” an approach in which blood plasma containing antibodies from a recovered individual serves as a therapy for an infected patient with a severe or immediately life‐threatening disease. Importantly, we must point out that a negative antibody test not necessarily indicates negative current infection. It might just be in the early stage as antibodies do not show up for 1–3 weeks or even longer after infection and some people may not develop antibodies at all.

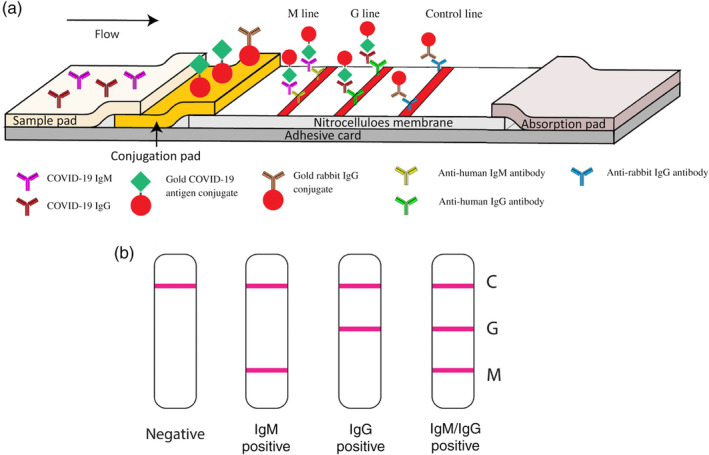

So far, LFA is no doubt the mainstream assay format for AuNP‐based IVD due to portability, rapidity, ease of use, and low cost. This is explicitly supported by the fact that all AuNP‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 tests are lateral flow assays (Table 2). Li et al. designed an AuNP‐based LFIA strip that can simultaneously diagnose IgG and IgM for COVID‐19 (Figure 18). There were two test lines under the control line, the G line and M line, which were immobilized with mouse anti‐human IgG and mouse anti‐human IgM for IgG and IgM detection, respectively. C line is the control line, which is immobilized with anti‐rabbit antibodies. The conjunction pad is dispensed with two types of conjugated AuNP: one is COVID‐19 antigen‐AuNP for binding potential with COVID‐19 IgG/IgM antibodies, and the other is rabbit IgG‐AuNP for binding to the control line. The main benefit of simultaneous IgG and IgM testing is that it can potentially recognize a COVID‐19 infection earlier as IgM antibodies usually appear before IgG. Time is vital in the race against COVID‐19. Moreover, simultaneous IgG/IgM testing can have a higher sensitivity and specificity than IgG or IgM testing alone. The antibody level in blood is fluctuating during the period of infection. IgM appears early but is not lasting. IgG has a higher binding affinity to antigen and is more abundant than IgM, meaning IgG testing usually has a higher sensitivity and specificity. Overall, combined IgG/IgM testing can rule out potential false negatives. The authors were able to achieve a sensitivity of 88.66% and specificity of 90.63% over 397 positive and 128 negative clinical samples and a 100% detection consistency in fingerstick blood, serum, and plasma of venous blood. However, the detection limit of this assay and different‐sized AuNPs (other than 40 nm) were not studied.

FIGURE 18.

Schematic illustration of rapid SARS‐CoV‐2 IgM‐IgG combined antibody test. (a) Schematic diagram of the detection device. (b) An illustration of different testing results, C: control line; G: IgG line; M: IgM line. Reprinted with permission from Li et al. (2020). John Wiley & Sons, Inc

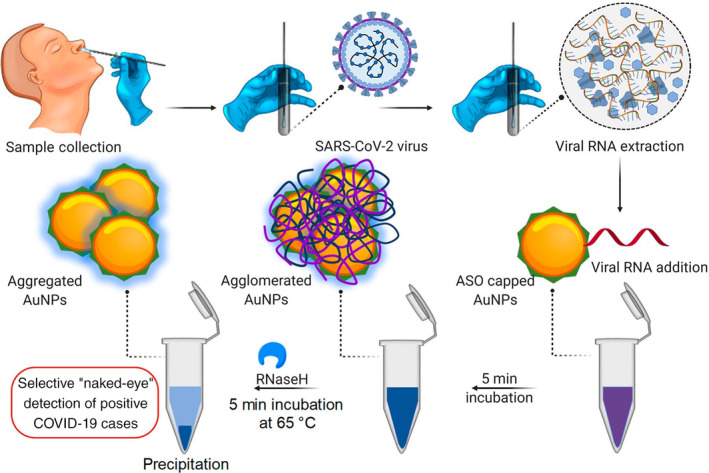

Antibody‐based testing is certainly helpful in evaluating past COVID‐19 infections; however, it is incapable by itself of identifying whether an individual is experiencing a current infection. Moreover, although adding IgM detection could potentially help to diagnose COVID‐19 earlier than IgG detection only, it still takes several days to weeks after infection for a patient to develop a detectable antibody response. Therefore, AuNP‐based nucleic acid testing is highly valuable and needed for an urgent unmet need in COVID‐19 diagnosis. Recently, Moitra et al. developed a colorimetric assay based on 10 nm AuNPs, coated with antisense oligonucleotides specific for N‐gene of SARS‐CoV‐2, for rapid (⁓5 min after RNA isolation) and selective detection. This assay reported a LOD of 0.18 ng/μl with a tested dynamic range of 0.2–3 ng/μl by measuring OD660. The authors further adapted the assay to a visual “naked‐eye” detection by adding a 5 min incubation step with RNase H at 65°C (Figure 19). This allows a layman to easily detect the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 without the requirement of any sophisticated instrumental techniques (Moitra et al., 2020). Another study by Qiu et al. (2020) reported a gold nanoisland‐based nucleic acid sensor specific for the SARS‐CoV‐2 E gene with a LOD of 0.22 pM.

FIGURE 19.

Schematic representation for the selective naked‐eye detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA mediated by the suitably designed ASO‐capped AuNPs. Reprinted with permission from Moitra et al. (2020). American Chemical Society

Although great efforts and progress have been made for the development of AuNP‐based assays, additional potential directions could be explored to better meet the COVID‐19 detection need. For example, an isothermal amplification approach could be integrated into nucleic acid testing to meet the sensitivity requirement for real samples containing only trace amounts of the virus during the early stage of infection, which was the main reason for many false negatives. Microfluidics technology is well suited for POC diagnostics, which needs fewer samples and reagents and is capable of handling high throughput samples. Although AuNP‐based microfluidic assays have been reported for viral detection, in the case of COVID‐19 detection, it is yet to be seen. In addition, device sensitivity and specificity could be further improved in combination with other nanotechnology‐based detection strategies. For instance, our group has demonstrated significantly improved capture efficiency of biomarkers in blood using multivalent binding effect mediated by dendrimer nanoparticles (Myung et al., 2018; Poellmann et al., 2020). Multivalency‐induced binding affinity enhancement has also been reported in AuNPs (Riley & Day, 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Overall, we expect more AuNP‐based COVID‐19 sensors with the ASSURED criteria (i.e. affordable, sensitive, specific, user‐friendly, rapid and robust, sophisticated equipment‐free, delivered to the end‐users) will be developed in the near future.

4. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

AuNP‐based sensors have gained substantial interest in both academia and industry in the past two decades. In this review, we described the recent advances in AuNP‐based virus detection. Furthermore, in light of the current outbreak of the COVID‐19 pandemic, we particularly discussed considerations for the design of AuNP‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 testings. These examples prove that AuNP‐based sensors can offer great advantages over conventional methods such as ELISA, PCR, western blot, and many others. Although much progress has been made, many key parameters need to be considered and optimized before AuNP‐based diagnostics can realize their full potential in future applications and advance current technologies beyond conception. (1) High sensitivity and specificity. There is no doubt that high sensitivity will always be the goal of AuNP‐based IVDs considering the high sensitivity of many other conventional assays (e.g., ELISA, RT‐PCR) and the low abundance of many analytes. Importantly, specificity should be another critical factor taken into account during the assay development phase. Assays that demonstrate high specificity in distinguishing analytes from their close similarities (e.g., serotypes) hold more promise for success in future markets. (2) Portability/wearability. Portability is of crucial importance to POC and wearable IVDs. Portability means the size and weight of the relevant equipment are favorable for carrying and the assay can maintain functions in ambient conditions. AuNP conjugates are known for good stability and robustness as the LFA strip is a good example. AuNP‐based assays that can be miniaturized and require low maintenance storage conditions will hold more promise towards portability. Wearability will be favorable for long‐term monitoring. (3) Quantifiability. Quantitative assays can not only help to exclude false positives/negatives resulting from subjective judgment, but also help to improve the LOD. (4) Mass production. Mass production means the IVD manufacture needs to meet the standardization requirement among batches. AuNPs are known for their scalable and tunable synthesis. However, better control and reproducibility of the AuNP bioconjugation process need to be addressed. (5) Smart networking. With the fast development of smart devices, more and more technologies (e.g., phones, TV, cars, etc.) are becoming smart, and so are IVDs. One of the future directions for AuNP‐based IVDs development is to integrate with a device (e.g., smartphone) to aid with reading, reporting the results of the diagnosis, and interacting with their care providers. (6) High‐throughput. High‐throughput capability is of critical importance in situations that deal with massive samples, such as during an epidemic or pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jianxin Wang: Conceptualization (equal); writing – original draft (lead). Adam Drelich: Writing – original draft (supporting). Caroline Hopkins: Writing – original draft (supporting). Sandro Mecozzi: Funding acquisition (supporting). Lingjun Li: Funding acquisition (supporting). Glen Kwon: Funding acquisition (supporting). Seungpyo Hong: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (lead); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

RELATED WIREs ARTICLES

Biomedical applications of gold nanomaterials: opportunities and challenges

Single and multiple detections of foodborne pathogens by gold nanoparticle assays

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been partially supported by the funds of the Wisconsin Center for NanoBioSystems, provided from the School of Pharmacy and UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) of the University of Wisconsin‐Madison (UW‐Madison). S.H. acknowledges financial support from National Science Foundation (grant # DMR‐1808251) and Milton J. Henrichs Chair Professorship. L.L. acknowledges financial support by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants RF1AG052324 and R01DK071801, and a Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professorship and Charles Melbourne Johnson Distinguished Chair Professorship with funding provided by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and UW‐Madison School of Pharmacy.

Wang, J. , Drelich, A. J. , Hopkins, C. M. , Mecozzi, S. , Li, L. , Kwon, G. , & Hong, S. (2022). Gold nanoparticles in virus detection: Recent advances and potential considerations for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing development. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology, 14(1), e1754. 10.1002/wnan.1754

Edited by: Andrew Wang, Associate Editor and Gregory Lanza, Co‐Editor‐in‐Chief

Funding information National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant/Award Numbers: RF1AG052324, R01DK071801; Division of Materials Research, Grant/Award Number: 1808251; UW‐Madison School of Pharmacy; Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation; Milton J. Henrichs Chair Professorship; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: DMR‐1808251; Wisconsin Center for NanoBioSystems

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Adegoke, O. , Morita, M. , Kato, T. , Ito, M. , Suzuki, T. , & Park, E. Y. (2017). Localized surface plasmon resonance‐mediated fluorescence signals in plasmonic nanoparticle‐quantum dot hybrids for ultrasensitive Zika virus RNA detection via hairpin hybridization assays. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 94, 513–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. R. , Kim, J. , Suzuki, T. , Lee, J. , & Park, E. Y. (2016). Enhanced catalytic activity of gold nanoparticle‐carbon nanotube hybrids for influenza virus detection. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 85, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. R. , Mogus, J. , Chand, R. , Nagy, E. , & Neethirajan, S. (2018). Optoelectronic fowl adenovirus detection based on local electric field enhancement on graphene quantum dots and gold nanobundle hybrid. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 103, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. R. , Takemeura, K. , Li, T. C. , Kitamoto, N. , Tanaka, T. , Suzuki, T. , & Park, E. Y. (2017). Size‐controlled preparation of peroxidase‐like graphene‐gold nanoparticle hybrids for the visible detection of norovirus‐like particles. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 87, 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, N. , Hallaj, R. , & Salimi, A. (2017). A highly sensitive electrochemical immunosensor for hepatitis B virus surface antigen detection based on Hemin/G‐quadruplex horseradish peroxidase‐mimicking DNAzyme‐signal amplification. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 94, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvakumova, S. , Pandolfi, L. , Soprano, E. , Moretto, L. , Bellini, M. , Galbiati, E. , Rizzuto, M. A. , Colombo, M. , Allevi, R. , Corsi, F. , Sánchez Iglesias, A. , & Prosperi, D. (2019). Does conjugation strategy matter? Cetuximab‐conjugated gold nanocages for targeting triple‐negative breast cancer cells. Nanoscale Advances, 1(9), 3626–3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangel, P. , Sobarzo, A. , Parolo, C. , Miller, B. S. , Howes, P. D. , Gelkop, S. , Lutwama, J. J. , Dye, J. M. , McKendry, R. A. , Lobel, L. , & Stevens, M. M. (2018). A serological point‐of‐care test for the detection of IgG antibodies against Ebola virus in human survivors. ACS Nano, 12(1), 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, S. A. , Sobral‐Filho, R. G. , Aoki, P. H. B. , Constantino, C. J. L. , & Brolo, A. G. (2018). Zika immunoassay based on surface‐enhanced Raman scattering nanoprobes. ACS Sensors, 3(3), 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand, R. , & Neethirajan, S. (2017). Microfluidic platform integrated with graphene‐gold nano‐composite aptasensor for one‐step detection of norovirus. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 98, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chayan, S. G. , Kim, D. , Hwang, J. , Choi, Y. , Hong, J. W. , Kim, J. , Lee, M.‐H. , Hwang, M. P. , & Choi, J. (2019). Enhanced detection of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus via lateral flow chip and fluorometric biosensors based on self‐assembled protein nanoprobes. ACS Sensors, 4(11), 2937–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]