Abstract

Background and aims

The COVID‐19 pandemic represents a source of stress and potential burnout for many physicians. This single‐site survey aimed at assessing perceived stress and risk to develop burnout syndrome among physicians operating in COVID wards.

Methods

This longitudinal survey evaluated stress and burnout in 51 physicians operating in the COVID team of Gemelli Hospital, Italy.

Participants were asked to complete the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and the Perceived Stress Questionnaire on a short run (PSQs) (referring to the past 7 days) at baseline (T0) and then for four weeks (T1‐T4). Perceived Stress Questionnaire on a long run (PSQl) (referring to the past 2 years) was completed only at T0.

Results

Compared with physicians board‐certified in internal medicine, those board‐certified in other disciplines showed higher scores for the Emotional Exhaustion (EE) score of the MBI scale (P < .001). Depersonalisation (DP) score showed a reduction over time (P = .002). Attending physicians scored lower than the resident physicians on the DP scale (P = .048) and higher than resident physicians on the Personal Accomplishment (PA) scale (P = .04). PSQl predicted higher scores on the EE scale (P = .003), DP scale (P = .003) and lower scores on the PA scale (P < .001). PSQs showed a reduction over time (P = .03). Attending physicians had a lower PSQs score compared with the resident physicians (P = .04).

Conclusions

Medical specialty and clinical position could represent risk factors for the development of burnout in a COVID team. In these preliminary results, physicians board‐certified in internal medicine showed lower risk of developing EE during the entire course of the study.

What’s known?

Physician burnout has always been a universal dilemma that is seen in healthcare professionals. COVID‐19 pandemic has had an important impact on the health care system all over the world, and the response to the pandemic has represented additional stress for all health care providers, including physicians. Some peculiarities could represent potential risk factors for the development of burnout in a COVID team of physicians.

What’s new?

Medical specialty and clinical position could represent potential risk factors for the development of burnout in a COVID team of physicians. In our sample, physicians board‐certified in internal medicine showed lower risk of developing emotional exhaustion, during the entire course of the study, compared with physicians board‐certified in other disciplines. The latter had an increase in the perceived stress over time, compared with physicians board‐certified in internal medicine.

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2), originating from Wuhan, China in December 2019, is in the same family as the causative agents for previous Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreaks. The high rates of transmissibility, in particular from asymptomatic carriers, as well as the high severity of illness in individuals with very common preexisting chronic conditions (eg, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, lung disease) 1 led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the outbreak of this new coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, in January 2020. Two months later, WHO declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic. 2 The exponential growth of cases all over the world and the unprecedented severity of this outbreak, at least as it related to the past century, left many physicians unprepared for an event of this magnitude. The COVID‐19 pandemic has had an important impact on health care systems all over the world, and the response to the pandemic has added stress to all health care providers, including physicians.

Several factors, including perceived stress and burnout, have an impact on clinicians' well‐being and could result in increased medical errors and malpractice risk, therefore adversely affecting patient care. 3

Physician burnout has always been a universal dilemma that is seen in healthcare professionals, resulting from chronic work‐related stress, with symptoms characterised by feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, increased mental distance from one's job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job, and reduced professional efficacy. 4 Factors such as working hours, workload expectations, insufficient rewards, interpersonal communication, negative leadership, and quality of night sleep have always been considered influential. 4 Many physicians had to change departments quickly, often on a short notice and found themselves working in an unfamiliar environment. They found themselves caring for patients who were not their usual ones and having to manage new and unexpected clinical challenges. It was considered appropriate to investigate which specialists were best suited to manage this unprecedented situation. As shown in the literature, work experience and age are protective factors against Burnout. 4 In addition, the type of work performed may also have an impact on stress and the risk of developing Burnout. Age, career years, and the type of activity performed are related to a job position. More experienced physicians have older age and have more managerial roles, and have less contact with the patient. Moreover, the development of burnout syndrome affects patients’ quality of care, and it has a direct, negative impact on the physicians’ quality of life, in particular on mood disorders, anxiety, alcohol and substance use disorders, and suicides. 4

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, it is more important than ever to address the physical and psychological health of physicians, who are already at risk of experiencing stress and developing burnout syndrome.

This pilot study aimed to conduct a survey in a group of physicians, working in a COVID team, during the March‐April 2020 outbreak in Italy. The goal of the survey was to evaluate their perceived stress and burnout before, during and after the experience in a COVID team, and identify subgroups of physicians at higher risk of developing burnout and stress.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This longitudinal survey was conducted among physicians involved in the COVID team of the Gemelli Hospital, Rome, Italy during the March‐April 2020 outbreak, specifically from March 19, 2020 to April 21, 2020. All of the physicians to whom the survey was submitted worked in departments with a similar intensity of care. No other exclusion criteria were used.

A sample size was not calculated a priori for this study, which in fact represents a pilot investigation that may guide power calculation and other aspects of future larger studies.

A total of 136 physicians were invited by email, face‐to‐face or direct phone call to participate, at their entry into the COVID team. The invitation to participate explained the voluntary and confidential nature of the study. Among them, 53 consented to participate in the study. None of the physicians who filled out the questionnaires had a psychiatric history.

Participants were asked to indicate their gender and age. Also, information was collected on their clinical position (ie, whether they were attending physicians or resident physicians), and on their medical specialty (board‐certified in internal medicine or in other disciplines). Once they left the COVID team, they were asked to specify whether they had been in contact with patients who had died because of COVID‐19. Given the small sample and the high percentage of physicians board‐certified in internal medicine in our study, the specialty variable divided the sample into physicians board‐certified in internal medicine vs physicians board‐certified in other disciplines. The latter subgroup included physicians board‐certified in endocrinology, rheumatology, gastroenterology, emergency medicine, geriatrics and allergology. Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics. All values are reported as frequency and percentage or mean and standard deviation

| Frequency or mean | Percentage or SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 25 | 49.02% |

| Men | 26 | 50.98% |

| Age | 34.76 | 8.89 (SD) |

| Clinical position | ||

| Resident physician | 27 | 52.94% |

| Attending physician | 24 | 47.06% |

| Medical specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 26 | 50.98% |

| Other disciplines | 25 | 49.02% |

| Report dead COVID‐19 patients | ||

| No | 17 | 33.33% |

| Yes | 34 | 66.67% |

Physicians were asked to complete the PSQ on a long term (PSQl) at enrolment and Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and PSQ on a short term (PSQs) at enrolment and weekly. Reminders to complete the questionnaires were periodically sent to the participants by email. Two participants, who only answered one questionnaire, were excluded from the data analysis, therefore the final analysed sample included 51 participants.

The questionnaires were administered at baseline and at each follow‐up timepoint. The exact timeline was slightly flexible, based on the shifts during which the participants were working in the COVID team. T0 refers to questionnaires completed during a time window ranging from 3 days before to 3 days after joining the COVID team. T1 refers to the questionnaires completed during the time window ranging from day 4 and day 10 of work on the COVID team. T2 refers to those completed during the time window ranging from day 11 and day 17. T3 refers to those completed during the time window ranging from day 18 and day 24, and T4 refers to those completed during the time window ranging from day 25 and day 31.

The study was approved by the Catholic University of Rome Ethics Committee and was consistent with the European good clinical practice standards (art.34 RD 223/2004; European Community Directive 2001/20/EC).

2.1. Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey (MBI‐HSS)

Burnout was measured using MBI‐HSS (Italian validated version). 5 The questionnaire consists of 22 items, divided into 3 scales: 9 items for Emotional Exhaustion (EE), 5 items for Depersonalisation (DP) and 8 for Personal Accomplishment (PA). Each item was scored according to a Likert scale ranging from “never” (0) to “every day” (6). Each subscale was scored individually and assessed on a continuous scale. The dimensions were categorised into low, moderate and high levels, considering the cut‐off points previously validated. In particular, EE scores were categorised as low: 0‐18, medium: 19‐26, high: ≥27. DP scores were categorised as: low: 0‐5, moderate: 6‐9, high: ≥10. PA scores were categorised as: low: 0‐33, moderate: 34‐39, high: ≥40. Low scores for EE and DP and high ones for PA indicate the absence of burnout. Exceeding the cut‐off in all scales corresponds to a higher risk of burnout syndrome. A reduced PA is inversely associated with burnout. 6 , 7

2.2. Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ)

The perceived stress was measured using the Italian version of the PSQ. 8 PSQ consists of 20 items (PSQ‐20) divided into four scales: Worries, Tension and Joy measure the individual's internal stress reactions and Demands represents the individual's general perception of external stressors. Each item was rated on a 4‐point Likert scale from 1: “almost never” to 4: “usually.” A linear transformation changes the subscale scores to values from 0 to 1. 9 Participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire on a long run form (Perceived Stress Questionnaire on Long term, PSQl), marking the answers that best described their emotional state over the last 2 years. In addition, they were asked to mark the answers that best described their emotional state in the last month (Perceived Stress Questionnaire‐on Short term, PSQs).

2.3. Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14, according to the modified intention to treat in the worst‐case scenario model. The descriptive statistics were performed using averages (SD) and median (IQR) for quantitative variables and frequency and percentage for categorical ones. Linear mixed models were designed for each continuous variable of interest. All models were estimated through restricted maximum likelihood (REML). A null model was initially analysed to evaluate the variability of the dependent variable among the participants and evaluate data structure. The time variable was inserted in the analysis to investigate the variability, over time, of the variables of interest. The variance over time of the intercept and slope between participants for dependent variables has been studied. The time was treated as a continuous variable. The possibility that some variables could explain the characteristics of interest was then studied. All of the variables described above have been studied as fixed covariates, and any interactions have been studied. More covariance structures have been tested to account for heteroskedasticity. Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal any obvious deviations from homoscedasticity or normality. P‐values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests of the full model, with the effect in question against the model without the effect the same.

Student's t tests, Mann‐Whitney, variance analysis and Kruskal‐Wallis and Dunn post hoc tests were performed to analyse the relationship between sociodemographic and professional data and PSQl scales.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Maslach Burnout Inventory

On MBI, median (IQR) values were analysed for each scale. EE showed a value of 19 (11‐25) at T0, and of 13 (7‐23) at T4.

DP showed a value of 5 (2‐9) and 3 (1‐8) at T4. Finally, PA score at T0 was 42 (38‐47) and 41 (36‐46) at T4. The remaining median values (IQRs) are shown in Table 2. In addition, the complete results of linear mixed model analysis are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Median score of MBI scales

| Median (IQR) | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 19 (11‐25) | 14 (7‐25) | 15 (7‐24) | 15 (7‐24.5) | 13 (7‐23) |

| DP | 5 (2‐9) | 4 (1‐9) | 4 (1‐9) | 3 (0/9) | 3 (1‐8) |

| PA | 42 (38‐47) | 42.5 (38‐45.25) | 42 (36‐46) | 42 (36‐46) | 41 (36‐46) |

TABLE 3.

Each Maslach Burnout Inventory scale was individually tested with each independent variable with Linear Mixed Model

| Coefficients | P | [95% | CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | ||||

| Time | −0.1855461 | .509 | −0.7360901 | 0.3649979 |

| Age | −0.2831311 | .100 | −0.6204909 | 0.0542287 |

| Gender (referent women) | 3.465964 | .271 | −2.7056 | 9.637528 |

| C. position (referent residents) | −4.265795 | .172 | −10.38862 | 1.857034 |

| Specialty (referent Int. Med.) | 8.391379 | .004 | 2.640286 | 14.14247 |

| Rep dead Cov‐19 p (referent No) | −5.62258 | .083 | −11.98492 | 0.7397577 |

| PSQ/Short | 52.49965 | .000 | 38.35497 | 66.64434 |

| Depersonalisation | ||||

| Time | −0.3430927 | .004 | −0.5784324 | −0.107753 |

| Age | −0.1693321 | .045 | −0.3352664 | −0.0033978 |

| Gender (referent women) | 2.497344 | .105 | −0.5249497 | 5.519638 |

| C. position (referent residents) | −2.524302 | .102 | −5.550627 | 0.5020234 |

| Specialty (referent Int. Med) | 2.572788 | .095 | −0.4467031 | 5.592279 |

| Rep. dead Cov‐19 p (referent No) | 0.572288 | .732 | −2.696747 | 3.841323 |

| PSQ/Short | 17.1919 | .000 | 7.563742 | 26.82007 |

| Personal accomplishment | ||||

| Time | −0.1737624 | .318 | −0.5146185 | 0.1670936 |

| Age | 0.2261985 | .041 | 0.0090496 | 0.4433474 |

| Gender (referent women) | 2.021447 | .328 | −2.025661 | 6.068554 |

| C. position (referent residents) | 4.617989 | .019 | 0.7630367 | 8.47294 |

| Specialty (referent Int. Med.) | −1.651755 | .424 | −5.704125 | 2.400614 |

| Rep. dead Cov‐19 p (referent No) | 2.023576 | .351 | −2.228826 | 6.275978 |

| PSQ/Short | −26.50371 | .000 | −38.59023 | −14.41719 |

Abbreviations: C. position, clinical position; CI, confidence interval; Int. Med., internal medicine physicians; PSQ/Short, perceived stress questionnaire on short run.; Rep. dead Cov‐19 p, reporting dead COVID‐19 patients; SE, standard error.

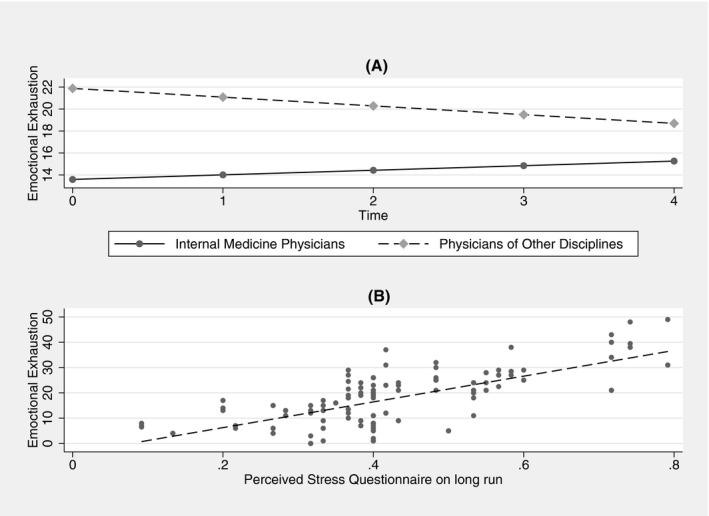

The data analysis did not show significant variations of the EE score over time (β, 0.42; 95% CI: −0.41 to 1.24; P = .32). A model was built by inserting Overall PSQ scale on the long term and specialty, considering the interaction between specialty and time. Higher scores at Overall PSQ scale on long term predicted higher scores on EE scale (β, 49.99; 95% CI: 37.89 to 62.08; P < .001). Compared with the physicians board‐certified in internal medicine, physicians board‐certified in other disciplines showed higher scores on the EE scale (β, 8.28; 95% CI: 4.50 to 12; P < .001), however, the former showed a significant reduction of EE score over time (β, −1.21; 95% CI: −2.36 to −0.06; P = .04) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Linear Mixed Model of Maslach Burnout Inventory—Emotional Exhaustion (EE) scale. A, EE score over time by medical specialty (β, 8.28; 95% CI, 4.50 to 12; P < .001). Compared with physicians board‐certified in internal medicine, physicians board‐certified in other disciplines showed a significant reduction of EE score (β, −1.21; 95% CI, −2.36 to −0.06; P = .04). B, scatter plot and regression line indicating the correlation between EE score and PSQ on a long run score (β, 49.99; 95% CI, 37.89 to 62.08; P < .001)

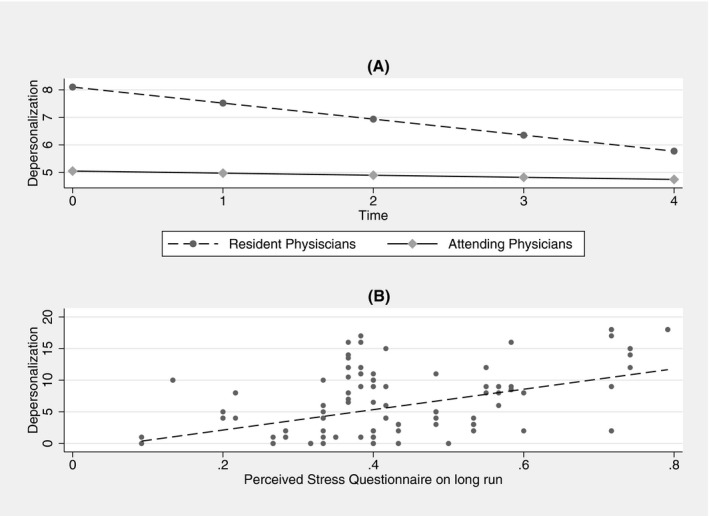

The data analysis showed a significant reduction in the DP scores over time (β, −0.58; 95% CI: −0.95 to −0.22; P = .002). A model was built by inserting Overall PSQ scale on a long period and clinical position, considering the interaction between clinical position and time. Higher scores on Overall PSQ scale on long term predicted higher scores on the DP scale (β, 14.91; 95% CI: 5.11 to 24.72; P = .003). Attending physicians scored significantly lower than resident physicians on the DP scale (β, −3.05; 95% CI: −6.07 to −0.02; P = .048), however, the latter showed decreasing score on this scale over time than attending physicians (β, 0.50; 95% CI: 0.01 to 1.00; P = .047) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Linear Mixed Model of Maslach Burnout Inventory—Depersonalisation (DP) scale. A, DP score over time by clinical position (attending vs. resident). Attending physicians showed lower score on the DP scale over time than resident physicians (β, −3.05; 95% CI, −6.07 to −0.02; P = .048). The latter showed decreasing score on the DP scale over time than attending physicians (β, 0.505; 95% CI, 0.01 to 1.00; P = .047). B, scatter plot and regression line indicating the correlation between DP score and PSQ on a long run score (β, 14.91; 95% CI, 5.11 to 24.72; P = .003)

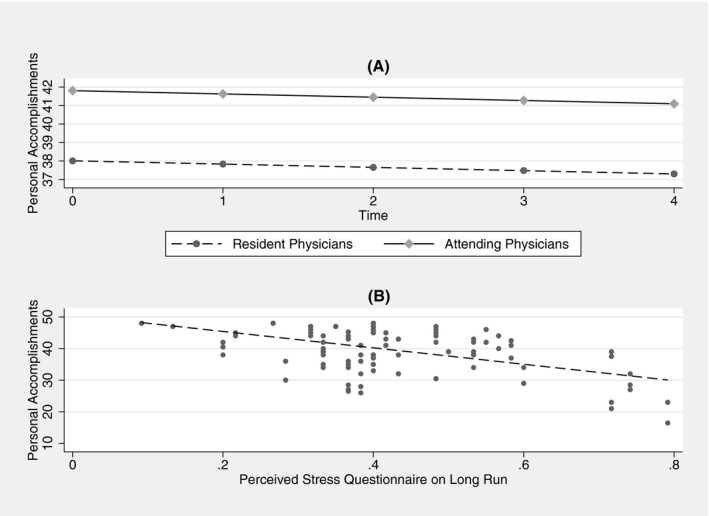

The data analysis did not show a significant increase in PA scores over time (β, −0.18; 95% CI: −0.56 to 0.2; P = .36). A model was built by inserting Overall PSQ scale on long term and clinical position. Higher scores on Overall PSQ scale on long term predicted lower scores on the PA scale (β, −23.34; 95% CI: −35.37 to −11.31; P < .001). Attending physicians score significantly higher than resident physicians on the PA scale (β, 3.8; 95% CI: 0.14 to 7.45; P = .04) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Linear Mixed Model of Maslach Burnout Inventory—Personal Accomplishment (PA) scale. A, PA score over time by clinical position (attending vs. resident) (β, 3.8; 95% CI, 0.14 to 7.45; P = .04). B, Scatter plot and regression line indicating correlation between PA score and PSQ on a long run score (β, −23.34; 95% CI, −35.37 to −11.31; P < .001)

3.2. Perceived Stress Questionnaire

On PSQl, the effect of the medical specialty on the Worries score was statistically significant, and physicians board‐certified in internal medicine scored lower than physicians board‐certified in other disciplines [0.2 (0.13‐0.27)‐0.33 (0.27‐0.43), P = .006]. Resident physicians reported higher scores than attending physicians on the Tension [.33 (0.2‐0.47)‐(0.33‐0.53), P = .08], but lower scores on the Joy scale [0.33 (0.13‐0.53)‐0.47 (0.33‐0.667), P = .019]. There was a significant effect of clinical position on the Overall score, with attending physicians reporting higher score than resident physicians [0.43 (0.38‐0.57)‐0.37 (0.27‐0.48), P = .03]. The results of the linear mixed models are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Each perceived stress questionnaire on short run scale was individually tested with each independent variable with linear mixed model

| Coefficients | P | [95% | CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| Time | −0.0058436 | .219 | −0.0151513 | 0.0034642 |

| Age | −0.0030716 | .234 | −0.0081335 | 0.0019903 |

| Gender (referent women) | 0.0315115 | .494 | −0.058753 | 0.1217761 |

| C. Position (Referent Residents) | −0.0761806 | .091 | −0.1646045 | 0.0122433 |

| Specialty (referent int. med.) | 0.0435667 | .343 | −0.0465063 | 0.1336397 |

| Rep. Dead Cov‐19 P (Referent No) | −0.0897852 | .055 | −0.1815088 | 0.0019384 |

| Worries | ||||

| Time | 0.0017922 | .767 | −0.0100428 | 0.0136272 |

| Age | −0.00342 | .207 | −0.0087364 | 0.0018965 |

| Gender (referent women) | 0.0293974 | .544 | −0.0655512 | 0.1243461 |

| C. Position (Referent Residents) | −0.0708057 | .138 | −0.1644523 | 0.0228409 |

| Specialty (referent int. med.) | 0.0512316 | .288 | −0.0433463 | 0.1458095 |

| Rep. Dead Cov‐19 P (Referent No) | −0.0809443 | .104 | −0.1785173 | 0.0166288 |

| Tension | ||||

| Time | −0.0026621 | .577 | −0.0120134 | 0.0066892 |

| Age | −0.006273 | .041 | −0.0122888 | −0.0002573 |

| Gender (referent women) | −0.0047833 | .933 | −0.1159456 | 0.1063789 |

| C. Position (Referent Residents) | −0.1374169 | .010 | −0.2415188 | −0.033315 |

| Specialty (referent int. med.) | 0.0462255 | .412 | −0.0642736 | 0.1567246 |

| Rep. Dead Cov‐19 P (Referent No) | −0.0523349 | .378 | −0.1687736 | 0.0641037 |

| Joy | ||||

| Time | 0.0046999 | .490 | −0.0086513 | 0.0180512 |

| Age | −0.0002399 | .946 | −0.0071928 | 0.0067131 |

| Gender (referent women) | 0.0120728 | .848 | −0.1110569 | 0.1352025 |

| C. Position (Referent Residents) | 0.0754639 | .224 | −0.0461794 | 0.1971071 |

| Specialty (referent int. med.) | −0.0271482 | .665 | −0.1501981 | 0.0959017 |

| Rep. Dead Cov‐19 P (Referent No) | 0.1767485 | .003 | 0.0588353 | 0.2946618 |

| Demands | ||||

| Time | −0.0239428 | .001 | −0.0385623 | −0.0093232 |

| Age | −0.0025001 | .448 | −0.0089561 | 0.0039559 |

| Gender (referent women) | 0.0567881 | .329 | −0.057211 | 0.1707872 |

| C. Position (Referent Residents) | −0.0513401 | .377 | −0.165326 | 0.0626458 |

| Specialty (referent int. med.) | 0.0630626 | .276 | −0.0504838 | 0.176609 |

| Rep. Dead Cov‐19 P (Referent No) | 0.0272097 | .660 | −0.0939563 | 0.1483756 |

Abbreviations: C. position, clinical position; CI, confidence interval; Int. Med., internal medicine physicians; PSQ/short, perceived stress questionnaire on short run; Rep. dead Cov‐19 p, reporting dead COVID‐19 patients; SE, standard error.

The data analysis showed a significant reduction of the Overall scores over time (β, −0.01; 95% CI: −0.03 to −0.002; P = .03). A model was built by inserting clinical position and the contact with patients who died for COVID‐19, also considering the interaction between specialty and time. Attending physicians tended to have a lower Overall scale score compared with the resident physicians (β, −0.08; 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.008; P = .07). Compared with physicians board‐certified in internal medicine, those board‐certified in other disciplines had an increase in the Overall scale score over time (β, 0.02; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.04; P = .04). Those who were in contact with patients who died from COVID‐19 had a lower Overall score (β, −0.09; 95% CI: −0.18 to 0.00; P = .05).

The data analysis did not show a significant modification in the Worries score over time (β, −0.02; 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.01; P = .5). None of the parameters analysed in the study were able to predict the Worries scale score.

The data analysis did not show a significant reduction in the Tension scores over time (β, 0.00; 95% CI: −0.01 to 00; P = .5). A model was built by considering the interaction of medical specialty and clinical position. Compared with resident physicians training in internal medicine, resident physicians training in other disciplines scored higher on the Tension scale (β, 0.25; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.39; P < .001).

The data analysis did not show a significant reduction in the Joy scores over time (β, 0.00; 95% CI: −0.01 to 0.02; P = .49). A model was built by inserting contact with patients who died from COVID‐19, considering the interaction of specialty and clinical positions. Those who had contact with patients who died from COVID‐19 had a higher Joy score (β, 0.17; 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.28; P = .002). Analysis of the interaction between clinical position and specialty indicated that resident physicians training in other disciplines scored lower than resident physicians training in internal medicine on the Joy scale (β, −0.21; 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.06; P = .008). However, attending physicians board‐certified in other disciplines scored higher than resident physicians board‐certified in internal medicine on it (β, 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.52; P = .005).

Finally, for the Demands scale, data analysis showed a significant reduction in score over time (β, −0.02; 95% CI: −0.04 to −0.01; P < .001). None of the parameters analysed in the study were able to predict the Demands scale score.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the perceived stress and burnout, assessed by the PSQ and MBI questionnaires, respectively, in physicians working in a single‐site COVID team, identifying potential risk factors predisposing to this state of physical and mental exhaustion.

Many risk factors have been identified in the literature, whether personal (age, gender), familial (being married, having children, living alone) or occupational (position, specialty, constant changes in working conditions). 10

The concern of being infected, the increase in working hours, the critical conditions of patients are some of the main causes leading to stress and burnout, which in turn may increase medical error. 11

Occupational risk factors were considered in this study.

On MBI, in contrast to what was expected and reported in other studies, 12 , 13 a significant reduction in depersonalisation (DP score) was found over time. This effect could be related to the reduced perception of environmental stress displayed in our sample. Moreover, resident physicians scored higher on Depersonalisation scale than attending physicians. However, the latter showed a significant increasing score over time. Di Monte et al 14 have shown a correlation between age, years of work experience and depersonalisation; all factors related to clinical position. Occupational factors greatly affect the mental well‐being of physicians and healthcare workers employed during the emergency of COVID‐19. 15 For the PSQ scale, a significant reduction in perceived stress over time was also found, both on the overall PSQ scale and specifically in the level of perceived demands as measured by the Demands subscale. Stress and depersonalisation were also found to be correlated. Similar results are reported in the literature in particular in the study of Kelker et al, 16 which reported a significant reduction in personal safety concerns and symptoms of stress, anxiety and fear over 4 weeks. Hines et al 17 demonstrated a reduction in distress over time measured at baseline, 1‐ and 3‐month time points, showing that the level of moral injuries was unchanged, a finding confirmed by another study in Canadian emergency physicians that found no significant differences in terms of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation in the first weeks after the start of the pandemic. 18 The reduction in stress and depersonalisation over time could be because of the ability of staff to adapt to the new work environment and the improvement and improvement of guidelines for COVID departments over time.

In our study, MBI and PSQ‐20 scores were better in attending physicians than resident physicians. Higher professional qualification could be a protective factor for burnout and stress. This result confirms what has been reported in the literature. 19 , 20 A systematic review by Pulcrano et al, conducted in the pre‐COVID era, already showed a higher prevalence of burnout among residents than in attending physicians. 21

It should also be noted that some studies do not report a significant difference between the prevalence of burnout in residents working in COVID wards and those working in normal wards, 22 and others despite reporting such a difference do not report a significant increase in the prevalence of burnout compared with data reported in the pre‐COVID era. 23 This could be because of a rearrangement of work as working hours are reduced and remote work is employed. 23 , 24

This observation may be related to a higher professional experience of attending physicians in patients’ management, and the greater perception of own responsibility could be related to higher personal accomplishment. In particular, resident physicians seem to be at higher risk of burnout syndrome among doctors, and the risk of burnout is progressively reduced with career progression. 25 Also, the age of the physicians (older than resident physicians) could play a role in this risk reduction: previous investigations already documented an inverse relationship between the prevalence of burnout syndrome and the age of physicians. 26 The different job roles of residents, with more demanding call schedules, could also impact this difference, affecting work and family life, sleep, and possibly being associated with an increased risk of depression and burnout. 20 , 27 , 28 Some protective factors in addition to mentorship and support, having control over one's time and taking mental breaks. 29

As reported in the literature, 21 , 30 medical specialty also plays an important role in influencing the risk of burnout syndrome. In this sample, physicians board‐certified in internal medicine, compared with those board‐certified in other disciplines, showed a reduced risk of developing emotional exhaustion during the entire course of the study. However, Macía‐Rodríguez et al demonstrated how the prevalence of burnout increased in those working in contact with COVID patients compared with pre‐pandemic years. 31 Cubitt et al identified a decline in mental health common to all medical specialties, however, less expressed in those who worked in acute care medicine. 32 Habit in managing complex situations may in fact mitigate the effect of the pandemic on physicians' mental health. Similarly, it is conceivable that the broader scope of work of the internists in our hospital that work in inpatient unit, rather than outpatient settings, and manage patients with more comorbidities (as the ones with coronavirus disease usually show), could make physicians board‐certified in internal medicine less vulnerable to burnout and stress when managing this type of patient. In contrast, Torrente et al 33 did not identify significant differences between physicians with different specialties working in COVID departments.

Interestingly, study participants who reported no contact with patients who died of COVID‐19, during their work on the COVID team, showed lower levels of positive feelings and were more at risk of developing burnout syndrome. On the other side, physicians who worked in the same departments and during the same time period reported having been in contact with patients who died from COVID‐19. Denying the event may be an attempt to avoid traumatic memories that can trigger unpleasant emotions, and this can be interpreted as an acute response to stress.

Notably, the overall PSQ scale on long term predicted all the three scales of MBI in our sample. The close correlation of MBI and PSQl scale showed in the present study could justify a screening of physicians involved in emergencies similar to COVID. Moreover, the observed early increased score in MBI scales could help identify those physicians who are most likely to develop burnout syndrome and could benefit from individual support interventions. 34

Although during a public health emergency like this unprecedented pandemic it is not easy to select the staff to be involved, it would be useful to enlist mainly those with a lower risk of developing burnout syndrome. Moreover, based on our data, it would be appropriate to start involving the most experienced physicians. Besides, monitoring physicians through MBI administration every two weeks could help establish a shift system to reduce the perception of environmental stress through even short periods of rest at home.

This study has some limitations: because of the different organisation of the teams of other health professionals (eg, nurses and social workers) involved in the COVID emergency in our hospital, it was not feasible to enrol them. The small sample and the fact that the survey was conducted in one hospital prevent generalisability of the findings. Moreover, missing data and failure to adhere to the timing of the follow up could contribute to a bias in the results, although this was a limitation impossible to control for, given the emergency conditions under which the study was conducted. Another limitation of this study is that no patient information was called, therefore we were not able to investigate whether patient's severity of the disease could have an impact on the outcomes assessed in the COVID team. Also, the short follow up may have overestimated the predictive ability of the PSQl on the risk of burnout.

In conclusion, assessing risk factors for stress and burnout syndrome in physicians involved in an emergency response such as COVID‐19 could be useful in order to: (a) provide adequate psychological support to those who need it, (b) help physicians find a balance recognising what they can and cannot control 35 and (c) help them address their concerns, improve the individuals' stress response and, consequently, their professional performance. Such a supportive work environment can be critical in maintaining the resilience of clinicians, especially during a crisis such as COVID‐19. 25 Institutions should also provide support to healthcare teams to help with their work organisation and internal dynamics, as well as provide individual support to healthcare professionals to improve the working environment and mental health of their employees. 36 It would also be desirable that health care organisations first provide information on reducing burnout and propose a screening of the physicians involved in the emergency teams, to identify those at higher risk of burnout early and set appropriate shift rotations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

LL is supported by the NIDA and NIAAA intramural research programs. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, T.D and GA; Methodology, TD, L.L and GA; Data collection and analysis, TD, LS, CT and MA; Writing‐original draft preparation, TD, L.S, GA; Writing‐review and editing, TD, LS, AT, SD, MA, GAV, LL, A.G and GA All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Members of the GEMELLI AGAINST COVID‐19 group from Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS Members of Gemelli Against COVID‐19 Group: Valeria Abbate, Nicola Acampora, Giovanni Addolorato, Fabiana Agostini, Maria E. Ainora, Elena Amato, Gloria Andriollo, Brigida E. Annicchiarico, Mariangela Antonelli, Gabriele Antonucci, Alessandro Armuzzi, Christian Barillaro, Fabiana Barone, Rocco D. A. Bellantone, Daniela Belella, Andrea Bellieni, Andrea Benicchi, Francesca Benvenuto, Filippo Berloco, Roberto Bernabei, Antonio Bianchi, Luigi M. Biasucci, Stefano Bibbò, Federico Biscetti, Nicola Bonadia, Alberto Borghetti, Giulia Bosco, Silvia Bosello, Vincenzo Bove, Giulia Bramato, Vincenzo Brandi, Dario Bruno, Maria C. Bungaro, Alessandro Buonomo, Maria Livia Burzo, Angelo Calabrese, Andrea Cambieri, Giulia Cammà, Marcello Candelli, Gennaro Capalbo, Lorenzo Capaldi, Esmeralda Capristo, Luigi Carbone, Silvia Cardone, Angelo Carfì, Annamaria Carnicelli, Claudia Carnuccio, Cristiano Caruso, Francesco Antonio Casciaro, Lucio Catalano, Roberto Cauda, Andrea LCecchini, Lucia Cerrito, Michele Ciaburri, Rossella Cianci, Sara Cicchinelli, Arturo Ciccullo Francesca Ciciarello, Antonella Cingolani, Maria C. Cipriani, Gaetano Coppola, Andrea Corsello, Federico Costante, Marcello Covino, Stefano D'Addio, Alessia D'Alessandro, Maria E. D'Alfonso, Emanuela D'Angelo, Marco D'Angelo, Francesca D'Aversa, Alessandro D'Errico, Fernando Damiano, Tommaso De Cunzo, Giuseppe De Matteis, Martina De Siena, Francesco De Vito, Valeria Del Gatto, Paola Del Giacomo, Fabio Del Zompo, Davide Antonio Della Polla, Elisabetta Del Sordo, Luca Di Gialleonardo, Simona Di Giambenedetto, Roberta Di Luca, Luca Di Maurizio, Alex Dusina, Alessandra Esperide, Domenico Faliero, Cinzia Falsiroli, Massimo Fantoni, Annalaura Fedele, Daniela Feliciani, Daniele Ferrarese, Andrea Flex, Evelina Forte, Francesco Franceschi, Laura Franza, Barbara Funaro, Mariella Fuorlo, Domenico Fusco, Maurizio Gabrielli, Eleonora Gaetani, Antonella Gallo, Giovanni Gambassi, Matteo Garcovich, Antonio Gasbarrini, Irene Gasparrini, Silvia Gelli, Antonella Giampietro, Laura Gigante, Gabriele Giuliano, Giorgia Giuliano, Bianca Giupponi, Elisa Gremese, Caterina Guidone, Amerigo Iaconelli, Angela Iaquinta, Michele Impagnatiello, Riccardo Inchingolo, Raffaele Iorio, Immacolata MIzzi, Cristina Kadhim, Daniele I. La Milia, Francesco Landi, Giovanni Landi, Rosario Landi, Massimo Leo, Antonio Liguori, Rosa Liperoti, Marco M. Lizzio, Maria R. Lo Monaco, Pietro Locantore, Francesco Lombardi, Loris Lopetuso, Valentina Loria, Angela R. Losito, Noemi Macerola, Giuseppe Maiuro, Francesco Mancarella, Francesca Mangiola, Alberto Manno, Sergio Mannucci, Debora Marchesini, Giuseppe Marrone, Ilaria Martis, Anna M. Martone, Emanuele Marzetti, Maria V. Matteo, Luca Miele, Alessio Migneco, Irene Mignini, Alessandro Milani, Domenico Milardi, Massimo Montalto, Flavia Monti, Davide Moschese, Barbara P. L. Mothaenje, Celeste A. Murace, Rita Murri, Marco Napoli, Elisabetta Nardella, Gerlando Natalello, Simone M. Navarra, Antonio Nesci, Maria Anna Nicolazzi, Alberto Nicoletti, Tommaso Nicoletti, Rebecca Nicolò, Nicola Nicolotti, Enrico C. Nista, Eugenia Nuzzo, Veronica Ojetti, Francesco CPagano, Cristina Pais, Maria Pallozzi, Alfredo Papa, Luigi G. Papparella, Mattia Paratore, Giuseppe Parrinello, Giovanni Pecorini, Simone Perniola, Erika Pero, Claudia Petito, Luca Petricca, Martina Petrucci, Chiara Picarelli, Andrea Piccioni, Giulia Pignataro, Raffaele Pignataro, Marco Pizzoferrato, Fabrizio Pizzolante, Roberto Pola, Caterina Policola, Maurizio Pompili, Valerio Pontecorvi, Francesca R. Ponziani, Valentina Popolla, Enrica Porceddu, Angelo Porfidia, Giuseppe Privitera, Daniela Pugliese, Gabriele Pulcini, Simona Racco, Francesca Raffaelli, Gian L. Rapaccini, Luca Richeldi, Emanuele Rinninella, Sara Rocchi, Stefano Romano, Federico Rosa, Laura Rossi, Raimondo Rossi, Enrica Rossini, Elisabetta Rota, Fabiana Rovedi, Gabriele Rumi, Andrea Russo, Luca Sabia, Andrea Salerno, Sara Salini, Lucia Salvatore, Dehara Samori, Maurizio Sanguinetti, Luca Santarelli, Paolo Santini, Angelo Santoliquido, Francesco Santopaolo, Michele C. Santoro, Francesco Sardeo, Caterina Sarnari, Luisa Saviano, Tommaso Schepis, Francesca Schiavello, Giancarlo Scoppettuolo, Luisa Sestito, Carlo Settanni, Valentina Siciliano, Benedetta Simeoni, Andrea Smargiassi, Domenico Staiti, Leonardo Stella, Eleonora Taddei, Rossella Talerico, Enrica Tamburrini, Claudia Tarli, Pietro Tilli, Enrico Torelli, Matteo Tosato, Alberto Tosoni, Luca Tricoli, Marcello Tritto, Mario Tumbarello, Anita M. Tummolo, Federico Valletta, Giulio Ventura, Lucrezia Verardi, Lorenzo Vetrone, Giuseppe Vetrugno, Elena Visconti, Raffaella Zaccaria, Lorenzo Zelano, Lorenzo Zileri Dal Verme, Giuseppe Zuccalà.

Dionisi T, Sestito L, Tarli C, et al. Risk of burnout and stress in physicians working in a COVID team: A longitudinal survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14755. 10.1111/ijcp.14755

Contributor Information

Giovanni Addolorato, Email: giovanni.addolorato@unicatt.it.

Gemelli Against COVID‐19 Group:

Valeria Abbate, Nicola Acampora, Fabiana Agostini, Maria E. Ainora, Elena Amato, Gloria Andriollo, Brigida E Annicchiarico, Gabriele Antonucci, Alessandro Armuzzi, Christian Barillaro, Fabiana Barone, Rocco D. A. Bellantone, Daniela Belella, Andrea Bellieni, Andrea Benicchi, Francesca Benvenuto, Filippo Berloco, Roberto Bernabei, Antonio Bianchi, Luigi M. Biasucci, Stefano Bibbò, Federico Biscetti, Nicola Bonadia, Alberto Borghetti, Giulia Bosco, Silvia Bosello, Vincenzo Bove, Giulia Bramato, Vincenzo Brandi, Dario Bruno, Maria C. Bungaro, Alessandro Buonomo, Maria Livia Burzo, Angelo Calabrese, Andrea Cambieri, Giulia Cammà, Marcello Candelli, Gennaro Capalbo, Lorenzo Capaldi, Esmeralda Capristo, Luigi Carbone, Silvia Cardone, Angelo Carfì, Annamaria Carnicelli, Claudia Carnuccio, Cristiano Caruso, Francesco Antonio Casciaro, Lucio Catalano, Roberto Cauda, Andrea L Cecchini, Lucia Cerrito, Michele Ciaburri, Rossella Cianci, Sara Cicchinelli, Arturo Ciccullo Francesca Ciciarello, Antonella Cingolani, Maria C. Cipriani, Gaetano Coppola, Andrea Corsello, Federico Costante, Marcello Covino, Alessia D'Alessandro, Maria E. D'Alfonso, Emanuela D'Angelo, Marco D'Angelo, Francesca D'Aversa, Alessandro D'Errico, Fernando Damiano, Tommaso De Cunzo, Giuseppe De Matteis, Martina De Siena, Francesco De Vito, Valeria Del Gatto, Paola Del Giacomo, Fabio Del Zompo, Davide Antonio Della Polla, Elisabetta Del Sordo, Luca Di Gialleonardo, Simona Di Giambenedetto, Roberta Di Luca, Luca Di Maurizio, Alex Dusina, Alessandra Esperide, Domenico Faliero, Cinzia Falsiroli, Massimo Fantoni, Annalaura Fedele, Daniela Feliciani, Daniele Ferrarese, Andrea Flex, Evelina Forte, Francesco Franceschi, Laura Franza, Barbara Funaro, Mariella Fuorlo, Domenico Fusco, Maurizio Gabrielli, Eleonora Gaetani, Antonella Gallo, Giovanni Gambassi, Matteo Garcovich, Irene Gasparrini, Silvia Gelli, Antonella Giampietro, Laura Gigante, Gabriele Giuliano, Giorgia Giuliano, Bianca Giupponi, Elisa Gremese, Caterina Guidone, Amerigo Iaconelli, Angela Iaquinta, Michele Impagnatiello, Riccardo Inchingolo, Raffaele Iorio, Immacolata M Izzi, Cristina Kadhim, Daniele I. La Milia, Francesco Landi, Giovanni Landi, Rosario Landi, Massimo Leo, Antonio Liguori, Rosa Liperoti, Marco M. Lizzio, Maria R. Lo Monaco, Pietro Locantore, Francesco Lombardi, Loris Lopetuso, Valentina Loria, Angela R. Losito, Noemi Macerola, Giuseppe Maiuro, Francesco Mancarella, Francesca Mangiola, Alberto Manno, Sergio Mannucci, Debora Marchesini, Giuseppe Marrone, Ilaria Martis, Anna M. Martone, Emanuele Marzetti, Maria V. Matteo, Luca Miele, Alessio Migneco, Irene Mignini, Alessandro Milani, Domenico Milardi, Massimo Montalto, Flavia Monti, Davide Moschese, Barbara P. L. Mothaenje, Celeste A. Murace, Rita Murri, Marco Napoli, Elisabetta Nardella, Gerlando Natalello, Simone M. Navarra, Antonio Nesci, Maria Anna Nicolazzi, Alberto Nicoletti, Tommaso Nicoletti, Rebecca Nicolò, Nicola Nicolotti, Enrico C. Nista, Eugenia Nuzzo, Veronica Ojetti, Francesco C Pagano, Cristina Pais, Maria Pallozzi, Alfredo Papa, Luigi G. Papparella, Mattia Paratore, Giuseppe Parrinello, Giovanni Pecorini, Simone Perniola, Erika Pero, Claudia Petito, Luca Petricca, Martina Petrucci, Chiara Picarelli, Andrea Piccioni, Giulia Pignataro, Raffaele Pignataro, Marco Pizzoferrato, Fabrizio Pizzolante, Roberto Pola, Caterina Policola, Maurizio Pompili, Valerio Pontecorvi, Francesca R. Ponziani, Valentina Popolla, Enrica Porceddu, Angelo Porfidia, Giuseppe Privitera, Daniela Pugliese, Gabriele Pulcini, Simona Racco, Francesca Raffaelli, Gian L. Rapaccini, Luca Richeldi, Emanuele Rinninella, Sara Rocchi, Stefano Romano, Federico Rosa, Laura Rossi, Raimondo Rossi, Enrica Rossini, Elisabetta Rota, Fabiana Rovedi, Gabriele Rumi, Andrea Russo, Luca Sabia, Andrea Salerno, Sara Salini, Lucia Salvatore, Dehara Samori, Maurizio Sanguinetti, Luca Santarelli, Paolo Santini, Angelo Santoliquido, Francesco Santopaolo, Michele C. Santoro, Francesco Sardeo, Caterina Sarnari, Luisa Saviano, Tommaso Schepis, Francesca Schiavello, Giancarlo Scoppettuolo, Carlo Settanni, Valentina Siciliano, Benedetta Simeoni, Andrea Smargiassi, Domenico Staiti, Leonardo Stella, Eleonora Taddei, Rossella Talerico, Enrica Tamburrini, Pietro Tilli, Enrico Torelli, Matteo Tosato, Luca Tricoli, Marcello Tritto, Mario Tumbarello, Anita M. Tummolo, Federico Valletta, Giulio Ventura, Lucrezia Verardi, Lorenzo Vetrone, Giuseppe Vetrugno, Elena Visconti, Raffaella Zaccaria, Lorenzo Zelano, Lorenzo Zileri Dal Verme, and Giuseppe Zuccalà

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID‐19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(8):1069–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Situation Summary. Published 2020 March 27 CDC.gov; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/cases‐updates/summary.html

- 3. Shah K, Chaudhari G, Kamrai D, Lail A, Patel RS. How essential is to focus on physician's health and burnout in coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic? Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci. 2018;8(11):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MBI manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto. Maslach C, Jackson SE and Leiter MP, eds. Consulting Psychologists Press; 191–218; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fernández O, Hidalgo C, Martín A, Moreno S, García del Río B. Burnout en médicos residentes que realizan guardias en un servicio de urgencias. Emergencias. 2007;19:116‐121. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Merces MCD, Coelho JM, Lua I, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout syndrome among primary health care nursing professionals: a cross‐sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:e474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heinen I, Bullinger M, Kocalevent RD. Perceived stress in first year medical students – associations with personal resources and emotional distress. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, et al. The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy adult samples. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):78‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aydemir O, Icelli I. Burnout: risk factors. In: Bährer‐Kohler S, ed. Burnout for Experts. Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sanghera J, Pattani N, Hashmi Y, et al. The impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 on the mental health of healthcare workers in a hospital setting‐A Systematic Review. J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):e12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rapisarda F, Vallarino M, Cavallini E, et al. The early impact of the COVID‐19 emergency on mental health workers: a survey in Lombardy, Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):e8615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vinnikov D, Dushpanova A, Kodasbaev A, et al. Occupational burnout and lifestyle in Kazakhstan cardiologists. Arch Public Health. 2019;77:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Monte C, Monaco S, Mariani R, Di Trani M. From resilience to burnout: psychological features of Italian general practitioners during COVID‐19 emergency. Front Psychol. 2020;11:567201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Serrano‐Ripoll MJ, Meneses‐Echavez JF, Ricci‐Cabello I, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:347‐357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelker H, Yoder K, Musey P Jr, et al. Prospective study of emergency medicine provider wellness across ten academic and community hospitals during the initial surge of the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hines SE, Chin KH, Glick DR, Wickwire EM. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Wit K, Mercuri M, Wallner C, et al. Canadian emergency physician psychological distress and burnout during the first 10 weeks of COVID‐19: a mixed‐methods study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(5):1030‐1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moitra M, Rahman M, Collins PY, et al. Mental health consequences for healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a scoping review to draw lessons for LMICs. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:602614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abdulrahman M, Nair SC, Farooq MM, Al Kharmiri A, Al Marzooqi F, Carrick FR. Burnout and depression among medical residents in the United Arab Emirates: a multicenter study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(2):435‐441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pulcrano M, Evans SR, Sosin M. Quality of life and burnout rates across surgical specialties: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):970‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al‐Humadi S, Bronson B, Muhlrad S, Paulus M, Hong H, Cáceda R. Depression, suicidal thoughts, and burnout among. JAMA Netw Open. physicians during the covid‐19 pandemic: a survey‐based cross‐sectional study. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID‐19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weaver MD, Landrigan CP, Sullivan JP, et al. The association between resident physician work‐hour regulations and physician safety and health. Am J Med. 2020;133(7):e343‐e354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work‐life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681‐1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rose M, Manser T, Ware JC. Effects of call on sleep and mood in internal medicine residents. Behav Sleep Med. 2008;6(2):75‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lazarides AL, Belay ES, Anastasio AT, Cook CE, Anakwenze OA. Physician burnout and professional satisfaction in orthopedic surgeons during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Work. 2021;69(1):15‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fiest KM, Parsons Leigh J, Krewulak KD, et al. Experiences and management of physician psychological symptoms during infectious disease outbreaks: a rapid review. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Macía‐Rodríguez C, Alejandre de Oña Á, Martín‐Iglesias D, et al. Burn‐out syndrome in Spanish internists during the COVID‐19 outbreak and associated factors: a cross‐sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e042966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cubitt LJ, Im YR, Scott CJ, Jeynes LC, Molyneux PD. Beyond PPE: a mixed qualitative‐quantitative study capturing the wider issues affecting doctors' well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e050223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Torrente M, Sousa PA, Sánchez‐Ramos A, et al. To burn‐out or not to burn‐out: a cross‐sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nanda A, Wasan A, Sussman J. Provider health and wellness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1543‐1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dewey C, Hingle S, Goelz E, Linzer M. Supporting clinicians during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11):752‐753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Geerts JM, Kinnair D, Taheri P, et al. Guidance for health care leaders during the recovery stage of the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(7):e2120295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.