Abstract

Objective

Research investigating the effects of COVID‐19 on eating disorders is growing rapidly. A comprehensive evaluation of this literature is needed to identify key findings and evidence gaps to better inform policy decisions related to the management of eating disorders during and after this crisis. We conducted a systematic scoping review synthesizing and appraising this literature.

Method

Empirical research on COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorder severity, prevalence, and demand for treatment was searched. No sample restrictions were applied. Findings (n = 70 studies) were synthesized across six themes: (a) suspected eating disorder cases during COVID‐19; (b) perceived pandemic impacts on symptoms; (c) symptom severity pre versus during the pandemic; (d) pandemic‐related correlates of symptom severity; (e) impacts on carers/parents; and (f) treatment experiences during COVID‐19.

Results

Pandemic impacts on rates of probable eating disorders, symptom deterioration, and general mental health varied substantially. Symptom escalation and mental health worsening during―and due to―the pandemic were commonly reported, and those most susceptible included confirmed eating disorder cases, at‐risk populations (young women, athletes, parent/carers), and individuals highly anxious or fearful of COVID‐19. Evidence emerged for increased demand for specialist eating disorder services during the pandemic. The forced transition to online treatment was challenging for many, yet telehealth alternatives seemed feasible and effective.

Discussion

Evidence for COVID‐19 effects is mostly limited to participant self‐report or retrospective recall, cross‐sectional and descriptive studies, and samples of convenience. Several novel pathways for future research that aim to better understand, monitor, and support those negatively affected by the pandemic are formulated.

Keywords: carers, COVID‐19, eating disorders, machine learning, mental health, open science, scoping review, systematic review, telehealth, treatment

Resumen

Objetivo

La investigación que se hace sobre los efectos de COVID‐19 en los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria está creciendo rápidamente. Se necesita una evaluación exhaustiva de esta literatura para identificar los hallazgos clave y evidenciar las brechas para informar mejor las decisiones de políticas públicas relacionadas con el manejo de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria durante y después de esta crisis. Se realizó una revisión sistemática del alcance que sintetizó y valoró esta literatura.

Método

Se buscó investigación empírica sobre los impactos de COVID‐19 en la gravedad, prevalencia y demanda de tratamiento de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria. No se aplicaron restricciones a la muestra. Los hallazgos (n = 70 estudios) se sintetizaron en seis temas: (1) casos sospechosos de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria durante COVID‐19; (2) impacto percibido en los síntomas; (3) gravedad de los síntomas antes versus durante la pandemia; (4) correlatos relacionados con la pandemia de la gravedad de los síntomas; (5) impactos en los cuidadores/padres; (6) experiencias de tratamiento durante COVID‐19.

Resultados

El impacto de la pandemia en las tasas de probables trastornos de la conducta alimentaria, deterioro de los síntomas y salud mental en general variaron sustancialmente. La escala de síntomas y el empeoramiento de la salud mental durante y debido a la pandemia fueron reportados comúnmente, y los más susceptibles incluyeron casos confirmados de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria, poblaciones en riesgo (mujeres jóvenes, atletas, padres / cuidadores) e individuos con altos niveles de ansiedad o con miedo de COVID‐19. Surgió alguna evidencia de una mayor demanda de servicios especializados en trastornos de la conducta alimentaria durante la pandemia. La transición forzada al tratamiento en línea fue un desafío para muchos, sin embargo, las alternativas de telesalud parecían factibles y efectivas. Conclusiones. La evidencia de los efectos de COVID‐19 se limita principalmente al autoinforme de los participantes o al recuerdo retrospectivo, los estudios transversales y descriptivos, y las muestras de conveniencia. Se formulan varias vías novedosas para futuras investigaciones que tienen como objetivo comprender, monitorear y apoyar mejor a aquellos que fueron afectados negativamente por la pandemia.

1. INTRODUCTION

The emergence of the novel coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) has led to major disruptions in functioning of established healthcare, education, social, and economic systems (Barlow, van Schalkwyk, McKee, Labonté, & Stuckler, 2021; Blumenthal, Fowler, Abrams, & Collins, 2020). Countries across the world have implemented strict preventative measures to slow the spread of infection, including mandated stay‐at‐home orders and social distancing policies. These measures have profoundly impacted employment, schooling, and the global economy (McKee & Stuckler, 2020), and have also adversely impacted the mental health of many individuals (Murphy, Markey, O'Donnell, Moloney, & Doody, 2021; Panchal et al., 2021; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Such challenges have encouraged researchers, policy makers, and healthcare professionals to deeply consider the direct and indirect consequences of COVID‐19 under circumstances of significant logistical challenges (Weissman, Klump, & Rose, 2020), time pressures, and a rapidly evolving evidence base (Liu et al., 2020).

Within the eating disorders field, researchers have raised concern that restrictions to daily activities, increased isolation, threats of food shortages, increased screen time, and disruptions to mental health care may exacerbate symptom severity, incidence, and demand for treatment (Rodgers et al., 2020; Touyz, Lacey, & Hay, 2020; Weissman, Bauer, & Thomas, 2020). A growing number of studies conducted during the pandemic have reported a worsening of eating disorder symptoms and syndromes in a variety of population groups (e.g., Keel et al., 2020; Miniati et al., 2021; Phillipou et al., 2020; Sideli et al., 2021; Spigel et al., 2021). Evidence also indicates that the exacerbation of clinical symptoms has added further strain to existing healthcare systems, with the number of specialist referrals and first‐ever admissions purportedly increasing (Hansen, Stephan, & Menkes, 2021; Shaw, Robertson, & Ranceva, 2021). However, the rapid rate at which research related to COVID‐19 impacts is being published has led to serious concerns that the quality of evidence has markedly declined during this period (Jung et al., 2021). Thus, a careful, systematic appraisal of the rapidly evolving evidence pertaining to COVID‐19 and eating disorders is critical to identify key literature gaps, highlight priority areas for future research, and inform policy decisions related to the management of eating disorders during and beyond the pandemic.

The aim of this study was to therefore conduct a systematic scoping review to locate, examine, and summarize the existing literature on COVID‐19 impacts and eating disorders. Based on evident gaps and insights identified in this review, a second aim was to provide concrete recommendations to guide further research in this field.

2. METHOD

A scoping review was selected because its methodology is a widely adopted approach in broad fields of research that are rapidly evolving with emerging evidence (Munn et al., 2018), as is the case of COVID‐19 and eating disorders. Scoping reviews are highly valuable as a form of research synthesis with the goal to map the literature on a particular topic; they provide an opportunity to identify key concepts and themes, gaps in knowledge, and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policy‐making, and research efforts (Munn et al., 2018). This systematic scoping review was guided by the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) five‐step process, including (a) establishing the research question; (b) identifying relevant studies; (c) selecting appropriate studies; (d) mapping the data; and (e) arranging, summarizing, and communicating outcomes. Our scoping review was also guided by the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018).

2.1. Search strategy and study selection

The primary search strategy (last search in August 2021) involved searching the PsycINFO, Medline, and Web of Science databases. The following terms were combined and searched for in the title, abstract, and keywords: (“eating disorder*” “eating pathology” “disordered eating” anorexi* bulimi* “binge‐eating disorder” “binge eat*” “loss of control eating” purging “compulsive exercise” “driven exercise” “self‐induced vomit*” “eating disturbance*” “dietary restriction” OSFED “other specified feeding”) and (COVID‐19 SARS‐CoV‐2 “Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus” 2019nCoV HCoV‐19). Reference lists of included papers were also searched to identify any additional studies.

Once all records obtained through databases were combined into a single Endnote library, duplicates were removed. Title and abstracts were then screened by the first author to identify potentially eligible studies. Full texts of articles were then read by the first author to determine whether full inclusion criteria were met.

Studies were included if they were peer‐reviewed empirical reports investigating the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on eating disorders. Impacts on symptoms, mental health and wellbeing, help‐seeking, service utilization, and treatment experiences were considered eligible for inclusion. No sample restrictions were applied. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on the impact on risk factors (e.g., body image, negative affect), were qualitative reports or case studies, and were published in languages other than English. While we acknowledge the importance of preprints as a valuable form of evidence, we made an a priori decision to exclude preprints because (a) there are no established guidelines for how to systematically search, locate and evaluate them; and (b) it is possible that significant changes may arise from a preprint version to the final, peer‐reviewed version.

2.2. Data extraction

A coding template was developed to extract necessary data from included studies. The following data were extracted: authors, design, data collection date, county, sample size and description, key findings, and other comments or limitations. Authors J.L. and M.M. extracted these data. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

2.3. Data synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of included studies, a qualitative synthesis was performed on six broad themes outlined in Section 3. Themes were developed after extensive discussion among the authors, following completion of data extraction.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

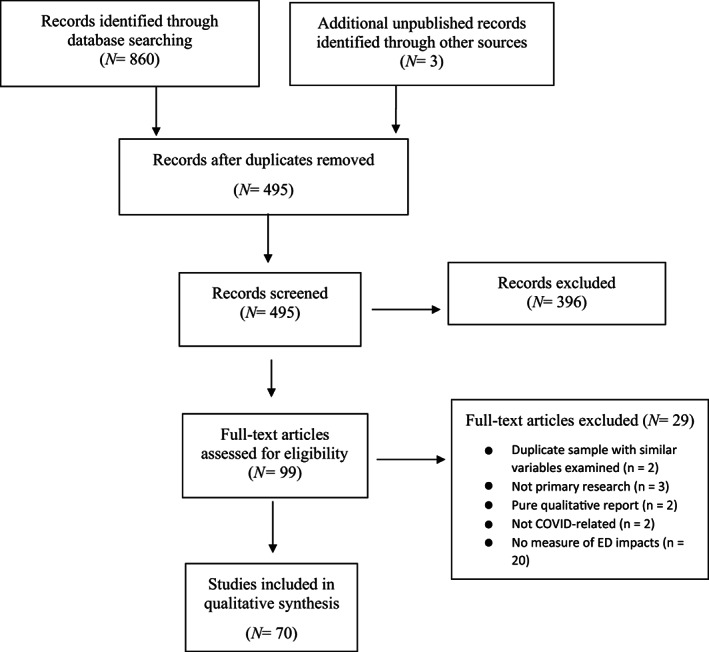

The search resulted in 860 records, and an additional three papers were identified through reference lists. Of these, 99 were included for full text review, resulting in a total of 70 included papers (see Figure 1). Study characteristics of these 70 papers are included in Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Flow‐chart of literature search

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and findings summary of studies that sampled a non‐clinical cohort (individuals without an eating disorder)

| Study | Design | Country | Data collection | Sample description | Brief summary of relevant findings | Additional comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Aldhuwayhi et al., 2021) | Cross | Saudi Arab | Unclear | 296 adult dentists (30% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Alessi et al., 2020) | Cross | Braz | Unclear |

120 adults with type 1/2 diabetes (56% women). 86% white |

|

|

| (Athanasiadis et al., 2021) | Cross | US | Apr‐20 |

208 adult bariatric surgery patients (86% female). 86% white; 12% black; 1% Latino/Hispanic |

|

|

| (Baceviciene & Jankauskiene, 2021) | Long (retro) | US |

pre‐pandemic Oct‐19 During pandemic Feb‐21 |

230 university students (79% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Breiner, Miller, & Hormes, 2021) | Cross | US | Apr‐May20 | 158 community‐based adults (91% women). 90% white; 5% Hispanic; 6% Asian; 0.6% American Indian; 0.6% native American |

|

|

| (Buckley, Hall, Lassemillante, & Belski, 2021) | Cross | Aus | Apr‐May‐20 | 204 current/former athletes (85% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Calugi et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | Italy | June‐Oct‐20 |

206 adults (70% female) who completed CBT‐OB prior to the pandemic & matched control sample (70% female) who completed CBT‐OB prior to pandemic (70% women); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Cecchetto, Aiello, Gentili, Ionta, & Osimo, 2021) | Cross | Italy | May‐20 | 365 community‐based adults (73% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Chan & Chiu, 2021) | Cross | China | Apr‐20 | 316 community‐based adults (71% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Christensen et al., 2021) | Cross | US |

Prelock Dec‐Mar‐20 During lock Apr‐20 |

Cohort 1 of 222 university students (73% women). Cohort 2 of 357 university students (78% women); 84% white; 3% black; 1% American Indian; 5% Asian; 5% mixed race |

|

|

| (Coimbra, Paixão, & Ferreira, 2021) | Cross | Port | April – May‐20 | 508 community‐based adult women. Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Colleluori, Goria, Zillanti, Marucci, & Dalla Ragione, 2021) | Cross | Italy | March – May‐20 | 76 healthcare providers who treated patients with ED during pandemic. Gender/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Czepczor‐Bernat, Swami, Modrzejewska, & Modrzejewska, 2021) | Cross | Pol | Dec20‐Feb‐21 |

671 community‐based adult women; 99% white. |

|

|

| (De Pasquale et al., 2021) | Cross | Italy | Mar‐20‐Feb‐21 | 469 university students (53% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Flaudias et al., 2020) | Cross | Fran | Mar‐20 | 5,738 university students (74% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Guo et al., 2020) | Long (prosp) | China | Mar‐20 | 254 carers of people with ED (84% female) and 254 carers of healthy controls (84% female); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Haddad et al., 2020) | Cross | Leb | Apr‐20 |

Community‐based adults (n = 228; 58% female) and individuals attending weight loss clinics (n = 177; 40%). Race/ethnicity = N/A |

|

|

| (Jordan et al., 2021) | Cross | US | Jul‐Sept‐20 |

140 community‐based adult carers (88% female) 84% white; other races/ethnicities N/R |

|

|

| (Keel et al., 2020) | Long (pros) | US |

T1 Jan‐20 T2 Apr‐20 |

90 university students (87% female) 78% White; 22% Latino; 12% Black; 4% Asian; 1% American Indian |

|

|

| (Kim et al., 2021) | Cross | US |

Pre‐pandemic Oct‐19 During pandemic May‐20 |

Pre‐pandemic cohort 1 n = 8,613 university students (73% women); 72% white; 8% black 9%; Asian; 1% American Indian; 1% native; Hawaiian; 8% mixed race During pandemic cohort 2 = 4,970 university students (68% women); 74% white; 5% black 14%; Asian; 1% American Indian; 1% native Hawaiian; 4% mixed race |

|

|

| (Koenig et al., 2021) | Cross | Germ |

Pre‐pandemic Nov18‐Mar20 During pandemic mar‐Aug20 |

Cohort 1 = 324 adolescents (69% female). Cohort 2 = 324 matched adolescents (69% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Kohls, Baldofski, Moeller, Klemm, & Rummel‐Kluge, 2021) | Cross | Germ | Jul‐Aug‐20 | 3,382 university students (70% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Martínez‐de‐Quel, Suárez‐Iglesias, López‐Flores, & Pérez, 2021) | Long (pros) | Spain |

T1 Mar‐20 T2 mar‐Apr‐20 |

161 community‐based adults (37% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Meda et al., 2021) | Long (pros) | Italy |

Prelockdown Oct‐19 During lockdown Apr‐20 After lockdown Jun‐20 |

358 university students (79% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Muzi, Sansò, & Pace, 2021) | Cross | Italy |

Prelockdown Jan‐19/20 During lockdown mar‐May‐20 |

N = 61 pre‐pandemic cohort of adolescents (67% female). During pandemic cohort of adolescents (61% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Phillipou et al., 2020) | Cross | Aus | Apr‐20 | 5,469 community‐based adults (80% women; 184 self‐reporting current ED). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Quittkat et al., 2020) | Cross | Germ | Apr‐May20 | 2,233 community‐based adults (80% women); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Racine, Miller, Mehak, & Trolio, 2021) | Cross | Can | Apr‐Jun‐20 | 877 community‐based adults (74% women); 80% white; 6% Hispanic; 5.7% Chinese; 3.1% south Asian; 2.4% Arab; 2.2% black; 1.6% southeast Asian; 1.5% west Asian; 0.9% Filipino; 0.8% indigenous; 0.6% Japanese; 0.1% native Hawaiian |

|

|

| (Ramalho et al., 2021) | Cross | Port | May‐20 | 254 community‐based adult participants (83% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Robertson et al., 2021) | Cross | UK | May‐Jun‐20 | 264 community‐based adults (78% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Scharmer et al., 2020) | Cross | US | Mar‐Apr‐20 | 295 university students (65% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Simone et al., 2021) | Cross | US | Apr‐May‐20 |

720 community‐based adolescents/adults (62% female/women); 29% white; 24% Asian; 16% Latino/Hispanic; 18% black/African American; 11% mixed |

|

|

| (Thompson & Bardone‐Cone, 2021) | Cross | US | Apr‐20 |

Postpartum adult women (n = 306); 93% white; 8% Latina. Control women (n = 153): 83% white; 8% Latina. |

|

|

| (Troncone et al., 2020) | Cross | Italy | Apr‐20 |

138 youth with type 1 diabetes (52%) and 276 matched controls (59% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Trott, Johnstone, Pardhan, Barnett, & Smith, 2021) | Long (retro) | UK |

Pre‐pandemic Apr‐Jul‐19 During pandemic Aug‐Sept‐20 |

319 adults (84% women); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Wang et al., 2021) | Cross | China | May‐Jul‐20 | 12,186 children (48% girls); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Zhang et al., 2021) | Cross | China | Mar‐Apr‐20 | 315 carers for offspring with ED (79% women) and 315 carers for healthy offspring (80% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Zhou & Wade, 2021) | Long (retro) | Aus |

Pre‐pandemic mar‐Sep‐19 During pandemic Apr‐20 |

Pre‐pandemic n = 41 adult women with body image concerns. During pandemic n = 59 adult women with body image concerns; 88% Caucasian; 6% Asian; 6% other |

|

|

Abbreviations: Aus, Australia; Braz, Brazil; Can, Canada; CBT‐OB, cognitive‐behavior therapy for obesity; Cross, cross‐sectional; EAT, Eating Attitudes Test; ED, eating disorders; EDE‐Q, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; EDI, Eating Disorders Inventory; Fran, France; Germ, Germany; Leb, Lebanon; long (pros), longitudinal prospective design; long (retro), longitudinal retrospective design; N/R, not reported or unclear; Port, Portugal; SEED, Short Evaluation of Eating Disorders; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; WCS, Weight Concern Scale.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and findings summary of studies that sampled a clinical cohort

| Study | Design | Country | Date | Sample | Brief summary of relevant findings | Additional comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Akgül et al., 2021) | Cross | Turk | May–Jun‐20 | 38 adolescents (95% girls); AN‐restrict (68%); AN‐binge‐purge (13%); atypical AN (8%); BN (8%); OSFED (2%); race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Baenas et al., 2020) | Long (retro)) | Spain |

Prelockdown unclear During lockdown Apr‐20 |

74 adult treatment‐seeking patients confirmed via interview (96% women); n = 19 AN; n = 12 BN; n = 10 BED; n = 33 OSFED. race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Branley‐Bell & Talbot, 2020) | Cross | UK | Apr‐20 |

129 community‐based adolescents/adults with current ED or recovering from ED based on self‐report (94% females). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Brothwood, Baudinet, Stewart, & Simic, 2021) | Cross | UK | Mar–Nov‐20 | 14 adolescents with AN and 19 parents participating in an intensive treatment program (93% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Castellini et al., 2020) | Long (retro) | Italy |

Pre‐pandemic Jan–Sept‐19 During pandemic Apr–May‐20 |

74 treatment‐seeking adults with BN/AN confirmed via interview (100% women) 97 healthy controls (100% female); 100% white; other races/ethnicities N/R |

|

|

| (Favreau et al., 2021) | Cross | Germ | Apr–Dec‐20 | 88 individuals with AN and 30 with BN drawn from a large sample of 538 psychiatric inpatients (70% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Fernandez‐Aranda et al., 2020) | Cross | Spain | Jun–Jul‐20 | 127 adults, including 87 in‐patients with an eating disorder (n = 55 AN, n = 18 BN, n = 14 OSFED) and 34 patients with obesity, confirmed by interviews (86% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Giel, Schurr, Zipfel, Junne, & Schag, 2021) | Long (retro) | Germ |

Pre‐pandemic May–Jun‐17 During pandemic May–Jul‐20 |

42 adults with BED who previously participated in an RCT, confirmed via interview (80% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Graell et al., 2020) | Long (retro) | Spain | Mar–May‐20 |

Medical records of children and adolescents with ED seeking treatment before (n = 22) and during the confinement period (n = 22; 100% female). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Hansen et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | NZ |

Pre‐pandemic Jan–Dec‐19 During pandemic 2020 period |

236 electronic records of child, adolescent, and adult inpatient and outpatient admissions pre‐pandemic postpandemic (95% female); 94% European; 6% Māori; 2% other |

|

|

| (Leenaerts, Vaessen, Ceccarini, & Vrieze, 2021) | Long (pros) | Belg | Unclear |

15 adults with BN confirmed via interview (100% women); 87% European 13% Asian |

|

|

| (Levinson, Spoor, Keshishian, & Pruitt, 2021) | Long (pros) | US |

Pre‐pandemic Mar‐2018/2020 During pandemic Mar‐2020–Jan‐2021 |

93 treatment‐seeking adults confirmed via interview (86% women) who received either in‐person or telemedicine treatment (43% AN; 10% BN; 34% OSFED; 9% BED; 2% ARFID); 95% white; 2% black; 1% Asian; 1% mixed race |

|

|

| (Lewis, Elran‐Barak, Grundman‐Shem Tov, & Zubery, 2021) | Cross | Israel | Apr–May‐20 | 63 treatment‐seeking individuals (90% women); 38% AN; 32% BN; 25% BED. race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Lin et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | US |

Pre‐pandemic Jan‐2018–Mar‐2020 During pandemic Apr‐2020–Feb‐2021 |

Service utilization data were analyzed (no participant information provided) |

|

|

| (Machado et al., 2020) | Long (retro) | Port |

Pre‐pandemic unclear During pandemic Apr–May‐20 |

43 adults (95% women) patients (46% AN; 32% BN; 5% BED; 16% OSFED). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Mansfield et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | UK |

Pre‐pandemic Jan‐2017/2019 During pandemic Aug‐20 |

> 10 million electronic records of adult health care contacts (50% women); 49% white; 5% south Asian; 3% black; 2% other; 1% mixed |

|

|

| (Monteleone et al., 2021) | Cross | Italy | Jun‐20 |

312 adults with ED confirmed via interview (96% women); 57% AN; 27% BN; 15% BED; 7% OSFED. race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Pensgaard, Oevreboe, & Ivarsson, 2021) | Long (pros) | Italy |

T1 Mar‐Apr‐2020 T2 Jun‐2020 |

40 treatment‐seeking patients confirmed by interview (98% women); n = 22 AN; n = 22 BED; n = 15 BN. Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Plumley, Kristensen, & Jenkins, 2021) | Long (pros) | UK | Unclear |

9 patients with AN undergoing day‐patient treatment virtually (89% women); 77% white; other races/ethnicities N/R |

|

|

| (Raykos, Erceg‐Hurn, Hill, Campbell, & McEvoy, 2021) | Long (pros) | Aus | Mar–Apr‐20 | 25 treatment‐seeking patients (93% women) confirmed via interview; 48% AN; 20% BN; 28% OSFED; 4% UFED. 70% Anglo‐European‐Australian; other races/ethnicities N/R. |

|

|

| (Richardson, Patton, Phillips, & Paslakis, 2020) | Long (retro) | Can |

Pre‐pandemic Mar–Apr‐2018/2019 During pandemic Mar–Apr‐20 |

All individuals (87% female) who contacted NEDIC through the helpline or instant chat function (demographic info N/R). |

|

|

| (Schlegl, Maier, et al., 2020) | Cross | Germ | May‐20 | 159 former inpatients with AN (100% women). Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Schlegl, Meule, et al., 2020) | Cross | Germ | May‐20 |

55 former inpatients with BN confirmed via interview (100% female) Race/ethnicity = N/A |

|

|

| (Shaw et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | UK |

Pre‐pandemic Mar–Jul‐19 During pandemic Mar–Jul‐20 |

Service evaluation conducted at the eating disorder young person service (UK), including 12 adolescent patients with an ED, 19 parents/carers, and 12 staff members. Gender /race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Spettigue et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | Can |

Pre‐pandemic Apr–Oct‐19 During pandemic Apr–Oct‐20 |

91 adolescents (43 pre‐pandemic and 48 during pandemic) with an ED (83% female); ~85% AN. Race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Spigel et al., 2021) | Cross | US | Jul‐20 |

73 treatment‐seeking young people with self‐reported ED (93% female); white = 79%; Asian = 7%; Hispanic = 6%; black = 1% mixed race = 6%; other = 1%. |

|

|

| (Stewart et al., 2021) | Cross | UK | May–Jul‐20 | 53 adolescents with an ED (AN/OSFED), 75 parents, and 23 clinicians. Gender /race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Taquet, Geddes, Luciano, & Harrison, 2021) | Long (retro) | US |

Pre‐pandemic 2017–2020 During pandemic 2020–2021 |

> 5 million electronic health records of adolescent patients (55% female; 8,471 diagnoses with an ED during the pandemic period). |

|

|

| (Termorshuizen et al., 2020) | Cross | US | Apr‐20 | 511 adults from the US (97% women) and 510 adults from Netherlands (99% women) who self‐reported a current or lifetime ED. race/ethnicity N/R |

|

|

| (Vitagliano et al., 2021) | Cross | US | Jun–Aug‐20 | 89 younger individuals with a self‐reported ED (89% women); 78% white; other races/ethnicities N/R |

|

|

| (Vuillier, May, Greville‐Harris, Surman, & Moseley, 2021) | Cross | UK | Unclear | 207 adults with a self‐reported ED (64% women); 94% white; 5% Asian; 0.5% black; 0.5% Asian |

|

|

| (Yaffa et al., 2021) | Long (retro) | Israel |

Pre‐pandemic 2015–2019 During pandemic Jan–Oct‐20 |

Service data at a pediatric ED treatment Centre in Israel. sample demographics N/R |

|

|

Abbreviations: AN, anorexia nervosa; Aus, Australia; BED, binge‐eating disorder; BN, bulimia nervosa; Braz, Brazil; Can, Canada; Cross, cross‐sectional; Fran, France; Germ, Germany; Leb, Lebanon; long (pros), longitudinal prospective design; long (retro), longitudinal retrospective design; N/R, not reported or unclear; NZ, New Zealand; OSFED, other specified feeding or eating disorder; Port, Portugal; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

To briefly summarize the study characteristics, two‐thirds of included studies employed a cross‐sectional design. Most studies were conducted by researchers in the United States, Italy, United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, and Spain. Across studies, the vast majority of participants identified as female and White/Caucasian. However, reporting of specific racial and ethnic distributions was missing in nearly 75% of studies. Nearly one‐third of included studies sampled individuals with an eating disorder; >50% of which were established via semistructured diagnostic interviews, while others were based off self‐report or it was not made clear. Most of the studies of non‐clinical populations sampled university students or adults/adolescents from the general population. These studies used samples of convenience by relying on social media advertisements or snowballing methods, and participants self‐selecting into the study. We note, however, that detailed descriptions of the recruitment strategy were generally lacking across included studies. We refer readers to Tables 1 and 2 for a more detailed description of the samples, recruitment methods, designs, and key findings.

3.2. Summary of findings

3.2.1. Suspected eating disorder cases during COVID‐19

The first theme identified was the prevalence of possible eating disorder cases among non‐clinical samples during the pandemic. Eleven studies (participant ns = 120–5,378) investigated this theme by estimating the proportion of participants scoring above an established clinical cut‐off on a self‐report assessment (Alessi et al., 2020; Buckley et al., 2021; Cecchetto et al., 2021; Chan & Chiu, 2021; Christensen et al., 2021; Flaudias et al., 2020; Kohls et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2021; Thompson & Bardone‐Cone, 2021; Troncone et al., 2020; Trott et al., 2021). None of the samples was representative of the wider population, nor were sampling weights applied in any study in attempts to generalize to the wider population. The convenience samples included university students, adults from the community, and individuals with Type 1 or 2 diabetes. Among the five studies using the Eating Attitudes Test (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979), the percentage scoring above clinical cut‐off ranged from 8–75%, with the two studies with the largest sample size (n = 306 and 319) producing prevalence rates of 8 and 28% (Thompson & Bardone‐Cone, 2021; Trott et al., 2021). These estimates were comparable to those reported in pre‐pandemic studies using the EAT (Al‐Adawi, Dorvlo, Burke, Moosa, & Al‐Bahlani, 2002). Two studies used the SCOFF (Morgan, Reid, & Lacey, 1999), one with a sample size of 5,738 (Flaudias et al., 2020) and another with a sample size of 316 (Chan & Chiu, 2021). The former reported a clinical cut‐off prevalence of 38% and the latter 26%, which were noticeably higher than some pre‐pandemic studies in non‐clinical populations (e.g., <13%; Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder, & Kirz, 2011). Remaining studies each used a different self‐report scale to determine clinical cut‐offs, making between‐study comparisons difficult.

3.2.2. Perceived impact of COVID‐19 on eating disorder symptoms

The second theme identified was an investigation of the perceived impact of the pandemic on eating disorder or mental health symptoms. Twenty‐two studies examined this theme, with 16 studies sampling clinical populations (participant ns = 12–1,021; Akgül et al., 2021; Baenas et al., 2020; Branley‐Bell & Talbot, 2020; Favreau et al., 2021; Graell et al., 2020; Machado et al., 2020; Quittkat et al., 2020; Richardson et al., 2020; Schlegl, Maier, Meule, & Voderholzer, 2020; Schlegl, Meule, Favreau, & Voderholzer, 2020; Shaw et al., 2021; Spettigue et al., 2021; Spigel et al., 2021; Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Vitagliano et al., 2021; Vuillier et al., 2021) and six studies sampling non‐clinical populations (participant ns = 90–5,469; Athanasiadis et al., 2021; Buckley et al., 2021; Coimbra et al., 2021; Keel et al., 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2021). In all cases, the authors developed their own items assessing perceived impacts of COVID‐19.

Clinical samples

Among those studies that sampled individuals with an eating disorder, 13 (81%) assessed the perceived impact of the pandemic on participants' eating disorder overall. The percentage of participants who reported a worsening of their eating disorder due to the pandemic ranged from 8 to 78%. The one study to investigate which aspects of the pandemic participants were most concerned about in relation to their eating disorder found that the lack of normal structure and increased time living in a triggering environment contributed to greatest concern levels (Termorshuizen et al., 2020). A second study found that among those who reported that their eating disorder had been negatively impacted by the pandemic, the three most important factors contributing to this were changes to routine, changes to physical activity, and difficulties in regulating emotions (Vuillier et al., 2021).

Seven of the studies with clinical samples (43%) also investigated the perceived impact of the pandemic on specific eating disorder symptoms. The percentage of participants who reported that the pandemic had worsened specific symptoms was as follows: binge eating (14–47%), dietary restriction (44–65%), driven exercise (42–50%), compensatory behaviors (7–36%), and body image concerns (29–80%). One study surveyed healthcare providers, asking them to retrospectively recall the perceived impact of the pandemic on their patients' symptoms (Colleluori et al., 2021). Healthcare providers reported that >30% of their patients had experienced an increase in binge eating and compensatory behaviors during this period.

Thirteen studies (81%) also assessed broader mental health impacts of the pandemic in clinical samples, all based on retrospective recall. Each of these studies found a significant percentage (37–80%) of participants with an eating disorder to report a worsening of their general mental health (e.g., symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress) and wellbeing (e.g., quality of life) due to the pandemic.

Non‐clinical samples

Each of the six studies on non‐clinical samples (all based on retrospective recall) found a sizeable percentage of participants to report worsening of specific eating disorder symptoms due to the pandemic, including binge eating (20–34%), dietary restriction (25–27%), strict exercise (30%), and concerns with eating, shape and weight (35–61%; Athanasiadis et al., 2021; Buckley et al., 2021; Coimbra et al., 2021; Keel et al., 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2021).

3.2.3. Symptom severity pre versus during COVID‐19

The third theme identified was a comparison of symptom severity pre versus during the pandemic.

Comparison of different cohorts

Eight studies (participant ns = 48–8,613) assessed a cohort of participants during the pandemic and compared their symptom severity to a different cohort assessed prior to the pandemic (Calugi et al., 2021; Christensen et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; Koenig et al., 2021; Muzi et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2020; Spettigue et al., 2021; Zhou & Wade, 2021). Only three of these studies (37%) reported no significant differences in certain demographic or clinical characteristics between the two cohorts (Calugi et al., 2021; Keonig et al 2021; Zhou & Wade, 2021). Six of these eight studies (75%) sampled non‐clinical populations. Overall, findings were mixed due to heterogeneous sample sizes, target populations, and constructs assessed. Three studies (50%) reported no significant cohort differences in binge eating severity (Calugi et al., 2021; Muzi et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2020), while one study (16%) observed significantly higher rates of a probable binge‐eating‐type disorder in the pandemic cohort (14.4%) relative to the pre‐pandemic cohort (10.6%) (Kim et al., 2021). One study (16%) found the pandemic cohort to report significantly higher levels of eating disorder psychopathology (Zhou & Wade, 2021), but this was not replicated in a different study (Koenig et al., 2021). Two studies (33%) found the pandemic cohort to report significantly higher levels of dietary restriction than the pre‐pandemic cohort (Richardson et al., 2020; Spettigue et al., 2021).

One noteworthy paper studied the electronic health records of 5.2 million people from the United States to compare the outcomes of eating disorders pre versus during the pandemic period (Taquet et al., 2021). The diagnostic incidence was 15% higher in 2020 compared to 2019, and the increased risk of eating disorders during the pandemic was limited to females, greatest for 10–19 year olds, and mostly affected anorexia nervosa diagnoses. Compared to those diagnosed with an eating disorder prior to the pandemic, those diagnosed during the pandemic were at a significantly higher risk of attempting suicide and having suicidal ideation (Taquet et al., 2021).

Comparisons within the same cohort

Seven longitudinal studies (participant ns = 42–319) investigated the trajectory of symptom change from before to during the pandemic (Baceviciene & Jankauskiene, 2021; Castellini et al., 2020; Giel et al., 2021; Machado et al., 2020; Martínez‐de‐Quel et al., 2021; Pensgaard et al., 2021; Trott et al., 2021). Four studies used a clinical sample and three used a non‐clinical sample of convenience. Studies implemented two time‐points, but the time‐points from assessment one (ranging from May 2018 to April 2020) to two (ranging from May to October 2020) varied markedly, making between‐study comparisons and conclusions difficult. Potential attrition biases were noted in all but one paper (Martínez‐de‐Quel et al., 2021).

Among the four studies of clinical samples, results were mixed. An increase in binge eating was reported in two studies (50%; Castellini et al., 2020; Giel et al., 2021), but a decrease was reported in one study (25%; Pensgaard et al., 2021). Two studies (50%) reported no change in the level of eating disorder psychopathology (Castellini et al., 2020; Machado et al., 2020), while one study (25%) reported significant increases pre versus during pandemic periods (Giel et al., 2021). Two studies (50%) reported significant improvements in general mental health and wellbeing (Giel et al., 2021; Pensgaard et al., 2021), but two different studies (50%) observed no change over time (Castellini et al., 2020; Machado et al., 2020). Of the three studies of non‐clinical participants, only one (33%) reported a significant increase in eating disorder psychopathology during the pandemic period (Trott et al., 2021).

3.2.4. Pandemic‐related correlates of symptom severity

The fourth theme concerned pandemic‐related correlates of symptom severity. Fifteen studies investigated this theme; 14 studies investigated cross‐sectional relationships (ns = 43–5,738; Castellini et al., 2020; Christensen et al., 2021; Czepczor‐Bernat et al., 2021; De Pasquale et al., 2021; Flaudias et al., 2020; Haddad et al., 2020; Jordan et al., 2021; Machado et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2021; Scharmer et al., 2020; Schlegl, Maier, et al., 2020; Schlegl, Meule, et al., 2020; Simone et al., 2021; Thompson & Bardone‐Cone, 2021) and one pilot study of 15 individuals with bulimia nervosa assessed prospective relationships using an experience sampling design (Leenaerts et al., 2021).

The 14 studies investigating cross‐sectional correlates are difficult to synthesize and interpret for two main reasons. First, there was limited consistency with respect to the types of correlates and symptoms investigated, and the measures used to assess these. Second, several studies appeared to have omitted reporting non‐significant relationships. Seven studies reported significant positive relationships between COVID‐19‐related fears, anxiety, and stress with various cognitive and behavioral symptoms of eating disorders (Castellini et al., 2020; Czepczor‐Bernat et al., 2021; De Pasquale et al., 2021; Flaudias et al., 2020; Haddad et al., 2020; Machado et al., 2020; Scharmer et al., 2020). Two studies each found eating disorder symptoms to be significantly and positively correlated with food insecurity (Christensen et al., 2021; Simone et al., 2021) and financial difficulties (Haddad et al., 2020; Simone et al., 2021). No study explored complex, interactive effects of stressors on symptoms, nor the possibility that impacts of these stressors may be moderated by support structures available to participants. Two studies worth noting enquired about helpful coping strategies implemented during the pandemic among participants with anorexia nervosa (Schlegl, Maier, et al., 2020) and bulimia nervosa (Schlegl, Meule, et al., 2020), finding engagement of daily routines, day planning, participating in enjoyable activities, mild physical activity, and virtual social contact to be rated as most helpful.

3.2.5. Impacts on carers/parents

The fifth theme concerns the impacts of COVID‐19 on carers/parents of younger people with eating disorders. Seven papers reported data on this (Brothwood et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2020; Jordan et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021), with the stated impacts on carers/parents varying. Two papers (28%) found that carers of young people with an eating disorder reported poorer mental health problems than a matched sample of carers of healthy young people (Guo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Furthermore, in one study (14%), 26% of parents disagreed that their child was coping during the pandemic (Shaw et al., 2021), and two studies (28%) reported parents to hold favorable attitudes toward the transition to online treatment for their child (Brothwood et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2021). One study (14%) also found evidence that parent inquiries to a specialized eating disorder program increased during the pandemic period relative to pre‐pandemic periods (Lin et al., 2021).

3.2.6. Treatment experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic

The final theme synthesizes research related to treatment experiences during the pandemic, including patterns of specialist service usage, patient perceptions treatment, and the preliminary efficacy of virtual treatment.

Specialist service usage

To assess time trends in help‐seeking, seven studies analyzed pre and during pandemic record data related to eating disorder services. The services varied in scope, with some being government‐funded public health services, private hospitals, and call services. There was evidence for an increase in demand for eating disorder services during the pandemic. Compared to pre‐pandemic periods, during pandemic periods were associated with a doubling of inpatient and first‐ever eating disorder patient admissions in a New Zealand treatment service (Hansen et al., 2021), a 13% increase in the number of urgent referrals for a UK‐based service (Shaw et al., 2021), more treatment sessions offered across centers in the UK and Israel (Shaw et al., 2021; Yaffa et al., 2021), and more US‐based specialist service enquiries or contacts (Lin et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2020). In contrast, one study (14%) found no differences in the number of admissions and referrals from 2019 to 2020 in a specialist service in Madrid (Graell et al., 2020), while another report (14%) of >10 million electronic records of general practitioner contacts found evidence of a reduction in contact behavior for eating disorders when comparing pre and during pandemic time periods (Mansfield et al., 2021).

Patient perceptions of treatment

Nine studies gathered data on patient perceptions of treatment during the pandemic period (Brothwood et al., 2021; Fernandez‐Aranda et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2021; Raykos et al., 2021; Schlegl, Maier, et al., 2020; Schlegl, Meule, et al., 2020; Spigel et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2021; Termorshuizen et al., 2020). Five studies (55%) found that a sizeable percentage of participants (28–74%) reported that the pandemic had significantly disrupted or negatively impacted their treatment (Lewis et al., 2021; Schlegl, Maier, et al., 2020; Schlegl, Meule, et al., 2020; Spigel et al., 2021; Termorshuizen et al., 2020). A handful of small sample (participant ns = 14–73) studies also gathered data on patient perceptions of transitioning to online treatment. While two studies (50%) found ~65% of patients to rate online treatment as good as face‐to‐face treatment (Raykos et al., 2021; Spigel et al., 2021), two other studies (50%) found fewer than 10% of patients wanting to remain in online treatment after the pandemic (Lewis et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2021). None of these studies reported prior experience with, nor expectations of, digital or telehealth treatment options that might help contextualize these findings.

Clinical effects of online treatment

Three non‐randomized pilot studies evaluated the preliminary effectiveness of treatment services delivered via digital means (i.e., telehealth, videoconferencing) due to social distancing policies (Levinson et al., 2021; Plumley et al., 2021; Raykos et al., 2021). Although sample sizes were small (ns = 9, 25, and 93), each study found the online service to be safe, tolerated, and effective for improving general mental health and eating disorder symptoms from pre‐ to posttest periods. In two studies (66%), the degree of symptom improvement experienced from the online treatment was highly comparable to historical benchmarks at the same clinic (Levinson et al., 2021; Raykos et al., 2021), highlighting the viability of digitally‐delivered treatments during the pandemic.

4. DISCUSSION

The urgent need to understand the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in a proliferation of research publications in the field of mental health (Akintunde et al., 2021). This rate of knowledge transmission proves challenging for all to quickly―yet reliably―obtain a nuanced understanding of COVID‐19 impacts in order to facilitate timely prevention and intervention efforts to individuals or service sectors in greatest need. Here we present a scoping review of the literature on COVID‐19 and eating disorders.

4.1. Key findings

Several patterns were evident across the 70 studies. Despite variability in estimates across studies, eating disorders symptom severity and incidence of probable diagnoses appear to be elevated during COVID‐19. These findings were observed whether symptom levels were assessed with or without reference to pre‐COVID levels (e.g., Branley‐Bell & Talbot, 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020), in comparison to pre‐COVID cohorts (e.g., Kim et al., 2021; Taquet et al., 2021), and were also supported by data from healthcare providers (Colleluori et al., 2021). Individuals with an eating disorder also reported broader mental health concerns related to the pandemic (Akgül et al., 2021; Quittkat et al., 2020), suggesting that COVID‐19 impacts in this population may not be localized to eating disorder psychopathology. Lack of structure and disrupted routines, greater exposure to environmental triggers, and difficulties regulating emotion were highlighted as possible precipitants for symptom deterioration (Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Vuillier et al., 2021). These findings accord with broader trends of worsening mental health in the community from both cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies undertaken amidst COVID‐19 (Samji et al. 2021; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020). While findings are also consistent with conclusion drawn from two earlier systematic reviews of COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorders (Miniati et al., 2021; Sideli et al., 2021), the present, updated review identified nearly four times as many eligible studies and highlighted much broader impacts of the pandemic on eating disturbances.

Evidence was more limited with respect to COVID‐19‐related correlates of eating disorder symptoms and the experiences of treatment during the pandemic. In terms of studies investigating COVID‐19‐specific correlates of symptom severity, a diverse range of variables was assessed (e.g., COVID‐related fear, anxiety, stress, etc.); however, there was little overlap of measures or constructs across these studies, as has been also reported in the mental health literature more generally (Ransing et al., 2021). The replicability of these findings therefore remains unclear. For studies assessing treatment experiences and outcomes, evidence was similarly limited, inconsistent, and based on small sample sizes. While studies showed that some patients were accepting of being transferred from face‐to‐face to telehealth treatment modalities (Raykos et al., 2021; Stewart et al., 2021), others showed that many patients reported dissatisfaction with online treatment services and a desire to return to traditional delivery modes as soon as possible (Brothwood et al., 2021; Lewis et al., 2021). Despite this dissatisfaction, three uncontrolled pilot studies showed large symptom improvement following the forced transition to online treatment (Levinson et al., 2021; Plumley et al., 2021; Raykos et al., 2021). It is important to point out that expectations of and prior experience with online modes of treatment delivery were not assessed in any of these studies, nor was it clear whether COVID‐19 had facilitated the decision to seek help in previously reluctant individuals. These are necessary avenues for future research.

4.2. Methodological limitations of the existing literature

Present findings must be interpreted considering significant methodological constraints. Most studies were reliant upon participant self‐report and employed cross‐sectional designs. Comparison to pre‐pandemic experiences typically involved retrospective recall or comparison to pre‐pandemic cohorts without adequate control of differences between samples (Pierce et al., 2020). Moreover, most studies used online convenience sampling, snowballing, or social media recruitment methods that facilitate wide reach and rapid recruitment at the possible expense of representativeness (i.e., not everyone has access to the Internet, potentially leading to biases toward more affluent or urban populations; Pierce et al., 2020). Few studies utilized multiple recruitment strategies to mitigate these risks, and no study evaluated robustness of findings if survey weights were applied to correct for non‐representativeness.

In addition, none of the longitudinal studies explored for effects of attrition bias on observed results. The high—and highly variable—rates of probable eating disorder cases and elevated symptom severity should be interpreted with a high degree of caution, as they are likely overestimated. It is cold comfort that the eating disorder field is not alone in these methodological challenges with extant COVID‐19 research (Bramstedt, 2020; Jung et al., 2021). However, we also share optimism expressed by others (e.g., Jung et al., 2021) that higher quality research—which typically takes longer to produce—is likely to become available in the coming months to balance concerns with methodological difficulties of early COVID‐19 research. In future reviews, stratifying findings by publication quality and conducting cumulative meta‐analyses (Wetterslev, Thorlund, Brok, & Gluud, 2008) may improve our understanding of COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorders as new data emerge.

4.3. Gaps and recommendations for future work

An important theme to emerge from this review was that COVID‐19 has exacerbated existing disparities in research on eating disorders. Almost all studies identified in our review derived from countries that are already overrepresented in the field, and so pandemic impacts on eating disorders in developing nations are unclear. Similarly, as most samples primarily comprised Caucasian women, pandemic impacts on minority groups or male populations are also poorly understood. Since demographic influences on treatment seeking, vaccine uptake, and perceived seriousness of COVID‐19 have already been documented (Duan et al., 2020; Özdin & Bayrak Özdin, 2020; Ruiz & Bell, 2021), it is essential that future studies sample diverse population groups to broaden our understanding of COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorders.

We observed a clear disconnect between recent priority setting articles in the eating disorder field (e.g., Cooper et al., 2020; Fernández‐Aranda et al., 2020; Hart & Wade, 2020) and the largely descriptive COVID‐19‐related studies conducted to date. Difficulties engaging individuals with eating disorders in treatment, existing strains on healthcare system delivery, and patients' reported challenges navigating treatment pathways are likely exacerbated by COVID‐19, yet few studies have investigated these issues. It remains unclear whether increased caseloads resulting from the pandemic reflect an increase in help‐seeking, continued low levels of help‐seeking but higher incidence of symptomatic individuals, or greater recognition of the problem from the families' perspective due to more time spent in the same household together. Likewise, it is unknown what initiatives have been attempted in healthcare settings to handle possible increases in caseloads, and what insights may be gained from these efforts for enhancing efficiency in healthcare delivery. Artificial intelligence solutions for identifying patterns in case notes and healthcare usage data have been applied in other medical fields (Rajkomar et al., 2018), and could provide insights for eating disorder services. Task shifting to digital health and peer mentoring‐based solutions seem obvious solutions but need coordination with traditional treatment services to be realized (Linardon, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Messer, & Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, 2019; Torous et al., 2021). Nascent data in the field of COVID‐19 and eating disorders suggests continued resistance to non‐traditional delivery modes (Brothwood et al., 2021). Recent efforts to understand who prefers and is most likely to benefit from digital health (Linardon, Messer, Lee, & Rosato, 2020; Linardon, Shatte, Tepper, & Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, 2020) provide necessary data to facilitate online triage systems to safely divert some individuals from face‐to‐face to online services. However, infrastructure gaps and the lack of centralized, consolidated systems to help individuals navigate through different treatment options and routinely monitor progress remain a glaring need in this field.

The uneven distribution of studies across themes in the present review highlights duplication of research efforts where a field‐wide, coordinated approach could yield better data and broader insights. Established principles of open science (Nosek et al., 2015; Open Science Collaboration, 2015) may provide useful here, and, encouragingly, are starting to be adopted in the field of the eating disorders (Burke et al., 2021). For example, preregistration of study protocols with material sharing would help address the issue of the plethora of self‐created measurement tools assessing COVID‐19 impacts on symptoms, thereby allowing for more accurate and simpler between‐study comparisons. Furthermore, there is a role for eating disorder journals and organizations to marshal expert stakeholder representation to facilitate rapid priority‐setting exercises and updatable evidence gap maps to better catalyze research efforts based on need. Enhancing collaboration and coordination of the eating disorder research community will be beneficial both during and beyond the pandemic period.

Finally, the breadth and rapid expansion of eating disorder research identified during COVID‐19 increases the difficulty in providing timely, accurate, and comprehensive coverage of the literature. Machine learning‐based approaches to accelerate research synthesis and to enable living systematic reviews are emerging and should be adopted (Elliott et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2017). We should also prioritize recent innovations in effective communication of research findings to stakeholders (e.g., researchers, clinicians, patients and their families, and policy‐makers). Data visualization, evidence gap maps, and open access lay summaries of content exemplify recent efforts in other disciplines to reduce research waste, prioritize attention to research gaps, and reduce knowledge‐to‐translation gaps (Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020).

4.4. Limitations and conclusion

The present study includes some important limitations. First, this area of research is a very rapidly evolving one, and even though the last search was conducted in August, additional work may now be available. Second, although no limitations were imposed on the search, it is possible that findings were restricted to mostly English speaking or high‐income countries, due to the effects of language barriers on the speed of publication.

To conclude, our study highlights the breadth of empirical research that has rapidly accumulated examining the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic and accompanying disruptions on eating disorders. Together, existing data suggest that eating disorder rates, severity, and comorbidity have increased. However, understanding of potential mechanisms accounting for this is limited by this extant literature being participant self‐report or retrospective recall, cross‐sectional and descriptive studies, and samples of convenience. Strategic, cohesive, and collaborative efforts to move toward more rigorously designed studies with the capacity to elucidate these pathways are needed. Such efforts may be supported by emerging technology but are also the responsibility of researchers and other stakeholders to implement.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work of Jake Linardon (APP1196948) is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant.

Linardon, J. , Messer, M. , Rodgers, R. F. , & Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M. (2022). A systematic scoping review of research on COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorders: A critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(1), 3–38. 10.1002/eat.23640

Action Editor: Kelly L. Klump

Funding information National Health and Medical Research Council, Grant/Award Number: APP1196948

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

There are no data associated with this research.

REFERENCES

- Akgül, S. , Akdemir, D. , Nalbant, K. , Derman, O. , Ersöz Alan, B. , Tüzün, Z. , & Kanbur, N. (2021). The effects of the COVID‐19 lockdown on adolescents with an eating disorder and identifying factors predicting disordered eating behaviour. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 10.1111/eip.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akintunde, T. Y. , Musa, T. H. , Musa, H. H. , Musa, I. H. , Chen, S. , Ibrahim, E. , … Helmy, M. S. E. D. M. (2021). Bibliometric analysis of global scientific literature on effects of COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 63, 102753. 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Adawi, S. , Dorvlo, A. , Burke, D. , Moosa, S. , & Al‐Bahlani, S. (2002). A survey of anorexia nervosa using the Arabic version of the EAT‐26 and “gold standard” interviews among Omani adolescents. Eating and Weight Disorders‐Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 7, 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldhuwayhi, S. , Shaikh, S. A. , Mallineni, S. K. , Varadharaju, V. K. , Thakare, A. A. , Ahmed Khan, A. R. , … Manva, M. Z. (2021). Occupational stress and stress busters utilized among Saudi dental practitioners during the COVID‐19 pandemic outbreak. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 10.1017/dmp.2021.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi, J. , de Oliveira, G. B. , Franco, D. W. , Brino do Amaral, B. , Becker, A. S. , Knijnik, C. P. , … Telo, G. H. (2020). Mental health in the era of COVID‐19: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes during the social distancing. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome, 12, 76. 10.1186/s13098-020-00584-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadis, D. I. , Hernandez, E. , Hilgendorf, W. , Roper, A. , Embry, M. , Selzer, D. , & Stefanidis, D. (2021). How are bariatric patients coping during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic? Analysis of factors known to cause weight regain among postoperative bariatric patients. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases, 17, 756–764. 10.1016/j.soard.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baceviciene, M. , & Jankauskiene, R. (2021). Changes in sociocultural attitudes towards appearance, body image, eating attitudes and behaviours, physical activity, and quality of life in students before and during COVID‐19 lockdown. Appetite, 166, 105452. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenas, I. , Caravaca‐Sanz, E. , Granero, R. , Sánchez, I. , Riesco, N. , Testa, G. , … Fernández‐Aranda, F. (2020). COVID‐19 and eating disorders during confinement: Analysis of factors associated with resilience and aggravation of symptoms. European Eating Disorders Review, 28, 855–863. 10.1002/erv.2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, P. , van Schalkwyk, M. C. , McKee, M. , Labonté, R. , & Stuckler, D. (2021). COVID‐19 and the collapse of global trade: Building an effective public health response. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5, e102–e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal, D. , Fowler, E. J. , Abrams, M. , & Collins, S. R. (2020). Covid‐19—Implications for the health care system. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 1483–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramstedt, K. A. (2020). The carnage of substandard research during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A call for quality. Journal of Medical Ethics, 46, 803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branley‐Bell, D. , & Talbot, C. V. (2020). Exploring the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 44. 10.1186/s40337-020-00319-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiner, C. E. , Miller, M. L. , & Hormes, J. M. (2021). Changes in eating and exercise behaviors during the COVID‐19 pandemic in a community sample: A retrospective report. Eating Behaviors, 42, 101539. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothwood, P. L. , Baudinet, J. , Stewart, C. S. , & Simic, M. (2021). Moving online: Young people and parents' experiences of adolescent eating disorder day programme treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 62. 10.1186/s40337-021-00418-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, G. L. , Hall, L. E. , Lassemillante, A.‐C. M. , & Belski, R. (2021). Disordered eating & body image of current and former athletes in a pandemic; a convergent mixed methods study‐what can we learn from COVID‐19 to support athletes through transitions? Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 73. 10.1186/s40337-021-00427-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, N. L. , Frank, G. K. , Hilbert, A. , Hildebrandt, T. , Klump, K. L. , Thomas, J. J. , … Weissman, R. S. (2021). Open Science practices for eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54, 1719–1729. 10.1002/eat.23607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calugi, S. , Andreoli, B. , Dametti, L. , Dalle Grave, A. , Morandini, N. , & Dalle Grave, R. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 lockdown on patients with obesity after intensive cognitive behavioral therapy‐a case‐control study. Nutrients, 13, 2021. 10.3390/nu13062021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, G. , Cassioli, E. , Rossi, E. , Innocenti, M. , Gironi, V. , Sanfilippo, G. , … Ricca, V. (2020). The impact ofCOVID‐19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1855–1862. 10.1002/eat.23368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetto, C. , Aiello, M. , Gentili, C. , Ionta, S. , & Osimo, S. A. (2021). Increased emotional eating during COVID‐19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress. Appetite, 160, 105122. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. Y. , & Chiu, C. Y. (2021). Disordered eating behaviors and psychological health during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychology Health & Medicine. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1883687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K. A. , Forbush, K. T. , Richson, B. N. , Thomeczek, M. L. , Perko, V. L. , Bjorlie, K. , … Mildrum Chana, S. (2021). Food insecurity associated with elevated eating disorder symptoms, impairment, and eating disorder diagnoses in an American University student sample before and during the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54, 1213–1223. 10.1002/eat.23517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coimbra, M. , Paixão, C. , & Ferreira, C. (2021). Exploring eating and exercise‐related indicators during COVID‐19 quarantine in Portugal: Concerns and routine changes in women with different BMI. Eating and Weight Disorders. 10.1007/s40519-021-01163-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colleluori, G. , Goria, I. , Zillanti, C. , Marucci, S. , & Dalla Ragione, L. (2021). Eating disorders during COVID‐19 pandemic: The experience of Italian healthcare providers. Eating and Weight Disorders. 10.1007/s40519-021-01116-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. , Reilly, E. E. , Siegel, J. A. , Coniglio, K. , Sadeh‐Sharvit, S. , Pisetsky, E. M. , & Anderson, L. M. (2020). Eating disorders during the COVID‐19 pandemic and quarantine: An overview of risks and recommendations for treatment and early intervention. Eating Disorders, 1–23. 10.1080/10640266.2020.1790271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czepczor‐Bernat, K. , Swami, V. , Modrzejewska, A. , & Modrzejewska, J. (2021). COVID‐19‐related stress and anxiety, body mass index, eating disorder symptomatology, and body image in women from Poland: A cluster analysis approach. Nutrients, 13, 1384. 10.3390/nu13041384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pasquale, C. , Sciacca, F. , Conti, D. , Pistorio, M. L. , Hichy, Z. , Cardullo, R. L. , & Di Nuovo, S. (2021). Relations between mood states and eating behavior during COVID‐19 pandemic in a sample of Italian college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 684195. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.684195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H. , Yan, L. , Ding, X. , Gan, Y. , Kohn, N. , & Wu, J. (2020). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health in the general Chinese population: Changes, predictors and psychosocial correlates. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, D. , Nicklett, E. J. , Roeder, K. , & Kirz, N. E. (2011). Eating disorder symptoms among college students: Prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment‐seeking. Journal of American College Health, 59, 700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J. H. , Synnot, A. , Turner, T. , Simmonds, M. , Akl, E. A. , McDonald, S. , … Hilton, J. (2017). Living systematic review: 1. Introduction—The why, what, when, and how. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 91, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favreau, M. , Hillert, A. , Osen, B. , Gartner, T. , Hunatschek, S. , Riese, M. , … Voderholzer, U. (2021). Psychological consequences and differential impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic in patients with mental disorders. Psychiatry Research, 302, 114045. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Aranda, F. , Casas, M. , Claes, L. , Bryan, D. C. , Favaro, A. , Granero, R. , … Le Grange, D. (2020). COVID‐19 and implications for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 28, 239–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Aranda, F. , Munguia, L. , Mestre‐Bach, G. , Steward, T. , Etxandi, M. , Baenas, I. , … Jimenez‐Murcia, S. (2020). COVID isolation eating scale (CIES): Analysis of the impact of confinement in eating disorders and obesity‐a collaborative international study. European Eating Disorders Review, 28, 871–883. 10.1002/erv.2784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaudias, V. , Iceta, S. , Zerhouni, O. , Rodgers, R. F. , Billieux, J. , Llorca, P.‐M. , … Guillaume, S. (2020). COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown and problematic eating behaviors in a student population. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9, 826–835. 10.1556/2006.2020.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner, D. M. , & Garfinkel, P. E. (1979). The eating attitudes test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giel, K. E. , Schurr, M. , Zipfel, S. , Junne, F. , & Schag, K. (2021). Eating behaviour and symptom trajectories in patients with a history of binge eating disorder during COVID‐19 pandemic. European Eating Disorders Review, 29, 657–662. 10.1002/erv.2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graell, M. , Morón‐Nozaleda, M. G. , Camarneiro, R. , Villaseñor, Á. , Yáñez, S. , Muñoz, R. , … Faya, M. (2020). Children and adolescents with eating disorders during covid‐19 confinement: Difficulties and future challenges. European Eating Disorders Review., 28, 864–870. 10.1002/erv.2763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L. , Wu, M. , Zhu, Z. , Zhang, L. , Peng, S. , Li, W. , … Chen, J. (2020). Effectiveness and influencing factors of online education for caregivers of patients with eating disorders during COVID‐19 pandemic in China. European Eating Disorders Review, 28, 816–825. 10.1002/erv.2783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, C. , Zakhour, M. , Bou Kheir, M. , Haddad, R. , Al Hachach, M. , Sacre, H. , & Salameh, P. (2020). Association between eating behavior and quarantine/confinement stressors during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 40. 10.1186/s40337-020-00317-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, S. J. , Stephan, A. , & Menkes, D. B. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on eating disorder referrals and admissions in Waikato, New Zealand. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, L. M. , & Wade, T. (2020). Identifying research priorities in eating disorders: A Delphi study building consensus across clinicians, researchers, consumers, and carers in Australia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A. K. , Barnhart, W. R. , Studer‐Perez, E. I. , Kalantzis, M. A. , Hamilton, L. , & Musher‐Eizenman, D. R. (2021). 'Quarantine 15': Pre‐registered findings on stress and concern about weight gain before/during COVID‐19 in relation to caregivers' eating pathology. Appetite, 166, 105580–105580. 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, R. G. , Di Santo, P. , Clifford, C. , Prosperi‐Porta, G. , Skanes, S. , Hung, A. , … Simard, T. (2021). Methodological quality of COVID‐19 clinical research. Nature Communications, 12, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel, P. K. , Gomez, M. M. , Harris, L. , Kennedy, G. A. , Ribeiro, J. , & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Gaining “The Quarantine 15”: Perceived versus observed weight changes in college students in the wake of COVID‐19. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1801–1808. 10.1002/eat.23375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Rackoff, G. N. , Fitzsimmons‐Craft, E. E. , Shin, K. E. , Zainal, N. H. , Schwob, J. T. , … Newman, M. G. (2021). College mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Results from a Nationwide survey. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 10.1007/s10608-021-10241-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, J. , Kohls, E. , Moessner, M. , Lustig, S. , Bauer, S. , Becker, K. , … Pro, H. C. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 related lockdown measures on self‐reported psychopathology and health‐related quality of life in German adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1007/s00787-021-01843-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls, E. , Baldofski, S. , Moeller, R. , Klemm, S.‐L. , & Rummel‐Kluge, C. (2021). Mental health, social and emotional well‐being, and perceived burdens of university students during COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643957. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenaerts, N. , Vaessen, T. , Ceccarini, J. , & Vrieze, E. (2021). How COVID‐19 lockdown measures could impact patients with bulimia nervosa: Exploratory results from an ongoing experience sampling method study. Eating Behaviors, 41, 101505. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, C. A. , Spoor, S. P. , Keshishian, A. C. , & Pruitt, A. (2021). Pilot outcomes from a multidisciplinary telehealth versus in‐person intensive outpatient program for eating disorders during versus before the Covid‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Eating Disorders., 54, 1672–1679. 10.1002/eat.23579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Y. D. , Elran‐Barak, R. , Grundman‐Shem Tov, R. , & Zubery, E. (2021). The abrupt transition from face‐to‐face to online treatment for eating disorders: A pilot examination of patients' perspectives during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 31. 10.1186/s40337-021-00383-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Cao, L. , Zhang, Z. , Hou, L. , Qin, Y. , Hui, X. , … Cui, X. (2021). Reporting and methodological quality of COVID‐19 systematic reviews needs to be improved: An evidence mapping. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 135, 17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. A. , Hartman‐Munick, S. M. , Kells, M. R. , Milliren, C. E. , Slater, W. A. , Woods, E. R. , … Richmond, T. K. (2021). The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on the number of adolescents/young adults seeking eating disorder‐related care. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine., 69, 660–663. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon, J. , Cuijpers, P. , Carlbring, P. , Messer, M. , & Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M. (2019). The efficacy of app‐supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 18, 325–336. 10.1002/wps.20673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon, J. , Messer, M. , Lee, S. , & Rosato, J. (2020). Perspectives of e‐health interventions for treating and preventing eating disorders: Descriptive study of perceived advantages and barriers, help‐seeking intentions, and preferred functionality. Eating and Weight Disorders., 26, 1097–1109. 10.1007/s40519-020-01005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon, J. , Shatte, A. , Tepper, H. , & Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz, M. (2020). A survey study of attitudes toward, and preferences for, e‐therapy interventions for eating disorder psychopathology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 907–916. 10.1002/eat.23268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N. , Chee, M. L. , Niu, C. , Pek, P. P. , Siddiqui, F. J. , Ansah, J. P. , … Chan, A. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): An evidence map of medical literature. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, P. P. P. , Pinto‐Bastos, A. , Ramos, R. , Rodrigues, T. F. , Louro, E. , Gonçalves, S. , … Vaz, A. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 lockdown measures on a cohort of eating disorders patients. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 57. 10.1186/s40337-020-00340-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, K. E. , Mathur, R. , Tazare, J. , Henderson, A. D. , Mulick, A. R. , Carreira, H. , … Langan, S. M. (2021). Indirect acute effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the UK: A population‐based study. Lancet Digital Health, 3, E217–E230. 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00017-0ac.uk [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐de‐Quel, Ó. , Suárez‐Iglesias, D. , López‐Flores, M. , & Pérez, C. A. (2021). Physical activity, dietary habits and sleep quality before and during COVID‐19 lockdown: A longitudinal study. Appetite, 158, 105019. 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M. , & Stuckler, D. (2020). If the world fails to protect the economy, COVID‐19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nature Medicine, 26, 640–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda, N. , Pardini, S. , Slongo, I. , Bodini, L. , Zordan, M. A. , Rigobello, P. , … Novara, C. (2021). Students' mental health problems before, during, and after COVID‐19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 69–77. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miniati, M. , Marzetti, F. , Palagini, L. , Marazziti, D. , Orrù, G. , Conversano, C. , & Gemignani, A. (2021). Eating disorders spectrum during the COVID pandemic: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 663376. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone, A. M. , Marciello, F. , Cascino, G. , Abbate‐Daga, G. , Anselmetti, S. , Baiano, M. , … Monteleone, P. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 lockdown and of the following “re‐opening” period on specific and general psychopathology in people with eating disorders: The emergent role of internalizing symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 285, 77–83. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, J. F. , Reid, F. , & Lacey, J. H. (1999). The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ, 319, 1467–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z. , Peters, M. D. , Stern, C. , Tufanaru, C. , McArthur, A. , & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L. , Markey, K. , O'Donnell, C. , Moloney, M. , & Doody, O. (2021). The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and its related restrictions on people with pre‐existent mental health conditions: A scoping review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35, 375–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]